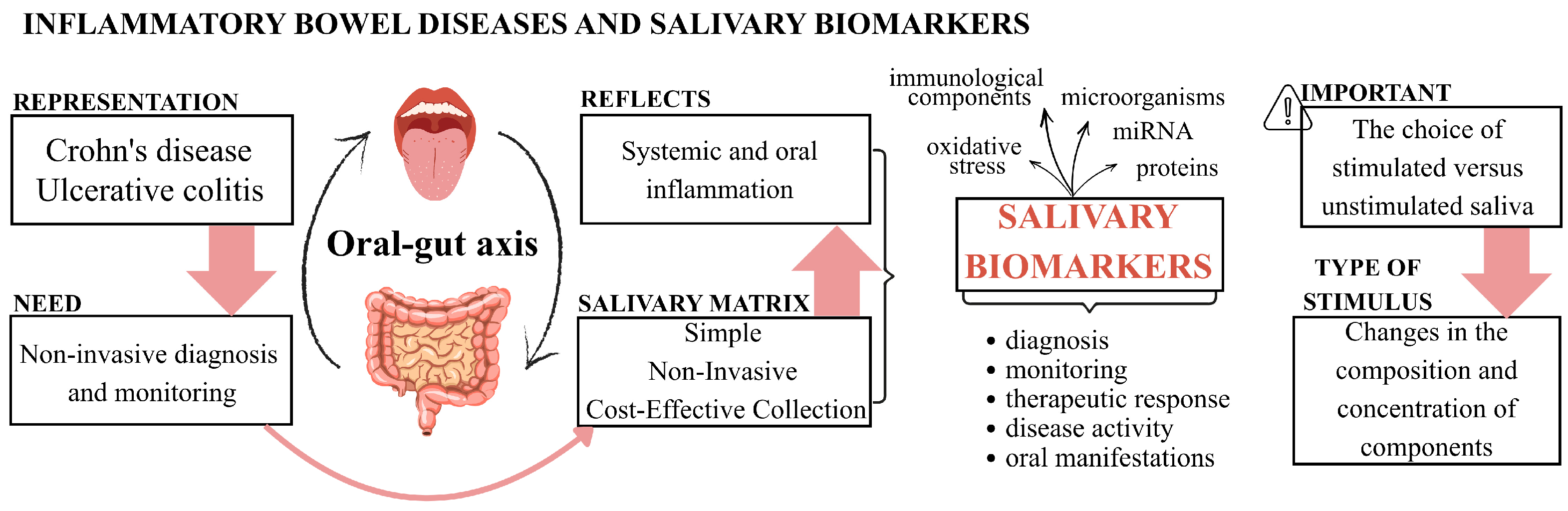

Salivary Biomarkers in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Scoping Review and Evidence Map

