Solid-Phase Synthesis Approaches and U-Rich RNA-Binding Activity of Homotrimer Nucleopeptide Containing Adenine Linked to L-azidohomoalanine Side Chain via 1,4-Linked-1,2,3-Triazole

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

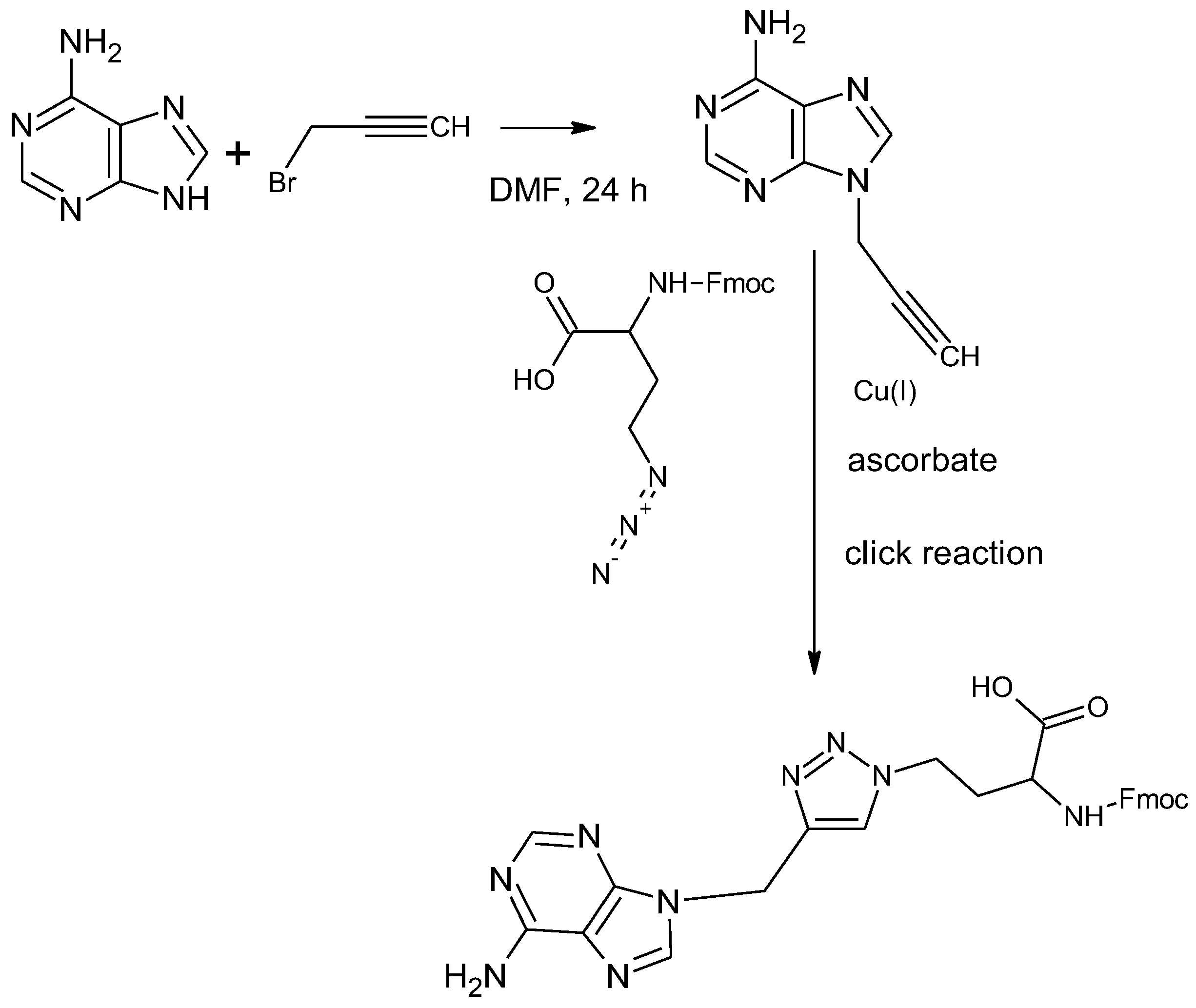

2.1. Synthesis of N9-propargyladenine and Fmoc-1,4-TzlNBAA

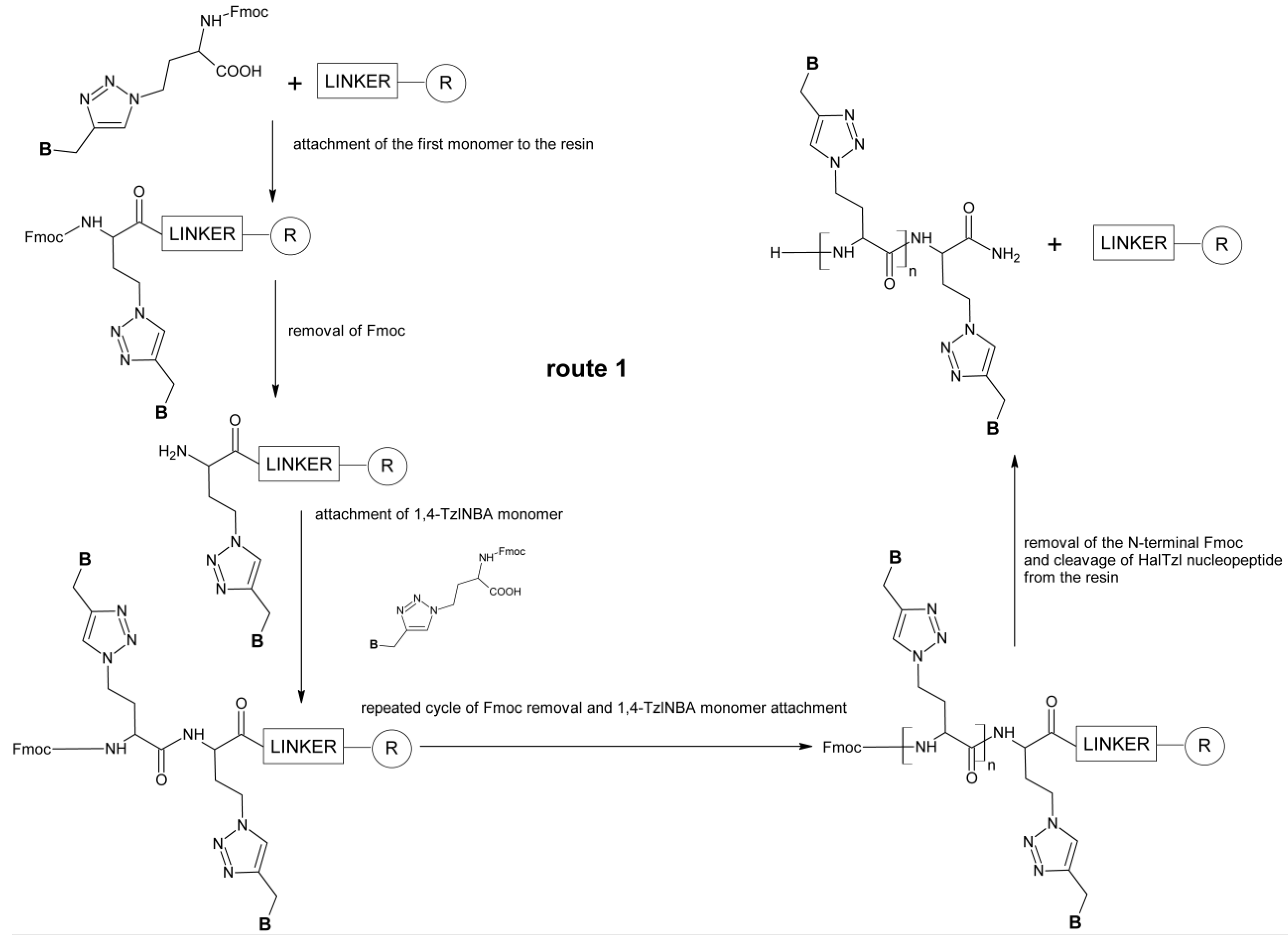

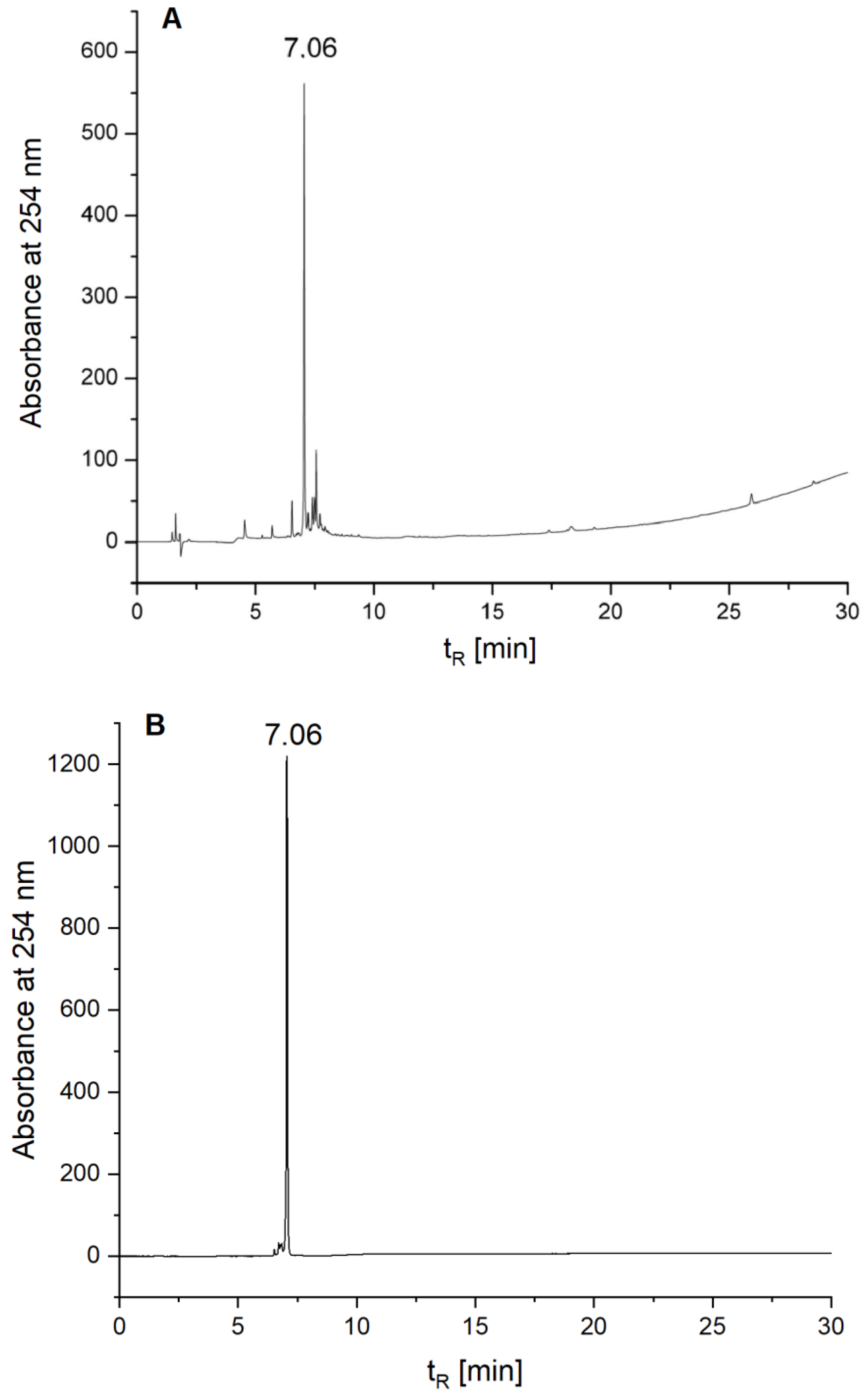

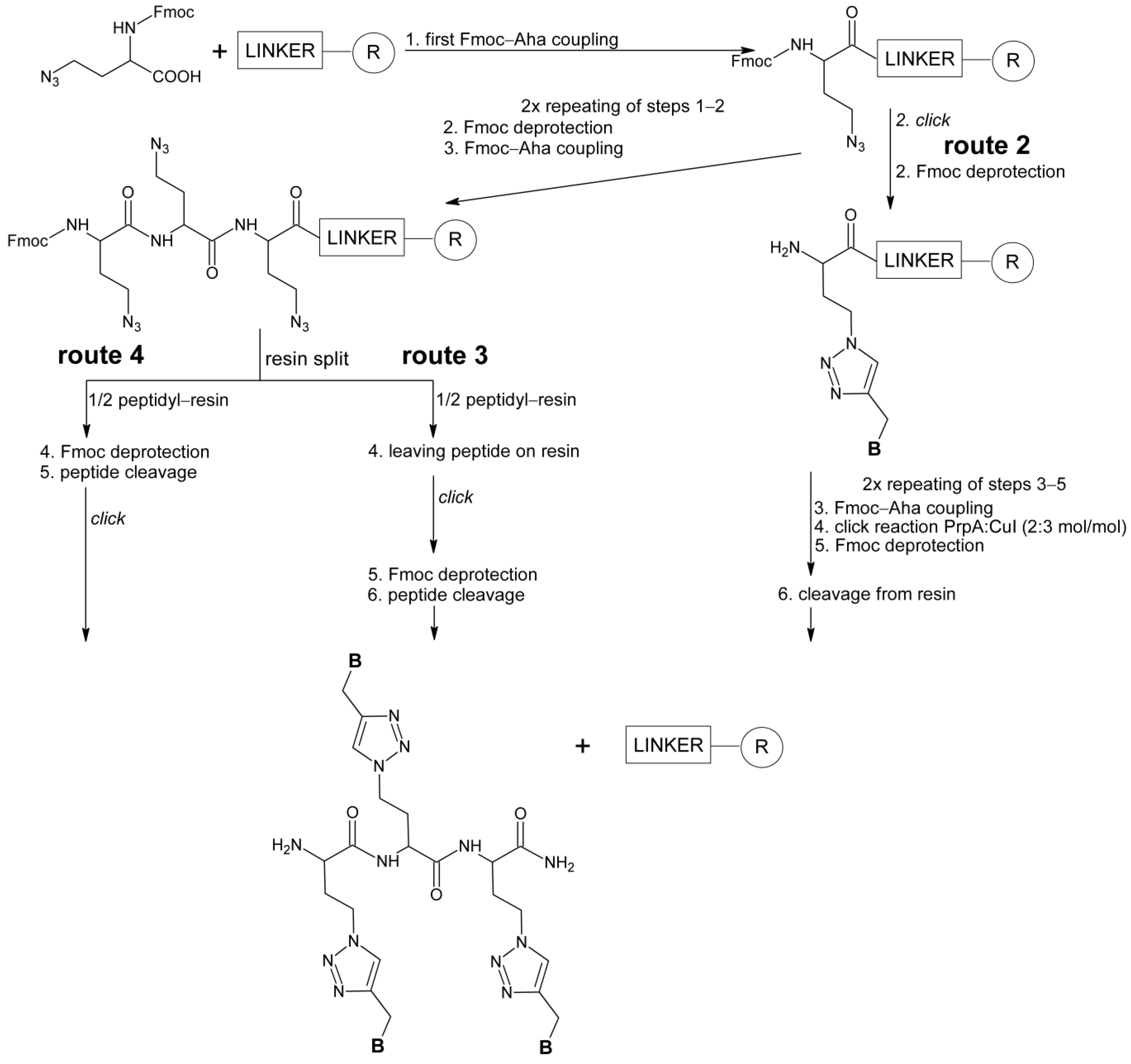

2.2. Solid-Phase Synthesis of HalTzlAAA

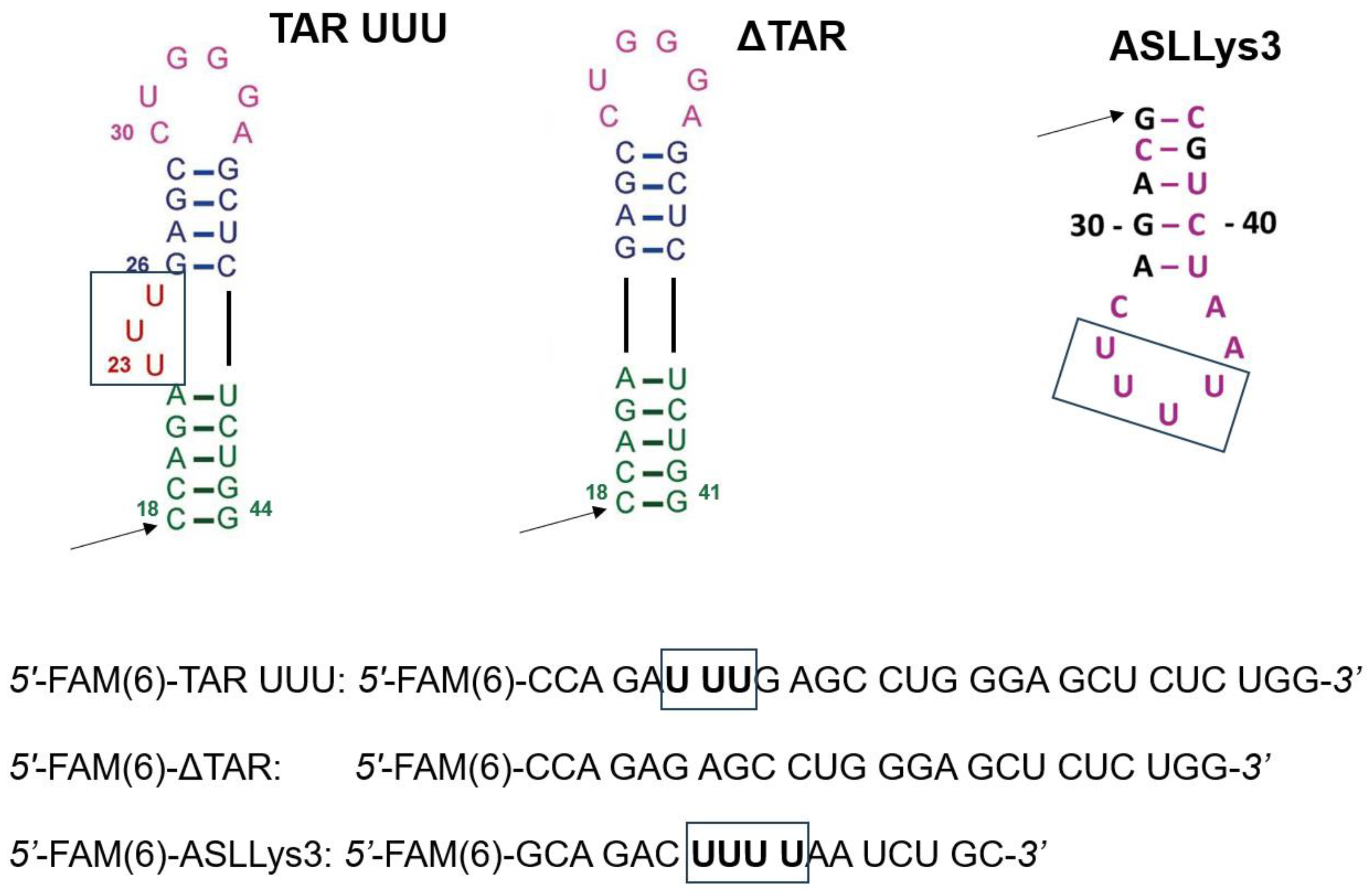

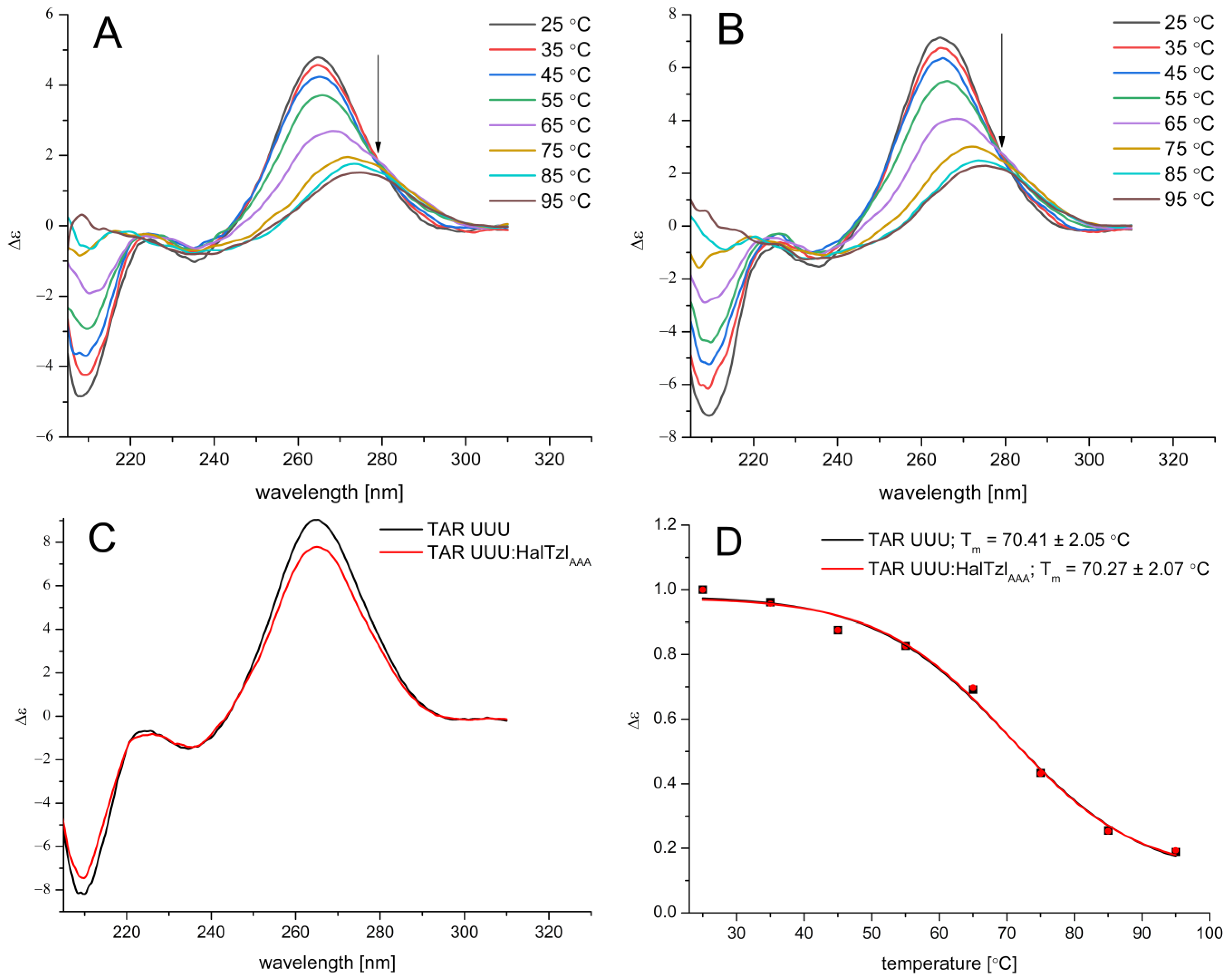

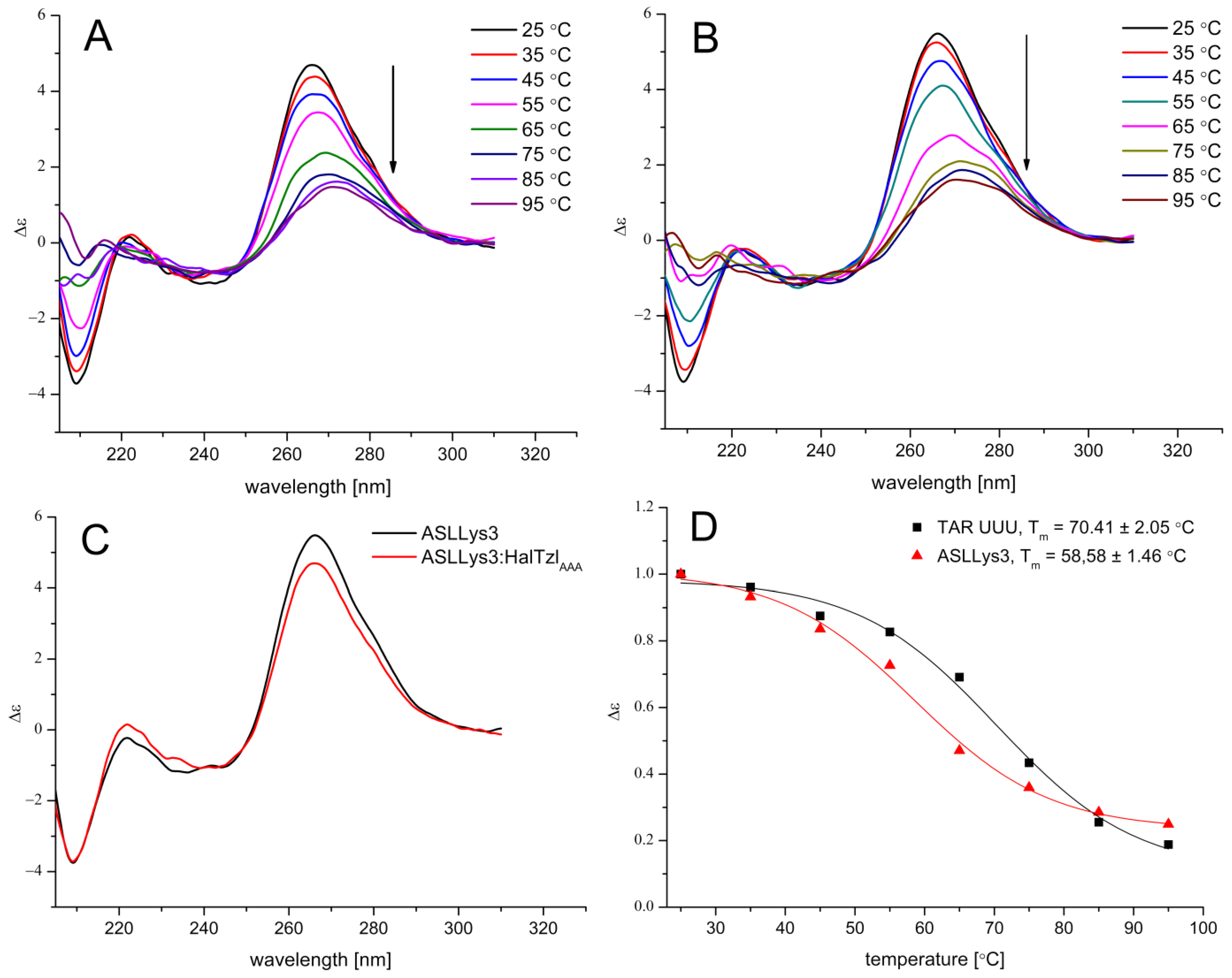

2.3. CD Studies of RNAs–HalTzlAAA Interaction

CD Study of TAR UUU RNA–HalTzlAAA Interaction

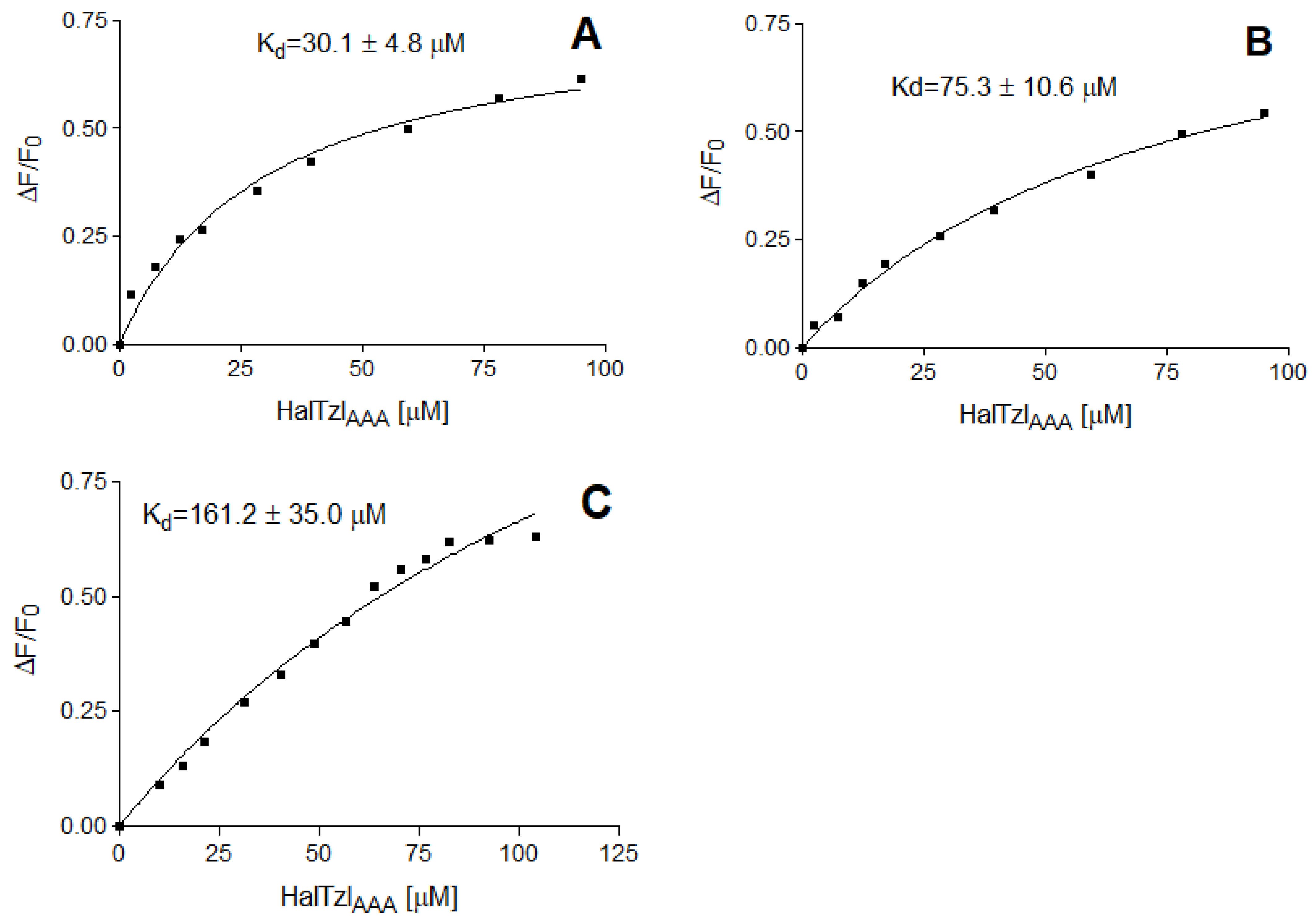

2.4. Fluorescence Anisotropy Study of TAR RNA–HalTzlAAA Interactions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of N9-Propargyladenine

3.2. Synthesis of L-2-(Fmoc-amino)-4-[4-(N9-methyladenine)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)butanoic Acid (1,4-TzlNBAA)

3.3. Solid-Phase Synthesis of HalTzlAAA Nucleopeptide

3.3.1. Standard SPPS of HalTzlAAA (Route 1)

3.3.2. Solid-Phase Synthesis of HalTzlAAA with a Single 1,4-TzlNBAA Residue Click on Resin (Route 2)

