Proteomic Characterization of the Clostridium cellulovorans Cellulosome and Noncellulosomal Enzymes with Sorghum Bagasse

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

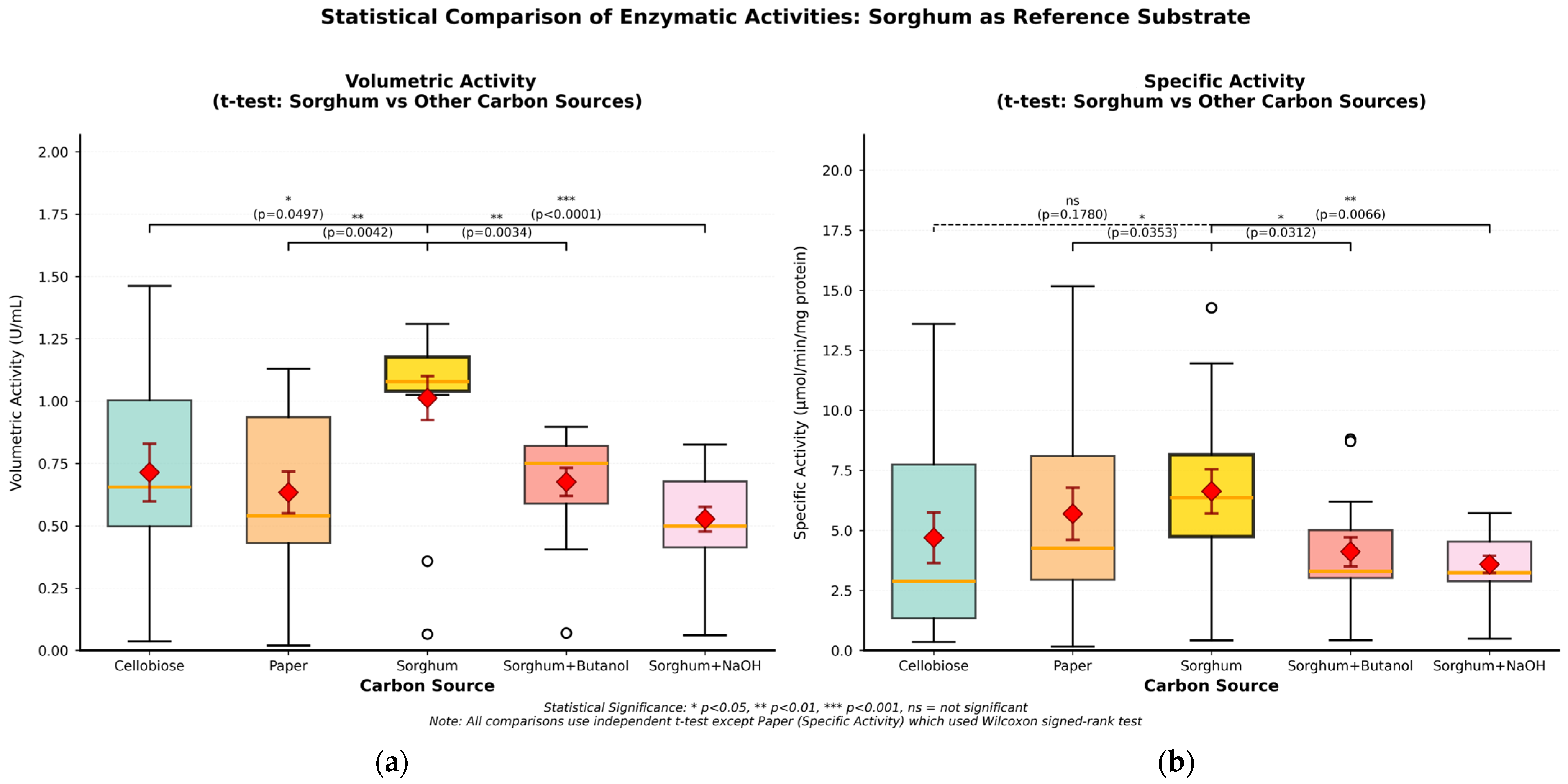

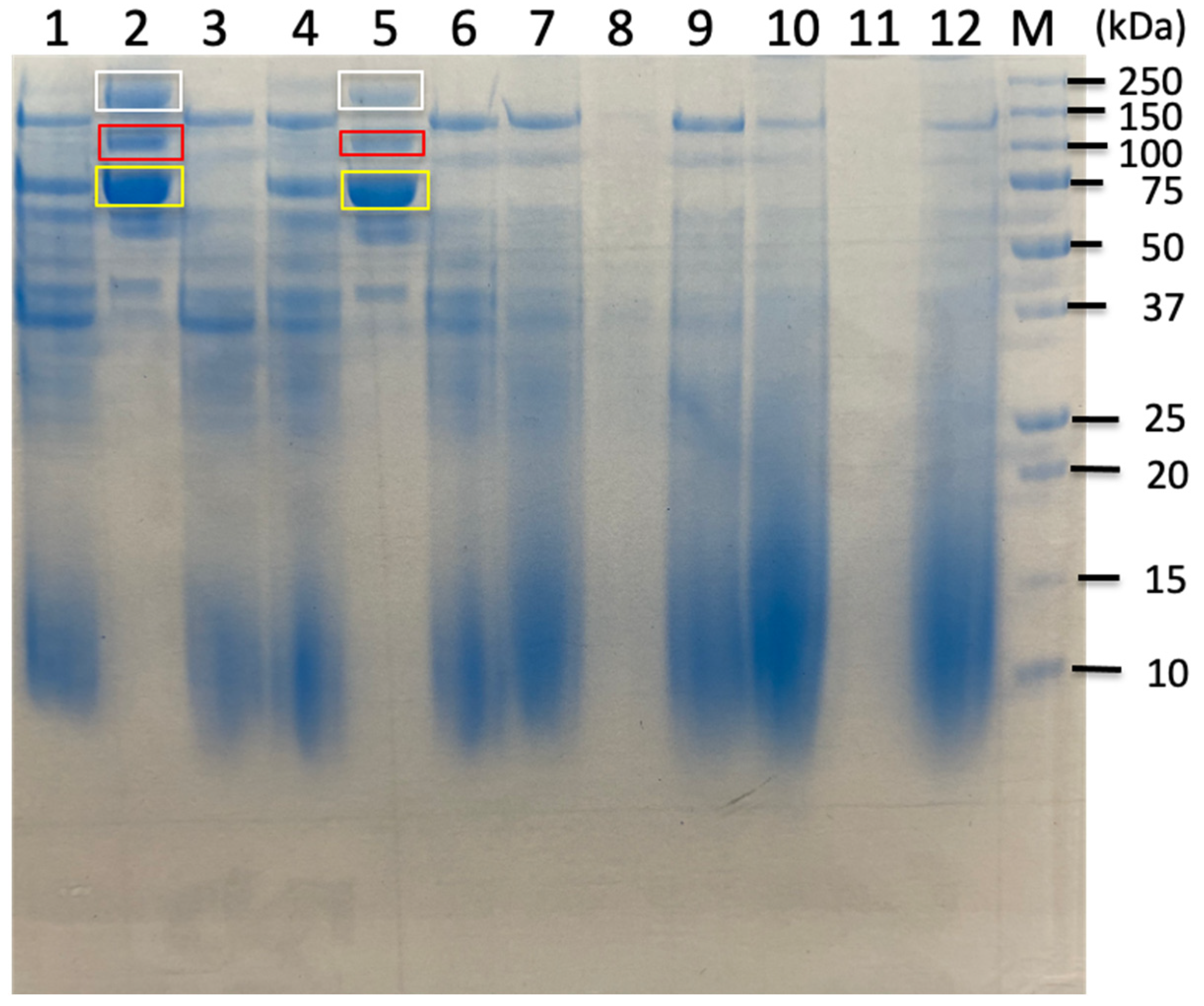

2.1. Evaluation of Chemical Pretreatment of Sorghum Bagasse Based on CMCase Activity

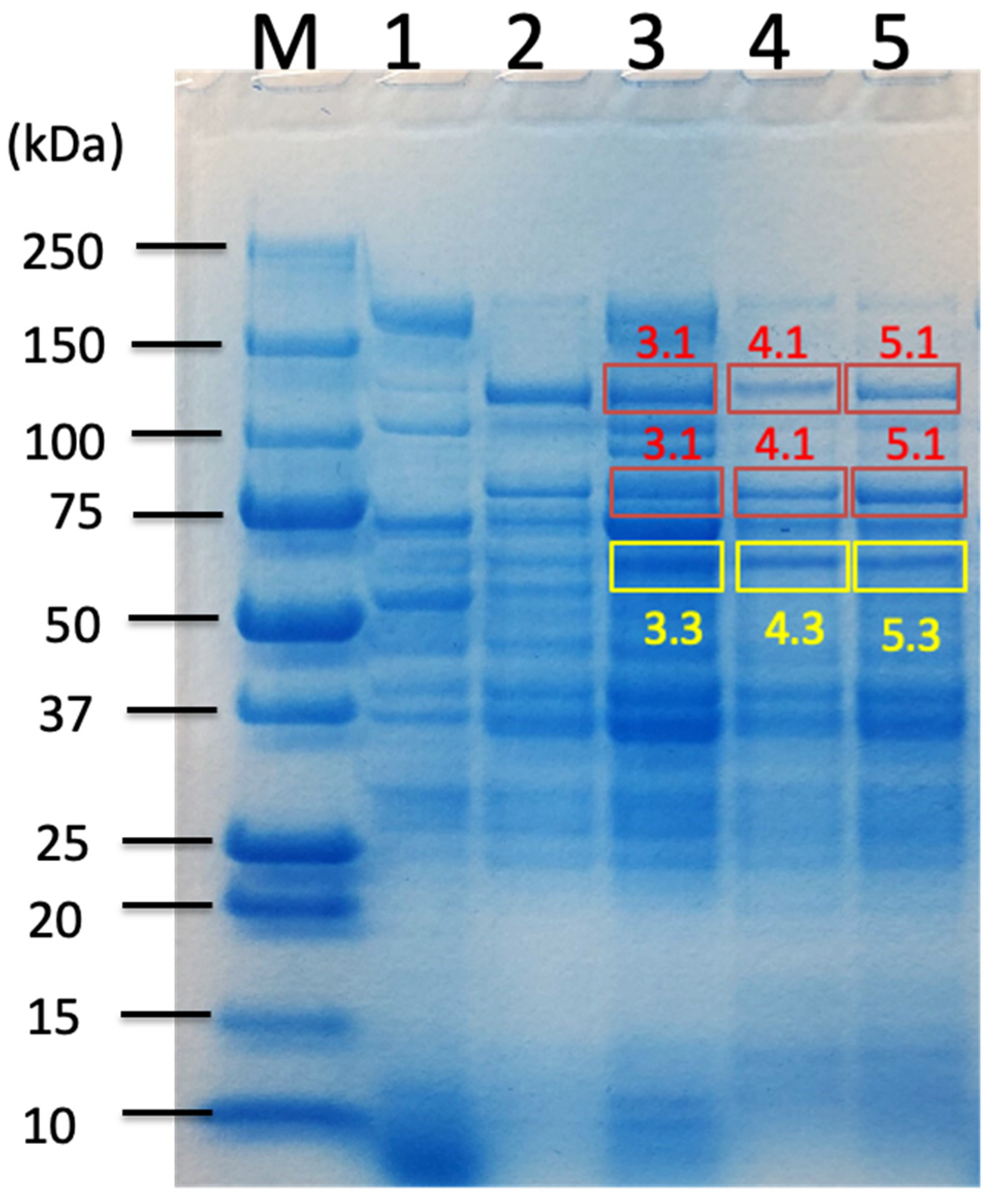

