The Phytochemical Potential of Viola Species, Melanium Subgenus, Subsection Bracteolatae

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Assimilatory Pigments

2.2. Anthocyanin Compounds

2.3. Phenolic Content

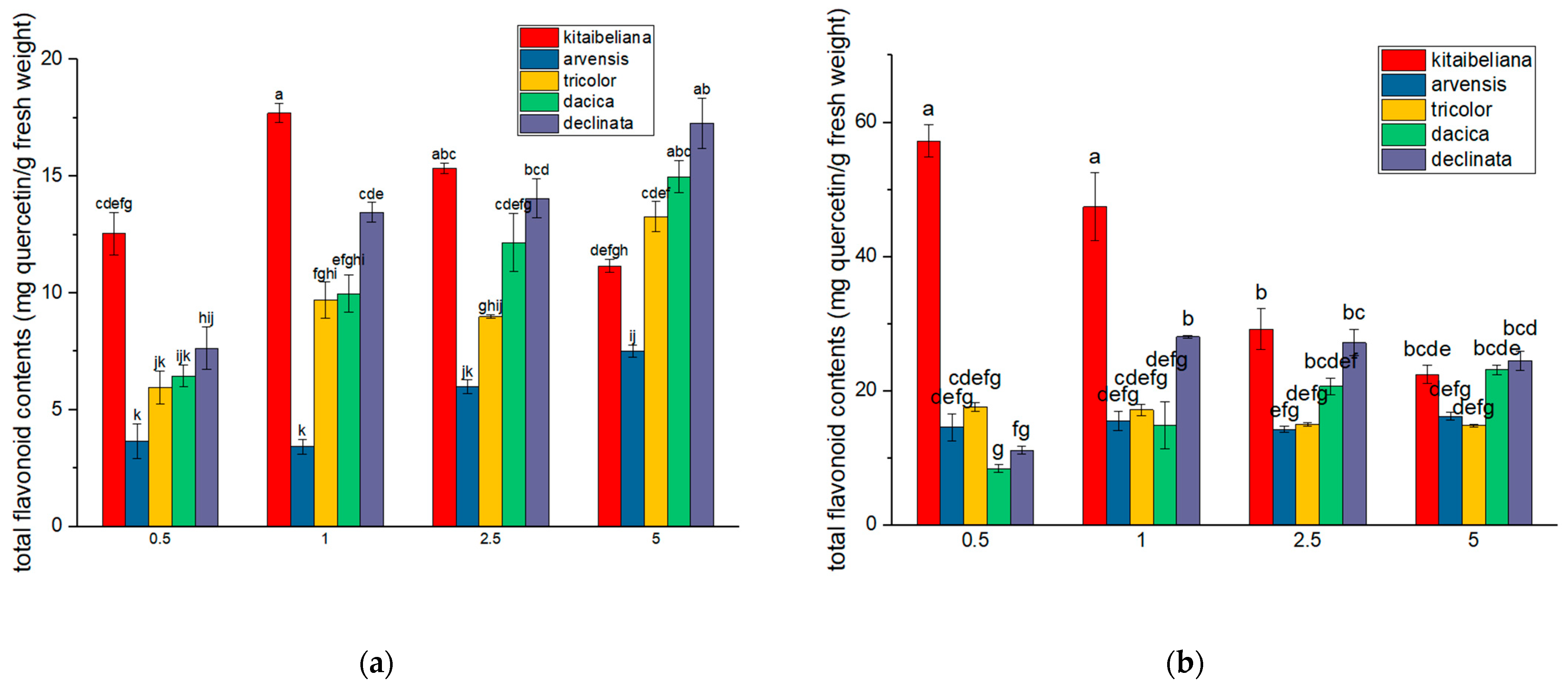

2.4. Flavonoid Content

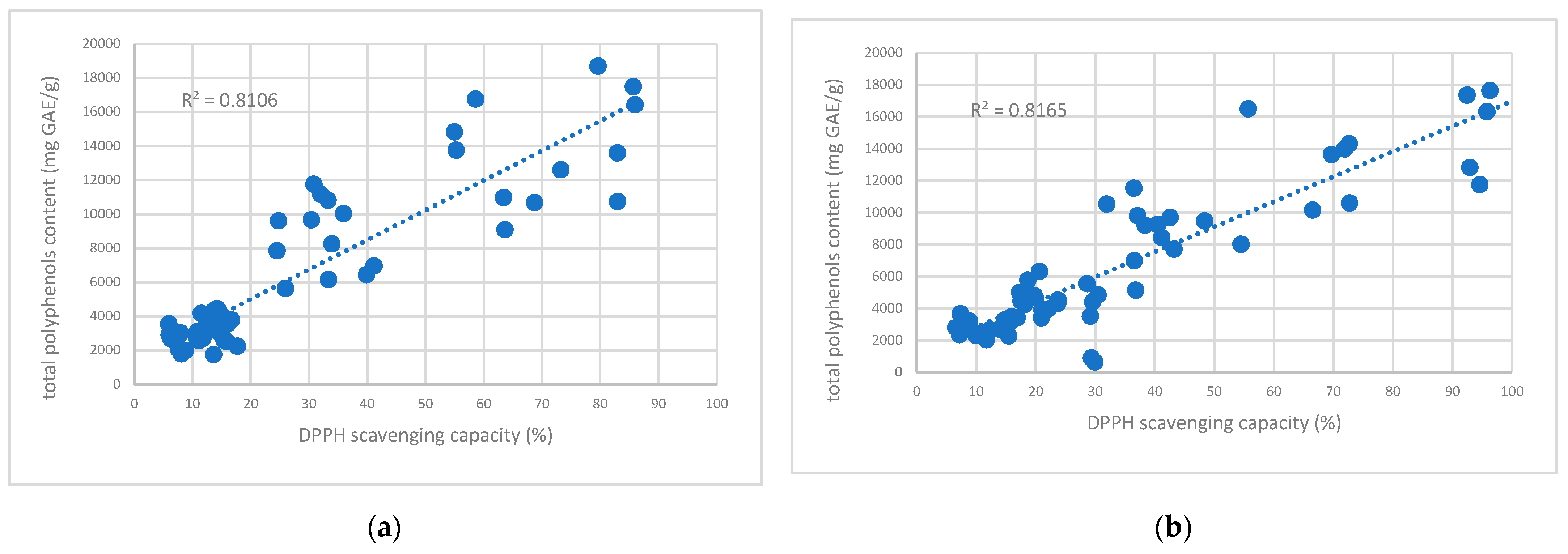

2.5. Scavenging Capacity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents |

| pp | Population |

References

- Ballard, H.E., Jr.; Sytsma, K.J.; Kowal, R.R. Shrinking the violets: Phylogenetic relationships of infrageneric groups in Viola (Violaceae) based on internal transcribed spacer DNA sequences. Syst. Bot. 1999, 23, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sârbu, I.; Ştefan, N.; Oprea, A. Plante Vasculare din România: Determinator Ilustrat de Teren; Victor B Victor: Bucureşti, Romania, 2013; pp. 452–460. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, C.; Ivanescu, L. Plante Vasculare din România. Determinator Ilustrat de Teren (Vascular Plants of Romania. An Illustrated Field Guide); Analele Stiintifice Ale Universitatii “Al. I. Cuza” Din Iasi: Iasi, Romania, 2013; Volume 59, p. 109. [Google Scholar]

