Mollugin: A Comprehensive Review of Its Multifaceted Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

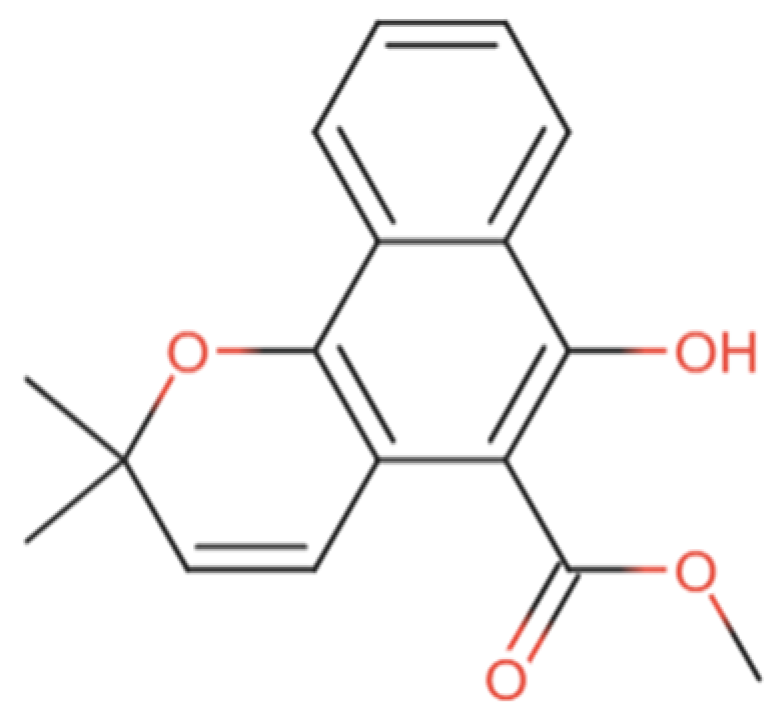

2. Pharmacological Activities of Mollugin

2.1. Anticancer Effects of Mollugin

2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Mollugin

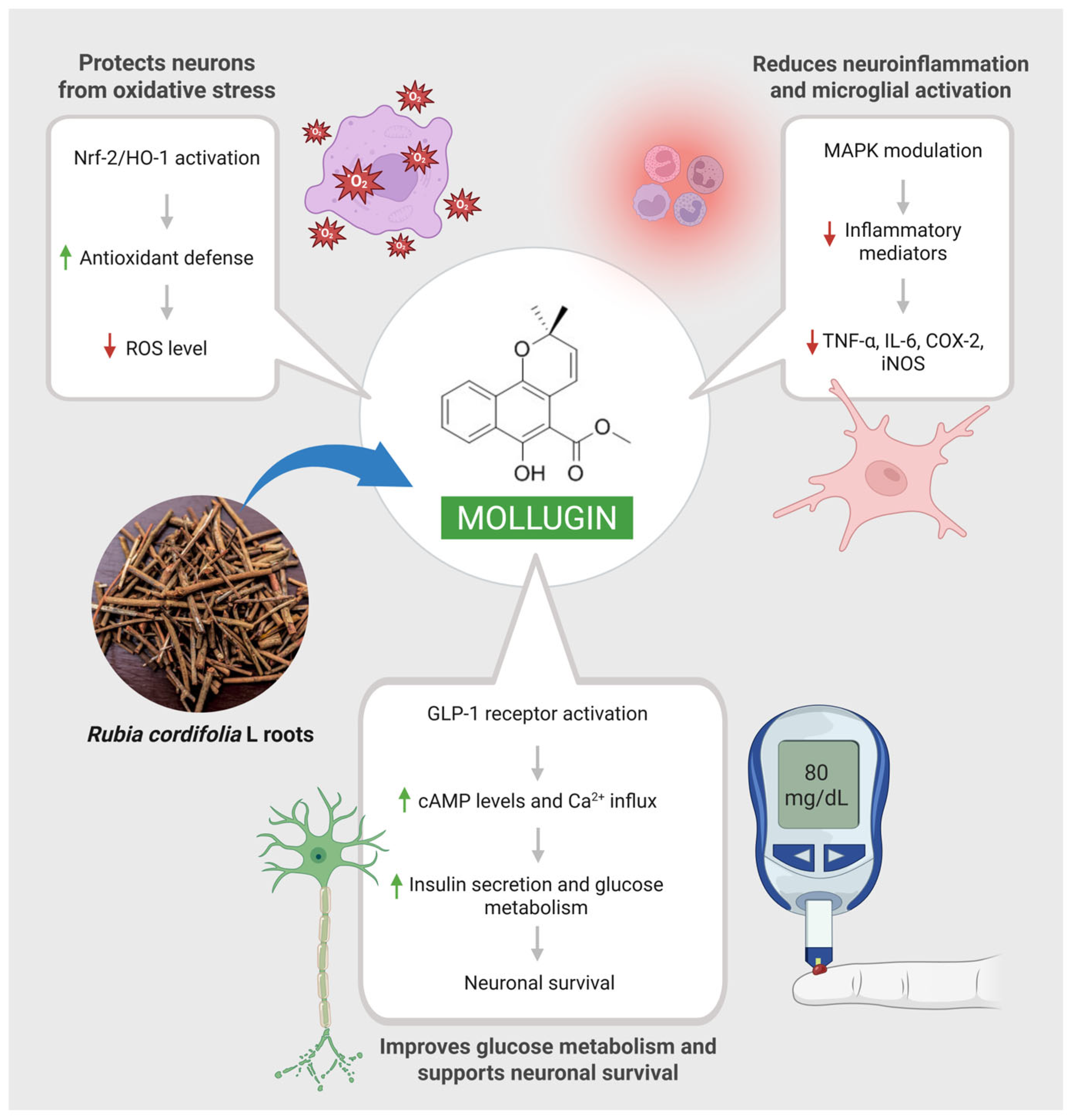

2.3. Neuroprotective Effects of Mollugin

2.4. Effects of Mollugin in Bone Regeneration and Resorption Suppression

2.5. Effects of Mollugin in Multidrug Resistance

2.6. Antimicrobial Effects of Mollugin

2.7. Antiadipogenic Effects of Mollugin

2.8. Effects of Mollugin in Ulcerative Colitis

2.9. Effects of Mollugin in Neurovascular Protection

2.10. Effects of Mollugin in Pain Modulation

3. Development of Mollugin Derivatives and Their Role

4. Pharmacokinetics and Toxicological Profile of Mollugin

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumar Patel, D. Notopterol for the Treatment of Human Disorders and Associated Secondary Complications: Concerns and Future Prospects. Eurasian J. Med. Adv. 2024, 4, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, R.; Sun, C.; Pan, Y. An effective high-speed countercurrent chromatographic method for preparative isolation and purification of mollugin directly from the ethanol extract of the Chinese medicinal plant Rubia cordifolia. J. Sep. Sci. 2007, 30, 1313–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Chen, Q.; Chen, W.; Yang, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, A.; Lai, J.; Chen, J.; Mei, Q.; et al. A comprehensive review of Rubia cordifolia L.: Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, and clinical applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 965390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, A.; Pakrashi, S.C. The Treatise on Indian Medicinal Plants; Publications & Information Directorate: Singapore, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, A.; Kumar, B.; Alam, P. RUBIA CORDIFOLIA—A REVIEW ON PHARMACONOSY AND PHYTOCHEMISTRY. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2016, 7, 2720. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, R.N.; Nayar, S.L. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants; Council of Scientific & Industrial Research: New Delhi, India, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Lumb, J.P.; Trauner, D. Pericyclic Reactions of Prenylated Naphthoquinones: Biomimetic Syntheses of Mollugin and Microphyllaquinone. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 5865–5868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem; National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 124219, Mollugin. 2025. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Mollugin (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Jeong, G.S.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, D.C.; Jahng, Y.; Son, J.K.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.C. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of mollugin via up-regulation of heme oxygenase-1 in mouse hippocampal and microglial cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 654, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.J.; Lee, J.S.; Kwak, M.-K.; Choi, H.G.; Yong, C.S.; Kim, J.A.; Lee, Y.R.; Lyoo, W.S.; Park, Y.J. Anti-inflammatory action of mollugin and its synthetic derivatives in HT-29 human colonic epithelial cells is mediated through inhibition of NF-κB activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 622, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claessens, S.; Kesteleyn, B.; Nguyen Van, T.; De Kimpe, N. Synthesis of mollugin. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 8419–8424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.I.; Jou, S.J.; Cheng, T.H.; Lin, C.N.; Ko, F.N.; Teng, C.M. Antiplatelet Constituents of Formosan Rubia akane. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, D.; Ohshiro, T.; Ohba, M.; Jiang, W.; Hong, B.; Si, S.; Tomoda, H. The Molecular Target of Rubimaillin in the Inhibition of Lipid Droplet Accumulation in Macrophages. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 32, 1317–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debela, D.T.; Muzazu, S.G.; Heraro, K.D.; Ndalama, M.T.; Mesele, B.W.; Haile, D.C.; Kitui, S.K.; Manyazewal, T. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211034366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diori Karidio, I.; Sanlier, S.H. Reviewing cancer’s biology: An eclectic approach. J. Egypt. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 33, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.M.; Pezzuto, J.M. Natural Products as a Vital Source for the Discovery of Cancer Chemotherapeutic and Chemopreventive Agents. Med. Princ. Pract. 2016, 25, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, S.T.; Acaroz, U.; Imre, K.; Morar, A.; Shah, S.R.A.; Hussain, S.Z.; Arslan-Acaroz, D.; Demirbas, H.; Hajrulai-Musliu, Z.; Istanbullugil, F.R.; et al. Natural Products/Bioactive Compounds as a Source of Anticancer Drugs. Cancers 2022, 14, 6203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z. Mollugin suppresses proliferation and drives ferroptosis of colorectal cancer cells through inhibition of insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding protein 3/glutathione peroxidase 4 axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 115427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.G.; Xiong, Y.Y.; Yu, B.; Yuan, C.; Chen, P.Y.; Yang, Y.F.; Wu, H.Z. Mollugin induced oxidative DNA damage via up-regulating ROS that caused cell cycle arrest in hepatoma cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 353, 109805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Xu, J.; Ding, K. Mollugin induces tumor cell apoptosis and autophagy via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/p70S6K and ERK signaling pathways. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, X.; Li, Y. Rubimaillin decreases the viability of human ovarian cancer cells via mitochondria-dependent apoptosis. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2019, 65, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.M.; Park, H.S.; Jun, D.Y.; Woo, H.J.; Woo, M.H.; Yang, C.H.; Kim, Y.H. Mollugin induces apoptosis in human Jurkat T cells through endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated activation of JNK and caspase-12 and subsequent activation of mitochondria-dependent caspase cascade regulated by Bcl-xL. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 241, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Do, M.T.; Hwang, Y.P.; Kim, H.G.; Na, M.; Jeong, H.G. Mollugin inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis by suppressing fatty acid synthase in HER2-overexpressing cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2013, 228, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tao, Y.; Xu, R.; Luo, W.; Lin, T.; Zhou, F.; Tang, L.; He, L.; He, Y. Analysis of active components and molecular mechanism of action of Rubia cordifolia L. in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma based on network pharmacology and experimental verification. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Mi, C.; Wang, K.; Ma, J.; Jin, X. Mollugin Has an Anti-Cancer Therapeutic Effect by Inhibiting TNF-α-Induced NF-κB Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.P.; Kim, H.G.; Choi, J.H.; Na, M.K.; Jeong, H.G. Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance is induced by mollugin in MCF-7/adriamycin cells. Phytomedicine 2013, 20, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wei, X.; Ma, M.; Jia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, W.; Wang, T.; Shi, X. FFJ-3 inhibits PKM2 protein expression via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and activates the mitochondrial apoptosis signaling pathway in human cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 2607–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Li, M.; Ma, M.; Jia, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, W.; Wang, T.; Shi, X. Induction of apoptosis by FFJ-5, a novel naphthoquinone compound, occurs via downregulation of PKM2 in A549 and HepG2 cells. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Luo, H.; Lv, Y.F.; Zhang, H.; Hu, J.M.; Li, H.M.; Liu, S.J. Synthesis and Antitumor Activity of 1-Substituted 1,2,3-Triazole-Mollugin Derivatives. Molecules 2021, 26, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, H.K.; Jeong, T.C.; Jahng, Y.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S. Selective inhibitory effects of mollugin on CYP1A2 in human liver microsomes. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvanová, G.; Duranková, S. Inflammatory process: Factors inducing inflammation, forms and manifestations of inflammation, immunological significance of the inflammatory reaction. Alergol. Pol.-Pol. J. Allergol. 2025, 12, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannoodee, S.; Nasuruddin, D.N. Acute Inflammatory Response; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fürst, R.; Zündorf, I. Plant-Derived Anti-Inflammatory Compounds: Hopes and Disappointments regarding the Translation of Preclinical Knowledge into Clinical Progress. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 146832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakadate, K.; Ito, N.; Kawakami, K.; Yamazaki, N. Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Plant-Derived Compounds and Prevention of Chronic Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.G.; Jin, H.; Yu, P.J.; Tian, Y.X.; Zhang, J.J.; Wu, S.G. Mollugin Inhibits the Inflammatory Response in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated RAW264.7 Macrophages by Blocking the Janus Kinase-Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription Signaling Pathway. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2013, 36, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, J.L.; Gong, X.P.; Xiao, M.; Song, Y.Y.; Pi, H.F.; Du, G. Anti-inflammatory Activity of Mollugin on DSS-induced Colitis in Mice. Curr. Med. Sci. 2020, 40, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.H.; Li, M.Y.; Wang, D.Y.; Jin, X.J.; Chen, F.E.; Piao, H.R. Synthesis and Evaluation of NF-κB Inhibitory Activity of Mollugin Derivatives. Molecules 2022, 27, 7925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shen, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, S.; Guo, L.; Li, J.; Wang, Y. Mollugin prevents CLP-induced sepsis in mice by inhibiting TAK1-NF-κB/MAPKs pathways and activating Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 125, 111079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, R.; Ding, H.; Gao, X.; Wei, Z.; Qi, T.; Fang, L. Mollugin ameliorates murine allergic airway inflammation by inhibiting Th2 response and M2 macrophage activation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 946, 175630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.L.; Li, M.Y.; Wang, D.Y.; Jin, S.A.; Ma, X.Y.; Jin, X.J.; Piao, H.R. Mollugin Derivatives as Anti-Inflammatory Agents: Design, Synthesis, and NF-κB Inhibition. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2024, 104, e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Tai, Y.; Li, J.X.; Han, J.; Liu, X.Z.; Cao, S.; Li, M.Y.; Zuo, H.X.; Xing, Y.; Ma, J.; et al. Mollugin inhibits IL-1β production by reducing zinc finger protein 91-regulated Pro-IL-1β ubiquitination and inflammasome activity. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 145, 113757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigbee, J.W. Cells of the Central Nervous System: An Overview of Their Structure and Function; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2023; pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, A.; Ouyang, J.; Nguyen, K.; Jones, A.; Basso, S.; Karasik, R. Traumatic brain injuries: A neuropsychological review. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1326115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekdemir, B.; Raposo, A.; Saraiva, A.; Lima, M.J.; Alsharari, Z.D.; BinMowyna, M.N.; Karav, S. Mechanisms and Potential Benefits of Neuroprotective Agents in Neurological Health. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Nagalakshmi, D.; Sharma, K.K.; Ravichandiran, V. Natural antioxidants for neuroinflammatory disorders and possible involvement of Nrf2 pathway: A review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, S.; Ansari, M.A.; Fatease, A.A.; Safhi, A.Y.; Hani, U.; Jahan, R.; Alomary, M.N.; Ansari, M.N.; Ahmed, N.; Wahab, S.; et al. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds in the Management of Neurodegenerative Disorders: Challenges, Future Directions and Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Neuroprotection. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cui, X.; Yan, W.; Liu, N.; Shang, J.; Yi, X.; Guo, T.; Wei, X.; Sun, Y.; Hu, H.; et al. Mollugin activates GLP-1R to improve cognitive dysfunction in type 2 diabetic mice. Life Sci. 2023, 331, 122026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözen, T.; Özışık, L.; Çalık Başaran, N. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 4, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, D.F.; Qin, L.Q.; Wang, P.Y.; Katoh, R. Soy isoflavone intake increases bone mineral density in the spine of menopausal women: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martiniakova, M.; Babikova, M.; Omelka, R. Pharmacological agents and natural compounds: Available treatments for osteoporosis. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2020, 71, 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.H.; Kim, I.; Kim, S.H. Mollugin enhances the osteogenic action of BMP-2 via the p38–Smad signaling pathway. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2017, 40, 1328–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, J.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Jung, Y.; Moon, S.H.; Choi, M.K.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, I.; Oh, J. Mollugin from Rubea cordifolia suppresses receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand-induced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorbing activity in vitro and prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced bone loss in vivo. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, M.M.; Fojo, T.; Bates, S.E. Multidrug resistance in cancer: Role of ATP–dependent transporters. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przedborski, S.; Vila, M.; Jackson-Lewis, V. Series Introduction: Neurodegeneration: What is it and where are we? J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhayawi, M.S.