Drug Repurposing in Glioblastoma Using a Machine Learning-Based Hybrid Feature Selection Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

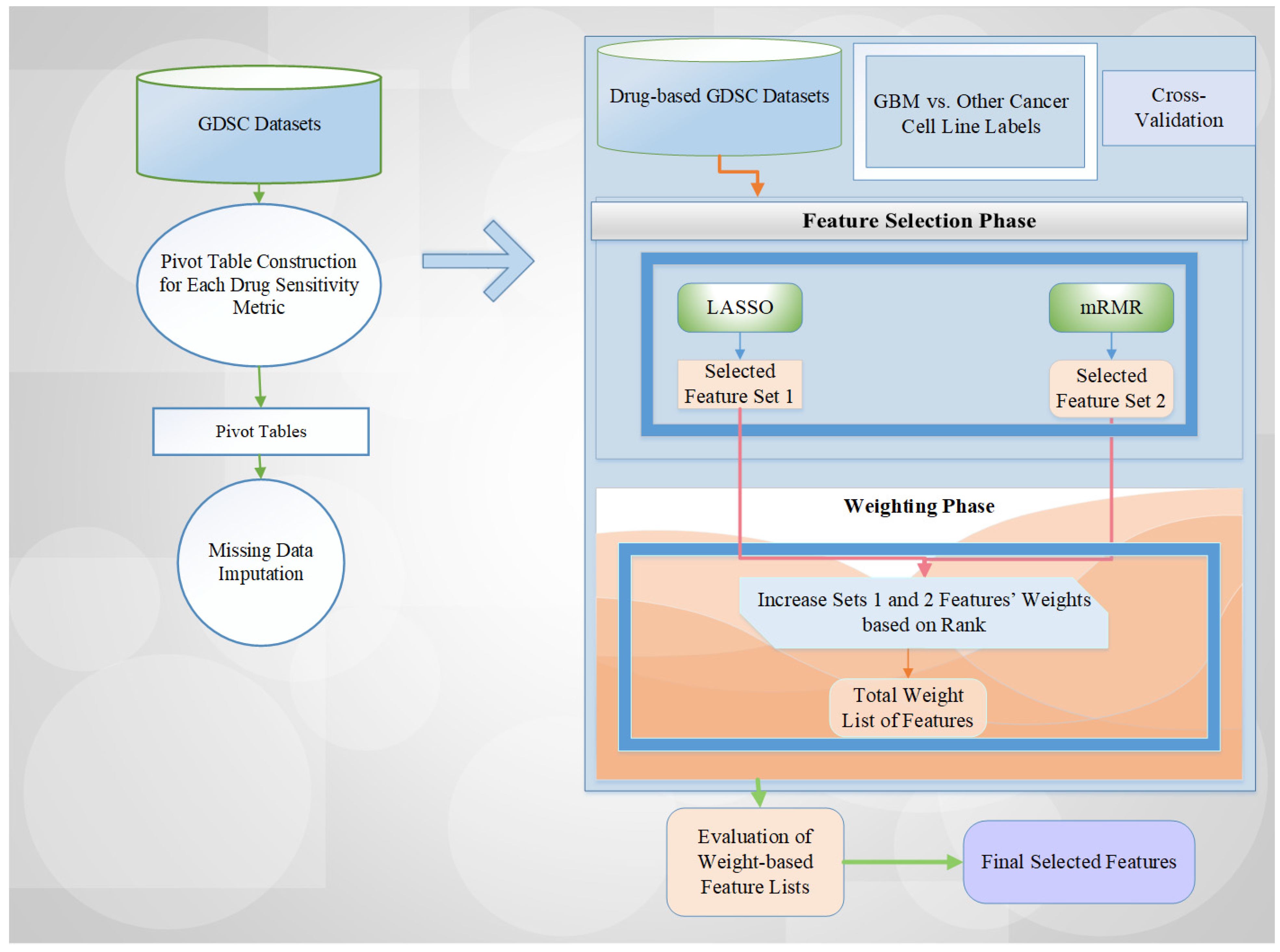

- To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that employs a combined feature selection and weighting methodology to select drug compounds by discriminating GBM cell lines versus other cell lines by employing four drug sensitivity metrics separately, namely, LN_IC50 (Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration), AUC (Area Under the Curve), RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error), and Z_SCORE (Standard score).

- We assessed the effects of varying feature selection and weighting task weights on the classification model’s performance.

- To improve the impact of reliability and fairness of performance estimates under imbalanced class distribution in the GDSC1 and GDSC2 datasets, we employed stratified five-fold cross-validation, maintaining the original class proportions within each data fold.

- We conducted comprehensive experiments for the evaluation of feature selection and weighting across the ensemble machine learning classification model, namely, Random Forest (RF), to identify the optimal drug compound set among all combination sets and the minimal feature subset necessary for precise classification.