Abstract

1. Introduction

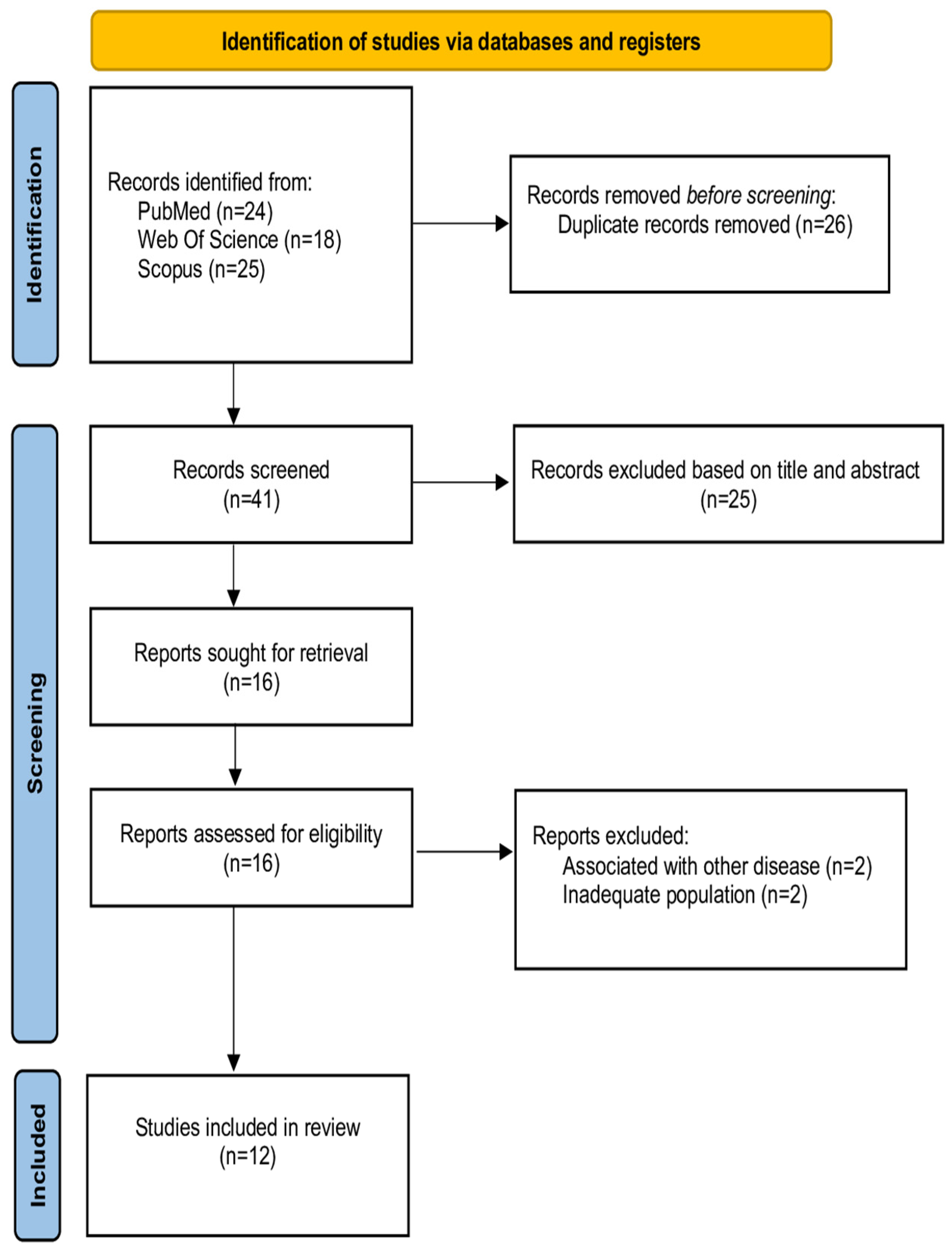

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Literature Search

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Interpretation

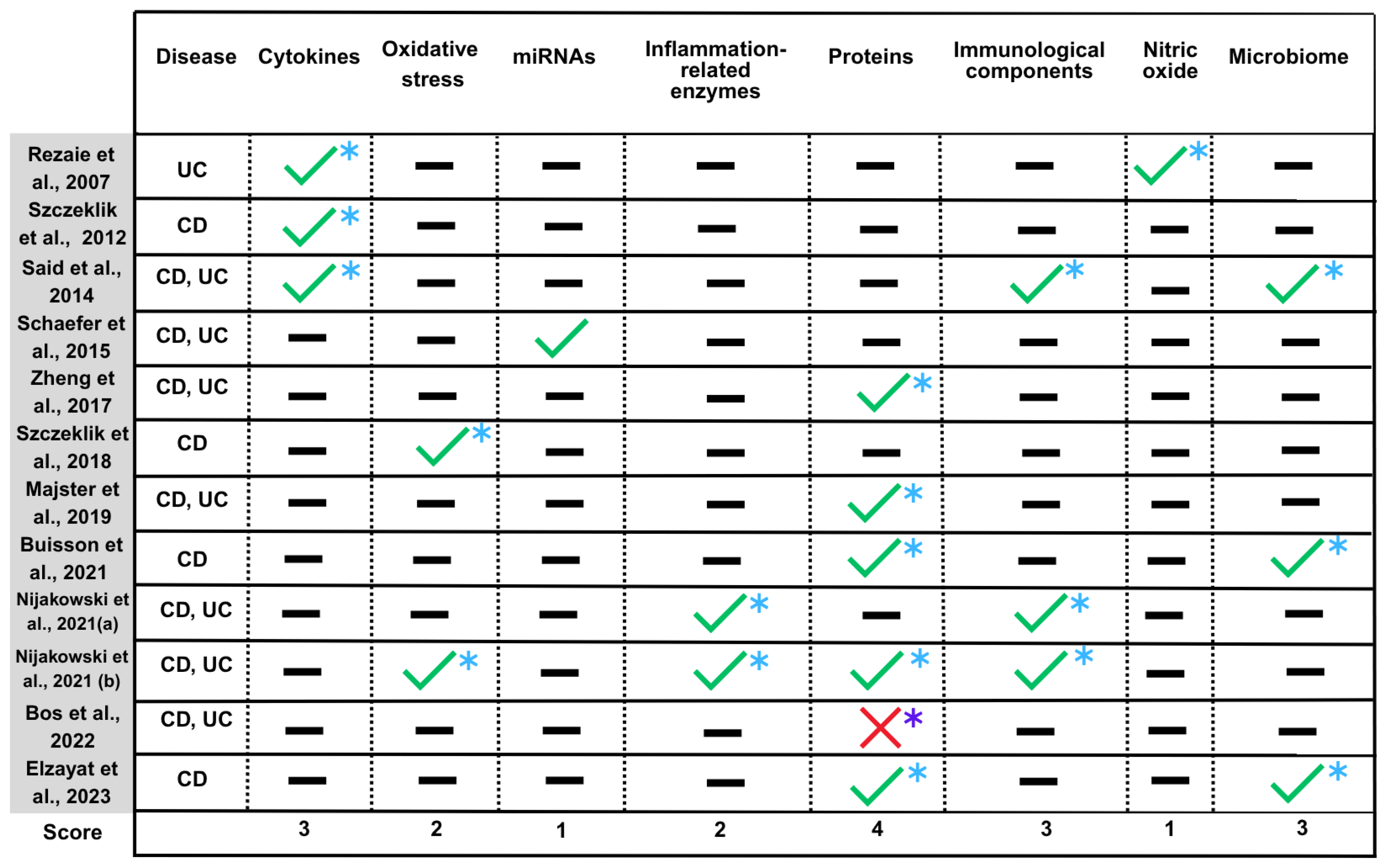

2.5. Quantified Synthesis and Categorization of Biomarkers

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. General and Individual Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

