The Influence of Chemical Structure on the Electronic Structure of Propylene Oxide

Abstract

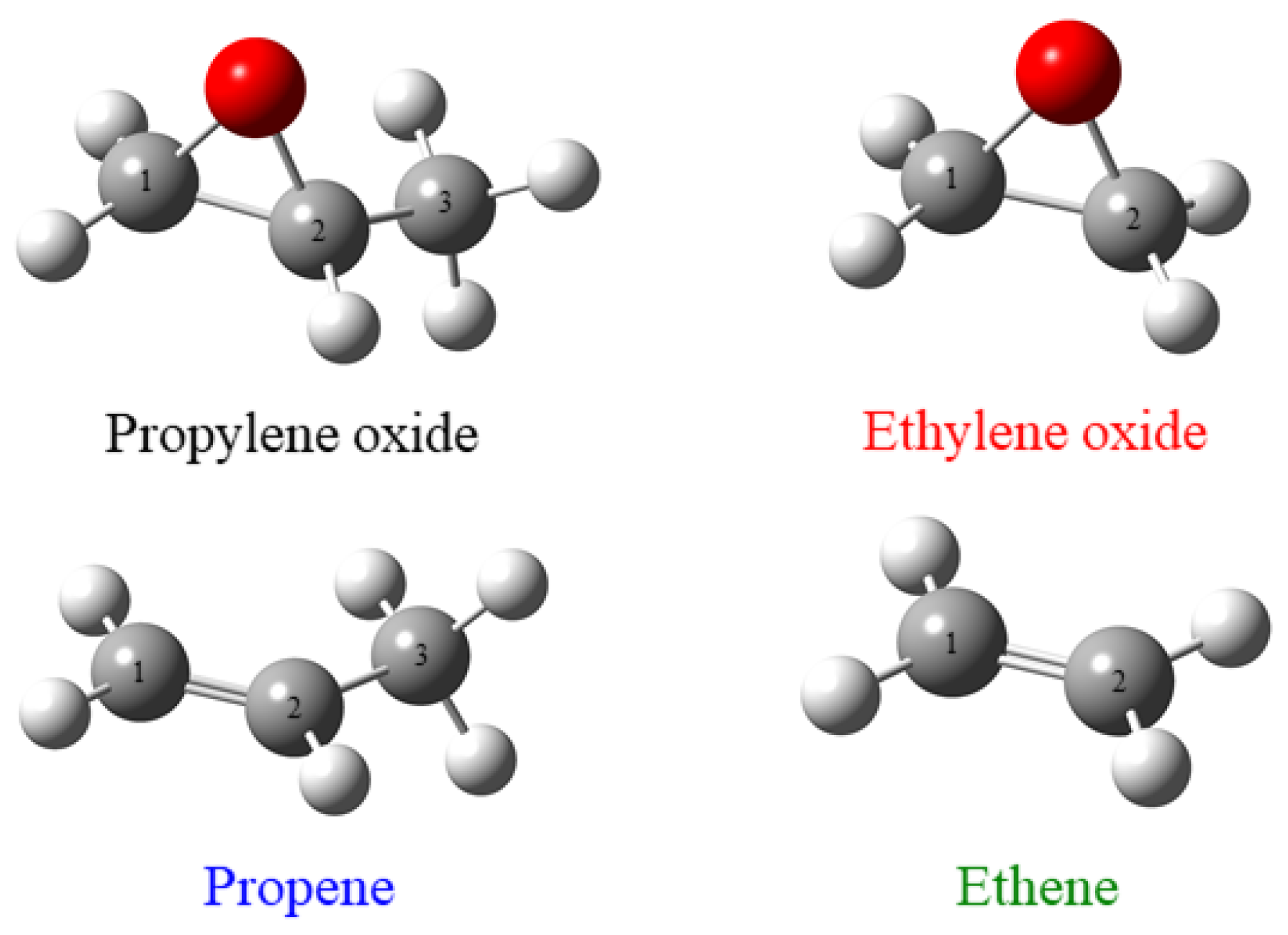

