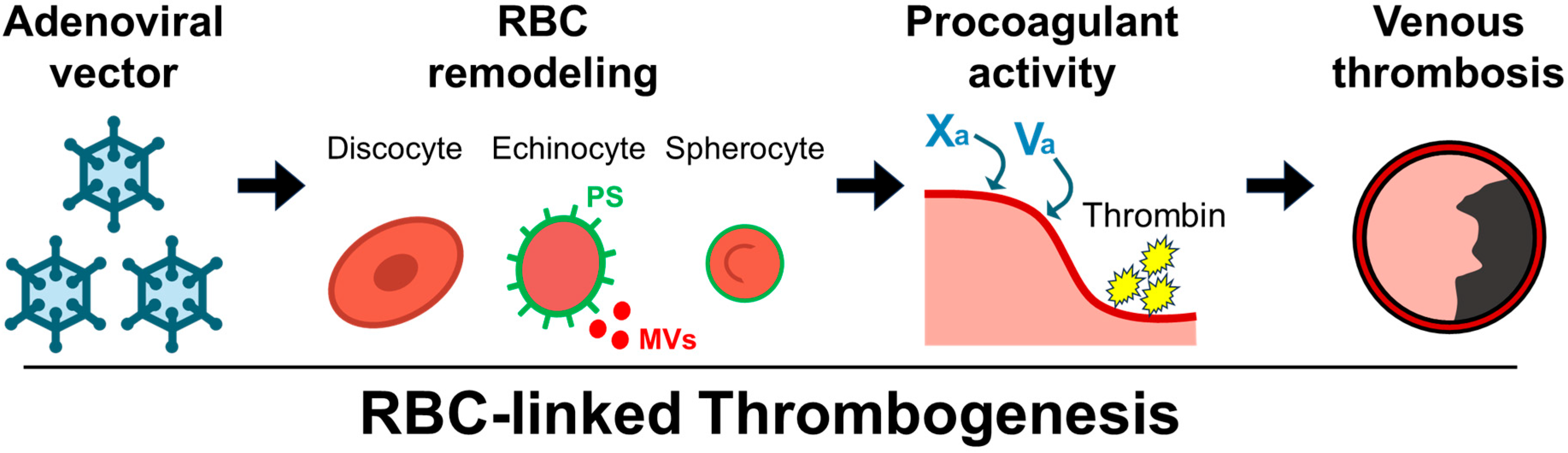

Red Blood Cell-Associated Features of Adenoviral Vector-Linked Venous Thrombosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