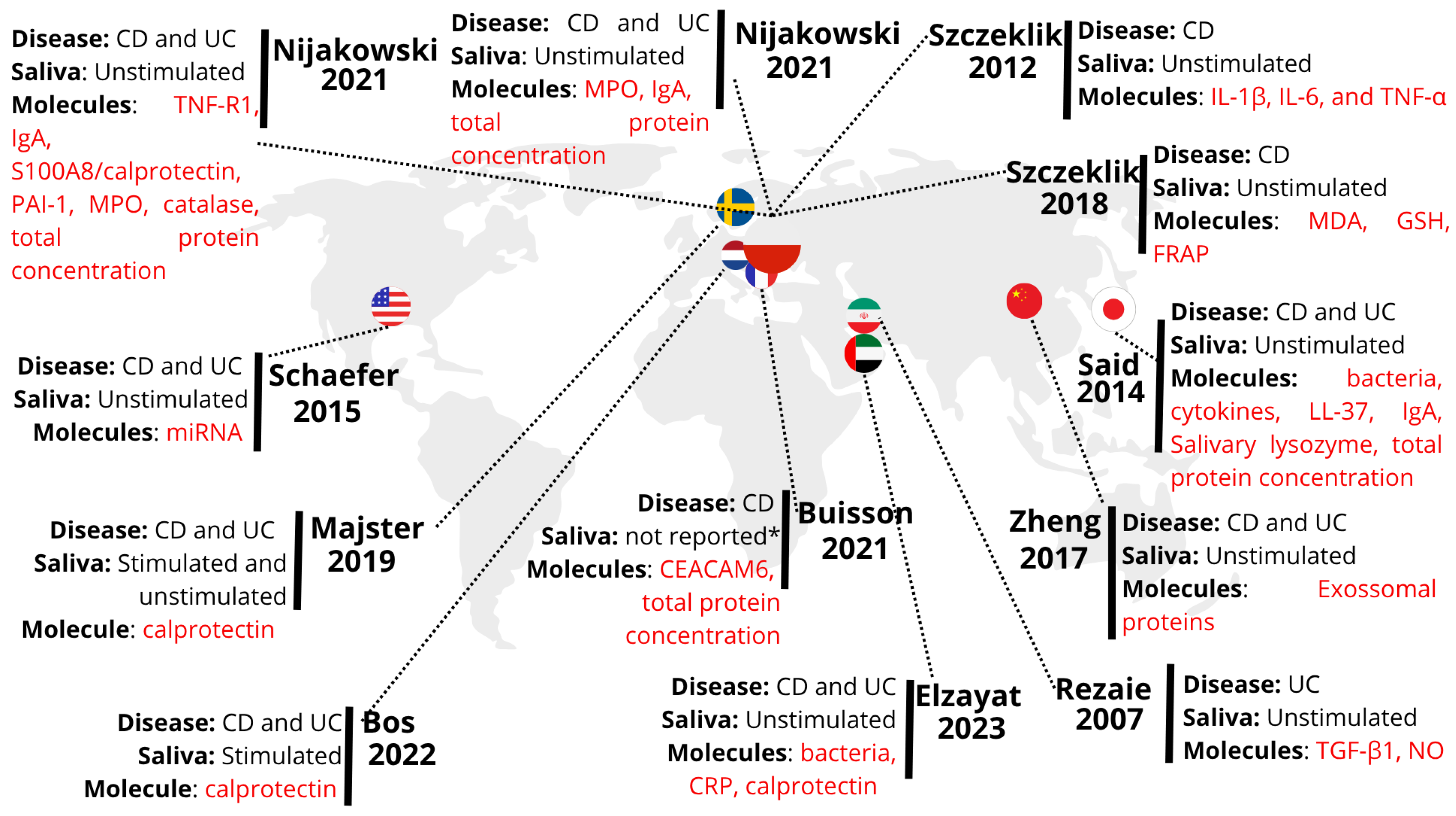

3.3. Basics Characteristics of Each Study

| Author | Objective | Participants | Diagnostic Method Activity | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rezaie et al. [10] | Determine whether salivary concentration of TGF-1 and NO might be helpful to evaluate or anticipate UC severity | UC group (n = 37) Mild activity (n = 21) Moderate activity (n = 8) Severe activity (n = 8) Control group (n = 15) | MTWSI | Unstimulated saliva |

| Szczeklik et al. [11] | Examine the prevalence of oral lesions in adult patients with CD and to investigate whether the salivary levels of interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and TNF-α are associated with the activity and oral manifestations of CD | CD group (n = 95) Activity (n = 52) Mild activity (n = 14) Moderate activity (n = 38) Remission (n = 43) Control group (n = 45) | CDAI | Unstimulated saliva |

| Said et al. [7] | Compare the salivary microbiota of patients with IBD and healthy controls | CD group (n = 21) Remission (n = 13) Activity (n = 8) UC group (n = 14) Mild activity (n = 11) Moderate activity (n = 3) Control group (n = 24) | IOIBD and UC-DAI | Unstimulated saliva |

| Schaefer et al. [14] | Identify differentially expressed miRNAs that could selectively discriminate CD from UC and healthy controls using colon, blood, and saliva specimens | CD group (n = 42) UC group (n = 41) Control group (n = 35) * Only 5 saliva samples per group | Does not report | Unstimulated saliva |

| Zheng et al. [15] | Explore differences in the salivary protein contents of exosomes between patients with IBD and healthy subjects | CD group (n = 11) UC group (n = 37) Control group (n = 10) | Does not report | Unstimulated saliva |

| Szczeklik et al. [17] | Investigate the diagnostic usefulness of selected markers of oxidative stress in the serum and saliva of patients with active and inactive CD compared with healthy controls | CD group (n = 58) Activity (n = 32) Remission (n = 26) Control group (n = 26) | CDAI | Unstimulated saliva |

| Majster et al. [16] | Validate the analysis of calprotectin in saliva under several conditions, and to assess the levels in a small group of IBD patients with active disease, before and after treatment, compared to controls without bowel inflammation | CD group (n = 12) UC group (n = 11) Control group (n = 15) | PGA, UCEIS and SES-CD | Unstimulated and stimulated saliva |

| Buisson et al. [18] | Identify faster and less invasive tools to detect ileal colonization by adherent and invasive E. coli (AIEC) in patients with CD | CD group (n = 102) | CDEIS and CDAI | Does not report |

| Nijakowski et al. [12] | Determine how biologic drugs used in induction therapy would affect the salivary biochemical parameters and how these would be related to the clinical status in IBD patients | CD group (n = 27) UC group (n = 24) | CDAI and the modified Mayo scale | Unstimulated saliva |

| Nijakowski et al. [13] | Compare salivary concentrations of selected biomarkers in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis to determine whether they could be of predictive value for the differential diagnosis | CD group (n = 27) UC group (n = 24) Control group (n = 51) | CDAI and the modified Mayo | Unstimulated saliva |

| Bos et al. [19] | Explore if salivary calprotectin could be used as a reliable non-invasive biomarker in IBD | CD group (n = 42) Remission (n = 34) Activity (n = 5) Missing (n = 3) UC group (n = 21) Remission (n = 15) Activity (n = 2) Missing (n = 4) Control group (n = 11) | HBI score or SCCAI | Stimulated saliva |

| Elzayat et al. [20] | Characterize the compositional changes in the salivary microbiota of patients with CD compared to healthy controls | CD group (n = 40) Activity (n = 10) Remission (n = 30) Control group (n = 40) | CDAI | Unstimulated saliva |

