Copper(II) Complexes with 4-Substituted 2,6-Bis(thiazol-2-yl)pyridines—An Overview of Structural–Optical Relationships

Abstract

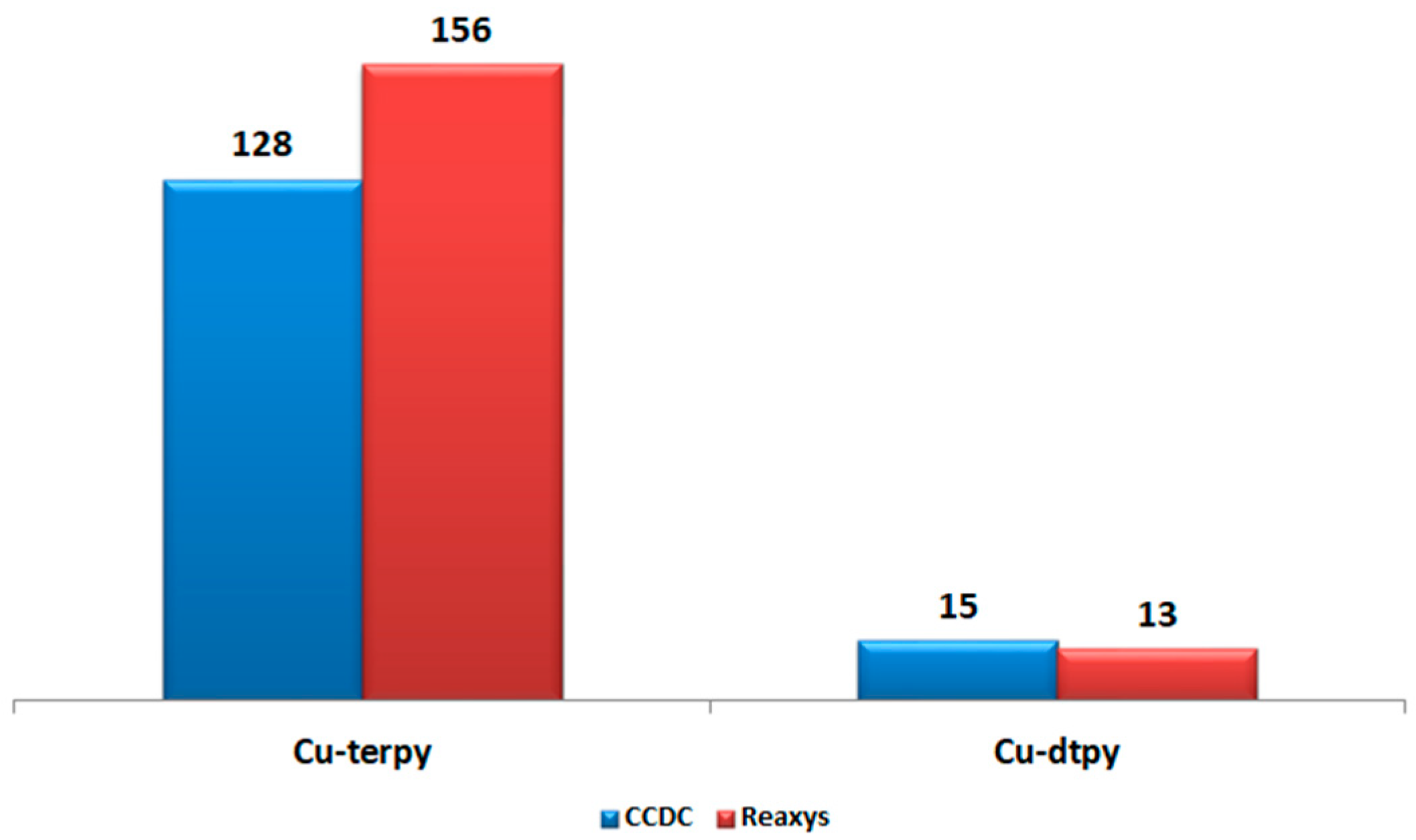

