Amphiphilic Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) Biocomposites with Bortezomib and DR5-Selective TRAIL Variants: A Promising Approach to Pancreatic Cancer Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

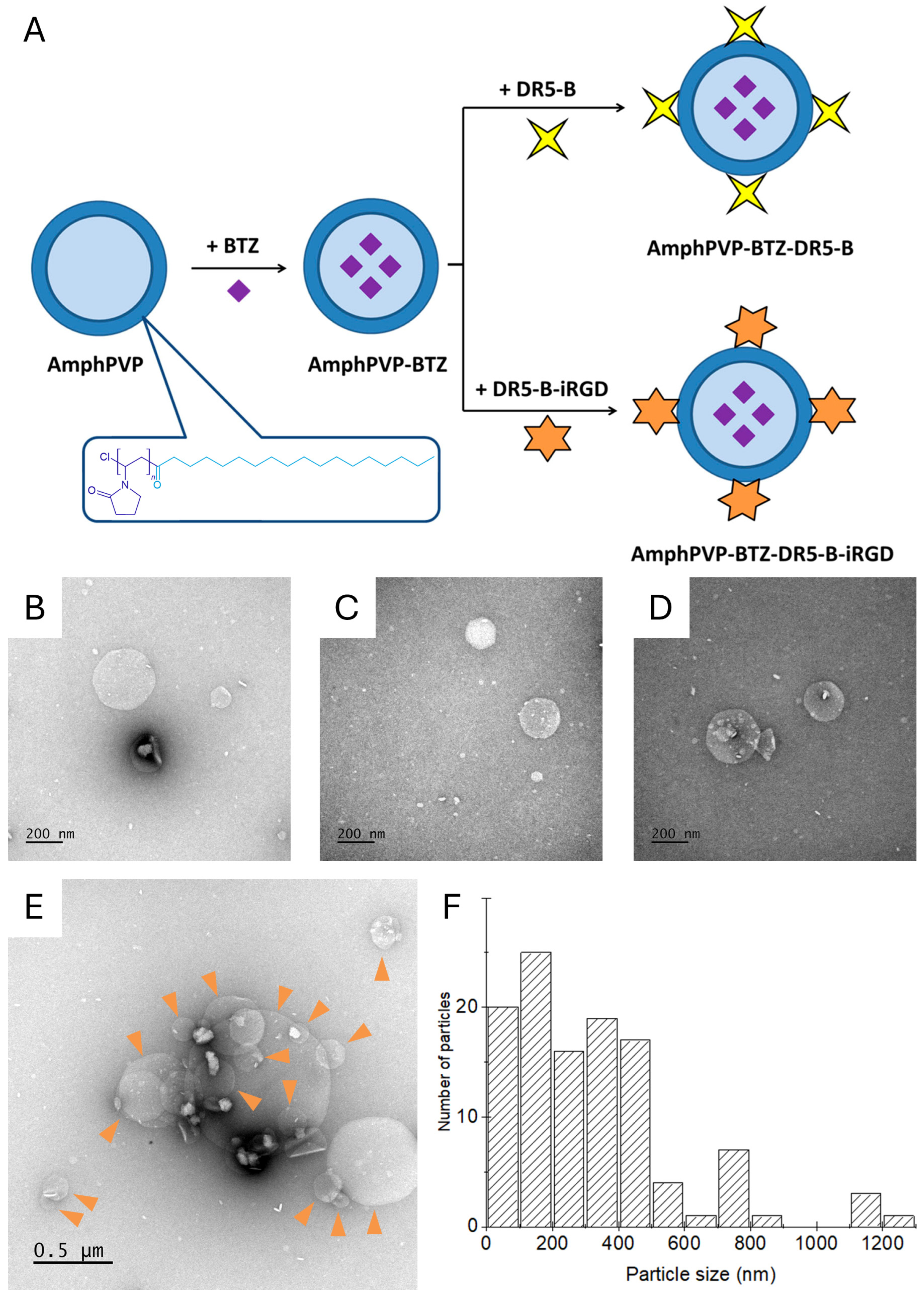

2.1. Fabrication and Characterization of the Biocomposites AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B and AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B-iRGD

