Active Fraction of Tillandsia usneoides Induces Structural Neuroplasticity in Cortical Neuron Cultures from Wistar Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

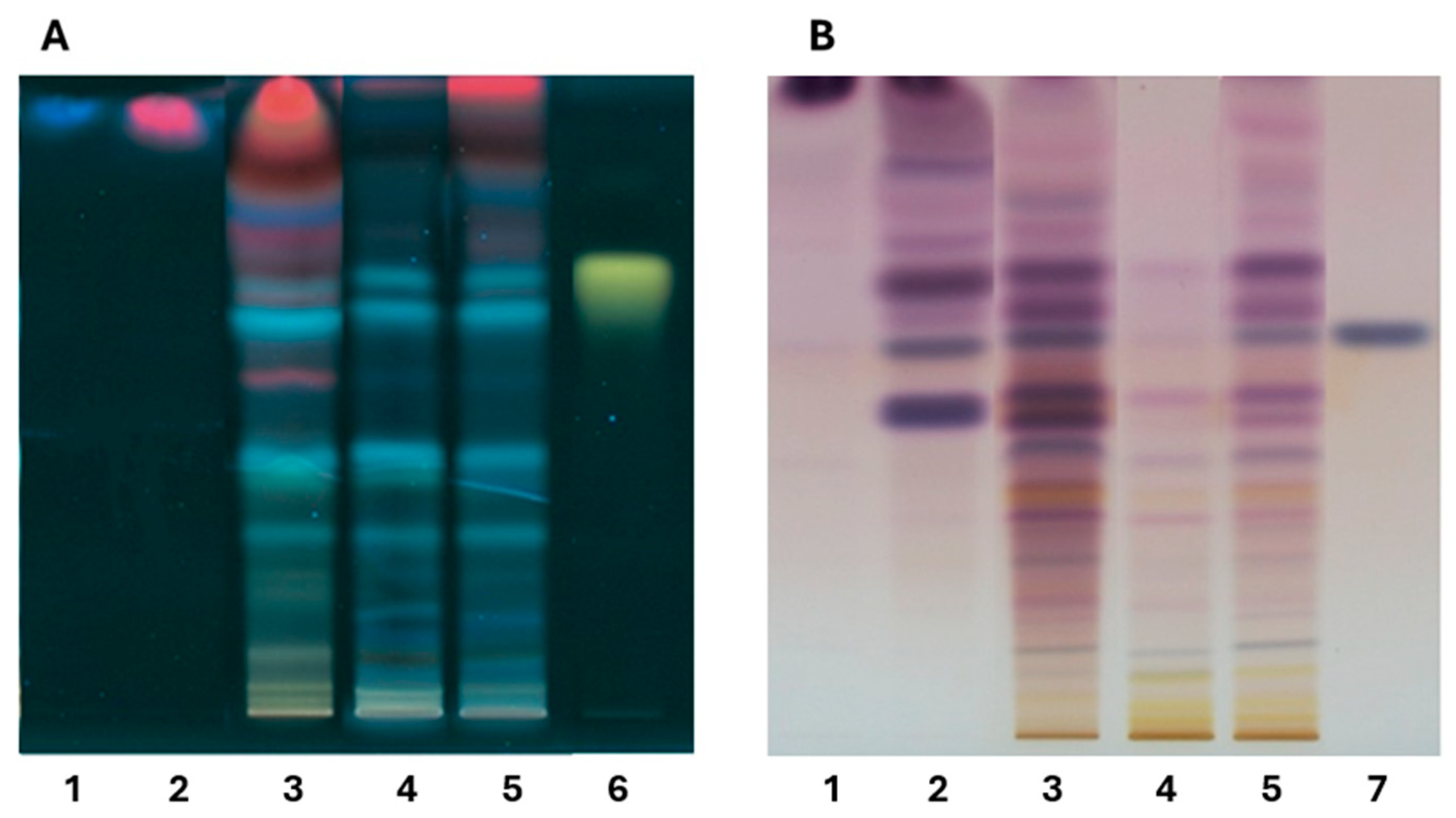

2.1. Qualitative Analysis of Tillandsia Usneoides by High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)

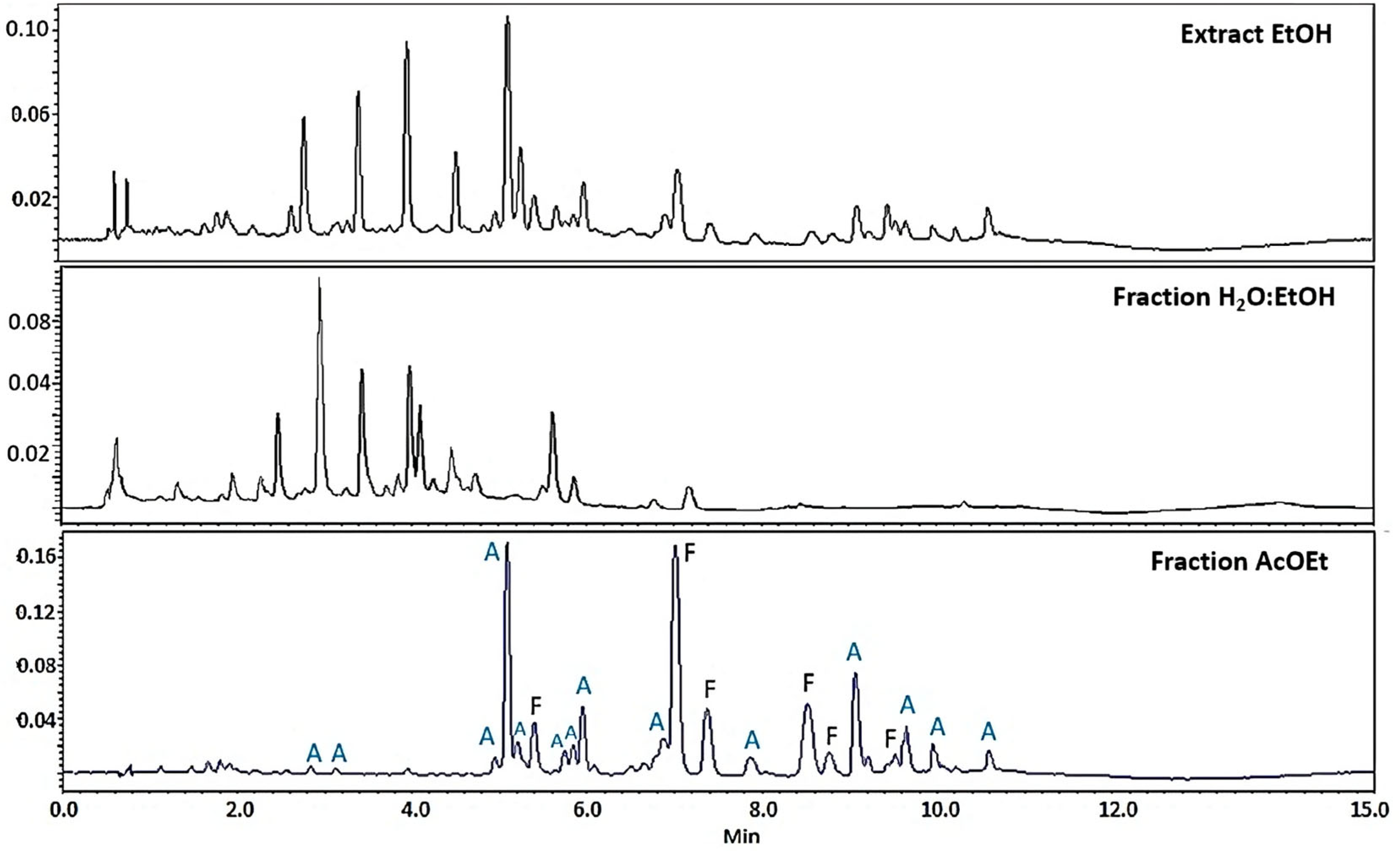

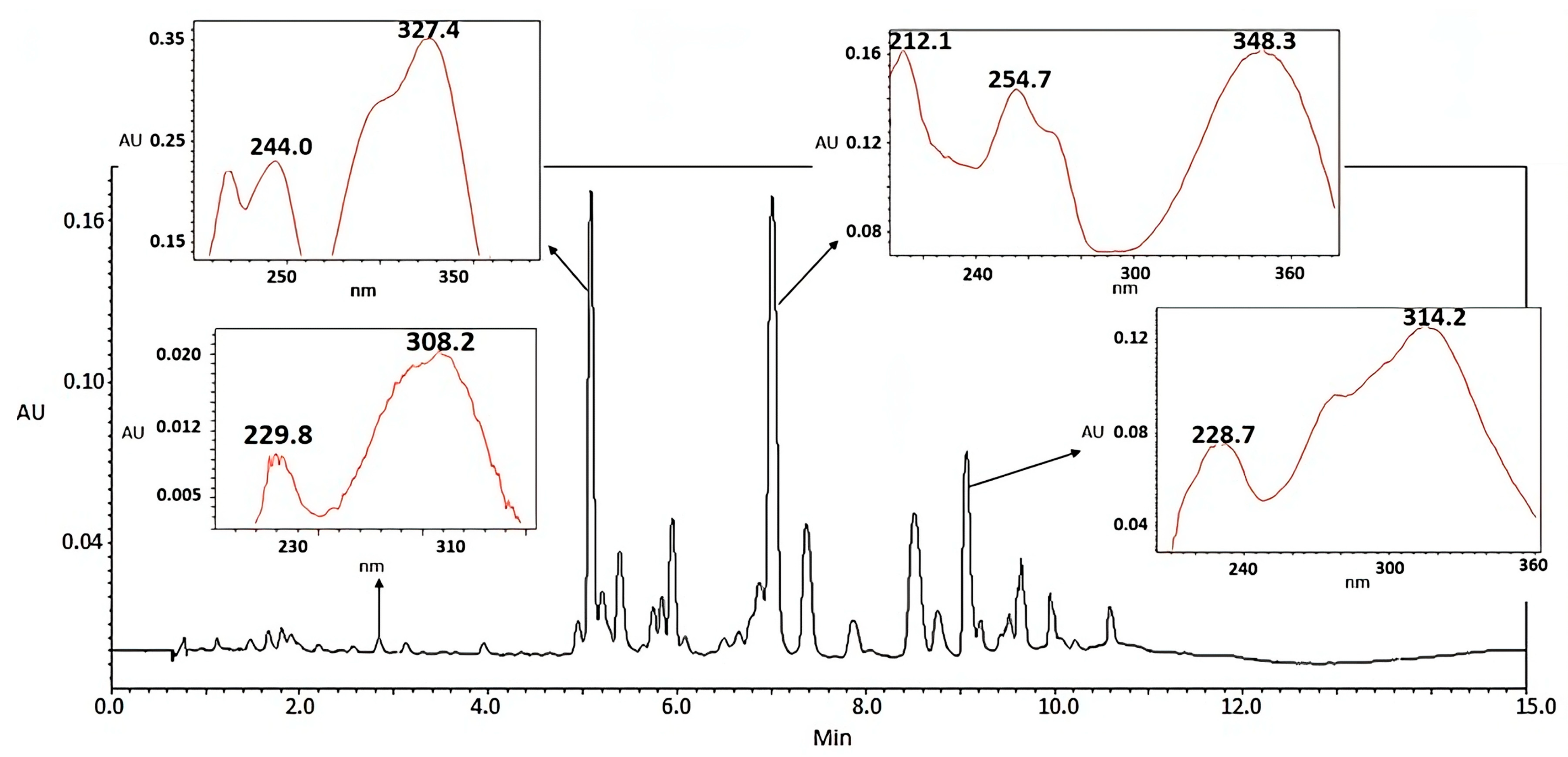

Composition Profile of Tillandsia usneoides by Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to a Diode Array Detector (UPLC-DAD)