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Selim, S.; Alkhalifah, D.H.M.; Marc, R.A.; Aslam, S.; Poczai, P. Integrated Pangenome Analysis and Pharmacophore Modeling Revealed Potential Novel Inhibitors against Enterobacter xiangfangensis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idhayadhulla, A.; Xia, L.; Lee, Y.R.; Kim, S.H.; Wee, Y.J.; Lee, C.S. Synthesis of novel and diverse mollugin analogues and their antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Bioorg. Chem. 2014, 52, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, R.; Chakkour, M.; Zein El Dine, H.; Obaseki, E.F.; Obeid, S.T.; Jezzini, A.; Ghssein, G.; Ezzeddine, Z. General Overview of Klebsiella pneumonia: Epidemiology and the Role of Siderophores in Its Pathogenicity. Biology 2024, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, N.; Aiesh, B.M.; Jomaa, R.; Zouneh, Y.; Namrouti, A.; Abutaha, A.; Al-Jabi, S.W.; Sabateen, A.; Zyoud, S.H. Antibiotic resistance profiles and risk factors of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in a large tertiary care hospital in a low- and middle-income country. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, J.; Wang, D.; Zhou, T. Regulation of NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway attenuates the acute lung inflammation in Klebsiella pneumonia rats by mollugin treatment. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 132, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endale, M.; Alao, J.P.; Akala, H.M.; Rono, N.K.; Eyase, F.L.; Derese, S.; Ndakala, A.; Mbugua, M.; Walsh, D.S.; Sunnerhagen, P.; et al. Antiplasmodial Quinones from Pentas longiflora and Pentas lanceolata. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Z.; Wu, H. Isolation of anthraquinone derivatives from Rubia cordifolia (Rubiaceae) and their bioactivities against plant pathogenic microorganisms. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 4617–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. An overview of obesity-related complications: The epidemiological evidence linking body weight and other markers of obesity to adverse health outcomes. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantopoulos, C.N.; Banyard, D.A.; Ziegler, M.E.; Sun, B.; Shaterian, A.; Widgerow, A.D. Elucidating the Preadipocyte and Its Role in Adipocyte Formation: A Comprehensive Review. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2018, 4, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, D.Y.; Han, C.R.; Choi, M.S.; Bae, M.A.; Woo, M.H.; Kim, Y.H. Effect of mollugin on apoptosis and adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart, D.C. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2009, 106, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugliak Cleveland, N.; Torres, J.; Rubin, D.T. What Does Disease Progression Look Like in Ulcerative Colitis, and How Might It Be Prevented? Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1396–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Cheng, C.; Au, R.; Tong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cui, Y.; Fang, Y.; Chen, H.; et al. Qin-Yu-Qing-Chang decoction reshapes colonic metabolism by activating PPAR-γ signaling to inhibit facultative anaerobes against DSS-induced colitis. Chin. Med. 2024, 19, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, D.; Patil, C.G. Epidemiology and the Global Burden of Stroke. World Neurosurg. 2011, 76, S85–S90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candelario-Jalil, E.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Magnus, T. Neuroinflammation, Stroke, Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction, and Imaging Modalities. Stroke 2022, 53, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Nan, J.