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

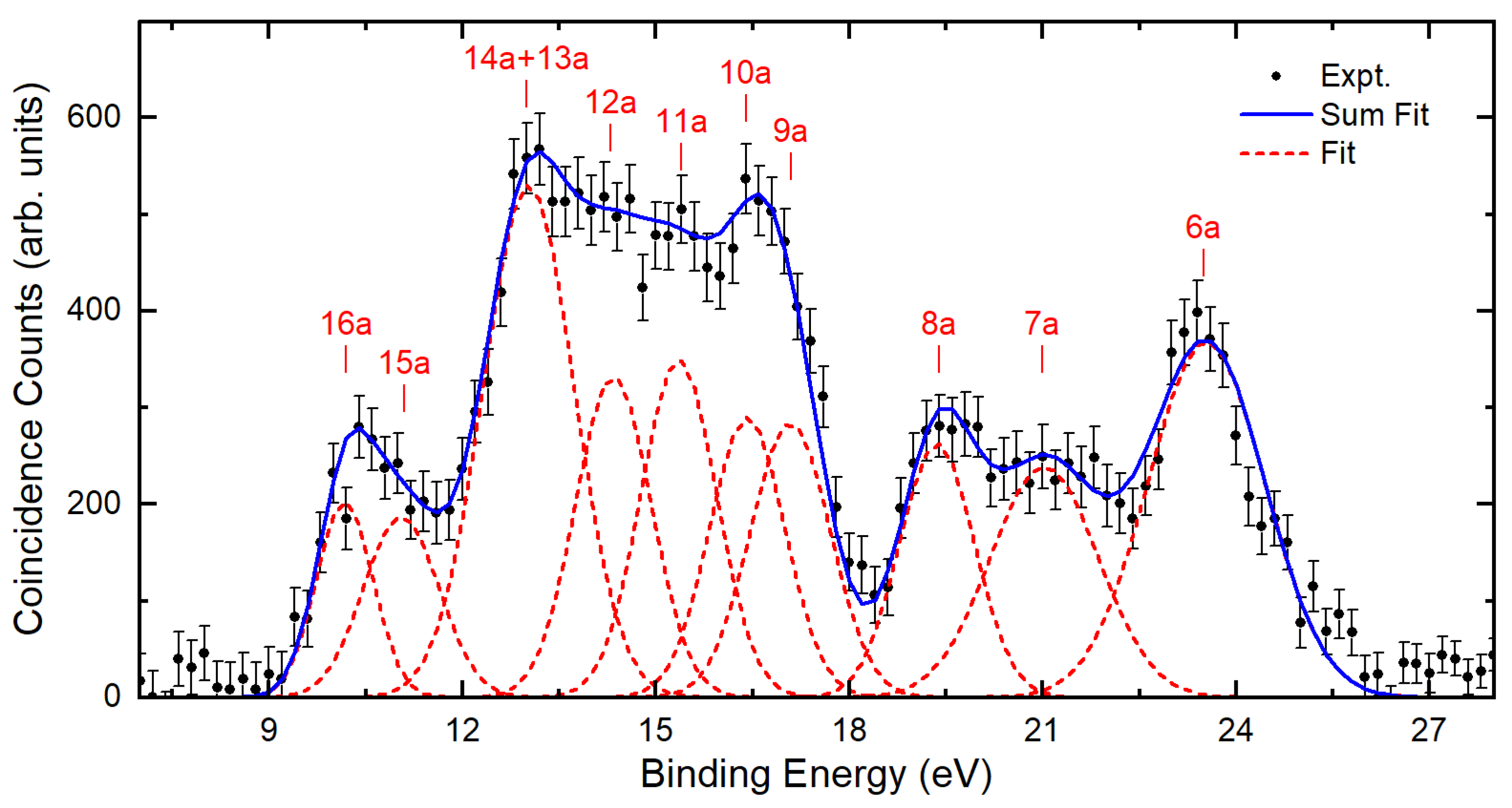