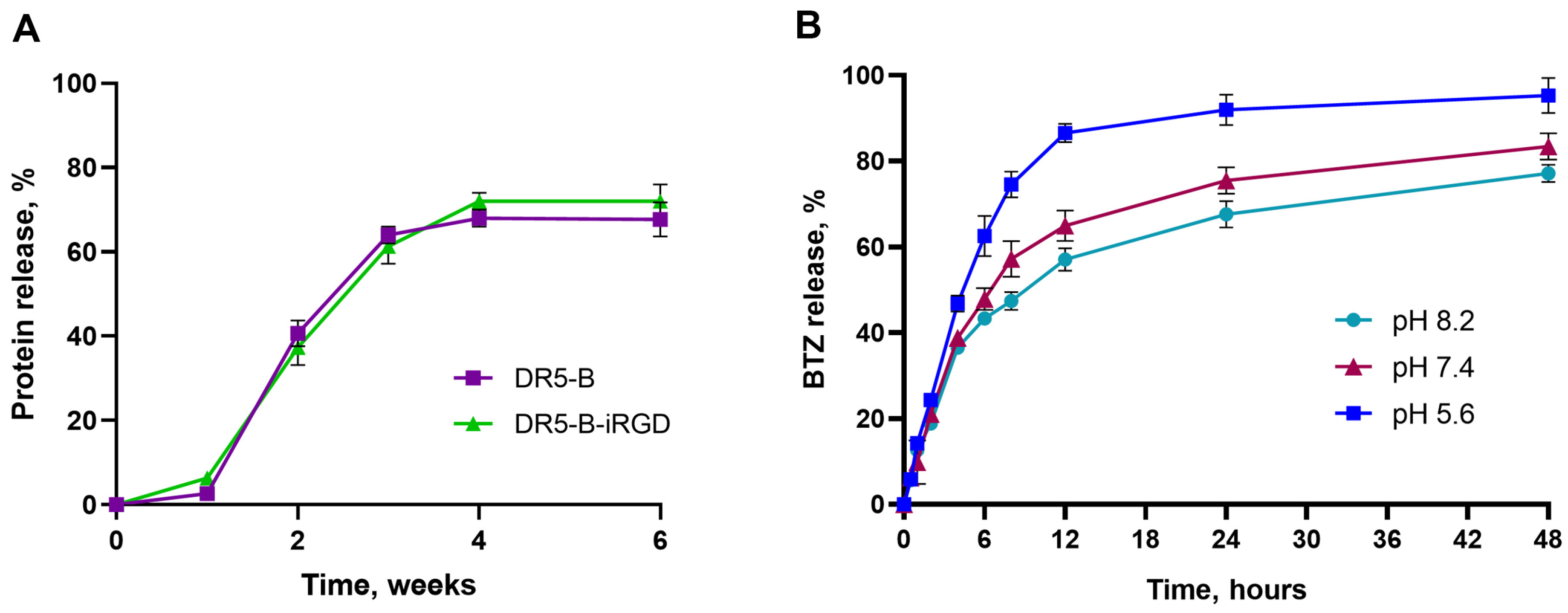

2.2. In Vitro Release of Either DR5-B or DR5-B-iRGD and BTZ from the Biocomposites

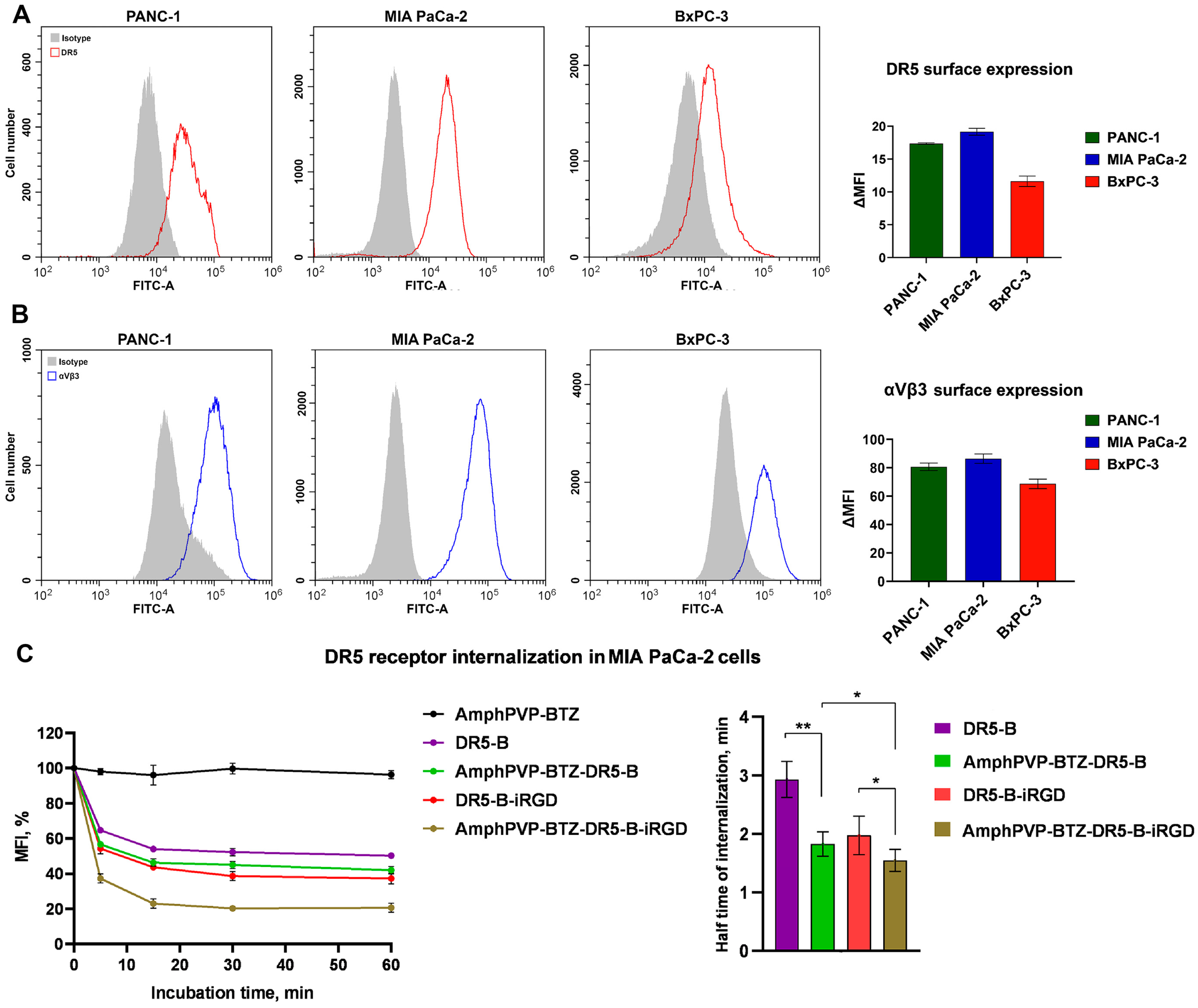

2.3. Assessment of the Cytotoxic Activity of AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B and AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B-iRGD Biocomposites in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines

2.4. DR5 Receptor Internalization by Biocomposites

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Expression and Purification of TRAIL DR5-B and DR5-B-iRGD

4.3. Fabrication Nanoparticles AmphPVP-BTZ

4.4. Fabrication Nanocomposites AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B and AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B-iRGD

4.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

4.6. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

4.7. In Vitro Drug Release Study

4.8. Cell Lines

4.9. Cytotoxicity Assay

4.10. Western Blotting

4.11. Internalization of the DR5 Receptor by Flow Cytometry

4.12. Surface Expression of the DR5 Receptor by Flow Cytometry

4.13. Study of Mechanism of Cell Death

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BTZ | Bortezomib |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s Medium |

| DMSO | Dimethylsulfoxide |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| IT | Intratumoral |

