Cell Suspension of the Tree Fern Cyathea smithii (J.D. Hooker) and Its Metabolic Potential During Cell Growth: Preliminary Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

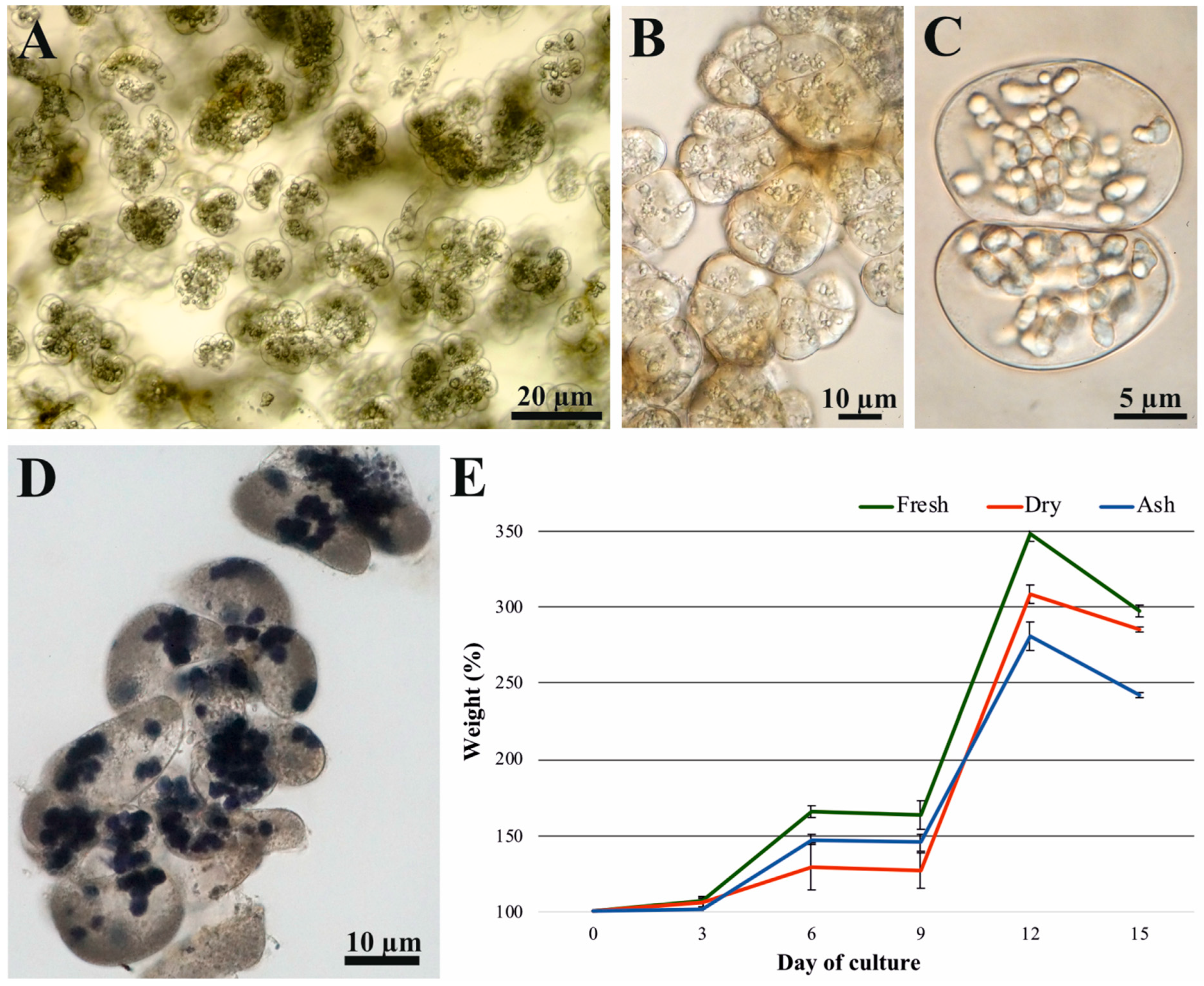

2.1. Kinetics of Established Cell Suspension

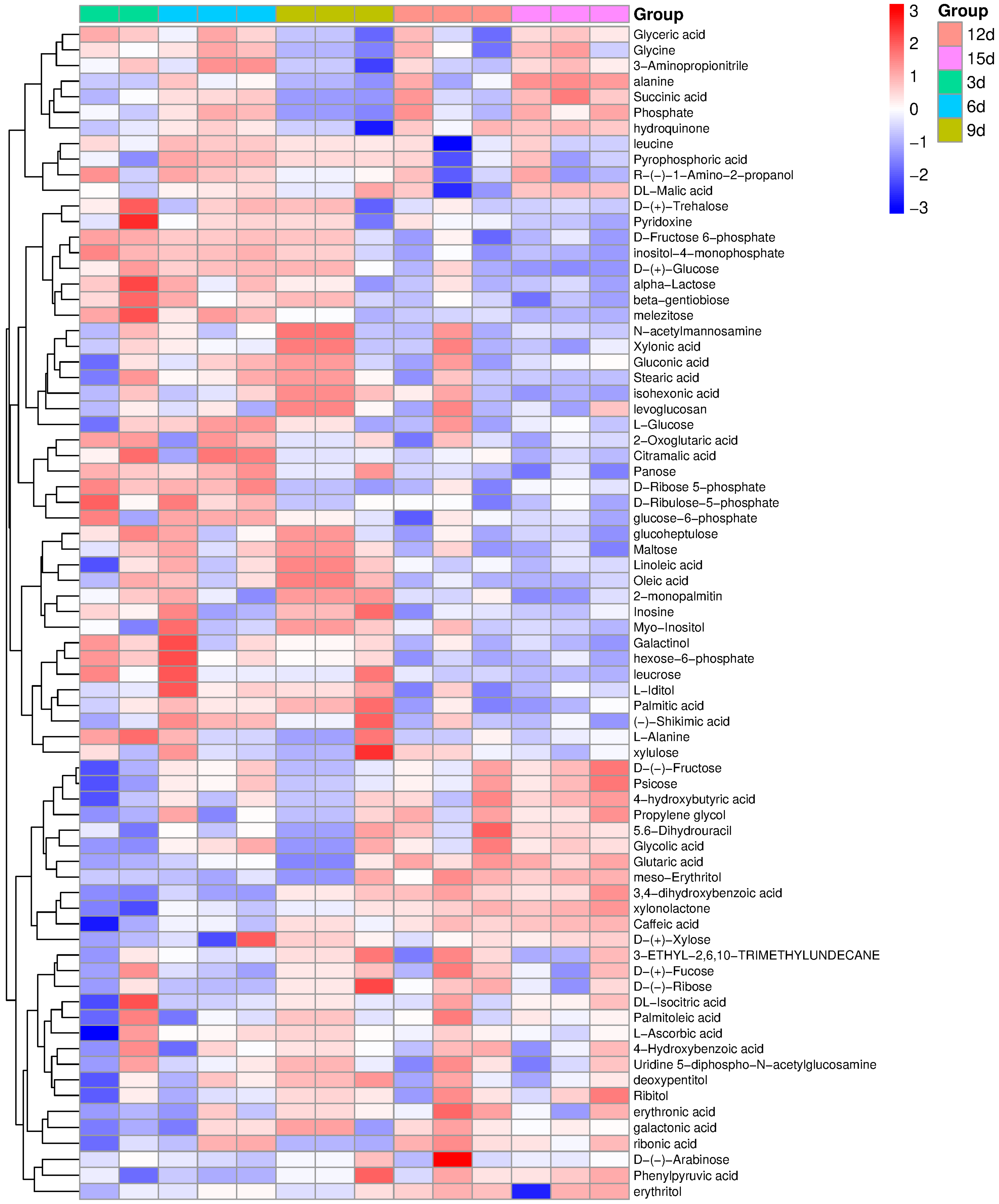

