1. Introduction

The uniqueness of cell membranes is characterized by the presence of carbohydrate chains carried by glycoconjugates—glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and glycosphingolipids (GSLs)—which are essential for maintaining cellular membrane structure and function [

1]. This multitude and diversity in glycosylation patterns are not merely biological variations, but are critical for the precise regulation of cellular processes, underpinning essential functions such as signaling, adhesion, and immune recognition [

1]. In cancer, these patterns are often disrupted, contributing to tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis [

2]. Although the involvement of the glycan landscape in cancer progression is well recognized [

3], the molecular mechanisms underlying the generation of altered glycan structures in cancer cells remain poorly understood. Nevertheless, elucidating these mechanisms appears fundamental to reducing cancer-related mortality.

Sulfated glycosphingolipids, commonly known as sulfolipids (SLs), represent a unique class of anionic amphiphilic GSLs found in various cancers, including those of the brain, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, and breast [

4,

5]. These molecules are predominantly located in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane and are involved in cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions [

6]. Among SLs, sulfatide (3-O-sulfogalactosylceramide, SGalCer, SM4) is the most extensively studied [

6]. It is synthesized by galactosylceramide sulfotransferase (CST) and is highly expressed in the myelin sheath of oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells. Intriguingly, SM4 expression is frequently dysregulated in cancers, including colon, ovarian, gastric, renal, hepatocellular, lung, and breast carcinomas [

6,

7].

Our previous studies highlighted the essential role of CST and SM4 in the progression of breast cancer (BC). In particular, sulfatides present on the surface of breast cancer cells act as adhesive molecules, triggering their metastatic potential by facilitating interactions between cancer cells and platelets and endothelial cells [

7]. Moreover, SM4 acted as an enhancing molecule, increasing the expression of P-selectin in activated platelets [

7]. Using immunohistochemistry, we demonstrated that CST expression decreases as tumor malignancy grade increases, with significant differences observed between G1 and G3 breast cancer tumors. Additionally, high CST expression in invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) is associated with longer overall patient survival. Furthermore, high SM4 levels resulted in increased sensitivity of cancer cells to apoptosis induced by hypoxia and doxorubicin in vitro, and decreased tumorigenicity after transplantation into athymic nu/nu mice [

7]. Such a phenomenon has been associated with increased synthesis of SM4, resulting in a reduced level of its precursor, galactosylceramide—a molecule known for its anti-apoptotic properties [

7,

8,

9]. However, our data suggest that this pathway is not exclusive to the increased sensitivity to apoptosis. A comparative gene expression analysis between SM4-positive and SM4-negative BC cells revealed that various genes are differentially expressed in association with apoptosis potential.

Despite SM4′s role in apoptosis regulation, it is also crucial to consider its role in metastasis progression. The metastatic process is closely linked to cell migration and adhesion, primarily mediated by integrins, a class of heterodimeric transmembrane receptors composed of α and β subunits located on the cell surface, mediating adhesion between cells and the extracellular matrix [

10]. While certain integrins promote tumor progression, others have been shown to inhibit tumor cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis or cell death [

11]. Among them, β1 integrin, which constitutes the largest subgroup of integrins, is aberrantly expressed in breast cancer and is implicated in processes such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), angiogenesis, metastasis, and therapy resistance [

12]. Interactions between β1 integrin and extracellular matrix (ECM) components, such as fibronectin, can protect cancer cells from apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic agents, including doxorubicin and etoposide [

13]. β1 integrin has also been shown to regulate the transcriptional apoptotic machinery, enhancing the expression of anti-apoptotic BCL2, while concurrently downregulating pro-apoptotic genes such as BAX, caspase-3, and p21 [

14]. This protective effect is associated with inhibition of caspase-3 activation and PI3K-mediated suppression of mitochondrial cytochrome c release [

13]. Recent studies have suggested that sulfatide may influence the expression and activation of certain integrins, although the underlying mechanisms and functional consequences of this regulation are not yet fully understood [

15,

16].

Given the multifaceted roles of SM4 and its potential regulation of β1 integrin in breast cancer biology, this study aimed to elucidate further its particular role in mediating breast cancer cell resistance and tumorigenicity. We used cell lines with differential SM4 expression to investigate the interplay between sulfatide levels, integrin signaling, and cellular responses to chemotherapy.

3. Discussion

The impact of SM4 on cancer cell behavior after entering the bloodstream is clearly negative, as SM4 acts as a malignancy-related adhesive molecule that promotes metastasis [

7,

17,

18]. However, its role in the development of primary tumors remains unclear. On the one hand, we demonstrated that CST expression decreases with increasing tumor malignancy grade, with significant differences observed between G1 and G3 tumors. Additionally, high CST expression in IDC cells is associated with longer overall survival for patients, suggesting that higher CST levels may indicate a better prognosis [

6]. A clinical study involving IDC patients supports our observation that, in primary tumors, cancer cells rich in sulfatides are more likely to undergo apoptosis triggered by microenvironmental stressors such as hypoxia. This is because increased synthesis of this glycolipid reduces the levels of its precursor, GalCer, an anti-apoptotic molecule [

6,

12]. On the other hand, our data presented in this study indicate that SM4 on the surface of MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells directly influences the malignant properties of breast cancer cells by significantly increasing their invasiveness, thereby facilitating cancer cell movement into the tumor stroma.