- Feature weighting is a crucial stage in determining which features will be used at the final decision point among the various feature names that emerge during the cross-validation process, and in addressing this problem.

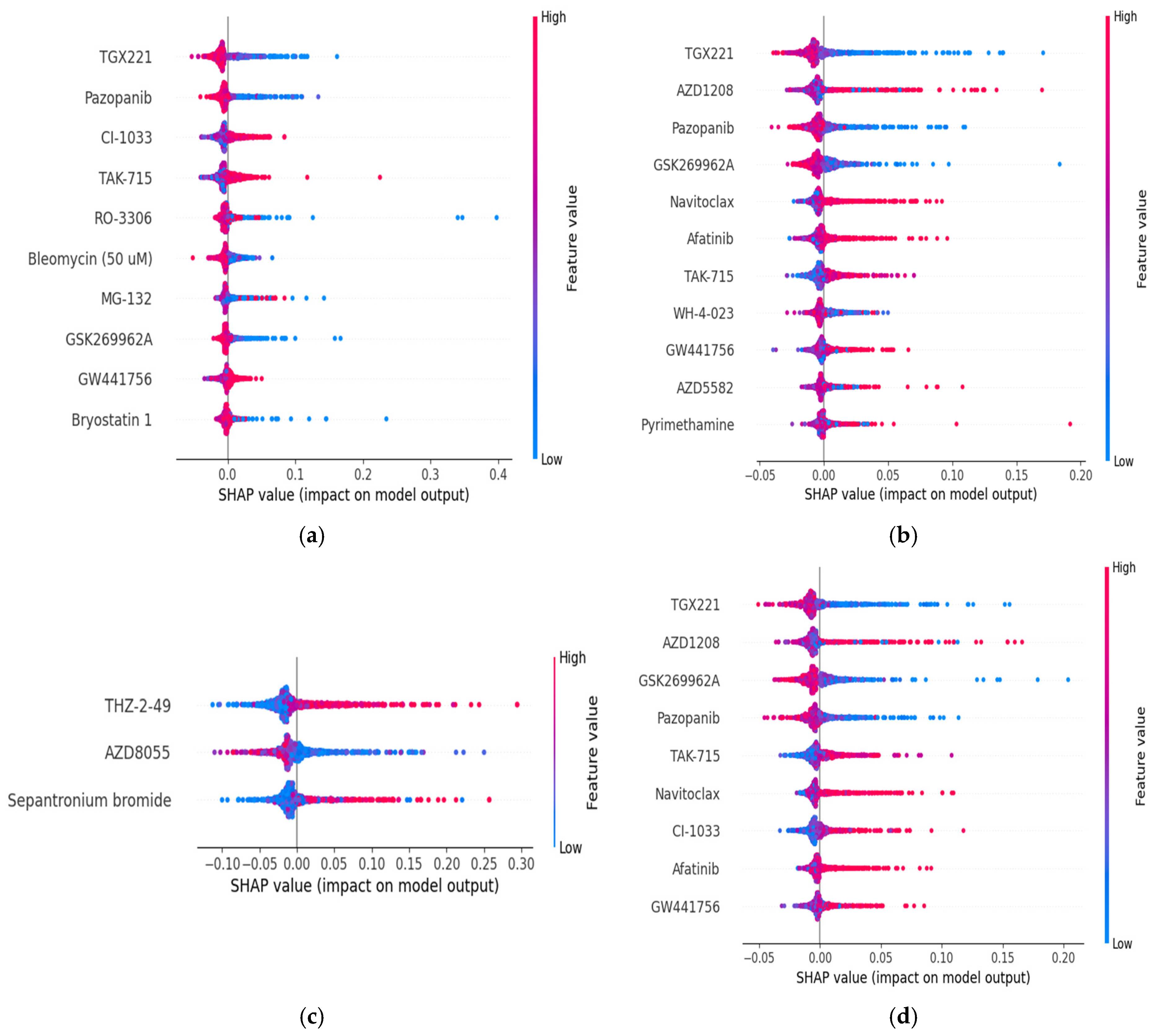

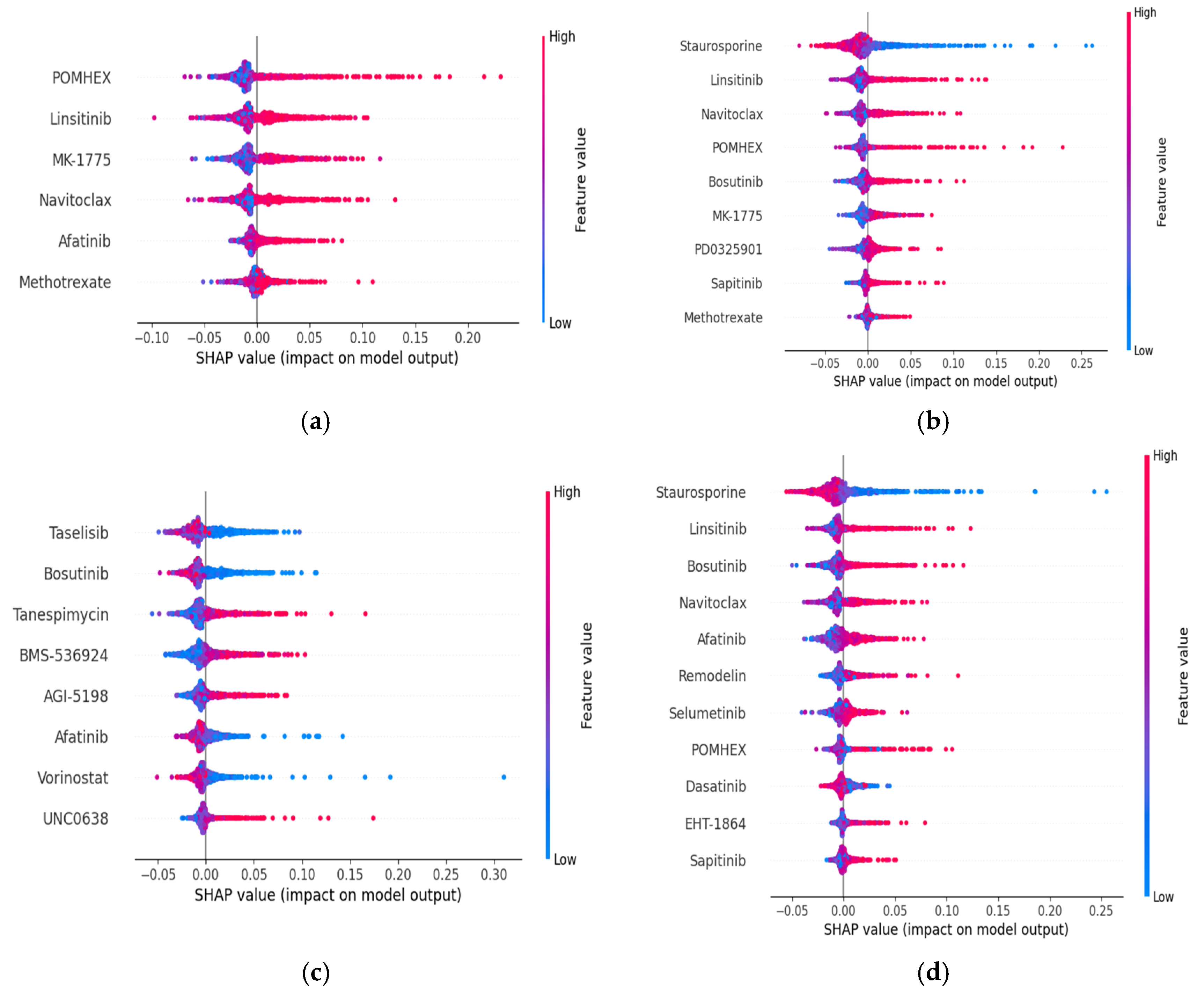

- To observe the impact of the selected feature set of GBM cell lines on model prediction performance for each dataset and drug sensitivity metric, we plotted SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations)-based plots.

- We leveraged GDSC datasets, employing feature selection techniques to identify signals that differentiate GBM cell lines vs. other cell lines. This is a novel finding, as drug compound-based GBM cell line profiles with machine learning (ML)-based methodology have not been previously characterized.

- We discussed the potential interpretation of the identified critical features in association with GBM.

2. Results

2.1. Experimental Process

2.2. Performance Metrics

2.3. Computational Results