3.4. Methodology Employed in Each Study

4. Discussion

4.1. Geographical Visualization and Spatial Analysis of the Included Studies Based on the Evidence Map

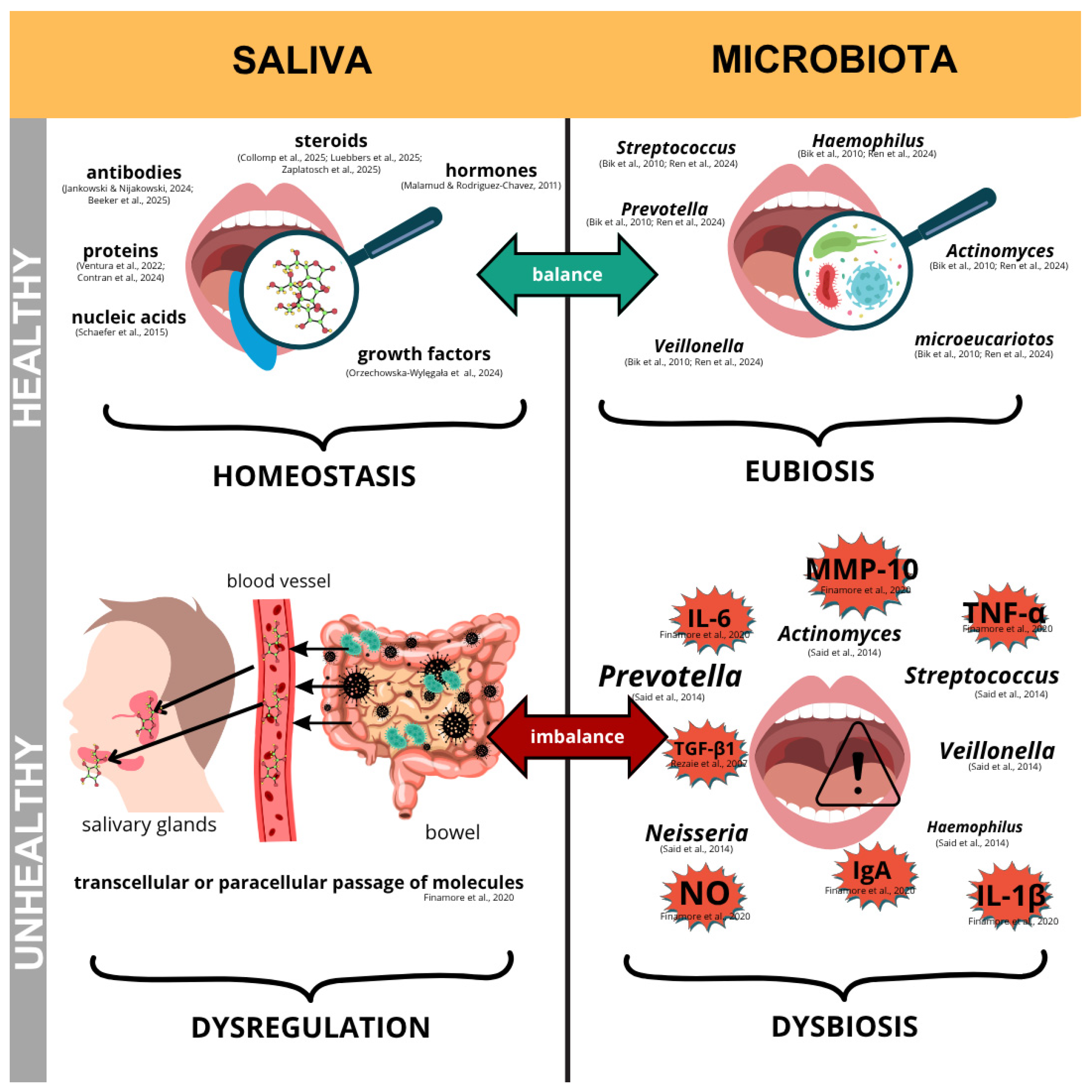

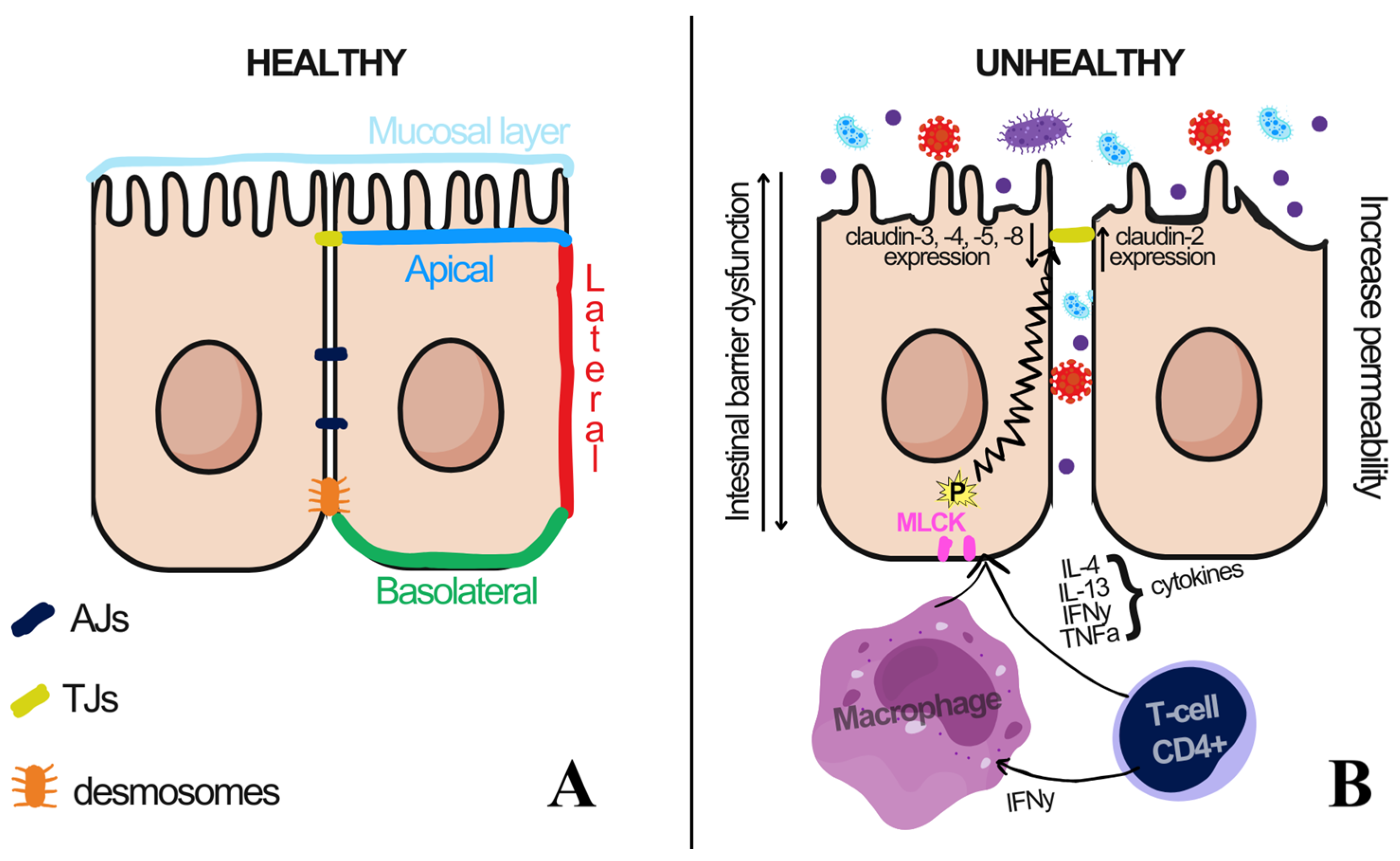

4.2. Schematic of the Relationship Between Oral and Intestinal Health

4.3. Oral Health

4.4. Intestinal Barrier Integrity and Microbiota

4.5. Salivary Parameters—Oxidative Stress

4.6. Salivary microRNA

4.7. Other Promising Inflammatory Molecules in IBD

4.8. Summary of Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| IgA | Immunoglobulin A |

| TNF-R1 | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Type 1 |

| PAI-1 | Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| CEACAM6 | Carcinoembryonic Antigen Related Cell Adhesion Molecule 6 |

