The Current Role of Antiangiogenics in Colorectal Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. From Benchside to Bedside

2.1. Role of Angiogenesis in Pathophysiology of CRC

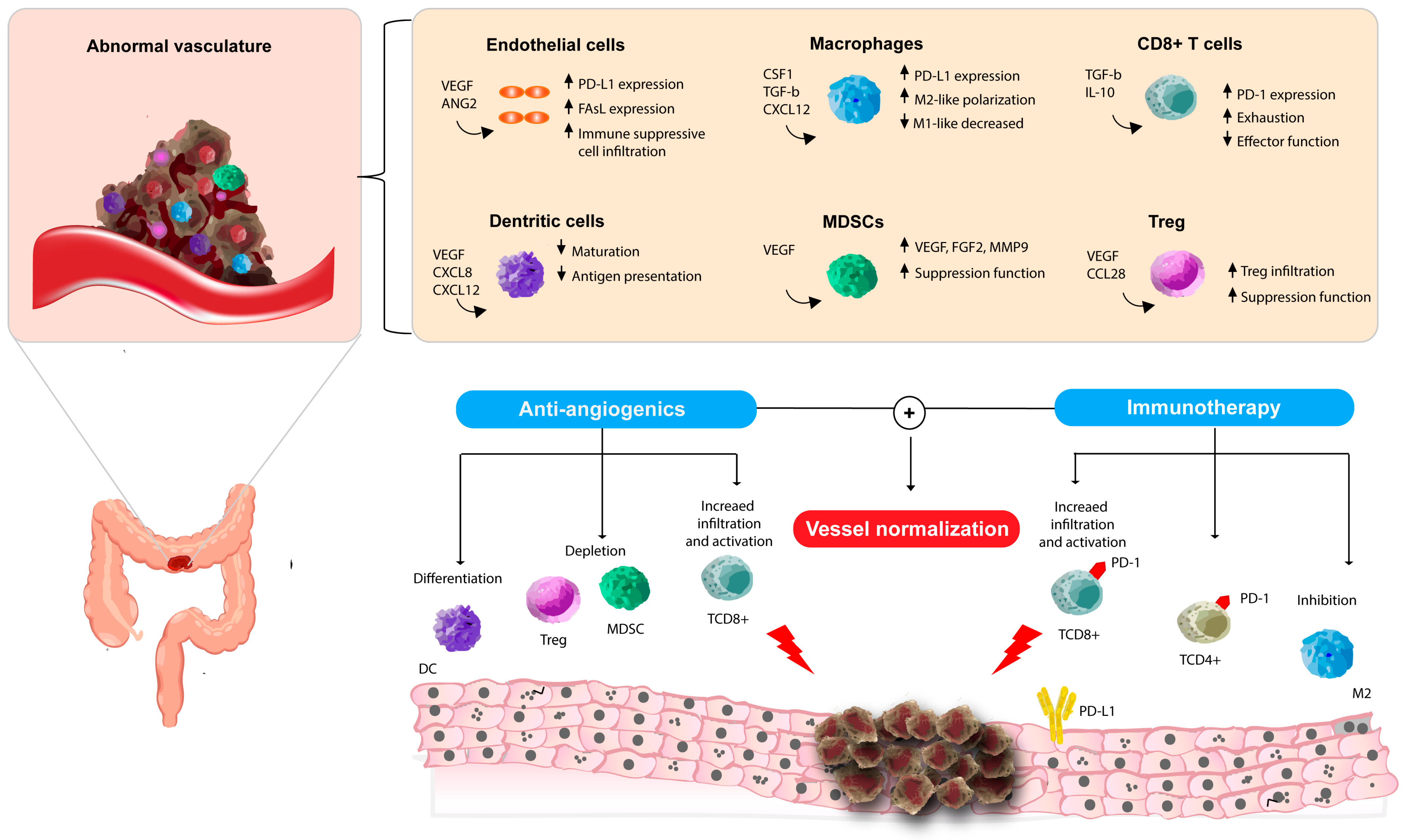

2.2. The Crosstalk Between Angiogenesis and Immune System

3. Current Landscape of Anti-Angiogenetic Treatments in Metastatic CRC

3.1. Anti-Angiogenetic in First-Line Therapy

3.2. Maintenance

3.3. Second Line

3.4. Beyond Second-Line Treatment

4. Looking to the Future

4.1. New Treatment Goals in CRC

4.2. Immunotherapy and Anti-Angiogenics

4.3. Targeting Angiogenesis Through a New Generation Molecule

5. Identification of Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers During Anti-Angiogenic Treatment

6. Cost-Effectiveness of Anti-Angiogenic Treatment

7. Expert Opinion and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BRAF | v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B |

| BSC | Best supportive care |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 |

| CXCL9/10 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 9/10 |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| DOR | Duration of response |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ECs | Endothelial cells |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EN-RAGE | Extracellular newly identified receptor for advanced glycation end-products binding protein |

| ESMO | European Society for Medical Oncology |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FGF-2 | Fibroblast growth factor-2 |

| FGFR | Fibroblast growth factor receptor |

| FOLFIRI | 5-Fluorouracil + leucovorin + irinotecan |

| FOLFOX | 5-Fluorouracil + leucovorin + oxaliplatin |

| FOLFOXIRI | 5-Fluorouracil + leucovorin + oxaliplatin + irinotecan |

| FU/LV | 5-Fluorouracil/leucovorin |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HGF | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| ICI(s) | Immune checkpoint inhibitor(s) |

| IL-8/IL-12/IL-18 | Interleukin-8/-12/-18 |

| INF-α/IFN-γ | Interferon-alpha/interferon-gamma |

| KD | (not used) |

| KIT | KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase |

| KRAS/NRAS | Kirsten rat sarcoma/neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog |

| LAG-3 | Lymphocyte activation gene-3 |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| mCRC | Metastatic colorectal cancer |

| mFOLFOX6 | Modified FOLFOX6 regimen |

| mOS | Median overall survival |

| mPFS | Median progression-free survival |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MVD | Microvascular density |

| MSS | Microsatellite atable |

| MSI/MSI-H | Microsatellite instability/microsatellite instability-high |

| mRNA | Messenger ribonucleic acid |

| NRP1/NRP2 | Neuropilin-1/neuropilin-2 |

| NSCLC | Non–small-cell lung cancer |

| ORR | Overall response rate |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death-1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PDGF(s) | Platelet-derived growth factor(s) |

| PDGFR-β | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PlGF | Placental growth factor |

| RAF | Rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma kinase family |

| RAS | Rat sarcoma viral oncogene family (KRAS/NRAS) |

| R0 | Microscopically margin-negative resection |

| RET | RET proto-oncogene |

| RR | Response rate |

| RTKs | Receptor tyrosine kinases |

| S-1 | Tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil (oral fluoropyrimidine) |

