Beyond Tumor Immunity: The Disruption of Endocrine and Infectious Homeostasis by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

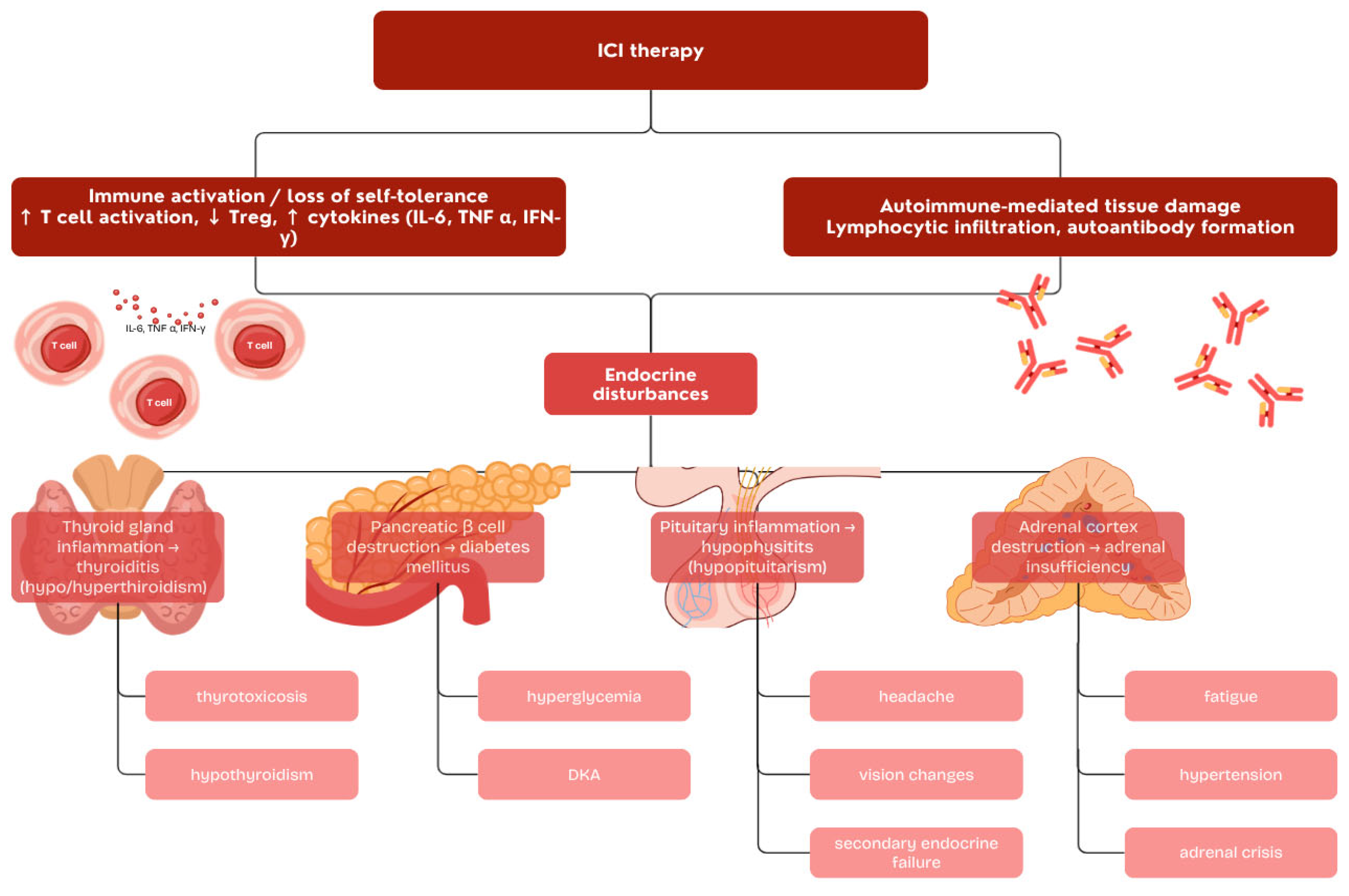

2. Overview of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Immune-Related Adverse Events

3. Endocrine Immune-Related Adverse Events

3.1. Thyroid Dysfunction

3.2. Hypophysitis

3.3. Adrenal Dysfunction

3.4. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Diabetes Mellitus

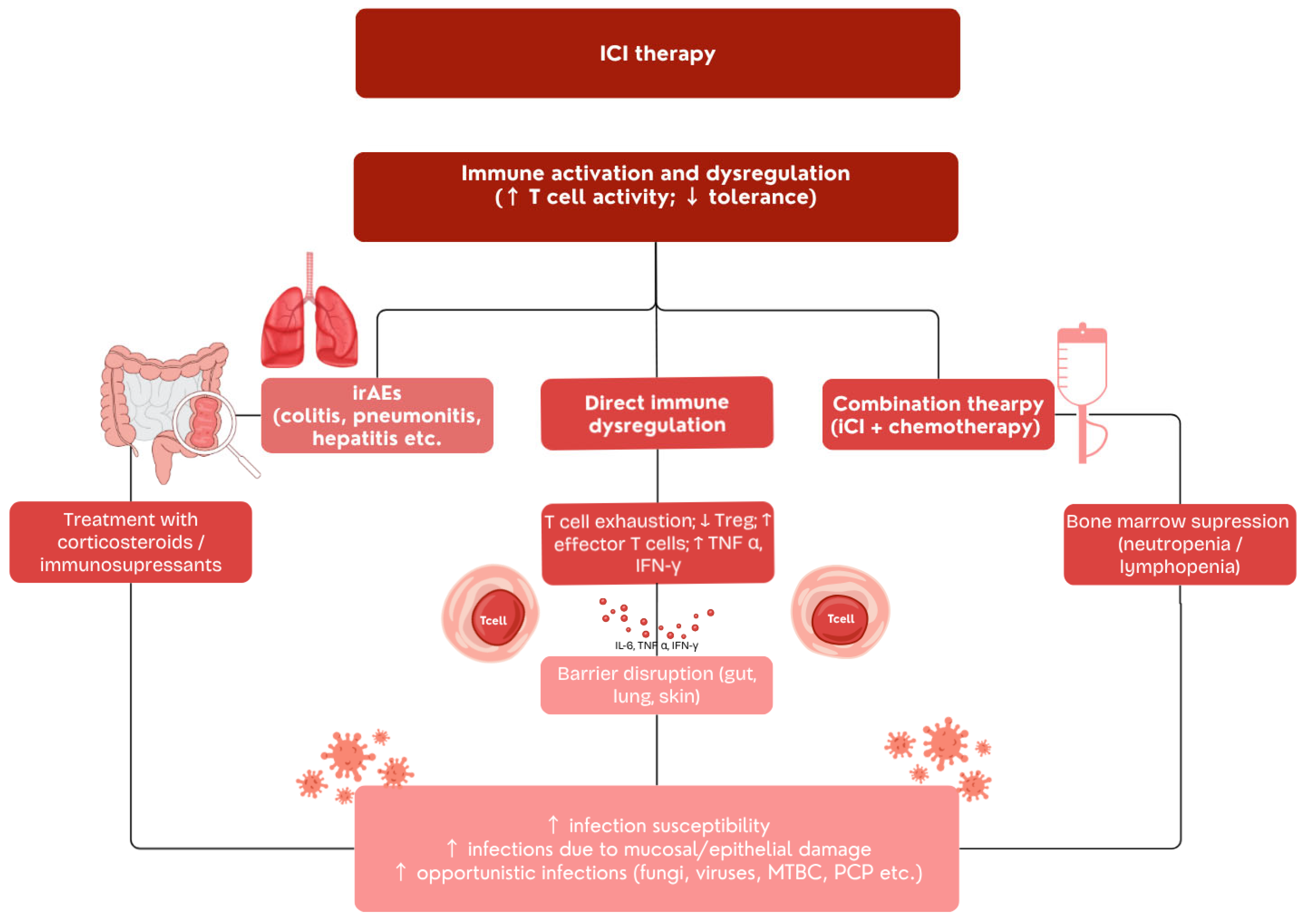

4. Infectious Complications in ICI-Treated Patients

4.1. Infection Risk from ICI Therapy Alone

4.2. Infections Associated with Immunosuppressive Treatment of irAEs

4.3. Endocrine Dysfunction as a Risk Factor for Infections

4.3.1. Thyroid Dysfunction and Infection Risk

4.3.2. Hypophysitis and Adrenal Insufficiency

4.3.3. Diabetes Mellitus and Infection Susceptibility

| Author, Year (Journal) | Study Design & Population | Infection Focus | Key Results/Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Del Castillo et al., 2016 (Clin. Infect. Dis.) [90] | Retrospective analysis: melanoma patients treated with ICIs | General infection risk | Approximately 7% developed infections; mostly bacterial (85%), some opportunistic cases. |

| Zhang et al., 2019 (J. Immunother. Cancer) [97] | 114 HBsAg+ cancer patients treated with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors | HBV reactivation | 5.3% experienced HBV reactivation (median 18 weeks), 5 developed hepatitis; prophylaxis reduced risk significantly. |

| Uchida et al., 2018 (Respirol. Case Rep.) [108] | Single patient, nivolumab therapy | Fungal infection (chronic pulmonary aspergillosis) | Nearly complete tumor response but worsening fungal infection; immune hyperactivation suspected (IRIS-like). |

