Current Research on the Control Mechanisms of Cell Survival and Proliferation as Potential Interaction Sites with Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in Ovarian Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

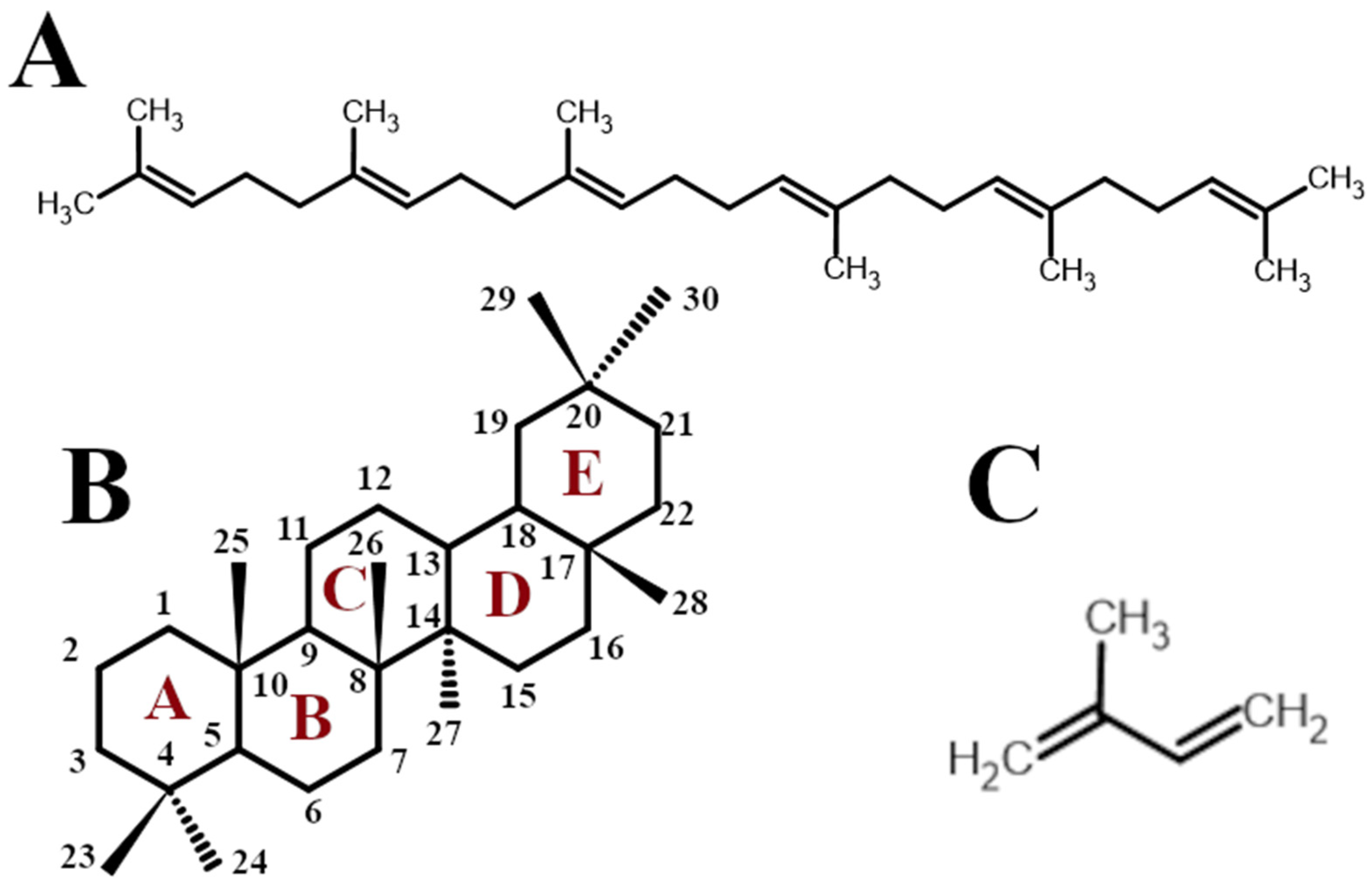

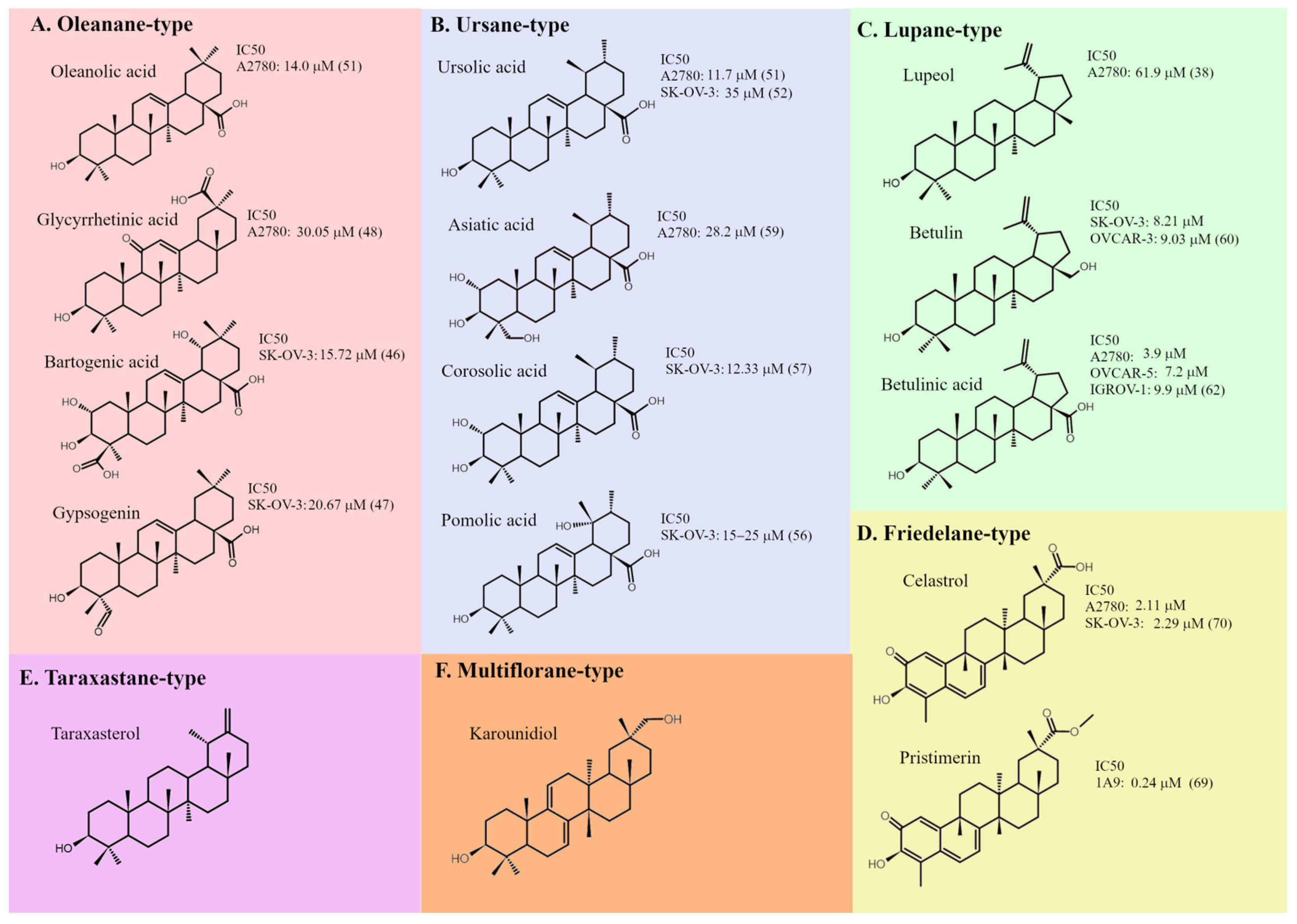

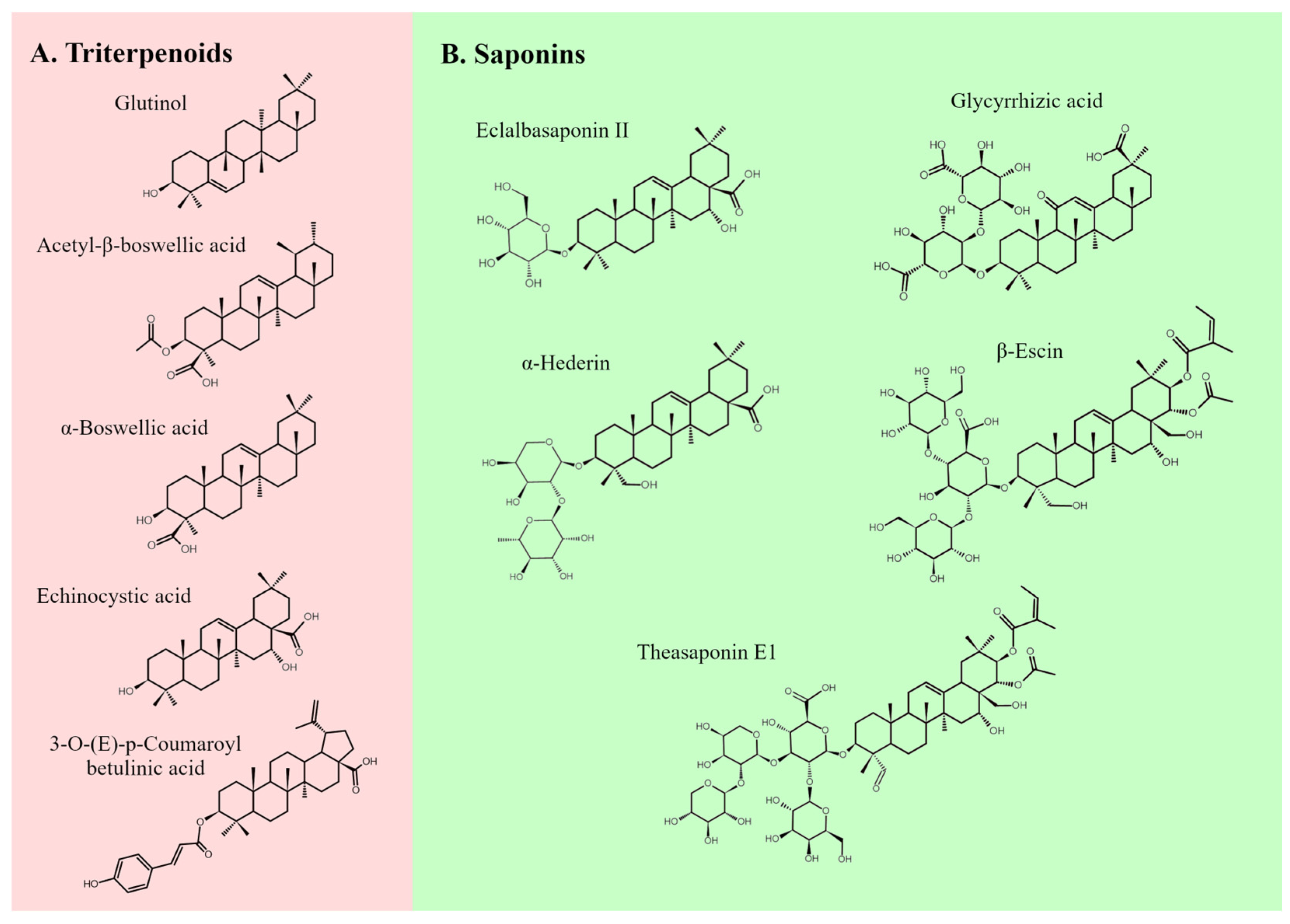

2. Pentacyclic Triterpenoids as Anti-Cancer Compounds

