Temperature Perception Regulates Seed Germination in Solanum nigrum via Phytohormone Signaling Pathways

Abstract

1. Introduction

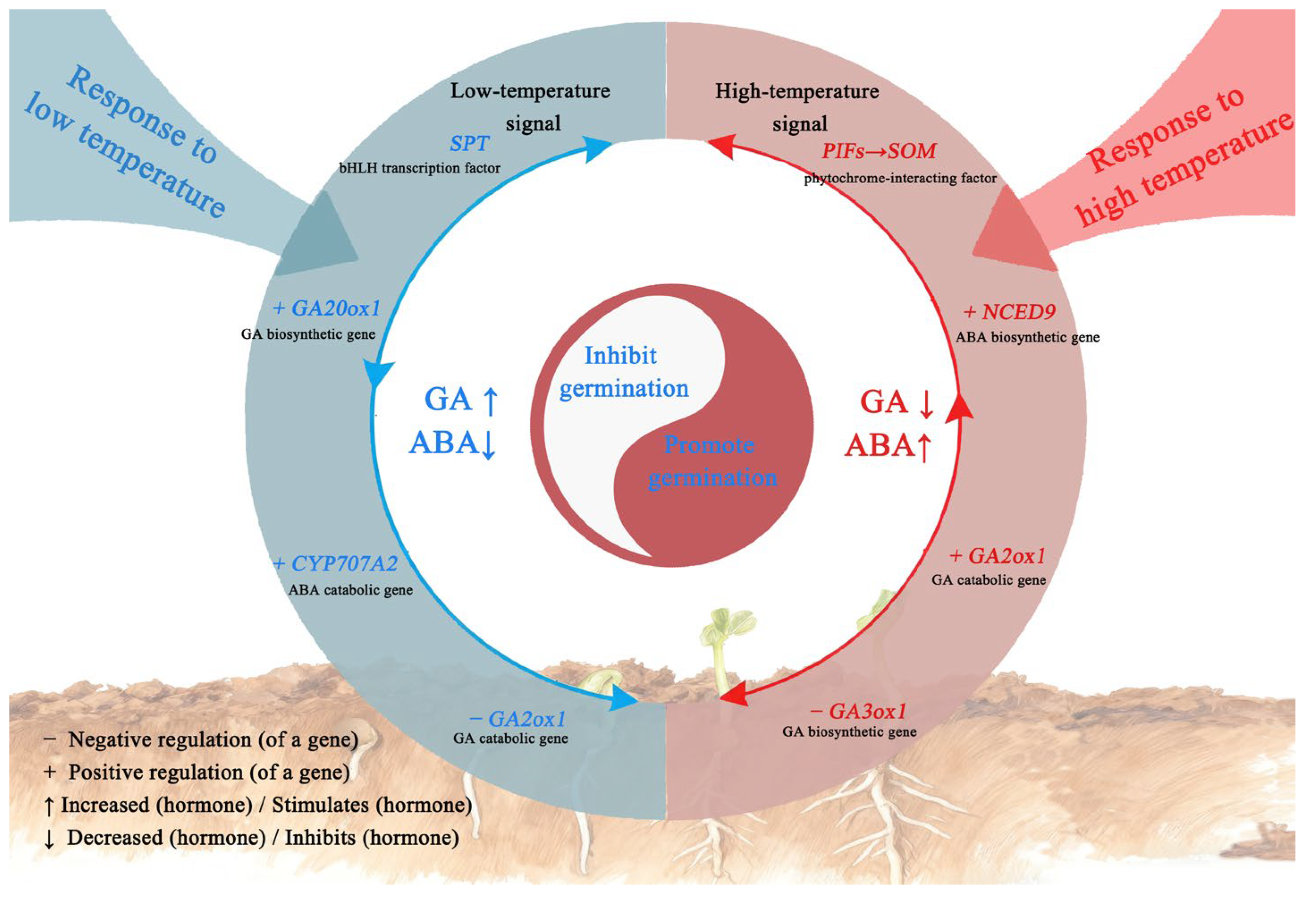

2. Results

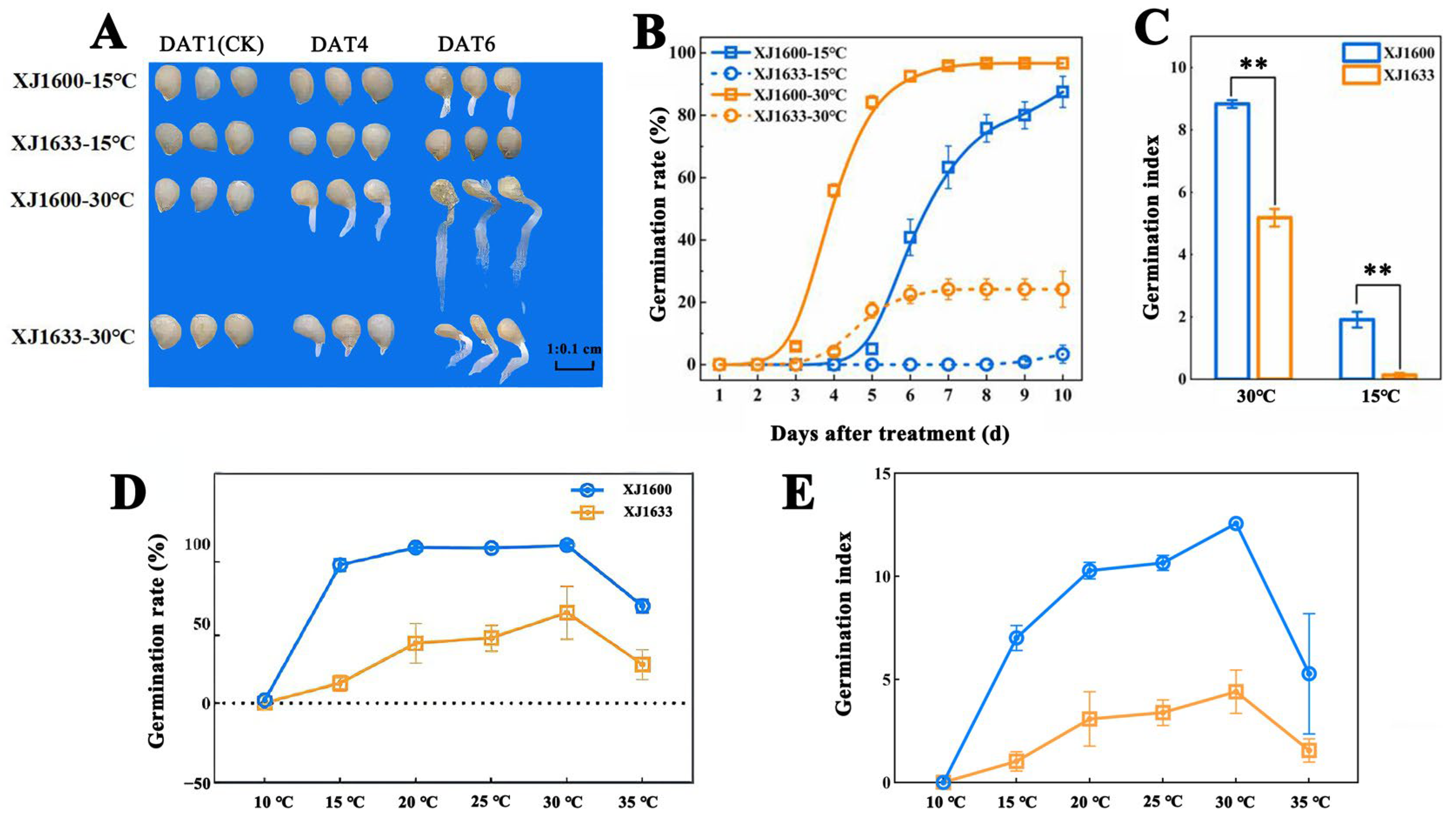

2.1. Germination Difference

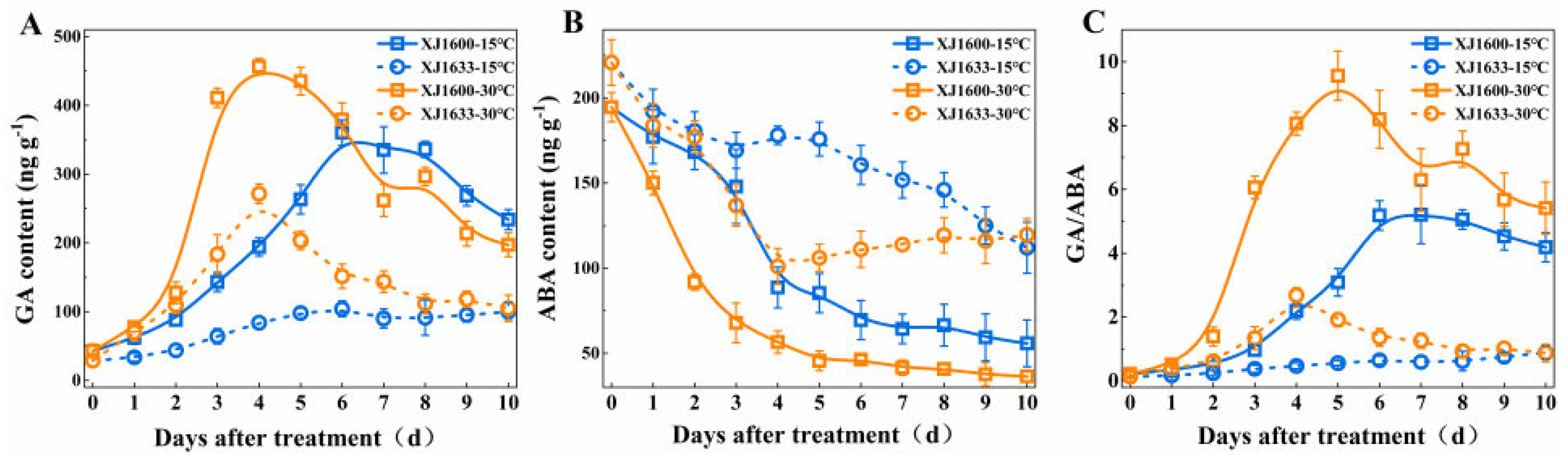

2.2. Seed GA and ABA Content

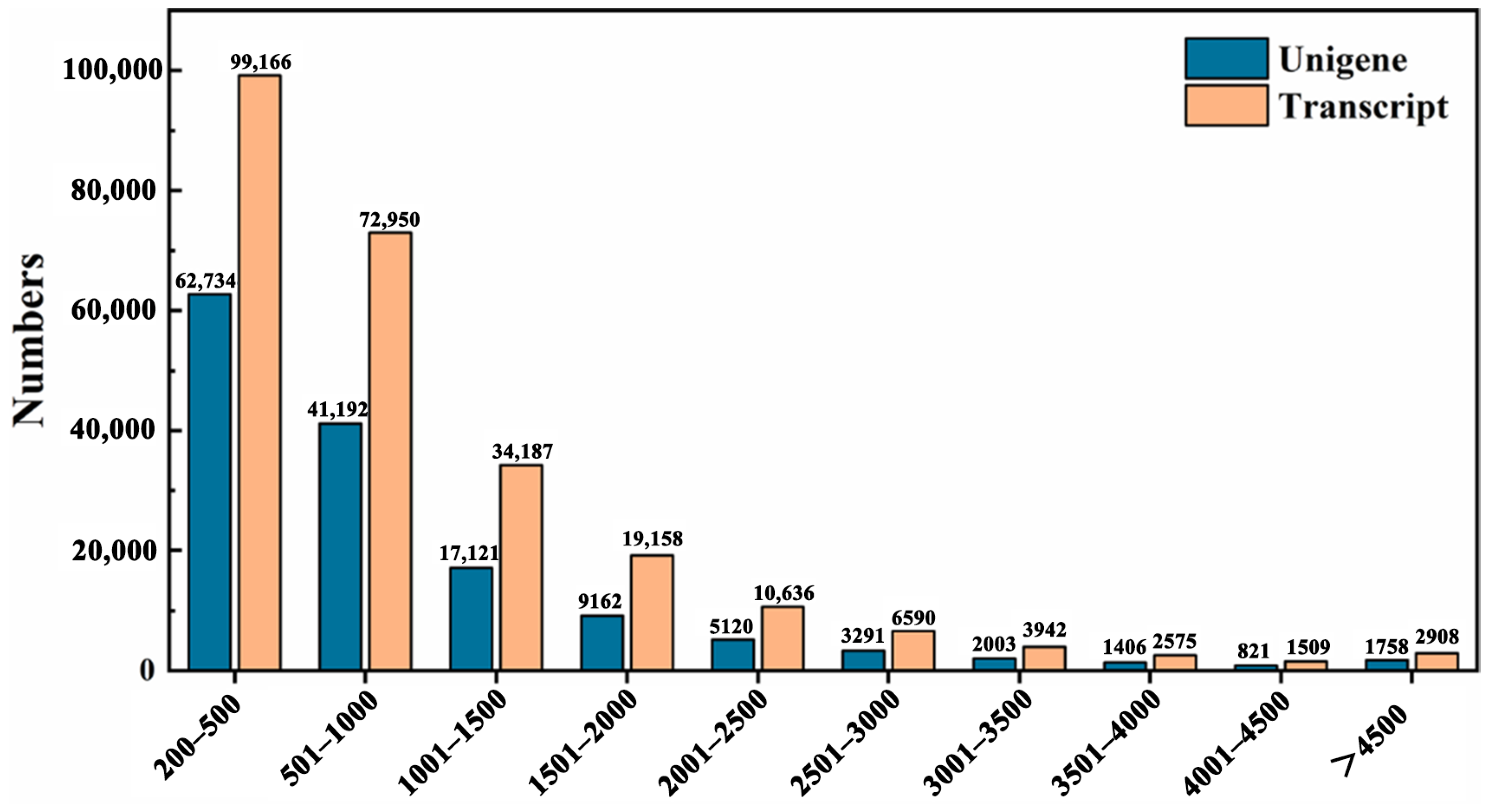

2.3. Sequencing Quality and Reads Assembly

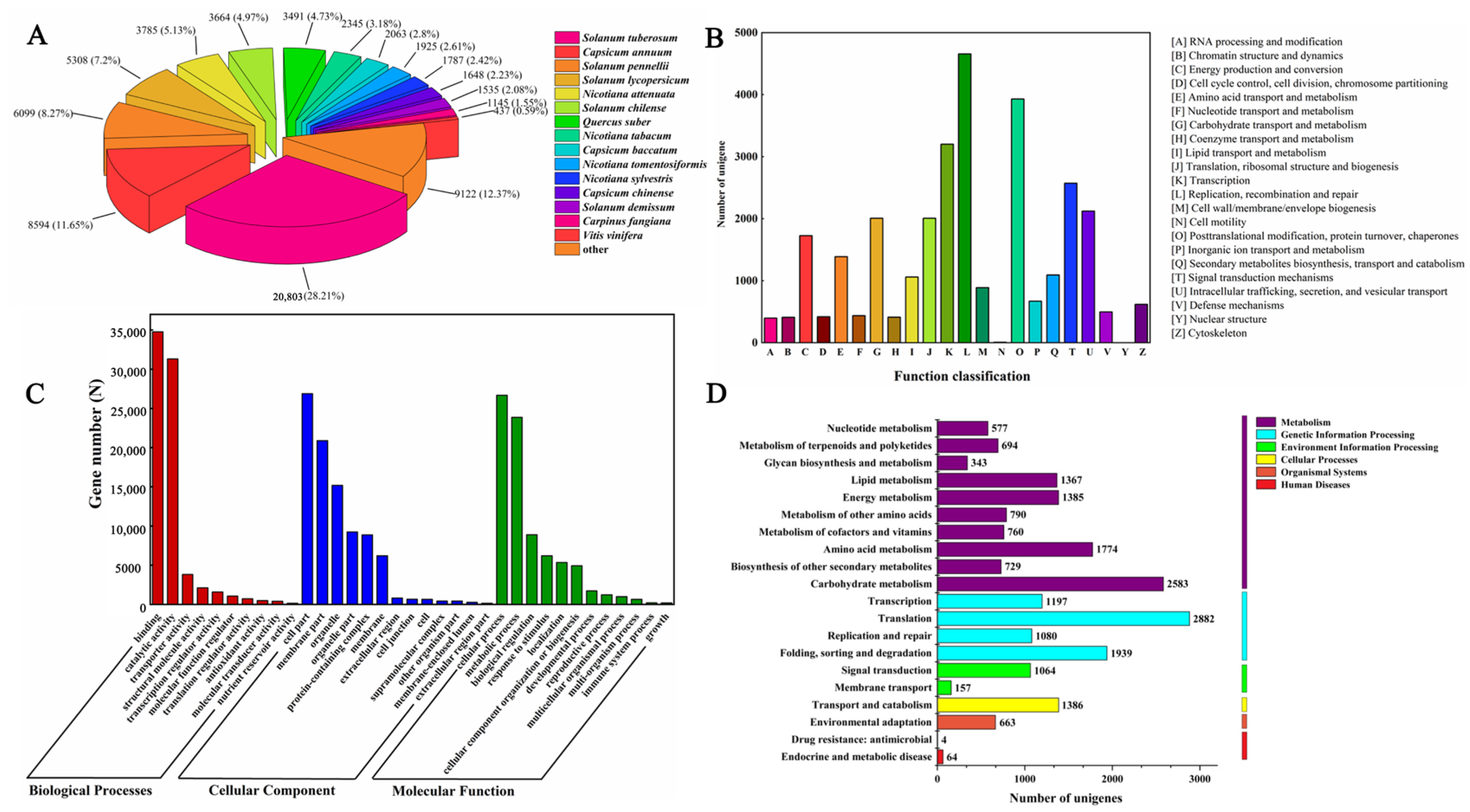

2.4. Functional Annotations

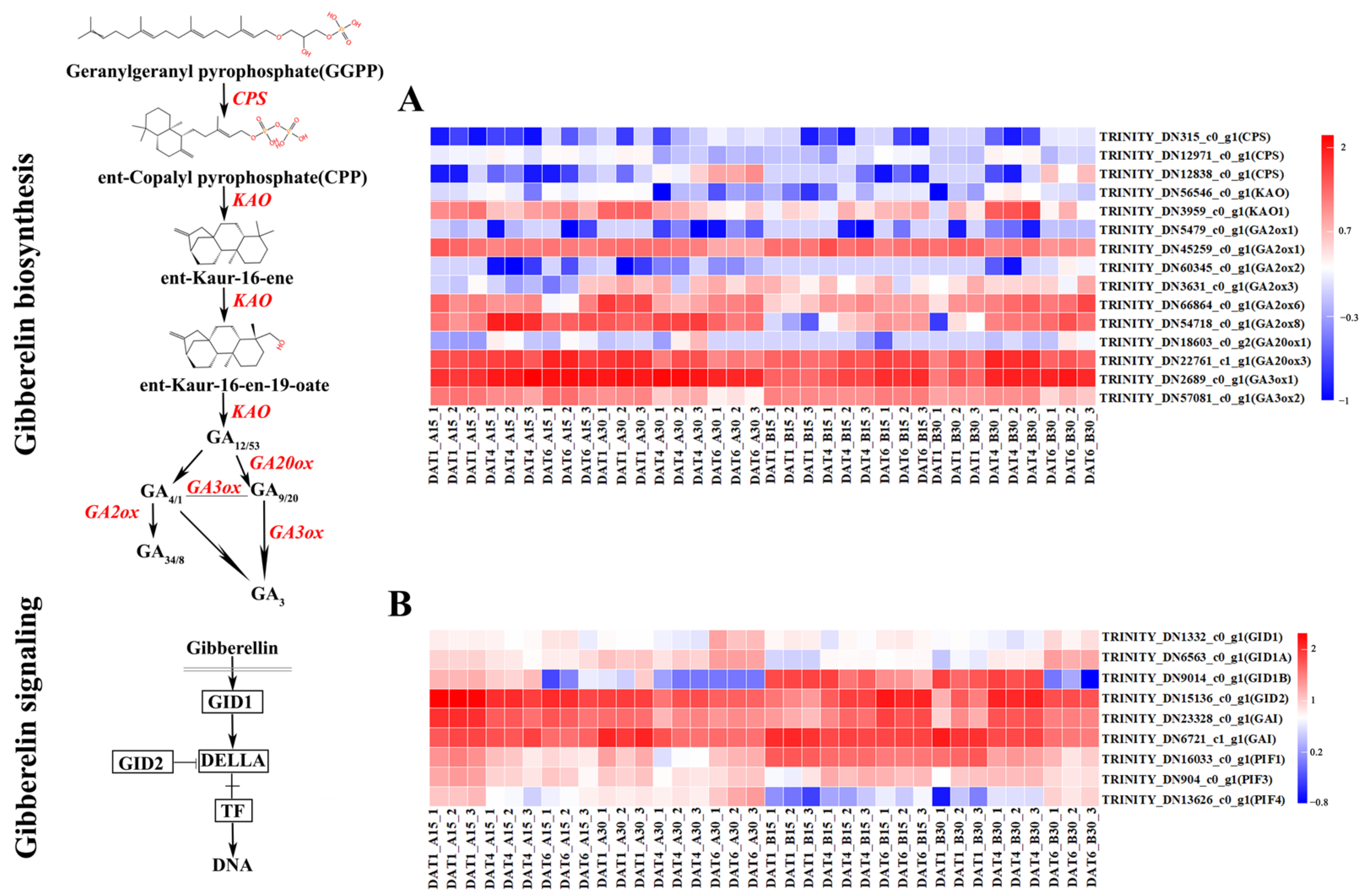

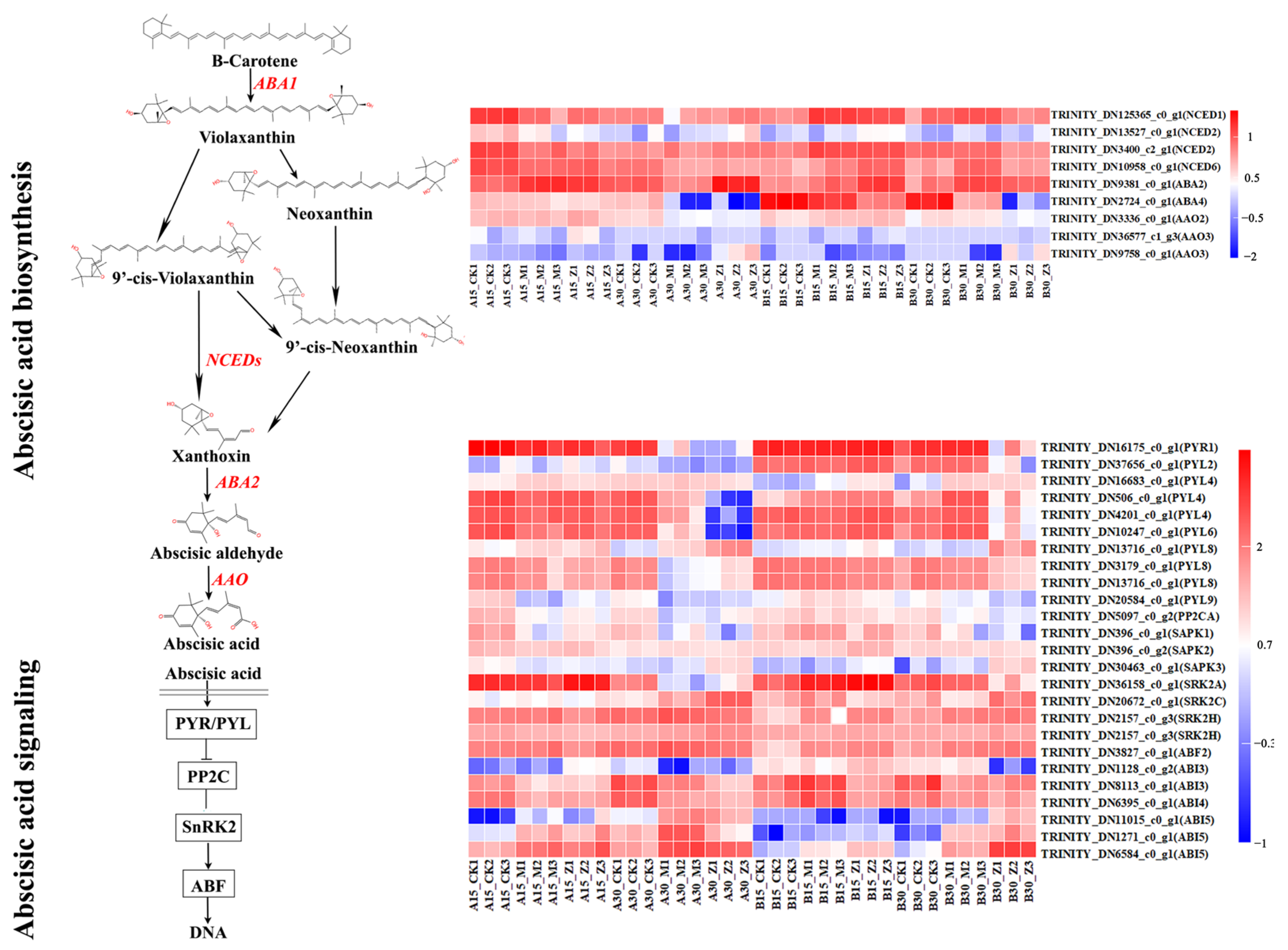

2.5. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

2.6. GO and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

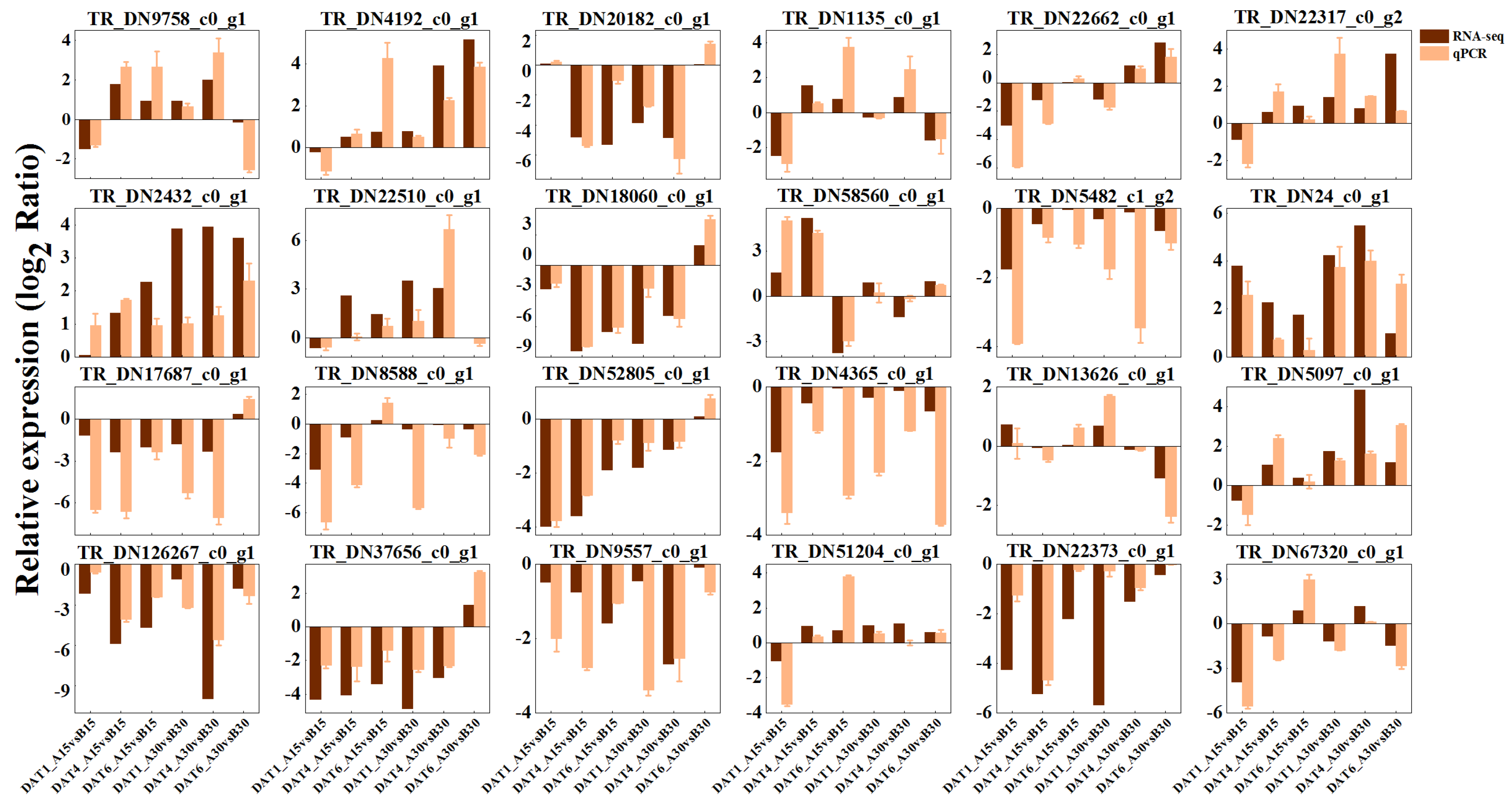

2.7. Candidate Gene Selection and Validation

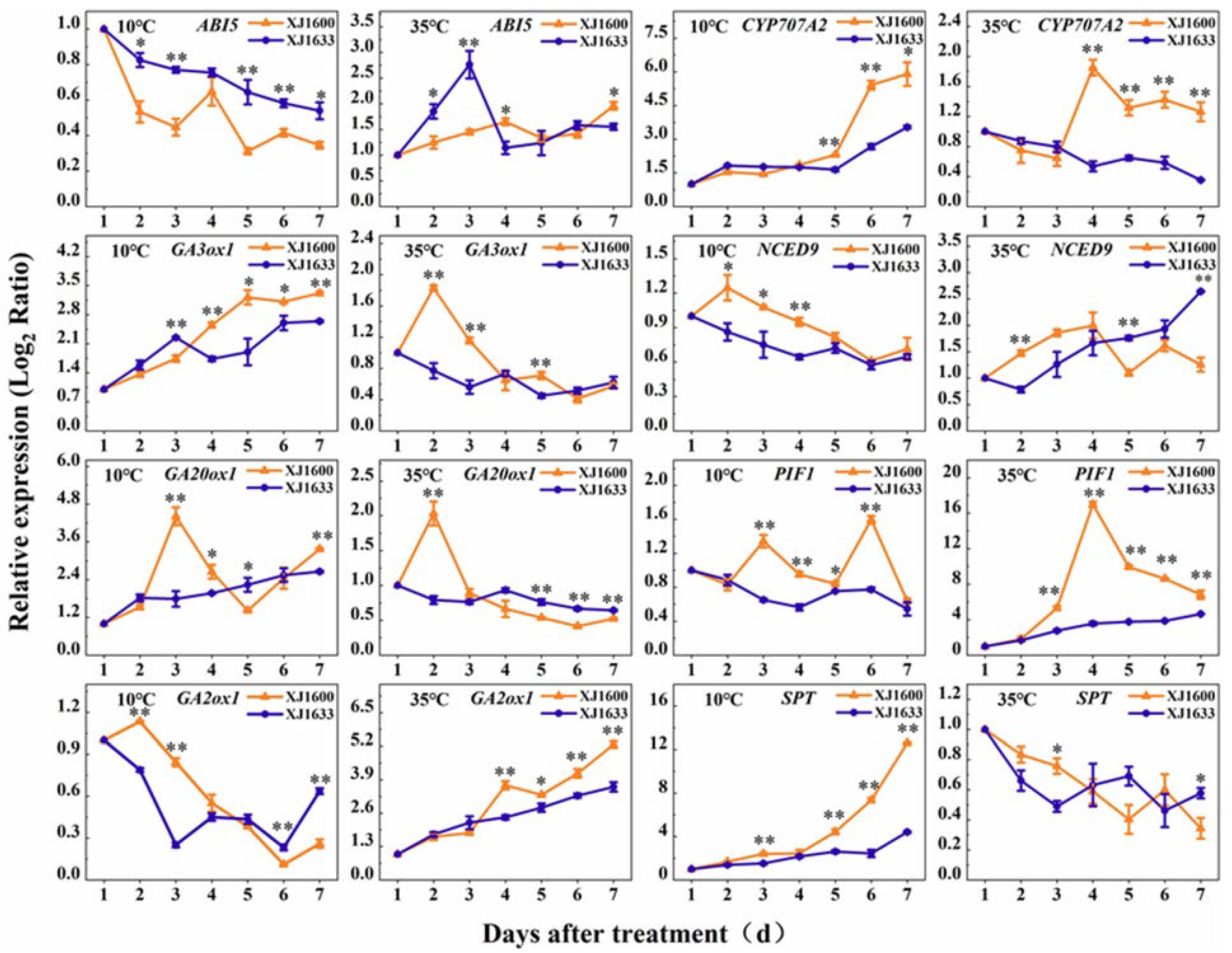

2.8. Dynamics of Temperature-Responsive Gene Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Design

4.2. Plant Growth Conditions

4.3. Seed Germination

4.4. Determination of GA and ABA Content

4.5. Transcriptome Sequencing

4.6. GO Enrichment Analysis

4.7. RT–qPCR Analysis

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kremer, E.; Kropff, M.J. Growth and reproduction of triazine-susceptible and -resistant Solanum nigrum in a maize crop. Weed Res. 1998, 38, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Olvera, S.M.; Sandoval-Villa, M. Uses, Botanical Characteristics, and Phenological Development of Slender Nightshade (Solanum nigrescens Mart. and Gal.). Plants 2023, 12, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suthar, A.C.; Naik, V.R.; Mulani, R.M. Seed and Seed Germination in Solanum nigrum Linn. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2009, 5, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, K.; Liu, X.D.; Xie, Q.; He, Z.H. Two Faces of One Seed: Hormonal Regulation of Dormancy and Germination. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfield, S. Seed dormancy and germination. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Keblawy, A.; Soliman, S.; Al-Khoury, R.; Ghauri, A.; Al Rammah, H.; Hussain, S.E.; Rashid, S.; Manzoor, Z. Effect of maturation conditions on light and temperature requirements during seed germination of Citrullus colocynthis from the Arabian Desert. Plant Biol. 2019, 21, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Yoshida, H.; Chu, C.C.; Matsuoka, M.; Sun, J. Seed dormancy and germination in rice: Molecular regulatory mechanisms and breeding. Mol. Plant 2025, 18, 960–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klupczyńska, E.A.; Pawłowski, T.A. Regulation of Seed Dormancy and Germination Mechanisms in a Changing Environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.C.; Xue, J.; Gu, T.; Wang, H.C.; Chauhan, B.S. Effect of environmental factors on seed germination and seedling emergence of weedy rice (Oryza sativa f. spontanea) in China. Weed Sci. 2024, 72, 754–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfield, S.; MacGregor, D.R. Effects of environmental variation during seed production on seed dormancy and germination. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Wen, B. Seed germination response to high temperature and water stress in three invasive Asteraceae weeds from Xishuangbanna, SW China. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.S.; Ali, H.H.; Florentine, S. Seed germination ecology of Bidens pilosa and its implications for weed management. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Pascual, E.; Carta, A.; Mondoni, A.; Cavieres, L.A.; Rosbakh, S.; Venn, S.; Satyanti, A.; Guja, L.; Briceño, V.F.; Vandelook, F. The seed germination spectrum of alpine plants: A global meta-analysis. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 3573–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, C.P.; Simoes, I.M.; Fagundes, D.P.; Costa, J.S.; Cade, E.S.; de Moraes, E.B.; de Almeida, M.R.; de Assis, J.; Schmildt, E.R.; Pereira, W.V.S.; et al. Thermal shock at a high temperature for a short period increases the germination success of the chestnut tree Lecythis pisonis Cambess. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.H.; Sami, A.; Xu, Q.Q.; Wu, L.L.; Zheng, W.Y.; Chen, Z.P.; Jin, X.Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y. Effects of seed priming treatments on the germination and development of two rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) varieties under the co-influence of low temperature and drought. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masondo, N.A.; Kulkarni, M.G.