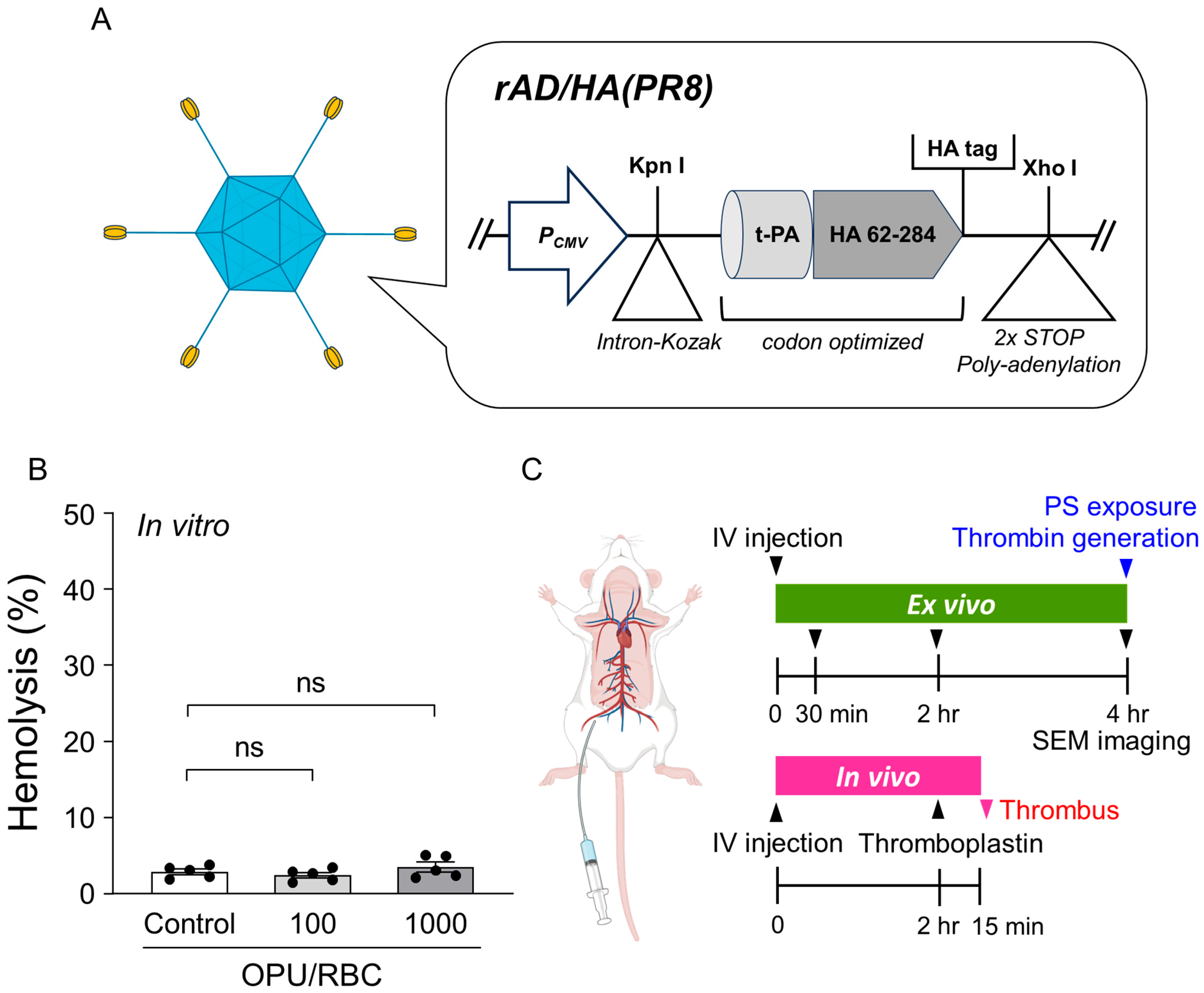

2.1. Vector Overview, Sub-Hemolytic Window, and Study Workflow