3. Main Types of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids and Their Effects on Ovarian Cancer Cells

4. Molecular Mechanisms of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids’ Action on Ovarian Cancer Cells

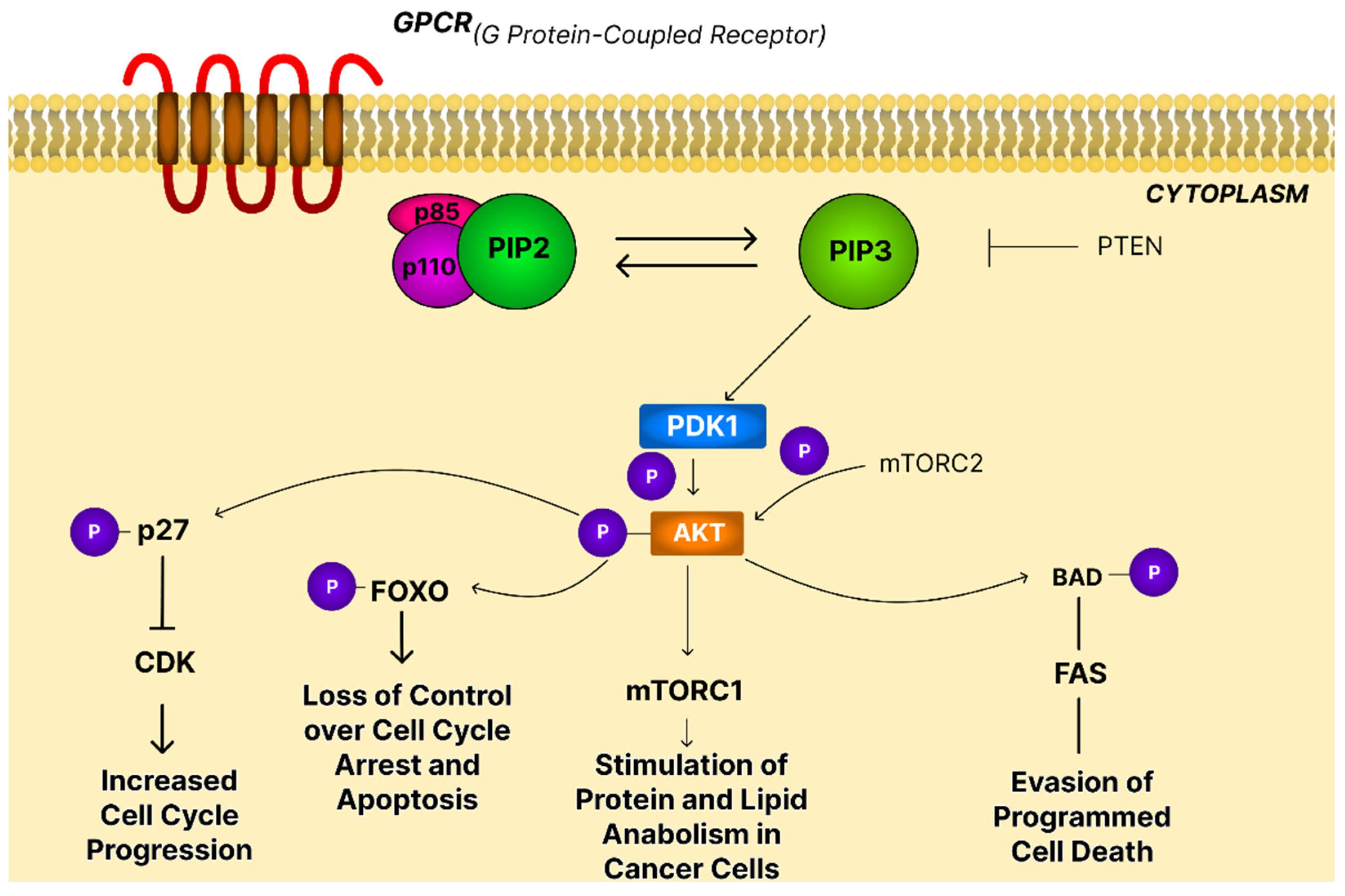

4.1. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway

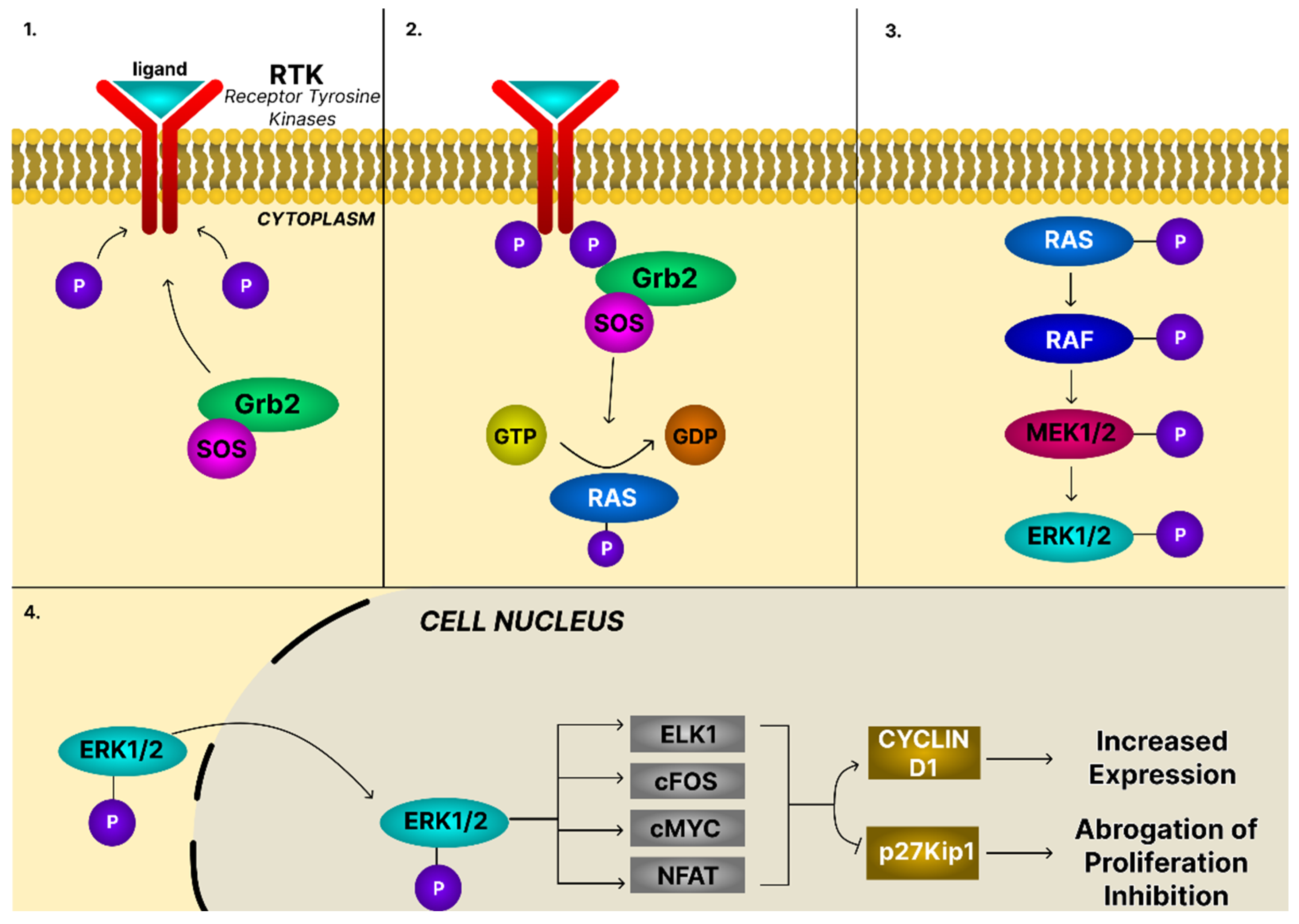

4.2. The MAPK/ERK Signaling Pathway