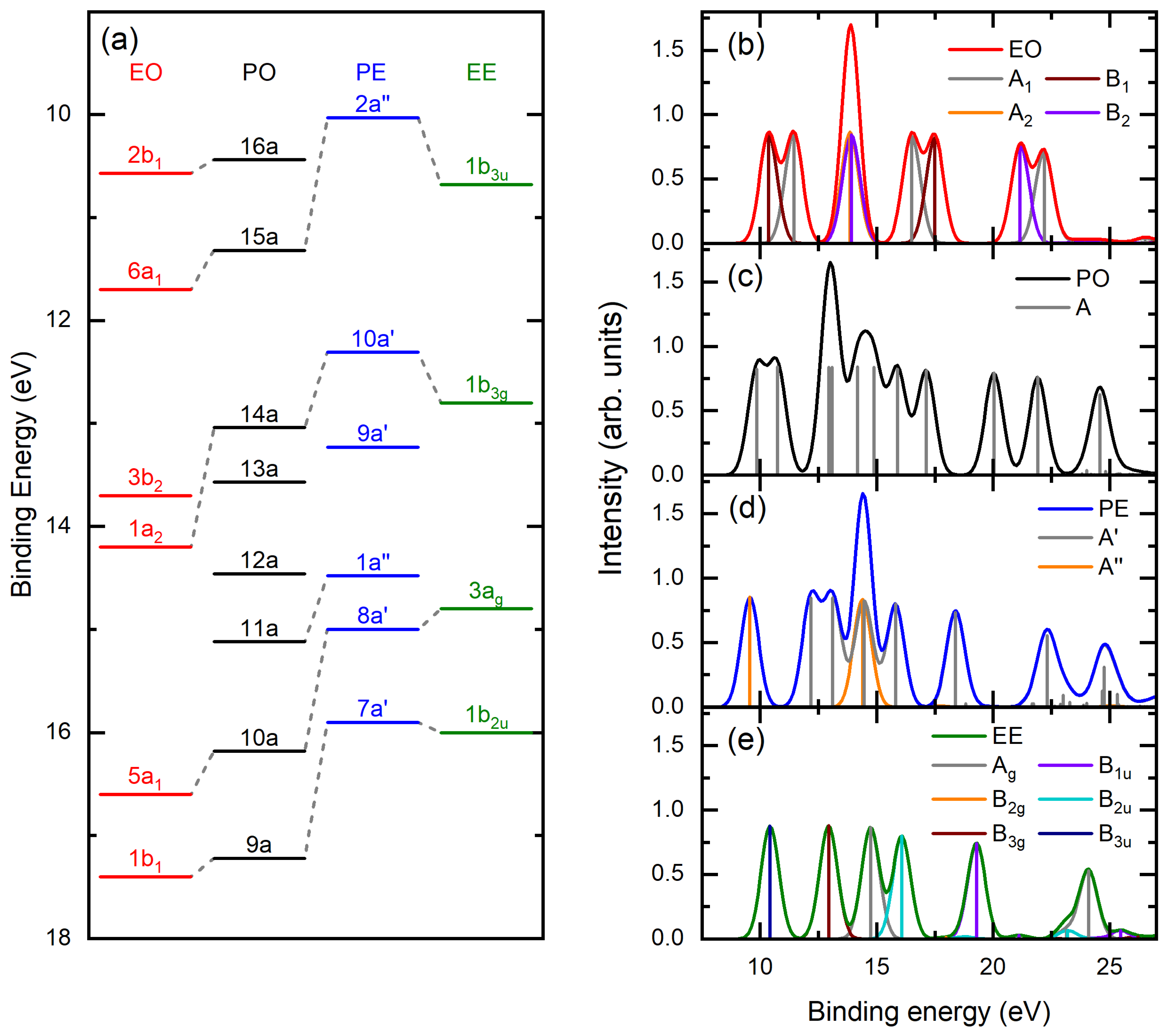

2.1. Binding Energy Spectra

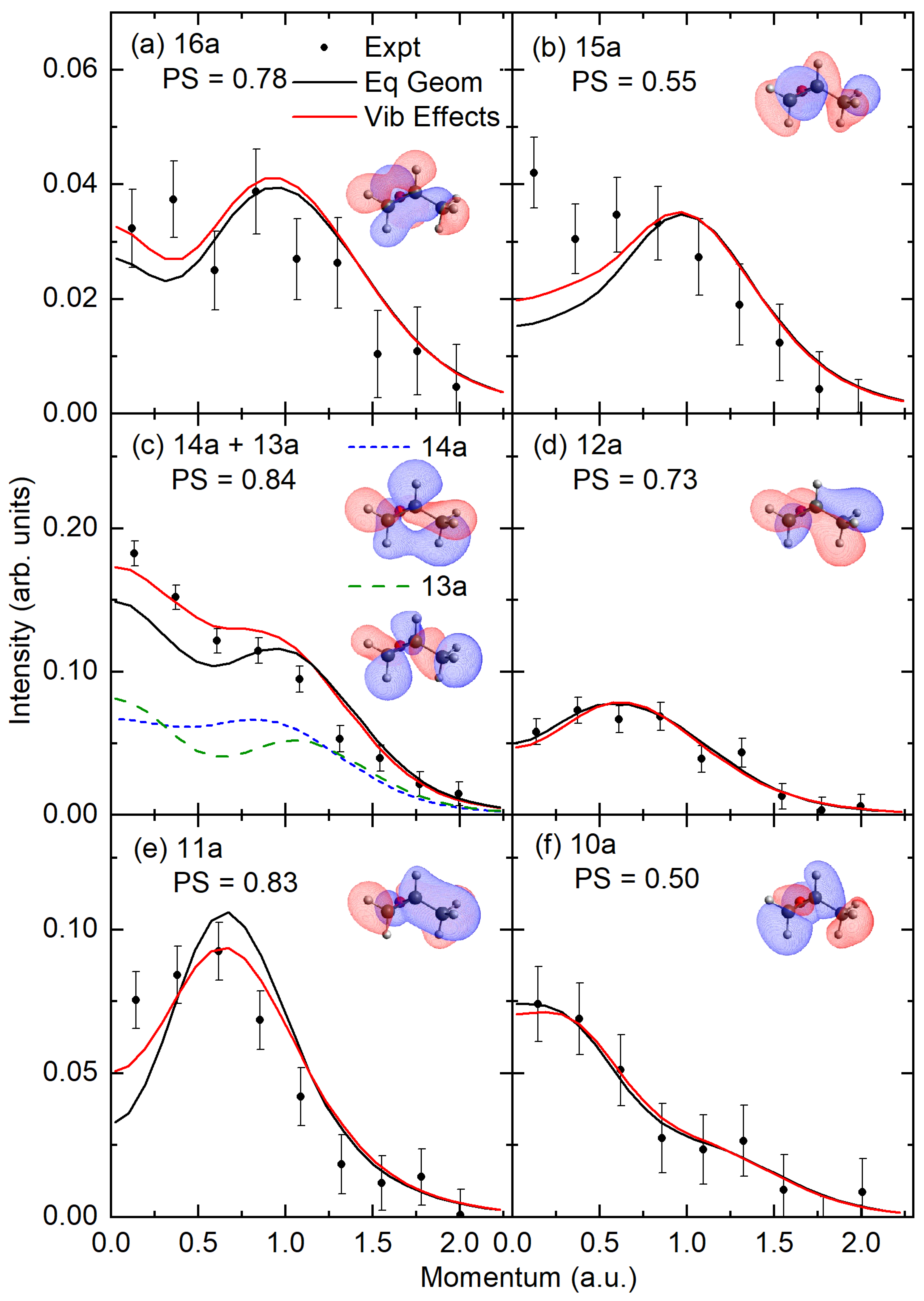