3.3.3. Solid-Phase Synthesis of HalTzlAAA with a Simultaneous All 1,4-TzlNBAA Residues Click on Resin (Route 3)

3.3.4. Post-Cleavage Click Synthesis of HalTzlAAA (Route 4)

3.4. U-Rich RNAs Synthesis

3.5. Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

3.6. Fluorescence Anisotropy Spectroscopy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1,4-TzlNBAA | nucleobase amino acid bearing of adenine attached to the side chain of Aha via 1,4-linked 1,2,3-triazole moiety |

| Ac | acetyl |

| ACN | acetonitrile |

| Aha | L-azidohomoalanine |

| ARR | arginine-rich region |

| ASLLys3 | unmodified anticodon stem–loop domain of human tRNALys3 |

| B, BH | nucleobase |

| bp | base pair |

| C18 | octadodecane chain |

| CuAAC | Cu(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition |

| DCM | dichloromethane |

| DMAP | 4-Dimethylaminopyridine |

| DMF | N,N-dimethylformamide |

| FAM(6) | fluorescein isomer 6 |

| Fl-RNA | 5′-fluorescein labeled RNA |

| Fmoc | fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl |

| Fmoc-Aha | Fmoc-L-azidohomoalanine |

| Hal | L-homoalanine |

| HalTzlAAA | trinucleopeptide designed on the basis of L-azidohomoalanine (Hal), containing adenine attached through a 1,4-linked-triazole linker to the Hal’s side chain |

| HATU | [dimethylamino(triazolo[4,5-b]pyridin-3-yloxy)methylidene]-dimethylazanium;3-hydroxytriazolo[4,5-b]pyridine hexafluorophosphate |

| HIV-1 | human immunodeficiency virus type 1 |

| HOAt | 1-Hydroxy-7-azabenzotriazole |

| tRNALys | tRNA specific for lysine |

| htRNALys3 | human tRNA specific for lysine (isoacceptor type 3) |

| MeOH | methanol |

| NBA | nucleobase amino acid |

| NP | nucleopeptide |

| PBS | priming binding side |

| PNA | peptide nucleic acid |

| RNAP II | RNA polymerase II |

| RT | reverse transcriptase |

| SPPS | solid-phase peptide synthesis |

| ssRNA | single-stranded RNA |

| TAR UUU | trans-activation response element with UUU bulge |

| TB | tris/borate buffer |

| t-BuOH | tert-butanol |

| TFA | trifluoroacetic acid |

| Tzl | 1,2,3-triazol |

References

- Harries, L.W. RNA Biology Provides New Therapeutic Targets for Human Disease. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S. RNA in Biology and Therapeutics. Mol. Cells 2023, 46, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Jin, H. RNA-based therapeutics: An overview and prospectus. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damase, T.R.; Sukhovershin, R.; Boada, C.; Taraballi, F.; Pettigrew, R.I.; Cooke, J.P. The Limitless Future of RNA Therapeutics. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 628137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, P.; Szyk, A.; Rekowski, P.; Weiss, P.A.; Agris, P.F. Anticodon domain methylated nucleosides of yeast tRNA(Phe) are significant recognition determinants in the binding of a phage display selected peptide. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 14191–14199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Monga, V. Peptide Nucleic Acids: Recent Developments in the Synthesis and Backbone Modifications. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 141, 106860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, P.; Chu, H.C.; Lo, P.K. Nucleic Acids and Their Analogues for Biomedical Applications. Biosensors 2022, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs-Disney, J.L.; Yang, X.; Gibaut, Q.M.R.; Tong, Y.; Batey, R.T.; Disney, M.D. Targeting RNA structures with small molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 736–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, K.; Hajdin, C.; Weeks, K. Principles for targeting RNA with drug-like small molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Zhou, J.; Li, X.; Xu, B. Self-assembly of nucleopeptides to interact with DNAs. Interface Focus 2017, 7, 20160116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucha, P.; Pieszko, M.; Bylińska, I.; Wiczk, W.; Ruczyński, J.; Prochera, K.; Rekowski, P. Solid Phase Synthesis and TAR RNA-Binding Activity of Nucleopeptides Containing Nucleobases Linked to the Side Chains via 1,4-Linked-1,2,3-triazole. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musumeci, D.; Roviello, V.; Roviello, G.N. DNA- and RNA-binding ability of oligoDapT, a nucleobase-decorated peptide, for biomedical applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 2613–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercurio, M.E.; Tomassi, S.; Gaglione, M.; Russo, R.; Chambery, A.; Lama, S.; Stiuso, P.; Cosconati, S.; Novellino, E.; Di Maro, S.; et al. Switchable Protecting Strategy for Solid Phase Synthesis of DNA and RNA Interacting Nucleopeptides. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 11612–11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heden van Noort, G.J.; van Delft, P.; Meeuwenoord, N.J.; Overkleeft, H.S.; van der Marel, G.A.; Filippov, D.V. Fully automated sequential solid phase approach towards viral RNA-nucleopeptides. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 8093–8095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verona, M.; Verdolino, V.; Palazzesi, F.; Corradini, R. Focus on PNA Flexibility and RNA Binding using Molecular Dynamics and Metadynamics. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellestor, F.; Paulasova, P. The peptide nucleic acids (PNAs), powerful tools for molecular genetics and cytogenetics. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 12, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiliszek, A.; Banaszak, K.; Dauter, Z.; Rypniewski, W. The first crystal structures of RNA-PNA duplexes and a PNA-PNA duplex containing mismatches—Toward anti-sense therapy against TREDs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 1937–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, E.; Bahal, R.; Ricciardi, A.; Saltzman, W.M.; Glazer, P.M. Therapeutic Peptide Nucleic Acids: Principles, Limitations, and Opportunities. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2017, 90, 583–598. [Google Scholar]

