Characterization of the Regulatory AAA-ATPase Subunit Rpt3 in Plasmodium berghei as an Activator of Protein Phosphatase 1

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

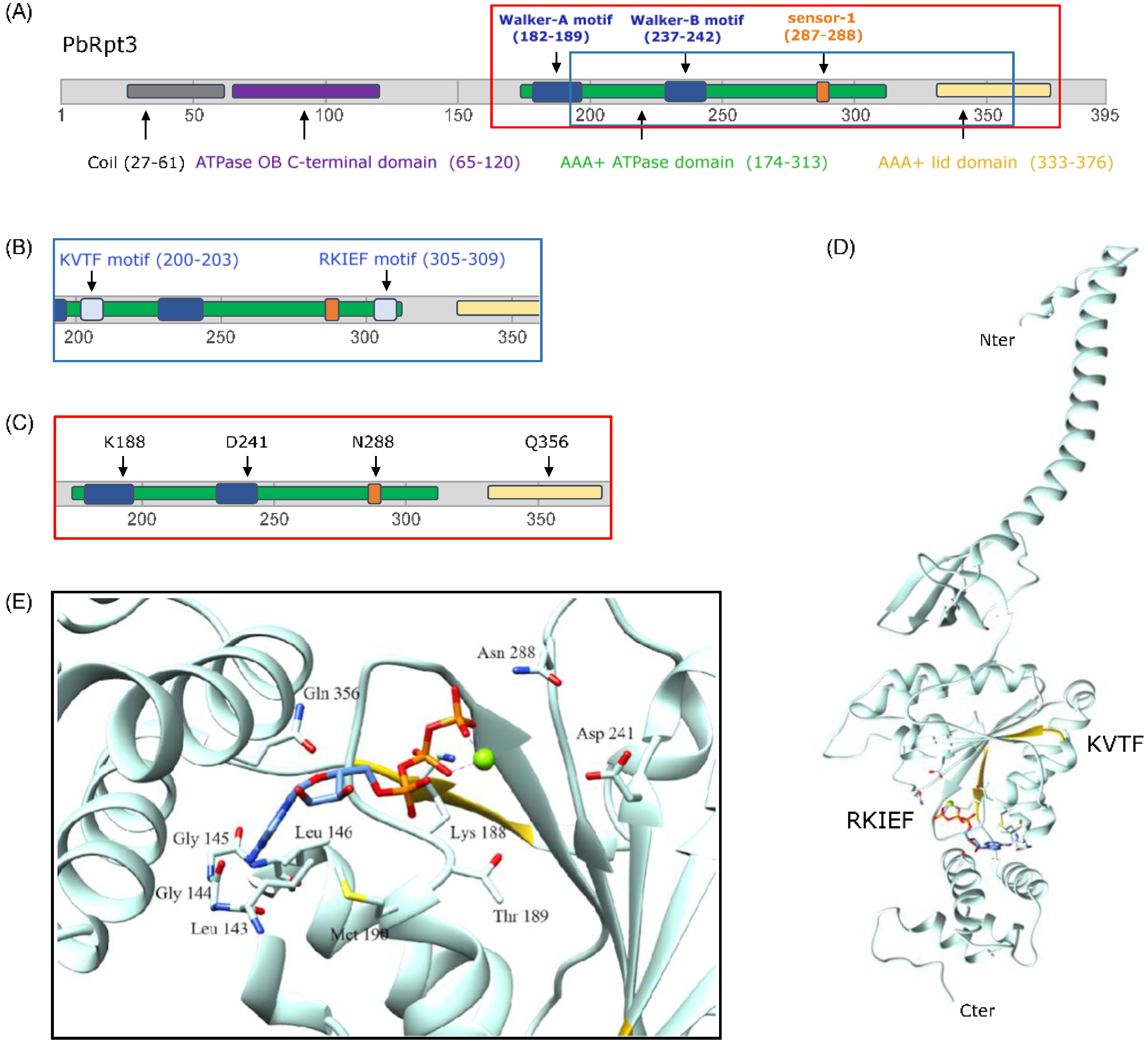

2.1. PbRpt3 Sequence Analysis and Protein Annotation

2.2. PbRpt3 Exhibits ATP-Binding Ability and Would Require a Mg2+ Ion for Complex Stability

2.3. PbRpt3 Could Interact with PP1c Independently of the Proteasome Complex

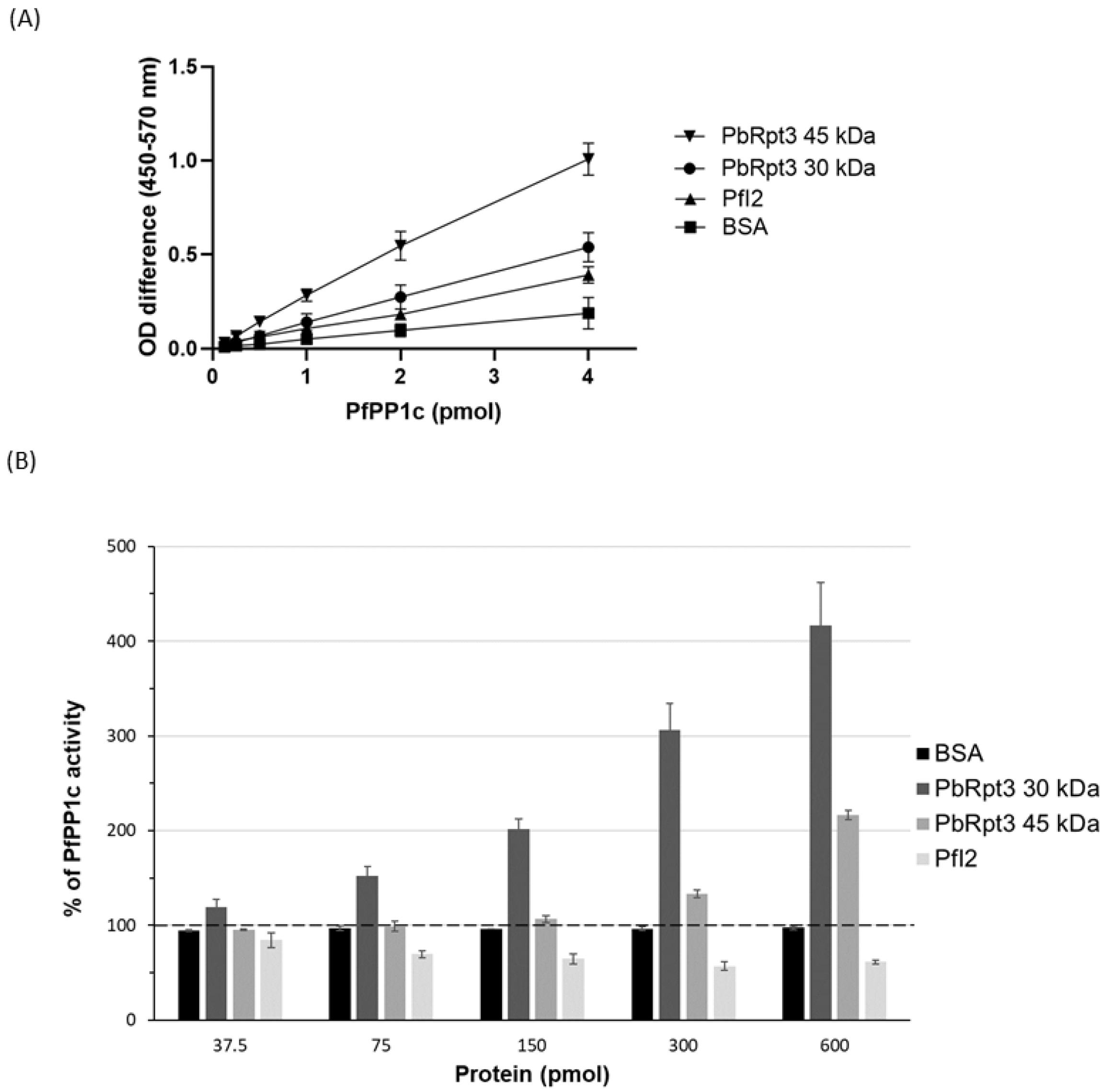

2.4. His-Tagged PbRpt3 Protein Directly Interacts with PP1c and Regulates Its Activity

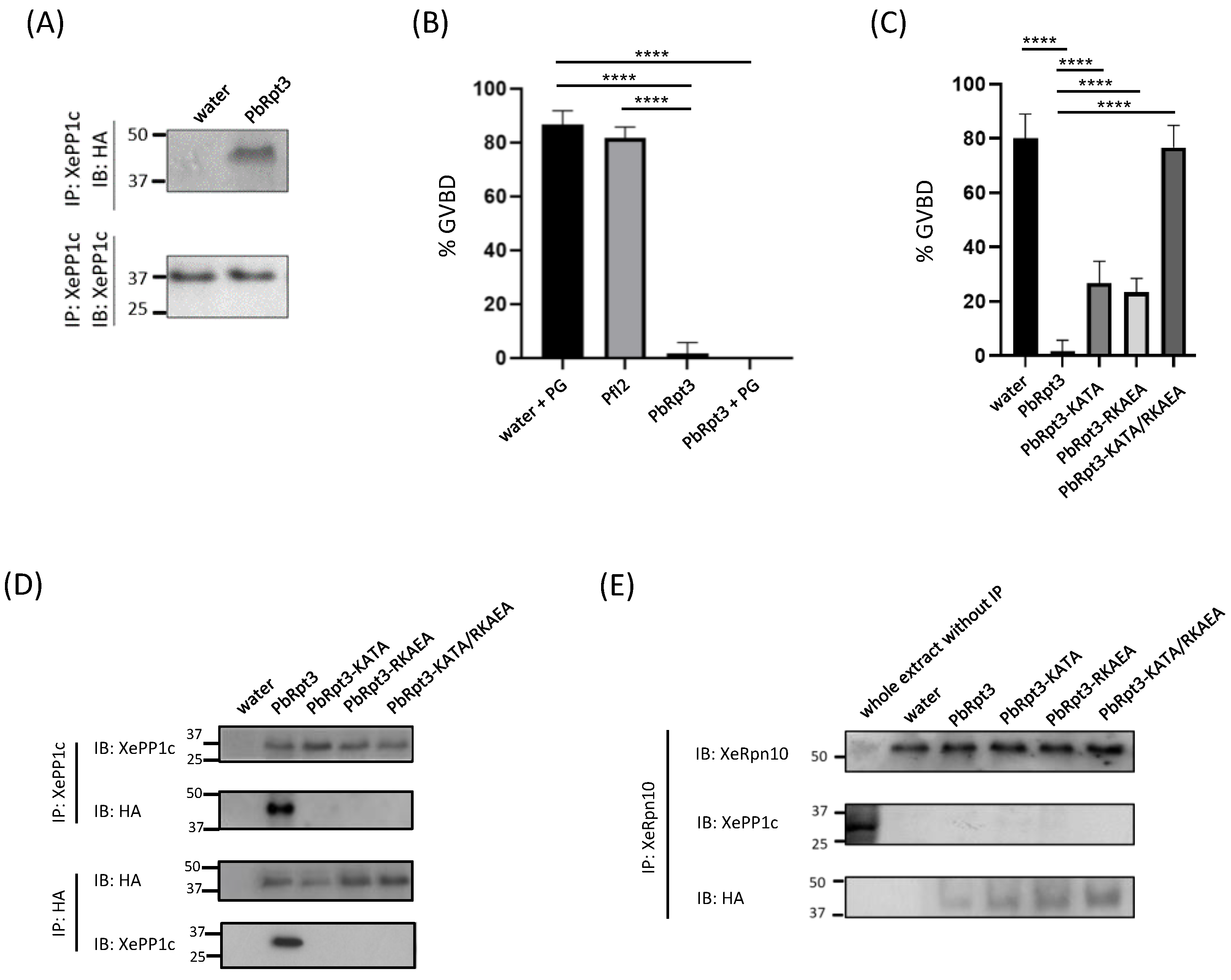

2.5. PbRpt3 Binds to PP1c Outside the Proteasome and Shows Functional Activity in Xenopus Oocytes

2.6. PbRpt3 RVxF Motifs Are Crucial for PP1c Binding and Functional Activity in Xenopus Oocytes

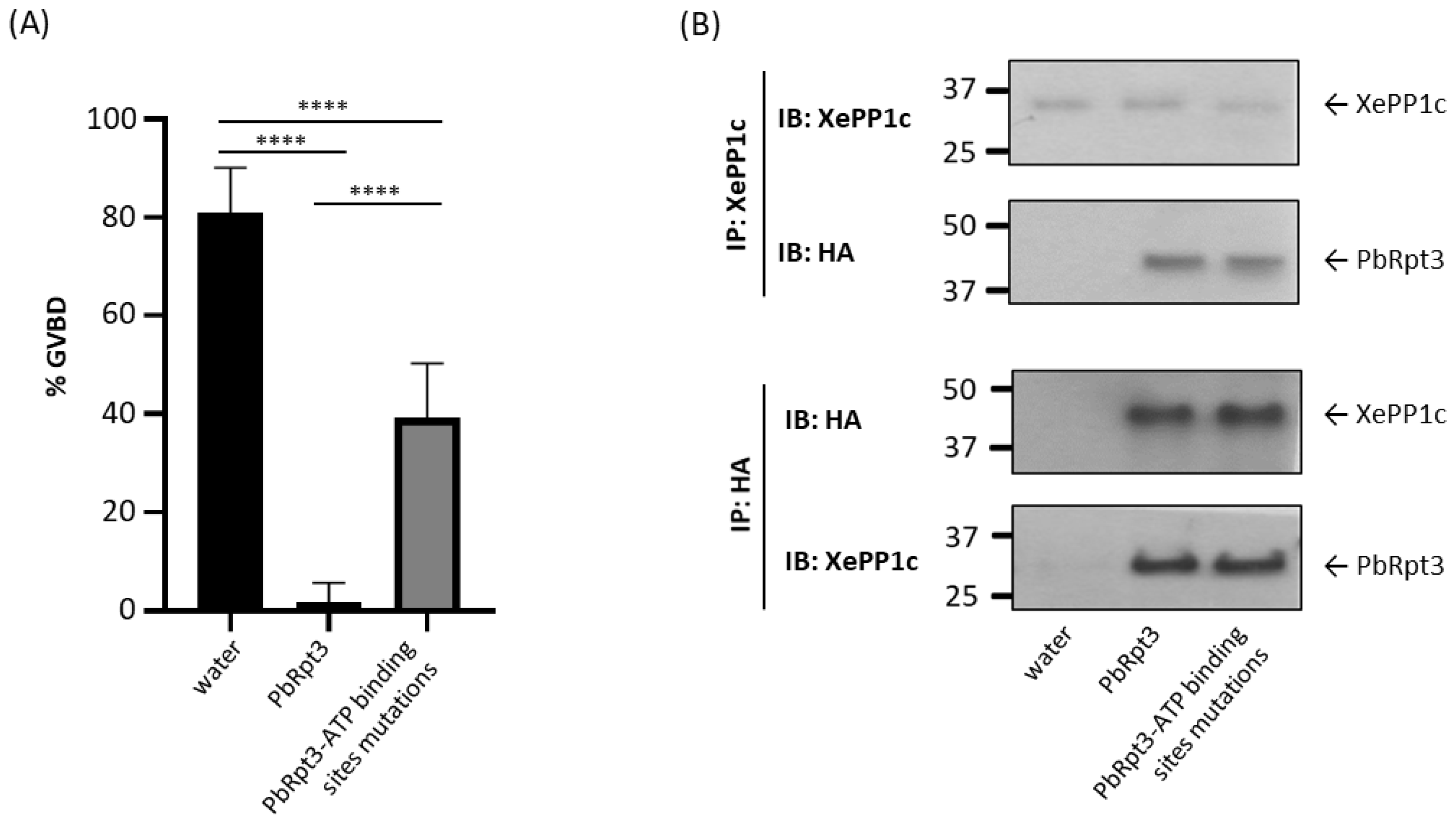

2.7. The ATP-Binding Capacity of PbRpt3 Is Involved in the Activation of XePP1c

2.8. PbRpt3 May Be Essential During the Blood Stage Life Cycle of P. berghei

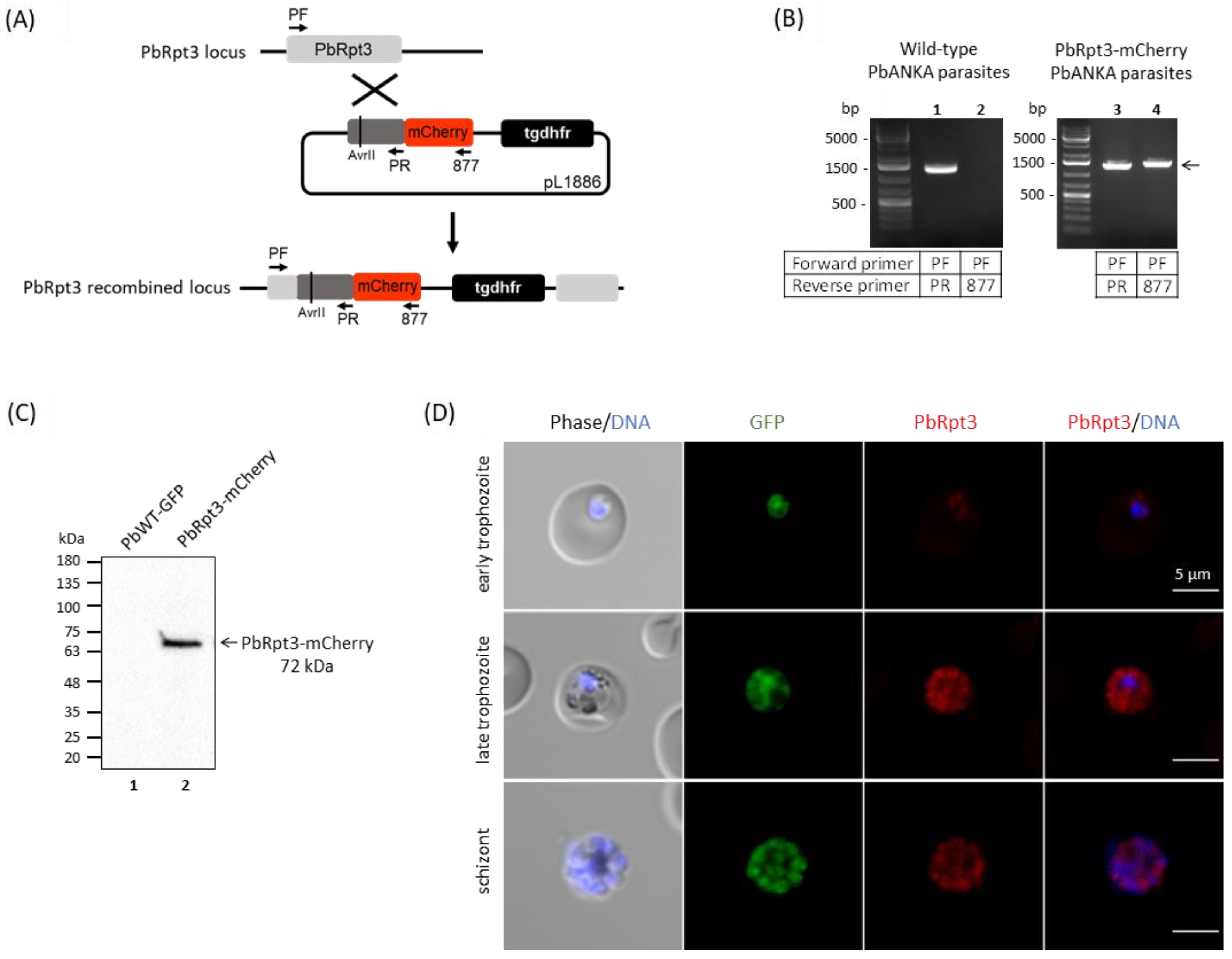

2.9. Localization of PbRpt3 in P. berghei

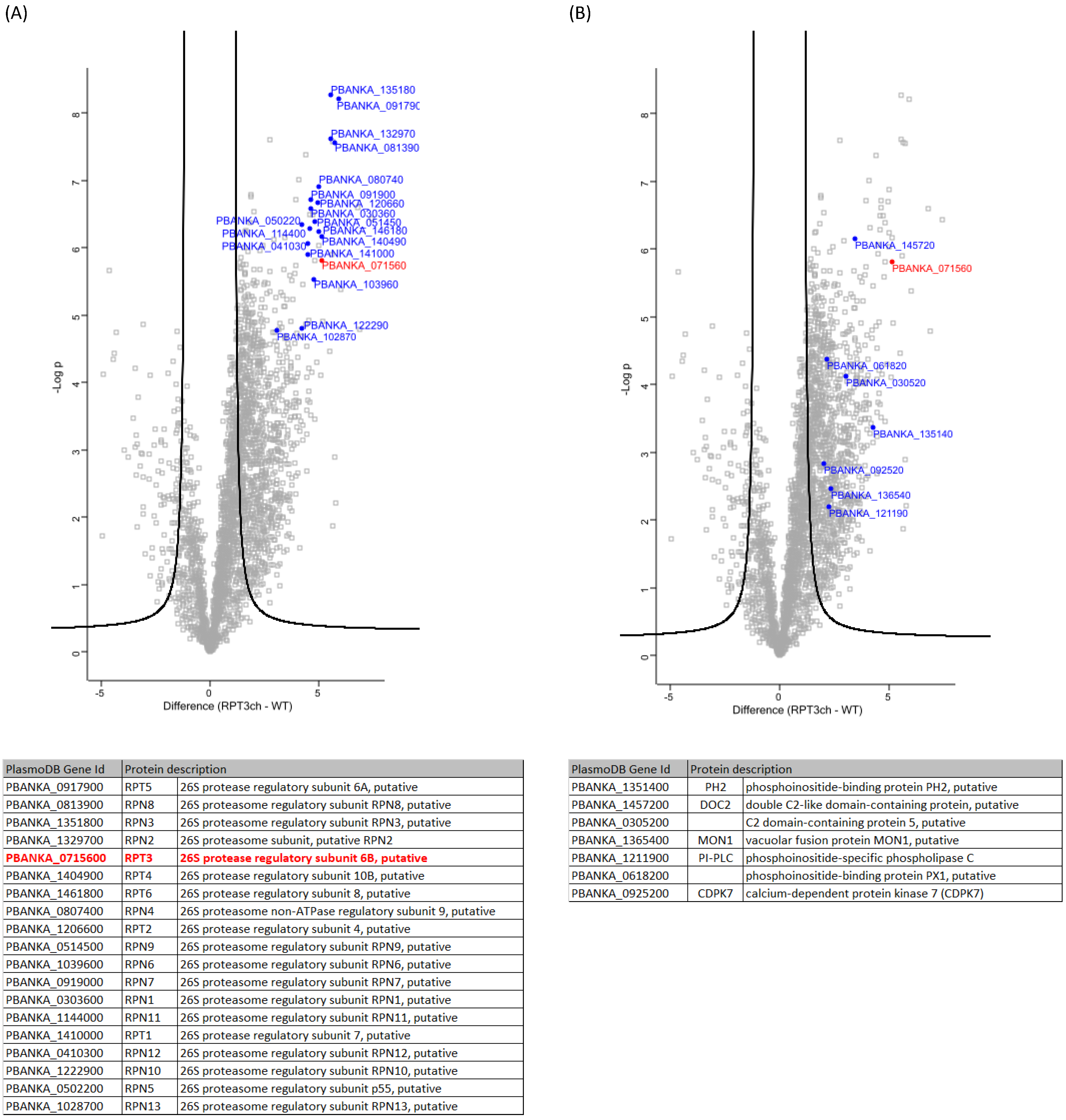

2.10. PbRpt3 Interacts with the 19S Proteasome Complex

2.11. Conclusions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Ethics Statement

3.2. Animals

3.3. PbRpt3 Sequence Analysis and Molecular Modeling

3.4. Plasmids and Directed Mutagenesis

3.5. Recombinant Protein Expression

3.6. Measurement of Binding of PbRpt3 to PP1c

3.7. Assays for Effects of PbRpt3 on PfPP1 Activity

3.8. Analysis of Xenopus Oocytes GVBD and Protein Immunoprecipitation

3.9. Isolation of Parasites Stages

3.10. Generation of Transgenic Parasites

3.11. Immunofluorescence Assays

3.12. Immunoprecipitation

3.13. Sample Preparation for Mass Spectrometry

3.14. NanoLC-MS/MS Protein Identification and Quantification

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pickart, C.M.; Cohen, R.E. Proteasomes and Their Kin: Proteases in the Machine Age. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enenkel, C.; Kang, R.W.; Wilfling, F.; Ernst, O.P. Intracellular Localization of the Proteasome in Response to Stress Conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, C.; DeMartino, G.N. Intracellular Localization of Proteasomes. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2003, 35, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X. Localized Proteasomal Degradation: From the Nucleus to Cell Periphery. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Delahunty, C.; Fritz-Wolf, K.; Rahlfs, S.; Helena Prieto, J.; Yates, J.R.; Becker, K. Characterization of the 26S Proteasome Network in Plasmodium Falciparum. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, V.; Oksman, A.; Iwamoto, M.; Wandless, T.J.; Goldberg, D.E. Asparagine Repeat Function in a Plasmodium Falciparum Protein Assessed via a Regulatable Fluorescent Affinity Tag. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4411–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, K.M.; Williamson, K.C. The Proteasome as a Target to Combat Malaria: Hits and Misses. Transl. Res. 2018, 198, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogovski, C.; Xie, S.C.; Burgio, G.; Bridgford, J.; Mok, S.; McCaw, J.M.; Chotivanich, K.; Kenny, S.; Gnädig, N.; Straimer, J.; et al. Targeting the Cell Stress Response of Plasmodium Falciparum to Overcome Artemisinin Resistance. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgford, J.L.; Xie, S.C.; Cobbold, S.A.; Pasaje, C.F.A.; Herrmann, S.; Yang, T.; Gillett, D.L.; Dick, L.R.; Ralph, S.A.; Dogovski, C.; et al. Artemisinin Kills Malaria Parasites by Damaging Proteins and Inhibiting the Proteasome. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Bogyo, M.; da Fonseca, P.C.A. The Cryo-EM Structure of the Plasmodium Falciparum 20S Proteasome and Its Use in the Fight against Malaria. FEBS J. 2016, 283, 4238–4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, M.; Taverner, T.; Ambroggio, X.I.; Deshaies, R.J.; Robinson, C.V. Structural Organization of the 19S Proteasome Lid: Insights from MS of Intact Complexes. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjappu, M.J.; Hochstrasser, M. Assembly of the 20S Proteasome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollin, T.; De Witte, C.; Fréville, A.; Guerrera, I.C.; Chhuon, C.; Saliou, J.-M.; Herbert, F.; Pierrot, C.; Khalife, J. Essential Role of GEXP15, a Specific Protein Phosphatase Type 1 Partner, in Plasmodium Berghei in Asexual Erythrocytic Proliferation and Transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Witte, C.; Aliouat, E.M.; Chhuon, C.; Guerrera, I.C.; Pierrot, C.; Khalife, J. Mapping PP1c and Its Inhibitor 2 Interactomes Reveals Conserved and Specific Networks in Asexual and Sexual Stages of