Exploring Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Glucosidase II: Advances, Challenges, and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer and Viral Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Glucosidase II: Structure and Function

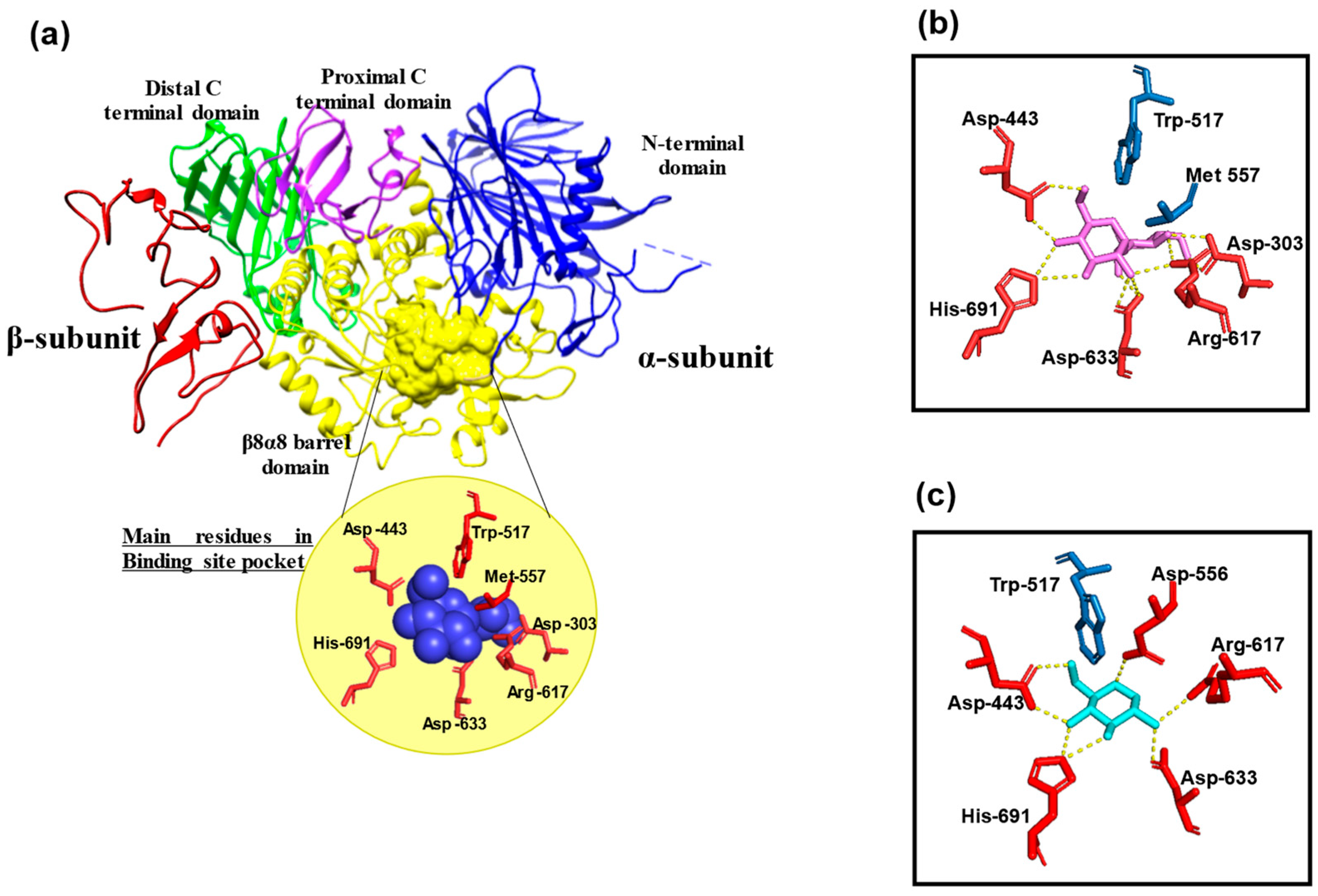

2.1. Molecular Structure

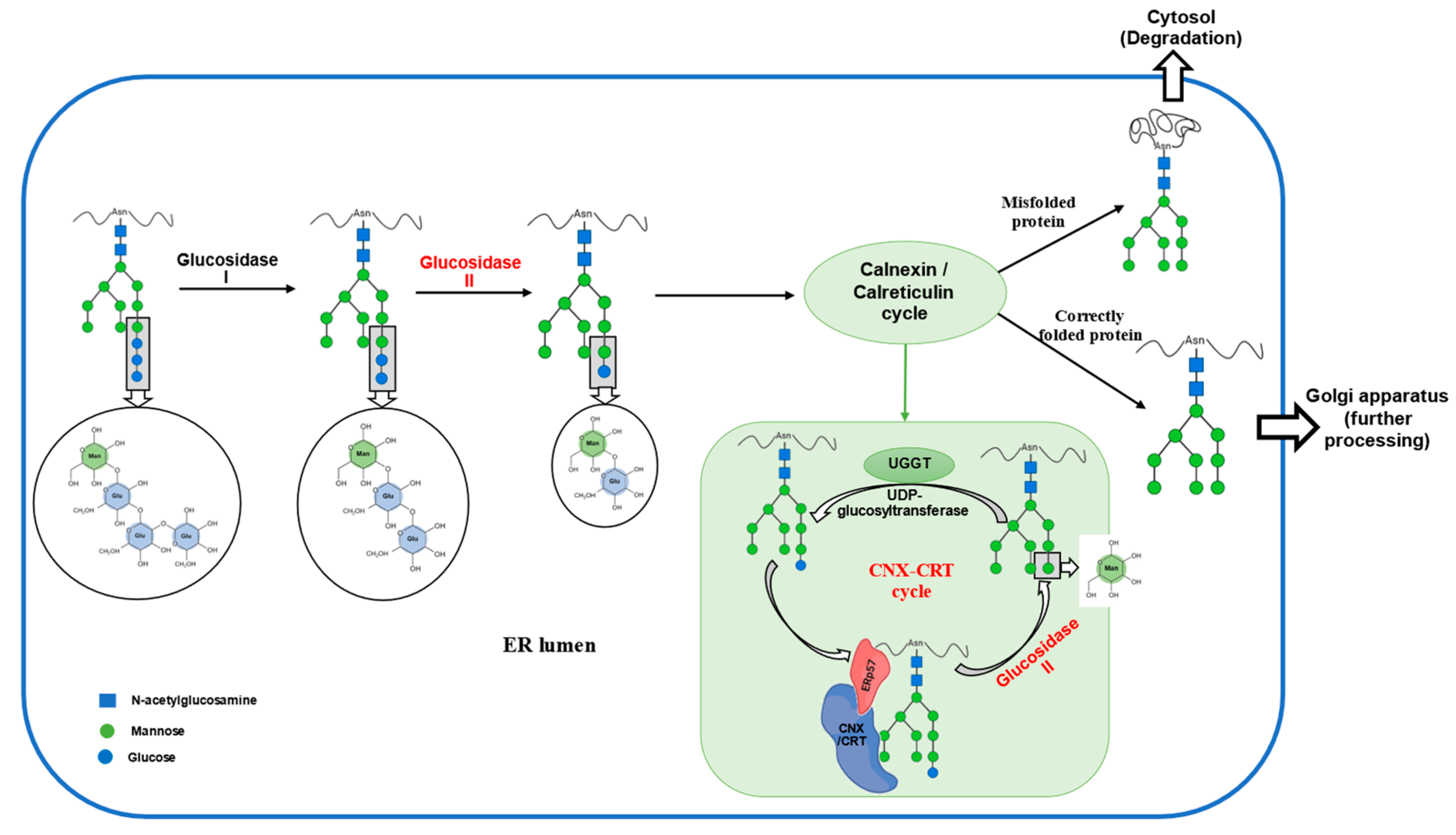

2.2. Function

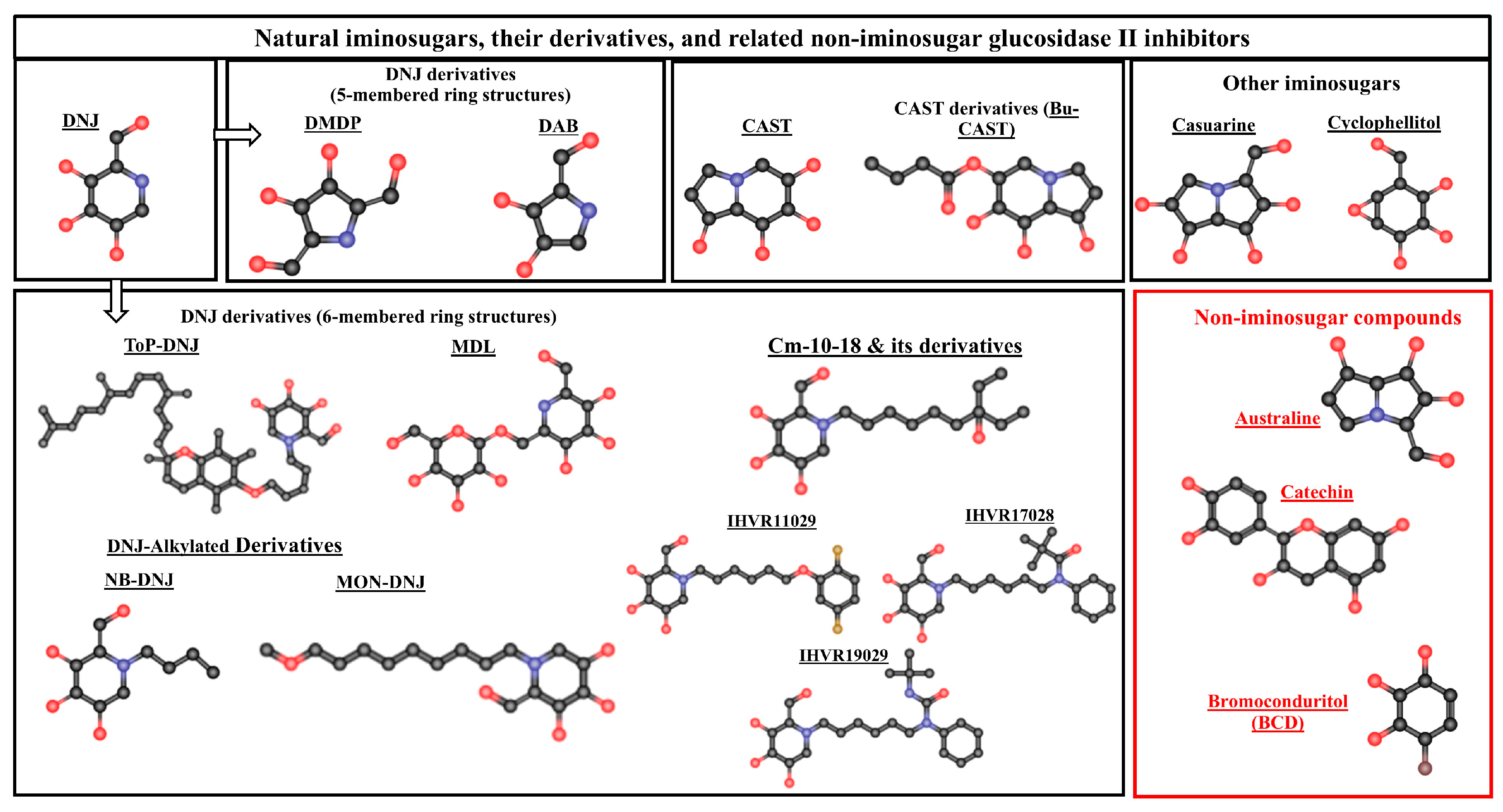

3. Glucosidase II Inhibitors

3.1. Natural Iminosugars and Their Derivatives

3.1.1. Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ)

3.1.2. DNJ Derivatives (6-Membered Ring Structure)

- ToP-DNJ4 (DNJ-tocopherol conjugate)

- 2.

- Alkylated derivatives of DNJ (NB-DNJ and MON-DNJ)

- 3.

- 2,6-dideoxy-2,6-imino-7-O-(beta-D-glucopyranosyl)-D-glycero-L-guloheptitol (MDL)

- 4.

- CM10-18 and its derivatives

3.1.3. DNJ Derivatives (5-Membered Ring Structure)

- 1.

- 2,5-dideoxy-2,5-imino-D-mannitol (DMDP)

- 2.

- 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-arabinitol (DAB)

3.1.4. Castanospermine (CAST)

3.1.5. Castanospermine Derivatives (Celgosivir, Bu-Cast)

3.1.6. Other Iminosugars

- 1.

- Casuarine (CSU)

- 2.