- MacLelland, V.; Kravitz, M.; Gupta, A. Therapeutic and diagnostic applications of antisense peptide nucleic acids. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 35, 102086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, D.; Mokhir, A.; Roviello, G.N. Synthesis and nucleic acid binding evaluation of a thyminyl l-diaminobutanoic acid-based nucleopeptide. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 100, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N.; Musumeci, D. Synthetic approaches to nucleopeptides containing all four nucleobases, and nucleic acid-binding studies on a mixed-sequence nucleo-oligolysine. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 63578–63585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roviello, G.N.; Vicidomini, C.; Di Gaetano, S.; Capasso, D.; Musumeci, D.; Roviello, V. Solid phase synthesis and RNA-binding activity of an arginine-containing nucleopeptide. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 14140–14148, Correction in RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 78514–78514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Shyu, A.B. U-rich sequence-binding proteins (URBPs) interacting with a 20-nucleotide U-rich sequence in the 3′ untranslated region of c-fos mRNA may be involved in the first step of c-fos mRNA degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 1992, 12, 2931. [Google Scholar]

- Filbin, M.E.; Kieft, J.S. Toward a structural understanding of IRES RNA function. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009, 19, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, I.; Ha, M.; Lim, J.; Yoon, M.-J.; Park, J.-E.; Kwon, S.C.; Chang, H.; Kim, V.N. TUT4/7-mediated uridylation of pre-let-7 in miRNA processing. Cell 2012, 151, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basha, E.; O’Neill, H.; Vierling, E. Small heat shock proteins and α-crystallins: Dynamic proteins with flexible functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2012, 37, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripin, N.; Boudet, J.; Duszczyk, M.M.; Hinniger, A.; Faller, M.; Krepl, M.; Gadi, A.; Schneider, R.; Šponer, J.; Meisner-Kober, N.C.; et al. Molecular basis for AU-rich element recognition and dimerization by the HuR C-terminal RRM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2935–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.M.; Choi, Y.H.; Tu, M.J. RNA Drugs and RNA Targets for Small Molecules: Principles, Progress, and Challenges. Pharmacol. Rev. 2020, 72, 862–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, A.L. Contemporary Progress and Opportunities in RNA-Targeted Drug Discovery. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abulwerdi, F.A.; Le Grice, S.F.J. Recent Advances in Targeting the HIV-1 Tat/TAR Complex. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 4112–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavali, S.S.; Bonn-Breach, R.; Wedekind, J.E. Face-time with TAR: Portraits of an HIV-1 RNA with diverse modes of effector recognition relevant for drug discovery. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 9326–9341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ne, E.; Palstra, R.J.; Mahmoudi, T. Transcription: Insights From the HIV-1 Promoter. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 335, 191–243. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, A.P. The HIV-1 Tat Protein: Mechanism of Action and Target for HIV-1 Cure Strategies. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 4098–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, E.; Nava, B.; Caputi, M. Tat is a multifunctional viral protein that modulates cellular gene expression and functions. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 27569–27581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze-Gahmen, U.; Hurley, J.H. Structural mechanism for HIV-1 TAR loop recognition by Tat and the super elongation complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 12973–12978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronsard, L.; Rai, T.; Rai, D.; Ramachandran, V.G.; Banerjea, A.C. In silico Analyses of Subtype Specific HIV-1 Tat-TAR RNA Interaction Reveals the Structural Determinants for Viral Activity. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, P.; Szyk, A.; Rekowski, P.; Barciszewski, J. Structural requirements for conserved Arg52 residue for interaction of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 trans-activation responsive element with trans-activator of transcription protein (49-57). Capillary electrophoresis mobility shift assay. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 968, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, L. tRNA(Lys3): The primer tRNA for reverse transcription in HIV-1. IUBMB Life 2002, 53, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadatmand, J.; Kleiman, L. Aspects of HIV-1 assembly that promote primer tRNA(Lys3) annealing to viral RNA. Virus Res. 2012, 169, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, W.D.; Barley-Maloney, L.; Stark, C.J.; Kaur, A.; Stolarchuk, C.; Sproat, B.; Leszczynska, G.; Malkiewicz, A.; Safwat, N.; Mucha, P.; et al. Functional recognition of the modified human tRNALys3(UUU) anticodon domain by HIV’s nucleocapsid protein and a peptide mimic. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 698–715, Erratum in J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 420, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oude Essink, B.B.; Das, A.T.; Berkhout, B. Structural requirements for the binding of tRNA Lys3 to reverse transcriptase of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 23867–23874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P.; Saadatmand, J.; Kleiman, L.; Musier-Forsyth, K. Molecular mimicry of human tRNALys anti-codon domain by HIV-1 RNA genome facilitates tRNA primer annealing. RNA 2013, 19, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavali, S.S.; Mali, S.M.; Jenkins, J.L.; Fasan, R.; Wedekind, J.E. Co-crystal structures of HIV TAR RNA bound to lab-evolved proteins show key roles for arginine relevant to the design of cyclic peptide TAR inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 16470–16486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavali, S.S.; Mali, S.M.; Bonn, R.; Saseendran Anitha, A.; Bennett, R.P.; Smith, H.C.; Fasan, R.; Wedekind, J.E. Cyclic peptides with a distinct arginine-fork motif recognize the HIV trans-activation response RNA in vitro and in cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 101390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, N.; Basu, A.; Palumbo, P.; Myers, R.L.; Pandey, V.N. Anti-TAR polyamide nucleotide analog conjugated with a membrane-permeating peptide inhibits human immunodeficiency virus type 1 production. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3881–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, B.; Tripathi, S.; Ganguly, S.; Harris, D.; Casale, R.A.; Pandey, V.N. A PNA-transportan conjugate targeted to the TAR region of the HIV-1 genome exhibits both antiviral and virucidal properties. Virology 2005, 331, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Hao, X.; Jing, L.; Wu, G.; Kang, D.; Liu, X.; Zhan, P. Recent applications of click chemistry in drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2019, 14, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobkowski, M.; Szychowska, A.; Pieszko, M.; Miszka, A.; Wojciechowska, M.; Alenowicz, M.; Ruczyński, J.; Rekowski, P.; Celewicz, L.; Barciszewski, J.; et al. ‘Click’ chemistry synthesis and capillary electrophoresis study of 1,4-linked 1,2,3-triazole AZT-systemin conjugate. J. Pept. Sci. 2014, 20, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumeci, F.; Schenone, S.; Desogus, A.; Nieddu, E.; Deodato, D.; Botta, L. Click chemistry, a potent tool in medicinal sciences. Curr. Med. Chem. 2015, 22, 2022–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter-O’Connell, I.; Booth, D.; Eason, B.; Grover, N. Thermodynamic examination of trinucleotide bulged RNA in the context of HIV-1 TAR RNA. RNA 2008, 14, 2550–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, X.; Bai, R. Click chemistry-aided drug discovery: A retrospective and prospective outlook. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 116037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, A.; Jayan, J.; Rangarajan, T.M.; Bose, K.; Benny, F.; Ipe, R.S.; Kumar, S.; Kukreti, N.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; Ghoneim, M.M.; et al. “Click Chemistry”: An Emerging Tool for Developing a New Class of Structural Motifs against Various Neurodegenerative Disorders. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 44437–44457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, J.; Saxena, M.; Rishi, N. An Overview of Recent Advances in Biomedical Applications of Click Chemistry. Bioconjug. Chem. 2021, 32, 1455–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornum, M.; Kumar, P.; Podsiadly, P.; Nielsen, P. Increasing the Stability of DNA/RNA Duplexes by Introducing Stacking Phenyl-Substituted Pyrazole, Furan, and Triazole Moieties in the Major Groove. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9592–9602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Hornum, M.; Nielsen, L.J.; Enderlin, G.; Andersen, N.K.; Len, C.; Herve, G.; Sartori, G.; Nielsen, P. High-affinity RNA targeting by oligonucleotides displaying aromatic stacking and amino groups in the major groove. Comparison of triazoles and phenyl substituents. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 2854–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Monomer/Nucleo- Peptide Label | [M + H]+ | RPHPLC | Quantity Yield % (mg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated | Determined | Analytical RP HPLC Gradient | tR [min] | ||