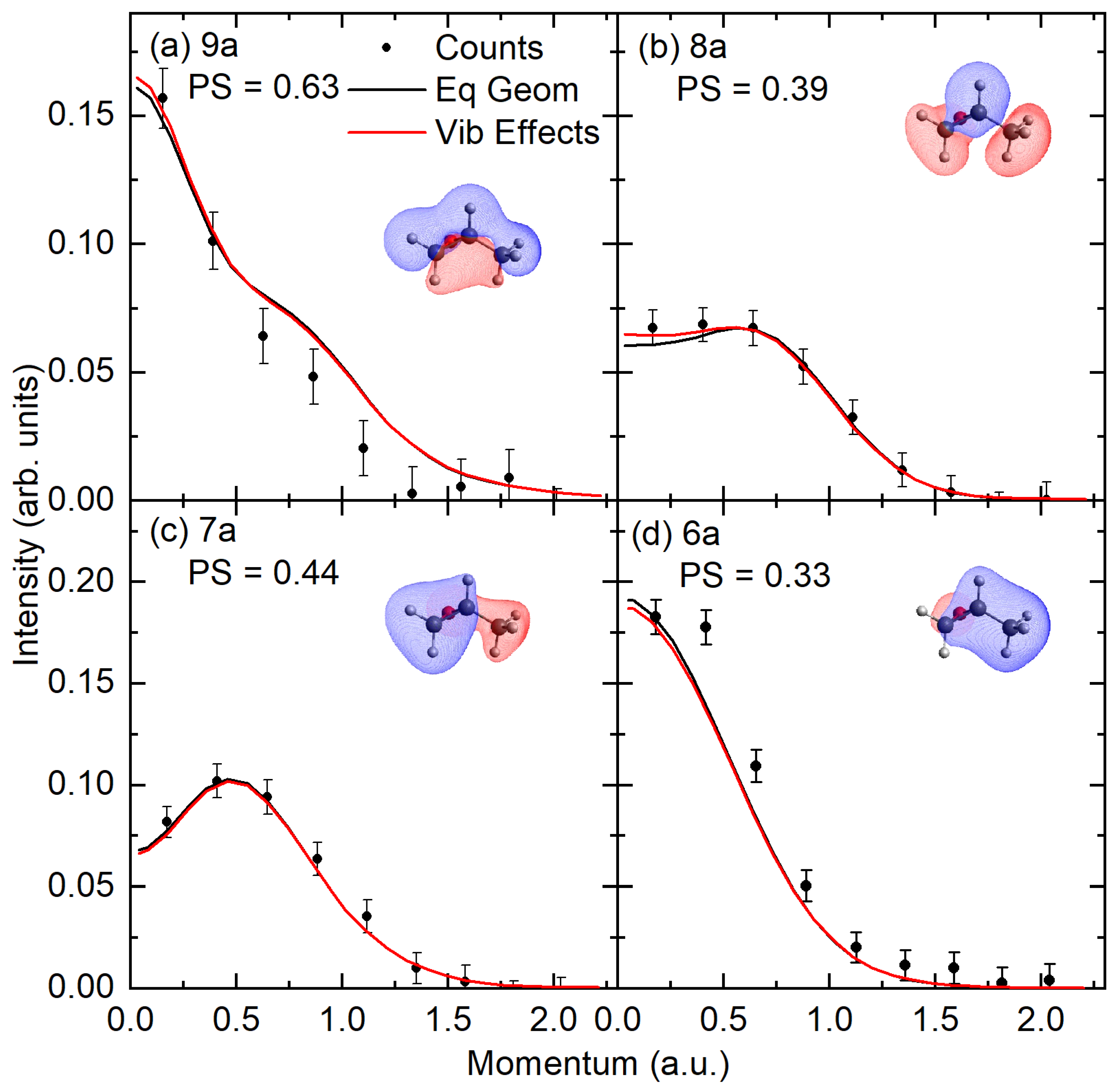

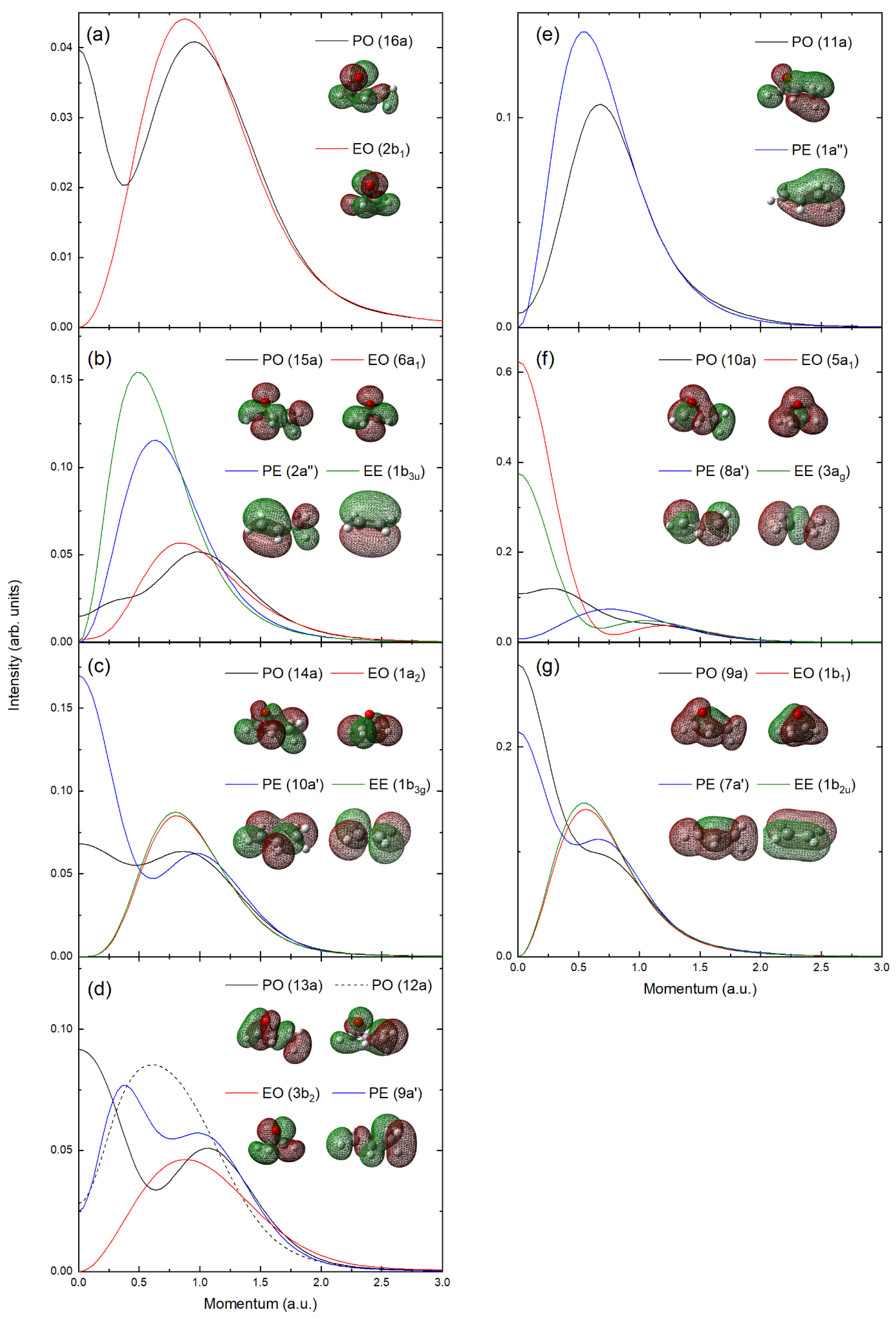

2.2. Experimental and Theoretical Momentum Distributions

2.3. Orbital Correlations

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DFT | density functional theory |