| TAM(s) | Tumor-associated macrophage(s) |

| TAS-102 | Trifluridine/Tipiracil |

| TCE | (not used) |

| TIE2 | TEK tyrosine kinase endothelial receptor 2 |

| TILs | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TIMP-1 | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 |

| TMB | Tumor mutational burden |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| Treg | Regulatory T cell |

| US | United States |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGF-A/-B/-C/-D | VEGF isoforms A/B/C/D |

| VEGFR-1/-2/-3 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1/-2/-3 |

| XELOX/CAPOX | Capecitabine + oxaliplatin |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat. Med. Nat. Publ. Group 2003, 9, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorak, H.F. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: A critical cytokine in tumor angiogenesis and a potential target for diagnosis and therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 4368–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurwitz, H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Novotny, W.; Cartwright, T.; Hainsworth, J.; Heim, W.; Berlin, J.; Baron, A.; Griffing, S.; Holmgren, E.; et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 2335–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Tabernero, J.; Lakomy, R.; Prenen, H.; Prausová, J.; Macarulla, T.; Ruff, P.; Van Hazel, A.; Moiseyenko, V.; Ferry, D.; et al. Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3499–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothey, A.; Van Cutsem, E.; Sobrero, A.; Siena, S.; Falcone, A.; Ychou, M.; Humblet, Y.; Bouché, O.; Mineur, L.; Barone, C.; et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): An international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, J.; Takayuki, Y.; Cohn, A.L. Ramucirumab versus placebo in combination with second-line FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma that progressed during or after first-line therapy with bevacizumab, oxaliplatin, and a fluoropyrimidine (RAISE): A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e262, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 499–508. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, J. Tumor angiogenesis: Therapeutic implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 1971, 285, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, G.; Febbraro, A.; Venditti, M.; Campidoglio, S.; Olivieri, N.; Raieta, K.; Parcesepe, P.; Imbriani, G.C.; Remo, A.; Pancione, M. Targeting angiogenesis and tumor microenvironment in metastatic colorectal cancer: Role of aflibercept. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2014, 2014, 526178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugano, R.; Ramachandran, M.; Dimberg, A. Tumor angiogenesis: Causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 1745–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampoli, K.; Foukas, P.G.; Ntavatzikos, A.; Arkadopoulos, N.; Koumarianou, A. Interrogating the interplay of angiogenesis and immunity in metastatic colorectal cancer. World J. Methodol. 2022, 12, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Kang, G.; Wang, T.; Huang, H. Tumor angiogenesis and anti-angiogenic gene therapy for cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 687–702. [Google Scholar]