| Fmoc-1,4-TzlNBAA | 540.21 | 540.16 | 0–100%B in 30 min | 14.55 | 77% (415.45) |

| HalTzlAAA | 915.42 | 915.42 * | 0–100%B in 30 min | 7.06 | route 1–37% (4.20) route 2–30% (0.60) route 3–26% (0.52) route 4–29% (1.16) |

| Free/Complexed TAR/ASL | Tm [°C] | ΔTm [°C] |

|---|---|---|

| TAR UUU | 70.41 ± 2.05 | - |

| TAR UUU—HalTzlAAA | 70.27 ± 2.07 | −0.14 |

| ASLLys3 | 58.58 ± 1.46 | - |

| ASLLys3—HalTzlAAA | 59.20 ± 0.89 | 0.62 |

| Complex | Kd [µM] |

|---|---|

| Fl-TAR UUU–HalTzlAAA | 30.1 ± 4.8 |

| Fl-ASLLys3–HalTzlAAA | 75.3 ± 10.6 |

| Fl-ΔTAR–HalTzlAAA | 161.2 ± 35.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mucha, P.; Pieszko, M.; Bylińska, I.; Wiczk, W.; Ruczyński, J.; Rekowski, P. Solid-Phase Synthesis Approaches and U-Rich RNA-Binding Activity of Homotrimer Nucleopeptide Containing Adenine Linked to L-azidohomoalanine Side Chain via 1,4-Linked-1,2,3-Triazole. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311687

Mucha P, Pieszko M, Bylińska I, Wiczk W, Ruczyński J, Rekowski P. Solid-Phase Synthesis Approaches and U-Rich RNA-Binding Activity of Homotrimer Nucleopeptide Containing Adenine Linked to L-azidohomoalanine Side Chain via 1,4-Linked-1,2,3-Triazole. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311687

Chicago/Turabian StyleMucha, Piotr, Małgorzata Pieszko, Irena Bylińska, Wiesław Wiczk, Jarosław Ruczyński, and Piotr Rekowski. 2025. "Solid-Phase Synthesis Approaches and U-Rich RNA-Binding Activity of Homotrimer Nucleopeptide Containing Adenine Linked to L-azidohomoalanine Side Chain via 1,4-Linked-1,2,3-Triazole" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311687

APA StyleMucha, P., Pieszko, M., Bylińska, I., Wiczk, W., Ruczyński, J., & Rekowski, P. (2025). Solid-Phase Synthesis Approaches and U-Rich RNA-Binding Activity of Homotrimer Nucleopeptide Containing Adenine Linked to L-azidohomoalanine Side Chain via 1,4-Linked-1,2,3-Triazole. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11687. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311687