Creatine and Taurine as Novel Competitive Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase: A Biochemical Basis for Nutritional Modulation of Brain Function

Abstract

1. Introduction

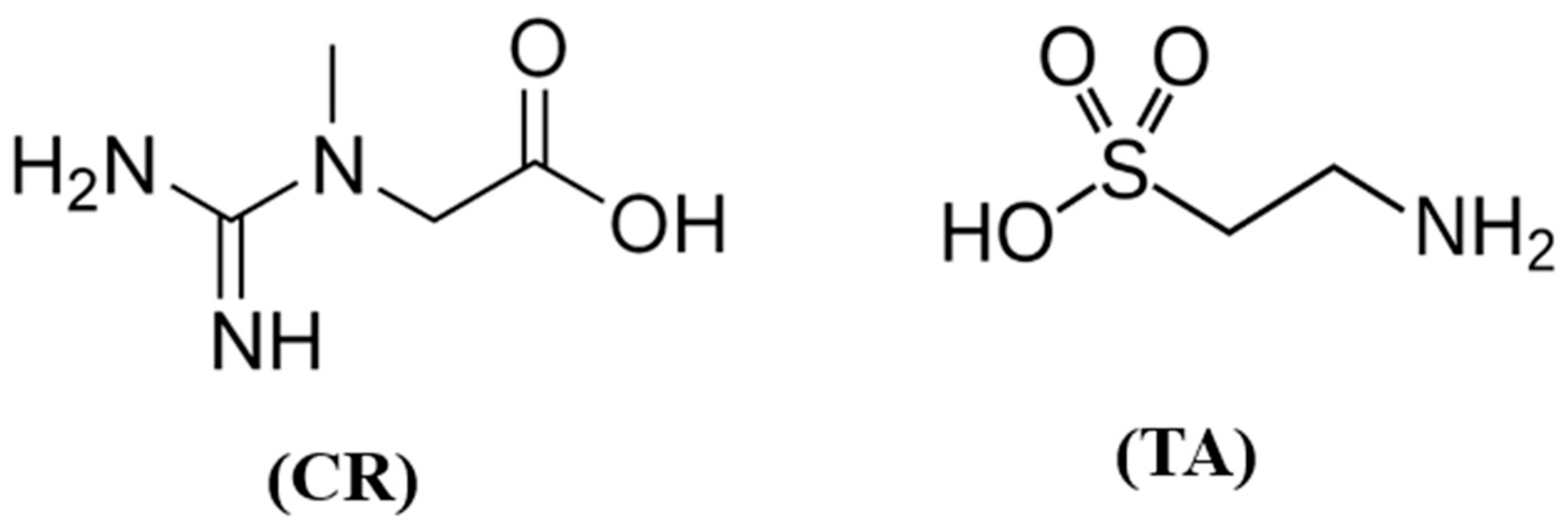

2. Results

2.1. Experiments

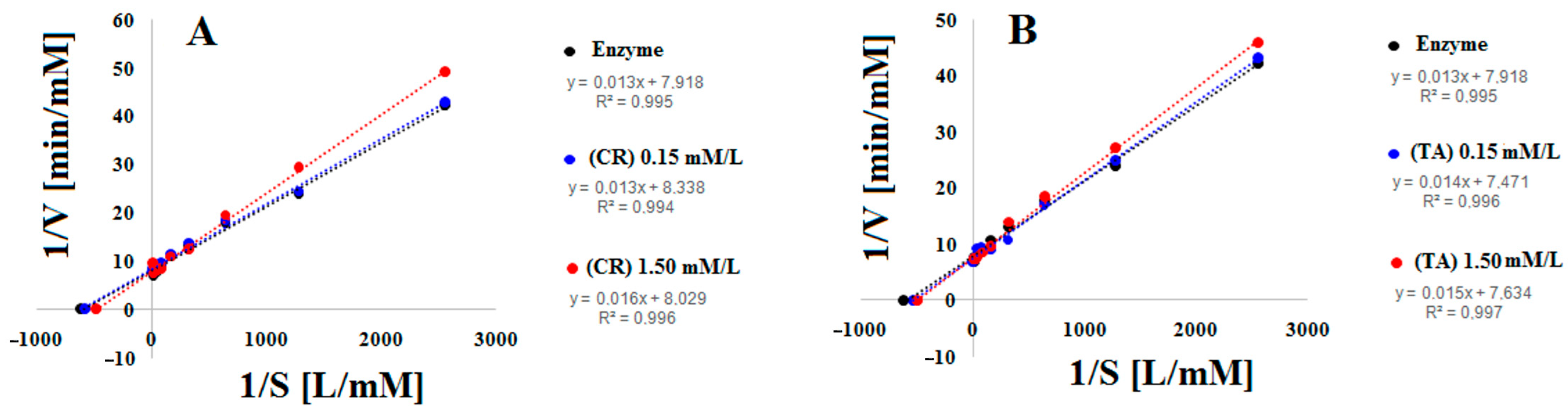

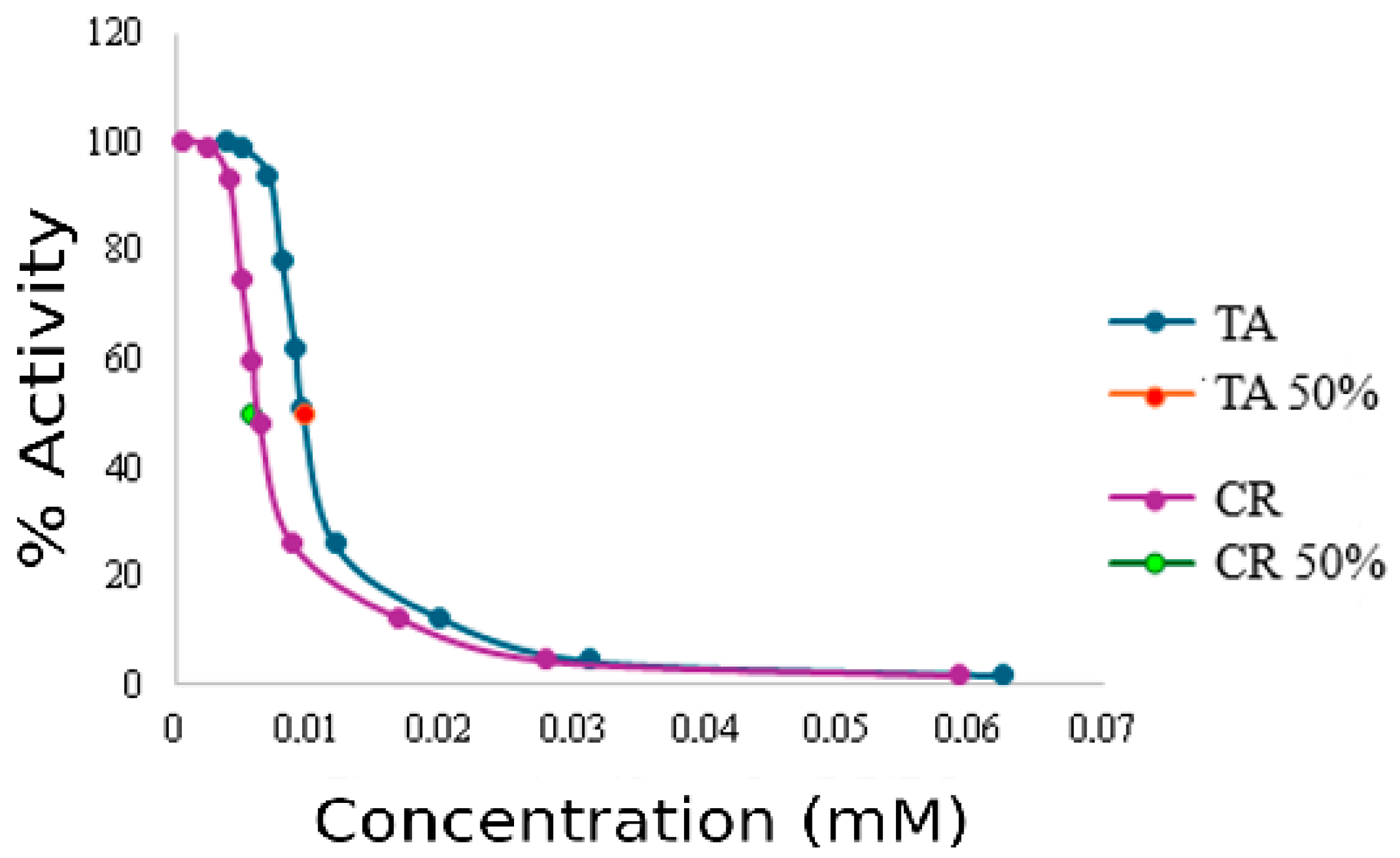

2.2. Analysis

2.3. Discussion

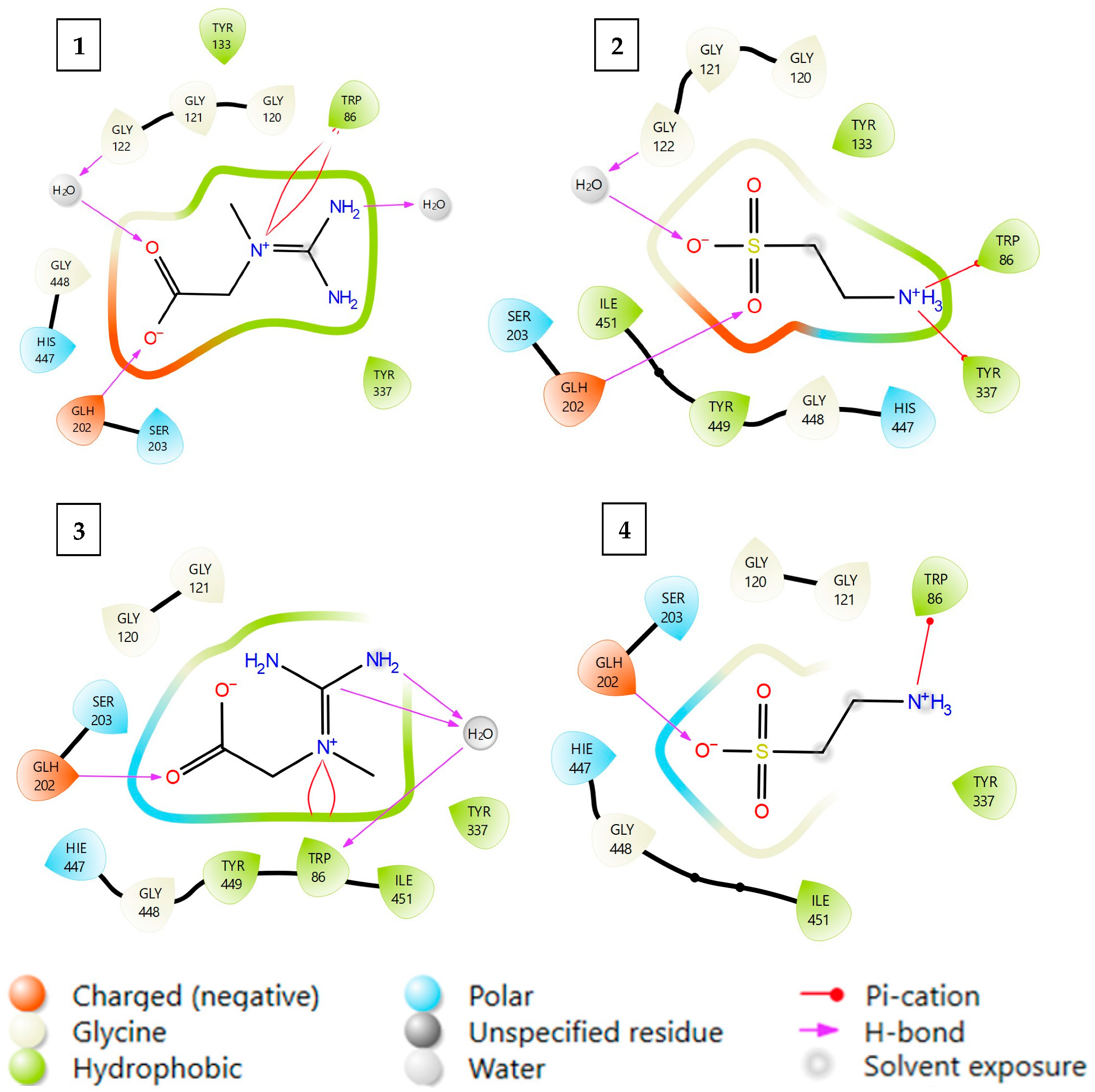

2.4. Molecular Docking

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Chemicals

3.2. Instrumentation

3.3. Preparation of Standards

3.4. Sample Preparation

3.5. Molecular Modelling

3.5.1. Ligand Preparation

3.5.2. Protein Preparation

3.5.3. Docking Protocol

3.5.4. MM/GBSA Calculations

3.6. Kinetic and Statistical Analysis

4. Future Directions and Limitations of the Current Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silman, I.; Sussman, J.L. Acetylcholinesterase: ‘Classical’ and ‘non-classical’ functions and pharmacology. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2005, 5, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çömlekçioğlu, N.; Korkmaz, N.; Yüzbaşıoğlu, M.A.; İmran, U.; Sevindik, M. Mistletoe (Loranthus europaeus Jacq.): Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Anticholinesterase Activities. Prospect. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 22, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, J.S.; Harvey, R.J. Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 6, CD001190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colović, M.B.; Krstić, D.Z.; Lazarević-Pašti, T.D.; Bondžić, A.M.; Vasić, V.M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Pharmacology and toxicology. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2013, 11, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangialasche, F.; Solomon, A.; Winblad, B.; Mecocci, P.; Kivipelto, M. Alzheimer’s disease: Clinical trials and drug development. Lancet Neurol. 2010, 9, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malouf, R.; Birks, J. Donepezil for vascular cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2004, 1, CD004395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Boeve, B.F.; Dickson, D.W.; Halliday, G.; Taylor, J.-P.; Weintraub, D.; Kosaka, K.; Weintraub, D.; Aarsland, D.; Galvin, J.; et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: Fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2017, 89, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, J.T.; Brosnan, M.E. Creatine: Endogenous metabolite, dietary, and therapeutic supplement. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2007, 27, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallimann, T.; Tokarska-Schlattner, M.; Schlattner, U. The creatine kinase system and pleiotropic effects of creatine. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 1271–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.S.; Salomons, G.S.; Hogenboom, F.; Jakobs, C.; Schoffelmeer, A.N. Exocytotic release of acetylcholine by creatine in rat brain slices. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 392, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae, C.; Digney, A.L.; McEwan, S.R.; Bates, T.C. Oral creatine monohydrate supplementation improves brain performance: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 2147–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braissant, O.; Bachmann, C.; Henry, H. Expression and function of AGAT, GAMT and CT1 in the mammalian brain. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2007, 12, 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Solis, M.Y.; Painelli, V.D.S.; Artioli, G.G.; Roschel, H.; Otaduy, M.C.; Gualano, B. Brain creatine depletion in vegetarians? A cross-sectional 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) study. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 111, 1272–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockler-Ipsiroglu, S.; Van Karnebeek, C.D.M.; Longo, N.; Korenke, G.C.; Mercimek-Mahmutoglu, S.; Marquart, I.; Barshop, B.; Grolik, C.; Schlune, A.; Angle, B.; et al. Guanidinoacetate methyltransferase (GAMT) deficiency: Outcomes in 48 individuals and recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and monitoring. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014, 111, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, M.P.; Hiltunen, Y.; Könönen, M.; Kivipelto, M.; Koivisto, A.; Hallikainen, M.; Soininen, H. Decreased brain creatine levels in elderly apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 carriers. J. Neural Transm. 2003, 110, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreider, R.B.; Kalman, D.S.; Antonio, J.; Ziegenfuss, T.N.; Wildman, R.; Collins, R.; Candow, D.G.; Kleiner, S.M.; Almada, A.L.; Lopez, H.L. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: Safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2017, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordji-Nejad, A.; Matusch, A.; Kleedörfer, S.; Patel, H.J.; Drzezga, A.; Elmenhorst, D.; Binkofski, F.; Bauer, A. Single dose creatine improves cognitive performance and induces changes in cerebral high energy phosphates during sleep deprivation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahari, Z.; Jangravi, Z.; Hatef, B.; Valipour, H.; Meftahi, G.H. Creatine supplementation protects spatial memory and long-term potentiation against chronic restraint stress. Behav. Pharmacol. 2023, 34, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambo, L.M.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Schramm, V.G.; Berch, A.M.; Stamm, D.N.; Della-Pace, I.D.; Silva, L.F.A.; Furian, A.F.; Oliveira, M.S.; Fighera, M.R.; et al. Creatine increases hippocampal Na+,K+-ATPase activity via the NMDA-calcineurin pathway. Brain Res. Bull. 2012, 88, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huxtable, R.J. Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol. Rev. 1992, 72, 101–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, S.W.; Kim, H.W. Effects and mechanisms of taurine as a therapeutic agent. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Kimura, H.; Sakai, Y. Taurine-induced increase of the Cl conductance of cerebellar Purkinje cell dendrites in vitro. Brain Res. 1983, 259, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, T.C.; Lin, C.-T.; Song, G.-X.; Thalman, R.H.; Wu, J.Y. Taurine in the rat hippocampus—Localization and postsynaptic action. Brain Res. 1986, 386, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Fan, W.; Ma, Z.; Wen, X.; Wang, W.; Wu, Q.; Huang, H. Taurine improves functional and histological outcomes and reduces inflammation in traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience 2014, 266, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresewicz-Haller, M. Hippocampal region-specific endogenous neuroprotection as an approach in the search for new neuroprotective strategies in ischemic stroke. Fiction or fact? Neurochem. Int. 2023, 162, 105455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Pisklak, D.M.; Grodner, B. Thiamine and Thiamine Pyrophosphate as Non-Competitive Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase—Experimental and Theoretical Investigations. Molecules 2025, 30, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaizer, R.R.; Corrêa, M.C.M.; Spanevello, R.M.; Morsch, V.M.; Mazzanti, C.M.; Gonçalves, J.F.; Schetinger, M.R.C. Acetylcholinesterase activation and enhanced lipid peroxidation after long-term exposure to low levels of aluminum on different mouse brain regions. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005, 99, 1865–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, B.; Schneider, P.; Schäfer, P.; Pietruszka, J.; Gohlke, H. Discovery of new acetylcholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease: Virtual screening and in vitro characterisation. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2021, 36, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Tang, X.C. Effects of huperzine A on acetylcholinesterase isoforms in vitro: Comparison with tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine and physostigmine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 455, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtney, K.D.; Andres, V., Jr.; Featherstone, R.M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1961, 7, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaizer, R.R.; Gutierres, J.M.; Schmatz, R.; Spanevello, R.M.; Morsch, V.M.; Schetinger, M.R.C.; Rocha, J.B.T. In vitro and in vivo interactions of aluminum on NTPDase and AChE activities in lymphocytes of rats. Cell. Immunol. 2010, 265, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuto, M.; Majzúnová, M.; Torcitto, G.; Antonuzzo, S.; Rampulla, F.; Di Fatta, E.; Trovato Salinaro, A. Functional Food Nutrients, Redox Resilience Signaling and Neurosteroids for Brain Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scuto, M.; Modafferi, S.; Rampulla, F.; Zimbone, V.; Tomasello, M.; Spano’, S.; Ontario, M.; Palmeri, A.; Salinaro, A.T.; Siracusa, R.; et al. Redox modulation of stress resilience by Crocus sativus L. for potential neuroprotective and anti-neuroinflammatory applications in brain disorders: From molecular basis to therapy. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2022, 205, 111686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control (Enzyme Only) | Creatine 0.15 mM | Creatine 1.5 mM | Taurine 0.15 mM | Taurine 1.5 mM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope, Km/Vmax [min] | 1.32 × 10−3 ± 0.002 | 1.43 × 10−3 ± 0.003 | 1.55 × 10−3 ± 0.005 | 1.36 × 10−3 ± 0.001 | 1.53 × 10−3 ± 0.004 |

