Free GPIs and Comparison of GPI Structures Among Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

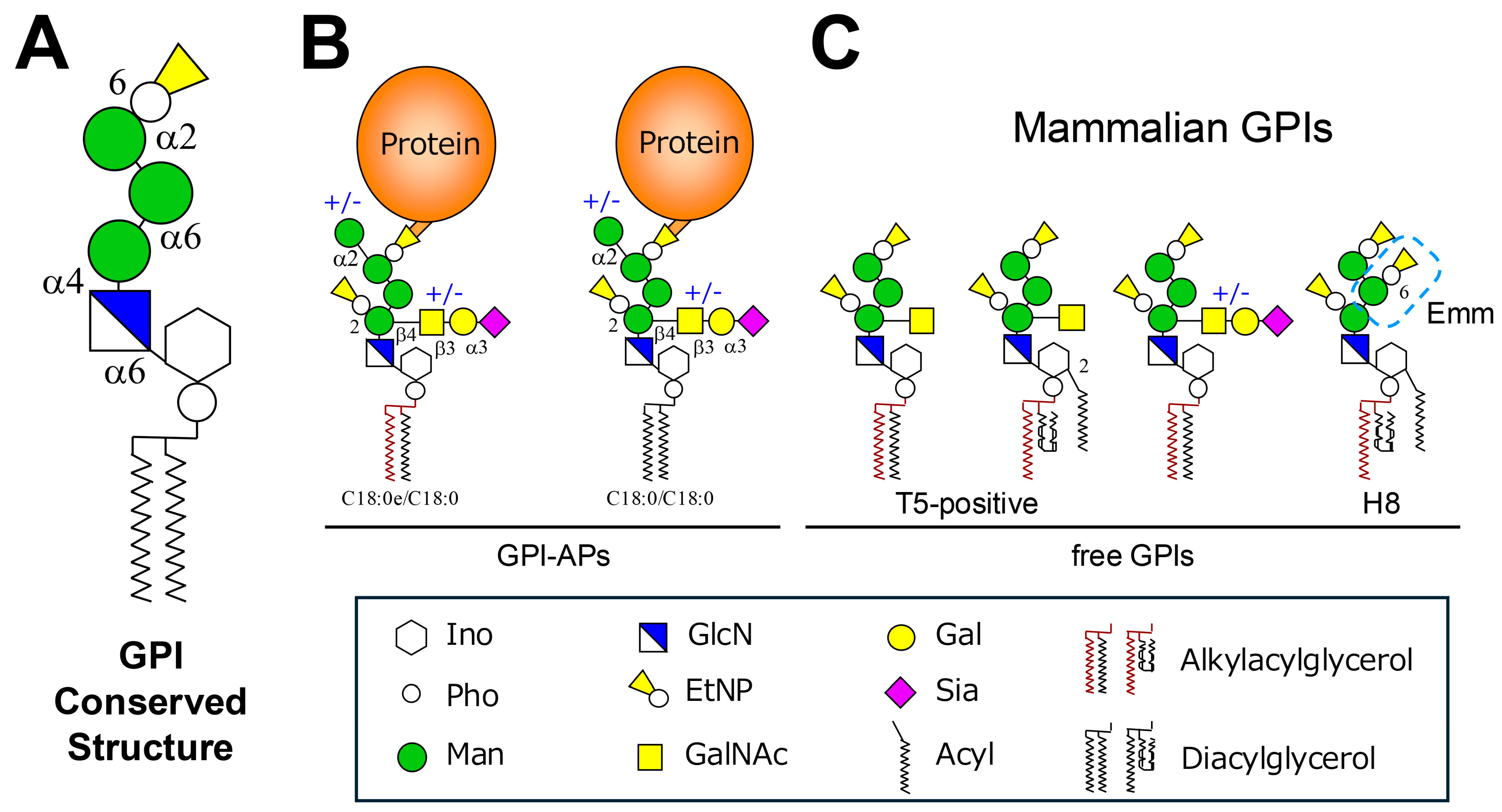

2. Structure and Biosynthesis of GPI and GPI-APs in Mammals

2.1. Structure of GPI and GPI-APs in Mammals

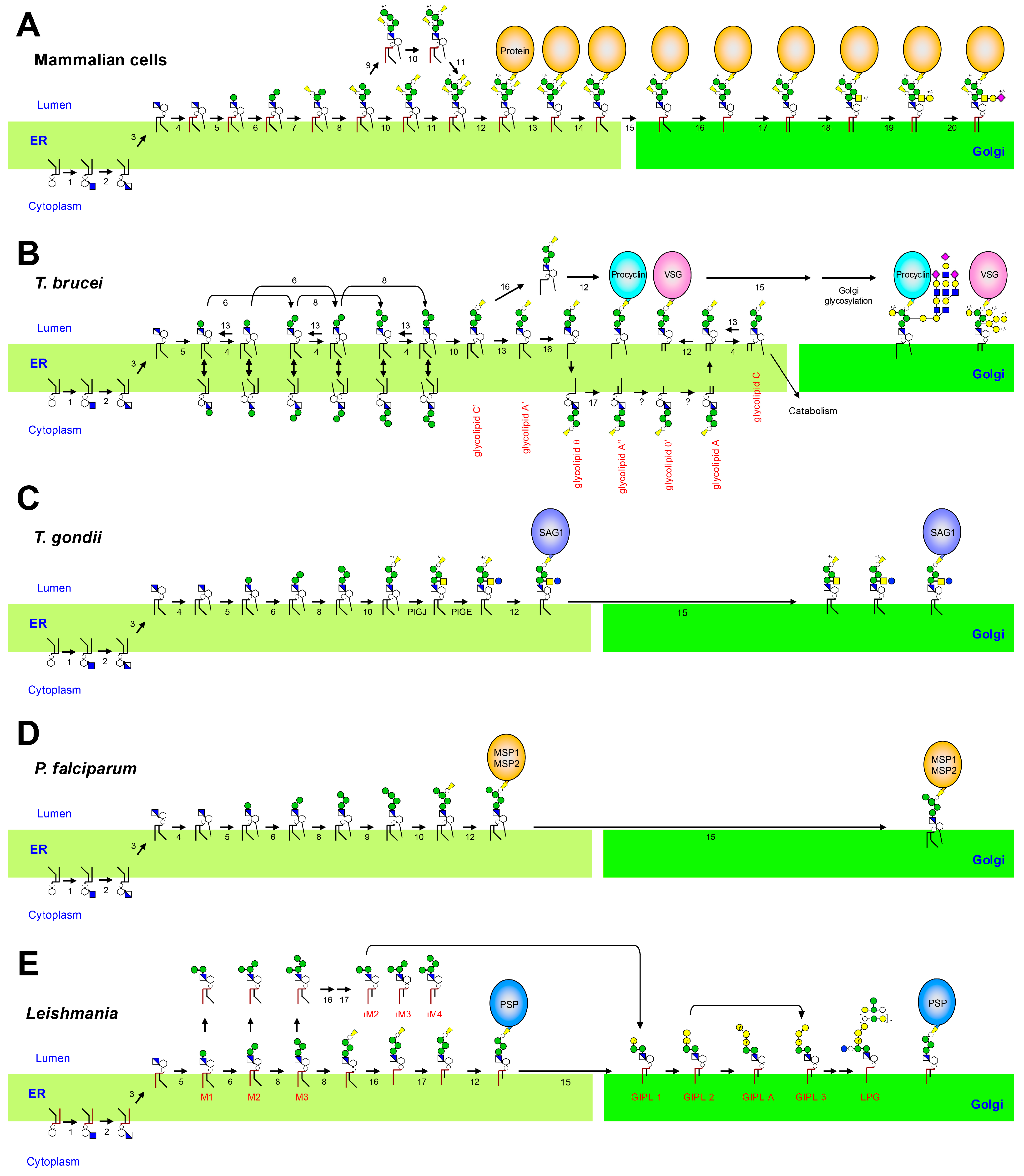

2.2. Biosynthesis of GPI-APs in Mammals

2.3. Free GPIs in Mammals

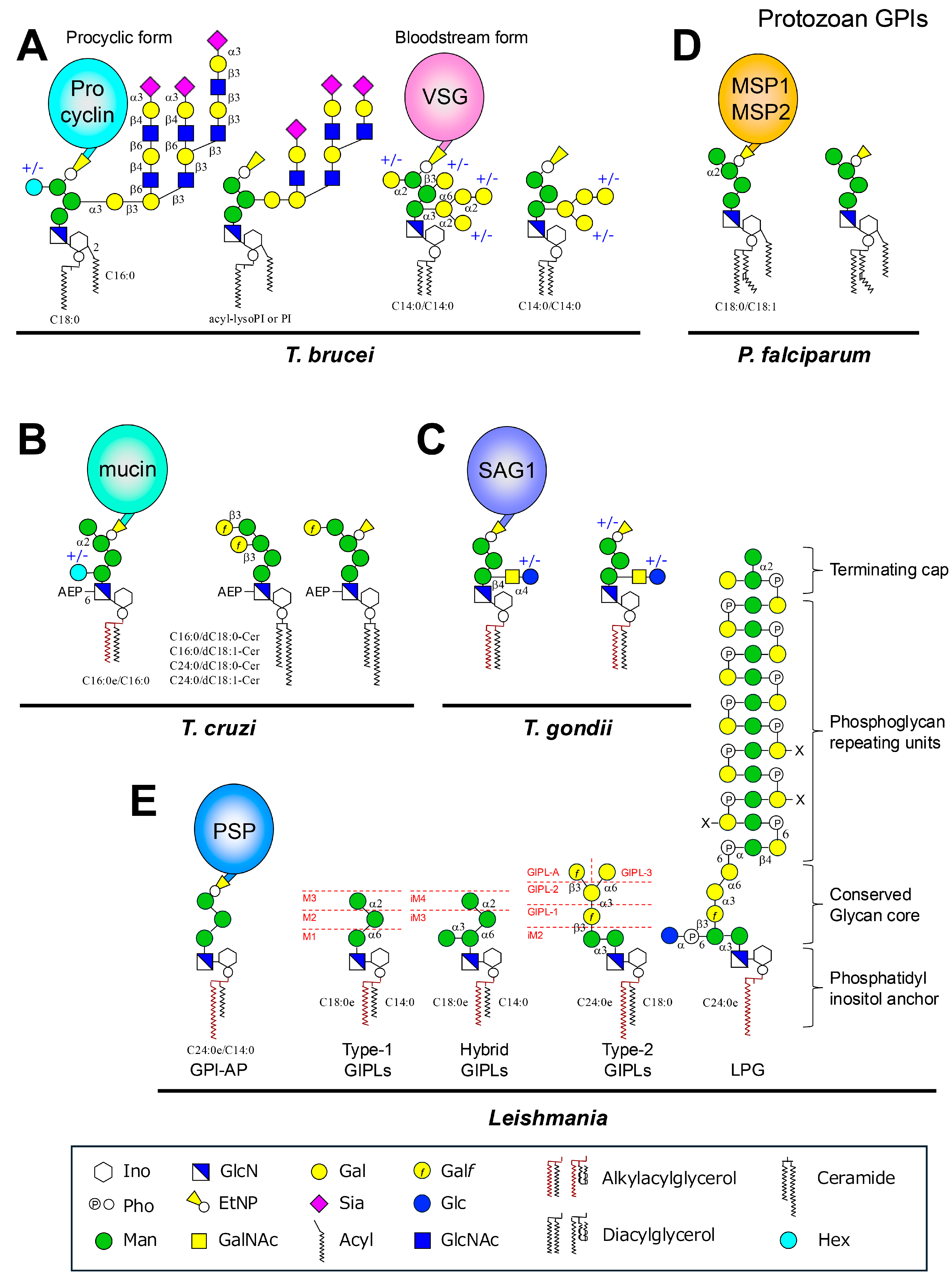

3. Structure and Biosynthesis of GPI and GPI-APs in Trypanosoma brucei

3.1. Life Cycle of T. brucei and Disease

3.2. Structure of GPI and GPI-APs in T. brucei

3.3. Biosynthetic Differences in T. brucei

3.3.1. Acylation Timing

3.3.2. Fatty Acid Remodeling

3.3.3. Side-Chain Addition

4. Structure and Biosynthesis of GPI and GPI-APs in Trypanosoma cruzi

4.1. Life Cycle of T. cruzi and Disease

4.2. Structure of GPI and GPI-APs in T. cruzi

5. Structure and Biosynthesis of GPI and GPI-APs in Toxoplasma gondii

5.1. Life Cycle of T. gondii and Disease

5.2. Structure of GPI and GPI-APs in T. gondii

5.3. Biosynthetic Differences in T. gondii

6. Structure and Biosynthesis of GPI and GPI-APs in Plasmodium falciparum

6.1. Life Cycle of P. falciparum and Disease

6.2. Structure of GPI and GPI-APs in P. falciparum

6.3. Biosynthetic Differences in P. falciparum

7. Structure and Biosynthesis of GPI and GPI-APs in Leishmania spp.

7.1. Life Cycle of Leishmania and Disease

7.2. Structure of GPI and GPI-APs in Leishmania

7.3. Biosynthetic Differences in Leishmania

8. Physiological and Pathological Roles of Free GPI in Protozoan Parasites

8.1. Immune Modulation

8.2. Growth and Transmission

9. Physiological and Pathological Roles of Free GPI in Mammals

9.1. Inflammation and Complement Dysregulation

9.2. Blood Group Antigen

10. Conclusions and Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kinoshita, T. Biosynthesis and biology of mammalian GPI-anchored proteins. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 190290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiser, M.F. Unique Endomembrane Systems and Virulence in Pathogenic Protozoa. Life 2021, 11, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Liang, L.N.; Tykocinski, M.L.; Tartakoff, A.M. A novel class of cell surface glycolipids of mammalian cells. Free glycosyl phosphatidylinositols. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 12879–12884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hirata, T.; Maeda, Y.; Murakami, Y.; Fujita, M.; Kinoshita, T. Free, unlinked glycosylphosphatidylinositols on mammalian cell surfaces revisited. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 5038–5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, P.A.; Murakami, Y.; Malik, A.; Seeberger, P.H.; Kinoshita, T.; Varon Silva, D. Rescue of Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchored Protein Biosynthesis Using Synthetic Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Oligosaccharides. ACS Chem. Biol. 2021, 16, 2297–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Menon, A.K.; Maki, Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Iwasaki, Y.; Fujita, M.; Guerrero, P.A.; Silva, D.V.; Seeberger, P.H.; Murakami, Y.