The increase in invasiveness in cells with elevated levels of SM4 is most likely due to changes in the cell membrane structure associated with the formation of sulfatide clusters, commonly referred to as ”lipid rafts.” The proteins contained within these lipid rafts can modulate cell invasiveness, and available literature data suggest the potential involvement of SM4 in tumor cell invasiveness through regulation of integrins [

11,

12], which are a superfamily of cell adhesion receptors that bind to extracellular matrix ligands, cell-surface ligands, and soluble ligands [

13]. Integrins are essential for cell migration and invasion, not only because they directly mediate adhesion to the extracellular matrix but also because they regulate intracellular signaling pathways that, in turn, control cytoskeletal organization, force generation, and survival [

14]. They are transmembrane αβ heterodimers, and at least 18 α and 8 β subunits are known in humans, forming 24 heterodimers [

19]. Increased expression levels of integrins αvβ3 are closely associated with increased cell invasion and metastasis [

20]. Integrin α6 expression is also significantly upregulated in numerous carcinomas, including breast cancer [

21]. Expression of integrin α6β4 enhances tumor cell invasiveness and metastasis, especially in breast carcinomas [

22]. It has been shown that SM4 enhances cell invasiveness by activating Src kinase and increasing integrin αVβ3 expression [

16]. Our data indicate that SM4 present on the surface of BC cells does not affect mRNA expression levels of specific integrins. However, SM4 can modulate the quantity of integrins through post-translational regulation. Interestingly, several integrin β subunit family members, namely β3, β4, and β5, were elevated, which could result in increased invasiveness. However, a particularly intriguing observation was the decreased expression of the β1 subunit, which is the most common subunit and has emerged as a key mediator in cancer, influencing various aspects of cancer progression, including cell motility, adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and chemotherapy resistance [

23]. The role of β1 in this context is probably not associated with changes in cell invasiveness but rather with its impact on the signaling pathways, which will be discussed later.

As mentioned above, the accumulation of sulfatides in breast cancer cells correlates with increased sensitivity to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis [

7] by altering metabolism and reducing the amounts of GalCer, which acts directly as an anti-apoptotic molecule [