2.3.1. The Effects of Feature Selection and Weighting Method on Classification Model Performance for the Categorization of GBM Cell Lines Versus Other Cell Lines on GDSC Datasets

2.3.2. GDSC1 Dataset Results

| LASSO = 1 and mRMR = 2 | LASSO = 2 and mRMR = 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | # of Features | RF | k | # of Features | RF |

| 1 | 132 | 96.592 | 1 | 132 | 96.592 |

| 2 | 91 | 96.592 | 2 | 120 | 96.592 |

| 3 | 68 | 96.592 | 3 | 78 | 96.592 |

| 4 | 52 | 96.592 | 4 | 74 | 96.592 |

| 5 | 36 | 96.592 | 5 | 63 | 96.592 |

| 6 | 10 | 96.592 | 6 | 60 | 96.592 |

| 7 | 6 | 96.591 | 7 | 45 | 96.592 |

| 8 | 3 | 96.488 | 8 | 44 | 96.592 |

| 9 | 3 | 96.488 | 9 | 31 | 96.592 |

| 10 | 3 | 96.488 | 10 | 30 | 96.592 |

| 11 | 3 | 96.488 | 11 | 5 | 96.487 |

| 12 | 2 | 96.488 | 12 | 3 | 96.488 |

| 13 | 2 | 96.488 | 13 | 3 | 96.488 |

| 14 | 1 | 94.319 | 14 | 2 | 96.488 |

| LASSO = 1 and mRMR = 2 | LASSO = 2 and mRMR = 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | # of Features | RF | k | # of Features | RF |

