Traditional Health Practices May Promote Nrf2 Activation Similar to Exercise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

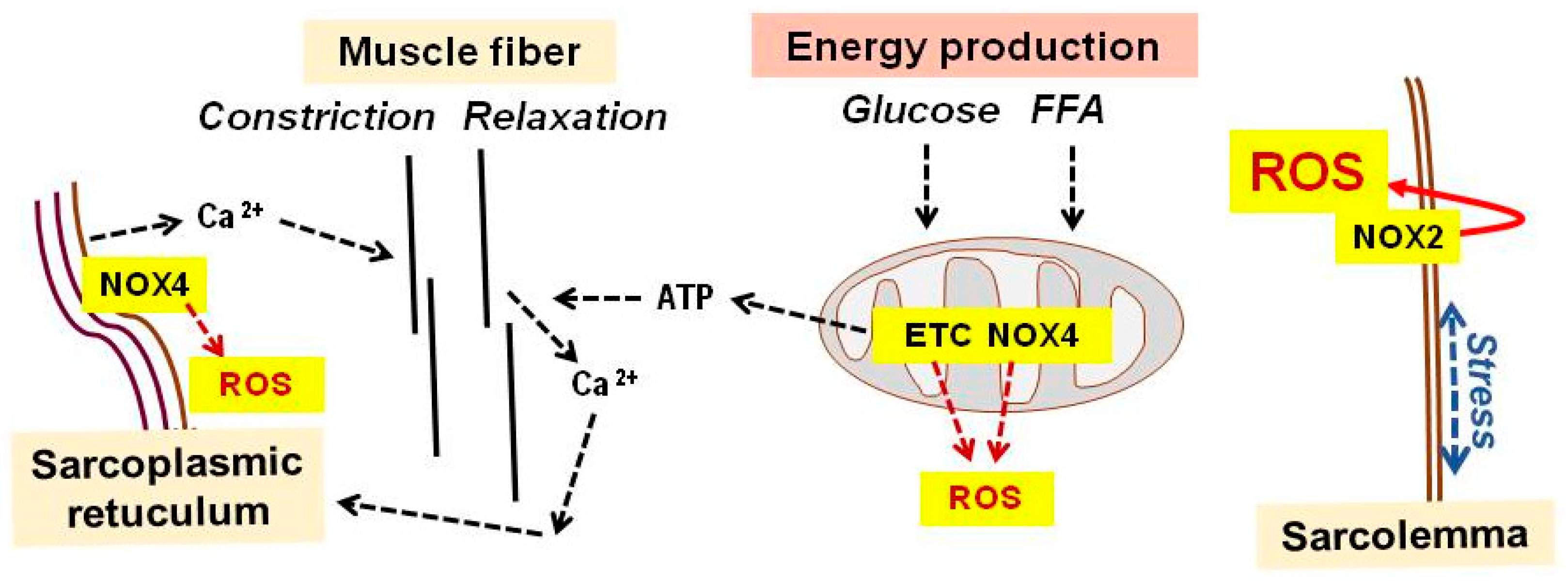

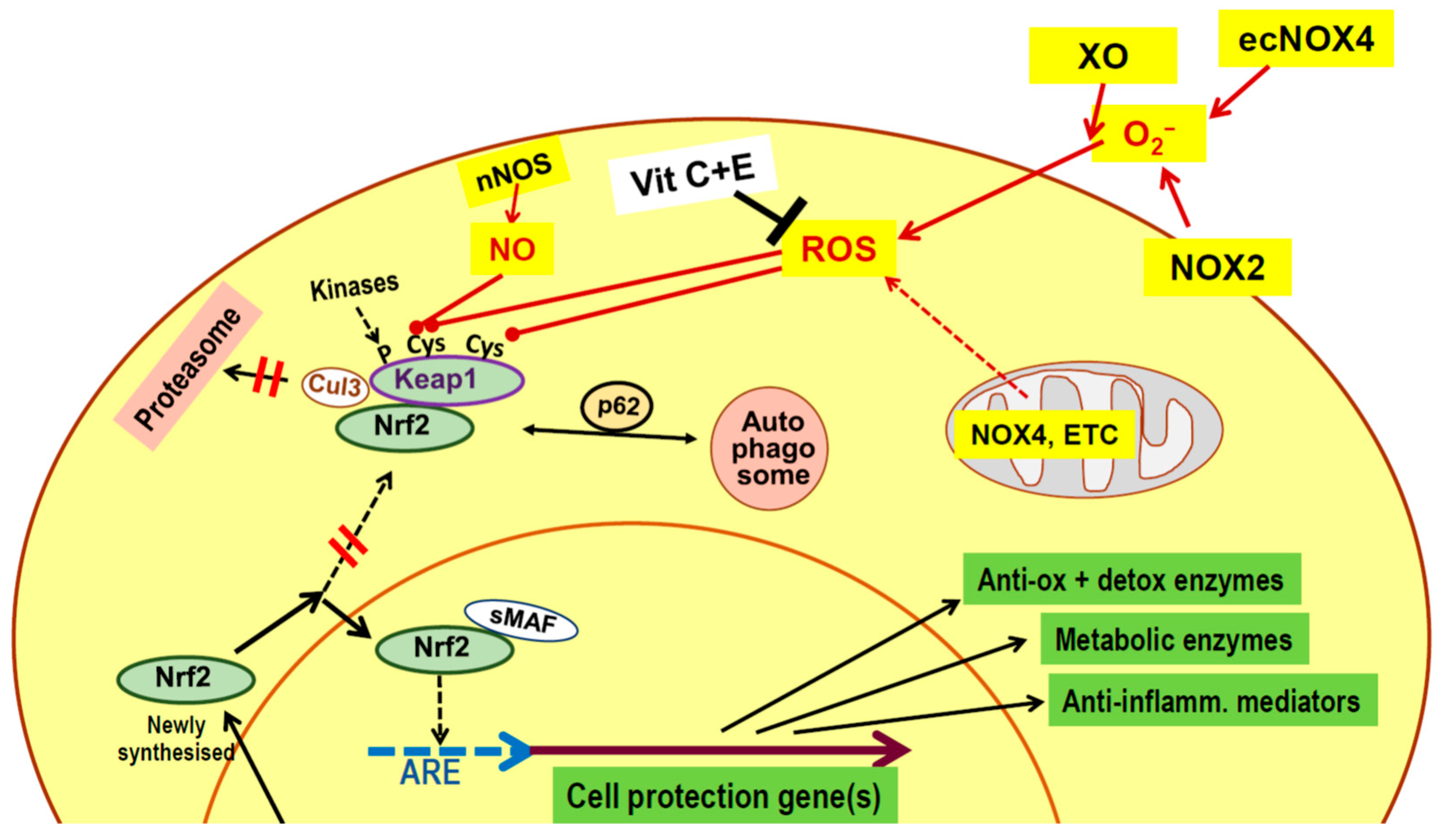

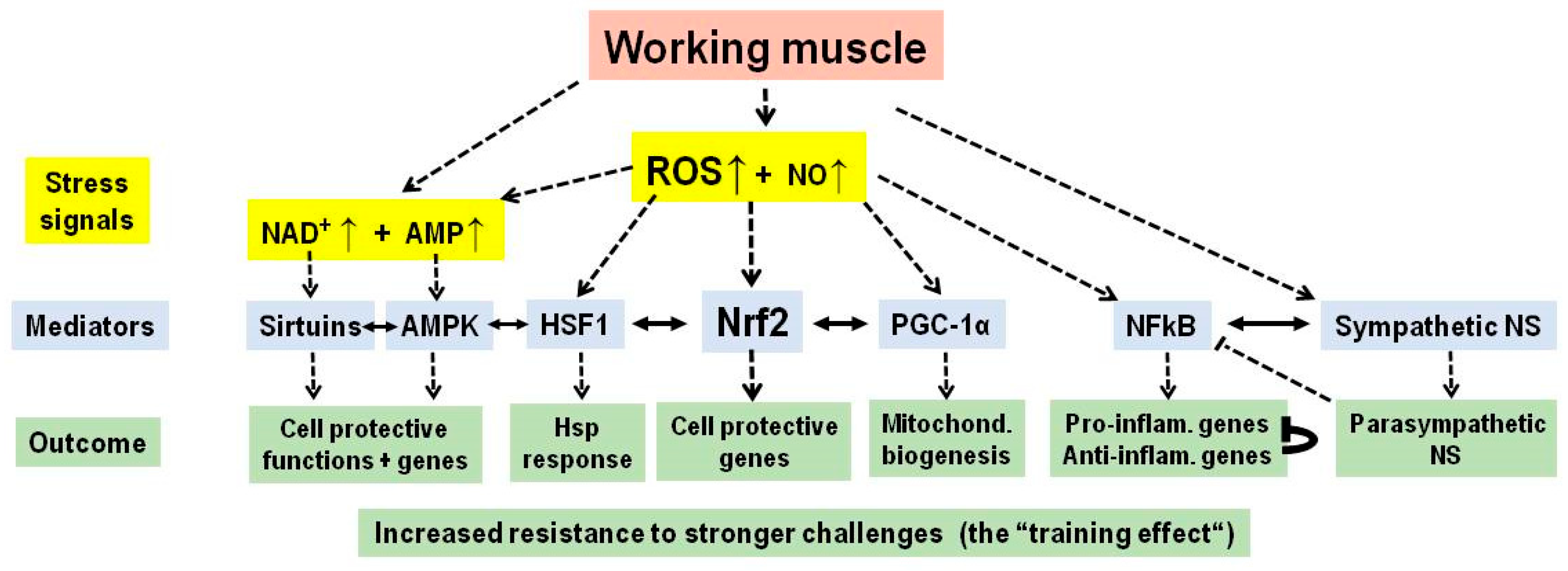

3. Physical Exercise

4. Heat or Cold Treatment

5. Hyper- or Hypobaric Oxygen Treatment

6. Fasting or Caloric Restriction

7. Dietary Polyphenols and Other Phenolics

8. Acupuncture

9. Cupping Therapy

10. Discussion

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADP | adenosine diphosphate |

| AMP | adenosine monophosphate |

| AMPK | adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| Anti-inflamm. | anti-inflammatory |

| Anti-ox | antioxidative |

| ARE | antioxidant response element |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| Cul3 | Cullin 3-based E3 ubiquitin ligase |

| detox | detoxifying |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| ecNOX4 | endothelial cell nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 4 |

| ETC | electron transfer chain |

| FFA | free fatty acids |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha |

| HSF1 | heat shock factor 1 |

| Hsp | heat shock protein |

| IL | interleukin |

| IL-1RA | interleukin-1 receptor antagonist |

| Inflam. | inflammatory |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1 |

| Mitochond. | mitochondrial |

| NAD+ | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NFκB | nuclear factor kappa light chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| nNOS | neuronal nitric oxide synthase |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NOS | nitric oxide synthase |

| NOX | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| NS | nervous system |

| PGC-1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 alpha |

| PNS | parasympathetic nervous system |

| p38 | protein 38 |

| p62 | protein 62 |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SH | sulfhydryl |

| sirtuin | silencing information regulator 2-related enzyme |

| sMAF | small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma protein |

| SNS | sympathetic nervous system |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| XO | xanthine oxidase |