| IL-1β | Interleukin IL-1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| TNF-α | Anti-tumor necrosis factor α |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| FRAP | Ferric reducing ability of plasma |

| LL-37 | Cathelicidin-derived antimicrobial peptide |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming Growth Factor-β1 |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| MTWSI | Modified Truelove-Witts severity index |

| CDAI | Crohn’s disease activity index |

| IOIBD | International Organization of Inflammatory Bowel Disease index |

| UC-DAI | Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity Index |

| PGA | Physician global assessment |

| UCEIS | Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity |

| SES-CD | Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease |

| CDEIS | Segmental ileal and total Crohn’s disease endoscopic index of severity |

| HBI | Harvey-Bradshaw index |

| SCCAI | Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index |

| PSMA7 | Proteasome subunit alpha type-7 |

| CAL | Calprotectin |

| AIEC | Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| PRISMA-ScR | Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

References

- Koneru, S.; Tanikonda, R. Salivaomics—A promising future in early diagnosis of dental diseases. Dent. Res. J. 2014, 11, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Suragimath, G.; Patil, S.; Suragimath, D.G.; Sr, A. Salivaomics: A Revolutionary Non-invasive Approach for Oral Cancer Detection. Cureus 2024, 16, e74381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, G.H. The secretion, components, and properties of saliva. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 4, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malamud, D.; Rodriguez-Chavez, I.R. Saliva as a diagnostic fluid. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 55, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. Salivaomics: The current scenario. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2018, 22, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finamore, A.; Peluso, I.; Cauli, O. Salivary Stress/Immunological Markers in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, H.S.; Suda, W.; Nakagome, S.; Chinen, H.; Oshima, K.; Kim, S.; Kimura, R.; Iraha, A.; Ishida, H.; Fujita, J.; et al. Dysbiosis of salivary microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease and its association with oral immunological biomarkers. DNA Res. 2014, 21, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira-Junior, R.; Figueredo, C.M. Periodontal and inflammatory bowel diseases: Is there evidence of complex pathogenic interactions? World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 7963–7972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sáenz-Ravello, G.; Hernández, M.; Baeza, M.; Hernández-Ríos, P. The Role of Oral Biomarkers in the Assessment of Noncommunicable Diseases. Diagnostics 2024, 15, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie, A.; Khalaj, S.; Shabihkhani, M.; Nikfar, S.; Zamani, M.J.; Mohammadirad, A.; Daryani, N.E.; Abdollahi, M. Study on the correlations among disease activity index and salivary transforming growth factor-beta 1 and nitric oxide in ulcerative colitis patients. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1095, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczeklik, K.; Owczarek, D.; Pytko-Polończyk, J.; Kęsek, B.; Mach, T.H. Proinflammatory cytokines in the saliva of patients with active and non-active Crohn’s disease. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewn. 2012, 122, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijakowski, K.; Rutkowski, R.; Eder, P.; Korybalska, K.; Witowski, J.; Surdacka, A. Changes in Salivary Parameters of Oral Immunity after Biologic Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Life 2021, 11, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijakowski, K.; Rutkowski, R.; Eder, P.; Simon, M.; Korybalska, K.; Witowski, J.; Surdacka, A. Potential Salivary Markers for Differential Diagnosis of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Life 2021, 11, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, J.S.; Attumi, T.; Opekun, A.R.; Abraham, B.; Hou, J.; Shelby, H.; Graham, D.Y.; Streckfus, C.; Klein, J.R. MicroRNA signatures differentiate Crohn’s disease from ulcerative colitis. BMC Immunol. 2015, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Chen, F.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; You, P.; Sun, S.; Lin, J.; Chen, N. Salivary exosomal PSMA7: A promising biomarker of inflammatory bowel disease. Protein Cell 2017, 8, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majster, M.; Almer, S.; Boström, E.A. Salivary calprotectin is elevated in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Arch. Oral Biol. 2019, 107, 104528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczeklik, K.; Krzyściak, W.; Cibor, D.; Domagała-Rodacka, R.; Pytko-Polończyk, J.; Mach, T.; Owczarek, D. Markers of lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in the serum and saliva of patients with active Crohn disease. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2018, 128, 362–370. [Google Scholar]