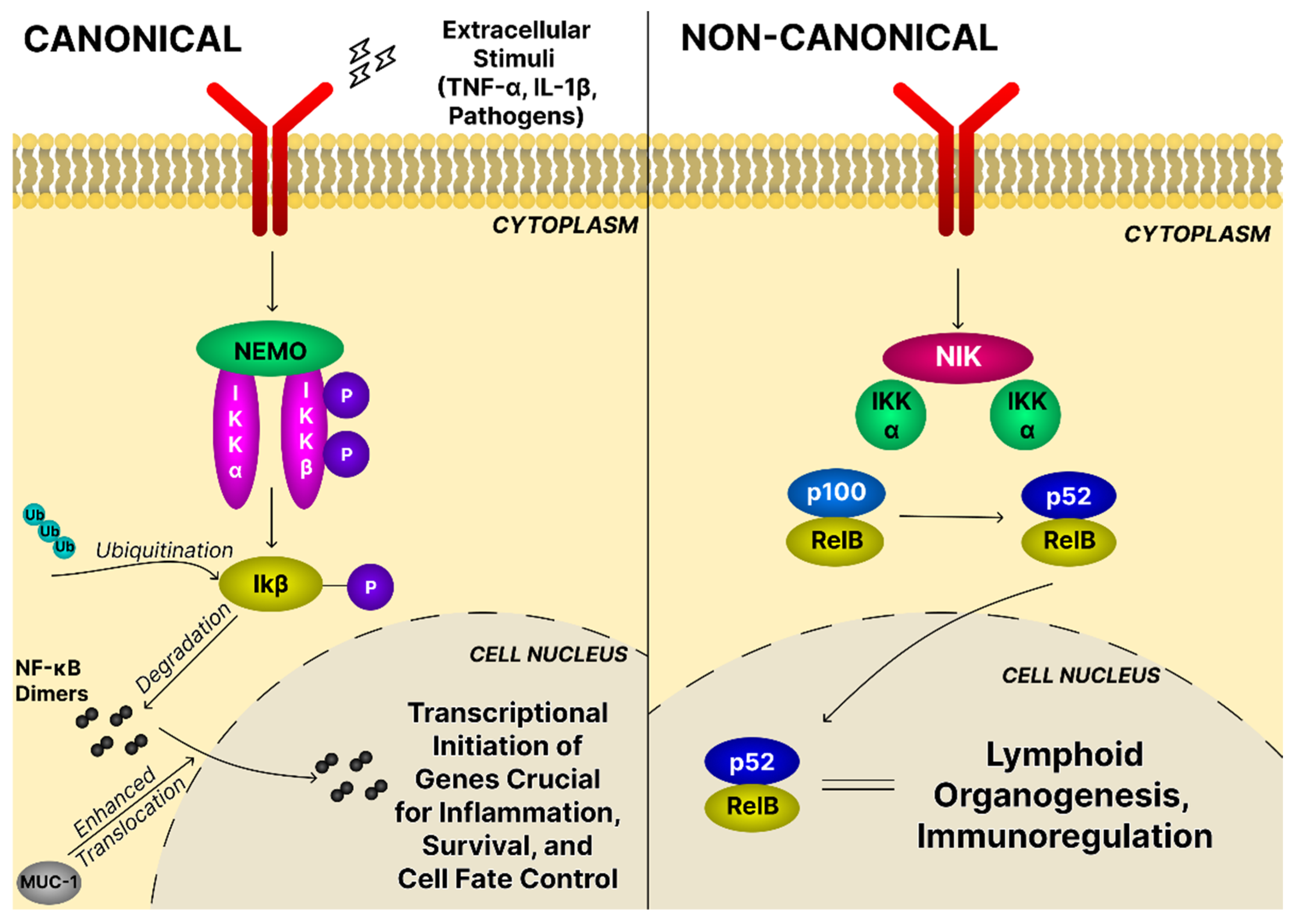

4.3. The NF-κB Signaling Pathway

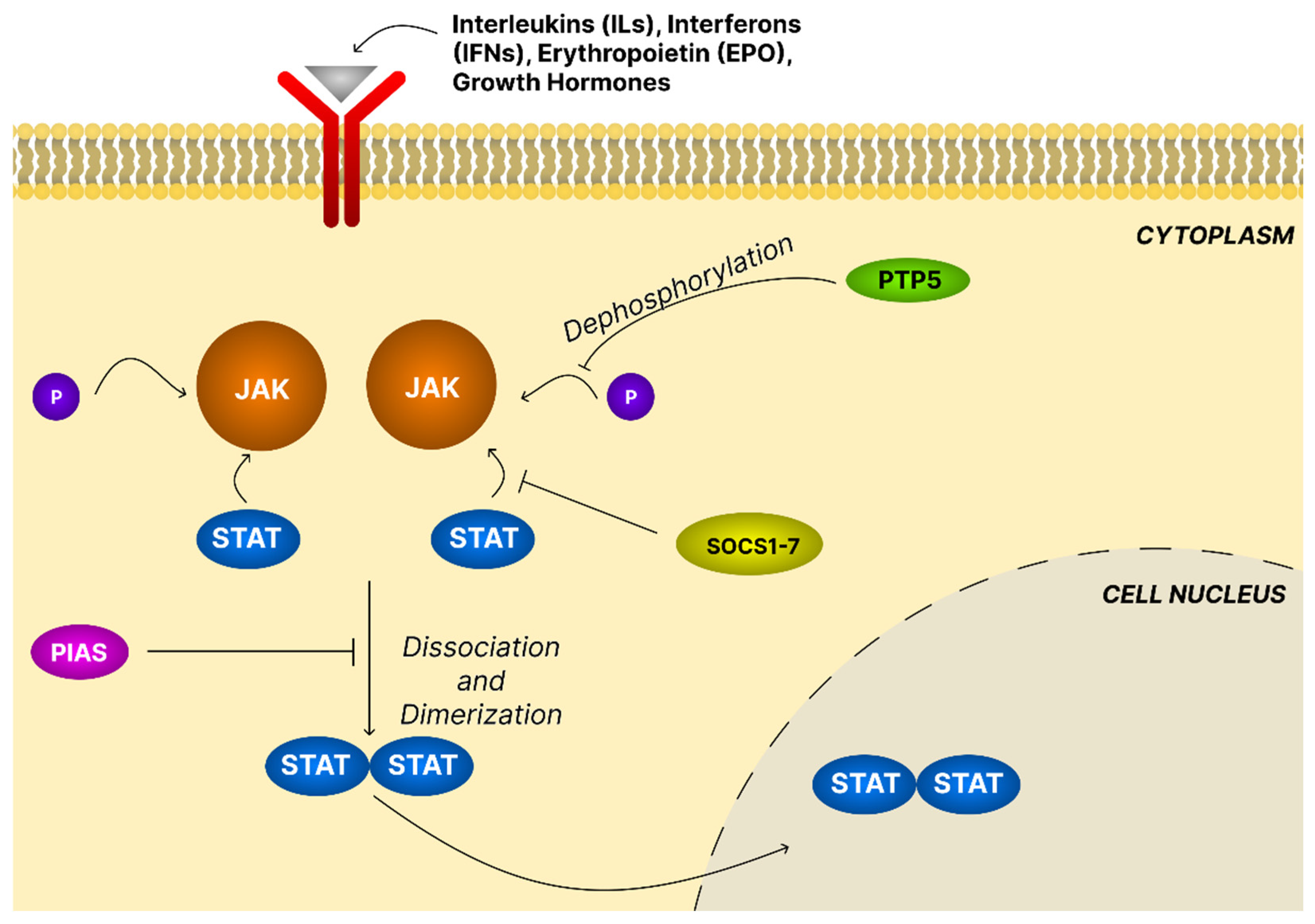

4.4. The JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

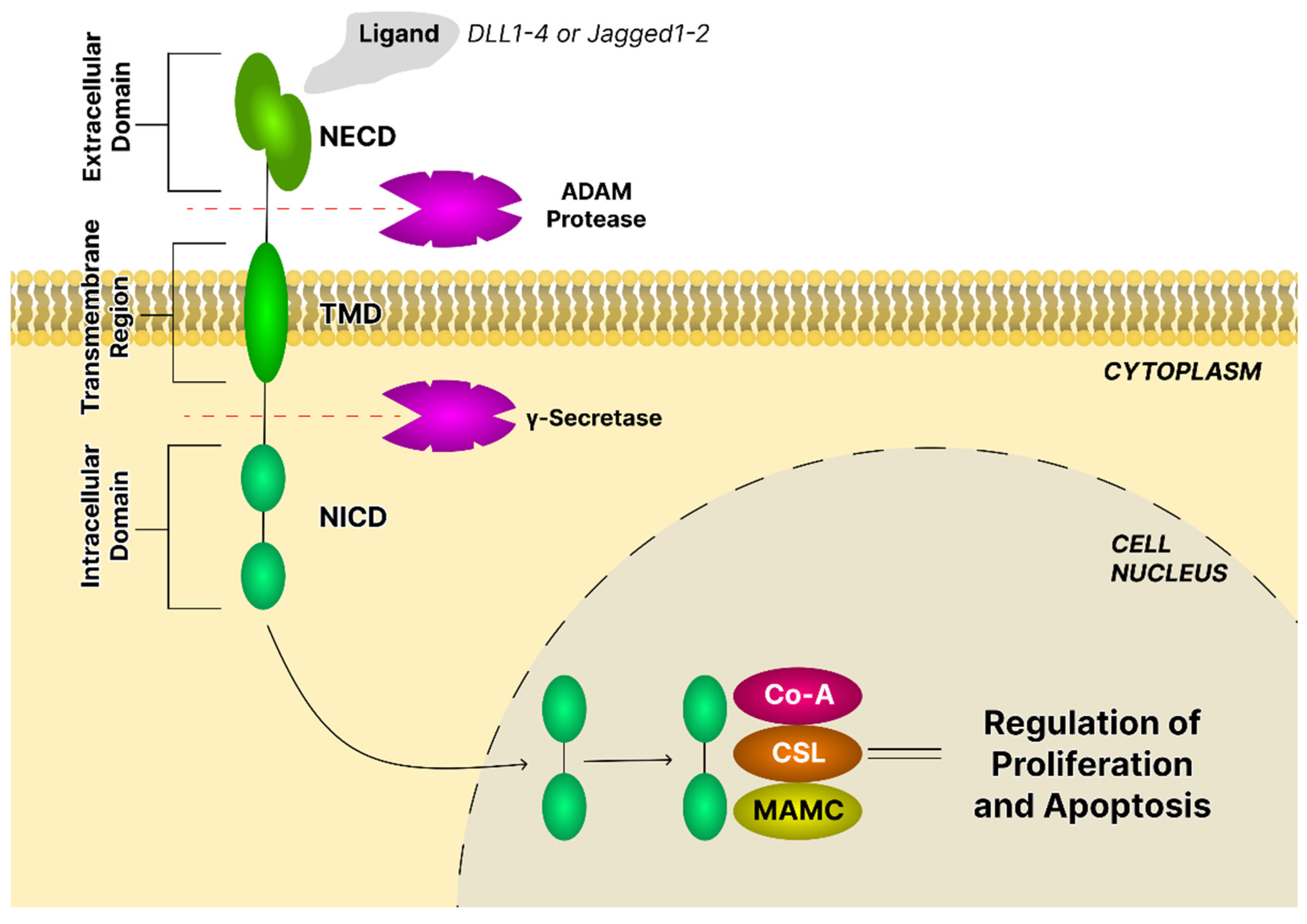

4.5. The Notch Signaling Pathway

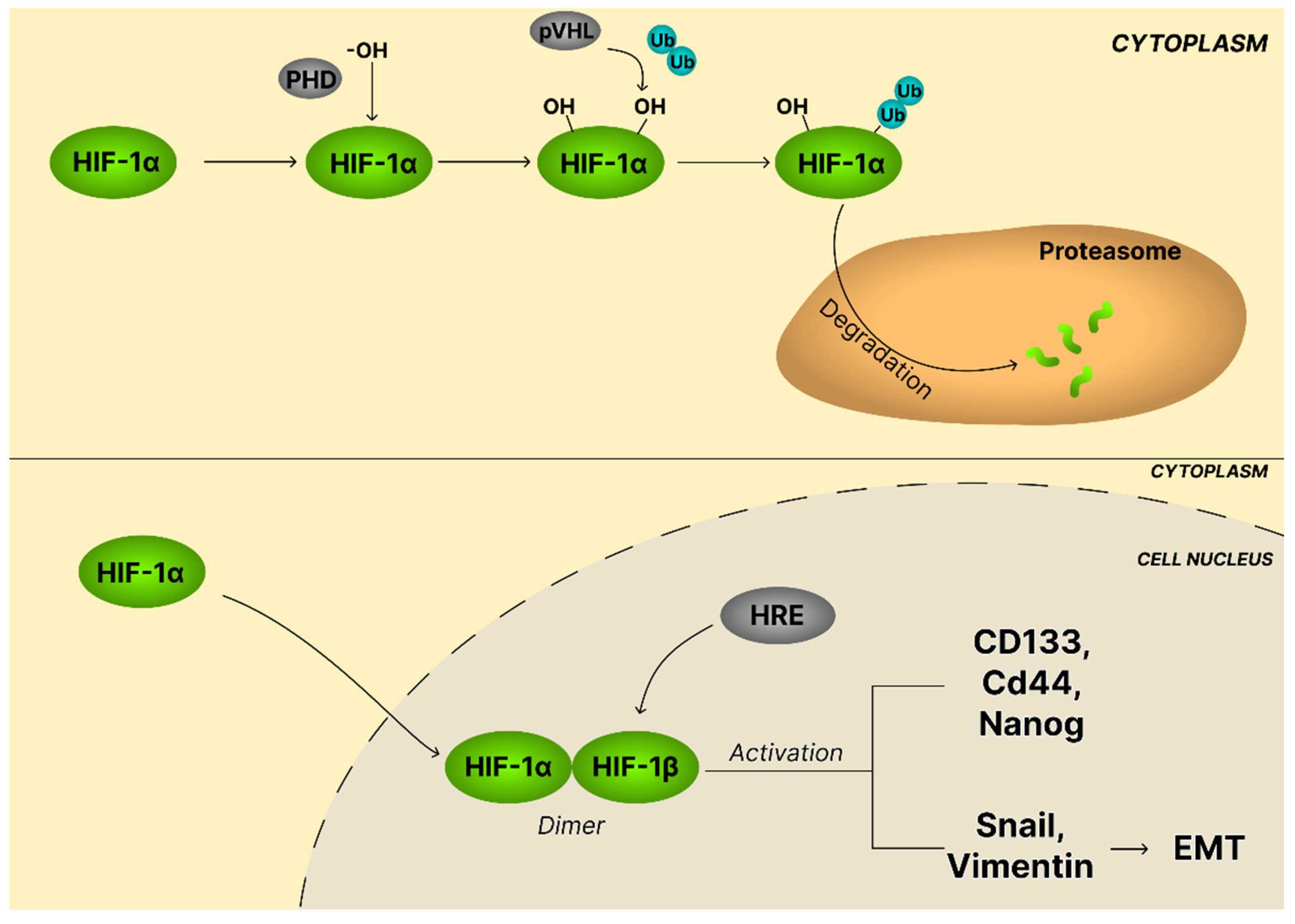

4.6. The HIF-1α Signaling Pathway

4.7. The TGF-β Signaling Pathway

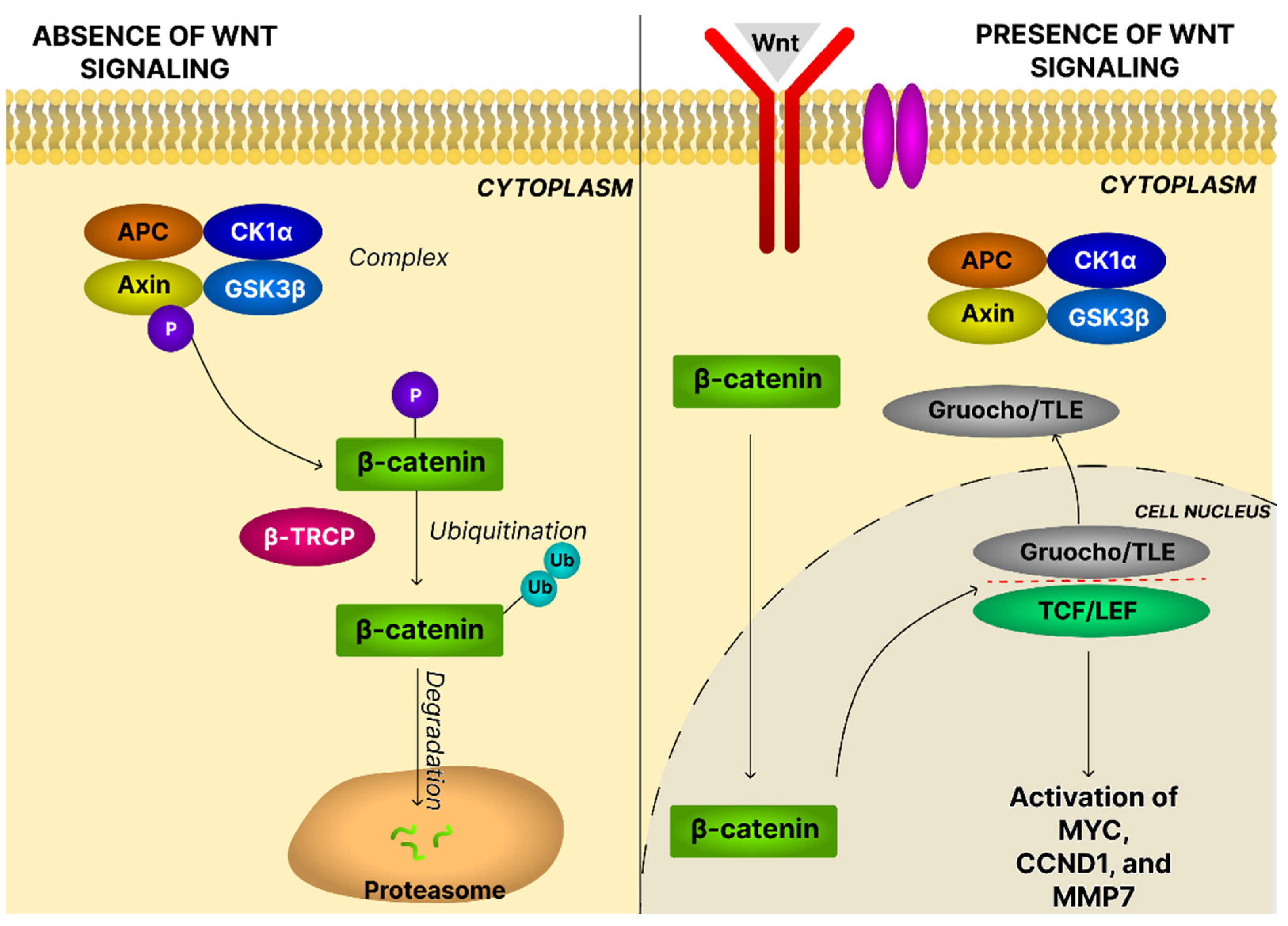