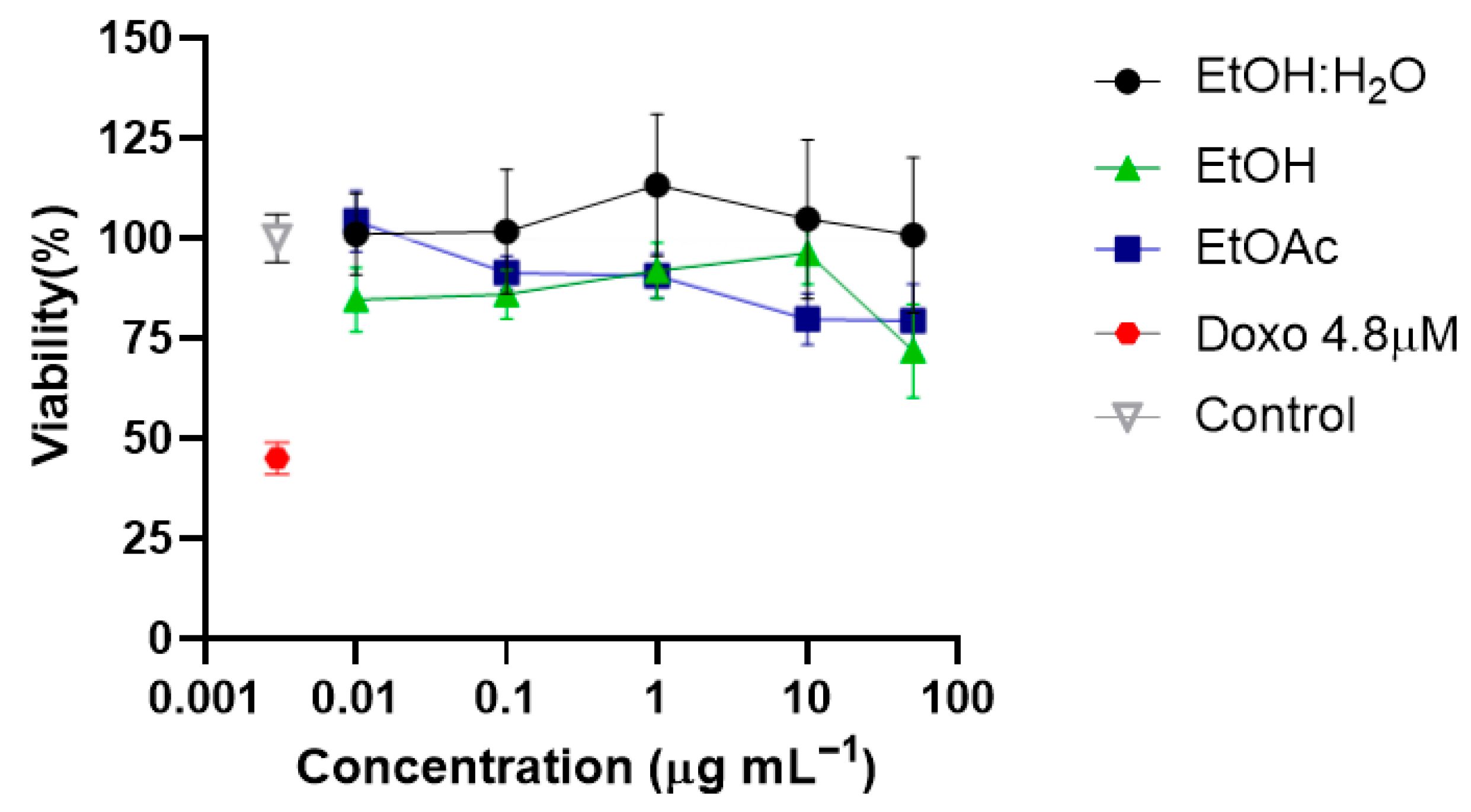

2.2. Tillandsia Usneoides Extract, H2O:EtOH and EtOAc Fractions Did Not Affect the Cell Viability of Neurons In Vitro

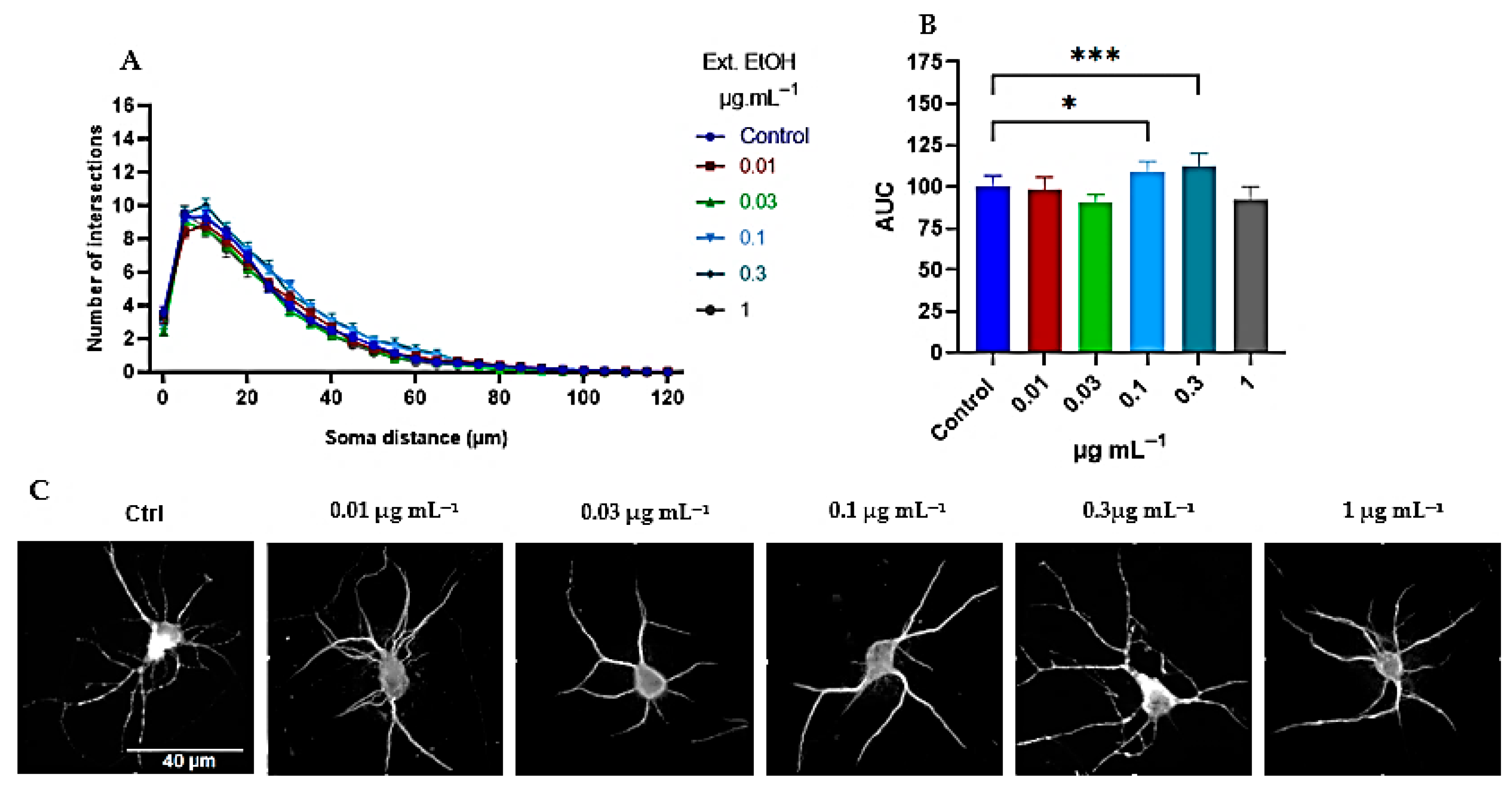