- Zimna, A.; Kurpisz, M. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 in Physiological and Pathophysiological Angiogenesis: Applications and Therapies. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 549412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson-Welsh, L.; Welsh, M. VEGFA and tumour angiogenesis. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 273, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tian, T.; Zhang, J. Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) in Colorectal Cancer (CRC): From Mechanism to Therapy and Prognosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S.J.; Bates, D.O. VEGF-A splicing: The key to anti-angiogenic therapeutics? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Zhao, C.; Du, Y.; Lin, X.; Jiang, Y.; Lee, C.; Tian, G.; Mi, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Q.; et al. PDGF-CC underlies resistance to VEGF-A inhibition and combinatorial targeting of both suppresses pathologyical angiogenesis more efficiently. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 77902–77915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lopez, A.; Harada, K.; Vasilakopoulou, M.; Shanbhag, N.; Ajani, J.A. Targeting Angiogenesis in Colorectal Carcinoma. Drugs 2019, 79, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancopoulos, G.D.; Davis, S.; Gale, N.W.; Rudge, J.S.; Wiegand, S.J.; Holash, J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature 2000, 407, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, L.; Salem, M.E.; Mikhail, S. Biomarkers of Angiogenesis in Colorectal Cancer. Biomark. Cancer 2015, 7, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, N.; Gerber, H.-P.; LeCouter, J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.E.; Chen, H.H.; Winer, J.; Houck, K.A.; Ferrara, N. Placenta growth factor. Potentiation of vascular endothelial growth factor bioactivity, in vitro and in vivo, and high affinity binding to Flt-1 but not to Flk-1/KDR. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 25646–25654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Des Guetz, G.; Uzzan, B.; Nicolas, P.; Cucherat, M.; Morere, J.-F.; Benamouzig, R.; Breau, J.L.; Perret, G.Y. Microvessel density and VEGF expression are prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. Meta-analysis of the literature. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 94, 1823–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, J.; Byers, R.; Jayson, G.C. Intra-tumoural microvessel density in human solid tumours. Br. J. Cancer 2002, 86, 1566–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, C.; Mueller, B.; Brady, M.F.; Mannel, R.S.; Burger, R.A.; Wei, W.; Marien, K.M.; Kockx, M.M.; Husain, A.; Birrer, M.J. Tumor Microvessel Density as a Potential Predictive Marker for Bevacizumab Benefit: GOG-0218 Biomarker Analyses. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djx066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubb, A.M.; Hurwitz, H.I.; Bai, W.; Holmgren, E.B.; Tobin, P.; Guerrero, A.S.; Kabbinavar, F.; Holden, S.N.; Novotny, W.F.; Frantz, G.D.; et al. Impact of vascular endothelial growth factor-A expression, thrombospondin-2 expression, and microvessel density on the treatment effect of bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Ji, Y.R.; Lee, Y.M. Crosstalk between angiogenesis and immune regulation in the tumor microenvironment. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2022, 45, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.S.; Yang, H.; Chon, H.J.; Kim, C. Combination of anti-angiogenic therapy and immune checkpoint blockade normalizes vascular-immune crosstalk to potentiate cancer immunity. Exp. Mol. Med. Nat. Publ. Group 2020, 52, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, T.J.; Wei, S.; Dong, H.; Alvarez, X.; Cheng, P.; Mottram, P.; Krzysiek, R.; Knutson, K.L.; Daniel, B.; Zimmermann, M.C.; et al. Blockade of B7-H1 improves myeloid dendritic cell-mediated antitumor immunity. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, T.; Ran, S.; Ishida, T.; Nadaf, S.; Kerr, L.; Carbone, D.P.; Gabrilovich, I. Vascular endothelial growth factor affects dendritic cell maturation through the inhibition of nuclear factor-kappa B activation in hemopoietic progenitor cells. J. Immunol. 1998, 160, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohm, J.E.; Gabrilovich, D.I.; Sempowski, G.D.; Kisseleva, E.; Parman, K.S.; Nadaf, S.; Carbone, D.P. VEGF inhibits T-cell development and may contribute to tumor-induced immune suppression. Blood 2003, 101, 4878–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Jiao, D.; Qin, S.; Chu, Q.; Wu, K.; Li, A. Synergistic effect of immune checkpoint blockade and anti-angiogenesis in cancer treatment. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curiel, T.J.; Coukos, G.; Zou, L.; Alvarez, X.; Cheng, P.; Mottram, P.; Evdemon-Hogan, M.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Zhang, L.; Burow, M.; et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciabene, A.; Peng, X.; Hagemann, I.S.; Balint, K.; Barchetti, A.; Wang, L.-P.; Gimotty, P.A.; Gilks, C.B.; Lal, P.; Zhang, L.; et al. Tumour hypoxia promotes tolerance and angiogenesis via CCL28 and T(reg) cells. Nature 2011, 475, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, J.; Suzuki, H.; Fuchino, R.; Yamasaki, A.; Nagai, S.; Yanai, K.; Koga, K.; Nakamura, M.; Tanaka, M.; Morisaki, T.; et al. The contribution of vascular endothelial growth factor to the induction of regulatory T-cells in malignant effusions. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Dikov, M.M.; Novitskiy, S.V.; Mosse, C.A.; Yang, L.; Carbone, D.P. Distinct roles of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 in the aberrant hematopoiesis associated with elevated levels of VEGF. Blood 2007, 110, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varney, M.L.; Johansson, S.L.; Singh, R.K. Tumour-associated macrophage infiltration, neovascularization and aggressiveness in malignant melanoma: Role of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor-A. Melanoma Res. 2005, 15, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, R.K. Normalizing tumor vasculature with anti-angiogenic therapy: A new paradigm for combination therapy. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 987–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osada, T.; Chong, G.; Tansik, R.; Hong, T.; Spector, N.; Kumar, R.; Hurwitz, H.I.; Dev, I.; Nixon, A.B.; Lyerly, H.K.; et al. The effect of anti-VEGF therapy on immature myeloid cell and dendritic cells in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2008, 57, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terme, M.; Pernot, S.; Marcheteau, E.; Sandoval, F.; Benhamouda, N.; Colussi, O.; Dubreuil, O.; Carpentier, A.F.; Tartour, E.; Taieb, J. VEGFA-VEGFR pathway blockade inhibits tumor-induced regulatory T-cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmartsev, S.; Eruslanov, E.; Kübler, H.; Tseng, T.; Sakai, Y.; Su, Z.; Kaliberov, S.; Heiser, A.; Rosser, C.; Dahm, P.; et al. Oxidative stress regulates expression of VEGFR1 in myeloid cells: Link to tumor-induced immune suppression in renal cell carcinoma. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrelli, F.; Borgonovo, K.; Cabiddu, M.; Ghilardi, M.; Lonati, V.; Maspero, F.; Sauta, M.G.; Beretta, G.D.; Barni, S. FOLFIRI-bevacizumab as first-line chemotherapy in 3500 patients with advanced colorectal cancer: A pooled analysis of 29 published trials. Clin. Color. Cancer 2013, 12, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabbinavar, F.F.; Schulz, J.; McCleod, M.; Patel, T.; Hamm, J.T.; Hecht, J.R.; Mass, R.; Perrou, B.; Nelson, B.; Novotny, W.F. Addition of bevacizumab to bolus fluorouracil leucovorin in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer: Results of a randomized phase IItrial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3697–3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabbinavar, F.; Hurwitz, H.I.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Meropol, N.J.; Novotny, W.F.; Lieberman, G.; Griffing, S.; Bergsland, E. Phase II, randomized trial comparing bevacizumab plus fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) with FU/LV alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Ren, L.; Liu, T.; Ye, Q.; Wei, Y.; He, G.; Lin, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Liang, F.; et al. Bevacizumab Plus mFOLFOX6 Versus mFOLFOX6 Alone as First-Line Treatment for RAS Mutant Unresectable Colorectal Liver-Limited Metastases: The BECOME Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3175–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saltz, L.B.; Clarke, S.; Díaz-Rubio, E.; Scheithauer, W.; Figer, A.; Wong, R.; Koski, S.; Lichinitser, M.; Yang, T.S.; Rivera, F.; et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized phase III study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2013–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botrel, T.E.A.; Clark, L.G.d.O.; Paladini, L.; Clark, O.A.C. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab plus chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone in previously untreated advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tan, A.; Gao, F.; Liu, L.; Liao, C.; Mo, Z. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing chemotherapy plus bevacizumab with chemotherapy alone in metastatic colorectal cancer. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2009, 24, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Xu, W.S.; Liao, X.F.; He, H.J. Bevacizumab in combination with first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. Minerva Chir. 2015, 70, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hurwitz, H.I.; Tebbutt, N.C.; Kabbinavar, F.; Giantonio, B.J.; Guan, Z.