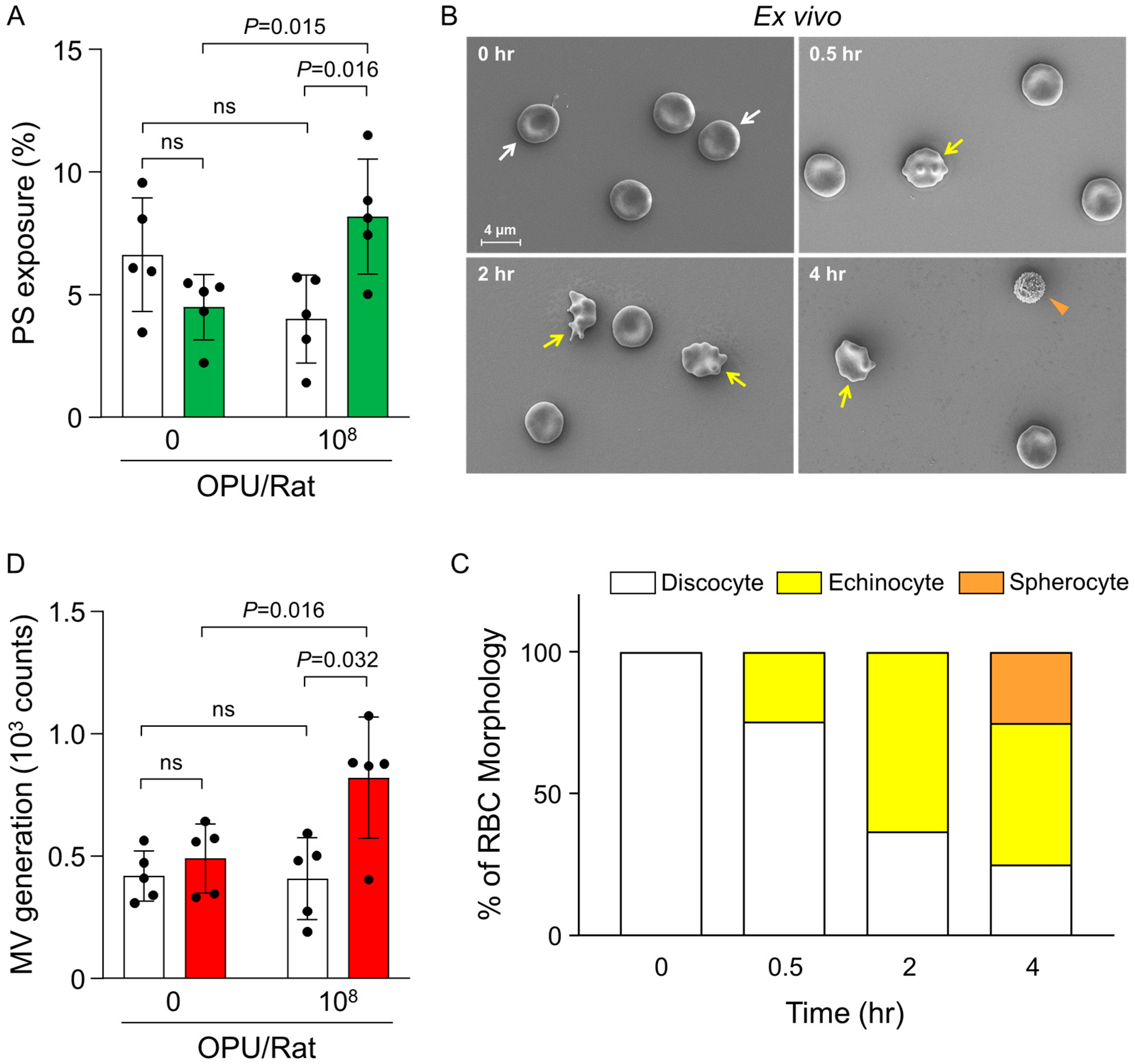

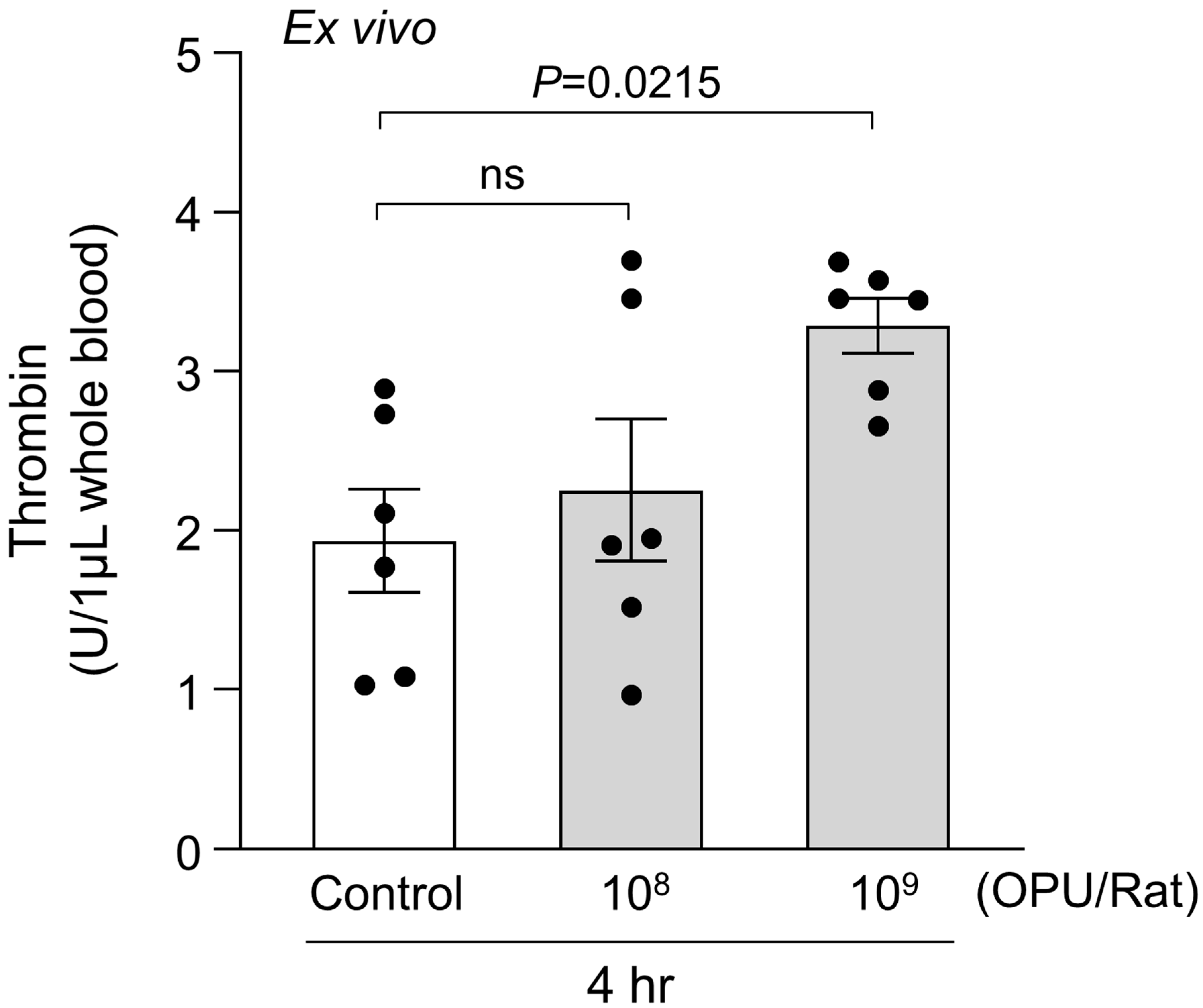

2.2. Ex Vivo Evaluation of PS Exposure, RBC Morphology, and