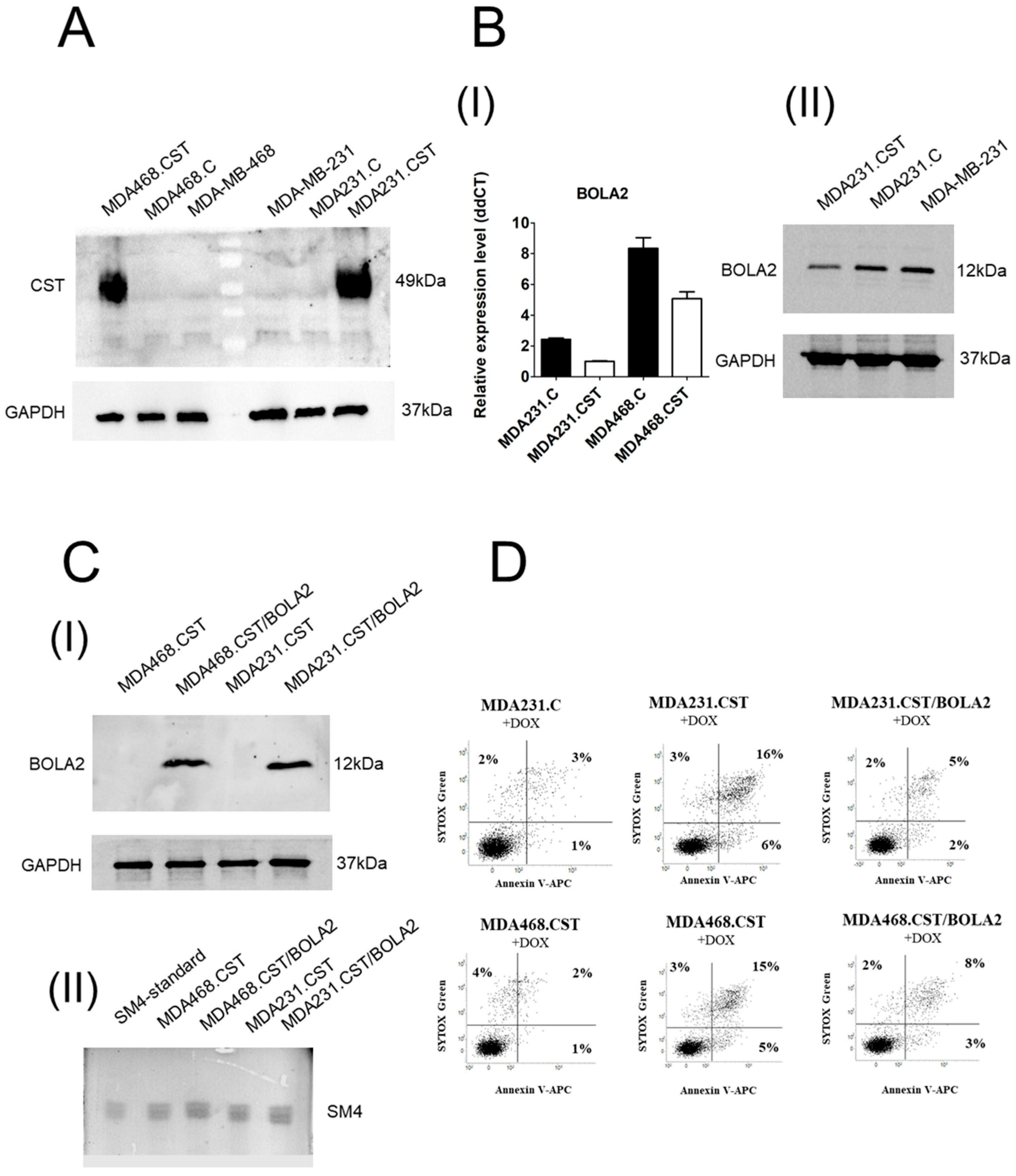

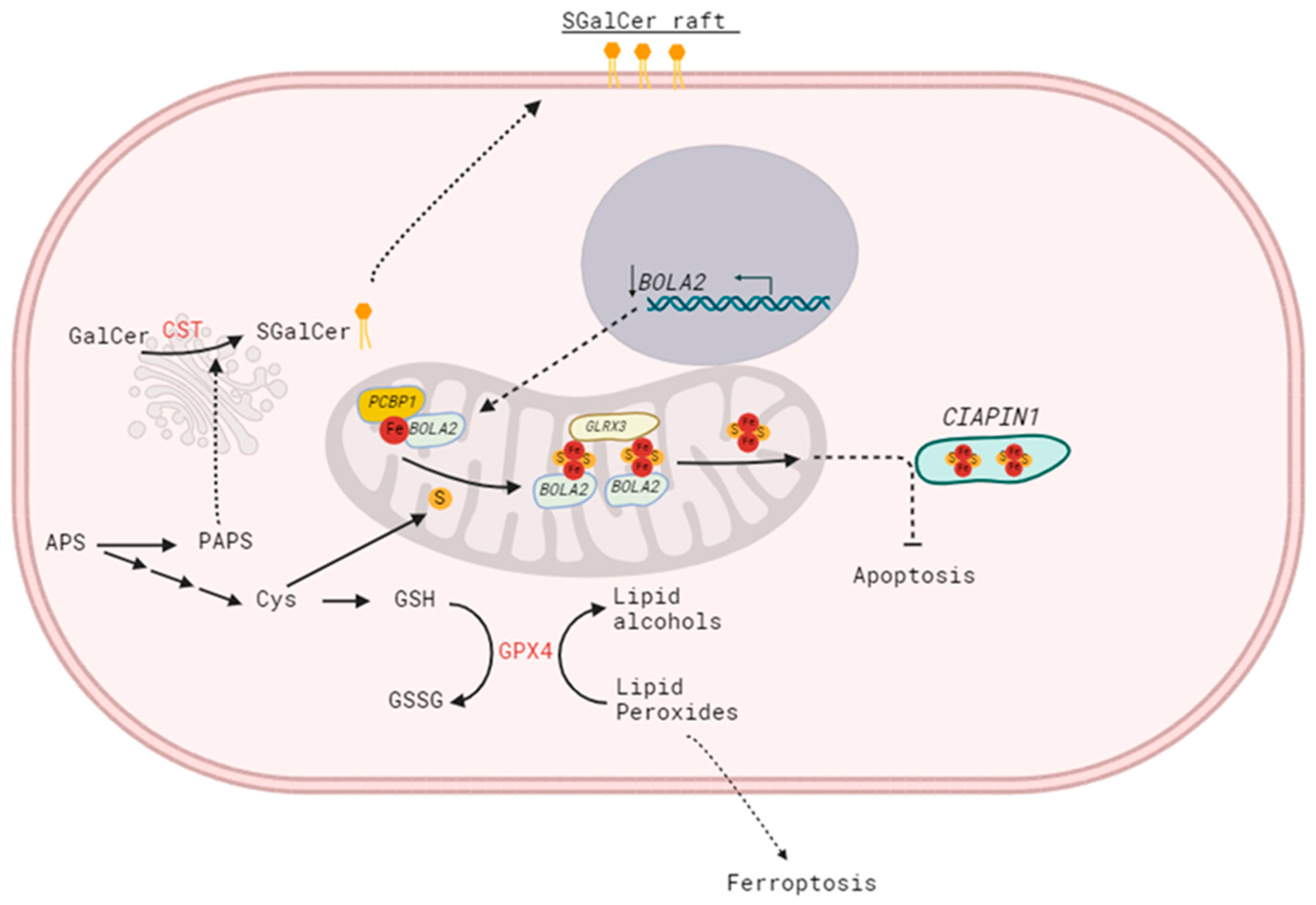

8]. However, our data suggest this is not the only pathway leading to increased sensitivity to apoptosis. The ability of SM4 to regulate gene expression remains a poorly understood phenomenon, but a comparative gene expression analysis between SM4-positive and SM4-negative BC cells revealed that various genes are differentially expressed in association with apoptosis potential. Among them, high CST expression correlated with down-regulated expression of the

BOLA2 gene, known to be involved in apoptosis through the CIAPIN1 pathway [

24]. The role of the

BOLA2 gene in the carcinogenesis of breast cancer cells, as well as the underlying mechanism, remains poorly understood. Interestingly, BOLA2 forms a distinct iron chaperone complex with Glx3 for the cytosolic [2Fe-2S] cluster, which can be directly transferred to the Fe-S protein Ciapin1 (cytokine-induced apoptosis inhibitor-1) in vitro. Incorporation of [2Fe-2S] into Ciapin1, a well-known regulator of apoptosis in many different cell types, is crucial for its activity [

25]. The sulfur source needed to form the [2Fe-2S] clusters is unclear, possibly provided by the cytosolic isoform of the cysteine desulfurase NFS1 or exported from the mitochondrial ISC (iron–sulfur cluster) pathway [

26]. Changes in BOLA2 expression suggest an alternative mechanism for sensitizing cells to apoptosis by blocking the proper redistribution of sulfur, as shown in

