2.3. The Effects of T. harzianum T4 and Microplastics on Plant Agronomic Traits

In this study exploring the impacts of

T. harzianum T4 and aged microplastics on the agronomic traits of

N. benthamiana, a series of intriguing findings emerged. When 320 mg/kg of aged microplastics (MP320) was applied alone, it significantly hindered the plant growth of

N. benthamiana (

Figure 3A). The height and weight were decreased by 7.33% and 21.17%, respectively, with a significant weight difference compared to the control (CK) (

Figure 3B,C). However, supplementing MP320 with

T. harzianum T4 (MP320+T4) shifted this trend, while height still declined (from 16.83 cm to 13.07 cm), weight significantly increased by 49.34% (from 5.56 g to 8.31 g) (

Figure 3B,C). Relative to the CK, the combined MP320+T4 treatment boosted plant weight by 17.72%. For the 80 mg/kg aged microplastic treatment (MP80), plant height and weight increased by 7.52% and 11.01% compared to the CK, respectively (

Figure 3B,C). When

T. harzianum T4 was added (MP80+T4), growth trends resembled MP320+T4. However, there was a significant height difference between MP80+T4 (19.53 cm) and MP80 (11.27 cm), but no significant differences in weight (7.84 g vs. 7.85 g), and the weight of MP80+T4 was slightly higher than that of MP80 (

Figure 3B,C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that high concentrations of aged microplastics significantly and negatively impact plant agronomic traits, while

T. harzianum T4 effectively mitigates microplastic stress, particularly at higher microplastic concentrations.

2.4. Effects of T. harzianum and Aged Microplastics on Chlorophyll, MDA, and O2−

Notably, when examining the impacts of

T. harzianum T4 and aged microplastics on chlorophyll, MDA, and ROS in

N. benthamiana, distinct patterns emerged. When

N. benthamiana was cultivated with aged microplastics, chlorophyll

a (C

a) content showed contrasting trends between the two microplastic concentrations: MP80 (0.38 mg/g) > CK (0.36 mg/g) > MP320 (0.31 mg/g) (

Figure 4A). This indicates low concentrations of aged microplastics slightly elevated C

a levels, while high concentrations significantly reduced C

a levels, suggesting a dose-dependent inhibition of photosynthesis. When

T. harzianum T4 was co-applied (MP80+T4 and MP320+T4), C

a content increased by 16.51% (MP80+T4 vs. MP80) and 26.08% (MP320+T4 vs. MP320), with both treatments exceeding CK levels (

Figure 4A). Notably, C

b in MP80 (0.21 mg/g) was 1.67% lower than the CK, while MP320 (0.25 mg/g) showed a 13.35% increase relative to the CK (

Figure 4B). An intriguing observation was the decrease in chlorophyll-

b content when

T. harzianum T4 was added to the aged microplastic treatments. The content was as follows: MP320 (0.25 mg/g) > MP320+T4 (0.23 mg/g) > CK (0.22 mg/g) > MP80 (0.21 mg/g) > MP80+T4 (0.20 mg/g) (

Figure 4B). In terms of carotenoids, compared to the CK, exogenous aged microplastics (with or without

T. harzianum T4) generally increased carotenoid content (

Figure 4C). However, similar to chlorophyll-

b,

T. harzianum T4 reduced carotenoid levels in aged microplastic-treated groups. The order was as follows: MP80 (0.055 mg/g) > MP80+T4 (0.051 mg/g) > MP320 (0.045 mg/g) > MP320+T4 (0.039 mg/g) > CK (0.027 mg/g) (

Figure 4C).

Compared with the control group (CK = 1094.85 µm/g), the content of superoxide anion radicals (O

2−) in the aged microplastic-treated groups (MP80 = 2056.37 µm/g and MP320 = 2328.58 µm/g) significantly increased, showing 1.88-fold and 2.13-fold changes, respectively (

Figure 4D,F). This indicates that aged microplastic treatment can elevate the content of superoxide anion radicals and induce oxidative stress. When compared with the corresponding aged microplastic-treated groups (MP80 and MP320), the MP80+T4 and MP320+T4 groups exhibited a significant reduction in superoxide anion free radical content, to only 39.48% and 32.89% of the respective microplastic-treated groups (MP80+T4 = 811.89 µm/g and MP320+T4 = 765.87 µm/g), and the superoxide anion generation rate was also significantly decreased (

Figure 4D,F). This suggests that the addition of

T. harzianum T4 can notably mitigate the accumulation of superoxide anion free radicals induced by microplastics and relieve oxidative stress.

The MDA content in the MP80 (18.22 nmol/g) and MP320 (24.71 nmol/g) groups was significantly higher than that in the control group (CK = 3.36 nmol/g), demonstrating that aged microplastic treatment exacerbated membrane lipid peroxidation in

N. benthamiana (

Figure 4G). As a product of membrane lipid peroxidation, MDA content increased by 5.43-fold in MP80 and 7.36-fold in MP320 relative to the CK (

Figure 4G). The MDA content in the MP80+T4 group (5.39 nmol/g) was significantly reduced to 29.57% of that in MP80, and the MP320+T4 group (7.20 nmol/g) showed a similar trend, decreasing to 29.15% of MP320 (

Figure 4G). These results indicate that

T. harzianum T4 treatment effectively mitigates membrane lipid peroxidation induced by aged microplastics, thereby protecting cell membrane structure and function. By reducing the accumulation of superoxide anion radicals and MDA,

T. harzianum T4 alleviates oxidative stress caused by aged microplastics.

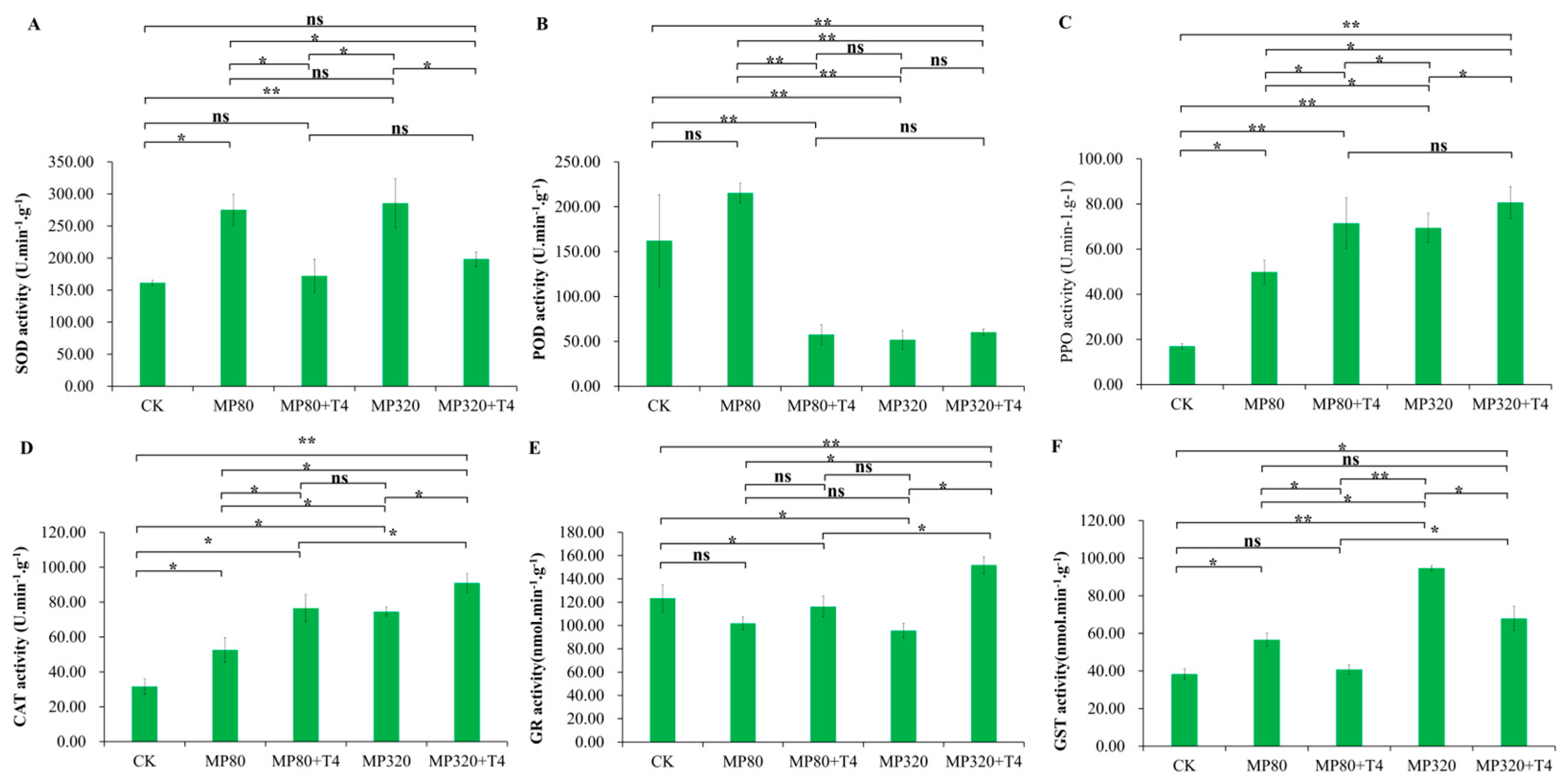

2.5. Effects of T. harzianum and Microplastics on Enzyme Activities

Low and high concentrations of microplastics (MP80 and MP320) both induced an increase in SOD activity, with MP80 (275.18 U·min

−1·g

−1) and MP320 (285.52 U·min

−1·g

−1) showing 1.7-fold and 1.77-fold increases compared to the control (CK, 161.40 U·min

−1·g

−1), respectively (

Figure 5A). When

T. harzianum T4 was combined with aged microplastics, SOD activity in the low-concentration group (MP80+T4) dropped significantly to 62.58% of the MP80 group (

Figure 5A). In the high-concentration group (MP320+T4), SOD activity significantly decreased by 30.53% compared to MP320, though it was 22.89% higher than the CK, which does not show significant difference (

Figure 5A). These results suggest that

T. harzianum T4 alleviates the microplastic stress-induced upregulation of SOD activity.

Aged microplastics induced concentration-dependent POD activity responses: a slight increase at low concentrations (MP80, 215.36 U·min

−1·g

−1) and a significant decrease at high concentrations (MP320, 51.71 U·min

−1·g

−1), with values ordered as MP80 > CK (162.26 U·min

−1·g

−1) > MP320 (

Figure 5B). In combined treatments with

T. harzianum T4, low-concentration MP80+T4 showed a sharp POD activity reduction (26.71% below MP80 and 35.45% below the CK), while high-concentration MP320+T4 (60.24 U·min

−1·g

−1) remained lower than the CK but was 1.16-fold higher than MP320 (

Figure 5B). Among all treatment groups, MP80 alone exhibited the highest POD activity, indicating a complex regulatory pattern of POD under microplastic stress and biological mitigation.