2.2. Biochemical Analysis of Cell Aggregates

- Organic acids

- Saccharides

- Amino acids

- Amines

- Polyhydric alcohols

- Nucleosides

- Sugar phosphates

- Others

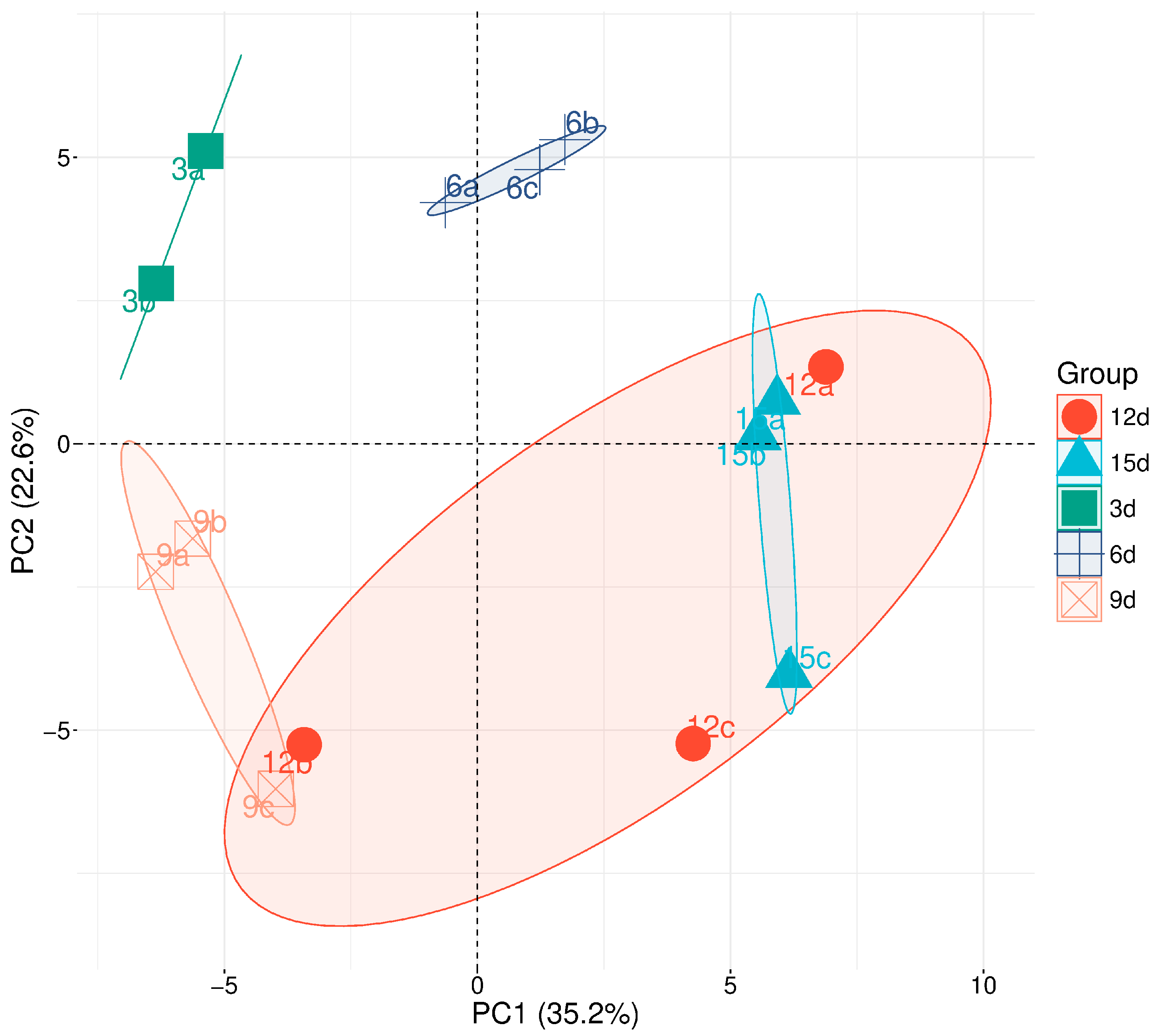

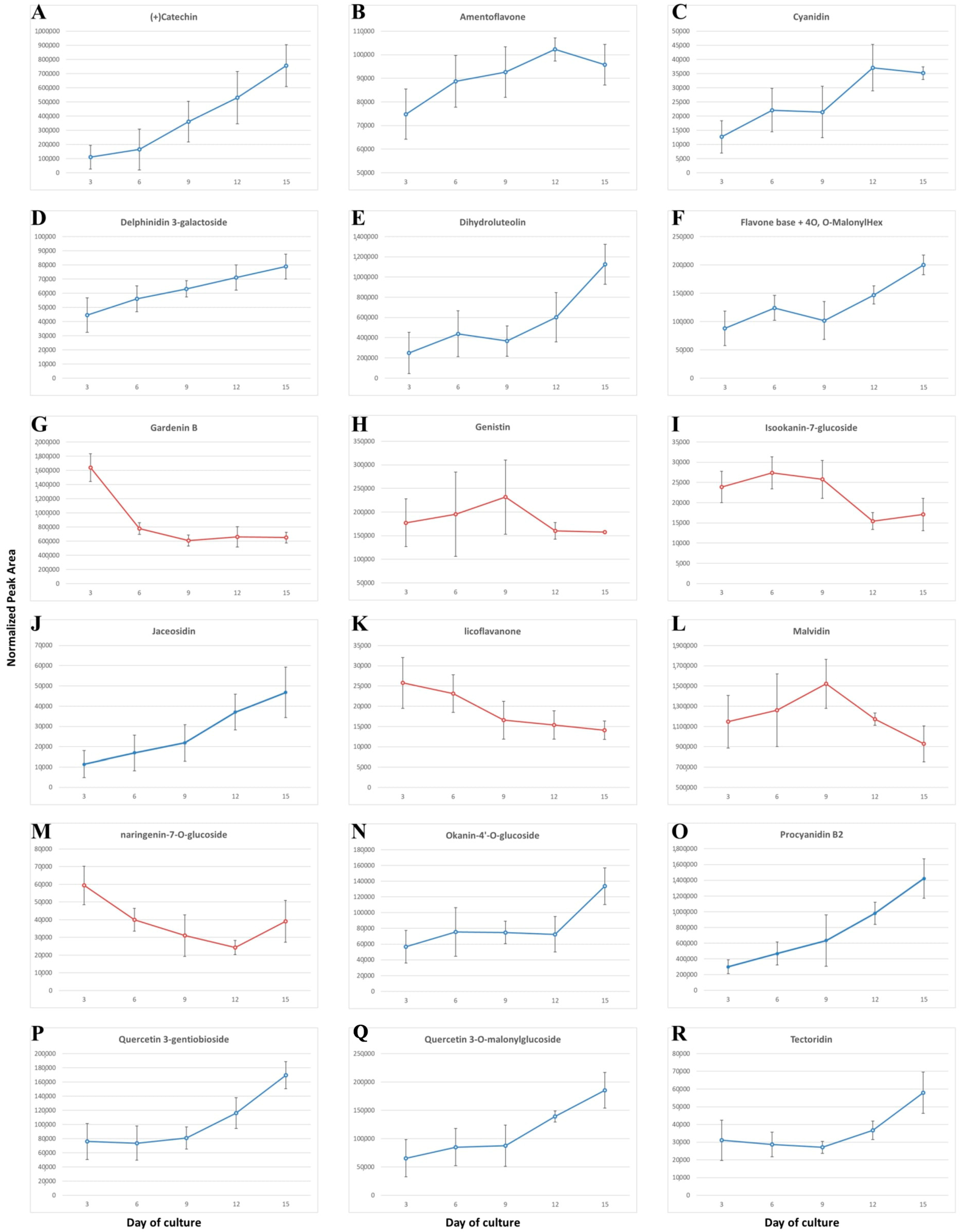

2.3. Analysis of Metabolites Measured at Five Time Points of the Cell Culture Duration