4.8. The Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway

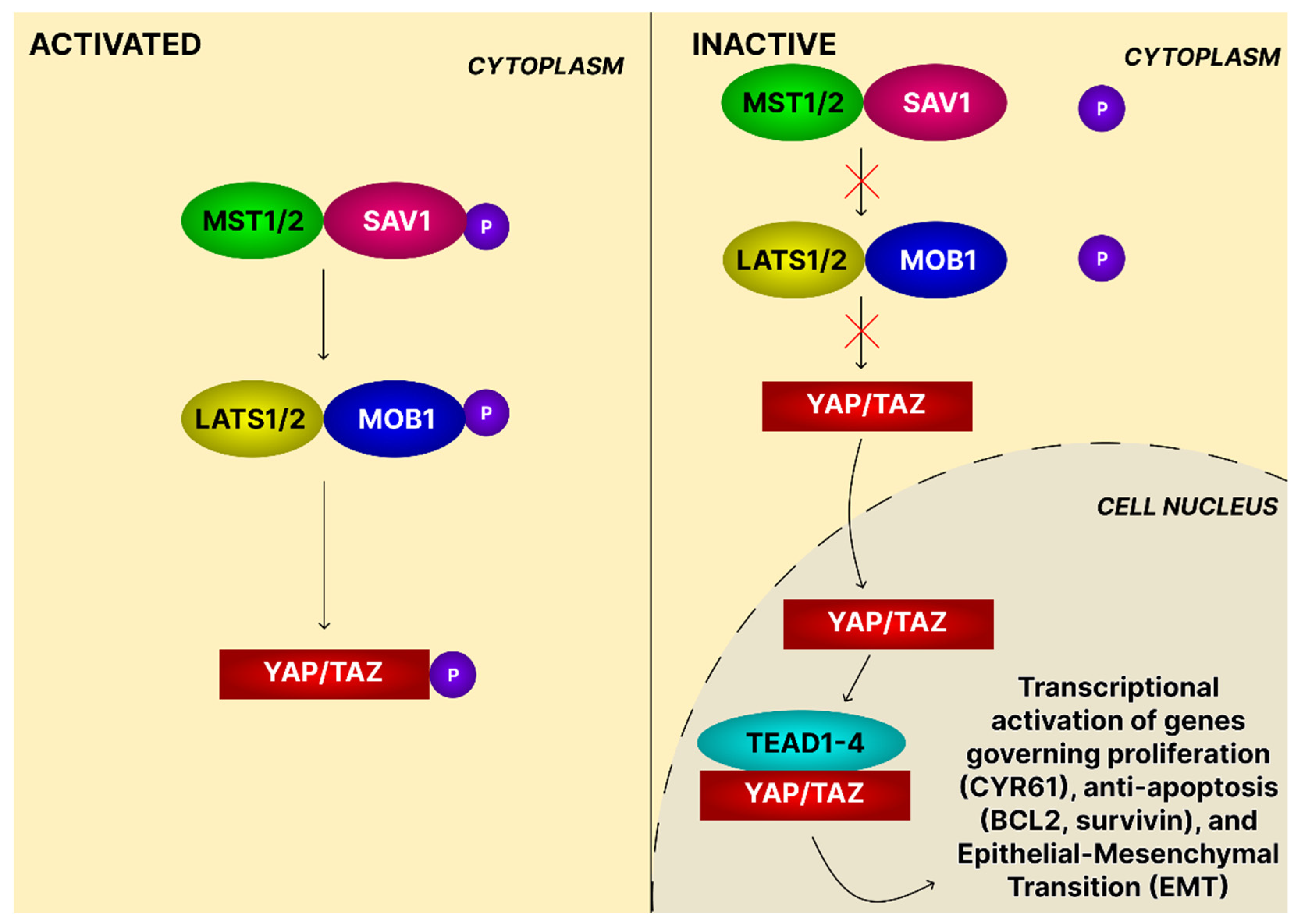

4.9. The Hippo Signaling Pathway

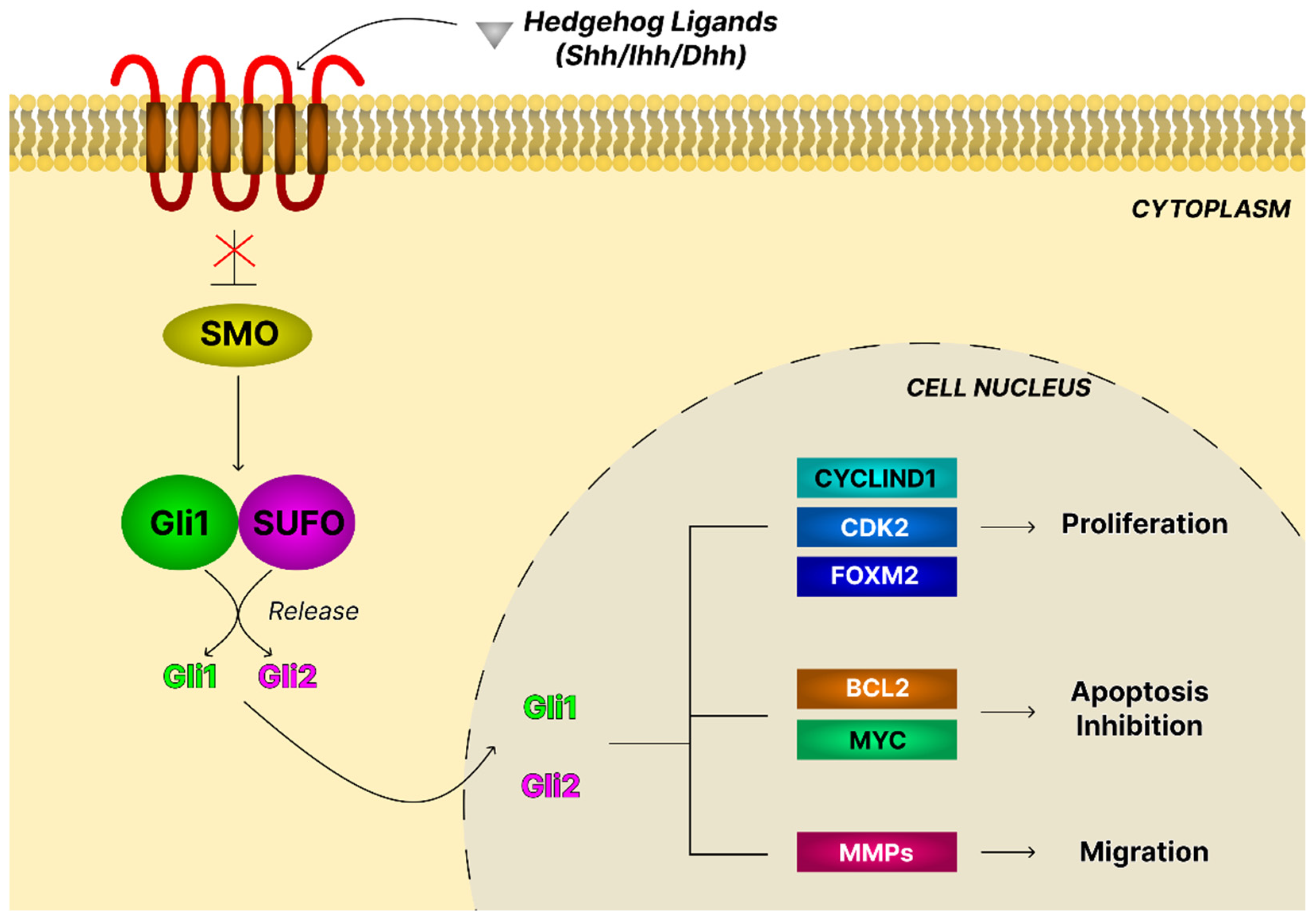

4.10. The Hedgehog Signaling Pathway

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Asiatic acid |

| ABCG2 | Adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding cassette efflux transporter G2 |

