Role of ChREBP–PPARα–FGF21 Axis in Metabolic Dysfunction of MASLD

Abstract

1. Introduction

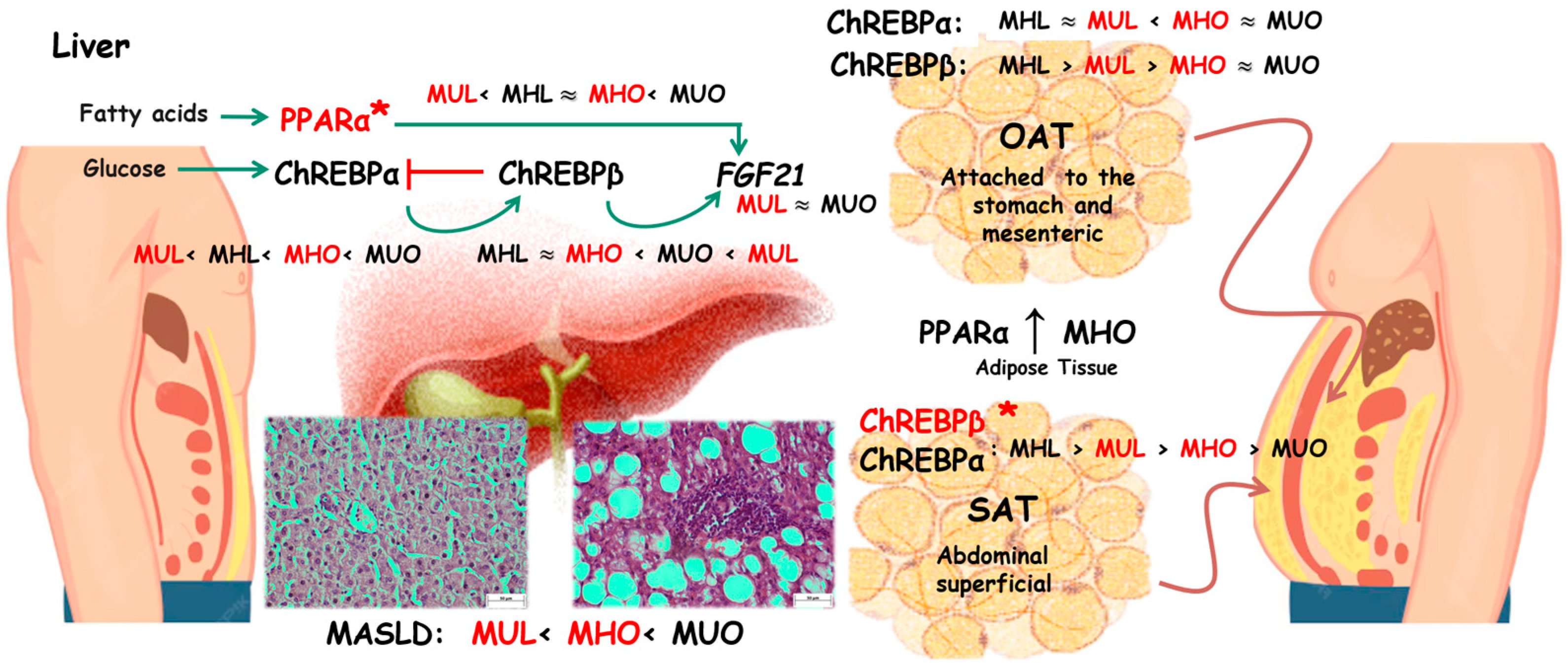

2. Results

2.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

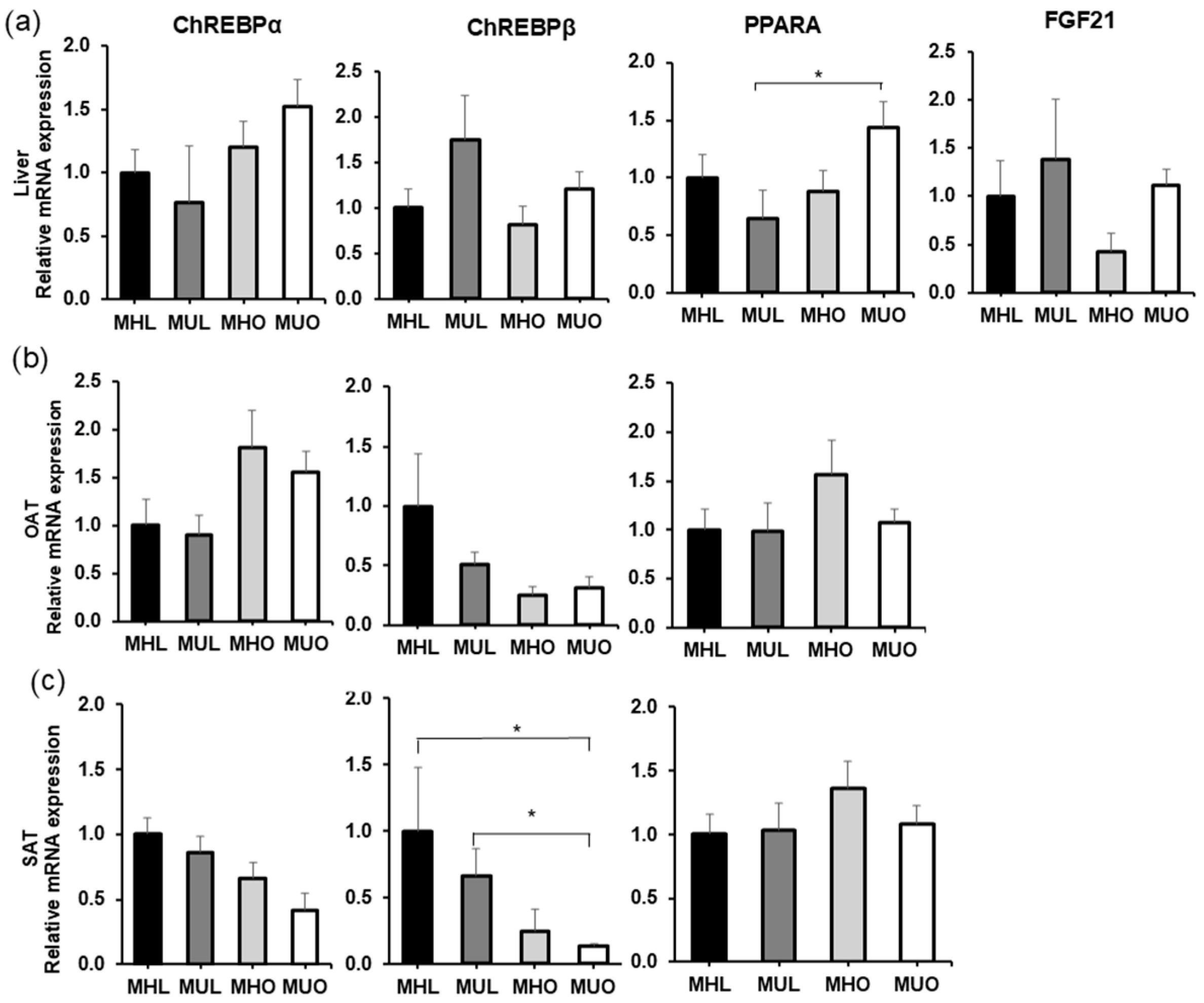

2.2. qPCR Gene Expression Analysis of mRNA

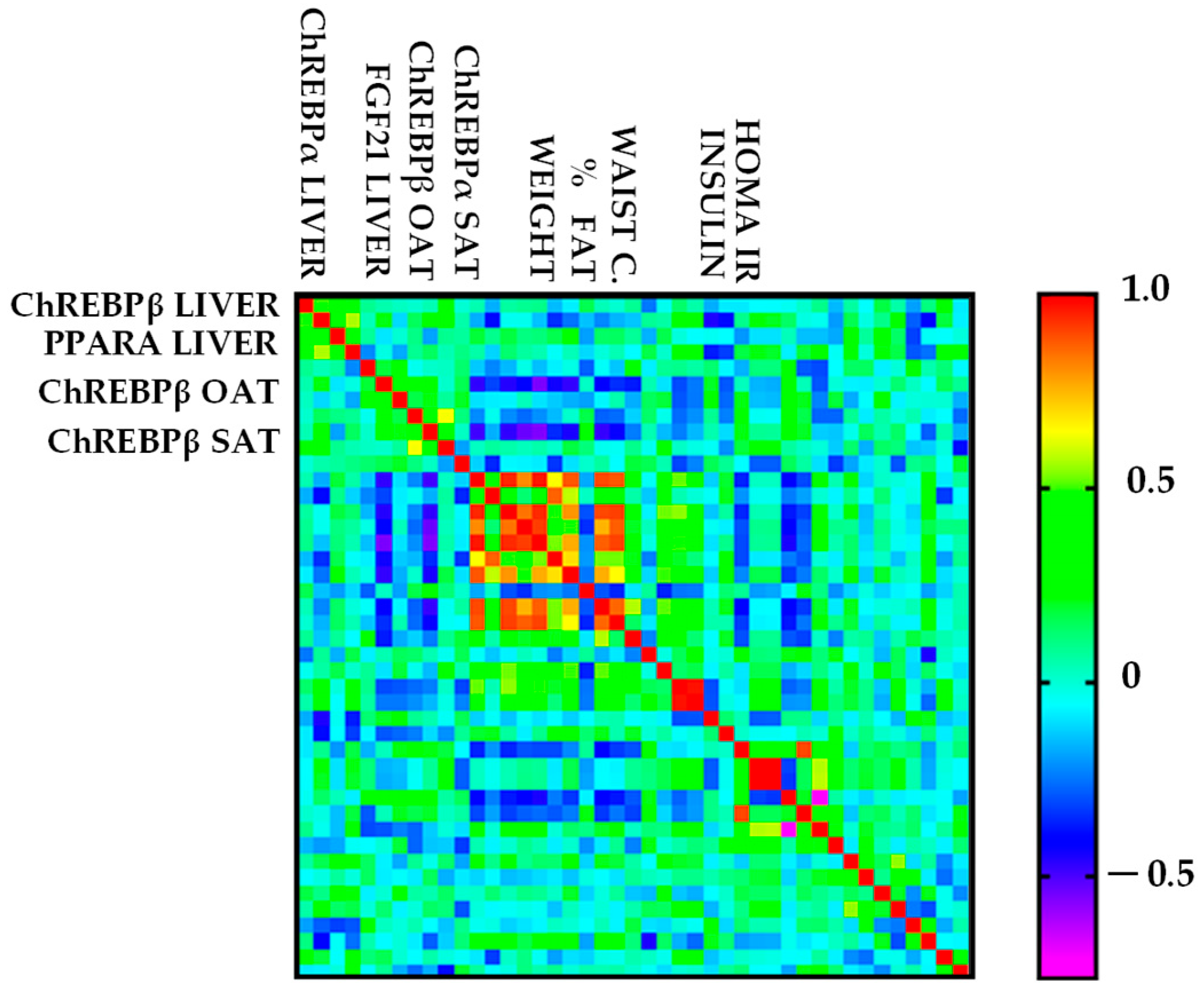

2.2.1. Correlation Analysis

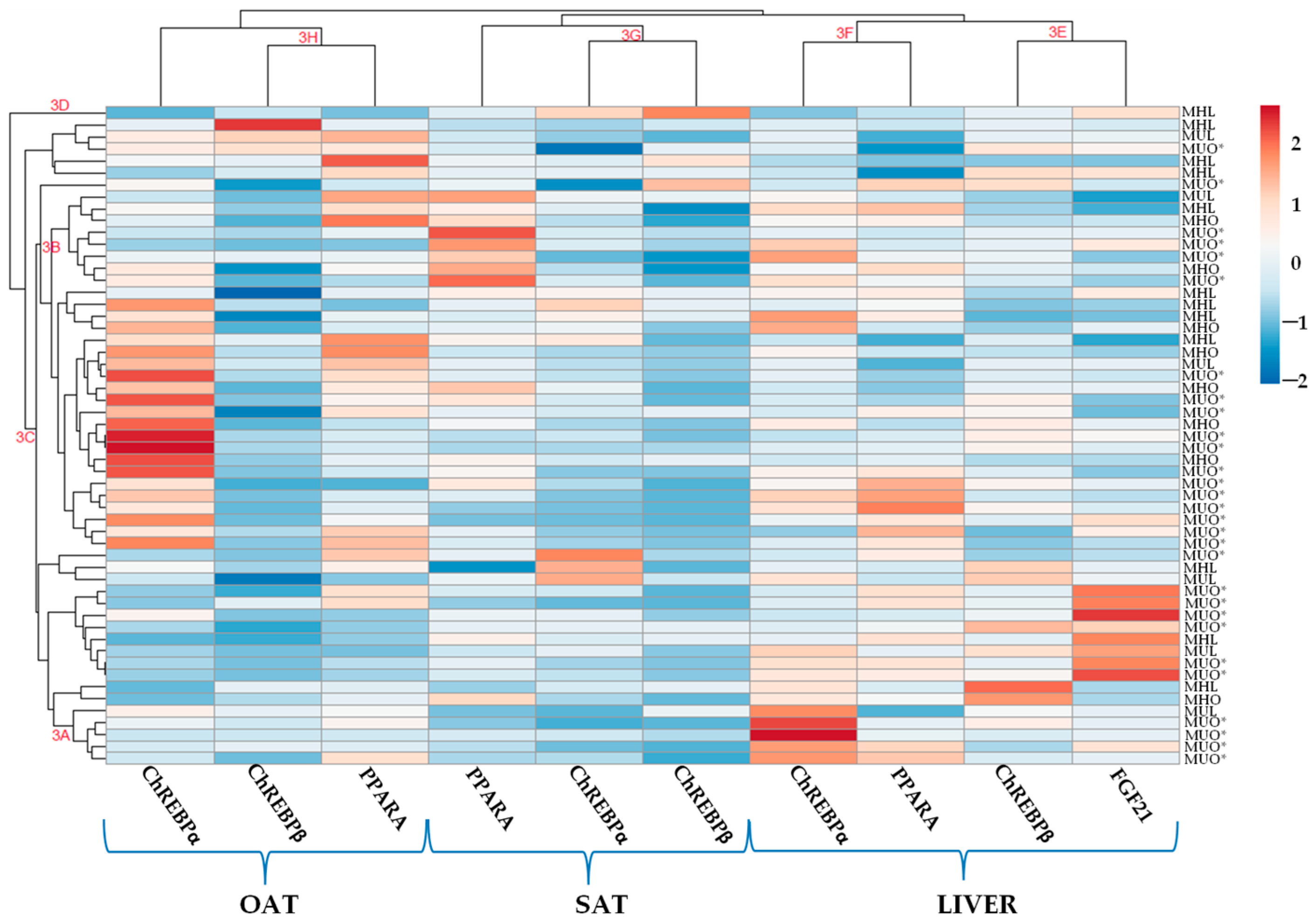

2.2.2. Heatmap Analysis

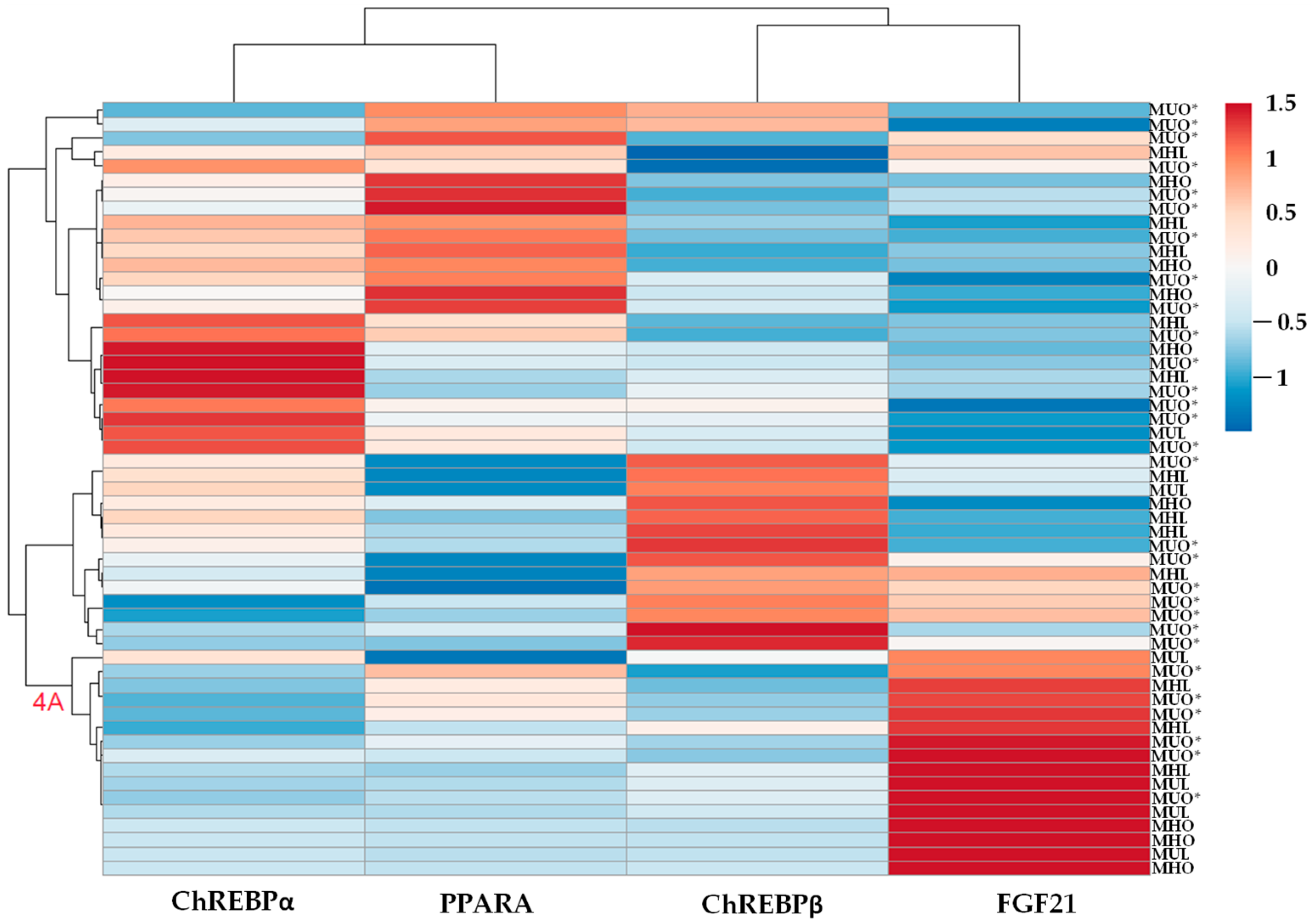

2.2.3. Liver Heatmap Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. PPARA Expression

3.2. MLXIPL Expression

3.3. FGF21 Expression

3.4. Study Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Subjects

4.2. Anthropometric Measurements

4.3. Biochemical Measurements

4.4. Tissue Samples, RNA Extraction, and Real-Time qPCR

4.5. Liver Histology

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| ChREBP | Carbohydrate Response Element Binding Protein |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| GGT | Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase |

| FLI | Fatty Liver Index |

| FGF21 | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| HDL-c | High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance |

| hs-CRP | High-Sensitivity C Reactive Protein |

| LDL-c | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| MASLD | Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease |

| MetS | Metabolic Syndrome |