When

N. benthamiana was cultivated with aged microplastics, polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity increased at both low (MP80, 49.87 U·min

−1·g

−1) and high (MP320, 69.43 U·min

−1·g

−1) concentrations of microplastics compared to the control (CK), with MP320 showing a more pronounced induction (

Figure 5C). This indicates that aged microplastics can induce PPO activity in plants as a defense response to microplastic stress. Co-treatment with

T. harzianum T4 further enhanced PPO activity in a concentration-dependent manner: at low microplastic concentrations with

T. harzianum T4, MP80+T4 (71.47 U·min

−1·g

−1) exhibited a 1.43-fold increase over MP80 and a 4.21-fold increase over the CK; at high concentrations with

T. harzianum T4, MP320+T4 (80.63 U·min

−1·g

−1) showed a more significant rise, reaching 4.75-fold over the CK and 1.16-fold over MP320 (

Figure 5C). These findings suggest a synergistic effect between the defense mechanisms of

T. harzianum T4 and microplastic-induced stress, whereby

T. harzianum T4 promotes PPO production to enhance plant stress tolerance.

Exposure to aged microplastics significantly increased CAT activity compared to the control group (CK), with a clear concentration-dependent trend. CAT activity followed the order: MP320 (74.47 U·min

−1·g

−1) > MP80 (52.54 U·min

−1·g

−1) > CK (31.55 U·min

−1·g

−1) (

Figure 5D). When

T. harzianum T4 was co-applied with aged microplastics, CAT activity further increased in both MP80+T4 (76.51 U·min

−1·g

−1) and MP320+T4 (90.94 U·min

−1·g

−1) groups (

Figure 5D). Specifically, MP80+T4 showed a 1.46-fold increase over MP80, while MP320+T4 exhibited a 1.22-fold increase over MP320, maintaining the same concentration-dependent pattern as the microplastic-only treatments (

Figure 5D). These results highlight the coordinated antioxidant defense mechanism of

T. harzianum T4 in enhancing CAT activity under microplastic stress.

When

N. benthamiana was treated with aged microplastics, glutathione reductase (GR) activity showed concentration-dependent inhibition (

Figure 5E), with both low (MP80, 101.84 nmol·min

−1·g

−1) and high (MP320, 95.59 nmol·min

−1·g

−1) concentrations yielding lower activity than the blank control (CK, 123.28 nmol·min

−1·g

−1). This suggests that aged microplastics directly suppress GR-mediated glutathione recycling. However, co-treatment with

T. harzianum T4 significantly alleviated this inhibition: GR activity in MP80+T4 (116.13 nmol·min

−1·g

−1) and MP320+T4 (151.87 nmol·min

−1·g

−1) increased by 14.04% and 58.88% compared to microplastic-only groups, respectively, indicating restored redox homeostasis via enhanced glutathione regeneration (

Figure 5E).

In contrast, glutathione S-transferase (GST) displayed opposing trends: aged microplastics induced significant GST activity elevation, particularly at high concentrations (MP320, 94.71 nmol·min

−1·g

−1), which was 146.91% higher than the CK (38.36 nmol·min

−1·g

−1) (

Figure 5F). However,

T. harzianum T4 co-treatment attenuated this induction: GST activity in MP80+T4 (40.72 nmol·min

−1·g

−1) and MP320+T4 (67.87 nmol·min

−1·g

−1) decreased by 28% and 28.33% relative to MP80 (56.56 nmol. min

−1 g

−1) and MP320, respectively, despite remaining 6.16% and 76.94% higher than the CK (

Figure 5F). This suggests that the combined stressor disrupts GST-dependent detoxification pathways, potentially leading to toxic compound accumulation via reduced conjugative detoxification efficiency.

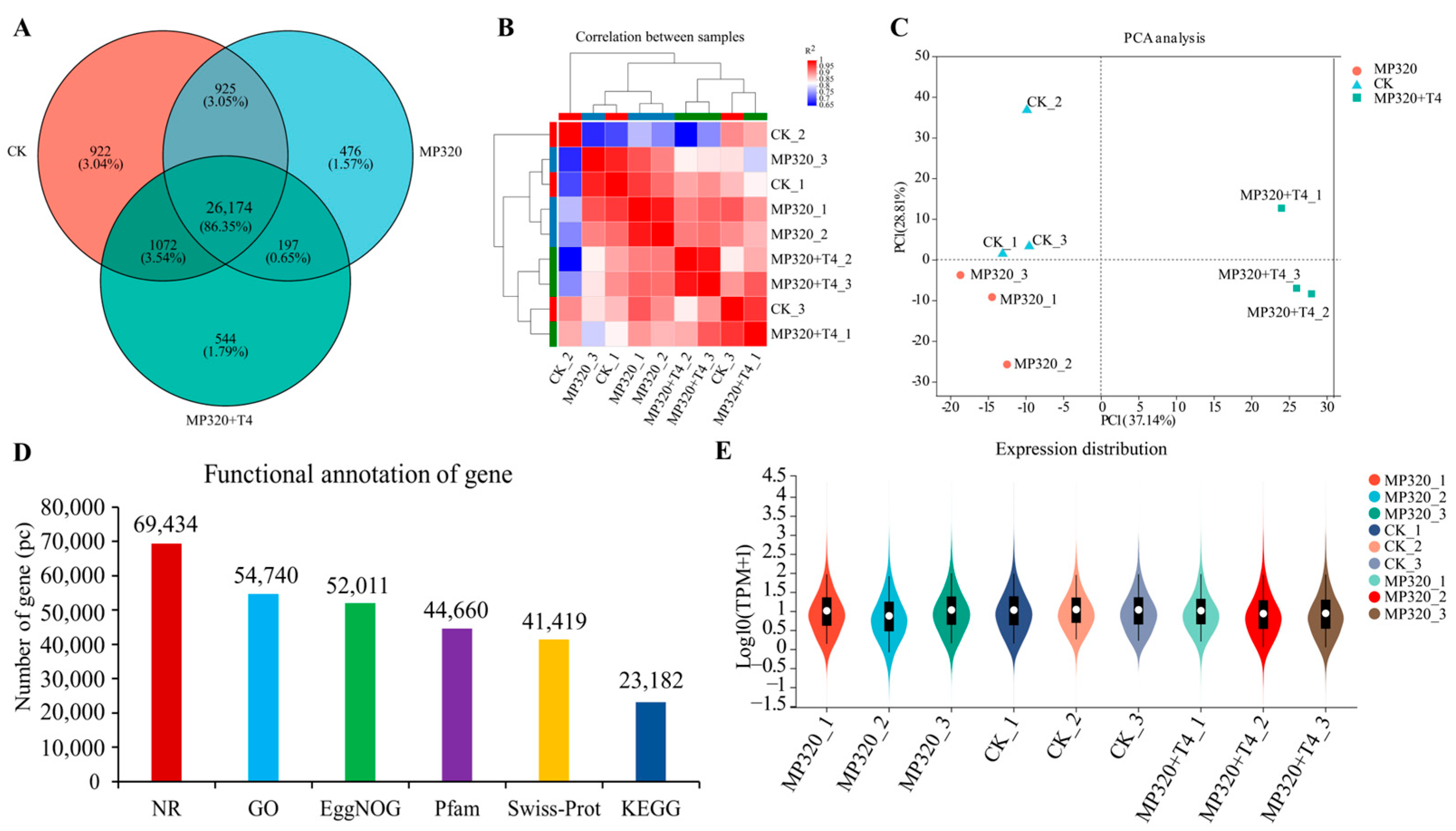

2.6. Effects of T. harzianum and Microplastics on N. benthamiana Gene Expression

In this study, RNA-seq was utilized to systematically explore the impact of high-concentration aged microplastics and

T. harzianum T4 on gene expression in

N. benthamiana. Following rigorous quality control and data filtering, the RNA-seq analysis generated 40.43–43.90 million clean reads (Q30 base ratio: 94.03–94.22%) from the CK library, 44.23–46.69 million reads (Q30: 94.03–94.18%) from the MP320 library, and 39.39–47.43 million reads (Q30: 94.05–94.08%) from the MP320+T4 library (

Supplementary Table S1). Mapping to the

N. benthamiana reference genome (Niben261;

https://solgenomics.net, accessed on 18 October 2024) yielded 39.71–43.10 million, 41.50–45.74 million, and 38.71–46.53 million aligned reads for the CK, MP320, and MP320+T4, respectively, with mapping rates of 98.17–98.23%, 97.97–98.16%, and 97.81–98.27% (

Supplementary Table S1). A total of 29,093, 27,772, and 27,987 genes were identified in the CK, MP320, and MP320+T4 groups (

Supplementary Table S2 and

Figure 6A). The high biological replicate correlation (R

2 > 0.99) validated the reliability of the transcriptomic data (

Figure 6B).

In the PCA analysis, PC1 (37.14%) and PC2 (28.81%) collectively explained 65.95% of the total variance. MP320 samples clustered distinctly on the left of the PC1 axis, forming a clear separation from the CK samples on the right, highlighting fundamental differences in gene expression profiles between the two groups. MP320+T4 samples were distributed between the two clusters with partial overlap with the CK, suggesting that

T. harzianum T4 may partially reverse MP320-induced expression changes while retaining a unique pattern. Tight intragroup clustering of samples reflected the high consistency of biological replicates. These results indicate that the core effect of MP320 treatment is captured along PC1, whereas the regulatory effect of

T. harzianum T4 primarily acts by modulating gene expression along PC2 (

Figure 6C). Genes were functionally annotated using EggNOG, PFAM, KEGG, Swissprot, GO, and NR databases (

Figure 6D). Annotation counts varied across databases: the NR database annotated the most genes (69,434), while KEGG annotated the fewest (23,182), reflecting differing coverage of gene functional annotations. A violin plot revealed distinct patterns of gene expression distribution across samples, with some (e.g., MP320 and the CK) showing varying degrees of dispersion, indicating differences in expression central tendency and spread between groups (

Figure 6E).

