Novel NUTM1 Fusions in Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Expanding the Genetic and Clinical Landscape

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Description

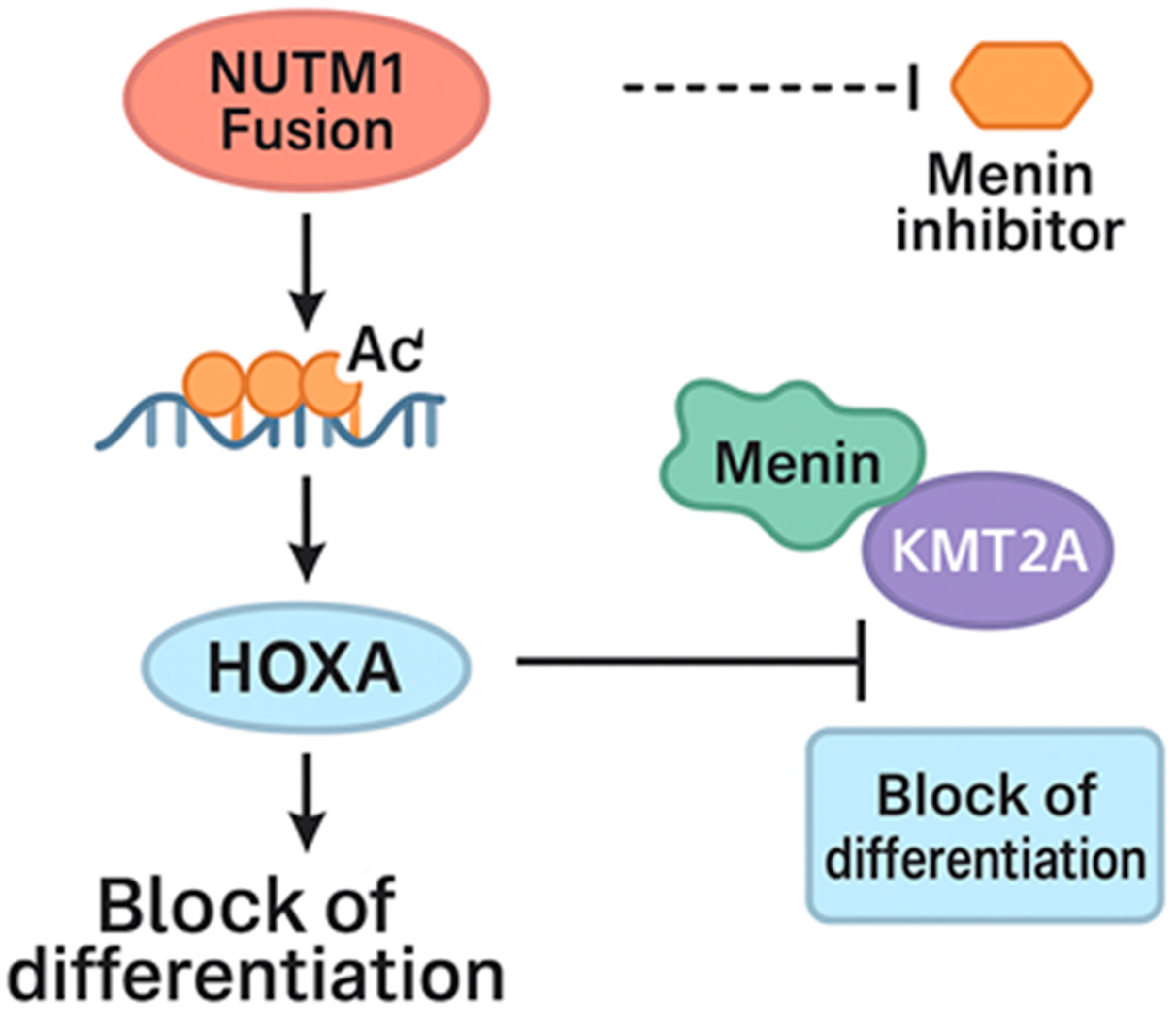

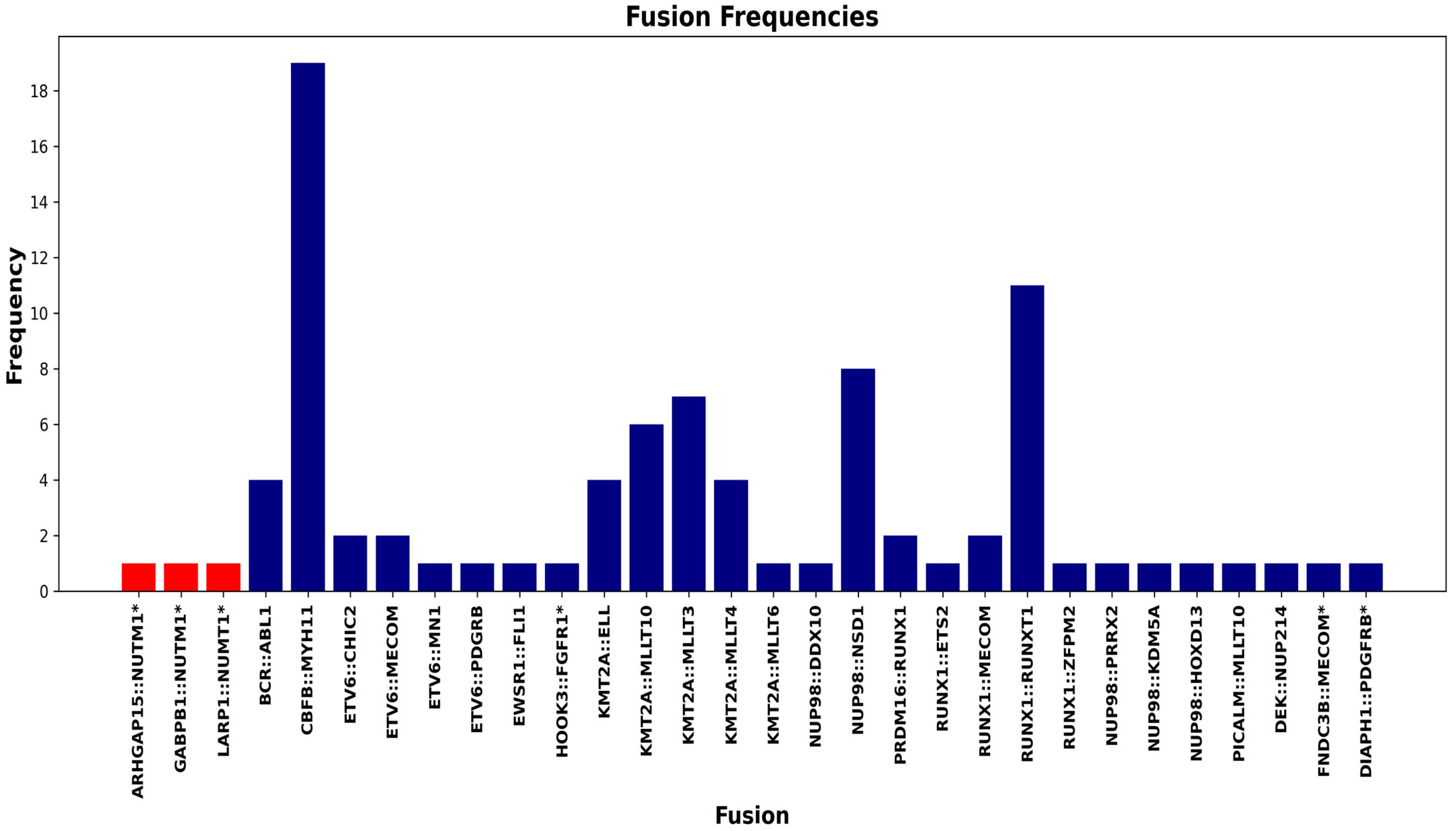

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AML | Acute Myeloid Leukemia |

| NUTM1 | NUT Midline Carcinoma Family Member 1 |

| BMBx | Bone Marrow Biopsy |

| HSCT | Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant |

| FISH | Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization |

| HOXA9 | Homeobox A9 |

| LMO2 | LIM Domain Only 2 |

| ELN | European Leukemia Network |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| MRD | Measurable Residual Disease |