| Vit | vitamin |

References

- Morris, J.N.; Heady, J.A.; Raffle, P.A.; Roberts, C.G.; Parks, J.W. Coronary heart-disease and physical activity of work. Lancet 1953, 262, 1111–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, F.W.; Roberts, C.K.; Laye, M.J. Lack of exercise is a major cause of chronic diseases. Compr. Physiol. 2012, 2, 1143–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, B.K.; Saltin, B. Exercise as medicine—Evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25 (Suppl. S3), 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoTrPAC Study Group. Temporal dynamics of the multi-omic response to endurance exercise training. Nature 2024, 629, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Tao, S.; Shao, M.; Huang, L.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, J.; Yao, R.; Sun, Z. Effectiveness of exercise training on arterial stiffness and blood pressure among postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2024, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; de Souto, B.P.; Arai, H.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Cadore, E.L.; Cesari, M.; Chen, L.K.; Coen, P.M.; Courneya, K.S.; Duque, G.; et al. Global consensus on optimal exercise recommendations for enhancing healthy longevity in older adults (ICFSR). J. Nutr. Health Aging 2025, 29, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhao, W.; Li, C.; Tian, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhong, J.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. The effects of high-intensity interval training on cognitive performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 32082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, F.M.M.; Leite, N.C.; Borck, P.C.; Freitas-Dias, R.; Cnop, M.; Chacon-Mikahil, M.P.T.; Cavaglieri, C.R.; Marchetti, P.; Boschero, A.C.; Zoppi, C.C.; et al. Exercise training protects human and rodent beta cells against endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 1524–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, M.; Morys, J.; Malecki, A.; Nowacka-Chmielewska, M. Muscle-brain crosstalk mediated by exercise-induced myokines—Insights from experimental studies. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1488375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuti, A.; Raffaele, I.; Scuruchi, M.; Lui, M.; Muscara, C.; Calabro, M. Role and Functions of Irisin: A Perspective on Recent Developments and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, G.K.; Jackson, M.J.; Vasilaki, A. Redefining the major contributors to superoxide production in contracting skeletal muscle. The role of NAD(P)H oxidases. Free Radic. Res. 2014, 48, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.J.; Vasilaki, A.; McArdle, A. Cellular mechanisms underlying oxidative stress in human exercise. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 98, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriquez-Olguin, C.; Meneses-Valdes, R.; Kritsiligkou, P.; Fuentes-Lemus, E. From workout to molecular switches: How does skeletal muscle produce, sense, and transduce subcellular redox signals? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 209, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Goldstein, E.; Schrager, M.; Ji, L.L. Exercise Training and Skeletal Muscle Antioxidant Enzymes: An Update. Antioxidants 2022, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Radak, Z.; Ji, L.L.; Jackson, M. Reactive oxygen species promote endurance exercise-induced adaptations in skeletal muscles. J. Sport. Health Sci. 2024, 13, 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, J.K.; Gros, R. A century of exercise physiology: Key concepts in neural control of the circulation. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 124, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Vegas, A.; Campos, C.A.; Contreras-Ferrat, A.; Casas, M.; Buvinic, S.; Jaimovich, E.; Espinosa, A. ROS Production via P2Y1-PKC-NOX2 Is Triggered by Extracellular ATP after Electrical Stimulation of Skeletal Muscle Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C.W.; Prosser, B.L.; Lederer, W.J. Mechanical stretch-induced activation of ROS/RNS signaling in striated muscle. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses-Valdes, R.; Gallero, S.; Henriquez-Olguin, C.; Jensen, T.E. Exploring NADPH oxidases 2 and 4 in cardiac and skeletal muscle adaptations—A cross-tissue comparison. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 223, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, M.S.; Napolitano, G.; Venditti, P. Mediators of Physical Activity Protection against ROS-Linked Skeletal Muscle Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, N.; Ivarsson, N.; Venckunas, T.; Neyroud, D.; Brazaitis, M.; Cheng, A.J.; Ochala, J.; Kamandulis, S.; Girard, S.; Volungevicius, G.; et al. Ryanodine receptor fragmentation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak after one session of high-intensity interval exercise. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15492–15497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shao, M.; Du, W.; Xu, Y. Impact of exhaustive exercise on autonomic nervous system activity: Insights from HRV analysis. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1462082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh-ishi, S.; Kizaki, T.; Ookawara, T.; Sakurai, T.; Izawa, T.; Nagata, N.; Ohno, H. Endurance training improves the resistance of rat diaphragm to exercise-induced oxidative stress. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997, 156, 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, H.K.; Powers, S.K.; Demirel, H.A.; Coombes, J.S.; Naito, H. Exercise training protects against contraction-induced lipid peroxidation in the diaphragm. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1999, 79, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.M.; Dasari, S.; Konopka, A.R.; Johnson, M.L.; Manjunatha, S.; Esponda, R.R.; Carter, R.E.; Lanza, I.R.; Nair, K.S. Enhanced Protein Translation Underlies Improved Metabolic and Physical Adaptations to Different Exercise Training Modes in Young and Old Humans. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, P.; Pan, X.F.; He, B.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, T. Acupuncture as an Adjunct to Lifestyle Interventions for Weight Loss in Simple Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 4319–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Spaulding, H.R. Extracellular superoxide dismutase, a molecular transducer of health benefits of exercise. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoy, Y.; Yapanoglu, T.; Aksoy, H.; Demircan, B.; Oztasan, N.; Canakci, E.; Malkoc, I. Effects of endurance training on antioxidant defense mechanisms and lipid peroxidation in testis of rats. Arch. Androl. 2006, 52, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela, F.S.; Malheiro, L.F.L.; Oliveira, C.A.; Merces, E.A.B.; De Benedictis, L.M.; De Benedictis, J.M.; Fernandes, A.J.V.; Silva, B.S.; Avila, J.S.; Correia, T.M.L.; et al. High-intensity interval training improves hepatic redox status via Nrf2 downstream pathways and reduced CYP2E1 expression in female rats with cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 196, 115234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merry, T.L.; Ristow, M. Nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-like 2 (NFE2L2, Nrf2) mediates exercise-induced mitochondrial biogenesis and the anti-oxidant response in mice. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 5195–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Domenech, E.; Romagnoli, M.; Arduini, A.; Borras, C.; Pallardo, F.V.; Sastre, J.; Vina, J. Oral administration of vitamin C decreases muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and hampers training-induced adaptations in endurance performance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristow, M.; Zarse, K.; Oberbach, A.; Kloting, N.; Birringer, M.; Kiehntopf, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Kahn, C.R.; Bluher, M. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8665–8670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.; Hughes, J.; Della Gatta, P.A.; Mason, S.; Lamon, S.; Russell, A.P.; Wadley, G.D. Vitamin C and E supplementation prevents some of the cellular adaptations to endurance-training in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, M.; Hafstad, A.D.; Nabeebaccus, A.A.; Catibog, N.; Logan, A.; Smyrnias, I.; Hansen, S.S.; Lanner, J.; Schroder, K.; Murphy, M.P.; et al. Myocardial NADPH oxidase-4 regulates the physiological response to acute exercise. eLife 2018, 7, e41044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacher, S.E.; Lee, J.S.; Wang, X.; Campbell, M.R.; Bell, D.A.; Slattery, M. Beyond antioxidant genes in the ancient Nrf2 regulatory network. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, C.; Liu, Q. Roles of NRF2 in DNA damage repair. Cell Oncol. (Dordr.) 2023, 46, 1577–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Du, H.; Shi, Y.; Xiu, M.; Liu, Y.; He, J. Natural products targeting Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Rourke, S.A.; Shanley, L.C.; Dunne, A. The Nrf2-HO-1 system and inflammaging. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1457010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, S.K.; Lategan-Potgieter, R.; Goldstein, E. Exercise-induced Nrf2 activation increases antioxidant defenses in skeletal muscles. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 224, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouviere, J.; Fortunato, R.S.; Dupuy, C.; Werneck-de-Castro, J.P.; Carvalho, D.P.; Louzada, R.A. Exercise-Stimulated ROS Sensitive Signaling Pathways in Skeletal Muscle. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, M.B.; Memme, J.M.; Oliveira, A.N.; Moradi, N.; Hood, D.A. Regulatory networks coordinating mitochondrial quality control in skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022, 322, C913–C926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, J.; Nakai, A.; Matsuda, K.; Komeda, M.; Ban, T.; Nagata, K. Reactive oxygen species play an important role in the activation of heat shock factor 1 in ischemic-reperfused heart. Circulation 1999, 99, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Atakan, M.M.; Kuang, J.; Hu, Y.; Bishop, D.J.; Yan, X. The Molecular Adaptive Responses of Skeletal Muscle to High-Intensity Exercise/Training and Hypoxia. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.R.; Jeong, K.J.; Mukae, M.; Lee, J.; Hong, E.J. Exercise promotes peripheral glycolysis in skeletal muscle through miR-204 induction via the HIF-1alpha pathway. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1487. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, H.T.; Rohm, M.; Goncalves, M.D.; Sylow, L. AMPK as a mediator of tissue preservation: Time for a shift in dogma? Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Luo, X.; Han, C.; Qin, Y.Y.; Pan, S.Y.; Qin, Z.H.; Bao, J.; Luo, L. NAD(+) homeostasis and its role in exercise adaptation: A comprehensive review. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 225, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, J.; Citherlet, T.; Camacho-Cardenosa, A.; Camacho-Cardenosa, M.; Raberin, A.; Krumm, B.; Hohenauer, E.; Egg, M.; Lichtblau, M.; Muller, J.; et al. Mechanisms underlying the health benefits of intermittent hypoxia conditioning. J. Physiol. 2024, 602, 5757–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Ortiz, K.; Perez-Vazquez, V.; Macias-Cervantes, M.H. Exercise and Sirtuins: A Way to Mitochondrial Health in Skeletal Muscle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Liu, D.; Jiang, S.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Essien, A.E.; Opoku, M.; Naranmandakh, S.; Liu, S.; et al. SIRT1 signaling pathways in sarcopenia: Novel mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 177, 116917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Y.; Shi, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, P.; Wu, D.; Shi, H. Exercise and exerkines: Mechanisms and roles in anti-aging and disease prevention. Exp. Gerontol. 2025, 200, 112685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, F.; Fabbrizi, E.; Mai, A.; Rotili, D. Activation and inhibition of sirtuins: From bench to bedside. Med. Res. Rev. 2025, 45, 484–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.M.; Pedersen, B.K. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 98, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Yan, W.; Yang, W.; Kamionka, A.; Lipowski, M.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, G. Effect of exercise on inflammatory markers in postmenopausal women with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 183, 112310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafi, M.; Symonds, M.E.; Faramarzi, M.; Sharifmoradi, K.; Maleki, A.H.; Rosenkranz, S.K. The effects of exercise training on inflammatory markers in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiol. Behav. 2024, 278, 114524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, I.; Coccurello, R. Irisin: A Multifaceted Hormone Bridging Exercise and Disease Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, D.D.L.; Latini, A. Exercise-induced immune system response: Anti-inflammatory status on peripheral and central organs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallard, A.R.; Spathis, J.G.; Coombes, J.S. Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) and exercise. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, S.; Niu, Y.; Fu, L. CSE/H(2)S/SESN2 Signalling Mediates the Protective Effect of Exercise Against Immobilization-Induced Muscle Atrophy in Mice. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2025, 16, e70083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Kozumbo, W.J. The phytoprotective agent sulforaphane prevents inflammatory degenerative diseases and age-related pathologies via Nrf2-mediated hormesis. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 163, 105283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flockhart, M.; Nilsson, L.C.; Tais, S.; Ekblom, B.; Apro, W.; Larsen, F.J. Excessive exercise training causes mitochondrial functional impairment and decreases glucose tolerance in healthy volunteers. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Deminice, R.; Ozdemir, M.; Yoshihara, T.; Bomkamp, M.P.; Hyatt, H. Exercise-induced oxidative stress: Friend or foe? J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunt, V.E.; Minson, C.T. Heat therapy: Mechanistic underpinnings and applications to cardiovascular health. J. Appl. Physiol. 2021, 130, 1684–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzey, F.K.; Smith, E.C.; Ruediger, S.L.; Keating, S.E.; Askew, C.D.; Coombes, J.S.; Bailey, T.G. The effect of heat therapy on blood pressure and peripheral vascular function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Exp. Physiol. 2021, 106, 1317–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laukkanen, J.A.; Kunutsor, S.K. The multifaceted benefits of passive heat therapies for extending the healthspan: A comprehensive review with a focus on Finnish sauna. Temperature 2024, 11, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, G.J.; Johnson, J.M. Adrenergic control of the human cutaneous circulation. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 34, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.M.; Minson, C.T.; Kellogg, D.L., Jr. Cutaneous vasodilator and vasoconstrictor mechanisms in temperature regulation. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 33–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greaney, J.L.; Kenney, W.L.; Alexander, L.M. Sympathetic regulation during thermal stress in human aging and disease. Auton. Neurosci. 2016, 196, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, R.P.; Johnson, T.L. Sauna use as a lifestyle practice to extend healthspan. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 154, 111509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, A.P.; Minett, G.M.; Gibson, O.R.; Kerr, G.K.; Stewart, I.B. Could Heat Therapy Be an Effective Treatment for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases? A Narrative Review. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.N.; Killen, L.G.; O’Neal, E.K.; Waldman, H.S. The Cardiometabolic Health Benefits of Sauna Exposure in Individuals with High-Stress Occupations. A Mechanistic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchant, E.D.; Nelson, W.B.; Hyldahl, R.D.; Gifford, J.R.; Hancock, C.R. Passive heat stress induces mitochondrial adaptations in skeletal muscle. Int. J. Hyperth. 2023, 40, 2205066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laukkanen, T.; Lipponen, J.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Zaccardi, F.; Araujo, C.G.S.; Makikallio, T.H.; Khan, H.; Willeit, P.; Lee, E.; Poikonen, S.; et al. Recovery from sauna bathing favorably modulates cardiac autonomic nervous system. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 45, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, B.K.; Castellani, J.W.; Charkoudian, N. Cold-induced cutaneous vasoconstriction in humans: Function, dysfunction and the distinctly counterproductive. Exp. Physiol. 