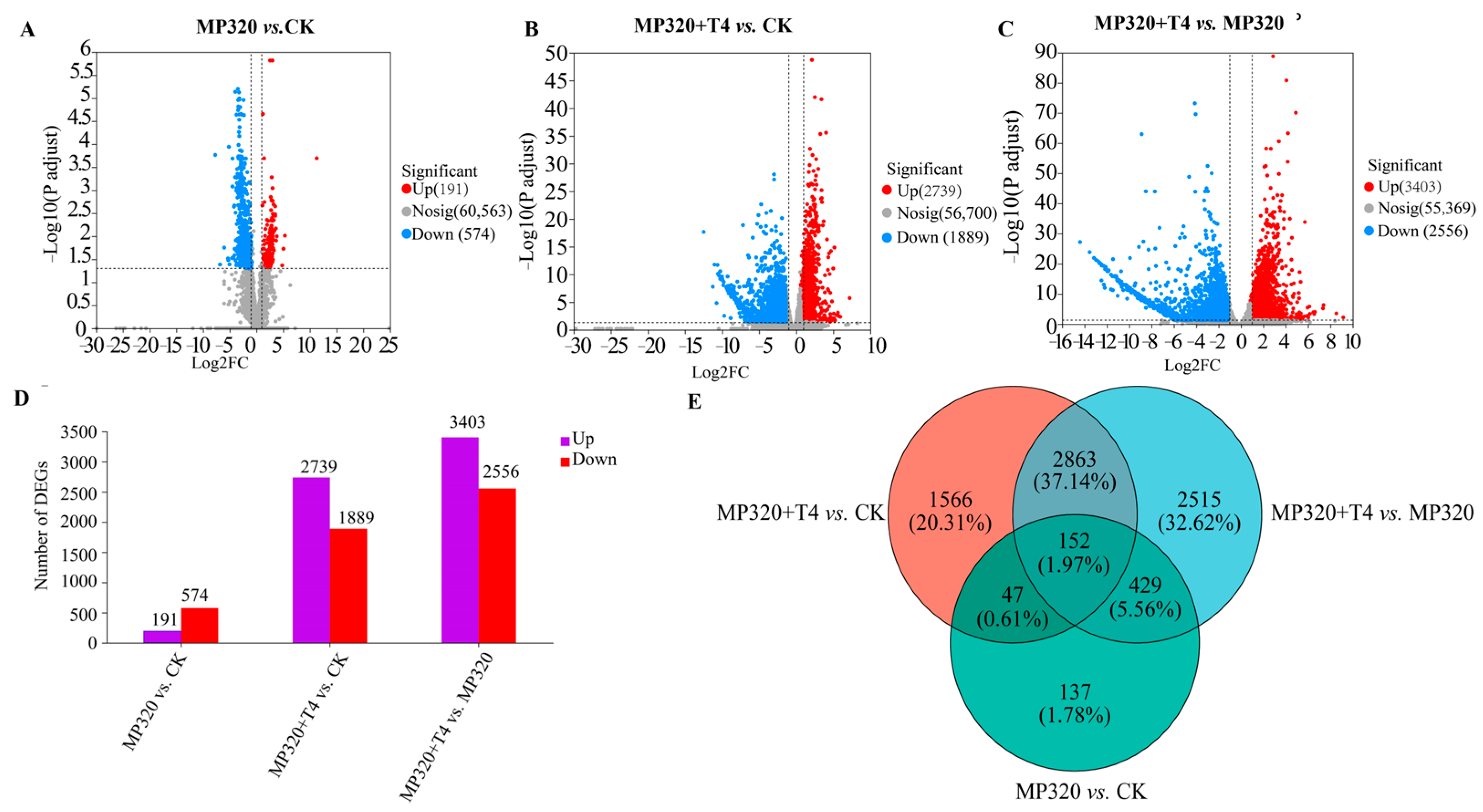

Using |log

2FC| > 2 and FDR < 0.05 as filtering criteria, a total of 7710 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in

N. benthamiana across the CK, MP320, and MP320+T4 groups (

Supplementary Tables S3–S5). Specifically, the comparisons MP320 vs. CK, MP320+T4 vs. CK, and MP320+T4 vs. MP320 yielded 765, 4628, and 5959 DEGs, respectively. Among these, 191, 2739, and 3403 DEGs were upregulated, while 574, 1889, and 2556 were downregulated in the three comparison groups (

Supplementary Tables S3–S5,

Figure 7A–D). A Venn diagram analysis revealed 152 common DEGs across all three comparisons (

Figure 7E).

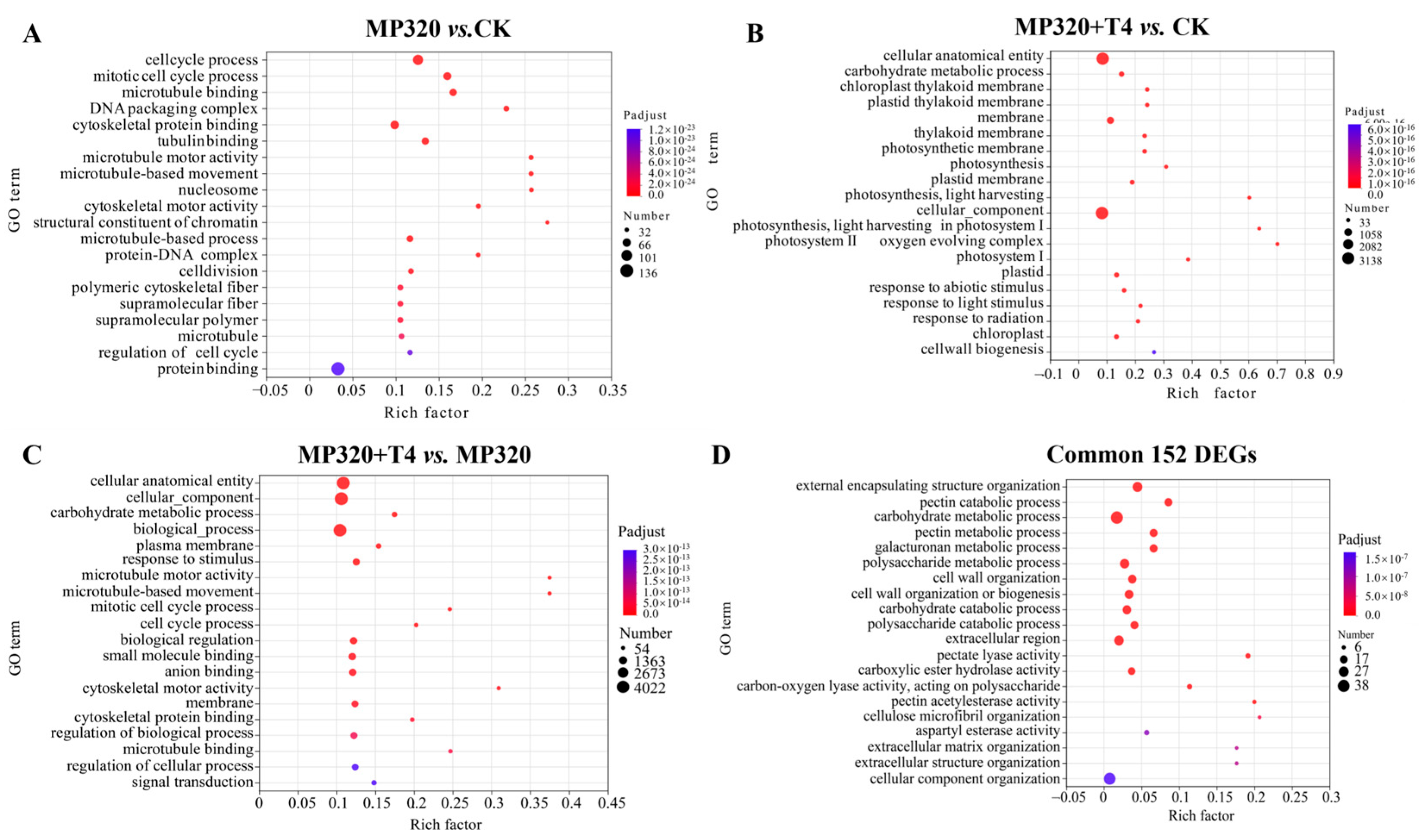

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was conducted to explore the roles of genes involved in

N. benthamiana responses to aged microplastics and

T. harzianum T4 across the biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF) categories. Aged microplastic exposure (MP320 vs. CK) induced significant enrichment of 765 DEGs in cell cycle regulation (e.g., cell cycle process,

p = 2.90 × 10

−58; mitotic cell cycle,

p = 1.47 × 10

−46) and cytoskeletal functions (e.g., microtubule binding,

p = 4.67 × 10

−42). Co-treatment with

T. harzianum T4 (MP320+T4 vs. CK) led to 4628 DEGs enriched in carbohydrate metabolism (

p = 3.11 × 10

−33) and chloroplast thylakoid membranes (

p = 6.22 × 10

−33), while MP320+T4 vs. MP320 (5959 DEGs) highlighted cellular organization (

p = 9.33 × 10

−45) and plasma membrane components (

p = 6.15 × 10

−21) (

Figure 8A–C). The 152 common DEGs across all comparisons were primarily associated with cell wall metabolism (e.g., pectin catabolic process,

p = 1.69 × 10

−19) and carbohydrate metabolic pathways (

p = 5.25 × 10

−19) (

Figure 8D). Collectively, aged microplastics predominantly altered BP/MF terms related to cell cycle and cytoskeletal dynamics, whereas

T. harzianum T4 co-treatment modulated processes such as carbohydrate metabolism and stimulus responses, reflecting distinct regulatory patterns of single and combined stressors.