- Buisson, A.; Vazeille, E.; Fumery, M.; Pariente, B.; Nancey, S.; Seksik, P.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Allez, M.; Ballet, N.; Filippi, J.; et al. Faster and less invasive tools to identify patients with ileal colonization by adherent-invasive E. coli in Crohn’s disease. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2021, 9, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, V.; Crouwel, F.; Waaijenberg, P.; Bouma, G.; Duijvestein, M.; Buiter, H.J.; Brand, H.S.; Hamer, H.M.; De Boer, N.K. Salivary Calprotectin Is not a Useful Biomarker to Monitor Disease Activity in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2022, 31, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzayat, H.; Malik, T.; Al-Awadhi, H.; Taha, M.; Elghazali, G.; Al-Marzooq, F. Deciphering salivary microbiome signature in Crohn’s disease patients with different factors contributing to dysbiosis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.E.; Borchers, C.H. Mass spectrometry based biomarker discovery, verification, and validation–quality assurance and control of protein biomarker assays. Mol. Oncol. 2014, 8, 840–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trumbo, T.A.; Schultz, E.; Borland, M.G.; Pugh, M.E. Applied spectrophotometry: Analysis of a biochemical mixture. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2013, 41, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.C.; Shi, H.Y.; Hamidi, N.; Underwood, F.E.; Tang, W.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Wu, J.C.; Chan, F.K.; et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: A systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2017, 390, 2769–2778, Erratum in Lancet 2020, 396, e56.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molodecky, N.A.; Soon, I.S.; Rabi, D.M.; Ghali, W.A.; Ferris, M.; Chernoff, G.; Benchimol, E.I.; Panaccione, R.; Ghosh, S.; Barkema, H.W.; et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.G. The rising burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Poland. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2022, 132, 16257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goździewska, M.; Łyszczarz, A.; Kaczoruk, M.; Kolarzyk, E. Relationship between periodontal diseases and non-specific inflammatory bowel diseases—An overview. Part I. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2024, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klichowska-Palonka, M.; Komsta, A.; Pac-Kożuchowska, E. The condition of the oral cavity at the time of diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagorowicz, E.; Walkiewicz, D.; Kucha, P.; Perwieniec, J.; Maluchnik, M.; Wieszczy, P.; Reguła, J. Nationwide data on epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Poland between 2009 and 2020. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2022, 132, 16194. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, G.B.; Carpenter, G.H. Regulation of salivary gland function by autonomic nerves. Auton. Neurosci. 2007, 133, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzechowska-Wylęgała, B.; Wylęgała, A.; Fiolka, J.Z.; Czuba, Z.; Kryszan, K.; Toborek, M. Selected Saliva-Derived Cytokines and Growth Factors Are Elevated in Pediatric Dentofacial Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, J.; Nijakowski, K. Salivary Immunoglobulin a Alterations in Health and Disease: A Bibliometric Analysis of Diagnostic Trends from 2009 to 2024. Antibodies 2024, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeker, L.; Obadia, T.; Bloch, E.; Garcia, L.; Le Fol, M.; Charmet, T.; Arowas, L.; Artus, R.; Cheny, O.; Cheval, D.; et al. Correlates of Protection Against Symptomatic COVID-19: The CORSER 5 Case-Control Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collomp, K.; Olivier, A.; Castanier, C.; Bonnigal, J.; Bougault, V.; Buisson, C.; Ericsson, M.; Duron, E.; Favory, E.; Zimmermann, M.; et al. Correlation between serum and saliva sex hormones in young female athletes. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2025, 65, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebbers, P.E.; Kriley, L.M.; Eserhaut, D.A.; Andre, M.J.; Butler, M.S.; Fry, A.C. Salivary testosterone and cortisol responses to seven weeks of practical blood flow restriction training in collegiate American football players. Front. Physiol. 2025, 15, 1507445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaplatosch, M.E.; Wideman, L.; McNeil, J.; Sims, J.N.L.; Adams, W.M. Relationship between fluid intake, hydration status and cortisol dynamics in healthy, young adult males. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2025, 21, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bik, E.M.; Long, C.D.; Armitage, G.C.; Loomer, P.; Emerson, J.; Mongodin, E.F.; Nelson, K.E.; Gill, S.R.; Fraser-Liggett, C.M.; Relman, D.A. Bacterial diversity in the oral cavity of 10 healthy individuals. ISME J. 2010, 4, 962–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Chen, M.; Wang, Z.; Han, J.J. Oral microbiota in aging and diseases. Life Med. 2024, 3, lnae024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contran, N.; Arrigoni, G.; Battisti, I.; D’Incà, R.; Angriman, I.; Franchin, C.; Scapellato, M.L.; Padoan, A.; Moz, S.; Aita, A.; et al. Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel diseases share common salivary proteomic pathways. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventura, T.M.O.; Santos, K.O.; Braga, A.S.; Thomassian, L.T.G.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Barbieri, F.A.; Kalva-Filho, C.A.; Faria, M.H.; Magalhães, A.C. Salivary proteomic profile of young adults before and after the practice of interval exercise: Preliminary results. Sport Sci. Health. 2022, 18, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.; Bernstein, Y.; Findler, M. Periodontal disease and its prevention, by traditional and new avenues. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 1504–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, I.L.C.; Van Der Weijden, F.; Doerfer, C.; Herrera, D.; Shapira, L.; Polak, D.; Madianos, P.; Louropoulou, A.; Machtei, E.; Donos, N.; et al. Primary prevention of periodontitis: Managing gingivitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, S71–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Liu, Y.; Du, J.; Xu, J.; Guo, L.; Liu, Y. Regulation of the Host Immune Microenvironment in Periodontitis and Periodontal Bone Remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.J.; Choi, Y.; Ji, S. Gingival fibroblasts from periodontitis patients exhibit inflammatory characteristics in vitro. Arch. Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.C.; Kim, N.; Kadono, Y.; Rho, J.; Lee, S.Y.; Lorenzo, J.; Choi, Y. Osteoimmunology: Interplay between the immune system and bone metabolism. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 24, 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habashneh, R.A.; Khader, Y.S.; Alhumouz, M.K.; Jadallah, K.; Ajlouni, Y. The association between inflammatory bowel disease and periodontitis among Jordanians: A case-control study. J. Periodontal Res. 2012, 47, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberstein, N.F.; Engen, P.A.; Swanson, G.R.; Naqib, A.; Post, Z.; Alutto, J.; Green, S.J.; Shaikh, M.; Lawrence, K.; Adnan, D.; et al. The Bidirectional Effects of Periodontal Disease and Oral Dysbiosis on Gut Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2025, 19, jjae162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojanov, S.; Berlec, A.; Štrukelj, B. The Influence of Probiotics on the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in the Treatment of Obesity and Inflammatory Bowel disease. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherret, J.; Gajjar, B.; Ibrahim, L.; Mohamed Ahmed, A.; Panta, U.R. Dolosigranulum pigrum: Predicting Severity of Infection. Cureus 2020, 12, e9770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, F.; Pérez-Carrasco, V.; García-Salcedo, J.A.; Navarro-Marí, J.M. Bacteremia caused by Veillonella dispar in an oncological patient. Anaerobe 2020, 66, 102285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, M.E.; Israelsson, A.; Moore, E.R.B.; Svensson-Stadler, L.; Wai, S.N.; Pietz, G.; Sandström, O.; Hernell, O.; Hammarström, M.-L.; Hammarström, S. Prevotella jejuni sp. nov., isolated from the small intestine of a child with coeliac disease. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 4218–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Lu, X.; Nossa, C.W.; Francois, F.; Peek, R.M.; Pei, Z. Inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of the distal esophagus are associated with alterations in the microbiome. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 588–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zeng, X.; Ning, K.; Liu, K.-L.; Lo, C.-C.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Wang, D.; Huang, R.; Chang, X.; et al. Saliva microbiomes distinguish caries-active from healthy human populations. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.T.; Zhang, Y.; She, Y.; Goyal, H.; Wu, Z.Q.; Xu, H.G. Diagnostic Utility of Non-invasive Tests for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Umbrella Review. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 920732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surna, A.; Kubilius, R.; Sakalauskiene, J.; Vitkauskiene, A.; Jonaitis, J.; Saferis, V.; Gleiznys, A. Lysozyme and microbiota in relation to gingivitis and periodontitis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2009, 15, CR66–CR73. [Google Scholar]