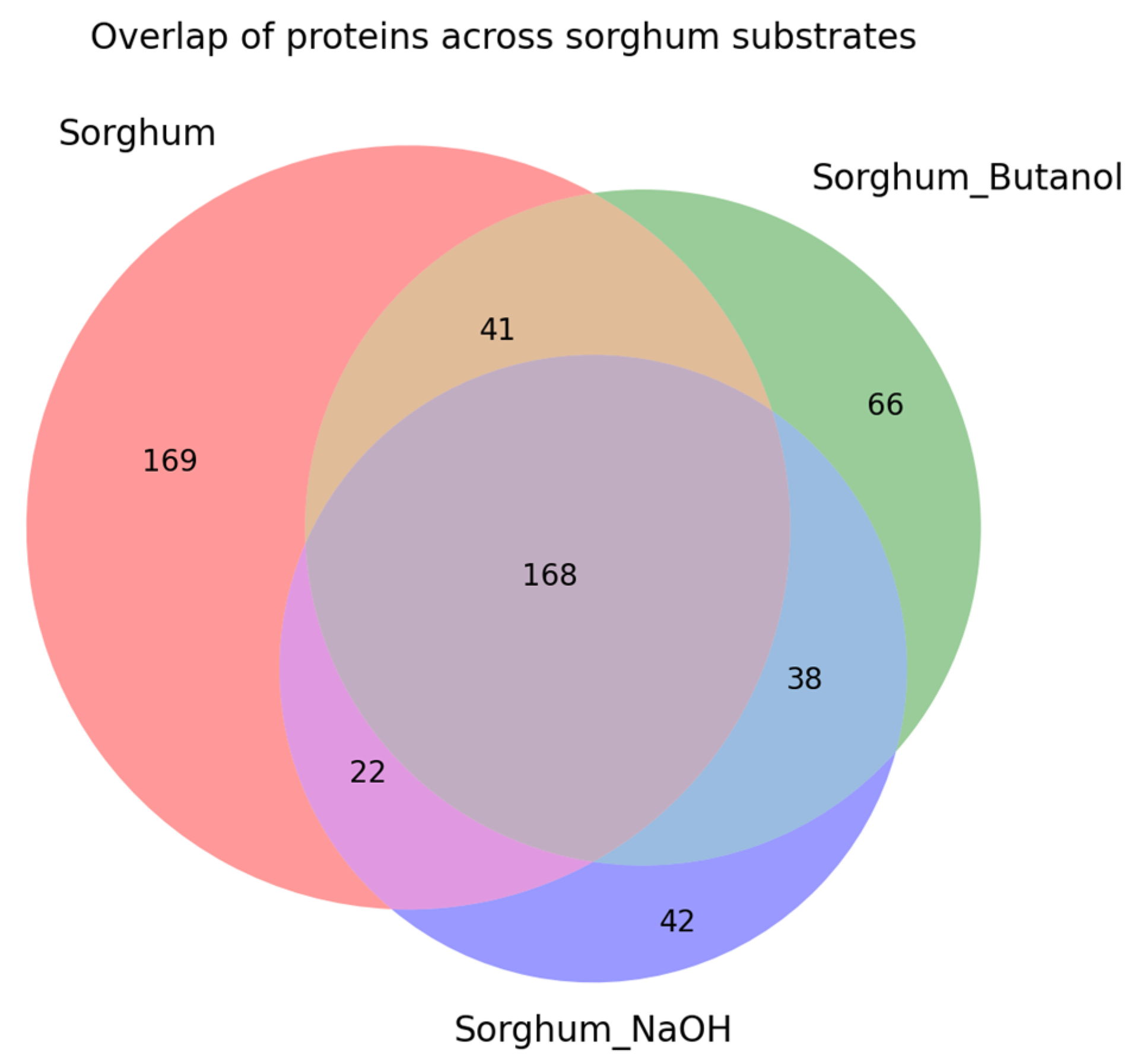

2.2. Proteomic Analysis of Carbohydrate-Related Proteins and Their Comparison Based on Sorghum Bagasse with or Without Chemical Pretreatments