1. Introduction

2. Results

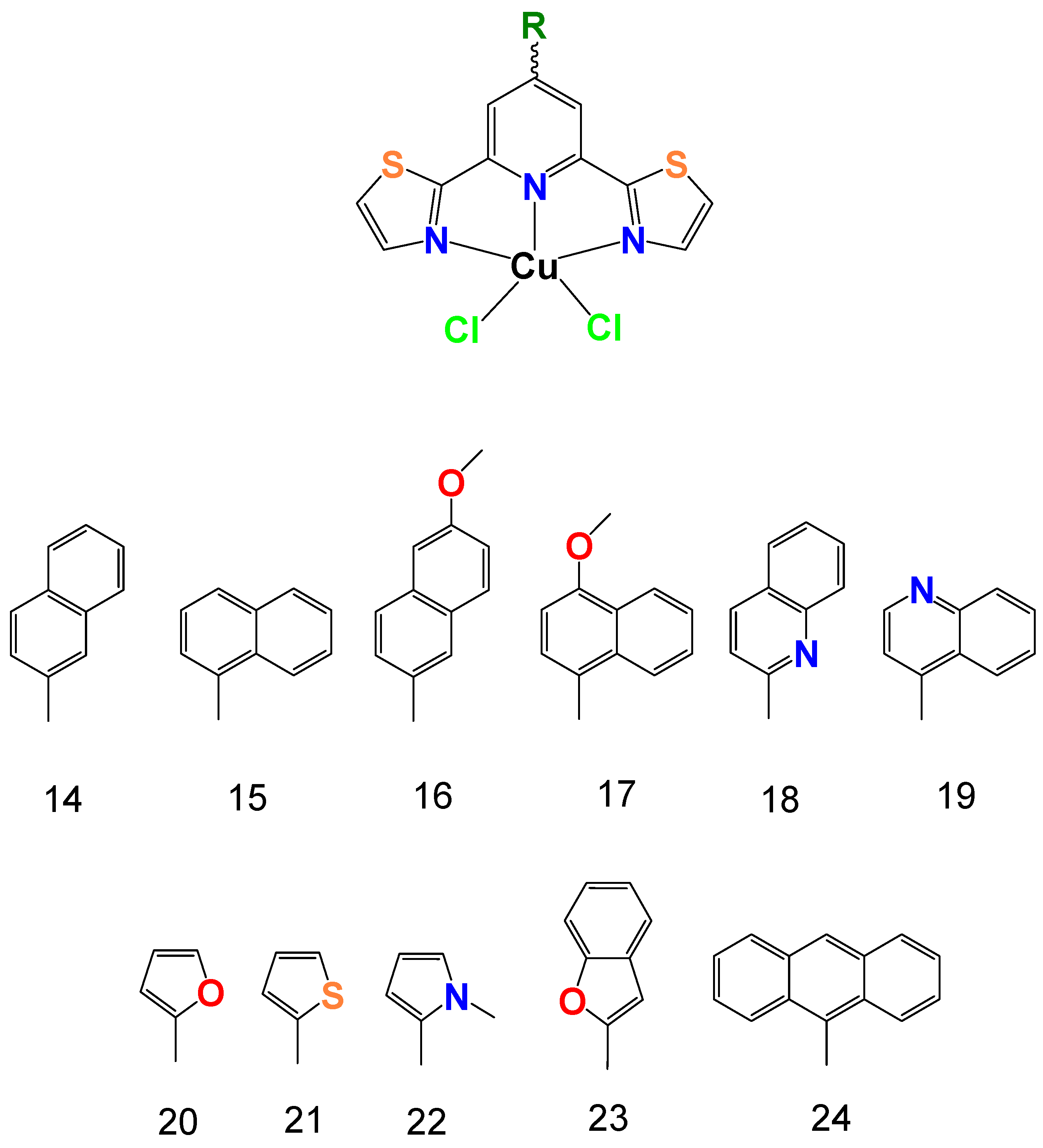

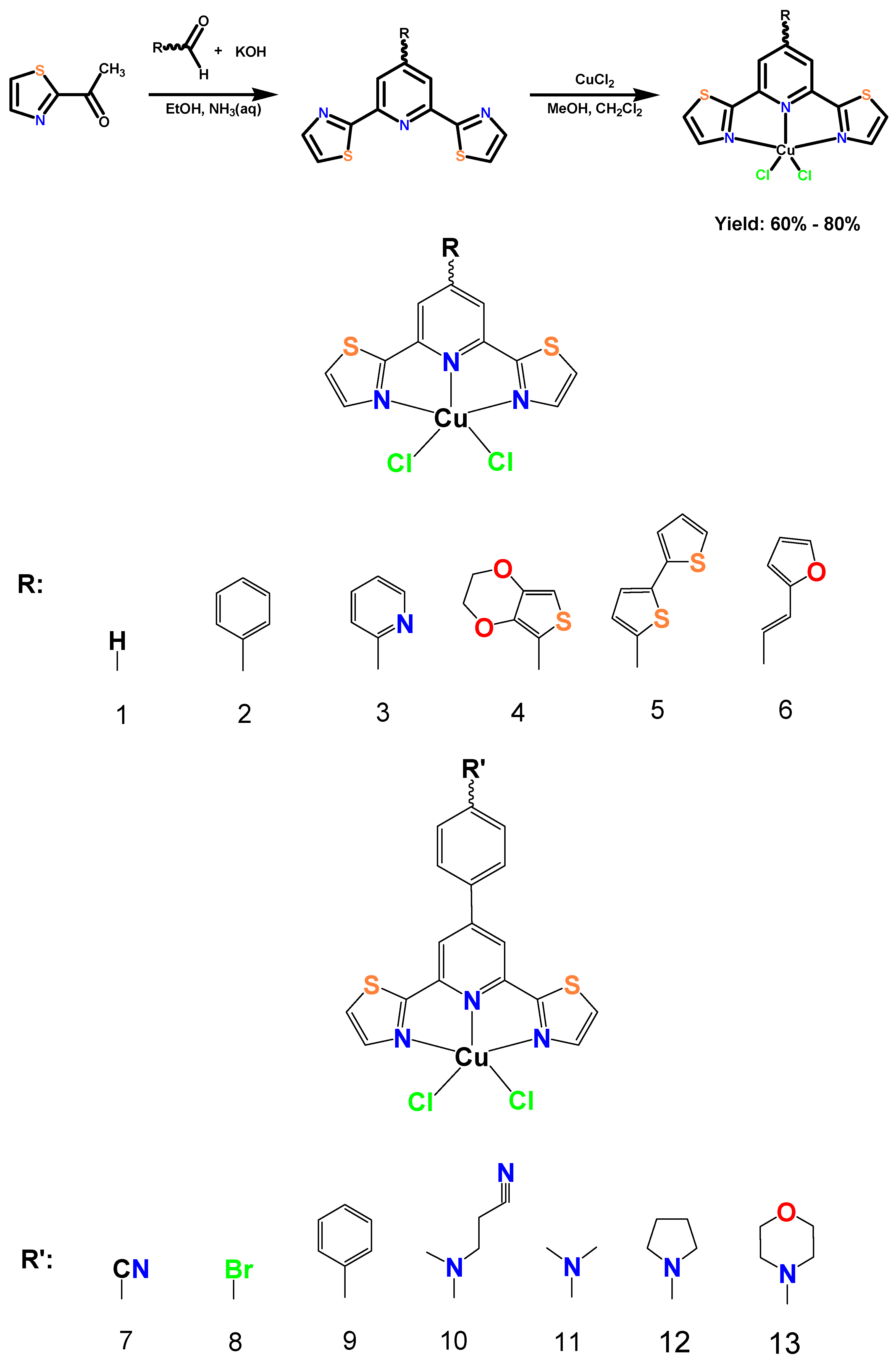

2.1. Synthesis and General Characterization

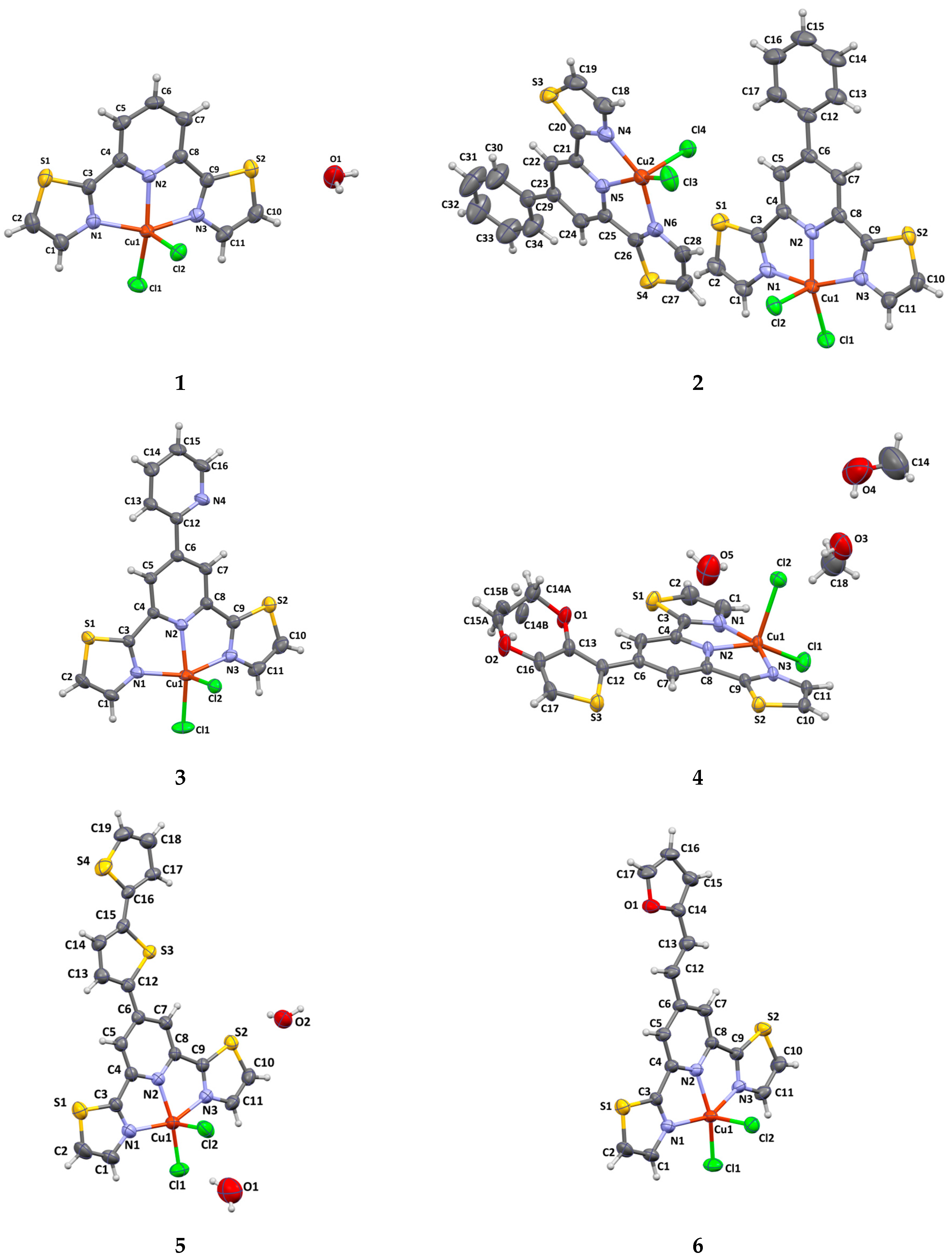