- Marcussen, T.; Heier, L.; Brysting, A.K.; Oxelman, B.; Jakobsen, K.S. From gene trees to a dated allopolyploid network: Insights from the angiosperm genus Viola (Violaceae). Syst. Biol. 2015, 64, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcussen, T.; Heier, L.; Brysting, A.K.; Oxelman, B.; Ballard, H.E. A revised phylogenetic classification for Viola (Violaceae). Plants 2022, 11, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batiha, G.E.S.; Lukman, H.Y.; Shaheen, H.M.; Wasef, L.; Hafiz, A.A.; Conte-Junior, C.A.; Al-Farga, A.; Chamba, V.M.M.; Lawal, B. A systematic review of phytochemistry, nutritional composition, and pharmacologic application of species of the genus Viola in noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2023, 2023, 5406039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appell, D.S. The Ethnobotanical Uses of the Genus Viola by Native Americans. Violet Gaz. 2000, B1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rimkiene, S.; Ragazinskiene, O.; Savickiene, N. The cumulation of Wild pansy (Viola tricolor L.) accessions: The possibility of species preservation and usage in medicine. Medicina 2003, 39, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pilberg, C.; Ricco, M.V.; Alvarez, M.A. Foliar anatomy of Viola maculata growing in Parque Nacional Los Alerces, Chubut, Patagonia, Argentina. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2016, 26, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Chen, S. A comprehensive review of phytochemistry, pharmacology and quality control of plants from the genus Viola. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2023, 75, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastagir, G.; Bibi, S.; Uza, N.U.; Bussmann, R.W.; Ahmad, I. Microscopic evaluation, ethnobotanical and phytochemical profiling of a traditional drug Viola odorata L. from Pakistan. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2023, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toiu, A.; Muntean, E.; Oniga, I.; Tămaş, M. Pharmacognostic research on Viola declinata Waldst. et Kit. (Violaceae). Farmacia 2009, 57, 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Pană, S.; Cojuhari, T.; Bacalov, I.; Fărâmă, V.; Topal, N. Compoziţia chimică a plantelor medicinale din grădina botanică a muzeului naţional de etnografie şi istorie naturală. Ghid teoretico-informativ de specialitate. Bul. Ştiinţific. Rev. De Etnogr. Ştiinţele Nat. Şi Muzeol. (Ser. Nouă) 2012, 29, 104–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, D.; Kohli, G.; Prasad, K.; Bisht, G.; Punetha, V.D.; Khetwal, K.S.; Kumar, M.D.; Pandey, H.K. Phytochemical and ethnomedicinal uses of family Violaceae. Curr. Res. Chem. 2015, 7, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.; Kadereit, J.W. Identity of the Calcarata species complex in Viola sect. Melanium (Violaceae). Willdenowia 2020, 50, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, S.; Scoppola, A. Cytological status of Viola kitaibeliana (Section Melanium, Violaceae) in Europe. Phytotaxa 2015, 238, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beldie, A. Viola. In Flora Republicii Populare Române; Savulescu, T., Ed.; Editura Academiei Republicii Populare Române: Bucharest, Romania, 1955; Volume 3, pp. 553–625. [Google Scholar]

- Dayani, L.; Varshosaz, J.; Aliomrani, M.; Dinani, M.S.; Hashempour, H.; Taheri, A. Morphological studies of self-assembled cyclotides extracted from Viola odorata as novel versatile platforms in biomedical applications. Biomater. Sci. 2022, 10, 5172–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayden, W.J.; Clough, J. Methyl salicylate secretory cells in roots of Viola arvensis and V. rafinesquii (Violaceae). Castanea 1990, 55, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsell, B.; Ericsson, S.; Fröberg, L.; Rostański, K.; Snogerup, S.; Widén, B. Nomenclatural notes to Flora Nordica Vol. 6 (Thymelaeaceae–Apiaceae). Nord. J. Bot. 2009, 27, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Naik, B.; Mishra, P. (Eds.) Edible Flowers: Health Benefits, Nutrition, Processing, and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hellinger, R.; Koehbach, J.; Fedchuk, H.; Sauer, B.; Huber, R.; Gruber, C.W.; Gründemann, C. Immunosuppressive activity of an aqueous Viola tricolor herbal extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrini, S.; Zucconi, L. Seed germination of the endangered Viola kitaibeliana and other Italian annual pansies (Viola Section Melanium, Violaceae). Flora 2020, 30, 425. [Google Scholar]

- Coldea, G.; Stoica, I.A.; Puşcaş, M.; Ursu, T.; Oprea, A.; IntraBioDiv Consortium. Alpine–subalpine species richness of the Romanian Carpathians and the current conservation status of rare species. Biodivers Conserv. 2009, 18, 1441–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burescu, I.N.L. Rare, endangered, vulnerable, endemic, relict plants and animals encompassing high conservation values for the forests of Vlădeasa mountains-the northern Apuseni mountains. Analele Univ. Din Oradea Fasc. Protecția Mediu. 2015, 25, 309–318. [Google Scholar]