3. Discussion

3.1. Primary Metabolites

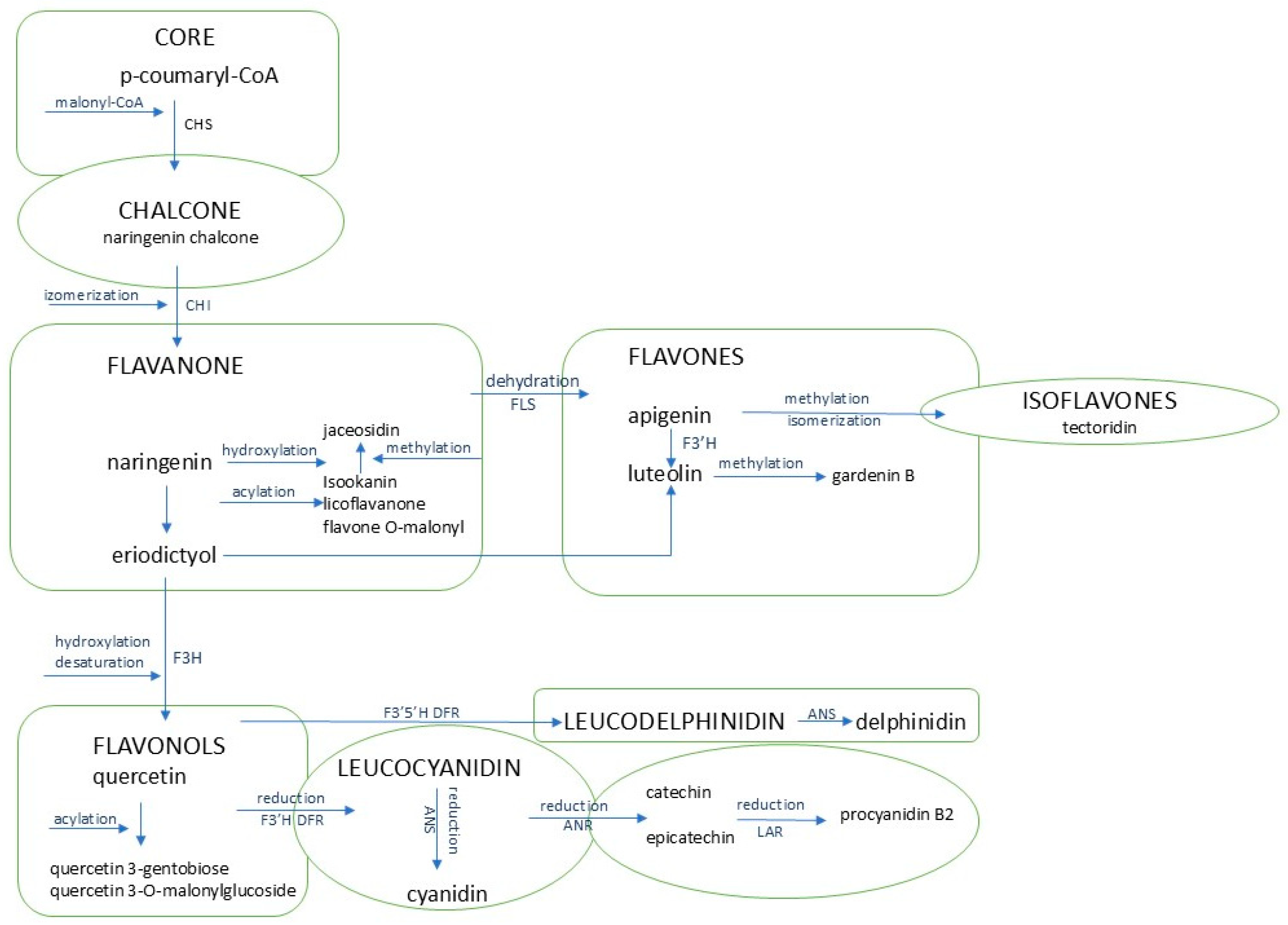

3.2. Secondary Metabolites

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Cell Suspension Sampling

4.3. Preparation of Living and Fixed Specimens for Bright-Field Light Microscopy

4.4. Metabolite Extraction from Cell Aggregates and Lc/Ms and Gc/Ms Metabolite Profiling

5. Conclusions and Prospective Studies

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAP | 6-Benzylaminopurine |

| 2,4-D | Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid |

| GC/MS | Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectroscopy |

| LC/MS | Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectroscopy |

| MS | Murashige and Skoog medium |

| NAA | Naphthalene Acetic Acid |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| TDZ | Thidiazuron (1-Phenyl-3-(1,2,3-thiadiazol-5-yl)urea |