| MHL | Metabolically Healthy Lean |

| MHO | Metabolically Healthy Obese |

| MLXIPL | MLX Interacting Protein-Like |

| MUL | Metabolically Unhealthy Lean |

| MUO | Metabolically Unhealthy Obese |

| OAT | Omental Adipose Tissue |

| PPARA | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Alpha |

| SAT | Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| T2D | Type 2 Diabetes |

| VAI | Visceral Adiposity Index |

| VLDL-c | Very-Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

References

- Feng, G.; Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Yilmaz, Y.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Lesmana, C.R.A.; Adams, L.A.; Boursier, J.; Papatheodoridis, G.; El-Kassas, M.; et al. Global Burden of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease, 2010 to 2021. JHEP Rep. 2024, 7, 101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A Multisociety Delphi Consensus Statement on New Fatty Liver Disease Nomenclature. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, S.M.; Cleeman, J.I.; Merz, C.N.; Brewer, H.B., Jr.; Clark, L.T.; Hunninghake, D.B.; Pasternak, R.C.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; Stone, N.J.; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation 2004, 110, 227–239, Erratum in Circulation 2004, 110, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.I.; Mittendorfer, B.; Klein, S. Metabolically Healthy Obesity: Facts and Fantasies. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 3978–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnier, M.; Carbinatti, T.; Parlati, L.; Benhamed, F.; Postic, C. The Role of ChREBP in Carbohydrate Sensing and NAFLD Development. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, M.A.; Peroni, O.D.; Villoria, J.; Schön, M.R.; Abumrad, N.A.; Blüher, M.; Klein, S.; Kahn, B.B. A Novel ChREBP Isoform in Adipose Tissue Regulates Systemic Glucose Metabolism. Nature 2012, 484, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iroz, A.; Montagner, A.; Benhamed, F.; Levavasseur, F.; Polizzi, A.; Anthony, E.; Régnier, M.; Fouché, E.; Lukowicz, C.; Cauzac, M.; et al. A Specific ChREBP and PPARα Cross-Talk Is Required for the Glucose-Mediated FGF21 Response. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Ruiz, I.; Medina, M.Á.; Martínez-Poveda, B. From Food to Genes: Transcriptional Regulation of Metabolism by Lipids and Carbohydrates. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Suppl. S1), S27–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lorenzo, A.; Soldati, L.; Sarlo, F.; Calvani, M.; Di Lorenzo, N.; Di Renzo, L. New Obesity Classification Criteria as a Tool for Bariatric Surgery Indication. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 681–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation; WHO Technical Report Series 894; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000; pp. 1–253. [Google Scholar]