| APC | Adenomatous polyposis coli |

| ARNT | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator |

| ATM | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated |

| β-TRCP | β-transducin repeat-containing protein |

| BA | Betulinic acid |

| BAD | Bcl-2-associated agonist of cell death |

| BATF | Basic leucine zipper transcription factor |

| Bax | Bcl-2 associated X |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 |

| Bcl-xL | B-cell lymphoma-extra large |

| BM (CDDO-Me) | Bardoxolone methyl |

| BMPs | Bone morphogenetic proteins |

| BRCA | Breast Cancer Gene |

| BTK | Bruton tyrosine kinase |

| CDDO-Im | 2-cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9(11)-dien-28-oic acid imidazolide |

| CDK | Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| CDKN2A/B | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/B |

| cIAP | Inhibitor of apoptosis |

| CK1α | Casein kinase 1α |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| CRA | 2α,3β-dihydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

| CSL | Supressor of Hairless |

| CTGF | Connective tissue growth factor |

| Dhh | Desert hedgehog |

| DIM | 3,3′-diindoylmethane |

| DLL | Delta-like |

| DUSPs | Dual-specificity phosphatases |

| Dvl | Dishevelled |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| EPHA5 | Ephrin type-A receptor 5 |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| ER | Estrogen receptor |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FCGBP | Fc gamma binging protein |

| FOXO | Forkhead box O |

| Fzd | Frizzled (Fzd) |

| FOXM1 | Forhead box M1 |

| GA | Glycyrrhetinic acid |

| GARP | Glycoprotein A repetitions predominant |

| GPCRs | G protein-coupled receptors |

| GSK3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| HGSOC | High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma |

| Hh | Hedgehog |

| HIFs | Hypoxia-inducible factors |

| HREs | Hypoxia-response elements |

| HUVECs | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| Ihh | Indian hedgehog |

| IKK | IkappaB kinase |

| IL | Interleukin |

| INF | Interferon |

| KRAS | Kristen rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| LAP | Latency-associated peptide |

| LATS1/2 | Large tumor suppressor 1/2 |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain |

| LLCs | Large latent complexes |

| LOX | Lipooxygenase |

| LRP5/6 | Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 |

| LTBP | Latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein |

| MAML | Mastermind-like |

| Mcl-1 | Myeloid leukemia-1 |

| MDM2 | Murine double minute 2 |

| MEK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MMP | Metaloproteinase |

| MST1/2 | Mammalian Ste20-like serine/threonine kinases |

| mTORC | Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex |

| NECD | Extracellular domain |

| NEMO | NF-κB essential modulator |

| NFAT | Nuclear factor of activated T-cells |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NICD | Intracellular domain |

| NIK | NF-κB-inducing kinase |

| OA | Oleanolic acid |

| OC | Ovarian cancer |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PCP | Wnt/Planar Cell Polarity |

| PDK1 | Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PHDs | Oxygen- and iron-dependent prolyl hydroxylases |

| PI3K/AKT/mTOR | Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin |

| PIAS | Protein inhibitors of activated STATs |

| PIK3CA | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha |

| PIP2 | Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate |

| PIP3 | Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate |

| PORCN | Porcupine |

| Ptch1 | Transmembrane receptor Patched |

| PTEN | Phosphate and tensin homolog |

| PTPs | Protein tyrosine phosphatases |

| PTs | Pentacyclic triterpenoids |

| pVHL | von Hippel–Lindau ubiquitin ligase complex |

| Raf | Rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma |

| Ras/MAPK | Rat sarcoma virus/mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| RASSF1 | Ras association domain family protein 1 |

| RGD | Arg-Gly-Asp |

| ROCK | Rho-associated protein kinase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RTKs | Receptor tyrosine kinases |

| S6K | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase |

| SAV1 | Salvador homolog 1 |

| SH2 | Src homology 2 |

| Shh | Sonic hedgehog |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin1 |

| Smac | Second mitochondrial-derived activator of caspase |

| Smo | G-protein-coupled receptor Smoothened |

| SOCS | Suppressors of cytokine signaling |

| SREBP1 | Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| SWH | Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway |

| TβRI, TβRII | TGF-β type I and type II receptors |

| TCF/LEF | T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer factor |

| TCTP | Translationally controlled tumor protein |

| TEAD | TEA domain |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor |

| TIMP | Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase |

| TLE | Transducin-like enhancer of split |

| TMD | Transmembrane region |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TRAIL-APO-2L | TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand/apoptosis ligand 2 |

| TSP-1 | Thrombospondin-1 |

| UA | Ursolic acid |

| U-STATs | Unphosphorylated STATs |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR-2 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) |

| YAP/TAZ | Yes-associated protein/transcriptional coactivator with PDZ-binding motif |