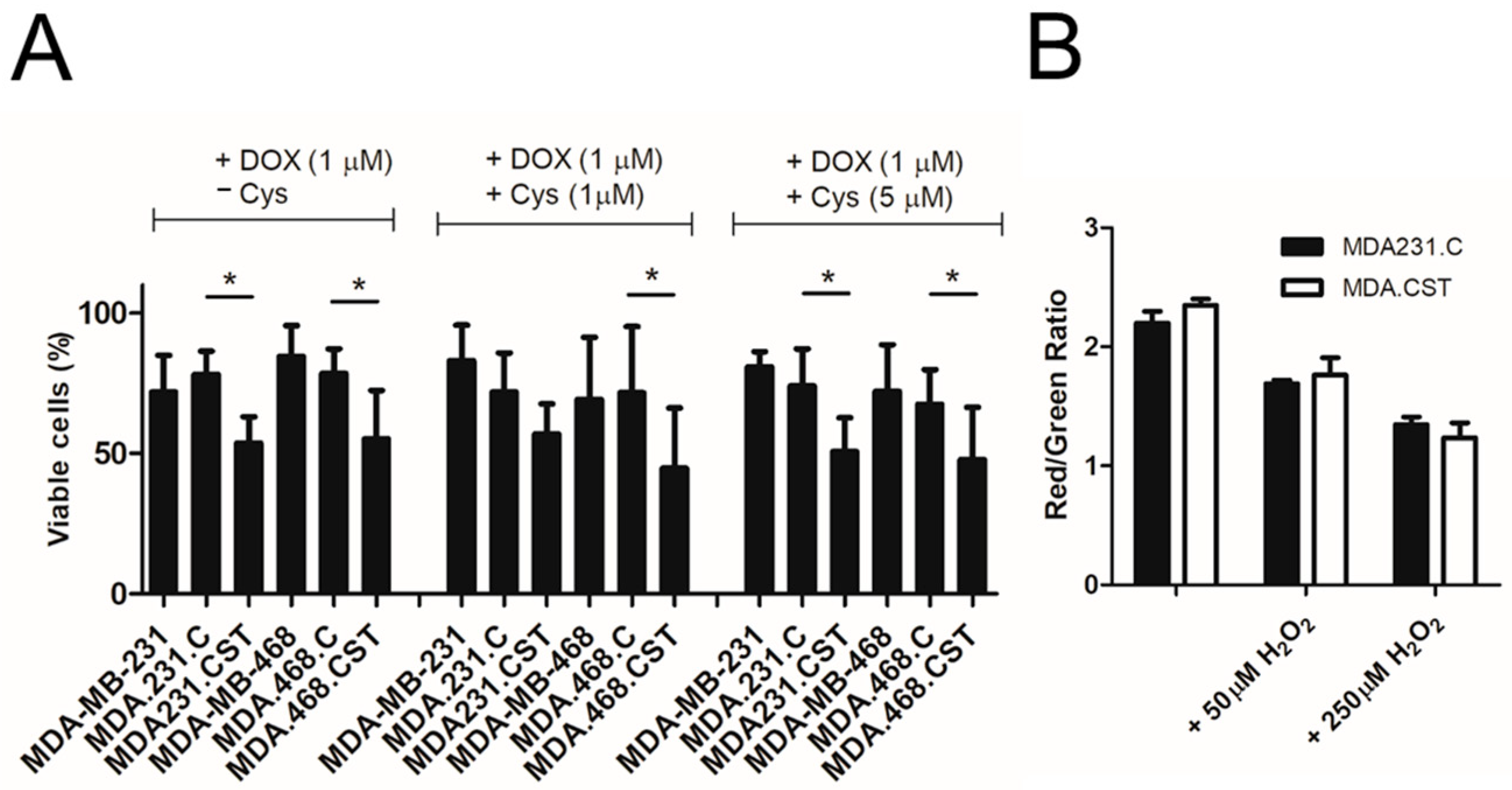

Figure 5. Although cysteine is the least abundant amino acid in the cell, evidence describes it as one of the most important amino acids for cell survival and growth [

27]. Cysteine biosynthesis through the sulfate assimilation pathway, which involves the transport of inorganic sulfate into the cell, could be disrupted in cancers with increased amounts of SM4, because the sulfur redistribution shifts toward conversion to PAPS (as mentioned earlier, PAPS serves as a donor for sulfotransferases like CST).

In this context, it was essential to determine whether SM4 directly inhibits BOLA2 expression or if the absence of cysteine as a sulfur source is more significant. We found that (1) adding cysteine to the culture did not significantly affect the sensitivity of BC cells with SM4 to apoptosis induced by doxorubicin, and (2) overproduction of sulfatide does not adversely affect the availability of cysteine. This suggests that sulfur availability is not the decisive factor in determining the sensitivity of cells with high sulfatide content to chemotherapeutic agents. This also suggests a direct involvement of the SM4 in the regulation of BOLA2 expression, especially since we observed a significant reduction in