- Scheper, H.J.; Brand, H.S. Oral aspects of Crohn’s disease. Int. Dent. J. 2002, 52, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janšáková, K.; Escudier, M.; Tóthová, Ľ.; Proctor, G. Salivary changes in oxidative stress related to inflammation in oral and gastrointestinal diseases. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, N.W.; Barnard, K.; Shirlaw, P.J.; Rahman, D.; Mistry, M.; Escudier, M.P.; Sanderson, J.D.; Challacombe, S.J. Serum and salivary IgA antibody responses to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans and Streptococcus mutans in orofacial granulomatosis and Crohn’s disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004, 135, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar Reddy, D. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Peng, J.; Cai, P.; Xia, Y.; Yi, C.; Shang, A.; Akanyibah, F.A.; Mao, F. The emerging role of the gut microbiota and its application in inflammatory bowel disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 179, 117302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groschwitz, K.R.; Hogan, S.P. Intestinal barrier function: Molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 124, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukita, S.; Furuse, M.; Itoh, M. Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, M.G.; Palade, G.E. Junctional complexes in various epithelia. J. Cell Biol. 1963, 17, 375–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berin, M.C.; Yang, P.C.; Ciok, L.; Waserman, S.; Perdue, M.H. Role for IL-4 in macromolecular transport across human intestinal epithelium. Am. J. Physiol. 1999, 276, C1046–C1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, R.M.; Li, C.; Sun, S.; Ahn, J.-H.; Dogan, B.; Barlogio, C.J.; Broberg, C.A.; Franks, A.R.; Bulik-Sullivan, E.; Carroll, I.M.; et al. A consortia of clinical E. coli strains with distinct in vitro adherent/invasive properties establish their own co-colonization niche and shape the intestinal microbiota in inflammation-susceptible mice. Microbiome 2023, 11, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnich, N.; Carvalho, F.A.; Glasser, A.-L.; Darcha, C.; Jantscheff, P.; Allez, M.; Peeters, H.; Bommelaer, G.; Desreumaux, P.; Colombel, J.-F.; et al. CEACAM6 acts as a receptor for adherent-invasive E. coli, supporting ileal mucosa colonization in Crohn disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1566–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheeseman, K.H. Mechanisms and effects of lipid peroxidation. Mol. Asp. Med. 1993, 14, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, R.K.; Wilson, K.T. Nitric Oxide in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2003, 9, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaglio, A.E.V.; Santaella, F.J.; Rodrigues, M.A.M.; Sassaki, L.Y.; Di Stasi, L.C. MicroRNAs expression influence in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: A pilot study for the identification of diagnostic biomarkers. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 7801–7812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ridzon, D.; Wong, L.; Chen, C. Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in normal human tissues. BMC Genom. 2007, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.C.S.; Quaglio, A.E.V.; Grillo, T.G.; Di Stasi, L.C.; Sassaki, L.Y. MicroRNAs in inflammatory bowel disease: What do we know and what can we expect? World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 2184–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powrózek, T.; Malecka-Massalska, T. Is microRNA-31 a key regulator of breast tumorigenesis? J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 564–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, T.X.; Kryczek, I.; Zhao, L.; Zhao, E.; Kuick, R.; Roh, M.H.; Vatan, L.; Szeliga, W.; Mao, Y.; Thomas, D.G.; et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells enhance stemness of cancer cells by inducing microRNA101 and suppressing the corepressor CtBP2. Immunity 2013, 39, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Li, X.; He, Q.; Gao, J.; Gao, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, F. miR-142-3p regulates the formation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells in vertebrates. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 1356–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, T.; Huang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.-M.; Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Guo, A.-Y. MicroRNA regulatory pathway analysis identifies miR-142-5p as a negative regulator of TGF-β pathway via targeting SMAD3. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 71504–71513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Síbia, C.d.F.d.; Quaglio, A.E.V.; de Oliveira, E.C.S.; Pereira, J.N.; Ariede, J.R.; Lapa, R.M.L.; Severino, F.E.; Reis, P.P.; Sassaki, L.Y.; Saad-Hossne, R. microRNA-mRNA Networks Linked to Inflammation and Immune System Regulation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, K.M.; Gulati, A.S. The “Gum-Gut” Axis in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Hypothesis-Driven Review of Associations and Advances. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 620124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, A.; Schulte, C.; Schatton, R.; Becker, A.; Cario, E.; Goebell, H.; Dignass, A.U. Transforming growth factor-beta and hepatocyte growth factor plasma levels in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000, 12, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, H.A.; Tchernev, V.T.; Satyaraj, E.; Lejnine, S.; Kotler, G.; Kingsmore, S.F.; Patel, D.D. Protein microarray analysis of disease activity in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease demonstrates elevated serum PLGF, IL-7, TGF-beta1, and IL-12p40 levels in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patients in remission versus active disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 100, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Design | Analysis | Molecules/Microorganisms in Saliva | Mean Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rezaie et al. [10] | CC | ELISA | TGF-β1, NO | - ↑ TGF-β1 and NO (p > 0·05) - NO ↔ TGF-β1 (no corr., p = 0.74) |

| Szczeklik et al. [11] | PS | ELISA Oral examinations | IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α | - ↔ salivary flow - ↑ IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α (active > inactive & ctrl; p < 0.05) - IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α ↔ (inactive CD vs. ctrl) - ↑ IL-6, TNF-α (saliva + lesions, active CD; p < 0.05); IL-1β ↔ (p = 0.282) |

| Said et al. [7] | CC | Barcoded 16S rRNA pyrosequencing Immunoassays | Microbiota, cytokines, LL-37, IgA, Salivary lysozyme, total protein concentration | - ↑ Bacteroidetes and ↓ Proteobacteria in CD and UC vs. control (p < 0.01; p < 0.05) - ↔ Phylum level: UC vs. CD - ↑ Prevotella (phy. Bacteroidetes) and Veillonella (phy. Firmicutes): IBD vs. control (p < 0.01) - ↓ Streptococcus and Haemophilus: IBD vs. control (p < 0.05) - Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative ↔ (among all groups) - Lysozyme ↓ (IBD vs. ctrl; p < 0.01); IgA, LL37 ↑ (IBD vs. ctrl; p < 0.05) |