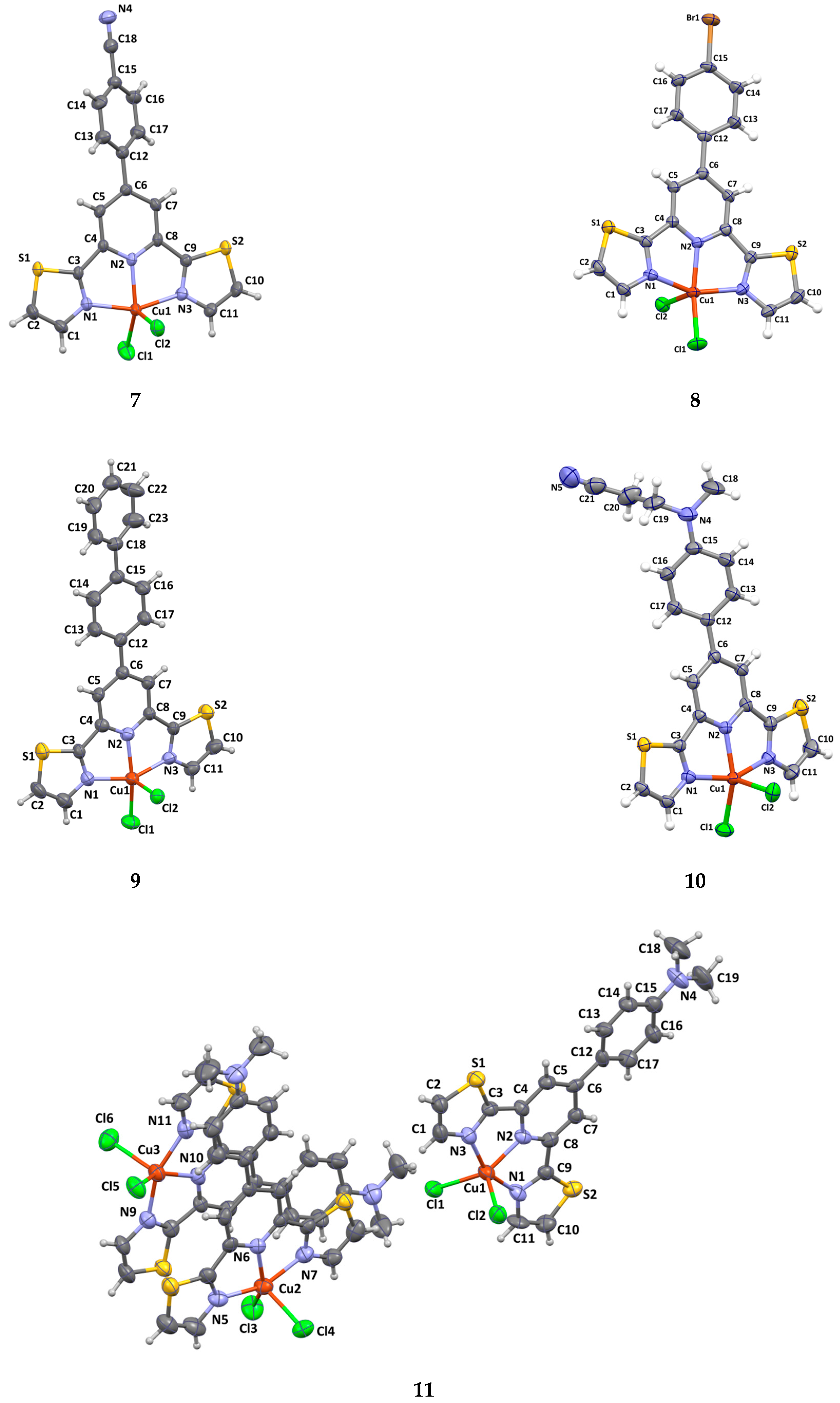

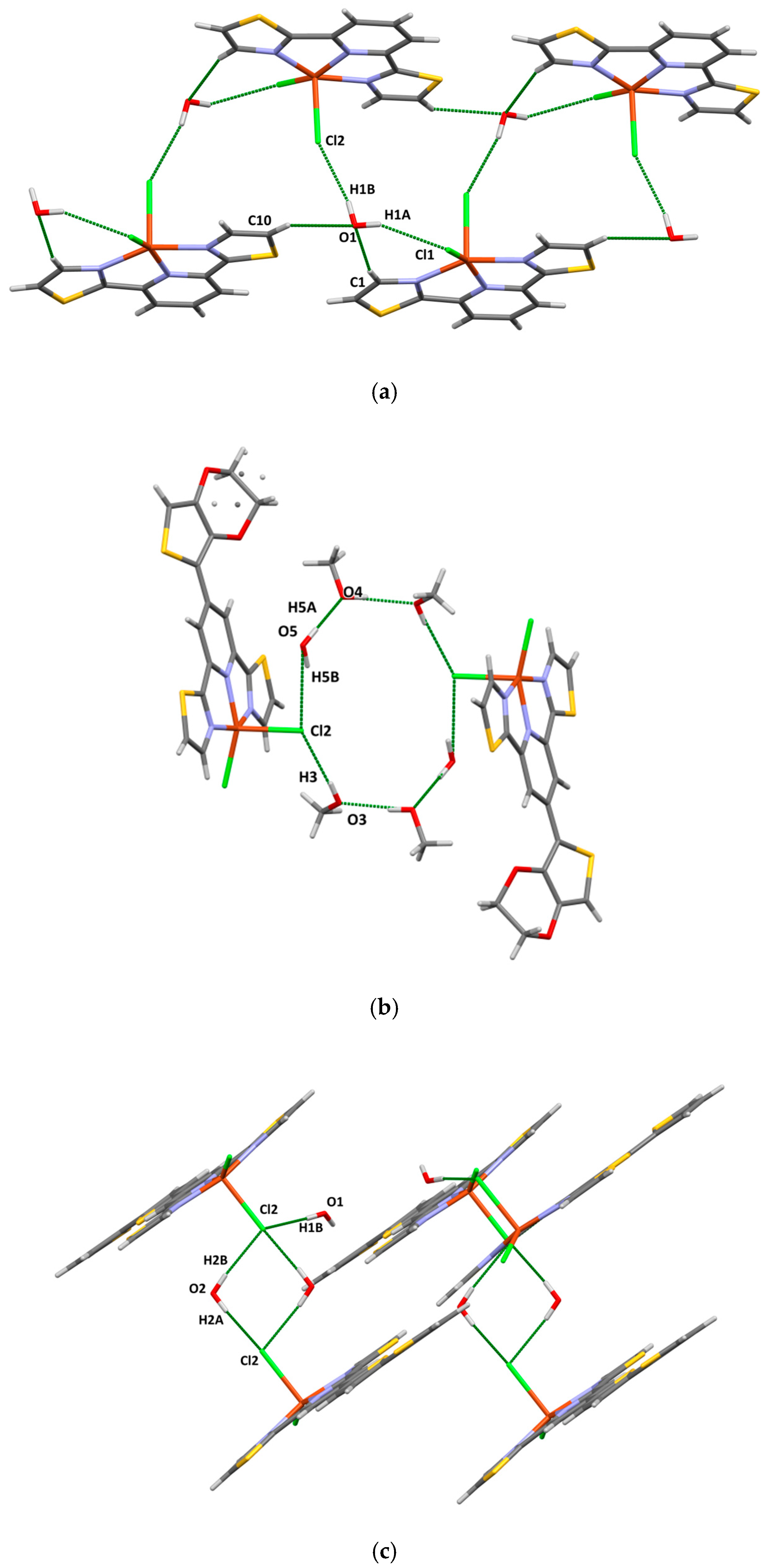

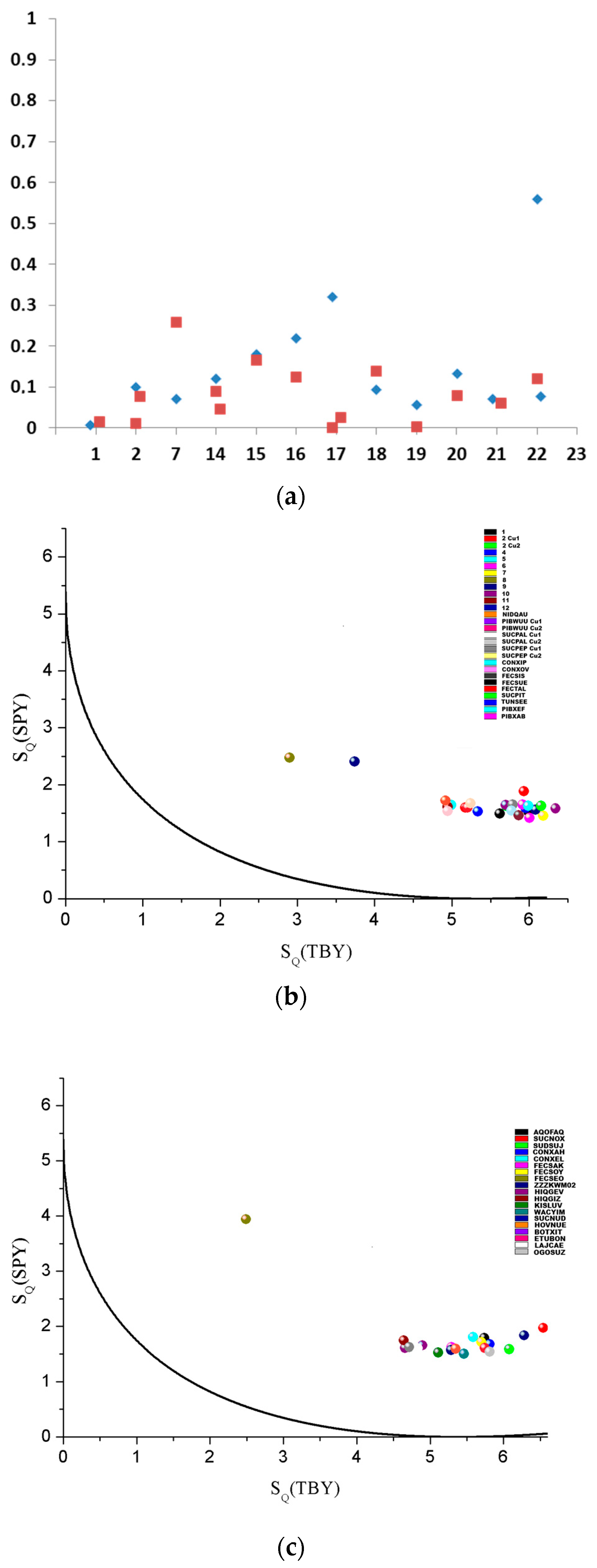

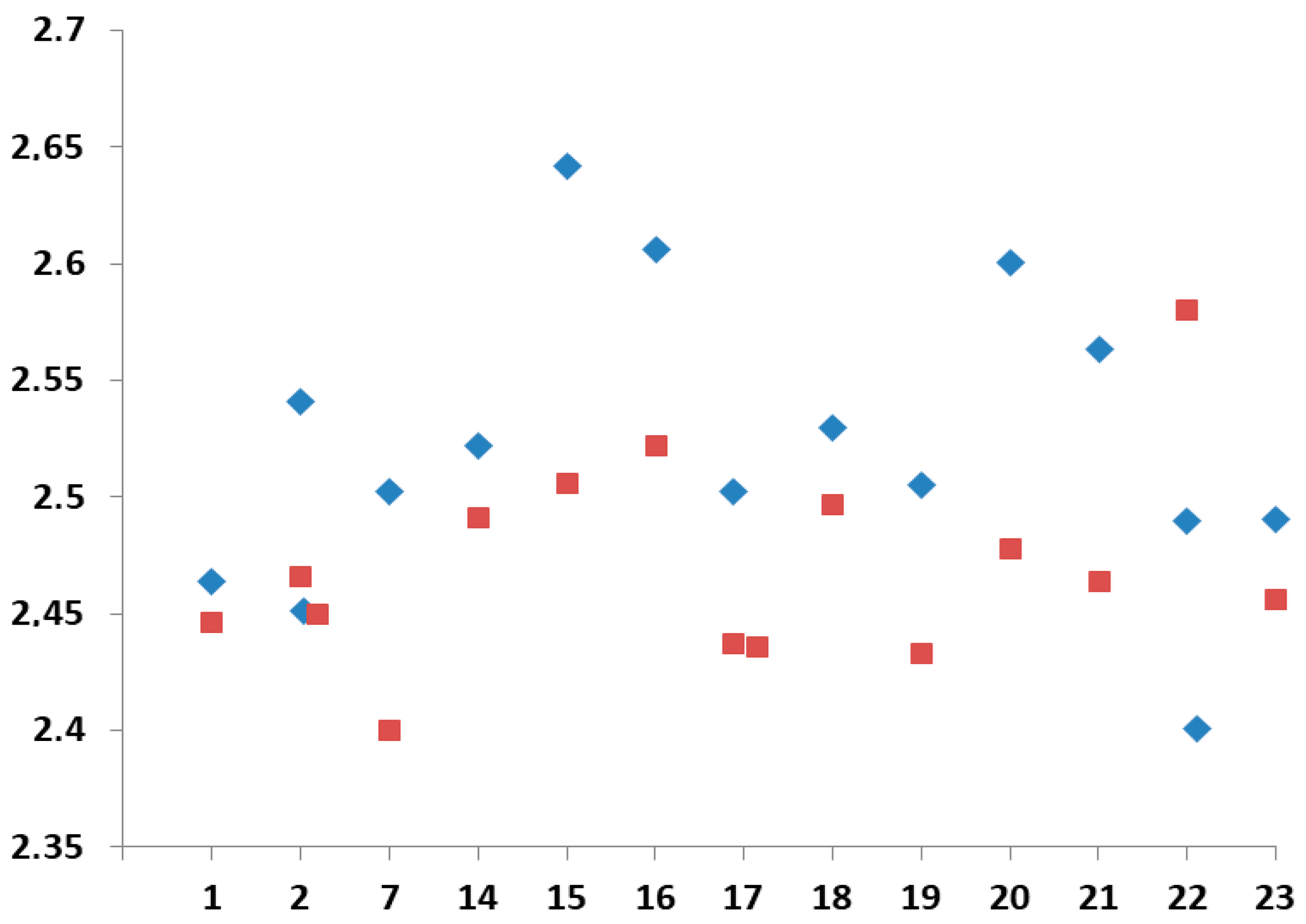