2019, 104, 1202–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Lehoczki, A.; Laukkanen, J.A. The untapped potential of cold water therapy as part of a lifestyle intervention for promoting healthy aging. Geroscience 2025, 47, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, C.M.; Davison, G.W. What is the biochemical and physiological rationale for using cold-water immersion in sports recovery? A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2010, 44, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eimonte, M.; Paulauskas, H.; Daniuseviciute, L.; Eimantas, N.; Vitkauskiene, A.; Dauksaite, G.; Solianik, R.; Brazaitis, M. Residual effects of short-term whole-body cold-water immersion on the cytokine profile, white blood cell count, and blood markers of stress. Int. J. Hyperth. 2021, 38, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cain, T.; Brinsley, J.; Bennett, H.; Nelson, M.; Maher, C.; Singh, B. Effects of cold-water immersion on health and wellbeing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmierczyk, J.; Wiecek, M.; Wojciak, G.; Mardyla, M.; Kreiner, G.; Szygula, Z.; Szymura, J. The Effect of Physical Activity and Repeated Whole-Body Cryotherapy on the Expression of Modulators of the Inflammatory Response in Mononuclear Blood Cells among Young Men. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siems, W.G.; Brenke, R.; Sommerburg, O.; Grune, T. Improved antioxidative protection in winter swimmers. QJM 1999, 92, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubkowska, A.; Dolegowska, B.; Szygula, Z. Whole-body cryostimulation--potential beneficial treatment for improving antioxidant capacity in healthy men--significance of the number of sessions. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Li, C.S.; Hua, R.; Zhao, H.; Tang, Z.R.; Mei, X.; Zhang, M.Y.; Cui, J. Mild hypothermia attenuates mitochondrial oxidative stress by protecting respiratory enzymes and upregulating MnSOD in a pig model of cardiac arrest. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciak, G.; Szymura, J.; Szygula, Z.; Gradek, J.; Wiecek, M. The Effect of Repeated Whole-Body Cryotherapy on Sirt1 and Sirt3 Concentrations and Oxidative Status in Older and Young Men Performing Different Levels of Physical Activity. Antioxidants 2020, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.H.; Lee, T.K.; Kim, D.W.; Shin, M.C.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, J.C.; Tae, H.J.; Park, J.H.; Hong, S.; Lee, C.H.; et al. Therapeutic Hypothermia after Cardiac Arrest Attenuates Hindlimb Paralysis and Damage of Spinal Motor Neurons and Astrocytes through Modulating Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling Pathway in Rats. Cells 2023, 12, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowski, R.; Mila-Kierzenkowska, C.; Pawlowska, M.; Szewczyk-Golec, K.; Saletnik, L.; Sutkowy, P.; Wozniak, A. The Influence of Winter Swimming on Oxidative Stress Indicators in the Blood of Healthy Males. Metabolites 2023, 13, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, N.; Park, J.; Lim, K. The effects of exercise and cold exposure on mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue. J. Exerc. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 21, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shute, R.J.; Heesch, M.W.; Zak, R.B.; Kreiling, J.L.; Slivka, D.R. Effects of exercise in a cold environment on transcriptional control of PGC-1alpha. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2018, 314, R850–R857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.; Koch, A.K.; Cramer, H.; Linde, K.; Rotter, G.; Teut, M.; Brinkhaus, B.; Haller, H. Clinical effects of Kneipp hydrotherapy: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmann, J.; Kamolz, L.; Graier, W.; Smolle, J.; Smolle-Juettner, F.M. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy and Tissue Regeneration: A Literature Survey. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Duan, R.; Sun, Y.; Li, Q. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for healthy aging: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Redox Biol. 2022, 53, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Rathored, J. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: Future prospects in regenerative therapy and anti-aging. Front. Aging 2024, 5, 1368982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alva, R.; Mirza, M.; Baiton, A.; Lazuran, L.; Samokysh, L.; Bobinski, A.; Cowan, C.; Jaimon, A.; Obioru, D.; Al, M.T.; et al. Oxygen toxicity: Cellular mechanisms in normobaric hyperoxia. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2023, 39, 111–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveque, C.; Mrakic, S.S.; Theunissen, S.; Germonpre, P.; Lambrechts, K.; Vezzoli, A.; Bosco, G.; Levenez, M.; Lafere, P.; Guerrero, F.; et al. Oxidative Stress Response Kinetics after 60 Minutes at Different (1.4 ATA and 2.5 ATA) Hyperbaric Hyperoxia Exposures. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schottlender, N.; Gottfried, I.; Ashery, U. Hyperbaric Oxygen Treatment: Effects on Mitochondrial Function and Oxidative Stress. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.T.; Yang, Y.L.; Chang, W.H.; Fang, W.Y.; Huang, S.H.; Chou, S.H.; Lo, Y.C. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Improves Parkinson’s Disease by Promoting Mitochondrial Biogenesis via the SIRT-1/PGC-1alpha Pathway. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, B.U.; Nakanishi, R.; Tanaka, M.; Lin, H.; Hirabayashi, T.; Maeshige, N.; Kondo, H.; Fujino, H. Mild Hyperbaric Oxygen Exposure Enhances Peripheral Circulatory Natural Killer Cells in Healthy Young Women. Life 2023, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratantonio, D.; Virgili, F.; Zucchi, A.; Lambrechts, K.; Latronico, T.; Lafere, P.; Germonpre, P.; Balestra, C. Increasing Oxygen Partial Pressures Induce a Distinct Transcriptional Response in Human PBMC: A Pilot Study on the “Normobaric Oxygen Paradox”. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, D.; Lundby, C. Effects of Exercise Training in Hypoxia Versus Normoxia on Vascular Health. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, T.; Bielitzki, R.; Behrens, M.; Herold, F.; Schega, L. Effects of Intermittent Hypoxia-Hyperoxia on Performance- and Health-Related Outcomes in Humans: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Open 2022, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timon, R.; Martinez-Guardado, I.; Brocherie, F. Effects of Intermittent Normobaric Hypoxia on Health-Related Outcomes in Healthy Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. Open 2023, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panza, G.S.; Burtscher, J.; Zhao, F. Intermittent hypoxia: A call for harmonization in terminology. J. Appl. Physiol. 2023, 135, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham, P.B., III; Raju, R. Mitochondrial function in hypoxic ischemic injury and influence of aging. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 157, 92–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi; Singh, J. Redox imbalance and hypoxia-inducible factors: A multifaceted crosstalk. FEBS J. 2025, 292, 3833–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.D. Programmed longevity, youthspan, and juventology. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, C.L.; Lamming, D.W.; Fontana, L. Molecular mechanisms of dietary restriction promoting health and longevity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L. Interventions to promote cardiometabolic health and slow cardiovascular ageing. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Walker, B.R.; Ikuta, T. Systematic review and meta-analysis reveals acutely elevated plasma cortisol following fasting but not less severe calorie restriction. Stress 2016, 19, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L.; Verde, L.; Camajani, E.; Sojat, A.S.; Marina, L.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A.; Caprio, M.; Muscogiuri, G. Effects of very low-calorie ketogenic diet on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2023, 46, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoll, R.; Henein, M.Y. Caloric Restriction and Its Effect on Blood Pressure, Heart Rate Variability and Arterial Stiffness and Dilatation: A Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lettieri, B.D.; Tatulli, G.; Aquilano, K.; Ciriolo, M.R. Mitochondrial Hormesis links nutrient restriction to improved metabolism in fat cell. Aging 2015, 7, 869–881, Erratum in Aging 2016, 8, 1571. [Google Scholar]