-Z.; Mitchell, L.; Waterkamp, D.; Tabernero, J. Efficacy and Safety of Bevacizumab in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Pooled Analysis From Seven Randomized Controlled Trials. Oncologist 2013, 18, 1004–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loupakis, F.; Bria, E.; Vaccaro, V.; Cuppone, F.; Milella, M.; Carlini, P.; Cremolini, C.; Salvatore, L.; Falcone, A.; Muti, P.; et al. Magnitude of benefit of the addition of bevacizumab to first-line chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer: Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 29, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, S.; Spithoff, K.; Rumble, R.B.; Maroun, J.; Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site Group. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy for patients with advanced colorectal cancer: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.-Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, F.; Cao, J.; Xu, L.M. Value of bevacizumab in treatment of colorectal cancer: Ameta-analysis World. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 5072–5080. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, V.; Weikersthal, L.F.; von Decker, T.; Kiani, A.; Vehling-Kaiser, U.; Al-Batran, S.-E.; Heintges, T.; Lerchenmüller, C.; Kahl, C.; Seipelt, G.; et al. FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venook, A.P.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Lenz, H.-J.; Innocenti, F.; Fruth, B.; Meyerhardt, J.A.; Schrag, D.; Greene, C.; O’Neil, B.H.; Atkins, J.N.; et al. Effect of First-Line Chemotherapy Combined With Cetuximab or Bevacizumab on Overall Survival in Patients With KRAS Wild-Type Advanced or Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2017, 317, 2392–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartzberg, L.S.; Rivera, F.; Karthaus, M.; Fasola, G.; Canon, J.-L.; Hecht, J.R.; Yu, H.; Oliner, K.S.; Go, W.Y. PEAK: A randomized, multicenter phase II study of panitumumab plus modified fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6) or bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with previously untreated, unresectable, wild-type KRAS exon 2 metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2240–2247. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino, T.; Uetake, H.; Tsuchihara, K.; Shitara, K.; Yamazaki, K.; Oki, E.; Sato, T.; Naitoh, T.; Komatsu, Y.; Kato, T.; et al. Rationale for and Design of the PARADIGM Study: Randomized Phase III Study of mFOLFOX6 Plus Bevacizumab or Panitumumab in Chemotherapy-naïve Patients With RAS (KRAS/NRAS) Wild-type, Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2017, 16, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Denda, T.; Gamoh, M.; Iwanaga, I.; Yuki, S.; Shimodaira, H.; Nakamura, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ohori, H.; Kobayashi, K.; et al. S-1 and irinotecan plus bevacizumab versus mFOLFOX6 or CapeOX plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (TRICOLORE): A randomized, open-label, phase III, noninferiority trial. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruenberger, T.; Bridgewater, J.; Chau, I.; García Alfonso, P.; Rivoire, M.; Mudan, S.; Lasserre, S.; Hermann, F.; Waterkamp, D.; Adam, R. Bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX-6 or FOLFOXIRI in patients with initially unresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer: The OLIVIA multinational randomised phase II trial. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremolini, C.; Loupakis, F.; Antoniotti, C.; Lupi, C.; Sensi, E.; Lonardi, S.; Mezi, S.; Tomasello, G.; Ronzoni, M.; Zaniboni, A.; et al. FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Updated overall survival and molecular subgroup analyses of the open-label, phase 3 TRIBE study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremolini, C.; Antoniotti, C.; Stein, A.; Bendell, J.; Gruenberger, T.; Rossini, D.; Masi, G.; Ongaro, E.; Hurwitz, H.; Falcone, A.; et al. Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of FOLFOXIRI Plus Bevacizumab Versus Doublets Plus Bevacizumab as Initial Therapy of Unresectable Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 3314–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, D.; Lang, I.; Marcuello, E.; Lorusso, V.; Ocvirk, J.; Shin, D.B.; Jonker, D.; Osborne, S.; Andre, N.; Waterkamp, D.; et al. Bevacizumab plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in elderly patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer (AVEX): An open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holch, J.W.; Ricard, I.; Stintzing, S.; Modest, D.P.; Heinemann, V. The relevance of primary tumour location in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of first-line clinical trials. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 70, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantonio, F.; Fucà, G.; Rossini, D.; Schmoll, H.-J.; Bendell, J.C.; Morano, F.; Antoniotti, C.; Corallo, S.; Borelli, B.; Raimondi, A.; et al. FOLFOXIRI-Bevacizumab or FOLFOX-Panitumumab in Patients with Left-Sided RAS/BRAF Wild-Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Propensity Score-Based Analysis. Oncologist 2021, 26, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Folprecht, G.; Pericay, C.; Saunders, M.P.; Thomas, A.; Lopez Lopez, R.; Roh, J.K.; Chistyakov, V.; Höhler, T.; Kim, J.S.; Hofheinz, R.D.; et al. Oxaliplatin and 5-FU/folinic acid (modified FOLFOX6) with or without aflibercept in first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: The AFFIRM study. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeberle, D.; Betticher, D.C.; von Moos, R.; Dietrich, D.; Brauchli, P.; Baertschi, D.; Matter, K.; Winterhalder, R.; Borner, M.; Anchisi, S.; et al. Bevacizumab continuation versus no continuation after first-line chemotherapy plus bevacizumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A randomized phase III non-inferiority trial (SAKK 41/06). Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, T.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Boige, V.; Le Malicot, K.; Taieb, J.; Bouché, O.; Phelip, J.M.; François, E.; Borel, C.; Faroux, R.; et al. Bevacizumab Maintenance Versus No Maintenance During Chemotherapy-Free Intervals in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Randomized Phase III Trial (PRODIGE 9). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goey, K.K.H.; Elias, S.G.; van Tinteren, H.; Laclé, M.M.; Willems, S.M.; Offerhaus, G.J.A.; de Leng, W.W.J.; Strengman, E.; Ten Tije, A.J.; Creemers, G.M.; et al. Maintenance treatment with capecitabine and bevacizumab versus observation in metastatic colorectal cancer: Updated results and molecular subgroup analyses of the phase 3 CAIRO3 study. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2128–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegewisch-Becker, S.; Graeven, U.; Lerchenmüller, C.A.; Killing, B.; Depenbusch, R.; Steffens, C.-C.; Al-Batran, S.E.; Lange, T.; Dietrich, G.; Stoehlmacher, J.; et al. Maintenance strategies after first-line oxaliplatin plus fluoropyrimidine plus bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (AIO 0207): A randomised, non-inferiority, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1355–1369, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giantonio, B.J.; Catalano, P.J.; Meropol, N.J.; O’Dwyer, P.J.; Mitchell, E.P.; Alberts, S.R.; Schwartz, M.A.; Benson, A.B. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin fluorouracil leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: Results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 1539–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennouna, J.; Sastre, J.; Arnold, D.; Österlund, P.; Greil, R.; Van Cutsem, E.; von Moos, R.; Viéitez, J.M.; Bouché, O.; Borg, C.; et al. Continuation of bevacizumab after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (ML18147): A randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, G.; Salvatore, L.; Boni, L.; Loupakis, F.; Cremolini, C.; Fornaro, L.; Schirripa, M.; Cupini, S.; Barbara, C.; Safina, V.; et al. Continuation or reintroduction of bevacizumab beyond progression to first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: Final results of the randomized BEBYP trial. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, S.; Takahashi, T.; Tamagawa, H.; Nakamura, M.; Munemoto, Y.; Kato, T.; Hata, T.; Denda, T.; Morita, Y.; Inukai, M.; et al. FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as second-line therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer after first-line bevacizumab plus oxaliplatin-based therapy: The randomized phase III EAGLE study. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothey, A.; Flick, E.D.; Cohn, A.L.; Bekaii-Saab, T.S.; Bendell, J.C.; Kozloff, M.; Roach, N.; Mun, Y.; Fish, S.; Hurwitz, H.I. Bevacizumab exposure beyond first disease progression in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Analyses of the ARIES observational cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2014, 23, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, P.; Yilmaz, M.; Möller, S.; Zitnjak, D.; Krogh, M.; Petersen, L.N.; Poulsen, L.Ø.; Winther, S.B.; Thomsen, K.G.; Qvortrup, C. TAS-102 with or without bevacizumab in patients with chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer: An investigator-initiated, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 412–420. [Google Scholar]