- Cyclophellitol-type compounds

3.2. Non-Iminosugar Compounds

3.2.1. Australine

3.2.2. Polyphenolic Catechins in Green Tea

3.2.3. Bromoconduritol (BCD)

4. Impact and Therapeutic Implications of Glucosidase II Inhibition

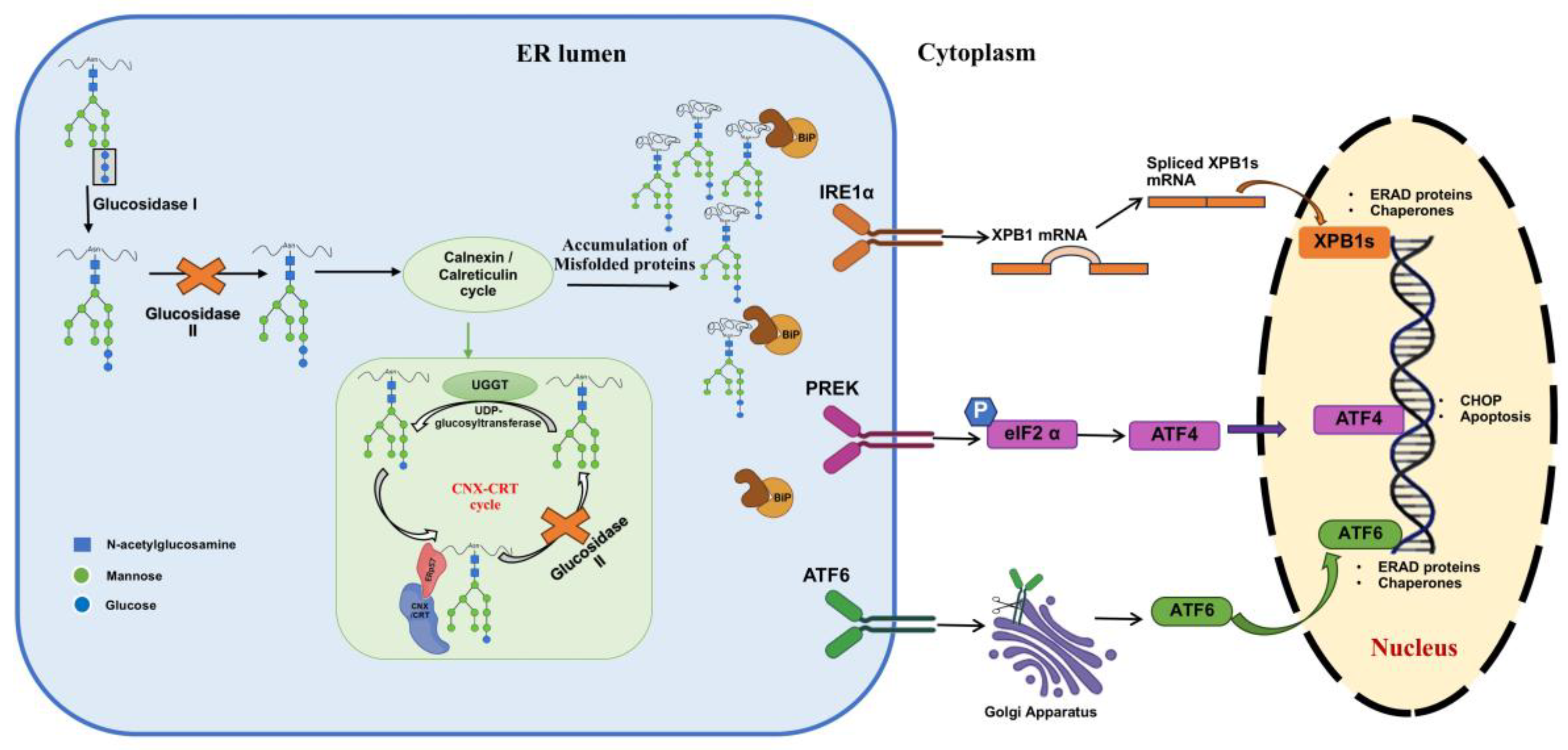

4.1. Impact on Protein Folding and ER Stress

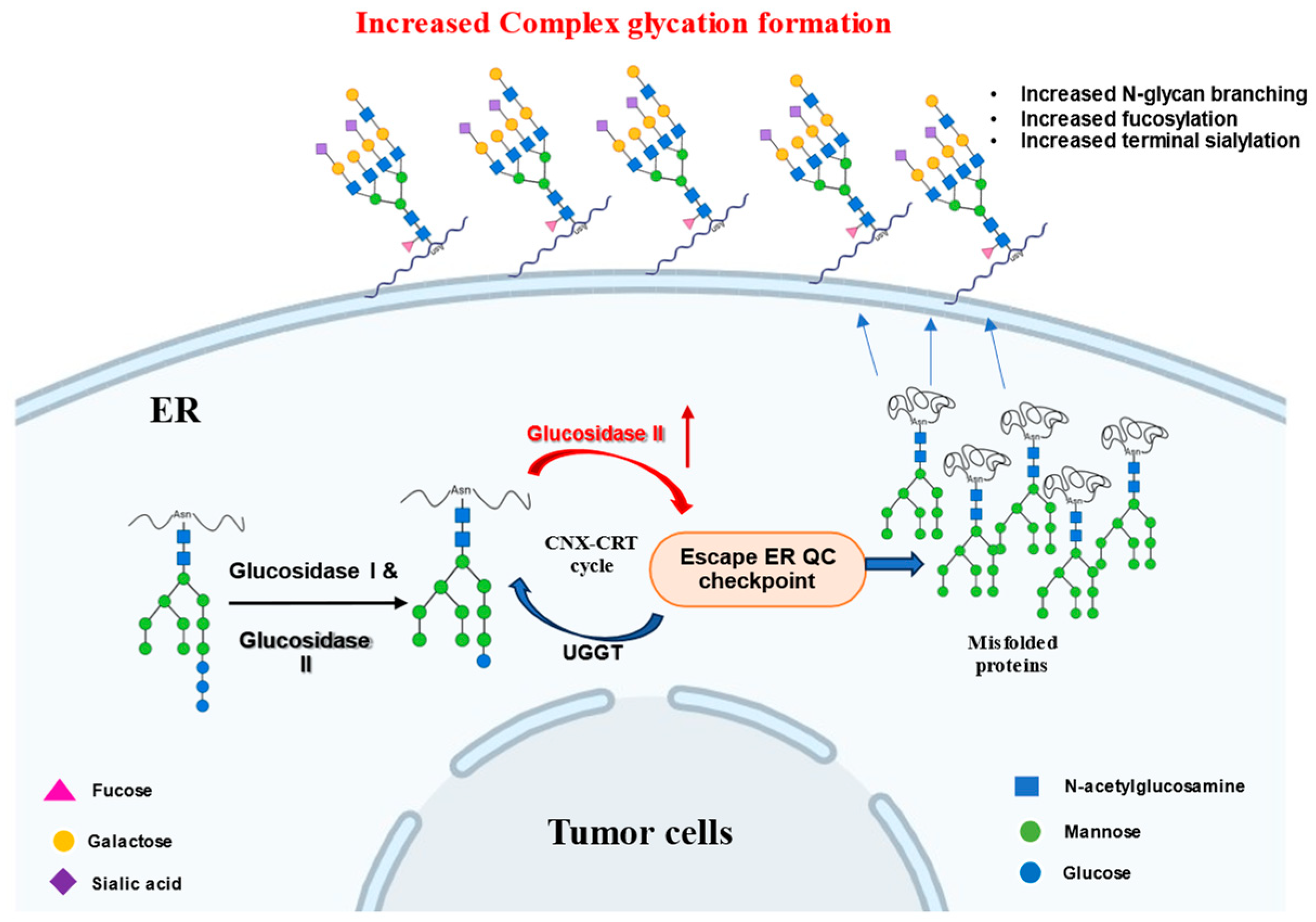

4.2. Role of Glucosidase II in Cancer

4.3. Glucosidase II Inhibition in Infectious Diseases

5. Challenges and Strategies for Selective Glucosidase II Inhibition

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGIs | α-Glucosidase inhibitors |

| ATF6 | Activating transcription factor 6 |

| BCD | Bromoconduritol |

| BiP | Binding immunoglobulin protein |

| Bu-Cast | 6-O-Butanoyl castanospermine |

| CAST | Castanospermine |

| CNX/CRT | Calnexin/Calreticulin chaperone system |

| CSU | Casuarine |

| DAB | 1,4-Dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-arabinitol |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| DENV | Dengue virus |

| DNJ | Deoxynojirimycin |

| DMDP | 2,5-Dideoxy-2,5-imino-D-mannitol |

| EBOV | Ebola virus |

| EC | Epicatechin |

| ECG | Epicatechin gallate |

| EGC | Epigallocatechin |

| EGCG | Epigallocatechin-3-gallate |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERAD | ER-associated degradation |

| GANAB | Gene encoding the GluII α-subunit |

| GIIα | Glucosidase II α-subunit |

| GIIβ | Glucosidase II β-subunit |

| GluI | Glucosidase I |

| GluII | Glucosidase II |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HDEL | His-Asp-Glu-Leu ER-retention motif |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HOXA1 | Homeobox A1 |

| IRE1 | Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 |

| KDEL | Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu ER-retention motif |

| MARV | Marburg virus |

| MDL | 2,6-dideoxy-2,6-imino-7-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-D-glycero-L-guloheptitol |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| MON-DNJ | N-(9′-methoxynonyl)-deoxynojirimycin |

| MRH domain | Mannose-6-phosphate receptor homology domain |

| mTOR | Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NB-DNJ NN-DNJ | N-butyl-1-deoxynojirimycin N-nonyl-deoxynojirimycin |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| pNPG | p-Nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside |

| PRKCSH PERK | Protein kinase C substrate 80K-H (Gene encoding the GluII β-subunit) Protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| rhGAA | Recombinant human acid α-glucosidase |