2.2. X-Ray Analysis

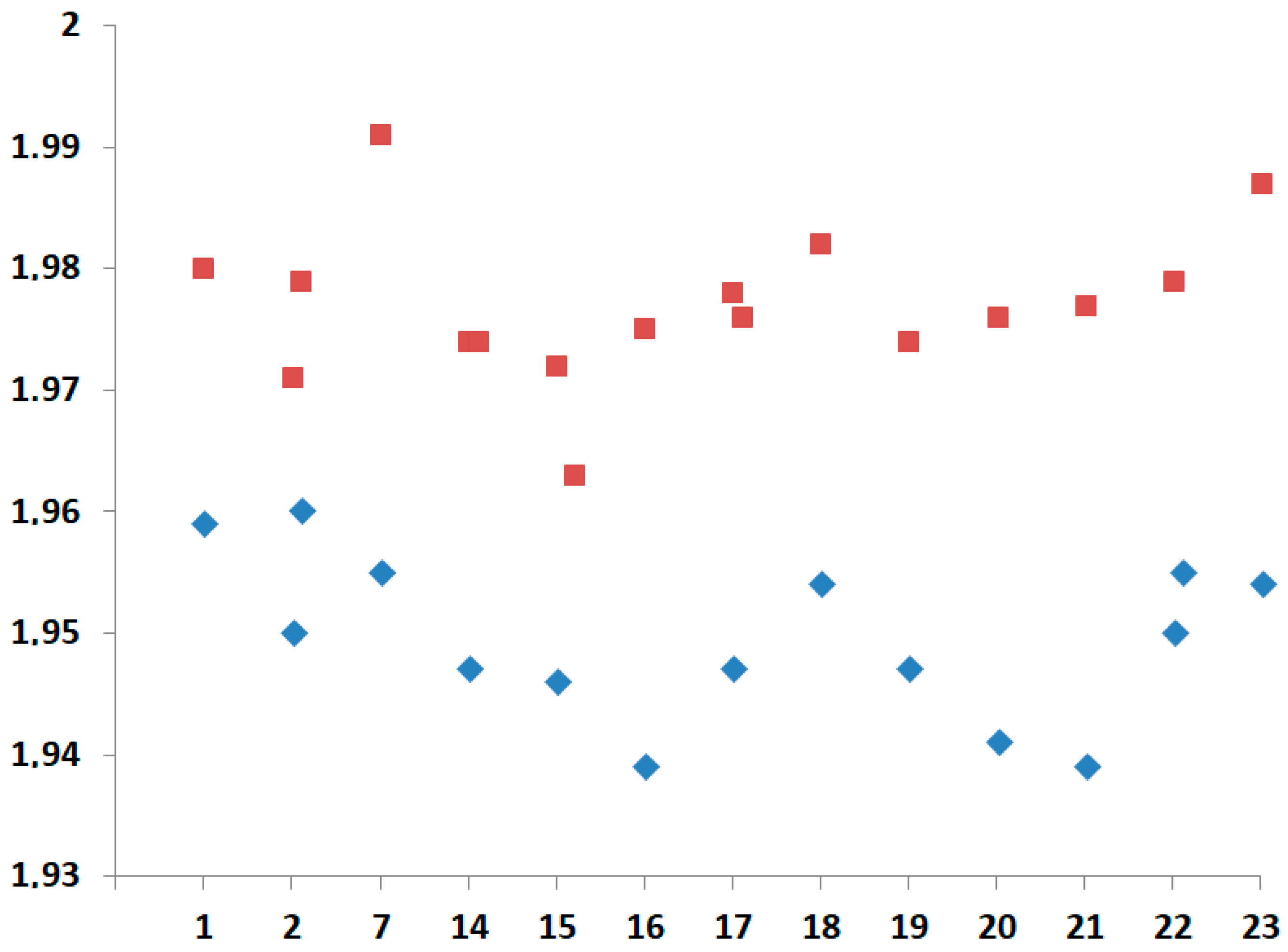

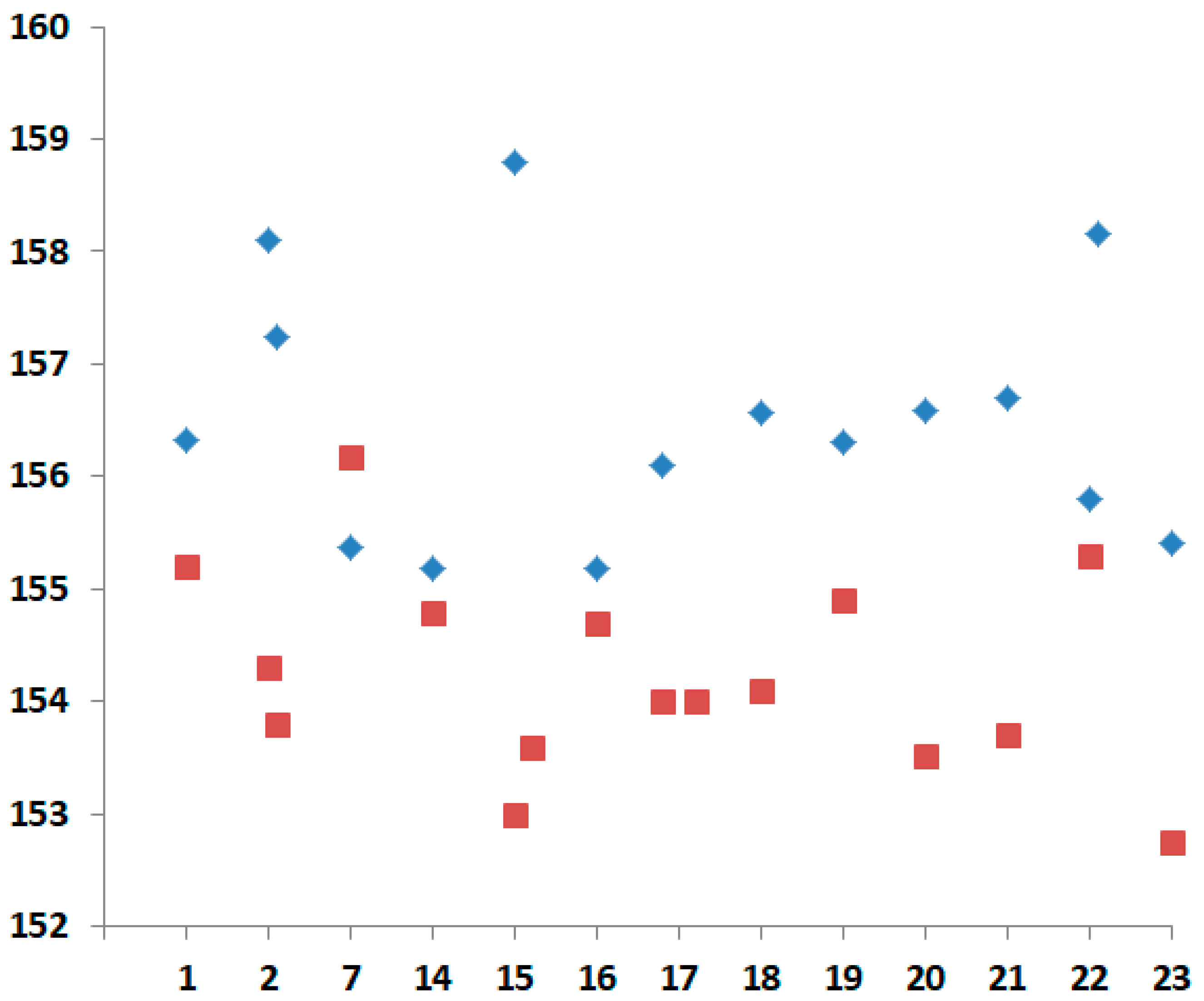

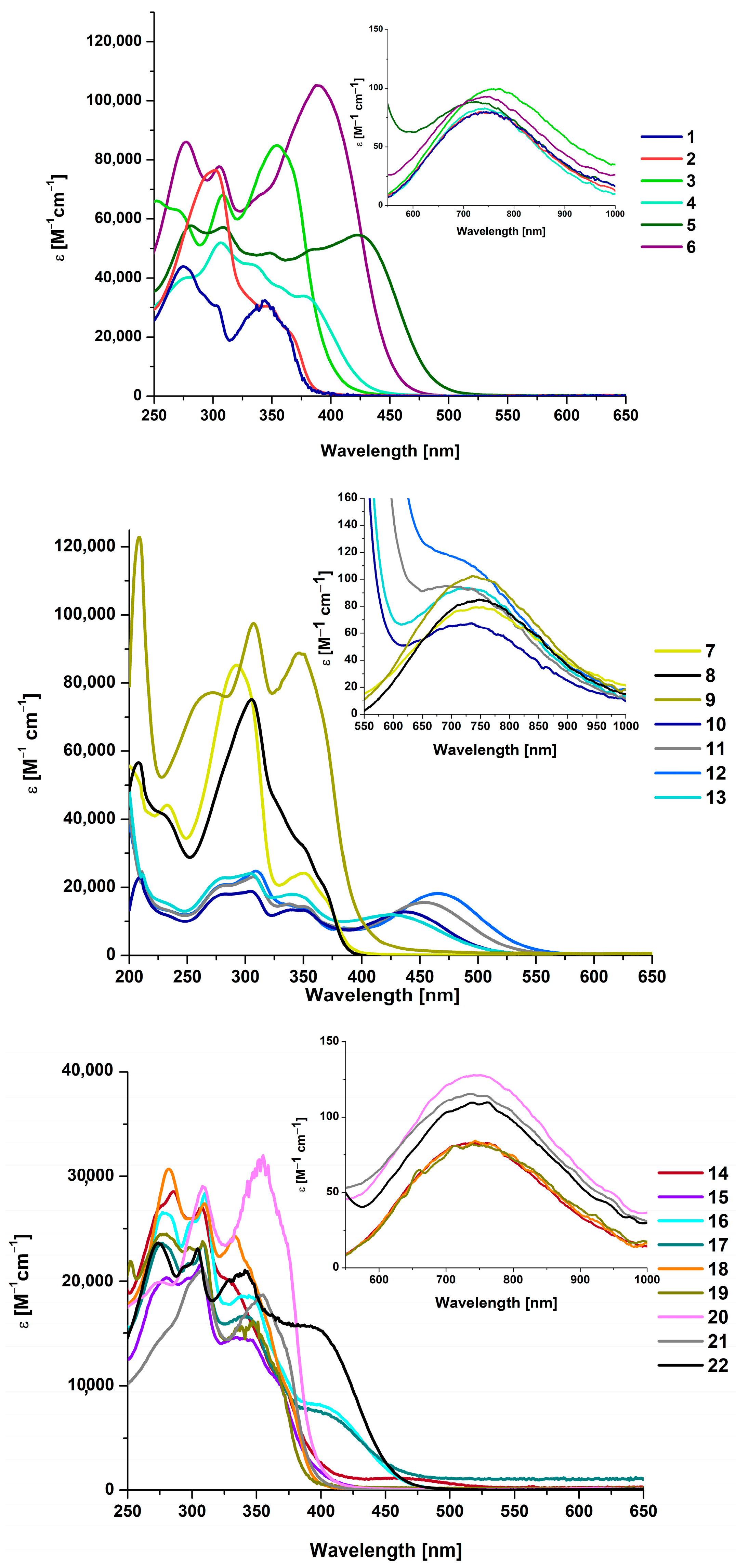