| Km [mM] | 1.73 × 10−3 ± 1.47 × 10−5 | 1.90 × 10−3 ± 1.52 × 10−5 | 2.03 × 10−3 ± 1.37 × 10−5 | 1.80 × 10−3 ± 1.43 × 10−5 | 2.00 × 10−3 ± 1.41 × 10−5 |

| Vmax [mM/min] | 0.131 ± 0.0014 | 0.133 ± 0.0015 | 0.131 ± 0.0014 | 0.132 ± 0.0015 | 0.131 ± 0.0013 |

| Ki [µM] | 199.348 ± 5.21 | 273.905 ± 5.94 | |||

| IC50 [µM] | 0.0056 ± 0.00018 | 0.0097 ± 0.00035 | |||

| Protein PDB Code | Cocrystalised Inhibitor | Docked Ligand | Model | GLIDE XP Score | MM-GBSA [Kcal/Mol] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4EY6 | Competitive Galantamine | Creatine CR | 1 | −7.315 | −34.582 |

| Taurine TA | 2 | −6.501 | −28.971 | ||

| 7XN1 | Non-competitive Tacrine | Creatine CR | 3 | −3.247 | −24.536 |

| Taurine TA | 4 | −2.034 | −19.808 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adamski, P.; Szeleszczuk, Ł.; Gackowski, M.; Grodner, B. Creatine and Taurine as Novel Competitive Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase: A Biochemical Basis for Nutritional Modulation of Brain Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11309. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311309

Adamski P, Szeleszczuk Ł, Gackowski M, Grodner B. Creatine and Taurine as Novel Competitive Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase: A Biochemical Basis for Nutritional Modulation of Brain Function. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11309. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311309

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamski, Paweł, Łukasz Szeleszczuk, Marcin Gackowski, and Błażej Grodner. 2025. "Creatine and Taurine as Novel Competitive Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase: A Biochemical Basis for Nutritional Modulation of Brain Function" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11309. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311309

APA StyleAdamski, P., Szeleszczuk, Ł., Gackowski, M., & Grodner, B. (2025). Creatine and Taurine as Novel Competitive Inhibitors of Acetylcholinesterase: A Biochemical Basis for Nutritional Modulation of Brain Function. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11309. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311309