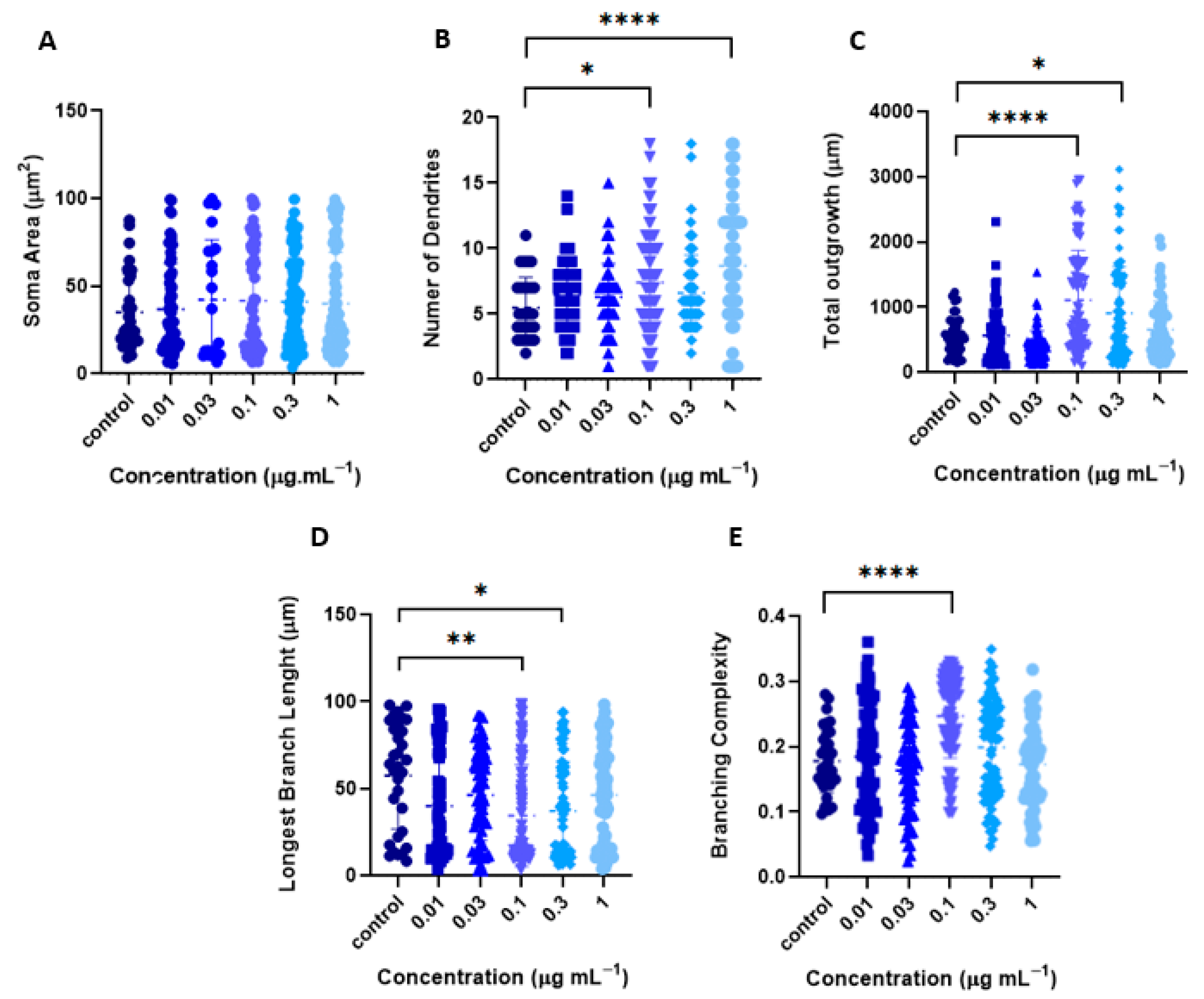

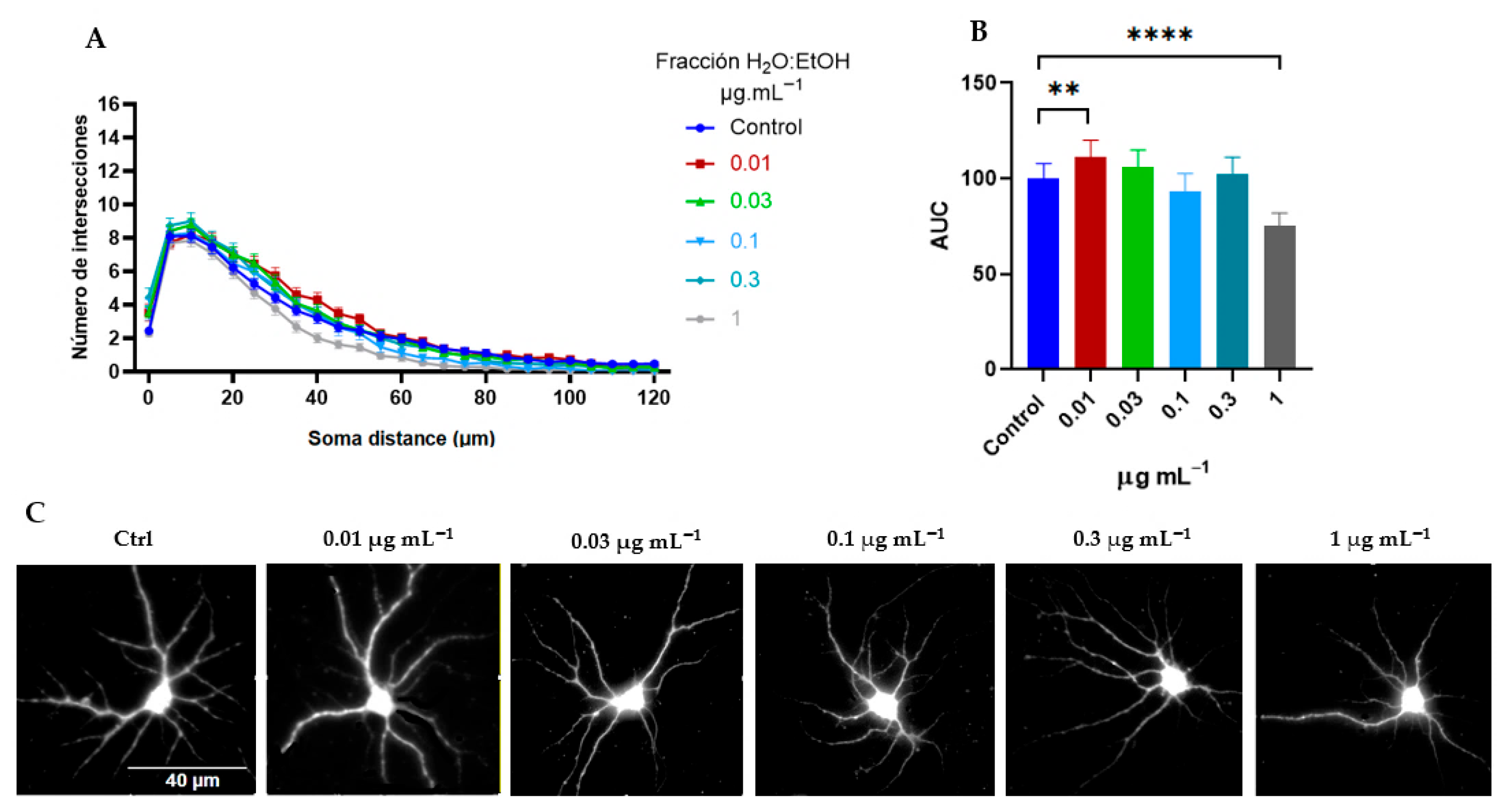

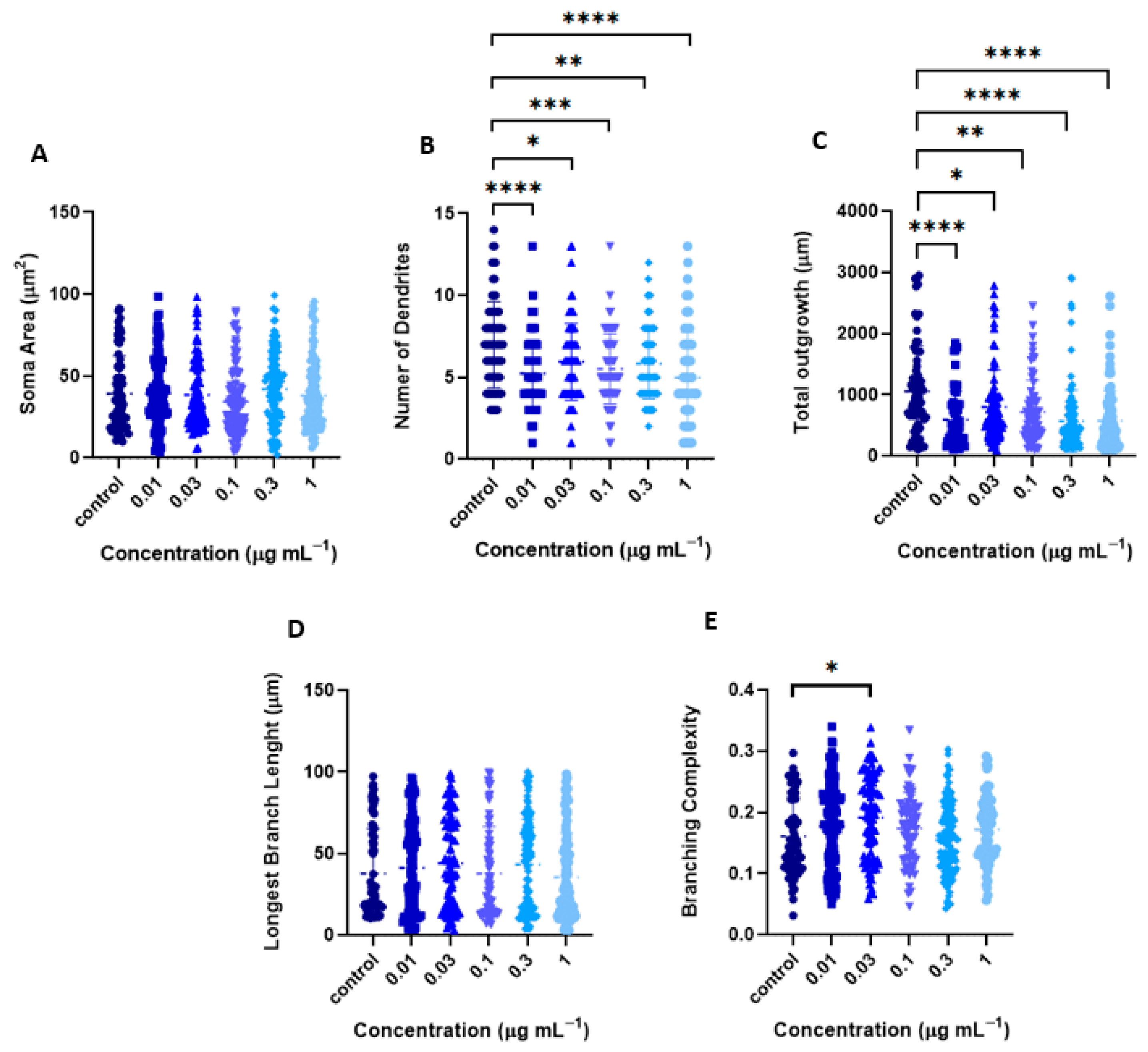

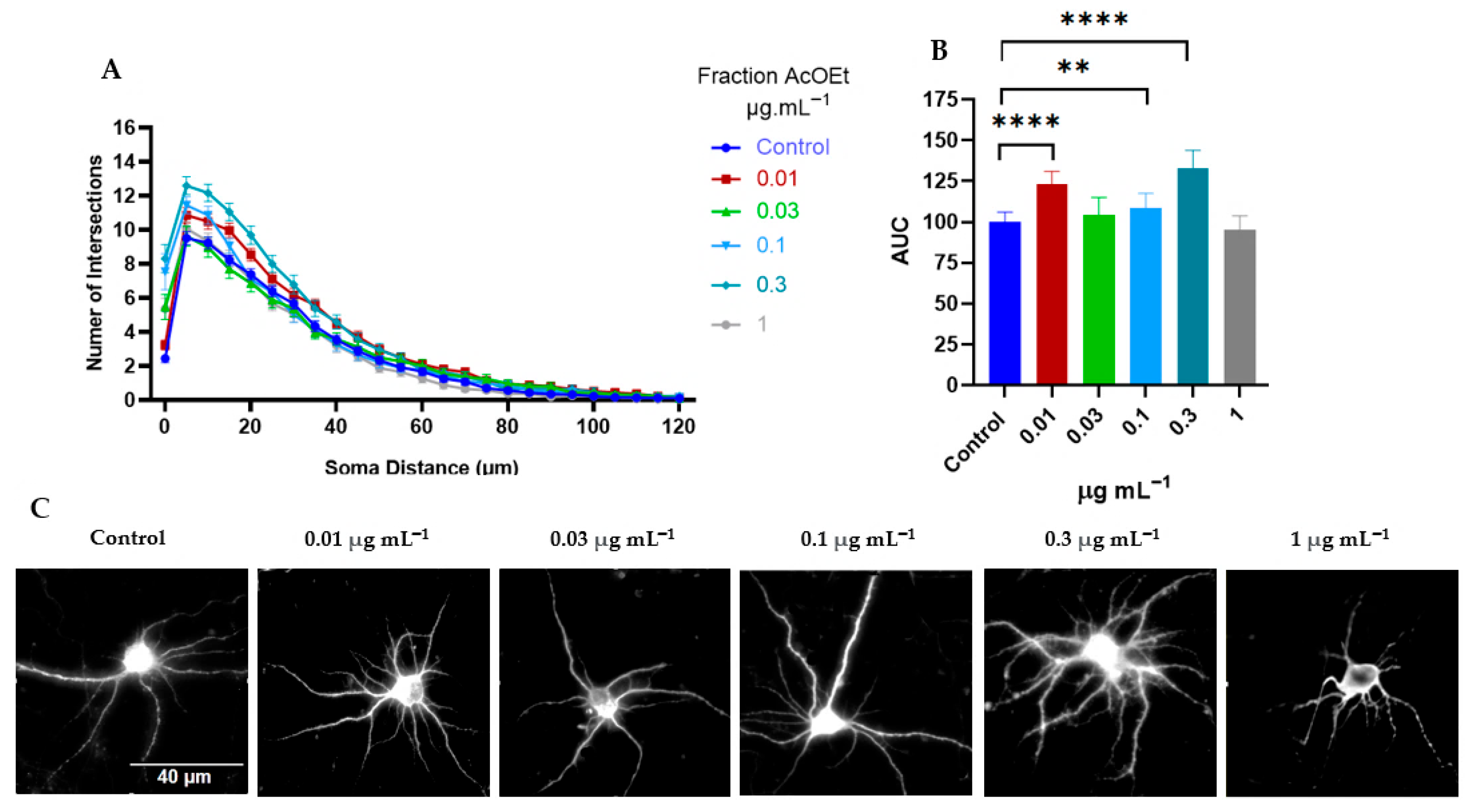

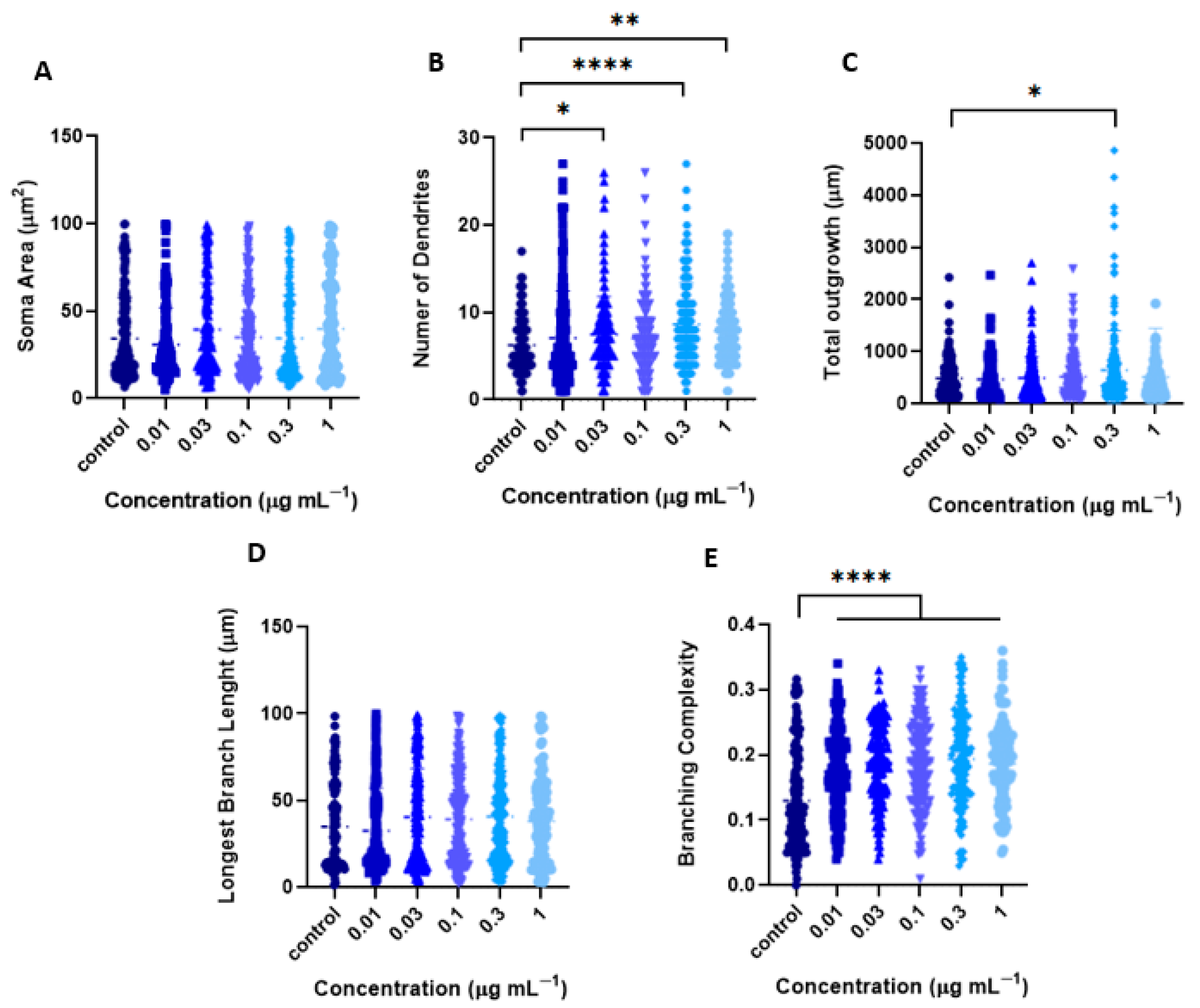