- Hojs, R.; Ekart, R.; Bevc, S.; Vodošek Hojs, N. Chronic Kidney Disease and Obesity. Nephron 2023, 147, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, I.A.; Kounatidis, D.; Vallianou, N.G.; Skourtis, A.; Dimitriou, K.; Tzivaki, I.; Tsioulos, G.; Rigatou, A.; Karampela, I.; Dalamaga, M. Beneath the Surface: The Emerging Role of Ultra-Processed Foods in Obesity-Related Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2025, 27, 390–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedunchezhiyan, U.; Varughese, I.; Sun, A.R.; Wu, X.; Crawford, R.; Prasadam, I. Obesity, Inflammation, and Immune System in Osteoarthritis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 907750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figorilli, M.; Velluzzi, F.; Redolfi, S. Obesity and Sleep Disorders: A Bidirectional Relationship. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2025, 35, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, S.W.; Vázquez-Velázquez, V.; Le Brocq, S.; Brown, A. The Real-Life Experiences of People Living with Overweight and Obesity: A Psychosocial Perspective. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2025, 27 (Suppl. S2), 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elías-López, D.; Vargas-Vázquez, A.; Mehta, R.; Cruz Bautista, I.; Del Razo Olvera, F.; Gómez-Velasco, D.; Almeda Valdes, P.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Metabolic Syndrome Study Group. Natural Course of Metabolically Healthy Phenotype and Risk of Developing Cardiometabolic Diseases: A Three Years Follow-Up Study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2021, 21, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agius, R.; Pace, N.P.; Fava, S. Phenotyping Obesity: A Focus on Metabolically Healthy Obesity and Metabolically Unhealthy Normal Weight. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2024, 40, e3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravina, G.; Ferrari, F.; Nebbiai, G. The Obesity Paradox and Diabetes. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 26, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Ng, C.H.; Phang, P.H.; Chan, K.E.; Chin, Y.H.; Fu, C.E.; Zeng, R.W.; Xiao, J.; Tan, D.J.H.; Quek, J.; et al. Comparative Burden of Metabolic Dysfunction in Lean NAFLD vs. Non-Lean NAFLD—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 1750–1760.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, M.W.; Kim, J.Y. Metabolically Unhealthy Phenotype in Adults with Normal Weight: Is Cardiometabolic Health Worse Off When Compared to Adults with Obesity? Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 17, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato-Espinoza, K.; Chotiprasidhi, P.; Huaman, M.R.; Díaz-Ferrer, J. Update in Lean Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. World J. Hepatol. 2024, 16, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, S.I.; Tamaki, N.; Kimura, T.; Umemura, T.; Kurosaki, M.; Izumi, N. Natural History of Lean and Non-Lean Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 59, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebovics, N.; Heering, G.; Frishman, W.H.; Lebovics, E. Lean MASLD and Cardiovascular Disease: A Review. Cardiol. Rev. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L. Hepatic Fibrosis and Cancer: The Silent Threats of Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes Metab. J. 2024, 48, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danpanichkul, P.; Suparan, K.; Prasitsumrit, V.; Ahmed, A.; Wijarnpreecha, K.; Kim, D. Long-Term Outcomes and Risk Modifiers of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease between Lean and Non-Lean Populations. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2025, 31, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas-Gomez, B.; Almeda-Valdés, P.; Tussié-Luna, M.T.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A. Dyslipidemia in Mexico, a Call for Action. Rev. Investig. Clin. 2018, 70, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Bautista, I.; Escamilla-Núñez, C.; Flores-Jurado, Y.; Rojas-Martínez, R.; Elías López, D.; Muñoz-Hernández, L.; Mehta, R.; Almeda-Valdes, P.; Del Razo-Olvera, F.M.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; et al. Distribution of Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins and Their Remnants and Their Contribution to Cardiovascular Risk in the Mexican Population. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2024, 21, S1933-2874(24)00185-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Castor, L.; O’Hearn, M.; Cudhea, F.; Miller, V.; Shi, P.; Zhang, J.; Sharib, J.R.; Cash, S.B.; Barquera, S.; Micha, R.; et al. Burdens of Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease Attributable to Sugar-Sweetened Beverages in 184 Countries. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 552–564, Erratum in Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, A.; Cantor, R.M.; Weissglas-Volkov, D.; Nikkola, E.; Reddy, P.M.; Sinsheimer, J.S.; Pasaniuc, B.; Brown, R.; Alvarez, M.; Rodriguez, A.; et al. Amerindian-Specific Regions under Positive Selection Harbour New Lipid Variants in Latinos. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Vicente, H.L. Trends in Management of Gallbladder Disorders in Children. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 1997, 12, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portincasa, P.; Di Ciaula, A.; de Bari, O.; Garruti, G.; Palmieri, V.O.; Wang, D.Q. Management of Gallstones and Its Related Complications. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 10, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, Z.; Bobbioni-Harsch, E.; Golay, A. Open Questions about Metabolically Normal Obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34 (Suppl. S2), S18–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M.C.; Smith, G.I.; Palacios, H.H.; Farabi, S.S.; Yoshino, M.; Yoshino, J.; Cho, K.; Davila-Roman, V.G.; Shankaran, M.; Barve, R.A.; et al. Cardiometabolic Characteristics of People with Metabolically Healthy and Unhealthy Obesity. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 745–761.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribarri, J.; Cai, W.; Woodward, M.; Tripp, E.; Goldberg, L.; Pyzik, R.; Yee, K.; Tansman, L.; Chen, X.; Mani, V.; et al. Elevated Serum Advanced Glycation Endproducts in Obese Indicate Risk for the Metabolic Syndrome: A Link between Healthy and Unhealthy Obesity? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 1957–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruelas Cinco, E.D.C.; Ruíz Madrigal, B.; Domínguez Rosales, J.A.; Maldonado González, M.; De la Cruz Color, L.; Ramírez Meza, S.M.; Torres Baranda, J.R.; Martínez López, E.; Hernández Nazará, Z.H. Expression of the Receptor of Advanced Glycation End-Products (RAGE) and Membranal Location in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC) in Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ye, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Gong, X.; Deng, H.; Dong, Z.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Zhong, B. High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Implicates Heterogeneous Metabolic Phenotypes and Severity in Metabolic Dysfunction Associated-Steatotic Liver Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Zhao, L. Association of High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein and Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2 with Metabolically Unhealthy Phenotype: A Cross Sectional Study. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.U.; Yoon, J.H. Systemic Inflammation across Metabolic Obesity Phenotypes: A Cross-Sectional Study of Korean Adults Using High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein as a Biomarker. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cӑtoi, A.F.; Pârvu, A.E.; Andreicuț, A.D.; Mironiuc, A.; Crӑciun, A.; Cӑtoi, C.; Pop, I.D. Metabolically Healthy versus Unhealthy Morbidly Obese: Chronic Inflammation, Nitro-Oxidative Stress, and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gil, E.M.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Santabárbara, J.; Bueno-Lozano, G.; Iglesia, I.; González-Gross, M.; Molnar, D.; Gottrand, F.; De Henauw, S.; Kafatos, A.; et al. Inflammation in Metabolically Healthy and Metabolically Abnormal Adolescents: The HELENA Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Pugliese, G.; de Alteriis, G.; Colao, A.; Savastano, S. Metabolically Healthy Obesity (MHO) vs. Metabolically Unhealthy Obesity (MUO) Phenotypes in PCOS: Association with Endocrine-Metabolic Profile, Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet, and Body Composition. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messier, V.; Karelis, A.D.; Robillard, M.E.; Bellefeuille, P.; Brochu, M.; Lavoie, J.M.; Rabasa-Lhoret, R. Metabolically Healthy but Obese Individuals: Relationship with Hepatic Enzymes. Metabolism 2010, 59, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, N.S.; Saraf, N.; Saigal, S.; Duseja, A.; Gautam, D.; Rastogi, A.; Bhangui, P.; Thiagrajan, S.; Soin, A.S. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver in Lean Individuals: Clinicobiochemical Correlates of Histopathology in 157 Liver Biopsies from Healthy Liver Donors. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2021, 11, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Fu, C.; Chen, H. Influence of Triglycerides on the Link between Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase to High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Nonobese Chinese Adults: A Secondary Cohort Study. Medicine 2025, 104, e42078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, R.; Kikuchi, A.; Ninomiya, D. Can Serum Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase Predict All-Cause Mortality in Hypertensive Patients? Cureus 2024, 16, e68247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninomiya, K.; Serruys, P.W.; Garg, S.; Kageyama, S.; Kotoku, N.; Masuda, S.; Revaiah, P.C.; O’Leary, N.; Kappetein, A.P.; Mack, M.J.; et al. γ-Glutamyl Transferase and Long-Term Survival in the SYNTAXES Trial: Is It Just the Liver? J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e032276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, S.; Diao, H.; Lu, G.; Shi, L. Associations between Serum Levels of Liver Function Biomarkers and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Dou, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhang, L. Gamma-Glutamyltransferase Activity (GGT) Is a Long-Sought Biomarker of Redox Status in Blood Circulation: A Retrospective Clinical Study of 44 Types of Human Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 8494076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Pérez, E.; Mar-Buruato, A.M.; Tijerina-Sáenz, A.; Sánchez-Peña, M.A.; González-Martínez, B.E.; Lavalle-González, F.J.; Villarreal-Pérez, J.Z.; Sánchez-Solís, G.; López-Cabanillas Lomelí, M. Adipokines and Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase as Biomarkers of Metabolic Syndrome Risk in Mexican School-Aged Children. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduri, V.D.; Eresha, J.; Dulani, S.; Pujitha, W. Association of Fatty Liver with Serum Gamma-Glutamyltransferase and Uric Acid in Obese Children in a Tertiary Care Centre. BMC Pediatr. 2025, 25, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.; Kapoor, A.; Khanna, R.; Sahu, A.; Kapoor, V.; Kumar, S.; Garg, N.; Tewari, S.; Goel, P. Serum Gamma Glutamyltransferase (GGT) in Coronary Artery Disease: Exploring the Asian Indian Connection. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2022, 25, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhyzhneuskaya, S.V.; Al-Mrabeh, A.H.; Peters, C.; Barnes, A.C.; Hollingsworth, K.G.; Welsh, P.; Sattar, N.; Lean, M.E.J.; Taylor, R. Clinical Utility of Liver Function Tests for Resolution of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease after Weight Loss in the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial. Diabet. Med. 2025, 42, e15462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Y.; Rashid, A.M.; Siddiqi, A.K.; Ellahi, A.; Ahmed, A.; Hussain, H.U.; Ahmed, F.; Menezes, R.G.; Siddiqi, T.J.; Maniya, M.T. Effect of Novel Glucose Lowering Agents on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2022, 46, 101970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, K.; Tsuzaki, K.; Sakane, N. The Relationship between Gamma-Glutamyltransferase (GGT), Bilirubin (Bil) and Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein (sdLDL) in Asymptomatic Subjects Attending a Clinic for Screening Dyslipidaemias. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2014, 43, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, M.; Hu, J. The Relationship Between Small Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Li, X.; Rong, Y.; Wang, X.; Hou, L.; Gu, W.; Hou, X.; Guan, Y.; Liu, L.; Geng, J.; et al. Serum Gamma Glutamyl-Transferase: A Biomarker for Identifying Postprandial Hypertriglyceridemia. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 2273–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Liu, C.; Guo, Y.; Gao, Q.; Zhong, C.; Zhou, X.; Chen, R.; Xiong, G.; Yang, X.; Hao, L.; et al. Higher Level of GGT during Mid-Pregnancy Is Associated with Increased Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Clin. Endocrinol. 2018, 88, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koly, H.; Das, T.R.; Haque, N.; Hosain, N.; Islam, M.F.; Tithi, S.S.; Bari, M.S.; Jannat, Y.D.; Khan, N.J. Association of Serum Gamma Glutamyl Transferase with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Mymensingh Med. J. 2025, 34, 502–508. [Google Scholar]