References

- Cao, H.; Chai, T.T.; Wang, X.; Morais-Braga, M.F.B.; Yang, J.H.; Wong, F.C.; Wang, R.; Yao, H.; Cao, J.; Cornara, J.; et al. Phytochemicals from fern species: Potential for medicine applications. Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16, 379–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wujisguleng, W.; Long, C. Food uses of ferns in China: A review. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.M.; Dos Passos, C.; Dresch, R.R.; Kieling-Rubio, M.A.; Moreno, P.R.H.; Henriques, A.T. Chemical analysis, antioxidant and monoamine oxidase inhibition effects of some pteridophytes from Brazil. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2014, 10, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.Y.; Lim, Y.Y. Evaluation of antioxidant activities of the methanolic extracts of selected ferns in Malaysia. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2011, 2, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Hernández, I.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, J.; Barriada-Bernal, L.G.; Méndez-Lagunas, L. Tree ferns (Cyatheaceae) as a source of phenolic compounds—A review. J. Herb. Med. 2022, 35, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souder, R.W.; Babb, M.S. Flavonoids in tree ferns. Phytochemistry 1972, 11, 3079–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janakiraman, N.; Johnson, M.A. Inter specific variation studies on Cyathea species using phyto-chemical and fluorescence analysis. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Stud. 2015, 3, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Janakiraman, N.; Johnson, M.A. GC-MS analysis of ethanolic extracts of Cyathea nilgirensis, C. gigantea, and C. crinita. Egypt Pharm. J. 2016, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hort, M.A.; DalBó, S.; Brighente, I.M.C.; Pizzolatti, M.G.; Pedrosa, R.C.; Ribeiro-do-Valle, R.M. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effects of Cyathea phalerata Mart. (Cyatheaceae). Nordic Pharmacological Society. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008, 103, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, A.; Choudhury, M.D.; Chakraborty, M.; Dutta, B.K. Phytochemical screening and TLC profiling of plant extracts of Cyathea gigantea (Wall. Ex. Hook.) Haltt. and Cyathea brunoniana. Wall. ex. Hook. (Cl. & Bak.). Biol. Environ. Sci. 2010, 5, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kale, V.M. Analysis of bioactive compounds on ethanolic extract of whole plant of Cyathea gigantea. Res. J. Life Sci. Bioinform. Pharm. Chem. Sci. 2015, 1, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybczyński, J.J.; Kaźmierczak, A.; Dos Santos-Szewczyk, K.; Tomaszewicz, W.; Miazga-Karska, M.; Mikuła, A. Biotechnology of the tree fern Cyathea smithii (J.D. Hooker1854; Soft tree fern, Katote). II. Cell suspension culture focusing on structure and physiology in the presence of 2,4-D and BAP. Cells 2022, 11, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybczyński, J.J.; Marczak, Ł.; Stobiecki, M.; Strugała, A.; Mikuła, A. The metabolite content of the post-culture medium of the tree fern Cyathea delgadii Sternb. cell suspension cultured in the presence of 2,4-D and BAP. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Saikai, Y. Pharmaceutical studies on ferns. VIII. Distribution of flavonoids in ferns. Pharm. Bull. 1955, 3, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xia, X.; Cao, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, J. Flavonoid concentrations and bioactivity of flavonoid extracts from 19 species of ferns from China. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 58, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Coa, J.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Q. Analysis of flavonoids and antioxidants in extracts of ferns from Tianmu Mountain in Zhejinang Province (China). Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 97, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Biosynthesis of flavonoids and effects of stress. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, M. Studies on phytochemical analysis and screening for active compounds in some ferns of Ranchi and Latehar districts. Int. J. Acad. Res. Dev. 2018, 3, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Large, M.F.; Braggins, J.E. Tree Ferns; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2004; pp. 1–260. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D.L. Encyclopedia of Ferns; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 1987; p. 254. [Google Scholar]