- Hurdu, B.I.; Puşcaş, M.; Turtureanu, P.D.; Niketić, M.; Vonica, G.; Coldea, G. A critical evaluation of the Carpathian endemic plant taxa list from the Romanian Carpathians. Contrib. Bot. 2012, 47, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Togor, G.C.; Burescu, P. Species-rich Nardus grasslands from the northern part of the Bihor Mountains. Stud. Univ. “Vasile Goldis” Arad. Ser. Stiintele Vietii (Life Sci. Ser.) 2013, 23, 505. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiu, V. Carpathians endemic taxa in argeş county. Curr. Trends Nat. Sci. 2013, 2, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Soare, L.C.; Ferdeș, M.; Dobrescu, C.-M. Species with potential for anthocyanins extraction in Argeș County flora. Muzeul Olten. Craiova. Oltenia. Stud. Și Comunicări. Științele Naturii. 2011, 27, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Toiu, A.; Vlase, L.; Oniga, I.; Tamas, M. Quantitative analysis of some phenolic compounds from viola species tinctures. Farma. J. 2008, 56, 440–445. [Google Scholar]

- Toiu, A.; Oniga, I.; Vlase, L. Determination of flavonoids from Viola arvensis and V. declinata (Violaceae). Hops Med. Plants 2017, 25, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weathers, K.C.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Pickett, S.T. Forest edges as nutrient and pollutant concentrators: Potential synergisms between fragmentation, forest canopies, and the atmosphere. Conserv. Biol. 2001, 15, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, J.G.; Montserrat-Martí, G.; Charles, M.; Jones, G.; Wilson, P.; Shipley, B.; Sharafi, M.; Cerabolini, B.E.L.; Cornelissen, J.H.; Band, S.R.; et al. Is leaf dry matter content a better predictor of soil fertility than specific leaf area? Ann. Bot. 2011, 108, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Y.F.Y.; Ghatas, Y.A.A. Effect of mineral, biofertilizer (EM) and zeolite on growth, flowering, yield and composition of volatile oil of Viola odorata L. plants. J. Ornam. Hortic. 2016, 8, 140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Letos, D.; Muntele, I. The capitalization of the touristic potential of Cozla Mountain. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2011, 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, H.; Uragami, C.; Cogdell, R.J. Carotenoids and photosynthesis. In Carotenoids in Nature: Biosynthesis, Regulation and Function; Stange, C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzad, M.; Griesbach, R.; Hammond, J.; Weiss, M.R.; Elmendorf, H.G. Differential expression of three key anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in a color-changing flower, Viola cornuta cv. Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Plant Sci. 2003, 165, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalrymple, R.L.; Kemp, D.J.; Flores-Moreno, H.; Laffan, S.W.; White, T.E.; Hemmings, F.A.; Moles, A.T. Macroecological patterns in flower colour are shaped by both biotic and abiotic factors. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1972–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.J.; Thompson, K.E.N.; Hodgson, J.G. Specific leaf area and leaf dry matter content as alternative predictors of plant strategies. New Phytol. 1999, 143, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Sun, H.Y.; Shang, X. Flower color patterning in pansy (Viola× wittrockiana Gams.) is caused by the differential expression of three genes from the anthocyanin pathway in acyanic and cyanic flower areas. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 84, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słomka, A.; Libik-Konieczny, M.; Kuta, E.; Miszalski, Z. Metalliferous and non-metalliferous populations of Viola tricolor represent similar mode of antioxidative response. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muriithi, A.N.; Wamocho, L.S.; Njoroge, J.B.M. Effect of pH and magnesium on colour development and anthocyanin accumulation in tuberose florets. Afr. Crop Sci. Conf. Proc. 2009, 9, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, B.; Katarina, V.M.; Paula, P.; Matevž, L.; Neva, S.; Primož, P.; Primož, V.; Jeromel, L.; Marjana, R. Metallophyte status of violets of the section Melanium. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1844–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iijima, L.; Kishimoto, S.; Aida, R.; Nakayama, M.; Morita, Y.; Ono, E.; Mizukami, Y.; Morimoto, R.; Sasaki, N.; Ozeki, Y.; et al. Esterified carotenoids are synthesized in petals of carnation (Dianthus caryophyllus) and accumulate in differentiated chromoplasts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miszczak, R.; Slazak, B.; Sychta, K.; Göransson, U.; Nilsson, A.; Słomka, A. Interpopulational variation in cyclotide production in heavy-metal-treated pseudometallophyte (Viola tricolor L.). Plants 2025, 14, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashina, T. Contribution to flower colors of flavonoids including anthocyanins: A review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1934578X1501000335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 620–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatoteva, D.; Tsvetkova, E.; Bezlova, D. Heavy metals and arsenic in soils from grasslands in Bulgarka Nature Park. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 20, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Vermerris, W.; Nicholson, R. Phenolic Compound Biochemistry; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Di Ferdinando, M.; Brunetti, C.; Agati, G.; Tattini, M. Multiple functions of polyphenols in plants inhabiting unfavorable Mediterranean areas. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 103, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesco, S.; Mimmo, T.; Tonon, G.; Tomasi, N.; Pinton, R.; Terzano, R.; Neumann, G.; Weisskopf, L.; Renella, G.; Landi, L.; et al. Plant-borne flavonoids released into the rhizosphere: Impact on soil bio-activities related to plant nutrition—A review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2012, 48, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesco, S.; Neumann, G.; Tomasi, N.; Pinton, R.; Weisskopf, L. Release of plant-borne flavonoids into the rhizosphere and their role in plant nutrition. Plant Soil 2010, 329, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, A.; Farid, M. Effect of temperatures on polyphenols during extraction. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinelo, M.; Rubilar, M.; Jerez, M.; Sineiro, J.; Núñez, M.J. Effect of solvent, temperature, and solvent-to-solid ratio on the total phenolic content and antiradical activity of extracts from different components of grape pomace. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 2111–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinelo, M.; Arnous, A.; Meyer, A.S. Upgrading of grape skins: Significance of plant cell-wall structural components and extraction techniques for phenol release. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, P.; Felhofer, M.; Mayer, K.; Gierlinger, N. A guide to elucidate the hidden multicomponent layered structure of plant cuticles by Raman imaging. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 793330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnich, E.; Bjarnholt, N.; Eudes, A.; Harholt, J.; Holland, C.; Jørgensen, B.; Larsen, F.H.; Liu, M.; Manat, R.; Meyer, A.S.; et al. Phenolic cross-links: Building and de-constructing the plant cell wall. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 919–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezlova, D.; Tsvetkova, E.; Karatoteva, D.; Malinova, L. Content of heavy metals and arsenic in medicinal plants from recreational areas in Bulgarka Nature Park. Genet. Plant Physiol. 2012, 2, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, G.A.; Kumar, S.; Bhardwaj, R.; Swapnil, P.; Meena, M.; Seth, C.S.; Yadav, A. Recent advancements in multifaceted roles of flavonoids in plant–rhizomicrobiome interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1297706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Su, S. Growth and physiological response of Viola tricolor L. to NaCl and NaHCO3 stress. Plants 2023, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanvand, A.; Saadatmand, S.; Lari Yazdi, H.; Iranbakhsh, A. Biosynthesis of NanoSilver and Its Effect on Key Genes of Flavonoids and Physicochemical Properties of Viola tricolor L. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. A Sci. 2021, 45, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Geetanjali. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation in legume nodules: Process and signaling: A review. In Sustainable Agriculture; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 519–531. [Google Scholar]

- Aquilano, K.; Baldelli, S.; Rotilio, G.; Ciriolo, M.R. Role of nitric oxide synthases in Parkinson’s disease: A review on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of polyphenols. Neurochem. Res. 2008, 33, 2416–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piana, M.; Zadra, M.; de Brum, T.F.; Boligon, A.A.; Goncalves, A.F.K.; da Cruz, R.C.; de Freitas, R.B.; Canto, G.S.D.; Athayde, M.L. Analysis of rutin in the extract and gel of Viola tricolor. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2013, 51, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cory, H.; Passarelli, S.; Szeto, J.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The role of polyphenols in human health and food systems: A mini-review. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 370438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chifu, T.; Zamfirescu, O.; Mânzu, C.; Şurubaru, B. Botanică Sistematică–Cormobionta; Editura Universităţii “Alexandru Ioan Cuza”: Iaşi, Romania, 2001; pp. 388–389. [Google Scholar]