References

- Li, W. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Hematolymphoid Tumors. In Leukemia [Internet]; Li, W., Ed.; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2022; Chapter 1. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK586208/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Luo, W.; Stevens, T.M.; Stafford, P.; Miettinen, M.; Gatalica, Z.; Vranic, S. NUTM1-Rearranged Neoplasms-A Heterogeneous Group of Primitive Tumors with Expanding Spectrum of Histology and Molecular Alterations-An Updated Review. Curr. Oncol. 2021, 28, 4485–4503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barletta, J.A.; Gilday, S.D.; Afkhami, M.; Bell, D.; Bocklage, T.; Boisselier, P.; Chau, N.G.; Cipriani, N.A.; Costes-Martineau, V.; Ghossein, R.A.; et al. Nutm1-rearranged carcinoma of the thyroid: A distinct subset of nut carcinoma characterized by frequent nsd3-nutm1 fusions. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2022, 46, 1706–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, J.M.; Valsecchi, M.G.; Hormann, F.M.; Antić, Ž.; Zaliova, M.; Schwab, C.; Cazzaniga, G.; Arfeuille, C.; Cavé, H.; Attarbaschi, A.; et al. Favorable outcome of NUTM1-rearranged infant and pediatric B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a collaborative international study. Leukemia 2021, 35, 2978–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stengel, A.; Shahswar, R.; Haferlach, T.; Walter, W.; Hutter, S.; Meggendorfer, M.; Kern, W.; Haferlach, C. Whole transcriptome sequencing detects a large number of novel fusion transcripts in patients with AML and MDS. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 5393–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.; Chen, X.; Cao, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, X.; Cao, P.; Fang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; et al. Identification of a novel AVEN-NUTM1 fusion gene in acute myeloid leukemia. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2021, 43, O207–O210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mura, M.; Hopkins, T.G.; Michael, T.; Abd-Latip, N.; Weir, J.; Aboagye, E.; Mauri, F.; Jameson, C.; Sturge, J.; Gabra, H.; et al. LARP1 post-transcriptionally regulates mTOR and contributes to cancer progression. Oncogene 2015, 34, 5025–5036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenzer, H.; Abdel Mouti, M.; Neubert, P.; Morris, J.; Stockton, J.; Bonham, S.; Fellermeyer, M.; Chettle, J.; Fischer, R.; Beggs, A.D.; et al. LARP1 isoform expression in human cancer cell lines. RNA Biol. 2021, 18, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Tsukamoto, T.; Chinen, Y.; Shimura, Y.; Sasaki, N.; Nagoshi, H.; Sato, R.; Adachi, H.; Nakano, M.; Horiike, S.; et al. Detection of novel and recurrent conjoined genes in non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Exp. Hematop. 2021, 61, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takagi, K.; Miki, Y.; Onodera, Y.; Ishida, T.; Watanabe, M.; Sasano, H.; Suzuki, T. ARHGAP15 in Human Breast Carcinoma: A Potent Tumor Suppressor Regulated by Androgens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Chen, J.F.; Sarungbam, J.; Tickoo, S.; Dickson, B.C.; Reuter, V.E.; Antonescu, C.R. NUTM1-fusion positive malignant neoplasms of the genitourinary tract: A report of six cases highlighting involvement of unusual anatomic locations and histologic heterogeneity. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2022, 61, 542–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, X.; Mu, N.; Yuan, X.; Wang, N.; Juhlin, C.C.; Strååt, K.; Larsson, C.; Neo, S.Y.; Xu, D. Downregulation and Hypermethylation of GABPB1 Is Associated with Aggressive Thyroid Cancer Features. Cancers 2022, 14, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manukjan, G.; Ripperger, T.; Venturini, L.; Stadler, M.; Göhring, G.; Schambach, A.; Schlegelberger, B.; Steinemann, D. GABP is necessary for stem/progenitor cell maintenance and myeloid differentiation in human hematopoiesis and chronic myeloid leukemia. Stem Cell Res. 2016, 16, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döhner, H.; Wei, A.H.; Appelbaum, F.R.; Craddock, C.; DiNardo, C.D.; Dombret, H.; Ebert, B.L.; Fenaux, P.; Godley, L.A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 2022, 140, 1345–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case Number | Test | At Time of Diagnosis | Relapsed/Refractory Disease (Pre-Transplant) | Relapsed/Refractory Disease (Post-Transplant) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