- Goller, K.; Rybczyński, J.J. Gametophyte and sporophyte of tree ferns in vitro culture. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2007, 76, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybczyński, J.J.; Podwyszyńska, M.; Tomaszewicz, W.; Mikuła, A. Biotechnology of the tree fern Cyathea smithii (J.D. Hooker1854; Soft tree fern, Katote). I. Morphogenic potential of shoot apical dome, plant regeneration, and nuclear DNA content of regenerants in the presence of TDZ and NAA. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2022, 91, 9133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bucio, J.; Nieto-Jacobo, M.F.; Ramírez-Rodríguez, V.; Herrera-Estrella, L. Organic acid metabolism in plants from adaptive physiology to transgenic varieties for cultivation in extreme soils. Plant Sci. 2000, 160, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moing, A. Sugar alcohols as carbohydrate reserves in some higher plants. Dev. Crop Sci. 2000, 26, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, A.; Yabuta, Y.; Shigeoka, S. Galactinol and raffinose constitute a novel function to protect plants from oxidative damage. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodianiuk, L.; Budniak, L.; Marchysyn, S.; Basaraba, R. Determination of amino acids and sugars content in Antennaria dioica Gaertn. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2019, 11, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, F.; Monza, J.; Signorelli, S. Determination of free proline in plants. In ROS Signaling in Plants; Corpas, F.J., Palma, J.M., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, I.B.; Krogstrup, P.; Hansen, J. Embryogenic callus formation, growth and regeneration in callus and cell suspension of Miscanthus x ogiformis Honda giganteus, as affected by proline. PCTOC 1997, 50, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, B.E.; Mesbah, M.; Yavasari, N. The effect of in planta TIBA and proline treatment on somatic embryogenesis of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.). Euphytica 2000, 112, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, B.; Kale, P.; Bahurupe, J.; Jadhav, A.; Kale, A.; Pawar, A. Proline and glutamine improve in vitro callus induction and subsequent shooting bin rice. Rice Sci. 2015, 22, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabados, L.; Savouré, A. Proline: A multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 15, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, U.K.; Islam, M.N.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Cao, X.; Khan, M.A.R. Proline, a multifaceted signalling molecule in plant responses to abiotic stress: Understanding the physiological mechanisms. Plant Biol. 2022, 24, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastdrager, J.; Hanson, J.; Smeekens, S. Sugar signals and the control of plant growth and development. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, N.J.; von Schaewen, A. The oxidative pentose phosphate pathway: Structure and organization. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003, 6, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, P.P.N. Inositol phosphates and their metabolism in plants. In Myo-Inositol Phosphates, Phosphoinositides, and Signal Transduction; Biswas, B.B., Biswas, S., Eds.; Subcellular Biochemistry; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1996; Volume 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.; Torres, A.G.; de Pouplana, L.R. Inosine in biology and disease. Genes 2021, 12, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, S.; Somasiri, S.; Mahanama, R.; Ruhunuge, R.; Widanagamage, G. Development and validation of a method based on liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry for comprehensive profiling of phenolic compounds in rice. Microchem. J. 2023, 193, 109211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proestos, C.; Sereli, D.; Komaitis, M. Determination of phenolic compounds in aromatic plants by RP-HPLC and GC-MS. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolyachi, Y.; Marriott, P.J. GC for flavonoids analysis: Past, current, and prospective trends. J. Sep. Sci. 2013, 36, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivilompolo, Y.; Oburka, V.; Hyotylainen, T. Comparison of GC–MS and LC–MS methods for the analysis of antioxidant phenolic acids in herbs. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 388, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathesius, U. Flavonoid functions in plants and their interactions with other organism. Plants 2018, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewicz, W.; Cioć, M.; Dos Santos Szewczyk, K.; Grzyb, M.; Pietrzak, W.; Pawłowska, B.; Mikuła, A. Enhancing in vitro production of the tree fern Cyathea delgadii and modifying secondary metabolite profiles by stimulation with LED lighting. Cells 2022, 11, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, C.; Saavedra, E.; del Rosario, H.; Perdomo, J.; Loro, J.F.; Cifuente, D.A.; Tonn, C.E.; García, C.; Quintana, J.; Estévez, F. Gardenin B-induced cell death in human leukemia cells involves multiple caspases but is independent of the generation of reactive oxygen species. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 256, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Heuy, H.J. The roles of catechins in regulation of systemic inflammation. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 31, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Islam, A.; Rahman, K.; Uddin, N. The pharmacological and biological roles of eriodictyol. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2020, 43, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Geng, Z.; Song, A.; Jiang, J.; Chen, S.; Chen, F. Functional identification of a flavone synthase and a flavonol synthase genes affecting flower color formation in Chrysanthemum morifolium. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fan, W.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Huang, J.; Zhang, P. Functional characterization of dihydroflavonol-4-reductase in anthocyanin biosynthesis for purple sweet potato underlines the direct evidence of anthocyanins function against abiotic stresses. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Song, Y.; Lin, J.; Dixon, R.A. The complexities of proantocyanidin biosynthesis and its regulation in plants. Plant Comm. 2023, 4, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Jun, J.H.; Liu, C.; Dixon, R.A. The flexibility of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in plants. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, X.; Agar, O.T.; Barrow, C.J.; Dunshea, F.R.; Suleria, H.A.R. Phenolic compounds profiling and their antioxidant capacity in the peel, pulp, and seed of Australian grown avocado. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, R.; Tomas-Navarro, M.; Yuste, J.E.; Crupi, P.; Vallejo, F. An update on citrus polymethoxyflavones: Chemistry, metabolic fate, and relevant bioactivities. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 2179–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.A.; Sarnala, S. Proanthocyanidin biosynthesis—A matter of protection. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chvapil, M. Inhibition of breast adenocarcinoma growth by intratumoral injection of lipophilic long-acting lathyrogens. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2005, 16, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanina, J.; Táborská, E.; Bochořáková, H.; Slaninová, I.; Humpa, O.; Robinson, U.E.; Schram, K.H. New and facile method of preparation of the anti-HIV-1 agent, 1,3-dicaffeoylquinic acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 3383–3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, N.-I.; Kennelly, E.J.; Kardono, L.B.S.; Tsauri, S.; Padmawinata, K.; Soejarto, D.D.; Kinghorn, A.D. Flavonoids and a proanthrocyanidin from rhizomes of Selliguea feei. Phytochemistry 1994, 36, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth-Pawlak, D.; Kachlicki, P.; Stobiecki, M. Mass spectrometry—Application in the studies on plant metabolome. BioTechnologia 2007, 76, 156–175. [Google Scholar]