| 1 | 155 | 96.592 | 1 | 155 | 96.592 |

| 2 | 94 | 96.592 | 2 | 151 | 96.592 |

| 3 | 71 | 96.592 | 3 | 90 | 96.592 |

| 4 | 54 | 96.592 | 4 | 90 | 96.592 |

| 5 | 38 | 96.592 | 5 | 71 | 96.592 |

| 6 | 15 | 96.798 | 6 | 68 | 96.592 |

| 7 | 14 | 96.695 | 7 | 51 | 96.592 |

| 8 | 10 | 96.488 | 8 | 49 | 96.592 |

| 9 | 7 | 96.591 | 9 | 36 | 96.695 |

| 10 | 6 | 96.591 | 10 | 35 | 96.592 |

| 11 | 5 | 96.488 | 11 | 11 | 96.798 |

| 12 | 3 | 96.385 | 12 | 5 | 96.385 |

| 13 | 3 | 96.385 | 13 | 4 | 96.488 |

| 14 | 1 | 93.594 | 14 | 2 | 96.180 |

| LASSO = 1 and mRMR = 2 | LASSO = 2 and mRMR = 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | # of Features | RF | k | # of Features | RF |

| 1 | 141 | 96.592 | 1 | 141 | 96.592 |

| 2 | 95 | 96.592 | 2 | 136 | 96.592 |

| 3 | 68 | 96.592 | 3 | 90 | 96.592 |

| 4 | 47 | 96.592 | 4 | 87 | 96.592 |

| 5 | 32 | 96.592 | 5 | 65 | 96.592 |

| 6 | 16 | 96.695 | 6 | 64 | 96.592 |

| 7 | 14 | 96.695 | 7 | 46 | 96.592 |

| 8 | 11 | 96.592 | 8 | 46 | 96.592 |

| 9 | 11 | 96.592 | 9 | 32 | 96.592 |

| 10 | 5 | 96.385 | 10 | 30 | 96.592 |

| 11 | 4 | 96.488 | 11 | 14 | 96.592 |

| 12 | 3 | 96.798 | 12 | 10 | 96.695 |

| 13 | 3 | 96.798 | 13 | 4 | 96.488 |

| 14 | 1 | 93.906 | 14 | 3 | 96.798 |

| LASSO = 1 and mRMR = 2 | LASSO = 2 and mRMR = 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | # of Features | RF | k | # of Features | RF |

| 1 | 178 | 96.592 | 1 | 178 | 96.592 |

| 2 | 120 | 96.592 | 2 | 175 | 96.592 |

| 3 | 93 | 96.592 | 3 | 117 | 96.592 |

| 4 | 61 | 96.592 | 4 | 114 | 96.592 |

| 5 | 39 | 96.695 | 5 | 90 | 96.592 |

| 6 | 14 | 96.695 | 6 | 88 | 96.592 |

| 7 | 13 | 96.592 | 7 | 58 | 96.592 |

| 8 | 11 | 96.488 | 8 | 56 | 96.592 |

| 9 | 9 | 96.799 | 9 | 36 | 96.695 |

| 10 | 4 | 96.696 | 10 | 35 | 96.695 |

| 11 | 4 | 96.696 | 11 | 10 | 96.798 |

| 12 | 3 | 96.179 | 12 | 8 | 96.695 |

| 13 | 3 | 96.179 | 13 | 4 | 96.696 |

| 14 | 1 | 94.111 | 14 | 3 | 96.179 |

2.3.3. GDSC2 Dataset Results

| LASSO = 1 and mRMR = 2 | LASSO = 2 and mRMR = 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | # of Features | RF | k | # of Features | RF |

| 1 | 76 | 96.470 | 1 | 76 | 96.470 |

| 2 | 51 | 96.470 | 2 | 70 | 96.470 |

| 3 | 32 | 96.470 | 3 | 42 | 96.470 |

| 4 | 23 | 96.470 | 4 | 40 | 96.470 |

| 5 | 15 | 96.262 | 5 | 26 | 96.470 |

| 6 | 7 | 96.365 | 6 | 25 | 96.470 |

| 7 | 6 | 96.573 | 7 | 17 | 96.470 |

| 8 | 5 | 96.159 | 8 | 14 | 96.470 |

| 9 | 5 | 96.159 | 9 | 9 | 96.366 |

| 10 | 5 | 96.159 | 10 | 9 | 96.366 |

| 11 | 4 | 96.055 | 11 | 5 | 96.159 |

| 12 | 4 | 96.055 | 12 | 4 | 96.055 |

| 13 | 4 | 96.055 | 13 | 4 | 96.055 |

| 14 | 2 | 96.262 | 14 | 4 | 96.055 |

| LASSO = 1 and mRMR = 2 | LASSO = 2 and mRMR = 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | # of Features | RF | k | # of Features | RF |

