New Insights into the Molecular Actions of Grosheimin, Costunolide, and α- and β-Cyclocostunolide on Primary Cilia Structure and Hedgehog Signaling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Sesquiterpene Lactones Modulate Primary Cilium Formation in Human Fibroblasts

2.2. Sesquiterpene Lactones Differentially Impair Hedgehog Signaling

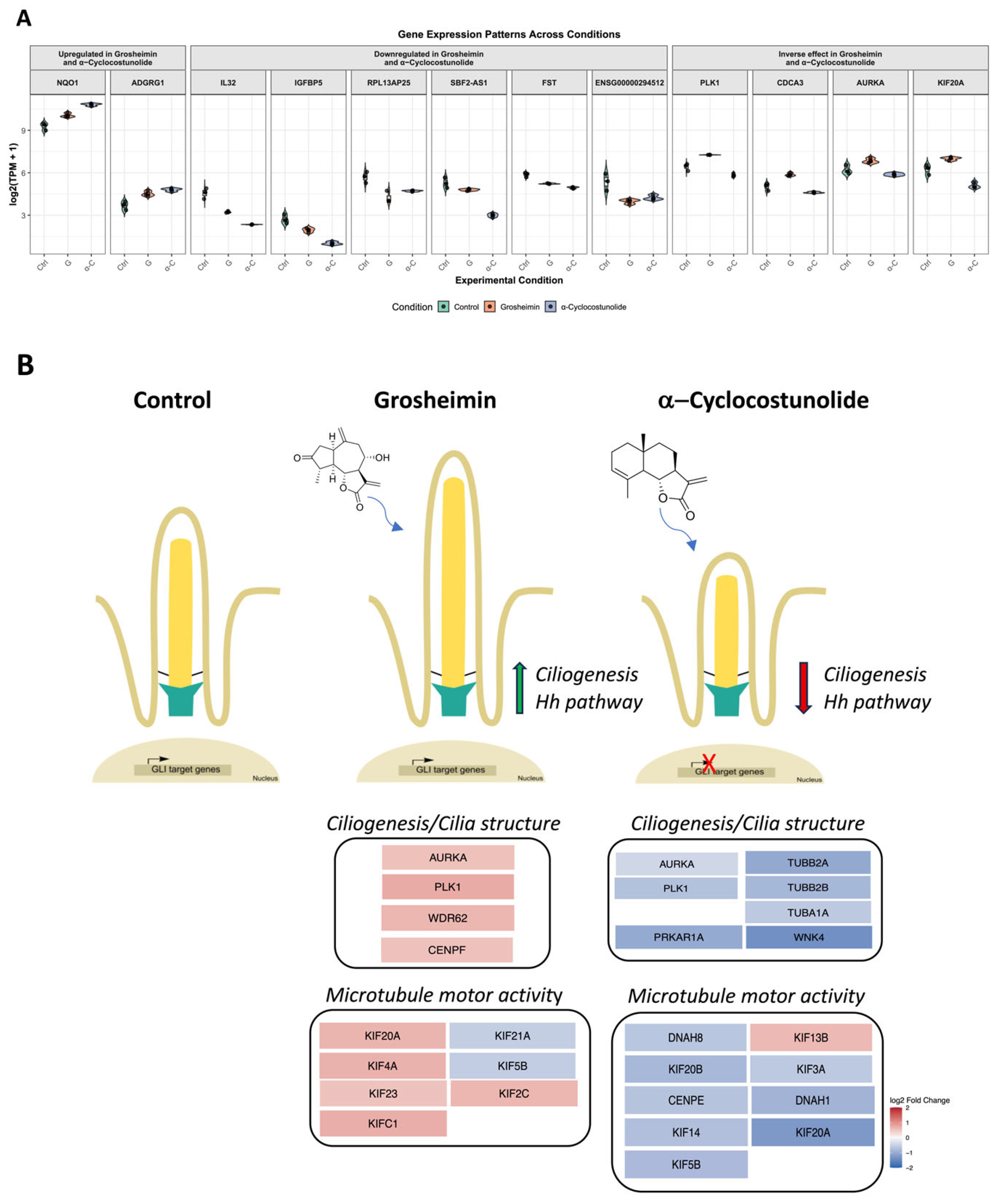

2.3. Transcriptomic Analysis of Grosheimin and a-Cyclocostunolide

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Extraction, Isolation, and Semi-Synthesis of Sesquiterpene Lactones Compounds