| EE | ethene |

| EMS | electron momentum spectroscopy |

| EO | ethylene oxide |

| HOMO | highest occupied molecular orbital |

| IE | ionization energy |

| ISM | interstellar medium |

| MD | momentum distribution |

| NHOMO | next highest occupied molecular orbital |

| OVGF | outer valence Green’s function |

| PE | propene |

| PES | photoelectron spectrum |

| PO | propylene oxide |

| PS | pole strength |

| PWIA | plane wave impulse approximation |

| SAC-CI | symmetry-adapted cluster configuration interaction |

References

- Woodward, R.B.; Hoffmann, R. Stereochemistry of Electrocyclic Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pross, A. What Is Life?: How Chemistry Becomes Biology, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press, Incorporated: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Devínsky, F. Chirality and the Origin of Life. Symmetry 2021, 13, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IceCube, C.; Aartsen, M.G.; Abraham, K.; Ackermann, M.; Adams, J.; Aguilar, J.A.; Ahlers, M.; Ahrens, M.; Altmann, D.; Andeen, K.; et al. Searches for Sterile Neutrinos with the IceCube Detector. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117, 071801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, N.; Takata, T.; Fujii, N.; Aki, K.; Sakaue, H. D-Amino acids in protein: The mirror of life as a molecular index of aging. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2018, 1866, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, B.A.; Carroll, P.B.; Loomis, R.A.; Finneran, I.A.; Jewell, P.R.; Remijan, A.J.; Blake, G.A. Discovery of the interstellar chiral molecule propylene oxide (CH3CHCH2O). Science 2016, 352, 1449–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellinger, Y.; Pauzat, F.; Markovits, A.; Allaire, A.; Guillemin, J.C. The quest of chirality in the interstellar medium. I. Lessons of propylene oxide detection. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 633, A49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.L.; Loeffler, M.J.; Yocum, K.M. Laboratory investigations into the spectra and origin of propylene oxide: A chiral interstellar molecule. Astrophys. J. 2017, 835, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunahori, F.X.; Su, Z.; Kang, C.; Xu, Y. Infrared diode laser spectroscopic investigation of four C—H stretching vibrational modes of propylene oxide. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010, 494, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vávra, K.; Döring, E.; Jakob, J.; Peterß, F.; Kaufmann, M.; Stahl, P.; Giesen, T.F.; Fuchs, G.W. High-resolution infrared spectra and rovibrational analysis of the v12 band of propylene oxide. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 23886–23892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.; Bou Debes, D.; Mendes, M.; Guerra, P.; Mestre, G.; Eden, S.; Cornetta, L.M.; Inglfsson, O.; da Silva, F.F. Experimental and Theoretical Study on Electron Ionization and Fragmentation of Propylene Oxide—The First Chiral Molecule Detected in the Interstellar Medium. J. Phys. Chem. A 2024, 128, 4795–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcinelli, S. Coulomb explosion and fragmentation dynamics of propylene oxide dication. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2075, 050003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wilkinson, L.; Lee, J.W.L.; Heathcote, D.; Vallance, C. Total electron ionization cross-sections for molecules of astrochemical interest. Mol. Phys. 2019, 117, 3066–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, N.; Avar, G.; Blankenheim, H.; Friederichs, W.; Giersig, M.; Weigand, E.; Halfmann, M.; Wittbecker, F.-W.; Larimer, D.-R.; Maier, U.; et al. Polyurethanes, Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kube, P.; Dong, J.; Bastardo, N.S.; Ruland, H.; Schlögl, R.; Margraf, J.T.; Reuter, K.; Trunschke, A. Green synthesis of propylene oxide directly from propane. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Martin, J.M.; Blanco-Brieva, G.; Fierro, J.L.G. Hydrogen Peroxide Synthesis: An Outlook beyond the Anthraquinone Process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 6962–6984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zádor, J.; Taatjes, C.A.; Fernandes, R.X. Kinetics of elementary reactions in low-temperature autoignition chemistry. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2011, 37, 371–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigold, E.; McCarthy, I.E. Electron Momentum Spectroscopy; Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, M. Looking at Molecular Orbitals in Three-Dimensional Form: From Dream to Reality. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 82, 751–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomons, T.W.G. Organic Chemistry; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, N.; Yamazaki, M.; Takahashi, M. Vibrational effects on valence electron momentum distributions of ethylene. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 114301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.G.; Ning, C.G.; Deng, J.K.; Zhang, S.F.; Su, G.L.; Huang, F.; Li, G.Q. Sensitive observations of orbital electron density image by electron momentum spectroscopy with different impact energies. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 404, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebone, B.P.; Neville, J.J.; Zheng, Y.; Brion, C.E.; Wang, Y.; Davidson, E.R. Valence electron momentum distributions of ethylene; comparison of EMS measurements with near Hartree-Fock limit, configuration interaction and density functional theory calculations. Chem. Phys. 1995, 196, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.G.; Ren, X.G.; Deng, J.K.; Zhang, S.F.; Su, G.L.; Zhou, H.; Li, B.; Huang, F.; Li, G.Q. Investigation of the highest occupied molecular orbital of propene by binary (e,2e) spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 402, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.G.; Ren, X.G.; Deng, J.K.; Zhang, S.F.; Su, G.L.; Huang, F.; Li, G.Q. Investigation of valence orbitals of propene by electron momentum spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2005, 122, 224302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, D.A.; Michalewicz, M.T.; Wang, F.; Brunger, M.J. Ab electron momentum spectroscopy and density functional theory investigation into the complete valence electronic structure of ethylene oxide. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 1999, 32, 3239–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunger, M.J.; Weigold, E.; Vonniessen, W. Electron Momentum Spectroscopy of Ethylene-Oxide. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 233, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlduff, E.J.; Houk, K.N. Photoelectron spectra of substituted oxiranes and thiiranes. Substituent effects on ionization potentials involving σ orbitals. Can. J. Chem. 1977, 55, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Katsuwata, S.; Achiba, Y.; Yamazaki, T.; Iwata, S. Handbook of HeI Photoelectron Spectra of Fundamental Organic Molecules; Japan Scientific Societies Press: Tokyo, Japan, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bawagan, A.D.O.; Desjardins, S.J.; Dailey, R.; Davidson, E.R. Correlation states of propene. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 4295–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, G.; Åsbrink, L. 30.4-nm He(II) photoelectron spectra of organic molecules: Part I. Hydrocarbons. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 1980, 20, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Neville, J.J.; Brion, C.E.; Wang, Y.; Davidson, E.R. An electronic structure study of acetone by electron momentum spectroscopy: A comparison with SCF, MRSD-CI and density functional theory. Chem. Phys. 1994, 188, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, T.K.; Takahashi, M.; Udagawa, Y. Electron momentum spectroscopy of the HOMO of acetone. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2006, 178, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.; Takahashi, K.; Sato, K.; Takahashi, M. Temperature-dependent electron momentum spectroscopy on the molecular orbitals of dimethyl ether. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 10258–10265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Rolke, J.; Cooper, G.; Brion, C.E. Valence orbital electron momentum distributions for dimethylsulfide: Comparison of EMS measurements with near Hartree–Fock limit and density functional theory calculations. J. Electron Spectrosc. Relat. Phenom. 2002, 123, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweig, A.; Thiel, W. Photoionization cross sections: He I and He II photoelectron spectra of saturated three-membered rings. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1973, 21, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, K.L.; Hewitt, G.; Gilbert, B.; Dunn, A.; Northeast, R.; Ellis, M.; Slaughter, D.S.; Euripides, P.; Lawrance, W.D.; Brunger, M.J. Towards electron momentum spectroscopy studies of clusters: A new apparatus. Ioniz. Correl. Polariz. At. Collis. 2006, 811, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, T.R.; Sadler, H.N. Vapor Pressure of Propylene Oxide. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1966, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.P.D.; Brion, C.E. Binary (e,2e) spectroscopy and momentum-space chemistry of CO2. Chem. Phys. 1982, 69, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.; Yamazaki, M.; Takahashi, M. Vibrational effects on valence electron momentum distributions of CH2F2. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 244314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T.H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, R.A.; Dunning, T.H.; Harrison, R.J. Electron affinities of the first-row atoms revisited. Systematic basis sets and wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1992, 96, 6796–6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Niessen, W.; Schirmer, J.; Cederbaum, L.S. Computational methods for the one-particle green’s function. Comput. Phys. Rep. 1984, 1, 57–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuji, H. SAC-CI Method: Theoretical Aspects and Some Recent Topics. In Computational Chemistry: Reviews of Current Trends; World Scientific: Singapore, 1997; Volume 2, pp. 62–124. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision B.01; Gaussian Inc.: Wallington, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision C.02; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Flinders University. DeepThought (HPC); Flinders University: Adelaide, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, P.; Cassida, M.E.; Brion, C.E.; Chong, D.P. Assessment of Gaussian-weighted angular resolution functions in the comparison of quantum-mechanically calculated electron momentum distributions with experiment. Chem. Phys. 1992, 159, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Assignment $ | Present EMS | PES [30] | PES [29] | ωB97X-D/ aug-cc-pVTZ | OVGF/ aug-cc-pVTZ $ | SAC-CI/6-311G** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE (eV) | IE (eV) | IE (eV) | IE (eV) | IE (eV) | PS | IE (eV) | PS # | Dominant Configurations $ | |