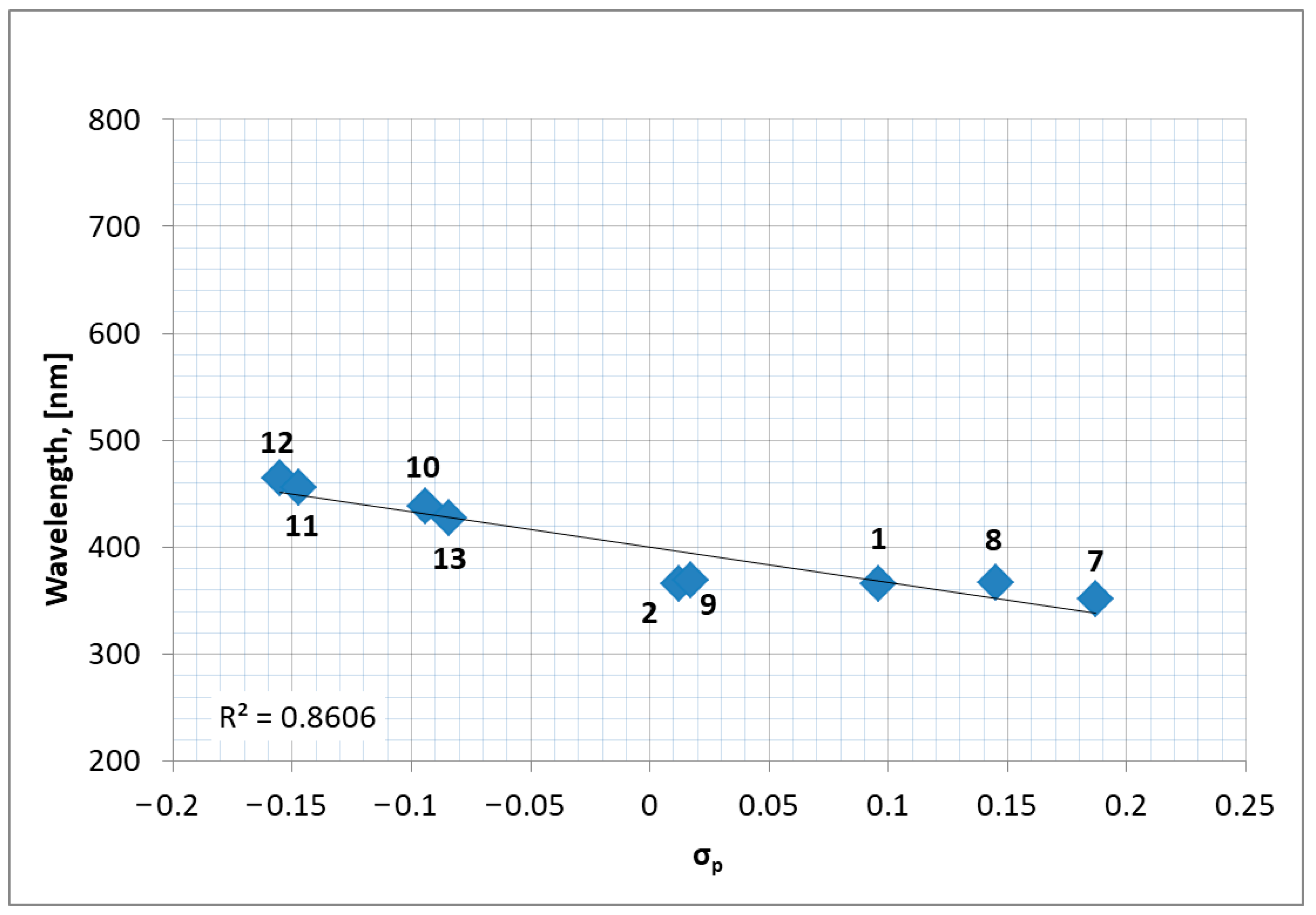

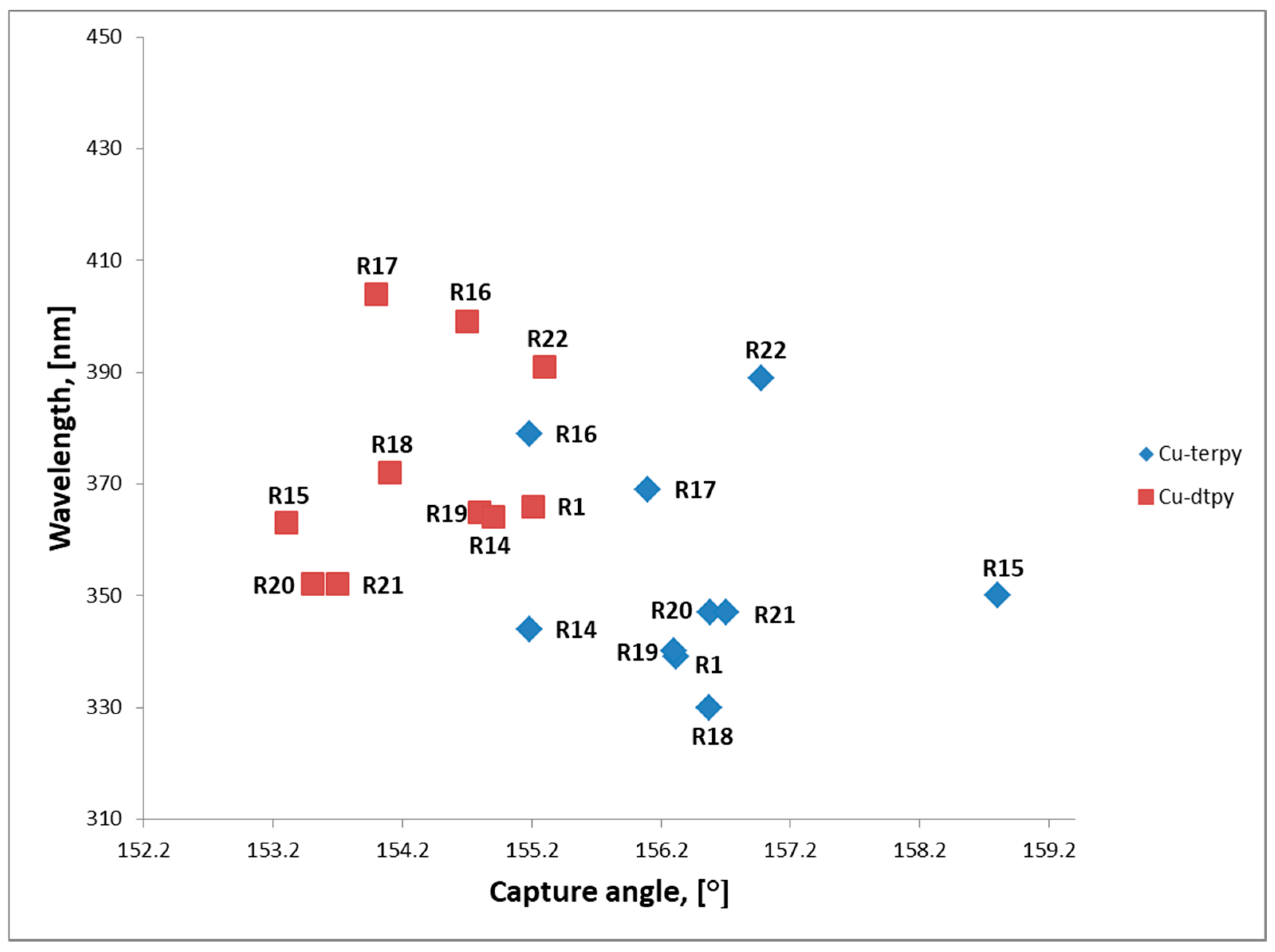

2.3. Optical Properties

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Synthesis Procedure for [CuCl2Ln]