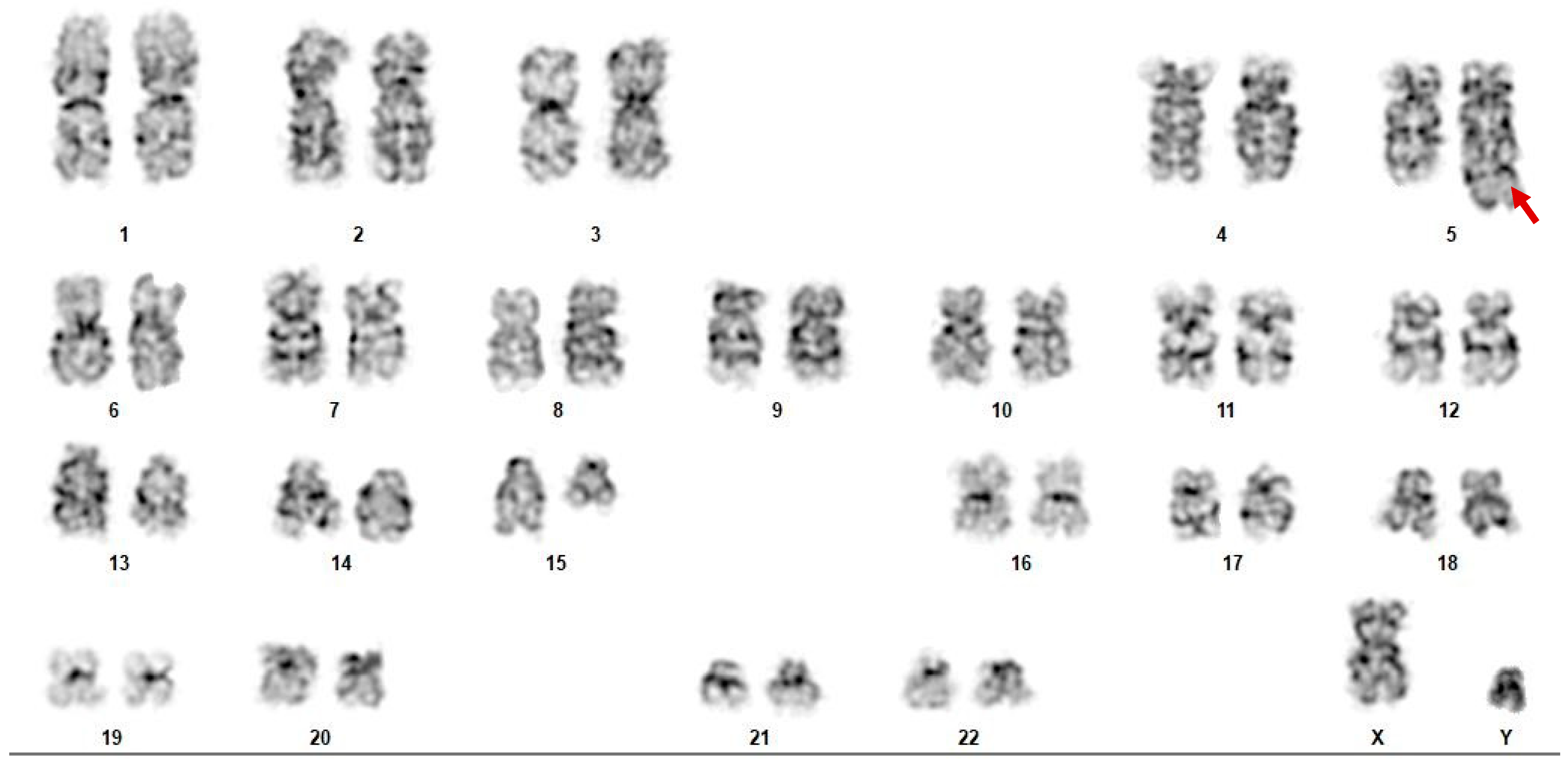

| Case 1 | Cytogenetics | 45~46, X, −Y, add(9)(q34), del(15)(q11.2)[cp6]/46, XY, del(15)(q22q24), del(20)(q11.2q13.1)[cp5]/46, XY, add(15)(q24)[2]/46, XY[7] | 46, XY, t(3;11;6)(p21;p15;q23), t(5;15)(q33;q11.2)[19] 46, XY[3] | 46, XY, t(3;11;6)(p21;p15;q23), t(5;15)(q33;q11.2)[18] 46, XX[2] |

| RNA-seq | LARP1::NUTM1 | LARP1::NUTM1 Elevated expression: CDK6, FLT3, LMO2 | ||

| DNA-seq | DNMT3A (D845Afs*8), IDH2 (R172K), and BCOR (S1263*) | ASXL2 (K873Nfs*6), BCOR (S1297*), DNMT3A (D845Afs*8), IDH2 (R172K) | ASXL2 (K873fs*6), BCOR (S1297*), DNMT3A (D845fs*8), IDH2 (R172K), NSD1 (V1016fs*27) | |