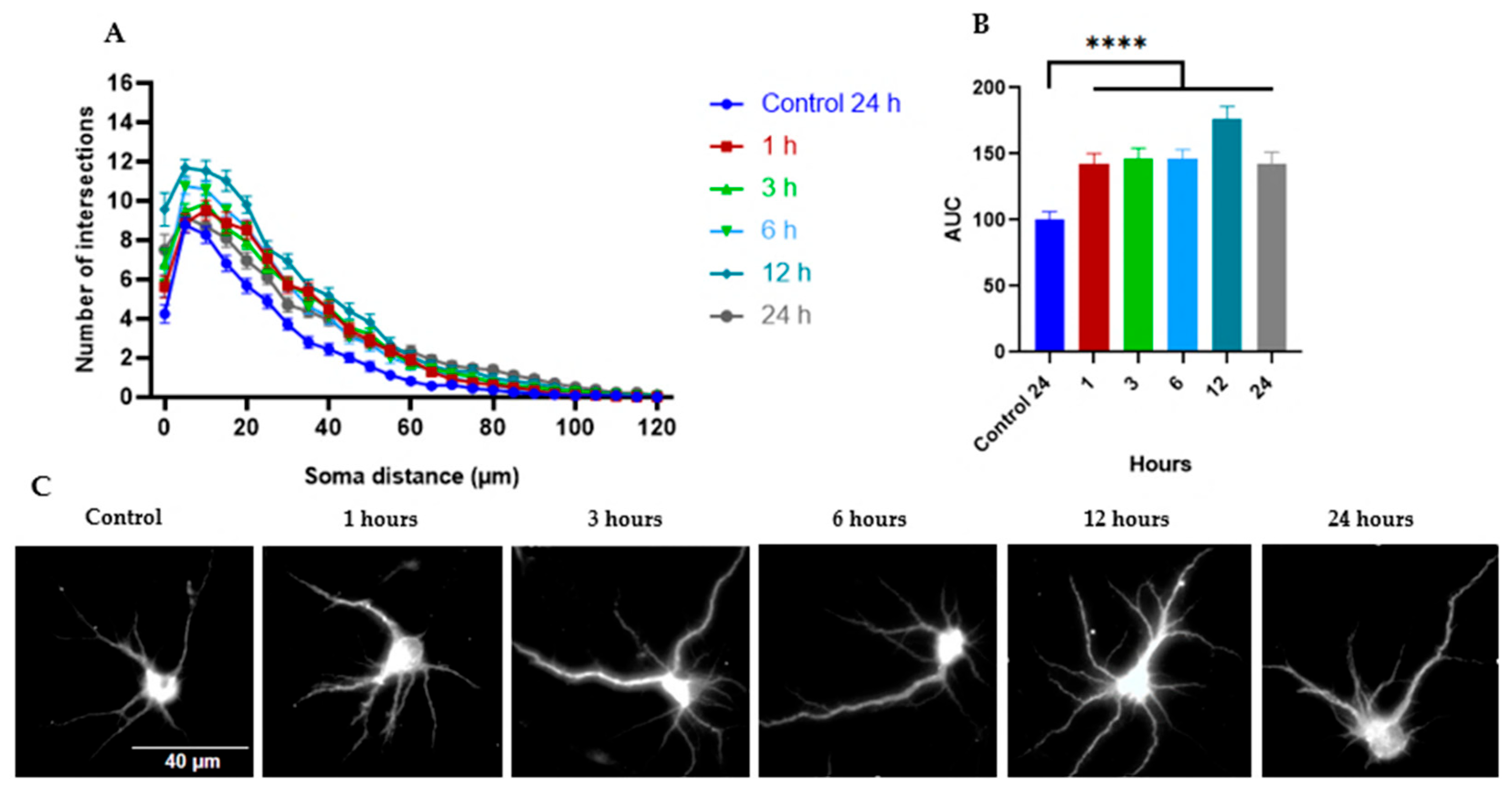

2.2.1. Tillandsia Usneoides Increases the Dendritic Complexity of Cortical Neurons

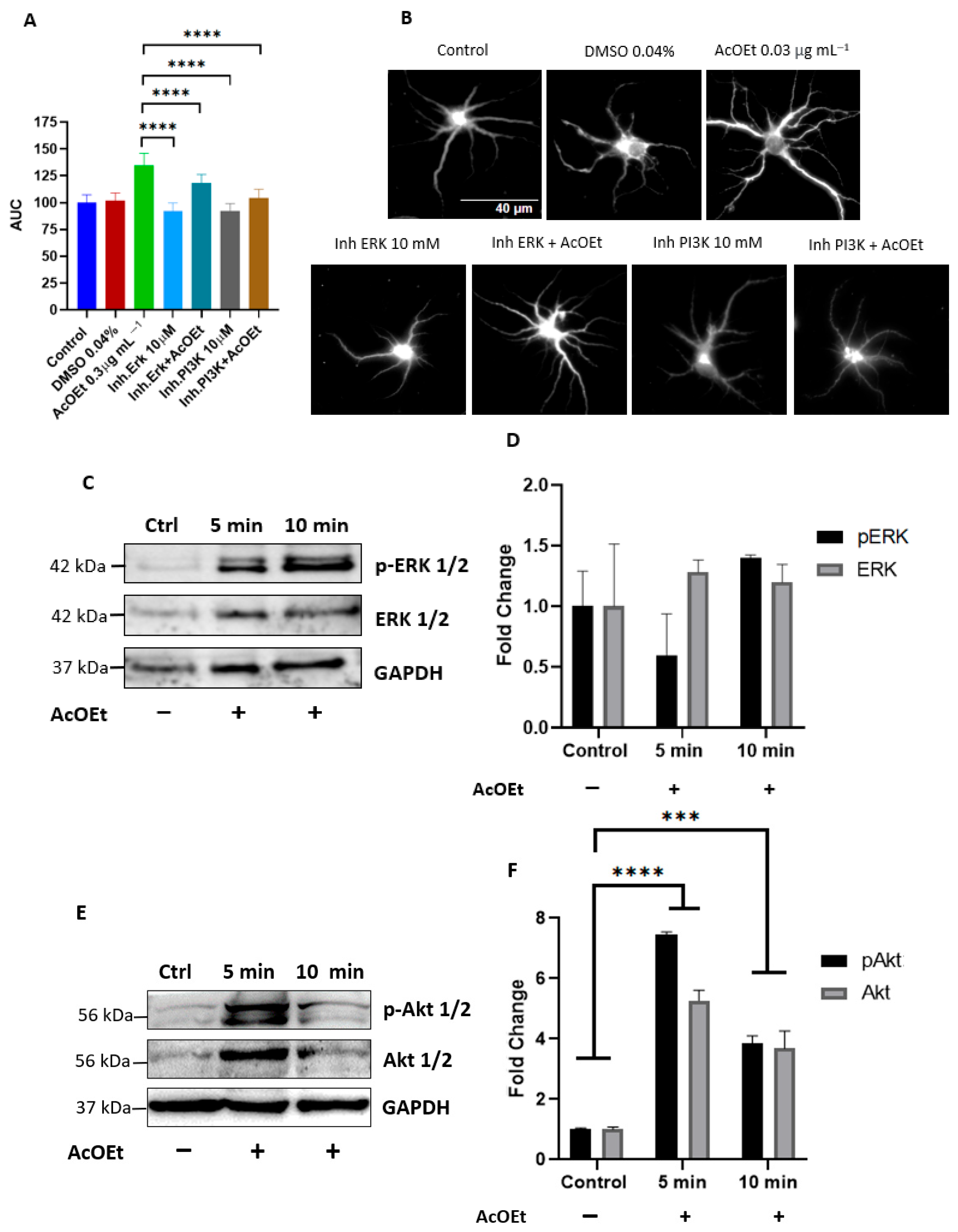

2.2.2. T. usneoides Activates the ERK and PI3K Signaling