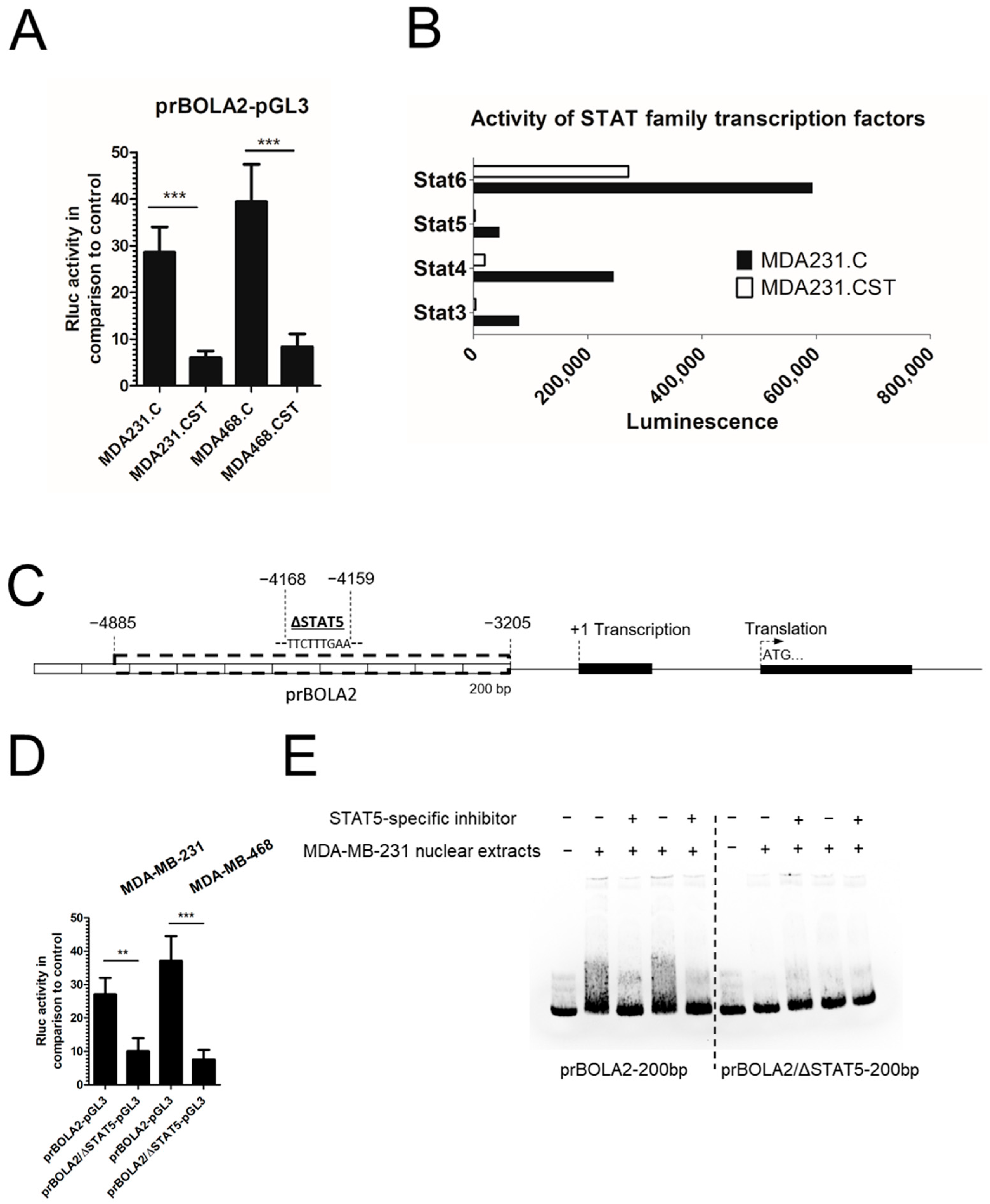

BOLA2 promoter activity in MDA231.CST cells. The cis-regulatory properties of SM4 present on the cell surface are most likely related to the activation or deactivation of signaling pathways, along with the associated regulation of transcription factors interacting directly with the

BOLA2 promoter. Therefore, the activity of 192 different transcription factors was verified, with a particularly interesting decrease in the activity of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) family factors in breast cancer cells with a large amount of SM4. To date, seven members of the STAT family have been identified in mammals [

28]. While some cytokines and growth factors are capable of activating multiple STAT proteins, certain STAT proteins are activated with a high degree of specificity by particular kinases [

29]. The binding site for STAT5 is present in the promoter for the BOLA2 gene, suggesting a potential involvement in its activity. This protein is activated in response to a diverse number of cytokines, growth factors, and hormones. Upon activation, which occurs following ligand-receptor binding, STAT5 proteins undergo dimerization, translocate to the nucleus, and bind to the promoters of specific target genes [

30]. In this proposal, STAT5 was identified as a key regulatory protein driving the overexpression of BOLA2 in breast cancer cells exhibiting a malignant, mesenchymal-like phenotype. This hypothesis was substantiated by functional studies demonstrating the role of STAT5 in the transcriptional upregulation of

BOLA2. Specifically, pharmacological inhibition of STAT5 activity led to a marked reduction in BOLA2 expression, which was associated with increased sensitivity to apoptosis. Although the data presented here (EMSA, STAT5 inhibition, reporter assays) provide indirect but supportive evidence for STAT5-mediated regulation of BOLA2, direct demonstration of STAT5 binding to the BOLA2 promoter remains to be established.