- Tabernero, J.; Prager, G.W.; Fakih, M.; Ciardiello, F.; Van Cutsem, E.; Elez, E.; Cruz, F.M.; Wyrwicz, L.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Papai, Z.; et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil plus bevacizumab for third-line treatment of refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: The phase 3 randomized SUNLIGHTstudy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Qin, S.; Xu, R.; Yau, T.C.C.; Ma, B.; Pan, H.; Xu, J.; Bai, Y.; Chi, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Regorafenib plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CONCUR): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seidel, J.A.; Otsuka, A.; Kabashima, K. Anti-PD-1 and Anti-CTLA-4 Therapies in Cancer: Mechanisms of Action, Efficacy, and Limitations. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Le, D.T.; Uram, J.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Kemberling, H.; Eyring, A.D.; Skora, A.D.; Luber, B.S.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.; et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine. Mass. Med. Soc. 2015, 372, 2509–2520. [Google Scholar]

- Socinski, M.A.; Jotte, R.M.; Cappuzzo, F.; Orlandi, F.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Nogami, N.; Rodríguez-Abreu, D.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Thomas, C.A.; Barlesi, F.; et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 2288–2301. [Google Scholar]

- Bedke, J.; Albiges, L.; Capitanio, U.; Giles, R.H.; Hora, M.; Lam, T.B.; Ljungberg, B.; Marconi, L.; Klatte, T.; Volpe, A.; et al. Updated European Association of Urology Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma: Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib Joins Immune Checkpoint Inhibition Combination Therapies for Treatment-naïve Metastatic Clear-Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rini, B.I.; Plimack, E.R.; Stus, V.; Gafanov, R.; Hawkins, R.; Nosov, D.; Pouliot, F.; Alekseev, B.; Soulières, D.; Melichar, B.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, M. Scientific Rationale for Combined Immunotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 Antibodies and VEGF Inhibitors in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendell, J.C.; Powderly, J.D.; Lieu, C.H.; Eckhardt, S.G.; Hurwitz, H.; Hochster, H.S. Safety and efficacy of MPDL3280A (anti-PDL1) in combination with bevacizumab (bev) and/or FOLFOX in patients (pts) with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, J.; Pishvaian, M.J.; Hernandez, G.; Yadav, M.; Jhunjhunwala, S.; Delamarre, L.; Xian, H.e.; Powderly, J.; Lieu, C.; Eckhardt, S.; et al. Abstract 2651: Clinical activity and immune correlates from a phase Ib study evaluating atezolizumab (anti-PDL1) in combination with FOLFOX and bevacizumab (anti-VEGF) in metastatic colorectal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothey, A.; Tabernero, J.; Arnold, D.; Gramont, A.D.; Ducreux, M.P.; O’Dwyer, P.J. Fluoropyrimidine (FP) + bevacizumab (BEV) + atezolizumab vs FP/BEV in BRAFwt metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): Findings from Cohort 2 of MODUL—A multicentre, randomized trial of biomarker-driven maintenance treatment following first-line induction therapy. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, viii714–viii715. [Google Scholar]

- Tabernero, J.; Grothey, A.; Arnold, D.; de Gramont, A.; Ducreux, M.; O’Dwyer, P.; Tahiri, A.; Gilberg, F.; Irahara, N.; Schmoll, H.J.; et al. MODUL cohort 2: An adaptable, randomized, signal-seeking trial of fluoropyrimidine plus bevacizumab with or without atezolizumab maintenance therapy for BRAFwt metastatic colorectal cancer. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mettu, N.; Twohy, E.; Ou, F.-S.; Halfdanarson, T.; Lenz, H.; Breakstone, R.; Boland, P.M.; Crysler, O.; Wu, C.; Grothey, A.; et al. 533PDBACCI: A phase II randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study of capecitabine (C) bevacizumab (B) plus atezolizumab (A) or placebo (P) in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): An ACCRU network study. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, v203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitara, K.; Hara, H.; Takahashi, N.; Kojima, T.; Kawazoe, A.; Asayama, M.; Yoshii, T.; Kotani, D.; Tamura, H.; Mikamoto, Y.; et al. Updated results from a phase Ib trial of regorafenib plus nivolumab in patients with advanced colorectal or gastric cancer (REGONIVO, EPOC1603). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniotti, C.; Borelli, B.; Rossini, D.; Pietrantonio, F.; Morano, F.; Salvatore, L.; Lonardi, S.; Marmorino, F.; Tamberi, S.; Corallo, S.; et al. AtezoTRIBE: A randomised phase II study of FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab alone or in combination with atezolizumab as initial therapy for patients with unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, H.-J.; Parikh, A.R.; Spigel, D.R.; Cohn, A.L.; Yoshino, T.; Kochenderfer, M.D.; Elez, E.; Shao, S.H.; Deming, D.; Holdridge, R.; et al. Nivolumab (NIVO) + 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin/oxaliplatin (mFOLFOX6)/bevacizumab (BEV) versus mFOLFOX6/BEV for first-line (1L) treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): Phase 2 results from CheckMate 9X8. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damato, A.; Bergamo, F.; Antonuzzo, L.; Nasti, G.; Pietrantonio, F.; Tonini, G.; Romagnani, A.; Berselli, A.; Normanno, N.; Pinto, C. Phase II study of nivolumab in combination with FOLFOXIRI/bevacizumab as first-line treatment in patients with advanced colorectal cancer RAS/BRAFmutated (mut): NIVACORtrial (GOIRC-03-2018). J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, J.M.; Tsai, Y.-T.; Weinberg, B.A.; Donahue, R.N.; Gandhy, S.; Gatti-Mays, M.E.; Abdul Sater, H.; Bilusic, M.; Cordes, L.M.; Steinberg, S.M.; et al. A Randomized Phase II Trial of mFOLFOX6 + Bevacizumab Alone or with AdCEA Vaccine + Avelumab Immunotherapy for Untreated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Oncologist 2022, 27, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; He, M.-M.; Yao, Y.-C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z.-Q.; Jin, Y.; Luo, H.Y.; Li, J.B.; Wang, F.H.; Qiu, M.Z.; et al. Regorafenib plus toripalimab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: A phase Ib/II clinical trial and gut microbiome analysis. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirley, M. Fruquintinib: First Global Approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 1757–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Qin, S.; Xu, R.-H.; Shen, L.; Xu, J.; Bai, Y.; Yang, L.; Deng, Y.; Chen, Z.D.; Zhong, H.; et al. Effect of Fruquintinib vs Placebo on Overall Survival in Patients with Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The FRESCO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 319, 2486–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, N.A.; Lonardi, S.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Fernandez, M.E.E.; Yoshino, T.; Sobrero, A.F.; Yao, J.; García-Alfonso, P.; Kocsis, J.; Cubillo Gracian, A.; et al. LBA25 FRESCO-2: A global phase III multiregional clinical trial (MRCT) evaluating the efficacy and safety of fruquintinib in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, S1391–S1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loupakis, F.; Cremolini, C.; Fioravanti, A.; Orlandi, P.; Salvatore, L.; Masi, G.; Di Desidero, T.; Canu, B.; Schirripa, M.; Frumento, P.; et al. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenetic angiogenesis-related markers of first-line FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab schedule in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 104, 1262–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weickhardt, A.J.; Williams, D.S.; Lee, C.K.; Chionh, F.; Simes, J.; Murone, C.; Wilson, K.; Parry, M.M.; Asadi, K.; Scott, A.M.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor D expression is a potential biomarker of bevacizumab benefit in colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabernero, J.; Hozak, R.R.; Yoshino, T.; Cohn, A.L.; Obermannova, R.; Bodoky, G.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Ciuleanu, T.E.; Portnoy, D.C.; Prausová, J.; et al. Analysis of angiogenesis biomarkers for ramucirumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer from RAISE, a global, randomized, double-blind, phase III study. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, A.R.; Lee, F.-C.; Yau, L.; Koh, H.; Knost, J.; Mitchell, E.P.; Bosanac, I.; Choong, N.; Scappaticci, F.; Mancao, C.; et al. MAVERICC, a Randomized, Biomarker-stratified, Phase II Study of mFOLFOX6-Bevacizumab versus FOLFIRI-Bevacizumab as First-line Chemotherapy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2988–2995. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.O.; Catalano, P.J.; Symonds, K.E.; Varey, A.H.R.; Ramani, P.; O’Dwyer, P.J.; Giantonio, B.J.; Meropol, N.J.; Benson, A.B.; Harper, S.J.; et al. Association between VEGF Splice Isoforms and Progression-Free Survival in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated with Bevacizumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 6384–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, D.-S.; Li, C.; Jin, Y.; Wang, D.-S.; Chen, D.L.; Qiu, M.Z.; Luo, H.Y.; Wang, Z.Q.; et al. A plasma cytokine and angiogenic factor (CAF) analysis for selection of bevacizumab therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampieri, R.; Ziranu, P.; Daniele, B.; Zizzi, A.; Ferrari, D.; Lonardi, S.; Zaniboni, A.; Cavanna, L.; Rosati, G.; Casagrande, M.; et al. From CENTRAL to SENTRAL (SErum aNgiogenesis cenTRAL): Circulating Predictive Biomarkers to Anti-VEGFR Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1330. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.L. Hypoxia—A key regulatory factor in tumour growth. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scartozzi, M.; Giampieri, R.; Maccaroni, E.; Del Prete, M.; Faloppi, L.; Bianconi, M.; Galizia, E.; Loretelli, C.; Belvederesi, L.; Bittoni, A.; et al. Pre-treatment lactate dehydrogenase levels as predictor of efficacy of first-line bevacizumab-based therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 799–804. [Google Scholar]