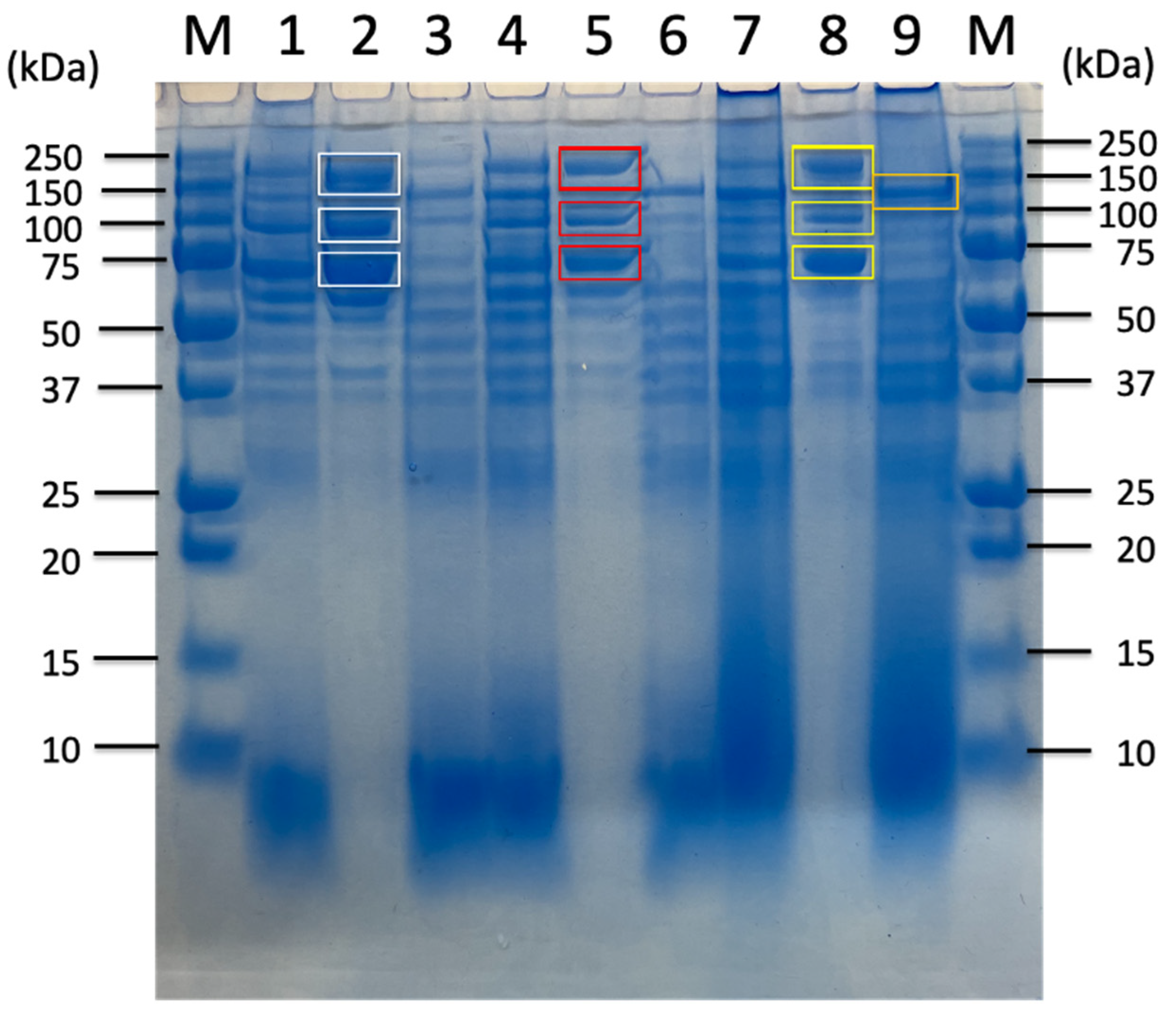

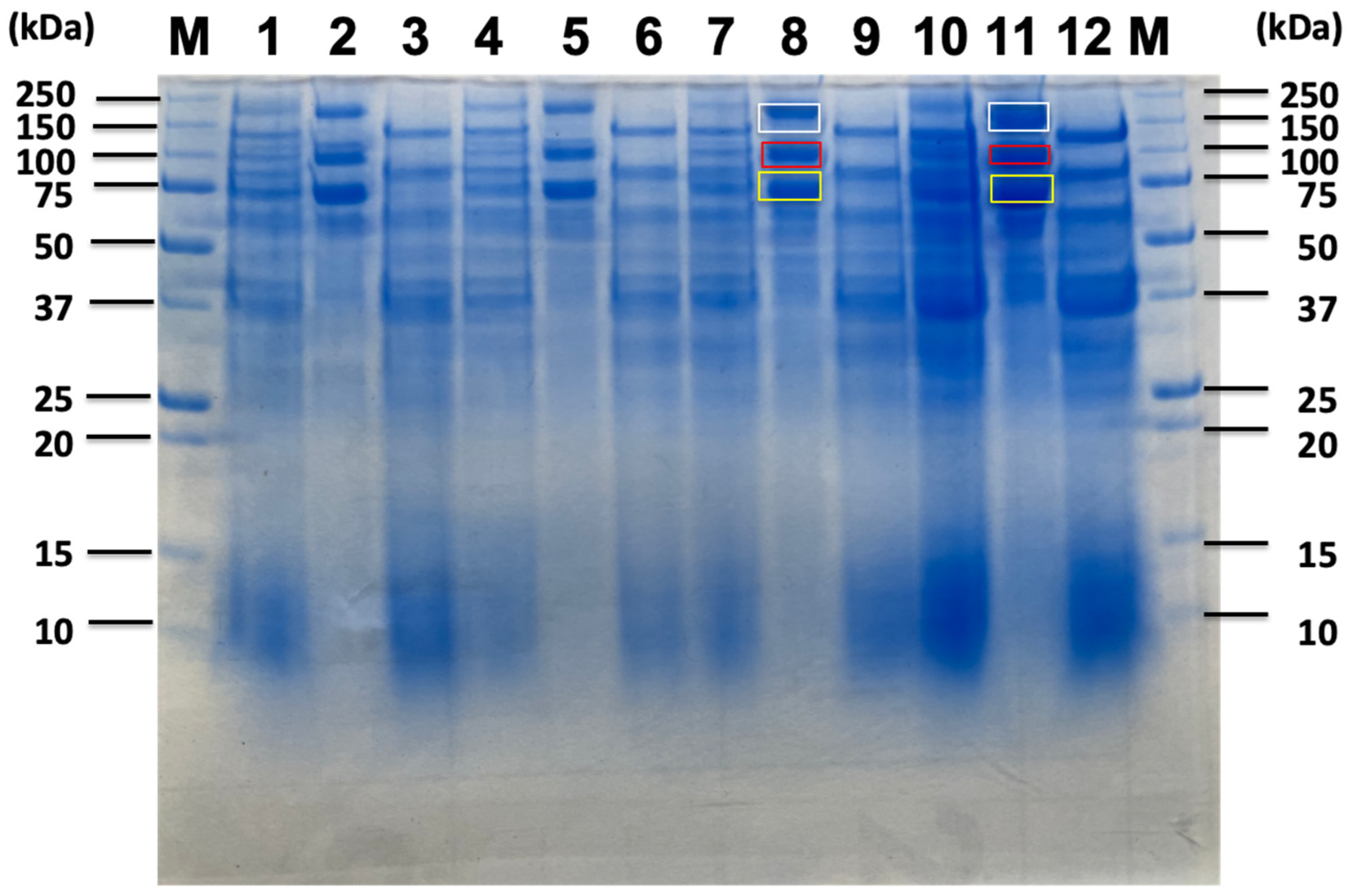

2.3. Proteomic Analysis of Sorghum-Related Proteins and Their Comparison Based on Untreated Sorghum Bagasse and Its Supernatants, and Sorghum Juice

2.4. Proteomic Analysis of Soluble Sugar-Related Proteins and Their Comparison Based on Untreated Sorghum Bagasse and Its Supernatants, and Sorghum Juice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strain and Culture Conditions