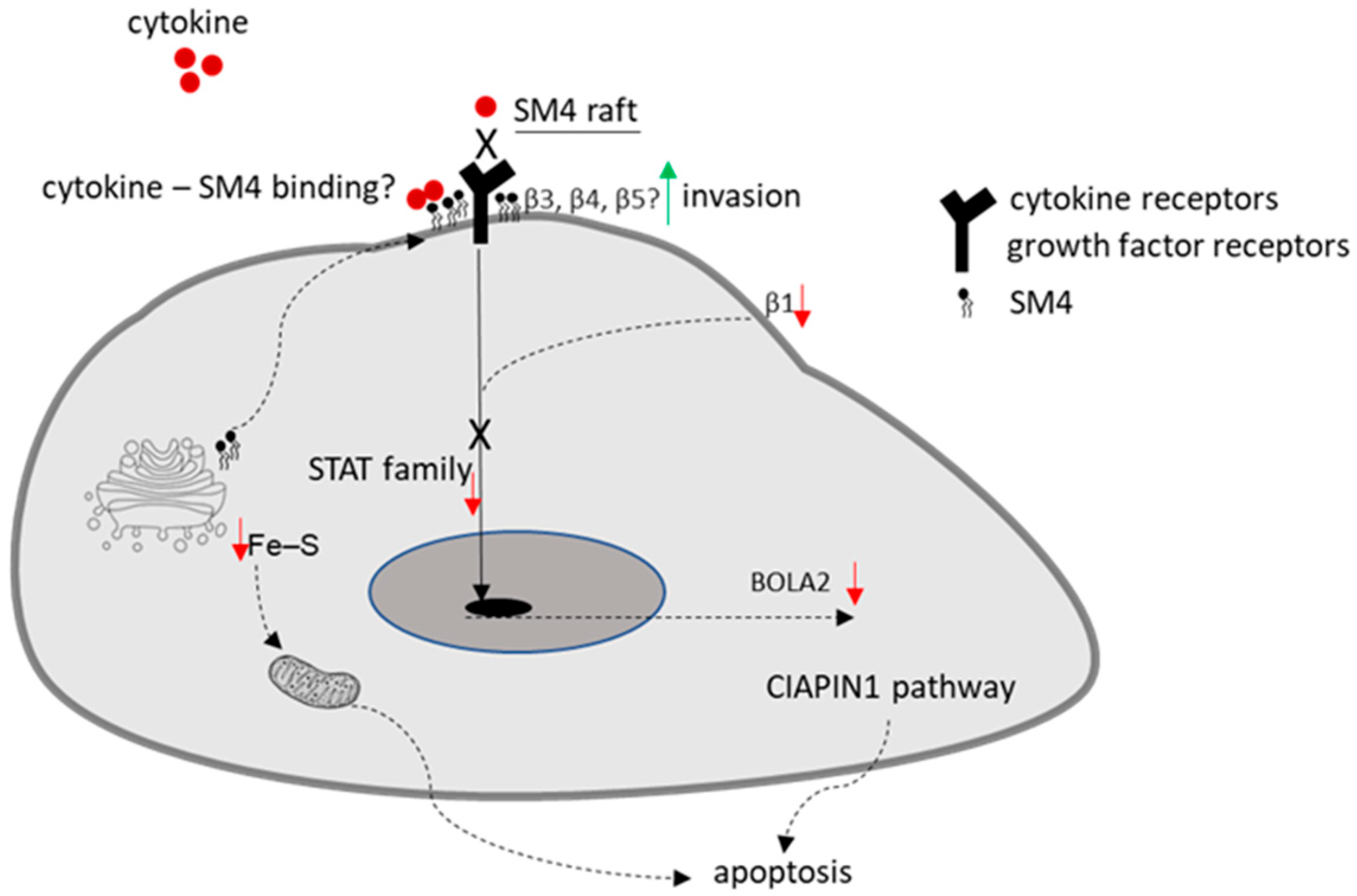

While the cytosolic SM4-dependent signaling pathway has been partially described before, the role of the plasma membrane in this regulation remains unclear. Sulfatides, in contrast to gangliosides, neutral glycolipids, and phospholipids, are bound by various chemokines such as MCP-1/CCL2, IL-8/CXCL8, SDF-1α/CXCL12, MIP-1α/CCL3, and MIP-1β/CCL4 [

31]. Since SM4 is a component of lipid rafts, and chemokine receptors are part of these specific microdomains found in the cell membrane, it is hypothesized that they may modulate chemokine signal transduction. SM4 not only binds chemokines but also can regulate cytokine expression in human lymphocytes and monocytes [

32]. Incubation of these cells, previously activated with phytohemagglutinin with sulfatide, resulted in a decrease in IL-6 production. Conversely, in cells activated with LPS, sulfatide reduced the secretion of IL-1β and IL-10. Subsequent studies have shown that the effect of sulfatide depends on the type of fatty acid in the molecule. The sulfatide containing palmitic acid, abundant in the cells of the pancreatic islets of Langerhans, was discovered to be the most potent inhibitor of cytokine production, including IL-1β, TNF-α, MIP-1α, and IL-8 [

33]. In the brain, SM4 derived from myelin stimulated cytokine production by lymphoid cells with the capacity to initiate an immune response [

34]. There is no experimental evidence for this phenomenon; however, there is a high probability that SM4 present in the cell membrane, in lipid rafts, may compete with cytokine receptors and thus inhibit the activity of cytokine-dependent transcription factors such as members of the STAT family,