MV Generation in Relation to Thrombin Generation

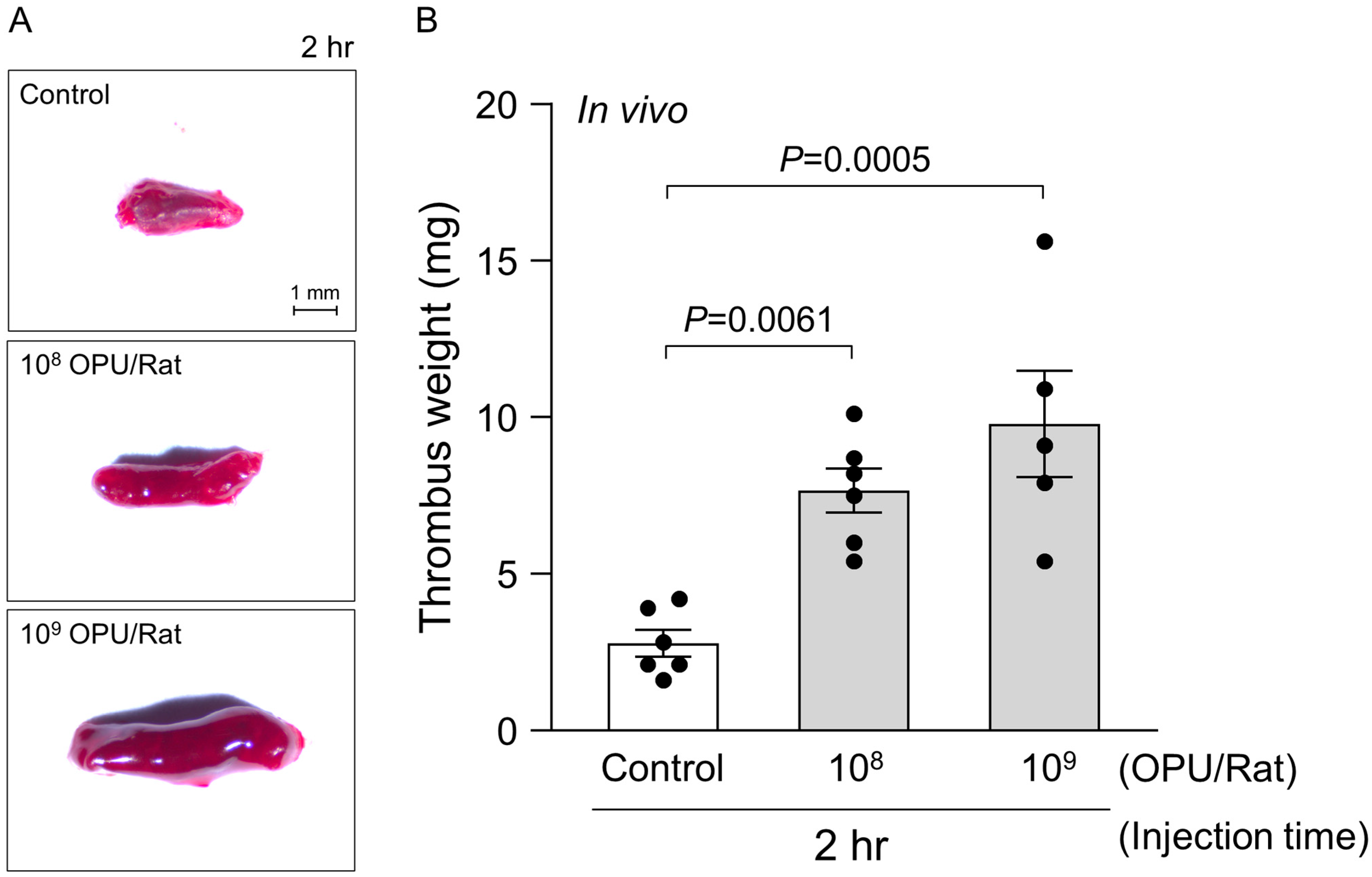

2.3. In Vivo Assessment of Venous Thrombosis Under a Sub-Hemolytic Window

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Adenovirus Vector Preparation