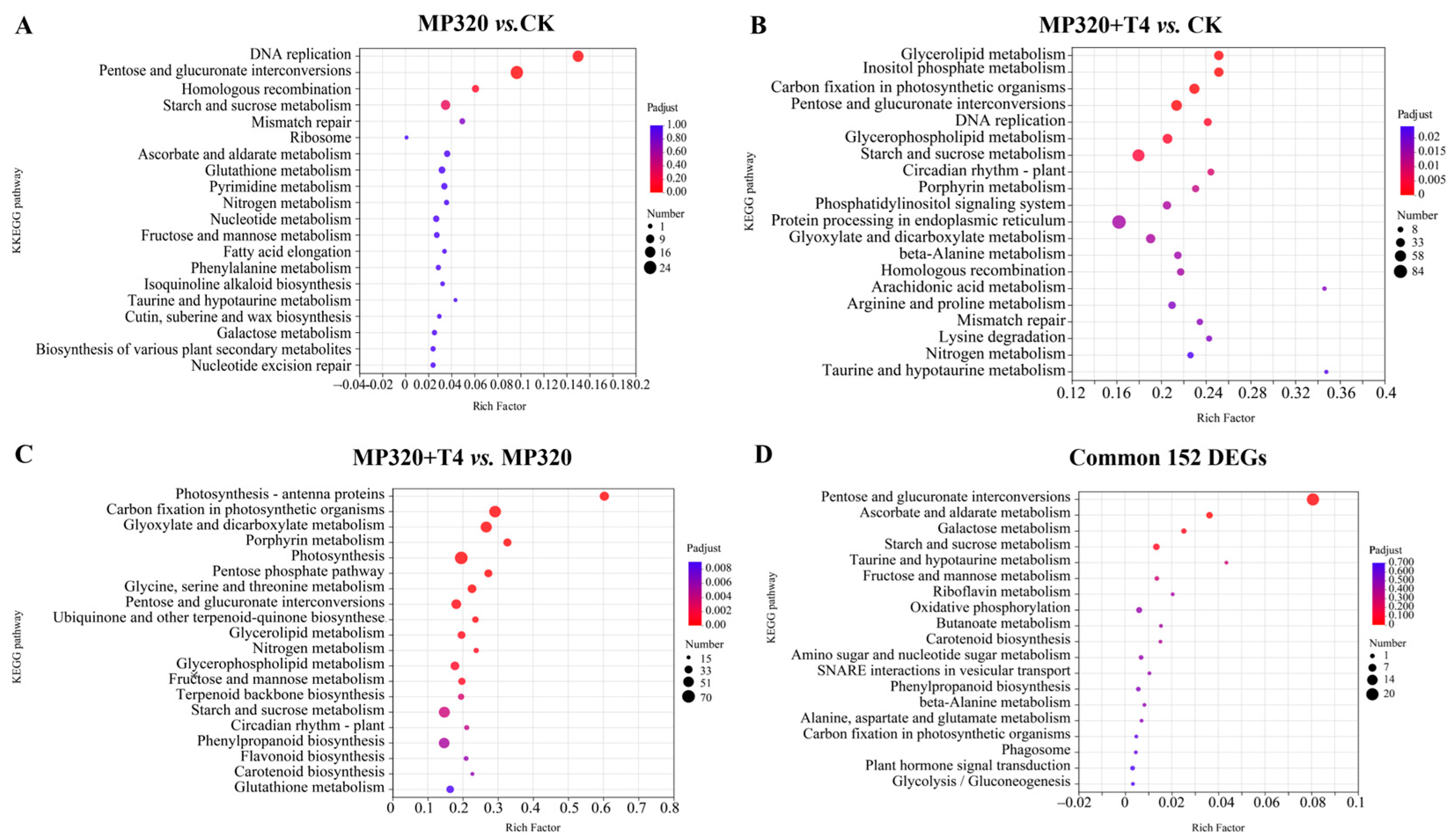

KEGG pathway analysis (

p < 0.05) revealed that DEGs from all comparisons groups were significantly enriched in 40 metabolic processes. In MP320 vs. CK, enrichment was observed in DNA replication (

p = 3.70 × 10

−10) and pentose/glucuronate interconversions (

p = 8.71 × 10

−10). MP320+T4 vs. MP320 highlighted inositol phosphate metabolism (

p = 1.21 × 10

−4), carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (

p = 1.34 × 10

−4), and glycerolipid metabolism (

p = 1.83 × 10

−4), while MP320+T4 vs. CK showed strong enrichment in photosynthesis-antenna proteins (

p = 2.76 × 10

−23), carbon fixation (

p = 1.52 × 10

−14), and glyoxylate/dicarboxylate metabolism (

p = 1.13 × 10

−11) (

Figure 9A–C). Notably, aged microplastics and

T. harzianum T4 co-treatment both impacted DNA replication and pentose/glucuronate interconversions, as exemplified by genes like Niben261Chr02g0822017 (log

2FC = −11.30 in MP320+T4 vs. MP320, 2.32 in MP320 vs. CK, −8.96 in MP320+T4 vs. CK) and Niben261Chr02g0958006 (log

2FC = −12.11, 2.52, −9.57 across the same comparisons). In DNA replication pathways, microplastic-suppressed genes (e.g., Niben261Chr01g1441013, Niben261Chr07g1000008) were upregulated by

T. harzianum T4 co-treatment, potentially linking to enhanced leaf expansion and plant biomass. For the 152 common DEGs, KEGG analysis identified enrichment in pentose/glucuronate interconversions, ascorbate/aldarate metabolism, starch/sucrose metabolism, and galactose metabolism (

Figure 9D). Key genes included Niben261Chr08g1038012 (log

2FC = −7.22, −10.02, 2.77) and Niben261Chr02g0822017 (log

2FC = −8.96, −11.30, 2.32) across comparisons. qRT-PCR validation of nine common DEGs (including

WRKY40,

WRKY40A, and

WRKY70 transcription factors) confirmed consistency with RNA-seq data, supporting transcriptome reliability (

Supplementary Figure S1). Based on functional annotation, fold changes, and agronomic trait correlations,

WRK40 (Niben261Chr08g0154013),

WRK40A (Niben261Chr18g1442002), and

CYPR4 (Niben261Chr10g0687008) were prioritized as candidate genes for functional characterization.

2.7. Metagenomic Data Description

This study performed metagenomic sequencing on nine samples (CK, MP320, MP320+T4;

n = 3 per group), generating 117.9 Gb of high-quality clean data with an average depth of 13.1 Gb/sample (

Supplementary Table S6). After assembly, gene prediction, and filtering of sequences < 100 bp, 1,396,407 (MP320), 1,338,769 (CK), and 1,425,188 (MP320+T4) genes were identified. Clustering at 90% identity and coverage yielded 3,920,991 non-redundant genes (total length: 1.97 × 10

9 bp; average length: 502.11 bp). Using a similarity threshold of ≥95% for abundance calculation, 2,514,763 (MP320), 2,496,018 (CK), and 2,553,272 (MP320+T4) genes were quantified (

Supplementary Table S6). Notably, the MP320+T4 microbiome harbored the highest gene richness (2,553,272 genes), exceeding both the MP320 (2,514,763) and CK (2,496,018) groups (

Supplementary Table S6).

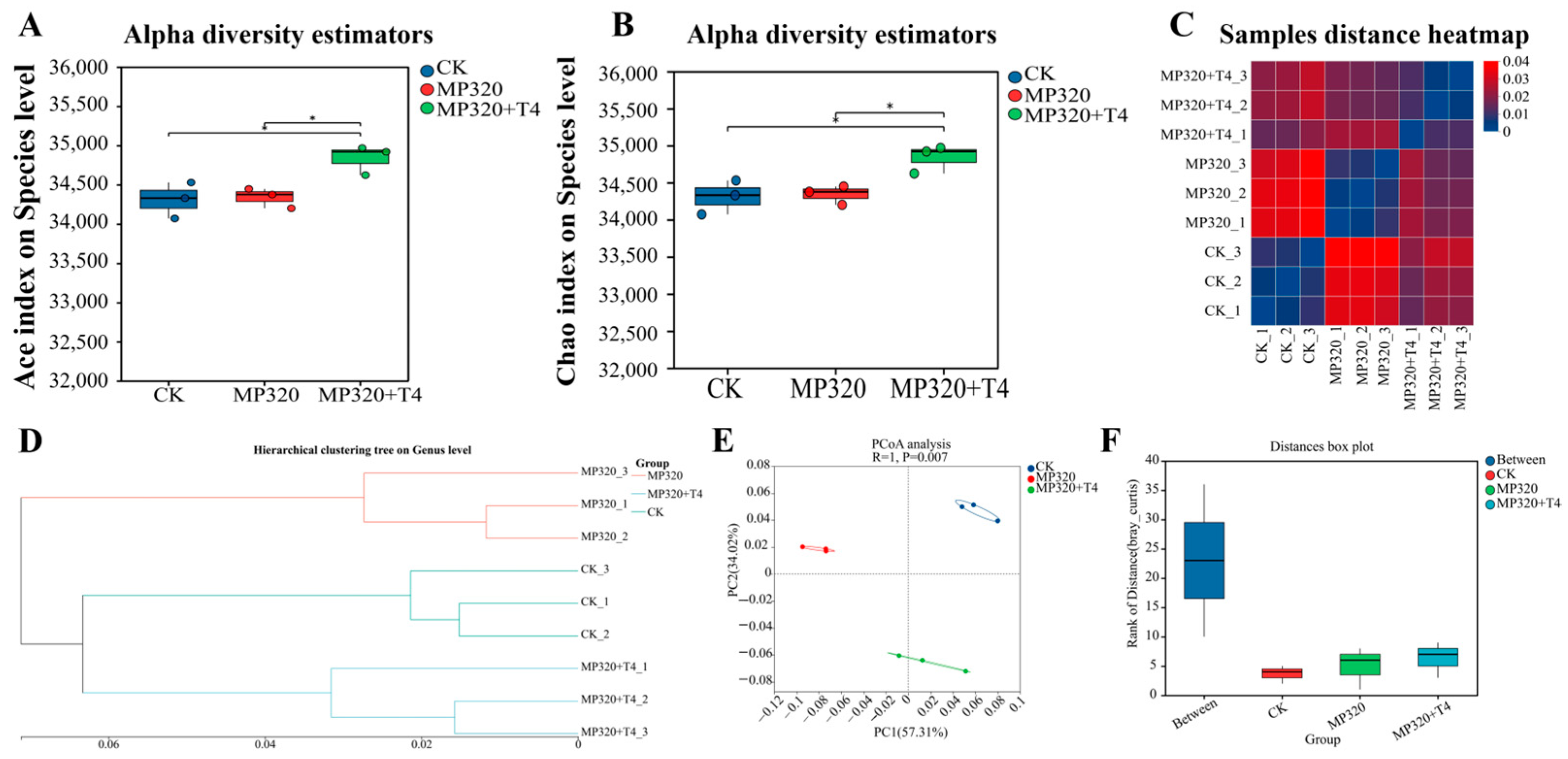

Alpha diversity analysis, which assesses microbial community richness and diversity via indices like Ace and Chao, revealed significant differences in Ace and Chao values between the MP320+T4 group and the other two treatments (MP320 and CK) (

Figure 10A,B). Hierarchical clustering analysis showed distinct clustering of the three treatments, aged microplastics, control, and microplastics combined with

T. harzianum T4, with significant inter-sample distance (

Figure 10C,D). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on the NR database demonstrated separation of the three groups, with PC1 explaining 57.31% of the variance (

Figure 10E), indicating significant differences in overall sample composition. Analysis of similarity (ANOSIM), a nonparametric test for comparing between-group versus within-group differences, confirmed the highest rank of between-group distances (

Figure 10F), validating the biological significance of the sample grouping.