- Kasai, S.; Shimizu, S.; Tatara, Y.; Mimura, J.; Itoh, K. Regulation of Nrf2 by Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species in Physiology and Pathology. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Kozumbo, W.J. The hormetic dose-response mechanism: Nrf2 activation. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 167, 105526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.; Kempf, K.; Rohling, M.; Lenzen-Schulte, M.; Schloot, N.C.; Martin, S. Ketone bodies: From enemy to friend and guardian angel. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmansi, A.M.; Kassem, A.; Castilla, R.M.; Miller, R.A. Downregulation of the NF-kappaB protein p65 is a shared phenotype among most anti-aging interventions. Geroscience 2024, 47, 3077–3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.; Lautrup, S.; Fang, E.F. NAD+ Boosting Strategies. Subcell. Biochem. 2024, 107, 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Kittana, M.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Stojanovska, L. The Role of Calorie Restriction in Modifying the Ageing Process through the Regulation of SIRT1 Expression. Subcell. Biochem. 2024, 107, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saeedi, B.J.; Liu, K.H.; Owens, J.A.; Hunter-Chang, S.; Camacho, M.C.; Eboka, R.U.; Chandrasekharan, B.; Baker, N.F.; Darby, T.M.; Robinson, B.S.; et al. Gut-Resident Lactobacilli Activate Hepatic Nrf2 and Protect Against Oxidative Liver Injury. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Mattson, M.P. The catabolic—Anabolic cycling hormesis model of health and resilience. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 102, 102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholampoor, N.; Sharif, A.H.; Mellor, D. The effect of observing religious or faith-based fasting on cardiovascular disease risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, M.; Abdelrahim, D.N.; El Herrag, S.E.; Khaled, M.B.; Shihab, K.A.; AlKurd, R.; Madkour, M. Cardiometabolic and obesity risk outcomes of dawn-to-dusk, dry intermittent fasting: Insights from an umbrella review. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2025, 67, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del, R.D.; Rodriguez-Mateos, A.; Spencer, J.P.; Tognolini, M.; Borges, G.; Crozier, A. Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: Structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1818–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, J.; Ojcius, D.M.; Ko, Y.F.; Ke, P.Y.; Wu, C.Y.; Peng, H.H.; Young, J.D. Hormetic Effects of Phytochemicals on Health and Longevity. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 30, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Luo, J.; Zhu, Y.; An, P.; Luo, Y.; Xing, Q. The Effect of Antioxidant Polyphenol Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotito, S.B.; Frei, B. Consumption of flavonoid-rich foods and increased plasma antioxidant capacity in humans: Cause, consequence, or epiphenomenon? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 1727–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, H.; Kempf, K.; Martin, S. Health Effects of Coffee: Mechanism Unraveled? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, M.; Aggett, P.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Dusemund, B.; Filipic, M.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; et al. Scientific opinion on the safety of green tea catechins. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldiken, B.; Ozkan, G.; Catalkaya, G.; Ceylan, F.D.; Ekin, Y.I.; Capanoglu, E. Phytochemicals of herbs and spices: Health versus toxicological effects. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 119, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbling, L.; Herbacek, I.; Weiss, R.M.; Jantschitsch, C.; Micksche, M.; Gerner, C.; Pangratz, H.; Grusch, M.; Knasmuller, S.; Berger, W. Hydrogen peroxide mediates EGCG-induced antioxidant protection in human keratinocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 1444–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Roos, B.; Duthie, G.G. Role of dietary pro-oxidants in the maintenance of health and resilience to oxidative stress. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1229–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanner, J. Polyphenols by Generating H2O2, Affect Cell Redox Signaling, Inhibit PTPs and Activate Nrf2 Axis for Adaptation and Cell Surviving: In Vitro, In Vivo and Human Health. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungvari, Z.; Bagi, Z.; Feher, A.; Recchia, F.A.; Sonntag, W.E.; Pearson, K.; de Cabo, R.; Csiszar, A. Resveratrol confers endothelial protection via activation of the antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H18–H24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Hou, D.X. Multiple regulations of Keap1/Nrf2 system by dietary phytochemicals. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 1731–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iside, C.; Scafuro, M.; Nebbioso, A.; Altucci, L. SIRT1 Activation by Natural Phytochemicals: An Overview. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Xu, W.; Yamamoto, Y.; Suzuki, T. Curcumin increases heat shock protein 70 expression via different signaling pathways in intestinal epithelial cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 707, 108938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, H.; Tian, J.; Cheng, S.; Dou, H.; Zhu, Y. The mechanism of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha enhancing the transcriptional activity of transferrin ferroportin 1 and regulating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in ferroptosis after cerebral ischemic injury. Neuroscience 2024, 559, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hraoui, G.; Grondin, M.; Breton, S.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Nrf2 mediates mitochondrial and NADPH oxidase-derived ROS during mild heat stress at 40 degrees C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2025, 1872, 119897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yuan, D.; Fang, X.; Ding, M.; Qu, H.; Wang, X.; Ge, X.; Lu, K.; et al. Preventive hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves acute graft-versus-host disease by activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1529176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Guo, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, W.; Yao, K.; Chen, Z.; Dou, B.; Lin, X.; Chen, B.; et al. The Anti-Inflammatory Actions and Mechanisms of Acupuncture from Acupoint to Target Organs via Neuro-Immune Regulation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 7191–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.X.; Wu, C.Q.; Feng, W.; Zhan, Y.J.; Yang, L.; Jia, H.J.; Pei, J.; Li, K.P. Acupuncture for rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Xing, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Dong, A.; Liu, H.X. Knowledge domain and trends in acupuncture for stroke research based on bibliometric analysis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1544812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niruthisard, S.; Ma, Q.; Napadow, V. Recent advances in acupuncture for pain relief. Pain Rep. 2024, 9, e1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, P.; Quan, H.; Liang, X.; Lu, L. Integrative research on the mechanisms of acupuncture mechanics and interdisciplinary innovation. Biomed. Eng. Online 2025, 24, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yin, L.; Li, H.; Wang, J. Efficacy of acupuncture for stroke-associated pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1440121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, M.; Li, X.; Yu, D.; Jia, H.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhu, L. Effect of Acupuncture on Dysphagia after Stroke: A Meta-Analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Lamichhane, N.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Quynh, V.D.; Huang, J.; Gao, F.; Zhao, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, T. The effect of acupuncture on quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, R.R.; Cashin, A.G.; Wand, B.M.; Ferraro, M.C.; Sharma, S.; Lee, H.; O’Hagan, E.; Maher, C.G.; Furlan, A.D.; van Tulder, M.W.; et al. Non-pharmacological and non-surgical treatments for low back pain in adults: An overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 3, CD014691. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Jing, M.; Ren, H.; Li, G.; Wang, Z. Efficacy of electroacupuncture on clinical signs and immunological factors in herpes zoster: The first systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis of randomized clinical trials. Medicine 2025, 104, e41458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.R.; Shi, G.X.; Yang, J.W.; Yan, C.Q.; Lin, L.T.; Du, S.Q.; Zhu, W.; He, T.; Zeng, X.H.; Xu, Q.; et al. Acupuncture ameliorates cognitive impairment and hippocampus neuronal loss in experimental vascular dementia through Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Shang, Z.; You, L.; Zhang, J.; Jiao, J.; Qian, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, F.; Gao, Y.; Kong, X.; et al. Electroacupuncture Pretreatment at Zusanli (ST36) Ameliorates Hepatic Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Mice by Reducing Oxidative Stress via Activating Vagus Nerve-Dependent Nrf2 Pathway. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 1595–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Lu, Y. Acupuncture modulates the AMPK/PGC-1 signaling pathway to facilitate mitochondrial biogenesis and neural recovery in ischemic stroke rats. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 17, 1388759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.W.; Lin, H.W.; Yang, M.G.; Dai, Y.L.; Ding, Y.Y.; Xu, W.S.; Wang, S.N.; Cao, Y.J.; Liang, S.X.; Wang, Z.F.; et al. Electroacupuncture activates AMPKalpha1 to improve learning and memory in the APP/PS1 mouse model of early Alzheimer’s disease by regulating hippocampal mitochondrial dynamics. J. Integr. Med. 2024, 22, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ji, H.; Mao, W.; Zhang, L.; Tong, T.; Wang, J.; Cai, L.; Wang, H.; Sun, T.; Yi, H.; et al. Electroacupuncture regulates FTO/Nrf2/NLRP3 axis-mediated pyroptosis in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Neuroreport 2025, 36, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, Z.; Wen, F.; Lyu, P.; Huang, S.; Cai, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, C.; Man, W.; et al. Electroacupuncture ameliorated locomotor symptoms in MPTP-induced mice model of Parkinson’s disease by regulating autophagy via Nrf2 signaling. J. Neurophysiol. 2025, 133, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.H.; Fu, H.G.; Cheng, H.; Zheng, R.J.; Wang, G.; Li, S.; Li, E.Y.; Li, L.G. Electroacupuncture at Zusanli ameliorates the autistic-like behaviors of rats through activating the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant responses. Gene 2022, 828, 146440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, C.; Huang, B.; Huang, Y.; Wen, Z.; Luo, S. Keap1-independent GSK-3beta/Nrf2 signaling mediates electroacupuncture inhibition of oxidative stress to induce cerebral ischemia-reperfusion tolerance. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 217, 111071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.C.; Jin, Y.J.; Ning, R.; Mao, Q.Y.; Zhang, P.Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, C.C.; Peng, Y.C.; Chen, N. Electroacupuncture attenuates ferroptosis by promoting Nrf2 nuclear translocation and activating Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway in ischemic stroke. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.S.; Li, M.Y.; Yu, X.P.; Kan, Y.N.; Dai, X.H.; Zheng, L.; Cao, H.T.; Duan, W.H.; Luo, E.L.; Zou, W. Baihui-Penetrating-Qubin Acupuncture Attenuates Neurological Deficits Through SIRT1/FOXO1 Reducing Oxidative Stress and Neuronal Apoptosis in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Rats. Brain Behav. 2024, 14, e70095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, F.B.; Gu, Y.X.; Wang, J.L.; Chen, S.D. Electroacupuncture promotes macrophage/microglial M2 polarization and suppresses inflammatory pain through AMPK. Neuroreport 2024, 35, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Z.; Lu, Y.H.; Wu, M.; Chen, K.J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.T. Cupping Therapy for Diseases: An Overview of Scientific Evidence from 2009 to 2019. China J. Integr. Med. 2021, 27, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cai, Z.; Li, X.; Zhu, A. Efficacy of cupping therapy on pain outcomes: An evidence-mapping study. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1266712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, M.; Nakazato, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tominaga, E.; Yamamoto, T. Infectious Endocarditis With Subarachnoid Hemorrhage and Cerebral Infarction in an Atopic Dermatitis Patient During Unsanitary Cupping Therapy. Cureus 2024, 16, e71599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; Suzuki, K.; Sato, H.; Tabata, S.; Kume, H.; Nishikata, M.; Tamada, K.; Ooigawa, H.; Kurita, H. Intracranial mycotic aneurysm rupture following cupping therapy. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2024, 15, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jia, Y.; Sun, T.; Bai, Z.; Dong, X.; Hou, X. Interventions used in control group against cupping therapy for chronic nonspecific low back pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2025, 90, 103167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Hui, Y.Y.; Jiang, Z.F.; Ding, L.; Cheng, J.; Xing, T.; Zhai, H.; Zhang, H. Efficacy and safety of wet cupping in the treatment of neurodermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1478073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Pasapula, M.; Wang, Z.; Edwards, K.; Norrish, A. The effectiveness of cupping therapy on low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Complement. Ther. Med. 2024, 80, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekrami, N.; Ahmadian, M.; Nourshahi, M.; Shakouri, G.H. Wet-cupping induces anti-inflammatory action in response to vigorous exercise among martial arts athletes: A pilot study. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 56, 102611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Ding, X.; Zhang, J.; Kuai, L.; Ru, Y.; Sun, X.; Ma, T.; Miao, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Moving cupping therapy for plaque psoriasis: A PRISMA-compliant study of 16 randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2020, 99, e22539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Qi, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Ma, J.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, R. Cupping alleviates lung injury through the adenosine/A(2B)AR pathway. Heliyon 2022, 8, e12141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, S.P.K.; Khole, S.; Jagadish, N.; Ghosh, D.; Gadgil, V.; Sinkar, V.; Ghaskadbi, S.S. Andrographolide protects liver cells from H2O2 induced cell death by upregulation of Nrf-2/HO-1 mediated via adenosine A2a receptor signalling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 2377–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmedy, O.A.; Kamel, M.W.; Abouelfadl, D.M.; Shabana, M.E.; Sayed, R.H. Berberine attenuates epithelial mesenchymal transition in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice via activating A(2a)R and mitigating the SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling. Life Sci. 2023, 322, 121665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Park, N.J.; Jegal, H.; Paik, J.H.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.N.; Yang, M.H. Nymphoides peltata Root Extracts Improve Atopic Dermatitis by Regulating Skin Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidative Enzymes in 2,4-Dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB)-Induced SKH-1 Hairless Mice. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inferrera, F.; Tranchida, N.; Fusco, R.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Impellizzeri, D.; Siracusa, R.; D’Amico, R.; Rashan, L.; Badaeva, A.; Danilov, A.; et al. Neuronutritional enhancement of antioxidant defense system through Nrf2/HO1/NQO1 axis in fibromyalgia. Neurochem. Int. 2025, 190, 106057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, H.; Bonafiglia, J.T.; Turnbull, P.C.; Simpson, C.A.; Perry, C.G.R.; Gurd, B.J. The impact of acute and chronic exercise on Nrf2 expression in relation to markers of mitochondrial biogenesis in human skeletal muscle. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2020, 120, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Done, A.J.; Traustadottir, T. Nrf2 mediates redox adaptations to exercise. Redox Biol. 2016, 10, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segreti, A.; Celeski, M.; Guerra, E.; Crispino, S.P.; Vespasiano, F.; Buzzelli, L.; Fossati, C.; Papalia, R.; Pigozzi, F.; Grigioni, F. Effects of Environmental Conditions on Athlete’s Cardiovascular System. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munzel, T.; Sorensen, M.; Lelieveld, J.; Landrigan, P.J.; Kuntic, M.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; Miller, M.R.; Schneider, A.; Daiber, A. A comprehensive review/expert statement on environmental risk factors of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 121, 1653–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolis, A.S.; Manolis, S.A.; Manolis, A.A.; Manolis, T.A.; Apostolaki, N.; Melita, H. Winter Swimming: Body Hardening and Cardiorespiratory Protection Via Sustainable Acclimation. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2019, 18, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjoberg, F.; Singer, M. The medical use of oxygen: A time for critical reappraisal. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 274, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, R.T.; Burtscher, J.; Richalet, J.P.; Millet, G.P.; Burtscher, M. Impact of High Altitude on Cardiovascular Health: Current Perspectives. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezpeleta, M.; Cienfuegos, S.; Lin, S.; Pavlou, V.; Gabel, K.; Varady, K.A. Efficacy and safety of prolonged water fasting: A narrative review of human trials. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 82, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Agathokleous, E. Hormesis: Transforming disciplines that rely on the dose response. IUBMB Life 2022, 74, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Guo, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xia, S.; Gong, H.; Zhang, B.K.; Yan, M. Dissecting the Crosstalk Between Nrf2 and NF-kappaB Response Pathways in Drug-Induced Toxicity. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 809952. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, E.; Esteras, N. Multitarget Effects of Nrf2 Signalling in the Brain: Common and Specific Functions in Different Cell Types. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Lifestyle Practice | Stress Signals a | Adaptive Response Mediators a | Major Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to heat [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72] | SNS, ROS, NAD+, AMP | PNS, Nrf2, HSF1, PGC-1α, NFkB | Cardiovascular function |