| Total | Expected | Hits | Raw p | -LOG10(p) | Holm Adjust | FDR | Impact | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism | 29 | 1.1342 | 6 | 0.00065019 | 3.187 | 0.062418 | 0.038884 | 0.30155 |

| Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 22 | 0.86042 | 5 | 0.0012151 | 2.9154 | 0.11544 | 0.038884 | 0 |

| Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis | 22 | 0.86042 | 5 | 0.0012151 | 2.9154 | 0.11544 | 0.038884 | 0.18018 |

| Galactose metabolism | 27 | 1.056 | 5 | 0.0032043 | 2.4943 | 0.298 | 0.076904 | 0.2175 |

| Pentose phosphate pathway | 19 | 0.74309 | 4 | 0.0052643 | 2.2787 | 0.48431 | 0.091485 | 0.37439 |

| Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 20 | 0.7822 | 4 | 0.0063903 | 2.1945 | 0.58152 | 0.091485 | 0.26155 |

| Carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms | 21 | 0.82131 | 4 | 0.0076663 | 2.1154 | 0.68996 | 0.091485 | 0.07173 |

| Flavonoid biosynthesis | 47 | 1.8382 | 6 | 0.0084883 | 2.0712 | 0.75546 | 0.091485 | 0.19444 |

| Linoleic acid metabolism | 4 | 0.15644 | 2 | 0.0085767 | 2.0667 | 0.75546 | 0.091485 | 1 |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 50 | 1.9555 | 6 | 0.011467 | 1.9406 | 0.9976 | 0.11008 | 0 |

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | 16 | 0.62576 | 3 | 0.022128 | 1.6551 | 1 | 0.19311 | 0.34375 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis | 46 | 1.7991 | 5 | 0.030811 | 1.5113 | 1 | 0.24648 | 0 |

| Tropane, piperidine and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis | 8 | 0.31288 | 2 | 0.036175 | 1.4416 | 1 | 0.24806 | 0 |

| Stilbenoid, diarylheptanoid and gingerol biosynthesis | 8 | 0.31288 | 2 | 0.036175 | 1.4416 | 1 | 0.24806 | 0.2647 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rybczyński, J.J.; Marczak, Ł.; Skórkowska-Telichowska, K.; Stobiecki, M.; Szopa, J.; Mikuła, A. Cell Suspension of the Tree Fern Cyathea smithii (J.D. Hooker) and Its Metabolic Potential During Cell Growth: Preliminary Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311683

Rybczyński JJ, Marczak Ł, Skórkowska-Telichowska K, Stobiecki M, Szopa J, Mikuła A. Cell Suspension of the Tree Fern Cyathea smithii (J.D. Hooker) and Its Metabolic Potential During Cell Growth: Preliminary Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311683

Chicago/Turabian StyleRybczyński, Jan J., Łukasz Marczak, Katarzyna Skórkowska-Telichowska, Maciej Stobiecki, Jan Szopa, and Anna Mikuła. 2025. "Cell Suspension of the Tree Fern Cyathea smithii (J.D. Hooker) and Its Metabolic Potential During Cell Growth: Preliminary Studies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311683

APA StyleRybczyński, J. J., Marczak, Ł., Skórkowska-Telichowska, K., Stobiecki, M., Szopa, J., & Mikuła, A. (2025). Cell Suspension of the Tree Fern Cyathea smithii (J.D. Hooker) and Its Metabolic Potential During Cell Growth: Preliminary Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11683. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311683