2.8. Classification of the Microbiome

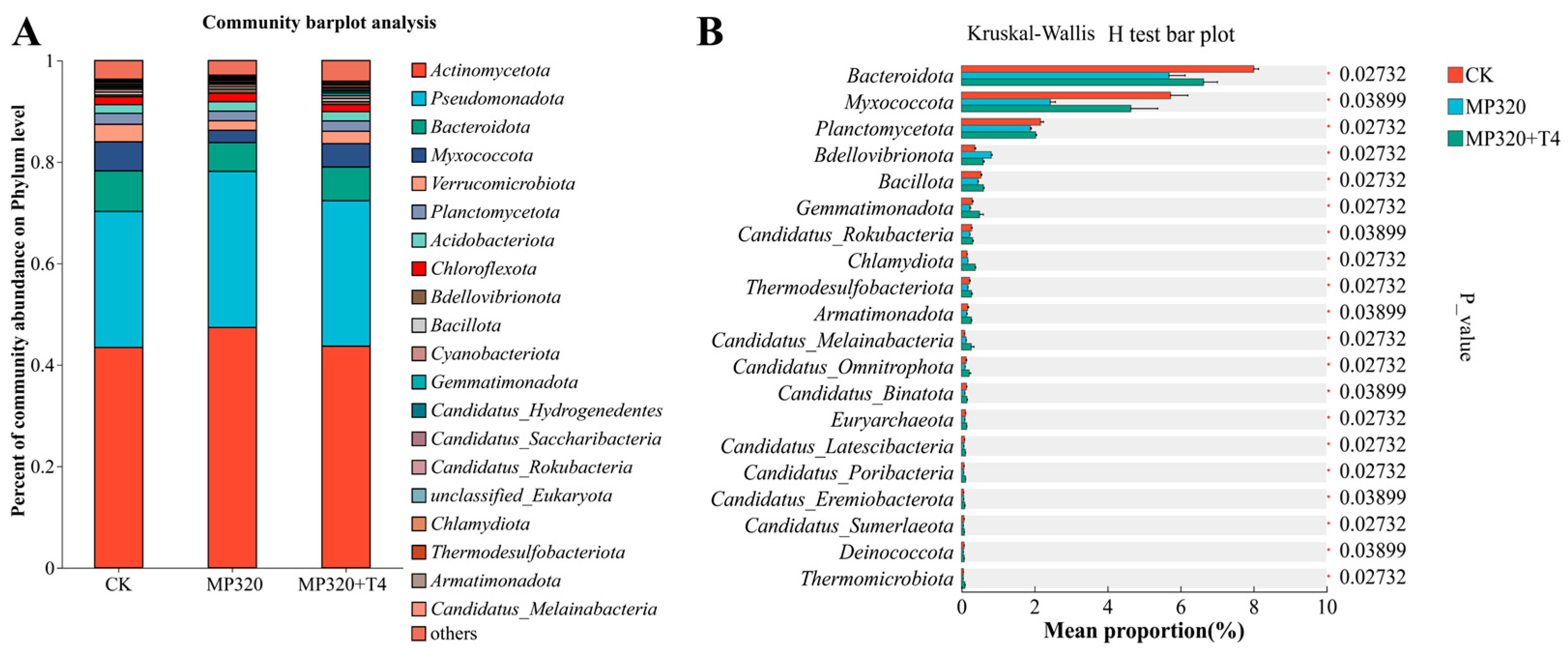

Non-redundant gene sets were annotated against the NR database to characterize species composition. At the phylum level,

Actinomycetota (49.47%),

Pseudomonadota (25.29%),

Bacteroidota (6.42%), and

Myxococcota (5.22%) dominated across all three treatment groups. Specifically, the control group (CK) showed

Actinomycetota (43.42%) and

Pseudomonadota (26.82%), while MP320 significantly increased

Actinomycetota (47.36%) and

Pseudomonadota (30.76%). In contrast, MP320+T4 reduced these phyla to 43.68% and 28.69%, respectively, while increasing

Bacteroidota (

p = 0.027),

Myxococcota (

p = 0.039), and

Planctomycetota (

p = 0.027) (

Figure 11A;

Supplementary Table S7). Aged microplastics alone induced significant shifts:

Actinomycetota and

Pseudomonadota abundances rose, whereas

Bacteroidota dropped sharply (

Figure 11B).

T. harzianum T4 co-treatment further modulated the microbiota, notably elevating

Bacteroidota and

Myxococcota and decreasing

Bdellovibrionota relative to MP320 (

Figure 11A). These results indicate that

T. harzianum T4 alters the structure and diversity of

N. benthamiana soil microbial communities.

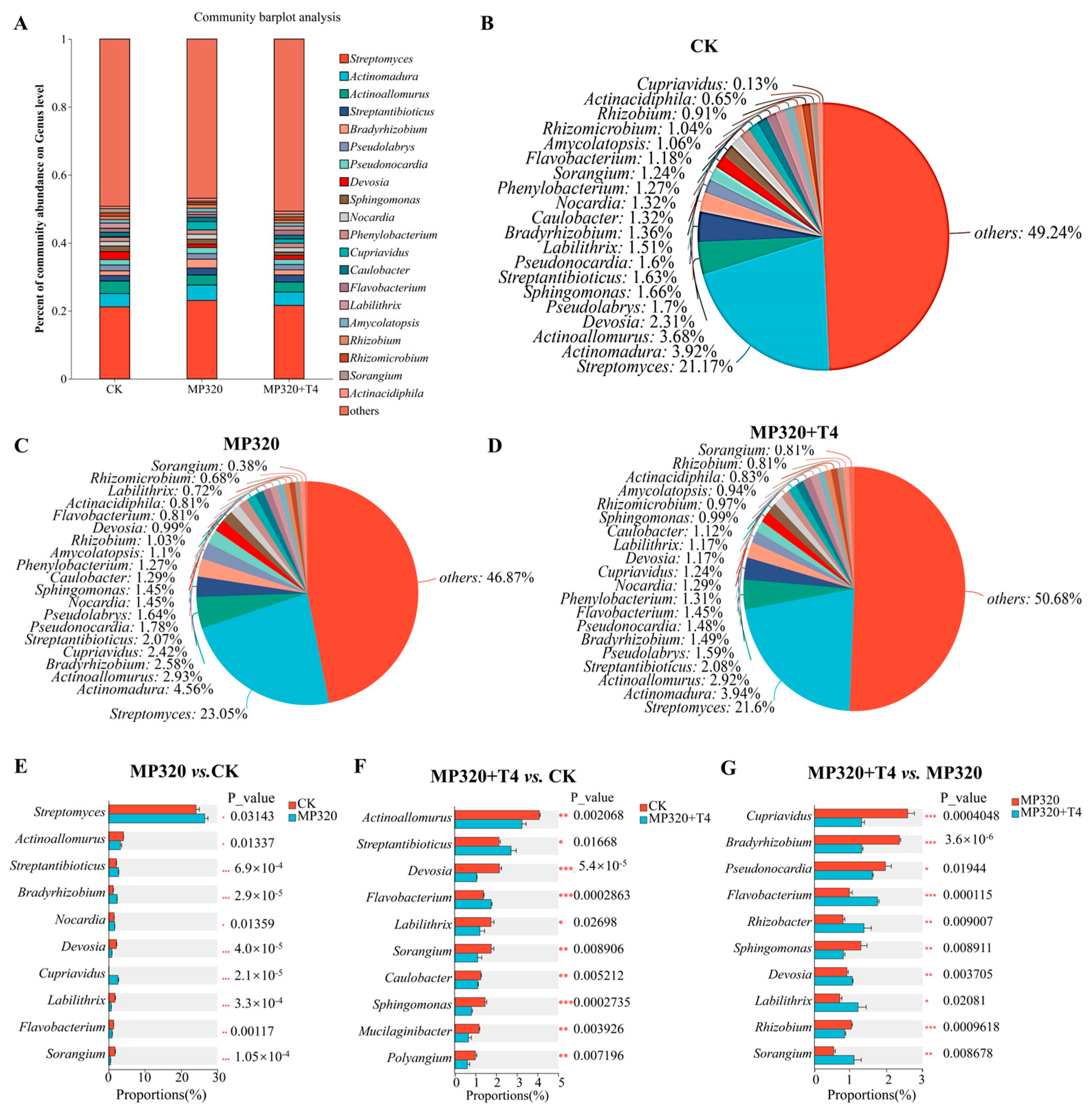

At the genus level, the control group was dominated by

Streptomyces (21.17%),

Actinomadura (3.92%), and

Actinoallomurus (3.68%). These genera remained dominant in both aged microplastic (MP320) and MP320+T4 treatments (

Figure 12A–D). However, aged microplastics alone significantly increased

Streptomyces,

Streptantibioticus, and

Cupriavidus abundances while reducing

Actinoallomurus and

Devosia (

Figure 12C–E). In the MP320+T4 group,

Streptomyces,

Actinomadura, and

Actinoallomurus remained predominant (

Figure 12D–F). The statistical analysis revealed distinct shifts, in which

Sphingomonas,

Pseudonocardia,

Bradyrhizobium, and

Cupriavidus were significantly reduced, whereas

Labilithrix,

Rhizobacter, and

Flavobacterium showed increased abundance (

Figure 12G).

2.9. Diversity, Abundance, and Classes of the Drug Resistance and Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes

To characterize antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in soil metagenomes across three treatments, 1359 ARGs were identified via CARD database comparison and categorized into 36 resistance classes. Multidrug resistance dominated (40.72% of total ARGs), followed by peptide, tetracycline, glycopeptide, and triclosan resistance, which collectively accounted for 31.85% (CK), 31.56% (MP320), and 31.64% (MP320+T4) of total ARGs (

Figure 13A–C). Multidrug resistance ARG abundance was significantly higher in aged microplastic and

T. harzianum T4-treated soils than in the CK (

Figure 13A–C). Among 36 classes, multidrug resistance harbored the most unique ARGs (553, e.g.,

gyrA, efflux pumps,

bla families), followed by aminoglycoside (94, e.g.,

AAC (3),

AAC (6′)), glycopeptide (80, e.g.,

vanS,

vanR), peptide (74), and tetracycline (75) (

Supplementary Table S8;

Figure 13D–F). Identified resistance mechanisms included reduced permeability, target alteration/replacement/protection, efflux, and inactivation (

Supplementary Table S8). Core ARGs (occurrence ≥ 90%, abundance > median) numbered 568 (CK), 577 (MP320), and 582 (MP320+T4), primarily associated with multidrug, tetracycline, glycopeptide, and peptide resistance. Statistical analyses revealed 18 significantly different classes in MP320 vs. CK (e.g.,

tetA5,

van,

fabG;

Figure 13G), 12 in MP320+T4 vs. CK (e.g.,

tetA,

novA,

fusA;

Figure 13H), and 10 in MP320+T4 vs. MP320 (e.g.,

tetA58,

vanR,

fabG;

Figure 13I). Crossgroup comparisons identified 14 significantly different classes, with tetracycline (

p = 0.004), glycopeptide (

p = 0.005), and triclosan (

p = 0.004) being most abundant (

Figure 13J).