4.2. Substrate Preparation

4.3. Enzyme Preparation and Concentration

4.4. SDS-PAGE Analysis and Preparation of Crystalline Cellulose-Bound and Non-Bound Fractions

4.5. Enzyme Assay

4.6. LC-MS/MS Analysis and Data Acquisition

4.6.1. Chromatographic Conditions

4.6.2. Mass Spectrometry Parameters

4.7. Database Searching and Protein Identification

4.8. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGC | automatic gain control |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| C18 | Octadecylsilyl |

| CBM | carbohydrate-binding module |

| CBP | consolidated bioprocessing |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl cellulose |

| CMCase | Carboxymethyl cellulase |

| COG | Cluster of Orthologous Genes |

| DNS | 3,5-Dinitrosalicylic acid |

| DS | dockerin sequence |

| EDTA | ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| GH | glycoside hydrolase |

| HbpA | hydrophobic protein A |

| HCD | higher-energy collisional dissociation |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| ID | inner diameter |

| kDa | Kilodalton |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| MS | mass spectrometry |

| ODS | octadecylsilyl |

| PL | polysaccharide lyase |

| PSM | peptide–spectrum match |

| SDS-PAGE | sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis |

| UPLC | ultra-performance liquid chromatography |

References

- Esaka, K.; Aburaya, S.; Morisaka, H.; Kuroda, K.; Ueda, M. Exoproteome analysis of Clostridium cellulovorans in natural soft-biomass degradation. AMB Express 2015, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais Cardoso, L.; Pinheiro, S.S.; Martino, H.S.D.; Pinheiro-Sant’Ana, H.M. Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.): Nutrients, bioactive compounds, and potential impact on human health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, N.P.; Montanti, J.; Johnsto, D.B. Sorghum as a renewable feedstock for production of fuels and industrial chemicals. AIMS Bioeng. 2016, 3, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.R.; Kee Woong Park, K.W.; Kim, Y.K.; Sang Un Park, S.U.; Pyon, J.Y. Enhancing sorgoleone levels in grain sorghum root exudates. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010, 36, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaru, Y.; Miyake, H.; Kuroda, K.; Nakanishi, A.; Kawade, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Uemura, M.; Fujita, Y.; Doi, R.H.; Ueda, M. Genome sequence of the cellulosome-producing mesophilic organism Clostridium cellulovorans 743B. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 901–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamaru, Y.; Miyake, H.; Kuroda, K.; Nakanishi, A.; Matsushima, C.; Doi, R.H.; Ueda, M. Comparison of the mesophilic cellulosome-producing Clostridium cellulovorans genome with other cellulosome-related clostridial genomes. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisaka, H.; Matsui, K.; Tatsukami, Y.; Kuroda, K.; Miyake, H.; Tamaru, Y.; Ueda, M. Profile of native cellulosomal proteins of Clostridium cellulovorans adapted to various carbon sources. AMB Express 2012, 2, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aburaya, S.; Aoki, W.; Kuroda, K.; Minakuchi, H.; Ueda, M. Temporal proteome dynamics of Clostridium cellulovorans cultured with major plant cell wall polysaccharides. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usai, G.; Cirrincione, S.; Re, A.; Manfredi, M.; Pagnani, A.; Pessione, E.; Mazzoli, R. Clostridium cellulovorans metabolism of cellulose as studied by comparative proteomic approach. J. Proteom. 2020, 216, 103667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eljonaid, M.Y.; Tomita, H.; Okazaki, F.; Tamaru, Y. Enzymatic characterization of unused biomass degradation using the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Rondon, V.; Weeks, K.; Pullammanappallil, P.; Ingram, L.O.; Shanmugam, K.T. Efficient extraction method to collect sugar from sweet sorghum. J. Biol. Eng. 2013, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y. Valorization of sugarcane bagasse for sugar extraction and residue as an adsorbent for pollutant removal. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 893941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-Olea, E.; Pérez-Carrillo, E.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O. Effects of extrusion pretreatment parameters on sweet sorghum bagasse enzymatic hydrolysis and its subsequent conversion into bioethanol. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 325905. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, K.; Bae, J.; Esaka, K.; Morisaka, H.; Kuroda, K.; Ueda, M. Exoproteome profiles of Clostridium cellulovorans grown on various carbon sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 6576–6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaru, Y.; Doi, R.H. The engL gene cluster of Clostridium cellulovorans contains a gene for cellulosomal manA. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, M.A.; Takagi, M.; Hashida, S.; Shoseyov, O.; Doi, R.H.; Segel, I.H. Characterization of the cellulose-binding domain of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulose-binding protein A. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 5762–5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ouyang, D.; Zhou, Z.; Page, S.J.; Liu, D.; Zhao, X. Lignocellulosic biomass as sustainable feedstock and materials for power generation and energy storage. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 57, 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wodajo, B.; Zhao, K.; Tang, S.; Xie, Q.; Xie, P. Unravelling sorghum functional genomics and molecular breeding: Past achievements and future prospects. J. Gen. Genom. 2025, 52, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, M.; Sazuka, T.; Oda, Y.; Kawahigashi, H.; Wu, J.; Takanashi, H.; Ohnishi, T.; Yoneda, J.I.; Ishimori, M.; Kajiya-Kanegae, H.; et al. Transcriptional switch for programmed cell death in pith parenchyma of sorghum stems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E8783–E8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.M.; Leng, C.Y.; Luo, H.; Wu, X.Y.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.M.; Zhang, H.; Xia, Y.; Shang, L.; Liu, C.M.; et al. Sweet sorghum originated through selection of Dry, a plant-specific NAC transcription factor gene. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 2286–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hopfield, J.J.; Winfree, E. Neural network computation by in vitro transcriptional circuits. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2004, 17, 681–688. [Google Scholar]