Plasmodium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, D.; Saito-Ito, A.; Asao, N.; Tanabe, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Matsumura, T. Modulation of the Growth ofPlasmodium Falciparum in Vitroby Protein Serine/Threonine Phosphatase Inhibitors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 247, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttery, D.S.; Poulin, B.; Ramaprasad, A.; Wall, R.J.; Ferguson, D.J.P.; Brady, D.; Patzewitz, E.-M.; Whipple, S.; Straschil, U.; Wright, M.H.; et al. Genome-Wide Functional Analysis of Plasmodium Protein Phosphatases Reveals Key Regulators of Parasite Development and Differentiation. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 16, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.S.; Miliu, A.; Paulo, J.A.; Goldberg, J.M.; Bonilla, A.M.; Berry, L.; Seveno, M.; Braun-Breton, C.; Kosber, A.L.; Elsworth, B.; et al. Co-Option of Plasmodium Falciparum PP1 for Egress from Host Erythrocytes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seveno, M.; Loubens, M.N.; Berry, L.; Graindorge, A.; Lebrun, M.; Lavazec, C.; Lamarque, M.H. The Malaria Parasite PP1 Phosphatase Controls the Initiation of the Egress Pathway of Asexual Blood-Stages by Regulating the Rounding-up of the Vacuole. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, M. Combinatorial Control of Protein Phosphatase-1. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2001, 26, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceulemans, H.; Bollen, M. Functional Diversity of Protein Phosphatase-1, a Cellular Economizer and Reset Button. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardilha, M.; Esteves, S.L.C.; Korrodi-Gregório, L.; da Cruz e Silva, O.a.B.; da Cruz e Silva, F.F. The Physiological Relevance of Protein Phosphatase 1 and Its Interacting Proteins to Health and Disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 3996–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, A.; Beullens, M.; Ceulemans, H.; Den Abt, T.; Van Eynde, A.; Nicolaescu, E.; Lesage, B.; Bollen, M. Docking Motif-Guided Mapping of the Interactome of Protein Phosphatase-1. Chem. Biol. 2009, 16, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, M.; Peti, W.; Ragusa, M.J.; Beullens, M. The Extended PP1 Toolkit: Designed to Create Specificity. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010, 35, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, M.S.; Hieke, M.; Kumar, G.S.; Lewis, G.R.; Gonzalez-DeWhitt, K.R.; Kessler, R.P.; Stein, B.J.; Hessenberger, M.; Nairn, A.C.; Peti, W.; et al. Understanding the Antagonism of Retinoblastoma Protein Dephosphorylation by PNUTS Provides Insights into the PP1 Regulatory Code. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4097–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, W.; Browaeys, E.; Pierrot, C.; Jouin, H.; Dive, D.; Meurice, E.; Dissous, C.; Capron, M.; Tomavo, S.; Doerig, C.; et al. Regulation of Protein Phosphatase Type 1 and Cell Cycle Progression by PfLRR1, a Novel Leucine-Rich Repeat Protein of the Human Malaria Parasite Plasmodium Falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 578–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fréville, A.; Landrieu, I.; García-Gimeno, M.A.; Vicogne, J.; Montbarbon, M.; Bertin, B.; Verger, A.; Kalamou, H.; Sanz, P.; Werkmeister, E.; et al. Plasmodium Falciparum Inhibitor-3 Homolog Increases Protein Phosphatase Type 1 Activity and Is Essential for Parasitic Survival*. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 1306–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fréville, A.; Cailliau-Maggio, K.; Pierrot, C.; Tellier, G.; Kalamou, H.; Lafitte, S.; Martoriati, A.; Pierce, R.J.; Bodart, J.-F.; Khalife, J. Plasmodium Falciparum Encodes a Conserved Active Inhibitor-2 for Protein Phosphatase Type 1: Perspectives for Novel Anti-Plasmodial Therapy. BMC Biol. 2013, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenne, A.; De Witte, C.; Tellier, G.; Hollin, T.; Aliouat, E.M.; Martoriati, A.; Cailliau, K.; Saliou, J.-M.; Khalife, J.; Pierrot, C. Characterization of a Protein Phosphatase Type-1 and a Kinase Anchoring Protein in Plasmodium Falciparum. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedidi, R.S.; Wendler, P.; Enenkel, C. AAA-ATPases in Protein Degradation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendler, P.; Ciniawsky, S.; Kock, M.; Kube, S. Structure and Function of the AAA+ Nucleotide Binding Pocket. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA—Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1823, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonin, E.V. A Common Set of Conserved Motifs in a Vast Variety of Putative Nucleic Acid-Dependent ATPases Including MCM Proteins Involved in the Initiation of Eukaryotic DNA Replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 2541–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inobe, T.; Genmei, R. N-Terminal Coiled-Coil Structure of ATPase Subunits of 26S Proteasome Is Crucial for Proteasome Function. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, W.L.; Zhu, Y.; Stoilova-McPhie, S.; Lu, Y.; Finley, D.; Mao, Y. Cryo-EM Structures and Dynamics of Substrate-Engaged Human 26S Proteasome. Nature 2019, 565, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraste, M.; Sibbald, P.R.; Wittinghofer, A. The P-Loop—A Common Motif in ATP- and GTP-Binding Proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1990, 15, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Story, R.M.; Steitz, T.A. Structure of the recA Protein-ADP Complex. Nature 1992, 355, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattendorf, D.A.; Lindquist, S.L. Cooperative Kinetics of Both Hsp104 ATPase Domains and Interdomain Communication Revealed by AAA Sensor-1 Mutants. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalife, J.; Fréville, A.; Gnangnon, B.; Pierrot, C. The Multifaceted Role of Protein Phosphatase 1 in Plasmodium. Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellier, G.; Lenne, A.; Cailliau-Maggio, K.; Cabezas-Cruz, A.; Valdés, J.J.; Martoriati, A.; Aliouat, E.M.; Gosset, P.; Delaire, B.; Fréville, A.; et al. Identification of Plasmodium Falciparum Translation Initiation eIF2β Subunit: Direct Interaction with Protein Phosphatase Type 1. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchon, D.; Ozon, R.; Demaille, J.G. Protein Phosphatase-1 Is Involved in Xenopus Oocyte Maturation. Nature 1981, 294, 358–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveraux, Q.; Ustrell, V.; Pickart, C.; Rechsteiner, M. A 26 S Protease Subunit That Binds Ubiquitin Conjugates. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 7059–7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedinger, C.; Boehringer, J.; Trempe, J.-F.; Lowe, E.D.; Brown, N.R.; Gehring, K.; Noble, M.E.M.; Gordon, C.; Endicott, J.A. Structure of Rpn10 and Its Interactions with Polyubiquitin Chains and the Proteasome Subunit Rpn12. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 33992–34003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, C.R.; Ferrell, K.; Penney, M.; Wallace, M.; Dubiel, W.; Gordon, C. Analysis of a Gene Encoding Rpn10 of the Fission Yeast Proteasome Reveals That the Polyubiquitin-Binding Site of This Subunit Is Essential When Rpn12/Mts3 Activity Is Compromised. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 15182–15192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egloff, M.P.; Johnson, D.F.; Moorhead, G.; Cohen, P.T.; Cohen, P.; Barford, D. Structural Basis for the Recognition of Regulatory Subunits by the Catalytic Subunit of Protein Phosphatase 1. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 1876–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakula, P.; Beullens, M.; Ceulemans, H.; Stalmans, W.; Bollen, M. Degeneracy and Function of the Ubiquitous RVXF Motif That Mediates Binding to Protein Phosphatase-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 18817–18823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushell, E.; Gomes, A.R.; Sanderson, T.; Anar, B.; Girling, G.; Herd, C.; Metcalf, T.; Modrzynska, K.; Schwach, F.; Martin, R.E.; et al. Functional Profiling of a Plasmodium Genome Reveals an Abundance of Essential Genes. Cell 2017, 170, 260–272.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Otto, T.D.; Oberstaller, J.; Liao, X.; Adapa, S.R.; Udenze, K.; Bronner, I.F.; Casandra, D.; Mayho, M.; et al. Uncovering the Essential Genes of the Human Malaria Parasite Plasmodium Falciparum by Saturation Mutagenesis. Science 2018, 360, eaap7847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; O’Donoghue, A.J.; van der Linden, W.A.; Xie, S.C.; Yoo, E.; Foe, I.T.; Tilley, L.; Craik, C.S.; da Fonseca, P.C.A.; Bogyo, M. Structure- and Function-Based Design of Plasmodium-Selective Proteasome Inhibitors. Nature 2016, 530, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toenhake, C.G.; Fraschka, S.A.-K.; Vijayabaskar, M.S.; Westhead, D.R.; van Heeringen, S.J.; Bártfai, R. Chromatin Accessibility-Based Characterization of the Gene Regulatory Network Underlying Plasmodium Falciparum Blood-Stage Development. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 557–569.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, D.; Salin, B.; Daignan-Fornier, B.; Sagot, I. Reversible Cytoplasmic Localization of the Proteasome in Quiescent Yeast Cells. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 181, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tsu, C.; Blackburn, C.; Li, G.; Hales, P.; Dick, L.; Bogyo, M. Identification of Potent and Selective Non-Covalent Inhibitors of the Plasmodium Falciparum Proteasome. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 13562–13565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh, Z.; Mukherjee, A.; Crochetière, M.-È.; Sergerie, A.; Amiar, S.; Thompson, L.A.; Gagnon, D.; Gaumond, D.; Stahelin, R.V.; Dacks, J.B.; et al. A Pan-Apicomplexan Phosphoinositide-Binding Protein Acts in Malarial Microneme Exocytosis. EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e47102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, R.; Tripathi, A.; Kumar, M.; Antil, N.; Yamaryo-Botté, Y.; Kumar, P.; Bansal, P.; Doerig, C.; Botté, C.Y.; Prasad, T.S.K.; et al. PI4-Kinase and PfCDPK7 Signaling Regulate Phospholipid Biosynthesis in Plasmodium Falciparum. EMBO Rep. 2022, 23, e54022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halgren, T.A. MMFF VI. MMFF94s Option for Energy Minimization Studies. J. Comput. Chem. 1999, 20, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, W.; Oria, G.; Fauquenoy, S.; Cailliau, K.; Browaeys, E.; Tomavo, S.; Khalife, J. A Toxoplasma Gondii Leucine-Rich Repeat Protein Binds Phosphatase Type 1 Protein and Negatively Regulates Its Activity. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beetsma, A.L.; van de Wiel, T.J.; Sauerwein, R.W.; Eling, W.M. Plasmodium Berghei ANKA: Purification of Large Numbers of Infectious Gametocytes. Exp. Parasitol. 1998, 88, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.C.; Margos, G.; Compton, H.; Ku, M.; Lanz, H.; Rodríguez, M.H.; Sinden, R.E. Plasmodium Berghei: Routine Production of Pure Gametocytes, Extracellular Gametes, Zygotes, and Ookinetes. Exp. Parasitol. 2002, 101, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fréville, A.; Gnangnon, B.; Tremp, A.Z.; De Witte, C.; Cailliau, K.; Martoriati, A.; Aliouat, E.M.; Fernandes, P.; Chhuon, C.; Silvie, O.; et al. Plasmodium Berghei Leucine-Rich Repeat Protein 1 Downregulates Protein Phosphatase 1 Activity and Is Required for Efficient Oocyst Development. Open Biol. 2022, 12, 220015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, G.; Briquet, S.; Risco-Castillo, V.; Gaultier, C.; Topçu, S.; Ivănescu, M.L.; Franetich, J.-F.; Hoareau-Coudert, B.; Mazier, D.; Silvie, O. A Rapid and Robust Selection Procedure for Generating Drug-Selectable Marker-Free Recombinant Malaria Parasites. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janse, C.J.; Ramesar, J.; Waters, A.P. High-Efficiency Transfection and Drug Selection of Genetically Transformed Blood Stages of the Rodent Malaria Parasite Plasmodium Berghei. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demichev, V.; Messner, C.B.; Vernardis, S.I.; Lilley, K.S.; Ralser, M. DIA-NN: Neural Networks and Interference Correction Enable Deep Proteome Coverage in High Throughput. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Sinitcyn, P.; Carlson, A.; Hein, M.Y.; Geiger, T.; Mann, M.; Cox, J. The Perseus Computational Platform for Comprehensive Analysis of (Prote)Omics Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bai, J.; Bandla, C.; García-Seisdedos, D.; Hewapathirana, S.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Kundu, D.J.; Prakash, A.; Frericks-Zipper, A.; Eisenacher, M.; et al. The PRIDE Database Resources in 2022: A Hub for Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics Evidences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D543–D552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lainé, C.; De Witte, C.; Martoriati, A.; Farce, A.; Metatla, I.; Guerrera, I.C.; Cailliau, K.; Khalife, J.; Pierrot, C. Characterization of the Regulatory AAA-ATPase Subunit Rpt3 in Plasmodium berghei as an Activator of Protein Phosphatase 1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311720

Lainé C, De Witte C, Martoriati A, Farce A, Metatla I, Guerrera IC, Cailliau K, Khalife J, Pierrot C. Characterization of the Regulatory AAA-ATPase Subunit Rpt3 in Plasmodium berghei as an Activator of Protein Phosphatase 1. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311720

Chicago/Turabian StyleLainé, Claudianne, Caroline De Witte, Alain Martoriati, Amaury Farce, Inès Metatla, Ida Chiara Guerrera, Katia Cailliau, Jamal Khalife, and Christine Pierrot. 2025. "Characterization of the Regulatory AAA-ATPase Subunit Rpt3 in Plasmodium berghei as an Activator of Protein Phosphatase 1" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311720

APA StyleLainé, C., De Witte, C., Martoriati, A., Farce, A., Metatla, I., Guerrera, I. C., Cailliau, K., Khalife, J., & Pierrot, C. (2025). Characterization of the Regulatory AAA-ATPase Subunit Rpt3 in Plasmodium berghei as an Activator of Protein Phosphatase 1. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11720. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311720