4.2. Ethical Approval and Animal Preparation

4.3. In Vitro Measurement of Hemolytic Activity

4.4. Ex Vivo Assessment of Thrombin Generation

4.5. Ex Vivo Assessment of Phosphatidylserine Exposure by Flow Cytometry

4.6. Ex Vivo RBC Morphology Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscopy

4.7. In Vivo Venous Thrombosis Model

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kyriakidis, N.C.; Lopez-Cortes, A.; Gonzalez, E.V.; Grimaldos, A.B.; Prado, E.O. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines strategies: A comprehensive review of phase 3 candidates. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.C.; Li, Y.H.; Guan, X.H.; Hou, L.H.; Wang, W.J.; Li, J.X.; Wu, S.P.; Wang, B.S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a recombinant adenovirus type-5 vectored COVID-19 vaccine: A dose-escalation, open-label, non-randomised, first-in-human trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1845–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greinacher, A.; Thiele, T.; Warkentin, T.E.; Weisser, K.; Kyrle, P.A.; Eichinger, S. Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 Vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2092–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, E.V.C.; Bouazza, F.Z.; Dauby, N.; Mullier, F.; d’Otreppe, S.; Jissendi Tchofo, P.; Bartiaux, M.; Sirjacques, C.; Roman, A.; Hermans, C.; et al. Fatal vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT) post Ad26.COV2.S: First documented case outside US. Infection 2022, 50, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottegard, A.; Lund, L.C.; Karlstad, O.; Dahl, J.; Andersen, M.; Hallas, J.; Lidegaard, O.; Tapia, G.; Gulseth, H.L.; Ruiz, P.L.; et al. Arterial events, venous thromboembolism, thrombocytopenia, and bleeding after vaccination with Oxford-AstraZeneca ChAdOx1-S in Denmark and Norway: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2021, 373, n1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dag Berild, J.; Bergstad Larsen, V.; Myrup Thiesson, E.; Lehtonen, T.; Grosland, M.; Helgeland, J.; Wolhlfahrt, J.; Vinslov Hansen, J.; Palmu, A.A.; Hviid, A. Analysis of Thromboembolic and Thrombocytopenic Events After the AZD1222, BNT162b2, and MRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccines in 3 Nordic Countries. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2217375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, R.C.; Di, Y.; Cerny, A.M.; Sonnen, A.F.; Sim, R.B.; Green, N.K.; Subr, V.; Ulbrich, K.; Gilbert, R.J.; Fisher, K.D.; et al. Human erythrocytes bind and inactivate type 5 adenovirus by presenting Coxsackie virus-adenovirus receptor and complement receptor 1. Blood 2009, 113, 1909–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alba, R.; Bradshaw, A.C.; Parker, A.L.; Bhella, D.; Waddington, S.N.; Nicklin, S.A.; van Rooijen, N.; Custers, J.; Goudsmit, J.; Barouch, D.H.; et al. Identification of coagulation factor (F)X binding sites on the adenovirus serotype 5 hexon: Effect of mutagenesis on FX interactions and gene transfer. Blood 2009, 114, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.T.; Boyd, R.J.; Sarkar, D.; Teijeira-Crespo, A.; Chan, C.K.; Bates, E.; Waraich, K.; Vant, J.; Wilson, E.; Truong, C.D.; et al. ChAdOx1 interacts with CAR and PF4 with implications for thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabl8213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voysey, M.; Clemens, S.A.C.; Madhi, S.A.; Weckx, L.Y.; Folegatti, P.M.; Aley, P.K.; Angus, B.; Baillie, V.L.; Barnabas, S.L.; Bhorat, Q.E.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: An interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet 2021, 397, 99–111, Erratum in Lancet 2021, 397, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoubkhani, D.; Bermingham, C.; Pouwels, K.B.; Glickman, M.; Nafilyan, V.; Zaccardi, F.; Khunti, K.; Alwan, N.A.; Walker, A.S. Trajectory of long covid symptoms after COVID-19 vaccination: Community based cohort study. BMJ 2022, 377, e069676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catala, M.; Mercade-Besora, N.; Kolde, R.; Trinh, N.T.H.; Roel, E.; Burn, E.; Rathod-Mistry, T.; Kostka, K.; Man, W.Y.; Delmestri, A.; et al. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines to prevent long COVID symptoms: Staggered cohort study of data from the UK, Spain, and Estonia. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, B.A.; Metaxaki, M.; Wills, M.R.; Sithole, N. Reduced Incidence of Long Coronavirus Disease Referrals to the Cambridge University Teaching Hospital Long Coronavirus Disease Clinic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 738–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisel, J.W.; Litvinov, R.I. Red blood cells: The forgotten player in hemostasis and thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 17, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkarithi, G.; Duval, C.; Shi, Y.; Macrae, F.L.; Ariens, R.A.S. Thrombus Structural Composition in Cardiovascular Disease. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 2370–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, N.J.; Stowe, J.; Ramsay, M.E.; Miller, E. Risk of venous thrombotic events and thrombocytopenia in sequential time periods after ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccines: A national cohort study in England. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 13, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisel, J.W.; Litvinov, R.I. Visualizing thrombosis to improve thrombus resolution. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 5, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelihan, M.F.; Zachary, V.; Orfeo, T.; Mann, K.G. Prothrombin activation in blood coagulation: The erythrocyte contribution to thrombin generation. Blood 2012, 120, 3837–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernysh, I.N.; Nagaswami, C.; Kosolapova, S.; Peshkova, A.D.; Cuker, A.; Cines, D.B.; Cambor, C.L.; Litvinov, R.I.; Weisel, J.W. The distinctive structure and composition of arterial and venous thrombi and pulmonary emboli. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutwiler, V.; Mukhitov, A.R.; Peshkova, A.D.; Le Minh, G.; Khismatullin, R.R.; Vicksman, J.; Nagaswami, C.; Litvinov, R.I.; Weisel, J.W. Shape changes of erythrocytes during blood clot contraction and the structure of polyhedrocytes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, M.; Onion, D.; Green, N.K.; Aslan, K.; Rajaratnam, R.; Bazan-Peregrino, M.; Phipps, S.; Hale, S.; Mautner, V.; Seymour, L.W.; et al. Adenovirus type 5 interactions with human blood cells may compromise systemic delivery. Mol. Ther. 2006, 14, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Campello, E.; Zou, J.; Konings, J.; Huskens, D.; Wan, J.; Fernandez, D.I.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.M.; Ten Cate, H.; Toffanin, S.; et al. Crucial roles of red blood cells and platelets in whole blood thrombin generation. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 6717–6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, T.; Stefanoni, D.; Dzieciatkowska, M.; Issaian, A.; Nemkov, T.; Hill, R.C.; Francis, R.O.; Hudson, K.E.; Buehler, P.W.; Zimring, J.C.; et al. Evidence of Structural Protein Damage and Membrane Lipid Remodeling in Red Blood Cells from COVID-19 Patients. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 4455–4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eder, J.; Schumm, L.; Armann, J.P.; Puhan, M.A.; Beuschlein, F.; Kirschbaum, C.; Berner, R.; Toepfner, N. Increased red blood cell deformation in children and adolescents after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Choi, Y.; Nguyen, H.H.; Song, M.K.; Chang, J. Mucosal immunization with recombinant adenovirus encoding soluble globular head of hemagglutinin protects mice against lethal influenza virus infection. Immune Netw. 2013, 13, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folegatti, P.M.; Ewer, K.J.; Aley, P.K.; Angus, B.; Becker, S.; Belij-Rammerstorfer, S.; Bellamy, D.; Bibi, S.; Bittaye, M.; Clutterbuck, E.A.; et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: A preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 467–478, Erratum in Lancet 2020, 396, 466 and Erratum in Lancet 2020, 396, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoff, J.; Le Gars, M.; Shukarev, G.; Heerwegh, D.; Truyers, C.; de Groot, A.M.; Stoop, J.; Tete, S.; Van Damme, W.; Leroux-Roels, I.; et al. Interim Results of a Phase 1-2a Trial of Ad26.COV2.S Covid-19 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1824–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, F.; Ammollo, C.T.; Esmon, N.L.; Esmon, C.T. Histones induce phosphatidylserine exposure and a procoagulant phenotype in human red blood cells. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2014, 12, 1697–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Xu, M.; Li, Z.; An, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Xia, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; et al. TMEM16F mediated phosphatidylserine exposure and microparticle release on erythrocyte contribute to hypercoagulable state in hyperuricemia. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2022, 96, 102666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, A.P., 3rd; Mackman, N. Tissue factor and thrombosis: The clot starts here. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 104, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, C.; Zhuang, J.; Qi, W.; Jiang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhao, W.; Cao, Y.; Wu, H.; Qi, J.; et al. The role of phosphatidylserine on the membrane in immunity and blood coagulation. Biomark. Res. 2022, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cines, D.B.; Greinacher, A. Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. Blood 2023, 141, 1659–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, H.Y.; Bian, Y.; Lim, K.M.; Kim, B.S.; Choi, S.H. MARTX toxin of Vibrio vulnificus induces RBC phosphatidylserine exposure that can contribute to thrombosis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazzaoui, A.; Abdellatif, A.A.H. Vaccine delivery systems and administration routes: Advanced biotechnological techniques to improve the immunization efficacy. Vaccine X 2024, 19, 100500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudlay, D.; Svistunov, A.; Satyshev, O. COVID-19 Vaccines: An Updated Overview of Different Platforms. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stebbings, R.; Armour, G.; Pettis, V.; Goodman, J. AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCov-19): A Single-Dose biodistribution study in mice. Vaccine 2022, 40, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzarone, B.; Veneziani, I.; Moretta, L.; Maggi, E. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombotic Thrombocytopenia in People Receiving Anti-COVID-19 Adenoviral-Based Vaccines: A Proposal. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 728513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zheng, L.; Yan, S.; Xuan, X.; Yang, Y.; Qi, X.; Dong, H. Understanding the role of red blood cells in venous thromboembolism: A comprehensive review. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 367, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetto, A.; Campello, E.; Bulato, C.; Willems, R.; Konings, J.; Roest, M.; Gavasso, S.; Nuozzi, G.; Toffanin, S.; Zanaga, P.; et al. Whole blood thrombin generation shows a significant hypocoagulable state in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 22, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, R.A.L.; Konings, J.; Huskens, D.; Middelveld, H.; Pepels-Aarts, N.; Verbeet, L.; de Groot, P.G.; Heemskerk, J.W.M.; Ten Cate, H.; de Vos-Geelen, J.; et al. Altered whole blood thrombin generation and hyperresponsive platelets in patients with pancreatic cancer. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2024, 22, 1132–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peshkova, A.D.; Rednikova, E.K.; Khismatullin, R.R.; Kim, O.V.; Muzykantov, V.R.; Purohit, P.K.; Litvinov, R.I.; Weisel, J.W. Red blood cell aggregation within a blood clot causes platelet-independent clot shrinkage. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 3418–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavord, S.; Scully, M.; Hunt, B.J.; Lester, W.; Bagot, C.; Craven, B.; Rampotas, A.; Ambler, G.; Makris, M. Clinical Features of Vaccine-Induced Immune Thrombocytopenia and Thrombosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1680–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, R.J.; Tamborska, A.; Singh, B.; Craven, B.; Marigold, R.; Arthur-Farraj, P.; Yeo, J.M.; Zhang, L.; Hassan-Smith, G.; Jones, M.; et al. Cerebral venous thrombosis after vaccination against COVID-19 in the UK: A multicentre cohort study. Lancet 2021, 398, 1147–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Jo, H.; Kim, H.; Park, J.; Pizzol, D.; Kim, M.S.; Woo, H.G.; Yon, D.K. Global Burden of Vaccine-Associated Cerebrovascular Venous Sinus Thrombosis, 1968–2024: A Critical Analysis From the WHO Global Pharmacovigilance Database. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2025, 40, e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudrick, H.E.; Lu, S.C.; Bhandari, J.; Barry, M.E.; Hemsath, J.R.; Andres, F.G.M.; Ma, O.X.; Barry, M.A.; Reddy, V.S. Structure-derived insights from blood factors binding to the surfaces of different adenoviruses. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspary, L.; Shaw, J.R.; Stalder, O.; Brodard, J.; Angelillo-Scherrer, A.; Vrotniakaite-Bajerciene, K. Clinical utility of thrombin generation using ST-Genesia(R) in patients with hereditary and acquired thrombophilia: A cross-sectional study. Thromb. Res. 2025, 254, 109454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetto, A.; Campello, E.; Bulato, C.; Willems, R.; Konings, J.; Roest, M.; Gavasso, S.; Nuozzi, G.; Toffanin, S.; Burra, P.; et al. Impaired whole blood thrombin generation is associated with procedure-related bleeding in acutely decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Duffy, M.R.; Deng, L.; Dakin, R.S.; Uil, T.; Custers, J.; Kelly, S.M.; McVey, J.H.; Nicklin, S.A.; Baker, A.H. Manipulating adenovirus hexon hypervariable loops dictates immune neutralisation and coagulation factor X-dependent cell interaction in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bliss, C.M.; Hulin-Curtis, S.L.; Williams, M.; Maruskova, M.; Davies, J.A.; Statkute, E.; Baker, A.T.; Stack, L.; Kerstetter, L.; Kerr-Jones, L.E.; et al. A pseudotyped adenovirus serotype 5 vector with serotype 49 fiber knob is an effective vector for vaccine and gene therapy applications. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2024, 32, 101308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoff, J.; Gray, G.; Vandebosch, A.; Cardenas, V.; Shukarev, G.; Grinsztejn, B.; Goepfert, P.A.; Truyers, C.; Van Dromme, I.; Spiessens, B.; et al. Final Analysis of Efficacy and Safety of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 847–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Tang, R.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhu, F.; Li, J. Vaccination with Adenovirus Type 5 Vector-Based COVID-19 Vaccine as the Primary Series in Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase 1/2 Clinical Trial. Vaccines 2024, 12, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, H.; Bae, O.-N.; Choi, S.; Lee, E.; Chang, J.; Chung, H.Y. Red Blood Cell-Associated Features of Adenoviral Vector-Linked Venous Thrombosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311606

Park H, Bae O-N, Choi S, Lee E, Chang J, Chung HY. Red Blood Cell-Associated Features of Adenoviral Vector-Linked Venous Thrombosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311606

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Hanjin, Ok-Nam Bae, Sungbin Choi, Eunha Lee, Jun Chang, and Han Young Chung. 2025. "Red Blood Cell-Associated Features of Adenoviral Vector-Linked Venous Thrombosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311606

APA StylePark, H., Bae, O.-N., Choi, S., Lee, E., Chang, J., & Chung, H. Y. (2025). Red Blood Cell-Associated Features of Adenoviral Vector-Linked Venous Thrombosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311606