- Genot, A.J.; Fujii, T.; Rondelez, Y. Scaling down DNA circuits with competitive neural networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 10, 20130212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, S.; Gines, G.; Lobato-Dauzier, N.; Baccouche, A.; Deteix, R.; Fujii, T.; Rondelez, Y.; Genot, A.J. Nonlinear decision-making with enzymatic neural networks. Nature 2022, 610, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gado, J.E.; Beckham, G.T.; Payne, C.M. Improving enzyme optimum temperature prediction with resampling strategies and ensemble learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 4098–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Dong, S.; Tian, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Mitra, R.; Han, J.; Li, C.; Han, X.; et al. Computational redesign of a PETase for plastic biodegradation under ambient conditions by the GRAPE strategy. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 1340–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, H.; Okazaki, F.; Tamaru, Y. Biomethane production from sugar beet pulp under cocultivation with Clostridium cellulovorans and methanogens. AMB Express 2019, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, H.; Okazaki, F.; Tamaru, Y. Direct IBE fermentation from mandarin orange wastes by combination of Clostridium cellulovorans and Clostridium beijerinckii. AMB Express 2019, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, H.; Tamaru, Y. The second-generation biomethane from mandarin orange peel under cocultivation with methanogens and the armed Clostridium cellulovorans. Fermentation 2019, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukiekolo, R.; Cho, H.Y.; Kosugi, A.; Inui, M.; Yukawa, H.; Doi, R.H. Degradation of corn fiber by Clostridium cellulovorans cellulases and hemicellulases and contribution of scaffolding protein CbpA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 3504–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaru, Y.; Ui, S.; Murashima, K.; Kosugi, A.; Chan, H.; Doi, R.H.; Liu, B. Formation of protoplasts from cultured tobacco cells and Arabidopsis thaliana by the action of cellulosomes and pectate lyase from Clostridium cellulovorans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 2614–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah-Nkansah, N.B.; Li, J.; Rooney, W.; Wang, D. A review of sweet sorghum as a viable renewable bioenergy crop and its techno-economic analysis. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, A.; Murashima, K.; Doi, R.H. Xylanase and acetyl xylan esterase activities of XynA, a key Subunit of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome for xylan degradation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 6399–6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Day, D.F. Composition of sugar cane, energy cane, and sweet sorghum suitable for ethanol production at Louisiana sugar mills. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, Q.K.; Kapoor, M.; Mahajan, L.; Hoondal, G.S. Microbial xylanases and their industrial applications: A review. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 56, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, M.; Chen, C.; Qi, K.; Chen, C.; Cui, Q.; Kosugi, A.; Liu, Y.J.; Feng, Y. Effective conversion of lignocellulose to fermentable sugars using engineered Clostridium thermocellum with co-enhanced cellulolytic and xylanolytic activities. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 440, 133466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosugi, A.; Amano, Y.; Murashima, K.; Doi, R.H. Hydrophilic domains of scaffolding protein CbpA promote glycosyl hydrolase activity and localization of cellulosomes to the cell surface of Clostridium cellulovorans. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 6351–6359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaru, Y.; Doi, R.H. Pectate lyase A, an enzymatic subunit of the Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4125–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuskin, F.; Baslé, A.; Ladevèze, S.; Day, A.M.; Gilbert, H.J.; Davies, G.J.; Potocki-Véronèse, G.; Lowe, E.C. The GH130 family of mannoside phosphorylases contains glycoside hydrolases that target β-1,2-mannosidic linkages in Candida mannan. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 25023–25033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Laville, E.; Tarquis, L.; Lombard, V.; Ropartz, D.; Terrapon, N.; Henrissat, B.; Guieysse, D.; Esque, J.; Durand, J.; et al. Analysis of the diversity of the glycoside hydrolase family 130 in mammal gut microbiomes reveals a novel mannoside-phosphorylase function. Microb. Genom. 2020, 6, e000404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modenbach, A.A.; Nokes, S.E. Enzymatic hydrolysis of biomass at high-solids loadings—A review. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 56, 526–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, R.H.; Tamaru, Y. The Clostridium cellulovorans cellulosome: An enzyme complex with plant cell wall degrading activity. Chem. Rec. 2001, 1, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashima, K.; Kosugi, A.; Doi, R.H. Synergistic effects on crystalline cellulose degradation between cellulosomal cellulases from Clostridium cellulovorans. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 5088–5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teugjas, H.; Väljamäe, P. Product inhibition of cellulases studied with 14C-labeled cellulose substrates. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamed, R.; Kenig, R.; Morag, E.; Calzada, J.F.; de Micheo, F.; Bayer, E.A. Efficient cellulose solubilization by a combined cellulosome-13-glucosidase system. Appl. Biochern. Biotech. 1991, 27, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.O.; Cho, H.Y.; Yukawa, H.; Inui, M.; Doi, R.H. Regulation of expression of cellulosomes and noncellulosomal (hemi)cellulolytic enzymes in Clostridium cellulovorans during growth on different carbon sources. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 4218–4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kancelista, A.; Chmielewska, J.; Korzeniowski, P.; Łaba, W. Bioconversion of Sweet Sorghum Residues by Trichoderma citrinoviride C1 enzymes cocktail for effective bioethanol production. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teramura, H.; Sasaki, K.; Oshima, T.; Kawaguchi, H. Effective usage of sorghum bagasse: Optimization of organosolv pretreatment using 25% 1-butanol and subsequent nanofiltration membrane separation. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 252, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunna, K.; Nakasaki, K.; Auresenia, J.L.; Abella, L.C.; Gaspillo, P.D. Effect of alkali pretreatment on removal of lignin from sugarcane bagasse. Chem. Engin. Trans. 2017, 56, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar]

| Carbon Sources | Mean Specific Activity (U/mg) | Peak Specific Activity (U/mg) | Time to Peak (h) | Mean Volumetric Activity (U/mL) | Peak Volumetric Activity (U/mL) | Time to Peak (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellobiose | 4.70 | 13.60 | 123 | 0.71 | 1.46 | 170 |

| Filter paper | 5.70 | 15.17 | 146 | 0.63 | 1.13 | 146 |

| Untreated sorghum bagasse | 6.63 | 14.27 | 123 | 1.01 | 1.31 | 84 |

| Sorghum bagasse + butanol | 4.11 | 8.81 | 123 | 0.68 | 0.90 | 24 |

| Sorghum bagasse + NaOH | 3.59 | 5.72 | 84 | 0.53 | 0.83 | 24 |

| Untreated Sorghum Bagasse | Butanol-Treated Sorghum Bagasse | Alkaline-Treated Sorghum Bagasse | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. cellulovorans Proteins from Uniplot Database | Band 3.1 | Band 3.3 | Band 4.1 | Band 4.3 | Band 5.1 | Band 5.3 | |

| Cellulosomal proteins | D9SS72_ExgS GH48-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| D9SX09_CBM30-GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SS71_GH9-CBM3-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| A0A173MZP3_Eng9D GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SS70_EngK CBM4-GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| A0A173N050_Man26A-DS CBM35-GH26-CBM35-CBM35-CBM35-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SV64_AidA-GH1-CBM65-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SX08_Pectate lyase_PelB-PL6-Helix-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SQV8_CBM35-GH26-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9ST82_GH9-CBM3-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SS66_CBM4-GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SRK9_GH9-CBM3-DS | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SST3_XynA CBM4-GH10-DS | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N038_Ukcg1-DS | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZR7_Xyn8A GH8-DS | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9STT6_PL11-DS | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SWK5_CBM27-CBM35-like-esterase-DS | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SS68_GH9-DS | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N017_Eng5C BglC-DS | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SQT1_CBM35-GH26-DS | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SS67_ManA DS-GH5 | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SWK5_CBM27-CBM35-like-esterase-DS | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SW41_GH5 BglC-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| Schaholdin related: | |||||||