| ZEB1 | Zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 |

References

- Ali, A.T.; Al-Ani, O.; Al-Ani, F. Epidemiology and risk factors for ovarian cancer. Przegl. Menopauz. 2023, 22, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B.; Biernacka, K.; Lukasiewicz, H.; Samulak, D.; Piekarska, E.; Romanowicz, H.; Makowska, M. Ovarian Cancer-Epidemiology, Classification, Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Estrogen Receptors’ Molecular Backgrounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, S.B.; Kim, B.R.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, C.H. Translationally Controlled Tumor Protein Enhances Angiogenesis in Ovarian Tumors by Activating Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 Signaling. Biomol. Ther. 2025, 33, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Huang, H.; Chen, Y.; He, K.; Fang, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tao, F. Latest Advancements of Natural Products in Combating Ovarian Cancer. J. Cancer 2025, 16, 3497–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, G.A.; Adamson, D.C. Similarities in Mechanisms of Ovarian Cancer Metastasis and Brain Glioblastoma Multiforme Invasion Suggest Common Therapeutic Targets. Cells 2025, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.N.; Xie, L.Z.; Shen, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Fu, Y.; Liu, F.Y.; Han, F.J. Insights into the Role of Oxidative Stress in Ovarian Cancer. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 8388258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Lan, H.; Jiang, X.; Zeng, D.; Xiao, S. Bcl-2 family: Novel insight into individualized therapy for ovarian cancer (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 46, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Qin, J. Ovarian cancer targeted therapy: Current landscape and future challenges. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1535235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Song, S.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J. Case report: A panorama gene profile of ovarian cancer metastasized to axillary lymph node. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1548102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H.; Akbarabadi, P.; Dadfar, A.; Tareh, M.R.; Soltani, B. A comprehensive overview of ovarian cancer stem cells: Correlation with high recurrence rate, underlying mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sliwa, A.; Szczerba, A.; Pieta, P.P.; Bialas, P.; Lorek, J.; Nowak-Markwitz, E.; Jankowska, A. A Recipe for Successful Metastasis: Transition and Migratory Modes of Ovarian Cancer Cells. Cancers 2024, 16, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Yin, Q.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Huang, J.; Chen, B.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, L.; Wang, J. Inflammation and Immune Escape in Ovarian Cancer: Pathways and Therapeutic Opportunities. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Shi, H.; Ye, J.; Qi, X. Exploring Strategies to Prevent and Treat Ovarian Cancer in Terms of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Huang, Z.; Qin, P.; Xie, Z.; Cai, X.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Tian, Y.; et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Axis in Cancer: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. MedComm 2025, 6, e70295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stover, E.H.; Lee, E.K.; Shapiro, G.I.; Brugge, J.S.; Matulonis, U.A.; Liu, J.F. The RAS-MEK-ERK pathway in low-grade serous ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2025, 200, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Yi, Y.; Han, C.; Shi, B. NF-κB signaling pathway in tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1476030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Chen, K.; Zheng, F.; Gong, W.; Chao, D.; Lu, C. FCGBP promotes ovarian cancer progression via activation of IL-6/JAK-STAT signaling pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hang, W.; Jing, Z.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Luo, H.; Lv, H.; Tao, X.; Timashev, P.; et al. The role of notch signaling pathway in cancer: Mechanistic insights, therapeutic potential, and clinical progress. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1567524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Lu, J.; Qian, Q.; Tang, M.; Liu, M. PNO1 enhances ovarian cancer cell growth, invasion, and stemness via activating the AKT/Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K.; Chen, Y.; Dong, J. Amplification of Hippo Signaling Pathway Genes Is Governed and Implicated in the Serous Subtype-Specific Ovarian Carcino-Genesis. Cancers 2024, 16, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, N.D.; Hanker, L.C.; Gyorffy, B.; Bartha, A.; Proppe, L.; Gotte, M. The Prognostic Value of the Hedgehog Signaling Pathway in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmkshatriya, P.P.; Brahmkshatriya, P.S. Terpenes: Chemistry, Biological Role, and Therapeutic Applications. In Natural Products: Phytochemistry, Botany and Metabolism of Alkaloids, Phenolics and Terpenes; Ramawat, K.G., Mérillon, J.-M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 2665–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, D.P.; Damasceno, R.O.S.; Amorati, R.; Elshabrawy, H.A.; de Castro, R.D.; Bezerra, D.P.; Nunes, V.R.V.; Gomes, R.C.; Lima, T.C. Essential Oils: Chemistry and Pharmacological Activities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, J.; Mandal, S.C. Pentacyclic triterpenoids: Diversity, distribution and their propitious pharmacological potential. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 24, 4791–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Song, W.; Li, M.; Hua, X.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Xue, Z. Natural products of pentacyclic triterpenoids: From discovery to heterologous biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 1303–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liu, R.H. Triterpenoids isolated from apple peels have potent antiproliferative activity and may be partially responsible for apple’s anticancer activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4366–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, S.; Trojan, H.; Kopp, T.; Laszczyk, M.N.; Scheffler, A. Pentacyclic triterpene distribution in various plants-rich sources for a new group of multi-potent plant extracts. Molecules 2009, 14, 2016–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtado, A.N.J.C.; Furtado, N.A.; Pirson, L.; Edelberg, H.; Miranda, L.M.; Loira-Pastoriza, C.; Preat, V.; Larondelle, Y.; André, C.M. Pentacyclic Triterpene Bioavailability: An Overview of In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Molecules 2017, 22, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glensk, M.; Czapinska, E.; Wozniak, M.; Ceremuga, I.; Wlodarczyk, M.; Terlecki, G.; Ziolkowski, P.; Seweryn, E. Triterpenoid Acids as Important Antiproliferative Constituents of European Elderberry Fruits. Nutr. Cancer 2017, 69, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J.T.; Dubery, I.A. Pentacyclic triterpenoids from the medicinal herb, Centella asiatica (L.) Urban. Molecules 2009, 14, 3922–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.J.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, J.S.; Kang, D.G.; Lee, H.S. Protective role of betulinic acid on TNF-alpha-induced cell adhesion molecules in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Nisar, M.; Qaisar, M.; Khan, A.; Khan, A.A. Evaluation of the cytotoxic potential of a new pentacyclic triterpene from Rhododendron arboreum stem bark. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1927–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.Y.; Wu, X.J.; Gao, Y.; Rankin, G.O.; Pigliacampi, A.; Bucur, H.; Li, B.; Tu, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.C. Inhibitory Effects of Total Triterpenoid Saponins Isolated from the Seeds of the Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis) on Human Ovarian Cancer Cells. Molecules 2017, 22, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, H.J. Determination of sterol and triterpene content of Ocimum basilicum and Salvia officinalis at various stages of growth. J. Pharm. Sci. 1961, 50, 645–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.C.; Fu, X.Q.; Guo, H.; Li, T.; Wu, Z.Z.; Chan, K.; Yu, Z.L. The genus Rosa and arthritis: Overview on pharmacological perspectives. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 114, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Xue, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C.; Bi, C.; Shan, A. Oleanolic acid enhances tight junctions and ameliorates inflammation in Salmonella typhimurium-induced diarrhea in mice via the TLR4/NF-κB and MAPK pathway. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safayhi, H.; Sailer, E.R. Anti-inflammatory actions of pentacyclic triterpenes. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laszczyk, M.N. Pentacyclic triterpenes of the lupane, oleanane and ursane group as tools in cancer therapy. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siewert, B.; Wiemann, J.; Kowitsch, A.; Csuk, R. The chemical and biological potential of C ring modified triterpenoids. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 72, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Lin, Q.; Yu, J.; Lin, M.; Zhao, N. Oleanolic acid alleviates ovarian cancer by regulating the miR-122/PDK4 axis to induce autophagy and inhibit glycolysis in vivo and in vitro. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1670758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Yu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, N. Oleanolic Acid (OA) Targeting UNC5B Inhibits Proliferation and EMT of Ovarian Cancer Cell and Increases Chemotherapy Sensitivity of Niraparib. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 5887671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiqiang, D.; Yongli, Z.; Xiaohui, H. Study on the Effects of Oleanolic Acid on the Proliferation, Invasion and Metastasis of Human Ovarian Cancer SKOV3 Cells and Its Mechanism. China Pharm. 2020, 31, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Deeb, D.; Arbab, A.S.; Guo, A.M.; Dulchavsky, S.A.; Gautam, S.C. Synthetic oleanane triterpenoid, CDDO-Me, induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells by inhibiting prosurvival AKT/NF-κB/mTOR signaling. Anticancer Res. 2011, 31, 3673–3681. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, D.; Wang, W.; Lei, H.; Luo, H.; Cai, H.; Tang, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J.; Xiao, W.; et al. CDDO-Me reveals USP7 as a novel target in ovarian cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 77096–77109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghshenas, V.; Fakhari, S.; Mirzaie, S.; Rahmani, M.; Farhadifar, F.; Pirzadeh, S.; Jalili, A. Glycyrrhetinic Acid inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer a2780 cells. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2014, 4, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, V.K.; Budhauliya, A.; Jaggi, M.; Singh, A.T.; Rajput, S.K. Tumor-suppressing effect of bartogenic acid in ovarian (SKOV-3) xenograft mouse model. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2021, 394, 1815–1826, Erratum in Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2021, 394, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Mu, Y.; Wang, F.; Song, L.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J. Synthesis of gypsogenin derivatives with capabilities to arrest cell cycle and induce apoptosis in human cancer cells. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2018, 5, 171510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tang, F.; Li, R.; Chen, Z.; Lee, S.M.; Fu, C.; Zhang, J.; Leung, G.P. Dietary compound glycyrrhetinic acid suppresses tumor angiogenesis and growth by modulating antiangiogenic and proapoptotic pathways in vitro and in vivo. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 77, 108268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.X.; Liang, J.; Haridas, V.; Gaikwad, A.; Connolly, F.P.; Mills, G.B.; Gutterman, J.U. A plant triterpenoid, avicin D, induces autophagy by activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, T.; Arya, R.K.; Meena, S.; Joshi, P.; Pal, M.; Meena, B.; Upreti, D.K.; Rana, T.S.; Datta, D. Isolation, Characterization and Anticancer Potential of Cytotoxic Triterpenes from Betula utilis Bark. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerwerk, S.; Heller, L.; Kuhfs, J.; Csuk, R. Urea derivates of ursolic, oleanolic and maslinic acid induce apoptosis and are selective cytotoxic for several human tumor cell lines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 119, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Ye, H. Anticancer activity of ursolic acid on human ovarian cancer cells via ROS and MMP mediated apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and downregulation of PI3K/AKT pathway. J. BUON 2020, 25, 750–756. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Luo, L.; Shi, W.; Yin, Y.; Gao, S. Ursolic acid reduces Adriamycin resistance of human ovarian cancer cells through promoting the HuR translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Qian, L.; Zhang, Q.; Lai, D.; Qi, C. Ursolic acid inhibits the proliferation of human ovarian cancer stem-like cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 34, 2375–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Cao, Q.X.; Zhai, F.R.; Yang, S.Q.; Zhang, H.X. Asiatic acid exerts anticancer potential in human ovarian cancer cells via suppression of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 2377–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, K.H.; Park, J.H.; Lee, D.K.; Fu, Y.Y.; Baek, N.I.; Chung, I.S. Pomolic acid induces apoptosis in SK-OV-3 human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells through the mitochondrial-mediated intrinsic and death receptor-induced extrinsic pathways. Oncol. Lett. 2013, 5, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Takaishi, K.; Nakao, J.; Ikeda, T.; Katabuchi, H.; Takeya, M.; Komohara, Y. Corosolic acid enhances the antitumor effects of chemotherapy on epithelial ovarian cancer by inhibiting signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling. Oncol. Lett. 2013, 6, 1619–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, F.; Bian, Y.; Miao, L.; Wang, X. Asiatic acid attenuates malignancy of human metastatic ovarian cancer cells via inhibition of epithelial-tomesenchymal transition. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 16, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, O.; Hartmann, A.K.; Brandt, S.; Hoenke, S.; Heise, N.V.; Csuk, R.; Mueller, T. Asiatic acid as a leading structure for derivatives combining sub-nanomolar cytotoxicity, high selectivity, and the ability to overcome drug resistance in human preclinical tumor models. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 250, 115189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodurek, E.; Orchel, A.; Gwiazdon, P.; Kaps, A.; Paduszynski, P.; Jaworska-Kik, M.; Chrobak, E.; Bebenek, E.; Boryczka, S.; Kasperczyk, J. Antiproliferative and Cytotoxic Properties of Propynoyl Betulin Derivatives against Human Ovarian Cancer Cells: In Vitro Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Fei, Z.; Huang, C. Betulin terpenoid targets OVCAR-3 human ovarian carcinoma cells by inducing mitochondrial mediated apoptosis, G2/M phase cell cycle arrest, inhibition of cell migration and invasion and modulating mTOR/PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2021, 67, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuco, V.; Supino, R.; Righetti, S.C.; Cleris, L.; Marchesi, E.; Gambacorti-Passerini, C.; Formelli, F. Selective cytotoxicity of betulinic acid on tumor cell lines, but not on normal cells. Cancer Lett. 2002, 175, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Lee, S.R.; Kang, K.S.; Ko, Y.; Pang, C.; Yamabe, N.; Kim, K.H. Betulinic Acid Suppresses Ovarian Cancer Cell Proliferation through Induction of Apoptosis. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzeski, W.; Stepulak, A.; Szymanski, M.; Sifringer, M.; Kaczor, J.; Wejksza, K.; Zdzisinska, B.; Kandefer-Szerszen, M. Betulinic acid decreases expression of bcl-2 and cyclin D1, inhibits proliferation, migration and induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2006, 374, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, L.; Liu, C.; Xie, X.; Zhou, J. Betulinic acid induces apoptosis and impairs migration and invasion in a mouse model of ovarian cancer. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, F.; Yu, J.Q.; Beale, P.; Chan, C.; Arzuman, L.; Nessa, M.U.; Mazumder, M.E. Combinations of platinums and selected phytochemicals as a means of overcoming resistance in ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 541–545. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.J.; Liu, J.B.; Dou, Y.C. Sequential treatment with betulinic acid followed by 5-fluorouracil shows synergistic cytotoxic activity in ovarian cancer cells. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Zhang, B. Lupeol Inhibits Proliferation and Promotes Apoptosis of Ovarian Cancer Cells by Inactivating Phosphoinositide-3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Pathway. Curr. Top. Nutraceutical Res. 2021, 19, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Deeb, D.; Arbab, A.S.; Gautam, S.C. Anticancer activity of pristimerin in ovarian carcinoma cells is mediated through the inhibition of prosurvival Akt/NF-κB/mTOR signaling. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 2014, 10, 275–283. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Li, G.; Wang, S. Effects of celastrol on enhancing apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells via the downregulation of microRNA-21 and the suppression of the PI3K/Akt-NF-κB signaling pathway in an in vitro model of ovarian carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 5363–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lan, S.; Han, B.; Wang, X. Taraxasterol inhibits cell proliferation and angiogenesis in ovarian cancer by targeting EphA2. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2024, 45, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akihisa, T.; Tokuda, H.; Ichiishi, E.; Mukainaka, T.; Toriumi, M.; Ukiya, M.; Yasukawa, K.; Nishino, H. Anti-tumor promoting effects of multiflorane-type triterpenoids and cytotoxic activity of karounidiol against human cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2001, 173, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, J. Glutinol inhibits the proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2022, 20, 1331–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Aubel, C. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Resistance Pathway and a Prime Target for Targeted Therapies. Cancers 2025, 17, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Sun, M.M.; Zhang, G.G.; Yang, J.; Chen, K.S.; Xu, W.W.; Li, B. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zheng, L.; Ma, L.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, N.; Liu, G.; Lin, X. Oleanolic acid inhibits proliferation and invasiveness of Kras-transformed cells via autophagy. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, L.; Yu, Z.; Gao, R.; Zhang, Z.R.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, X.; Chen, Y.; Jiao, S.; et al. In vitro analysis of the molecular mechanisms of ursolic acid against ovarian cancer. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2025, 25, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Lu, B.; Lu, C.; Bai, Q.; Yan, D.; Xu, H. Taraxerol Induces Cell Apoptosis through A Mitochondria-Mediated Pathway in HeLa Cells. Cell J. 2017, 19, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamska, A.; Stefanowicz-Hajduk, J.; Ochocka, J.R. Alpha-Hederin, the Active Saponin of Nigella sativa, as an Anticancer Agent Inducing Apoptosis in the SKOV-3 Cell Line. Molecules 2019, 24, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, B.; Wang, H. Alpha-hederin induces the apoptosis of oral cancer SCC-25 cells by regulating PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 38, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Woo, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Jang, D.S.; Lee, K.T.; Choi, J.H. Eclalbasaponin II induces autophagic and apoptotic cell death in human ovarian cancer cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 132, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, M.; Ye, J.; Zhang, L.X.; Luan, Z.Y.; Chen, Y.B.; Huang, J.X. Celastrol induces apoptosis of gastric cancer cells by miR-21 inhibiting PI3K/Akt-NF-κB signaling pathway. Pharmacology 2014, 93, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Won, Y.S.; Park, K.H.; Lee, M.K.; Tachibana, H.; Yamada, K.; Seo, K.I. Celastrol inhibits growth and induces apoptotic cell death in melanoma cells via the activation ROS-dependent mitochondrial pathway and the suppression of PI3K/AKT signaling. Apoptosis 2012, 17, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, L.; Wang, B.; Xiang, J. Effects of ursolic acid on the proliferation and apoptosis of human ovarian cancer cells. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2009, 29, 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Mitra, D.; Alam, N.; Sen, S.; Mustafi, S.M.; Majumder, P.K.; Majumder, B.; Murmu, N. Lupeol and Paclitaxel cooperate in hindering hypoxia induced vasculogenic mimicry via suppression of HIF-1alpha-EphA2-Laminin-5gamma2 network in human oral cancer. J. Cell Commun. Signal 2023, 17, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Ge, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, K.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Q.; Xin, Y.; Guo, J. Betulinic acid targets drug-resistant human gastric cancer cells by inducing autophagic cell death, suppresses cell migration and invasion, and modulates the ERK/MEK signaling pathway. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2021, 69, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, G.; Yao, W.; Zhang, Q.; Bo, Y. Oleanolic acid suppresses migration and invasion of malignant glioma cells by inactivating MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, H.; You, J.; Peng, B.; Cao, F.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Q.; Uzan, G.; Xu, L.; et al. Celastrol improves the therapeutic efficacy of EGFR-TKIs for non-small-cell lung cancer by overcoming EGFR T790M drug resistance. Anticancer. Drugs 2018, 29, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Effects of taraxasterol on iNOS and COX-2 expression in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Zheng, X.; Yang, H. Multiflorane suppresses the proliferation, migration and invasion of human glioblastoma by targeting MAPK signalling pathway. J. BUON 2020, 25, 1631–1635. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G.J.; Jo, H.J.; Lee, K.J.; Choi, J.W.; An, J.H. Oleanolic acid induces p53-dependent apoptosis via the ERK/JNK/AKT pathway in cancer cell lines in prostatic cancer xenografts in mice. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 26370–26386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bai, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Cao, P.; Liao, N.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Hai, C. Inhibitory effect of oleanolic acid on hepatocellular carcinoma via ERK-p53-mediated cell cycle arrest and mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.H.; Jeong, S.J.; Kwon, H.Y.; Kim, B.; Kim, S.H.; Yoo, D.Y. Ursolic acid from Oldenlandia diffusa induces apoptosis via activation of caspases and phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta in SK-OV-3 ovarian cancer cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 35, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.L.; Kuo, P.L.; Lin, L.T.; Lin, C.C. Asiatic acid, a triterpene, induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest through activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in human breast cancer cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 313, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, R.; Satoh, R.; Takasaki, T. ERK: A Double-Edged Sword in Cancer. ERK-Dependent Apoptosis as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, N.; Abdulwahid, A.R.R.; Mansouri, A.; Karimi, N.; Bostani, R.J.; Beiranvand, S.; Adelian, S.; Khorram, R.; Vafadar, R.; Hamblin, M.R.; et al. Targeting the NF-κB pathway as a potential regulator of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Zhao, X.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB in inflammation and cancer. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2025, 22, 811–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, P.; Lakhanpal, S.; Mahmood, D.; Kang, H.N.; Kim, B.; Kang, S.; Choi, J.; Choi, M.; Pandey, S.; Bhat, M.; et al. An updated review summarizing the anticancer potential of flavonoids via targeting NF-kB pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1513422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, B.S.; Annunziata, C.M. NF-κB Signaling in Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Liu, Y.; Deeb, D.; Liu, P.; Liu, A.; Arbab, A.S.; Gautam, S.C. ROS mediate proapoptotic and antisurvival activity of oleanane triterpenoid CDDO-Me in ovarian cancer cells. Anticancer. Res. 2013, 33, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, W.; Huang, R.Z.; Zhang, J.; Guo, T.; Zhang, M.T.; Huang, X.C.; Zhang, B.; Liao, Z.X.; Sun, J.; Wang, H.S. Discovery of antitumor ursolic acid long-chain diamine derivatives as potent inhibitors of NF-κB. Bioorg Chem. 2018, 79, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhai, Z.; Du, X. Celastrol inhibits migration and invasion through blocking the NF-κB pathway in ovarian cancer cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 819–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, H.; An, H.; Alam, M.B.; Choi, W.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, S.H. Inhibition of Migration and Invasion in Melanoma Cells by beta-Escin via the ERK/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2018, 41, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, V.L.; Soni, R.; Dhyani, P.; Sati, P.; Tejada, S.; Sureda, A.; Setzer, W.N.; Faizal Abdull Razis, A.; Modu, B.; Butnariu, M.; et al. Anti-cancer properties of boswellic acids: Mechanism of action as anti-cancerous agent. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1187181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, E.; Zhang, A.; Franco, D.; Gupta, S. Betulinic Acid-Mediated Apoptosis in Human Prostate Cancer Cells Involves p53 and Nuclear Factor-Kappa B (NF-κB) Pathways. Molecules 2017, 22, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Q.L.; Li, H.L.; Li, Y.C.; Liu, Z.W.; Guo, X.H.; Cheng, Y.J. CRA(Crosolic Acid) isolated from Actinidia valvata Dunn.Radix induces apoptosis of human gastric cancer cell line BGC823 in vitro via down-regulation of the NF-κB pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 105, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lou, C.; Xu, X.; Feng, B.; Fan, X.; Wang, X. Ursolic Acid Ameliorates Diabetic Nephropathy by Inhibiting JAK2/STAT3-Driven Ferroptosis: Mechanistic Insights from Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 6699–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Luo, S.; Yin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Qiu, L.; Wu, X. DLAT is involved in ovarian cancer progression by modulating lipid metabolism through the JAK2/STAT5A/SREBP1 signaling pathway. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Zhang, B.; Xu, A.; Shen, Z.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, R.; Yao, H.; Shao, J.-W. Carrier-Free, Pure Nanodrug Formed by the Self-Assembly of an Anticancer Drug for Cancer Immune Therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 2466–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.Y.; Sp, N.; Lee, J.M.; Jang, K.J. Antitumor Effects of Ursolic Acid through Mediating the Inhibition of STAT3/PD-L1 Signaling in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Shin, E.A.; Jung, J.H.; Park, J.E.; Kim, D.S.; Shim, B.S.; Kim, S.-H. Ursolic Acid Induces Apoptosis in Colorectal Cancer Cells Partially via Upregulation of MicroRNA-4500 and Inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 Phosphorylation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 20, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Luo, W.; Khan, Z.A.; Wu, G.; Xuan, L.; Shan, P.; Lin, K.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; et al. Celastrol Attenuates Angiotensin II–Induced Cardiac Remodeling by Targeting STAT3. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1007–1023, Erratum in Circ Res. 2022, 130, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.K.; Sung, B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Betulinic acid suppresses STAT3 activation pathway through induction of protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1 in human multiple myeloma cells. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, P. Notch signaling in the tumor immune microenvironment of colorectal cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.S.; Lv, H.L.; Nie, R.Z.; Liu, Y.P.; Hou, Y.J.; Chen, C.; Tao, X.Y.; Luo, H.M.; Li, P.F. Notch signaling in cancer: Metabolic reprogramming and therapeutic implications. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1656370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.; Tiwari, R.K.; Mishra, P.; Alkhathami, A.G.; Almeleebia, T.M.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Ahmad, I.; Asiri, R.A.; Alabdullah, N.M.; Hussien, M.; et al. Antiproliferative and apoptotic potential of Glycyrrhizin against HPV16+ Caski cervical cancer cells: A plausible association with downreguation of HPV E6 and E7 oncogenes and Notch signaling pathway. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 3264–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Cheng, X.; Yin, Q.; Xia, L.; Rui, K.; Sun, B. Asiatic acid attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced injury by suppressing activation of the Notch signaling pathway. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 15036–15046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, J.Y.; Lin, J.J.; Wahler, J.; Liby, K.T.; Sporn, M.B.; Suh, N. A synthetic triterpenoid CDDO-Im inhibits tumorsphere formation by regulating stem cell signaling pathways in triple-negative breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, P.P.; Singh, A.K.; Shuaib, M.; Prajapati, K.S.; Vardhan, P.S.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, S. 3-O-(E)-p-Coumaroyl betulinic acid possess anticancer activity and inhibit Notch signaling pathway in breast cancer cells and mammosphere. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 328, 109200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuna-Pilarte, K.; Koh, M.Y. The HIF axes in cancer: Angiogenesis, metabolism, and immune-modulation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2025, 50, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Wu, L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha promotes cancer stem cells-like properties in human ovarian cancer cells by upregulating SIRT1 expression. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-J.; Sui, H.; Qi, C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wu, S.-F.; Mei, M.-Z.; Lu, Y.-Y.; Wan, Y.-T.; Chang, H.; et al. Ursolic acid inhibits proliferation and reverses drug resistance of ovarian cancer stem cells by downregulating ABCG2 through suppressing the expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in vitro. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 36, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tong, T.; Ren, N.; Rankin, G.O.; Rojanasakul, Y.; Tu, Y.; Chen, Y.C. Theasaponin E1 Inhibits Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer Cells through Activating Apoptosis and Suppressing Angiogenesis. Molecules 2021, 26, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, K.A.; Amjad, M.; Irfan, M.T.; Anjum, S.; Majeed, T.; Riaz, M.U.; Jassim, A.Y.; Sharif, E.A.M.; Ibrahim, W.N. Exploring TGF-beta Signaling in Cancer Progression: Prospects and Therapeutic Strategies. Onco Targets Ther. 2025, 18, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yu, X.; Wen, L.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Kan, R.; Zhang, W.; Shen, Y.; et al. USP9X integrates TGF-beta and hypoxia signalings to promote ovarian cancer chemoresistance via HIF-2alpha-maintained stemness. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecerska-Heryc, E.; Jerzyk, A.; Goszka, M.; Polikowska, A.; Rachwalska, J.; Serwin, N.; Wojciuk, B.; Dolegowska, B. TGF-beta Signaling in Cancer: Mechanisms of Progression and Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Nilsson, M.; Sundfeldt, K. TGF-beta isoforms induce EMT independent migration of ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int. 2014, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.R.; Ren, J.; Zhou, Q.W.; Yang, Q.M.; Li, B. Effect of asiatic acid on epithelial-mesenchymal transition of human alveolar epithelium A549 cells induced by TGF-1. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 4285–4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patricia Goncalves Tenorio, L.; Xavier, F.; Silveira Wagner, M.; Moreira Bagri, K.; Alves Ferreira, E.G.; Galvani, R.; Mermelstein, C.; Bonomo, A.C.; Savino, W.; Barreto, E. Uvaol attenuates TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human alveolar epithelial cells by modulating expression and membrane localization of beta-catenin. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1504556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cai, Q.Y.; Liu, J.; Peng, J.; Chen, Y.Q.; Sferra, T.J.; Lin, J.M. Ursolic acid suppresses the invasive potential of colorectal cancer cells by regulating the TGF-beta1/ZEB1/miR-200c signaling pathway. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 3274–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Que, H.; Li, Q.; Wei, X. Wnt/beta-catenin mediated signaling pathways in cancer: Recent advances, and applications in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.-X.; Li, Y.; Tian, D.-D.; Liu, Y.; Nian, W.; Zou, X.; Chen, Q.-Z.; Zhou, L.-Y.; Deng, Z.-L.; He, B.-C. Ursolic acid inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis by inactivating Wnt/β-catenin signaling in human osteosarcoma cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 1973–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Tang, S.; Tao, Q.; Ming, T.; Lei, J.; Liang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Yang, H.; et al. Ursolic Acid Suppresses Colorectal Cancer by Down-Regulation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 3981–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Bao, X.; Zhao, A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, B. Raddeanin A inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in human colorectal cancer through downregulating the Wnt/β-catenin and NF-κB signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2018, 207, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Liang, H.; Qin, X.; Mo, Y.; Chen, S.; Xie, J.; Hou, X.; Deng, J.; Hao, E.; et al. Hippo/YAP signaling pathway in colorectal cancer: Regulatory mechanisms and potential drug exploration. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1545952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bala, R.; Madaan, R.; Bedi, O.; Singh, A.; Taneja, A.; Dwivedi, R.; Figueroa-Gonzalez, G.; Reyes-Hernandez, O.D.; Quintas-Granados, L.I.; Cortes, H.; et al. Targeting the Hippo/YAP Pathway: A Promising Approach for Cancer Therapy and Beyond. MedComm 2025, 6, e70338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; Zhou, X. Targeting Hippo signaling in cancer: Novel perspectives and therapeutic potential. MedComm 2023, 4, e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Hu, Y.; Lan, T.; Guan, K.L.; Luo, T.; Luo, M. The Hippo signalling pathway and its implications in human health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 376, Erratum in Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Chang, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Li, M.; Fan, H.Y. YAP promotes ovarian cancer cell tumorigenesis and is indicative of a poor prognosis for ovarian cancer patients. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91770, Erratum in PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Jin, H.; Meng, R.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Chai, O.H.; Park, B.H.; Kim, S.M. Activating Hippo Pathway via Rassf1 by Ursolic Acid Suppresses the Tumorigenesis of Gastric Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, R.Y.; Li, C.S.; Hu, D.; Kwon, S.G.; Jin, H.; Chai, O.H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, S.M. Inhibition of the interaction between Hippo/YAP and Akt signaling with ursolic acid and 3′3-diindolylmethane suppresses esophageal cancer tumorigenesis. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2023, 27, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Meng, R.Y.; Nguyen, T.V.; Chai, O.H.; Park, B.H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, S.M. Inhibition of colorectal cancer tumorigenesis by ursolic acid and doxorubicin is mediated by targeting the Akt signaling pathway and activating the Hippo signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 27, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, G.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X.R.; Chen, H.; Chong, W. Mechanisms and therapeutic potential of the hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2025, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.; Xia, Y.; Fu, Y.; Cao, Q.; Chen, W.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, K.; Sun, L. Hedgehog pathway and cancer: A new area (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2024, 52, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, W.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, J.; Guo, Q. Recent Advances of Natural Pentacyclic Triterpenoids as Bioactive Delivery System for Synergetic Biological Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Shang, J.; Tao, C.; Huang, M.; Wei, D.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Fan, Q.; Ding, Q.; Zhou, M. Advancements in Betulinic Acid-Loaded Nanoformulations for Enhanced Anti-Tumor Therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 14075–14103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmila, A.; Bhadra, P.; Kishore, C.; Selvaraj, C.I.; Kavalakatt, J.; Bishayee, A. Nanoformulated Terpenoids in Cancer: A Review of Therapeutic Applications, Mechanisms, and Challenges. Cancers 2025, 17, 3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhi, K.; Yang, X. Exploration of the Natural Active Small-Molecule Drug-Loading Process and Highly Efficient Synergistic Antitumor Efficacy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 6827–6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Ma, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Chen, Z.; Chen, A.T.; Yang, X.; Avery, J.; et al. Anti-edema and antioxidant combination therapy for ischemic stroke via glyburide-loaded betulinic acid nanoparticles. Theranostics 2019, 9, 6991–7002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Qiao, W.; Cheng, J.; Han, Y.; Yang, X. Nanomedicine-Cum-Carrier by Co-Assembly of Natural Small Products for Synergistic Enhanced Antitumor with Tissues Protective Actions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 42537–42550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Structure | Compound | Molecular Target | Biological Effect | Cancer Cell Model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oleanane-type | Oleanolic acid | ↓: AKT/mTOR/S6K | ↑: autophagy; ↓: cell proliferation, invasiveness | KRAS-transformed MCF10A xenografted mouse | [76] |