| TCID50 | Tissue culture infectious dose 50% |

| ToP-DNJ | DNJ-tocopherol conjugate |

| UGGT | UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

| VHFs | Viral hemorrhagic fevers |

| YFV | Yellow fever virus |

| ZIKV | Zika virus |

References

- Trombetta, E.S.; Simons, J.F.; Helenius, A. Endoplasmic Reticulum Glucosidase II Is Composed of a Catalytic Subunit, Conserved from Yeast to Mammals, and a Tightly Bound Noncatalytic HDEL-containing Subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 27509–27516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, C.W.; Ostergaard, H.L. Identification of the CD45-associated 116-kDa and 80-kDa Proteins as the α- and β-Subunits of α-Glucosidase II. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 13117–13125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentges, A.; Bause, E. Affinity Purification and Characterization of Glucosidase II from Pig Liver. Biol. Chem. 1997, 378, 1031–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, C.; Fernández, F.; Trombetta, E.S.; Parodi, A.J. Genetic Evidence for the Heterodimeric Structure of Glucosidase II. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 25899–25905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, C.W.; Dawicki, W.; Ostergaard, H.L. Alternative splicing of transcripts encoding the alpha- and beta-subunits of mouse glucosidase II in T lymphocytes. Glycobiology 1999, 9, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, T.; Toshimori, T.; Yan, G.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kato, K. Structural basis for two-step glucose trimming by glucosidase II involved in ER glycoprotein quality control. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brada, D.; Kerjaschki, D.; Roth, J. Cell type-specific post-Golgi apparatus localization of a “resident” endoplasmic reticulum glycoprotein, glucosidase II. J. Cell Biol. 1990, 110, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornfeld, R.; Kornfeld, S. Assembly of asparagine-linked oligosaccharides. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1985, 54, 631–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, M.D.; Robbins, P.W. Chapter 7 Synthesis and Processing of Asparagine-Linked Oligosaccharides of Glycoproteins; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981; pp. 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Lucocq, J.M.; Brada, D.; Roth, J. Immunolocalization of the oligosaccharide trimming enzyme glucosidase II. J. Cell Biol. 1986, 102, 2137–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellgaard, L.; Molinari, M.; Helenius, A. Setting the Standards: Quality Control in the Secretory Pathway. Science 1999, 286, 1882–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombetta, S.E.; Bosch, M.; Parodi, A.J. Glucosylation of glycoproteins by mammalian, plant, fungal, and trypanosomatid protozoa microsomal membranes. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 8108–8116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, M.C.; Ferrero-Garcia, M.A.; Parodi, A.J. Recognition of the oligosaccharide and protein moieties of glycoproteins by the UDP-Glc:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Pei, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhuang, X.; Qin, H. Glycoprotein α-Subunit of Glucosidase II (GIIα) is a novel prognostic biomarker correlated with unfavorable outcome of urothelial carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Tong, D.; Hoover, C.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Ni, L.; et al. MeCP2 regulated glycogenes contribute to proliferation and apoptosis of gastric cancer cells. Glycobiology 2017, 27, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussadia, Z.; Lamberti, J.; Mattei, F.; Pizzi, E.; Puglisi, R.; Zanetti, C.; Pasquini, L.; Fratini, F.; Fantozzi, L.; Felicetti, F.; et al. Acidic microenvironment plays a key role in human melanoma progression through a sustained exosome mediated transfer of clinically relevant metastatic molecules. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaodee, W.; Inboot, N.; Udomsom, S.; Kumsaiyai, W.; Cressey, R. Glucosidase II beta subunit (GluIIβ) plays a role in autophagy and apoptosis regulation in lung carcinoma cells in a p53-dependent manner. Cell. Oncol. 2017, 40, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenth, J.P.H.; Martina, J.A.; Te Morsche, R.H.M.; Jansen, J.B.M.J.; Bonifacino, J.S. Molecular characterization of hepatocystin, the protein that is defective in autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Gastroenterology 2004, 126, 1819–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayce, A.C.; Miller, J.L.; Zitzmann, N. Targeting a host process as an antiviral approach against dengue virus. Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Block, T.M.; Guo, J.-T. Antiviral therapies targeting host ER alpha-glucosidases: Current status and future directions. Antivir. Res. 2013, 99, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayce, A.C.; Alonzi, D.S.; Killingbeck, S.S.; Tyrrell, B.E.; Hill, M.L.; Caputo, A.T.; Iwaki, R.; Kinami, K.; Ide, D.; Kiappes, J.L.; et al. Iminosugars Inhibit Dengue Virus Production via Inhibition of ER Alpha-Glucosidases—Not Glycolipid Processing Enzymes. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, K.L.; Plummer, E.M.; Sayce, A.C.; Alonzi, D.S.; Tang, W.; Tyrrell, B.E.; Hill, M.L.; Caputo, A.T.; Killingbeck, S.S.; Beatty, P.R.; et al. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum glucosidases is required for in vitro and in vivo dengue antiviral activity by the iminosugar UV-4. Antivir. Res. 2016, 129, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaodee, W.; Udomsom, S.; Kunnaja, P.; Cressey, R. Knockout of glucosidase II beta subunit inhibits growth and metastatic potential of lung cancer cells by inhibiting receptor tyrosine kinase activities. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, L.; Willemsma, C.; Mohan, S.; Naim, H.Y.; Pinto, B.M.; Rose, D.R. Structural Basis for Substrate Selectivity in Human Maltase-Glucoamylase and Sucrase-Isomaltase N-terminal Domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 17763–17770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, L.; Quezada-Calvillo, R.; Sterchi, E.E.; Nichols, B.L.; Rose, D.R. Human Intestinal Maltase–Glucoamylase: Crystal Structure of the N-Terminal Catalytic Subunit and Basis of Inhibition and Substrate Specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 375, 782–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, L.; Qin, X.; Cao, X.; Wang, L.; Bai, F.; Bai, G.; Shen, Y. Structural insight into substrate specificity of human intestinal maltase-glucoamylase. Protein Cell 2011, 2, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, H.A.; Lo Leggio, L.; Willemoës, M.; Leonard, G.; Blum, P.; Larsen, S. Structure of the Sulfolobus solfataricus α-Glucosidase: Implications for Domain Conservation and Substrate Recognition in GH31. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 358, 1106–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagami, T.; Yamashita, K.; Okuyama, M.; Mori, H.; Yao, M.; Kimura, A. Molecular Basis for the Recognition of Long-chain Substrates by Plant α-Glucosidases. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 19296–19303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovering, A.L.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, Y.-W.; Withers, S.G.; Strynadka, N.C.J. Mechanistic and Structural Analysis of a Family 31 α-Glycosidase and Its Glycosyl-enzyme Intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 2105–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalz-Fuller, B.; Bieberich, E.; Bause, E. Cloning and Expression of Glucosidase I from Human Hippocampus. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 231, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, K.; Hirai, M.; Minoshima, S.; Kudoh, J.; Fukuyama, R.; Shimizu, N. Isolation of cDNAs encoding a substrate for protein kinase C: Nucleotide sequence and chromosomal mapping of the gene for a human 80K protein. Genomics 1989, 5, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozawa, M.; Muramatsu, T. Reticulocalbin, a novel endoplasmic reticulum resident Ca2+-binding protein with multiple EF-hand motifs and a carboxyl-terminal HDEL sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.W.; Lewis, M.J.; Pelham, H.R. pH-dependent binding of KDEL to its receptor in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 7465–7468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C.; Koch, G.L.E. Perturbation of cellular calcium induces secretion of luminal ER proteins. Cell 1989, 59, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönnichsen, B.; Füllekrug, J.; Van, P.N.; Diekmann, W.; Robinson, D.G.; Mieskes, G. Retention and retrieval: Both mechanisms cooperate to maintain calreticulin in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Sci. 1994, 107, 2705–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, K.; Griffiths, G.; Lamond, A.I. The endoplasmic reticulum calcium-binding protein of 55 kDa is a novel EF-hand protein retained in the endoplasmic reticulum by a carboxyl-terminal His-Asp-Glu-Leu motif. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 19142–19150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, C.W.; Ostergaard, H.L. Two distinct domains of the β-subunit of glucosidase II interact with the catalytic α-subunit. Glycobiology 2000, 10, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Masi, R.; Orlando, S. GANAB and N-Glycans Substrates Are Relevant in Human Physiology, Polycystic Pathology and Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, S.; Roebuck, Q.P.; Nakagome, I.; Hirono, S.; Kato, A.; Nash, R.; High, S. Characterizing the selectivity of ER α-glucosidase inhibitors. Glycobiology 2019, 29, 530–542, Correction in Glycobiology 2023, 33, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaler, M.; Ofman, T.P.; Kok, K.; Heming, J.J.; Moran, E.; Pickles, I.; Leijs, A.A.; van den Nieuwendijk, A.M.; van den Berg, R.J.; Ruijgrok, G.; et al. Epi-Cyclophellitol Cyclosulfate, a Mechanism-Based Endoplasmic Reticulum α-Glucosidase II Inhibitor, Blocks Replication of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Coronaviruses. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024, 10, 1594–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, A.T.; Alonzi, D.S.; Marti, L.; Reca, I.-B.; Kiappes, J.L.; Struwe, W.B.; Cross, A.; Basu, S.; Lowe, E.D.; Darlot, B.; et al. Structures of mammalian ER α-glucosidase II capture the binding modes of broad-spectrum iminosugar antivirals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4630–E4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, M.K.; Rose, D.R. Specificity of Processing α-Glucosidase I Is Guided by the Substrate Conformation: Crystallographic and in silico studies. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 13563–13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stigliano, I.D.; Caramelo, J.J.; Labriola, C.A.; Parodi, A.J.; D’Alessio, C. Glucosidase II β Subunit Modulates N-Glycan Trimming in Fission Yeasts and Mammals. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 3974–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajimoto, T.; Node, M. Inhibitors Against Glycosidases as Medicines. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorthy, N.S.H.N.; Ramos, M.J.; Fernandes, P.A. Studies on α-Glucosidase Inhibitors Development: Magic Molecules for the Treatment of Carbohydrate Mediated Diseases. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tundis, R.; Loizzo, M.R.; Menichini, F. Natural Products as α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitors and their Hypoglycaemic Potential in the Treatment of Diabetes: An Update. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Warren, T.K.; Zhao, X.; Gill, T.; Guo, F.; Wang, L.; Comunale, M.A.; Du, Y.; Alonzi, D.S.; Yu, W.; et al. Small molecule inhibitors of ER α-glucosidases are active against multiple hemorrhagic fever viruses. Antivir. Res. 2013, 98, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, K.; Plummer, E.; Alonzi, D.; Wolfe, G.; Sampath, A.; Nguyen, T.; Butters, T.; Enterlein, S.; Stavale, E.; Shresta, S.; et al. A Novel Iminosugar UV-12 with Activity against the Diverse Viruses Influenza and Dengue (Novel Iminosugar Antiviral for Influenza and Dengue). Viruses 2015, 7, 2404–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunier, B.; Kilker, R.D.; Tkacz, J.S.; Quaroni, A.; Herscovics, A. Inhibition of N-linked complex oligosaccharide formation by 1-deoxynojirimycin, an inhibitor of processing glucosidases. J. Biol. Chem. 1982, 257, 14155–14161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.A.; Friedlander, P.; Herscovics, A. Deoxynojirimycin inhibits the formation of Glc3Man9GlcNAc2-PP-dolichol in intestinal epithelial cells in culture. FEBS Lett. 1985, 183, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappus, H. Tolerance and safety of vitamin E: A toxicological position report. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1992, 13, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishina, K.; Unno, T.; Uno, Y.; Kubodera, T.; Kanouchi, T.; Mizusawa, H.; Yokota, T. Efficient In Vivo Delivery of siRNA to the Liver by Conjugation of α-Tocopherol. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balsitis, S.J.; Coloma, J.; Castro, G.; Alava, A.; Flores, D.; McKerrow, J.H.; Beatty, P.R.; Harris, E. Tropism of Dengue Virus in Mice and Humans Defined by Viral Nonstructural Protein 3-Specific Immunostaining. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 80, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoyuan Wang, P.J.Q. The location and function of vitamin E in membranes (Review). Mol. Membr. Biol. 2000, 17, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiappes, J.L.; Hill, M.L.; Alonzi, D.S.; Miller, J.L.; Iwaki, R.; Sayce, A.C.; Caputo, A.T.; Kato, A.; Zitzmann, N. ToP-DNJ, a Selective Inhibitor of Endoplasmic Reticulum α-Glucosidase II Exhibiting Antiflaviviral Activity. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalziel, M.; Crispin, M.; Scanlan, C.N.; Zitzmann, N.; Dwek, R.A. Emerging Principles for the Therapeutic Exploitation of Glycosylation. Science 2014, 343, 1235681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, S.T.; Buck, M.D.; Plummer, E.M.; Penmasta, R.A.; Batra, H.; Stavale, E.J.; Warfield, K.L.; Dwek, R.A.; Butters, T.D.; Alonzi, D.S.; et al. An iminosugar with potent inhibition of dengue virus infection in vivo. Antivir. Res. 2013, 98, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavale, E.J.; Vu, H.; Sampath, A.; Ramstedt, U.; Warfield, K.L. In Vivo Therapeutic Protection against Influenza A (H1N1) Oseltamivir-Sensitive and Resistant Viruses by the Iminosugar UV-4. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.S. Total synthesis of 2,6-dideoxy-2,6-imino-7-O-(.beta.-D-glucopyranosyl)-D-glycero-L-gulo-heptitol hydrochloride. A potent inhibitor of.alpha.-glucosidases. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 4717–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, G.P.; Pan, Y.T.; Tropea, J.E.; Mitchell, M.; Liu, P.; Elbein, A.D. Selective inhibition of glycoprotein-processing enzymes. Differential inhibition of glucosidases I and II in cell culture. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 17278–17283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, D.; Qu, X.; Guo, H.; Xu, X.; Mason, P.M.; Bourne, N.; Moriarty, R.; Gu, B.; et al. Novel Imino Sugar Derivatives Demonstrate Potent Antiviral Activity against Flaviviruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Schul, W.; Butters, T.D.; Yip, A.; Liu, B.; Goh, A.; Lakshminarayana, S.B.; Alonzi, D.; Reinkensmeier, G.; Pan, X.; et al. Combination of α-glucosidase inhibitor and ribavirin for the treatment of dengue virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Antivir. Res. 2011, 89, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbein, A.D.; Mitchell, M.; Sanford, B.A.; Fellows, L.E.; Evans, S.V. The pyrrolidine alkaloid, 2,5-dihydroxymethyl-3,4-dihydroxypyrrolidine, inhibits glycoprotein processing. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 12409–12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaney, W.M.; Simmonds, M.S.J.; Evans, S.V.; Fellows, L.E. The role of the secondary plant compound 2,5-dihydroxymethyl 3,4-dihydroxypyrrolidine as a feeding inhibitor for insects. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1984, 36, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrodnigg, T.M.; Diness, F.; Gruber, C.; Häusler, H.; Lundt, I.; Rupitz, K.; Steiner, A.J.; Stütz, A.E.; Tarling, C.A.; Withers, S.G.; et al. Probing the aglycon binding site of a β-glucosidase: A collection of C-1-modified 2,5-dideoxy-2,5-imino-d-mannitol derivatives and their structure–activity relationships as competitive inhibitors. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 3485–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermetter, A.; Scholze, H.; Stütz, A.E.; Withers, S.G.; Wrodnigg, T.M. Powerful probes for glycosidases. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 1339–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpas, A.; Fleet, G.W.; Dwek, R.A.; Petursson, S.; Namgoong, S.K.; Ramsden, N.G.; Jacob, G.S.; Rademacher, T.W. Aminosugar derivatives as potential anti-human immunodeficiency virus agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 9229–9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K.; Takahashi, M.; Nishida, M.; Miyauchi, M.; Kizu, H.; Kameda, Y.; Arisawa, M.; Watson, A.A.; Nash, R.J.; Fleet, G.W.J.; et al. Homonojirimycin analogues and their glucosides from Lobelia sessilifolia and Adenophora spp. (Campanulaceae). Carbohydr. Res. 1999, 323, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.; Ferrier, R. Monosaccharides. Their Chemistry and Their Roles in Natural Products; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries, M.J.; Olden, K. Asparagine-linked oligosaccharides and tumor metastasis. Pharmacol. Ther. 1989, 44, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenschutz, L.D.; Bell, E.A.; Jewess, P.J.; Leworthy, D.P.; Pryce, R.J.; Arnold, E.; Clardy, J. Castanospermine, A 1,6,7,8-tetrahydroxyoctahydroindolizine alkaloid, from seeds of Castanospermum australe. Phytochemistry 1981, 20, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.J.; Fellows, L.E.; Dring, J.V.; Stirton, C.H.; Carter, D.; Hegarty, M.P.; Bell, E.A. Castanospermine in Alexa species. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 1403–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.T.; Hori, H.; Saul, R.; Sanford, B.A.; Molyneux, R.J.; Elbein, A.D. Castanospermine inhibits the processing of the oligosaccharide portion of the influenza viral hemagglutinin. Biochemistry 1983, 22, 3975–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.H.; Sprague, E.A.; Kelley, J.L.; Kerbacher, J.J.; Schwartz, C.J.; Elbein, A.D. Castanospermine inhibits the function of the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 7679–7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakaki, R.F.; Hedo, J.A.; Collier, E.; Gorden, P. Effects of castanospermine and 1-deoxynojirimycin on insulin receptor biogenesis. Evidence for a role of glucose removal from core oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 11886–11892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwiger, A.; Niemann, H.; Käbisch, A.; Bauer, H.; Tamura, T. Appropriate glycosylation of the fms gene product is a prerequisite for its transforming potency. EMBO J. 1986, 5, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.D.; Kowalski, M.; Goh, W.C.; Kozarsky, K.; Krieger, M.; Rosen, C.; Rohrschneider, L.; Haseltine, W.A.; Sodroski, J. Inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus syncytium formation and virus replication by castanospermine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 8120–8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruters, R.A.; Neefjes, J.J.; Tersmette, M.; De Goede, R.E.Y.; Tulp, A.; Huisman, H.G.; Miedema, F.; Ploegh, H.L. Interference with HIV-induced syncytium formation and viral infectivity by inhibitors of trimming glucosidase. Nature 1987, 330, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montefiori, D.C.; Robinson, W.E.; Mitchell, W.M. Role of protein N-glycosylation in pathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 9248–9252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, R.J.; Roitman, J.N.; Dunnheim, G.; Szumilo, T.; Elbein, A.D. 6-Epicastanospermine, a novel indolizidine alkaloid that inhibits α-glucosidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1986, 251, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.S. Uptake and metabolism of BuCast: A glycoprotein processing inhibitor and a potential anti-HIV drug. Glycobiology 1996, 6, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.P.S.; Paradkar, P.N.; Watanabe, S.; Tan, K.H.; Sung, C.; Connolly, J.E.; Low, J.; Ooi, E.E.; Vasudevan, S.G. Celgosivir treatment misfolds dengue virus NS1 protein, induces cellular pro-survival genes and protects against lethal challenge mouse model. Antivir. Res. 2011, 92, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Imazeki, F.; Yokosuka, O. New antiviral therapies for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol. Int. 2010, 4, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonzi, D.S.; Scott, K.A.; Dwek, R.A.; Zitzmann, N. Iminosugar antivirals: The therapeutic sweet spot. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.J.; Thomas, P.I.; Waigh, R.D.; Fleet, G.W.J.; Wormald, M.R.; Lilley, P.M.D.Q.; Watkin, D.J. Casuarine: A very highly oxygenated pyrrolizidine alkaloid. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 7849–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, F.; Parmeggiani, C.; Faggi, E.; Bonaccini, C.; Gratteri, P.; Sim, L.; Gloster, T.M.; Roberts, S.; Davies, G.J.; Rose, D.R.; et al. Total Syntheses of Casuarine and Its 6-O-α-Glucoside: Complementary Inhibition towards Glycoside Hydrolases of the GH31 and GH37 Families. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2009, 15, 1627–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, J.K.; Yadav, S.; Vats, V. Hypoglycemic and antihyperglycemic effect of Brassica juncea diet and their effect on hepatic glycogen content and the key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002, 241, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsumi, S.; Umezawa, K.; Iinuma, H.; Naganawa, H.; Nakamura, H.; Iitaka, Y.; Takeuchi, T. Production, isolation and structure determination of a novel β-glucosidase inhibitor, cyclophellitol, from Phellinus sp. J. Antibiot. 1990, 43, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDevitt, R.E.; Fraser-Reid, B. A Divergent Route for a Total Synthesis of Cyclophellitol and Epicyclophellitol from a [2.2.2]Oxabicyclic Glycoside Prepared from D-Glucal. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 59, 3250–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, S.P.; Petracca, R.; Minnee, H.; Artola, M.; Aerts, J.M.F.G.; Codée, J.D.C.; Van Der Marel, G.A.; Overkleeft, H.S. A Divergent Synthesis of L-arabino- and D-xylo-Configured Cyclophellitol Epoxides and Aziridines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016, 4787–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, C.; McGregor, N.G.S.; Peterse, E.; Schröder, S.P.; Florea, B.I.; Jiang, J.; Reijngoud, J.; Ram, A.F.J.; Van Wezel, G.P.; Van Der Marel, G.A.; et al. Glycosylated cyclophellitol-derived activity-based probes and inhibitors for cellulases. RSC Chem. Biol. 2020, 1, 148–155, Correction in RSC Chem. Biol. 2021, 2, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravatt, B.F.; Wright, A.T.; Kozarich, J.W. Activity-Based Protein Profiling: From Enzyme Chemistry to Proteomic Chemistry. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 383–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, S.P.; Van De Sande, J.W.; Kallemeijn, W.W.; Kuo, C.-L.; Artola, M.; Van Rooden, E.J.; Jiang, J.; Beenakker, T.J.M.; Florea, B.I.; Offen, W.A.; et al. Towards broad spectrum activity-based glycosidase probes: Synthesis and evaluation of deoxygenated cyclophellitol aziridines. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 12528–12531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, L.I.; Overkleeft, H.S.; Kasteren, S.I.v. Current Developments in Activity-Based Protein Profiling. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014, 25, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofman, T.P.; Heming, J.J.A.; Nin-Hill, A.; Küllmer, F.; Moran, E.; Bennett, M.; Steneker, R.; Klein, A.M.; Ruijgrok, G.; Kok, K.; et al. Conformational and Electronic Variations in 1,2- and 1,5a-Cyclophellitols and their Impact on Retaining α-Glucosidase Inhibition. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202400723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artola, M.; Wu, L.; Ferraz, M.J.; Kuo, C.-L.; Raich, L.; Breen, I.Z.; Offen, W.A.; Codée, J.D.C.; Van Der Marel, G.A.; Rovira, C.; et al. 1,6-Cyclophellitol Cyclosulfates: A New Class of Irreversible Glycosidase Inhibitor. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 784–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneux, R.J.; Benson, M.; Wong, R.Y.; Tropea, J.E.; Elbein, A.D. Australine, a Novel Pyrrolizidine Alkaloid Glucosidase Inhibitor from Castanospermum australe. J. Nat. Prod. 2004, 6, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropea, J.E.; Molyneux, R.J.; Kaushal, G.P.; Pan, Y.T.; Mitchell, M.; Elbein, A.D. Australine, a pyrrolizidine alkaloid that inhibits amyloglucosidase and glycoprotein processing. Biochemistry 1989, 28, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, C.; Artacho, R.; Giménez, R. Beneficial Effects of Green Tea—A Review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2006, 25, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namal Senanayake, S.P.J. Green tea extract: Chemistry, antioxidant properties and food applications—A review. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botten, D.; Fugallo, G.; Fraternali, F.; Molteni, C. Structural Properties of Green Tea Catechins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 12860–12867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Y. Novel uses of catechins in foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, F.; Pala, N.; Carcelli, M.; Boateng, S.T.; D’Aquila, P.S.; Mariani, A.; Satta, S.; Chamcheu, J.C.; Sechi, M.; Sanna, V. α-Glucosidase inhibition by green, white and oolong teas: In vitro activity and computational studies. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2023, 38, 2236802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamberucci, A.; Konta, L.; Colucci, A.; Giunti, R.; Magyar, J.É.; Mandl, J.; Bánhegyi, G.; Benedetti, A.; Csala, M. Green tea flavonols inhibit glucosidase II. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006, 72, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.M.; Santa-Cecilia, A.; Calvo, P. Effect of bromoconduritol on glucosidase II from rat liver. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993, 215, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, Y.; Totani, K.; Matsuo, I.; Ito, Y. The action of bromoconduritol on ER glucosidase II. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 5357–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitby, K.; Pierson, T.C.; Geiss, B.; Lane, K.; Engle, M.; Zhou, Y.; Doms, R.W.; Diamond, M.S. Castanospermine, a Potent Inhibitor of Dengue Virus Infection In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 8698–8706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.L.; Sunkara, P.S.; Liu, P.S.; Kang, M.S.; Bowlin, T.L.; Tyms, A.S. 6–0-Butanoylcastanospermine (MDL 28,574) inhibits glycoprotein processing and the growth of HIVs. AIDS 1991, 5, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Rathore, A.P.S.; Sung, C.; Lu, F.; Khoo, Y.M.; Connolly, J.; Low, J.; Ooi, E.E.; Lee, H.S.; Vasudevan, S.G. Dose- and schedule-dependent protective efficacy of celgosivir in a lethal mouse model for dengue virus infection informs dosing regimen for a proof of concept clinical trial. Antivir. Res. 2012, 96, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.L.; Lachica, R.; Sayce, A.C.; Williams, J.P.; Bapat, M.; Dwek, R.; Beatty, P.R.; Harris, E.; Zitzmann, N. Liposome-Mediated Delivery of Iminosugars Enhances Efficacy against Dengue Virus In Vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 6379–6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrodnigg, T.M.; Withers, S.G.; Stütz, A.E. Novel, lipophilic derivatives of 2,5-dideoxy-2,5-imino-d-mannitol (DMDP) are powerful β-glucosidase inhibitors. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2001, 11, 1063–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haarr, M.B.; Lopéz, Ó.; Pejov, L.; Fernández-Bolaños, J.G.; Lindbäck, E.; Sydnes, M.O. 1,4-Dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-arabinitol (DAB) Analogues Possessing a Hydrazide Imide Moiety as Potent and Selective α-Mannosidase Inhibitors. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 18507–18514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, R.; Chai, X.; Wang, P.; Wu, K.; Duan, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, L. Inhibitory Effect and Mechanism of Dancong Tea from Different Harvesting Season on the α-Glucosidase Inhibition In Vivo and In Vitro. Foods 2024, 13, 4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstein, D.; Hollak, C.; Aerts, J.M.F.G.; Van Weely, S.; Maas, M.; Cox, T.M.; Lachmann, R.H.; Hrebicek, M.; Platt, F.M.; Butters, T.D.; et al. Sustained therapeutic effects of oral miglustat (Zavesca, N-butyldeoxynojirimycin, OGT 918) in type I Gaucher disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2004, 27, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, M.C.; Vecchio, D.; Prady, H.; Abel, L.; Wraith, J.E. Miglustat for treatment of Niemann-Pick C disease: A randomised controlled study. Lancet Neurol. 2007, 6, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischl, M.A.; Resniek, L.; Coombs, R.; Kremer, A.B.; Pottage, J.C.J.; Fass, R.J.; Fife, K.H.; Powderly, W.G.; Collier, A.C.; Aspinall, R.L.; et al. The Safety and Efficacy of Combination N-Butyl-Deoxynojirimycin (SC-48334) and Zidovudine in Patients with HIV-1 Infection and 200–500 CD4 Cells/mm. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1994, 7, 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Low, J.G.; Sung, C.; Wijaya, L.; Wei, Y.; Rathore, A.P.S.; Watanabe, S.; Tan, B.H.; Toh, L.; Chua, L.T.; Hou, Y.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of celgosivir in patients with dengue fever (CELADEN): A phase 1b, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durantel, D. Celgosivir, an alpha-glucosidase I inhibitor for the potential treatment of HCV infection. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2009, 10, 860–870. [Google Scholar]