- Passardi, A.; Scarpi, E.; Tamberi, S.; Cavanna, L.; Tassinari, D.; Fontana, A.; Pini, S.; Bernardini, I.; Accettura, C.; Ulivi, P.; et al. Impact of Pre-Treatment Lactate Dehydrogenase Levels on Prognosis and Bevacizumab Efficacy in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134732. [Google Scholar]

- Marmorino, F.; Salvatore, L.; Barbara, C.; Allegrini, G.; Antonuzzo, L.; Masi, G.; Loupakis, F.; Borelli, B.; Chiara, S.; Banzi, M.C.; et al. Serum LDH predicts benefit from bevacizumab beyond progression in metastatic colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, C.; Piro, G.; Simionato, F.; Ligorio, F.; Cremolini, C.; Loupakis, F.; Alì, G.; Rossini, D.; Merz, V.; Santoro, R.; et al. Homeobox B9 Mediates Resistance to Anti-VEGF Therapy in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4312–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonan, S.A.; Morrissey, M.E.; Martin, P.; Biniecka, M.; Ó’Meachair, S.; Maguire, A.; Tosetto, M.; Nolan, B.; Hyland, J.; Sheahan, K.; et al. Tumour vasculature immaturity, oxidative damage and systemic inflammation stratify survival of colorectal cancer patients on bevacizumab treatment. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 10536–10548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhan, J.; Niu, M.; Wang, P.; Zhu, X.; Li, S.; Song, J.; He, H.; Wang, Y.; Xue, L.; Fang, W.; et al. Elevated HOXB9 expression promotes differentiation and predicts a favourable outcome in colon adenocarcinoma patients. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 111, 883–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, E.; Biesma, H.D.; Cordes, M.; Smeets, D.; Neerincx, M.; Das, S.; Eijk, P.P.; Murphy, V.; Barat, A.; Bacon, O.; et al. Loss of Chromosome 18q11.2-q12.1 Is Predictive for Survival in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated With Bevacizumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2052–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, E.; van Werkhoven, E.; Asher, R.; Mooi, J.K.; Espinoza, D.; van Essen, H.F.; Eijk, P.P.; Murphy, V.; Barat, A.; Bacon, O.; et al. Predictive value of chromosome 18q11.2-q12.1 loss for benefit from bevacizumab in metastatic colorectal cancer: A post hoc analysis of the randomized phase III-trial AGITG-MAX. Int. J. Cancer 2022, 151, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisen, M.K.; Dehlendorff, C.; Linnemann, D.; Nielsen, B.S.; Larsen, J.S.; Østerlind, K.; Nielsen, S.E.; Tarpgaard, L.S.; Qvortrup, C.; Pfeiffer, P.; et al. Tissue MicroRNAs as Predictors of Outcome in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated with First Line Capecitabine and Oxaliplatin with or without Bevacizumab. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denda, T.; Sakai, D.; Hamaguchi, T.; Sugimoto, N.; Ura, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Fujii, H.; Kajiwara, T.; Nakajima, T.E.; Takahashi, S.; et al. Phase II trial of aflibercept with FOLFIRI as a second-line treatment for Japanese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 1032–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaguchi, T.; Denda, T.; Kudo, T.; Sugimoto, N.; Ura, T.; Yamazaki, K.; Fujii, H.; Kajiwara, T.; Nakajima, T.E.; Takahashi, S.; et al. Exploration of potential prognostic biomarkers in aflibercept plus FOLFIRI in Japanese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 3565–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.A.; Chen, Q.; Ayer, T.; Chan, K.K.W.; Virik, K.; Hammerman, A.; Brenner, B.; Flowers, C.R.; Hall, P.S. Bevacizumab for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Global Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Oncologist 2017, 22, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Giuliani, J.; Bonetti, A. First-line therapies in metastatic colorectal cancer: Integrating clinical benefit with the costs of drugs. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2018, 33, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Citation | Trial | N° pt | Treatment | Type of Trial | ORR | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hurwitz et al., NEJM 2004 [4] | AVF2107g | 813 | Irinotecan/leucovorin/fluorouracil + Bevacizumab/placebo | Phase III, blinded, randomized | 44.8% vs. 34.8% (p = 0.004) | 10.6 vs. 6.2 m (p < 0.001) | 20.3 vs. 15.6 m (p < 0.001) |