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, L. Mollugin attenuates oxygen-glucose deprivation/reperfusion-induced brain microvascular endothelial cell death and permeability through activation of BDNF/TrkB-modulated Akt pathway. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2025, 57, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, W.; Jiang, Z.; Fan, F. Analgesic action of Rubimaillin in vitro and in vivo. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2020, 66, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandrowski, K.U.; Sharafshah, A.; Elfar, J.; Schmidt, S.L.; Blum, K.; Wetzel, F.T. A Pharmacogenomics-Based In Silico Investigation of Opioid Prescribing in Post-operative Spine Pain Management and Personalized Therapy. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 44, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, H.; Nishino, H.; Nakajima, Y.; Kakubari, Y.; Nakata, A.; Deguchi, J.; Nugroho, A.E.; Hirasawa, Y.; Kaneda, T.; Kawasaki, Y.; et al. Oxomollugin, a potential inhibitor of lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide production including nuclear factor kappa B signals. J. Nat. Med. 2015, 69, 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, H.; Nakajima, Y.; Kakubari, Y.; Asami, N.; Deguchi, J.; Nugroho, A.E.; Hirasawa, Y.; Kaneda, T.; Kawasaki, Y.; Goda, Y.; et al. Syntheses and anti-inflammatory activity of azamollugin derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 524–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, Y.; Tsuboi, N.; Katori, K.; Waili, M.; Nugroho, A.E.; Takahashi, K.; Nishino, H.; Hirasawa, Y.; Kawasaki, Y.; Goda, Y.; et al. Oxomollugin, an oxidized substance in mollugin, inhibited LPS-induced NF-κB activation via the suppressive effects on essential activation factors of TLR4 signaling. J. Nat. Med. 2024, 78, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, Y.; Nishino, H.; Takahashi, K.; Nugroho, A.E.; Hirasawa, Y.; Kaneda, T.; Morita, H. Azamollugin, a mollugin derivative, has inhibitory activity on MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways. J. Nat. Med. 2025, 79, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.B.; Kim, D.; Kim, B.K.; Woo, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Han, S.H.; Bae, G.U.; Kang, S. CF3-Substituted Mollugin 2-(4-Morpholinyl)-ethyl ester as a Potential Anti-inflammatory Agent with Improved Aqueous Solubility and Metabolic Stability. Molecules 2018, 23, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.M.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, G.Z.; Song, W.W.; Chen, X.Q.; Li, X.N.; Tan, N.H. New Cytotoxic Naphthohydroquinone Dimers from Rubia alata. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 5576–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Kuang, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Yang, C. Simultaneous Determination of Purpurin, Munjistin and Mollugin in Rat Plasma by Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry: Application to a Pharmacokinetic Study after Oral Administration of Rubia cordifolia L. Extract. Molecules 2016, 21, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 4, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Disease | Animal Model | Effects | Mechanism | Mollugin Dosage | Duration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | Male mice, xylene-induced ear edema (20 μL) | Mollugin derivatives inhibit NF-κB transcription and reduce inflammation | Downregulates NF-κB signaling pathway, inhibits LPS-induced expression of p65 | 100 mg/kg, 0.1 mL/20 g body weight | 24 h | [41] |