3.2. Instrumentation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tapiero, H.; Townsend, D.M.; Tew, K.D. Trace Elements in Human Physiology and Pathology. Copper. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2003, 57, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.T.; Misra, S.R.; Hussain, M. Nutritional Aspects of Essential Trace Elements in Oral Health and Disease: An Extensive Review. Scientifica 2016, 2016, 5464373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, L.M.; Libedinsky, A.; Elorza, A.A. Role of Copper on Mitochondrial Function and Metabolism. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 711227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, T.; Davis, C.I.; Brady, D.C. Copper Biology. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R421–R427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, N.M.; Swaminathan, A.B.; Maremanda, K.P.; Zulkifli, M.; Gohil, V.M. Mitochondrial Copper in Human Genetic Disorders. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 34, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, J.; Aizenman, E. The Physiological and Pathophysiological Roles of Copper in the Nervous System. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2024, 60, 3505–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerone, S.I.; Sansinanea, A.S.; Streitenberger, S.A.; Garcia, M.C.; Auza, N.J. Cytochrome c Oxidase, Cu,Zn-Superoxide Dismutase, and Ceruloplasmin Activities in Copper-Deficient Bovines. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2000, 73, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, C.; Rios, E.; Olivos, J.; Brunser, O.; Olivares, M. Iron, Copper and Immunocompetence. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, S24–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandamathavan, V.M.; Thangaraj, M.; Weyhermuller, T.; Parameswari, R.P.; Punitha, V.; Murthy, N.N.; Nair, B.U. Novel Mononuclear Cu (II) Terpyridine Complexes: Impact of Fused Ring Thiophene and Thiazole Head Groups towards DNA/BSA Interaction, Cleavage and Antiproliferative Activity on HepG2 and Triple Negative CAL-51 Cell Line. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 135, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, N.; Lippard, S.J. Redox Activation of Metal-Based Prodrugs as a Strategy for Drug Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, Y.P.; Piasta, K.; Khomenko, D.M.; Doroshchuk, R.O.; Shova, S.; Novitchi, G.; Toporivska, Y.; Gumienna-Kontecka, E.; Martins, L.M.D.R.S.; Lampeka, R.D. An Investigation of Two Copper(II) Complexes with a Triazole Derivative as a Ligand: Magnetic and Catalytic Properties. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 23442–23449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomenko, I.S.; Gongola, M.I.; Shul’pina, L.S.; Shul’pin, G.B.; Ikonnikov, N.S.; Kozlov, Y.N.; Gushchin, A.L. Copper(II) Complexes with BIAN-Type Ligands: Synthesis and Catalytic Activity in Oxidation of Hydrocarbons and Alcohols. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2024, 565, 121990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Arora, A.; Maikhuri, V.K.; Chaudhary, A.; Kumar, R.; Parmar, V.S.; Singh, B.K.; Mathur, D. Advances in Chromone-Based Copper(II) Schiff Base Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Versatile Applications in Pharmacology and Biomimetic Catalysis. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 17102–17139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwińska, K.; Machura, B.; Kula, S.; Krompiec, S.; Erfurt, K.; Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Fernandes, A.R.; Shul’pina, L.S.; Ikonnikov, N.S.; Shul’pin, G.B. Copper(II) Complexes of Functionalized 2,2′:6′,2′′-Terpyridines and 2,6-Di(Thiazol-2-Yl)Pyridine: Structure, Spectroscopy, Cytotoxicity and Catalytic Activity. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 9591–9604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choroba, K.; Machura, B.; Kula, S.; Raposo, L.R.; Fernandes, A.R.; Kruszynski, R.; Erfurt, K.; Shul’pina, L.S.; Kozlov, Y.N.; Shul’pin, G.B. Copper(II) Complexes with 2,2′:6′,2′′-Terpyridine, 2,6-Di(Thiazol-2-Yl)Pyridine and 2,6-Di(Pyrazin-2-Yl)Pyridine Substituted with Quinolines. Synthesis, Structure, Antiproliferative Activity, and Catalytic Activity in the Oxidation of Alkanes and Alcohols with Peroxides. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 12656–12673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choroba, K.; Zowiślok, B.; Kula, S.; Machura, B.; Maroń, A.M.; Erfurt, K.; Marques, C.; Cordeiro, S.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R. Optimization of Antiproliferative Properties of Triimine Copper(II) Complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 19475–19502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.D. Platinum Complexes of Terpyridine: Interaction and Reactivity with Biomolecules. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 1495–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; He, Y.; Shi, X.; Song, Z. Terpyridine-Metal Complexes: Applications in Catalysis and Supramolecular Chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 385, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, A.; Schubert, U.S. Metal-Terpyridine Complexes in Catalytic Application—A Spotlight on the Last Decade. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 2890–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, J.J.; Roy, S. Recent Development of Copper (II) Complexes of Polypyridyl Ligands in Chemotherapy and Photodynamic Therapy. ChemMedChem 2023, 18, e202200652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Moles, M.; Concepción Gimeno, M. The Therapeutic Potential in Cancer of Terpyridine-Based Metal Complexes Featuring Group 11 Elements. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202300645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalewicz, B.; Czylkowska, A. Recent Advances in the Discovery of Copper(II) Complexes as Potential Anticancer Drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 292, 117702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Du, K.; Wang, Y.; Jia, H.; Hou, X.; Chao, H.; Ji, L. Self-Activating Nuclease and Anticancer Activities of Copper(II) Complexes with Aryl-Modified 2,6-Di(Thiazol-2-Yl)Pyridine. Dalton Trans. 2013, 42, 11576–11588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-Y.; Du, K.-J.; Wang, J.-Q.; Liang, J.-W.; Kou, J.-F.; Hou, X.-J.; Ji, L.-N.; Chao, H. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, DNA Interaction and Anticancer Activity of Tridentate Copper(II) Complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013, 119, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammam, A.M.; Ibrahim, S.A.; El-Gahami, M.A.; Fouad, D. Investigations of Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) (2,2’:6’,2”2”-Terpyridine) Complexes With Sulfur Donor Ligands. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2003, 74, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-H.; Zhang, M.-H.; Gao, C.-Y.; Wang, L.-T. Synthesis, Structures and Characterization of Metal Complexes Containing 4′-Phenyl-2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridine Ligands with Extended Π⋯π Interactions. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2013, 408, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroń, A.; Czerwińska, K.; Machura, B.; Raposo, L.; Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Fernandes, A.R.; Małecki, J.G.; Szlapa-Kula, A.; Kula, S.; Krompiec, S. Spectroscopy, Electrochemistry and Antiproliferative Properties of Au(III), Pt(II) and Cu(II) Complexes Bearing Modified 2,2′:6′,2′′-Terpyridine Ligands. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 6444–6463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.N.; Desai, D.H.; Patel, N.C. Synthesis, Spectral, and Single Crystal XRD Studies of Novel Terpyridine Derivatives of Benzofuran-2-Carbaldehyde and Their Cu(II) Complex. Russ. J. Coord. Chem. 2021, 47, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, R.; Luo, B.; Yang, D.; Chen, H.; Pan, L.; Ma, Z. Copper Chloride Complexes with Substituted 4′-Phenyl-Terpyridine Ligands: Synthesis, Characterization, Antiproliferative Activities and DNA Interactions. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 8243–8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo, T.; Vlasse, M.; Beltran-Porter, D. The Structure of Dicholoro(2,2′:6′,2′′-Terpyridyl)Copper(II) Monohydrate, [Cu(C15H11N3)Cl2].H2O. Acta Cryst. C 1983, 39, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, W.; Kremer, S.; Reinen, D. Copper(2+) in Five-Coordination: A Case of a Pseudo-Jahn-Teller Effect. 1. Structure and Spectroscopy of the Compounds Cu(Terpy)X2.nH2O. Inorg. Chem. 1983, 22, 2858–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandamathavan, V.M.; Rajapandian, V.; Freddy, A.J.; Weyhermüller, T.; Subramanian, V.; Nair, B.U. Effect of Coordinated Ligands on Antiproliferative Activity and DNA Cleavage Property of Three Mononuclear Cu(II)-Terpyridine Complexes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 57, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraskevopoulos, J.N.; Smith, P.J.; Hoppe, H.C.; Chopra, D.; Govender, T.; Kruger, H.G.; Maguire, G.E.M. Terpyridyl Complexes as Antimalarial Agents. S. Afr. J. Chem. 2013, 66, 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pal, P.; Das, K.; Hossain, A.; Frontera, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S. Supramolecular and Theoretical Perspectives of 2,2′:6′,2′′-Terpyridine Based Ni(II) and Cu(II) Complexes: On the Importance of C–H⋯Cl and Π⋯π Interactions. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 7310–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Zhou, Y.; Karges, J.; Du, K.; Shen, J.; Lin, M.; Kou, J.; Chen, Y.; Chao, H. CCDC 2078509: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination; Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC): Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, K.; Zhou, Y.; Karges, J.; Du, K.; Shen, J.; Lin, M.; Wei, F.; Kou, J.; Chen, Y.; Ji, L.; et al. Autophagy-Dependent Apoptosis Induced by Apoferritin–Cu(II) Nanoparticles in Multidrug-Resistant Colon Cancer Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 38959–38968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Wei, L.; Alegria, E.C.B.A.; Martins, L.M.D.R.S.; Silva, M.F.C.G.d.; Pombeiro, A.J.L. Synthesis and Characterization of Copper(II) 4′-Phenyl-Terpyridine Compounds and Catalytic Application for Aerobic Oxidation of Benzylic Alcohols. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 4048–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, S.; Ghosh, B.N.; Rissanen, K. Transition Metal Ion Induced Hydrogelation by Amino-Terpyridine Ligands. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 8836–8839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karges, J.; Xiong, K.; Blacque, O.; Chao, H.; Gasser, G. Highly Cytotoxic Copper(II) Terpyridine Complexes as Anticancer Drug Candidates. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2021, 516, 120137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beves, J.E.; Constable, E.C.; Decurtins, S.; Dunphy, E.L.; Housecroft, C.E.; Keene, T.D.; Neuburger, M.; Schaffner, S.; Zampese, J.A. Structural Diversity in the Reactions of 4′-(Pyridyl)-2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridine Ligands and Bis{4′-(4-Pyridyl)-2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridine}iron(II) with Copper(II) Salts. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 2406–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavasi, H.R.; Esmaeili, M. Case Study of the Correlation between Metallogelation Ability and Crystal Packing. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 4369–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, L.; Stoeckli-Evans, H. CCDC 679674: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination; Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC): Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, P.N.; Rajalakshmi, S.; Chadha, A. CCDC 1525024: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination; Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC): Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rawji, G.; Fritz, C.; Nguyen, T.; Lynch, V. CCDC 952841: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination; Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC): Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Choroba, K.; Kula, S.; Maroń, A.; Machura, B.; Małecki, J.; Szłapa-Kula, A.; Siwy, M.; Grzelak, J.; Maćkowski, S.; Schab-Balcerzak, E. Aryl Substituted 2,6-Di(Thiazol-2-Yl)Pyridines –Excited-State Characterization and Potential for OLEDs. Dye. Pigment. 2019, 169, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choroba, K.; Machura, B.; Raposo, L.R.; Małecki, J.G.; Kula, S.; Pająk, M.; Erfurt, K.; Maroń, A.M.; Fernandes, A.R. Platinum(II) Complexes Showing High Cytotoxicity toward A2780 Ovarian Carcinoma Cells. Dalton Trans. 2019, 48, 13081–13093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.-Q.; Ren, N.; Zhang, J.-J. Syntheses, Crystal Structures, Luminescence and Thermal Properties of Three Lanthanide Complexes with 2-Bromine-5-Methoxybenzoate and 2,2:6′,2″-Terpyridine. Polyhedron 2018, 144, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, P.C.; Manna, A.K. Synthesis of Heteroleptic Terpyridyl Complexes of Fe(II) and Ru(II): Optical and Electrochemical Studies. New J. Chem. 2016, 40, 5775–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, S.; Basu, S.; Jana, B.; Dastidar, P. Real-Time Observation of Macroscopic Helical Morphologies under Optical Microscope: A Curious Case of π–π Stacking Driven Molecular Self-Assembly of an Organic Gelator Devoid of Hydrogen Bonding. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, W.-D.; Wang, F.-Q.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, C.; Yan, J. Four New Terpyridine Complexes Based Polyoxometalates with [W10O32]4– Anions as High-Efficiency Dual-Site Catalysis for Thioether Oxidation Reaction†. Chin. J. Chem. 2024, 42, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małecka, M.; Szlapa-Kula, A.; Maroń, A.M.; Ledwon, P.; Siwy, M.; Schab-Balcerzak, E.; Sulowska, K.; Maćkowski, S.; Erfurt, K.; Machura, B. Impact of the Anthryl Linking Mode on the Photophysics and Excited-State Dynamics of Re(I) Complexes [ReCl(CO)3(4′-An-Terpy-κ2N)]. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 15070–15084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addison, A.W.; Rao, T.N.; Reedijk, J.; van Rijn, J.; Verschoor, G.C. Synthesis, Structure, and Spectroscopic Properties of Copper(II) Compounds Containing Nitrogen–Sulphur Donor Ligands; the Crystal and Molecular Structure of Aqua [1,7-Bis(N -Methylbenzimidazol-2′-Yl)-2,6-Dithiaheptane]Copper(II) Perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llunell, M.; Casanova, D.; Cirera, J.; Alemany, P.; Gómez-Ruiz, S. SHAPE Program; University of Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cirera, J.; Ruiz, E.; Alvarez, S. Continuous Shape Measures as a Stereochemical Tool in Organometallic Chemistry. Organometallics 2005, 24, 1556–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, D.; Llunell, M.; Alemany, P.; Alvarez, S. The Rich Stereochemistry of Eight-Vertex Polyhedra: A Continuous Shape Measures Study. Chem. A Eur. J. 2005, 11, 1479–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhang, G.; Phoenix, T.; Zheng, S.; Fettinger, J.C. Assembling Mono-, Di- and Tri-Nuclear Coordination Complexes with a Ditopic Analogue of 2,2′:6′,2′′-Terpyridine: Syntheses, Structures and Catalytic Studies. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 36156–36166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Bruno, I.J.; Chisholm, J.A.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R.; van de Streek, J.; Wood, P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0—New Features for the Visualization and Investigation of Crystal Structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spek, A.L. PLATON SQUEEZE: A Tool for the Calculation of the Disordered Solvent Contribution to the Calculated Structure Factors. Acta Cryst. C 2015, 71, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, P. A Web Tool for Calculating Substituent Descriptors Compatible with Hammett Sigma Constants. Chem. Methods 2022, 2, e202200041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemens, T.; Czerwińska, K.; Szlapa-Kula, A.; Kula, S.; Świtlicka, A.; Kotowicz, S.; Siwy, M.; Bednarczyk, K.; Krompiec, S.; Smolarek, K.; et al. Synthesis, Spectroscopic, Electrochemical and Computational Studies of Rhenium(I) Tricarbonyl Complexes Based on Bidentate-Coordinated 2,6-Di(Thiazol-2-Yl)Pyridine Derivatives. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 9605–9620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemens, T.; Świtlicka, A.; Szlapa-Kula, A.; Krompiec, S.; Lodowski, P.; Chrobok, A.; Godlewska, M.; Kotowicz, S.; Siwy, M.; Bednarczyk, K.; et al. Experimental and Computational Exploration of Photophysical and Electroluminescent Properties of Modified 2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridine, 2,6-Di(Thiazol-2-Yl)Pyridine and 2,6-Di(Pyrazin-2-Yl)Pyridine Ligands and Their Re(I) Complexes. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2018, 32, e4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemens, T.; Świtlicka, A.; Szlapa-Kula, A.; Łapok, Ł.; Obłoza, M.; Siwy, M.; Szalkowski, M.; Maćkowski, S.; Libera, M.; Schab-Balcerzak, E.; et al. Tuning Optical Properties of Re(I) Carbonyl Complexes by Modifying Push–Pull Ligands Structure. Organometallics 2019, 38, 4206–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palion-Gazda, J.; Machura, B.; Klemens, T.; Szlapa-Kula, A.; Krompiec, S.; Siwy, M.; Janeczek, H.; Schab-Balcerzak, E.; Grzelak, J.; Maćkowski, S. Structure-Dependent and Environment-Responsive Optical Properties of the Trisheterocyclic Systems with Electron Donating Amino Groups. Dye. Pigment. 2019, 166, 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemens, T.; Świtlicka, A.; Machura, B.; Kula, S.; Krompiec, S.; Łaba, K.; Korzec, M.; Siwy, M.; Janeczek, H.; Schab-Balcerzak, E.; et al. A Family of Solution Processable Ligands and Their Re(I) Complexes towards Light Emitting Applications. Dye. Pigment. 2019, 163, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroń, A.M.; Choroba, K.; Pedzinski, T.; Machura, B. Towards Better Understanding of the Photophysics of Platinum(II) Coordination Compounds with Anthracene- and Pyrene-Substituted 2,6-Bis(Thiazol-2-Yl)Pyridines. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 13440–13448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Małecka, M.; Machura, B.; Świtlicka, A.; Kotowicz, S.; Szafraniec-Gorol, G.; Siwy, M.; Szalkowski, M.; Maćkowski, S.; Schab-Balcerzak, E. Towards Better Understanding of Photophysical Properties of Rhenium(I) Tricarbonyl Complexes with Terpy-like Ligands. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 231, 118124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, D.; Slodek, A.; Małecki, J.G. 2,2′:6′,2′′-Terpyridine Derivative with Tetrazole Motif and Its Analogues with 2-Pyrazinyl or 2-Thiazolyl Substituents—Experimental and Theoretical Investigations. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1205, 127669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Chen, Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, D.; Ji, L.; Chao, H. Cyclometalated Ruthenium(II) Anthraquinone Complexes Exhibit Strong Anticancer Activity in Hypoxic Tumor Cells. Chem. A Eur. J. 2015, 21, 15308–15319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choroba, K.; Kotowicz, S.; Maroń, A.; Świtlicka, A.; Szłapa-Kula, A.; Siwy, M.; Grzelak, J.; Sulowska, K.; Maćkowski, S.; Schab-Balcerzak, E.; et al. Ground- and Excited-State Properties of Re(I) Carbonyl Complexes—Effect of Triimine Ligand Core and Appended Heteroaromatic Groups. Dye. Pigment. 2021, 192, 109472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.; Jones, R.A.; Holliday, B.J. Incorporation of Spin-Crossover Cobalt(II) Complexes into Conducting Metallopolymers: Towards Redox-Controlled Spin Change. Polymer 2021, 222, 123658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choroba, K.; Maroń, A.; Świtlicka, A.; Szłapa-Kula, A.; Siwy, M.; Grzelak, J.; Maćkowski, S.; Pedzinski, T.; Schab-Balcerzak, E.; Machura, B. Carbazole Effect on Ground- and Excited-State Properties of Rhenium(I) Carbonyl Complexes with Extended Terpy-like Ligands. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 3943–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malarz, K.; Zych, D.; Gawecki, R.; Kuczak, M.; Musioł, R.; Mrozek-Wilczkiewicz, A. New Derivatives of 4′-Phenyl-2,2′:6′,2′′-Terpyridine as Promising Anticancer Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 212, 113032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlis PRO, version 40; Oxford Diffraction/Agilent Technologies UK Ltd.: Yarnton, UK, 2014.