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Influence of biostimulants-seed-priming on Ceratotheca triloba germination and seedling growth under low temperatures, low osmotic potential and salinity stress. Ecotox Environ. Safe 2018, 147, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.J.; Xu, H.H.; Wang, W.Q.; Li, N.; Wang, W.P.; Møller, I.M.; Song, S.Q. A proteomic analysis of rice seed germination as affected by high temperature and ABA treatment. Physiol. Plant 2015, 154, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.Q.; Huang, H.J.; Huang, Z.F.; Guo, D.J.; Saeed, M.F.; Jiang, C.L.; Chen, Z.X.; Wei, S.H. Germination Response of Black Nightshade (Solanum nigrum) to Temperature and the Establishment of a Thermal Time Model. Weed Sci. 2021, 69, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balah, M.A.; Hassany, W.M.; Mousa, E.E.-d.A. Response of invasive Solanum elaeagnifolium Cav. seed germination and growth to different conditions and environmental factors. Biologia 2021, 76, 1409–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapiluto, O.; Eizenberg, H.; Lati, R.N. Development of a temperature-based seed germination model for silverleaf nightshade (Solanum elaeagnifolium). Weed Sci. 2022, 70, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognacca, R.S.; Botto, J.F. Post-transcriptional regulation of seed dormancy and germination: Current understanding and future directions. Plant Commun. 2021, 2, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozaki, A.; Aoyanagi, T. Molecular Aspects of Seed Development Controlled by Gibberellins and Abscisic Acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.T.; Zhang, Y.L.; Chen, S.X.; Yin, G.H.; Yang, Z.Z.; Lee, S.; Liu, C.G.; Zhao, D.D.; Ma, Y.K.; Song, F.Q. Proteomics of methyl jasmonate induced defense response in maize leaves against Asian corn borer. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yoong, F.Y.; O’Neill, C.M.; Penfield, S. Temperature during seed maturation controls seed vigour through ABA breakdown in the endosperm and causes a passive effect on DOG1 mRNA levels during entry into quiescence. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 1311–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Qanmber, G.; Li, F.; Wang, Z. Updated role of ABA in seed maturation, dormancy, and germination. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 35, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauvermale, A.L.; Steber, C.M. GA signaling is essential for the embryo-to-seedling transition during Arabidopsis seed germination, a ghost story. Plant Signal Behav. 2020, 15, 1705028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graeber, K.; Linkies, A.; Steinbrecher, T.; Mummenhoff, K.; Tarkowská, D.; Turečková, V.; Ignatz, M.; Sperber, K.; Voegele, A.; de Jong, H. DELAY OF GERMINATION 1 mediates a conserved coat-dormancy mechanism for the temperature- and gibberellin-dependent control of seed germination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E3571–E3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, B.C.; Bicalho, E.M.; Munné-Bosch, S.; Garcia, Q.S. Abscisic acid regulates seed germination of Vellozia species in response to temperature. Plant Biol. 2017, 19, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhie, Y.H.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, K.S. Seed dormancy and germination in Jeffersonia dubia (Berberidaceae) as affected by temperature and gibberellic acid. Plant Biol. 2015, 17, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laspina, N.V.; Batlla, D.; Benech-Arnold, R.L. Dormancy cycling is accompanied by changes in ABA sensitivity in Polygonum aviculare seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 5924–5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Ogawa, M.; Kuwahara, A.; Hanada, A.; Kamiya, Y.; Yamaguchi, S. Activation of gibberellin biosynthesis and response pathways by low temperature during imbibition of Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Hu, G.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Shi, Q.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, Y. Reduced bioactive gibberellin content in rice seeds under low temperature leads to decreased sugar consumption and low seed germination rates. Plant Physiol. Bioch. 2018, 133, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murase, K.; Hirano, Y.; Sun, T.P.; Hakoshima, T. Gibberellin-induced DELLA recognition by the gibberellin receptor GID1. Nature 2008, 456, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauvermale, A.L.; Tuttle, K.M.; Takebayashi, Y.; Seo, M.; Steber, C.M. Loss of Arabidopsis thaliana seed dormancy is associated with increased accumulation of the GID1 GA Hormone Receptors. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, I.; Nakajima, M.; Park, S.H. Trails to the gibberellin receptor, GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1. Biosci. Biotech. Bioch. 2016, 80, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhang, Q.; He, D.; Zhou, Y.; Ni, H.; Tian, D.; Chang, G.; Jing, Y.; Lin, R.; Huang, J. AGAMOUS-LIKE67 Cooperates with the Histone Mark Reader EBS to Modulate Seed Germination under High Temperature. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, C.; Chen, H.; Castillo-Díaz, D.; Wen, B.; Cao, K.F.; Goodale, U.M. Regeneration and Endogenous Phytohormone Responses to High-Temperature Stress Drive Recruitment Success in Hemiepiphytic Fig Species. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 754207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Shang, L.; Wang, X.; Xing, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Z. MAPK11 regulates seed germination and ABA signaling in tomato by phosphorylating SnRKs. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 1677–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, G.; Ma, R.; Kong, Y.; Yuan, J. Selection of sensitive seeds for evaluation of compost maturity with the seed germination index. Waste Manag. 2021, 136, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Han, Y.; Li, J.; Ding, M.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, F.; Soppe, W.J.; Liu, Y. Arabidopsis thaliana SEED DORMANCY 4-LIKE regulates dormancy and germination by mediating the gibberellin pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Yamaguchi, S.; Lim, S.; Oh, E.; Park, J.; Hanada, A.; Kamiya, Y.; Choi, G. SOMNUS, a CCCH-Type Zinc Finger Protein in Arabidopsis, Negatively Regulates Light-Dependent Seed Germination Downstream of PIL5. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1260–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Tian, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, D.; Tong, B.; Liu, J. Transcriptome analysis of Cinnamomum migao seed germination in medicinal plants of Southwest China. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Bai, X.; Wu, X.; Xiang, D.; Wan, Y.; Luo, Y.; Shi, X.; Li, Q.; Zhao, J.; Qin, P. Transcriptome profiling identifies transcription factors and key homologs involved in seed dormancy and germination regulation of Chenopodium quinoa. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 151, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.J.; Jiang, W.; Wu, K.J.; Chen, J.D.; Li, Y.P.; Tao, Z.M. Integrating Transcriptomics and Hormones Dynamics Reveal Seed Germination and Emergence Process in Polygonatum cyrtonema Hua. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, M.Y.; Ma, X.M.; Luo, D.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, W.X.; Liu, Z.P. Transcriptome analysis and identification of abscisic acid and gibberellin-related genes during seed development of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.M.; Si, Q.D.; Yang, K.J.; Zhang, W.W.; Zhang, L.N.; Okita, T.W.; Yan, Y.Y.; Tian, L. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Effects of Exogenous Gibberellin on the Germination of Solanum torvum Seeds. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lu, B.; Liu, L.; Duan, W.; Jiang, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; et al. Melatonin promotes seed germination under salt stress by regulating ABA and GA3 in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 162, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Hao, X.; Wang, T.; Li, H.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, H. Seed Priming with Gibberellin Regulates the Germination of Cotton Seeds Under Low-Temperature Conditions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2023, 42, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M.; Chu, L.; Li, Q.; Yu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Fan, X.; Zhao, D.; et al. Brassinosteroid and gibberellin coordinate rice seed germination and embryo growth by regulating glutelin mobilization. Crop J. 2021, 9, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, A.; Daszkowska-Golec, A.; Szarejko, I. Updates on the Role of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) and ABSCISIC ACID-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTORs (ABFs) in ABA Signaling in Different Developmental Stages in Plants. Cells. 2021, 10, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, B.J.; He, H.; Hanson, J.; Willems, L.A.; Jamar, D.C.; Cueff, G.; Rajjou, L.; Hilhorst, H.W.; Bentsink, L. The Arabidopsis DELAY OF GERMINATION 1 gene affects ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) expression and genetically interacts with ABI3 during Arabidopsis seed development. Plant J. 2016, 85, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, C.N.; Proebsting, W.M.; Hedden, P.; Rivin, C.J. Gibberellins and seed development in maize. I. Evidence that gibberellin/abscisic acid balance governs germination versus maturation pathways. Plant Physiol. 