| Colorectal cancer | Male nude mice (5–6 weeks old), xenografted with DLD-1 cells (2 × 106 cells in 200 μL PBS) | Limits proliferation, induces lipid peroxidation, and drives ferroptosis of CRC cells | ↑ ROS, Fe2+, MDA ↓ IGF2BP3, GPX4, GSH | 75 mg/kg once per day i.g, and/or i.p injected with Fer-1 (10 mg/kg, once every other day) | - | [18] |

| Allergic airway inflammation | 6- to 8-week-old female C57BL/6 mice, induced with shrimp tropomyosin combined with Al (OH)3 (1.25 mg), i.p: 20 μg on days 0, 7, 14; intratracheal instillation: 40 μg on day 21 | Reduces airway inflammation, mucus secretion, eosinophil infiltration, and Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13) | Targets p38 MAPK and PARP1 → inhibits M2 macrophage activation and IL-5 expression | 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg i.p | From day 19 to 25 | [40] |

| Diabetic cognitive dysfunction | 8-week-old male C57BL/6 mice, injected STZ (60 mg/kg, i.p) for 3 consecutive days | Improves cognition, lowered ROS level, and apoptosis | Activates GLP-1R → cAMP/PKA pathway → ↑ Ca2+ influx, ↓ Pik3ca/Akt1/Mapk1 | 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg per day, p.o | 6 weeks | [48] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 6- to 8-week-old BALB/c male mice, s.c injected 1.0 × 106 cells per mouse on the right forelimb armpit | Inhibits HepG2 cell tumor growth by inducing DNA damage and S phase arrest | ↑ ROS → DNA damage (↑ p-H2AX) → S phase cell cycle arrest (cyclin A2, CDK2) → tumor inhibition | 25 mg/kg (low dose), 50 mg/kg (medium dose), 75 mg/kg (high dose), i.g | 14 days | [19] |

| Ulcerative colitis | 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 male mice, induced by administering 3% DSS solution as drinking water | Reduces weight loss, colon injury, and disease activity index | Downregulates IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, acts through TLR4-independent NF-κB suppression pathway | 10, 20, 40 mg/kg, p.o | 10 days | [37] |

| Klebsiella pneumonia | Sprague Dawley rats of either sex, induced by administering Klebsiella pneumoniae solution (0.1 mL), orotracheal incubation | Lowers WBC and PMN count in blood, reduces lung inflammation and bleeding, suppresses inflammatory cell infiltration and alveolar wall thickness | Inhibits NF-κB pathway ↓ inflammatory response Blocks MAPK pathway ↓ immune damage, regulates lung inflammation | 80 mg/kg, p.o | 7 days | [60] |

| Cervical cancer | BALB/c female athymic nude mice, s.c injected 0.2 mL HeLa cells (5 × 107 cells/mL) | Suppresses tumor growth | Inhibits NF-κB activation, prevents p65 entry into nucleus and breakdown of IκBα, inhibits IKK phosphorylation, suppresses cancer gene expression | Given three times a week as an oral suspension of mollugin in saline at a dose of 25 and 75 mg/kg body weight | - | [25] |

| Bone loss/osteoclast-related disorder | ICR mice, induced with LPS (5 mg/kg, i.p) on day 1 and 4 | Inhibits osteoclast differentiation, prevents LPS-induced bone loss, suppresses F-actin ring formation | ↓ RANKL-induced phosphorylation of ERK, JNK, p38, AKT, GSK3β, ↓ c-FOS and NFATc1, ↓ OSCAR, TRAP, DC-STAMP, integrins, CtsK, reduces osteoclast activity and bone resorption | 100 mg/kg, p.o | 8 days | [53] |

| Property | Predicted Value | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Intestinal absorption | 93.697% | Predicted (pkCSM) |

| Volume of distribution | 0.216 log L/kg | Predicted (pkCSM) |

| BBB permeability | 0.541 log BB | Predicted (pkCSM) |

| CNS permeability | −1.844 log PS | Predicted (pkCSM) |

| Total clearance | 0.629 log mL/min/kg | Predicted (pkCSM) |

| Maximum tolerated human dose | 0.42 log mg/kg/day | Predicted (pkCSM) |

| LD50 | 2.459 mol/kg | Predicted (pkCSM) |

| LOAEL | 2.11 log mg/kg_bw/day | Predicted (pkCSM) |

| Cmax | 52.10 ± 6.71 ng/mL | Rodent experimental model [80] |

| Tmax | 1.99 ± 0.21 h | Rodent experimental model [80] |

| t1/2 | 9.02 ± 2.14 h | Rodent experimental model [80] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olakkengil Shajan, S.R.; Zia, B.; Sharma, C.; Subramanya, S.B.; Ojha, S. Mollugin: A Comprehensive Review of Its Multifaceted Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12003. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412003

Olakkengil Shajan SR, Zia B, Sharma C, Subramanya SB, Ojha S. Mollugin: A Comprehensive Review of Its Multifaceted Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12003. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412003

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlakkengil Shajan, Sandra Ross, Bushra Zia, Charu Sharma, Sandeep B. Subramanya, and Shreesh Ojha. 2025. "Mollugin: A Comprehensive Review of Its Multifaceted Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Potential" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12003. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412003

APA StyleOlakkengil Shajan, S. R., Zia, B., Sharma, C., Subramanya, S. B., & Ojha, S. (2025). Mollugin: A Comprehensive Review of Its Multifaceted Pharmacological Properties and Therapeutic Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12003. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412003