| 1 | 80 | 96.470 | 1 | 80 | 96.470 |

| 2 | 49 | 96.573 | 2 | 79 | 96.470 |

| 3 | 37 | 96.470 | 3 | 48 | 96.470 |

| 4 | 28 | 96.574 | 4 | 46 | 96.573 |

| 5 | 22 | 96.470 | 5 | 35 | 96.574 |

| 6 | 12 | 96.677 | 6 | 33 | 96.574 |

| 7 | 12 | 96.677 | 7 | 26 | 96.574 |

| 8 | 10 | 96.365 | 8 | 24 | 96.574 |

| 9 | 8 | 96.573 | 9 | 20 | 96.574 |

| 10 | 7 | 96.573 | 10 | 20 | 96.574 |

| 11 | 6 | 96.469 | 11 | 9 | 96.677 |

| 12 | 4 | 96.468 | 12 | 6 | 96.470 |

| 13 | 4 | 96.468 | 13 | 5 | 96.262 |

| 14 | 4 | 96.468 | 14 | 3 | 96.366 |

| LASSO = 1 and mRMR = 2 | LASSO = 2 and mRMR = 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | # of Features | RF | k | # of Features | RF |

| 1 | 92 | 96.470 | 1 | 92 | 96.470 |

| 2 | 61 | 96.470 | 2 | 87 | 96.470 |

| 3 | 37 | 96.470 | 3 | 56 | 96.470 |

| 4 | 25 | 96.470 | 4 | 53 | 96.470 |

| 5 | 20 | 96.470 | 5 | 34 | 96.470 |

| 6 | 15 | 96.470 | 6 | 31 | 96.470 |

| 7 | 14 | 96.470 | 7 | 22 | 96.470 |

| 8 | 9 | 96.365 | 8 | 20 | 96.470 |

| 9 | 9 | 96.365 | 9 | 17 | 96.470 |

| 10 | 4 | 96.366 | 10 | 16 | 96.470 |

| 11 | 3 | 96.366 | 11 | 13 | 96.470 |

| 12 | 3 | 96.366 | 12 | 8 | 96.470 |

| 13 | 3 | 96.366 | 13 | 3 | 96.366 |

| 14 | 3 | 96.366 | |||

| LASSO = 1 and mRMR = 2 | LASSO = 2 and mRMR = 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | # of Features | RF | k | # of Features | RF |