References

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Gaduputi, V. Epidemiology of Pancreatic Cancer: Global Trends, Etiology and Risk Factors. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lin, C.; Wang, W. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Pancreatic Cancer from 1990 to 2021, Its Attributable Risk Factors, and Projections to 2050: A Systematic Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleeff, J.; Korc, M.; Apte, M.; La Vecchia, C.; Johnson, C.D.; Biankin, A.V.; Neale, R.E.; Tempero, M.; Tuveson, D.A.; Hruban, R.H.; et al. Pancreatic Cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivani, G.; Peela, S.; Alam, A.; Nagaraju, G.P. Gemcitabine for Pancreatic Cancer Therapy. CP 2024, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogbein, O.; Paul, P.; Umar, M.; Chaari, A.; Batuman, V.; Upadhyay, R. Bortezomib in Cancer Therapy: Mechanisms, Side Effects, and Future Proteasome Inhibitors. Life Sci. 2024, 358, 123125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagut, C.; Rovira, A.; Gascon, P.; Ross, J.S.; Albanell, J. Preclinical and Clinical Development of the Proteasome Inhibitorbortezomib in Cancer Treatment. Drugs Today 2005, 41, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuphanich, S.; Supko, J.G.; Carson, K.A.; Grossman, S.A.; Burt Nabors, L.; Mikkelsen, T.; Lesser, G.; Rosenfeld, S.; Desideri, S.; Olson, J.J. Phase 1 Clinical Trial of Bortezomib in Adults with Recurrent Malignant Glioma. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2010, 100, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki, S.T.; Carew, J.S.; Pino, M.S.; Highshaw, R.A.; Dunner, K.; Huang, P.; Abbruzzese, J.L.; McConkey, D.J. Bortezomib Sensitizes Pancreatic Cancer Cells to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 11658–11666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, B.H.Y.; Huang, D.-C.; Sinicrope, F.A. PS-341 (Bortezomib) Induces Lysosomal Cathepsin B Release and a Caspase-2-Dependent Mitochondrial Permeabilization and Apoptosis in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 11923–11932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasco, R.; Alberti, P.; Bruna, J.; Psimaras, D.; Argyriou, A.A. Bortezomib and Other Proteosome Inhibitors—Induced Peripheral Neurotoxicity: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. J. Peripheral Nervous Sys. 2019, 24, S52–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahleda, R.; Le Deley, M.-C.; Bernard, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Hanley, M.; Poterie, A.; Gazzah, A.; Varga, A.; Touat, M.; Deutsch, E.; et al. Phase I Trial of Bortezomib Daily Dose: Safety, Pharmacokinetic Profile, Biological Effects and Early Clinical Evaluation in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Investig. New Drugs 2018, 36, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, R.; Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, B. Progress on the Application of Bortezomib and Bortezomib-Based Nanoformulations. Biomolecules 2021, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudian, M.; Valizadeh, H.; Zakeri-Milani, P. Bortezomib-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles: Preparation, Characterization, and Intestinal Permeability Investigation. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2018, 44, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, T.; Dong, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, D.; Tong, H.; Ji, X.; Sun, B.; Zhu, M.; Jiang, X. Novel Block Glycopolymers Prepared as Delivery Nanocarriers for Controlled Release of Bortezomib. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 2018, 296, 1827–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xu, H.; Man, J.; Wang, G. Bortezomib-Encapsulated Metal–Phenolic Nanoparticles for Intracellular Drug Delivery. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 26176–26182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Wang, X.; Cheng, R.; Cheng, L.; Zhong, Z. Hyaluronic Acid Shell and Disulfide-Crosslinked Core Micelles for in Vivo Targeted Delivery of Bortezomib for the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Acta Biomater. 2018, 80, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiradharma, N.; Zhang, Y.; Venkataraman, S.; Hedrick, J.L.; Yang, Y.Y. Self-Assembled Polymer Nanostructures for Delivery of Anticancer Therapeutics. Nano Today 2009, 4, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.L.; Lavasanifar, A.; Kwon, G.S. Amphiphilic Block Copolymers for Drug Delivery. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 92, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuperkar, K.; Patel, D.; Atanase, L.I.; Bahadur, P. Amphiphilic Block Copolymers: Their Structures, and Self-Assembly to Polymeric Micelles and Polymersomes as Drug Delivery Vehicles. Polymers 2022, 14, 4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Lu, S.; Sun, T.; Xi, G.; Chen, Z.; Xu, K.; Zhao, X.; Shen, M.; Jia, T.; Zhao, X. Robust Fluorescent Amphiphilic Polymer Micelle for Drug Carrier Application. N. J. Chem. 2021, 45, 9409–9415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabadi, A.; Hasannia, M.; Vakili-Azghandi, M.; Araste, F.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M. Synthesis Approaches of Amphiphilic Copolymers for Spherical Micelle Preparation: Application in Drug Delivery. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 9325–9368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Yang, Y.; Bergfel, A.; Huang, L.; Zheng, L.; Bowden, T.M. Self-Assembly of Cholesterol End-Capped Polymer Micelles for Controlled Drug Delivery. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, D.S.; Roy, A.; Pandit, S.; Alghamdi, S.; Almehmadi, M.; Alsaiari, A.A.; Abdulaziz, O.; Alsharif, A.; Khandaker, M.U.; Faruque, M.R.I. Polymer-Based Nanocarriers for Biomedical and Environmental Applications. e-Polymers 2023, 23, 20230049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabasz, A.; Bzowska, M.; Szczepanowicz, K. Biomedical Applications of Multifunctional Polymeric Nanocarriers: A Review of Current Literature. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 8673–8696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, A.; Carreiró, F.; Oliveira, A.M.; Neves, A.; Pires, B.; Venkatesh, D.N.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Eder, P.; Silva, A.M.; et al. Polymeric Nanoparticles: Production, Characterization, Toxicology and Ecotoxicology. Molecules 2020, 25, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuskov, A.N.; Shtilman, M.I.; Goryachaya, A.V.; Tashmuhamedov, R.I.; Yaroslavov, A.A.; Torchilin, V.P.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Rizos, A.K. Self-Assembling Nanoscaled Drug Delivery Systems Composed of Amphiphilic Poly-N-Vinylpyrrolidones. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2007, 353, 3969–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuskov, A.N.; Villemson, A.L.; Shtilman, M.I.; Larionova, N.I.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Tsikalas, I.; Rizos, A.K. Amphiphilic Poly-N-Vinylpyrrolidone Nanocarriers with Incorporated Model Proteins. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2007, 19, 205139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuskov, A.N.; Voskresenskay, A.A.; Goryachaya, A.V.; Shtilman, M.I.; Spandidos, D.A.; Rizos, A.K.; Tsatsakis, A.M. Amphiphilic Poly-N-Vinylpyrrolidone Nanoparticles as Carriers for Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: Characterization and in Vitro Controlled Release of Indomethacin. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2010, 26, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villemson, A.L.; Kuskov, A.N.; Shtilman, M.I.; Galebskaya, L.V.; Ryumina, E.V.; Larionova, N.I. Interaction of Polymer Aggregates Based on Stearoyl-Poly-N-Vinylpyrrolidone with Blood Components. Biochemistry 2004, 69, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamskov, I.A.; Kuskov, A.N.; Babievsky, K.K.; Berezin, B.B.; Krayukhina, M.A.; Samoylova, N.A.; Tikhonov, V.E.; Shtilman, M.I. Novel Liposomal Forms of Antifungal Antibiotics Modified by Amphiphilic Polymers. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2008, 44, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Na, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, P. Different Targeting Ligands-Mediated Drug Delivery Systems for Tumor Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, M.A.; Ragab, M.S.; Mahdy, F.Y.; Elsebaie, M.S.; Saber, A.M.; AbdElmalak, Y.O.; Elsafoury, R.H.; Elatreby, A.A.; Rochdi, A.M.; El-Basyouni, A.W.; et al. Folic Acid-Modified Chitosan Nanoparticles for Targeted Delivery of a Binuclear Co(II) Complex in Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 311, 144034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Ding, X.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Y.; Yang, Z.; Jin, J. EGFR-Targeted Humanized Single Chain Antibody Fragment Functionalized Silica Nanoparticles for Precision Therapy of Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidy, R.; Haider, A.J.; Al-Musawi, S.; Arsad, N. Targeted Delivery of Paclitaxel Drug Using Polymer-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles for Fibrosarcoma Therapy: In Vitro and in Vivo Studies. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh Zeinabad, H.; Szegezdi, E. TRAIL in the Treatment of Cancer: From Soluble Cytokine to Nanosystems. Cancers 2022, 14, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparian, M.E.; Chernyak, B.V.; Dolgikh, D.A.; Yagolovich, A.V.; Popova, E.N.; Sycheva, A.M.; Moshkovskii, S.A.; Kirpichnikov, M.P. Generation of New TRAIL Mutants DR5-A and DR5-B with Improved Selectivity to Death Receptor 5. Apoptosis 2009, 14, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagolovich, A.; Isakova, A.; Artykov, A.; Vorontsova, Y.; Mazur, D.; Antipova, N.; Pavlyukov, M.; Shakhparonov, M.; Gileva, A.; Markvicheva, E.; et al. DR5-Selective TRAIL Variant DR5-B Functionalized with Tumor-Penetrating iRGD Peptide for Enhanced Antitumor Activity against Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Peng, X.; Zoulikha, M.; Boafo, G.F.; Magar, K.T.; Ju, Y.; He, W. Multifunctional Nanoparticle-Mediated Combining Therapy for Human Diseases. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bostami, R.D.; Abuwatfa, W.H.; Husseini, G.A. Recent Advances in Nanoparticle-Based Co-Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, X.; Lu, X.; Tian, J. Nanoparticle Drug Delivery Systems for Synergistic Delivery of Tumor Therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1111991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikov, P.P.; Kuskov, A.N.; Goryachaya, A.V.; Luss, A.N.; Shtil’man, M.I. Amphiphilic Poly-n-Vinyl-2-Pyrrolidone: Synthesis, Properties, Nanoparticles. Polym. Sci. Ser. D 2017, 10, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artyukhov, A.A.; Nechaeva, A.M.; Shtilman, M.I.; Chistyakov, E.M.; Svistunova, A.Y.; Bagrov, D.V.; Kuskov, A.N.; Docea, A.O.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Gurevich, L.; et al. Nanoaggregates of Biphilic Carboxyl-Containing Copolymers as Carriers for Ionically Bound Doxorubicin. Materials 2022, 15, 7136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagolovich, A.; Kuskov, A.; Kulikov, P.; Bagrov, D.; Petrova, P.; Kukovyakina, E.; Isakova, A.; Khan, I.; Pokrovsky, V.; Nosyrev, A.; et al. Assessment of the Effects of Amphiphilic Poly (N-vinylpyrrolidone) Nanoparticles Loaded with Bortezomib on Glioblastoma Cell Lines and Zebrafish Embryos. Biomed. Rep. 2024, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomaszewska, E.; Soliwoda, K.; Kadziola, K.; Tkacz-Szczesna, B.; Celichowski, G.; Cichomski, M.; Szmaja, W.; Grobelny, J. Detection Limits of DLS and UV-Vis Spectroscopy in Characterization of Polydisperse Nanoparticles Colloids. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 313081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artykov, A.A.; Yagolovich, A.V.; Dolgikh, D.A.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Trushina, D.B.; Gasparian, M.E. Death Receptors DR4 and DR5 Undergo Spontaneous and Ligand-Mediated Endocytosis and Recycling Regardless of the Sensitivity of Cancer Cells to TRAIL. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 733688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayanathara, U.; Kermaniyan, S.S.; Such, G.K. Multicompartment Polymeric Nanocarriers for Biomedical Applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2020, 41, 2000298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Hu, R.; Xiang, J.; Fu, S.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Tao, X.; et al. Preparation and Anti-Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cell Effect of a Nanoparticle for the Codelivery of Paclitaxel and Gemcitabine. Discov. Nano 2023, 18, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Huang, J.; Xiao, H.; Wu, T.; Shuai, X. Codelivery of Temozolomide and siRNA with Polymeric Nanocarrier for Effective Glioma Treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 3467–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kántor, I.; Dreavă, D.; Todea, A.; Péter, F.; May, Z.; Biró, E.; Babos, G.; Feczkó, T. Co-Entrapment of Sorafenib and Cisplatin Drugs and iRGD Tumour Homing Peptide by Poly[ε-Caprolactone-Co-(12-Hydroxystearate)] Copolymer. Biomedicines 2021, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Liang, C.; Shi, S.; Yu, X.; Chen, Q.; Sun, T.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Q.; et al. Codelivery Nanosystem Targeting the Deep Microenvironment of Pancreatic Cancer. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 3527–3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Mondal, G.; Slavik, P.; Rachagani, S.; Batra, S.K.; Mahato, R.I. Codelivery of Small Molecule Hedgehog Inhibitor and miRNA for Treating Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2015, 12, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitkara, D.; Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Danquah, M.; Behrman, S.W.; Kumar, N.; Mahato, R.I. Micellar Delivery of Cyclopamine and Gefitinib for Treating Pancreatic Cancer. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2012, 9, 2350–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Fan, X.; Fu, C.; Yang, J.; Tian, J.; Peng, Q.; Qin, W.; Wu, Y. Codelivery of Doxorubicin/PI3K Inhibitor Nanomicelle Linked with Phenylboronic Acid for Enhanced Cytotoxicity to Pancreatic Cancer. J. Nanomater. 2022, 2022, 8758356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, A.A.; Turgambayeva, A.; Kamalbekova, G.; Suleimenova, R.; Latypova, N.; Ospanova, S.; Ospanova, D.; Abdikadyr, Z.; Zhussupov, S. TRAIL as a Warrior in Nano-Sized Trojan Horse: Anticancer and Anti-Metastatic Effects of Nano-Formulations of TRAIL in Cell Culture and Animal Model Studies. Medicina 2024, 60, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.K.; Woo, S.M.; Seo, S.U.; Banstola, A.; Kim, H.; Duwa, R.; Vu, A.T.T.; Hong, I.-S.; Kwon, T.K.; Yook, S. Enhanced Anticancer Efficacy of TRAIL-Conjugated and Odanacatib-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles in TRAIL Resistant Cancer. Biomaterials 2025, 312, 122733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Zhou, D.; Li, W.; Duan, Y.; Xu, M.; Liu, J.; Cheng, J.; Xiao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Gan, T.; et al. Therapeutic Efficacy of a MMAE-Based Anti-DR5 Drug Conjugate Oba01 in Preclinical Models of Pancreatic Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Cao, Q.; Dudek, A.Z. Phase II Study of Panobinostat and Bortezomib in Patients with Pancreatic Cancer Progressing on Gemcitabine-Based Therapy. Anticancer. Res. 2012, 32, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farooqi, A.A.; Zahid, R.; Maryam, A.; Naureen, H.; Attar, R.; Sabitaliyevich, U.Y.; Konysbayevna, K.K. TRAIL Mediated Signaling as a Double-Edged Sword in Pancreatic Cancer: Analysis of Brighter and Darker Sides of the Pathway. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2020, 66, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, M.C.; Nicoll, J.A.; Redmond, K.M.; Smyth, P.; Greene, M.K.; McDaid, W.J.; Chan, D.K.W.; Crawford, N.; Stott, K.J.; Fox, J.P.; et al. DR5-Targeted, Chemotherapeutic Drug-Loaded Nanoparticles Induce Apoptosis and Tumor Regression in Pancreatic Cancer in Vivo Models. J. Control. Release 2020, 324, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitovic, D.; Kukovyakina, E.; Berdiaki, A.; Tzanakakis, A.; Luss, A.; Vlaskina, E.; Yagolovich, A.; Tsatsakis, A.; Kuskov, A. Enhancing Tumor Targeted Therapy: The Role of iRGD Peptide in Advanced Drug Delivery Systems. Cancers 2024, 16, 3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparian, M.E.; Bychkov, M.L.; Yagolovich, A.V.; Dolgikh, D.A.; Kirpichnikov, M.P. Mutations Enhancing Selectivity of Antitumor Cytokine TRAIL to DR5 Receptor Increase Its Cytotoxicity against Tumor Cells. Biochem. Mosc. 2015, 80, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Kuo, J.C.-T.; Huang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Deng, L.; Yung, B.C.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, J.; Ma, Y.; et al. Optimized Liposomal Delivery of Bortezomib for Advancing Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E.; Shen, H.; Ferrari, M. Principles of Nanoparticle Design for Overcoming Biological Barriers to Drug Delivery. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, D.; Joshi, N.; Tao, W.; Karp, J.M.; Peer, D. Progress and Challenges towards Targeted Delivery of Cancer Therapeutics. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Gabrielson, N.P.; Uckun, F.M.; Fan, T.M.; Cheng, J. Size-Dependent Tumor Penetration and in Vivo Efficacy of Monodisperse Drug–Silica Nanoconjugates. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 10, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greish, K. Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) Effect for Anticancer Nanomedicine Drug Targeting. In Cancer Nanotechnology; Grobmyer, S.R., Moudgil, B.M., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 624, pp. 25–37. ISBN 978-1-60761-608-5. [Google Scholar]