In the analysis of virulence factors (VFs) in soil metagenomes across three treatments, 1032 VFs were annotated and categorized into 13 functional classes, including immune modulation, effector delivery systems, nutritional/metabolic factors, adherence, stress survival, antimicrobial activity/competitive advantage, biofilm formation, regulation, exoenzymes, exotoxins, invasion, motility, post-translational modification, and others. The CK group exhibited a baseline distribution of VF functions, with nutritional/metabolic factors accounting for 26%; immune modulation, 21%; and adherence, 8% (

Supplementary Table S9;

Figure 14A). Aged microplastic treatment (MP320) slightly altered this composition, increasing nutritional/metabolic factors to 27%, while decreasing adherence to 7%, indicating stress-induced shifts in virulence profiles. Co-treatment with

T. harzianum T4 (MP320+T4) further rebalanced VF distributions: nutritional/metabolic factors decreased to 25% compared to the CK, while effector delivery systems and motility each increased by 1% (

Supplementary Table S9;

Figure 14A). Statistical analyses revealed significant intergroup differences: MP320 vs. CK showed altered proportions of nutritional/metabolic factors (

p = 0.004716) and immune modulation (

p = 0.01279), whereas MP320+T4 vs. MP320 highlighted shifts in nutritional/metabolic factors (

p = 0.0272) and effector delivery systems (

p = 0.00382), indicating

T. harzianum T4-mediated reversal of microplastic-induced VF changes (

Figure 14B). Crossgroup comparisons identified significant differences in regulatory functions and antimicrobial/competitive advantage activities (e.g., regulation

p = 0.000721 for MP320+T4 vs. CK), reflecting complex adjustments to the microbial virulence network under combined stress (

Figure 14B). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that

T. harzianum T4 modulates the impact of aged microplastics on soil microbial virulence factor profiles.

To characterize carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) in soil metagenomes across three treatments, 687 CAZy families were identified via comparison with the CAZy database and categorized into seven classes: auxiliary activities (AAs), carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs), carbohydrate esterases (CEs), glycoside hydrolases (GHs), glycosyl transferases (GTs), polysaccharide lyases (PLs), and cellulosome modules (SLHs) (

Supplementary Table S10;

Figure 15). Glycoside hydrolases (GHs) were the most abundant class, followed by GTs, CEs, and AAs (

Figure 15A–C), with similar diversity patterns across treatments (

Figure 15D–F). All groups showed consistent trends in class abundance (

Figure 15G–I), with the CE1 family (CE class) being the most prevalent, followed by GT4, GT2_Glycos_transf_2, and GT41. These four families accounted for 22.08% (CK), 22.3% (MP320), and 22.92% (MP320+T4) of total CAZy abundance (

Figure 15D–F). Among classes, GHs harbored the most unique CAZymes (370, e.g., GH179, GH2, GH177, GH18 families), followed by GTs (114, e.g., GT4, GT2_Glycos_transf_2, GT41) and PLs (88) (

Figure 15G–I). Statistical analyses revealed significant differences in five classes between MP320 and the CK, two classes between MP320+T4 and MP320, and six classes between MP320+T4 and the CK (

Figure 16A–C). Crossgroup comparisons showed significant variations in all CAZy classes except SLHs (

Figure 16D).

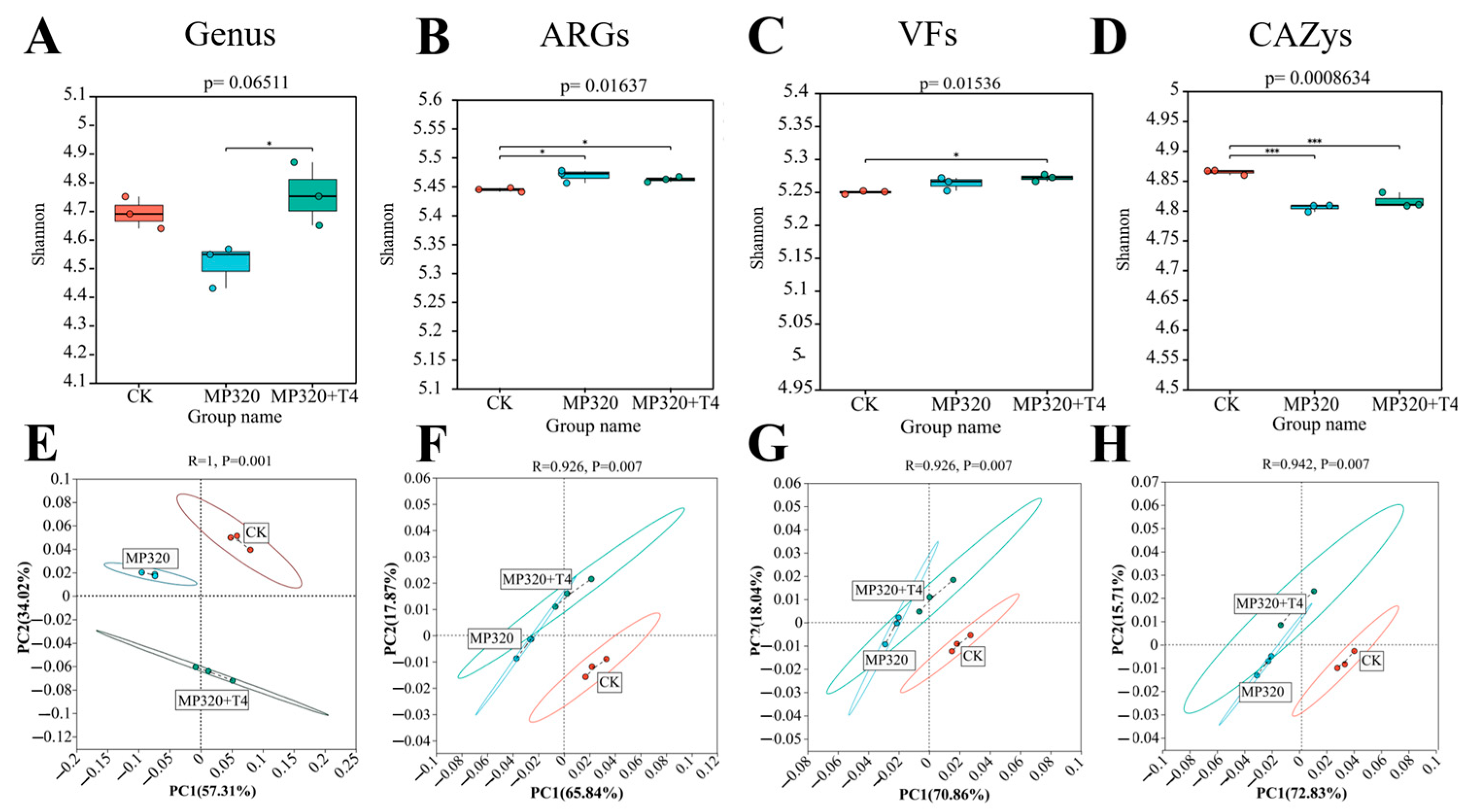

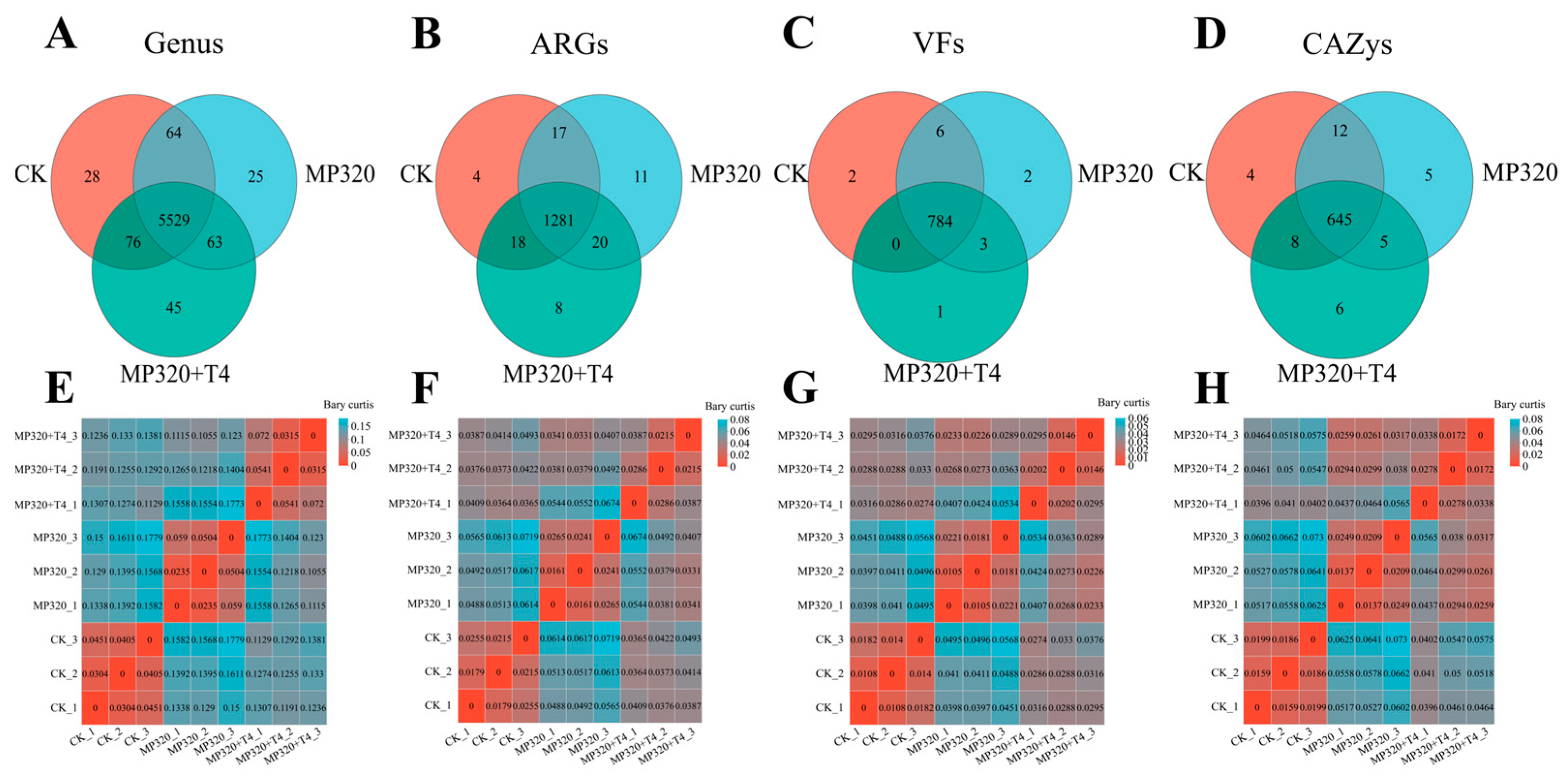

2.10. Diversity of ARGs, CAZy, VFs, and Genera Across Metagenomes

Cross-group comparisons of ARGs, CAZymes, VFs, and genus-level microbial communities (CK, MP320, MP320+T4) revealed distinct diversity patterns.