| 16a | 10.2 | 10.44 | 10.26 | 9.74 | 10.89 | 0.90 | 9.85 | 0.82 | 0.88(15a)−1 + 0.36(16a)−1 |

| 15a | 11.1 | 11.32 | 11.23 | 10.51 | 11.16 | 0.91 | 10.73 | 0.84 | −0.89(16a)−1 + 0.36(15a)−1 |

| 14a | 13.0 | 13.04 | 12.88 | 12.32 | 13.36 | 0.91 | 12.93 | 0.84 | 0.95(14a)−1 + 0.17(13a)−1 |

| 13a | 13.0 | 13.57 | 13.33 | 12.57 | 13.43 | 0.91 | 13.09 | 0.84 | −0.95(13a)−1 + 0.17(14a)−1 |

| 12a | 14.3 | 14.46 | 13.41 | 14.54 | 0.91 | 14.18 | 0.84 | 0.96(12a)−1 | |

| 11a | 15.4 | 15.12 | 14.08 | 15.19 | 0.91 | 14.87 | 0.84 | −0.96(11a)−1 | |

| 10a | 16.4 | 16.18 | 15.25 | 16.17 | 0.90 | 15.89 | 0.82 | −0.95(10a)−1 | |

| 9a | 17.1 | 17.22 | 16.41 | 17.41 | 0.90 | 17.12 | 0.81 | −0.94(9a)−1 | |

| 8a | 19.4 | 19.65 | 18.88 | 20.03 | 0.79 | 0.94(8a)−1 | |||

| 7a | 21.0 | 20.67 | 21.92 | 0.76 | −0.92(7a)−1 | ||||

| 6a | 23.5 | 23.09 | 24.56 | 0.63 | −0.83(6a)−1 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matalon, D.G.; Nixon, K.L.; Jones, D.B. The Influence of Chemical Structure on the Electronic Structure of Propylene Oxide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311729

Matalon DG, Nixon KL, Jones DB. The Influence of Chemical Structure on the Electronic Structure of Propylene Oxide. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311729

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatalon, David G., Kate L. Nixon, and Darryl B. Jones. 2025. "The Influence of Chemical Structure on the Electronic Structure of Propylene Oxide" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311729

APA StyleMatalon, D. G., Nixon, K. L., & Jones, D. B. (2025). The Influence of Chemical Structure on the Electronic Structure of Propylene Oxide. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311729