- Crouchet, E.; Wrensch, F.; Schuster, C.; Zeisel, M.B.; Baumert, T.F. Host-targeting therapies for hepatitis C virus infection: Current developments and future applications. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2018, 11, 175628481875948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Seny, D.; Bianchi, E.; Baiwir, D.; Cobraiville, G.; Collin, C.; Deliège, M.; Kaiser, M.-J.; Mazzucchelli, G.; Hauzeur, J.-P.; Delvenne, P.; et al. Proteins involved in the endoplasmic reticulum stress are modulated in synovitis of osteoarthritis, chronic pyrophosphate arthropathy and rheumatoid arthritis, and correlate with the histological inflammatory score. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Rho, J.-H.; Roehrl, M.H.; Wang, J.Y. Dermatan Sulfate Is a Potential Regulator of IgH via Interactions With Pre-BCR, GTF2I, and BiP ER Complex in Pre-B Lymphoblasts. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 680212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhang, K.; Kaufman, R.J. The unfolded protein response—A stress signaling pathway of the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2004, 28, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Travers, K.J.; Patil, C.K.; Wodicka, L.; Lockhart, D.J.; Weissman, J.S.; Walter, P. Functional and Genomic Analyses Reveal an Essential Coordination between the Unfolded Protein Response and ER-Associated Degradation. Cell 2000, 101, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 862–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolotti, A.; Zhang, Y.; Hendershot, L.M.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 2, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyadomari, S.; Araki, E.; Mori, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis in pancreatic β-cells. Apoptosis 2002, 7, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schallus, T.; Jaeckh, C.; Fehér, K.; Palma, A.S.; Liu, Y.; Simpson, J.C.; Mackeen, M.; Stier, G.; Gibson, T.J.; Feizi, T.; et al. Malectin: A Novel Carbohydrate-binding Protein of the Endoplasmic Reticulum and a Candidate Player in the Early Steps of Protein N-Glycosylation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 8, 3404–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S.; Hendershot, L.M. ER stress and cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006, 5, 721–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar, J.É.; Gamberucci, A.; Konta, L.; Margittai, É.; Mandl, J.; Bánhegyi, G.; Benedetti, A.; Csala, M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress underlying the pro-apoptotic effect of epigallocatechin gallate in mouse hepatoma cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009, 41, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, G.; Ouadid-Ahidouch, H.; Sanchez-Fernandez, E.M.; Risquez-Cuadro, R.; Fernandez, J.M.G.; Ortiz-Mellet, C.; Ahidouch, A. New Castanospermine Glycoside Analogues Inhibit Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation and Induce Apoptosis without Affecting Normal Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, M.A.; Ballon, B.C.; Gerrard, J.M.; Greenberg, A.H.; Wright, J.A. The inhibition of platelet aggregation of metastatic H-ras-transformed 10T12 fibroblasts with castanospermine, an N-linked glycoprotein processing inhibitor. Cancer Lett. 1991, 60, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiura, T.; Karasuno, T.; Yoshida, H.; Nakao, H.; Ogawa, M.; Horikawa, Y.; Yoshimura, M.; Okajima, Y.; Kanakura, Y.; Kanayama, Y.; et al. Functional role of cation-independent mannose 6-phosphate/insulin-like growth factor II receptor in cell adhesion and proliferation of a human myeloma cell line OPM-2. Blood 1996, 88, 3546–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringeard, S.; Harb, J.; Gautier, F.; Menanteau, J.; Meflah, K. Altered glycosylation of α(s)β1 integrins from rat colon carcinoma cells decreases their interaction with fibronectin. J. Cell. Biochem. 1996, 62, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, G.-C.; Moon, S.U.; Kang, H.S.; Choi, H.-S.; Han, H.D.; Kim, K.-H. PRKCSH contributes to tumorigenesis by selective boosting of IRE1 signaling pathway. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaodee, W.; Xiyuan, G.; Han, M.T.T.; Tayapiwatana, C.; Chiampanichayakul, S.; Anuchapreeda, S.; Cressey, R. Transcriptomic analysis of glucosidase II beta subunit (GluIIß) knockout A549 cells reveals its roles in regulation of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) and anti-tumor immunity. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Bowden, T.A.; Wilson, I.A.; Crispin, M. Exploitation of glycosylation in enveloped virus pathobiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 1480–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, S.S.L.; Nguyen-Khuong, T.; Rudd, P.M.; Alonso, S. Dengue Virus Glycosylation: What Do We Know? Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonzi, D.S.; Kukushkin, N.V.; Allman, S.A.; Hakki, Z.; Williams, S.J.; Pierce, L.; Dwek, R.A.; Butters, T.D. Glycoprotein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum: Identification of released oligosaccharides reveals a second ER-associated degradation pathway for Golgi-retrieved proteins. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 2799–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simsek, E.; Mehta, A.; Zhou, T.; Dwek, R.A.; Block, T. Hepatitis B Virus Large and Middle Glycoproteins Are Degraded by a Proteasome Pathway in Glucosidase-Inhibited Cells but Not in Cells with Functional Glucosidase Enzyme. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 12914–12920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, B.; Matlin, K.; Bause, E.; Legler, G.; Peyrieras, N.; Ploegh, H. Inhibition of N-linked oligosaccharide trimming does not interfere with surface expression of certain integral membrane proteins. EMBO J. 1984, 3, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, M.; Vandenbroeck, K. The endoplasmic reticulum protein folding factory and its chaperones: New targets for drug discovery? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 162, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courageot, M.-P.; Frenkiel, M.-P.; Duarte Dos Santos, C.; Deubel, V.; DesprèS, P. α-Glucosidase Inhibitors Reduce Dengue Virus Production by Affecting the Initial Steps of Virion Morphogenesis in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, X.; Soloveva, V.; Warren, T.; Guo, F.; Wu, S.; Lu, H.; Guo, J.; Su, Q.; Shen, H.; et al. Enhancing the antiviral potency of ER α-glucosidase inhibitor IHVR-19029 against hemorrhagic fever viruses in vitro and in vivo. Antivir. Res. 2018, 150, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Gill, T.; Wang, L.; Du, Y.; Ye, H.; Qu, X.; Guo, J.-T.; Cuconati, A.; Zhao, K.; Block, T.M.; et al. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of N-Alkylated Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) Derivatives for the Treatment of Dengue Virus Infection. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 6061–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Pan, X.; Weidner, J.; Yu, W.; Alonzi, D.; Xu, X.; Butters, T.; Block, T.; Guo, J.-T.; Chang, J. Inhibitors of Endoplasmic Reticulum α-Glucosidases Potently Suppress Hepatitis C Virus Virion Assembly and Release. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Miller, J.L.; Harvey, D.J.; Gu, Y.; Rosenthal, P.B.; Zitzmann, N.; McCauley, J.W. Strain-specific antiviral activity of iminosugars against human influenza A viruses. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, K.; Barnard, D.; Enterlein, S.; Smee, D.; Khaliq, M.; Sampath, A.; Callahan, M.; Ramstedt, U.; Day, C. The Iminosugar UV-4 is a Broad Inhibitor of Influenza A and B Viruses ex Vivo and in Mice. Viruses 2016, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, G.W.J.; Karpas, A.; Dwek, R.A.; Fellows, L.E.; Tyms, A.S.; Petursson, S.; Namgoong, S.K.; Ramsden, N.G.; Smith, P.W.; Son, J.C.; et al. Inhibition of HIV replication by amino-sugar derivatives. FEBS Lett. 1988, 237, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, C.G.; Brennan, T.M.; Taylor, D.L.; McPherson, M.; Tyms, A.S. The prevention of cell adhesion and the cell-to-cell spread of HIV-1 in vitro by the α-glucosidase 1 inhibitor, 6-O-butanoyl castanospermine (MDL 28574). Antivir. Res. 1994, 25, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficicioglu, C. Review of miglustat for clinical management in Gaucher disease type 1. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakamata, W.; Ishikawa, R.; Ushijima, Y.; Tsukagoshi, T.; Tamura, S.; Hirano, T.; Nishio, T. Virtual ligand screening of α-glucosidase: Identification of a novel potent noncarbohydrate mimetic inhibitor. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liederer, B.M.; Borchardt, R.T. Enzymes involved in the bioconversion of ester-based prodrugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 95, 1177–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masyuk, T.; Masyuk, A.; Trussoni, C.; Howard, B.; Ding, J.; Huang, B.; Larusso, N. Autophagy-mediated reduction of miR-345 contributes to hepatic cystogenesis in polycystic liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2021, 3, 100345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Databases search | PubMed, Web of science, Google scholar |