| 1 | 117 | 96.470 | 1 | 117 | 96.470 |

| 2 | 76 | 96.470 | 2 | 116 | 96.470 |

| 3 | 48 | 96.470 | 3 | 75 | 96.470 |

| 4 | 36 | 96.470 | 4 | 73 | 96.470 |

| 5 | 22 | 96.470 | 5 | 45 | 96.470 |

| 6 | 11 | 96.781 | 6 | 43 | 96.573 |

| 7 | 10 | 96.677 | 7 | 32 | 96.470 |

| 8 | 8 | 96.470 | 8 | 30 | 96.470 |

| 9 | 7 | 96.573 | 9 | 18 | 96.470 |

| 10 | 7 | 96.573 | 10 | 18 | 96.470 |

| 11 | 7 | 96.573 | 11 | 8 | 96.573 |

| 12 | 5 | 96.366 | 12 | 6 | 96.573 |

| 13 | 4 | 96.677 | 13 | 5 | 96.573 |

| 14 | 3 | 96.573 | 14 | 3 | 96.470 |

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

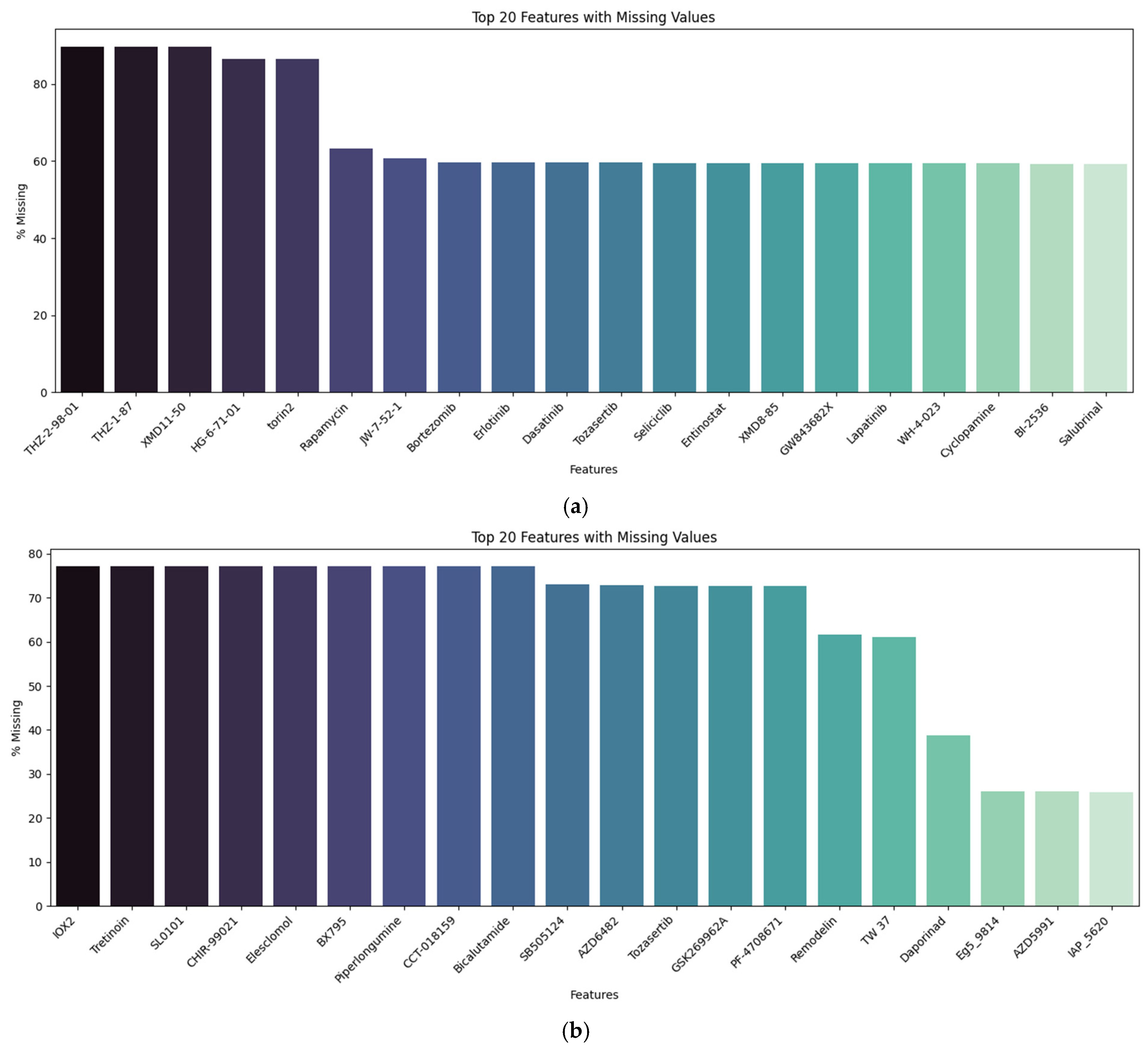

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Methodology

Proposed Scheme

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACC | Accuracy |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CRT | Chemoirradiation |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FS | Feature Selection |

| FW | Feature Weighting |

| GBM | Glioblastoma Multiforme |

| GDSC | Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| LN_IC50 | Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MRMR | Minimum Redundancy–Maximum Relevance |

| NCI | National Cancer Institute |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| RT | Radiation Therapy |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| Z_SCORE | Standard score |

References

- Carrano, A.; Zarco, N.; Phillipps, J.; Lara-Velazquez, M.; Suarez-Meade, P.; Norton, E.S.; Chaichana, K.L.; Quiñones-Hinojosa, A.; Asmann, Y.W.; Guerrero-Cázares, H. Human cerebrospinal fluid modulates pathways promoting glioblastoma malignancy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 624145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.P.; Fisher, J.L.; Nichols, E.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; Abraha, H.N.; Agius, D.; Alahdab, F.; Alam, T. Global, regional, and national burden of brain and other CNS cancer, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Gittleman, H.; Patil, N.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro-Oncol. 2019, 21, v1–v100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamimi, A.F.; Juweid, M. Epidemiology and outcome of glioblastoma. In Glioblastoma; Codon Publications: Brisbane, AU, USA, 2018; pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Dasari, A.; Saini, M.; Sharma, S.; Bergemann, R. Pro15 healthcare resource utilisation and economic burden of glioblastoma in the United States: A systematic review. Value Health 2020, 23, S331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Mason, W.P.; Van Den Bent, M.J.; Weller, M.; Fisher, B.; Taphoorn, M.J.; Belanger, K.; Brandes, A.A.; Marosi, C.; Bogdahn, U.; et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasci, E.; Popa, M.; Zhuge, Y.; Chappidi, S.; Zhang, L.; Zgela, T.C.; Sproull, M.; Mackey, M.; Kates, H.R.; Garrett, T.J. MetaWise: Combined feature selection and weighting method to link the serum metabolome to treatment response and survival in glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, K.; McArdle, O.; Forde, P.; Dunne, M.; Fitzpatrick, D.; O’Neill, B.; Faul, C. A clinical review of treatment outcomes in glioblastoma multiforme—The validation in a non-trial population of the results of a randomised Phase III clinical trial: Has a more radical approach improved survival? Br. J. Radiol. 2012, 85, e729–e733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Brain Tumors. Available online: https://www.aans.org/en/Patients/Neurosurgical-Conditions-and-Treatments/Brain-Tumors (accessed on 29 May 2025).