| Kabbinavar et al., JCO 2003 [43] | NA | 104 | Leucovorin/fluorouracil + placebo/Bevacizumab low dose/Bevacizumab high dose | Phase II, open-label, randomized | 17% vs. 40% vs. 24% | 5.2 vs. 9.0 vs. 7.2 m | 13.8 vs. 21.5 vs. 16.1 m |

| Kabbinavar et al., JCO 2005 [44] | NA | 209 | Leucovorin/fluorouracil + bevacizumab/placebo | Phase II, blinded, randomized | 26% vs. 15.2% (p = 0.055) | 9.2 vs. 5.5 m (p = 0.0002) | 16.6 vs. 12.9 m (p = 0.16) |

| Tang W et al., JCO 2020 [45] | BECOME | 241 | mFOLFOX6 +/− Bevacizumab | Phase IV, open-label, randomized | 54.5% vs. 36.7% (p < 0.01) | 9.5 vs. 5.6 m (p < 0.01) | 25.7 vs. 20.5 m (p = 0.03) |

| Saltz et al., JCO 2008 [46] | NO16966 | 1401 | XELOX/FOLFOX4 + bevacizumab/placebo | Phase III, blinded, randomized | 47% vs. 49% (p = 0.31) | 9.4 vs. 8 m (p = 0.0023) | 21.0 vs. 19.9 m (p = 0.077) |

| Schmiegel et al., Ann Oncol 2013 [8] | NA | 255 | Bevacizumab + Capox/mCapIri | Phase II, randomized, open-label | 53% vs. 56% | 10.4 vs. 12.1 m | 24.4 vs. 25.5 m |

| Heinemann V et al., Lancet Onc 2014 [54] | FIRE 3 | 592 | FOLFIRI + Cetuximab/Bevacizumab | Phase III, randomized, open-label | 62% vs. 58% (p = 0.18) | 10.0 vs. 10.3 m (p = 0.55) | 28.7 vs. 25.0 m (p = 0.017) |

| Venook et al., JAMA 2017 [55] | Calgb/Swog 80405 | 3058 (2334 KRAS WT) | FOLFIRI/mFOLFOX6 + cetuximab/bevacizumab | Phase III, randomized, open-label | 59.6% vs. 55.2% (p = 0.13) | 10.5 vs. 10.6 m (p = 0.45) | 30.0 vs. 29.0 m (p = 0.08) |

| Schwartzberg et al., JCO 2014 [56] | PEAK | 285 | mFOLFOX6 + panitumumab/bevacizumab | Phase II, randomized, open-label | 57.8% vs. 53.5% | 10.9 vs. 10.1 m (p = 0.353) | 34.2 vs. 24.3 m (p = 0.009) |

| Yamada et al., Ann Oncol 2018 [58] | TRICOLORE | 487 | mFOLFOX6/Capox + bevacizumab vs. S1 + Irinotecan + Bevacizumab | Phase III, randomized, open-label, non-inferiority | 70.6% vs. 66.4% (p = 0.34) | 10.8 vs. 14.0 m (p < 0.0001) | 33.6 vs. 34.9 m (p = 0.2841) |

| Gruenberger et al., Ann Oncol 2015 [59] | OLIVIA | 80 | Bevacizumab + mFOLFOX6/FOLFOXIRI | Phase II, randomized, open-label | 62% vs. 81% | 11.5 vs. 18.0 m (HR 0.43) | 32.2 vs. NR (HR 0.35) |

| Cremolini et al., Lancet Oncol 2015 [60] | TRIBE | 508 | Bevacizumab + FOLFIRI/FOLFOXIRI | Phase III, randomized, open-label | 54% vs. 65% (p = 0.013) | 9.7 vs. 12.3 m (p = 0.01) | 25.8 vs. 29.8 m (p = 0.03) |

| Cunningham et al., Lancet Oncol 2013 [62] | AVEX | 280 | Capecitabine +/− Bevacizumab | Phase III, randomized, open-label | 9.1 vs. 5.1 m (p < 0.0001) | 20.7 vs. 17.0 m (p = 0.13) |

| Citation | Trial | N° pt | Treatment | Type of Trial | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koeberle et al., Ann Oncol 2015 [66] | SAKK 41/06 | 262 | Bevacizumab vs. no treatment | Phase III, randomized, open-label | 4.1 vs. 2.9 m (TTP) | 25.4 vs. 23.8 m (p = 0.2) |

| Aparicio et al., JCO 2018 [67] | PRODIGE 9 | 491 | Bevacizumab vs. no treatment | Phase III, randomized, open-label | 9.2 vs. 8.9 m (p = 0.316) | 21.7 vs. 22.0 m (p = 0.5) |

| Goey et al., Ann Oncol 2017 [68] | CAIRO 3 | 558 | Capecitabine/Bevacizumab vs. no treatment | Phase III, randomized, open-label | 8.5 vs. 4.1 m (p < 0.0001) | 21.6 vs. 18.2 (p = 0.1) |

| Hegewisch-Becker et al., Lancet Oncol 2015 [69] | AIO 0207 | 472 | 5FU/Bevacizumab vs. Bevacizumab vs. no treatment | Phase III, randomized, open-label, non-inferiority | 6.3 vs. 4.6 vs. 3.5 m (p < 0.0001) | 20.2 vs. 21.9 vs. 23.1 (p = 0.77) |

| Citation | Trial | N° pt | Treatment | Type of Trial | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giantonio et al., JCO 2007 [70] | E3200 | 829 | FOLFOX4/Bevacizumab vs. FOLFOX4 vs. Bevacizumab | Phase III, open-label, randomized | 7.3 vs. 4.7 vs. 2.7 m (p < 0.0001) | 12.9 vs. 10.8 vs. 10.2 (p = 0.0011) |

| Bennouna et al., Lancet 2013 [71] | ML18147 | 409 | Chemotherapy +/− Bevacizumab | Phase III, open-label, randomized | 5.7 vs. 4.1 m (p < 0.0001) | 11.2 vs. 9.8 m (p = 0.0062) |

| Masi et al., Ann Oncol 2015 [72] | BEBYP | 185 | Chemotherapy +/− Bevacizumab | Phase III, open-label, randomized | 6.8 vs. 5.0 m (p = 0.010) | 15.5 vs. 14.1 m (p = 0.043) |

| Iwamoto et al., Ann Oncol 2015 [73] | EAGLE | 387 | FOLFIRI + Bevacizumab 5/10 mg/kg | Phase III, open-label, randomized | 6.1 vs. 6.4 m (p = 0.676) | 16.3 vs. 17.0 m (p = 0.667) |

| Van Cutsem et al., JCO 2012 [5] | VELOUR | 1226 | FOLFIRI + Aflibercept/placebo | Phase III, double-blind, randomized | 6.9 vs. 4.67 m (p < 0.0001) | 13.05 vs. 12.06 m (p = 0.0032) |