- Chifu, T.; Mânzu, C.; Zamfirescu, O. Flora şi vegetaţia Moldovei (României); Editura Universităţii “Alexandru Ioan Cuza”: Iaşi, Romania, 2006; pp. 290–291. [Google Scholar]

- Younis, M.E.; El-Shahaby, O.A.; Abo-Hamed, S.A.; Ibrahim, A.H. Effects of water stress on growth, pigments and 14CO2 assimilation in three sorghum cultivars. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2000, 185, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuleki, T.; Francis, F.J. Quantitative methods for anthocyanins. 1. Extraction and determination of total anthocyanin in cranberries. J. Food Sci. 1986, 33, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrolstad, R.E.; Durst, R.W.; Lee, J. Tracking color and pigment changes in anthocyanin products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Tang, M.; Wu, J. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herald, T.J.; Gadgil, P.; Tilley, M. High-throughput micro plate assays for screening flavonoid content and DPPH-scavenging activity in sorghum bran and flour. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 92, 2326–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I. Extraction of phenolic compounds: A review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Z.; Subbiah, V.; Suleria, H.A.R. Extraction and characterization of phenolic compounds and their potential antioxidant activities. Environ Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 81112–81129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blois, M.S. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature 1958, 181, 1199–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobiuc, A.; Vasilache, V.; Pintilie, O.; Stoleru, T.; Burducea, M.; Oroian, M.; Zamfirache, M.M. Blue and red LED illumination improves growth and bioactive compounds contents in acyanic and cyanic Ocimum basilicum L. microgreens. Molecules 2017, 22, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Plant Population | Biocoenose | Landform |

|---|---|---|---|

| V. kitaibeliana | pp. 1 | hayfield, agricultural area | plateau ≈365 m above sea level |

| pp. 2 | agricultural area | plateau ≈450 m above sea level | |

| pp. 3 | pasture | low hilly area ≈122 m above sea level | |

| V. arvensis | pp. 1 | agricultural area | plateau ≈365 m above sea level |

| pp. 2 | pasture, agricultural area | low hilly area ≈122 m above sea level | |

| pp. 3 | agricultural area | plateau ≈450 m above sea level | |

| V. tricolor | pp. 1 | agricultural area | plateau ≈365 m above sea level |

| pp. 2 | agricultural area | plateau ≈450 m above sea level | |

| pp. 3 | agricultural area | plateau ≈550 m above sea level | |

| V. dacica | pp. 1 | alpine meadow | Călimani mountains ≈1.043 m above sea level |

| pp. 2 | alpine meadow | Călimani mountains ≈1.150 m above sea level | |

| pp. 3 | alpine meadow | Călimani mountains ≈1.100 m above sea level | |

| V. declinata | pp. 1 | alpine meadow | Călimani mountains ≈1.043 m above sea level |

| pp. 2 | subalpine meadow | Călimani mountains ≈962 m above sea level | |

| pp. 3 | alpine meadow | Călimani mountains ≈1.100 m above sea level |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosenhech, E.; Lobiuc, A.; Boz, I.; Zamfirache, M.-M. The Phytochemical Potential of Viola Species, Melanium Subgenus, Subsection Bracteolatae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311614

Rosenhech E, Lobiuc A, Boz I, Zamfirache M-M. The Phytochemical Potential of Viola Species, Melanium Subgenus, Subsection Bracteolatae. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311614

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosenhech, Elida, Andrei Lobiuc, Irina Boz, and Maria-Magdalena Zamfirache. 2025. "The Phytochemical Potential of Viola Species, Melanium Subgenus, Subsection Bracteolatae" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311614

APA StyleRosenhech, E., Lobiuc, A., Boz, I., & Zamfirache, M.-M. (2025). The Phytochemical Potential of Viola Species, Melanium Subgenus, Subsection Bracteolatae. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311614