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal Structure Refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | τ | SQ(SPY) | SQ(TBY) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.101 | 1.522 | 5.990 |

| 2 | 0.012 (Cu1) 0.078 (Cu2) | 1.598 (Cu1) 1.628 (Cu2) | 5.171 (Cu1) 5.704 (Cu2) |

| 3 | 0.124 | 1.594 | 5.955 |

| 4 | 0.001 | 1.647 | 4.990 |

| 5 | 0.113 | 1.651 | 5.914 |

| 6 | 0.117 | 1.455 | 6.180 |

| 7 | 0.258 | 2.475 | 2.900 |

| 8 | 0.110 | 1.559 | 6.084 |

| 9 | 0.121 | 1.581 | 6.340 |

| 10 | 0.026 | 1.612 | 4.946 |

| 11 | 0.230 (Cu1) 0.162 (Cu2) 0.194 (Cu3) | 2.495 (Cu1) 2.423 (Cu2) 2.405 (Cu3) | 3.512 (Cu1) 3.808 (Cu2) 3.738 (Cu3) |

| Complex | Dihedral Angle Between Thiazole and Pyridine Rings | Dihedral Angle Between Substituent Plane and Pyridine Rings | Distance of Cu(II) Ion to the Basal Plane |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.82/0.66 | – | 0.32 |

| 2 | 4.57/6.80 (Cu1) 1.65/4.86 (Cu2) | 4.93 (Cu1) 9.96 (Cu2) | 0.334 (Cu1) 0.360 (Cu2) |

| 3 | 3.74/5.79 | 6.32 | 0.276 |

| 4 | 5.05/7.81 | 25.37 | 0.348 |

| 5 | 2.41/8.35 | 3.33 | 0.269 |

| 6 | 0.88/5.29 | 5.24 | 0.331 |

| 7 | 4.83/5.85 | 32.38 | 0.465 |

| 8 | 0.24/7.74 | 8.57 | 0.306 |

| 9 | 5.47/5.80 | 8.71 | 0.322 |

| 10 | 4.36/5.99 | 23.02 | 0.407 |

| 11 | 0.99/2.47 (Cu1) 1.14/3.31 (Cu2) 2.18/2.38 (Cu2) | 7.88 3.21 7.86 | 0.446 (Cu1) 0.414 (Cu2) 0.439 (Cu3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maroń, A.M.; Świtlicka, A.; Szłapa-Kula, A.; Choroba, K.; Erfurt, K.; Siwy, M.; Machura, B. Copper(II) Complexes with 4-Substituted 2,6-Bis(thiazol-2-yl)pyridines—An Overview of Structural–Optical Relationships. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11868. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411868

Maroń AM, Świtlicka A, Szłapa-Kula A, Choroba K, Erfurt K, Siwy M, Machura B. Copper(II) Complexes with 4-Substituted 2,6-Bis(thiazol-2-yl)pyridines—An Overview of Structural–Optical Relationships. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11868. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411868

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaroń, Anna Maria, Anna Świtlicka, Agata Szłapa-Kula, Katarzyna Choroba, Karol Erfurt, Mariola Siwy, and Barbara Machura. 2025. "Copper(II) Complexes with 4-Substituted 2,6-Bis(thiazol-2-yl)pyridines—An Overview of Structural–Optical Relationships" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11868. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411868

APA StyleMaroń, A. M., Świtlicka, A., Szłapa-Kula, A., Choroba, K., Erfurt, K., Siwy, M., & Machura, B. (2025). Copper(II) Complexes with 4-Substituted 2,6-Bis(thiazol-2-yl)pyridines—An Overview of Structural–Optical Relationships. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11868. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411868