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen reveals CLPTM1L as a lipid scramblase required for efficient glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2115083119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, N.A.; Vidugiriene, J.; Machamer, C.E.; Menon, A.K. Cell surface display and intracellular trafficking of free glycosylphosphatidylinositols in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 7378–7389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Maeda, Y.; Liu, Y.S.; Takada, Y.; Ninomiya, A.; Hirata, T.; Fujita, M.; Murakami, Y.; Kinoshita, T. Cross-talks of glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis with glycosphingolipid biosynthesis and ER-associated degradation. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Gao, X.D.; Murakami, Y.; Fujita, M.; Kinoshita, T. Accumulated precursors of specific GPI-anchored proteins upregulate GPI biosynthesis with ARV1. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 222, e202208159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, B.; Peyvandi, F. How I treat thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in pregnancy. Blood 2020, 136, 2125–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, H.; O’Reilly, A.J.; Sternberg, J.; Field, M.C. An extensive endoplasmic reticulum-localised glycoprotein family in trypanosomatids. Microb. Cell 2014, 1, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guha-Niyogi, A.; Sullivan, D.R.; Turco, S.J. Glycoconjugate structures of parasitic protozoa. Glycobiology 2001, 11, 45R–59R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevor, C.E.; Gonzalez-Munoz, A.L.; Macleod, O.J.S.; Woodcock, P.G.; Rust, S.; Vaughan, T.J.; Garman, E.F.; Minter, R.; Carrington, M.; Higgins, M.K. Structure of the trypanosome transferrin receptor reveals mechanisms of ligand recognition and immune evasion. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 2074–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, M.D.; Gadelha, C. A transferrin receptor’s guide to African trypanosomes. Cell Surf. 2023, 9, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassella, E.; Butikofer, P.; Engstler, M.; Jelk, J.; Roditi, I. Procyclin null mutants of Trypanosoma brucei express free glycosylphosphatidylinositols on their surface. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 1308–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, S.; Menon, A.K.; Cross, G.A. Galactose-containing glycosylphosphatidylinositols in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamune, K.; Nozaki, T.; Maeda, Y.; Ohishi, K.; Fukuma, T.; Hara, T.; Schwarz, R.T.; Sutterlin, C.; Brun, R.; Riezman, H.; et al. Critical roles of glycosylphosphatidylinositol for Trypanosoma brucei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10336–10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knusel, S.; Jenni, A.; Benninger, M.; Butikofer, P.; Roditi, I. Persistence of Trypanosoma brucei as early procyclic forms and social motility are dependent on glycosylphosphatidylinositol transamidase. Mol. Microbiol. 