| Period cover | 1990–2024 |

| Search Terms | Glucosidase, ER Glucosidase II, PRKCSH, Glycoprotein folding, Iminosugars, DNJ, Inhibitors, cancer, virus, Clinical trials, Treatment |

| Inclusion criteria | Journals focusing on GluII structure, function and inhibitions of the compounds |

| Exclusion criteria | Non-English papers, unrelated glycosidases, papers lacking primary data |

| Features | Glucosidase I | Glucosidase II |

|---|---|---|

| GH Family | GH Family 63 | GH Family 31 |

| Structure | Single-pass type II transmembrane protein | Heterodimer composed of a catalytic α-subunit and an accessory β-subunit |

| Biological substrate | Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 | Glc2Man9GlcNAc2, Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 |

| Cleavage | Selectively performs the first trimming step, removing first glucose from Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 | Removes glucoses from Glc2Man9GlcNAc2, Glc1Man9GlcNAc2, performing the second and third cleavage steps |

| Catalytic residues | 2 carboxylic residues (general acid & base) | 2 carboxylic residues (Nucleophile & General Acid/Base) |

| Key specificity | Specificity is guided by the unique conformation of the substrate | An insertion between +1 and +2 subsites establishes its activity and substrate specificity |

| Implication for inhibitors selective design | Targeting the unique pocket specific for the Glc3 conformation may help avoid off-target interactions. | Targeting the conserved ring of aromatic residues between the +1 and +2 subsites may yield increased potency and selectivity |

| Inhibitors | Source | In Vitro IC50 (µM) | In Vitro Biological Effects | In Vivo/Model Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) | Streptomyces and Bacillus strains; mulberry (Morus) leaves | 11.4 µM [21] | Blocks maturation of N-linked glycoproteins—potentially impairing asparagine (N-linked) glycosylation—and preferentially inhibits GluII over GluI. | No specified data in vivo |

| Castospermine | Seeds of Castanospermum australe (Moreton Bay chestnut) | 5–8 µM [60] | Inhibits overall glucose trimming (GluI and/or GluII) in ER-derived microsomes and strongly inhibits GII activity. | Improved survival in a dengue mouse model after intraperitoneal dosing at 10, 50, or 250 mg/kg/day for 10 days; the protective effect has not been conclusively attributed to GluII [107]. |