2000, 122, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosbakh, S.; Porro, F.; Abeli, T.; Di Cecco, V.; Erschbamer, B.; Fernández-Calzado, R.; Jimenez-Alfaro, B.; Lodetti, S.; Lorite, J.; Moser, D.; et al. Understanding Long-Term Abundance Shifts in European Alpine Plants Through the Lenses of Functional Seed Trait Ecology. Divers. Distrib. 2025, 31, e70047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, S.; Imamura, A.; Watanabe, A.; Nakabayashi, K.; Okamoto, M.; Jikumaru, Y.; Hanada, A.; Aso, Y.; Ishiyama, K.; Tamura, N. High temperature-induced abscisic acid biosynthesis and its role in the inhibition of gibberellin action in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1368–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Kamiya, Y.; Sun, T. Distinct cell-specific expression patterns of early and late gibberellin biosynthetic genes during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant J. 2001, 28, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.P.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.X.; Yang, L.; Zeng, Z.Q.; Zhou, Y.L.; Chen, B.X. Advance in the Thermoinhibition of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) Seed Germination. Plants 2024, 13, 2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Li, R.; Yang, W.; Chen, Z.; Hu, X. Carbon monoxide signal regulates light-initiated seed germination by suppressing SOM expression. Plant Sci. 2018, 272, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chang, G.; Li, P.; Wei, J.; Yuan, X.; Huang, J.; Hu, X. Powerdress as the novel regulator enhances Arabidopsis seeds germination tolerance to high temperature stress by histone modification of SOM locus. Plant Sci. 2019, 284, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Mao, X.; Huang, J.; Ding, Y.; Wu, J.; Dong, S.; Kong, L.; Gao, G.; Li, C.Y.; Wei, L. KOBAS 2.0: A web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W316–W322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| TR_DN9758_c0_g1 | ATCTTCGGCTAAGCAGGTTGTGG | GGCAGTCTGGTGGTGATGGAATG |