T. harzianum T4 addition increased microbial genus diversity relative to both MP320 and the CK, with the lowest diversity observed in MP320 (

Figure 17A). Consistently, ARG Shannon diversity was higher in MP320 and MP320+T4 vs. CK, with similar trends in VF diversity (

Figure 17B,C). In contrast, aged microplastics reduced CAZy alpha diversity, which was partially restored by T4 co-treatment (

Figure 17D). These results highlight the positive regulatory effect of

T. harzianum T4 on the diversity of soil microbial functions and communities.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of microorganisms, ARGs, VFs, and CAZys revealed distinct clustering patterns across the three groups. At the genus level, both aged microplastics and

T. harzianum T4 significantly altered microbial community composition (

Figure 17E). Notably, ARGs, VFs, and CAZys showed significant spatial separation along PC1 and PC2 axes among the CK, MP320, and MP320+T4 (

Figure 17F,G). Adonis analysis confirmed strong correlations between PC1 and PC2 (R > 0.9,

p < 0.01), with tight intragroup clustering reflecting high sample similarity. MP320 and MP320+T4 exhibited partial overlap and distinct separation, indicating that

T. harzianum T4 introduces unique functional shifts while retaining some similarities to the MP320 group.

2.12. Contribution and Correlation Analysis of Species to ARGs, VFs, and CAZys

The top 10 most abundant ARGs primarily included antibiotic-resistant

fabG, ATP-binding cassette (ABC) antibiotic efflux pumps, daptomycin-resistant

liaR, and serine/threonine kinase families. Except for Functions 01 and 07, all other resistance mechanisms involved antibiotic efflux, highlighting the dominance of ABC transporter-related genes. Function 01 (antibiotic-resistant

fabG family) and Functions 02–04 (antibiotic efflux pump families),

Streptomyces and

Actinomadura, contributed substantially. For example, in Function 03,

Streptomyces accounted for 31.25% (CK), 31.69% (MP320), and 30.69% (MP320+T4), while

Actinomadura contributed 4.95%, 5.79%, and 5.08% across the same groups, with observable intergroup fluctuations validated by heatmap analysis (

Supplementary Figure S2). Functions 05 (MFS antibiotic efflux pump family) and 06 (daptomycin-resistant liaR family) showed shifted contribution patterns.

Actinoallomurus increased from 7.82% (CK) to 8.94% (MP320), while adding

T. harzianum T4 slightly decreased the proportion (8.01%) compared to MP320. Meanwhile,

Streptomyces decreased from 30.59% (CK) to 29.56% (MP320+T4). In Functions 07 (serine/threonine kinase family)-10 (antibiotic efflux pump family), complex species contributions were observed. For instance,

Streptantibioticus contributed 3.01–5.2% in Function 07, while Function 10 involved

Streptomyces,

Actinomadura,

Actinoallomurus,

Streptantibioticus, and

Pseudonocardia as major contributors, with

Devosia,

Nocardia, and others playing secondary roles.

Streptomyces dominated across multiple functions, emerging as a key contributor to microbial community resistance mechanisms, while species like

Nocardia and

Devosia played minor roles. Heatmap analysis of Functions 05–06 further confirmed

Streptomyces’s pivotal role in these resistance pathways.

In terms of VFs, the top 10 abundance functions involve microbial movement, biofilm formation, nutrient uptake, regulation of cell wall viscosity, and promotion of cell void formation to facilitate movement, adhesion, and invasion. Across the CK, MP320, and MP320+T4 groups, significant variations in species contribution proportions were observed for each function. For instance, in Function 01 (Polar flagella),

Streptomyces accounted for 23.38% (CK), 24.33% (MP320), and 23.31% (MP320+T4), demonstrating how different treatments altered the microbial community structure and, consequently, species contributions to VF functions (

Supplementary Figure S2). Species contributions varied by function.

Streptomyces and

Actinomadura were key contributors to Function 03 (Trehalose-recycling ABC transporter), whereas

Actinoallomurus played a more prominent role in Function 05 (Beta-haemolysin/cytolysin), highlighting that distinct VF functions rely on specific species combinations.

Streptomyces emerged as the dominant contributor across most functions. In Function 08 (MymA operon),

Streptomyces represented 23.31% (CK), 23.13% (MP320), and 22.73% (MP320+T4). In contrast,

Nocardia and

Devosia consistently contributed less than 5% across functions, indicating minimal involvement in VF expression (

Supplementary Figure S2). Collectively, bar charts and heat maps confirmed that treatments modified microbial community composition and functional contribution patterns, with

Streptomyces,

Actinomadura, and

Actinoallomurus as major contributors and

Nocardia and

Devosia playing minor roles.

Analysis of the top 10 carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZys) revealed functions dominated by three enzyme classes: carbohydrate esterases, glycoside hydrolases, and glycosyl transferases, with

Streptomyces and

Actinomadura as major contributing species. Intergroup comparisons showed distinct species contribution ratios across functions. For example,

Streptomyces contributed 15.43% (CK), 18.31% (MP320), and 15.8% (MP320+T4) in Function 01, illustrating how microplastic and

T. harzianum T4 treatments altered microbial community structure and functional contributions (

Supplementary Figure S2). Species contribution patterns varied by function. While

Streptomyces and

Actinomadura were consistently significant, their proportions in Function 03 were notably lower than in other functions, highlighting that different CAZy functions rely on distinct species combinations.

Streptomyces emerged as the predominant contributor across most functions, underscoring its central role in carbohydrate metabolic pathways.

Collective analysis of ARGs, VFs, and CAZys revealed that Streptomyces dominated functional contributions across most categories, with consistently high abundance ratios and contribution values. While Actinomadura and Actinoallomurus contributed to specific functions, their proportions were consistently lower than Streptomyces. In contrast, species like Nocardia and Devosia showed minimal functional involvement across all categories. These findings highlight Streptomyces as the keystone species in the microbial community, with distinct species contribution profiles across functions. The observed functional shifts underscore how treatment factors alter community structure, driving specific species combinations to mediate metabolic and resistance pathways.

2.13. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of Metagenomic Functional Genes

Functional gene annotation against the KEGG database identified 15,657 metabolic pathways across three treatment groups, including 297 KOs involved in carbon metabolism and 58 KOs in nitrogen metabolism. Kruskal–Walli’s rank sum tests (

p < 0.05) with Tukey–Kramer correction (Q = 0.95) identified 2365 significantly differentially abundant KOs, spanning pathways such as microbial metabolism in diverse environments, amino acid biosynthesis, quorum sensing, pyruvate metabolism, amino sugar/nucleotide sugar metabolism, fatty acid metabolism, and glyoxylate/dicarboxylate metabolism. Key genes included

rpoE (RNA polymerase sigma-70 factor),

qor (NADPH: quinone reductase),

acd (acyl-CoA dehydrogenase), and

fadD (long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase) (

Supplementary Figure S3). For nitrogen metabolism, 14 significant KOs were identified, primarily involving alanine/aspartate/glutamate metabolism, glyoxylate/dicarboxylate metabolism, and purine metabolism, with representative genes

cynT (carbonic anhydrase),

gdhA (glutamate dehydrogenase), and

nrtB (nitrate/nitrite transporter). In carbon metabolism, 14 KOs were significant, covering carbon fixation, glyoxylate/dicarboxylate metabolism, pyruvate/methane/butanoate metabolism, and lipoic acid metabolism, featuring

atoB (acetyl-CoA C-acetyltransferase),

fdoG (formate dehydrogenase), and

frmA (hydroxymethylglutathione dehydrogenase) (

Supplementary Figures S3 and S4). Genus-level contribution analysis revealed that

Streptomyces,

Actinomadura,

Actinoallomurus, and

Pseudonocardia contributed to diverse metabolic pathways (e.g., microbial metabolism, two-component systems, ABC transporters), while

Phenylobacterium played a key role in nitrogen metabolism-related amino acid biosynthesis.

Caulobacter specifically contributed to carbon fixation and pyruvate metabolism (

Supplementary Figure S4).

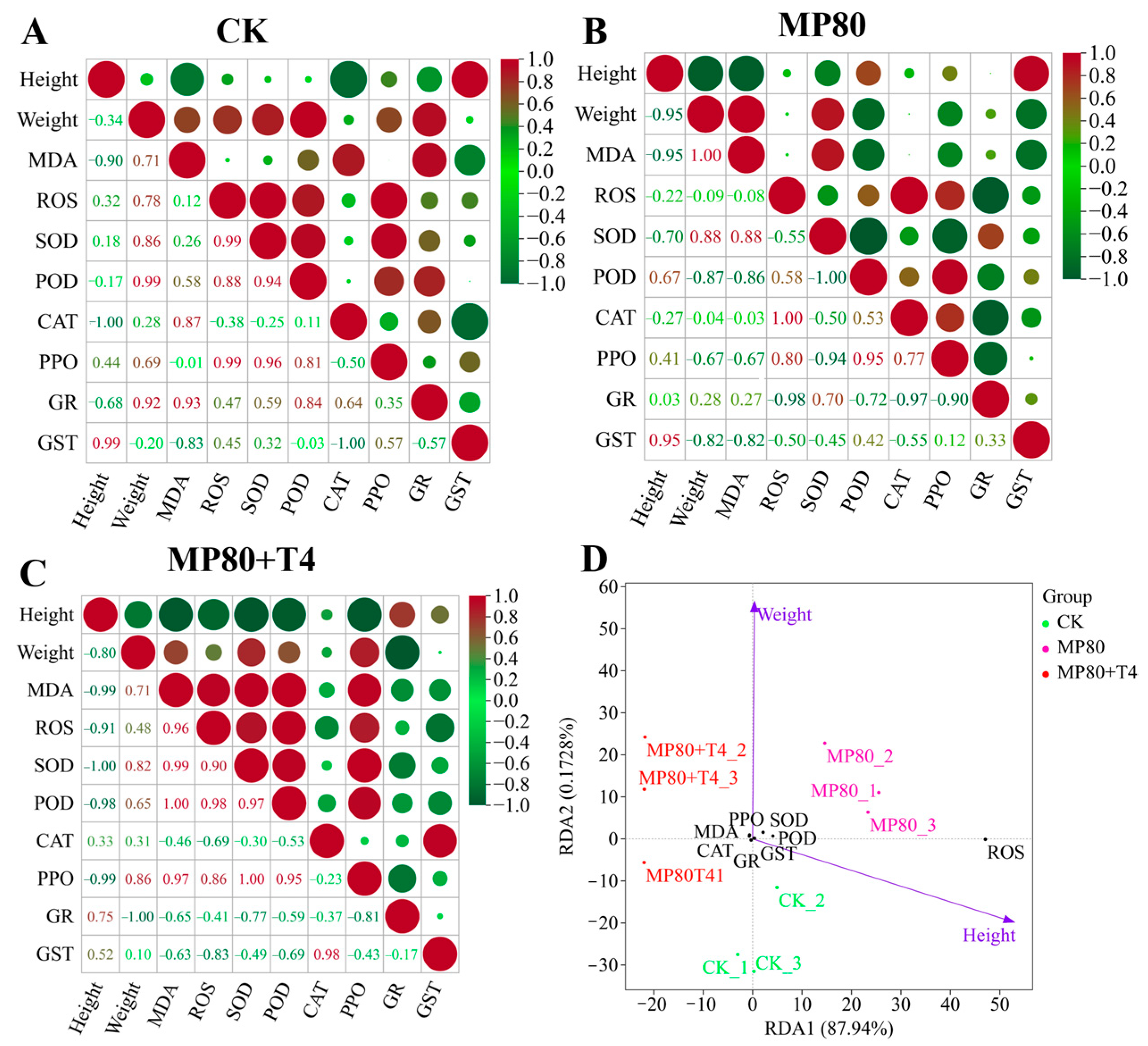

2.14. Correlation Analysis Between Multiple Indicators and Agronomic Traits

Correlation analysis and RDA analysis were conducted on agronomic traits, stress-related enzyme activities, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified by transcriptome screening, dominant bacterial genera selected by metagenomic analysis, AGR, virulence factors (VFs), carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZys), and other indicators across different treatment groups. Correlation analysis revealed a basic correlation pattern among various indicators (height, weight, MDA, ROS, antioxidant enzymes, etc.) of the control group (CK). In the control group (CK), height was strongly positively correlated with the detoxification enzyme GST (r = 0.99) and strongly negatively correlated with the antioxidant enzyme CAT (r = −1.00), reflecting the precise regulation of plant height growth and the detoxification antioxidant enzyme system under blank conditions (