| Bu-CAST (Celgosivir) | Semisynthetic derivative of castanospermine | 1.1 µM [108] | Inhibits both GluI and GluII, disrupting protein folding by binding to the catalytic site of GluII. | In a lethal DENV mouse model, it is rapidly metabolized to castanospermine, and its protective efficacy correlates with inhibition of α-glucosidases I and II; the most effective regimen was 50 mg/kg twice daily for 5 days [109]. |

| ToP-DNJ4 (DNJ−tocopherol conjugate) | Derivatives of 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) | 9.0 µM [55] | Inhibits GluII activity and mitigates side effects through conjugation with an aromatic tocopherol moiety. | No in vivo data reported |

| NB-DNJ (N-butyl-1-deoxy nojirimycin) | Alkylated DNJ derivatives | 5.2 µM [21] | Inhibits glucosidase activity through dual-site binding; its unique exclusion loop confers higher selectivity for GluII. | Improved survival and reduced viral load in a lethal dengue mouse model; target enzyme not confirmed The most effective dose (Intraperitoneal injection) was 1000 mg/kg per days for 7 days [110]. |

| MON-DNJ (N-(9′-methoxynonyl)-DNJ | Alkylated DNJ derivatives | 1.8 µM [22] | Inhibits glucosidase activity with greater potency than other iminosugars such as DNJ and NB-DNJ. | Increased survival (90–100%) in a lethal DENV mouse model at 20 mg/kg TID [22]. |

| 2,6-dideoxy-2,6-imino-7-0-(~-D-glucopyranosyl)-D-glycero--L-guloheptitol (MDL) | Derivatives of 1-deoxynojirimycin (DNJ) | 1 µM [60] | Disrupts N-glycan processing, impairs glycoprotein maturation, and exhibits potent inhibitory activity against GluII. | No in vivo data reported |

| CM-10-18 | Semisynthetic DNJ derivative (OSL-95II modification) | 1.55 µM [62] | Significantly disrupts glucosidase activity in glucose trimming and exhibits dose-dependent selectivity for GluII. | Reduced peak viremia in DENV-infected mice with oral dosing; combination with ribavirin enhanced antiviral activity, with validated targeting of ER α-glucosidase II. Effective regimen: 75 mg/kg every 12 h for 3 days [62] |

| IHVR-11029 | Semisynthetic derivatives of CM-10-18 | 0.09 µM [47] | Significantly disrupts the protein-folding process through CM-10-18 derivatives, whose enhanced inhibitory effect supports their potential therapeutic application. | Significantly reduced mortality in lethal MARV and EBOV mouse models via inhibition of ER α-glucosidases I and II. Oral gavage: 32 mg/kg for MARV and 25 mg/kg for EBOV every 12 h for 10 days post-infection [47]. |

| IHVR-17028 | Semisynthetic derivatives of CM-10-18 | 0.24 µM [47] | Significantly disrupts the protein-folding process through CM-10-18 derivatives, whose enhanced inhibitory effect supports their potential therapeutic application. | Significantly reduced mortality in lethal MARV and EBOV mouse models via inhibition of ER α-glucosidases I and II. Oral gavage: 32 mg/kg for MARV and 25 mg/kg for EBOV every 12 h for 10 days post-infection [47]. |

| IHVR-19029 | Semisynthetic derivatives of CM-10-18 | 0.48 µM [47] | Significantly disrupts the protein-folding process through CM-10-18 derivatives, whose enhanced inhibitory effect supports their potential therapeutic application. | Significantly reduced mortality in lethal MARV and EBOV mouse models via inhibition of ER α-glucosidases I and II. Oral gavage: 32 mg/kg for MARV and 25 mg/kg for EBOV every 12 h for 10 days post-infection [47]. |

| 2,5-dideoxy-2,5-imino-D-mannitol (DMDP) | Leaves of Derris elliptica and seeds of Lonchocarpus sericeus | No IC50 data reported. [111] | More strongly inhibits the early glucose-trimming stage, showing greater effect on GluI than on GluII. | No in vivo data reported |

| 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-arabinitol (DAB) | Angylocalyx spp. (reported as “A. botiquenus”) | No IC50 data reported. [112] | Inhibits glucosidase enzymes, including GluII, and disrupts protein folding. | No in vivo data reported |

| Casuarine (CSU) | Casuarina equisetifolia (Australian pine) and leaves of Java plum Syzygium cumini [syn. Eugenia jambolana] | No IC50 data reported. [86] | Exhibits stronger inhibition on GluII than on GluI and disrupts the glucose-trimming process. | No in vivo data reported |

| 1,2-cyclophellitol analogues | Semisynthetic cyclophellitol analogue; parent compound isolated from Phellinus sp. | 11.3 µM [95] | Shows reduced inhibitory activity compared with the 1,5a analogue. | No in vivo data reported |

| 1,5a-cyclophellitol analogues | Semisynthetic cyclophellitol analogue; parent compound isolated from Phellinus sp. | 0.028 µM [95] | Exhibits better inhibitory properties than the 1,2 analogue and blocks protein folding. | No in vivo data reported |

| 1,6-epi-cyclophellitol cyclosulfate | Semisynthetic cyclophellitol analogue; parent compound isolated from Phellinus sp. | 0.03 µM [40] | Inhibits GluII activity and reduces viral replication. | No in vivo data reported |

| Australine | Seeds of Castanospermum australe | 5.8 µM [98] | Exhibits stronger inhibitory activity on GluI than on GluII and prevents the N-linked glycosylation process. | No in vivo data reported |

| Polyphenolic catechins -EGCG | Leaves of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) | 50.92 µM/47.72 µM [104] | Inhibits GluII activity, thereby affecting glycoprotein maturation and quality control in the ER. | Inhibited postprandial blood-glucose rise in mice via intestinal α-glucosidase inhibition, not ER glucosidase. Oral dose: catechin mixture (main monomers) at 50 mg/kg body weight [113]. |

| Polyphenolic catechins -EGC | Leaves of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) | 117.7/110.5 µM [104] | Inhibits GluII activity, thereby affecting glycoprotein maturation and quality control in the ER. | Inhibited postprandial blood-glucose rise in mice via intestinal α-glucosidase inhibition, not ER glucosidase. Oral dose: catechin mixture (main monomers) at 50 mg/kg body weight [113]. |

| Polyphenolic catechins -ECG | Leaves of tea plant (Camellia sinensis) | 15.14/19.06 µM [104] | Inhibits GluII activity, thereby affecting glycoprotein maturation and quality control in the ER. | Inhibited postprandial blood-glucose rise in mice via intestinal α-glucosidase inhibition, not ER glucosidase. Oral dose: catechin mixture (main monomers) at 50 mg/kg body weight [113]. |

| Drug | Disease | Phase | Key Results | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miglustat | Gaucher disease type 1 | Long-term extension study (First Trial) | Reduced spleen volume (30%) and liver volume (18%) over 12 months. Improvement in hemoglobin and platelet count | Diarrhea, weight lost and peripheral neuropathy | [114] |

| Miglustat | Niemann-Pick Disease Type C (NP-C) | Randomised controlled study (12-month duration) | Beneficial effect on neurological progression over 12 months. | Small number of participants and adverse effect such as diarrhea. | [115] |

| Miglustat | HIV infection | Phase II (Double-blind, randomized, controlled study) | Suppression of HIV p2 Antigenemia was lower in the combination therapy with zidovudine and increase in CD4 cells was noted. | Gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, abdnominal pain), weigh lost. | [116] |

| Celgosivir | Dengue virus | Phase 1b (Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept trial. | No significant efficiency resulted for the primary end points but it was generally safe and well tolerated | Lack of efficiency and side-effects (diarrhea) | [117] |

| Celgosivir | HCV infection | Phase II trial | Synergistic effect in combination therapy | Stopped in the Migenix financial report for 2010 | [118,119] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oo, T.Z.M.; Wuttiin, Y.; Choocheep, K.; Kumsaiyai, W.; Bunpo, P.; Cressey, R. Exploring Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Glucosidase II: Advances, Challenges, and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer and Viral Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411867

Oo TZM, Wuttiin Y, Choocheep K, Kumsaiyai W, Bunpo P, Cressey R. Exploring Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Glucosidase II: Advances, Challenges, and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer and Viral Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411867

Chicago/Turabian StyleOo, Tay Zar Myo, Yupanun Wuttiin, Kanyamas Choocheep, Warunee Kumsaiyai, Piyawan Bunpo, and Ratchada Cressey. 2025. "Exploring Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Glucosidase II: Advances, Challenges, and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer and Viral Infection" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411867

APA StyleOo, T. Z. M., Wuttiin, Y., Choocheep, K., Kumsaiyai, W., Bunpo, P., & Cressey, R. (2025). Exploring Small-Molecule Inhibitors of Glucosidase II: Advances, Challenges, and Therapeutic Potential in Cancer and Viral Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11867. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411867