| Exposure to cold [72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87] | SNS, ROS, catecholamines | PNS, Nrf2, sirtuins, AMPK | Cardiovascular function |

| Hyperbaric oxygen [88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96] | ROS | Nrf2, HIF-1α, sirtuins, AMPK | Tissue repair |

| Exposure to hypoxia [97,98,99,100,101,102] | SNS, ROS, NO, NAD+, AMP | HIF-1α, Nrf2, PGC-1α, AMPK, sirtuins | Vascular + cognitive function |

| Caloric restriction [103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119] | ROS, NAD+, AMP | Nrf2, AMPK, PGC-1α, sirtuins | Cardiometabolic function |

| Dietary polyphenols [120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136] | ROS, NO, NAD+, AMP | Nrf2, AMPK, PGC-1α, sirtuins | Organ function |

| (Electro) acupuncture [137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157] | ROS | Nrf2, sirtuins, AMPK | Tissue function |

| Cupping therapy [158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169] | IL-6, TNF-α, adenosine | Nrf2 (?) | Anti-inflammatory response |

| Key Messages |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kolb, H.; Martin, S.; Kempf, K. Traditional Health Practices May Promote Nrf2 Activation Similar to Exercise. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11546. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311546

Kolb H, Martin S, Kempf K. Traditional Health Practices May Promote Nrf2 Activation Similar to Exercise. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11546. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311546

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolb, Hubert, Stephan Martin, and Kerstin Kempf. 2025. "Traditional Health Practices May Promote Nrf2 Activation Similar to Exercise" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11546. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311546

APA StyleKolb, H., Martin, S., & Kempf, K. (2025). Traditional Health Practices May Promote Nrf2 Activation Similar to Exercise. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11546. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311546