| ↓: MAPK/ERK | ↓: migration, invasiveness | U-87MG, U-251MG | [87] | ||

| ↓: MAPK/ERK | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | DU145 | [91] | ||

| ↑: MAPK/ERK | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | MCF-7, U87 | [91] | ||

| ↑: MAPK/ERK | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | HepG2 | [92] | ||

| Bartogenic acid | ↓: NF-κB | ↓: cell viability, necrosis | SK-OV-3 xenografted mouse | [46] | |

| Glycyrrhetinic acid | ↓: MAPK/ERK | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, angiogenesis | A2780, HUVEC | [48] | |

| Glycyrrhizic acid | ↑: p21/WAF1; ↓: Notch | ↓: cell proliferation | HPV16+ CaSki | [116] | |

| Alpha-hederin | ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ↑: apoptosis | SK-OV-3, SCC-25 | [79,80] | |

| Eclalbosaponin II | ↑: MAPK; ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ↑: apoptosis, autophagy; ↓: cell proliferation | SK-OV-3, A2780 | [81] | |

| β-escin | ↓: NF-κB | ↓: migration, invasiveness | B16F10, SK-MEL5 | [103] | |

| Theasaponin E1 | ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Notch, HIF-1α | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, migration, angiogenesis | OVCAR-3 | [123] | |

| Raddeanin A | ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin, NF-κB | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | SW480, LOVO | [134] | |

| CDDO-Me | ↓: NF-κB | ↑: apoptosis, oxidative stress | OVCAR-5, MDAH-2774 | [100] | |

| CDDO-Im | ↓: Notch, TGF-β | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, EMT | SUM159 | [118] | |

| Ursane-type | Ursolic acid | ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: autophagy | SK-OV-3 | [77] |

| ↓: MAPK/ERK | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | CAOV3 | [84] | ||

| ↑: MAPK/ERK | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | SK-OV-3 | [93] | ||

| ↓: JAK/STAT3 | ↑: antioxidative, anti-ferroptosis | NRK-52E | [107] | ||

| ↓: STAT3 | ↓: cell viability | A549 | [109] | ||

| ↓: JAK/STAT3 | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, colony formation, angiogenesis, migration, invasiveness | A549, H460 | [110] | ||

| ↓: STAT3 | ↑: apoptosis | HCT116, HT29 | [111] | ||

| ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR, HIF-1α | ↓: adaptation to hypoxic stress, angiogenesis | SK-OV-3 | [122] | ||

| ↓: TGF-β1 | ↓: cell proliferation, migration, invasiveness | HCT-116, HCT-8 | [130] | ||

| ↑: p53; ↓: Wnt/β-catenin | ↓: cell proliferation | 143B | [132] | ||

| ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Wnt/β-catenin | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, migration, clonality | SW620 | [133] | ||

| ↑: Hippo | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell viability, migration, invasiveness | SNU484, SNU638 | [140] | ||

| 2α,3β-dihydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid | ↓: NF-κB | ↑: apoptosis | BGC823 | [106] | |

| Ursolic acid-derivatives with a diamide gallic acid moiety | ↓: NF-κB | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, migration | SK-OV-3, A549, HepG2, T24 | [101] | |

| Ursolic acid with 3,3′-diindoylmethane | ↑: Hippo; ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, migration | TE-8, TE-12 | [141] | |

| Ursolic acid with doxorubicin | ↑: Hippo; ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, migration, EMT | HCT116, HT29 | [142] | |

| Asiatic acid | ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell viability, colony formation | OVCAR-3, SK-OV-3 | [55] | |

| ↑: MAPK/ERK | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 | [94] | ||

| ↓: Notch | ↓: inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction | RAW264.7 | [117] | ||

| ↓: TGF-β1 | ↓: EMT | SK-OV-3 | [58] | ||

| ↓: TGF-β1 | ↓: EMT | A549 | [128] | ||

| β-Boswellic acid | ↓: NF-κB | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | PC-3 | [104] | |

| Uvaol | ↓: TGF-β1 | ↓: EMT | A549 | [129] | |

| Lupane-type | Lupeol | ↓: MAPK/ERK | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, migration | UPCI:SCC154, UPCI:SCC090 | [85] |

| Betulin | ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation, migration, invasiveness | OVCAR-3 | [61] | |

| Betulinic acid | ↓: MAPK/ERK | ↑: autophagy; ↓: cell proliferation, migration, invasiveness | SGC-7901 | [86] | |

| ↑: p21/WAF1; ↓: NF-κB | ↑: apoptosis | LNCaP, DU145 | [105] | ||

| ↓: JAK/STAT3 | ↑: apoptosis | U266 | [113] | ||

| ↓: STAT3 | ↑: apoptosis | A293 | [113] | ||

| Betulinic acid with 5-fluorouracil | ↓: Hedgehog | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | OVCAR 432, RMS-13 | [67] | |

| 3-O-(E)-p-coumaroylbetulinic acid | ↓: Notch | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell viability, cell proliferation | MBA-MD-231, T47D | [119] | |

| Friedelane-type | Celastrol | ↓: PI3KAKT/mTOR, NF-κB | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | OVCAR-3, BGC823, MGC803 | [70,82] |

| ↓: PI3KAKT/mTOR | ↑: apoptosis | B16 | [83] | ||

| ↓: NF-κB | ↓: migration, invasiveness | OVCAR-3, SK-OV-3 | [102] | ||

| ↓: STAT3 | ↓: fibrosis, hypertrophy | rat cardiomiocytes | [112] | ||

| Pristimerin | ↓: PI3KAKT/mTOR, NF-κB | ↑: apoptosis; ↓: cell proliferation | OVCAR-5, MDAH-2774, OVCAR-3, SK-OV-3 | [69] | |

| Taraxastane-type | Taraxerol | ↓: PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ↑: apoptosis | LPS-induced RAW264.7, HeLa | [78] |

| Multiflorane-type | Multiflorane | ↓: MAPK/ERK | ↑: apoptosis ↓: cell proliferation, migration, invasiveness | U87 | [90] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orchel, A.; Skrobek, J.; Kaps, A.; Paduszyński, P.; Chodurek, E. Current Research on the Control Mechanisms of Cell Survival and Proliferation as Potential Interaction Sites with Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311622

Orchel A, Skrobek J, Kaps A, Paduszyński P, Chodurek E. Current Research on the Control Mechanisms of Cell Survival and Proliferation as Potential Interaction Sites with Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in Ovarian Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311622

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrchel, Arkadiusz, Jonasz Skrobek, Anna Kaps, Piotr Paduszyński, and Ewa Chodurek. 2025. "Current Research on the Control Mechanisms of Cell Survival and Proliferation as Potential Interaction Sites with Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in Ovarian Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311622

APA StyleOrchel, A., Skrobek, J., Kaps, A., Paduszyński, P., & Chodurek, E. (2025). Current Research on the Control Mechanisms of Cell Survival and Proliferation as Potential Interaction Sites with Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in Ovarian Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11622. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311622