Figure 19A). In addition, height was strongly negatively correlated with the membrane damage index MDA (r = −0.90), reflecting the negative feedback of basal growth stress injury. There is a strong positive correlation between weight and antioxidant enzyme POD (r = 0.99), indicating that the antioxidant system dominated by POD plays a core supporting role in maintaining weight biomass. At the same time, weight is significantly positively correlated with MDA (r = 0.71), suggesting that under basic conditions, weight accumulation is accompanied by certain natural membrane damage, constructing a synergistic steady state (

Figure 19A). In the low concentration microplastic group (MP80), there was a strong negative correlation between height and weight (r = −0.95), as well as MDA (r = −0.95), reflecting the deep binding between plant height growth and biomass accumulation, and membrane damage formation under aged microplastic stress (

Figure 19B). Weight is negatively correlated with antioxidant enzymes SOD (r = −0.09) and POD (r = −0.87), indicating that microplastic stress breaks the positive support of antioxidant enzymes for weight and the antioxidant system regulates passively (

Figure 19B). Adding

Trichoderma to the aged microplastics treatment (MP80+T4), height was strongly negatively correlated with SOD (r = −1.00) and POD (r = −0.98).

Trichoderma induced a shift in antioxidant strategy, prioritizing stress resistance (

Figure 19C). Weight is positively correlated with SOD (r = 0.82) and POD (r = 0.65) and positively correlated with MDA (r = 0.71).

Trichoderma repairs the positive correlation between antioxidant enzymes and weight and reconstructs the relationship between stress resistance and growth (

Figure 19C). In the high concentration aged microplastic group (MP320), the negative correlation between height and the WRKY70 gene was enhanced, and the positive correlation with dominant bacterial genera disappeared (

Supplementary Figures S5 and S6). Weight was negatively correlated with the

WRKY40/

WRKY40A gene (originally positively correlated), and the correlation with the ARG/VF/CAZy functional pathway was disrupted, revealing the destructive effect of high concentration of microplastics on the growth regulatory network and the collapse of the correlation system. When

Trichoderma was added to the high concentration of microplastics group (MP320+T4), the correlation between height and the

WRKY70 gene and the

CYPR4 gene returned to the CK group (

Supplementary Figure S7). The positive correlation between weight and the WRKY40/WRKY40A gene was restored, and a strong positive correlation (r increase) with GR enzyme activity was observed (

Supplementary Figure S7). The negative correlation with dominant bacterial genera was reduced to a weak positive correlation.

Trichoderma repaired the association network between height, weight, genes, enzyme activity, and microorganisms, transforming the association collapse under extreme stress into an orderly synergy, verifying its ecological remediation potential.

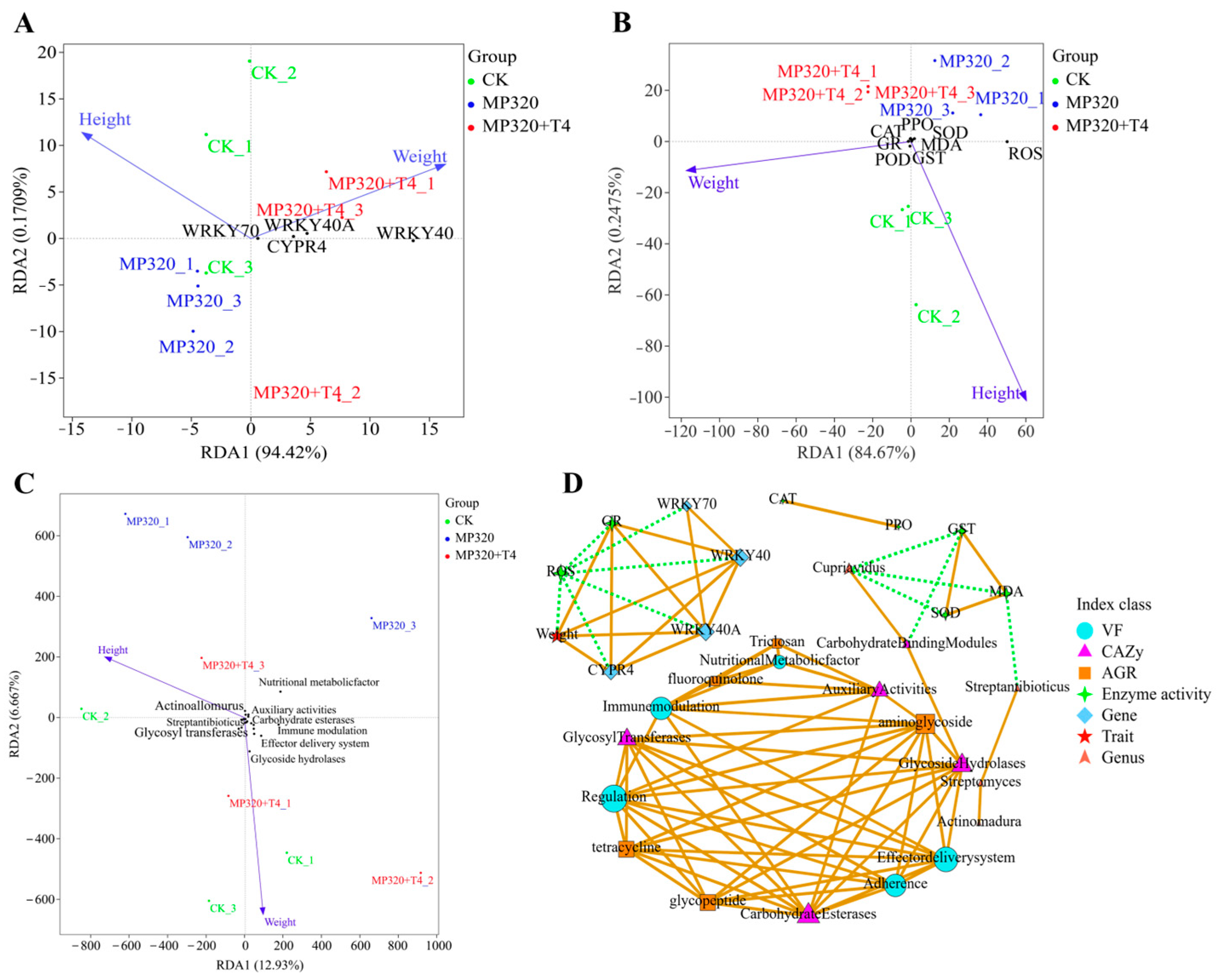

Redundancy analysis (RDA) showed significant distribution differences in multidimensional indicators such as genes, enzyme activity, microorganisms, and functional pathways among different treatment groups. Redundancy analysis (RDA) of low-concentration aged microplastics (MP80) related treatments showed that RDA1 accounted for 87.94% of the variance (

Figure 19D). In terms of sample distribution, the CK group distribution reflects the synergistic growth and stress resistance indicators of the blank group. The MP80 group is distributed on the right side, reflecting the synergistic shift of growth oxidative damage induced by aged microplastic stress. The MP80+T4 group is located between the CK and MP80, close to the enzyme activity and membrane damage indicators, indicating that

T. harzianum T4 regulates the antioxidant membrane damage pathway, reshapes growth and stress resistance indicators, alleviates aged microplastic stress, and height is positively correlated with the MP80 group samples, and weight is positively correlated with the MP80+T4 group samples. Enzyme activity and membrane damage are closely related to the CK and MP80+T4 group samples, verifying the alleviating effect of

Trichoderma (

Figure 19D). In the high-concentration aged microplastics treatment, the RDA1 of genes and growth indicators is 94.42% (

Figure 20A). The MP320 group is separated from the CK group, while the MP320+T4 group deviates from the MP320 group and approaches the CK group. Height is biased towards the CK, and weight is strongly correlated with the MP320+T4. The distribution of samples driven by genes such as WRKY70/40A indicates that

T. harzianum T4 can improve biomass by regulating the gene network (

Figure 20A). The RDA1 of enzyme activity and stress resistance indicators is 84.67%. Samples were separated from oxidative stress indicators (MDA, ROS) and antioxidant system-related enzymes (SOD, POD, etc.), and the weight response was between the CK and MP320+T4, revealing that

T. harzianum T4 has the function of synergistically regulating the growth and stress resistance physiological network of

N. benthamiana (

Figure 20B). The RDA1 of microbiota and functional pathways and growth indicators is 12.93%, indicating that the microbial community (such as

Actinoallomurus) and functional genes (ARGs, CAZys) in the MP320 group are distributed discretely (

Figure 20C). The MP320+T4 group approaches the CK by enriching beneficial microbial communities and activating carbon metabolism pathways (such as CAZys), alleviating the stress effect. Through network correlation analysis of agronomic traits, genes, enzyme activity, dominant bacteria, and functional pathways, under the treatment of

T. harzianum T4, WRKY transcription factor (

WRKY40/

70) directly clears oxidative damage (ROS) by activating antioxidant enzymes (GR, GST) and optimizes nutrient utilization through enrichment of functional microorganisms such as Cupriavidus and Streptomyces, in conjunction with the carbohydrate metabolism pathway (CAZy), and feedback promotes plant growth (

Figure 20D). Ultimately, a “gene enzyme microorganism” collaborative network will be constructed to reshape the plant microorganism interaction balance under microplastic stress.