| Picchi et al., 2018 (Clin. Microbiol. Infect.) [88] Fujita et al., 2019 (Respir. Med.) [92] Langan et al., 2020 (Lancet Oncol.) [96] | Multiple reports, mostly melanoma and NSCLC patients | Tuberculosis reactivation under PD-1 therapy | Several cases of active/latent TB reactivation; attributed to PD-1 pathway blockade and Th1 hyperactivation. |

| Franklin et al., 2017 (Eur. J. Cancer) [107] | Melanoma patients with ICI-colitis treated with steroids/infliximab | CMV colitis/hepatitis | CMV reactivation mimicking refractory autoimmune colitis; confirmed by biopsy, mostly responsive to ganciclovir. |

| Picasso et al., 2023 (Radiol. Med.) [99] | Cancer patients on ICIs during pandemic | Differentiating ICI-pneumonitis from COVID-19 | False-negative RT-PCR (estimated at 12%); some COVID-19 cases misdiagnosed as ICI pneumonitis. |

| Babacan and Tanvetyanon, 2019. (J. Immunother.) [98] | Mostly lung adenocarcinoma patients with ICI-colitis | Clostridioides difficile infection | Diarrhea exacerbation in ICI colitis warrants suspicion for Clostridioides difficile infection |

| Gudiol et al., 2022 (Open Forum Infect. Dis.) [85] | Mostly melanoma, lung adenocarcinoma and NSCLC | VZV skin and CNS infections, vasculopathy + other pathogens | Assessment strategies to exclude occult infection in irAEs should follow a syndromic, suspicion-driven approach |

5. Challenges, Controversies, and Future Direction

5.1. Potential Challenges in the Differential Diagnosis of irAEs and Infectious Complications Associated with Checkpoint Inhibitors