| Tabernero et al., Lancet Oncol 2015 [7] | RAISE | 1072 | FOLFIRI + Ramucirumab/placebo | Phase III, double-blind, randomized | 5.7 vs. 4.5 m (p = 0.0005) | 13.3 vs. 11.7 m (p = 0.0219) |

| Citation | Trial | N° pt | Treatment | Type of Trial | PFS | OS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pfeiffer et al., Lancet Oncol 2020 [75] | NA | 93 | TAS-102 +/− Bevacizumab | Phase II, open-label, randomized | 4.6 vs. 2.6 m (p = 0.0010) | 9.4 vs. 6.7 m (p = 0.028) |

| Tabernero et al., JCO suppl 2023 [76] | SUNLIGHT | 492 | TAS-102 +/− Bevacizumab | Phase III, open-label, randomized | 5.6 vs. 2.4 m (p < 0.001) | 10.8 vs. 7.5 m (p < 0.001) |

| Grothey et al., Lancet 2013 [6] | CORRECT | 760 | Regorafenib/placebo | Phase III, quadruple masking, randomized | 1.9 vs. 1.7 m (p < 0.0001) | 6.4 vs. 5.0 m (p = 0.0052) |

| Li et al., Lancet Oncol 2015 [77] | CONCUR | 204 | BSC +/− Regorafenib | Phase III, double-blind, randomized | 3.2 vs. 1.7 m (p < 0.0001) | 8.8 vs. 6.3 m (p = 0·00016) |

| Trial | Phase | Years | N. of pts | Treatment | mPFS | mOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01633970 | Ib | December 2014 through April 2017 | Arm A (pre-treated): 13 Arm B (naïve): 26 | Arm A: atezolizumab + bevacizumab Arm B: atezolizumab + FOLFOX + bevacizumab | NA | NA |

| MODUL (NCT02291289) | II | April 2015 through July 2019 | 445 (naïve, BRAF wt) | Maintenance bevacizumab +/− atezolizumab after FOLFOX + bevacizumab | Not met | NA |

| BACCI (NCT02873195) | II | September 2017 through June 2018 | 133 (pre-treated) | Capecitabine and bevacizumab + atezolizumab/placebo | 4.4 vs. 3.6 mo | NA |

| NCT03239145 | Ib | 18 (MSS, pre-treated) | Pembrolizumab + trebananib | NA | 9 mo | |

| NCT03946917 | Ib/II | March 2019 through January 2020 | 42 (MSS pre-treated) | Toripalimab + regorafenib | 2.1 mo | 15.5 mo |

| LEAP-005 (NCT03797326) | II | 2019–2020 | 32 (MSS, pre-treated) | Pembrolizumab + lenvatinib | 2.3 mo | 7.5 mo |

| NCT04126733 | II | October 2019 through January 2020 | 70 (MSS, pre-treated) | Nivolumab + regorafenib | 15 weeks | 52 weeks |

| REGOMUNE (NCT03475953) | II | November 2018 through October 2019 | 48 (MSS, pre-treated) | Avelumab + regorafenib | 3.6 mo | 10.8 mo |

| CheckMate 9X8 (NCT03414983) | II | February 2018 through April 2019 | Experimental Arm: 127 Control Arm:68 | Experimental Arm: FOLFOX + Bevacizumab + Nivolumab Control Arm: FOLFOX + Bevacizumab | 11.9 mo in both arms | Immature data |

| Atezo TRIBE (NCT03721653) | 2 | November 2018 through February 2020 | 218 (naïve) | FOLFOXIRI + bevacizumab +/− atezolizumab | 13.1 vs. 11.5 mo (p = 0.012) | NA |

| NIVACOR (NCT04072198) | 2 | October 2019 through March 2021 | 73 (naïve, RAS/BRAF mut) | FOLFOXIRI + bevacizumab + nivolumab | 10.1 mo | NA |

| NCT03396926 | 2 | April 2018 through October 2021 | 44 (MSS, pre-treated) | Pembrolizumab + capecitabine + bevacizumab | 4.3 mo | 9.6 mo |

| NCT03050814 | 2 | April 2017 through October 2019 | 26 (MSS, naïve) | mFOLFOX6 + bevacizumab +/− avelumab + CEA-targeted vaccine | No diff. | NA |

| NCT03712943 | 1b | November 2018 through September 2020 | 51 (MSS, pre-treated) | Nivolumab + regorafenib | 4.3 mo | 11.1 mo |

| NCT03657641 | 1/2 | July 2019 through July 2021 | 73 (MSS, pre-treated) | Pembrolizumab + regorafenib | 2.8 mo | 9.6 mo |

| Trial | Phase | Study Start | Setting | Treatment | Primary Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT05004441 | II | 2021 | First-line | FOLFOX/FOLFIRI, fruquintinib | ORR |

| NCT04296019, NCT05016869, NCT05451719, NCT04733963, NCT05659290 | II or I/II | 2021–2023 | Maintenance | Fruquintinib or fruquintinib plus capecitabine | PFS |

| NCT05634590 | II | 2022 | Second-line | FOLFOX/FOLFIRI, fruquintinib | PFS |

| NCT05555901 | II | 2023 | Second-line | FOLFIRI plus fruquintinib vs. FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab | PFS |

| NCT05522738 | Ib/II | 2022 | Second-line | FOLFIRI, fruquintinib | ORR |

| NCT05447715 | II | 2022 | Second-/Third-line | Fruquintinib sequential bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI vs. bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI sequential fruquintinib | PFS |

| NCT05004831 | II | 2022 | Third-line | Fruquintinib, trifluridine/tipiracil | PFS |

| NCT04695470 | II | 2020 | Pre-treated | Fruquintinib, sintilimab | PFS |

| NCT04582981 | II | 2020 | Pre-treated | Fruquintinib plus raltitrexed vs. fruquintinib | PFS |

| NCT04866862 | II | 2021 | Pre-treated | Fruquintinib, camrelizumab | ORR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Basile, D.; Di Nardo, P.; Daffinà, M.G.; Cortese, C.; Giuliani, J.; Aprile, G. The Current Role of Antiangiogenics in Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311605

Basile D, Di Nardo P, Daffinà MG, Cortese C, Giuliani J, Aprile G. The Current Role of Antiangiogenics in Colorectal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311605

Chicago/Turabian StyleBasile, Debora, Paola Di Nardo, Maria Grazia Daffinà, Carla Cortese, Jacopo Giuliani, and Giuseppe Aprile. 2025. "The Current Role of Antiangiogenics in Colorectal Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311605

APA StyleBasile, D., Di Nardo, P., Daffinà, M. G., Cortese, C., Giuliani, J., & Aprile, G. (2025). The Current Role of Antiangiogenics in Colorectal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11605. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311605