| TR_DN4192_c0_g1 | GCTCGCTTACGCTTCCTCCAC | CCGTTGTTCTGTTGCTGCTGTTG |

| TR_DN20182_c0_g1 | TGCAGGAAGAAGGAGGAGCT | TGACTTGATCTTGCACCTTGGT |

| TR_DN1135_c0_g1 | GGCACTTCACAGACCAGGAACAC | CTTCTCCACCGTGGTTGTCATCC |

| TR_DN22662_c0_g1 | CCATTCTTCGCACCGCCTACG | GTGAGATTCCTCCATTCCGCTGAG |

| TR_DN22317_c0_g2 | TAGCCGCCTAGCCCACAACTAC | AGAAGGTCTACAGCCAGCGATCC |

| TR_DN2432_c0_g1 | ACGGAATGGAAATGCTTCGAGACG | TCCTCACCACATTCTCTGCTGTTC |

| TR_DN22510_c0_g1 | GGCAGAGTTAGCGTCCTTCGTG | AAGCCATCAGTAGCAAGCCTCAAC |

| TR_DN18060_c0_g1 | GCCACAAGCAGTTGTCGAATTAGC | CGCCACTTGCTCTAGTACTCGTAG |

| TR_DN58560_c0_g1 | GGATCAGCCGCAGCTCTTTCG | GACACCTGTTGCCTCTCCATTTCC |

| TR_DN5482_c1_g2 | GGGCTTGAGAAAGAGGTTGAGTGG | TTGCTGCCGCTGCTCCATAATC |

| TR_DN24_c0_g1 | GCGGAGGAGGAGGAGGAACAG | GCTTCTCAATCTCTGCTGCCTCAC |

| TR_DN17687_c0_g1 | AGGGAAGCCGAGTCTATGTCAAGG | TGTCCATAAGCCGAGAGACCTCAG |

| TR_DN8588_c0_g1 | AGCACAGCAAGCAAGGGAAAGG | GGACAGCCTCTCTTCAAGTTCAGC |

| TR_DN52805_c0_g1 | TGGGTTTGGATTTGGTGGTTGGG | GGCGGAGGTGGTATGGGAAATTG |

| TR_DN4365_c0_g1 | ATCCATTAGGCGTCACACCAACTG | CAGGATACCCAGCATCAGCCAAAC |

| TR_DN13626_c0_g1 | CTACTGCGACGAATAGCCAGAGC | ACGGCTCCTTCGGGTAGTTCC |

| TR_DN5097_c0_g1 | ATCGTGTCCAACTGCGGTGATTC | GTTCATCGGGTCTGTCAGGCTTG |

| TR_DN126267_c0_g1 | AAACCCGTCTCCCTTCTCTCCATC | TTGCTGTTCCTGTTCCTGTGAGTG |

| TR_DN37656_c0_g1 | TGACAGGTGACGGTGGAGTTGG | TCAGCCTATGTTCTCCGCCTACG |

| TR_DN9557_c0_g1 | CATGCCATCTGATCCGACTCATCC | GATCCTGCTCCTCCTCCTCTTCTC |

| TR_DN51204_c0_g1 | GCTTCTTGTGGATCGGCGATTTTC | TCCTTGTGACAGAACCTCCTCAGC |

| TR_DN22373_c0_g1 | ACACAGAGAAGTGGATGGGTTAAGT | GCTTCTAATAATGGCAGCTTGAGCA |

| TR_DN67320_c0_g1 | GGTGGTGATGAAGATGGAGTGGTG | CGCCGTTCTCCACCGTAACATAG |

| Genes | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| SPT | CATGCCATCTGATCCGACTCATCC | GATCCTGCTCCTCCTCCTCTTCTC |

| PIF1 | CTACTGCGACGAATAGCCAGAGC | ACGGCTCCTTCGGGTAGTTCC |

| ABI5 | GCTCGCTTACGCTTCCTCCAC | CCGTTGTTCTGTTGCTGCTGTTG |

| NCED9 | ACATAAGCTGAACCGGACAGTT | ATTTAACGGCGTGAATCATAC |

| CYP707A2 | CGGCGGTTATGACATTCCTAAGGG | TCTGAACTCCAACGGGTCCTTCC |

| GA2ox1 | ACCTCATTGTTAAGGCTTGCGAAGA | TTGTCGATACGAGGATGTGTTCGAC |

| GA20ox1 | TGCATCCCATATGAAACGTGAGTAC | GTTGACTACAAGAAAGAAACCGTGA |

| GA3ox1 | CCACCAACTCCATCAGCTCAGC | ATTTTGAGTCGGAAAGAGAGATGAG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Z.; Yang, L.; Feng, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, K.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, H.; Wei, S. Temperature Perception Regulates Seed Germination in Solanum nigrum via Phytohormone Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311757

Ma Z, Yang L, Feng Z, Li L, Wu K, Xiong Y, Huang H, Wei S. Temperature Perception Regulates Seed Germination in Solanum nigrum via Phytohormone Signaling Pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311757

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Ziqing, Lu Yang, Zhihong Feng, Longlong Li, Kaidie Wu, Yue Xiong, Hongjuan Huang, and Shouhui Wei. 2025. "Temperature Perception Regulates Seed Germination in Solanum nigrum via Phytohormone Signaling Pathways" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311757

APA StyleMa, Z., Yang, L., Feng, Z., Li, L., Wu, K., Xiong, Y., Huang, H., & Wei, S. (2025). Temperature Perception Regulates Seed Germination in Solanum nigrum via Phytohormone Signaling Pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311757