5.2. Future Approach to the Treatment of irAEs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| AI | Adrenal insufficiency |

| CDAD | C. difficile associated disease |

| CMV CNS | Cytomegalovirus Central nervous system |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CPPA | Chronic progressive pulmonary aspergillosis |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| DKA | Diabetic ketoacidosis |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| fT4 | Free thyroxine |

| HbA1c | Glycated hemoglobin |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| ICI-DM | Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated diabetes mellitus |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| irAEs | Immune-related adverse events |

| IRIS | Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome |

| ITI-DI | ICI therapy-induced dysregulated immunity |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| T1DM | Type 1 diabetes mellitus |

| Treg | Regulatory T-lymphocytes |

| TSH | Thyroid-stimulating hormone |

| VZV | Varicella-zoster virus |

References

- Shiravand, Y.; Khodadadi, F.; Kashani, S.M.A.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Hosseini, S.; Sadeghirad, H.; Ladwa, R.; O’Byrne, K.; Kulasinghe, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Cancer Therapy. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haanen, J.B.A.G.; Robert, C. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Prog. Tumor Res. 2015, 42, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hargadon, K.M.; Johnson, C.E.; Williams, C.J. Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: An overview of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 62, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, A.; Mohammed, R.N.; Raji, A.; Chupradit, S.; Yumashev, A.V.; Suksatan, W.; Shalaby, M.N.; Thangavelu, L.; Kamrava, S.; Shomali, N.; et al. Tumor immunotherapies by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs); the pros and cons. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Rutkowski, P.; Lao, C.D.; Cowey, C.L.; Schadendorf, D.; Wagstaff, J.; Dummer, R.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes with Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab or Nivolumab Alone Versus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.L.; Cho, B.C.; Luft, A.; Alatorre-Alexander, J.; Geater, S.L.; Laktionov, K.; Kim, S.; Ursol, G.; Hussein, M.; Lim, F.L.; et al. Durvalumab with or Without Tremelimumab in Combination with Chemotherapy as First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: The Phase III POSEIDON Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangro, B.; Chan, S.L.; Kelley, R.K.; Lau, G.; Kudo, M.; Sukeepaisarnjaroen, W.; Yarchoan, M.; De Toni, E.N.; Furuse, J.; Kang, Y.K.; et al. Four-year overall survival update from the phase III HIMALAYA study of tremelimumab plus durvalumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, T.; Honjo, T. The PD-1-PD-L pathway in immunological tolerance. Trends Immunol. 2006, 27, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasaki, J.; Ishino, T.; Togashi, Y. Mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 3303–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, R.W.; Colton, M.D.; Mitra, S.S.; Messersmith, W.A. Innate immune checkpoint inhibitors: The next breakthrough in medical oncology? Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wu, L.; Han, L.; Zheng, X.; Tong, R.; Li, L.; Bai, L.; Bian, Y. Immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: A review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1167975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriou, F.; Hogan, S.; Menzies, A.M.; Dummer, R.; Long, G.V. Interleukin-6 blockade for prophylaxis and management of immune-related adverse events in cancer immunotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 157, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano, A.X.; Chaudhuri, A.A.; Nene, A.; Bacchiocchi, A.; Earland, N.; Vesely, M.D.; Usmai, A.; Turner, B.E.; Steen, C.B.; Luca, B.A.; et al. T cell characteristics associated with toxicity to immune checkpoint blockade in patients with melanoma. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Management of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Related Toxicities. Version 1.2026. 23 October 2025. Available online: https://www.nccn.org (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Darnell, E.P.; Mooradian, M.J.; Baruch, E.N.; Yilmaz, M.; Reynolds, K.L. Immune-Related Adverse Events (irAEs): Diagnosis, Management, and Clinical Pearls. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postow, M.A.; Sidlow, R.; Hellmann, M.D. Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzanov, I.; Diab, A.; Abdallah, K.; Bingham, C.O.; Brogdon, C.; Dadu, R.; Hamad, L.; Kim, S.; Lacouture, M.E.; LeBoeuf, N.R.; et al. Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: Consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J. Immunother. Cancer 2017, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.J.; Naidoo, J.; Santomasso, B.D.; Lacchetti, C.; Adkins, S.; Anadkat, M.; Atkins, M.B.; Brassil, K.J.; Caterino, J.M.; Chau, I.; et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 4073–4126, Erratum in J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haanen, J.; Obeid, M.; Spain, L.; Carbonnel, F.; Wang, Y.; Robert, C.; Lyon, A.R.; Wick, W.; Kostine, M.; Peters, S.; et al. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 1217–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussaini, S.; Chehade, R.; Boldt, R.G.; Raphael, J.; Blanchette, P.; Maleki Vareki, S.; Fernandes, R. Association between immune-related side effects and efficacy and benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2021, 92, 102134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anpalakhan, S.; Huddar, P.; Behrouzi, R.; Signori, A.; Cave, J.; Comins, C.; Cortellini, A.; Addeo, A.; Escriu, C.; McKenuie, H.; et al. Immunotherapy-related adverse events in real-world patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer on chemoimmunotherapy: A Spinnaker study sub-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1163768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, X.; Fang, C.; Qia, X.; Li, Y. Peripheral blood markers predictive of outcome and immune-related adverse events in advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with PD-1 inhibitors. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2020, 69, 1813–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chennamadhavuni, A.; Abushahin, L.; Jin, N.; Presley, C.J.; Manne, A. Risk Factors and Biomarkers for Immune-Related Adverse Events: A Practical Guide to Identifying High-Risk Patients and Rechallenging Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 779691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Feng, H.F.; Liu, H.Q.; Guo, L.T.; Chen, C.; Yao, X.L.; Sun, S.R. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors-Related Thyroid Dysfunction: Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Possible Pathogenesis, and Management. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 649863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husebye, E.S.; Castinetti, F.; Criseno, S.; Curigliano, G.; Decallonne, B.; Fleseriu, M.; Higham, C.E.; Lupi, I.; Paschou, S.A.; Toth, M.; et al. Endocrine-related adverse conditions in patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibition: An ESE clinical practice guideline. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2022, 187, G1–G21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, X. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated thyroid dysfunction: A disproportionality analysis using the WHO adverse drug reaction database, VigiBase. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 182, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kethireddy, N.; Thomas, S.; Bindal, P.; Shukla, P.; Hegde, U. Multiple autoimmune side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors in a patient with metastatic melanoma receiving pembrolizumab. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract. 2021, 27, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, I.; Yabe, D. Best practices in the management of thyroid dysfunction induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur. Thyroid. J. 2025, 14, 240328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalan, P.; Di Dalmazi, G.; Pani, F.; De Remigis, A.; Corsello, A.; Caturegli, P. Thyroid dysfunctions secondary to cancer immunotherapy. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2018, 41, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filette, J.; Andreescu, C.E.; Cools, F.; Bravenboer, B.; Velkeniers, B. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Endocrine-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Horm. Metab. Res. 2019, 51, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabbagh REl Azar, N.S.; Eid, A.A.; Azar, S.T. Thyroid Dysfunctions Due to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Review. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2020, 13, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaviti, D.; Kani, E.R.; Karaviti, E.; Gerontiti, E.; Michalopoulou, O.; Stefanaki, K.; Kazakou, P.; Vasileiou, V.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Paschou, S.A. Thyroid disorders induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors. Endocrine 2024, 85, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Hocking, A.M.; Buckner, J.H. Immune related adverse events after immune check point inhibitors: Understanding the intersection with autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 318, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Smylie, M.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso-Sousa, R.; Barry, W.T.; Garrido-Castro, A.C.; Hodi, F.S.; Min, L.; Krop, I.E.; Tolaney, S.M. Incidence of endocrine dysfunction following the use of different immune checkpoint inhibitor regimens a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018, 4, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Osta, B.; Hu, F.; Sadek, R.; Chintalapally, R.; Tang, S.C. Not all immune-checkpoint inhibitors are created equal: Meta-analysis and systematic review of immune-related adverse events in cancer trials. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 119, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.N.; Whitelaw, B.C.; Palomar, M.T.P.; Wu, Y.; Carroll, P.V. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hypophysitis and endocrine dysfunction: Clinical review. Clin. Endocrinol. 2016, 85, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacques, J.P.; Valadares, L.P.; Moura, A.C.; Oliveira, M.R.F.; Naves, L.A. Frequency and clinical characteristics of hypophysitis and hypopituitarism in patients undergoing immunotherapy—A systematic review. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1091185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, S.; De Remigis, A.; Callahan, M.K.; Slovin, S.F.; Wolchok, J.D.; Caturegli, P. Pituitary expression of CTLA-4 mediates hypophysitis secondary to administration of CTLA-4 blocking antibody. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 230ra45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanie, K.; Iguchi, G.; Bando, H.; Urai, S.; Shichi, H.; Fujita, Y.; Matsumoto, R.; Suda, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Fukuoka, H.; et al. Mechanistic insights into immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hypophysitis: A form of paraneoplastic syndrome. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 70, 3669–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Leij, S.; Suijkerbuijk, K.P.M.; van den Broek, M.F.M.; Valk, G.D.; Dankbaar, J.W.; van Santen, H.M. Differences in checkpoint-inhibitor-induced hypophysitis: Mono- versus combination therapy induced hypophysitis. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1400841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Dalmazi, G.; Ippolito, S.; Lupi, I.; Caturegli, P. Hypophysitis induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: A 10-year assessment. Expert. Rev. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 14, 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Shah, K.; Waguespack, S.G.; Hu, M.I.; Habra, M.A.; Cabanillas, M.E.; Busaidy, N.L.; Bassett, R.; Zhou, S.; Iyer, P.C.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor related hypophysitis: Diagnostic criteria and recovery patterns. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2021, 28, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshafie, O.; Khalil, A.B.; Salman, B.; Atabani, A.; Al-Sayegh, H. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors-Induced Endocrinopathies: Assessment, Management and Monitoring in a Comprehensive Cancer Centre. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2024, 7, e00505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, H.; Cho, Y.K.; Go, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Koh, E.H. Patterns of hormonal changes in hypophysitis by immune checkpoint inhibitor. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, C.E.; Olsson-Brown, A.; Carroll, P.; Cooksley, T.; Larkin, J.; Lorigan, P.; Morganstein, D.; Trainer, P.J. Society for endocrinology endocrine emergency guidance: Acute management of the endocrine complications of checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Endocr. Connect. 2018, 7, G1–G7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.J.; Powers, A.C.; Johnson, D.B. Endocrine Toxicities of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, L.; Hodi, F.S.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Ott, P.A.; Luke, J.J.; Donahue, H.; Davis, M.; Carroll, R.S.; Kaiser, U.B. Systemic high-dose corticosteroid treatment does not improve the outcome of ipilimumab-related hypophysitis: A retrospective cohort study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Grace, J.; Dineen, R.; Sherlock, M.; Thompson, C.J. Adrenal insufficiency: Physiology, clinical presentation and diagnostic challenges. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 505, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martella, S.; Lucas, M.; Porcu, M.; Perra, L.; Denaro, N.; Pretta, A.; Deias, G.; Willard-Gallo, K.; Parra, H.S.; Saba, L.; et al. Primary adrenal insufficiency induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors: Biological, clinical, and radiological aspects. Semin. Oncol. 2023, 50, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukier, P.; Santini, F.C.; Scaranti, M.; Hoff, A.O. Endocrine side effects of cancer immunotherapy. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2017, 24, T331–T347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grouthier, V.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Moey, M.; Johnson, D.B.; Moslehi, J.J.; Salem, J.E.; Bachelot, A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor--Associated Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: WHO VigiBase Report Analysis. Oncologist 2020, 25, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husebye, E.S.; Pearce, S.H.; Krone, N.P.; Kämpe, O. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet 2021, 397, 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helderman, N.C.; Lucas, M.W.; Blank, C.U. Autoantibodies involved in primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency following treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Immuno-Oncol. Technol. 2023, 17, 100374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzolla, G.; Coppelli, A.; Cosottini, M.; Del Prato, S.; Marcocci, C.; Lupi, I. Immune Checkpoint Blockade Anti–PD-L1 as a Trigger for Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndrome. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, A.; Thant, A.A.; Aslam, A.; Aung, P.P.M.; Azmi, S. Diagnosis and management of adrenal insufficiency. Clin. Med. 2024, 23, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, S.R.; Allolio, B.; Arlt, W.; Barthel, A.; Don-Wauchope, A.; Hammer, G.D.; Husebye, E.S.; Merke, D.P.; Murad, M.H.; Stratakis, C.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 101, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and adrenal insufficiency: A large-sample case series study. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitrache, M.L.; Reghina, A.D.; Stoian, I.S.; Fica, S. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Diabetes Mellitus-A Brief Review and Three Case Reports. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baden, M.Y.; Imagawa, A.; Abiru, N.; Awata, T.; Ikegami, H.; Uchigata, Y.; Oikawa, Y.; Osawa, H.; Kajio, H.; Kawasaki, E.; et al. Characteristics and clinical course of type 1 diabetes mellitus related to anti-programmed cell death-1 therapy. Diabetol. Int. 2019, 10, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, V.H.M.; McGrath, R.T.; Clifton-Bligh, R.J.; Scolyer, R.A.; Jakrot, V.; yama Guminski, A.D.; Long, G.V.; Menzies, A.M. Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Autoimmune Diabetes Is Distinct from Type 1 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 5499–5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kani, E.R.; Karaviti, E.; Karaviti, D.; Gerontiti, E.; Paschou, I.A.; Saltiki, K.; Stefanaki, K.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Paschou, S.A. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced diabetes mellitus. Endocrine 2025, 87, 875–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, Z.; Perdigoto, A.; Anderson, M.S.; Herold, K.C. Checkpoint Inhibitor-Induced Autoimmune Diabetes: An Autoinflammatory Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2025, 15, a041603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.J.; Salem, J.E.; Johnson, D.B.; Lebrun-Vignes, B.; Stamatouli, A.; Thomas, J.W.; Herold, K.C.; Moslehi, J.; Powers, A.C. Increased reporting of immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated diabetes. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, e150–e151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwal, A.; Haddox, C.; Block, M.; Kudva, Y.C. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: An emerging cause of insulin-dependent diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2019, 7, e000591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akturk, H.K.; Kahramangil, D.; Sarwal, A.; Hoffecker, L.; Murad, M.H.; Michels, A.W. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced Type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet. Med. 2019, 36, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.J.I.; Salama, A.D.; Chitnis, T.; Smith, R.N.; Yagita, H.; Akiba, H.; Yamazaki, T.; Azuma, M.; Iwai, H.; Khoury, S.J.; et al. The programmed death-1 (PD-1) pathway regulates autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quandt, Z.; Young, A.; Anderson, M. Immune checkpoint inhibitor diabetes mellitus: A novel form of autoimmune diabetes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2020, 200, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourad, D.; Azar, N.S.; Eid, A.A.; Azar, S.T. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced diabetes mellitus: Potential role of t cells in the underlying mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluestone, J.A.; Anderson, M.; Herold, K.C.; Stamatouli, A.M.; Quandt, Z.; Perdigoto, A.L.; Clark, P.L.; Kluger, H.; Weiss, S.A.; Gettinger, S.; et al. Collateral damage: Insulin-dependent diabetes induced with checkpoint inhibitors. Diabetes 2018, 67, 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filette, J.M.K.; Pen, J.J.; Decoster, L.; Vissers, T.; Bravenboer, B.; Van Der Auwera, B.J.; Gorus, F.K.; Roep, B.O.; Aspeslagh, S.; Neyns, B.; et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and type 1 diabetes mellitus: A case report and systematic review. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 181, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Tsang, V.; Menzies, A.M.; Sasson, S.C.; Carlino, M.S.; Brown, D.A.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; Gunton, J.E. Risk Factors and Characteristics of Checkpoint Inhibitor–Associated Autoimmune Diabetes Mellitus (CIADM): A Systematic Review and Delineation From Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clotman, K.; Janssens, K.; Specenier, P.; Weets, I.; De Block, C.E.M. Programmed Cell Death-1 Inhibitor-Induced Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3144–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Sharma, R.; Hamad, L.; Riebandt, G.; Attwood, K. Incidence of diabetes mellitus in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) therapy—A comprehensive cancer center experience. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 202, 110776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatayama, S.; Kodama, S.; Kawana, Y.; Otake, S.; Sato, D.; Horiuchi, T.; Takahashi, K.; Kaneko, K.; Imai, J.; Katagiri, H. Two cases with fulminant type 1 diabetes that developed long after cessation of immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. J. Diabetes Investig. 