- Margariti, E.; Deutsch, M.; Manolakopoulos, S.; Papatheodoridis, G.V. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease May Develop in Individuals with Normal Body Mass Index. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2012, 25, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, R.; Cakir, A.D.; Ada, H.İ.; Uçar, A. Comparative Analyses of Surrogates of Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents with Metabolically Healthy Obesity vs. Metabolically Unhealthy Obesity According to Damanhoury’s Criteria. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 36, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Zhang, S.; Yu, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, G.; Hu, S. Association between Liver Enzymes with Metabolically Unhealthy Obese Phenotype. Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Guan, Z.; Li, P. Association between Cardiovascular Health and Markers of Liver Function: A Cross-Sectional Study from NHANES 2005–2018. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1538654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, Z.; Tian, S.; Sun, C. Association between Liver Enzymes and Type 2 Diabetes: A Real-World Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1340604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valderrábano, R.J.; Badour, S.; Ferri-Guerra, J.; Barb, D.; Garg, R. Body Fat Distribution in Lean Individuals with Metabolic Abnormalities. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2023, 21, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Baker, C.; Christian, P.; Naples, M.; Tong, X.; Zhang, K.; Santha, M.; Adeli, K. Hepatic Mitochondrial and ER Stress Induced by Defective PPARα Signaling in the Pathogenesis of Hepatic Steatosis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 306, E1264–E1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, P.F. PPARα: An Emerging Target of Metabolic Syndrome, Neurodegenerative and Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1074911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francque, S.; Verrijken, A.; Caron, S.; Prawitt, J.; Paumelle, R.; Derudas, B.; Lefebvre, P.; Taskinen, M.R.; Van Hul, W.; Mertens, I.; et al. PPARα Gene Expression Correlates with Severity and Histological Treatment Response in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botta, M.; Audano, M.; Sahebkar, A.; Sirtori, C.R.; Mitro, N.; Ruscica, M. PPAR Agonists and Metabolic Syndrome: An Established Role? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto-Torres, G.; Parodi-Rullán, R.; Javadov, S. The Role of PPARα in Metformin-Induced Attenuation of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Acute Cardiac Ischemia/Reperfusion in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 7694–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.X.; Wang, X.; Jiao, S.Y.; Liu, Y.; Shi, L.; Xu, Q.; Wang, J.J.; Chen, Y.E.; Zhang, Q.; Song, Y.T.; et al. Cardiomyocyte Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor α Prevents Septic Cardiomyopathy via Improving Mitochondrial Function. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2023, 44, 2184–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Feng, H.; Cheng, J.; Li, Z.; Jin, M.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Q.; Qin, H.; Liu, G. Geniposide Alleviates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease via Regulating Nrf2/AMPK/mTOR Signalling Pathways. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 5097–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Wolski, K.; Topol, E.J. Effect of Muraglitazar on Death and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA 2005, 294, 2581–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.J. Learning from Tesaglitazar. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 2007, 4, 161–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göke, B.; Gause-Nilsson, I.; Persson, A.; GALLANT 8 Study Group. The Effects of Tesaglitazar as Add-On Treatment to Metformin in Patients with Poorly Controlled Type 2 Diabetes. Diab. Vasc. Dis. Res. 2007, 4, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.L.; Qu, C.Z. Cardiovascular Risk and Safety Evaluation of a Dual Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Alpha/Gamma Agonist, Aleglitazar, in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 75, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Tanaka, N.; Li, G.; Hu, R.; Kamijo, Y.; Hara, A.; Aoyama, T. Effect of Bezafibrate on Hepatic Oxidative Stress: Comparison between Conventional Experimental Doses and Clinically-Relevant Doses in Mice. Redox Rep. 2010, 15, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Watkins, S.M.; Hotamisligil, G.S. The Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum in Hepatic Lipid Homeostasis and Stress Signaling. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wu, X.; Chen, H.; Xia, X.; Song, X.; Chen, S.; Lu, X.; Jin, J.; Su, Q.; Cai, D.; et al. Aging-Induced Aberrant RAGE/PPARα Axis Promotes Hepatic Steatosis via Dysfunctional Mitochondrial β-Oxidation. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.T.; Sun, Q.M.; Xin, X.; Ng, C.H.; Valenti, L.; Hu, Y.Y.; Zheng, M.H.; Feng, Q. Comparative Efficacy of THR-β Agonists, FGF-21 Analogues, GLP-1R Agonists, GLP-1-Based Polyagonists, and Pan-PPAR Agonists for MASLD: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Metabolism 2024, 161, 156043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recazens, E.; Tavernier, G.; Dufau, J.; Bergoglio, C.; Benhamed, F.; Cassant-Sourdy, S.; Marques, M.A.; Caspar-Bauguil, S.; Brion, A.; Monbrun, L.; et al. ChREBPβ Is Dispensable for the Control of Glucose Homeostasis and Energy Balance. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e153431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannou, S.; Sargsyan, A.; Tong, W.; An, J.; Newgard, C.B.; Astapova, I.; Herman, M.A. 1562-P: Hepatic ChREBP-β Overexpression Enhances Peripheral Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis Independently of FGF21. Diabetes 2023, 72 (Suppl. S1), 1562-P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, K.; Takao, K.; Yabe, D. ChREBP-Mediated Regulation of Lipid Metabolism: Involvement of the Gut Microbiota, Liver, and Adipose Tissue. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 587189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Prieto, P.; Postic, C. Carbohydrate Sensing through the Transcription Factor ChREBP. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, L.S.; Baumel-Alterzon, S.; Scott, D.K.; Herman, M.A. Adaptive and Maladaptive Roles for ChREBP in the Liver and Pancreatic Islets. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pozo, H.; Vesperinas-García, G.; Rubio, M.; Corripio-Sánchez, R.; Torres-García, A.; Obregon, M.; Calvo, R. ChREBP Expression in the Liver, Adipose Tissue and Differentiated Preadipocytes in Human Obesity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1811, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kursawe, R.; Caprio, S.; Giannini, C.; Narayan, D.; Lin, A.; D’Adamo, E.; Shaw, M.; Pierpont, B.; Cushman, S.; Shulman, G. Decreased Transcription of ChREBP-α/β Isoforms in Abdominal Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue of Obese Adolescents with Prediabetes or Early Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2013, 62, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ter Horst, K.W.; Vatner, D.F.; Zhang, D.; Cline, G.W.; Ackermans, M.T.; Nederveen, A.J.; Verheij, J.; Demirkiran, A.; van Wagensveld, B.A.; Dallinga-Thie, G.M.; et al. Hepatic Insulin Resistance Is Not Pathway Selective in Humans with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hube, F.; Lietz, U.; Igel, M.; Janke, P.B.; Tornqvist, H.; Janke, H.G.; Hauner, H. Difference in Leptin mRNA Levels between Omental and Subcutaneous Abdominal Adipose Tissue from Obese Humans. Horm. Metab. Res. 1996, 28, 690–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, A.; Laville, M.; Véga, N.; Riou, J.; Gaal, L.; Auwerx, J.; Vidal, H. Depot-Specific Differences in Adipose Tissue Gene Expression in Lean and Obese Subjects. Diabetes 1998, 47, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Cuenca, J.; De La Peña-Sosa, G.; De La Vega-Moreno, K.; Banderas-Lares, D.; Salamanca-García, M.; Martínez-Hernández, J.; Vera-Gómez, E.; Hernández-Patricio, A.; Zamora-Alemán, C.; Dominguez-Perez, G.; et al. Enlarged Adipocytes from Subcutaneous vs. Visceral Adipose Tissue Differentially Contribute to Metabolic Dysfunction and Atherogenic Risk of Patients with Obesity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 81289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ayala, M.A.; Rodríguez-Amador, V.; Suárez-Sánchez, R.; León-Solís, L.; Gómez-Zamudio, J.; Mendoza-Zubieta, V.; Cruz, M.; Suárez-Sánchez, F. Expression of Obesity- and Type-2 Diabetes-Associated Genes in Omental Adipose Tissue of Individuals with Obesity. Gene 2022, 815, 146181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitticharoon, C.; Maikaew, P.; Keadkraichaiwat, I.; Chatree, S. The Influence of Subcutaneous and Visceral Adipocyte Geometries on Metabolic Parameters and Metabolic Regulating Hormones in Obese and Non-Obese Subjects. Physiology 2024, 39 (Suppl. S1), 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatikos, A.D.; da Silva, R.P.; Lewis, J.T.; Douglas, D.N.; Kneteman, N.M.; Jacobs, R.L.; Paton, C.M. Tissue-Specific Effects of Dietary Carbohydrates and Obesity on ChREBPα and ChREBPβ Expression. Lipids 2016, 51, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jois, T.; Howard, V.; Youngs, K.; Cowley, M.A.; Sleeman, M.W. Dietary Macronutrient Composition Directs ChREBP Isoform Expression and Glucose Metabolism in Mice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borji, M.; Dadkhah Nikroo, N.; Yousefi, Z.; Nourbakhsh, M.; Abdolvahabi, Z.; Nourbakhsh, M.; Larijani, B.; Razzaghy-Azar, M. The Expression of Gene Encoding Carbohydrate Response Element Binding Protein in Obesity and Its Relationship with Visceral Adiposity and Metabolic Syndrome. Hum. Gene 2022, 33, 201058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jois, T.; Chen, W.; Howard, V.; Harvey, R.; Youngs, K.; Thalmann, C.; Saha, P.; Chan, L.; Cowley, M.A.; Sleeman, M.W. Deletion of Hepatic Carbohydrate Response Element Binding Protein (ChREBP) impairs Glucose Homeostasis and Hepatic Insulin Sensitivity in Mice. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamed, F.; Denechaud, P.D.; Lemoine, M.; Robichon, C.; Moldes, M.; Bertrand-Michel, J.; Ratziu, V.; Serfaty, L.; Housset, C.; Capeau, J.; et al. The Lipogenic Transcription Factor ChREBP dissociates Hepatic Steatosis from Insulin Resistance in Mice and Humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2176–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, B. The Function of MondoA and ChREBP Nutrient-Sensing Factors in Metabolic Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petricek, K.M.; Kirchner, M.; Sommerfeld, M.; Stephanowitz, H.; Kiefer, M.F.; Meng, Y.; Dittrich, S.; Dähnhardt, H.E.; Mai, K.; Krause, E.; et al. An Acetylated Lysine Residue of Its Low-Glucose Inhibitory Domain Controls Activity and Protein Interactions of ChREBP. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 169189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, L.S.; Visser, E.J.; Plitzko, K.F.; Pennings, M.A.; Cossar, P.J.; Tse, I.L.; Kaiser, M.; Brunsveld, L.; Ottmann, C.; Scott, D.K. Molecular Glues of the Regulatory ChREBP/14-3-3 Complex Protect Beta Cells from Glucolipotoxicity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, G.; Chen, J.; Xu, G.; Shalev, A. Islet ChREBP-β Is Increased in Diabetes and Controls ChREBP-α and Glucose-Induced Gene Expression via a Negative Feedback Loop. Mol. Metab. 2016, 5, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T.; Nakatake, Y.; Konishi, M.; Itoh, N. Identification of a Novel FGF, FGF-21, Preferentially Expressed in the Liver. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1492, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, F.M.; Kleiner, S.; Douris, N.; Fox, E.C.; Mepani, R.J.; Verdeguer, F.; Wu, J.; Kharitonenkov, A.; Flier, J.S.; Maratos-Flier, E.; et al. FGF21 Regulates PGC-1α and Browning of White Adipose Tissues in Adaptive Thermogenesis. Genes Dev. 2012, 26, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, A.; Khan, M.I.; Bonneville, A.; Guo, C.; Jeffery, J.; O’Neill, L.; Syed, D.N.; Lewis, S.A.; Burhans, M.; Mukhtar, H.; et al. Hepatic Stearoyl CoA Desaturase 1 Deficiency Increases Glucose Uptake in Adipose Tissue Partially Through the PGC-1α-FGF21 Axis in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 19475–19485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mraz, M.; Bartlova, M.; Lacinova, Z.; Michalsky, D.; Kasalicky, M.; Haluzikova, D.; Matoulek, M.; Dostalova, I.; Humenanska, V.; Haluzik, M. Serum Concentrations and Tissue Expression of a Novel Endocrine Regulator Fibroblast Growth Factor-21 in patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity. Clin. Endocrinol. 2009, 71, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dushay, J.; Chui, P.C.; Gopalakrishnan, G.S.; Varela-Rey, M.; Crawley, M.; Fisher, F.M.; Badman, M.K.; Martinez-Chantar, M.L.; Maratos-Flier, E. Increased Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 in Obesity and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjeldborg, K.; Pedersen, S.B.; Møller, H.J.; Richelsen, B. Reduction in Serum Fibroblast Growth Factor-21 after Gastric Bypass is Related to Changes in Hepatic Fat Content. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Baak, M.A.; Vink, R.G.; Roumans, N.J.T.; Cheng, C.C.; Adams, A.C.; Mariman, E.C.M. Adipose Tissue Contribution to Plasma Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 and Fibroblast Activation Protein in Obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2020, 44, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, F.; Kim, M.; Doridot, L.; Cunniff, J.; Parker, T.; Levine, D.; Hellerstein, M.; Hudgins, L.; Maratos-Flier, E.; Herman, M. A Critical Role for ChREBP-Mediated FGF21 Secretion in Hepatic Fructose Metabolism. Mol. Metab. 2016, 6, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, K.; Takeda, J.; Horikawa, Y. Glucose Induces FGF21 mRNA Expression through ChREBP Activation in Rat Hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 2882–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, C.; Tiwari, V.; Sun, O.; Gonzalez, E. Abstract 2042 The Glycerol-3-P-ChREBP-FGF21 Axis: How Hepatocyte Nuclei Talk to the Brain about Reductive Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 106482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Thakur, S.; Rawat, P.; Jaswal, K.; Dehury, B.; Mondal, P. Hepatic ChREBP Reciprocally Modulates Systemic Insulin Sensitivity in NAFLD. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, I.; Maity, D.K.; Kumar, A.; Sarkar, S.; Bhattacharya, T.; Sahu, A.; Sreedhar, R.; Arumugam, S. Beyond Obesity: Lean Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis from Unveiling Molecular Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Advancement. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 13647–13665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, M.D.; Gao, J.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Gromada, J. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Regulates Energy Metabolism by Activating the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC-1α Pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12553–12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suomalainen, A.; Elo, J.M.; Pietiläinen, K.H.; Hakonen, A.H.; Sevastianova, K.; Korpela, M.; Isohanni, P.; Marjavaara, S.K.; Tyni, T.; Kiuru-Enari, S.; et al. FGF-21 as a Biomarker for Muscle-Manifesting Mitochondrial Respiratory Chain Deficiencies: A Diagnostic Study. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keipert, S.; Ost, M.; Johann, K.; Imber, F.; Jastroch, M.; van Schothorst, E.M.; Keijer, J.; Klaus, S. Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Uncoupling Drives Endocrine Cross-Talk through the Induction of FGF21 as a Myokine. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 306, E469–E482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Jeong, Y.T.; Oh, H.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, J.M.; Kim, Y.N.; Kim, S.S.; Kim, D.H.; Hur, K.Y.; Kim, H.K.; et al. Autophagy Deficiency Leads to Protection from Obesity and Insulin Resistance by Inducing Fgf21 as a Mitokine. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houshmand, M.; Zeinali, V.; Hosseini, A.; Seifi, A.; Danaei, B.; Kamfar, S. Investigation of FGF21 mRNA Levels and Relative Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number Levels and Their Relation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Case-Control Study. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1203019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Borlak, J. A Comparative Genomic Study across 396 Liver Biopsies Provides Deep Insight into FGF21 Mode of Action as a Therapeutic Agent in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Clin. Transl. Med. 2025, 15, e70218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Choi, M.; Jung, S.; Chung, H.; Chang, J.; Kim, J.; Kang, Y.; Lee, J.; Hong, H.; Jun, S.; et al. Differential Roles of GDF15 and FGF21 in Systemic Metabolic Adaptation to the Mitochondrial Integrated Stress Response. iScience 2021, 24, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ishihara, T.; Ibayashi, Y.; Tatsushima, K.; Setoyama, D.; Hanada, Y.; Takeichi, Y.; Sakamoto, S.; Yokota, S.; Mihara, K.; et al. Disruption of Mitochondrial Fission in the Liver Protects Mice from Diet-Induced Obesity and Metabolic Deterioration. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 2371–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, C.; Whyte, J.; Suh, J.; Fan, W.; Collins, B.; Liddle, C.; Yu, R.; Atkins, A.; Naviaux, J.; Li, K.; et al. High-Fat Diet and FGF21 Cooperatively Promote Aerobic Thermogenesis in mtDNA Mutator Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8714–8719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Durán, R.; Ampuero, J.; Maya-Miles, D.; Pastor-Ramírez, H.; Montero-Vallejo, R.; Rivera-Esteban, J.; Álvarez-Amor, L.; Pareja, M.J.; Rico, M.C.; Millán, R.; et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Is a Hepatokine Involved in MASLD Progression. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2024, 12, 1056–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Schönke, M.; Spoorenberg, B.; Lambooij, J.M.; van der Zande, H.J.P.; Zhou, E.; Tushuizen, M.E.; Andreasson, A.C.; Park, A.; Oldham, S.; et al. FGF21 Protects against Hepatic Lipotoxicity and Macrophage Activation to Attenuate Fibrogenesis in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. eLife 2023, 12, e83075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Khoso, M.H.; Kang, K.; He, Q.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xiao, W.; Li, D. FGF21 Ameliorates Hepatic Fibrosis by Multiple Mechanisms. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 7153–7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portincasa, P.; Khalil, M.; Mahdi, L.; Perniola, V.; Idone, V.; Graziani, A.; Baffy, G.; Di Ciaula, A. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: From Pathogenesis to Current Therapeutic Options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, N.N.; Peterson, S.J.; Parikh, M.A.; Jackson, K.A.; Frishman, W.H. Pegozafermin Is a Potential Master Therapeutic Regulator in Metabolic Disorders: A Review. Cardiol. Rev. 2025, 33, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebanso, T.; Taketani, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Amo, K.; Ominami, H.; Arai, H.; Takei, Y.; Masuda, M.; Tanimura, A.; Harada, N.; et al. Paradoxical Regulation of Human FGF21 by Both Fasting and Feeding Signals: Is FGF21 a Nutritional Adaptation Factor? PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, T.; Dutchak, P.; Zhao, G.; Ding, X.; Gautron, L.; Parameswara, V.; Li, Y.; Goetz, R.; Mohammadi, M.; Esser, V.; et al. Endocrine Regulation of the Fasting Response by PPARα-Mediated Induction of Fibroblast Growth Factor 21. Cell Metab. 2007, 5, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badman, M.; Pissios, P.; Kennedy, A.; Koukos, G.; Flier, J.; Maratos-Flier, E. Hepatic Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 Is Regulated by PPARα and Is a Key Mediator of Hepatic Lipid Metabolism in Ketotic States. Cell Metab. 2007, 5, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, F.M.; Chui, P.C.; Antonellis, P.J.; Bina, H.A.; Kharitonenkov, A.; Flier, J.S.; Maratos-Flier, E. Obesity Is a Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 (FGF21)-Resistant State. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2781–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedewald, W.T.; Levy, R.I.; Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of the Concentration of Low-density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Plasma, without Use of the preparative Ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.R.; Hosker, J.P.; Rudenski, A.S.; Naylor, B.A.; Treacher, D.F.; Turner, R.C. Homeostasis Model Assessment: Insulin Resistance and Beta-cell Function from Fasting Plasma Glucose and Insulin Concentrations in Man. Diabetologia 1985, 28, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Meza, S.M.; Maldonado-González, M.; Hernández-Nazara, Z.H.; Martínez-López, E.; Ocampo-González, S.; Bobadilla-Morales, L.; Torres-Baranda, J.R.; Ruíz-Madrigal, B. Development of an Effective and Rapid qPCR for Identifying Human ChREBPα/β Isoforms in Hepatic and Adipose Tissues. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2019, 79, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Color, L.; Hernández-Nazará, Z.H.; Maldonado-González, M.; Navarro-Muñíz, E.; Domínguez-Rosales, J.A.; Torres-Baranda, J.R.; Ruelas-Cinco, E.D.C.; Ramírez-Meza, S.M.; Ruíz-Madrigal, B. Association of the PNPLA2, SCD1 and Leptin Expression with Fat Distribution in Liver and Adipose Tissue from Obese Subjects. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2020, 128, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing Real-time PCR Data by the Comparative C(T) Method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Wilson, L.A.; Behling, C.; Guy, C.; Contos, M.; Cummings, O.; Yeh, M.; Gill, R.; Chalasani, N.; et al. Association of Histologic Disease Activity with Progression of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1912565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metsalu, T.; Vilo, J. ClustVis: A Web Tool for Visualizing Clustering of Multivariate Data Using Principal Component Analysis and Heatmap. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | MHL | MUL | MHO | MUO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 12 | n = 6 | n = 8 | n = 29 | |