4.2. Cell Culture Conditions and Biological Assays

4.3. Hedgehog Pathway Activation

4.4. Immunofluorescence (IF)

4.5. Microscopy

4.6. RNA Preparation and Sequencing

4.7. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis

4.8. RNA-Seq Analysis

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PC | Primary Cilium |

| SL | Sesquiterpene Lactones |

| Hh | Hedgehog |

| C | Costunolide |

| α-C | α-Cyclocostunolide |

| β-C | β-Cyclocostunolide |

| SMO | Smoothened |

| IFT | Intraflagellar Transport |

| RPE | Retinal Pigment Epithelial |

| RHDF | Human primary fibroblasts |

References

- Mill, P.; Christensen, S.T.; Pedersen, L.B. Primary cilia as dynamic and diverse signalling hubs in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 421–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslow, D.K.; Holland, A.J. Mechanism and Regulation of Centriole and Cilium Biogenesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 691–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanamaru, T.; Neuner, A.; Kurtulmus, B.; Pereira, G. Balancing the length of the distal tip by septins is key for stability and signalling function of primary cilia. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e108843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May-Simera, H.L.; Wan, Q.; Jha, B.S.; Hartford, J.; Khristov, V.; Dejene, R.; Chang, J.; Patnaik, S.; Lu, Q.; Banerjee, P.; et al. Primary Cilium-Mediated Retinal Pigment Epithelium Maturation Is Disrupted in Ciliopathy Patient Cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheway, G.; Nazlamova, L.; Hancock, J.T. Signaling through the Primary Cilium. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, T.; Larsen, L.J.; Pedersen, L.B.; Christensen, S.T.; Moller, L.B. TSC1 and TSC2 regulate cilia length and canonical Hedgehog signaling via different mechanisms. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 2663–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbit, K.C.; Aanstad, P.; Singla, V.; Norman, A.R.; Stainier, D.Y.; Reiter, J.F. Vertebrate Smoothened functions at the primary cilium. Nature 2005, 437, 1018–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasai, N.; Toriyama, M.; Kondo, T. Hedgehog Signal and Genetic Disorders. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, F.; Benzing, T.; Katsanis, N. Ciliopathies. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1533–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, R.; Tanos, B. Primary cilia and cancer: A tale of many faces. Oncogene 2025, 44, 1551–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassounah, N.B.; Nunez, M.; Fordyce, C.; Roe, D.; Nagle, R.; Bunch, T.; McDermott, K.M. Inhibition of Ciliogenesis Promotes Hedgehog Signaling, Tumorigenesis, and Metastasis in Breast Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Kiseleva, A.A.; Golemis, E.A. Ciliary signalling in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, N.; Alaseem, A.M.; Babu, A.M.; Alasiri, G.; Singh, T.G.; Tyagi, Y.; Sharma, G. Unveiling the anticancer potential of medicinal plants: Metabolomics and analytical tools in phytomedicine. Mol. Divers. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheikh, I.A.; El-Baba, C.; Youssef, A.; Saliba, N.A.; Ghantous, A.; Darwiche, N. Lessons learned from the discovery and development of the sesquiterpene lactones in cancer therapy and prevention. Expert. Opin. Drug Discov. 2022, 17, 1377–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejias, F.J.R.; Duran, A.G.; Zorrilla, J.G.; Varela, R.M.; Molinillo, J.M.G.; Valdivia, M.M.; Macias, F.A. Acyl Derivatives of Eudesmanolides to Boost their Bioactivity: An Explanation of Behavior in the Cell Membrane Using a Molecular Dynamics Approach. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macias, F.A.; Fernandez, A.; Varela, R.M.; Molinillo, J.M.; Torres, A.; Alves, P.L. Sesquiterpene lactones as allelochemicals. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coricello, A.; Adams, J.D.; Lien, E.J.; Nguyen, C.; Perri, F.; Williams, T.J.; Aiello, F. A Walk in Nature: Sesquiterpene Lactones as Multi-Target Agents Involved in Inflammatory Pathways. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 1501–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Pineda, M.; Coto-Cid, J.M.; Romero, M.; Zorrilla, J.G.; Chinchilla, N.; Medina-Calzada, Z.; Varela, R.M.; Juarez-Soto, A.; Macias, F.A.; Reales, E. Effects of Sesquiterpene Lactones on Primary Cilia Formation (Ciliogenesis). Toxins 2023, 15, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cala, A.; Zorrilla, J.G.; Rial, C.; Molinillo, J.M.G.; Varela, R.M.; Macias, F.A. Easy Access to Alkoxy, Amino, Carbamoyl, Hydroxy, and Thiol Derivatives of Sesquiterpene Lactones and Evaluation of Their Bioactivity on Parasitic Weeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 10764–10773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, A.M.; Giles, R.H.; Srivastava, S.; Eley, L.; Whitehead, J.; Danilenko, M.; Raman, S.; Slaats, G.G.; Colville, J.G.; Ajzenberg, H.; et al. Murine Joubert syndrome reveals Hedgehog signaling defects as a potential therapeutic target for nephronophthisis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9893–9898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nachury, M.V. How do cilia organize signalling cascades? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, A.; Guijarro, A.; Bravo, B.; Hernandez, J.; Murillas, R.; Gallego, M.I.; Ballester, S. Hedgehog Signalling Modulates Immune Response and Protects against Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, T.M.; Sakib, S.; Webster, D.; Carlson, D.F.; Van der Hoorn, F.; Dobrinski, I. A reduction of primary cilia but not hedgehog signaling disrupts morphogenesis in testicular organoids. Cell Tissue Res. 2020, 380, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spann, A.L.; Yuan, K.; Goliwas, K.F.; Steg, A.D.; Kaushik, D.D.; Kwon, Y.J.; Frost, A.R. The presence of primary cilia in cancer cells does not predict responsiveness to modulation of smoothened activity. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 47, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Guo, S.; Liao, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Tang, F.; He, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, Q. Resveratrol Activated Sonic Hedgehog Signaling to Enhance Viability of NIH3T3 Cells in Vitro via Regulation of Sirt1. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 50, 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, R.; Milenkovic, L.; Corcoran, R.B.; Scott, M.P. Hedgehog signal transduction by Smoothened: Pharmacologic evidence for a 2-step activation process. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3196–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, Y. NAD(P)H: Quinone oxidoreductase 1 and its potential protective role in cardiovascular diseases and related conditions. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2012, 12, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, K.; Hashimoto-Hachiya, A.; Takahara, M.; Tsuji, G.; Nakahara, T.; Furue, M. Cynaropicrin attenuates UVB-induced oxidative stress via the AhR-Nrf2-Nqo1 pathway. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 234, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, J.F.; Leroux, M.R. Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Soni, R.K.; Uryu, K.; Tsou, M.F. The conversion of centrioles to centrosomes: Essential coupling of duplication with segregation. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 193, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neganova, M.E.; Afanas’eva, S.V.; Klochkov, S.G.; Shevtsova, E.F. Mechanisms of antioxidant effect of natural sesquiterpene lactone and alkaloid derivatives. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2012, 152, 720–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, M.F.A.; Hattab, D.; Bakhtiar, A. Anticancer potential of synthetic costunolide and dehydrocostus lactone derivatives: A systematic review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 291, 117648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, B.H.; Koh, B.; Ndubuisi, M.I.; Elofsson, M.; Crews, C.M. The anti-inflammatory natural product parthenolide from the medicinal herb Feverfew directly binds to and inhibits IkappaB kinase. Chem. Biol. 2001, 8, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, K.; Pogoda, K.; Nandi, S.; Mathieu, S.; Kasri, A.; Klein, E.; Radvanyi, F.; Goud, B.; Janmey, P.A.; Manneville, J.B. Role of a Kinesin Motor in Cancer Cell Mechanics. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 7691–7702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Kumar, M.; Saifi, S.; Rawat, S.; Ethayathulla, A.S.; Kaur, P. A comprehensive review on role of Aurora kinase inhibitors (AKIs) in cancer therapeutics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 265 Pt 2, 130913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochegger, H.; Hegarat, N.; Pereira-Leal, J.B. Aurora at the pole and equator: Overlapping functions of Aurora kinases in the mitotic spindle. Open Biol. 2013, 3, 120185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combes, G.; Alharbi, I.; Braga, L.G.; Elowe, S. Playing polo during mitosis: PLK1 takes the lead. Oncogene 2017, 36, 4819–4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Khan, Z.; Westlake, C.J. Ciliogenesis membrane dynamics and organization. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 133, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejskova, P.; Reilly, M.L.; Bino, L.; Bernatik, O.; Dolanska, L.; Ganji, R.S.; Zdrahal, Z.; Benmerah, A.; Cajanek, L. KIF14 controls ciliogenesis via regulation of Aurora A and is important for Hedgehog signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 219, e201904107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertii, A.; Bright, A.; Delaval, B.; Hehnly, H.; Doxsey, S. New frontiers: Discovering cilia-independent functions of cilia proteins. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 1275–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglietta, A.; Bozzo, F.; Gabriel, L.; Bocca, C. Microtubule-interfering activity of parthenolide. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2004, 149, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Jiao, J.; Xu, L.; Yan, Y.; Wu, Q.; Tong, X.; Yan, H. Integrated Analysis of Transcriptome Data Revealed AURKA and KIF20A as Critical Genes in Medulloblastoma Progression. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 875521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauring, M.C.; Zhu, T.; Luo, W.; Wu, W.; Yu, F.; Toomre, D. New software for automated cilia detection in cells (ACDC). Cilia 2019, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murillo-Pineda, M.; Martínez-Miralles, J.; Medina-Calzada, Z.; Varela, R.M.; Macías, F.A.; Chinchilla, N.; Juárez-Soto, Á.; Santpere, G.; Reales, E. New Insights into the Molecular Actions of Grosheimin, Costunolide, and α- and β-Cyclocostunolide on Primary Cilia Structure and Hedgehog Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311754

Murillo-Pineda M, Martínez-Miralles J, Medina-Calzada Z, Varela RM, Macías FA, Chinchilla N, Juárez-Soto Á, Santpere G, Reales E. New Insights into the Molecular Actions of Grosheimin, Costunolide, and α- and β-Cyclocostunolide on Primary Cilia Structure and Hedgehog Signaling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311754

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurillo-Pineda, Marina, Joel Martínez-Miralles, Zahara Medina-Calzada, Rosa María Varela, Francisco Antonio Macías, Nuria Chinchilla, Álvaro Juárez-Soto, Gabriel Santpere, and Elena Reales. 2025. "New Insights into the Molecular Actions of Grosheimin, Costunolide, and α- and β-Cyclocostunolide on Primary Cilia Structure and Hedgehog Signaling" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311754

APA StyleMurillo-Pineda, M., Martínez-Miralles, J., Medina-Calzada, Z., Varela, R. M., Macías, F. A., Chinchilla, N., Juárez-Soto, Á., Santpere, G., & Reales, E. (2025). New Insights into the Molecular Actions of Grosheimin, Costunolide, and α- and β-Cyclocostunolide on Primary Cilia Structure and Hedgehog Signaling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311754