2022, 13, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.K.; Jung, C.H. Immune-Checkpoint Inhibitors-Induced Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: From Its Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Practice. Diabetes Metab. J. 2023, 47, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imagawa, A.; Hanafusa, T.; Awata, T.; Ikegami, H.; Uchigata, Y.; Osawa, H.; Kawasaki, E.; Kawabata, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Shimada, A.; et al. Report of the Committee of the Japan Diabetes Society on the Research of Fulminant and Acute-onset Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: New diagnostic criteria of fulminant type 1 diabetes mellitus (2012). J. Diabetes Investig. 2012, 3, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Xue, C.; Wan, R. A comprehensive review of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related diabetes mellitus: Incidence, clinical features, management, and prognosis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1448728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Abu-Sbeih, H.; Ascierto, P.A.; Brufsky, J.; Cappelli, L.C.; Cortazar, F.B.; Gerber, D.E.; Hamad, L.; Hansen, E.; Johnson, D.B.; et al. Society for immunotherapy of cancer (sitc) clinical practice guideline on immune checkpoint inhibitor-related adverse events. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Liu, C.; Chen, S.; Liu, F.; Li, W.; Shangguan, D.; Yinguri, S. Recent advances in immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 122, 110414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Tsang, V.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; Carlino, M.S.; Tse, T.; Huang, Y.; Oatley, M.; Cheung, N.W.; Long, G.V.; Menzies, A.M.; et al. Hyperglycemia in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: Key clinical challenges and multidisciplinary consensus recommendations. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Takeda, K.; Yoshino, T.; Bando, H.; Arita, K.; Ishii, N.; Takahashi, S. Infection risk with PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway inhibitors and immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced solid tumours in phase I clinical trials. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, T.; Fujita, K.; Redelman-Sidi, G.; Elkington, P.T. Infections due to dysregulated immunity: An emerging complication of cancer immunotherapy. Thorax 2022, 77, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, M.; Karniadakis, I.; Mazonakis, N.; Akinosoglou, K.; Tsioutis, C.; Spernovasilis, N. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Infection: What Is the Interplay? Vivo 2023, 37, 2409–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudiol, C.; Hicklen, R.S.; Okhuysen, P.C.; Malek, A.E.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Infections Simulating Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Toxicities: Uncommon and Deceptive. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2022, 9, ofac570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, J.A.; Baddley, J.W. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients receiving tumor-necrosis-factor-inhibitor therapy: Implications for chemoprophylaxis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014, 16(10), 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, F.; Morelli, A.M.; Luciani, A.; Ghidini, A.; Solinas, C. Risk of Infection with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Target Oncol. 2021, 16, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchi, H.; Cavalcanti, G.P.; Orcurto, A.S.S.F.; Freire, M.S.; Tardomi, N.S.C.; Costa, D.S.M.G.L.F.; Barros, S.V.M.; Silva, M.N.S.; Reis, V.M.A.P. Infectious complications associated with the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in oncology: Reactivation of tuberculosis after anti PD-1 treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redelman-Sidi, G.; Michielin, O.; Cervera, C.; Ribi, C.; Aguado, J.M.; Fernandez Ruiz, M.; Manuel, O. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) Consensus Document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: An infectious diseases perspective (Immune checkpoint inhibitors, cell adhesion inhibitors, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulators and proteasome inhibitors). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, S95–S107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Del Castillo, M.; Romero, F.A.; Argüello, E.; Kyi, C.; Postow, M.A.; Redelman-Sidi, G. The Spectrum of Serious Infections Among Patients Receiving Immune Checkpoint Blockade for the Treatment of Melanoma. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 1490–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázár-Molnár, E.; Chen, B.; Sweeney, K.A.; Wang, E.J.; Liu, W.; Lin, J.; Porcelli, S.A.; Almo, S.C.; Nathenson, S.G.; Jacobs Jr, W.R. Programmed death-1 (PD-1)–deficient mice are extraordinarily sensitive to tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 13402–13407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Kim, Y.H.; Kanai, O.; Yoshida, H.; Mio, T.; Hirai, T. Emerging concerns of infectious diseases in lung cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Respir. Med. 2019, 146, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, B.; Fritz, J.M.; Su, H.C.; Uzel, G.; Jordan, M.B.; Lenardo, M.J. CHAI and LATAIE: New genetic diseases of CTLA-4 checkpoint insufficiency. Blood 2016, 128, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gámez-Díaz, L.; August, D.; Stepensky, P.; Revel-Vil, S.; Seidel, M.G.; Noriko, M.; Moiro, T.; Worth, A.J.J.; Blessing, J.; Van de Veerdonk, F.; et al. The extended phenotype of LPS-responsive beige-like anchor protein (LRBA) deficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 137, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abers, M.S.; Lionakis, M.S. Infectious Complications of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 34, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, E.A.; Graetz, V.; Allerheiligen, J.; Zillikens, D.; Rupp, J.; Terheyden, P. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and tuberculosis: An old disease in a new context. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, e55–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Fang, W.; Cai, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, W.; Lin, Z.; et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients with positive Hepatitis B surface antigen undergoing PD-1 inhibition. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babacan, N.A.; Tanvetyanon, T. Superimposed Clostridium difficile Infection During Checkpoint Inhibitor Immunotherapy-induced Colitis. J. Immunother. 2019, 42, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picasso, R.; Cozzi, A.; Picasso, V.; Zaottini, F.; Pistoia, F.; Perissi, S.; Martinoli, C. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related pneumonitis and COVID-19: A case-matched comparison of CT findings. Radiol. Med. 2023, 128, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyi, C.; Hellmann, M.D.; Wolchok, J.D.; Chapman, P.B.; Postow, M.A. Opportunistic infections in patients treated with immunotherapy for cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2014, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagna, A.; Arlunno, B.; Imarisio, I. A case report of pulmonary nocardiosis during pembrolizumab: The emerging challenge of the infections on immunotherapy. Immunotherapy 2022, 14, 1369–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartermain, L.; Buchan, C.A.; Kilabuk, E.; Wheatley-Price, P. Pulmonary Nocardiosis in a Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patient Being Treated for Pembrolizumab-Associated Pneumonitis. Case Rep. Oncol. 2024, 17, 1222–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Park, S.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Lee, K.; Choi, S. Reactivation of Varicella-Zoster Virus in Patients with Lung Cancer Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Retrospective Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study from South Korea. Cancers 2024, 16, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Park, S.Y.; Jo, H.B.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, D.; Lee, K.; Choi, S. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with lung cancer receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors: A retrospective nationwide population-based cohort study from South Korea. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Komoda, K.; Pal, S.; Dickter, J.; Salgia, R.; Dadwal, S. Infectious complications of immune checkpoint inhibitors in solid organ malignancies. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.P.; Correia, L.B.; da Silva, J.B.; de Melo, A.C. The Safety of Immunosuppressants Used in the Treatment of Immune-Related Adverse Events due to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 2956–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, C.; Rooms, I.; Fiedler, M.; Reis, H.; Milsch, L.; Herz, S.; Livingston, E.; Zimmer, L.; Schmid, K.W.; Dittmer, U.; et al. Cytomegalovirus reactivation in patients with refractory checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 86, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, N.; Fujita, K.; Nakatani, K.; Mio, T. Acute Progression of Aspergillosis in a Patient with Lung Cancer Receiving Nivolumab. Respirol. Case Rep. 2017, 6, e00289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rivero, J.; Cordes, L.M.; Klubo-Gwiezdzinska, J.; Madan, R.A.; Nieman, L.K.; Gulley, J.L. Endocrine-Related Adverse Events Related to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Proposed Algorithms for Management. Oncologist 2020, 25, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.K.; Wang, J.H.; Kao, S.L. Risk of developing pneumonia associated with clinically diagnosed hypothyroidism: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Fam. Pract. 2021, 38, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorkildsen, M.S.; Mohus, R.M.; Åsvold, B.O.; Skei, N.V.; Nilsen, T.I.L.; Solligård, E.; Damas, J.K.; Gustad, L.T. Thyroid function and risk of bloodstream infections: Results from the Norwegian prospective population-based HUNT Study. Clin. Endocrinol. 2022, 96, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, T.L.; Rajeswaran, H.; Haddad, S.; Shahi, A.; Parvizi, J. Increased Risk of Periprosthetic Joint Infections in Patients With Hypothyroidism Undergoing Total Joint Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplast. 2016, 31, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngaosuwan, K.; Johnston, D.G.; Godsland, I.F.; Cox, J.; Majeed, A.; Quint, J.K.; Oliver, N.; Robinson, S. Increased Mortality Risk in Patients with Primary and Secondary Adrenal Insufficiency. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, E2759–E2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, F.; Widmer, A.; Wagner, U.; Mueller, B.; Schuetz, P.; Christ-Crain, M.; Kutz, A. Association of adrenal insufficiency with patient-oriented health-care outcomes in adult medical inpatients. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 181, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergthorsdottir, R.; Esposito, D.; Olsson, D.S.; Ragnarsson, O.; Dahlqvist, P.; Bensing, S.; Natman, J.; Johannsson, G.; Nyberg, F. Increased risk of hospitalization, intensive care and death due to COVID-19 in patients with adrenal insufficiency: A Swedish nationwide study. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 295, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, A.W.M.; Stienstra, R.; Jaeger, M.; van Gool, A.J.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Netea, M.G.; Riksen, N.P.; Tack, C.J. Understanding the increased risk of infections in diabetes: Innate and adaptive immune responses in type 1 diabetes. Metabolism 2021, 121, 154795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Liu, H.Q.; Nie, Q.; Wang, H.; Xiang, T. Causal relationship between type 1 diabetes mellitus and six high-frequency infectious diseases: A two-sample mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1135726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, L.M.A.J.; Gorter, K.J.; Hak, E.; Goudzwaard, W.L.; Schellevis, F.G.; Hoepelman, A.I.M.; Rutten, G.E.H.M. Increased risk of common infections in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critchley, J.A.; Carey, I.M.; Harris, T.; DeWilde, S.; Hosking, F.J.; Cook, D.G. Glycemic control and risk of infections among people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes in a large primary care cohort study. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro, C.; Farina, N.; Tomelleri, A.; Ferrara, R.; Lazzari, C.; De Luca, G.; Bulotta, A.; Signorelli, D.; Palmisano, A.; Vignale, D.; et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of immune-related adverse events: A systematic literature review and a multicentre case series. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 93, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.B.; Liu, D.Y.; Hu, R.; Zhou, Z.Z.; Meng, Y.; Li, H.L.; Huang, W.J.; Tian, X.P. Immune-related adverse events of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in patients with perioperative cancer: A machine-learning-driven, decade-long informatics investigation. J. Immunother. Cancer 2025, 13, e011040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year (Journal) | Study Design & Population | Endocrine Focus | Key Results/Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barroso-Sousa et al., 2018 (JAMA Oncol.) [35] | Systematic review & meta-analysis; 38 clinical trials | All endocrine irAEs | Incidence highest with combination therapy; thyroid dysfunction most common, followed by hypophysitis and adrenal insufficiency. |