| Flow Cytometry | Expanded (40%) abnormal CD34-negative immature “monocytic” population expressing CD4, CD11c, CD13 (dim), CD15 (strong), CD33 (strong), CD38, CD123, and HLA-DR. This population is negative for CD117 and CD34. Proportion of 12.3% abnormal myeloid blasts expressing CD13 (subset increased), CD33, CD34, CD38 (slightly decreased), CD45 (dim), CD117, and CD123 (dim) | Expanded abnormal myeloid blast population detected (~38% of total analyzed white blood cells) expressing CD4 (partial), CD7, CD9 (partial), CD11c (partial), CD13 (dim), CD15 (subset), CD33, CD34, CD38 (decreased), CD45 (dim), CD58, CD117, CD123 (moderate), and HLA-DR | ||

| Case 2 | Cytogenetics | Normal | t(2;15) (q23;q15)[9]/46, XY[11] | Limited study with normal karyotype |

| RNA-seq | ARHGAP15::NUTM1 | |||

| DNA-seq | Negative for tested genes (CEBPA, IDH1/IDH2, FLT3-ITD, FLT3-TKD, KIT, NPM1) | ASXL1 (G646fs*12), RUNX1 (R169fs*44), TET2 (Q1942*) | ||

| Flow Cytometry | Flow cytometry revealed increased monocytes (46%) with aberrant CD56 expression along with 10% CD34-positive myeloblasts. Blasts expressed CD7, CD13, CD33, CD34, CD38, CD117, and HLA-DR | Increased immature myelomonocytic population (24%) | Abnormal monocytic cell population (>90% of total analyzed cells) expressing CD4, CD7 (small subset), CD9 (partial), CD11b, CD11c, CD13 (decreased), CD14, CD15, CD16 (partial), CD33, CD38, CD45 (bright, monocytic gate), CD56 (minor subset), CD64, CD123 (moderate), and HLA-DR (partial) | |

| Case 3 | Cytogenetics | 46, XY, i(7)(p10), t(9;11)(p22;q23)[6] 46, XY, i(7)(p10), t(4;12)(q12;p13)[5] Non-clonal aberration of clone 1: t(15;16)(q15;q22) FISH studies: 11.7% KMT2A translocation | 46, XY, i(7)(p10), t(4;21)(q12;q22), del(13)(q14q22)[16] 46, XX[4] | |

| RNA-seq | GABPB1::NUTM1 Elevated expression: FLT3 and LMO2 | |||

| DNA-seq | Negative | AMER1 (R1049*), BCOR (K395fs*47), DNMT3A (R882H), GATA2 (R362Q), IDH1 (R132C), PHF6 (Q37*), NF1 loss | ||

| Flow Cytometry | Flow cytometric analysis of the “blast” gate showed an increased population of myeloid blasts positive for HLA-DR, CD45, CD15, dim CD13, CD11b, and CD64, consistent with persistent acute myeloid leukemia | Expanded population of abnormal myelomonocytic blasts (67.5%) expressing CD4 (subset), CD9 (subset), CD11b (subset, dim), CD13 (increased), CD33 (dim), CD34, CD38, CD58 (dim), CD64, CD117, CD123 (moderate), HLA-DR, and MPO (subset) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tizro, P.; Chang, L.; Salhotra, A.; Arias-Stella, J.; Telatar, M.; Tomasian, V.; Gaal, K.; Song, J.; Soma, L.; Fuentes, S.; et al. Novel NUTM1 Fusions in Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Expanding the Genetic and Clinical Landscape. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311676

Tizro P, Chang L, Salhotra A, Arias-Stella J, Telatar M, Tomasian V, Gaal K, Song J, Soma L, Fuentes S, et al. Novel NUTM1 Fusions in Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Expanding the Genetic and Clinical Landscape. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311676

Chicago/Turabian StyleTizro, Parastou, Lisa Chang, Amandeep Salhotra, Javier Arias-Stella, Milhan Telatar, Vanina Tomasian, Karl Gaal, Joo Song, Lorinda Soma, Sandra Fuentes, and et al. 2025. "Novel NUTM1 Fusions in Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Expanding the Genetic and Clinical Landscape" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311676

APA StyleTizro, P., Chang, L., Salhotra, A., Arias-Stella, J., Telatar, M., Tomasian, V., Gaal, K., Song, J., Soma, L., Fuentes, S., Garcia, L., Fei, F., Munteanu, A., Marcucci, G., & Afkhami, M. (2025). Novel NUTM1 Fusions in Relapsed Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Expanding the Genetic and Clinical Landscape. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11676. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311676