| P38058_CbpA | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SS73_cohesin-containing protein CbpA | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SN69_Cellulosome anchoring protein cohesin region | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SR53_Cellulosome anchoring protein cohesin region type-II cohesin | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Noncellulosomal proteins | Q6DTY2_EngO CBM4-GH9 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| A0A173N0C7_Agal31D | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| A0A173MZT5_Axyl31A | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| A0A173MZV6_Axyl31B | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SR72_Alpha-L-fucosidase GH65 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| A0A173MZW6_Agal31A | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SQL7_Alpha-galactosidase GH36 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| A0A173N0D6_Eng9E GH9 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SW83_CBM4-GH9 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SR73_Xylose isomerase | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZS5_Bgl3C BglX | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| A0A173N033_Man26F CBM27-GH26-CBM11 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SWQ0_GH5-CBM17 | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173N0B1_Bxyl43A | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SMP5_GH42 GanA | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| D9ST71_GH31 | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SW84_CBM4-GH9 | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N0E7_Pel1B, PL1, PL9 | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZV4_BglB | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZT4_Bgl3D GH2-BglX | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZT0_BglD | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZN4_Exo-1,3-beta-glucanase D GH1-CBMX2 | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SUC7_Glycosidase GH130 related protein (Clocel_3197) | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| P28623_EngD GH5-CBM2 | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZZ7_Epl9B | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZW5_Bman2A LacZ-CBM-like | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9STN1_GH127 beta-L-arabinofuranosidase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | |

| Untreated Sorghum Bagasse | Sorghum Supernatnat | 3% Sorghum Juice | 5% Sorghum Juice | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identified Proteins from Sorghum Related Substrates | 180 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 120 kDa Band (Avicel Non-Bound) | 100 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 70 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 180 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 100 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 70 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 180 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 100 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 70 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 180 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 100 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 70 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | |

| Cellulosomal proteins | D9SS72_ExgS GH48-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| D9SX09_CBM30-GH9-DS | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SS71_GH9-CBM3-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| A0A173MZP3_Eng9D GH9-DS | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| D9SS70_EngK CBM4-GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| A0A173N050_Man26A-DS CBM35-GH26-CBM35-CBM35-CBM35-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SV64_AidA-GH1-CBM65-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SX08_Pectate lyase_PelB-PL6-Helix-DS | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SQV8_CBM35-GH26-DS | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9ST82_GH9-CBM3-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| D9SS66_CBM4-GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| D9SRK9_GH9-CBM3-DS | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| D9SST3_XynA CBM4-GH10-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| A0A173N038_Ukcg1-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZR7_Xyn8A GH8-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9STT6_PL11-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SWK5_CBM27-CBM35-like-esterase-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SS68_GH9-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173N017_Eng5C BglC-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SQT1_CBM35-GH26-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SS67_ManA DS-GH5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| D9SWK5_CBM27-CBM35-like-esterase-DS | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SW41_GH5 BglC-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZP8_rhamnogalacturonan lyase-DS | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZN7_Ukcg2-DS | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N041_Eng5A BglC-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| D9STQ5 CBMX2-GH5-CBM11-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SWN8_GH44-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| D9SVB3_CBM13-CBM35-GH98-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZX7_Eng5E BglC-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| Schaholdin related: | ||||||||||||||

| P38058_CbpA | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SS73_cohesin-containing protein CbpA | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SN69_Cellulosome anchoring protein cohesin region | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SUN3_Type-II cohesin | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SR53_Cellulosome anchoring protein cohesin region type-II cohesin | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Noncellulosomal proteins | Q6DTY2_EngO CBM4-GH9 | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | ● |

| A0A173N0C7_Agal31D | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZT5_Axyl31A | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZV6_Axyl31B | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SR72_Alpha-L-fucosidase GH65 | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZW6_Agal31A | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SQL7_Alpha-galactosidase GH36 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N0D6_Eng9E GH9 | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SW83_CBM4-GH9 | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SR73_Xylose isomerase | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173MZS5_Bgl3C BglX | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N033_Man26F CBM27-GH26-CBM11 | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SWQ0_GH5-CBM17 | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N0B1_Bxyl43A | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SMP5_GH42 GanA | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9ST71_GH31 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SW84_CBM4-GH9 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N0E7_Pel1B, PL1, PL9 | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZV4_BglB | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZT4_Bgl3D GH2-BglX | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZT0_BglD | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZN4_Exo-1,3-beta-glucanase D GH1-CBMX2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SUC7_Glycosidase GH130 related protein (Clocel_3197) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| P28623_EngD GH5-CBM2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZZ7_Epl9B | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZW5_Bman2A LacZ-CBM-like | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9STN1_GH127 beta-L-arabinofuranosidase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Q8GEE5_Arabinofrunosidase GH51 | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SQU9_GH43 xylanase | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZQ8_Lam16B GH16-CBM4-CBM4-CBM4 | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N064_Bgal2A | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZY8_Xyip YcjR | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZX3_Agal53B GanB | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N093_Agal53A GanB-YdjB-FhaB | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZS9_Bgl3A BglX-CBM6-like | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SUV4_AraA L-arabinose isomerase | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZZ3_Ara43D Afaf | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SVV4_GH2 LacZ | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZW5_Bman2A LacZ-CBM-like | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SQB8_GH43 endo-alpha-1,5-L-arabinanase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SVJ6_CBM48-GH13 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N053_XynB Bxyl39B | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| 1% Glucose Medium | 0.5% Celloobiose Medium | 0.5% Sucrose Medium | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiied Proteins from Sorghum Related Substrates | 180 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 100 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 70 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 180 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 100 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 70 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 180 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 100 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | 70 kDa Band (Avicel Bound) | |

| Cellulosomal proteins | D9SS72_ExgS GH48-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| D9SX09_CBM30-GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| D9SS71_GH9-CBM3-DS | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| A0A173MZP3_Eng9D GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SS70_EngK CBM4-GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173N050_Man26A-DS CBM35-GH26-CBM35-CBM35-CBM35-DS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | |

| D9SV64_AidA-GH1-CBM65-DS | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | |

| D9SX08_Pectate lyase_PelB-PL6-Helix-DS | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SQV8_CBM35-GH26-DS | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| D9ST82_GH9-CBM3-DS | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | |

| D9SS66_CBM4-GH9-DS | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SRK9_GH9-CBM3-DS | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SST3_XynA CBM4-GH10-DS | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173N038_Ukcg1-DS | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZR7_Xyn8A GH8-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9STT6_PL11-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SWK5_CBM27-CBM35-like-esterase-DS | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SW41_GH5 BglC-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SS68_GH9-DS | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173N017_Eng5C BglC-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SQT1_CBM35-GH26-DS | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SS67_ManA DS-GH5 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SWK5_CBM27-CBM35-like-esterase-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZP8_rhamnogalacturonan lyase-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZN7_Ukcg2-DS | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SWN8_GH44-DS | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173MZX7_Eng5E BglC-DS | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173N041_Eng5A BglC-DS | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9STQ5_CBMX2-GH5-CBM11-DS | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZR1_Non-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SVB3_CBM13-CBM35-GH98-DS | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Scaholdin related: | ||||||||||

| P38058_CbpA | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SS73_cohesin-containing protein CbpA | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| D9SN69_Cellulosome anchoring protein cohesin region | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SS69_HbpA Cellulosome anchoring protein cohesin region | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SR53_Cellulosome anchoring protein cohesin region type-II cohesin | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SUN3 Type-II cohesin | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Noncellulosomal proteins | Q6DTY2_EngO CBM4-GH9 | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | ● |

| A0A173N0C7_Agal31D_sample3.3 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZT5_Axyl31A | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZV6_Axyl31B | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SR72_GH65 Alpha-L-fucosidase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173MZW6_Agal31A | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | |

| D9SQL7_alpha-galactosidase GH36 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N0D6_Eng9E GH9 | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SW83_CBM4-GH9 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SR73_Xylose isomerase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZS5_Bgl3C BglX | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| A0A173N033_Man26F CBM27-GH26-CBM11 | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SWQ0_GH5-CBM17 | ● | ● | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173N0B1_Bxyl43A | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SMP5_GH42 GanA | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9ST71_GH31 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SW84_CBM4-GH9 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N0E7_Pel1B, PL1, PL9 | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZV4_BglB | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZT4_Bgl3D GH2-BglX | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173MZT0_BglD | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZN4_Exo-1,3-beta-glucanase D GH1-CBMX2 | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| D9SUC7_Glycosidase GH130 related protein (Clocel_3197) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| P28623_EngD GH5-CBM2 | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZZ7_Epl9B | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZZ3_Ara43D Afaf | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SUV4_AraA L-arabinose isomerase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173MZW5_Bman2A LacZ-CBM-like | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9STN1_GH127 Beta-L-arabinofuranosidase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Q8GEE5_Arabinofrunosidase GH51 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SQU9_GH43 xylanase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZQ8_Lam16B GH16-CBM4-CBM4-CBM4 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N064_Bgal2A | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173MZS9_Bgl3A BglX-CBM6-like | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| D9SVV4_GH2 LacZ | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZW5_Bman2A LacZ-CBM-like | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SW83_CBM4-GH9 | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | ● | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SQB8 GH43 endo-alpha-1,5-L-arabinanase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SVJ6 CBM48-GH13 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SW84_CBM4-GH9 | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N053_XynB Bxyl39B | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| Q65CL4_PelB | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9STR9_PL10 Pectate lyase | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

| A0A173N082_Ara43D GH43-Sugar-binding site | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N090_AraA | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | |

| A0A173N012_EplC | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N096_Bgal42A GenA | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SLW4_GH57 1,4-alpha-glucan branching enzyme | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZX6_Amy13C | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173N071_Ukcg4 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZW0_Agal31C GH36 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| A0A173MZT8_Man26E ManB2 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | n.d. | n.d. | |

| D9SUU1_GH43 Alpha-L-arabinofuranosidase | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | ● | |

All substrate;

All substrate;  Untreated soghum only;

Untreated soghum only;  Untreated sorghum bagasse in Avicel-bound protein only;

Untreated sorghum bagasse in Avicel-bound protein only;  Butanol-treated or Alkaline-treated sorghum bagasse;

Butanol-treated or Alkaline-treated sorghum bagasse;  Alkaline-treated sorghum bagasse or sorghum juice;

Alkaline-treated sorghum bagasse or sorghum juice;  Sorghum supernatant or sorghum juice;

Sorghum supernatant or sorghum juice;  Untreated sorghum bagasse in Avicel-binding protein or sorghum supernatant, or sorghum juice;

Untreated sorghum bagasse in Avicel-binding protein or sorghum supernatant, or sorghum juice;  Sorghum supernatant only;

Sorghum supernatant only;  Sorghum juice only;

Sorghum juice only;  Soluble sugar only.

Soluble sugar only.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eljonid, M.Y.; Okazaki, F.; Hishinuma, E.; Matsukawa, N.; Hamido, S.; Tamaru, Y. Proteomic Characterization of the Clostridium cellulovorans Cellulosome and Noncellulosomal Enzymes with Sorghum Bagasse. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311728

Eljonid MY, Okazaki F, Hishinuma E, Matsukawa N, Hamido S, Tamaru Y. Proteomic Characterization of the Clostridium cellulovorans Cellulosome and Noncellulosomal Enzymes with Sorghum Bagasse. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311728

Chicago/Turabian StyleEljonid, Mohamed Y., Fumiyoshi Okazaki, Eiji Hishinuma, Naomi Matsukawa, Sahar Hamido, and Yutaka Tamaru. 2025. "Proteomic Characterization of the Clostridium cellulovorans Cellulosome and Noncellulosomal Enzymes with Sorghum Bagasse" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311728

APA StyleEljonid, M. Y., Okazaki, F., Hishinuma, E., Matsukawa, N., Hamido, S., & Tamaru, Y. (2025). Proteomic Characterization of the Clostridium cellulovorans Cellulosome and Noncellulosomal Enzymes with Sorghum Bagasse. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11728. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311728