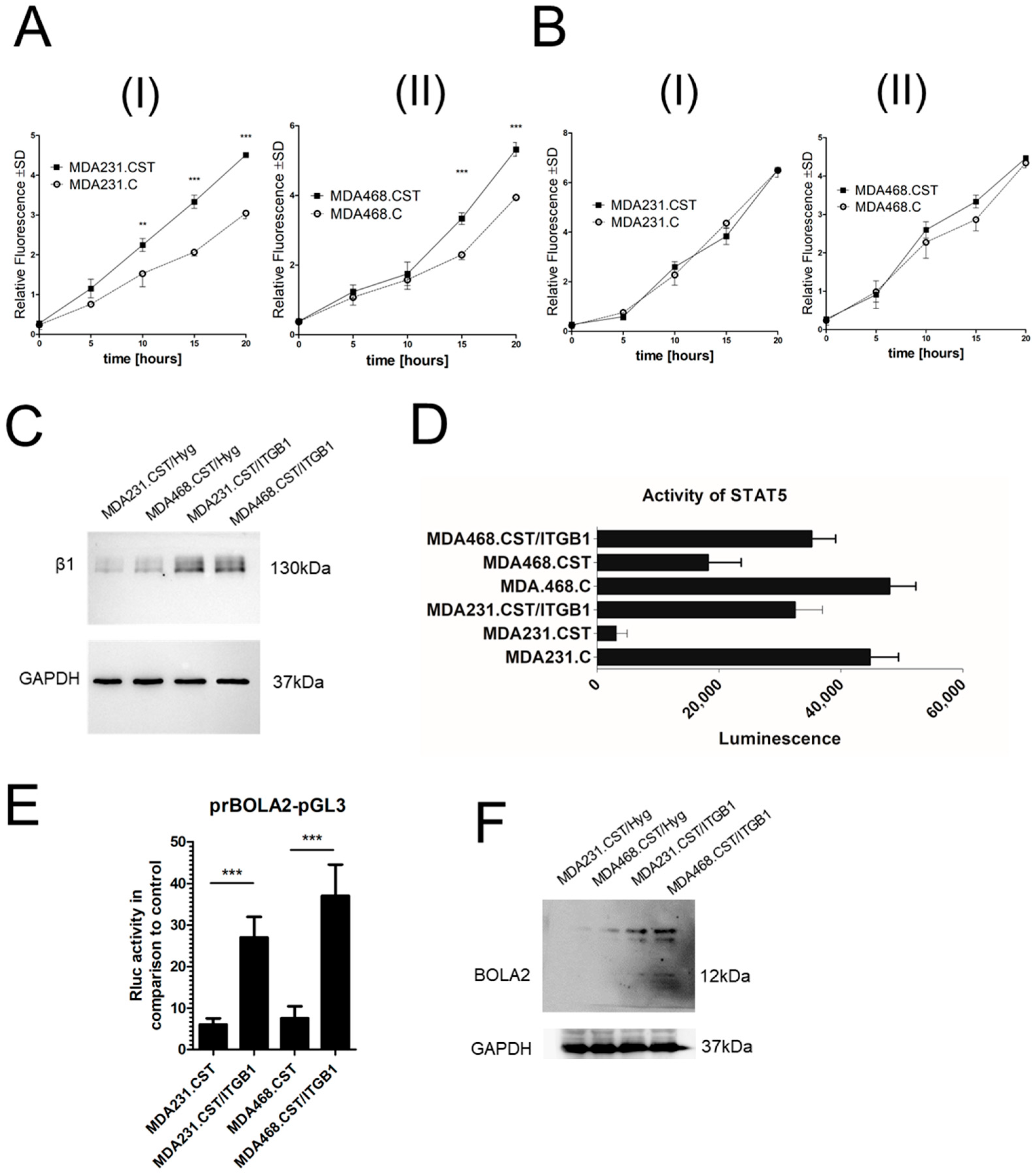

Figure 6. Another regulatory pathway for this TF family involves integrin β1 [

35], and its regulation may be dependent on SM4 since, as previously mentioned, integrin β1 is likely inactive in cell lines with high levels of SM4. The restored expression of integrin β1 resulted in a significant upregulation of both

BOLA2 mRNA and protein levels. However, the underlying mechanism by which sulfatide levels influence BOLA2 regulation through the β1 integrin/STAT5 signaling pathway remains undefined and requires further elucidation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). They were cultured in α-minimum essential medium (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Cat. No. S181H, Biowest, Riverside, MO, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL streptomycin, and 0.1 mg/mL penicillin (complete α-MEM). For the EMSA experiments, MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were treated with the STAT5 inhibitor (catalog no. 573108-M, Merck, Darmstad, Germany), reconstituted in DMSO at a 25 mM stock concentration, with an initial dose of 10 μM (24 h) followed by a 5 μM maintenance dose (48 h).

4.2. Cell Survival Assay

The viability of the cells was measured using an MTT assay. Briefly, 5 × 103 cells per well were seeded in a 96-well plate (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) and incubated with 1 µM doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX) along with increasing concentrations of cysteine (Cat. No. 168149, Merck) for 48 h. Afterward, the medium was discarded, and the cells were incubated with MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL, Merck) for 4 h at 37 °C. Following this, the MTT solution was removed, and 200 µL of DMSO (Chempur, Piekary Śląskie, Poland) was added for 15 min at room temperature. The optical density was then measured at 570 nm.

4.3. Purification of Gangliosides, Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC), and TLC Binding Assay

Gangliosides were purified as described previously [

7,

36]. Glycolipids were extracted from 10

8–10

9 cells using the chloroform–methanol extraction method. HP-TLC was performed on Silica Gel 60 high-performance TLC (HPTLC) plates (Merck). For ganglioside/sulfatide separation, a chloroform: methanol: 0.2% CaCl

2 solvent system (60:40:9,

v/

v/

v) was used. Sulfatide was detected by TLC binding assay as described previously [

8].

4.4. RNA-Sequencing and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Cat. No. 74104, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA purity and concentration were measured with the Nanodrop DS-11 FX (Denovix, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA library preparation and transcriptome sequencing were performed by Novogene (Cambridge, UK). Genes with an adjusted

p-value < 0.05 and |log2 (FoldChange)| > 0 were considered differentially expressed. To validate the RNA-Seq data, the expression of selected candidate genes was assessed with RT-qPCR. Briefly, 1 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo, Oxford, UK) in a 20-μL volume. The relative mRNA levels were measured by qPCR with the EvaGreen dye-based detection system (Cat. no. 31000, Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, using an iQ5 Optical System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). GAPDH served as the internal control. Primer sequences are listed in

Supplementary Table S1.