- Hanif, F.; Muzaffar, K.; Perveen, K.; Malhi, S.M.; Simjee, S.U. Glioblastoma multiforme: A review of its epidemiology and pathogenesis through clinical presentation and treatment. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2017, 18, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S.; Anbiaee, R.; Houshyari, M.; Laxmi; Sridhar, S.B.; Ashique, S.; Hussain, S.; Kumar, S.; Taj, T.; Akbarnejad, Z.; et al. Amino acid metabolism in glioblastoma pathogenesis, immune evasion, and treatment resistance. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhn, N.; Hounchonou, H.F.; Nay, S.; Schwenkenbecher, P.; Grote-Levi, L.; Al-Tarawni, F.; Esmaeilzadeh, M.; Schuchardt, S.; Schwabe, K.; Hildebrandt, H.; et al. Metabolomic profile of cerebrospinal fluid from patients with diffuse gliomas. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 6970–6982, Erratum in J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 7654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-024-12722-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Pan, Z.; Li, B.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, S.; Qi, Y.; Qiu, J.; Gao, Z.; Fan, Y.; Guo, Q.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment Landscape in Glioblastoma Reveals Tumor Heterogeneity and Implications for Prognosis and Immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 820673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.B.; Karpova, A.; Gritsenko, M.A.; Kyle, J.E.; Cao, S.; Li, Y.; Rykunov, D.; Colaprico, A.; Rothstein, J.H.; Hong, R.; et al. Proteogenomic and metabolomic characterization of human glioblastoma. Cancer Cell 2021, 39, 509–528.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanovich-Arad, G.; Ofek, P.; Yeini, E.; Mardamshina, M.; Danilevsky, A.; Shomron, N.; Grossman, R.; Satchi-Fainaro, R.; Geiger, T. Proteogenomics of glioblastoma associates molecular patterns with survival. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, R.; Taillibert, S.; Kanner, A.; Read, W.; Steinberg, D.M.; Lhermitte, B.; Toms, S.; Idbaih, A.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Fink, K.; et al. Effect of Tumor-Treating Fields Plus Maintenance Temozolomide vs Maintenance Temozolomide Alone on Survival in Patients With Glioblastoma: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 318, 2306–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stupp, R.; Hegi, M.E.; Gorlia, T.; Erridge, S.C.; Perry, J.; Hong, Y.K.; Aldape, K.D.; Lhermitte, B.; Pietsch, T.; Grujicic, D.; et al. Cilengitide combined with standard treatment for patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter (CENTRIC EORTC 26071-22072 study): A multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalamarty, S.S.K.; Filipczak, N.; Li, X.; Subhan, M.A.; Parveen, F.; Ataide, J.A.; Rajmalani, B.A.; Torchilin, V.P. Mechanisms of Resistance and Current Treatment Options for Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). Cancers 2023, 15, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.W.; Verhaak, R.G.; McKenna, A.; Campos, B.; Noushmehr, H.; Salama, S.R.; Zheng, S.; Chakravarty, D.; Sanborn, J.Z.; Berman, S.H.; et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 2013, 155, 462–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaak, R.G.; Hoadley, K.A.; Purdom, E.; Wang, V.; Qi, Y.; Wilkerson, M.D.; Miller, C.R.; Ding, L.; Golub, T.; Mesirov, J.P.; et al. Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, M.S.; Abdel-Rasol, M.A.; El-Sayed, W.M. Emerging therapeutic strategies in glioblastsoma: Drug repurposing, mechanisms of resistance, precision medicine, and technological innovations. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 25, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.K.; Jermakowicz, A.; Mookhtiar, A.K.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Schürer, S.C.; Ayad, N.G. Drug Repositioning in Glioblastoma: A Pathway Perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa-Coelho, A.L.; Solaković, B.; Bento, A.D.; Fernandes, M.T. Drug Repurposing for Targeting Cancer Stem-like Cells in Glioblastoma. Cancers 2025, 17, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhares, P.; Carvalho, B.; Vaz, R.; Costa, B.M. Glioblastoma: Is There Any Blood Biomarker with True Clinical Relevance? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntafoulis, I.; Koolen, S.L.W.; van Tellingen, O.; den Hollander, C.W.J.; Sabel-Goedknegt, H.; Dijkhuizen, S.; Haeck, J.; Reuvers, T.G.A.; de Bruijn, P.; van den Bosch, T.P.P.; et al. A Repurposed Drug Selection Pipeline to Identify CNS-Penetrant Drug Candidates for Glioblastoma. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Shyr, Z.; McDaniel, K.; Fang, Y.; Tao, D.; Chen, C.Z.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, Q. Reversal Gene Expression Assessment for Drug Repurposing, a Case Study of Glioblastoma. Res. Sq. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcuello, C.; Lim, K.; Nisini, G.; Pokrovsky, V.S.; Conde, J.; Ruggeri, F.S. Nanoscale Analysis beyond Imaging by Atomic Force Microscopy: Molecular Perspectives on Oncology and Neurodegeneration. Small Sci. 2025, 5, e202500351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, N.; Hasib, M.H.H.; Ibironke, B.; Block, C.; Hughes, J.; Ekpenyong, A.; Sarkar, A. Exploring the heterogeneity in glioblastoma cellular mechanics using in-vitro assays and atomic force microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Sun, M.; Huang, H.; Jin, W.-L. Drug repurposing for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, I.; Elisseeff, A. An introduction to variable and feature selection. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1157–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Tasci, E.; Zhuge, Y.; Camphausen, K.; Krauze, A.V. Bias and Class Imbalance in Oncologic Data—Towards Inclusive and Transferrable AI in Large Scale Oncology Data Sets. Cancers 2022, 14, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IterativeImputer. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.impute.IterativeImputer.html (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Fawcett, T. An introduction to ROC analysis. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, M.; Park, A.; Kim, K.; Son, W.-J.; Lee, H.S.; Lim, G.; Lee, J.; Lee, D.H.; An, J.; Kim, J.H. A deep learning model for cell growth inhibition IC50 prediction and its application for gastric cancer patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, W.M.; Ali, N.A. Missing value imputation techniques: A survey. UHD J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 7, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gelman, A.; Hill, J.; Su, Y.-S.; Kropko, J. On the stationary distribution of iterative imputations. Biometrika 2014, 101, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imputation of Missing Values. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/impute.html#impute (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Yang, X.; Yang, J.A.; Liu, B.H.; Liao, J.M.; Yuan, F.E.; Tan, Y.Q.; Chen, Q.X. TGX-221 inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 38, 2836–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Satani, N.; Hammoudi, N.; Yan, V.C.; Barekatain, Y.; Khadka, S.; Ackroyd, J.J.; Georgiou, D.K.; Pham, C.D.; Arthur, K.; et al. An enolase inhibitor for the targeted treatment of ENO1-deleted cancers. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 1413–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Xie, B.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, X.; Deng, J.; Li, K.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, A.; Liu, Y. Comprehensive analysis of immune subtype characterization on identification of potential cells and drugs to predict response to immune checkpoint inhibitors for hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes. Dis. 2025, 12, 101471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, J.; Chen, S.; Sun, L.; Li, K.; Lai, G.; Peng, B.; Zhong, X.; Xie, B. Artificial intelligence in ovarian cancer drug resistance advanced 3PM approach: Subtype classification and prognostic modeling. EPMA J. 2024, 15, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Soares, J.; Greninger, P.; Edelman, E.J.; Lightfoot, H.; Forbes, S.; Bindal, N.; Beare, D.; Smith, J.A.; Thompson, I.R. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): A resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D955–D961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasci, E.; Chappidi, S.; Zhuge, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cooley Zgela, T.; Sproull, M.; Mackey, M.; Camphausen, K.; Krauze, A.V. GLIO-Select: Machine Learning-Based Feature Selection and Weighting of Tissue and Serum Proteomic and Metabolomic Data Uncovers Sex Differences in Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| GDSC1 Dataset | GDSC2 Dataset | |

|---|---|---|

| Total # of Instances | 968 | 963 |

| # of GBM/# of Non-GBM | 33/935 | 34/929 |

| Total # of Features | 378 | 286 |

| Feature Selection Methods | mRMR + LASSO | |

| Cross-Validation Type | Stratified 5-fold CV | |

| Classification Model | Random Forest | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tasci, E.; Camphausen, K.; Krauze, A.V. Drug Repurposing in Glioblastoma Using a Machine Learning-Based Hybrid Feature Selection Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411871

Tasci E, Camphausen K, Krauze AV. Drug Repurposing in Glioblastoma Using a Machine Learning-Based Hybrid Feature Selection Approach. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411871

Chicago/Turabian StyleTasci, Erdal, Kevin Camphausen, and Andra Valentina Krauze. 2025. "Drug Repurposing in Glioblastoma Using a Machine Learning-Based Hybrid Feature Selection Approach" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411871

APA StyleTasci, E., Camphausen, K., & Krauze, A. V. (2025). Drug Repurposing in Glioblastoma Using a Machine Learning-Based Hybrid Feature Selection Approach. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411871