| Schaefer et al. [14] | CC | Microarrays Isolation of RNA and real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) | miRNA and potential miRNA target genes | - miR-101, miR-21, miR-31, miR-142-3p ↑ (IBD vs. ctrl; p < 0.05) - miR-142-5p ↓ (UC vs. ctrl; p < 0.05) - miR-101 → potential key regulator in IBD |

| Zheng et al. [15] | CC | Extraction of exosomes from saliva Western blotting Shotgun mass spectroscopy analysis | Exosomal proteins and PSMA7 protein | - 8 proteins present only in CD and UC - PSMA7 ↑ (CD and UC vs. ctrl) - PSMA7 ↓ (remission vs. active disease) |

| Szczeklik et al. [17] | CC | Colorimetric method based on thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reactivity FRAP method Ellman method | MDA, GSH, FRAP levels | - MDA ↑ (active CD vs. inactive CD and ctrl; p < 0.01) - FRAP ↓ (CD vs. ctrl) - GSH ↓ (active CD vs. inactive CD and ctrl; p < 0.01) |

| Majster et al. [16] | CC | Immunoassays | Calprotectin levels (CAL) | - CAL higher in stimulated vs. unstimulated saliva (fasting and non-fasting; p < 0.001) - CAL 4.0-fold ↑ in stimulated saliva of IBD patients (p = 0.001) - CAL ↑ in CD vs. ctrl (unstimulated p = 0.011; stimulated p = 0.002) - CAL ↑ in UC vs. ctrl (stimulated saliva; p = 0.021) - Salivary CAL higher in ileal CD and treatment-naïve patients; no correlation with disease extension |

| Buisson et al. [18] | MP | E. coli counting and identification Invasion assay ERIC-PCR Anti-E. coli antibody measurement and quantification CEACAM6 by ELISA | CEACAM6 levels | - AIEC colonized ileum in 24.5% of CD patients (25/102) - Global invasive ability of ileal total E. coli ↑ in AIEC-positive vs. AIEC-negative patients (p = 0.0007) - Salivary CEACAM6 positively correlated with ileal CEACAM6 (healthy areas p < 0.0001; ulcerated zones p = 0.0082; overall p < 0.0001) - Salivary CEACAM6 levels not different in AIEC-positive vs. AIEC-negative patients (p = 0.45) |

| Nijakowski et al. [12] | PC | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays Bradford method | Myeloperoxidase (MPO), immunoglobulin A (IgA) and total protein levels | - pH and stimulated flow ↑ in CD and UC - No difference in salivary flow rate, IgA, or MPO between CD patients with successful vs. unsuccessful therapy - IgA and MPO ↑ in UC responders to biological therapy (p = 0.009 and p = 0.004, respectively) |

| Nijakowski et al. [13] | PC | Immunoassays and enzymatic colorimetric assays Bradford method | IgA, S100A8/calprotectin, TNF-R1, PAI-1, MPO, catalase, total protein levels | - IgA, CAL, MPO ↓ in CD and UC (p < 0.05) - TNF-R1, catalase ↓ in UC (p < 0.05) - Salivary protein concentration ↓ in IBD vs. ctrl (p < 0.001) - PAI-1 similar across all groups |

| Bos et al. [19] | ECSC | Particle-enhanced turbidimetric immunoassay | Calprotectin (CAL) | - No significant correlation: salivary CAL vs. fecal CAL (p = 0.495) and salivary CAL vs. plasma CP (p = 0.223) - No significant difference in salivary CAL between active disease and remission |

| Elzayat et al. [20] | CC | CRP and CAL concentrations were determined by ELISA kits Microbiome | Microbiota, CAL, C-reactive protein (CRP) | - CD: salivary CRP, CAL ↑ vs. ctrl, non-significant - Salivary CAL ↑ in caries vs. periodontal disease (p = 0.009); CRP no significant difference (p > 0.05) - Five species ↑ in CD vs. ctrl: Veillonella dispar, Prevotella jejuni, Dolosigranulum pigrum, Lactobacillus backii, Megasphaera stantonii - Phyla level: Fusobacteria in CD with good oral health (H); Actinobacteria in periodontal disease (P) - Genus level: Bacteroides (H), Streptococcus (P), Fusobacteria (CD + caries, C), Lactobacillus (P + C) - Species level: H: Neisseria subflava, Tannerella forsythia, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella jejuni, P. dentalis, P. enoeca, Bacteroides fragilis, B. intestinalis; P:. mutans, S. pyogenes, S. oralis, S. viridans; P + C: S. mutans, L. fermentum, L. acidophilus - Simonsiella dominant in CD patients treated only with monoclonal antibodies - Simonsiella muelleri exclusive to monoclonal antibody therapy; E. coli, S. enterica ↑ in triple therapy - Genus level: Porphyromonas ↑ in newly diagnosed; Pasteurella ↑ in long-term CD - Klebsiella pneumoniae detected in CD > 10 years - Genus level: Acetoanaerobium, Mycoplasma ↑ in active CD; Schaalia, Cardiobacterium, Leptotrichia, Capnocytophaga ↑ in inactive CD - Frequent relapsers: Prevotella spp., Simonsiella muelleri; infrequent: Clostridium, Lactobacillus, Ruminococcus - Seven oral species overlapped with IBD medications and oral health, including L. jensenii, E. durans, and A. pittii. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, K.O.; Sassaki, L.Y.; Brusco De Freitas, M.; Baima, J.P.; Faria, M.H.; Bizotto, A.L.; Benício, J.P.; Magalhães, A.C. Salivary Biomarkers in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Scoping Review and Evidence Map. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211195

Santos KO, Sassaki LY, Brusco De Freitas M, Baima JP, Faria MH, Bizotto AL, Benício JP, Magalhães AC. Salivary Biomarkers in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Scoping Review and Evidence Map. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211195

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Karina Oliveira, Ligia Yukie Sassaki, Maiara Brusco De Freitas, Julio Pinheiro Baima, Murilo Henrique Faria, Anna Luisa Bizotto, Júlia Pardini Benício, and Ana Carolina Magalhães. 2025. "Salivary Biomarkers in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Scoping Review and Evidence Map" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211195

APA StyleSantos, K. O., Sassaki, L. Y., Brusco De Freitas, M., Baima, J. P., Faria, M. H., Bizotto, A. L., Benício, J. P., & Magalhães, A. C. (2025). Salivary Biomarkers in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Scoping Review and Evidence Map. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211195