Pathways Involved in the Induction of Dendritogenesis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

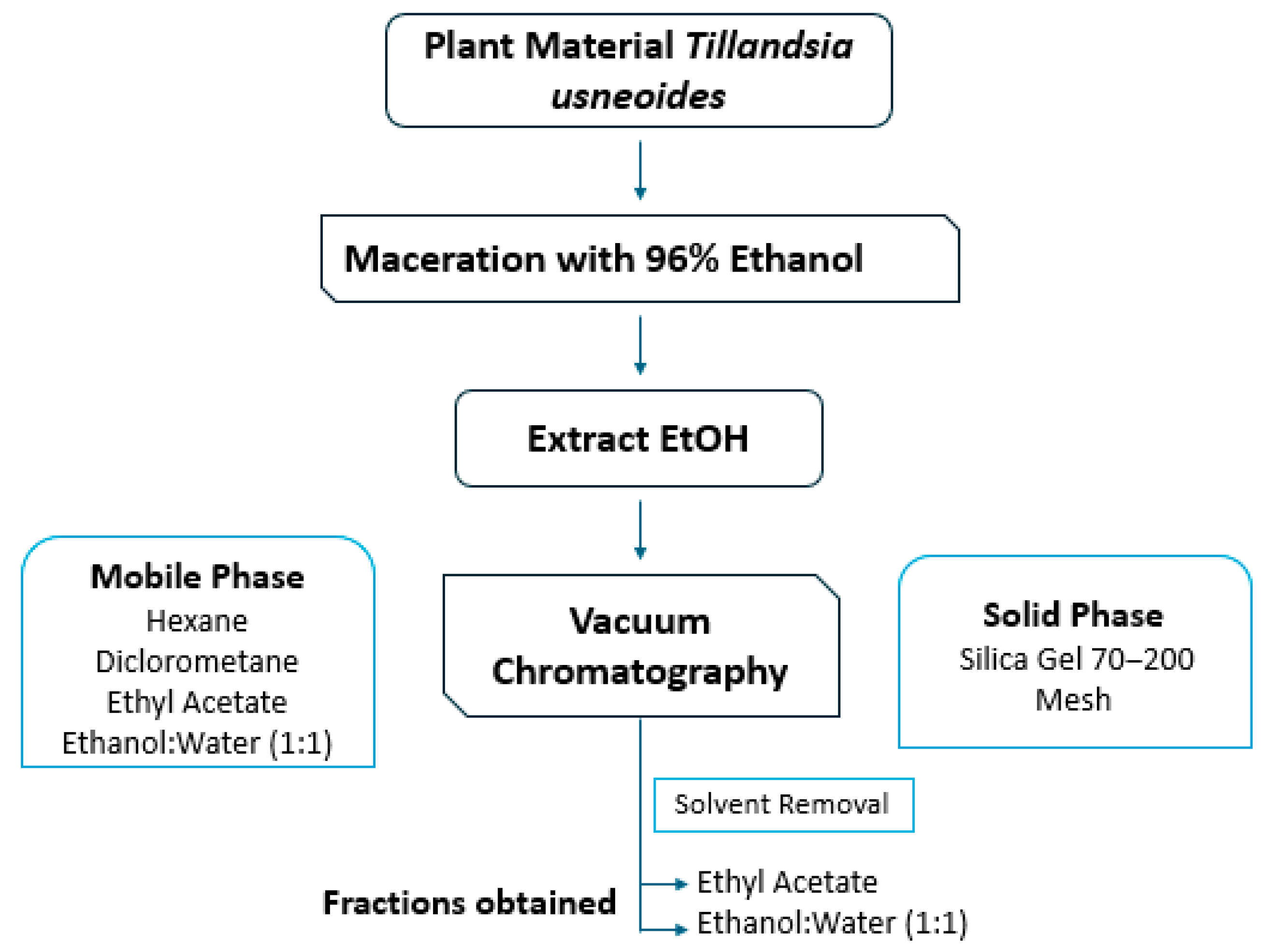

4.1. Obtaining the Extract and Active Fraction

4.2. Qualitative Chemical Characterization

4.2.1. High Performance Thin Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)

4.2.2. Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to a Diode Array Detector (UPLC-DAD)