| Male/Female n (%) | 2(17)/10(83) | 0/6(100) | 1(13)/7(87) | 4 (18)/25(86) |

| Age (years) | 42.8 ± 3.5 | 37.3 ± 6.5 | 34.3 ± 2.6 | 34.2 ± 1.6 |

| Weight (kg) | 61.8 ± 2.3 | 61.5 ± 2.4 | 102.4 ± 4.9 b | 106.5 ± 4.0 c |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.1 ± 0.6 | 24.1 ± 1.1 | 38.9 ± 1.4 b | 40.0 ± 1.3 c |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 80.2 ± 1.8 | 78.1 ± 1.1 | 114.0 ± 4.0 b | 114.6 ± 3.0 c |

| Body fat (%) | 29.0 ± 2.0 | 32.3 ± 2.0 | 48.1 ± 1.7 b | 46.2 ± 1.2 c |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 87.5 ± 4.4 | 87.2 ± 7.4 | 74.3 ± 5.2 | 83.4 ± 3.0 |

| Insulin (mIU/mL) | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 11.2 ± 2.5 a | 7.8 ± 1.5 b | 19.6 ± 1.8 c,d |

| HOMA-IR | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.5 c,d |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 5.9 ± 1.3 | 5.3 ± 0.5 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 195.2 ± 14.0 | 213.2 ± 15.6 | 149.3 ± 7.1 | 165.2 ± 6.1 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 119.6 ± 15.3 | 170.4 ± 36.4 | 108.4 ± 13.7 | 164.7 ± 13.2 |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | 100.3 ± 16.1 | 136.0 ± 14.2 | 85.7 ± 7.1 | 94.0 ± 5.5 |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 53.0 ± 4.0 | 43.0 ± 4.2 | 41.9 ± 4.1 | 38.4 ± 1.8 |

| VLDL-c (mg/dL) | 24.0 ± 3.1 | 34.0 ± 7.3 | 21.7 ± 2.5 | 32.9 ± 2.6 |

| ALT (U/L) | 23.5 ± 3.5 | 45.8 ± 27.7 | 22.0 ± 2.3 | 41.5 ± 6.1 d |

| AST (U/L) | 34.8 ± 6.3 | 43.8 ± 9.4 | 27.0 ± 1.2 | 39.2 ± 3.2 d |

| GGT (U/L) | 26.0 ± 6.0 | 40.5 ± 15.4 | 24.4 ± 1.9 | 39.8 ± 6.6 |

| MASLD n (%) | 0 | 2 (33.3) | 5 (62.5) b | 25 (85.2) c,e |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palacios Girón, K.M.; Hernandez Nazara, Z.H.; Maldonado-González, M.; Martínez-López, E.; Sánchez Muñoz, M.P.; Bautista López, C.A.; Aguiñaga, M.S.A.; Dominguez-Rosales, J.A.; Vargas-Guerrero, B.; Ruíz-Madrigal, B. Role of ChREBP–PPARα–FGF21 Axis in Metabolic Dysfunction of MASLD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11425. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311425

Palacios Girón KM, Hernandez Nazara ZH, Maldonado-González M, Martínez-López E, Sánchez Muñoz MP, Bautista López CA, Aguiñaga MSA, Dominguez-Rosales JA, Vargas-Guerrero B, Ruíz-Madrigal B. Role of ChREBP–PPARα–FGF21 Axis in Metabolic Dysfunction of MASLD. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11425. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311425

Chicago/Turabian StylePalacios Girón, Karina Mireya, Zamira Helena Hernandez Nazara, Montserrat Maldonado-González, Erika Martínez-López, Martha P. Sánchez Muñoz, Carlos Alfredo Bautista López, Ma. Soledad Aldana Aguiñaga, Jose Alfredo Dominguez-Rosales, Belinda Vargas-Guerrero, and Bertha Ruíz-Madrigal. 2025. "Role of ChREBP–PPARα–FGF21 Axis in Metabolic Dysfunction of MASLD" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11425. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311425

APA StylePalacios Girón, K. M., Hernandez Nazara, Z. H., Maldonado-González, M., Martínez-López, E., Sánchez Muñoz, M. P., Bautista López, C. A., Aguiñaga, M. S. A., Dominguez-Rosales, J. A., Vargas-Guerrero, B., & Ruíz-Madrigal, B. (2025). Role of ChREBP–PPARα–FGF21 Axis in Metabolic Dysfunction of MASLD. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11425. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311425