2022, 117, 802–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guther, M.L.; Lee, S.; Tetley, L.; Acosta-Serrano, A.; Ferguson, M.A. GPI-anchored proteins and free GPI glycolipids of procyclic form Trypanosoma brucei are nonessential for growth, are required for colonization of the tsetse fly, and are not the only components of the surface coat. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 5265–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Siripanyapinyo, U.; Hong, Y.; Kang, J.Y.; Ishihara, S.; Nakakuma, H.; Maeda, Y.; Kinoshita, T. PIG-W is critical for inositol acylation but not for flipping of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor. Mol. Biol. Cell 2003, 14, 4285–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Maeda, Y.; Tashima, Y.; Kinoshita, T. Inositol deacylation of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins is mediated by mammalian PGAP1 and yeast Bst1p. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 14256–14263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guther, M.L.; Prescott, A.R.; Ferguson, M.A. Deletion of the GPIdeAc gene alters the location and fate of glycosylphosphatidylinositol precursors in Trypanosoma brucei. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 14532–14540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Nagamune, K.; Morita, Y.S.; Nakatani, F.; Ashida, H.; Maeda, Y.; Kinoshita, T. Removal or maintenance of inositol-linked acyl chain in glycosylphosphatidylinositol is critical in trypanosome life cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 11595–11602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudyal, N.R.; Paul, K.S. Fatty acid uptake in Trypanosoma brucei: Host resources and possible mechanisms. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 949409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, Y.; Tashima, Y.; Houjou, T.; Fujita, M.; Yoko-o, T.; Jigami, Y.; Taguchi, R.; Kinoshita, T. Fatty acid remodeling of GPI-anchored proteins is required for their raft association. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 1497–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Nagar, R.; Duncan, S.M.; Sampaio Guther, M.L.; Ferguson, M.A.J. Identification of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase A2 (GPI-PLA2) that mediates GPI fatty acid remodeling in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.H.; Fujita, M.; Takaoka, K.; Murakami, Y.; Fujihara, Y.; Kanzawa, N.; Murakami, K.I.; Kajikawa, E.; Takada, Y.; Saito, K.; et al. A GPI processing phospholipase A2, PGAP6, modulates Nodal signaling in embryos by shedding CRIPTO. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 215, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaquenoud, M.; Pagac, M.; Signorell, A.; Benghezal, M.; Jelk, J.; Butikofer, P.; Conzelmann, A. The Gup1 homologue of Trypanosoma brucei is a GPI glycosylphosphatidylinositol remodelase. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 67, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxbaum, L.U.; Milne, K.G.; Werbovetz, K.A.; Englund, P.T. Myristate exchange on the Trypanosoma brucei variant surface glycoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Maeda, Y.; Ra, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Taguchi, R.; Kinoshita, T. GPI glycan remodeling by PGAP5 regulates transport of GPI-anchored proteins from the ER to the Golgi. Cell 2009, 139, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, S.M.; Nagar, R.; Damerow, M.; Yashunsky, D.V.; Buzzi, B.; Nikolaev, A.V.; Ferguson, M.A.J. A Trypanosoma brucei beta3 glycosyltransferase superfamily gene encodes a beta1-6 GlcNAc-transferase mediating N-glycan and GPI anchor modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engstler, M.; Reuter, G.; Schauer, R. The developmentally regulated trans-sialidase from Trypanosoma brucei sialylates the procyclic acidic repetitive protein. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1993, 61, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, F.; Morita, Y.S.; Ashida, H.; Nagamune, K.; Maeda, Y.; Kinoshita, T. Identification of a second catalytically active trans-sialidase in Trypanosoma brucei. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 415, 421–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Neto, M.A.; Carneiro, A.B.; Silva-Cardoso, L.; Atella, G.C. Lysophosphatidylcholine: A Novel Modulator of Trypanosoma cruzi Transmission. J. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 2012, 625838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodskyn, C.; Patricio, J.; Oliveira, R.; Lobo, L.; Arnholdt, A.; Mendonca-Previato, L.; Barral, A.; Barral-Netto, M. Glycoinositolphospholipids from Trypanosoma cruzi interfere with macrophages and dendritic cell responses. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 3736–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lederkremer, R.M.; Lima, C.; Ramirez, M.I.; Ferguson, M.A.; Homans, S.W.; Thomas-Oates, J. Complete structure of the glycan of lipopeptidophosphoglycan from Trypanosoma cruzi Epimastigotes. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 23670–23675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, G.E.; Mesias, A.C.; Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Buscaglia, C.A. Structural features affecting trafficking, processing, and secretion of Trypanosoma cruzi mucins. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 26365–26376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Flores, C.J.; Mondragon-Flores, R. Comprehensive analysis of Toxoplasma gondii migration routes and tissue dissemination in the host. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2025, 19, e0013369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striepen, B.; Zinecker, C.F.; Damm, J.B.; Melgers, P.A.; Gerwig, G.J.; Koolen, M.; Vliegenthart, J.F.; Dubremetz, J.F.; Schwarz, R.T. Molecular structure of the “low molecular weight antigen” of Toxoplasma gondii: A glucose alpha 1-4 N-acetylgalactosamine makes free glycosyl-phosphatidylinositols highly immunogenic. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 266, 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.A.; Gas-Pascual, E.; Malhi, S.; Sanchez-Arcila, J.C.; Njume, F.N.; van der Wel, H.; Zhao, Y.; Garcia-Lopez, L.; Ceron, G.; Posada, J.; et al. The GPI sidechain of Toxoplasma gondii inhibits parasite pathogenesis. mBio 2024, 15, e0052724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehus, S.; Smith, T.K.; Azzouz, N.; Campos, M.A.; Dubremetz, J.F.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Schwarz, R.T.; Debierre-Grockiego, F. Virulent and avirulent strains of Toxoplasma gondii which differ in their glycosylphosphatidylinositol content induce similar biological functions in macrophages. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debierre-Grockiego, F.; Campos, M.A.; Azzouz, N.; Schmidt, J.; Bieker, U.; Resende, M.G.; Mansur, D.S.; Weingart, R.; Schmidt, R.R.; Golenbock, D.T.; et al. Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by glycosylphosphatidylinositols derived from Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, C.E.; Sukhumavasi, W.; Butcher, B.A.; Denkers, E.Y. Functional aspects of Toll-like receptor/MyD88 signalling during protozoan infection: Focus on Toxoplasma gondii. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 156, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debierre-Grockiego, F.; Niehus, S.; Coddeville, B.; Elass, E.; Poirier, F.; Weingart, R.; Schmidt, R.R.; Mazurier, J.; Guerardel, Y.; Schwarz, R.T. Binding of Toxoplasma gondii glycosylphosphatidylinositols to galectin-3 is required for their recognition by macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 32744–32750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberione, M.P.; Avalos-Padilla, Y.; Rangel, G.W.; Ramirez, M.; Romero-Urunuela, T.; Fenollar, A.; Ortega-Barrionuevo, J.; Crispim, M.; Smith, T.K.; Llinas, M.; et al. Hexosamine biosynthesis disruption impairs GPI production and arrests Plasmodium falciparum growth at schizont stages. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda, D.C.; Miller, L.H. Glycosylation in malaria parasites: What do we know? Trends Parasitol. 2024, 40, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaki, D.A.; Elbasheir, M.M. Plasmodium falciparum and immune phagocytosis: Characterization of the process. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2025, 103, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, R.; Reiling, L.; Feng, G.; Drew, D.R.; Mueller, I.; Siba, P.M.; Tsuboi, T.; Richards, J.S.; Fowkes, F.J.I.; Beeson, J.G. The association between naturally acquired IgG subclass specific antibodies to the PfRH5 invasion complex and protection from Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbengue, B.; Niang, B.; Niang, M.S.; Varela, M.L.; Fall, B.; Fall, M.M.; Diallo, R.N.; Diatta, B.; Gowda, D.C.; Dieye, A.; et al. Inflammatory cytokine and humoral responses to Plasmodium falciparum glycosylphosphatidylinositols correlates with malaria immunity and pathogenesis. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2016, 4, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockenhaupt, F.P.; Cramer, J.P.; Hamann, L.; Stegemann, M.S.; Eckert, J.; Oh, N.R.; Otchwemah, R.N.; Dietz, E.; Ehrhardt, S.; Schroder, N.W.; et al. Toll-like receptor (TLR) polymorphisms in African children: Common TLR-4 variants predispose to severe malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, R.R.; Ibraim, I.C.; Noronha, F.S.; Turco, S.J.; Soares, R.P. Glycoinositolphospholipids from Leishmania braziliensis and L. infantum: Modulation of innate immune system and variations in carbohydrate structure. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilley, J.D.; Zawadzki, J.L.; McConville, M.J.; Coombs, G.H.; Mottram, J.C. Leishmania mexicana mutants lacking glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI):protein transamidase provide insights into the biosynthesis and functions of GPI-anchored proteins. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConville, M.J.; Homans, S.W.; Thomas-Oates, J.E.; Dell, A.; Bacic, A. Structures of the glycoinositolphospholipids from Leishmania major. A family of novel galactofuranose-containing glycolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 7385–7394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestier, C.L.; Gao, Q.; Boons, G.J. Leishmania lipophosphoglycan: How to establish structure-activity relationships for this highly complex and multifunctional glycoconjugate? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spath, G.F.; Garraway, L.A.; Turco, S.J.; Beverley, S.M. The role(s) of lipophosphoglycan (LPG) in the establishment of Leishmania major infections in mammalian hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 9536–9541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, L.H.; Beverley, S.M.; Zamboni, D.S. Innate immune activation and subversion of Mammalian functions by Leishmania lipophosphoglycan. J. Parasitol. Res. 2012, 2012, 165126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Barron, T.; Turco, S.J.; Beverley, S.M. The LPG1 gene family of Leishmania major. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2004, 136, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgoutz, S.C.; Zawadzki, J.L.; Ralton, J.E.; McConville, M.J. Evidence that free GPI glycolipids are essential for growth of Leishmania mexicana. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 2746–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.; Rosat, J.P.; Ransijn, A.; Ferguson, M.A.; McConville, M.J. Characterization of glycoinositol phospholipids in the amastigote stage of the protozoan parasite Leishmania major. Biochem. J. 1993, 295 Pt 2, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, L.; O’Donnell, C.A.; Liew, F.Y. Glycoinositolphospholipids of Leishmania major inhibit nitric oxide synthesis and reduce leishmanicidal activity in murine macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 1995, 25, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, P.; Peng, H.; Chen, J. Toxoplasma gondii-derived nanocarriers: Leveraging protozoan membrane biology for scalable immune modulation and therapeutic delivery. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 54, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, I.C.; Camargo, M.M.; Procopio, D.O.; Silva, L.S.; Mehlert, A.; Travassos, L.R.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Ferguson, M.A. Highly purified glycosylphosphatidylinositols from Trypanosoma cruzi are potent proinflammatory agents. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 1476–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochsmann, B.; Murakami, Y.; Osato, M.; Knaus, A.; Kawamoto, M.; Inoue, N.; Hirata, T.; Murata, S.; Anliker, M.; Eggermann, T.; et al. Complement and inflammasome overactivation mediates paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria with autoinflammation. J. Clin. Invest 2019, 129, 5123–5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Che, M.; Zeng, L.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Fu, R. The immunologic abnormalities in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria are associated with disease progression. Saudi Med. J. 2024, 45, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, R.; Nicolas, G.; Willemetz, A.; Murakami, Y.; Mikdar, M.; Vrignaud, C.; Megahed, H.; Cartron, J.P.; Masson, C.; Wehbi, S.; et al. Inherited glycosylphosphatidylinositol defects cause the rare Emm-negative blood phenotype and developmental disorders. Blood 2021, 137, 3660–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, W.J.; Aeschlimann, J.; Vege, S.; Lomas-Francis, C.; Burgos, A.; Mah, H.H.; Halls, J.B.L.; Baeck, P.; Ligthart, P.C.; Veldhuisen, B.; et al. PIGG defines the Emm blood group system. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ihim, S.A.; Fujita, M. Free GPIs and Comparison of GPI Structures Among Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311592

Ihim SA, Fujita M. Free GPIs and Comparison of GPI Structures Among Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311592

Chicago/Turabian StyleIhim, Stella Amarachi, and Morihisa Fujita. 2025. "Free GPIs and Comparison of GPI Structures Among Species" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311592

APA StyleIhim, S. A., & Fujita, M. (2025). Free GPIs and Comparison of GPI Structures Among Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311592