4.3. Animals and Primary Neuron Culture

4.4. Cell Viability

4.5. Evaluation of Dendritogenesis-Inducing Potential

Image Acquisition and Processing

4.6. Determination of ERK and PI3K Pathway Activation by Western Blot Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martin, R.E. Neuroplasticity and Swallowing. Dysphagia 2009, 24, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés, M.V.; Suárez, N.C. Neuroplasticidad: Aspectos bioquímicos y neurofisiológicos. CES Med. 2014, 28, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M.V. Plasticity in the developing brain: Implications for rehabilitation. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2009, 15, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, F.C.; Cohen, L.G. Drivers of brain plasticity. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2005, 18, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, B.O.; Batzu, L.; Ruiz, P.J.G.; Tulbă, D.; Moro, E.; Santens, P. Neuroplasticity in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 2024, 131, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyaeva, N.V. Molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity: An expanding universe. Biochemistry 2017, 82, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, A.; Patni, P.; Hegde, S.; Aleya, L.; Tewari, D. Neuroplasticity and environment: A pharmacotherapeutic approach towards preclinical and clinical understanding. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2020, 19, 100210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichon, N.; Saluk-Bijak, J.; Gorniak, L.; Przyslo, L.; Bijak, M. Flavonoids as a natural enhancer of neuroplasticity-an overview of the mechanism of neurorestorative action. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platholi, J.; Lee, F.S. Neurotrophic Factors. In Handbook of Developmental Neurotoxicology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citri, A.; Malenka, R.C. Synaptic plasticity: Multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 33, 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, J.; Spangler, S.; Seeburg, D.P.; Hoogenraad, C.C.; Sheng, M. Control of dendritic arborization by the phosphoinositide-3′-kinase- Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 11300–11312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, A.; Levitz, J. Glutamatergic Signaling in the Central Nervous System: Ionotropic and Metabotropic Receptors in Concert. Neuron 2018, 98, 1080–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.M.H.; Haque, M.N.; Mohibbullah, M.; Kim, Y.K.; Moon, I.S. Radix Puerariae modulates glutamatergic synaptic architecture and potentiates functional synaptic plasticity in primary hippocampal neurons. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 209, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongnok, B.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Doxorubicin and cisplatin induced cognitive impairment: The possible mechanisms and interventions. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 324, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingayya, G.V.; Cheruku, S.P.; Nayak, P.; Kishore, A.; Shenoy, R.; Rao, C.M.; Krishnadas, N. Rutin protects against neuronal damage in vitro and ameliorates doxorubicin-induced memory deficits in vivo in Wistar rats. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2017, 11, 1011–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.M.H.; Mohibbullah, M.; Hannan, M.A.; Hong, Y.K.; Choi, J.S.; Choi, I.S.; Moon, I.S. Undaria pinnatifida promotes spinogenesis and synaptogenesis and potentiates functional presynaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2015, 43, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.H.; Jung, J.Y.; Lee, B.J.; Lee, K.; Park, J.W.; Bu, Y. Epimedii Herba: A Promising Herbal Medicine for Neuroplasticity. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ip, P.S.P.; Tsim, K.W.K.; Chan, K.; Bauer, R. Application of complementary and alternative medicine on neurodegenerative disorders: Current status and future prospects. J. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 930908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingayya, G.V.; Nampoothiri, M.; Nayak, P.G.; Kishore, A.; Shenoy, R.R.; Rao, C.M.; Nandakumar, K. Naringin and rutin alleviates episodic memory deficits in two differentially challenged object recognition tasks. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2016, 12, S63–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S.; Munni, Y.A.; Dash, R.; Sultana, A.; Moon, I.S. Unveiling the effect of Withania somnifera on neuronal cytoarchitecture and synaptogenesis: A combined in vitro and network pharmacology approach. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 2524–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Cai, J. The in vivo synaptic plasticity mechanism of EGb 761-induced enhancement of spatial learning and memory in aged rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 148, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Rice-Evans, C. Flavonoids: Antioxidants or signalling molecules? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, F.H.; El-Derany, M.O.; Wahdan, S.A.; El-Demerdash, E.; El-Mesallamy, H.O. Berberine ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cognitive impairment (chemobrain) in rats. Life Sci. 2021, 269, 119078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannock, I.F.; Ahles, T.A.; Ganz, P.A.; van Dam, F.S. Cognitive impairment associated with chemotherapy for cancer: Report of a workshop. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2233–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papini, A.; Tani, G.; Di Falco, P.; Brighigna, L. The ultrastructure of the development of Tillandsia (Bromeliaceae) trichome. Flora—Morphology, Distribution. Funct. Ecol. Plants. 2010, 205, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella, E.; Flores, M.; Blancas, G.; Koch, S.; Alarcón, F. The Tillandsia genus: History, uses, chemistry, and biological activity. J. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromát. 2019, 18, 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- Garth, R.E. The Ecology of Spanish Moss (Tillandsia Usneoides): Its Growth and Distribution. Ecology 1964, 45, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, W. Guía Ilustrada De Las Plantas de Las Montañas Del Quindio Y Los Andes Centrales; Universidad de Caldas, Centro Editorial: Manizales, Colombia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, A.G. Flora Útil: Etnobotánica de Nicaragua; Gobierno de Nicaragua, MARENA: Managua, Nicaragua, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, G.M.; Gallo, M.; Seldes, A.M. A 3,4-seco-cycloartane derivative from Tillandsia usneoides. Phytochemistry 1995, 39, 665–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, G.M.; Seldes, A.M. Short side-chain cycloartanes from Tillandsia usneoides. Phytochemistry 1997, 45, 1019–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A. Evaluación Del Efecto Neuroprotector Y de Los Cambios en La Complejidad Dendrítica Inducidos Por Los Extractos de Tillandsia usneoides Y Lippia alba en Cultivo Primario de Neuronas Tratadas Con Agentes Quimioterapéuticos. Tesis de Maestría, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia, 2021. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10554/6359 (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Lewis, D.; Mabry, T.J. 3,6,3′,5′-tetrametroxy-5,7,4′-trihydroxyflavone from Tillandsia usneoides. Phytochemistry 1977, 16, 1114–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenweber, E.; Mann, K.; Roitman, J.N. A Myricetin Tetramethyl Ether from the Leaf and Stem Surfaces of Tillandsia usneoides. Z. Für Naturforsch. 1992, 47, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Bladt, S. A Thin Layer Chromatography Atlas, 2nd ed.; Springer: Munchen, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rishal, I.; Golani, O.; Rajman, M.; Costa, B.; Ben-Yaakov, K.; Schoenmann, Z.; Yaron, A.; Basri, R.; Fainzilber, M.; Galun, M. WIS-neuromath enables versatile high throughput analyses of neuronal processes. Dev. Neurobiol. 2012, 73, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkon, D.L.; Sun, M.K.; Nelson, T.J. signaling deficits: A mechanistic hypothesis for the origins of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 28, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Qiu, C.S.; Liauw, J.; Robinson, D.A.; Ho, N.; Chatila, T.; Zhuo, M. Calcium calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IV is required for fear memory. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, P.S.; Aguayo, F.; Neira, D.; Tejos, M.; Aliaga, E.; Muñoz, J.P.; Parra, C.S.; Fiedler, J.L. Dual effect of serotonin on the dendritic growth of cultured hippocampal neurons: Involvement of 5-HT1A and 5-HT7 receptors. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2017, 85, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, J.P.; Vauzour, D.; Rendeiro, C. Flavonoids and cognition: The molecular mechanisms underlying their behavioural effects. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2009, 492, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velásquez, M.M.; Lattig, M.C.; Chitiva, L.C.; Costa, G.M.; Sutachan, J.J.; Albarracin, S.L. Dendritogenic Potential of the Ethanol Extract from Lippia alba Leaves in Rat Cortical Neurons. Molecules 2023, 28, 6666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, A.L.; Vasconcelos, A.L.; Ximenez, E.A.; Randau, K.P. Tillandsia recurvata L. (Bromeliaceae): Aspectos farmacognósticos. Rev. Ciênc Farm. Básica Apl. 2013, 34, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Djerassi, C.; McCrindle, R. Terpenoids Part LI The isolation of some new cyclopropanecontaining triterpenes from Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides L). J. Chem. Soc. 1962, 4034–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L.B.; Leal-Costa, M.B.; Menezes, E.; Rodrigues, V.; Muzitano, M.; Costa, S.; Schwartz, E. Ultraviolet-B radiation effects on phenolic profile and flavonoid content of Kalanchoe pinnata. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2015, 148, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewick, P.M. Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Sussex, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Minsat, L.; Peyrot, C.; Brunissen, F.; Renault, J.H.; Allais, F. Synthesis of Biobased Phloretin Analogues: An Access to Antioxidant and Anti-Tyrosinase Compounds for Cosmetic Applications. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbo, H.S.; Hung, L.C.; Titinchi, S.J.J. Substituent and solvent effects on UV-visible absorption spectra of chalcones derivatives: Experimental and computational studies. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 15, 123180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski, R.; Kowalska, G. PHENOLIC ACID CONTENTS IN FRUITS OF AUBERGINE (Solanum melongena L.). Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2005, 55, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M.; Comin, J.; Moresco, R.; Maraschin, M.; Kurtz, C.; Lovato, E.P.; Lourenzi, R.C.; Pilatti, K.F.; Loss, A.; Kuhnen, S. Exploratory and discriminant analysis of plant phenolic profiles obtained by UV-vis scanning spectroscopy. J. Integr. Bioinform. 2021, 4, 18, 20190056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeswurm, J.A.H.; Scharinger, A.; Teipel, J.; Buchweitz, M. Absorption Coefficients of Phenolic Structures in Different Solvents Routinely Used for Experiments. Molecules 2021, 31, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semwal, P.; Kapoor, T.; Anthwal, P.; Sati, B.K.; Thapliyal, A. Herbal Extract as Potential Modulator and Drug for Synaptic Plasticity and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. 2014, 25, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rendeiro, C.; Rhodes, J.S.; Spencer, J.P. The mechanisms of action of flavonoids in the brain: Direct versus indirect effects. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, E.; Müller, M.; Hornberger, M.; Vauzour, D. Impact of Flavonoids on Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Age-Related Cognitive Decline and Neurodegeneration. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2018, 7, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanska, M.; Blazejczyk, M.; Jaworski, J. Molecular basis of dendritic arborization. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2008, 68, 264–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, M.A.; Kang, J.Y.; Hong, Y.K.; Lee, H.S.; Chowdhury, M.T.H.; Choi, J.S.; Choi, I.S.; Moon, I.S. A brown alga Sargassum fulvellum facilitates neuronal maturation and synaptogenesis. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2012, 48, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Mohibbullah, M.; Hong, Y.K.; Nam, J.H.; Moon, I.S. Gelidium amansii promotes dendritic spine morphology and synaptogenesis, and modulates NMDA receptor-mediated postsynaptic current. Vitr. Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2014, 50, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.X.; Gao, A.X.; Dong, T.T.; Tsim, K.W. Flavonoids from Seabuckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) mimic neurotrophic functions in inducing neurite outgrowth in cultured neurons: Signaling via PI3K/Akt and ERK pathways. Phytomedicine 2023, 115, 154832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.A. The systematic implications of the complexity of leaf flavonoids in the bromeliaceae. Phytochemistry 1978, 17, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, L.M.; Delaporte, R.H.; Laverde, A., Jr. Metabólitos Secundários da Família Bromeliaceae. Quim. Nova. 2009, 32, 1885–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, A.; Singh, D. Dietary Flavonoids Interaction with CREB-BDNF Pathway: An Unconventional Approach for Comprehensive Management of Epilepsy. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 1158–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numakawa, T.; Richards, M.; Nakajima, S.; Adachi, N.; Furuta, M.; Odaka, H.; Kunugi, H. The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in comorbid depression: Possible linkage with steroid hormones, cytokines, and nutrition. Front. Psychiatry 2014, 5, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, X.; Chen, J.; Dai, S.; Wang, J.; Huang, Z.; Lv, Z.; Qian, W.; Wu, Q. Cyanidin-related Antidepressant-like Efficacy Requires PI3K/AKT/FoxG1/FGF-2 Pathway Modulated Enhancement of Neuronal Differentiation and Dendritic Maturation. Phytomedicin 2020, 76, 153269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeter, H.; Bahia, P.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Sheppard, O.; Rattray, M.; Rice-Evans, C.; Williams, R.J. (–)-epicatechin stimulates ERK-dependent cyclic AMP response element activity and upregulates GLUR2 in cortical neurons. J. Neurochem. 2007, 101, 1596–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Tian, M.; Zhao, H.Y.; Xu, Q.Q.; Huang, Y.M.; Si, Q.C.; Tian, Q.; Wu, Q.M.; Hu, X.M.; Sun, L.B.; et al. TrkB activation by 7, 8-dihydroxyflavone increases synapse AMPA subunits and ameliorates spatial memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2016, 136, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.L.; Ma, H.; Man, Y.G.; Lv, H.Y. Protective effects of a green tea polyphenol, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, against sevoflurane-induced neuronal apoptosis involve regulation of CREB/BDNF/TrkB and PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling pathways in neonatal mice. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2017, 95, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.P. The interactions of flavonoids within neuronal signalling pathways. Genes Nutr. 2007, 2, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessi, D.R.; Cuenda, A.; Cohen, P.; Dudley, D.T.; Saltiel, A.R. PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 27489–27494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeter, H.; Boyd, C.; Spencer, J.P.; Williams, R.J.; Cadenas, E.; Rice-Evans, C. MAPK signaling in neurodegeneration: Influences of flavonoids and of nitric oxide. Neurobiol. Aging 2002, 5, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeter, H.; Spencer, J.P.; Rice-Evans, C.; Williams, R.J. Flavonoids protect neurons from oxidized low-density-lipoprotein-induced apoptosis involving c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), c-Jun and caspase-3. Biochem. J. 2001, 358, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.; Redmond, L. ERK mediates activity dependent neuronal complexity via sustained activity and CREB-mediated signaling. Dev. Neurobiol. 2008, 14, 1565–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, M.C.; Er, E.E.; Blenis, J. The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR pathways: Cross-talk and compensation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 6, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brivio, P.; Sbrini, G.; Corsini, G.; Paladini, M.S.; Racagni, G.; Molteni, R.; Calabrese, F. Chronic Restraint Stress Inhibits the Response to a Second Hit in Adult Male Rats: A Role for BDNF Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.M.; Huganir, R.L. MAPK cascade signalling and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.P.; Schroeter, H.; Crossthwaithe, A.J.; Kuhnle, G.; Williams, R.J.; Rice-Evans, C. Contrasting influences of glucuronidation and O -methylation of epicatechin on hydrogen peroxide-induced cell death in neurons and fibroblasts. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 31, 1139–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.P.; Abd-el-Mohsen, M.M.; Rice-Evans, C. Cellular uptake and metabolism of flavonoids and their metabolites: Implications for their bioactivity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 423, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGiosio, R.A.; Grubisha, M.J.; MacDonald, M.L.; McKinney, B.C.; Camacho, C.J.; Sweet, R.A. More than a marker: Potential pathogenic functions of MAP2. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 974890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binley, K.E.; Ng, W.S.; Tribble, J.R.; Song, B.; Morgan, J.E. Sholl analysis: A quantitative comparison of semi-automated methods. J. Neurosci. Methods 2014, 225, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villarreal Romero, W.L.; Sutachan, J.J.; Costa, G.M.; Albarracín, S.L. Active Fraction of Tillandsia usneoides Induces Structural Neuroplasticity in Cortical Neuron Cultures from Wistar Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311668

Villarreal Romero WL, Sutachan JJ, Costa GM, Albarracín SL. Active Fraction of Tillandsia usneoides Induces Structural Neuroplasticity in Cortical Neuron Cultures from Wistar Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311668

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillarreal Romero, Wilson Leonardo, Jhon J. Sutachan, Geison Modesti Costa, and Sonia Luz Albarracín. 2025. "Active Fraction of Tillandsia usneoides Induces Structural Neuroplasticity in Cortical Neuron Cultures from Wistar Rats" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311668

APA StyleVillarreal Romero, W. L., Sutachan, J. J., Costa, G. M., & Albarracín, S. L. (2025). Active Fraction of Tillandsia usneoides Induces Structural Neuroplasticity in Cortical Neuron Cultures from Wistar Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11668. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311668