| De Filette et al., 2019 (Horm. Metab. Res.) [30] | Systematic review & meta-analysis | Endocrine irAEs overall | Higher risk of thyroid dysfunction with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors; hypophysitis strongly associated with CTLA-4 inhibitors. |

| Min et al., 2015 (Clin. Cancer Res.) [48] | Retrospective cohort; ipilimumab-treated patients | Hypophysitis | High-dose corticosteroids did not improve pituitary recovery; most patients required lifelong hormone replacement. |

| Di Dalmazi et al., 2019 (Expert. Rev. Endocrinol. Metab.) [42] | 10-year assessment review | Hypophysitis | Median onset 2–4 months; CTLA-4 inhibitors major driver; secondary adrenal insufficiency often permanent. |

| Cui et al., 2022 (Ann. Transl. Med.) [58] | Large-sample case series | Adrenal insufficiency | Highlighted clinical features and frequency of adrenal insufficiency with ICIs; PD-1/PD-L1 > CTLA-4. |

| Grouthier et al., 2020 (Oncologist) [52] | WHO VigiBase pharmacovigilance study | Primary adrenal insufficiency | Rare but potentially life-threatening; emphasized need for early recognition. |

| Akturk et al., 2019 (Diabet. Med.) [66] | Systematic review & meta-analysis; 71 cases | ICI-induced T1DM | Incidence 0.2–1.9%; often acute onset, presenting with DKA; mostly with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. |

| Wu et al., 2023 (Diabetes Care) [72] | Systematic review; 192 cases | Checkpoint inhibitor–associated DM | Distinct phenotype from classic T1DM; abrupt presentation, low antibody positivity, severe hyperglycemia. |

| Baden et al., 2019 (Diabetol. Int.) [60] | Multicenter cohort; Japan | Anti-PD-1 therapy diabetes | Characterized rapid-onset ICI-DM; high rates of ketoacidosis. |

| Tsang et al., 2019 (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.) [61] | Clinical cohort | ICI-associated autoimmune diabetes | Distinct course vs. T1DM; often antibody-negative, aggressive course. |

| Yamauchi I., Yabe D., 2025 (Eur. Thyroid. J.) [28] | Clinical review | Thyroid dysfunction | ICI-thyroid dysfunction frequent; PD-1/PD-L1 linked to hypothyroidism, CTLA-4 to thyroiditis. |

| Chalan et al., 2018 (J. Endocrinol. Investig.) [29] | Narrative review | Thyroid dysfunction | Thyroiditis followed by hypothyroidism common; permanent dysfunction in many cases. |

| Predisposing Event | Potential Mechanism | Potential Pathogens/Infections | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection risk from ICI therapy alone | Direct immune dysregulation by ICIs | Loss of checkpoint control, T-cell hyperactivation, IRIS-like phenomena | Mycobacterium tuberculosis (new or reactivation); Fungal infections (Candida spp., Aspergillus spp.); Viral reactivations (HIV IRIS, CMV colitis/gastritis, VZV CNS disease, HSV family viruses); HBV reactivation; SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19, differential with ICI-pneumonitis); Clostridioides difficile (CDAD, even without antibiotics) |

| Genetic predisposition | CTLA-4 haploinsufficiency, LRBA deficiency, impaired Treg function | Recurrent respiratory & urinary tract infections: Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Campylobacter spp., Staphylococcus aureus; Viral: CMV, adenovirus, norovirus, VZV; Fungal: Candida spp. | |

| ICI-related cytopenia | Leukopenia/lymphopenia observed with pembrolizumab, nivolumab | General increased risk of bacterial (respiratory, urinary tract) infections, viral reactivations, opportunistic fungi |

| Predisposing Event | Potential Mechanism | Potential Pathogens/Infections | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infections associated with immunosuppressive treatment of irAEs | Corticosteroids, TNF-α inhibitors (e.g., infliximab) therapy | Immunosuppression | Bacterial: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus (pneumonia, bloodstream, intra-abdominal, urinary tract, SSTI); Viral: Influenza, CMV hepatitis/colitis; Fungal: Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, invasive aspergillosis |

| Endocrine dysfunction as a risk factor for infections | Thyroid disorders | Hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, thyroiditis | Increased risk of pneumonia, bloodstream infections, localized infections (e.g., periprosthetic joint infection); broad bacterial spectrum |

| Hypophysitis with adrenal insufficiency | Low cortisol → impaired immune function | Severe bacterial and viral infections (incl. higher COVID-19 mortality); sepsis, hospitalization, infection-related mortality | |

| ICI-induced diabetes mellitus | Hyperglycemia, immune dysfunction, abrupt glycemic fluctuations | Bacterial: respiratory, urinary tract, skin/soft tissue; Staphylococcus aureus; Mycobacterial: Mycobacterium tuberculosis; Fungal: Candida albicans; Risk amplified with poor glycemic control |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schönberger, E.; Švitek, L.; Grubišić, B.; Cvijić Perić, T.; Marušić, R.; Vlahović Vlašić, N.; Kizivat, T.; Canecki Varžić, S.; Stemberger Marić, L.; Bilić Ćurčić, I. Beyond Tumor Immunity: The Disruption of Endocrine and Infectious Homeostasis by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11619. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311619

Schönberger E, Švitek L, Grubišić B, Cvijić Perić T, Marušić R, Vlahović Vlašić N, Kizivat T, Canecki Varžić S, Stemberger Marić L, Bilić Ćurčić I. Beyond Tumor Immunity: The Disruption of Endocrine and Infectious Homeostasis by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11619. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311619

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchönberger, Ema, Luka Švitek, Barbara Grubišić, Tara Cvijić Perić, Romana Marušić, Nika Vlahović Vlašić, Tomislav Kizivat, Silvija Canecki Varžić, Lorna Stemberger Marić, and Ines Bilić Ćurčić. 2025. "Beyond Tumor Immunity: The Disruption of Endocrine and Infectious Homeostasis by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11619. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311619

APA StyleSchönberger, E., Švitek, L., Grubišić, B., Cvijić Perić, T., Marušić, R., Vlahović Vlašić, N., Kizivat, T., Canecki Varžić, S., Stemberger Marić, L., & Bilić Ćurčić, I. (2025). Beyond Tumor Immunity: The Disruption of Endocrine and Infectious Homeostasis by Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11619. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311619