- De Miguel, D.; Lemke, J.; Anel, A.; Walczak, H.; Martinez-Lostao, L. Onto Better TRAILs for Cancer Treatment. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugge, S.E.; Scheper, R.J.; Lems, W.F.; De Gruijl, T.D.; Jansen, G. Proteasome Inhibitors as Experimental Therapeutics of Autoimmune Diseases. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.; Stellacci, F. Effect of Surface Properties on Nanoparticle–Cell Interactions. Small 2010, 6, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagolovich, A.V.; Artykov, A.A.; Dolgikh, D.A.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Gasparian, M.E. A New Efficient Method for Production of Recombinant Antitumor Cytokine TRAIL and Its Receptor-Selective Variant DR5-B. Biochem. Mosc. 2019, 84, 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Jain, S.K. In Vitro Release Kinetics Model Fitting of Liposomes: An Insight. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2016, 201, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siepmann, J.; Peppas, N.A. Higuchi Equation: Derivation, Applications, Use and Misuse. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 418, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruschi, K.L. Mathematical Models of Drug Release. In Strategies to Modify the Drug Release from Pharmaceutical Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 63–86. ISBN 978-0-08-100092-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, I.Y.; Bala, S.; Škalko-Basnet, N.; Di Cagno, M.P. Interpreting Non-Linear Drug Diffusion Data: Utilizing Korsmeyer-Peppas Model to Study Drug Release from Liposomes. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 138, 105026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunachalam, K.; Sreeja, P.S. MTT Assay Protocol. In Advanced Cell and Molecular Techniques; Springer Protocols Handbooks; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 271–276. ISBN 978-1-07-164517-8. [Google Scholar]