4.5. SDS-PAGE and Western Blot

RIPA buffer containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was used for total protein isolation. The protein content in the lysate was measured using the Bicinchoninic Acid Kit (Merck). A 4-fold concentrated Laemmli buffer with beta-mercaptoethanol was then added to the samples, which were boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Samples containing 40 μg of protein per well were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred onto 0.45 µm nitrocellulose membranes (Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden) using the Semi-Dry Trans-Blot Turbo system (Bio-Rad). Next, the membrane was blocked with TBS buffer containing 0.5% skimmed milk. After blocking, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: anti-BOLA-2 (Cat. No. A305-890A, Thermo), anti-CST (Cat. No. NBP1-85431, Novus Biologicals), and mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (Cat. No. NB300-221, Novus Biologicals). Following washes, the membranes were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with HRP-conjugated goat polyclonal secondary antibodies targeting rabbit (Cat. No. P0448, Dako) or murine (Cat. No. 115-035-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) immunoglobulins. After additional washing, they were exposed to substrate to visualize HRP complexes (Cat. No. 34094, Thermo). Chemiluminescent detection was performed using ChemiDoc Touch (Bio-Rad). Protein levels were quantified relative to GAPDH expression.

4.6. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

The promoter region of the

BOLA2 gene was cloned by amplification of the genomic sequence by PCR using total DNA purified from MDA-MB-231 cells as a template and forMluI-prBOLA2 and revNheI-prBOLA2 primers (

Table S1) as follows: 35 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 20 s), annealing (55 °C for 20 s) and extension (72 °C for 1 min). The generated

BOLA2 promoter was cloned into the corresponding sites of the pGL3 Basic Vector (Cat. No. E1751, Promega) and named: pGL3-BOLA2/LUC.

To assess promoter activity, cells were processed using Promega’s Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System. In brief, cells were cultivated to approximately 70% confluence in 6-well plates (Nunc) and then co-transfected with a pGL3 promoter-containing Firefly luciferase reporter vector (2 μg) and a control Renilla luciferase-expressing pRL-TK vector (2 μg) with polyethylenimine (PEI) reagent. Following a 48 h incubation period, the cells were lysed and then assayed for luciferase activity. Firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase signals were sequentially measured on a luminescence microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). The signal integration time was set to one second per well. Mock-transfected cells and empty wells were included to evaluate the background luminescence. The relative luciferase activity was then normalized to the Renilla luciferase activity. Each experiment was performed in three independent biological replicates.

4.7. Nuclear Extracts and Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

The purification of nuclear proteins was carried out using a commercially available NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Cat. No.78833, Thermo), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity of non-nuclear and nuclear fractions was subsequently determined using specific protein markers, namely GAPDH and histone H3, respectively,

Figure S4. Biotin end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides were then generated using PCR, using biotinylated primers at the 5′ end (

Table S1), followed by purification of the obtained products. The binding reactions (including 5 μg of nuclear extract protein, 1 μg of poly (dI-dC), 2 nM of biotin-labeled DNA, and 10 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl

2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.05% Nonidet P-40, and 2.5% glycerol) were carried out at 23 °C for 20 min. To separate bound oligonucleotides from free probe, the samples were electrophoresed on a 6% Tris-borate-EDTA gel at 100 V for 1 h in a 100 mM Tris-borate-EDTA buffer and transferred to a nylon membrane. The biotin-labeled DNA was detected with a LightShift chemiluminescent electrophoretic mobility shift assay kit (Cat. No. 20148, Thermo).

4.8. Apoptotic Assay

The cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL. The following day, the cells were treated with DOX for 48 h. Apoptosis was measured by staining cells with Annexin V conjugated with red-laser-excited allophycocyanin (APC) and SYTOX Green using the Dead Cell Apoptosis Kit (Cat. No. V13242, Thermo, Oxford, UK). Fluorescence was measured on a BD FACSLyric (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and data were analyzed using the BD FACSuite™ Software v1.5.0.925 (Becton-Dickinson). The percentage of Annexin V APC-positive cells corresponded to cells in early apoptosis, whereas Annexin V APC and SYTOX Green-positive cells corresponded to cells in late apoptosis.

4.9. Lipid Peroxidation Assay

The cells (106) were seeded in 6-well plates (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA). The following day, lipid peroxidation was determined using a lipid peroxidation assay kit (ab243377, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) in cells treated with 50 µM H2O2 or 250 µM H2O2 (30 min). In brief, a ratiometric lipid peroxidation sensor was added to the cells and incubated for 30 min. After 3 washing steps with HHBS buffer, fluorescence of cells was measured on a BD FACS Lyric (Becton-Dickinson) through green and red channels, and data were quantified as the FITC/APC signal ratio, using the BD FACSuite™ Software (Becton-Dickinson). Lipid peroxidation is represented with increasing in green fluorescence. Data are the result of the quantification of 3 independent cell preparations.

4.10. Transcription Factor Activation Profiling Arrays

Analysis of transcription factors was performed using Combo TF Activation Profiling Plate. Nuclear extracts were prepared from 5 × 105 cells using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Thermo). A total of 10 μg of the resulting nuclear extract was used to form biotin-labeled protein–DNA complexes. Following elution, the denatured probes were hybridized overnight at 42 °C on a precoated plate containing immobilized target oligonucleotides. After washing, biotin-labeled probes were detected using streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (streptavidin-HRP). Luminescence was measured using a Tecan Spark multimode microplate reader controlled by SparkControl Software v3.2, with an integration time of 1 s. Signal intensity was recorded as relative light units (RLUs) after 10 min.