| Z-Average Size, (nm ± SD) | Zeta Potential, (mV ± SD) | PDI 1 | Sorption Capacity, µg Protein/mg AmphPVP-BTZ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AmphPVP | 180 ± 12 | −8.9 ± 2.1 | 0.16 | - |

| AmphPVP-BTZ | 300 ± 16 | −6.7 ± 1.6 | 0.23 | - |

| AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B | 680 ± 20 | −4.2 ± 2.6 | 0.48 | 5.0 ± 0.5 |

| AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B-iRGD | 684 ± 15 | −3.8 ± 2.9 | 0.52 | 4.5 ± 0.5 |

| Model/Parameter | pH 5.6 | pH 7.4 | pH 8.2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-Order (R2) | 0.837 | 0.876 | 0.894 |

| First-Order (R2) | 0.946 | 0.967 | 0.975 |

| Higuchi (R2) | 0.983 | 0.991 | 0.993 |

| Korsmeyer-Peppas | |||

| n (release exponent) | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.52 |

| K (rate constant, h−n) | 18.45 | 15.12 | 13.88 |

| R2 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.998 |

| IC50, nM | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PANC-1 | BxPC-3 | MIA PaCa-2 | |

| DR5-B | 2.35 ± 1.47 | 0.35 ± 0.11 | 0.17 ± 0.02 |

| DR5-B-iRGD | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| AmphPVP-BTZ | 35.03 ± 5.24 | 56.22 ± 5.09 | 34.01 ± 3.50 |

| AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B | 0.13 ± 0.03 * | 0.007 ± 0.001 * | 0.006 ± 0.001 * |

| AmphPVP-BTZ-DR5-B-iRGD | 0.059 ± 0.011 # | 0.003 ± 0.001 # | 0.001 ± 0.001 # |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kukovyakina, E.; Isakova, A.A.; Bagrov, D.; Gasparian, M.; Kuskov, A.; Yagolovich, A. Amphiphilic Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) Biocomposites with Bortezomib and DR5-Selective TRAIL Variants: A Promising Approach to Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311620

Kukovyakina E, Isakova AA, Bagrov D, Gasparian M, Kuskov A, Yagolovich A. Amphiphilic Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) Biocomposites with Bortezomib and DR5-Selective TRAIL Variants: A Promising Approach to Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311620

Chicago/Turabian StyleKukovyakina, Ekaterina, Alina A. Isakova, Dmitry Bagrov, Marine Gasparian, Andrey Kuskov, and Anne Yagolovich. 2025. "Amphiphilic Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) Biocomposites with Bortezomib and DR5-Selective TRAIL Variants: A Promising Approach to Pancreatic Cancer Treatment" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311620

APA StyleKukovyakina, E., Isakova, A. A., Bagrov, D., Gasparian, M., Kuskov, A., & Yagolovich, A. (2025). Amphiphilic Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) Biocomposites with Bortezomib and DR5-Selective TRAIL Variants: A Promising Approach to Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11620. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311620