Late vs. Early Preeclampsia

Abstract

1. Introduction

Definitions of Preeclampsia

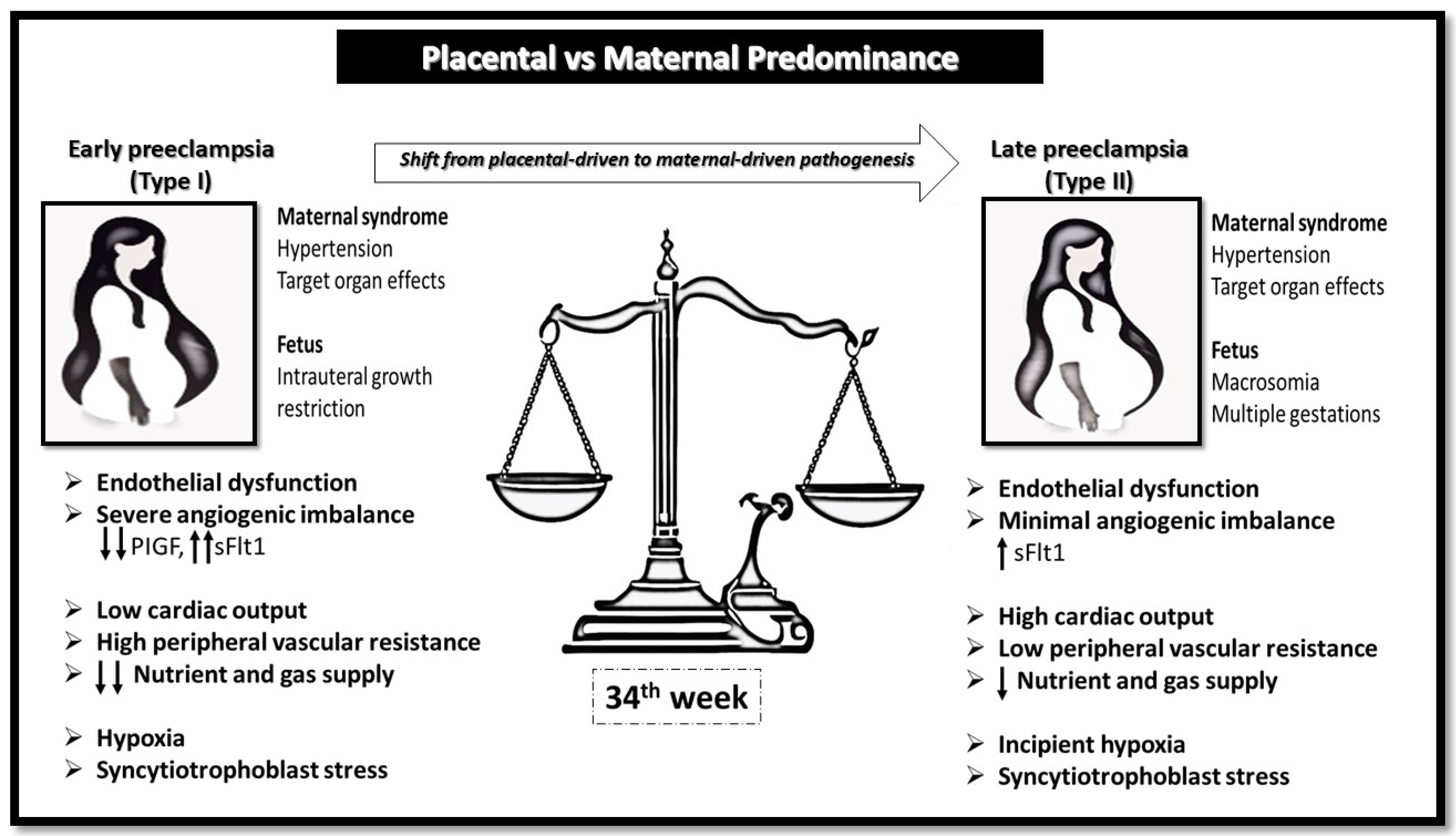

2. Pathophysiologic Mechanisms

2.1. Abnormal Placentation

2.2. Maternal Cardiovascular Adaptations During Pregnancy

2.3. Angiogenic and Antiangiogenic Factors

2.4. Monocytes and Macrophages in Preeclampsia

2.5. Cytokines and Inflammatory Imbalance

2.6. Oxidative Stress

2.7. Innate Immune Pathways in Preeclampsia: NK Cells, Toll-like Receptors and Pentraxins

2.8. The Immune Maladaptation Hypothesis

2.9. Interaction Between Immunologic Alterations and the Placental Metabolic Syndrome in PE

2.10. Molecular Insights into Early- and Late-Onset Preeclampsia

2.11. Risk Factors

2.12. Ultrasonographic Markers and Diagnostic Role of Imaging in Preeclampsia

2.13. Prevention of Preeclampsia

2.14. Insights Gained from First Pregnancies

2.15. The Impact of the Fetus on Maternal Cardiac Remodeling

3. Emerging Mechanisms and Gene Therapy Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EGF | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| EOPE | Early onset preeclampsia |

| HELLP | Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets |

| HLA | human leukocyte antigen |

| FGR | fetal growth restriction |

| IL- | interleukin- |

| IPGs | inositol phosphoglycans |

| KIR | killer immunoglobulin-like receptors cells |

| NF-kB | Nuclear factor-kB |

| LOPE | Late onset preeclampsia |

| PE | Preeclampsia |

| PlGF | Placental Growth Factor |

| PTX3 | Plasma pentraxin 3 |

| RAAS | renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system |

| sEng | soluble endoglin |

| sFlt1 | soluble Fms-like tyrosine kinase |

| STBMs | Syncytiotrophoblast microparticles |

| sVEGFR-1 | soluble Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-β |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TLRs | toll-like receptors |

| TREM2 | triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 |

| VCAM | Vascular cell adhesion molecule |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VEGFR-1 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 |

References

- Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Toh, S.; Cnattingius, S. Risk of preeclampsia in first and subsequent pregnancies: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2009, 338, b2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, A.K.; Larsson, A.; Eriksson, U.J.; Nash, P.; Norden-Lindeberg, S.; Olovsson, M. Placental Growth Factor and Soluble Fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase-1 in Early-Onset and Late-Onset Preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 109, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepan, H.; Unversucht, A.; Wessel, N.; Faber, R. Predictive Value of Maternal Angiogenic Factors in Second-Trimester Pregnancies with Abnormal Uterine Perfusion. Hypertension 2007, 49, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Syngelaki, A.; Nicolaides, K.H.; von Dadelszen, P.; Magee, L.A. Impact of New Definitions of Preeclampsia at Term on Identification of Adverse Maternal and Perinatal Outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 224, 518.e1–518.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagel, S.; Cohen, S.M.; Goldman-Wohl, D. An Integrated Model of Preeclampsia: A Multifaceted Syndrome of the Maternal Cardiovascular–Placental–Fetal Array. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S963–S972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valensise, H.; Vasapollo, B.; Gagliardi, G.; Novelli, G.P. Early and Late Preeclampsia: Two Different Maternal Hemodynamic States in the Latent Phase of the Disease. Hypertension 2008, 52, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crispi, F.; Llurba, E.; Dominguez, C.; Martin-Gallan, P.; Cabero, L.; Gratacós, E. Predictive Value of Angiogenic Factors and Uterine Artery Doppler for Early- versus Late-Onset Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 31, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddeberg, B.S.; Sharma, R.; O’Driscoll, J.M.; Kaelin Agten, A.; Khalil, A.; Thilaganathan, B. Cardiac Maladaptation in Obese Pregnant Women at Term. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 54, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, K.; Wright, A.; Sarno, M.; Kametas, N.A.; Nicolaides, K.H. Comparison of Ophthalmic Artery Doppler with PlGF and sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio at 35–37 Weeks’ Gestation in Prediction of Imminent Preeclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 59, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, D.M.; Delles, C.; Dominiczak, A.F. Novel Biomarkers for Predicting Preeclampsia. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2008, 18, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauster, M.; Moser, G.; Orendi, K.; Huppertz, B. Factors Involved in Regulating Trophoblast Fusion: Potential Role in the Development of Preeclampsia. Placenta 2009, 30 (Suppl. A), S49–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, P.; Black, S.; Huppertz, B. Endovascular Trophoblast Invasion: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Intrauterine Growth Retardation and Preeclampsia. Biol. Reprod. 2003, 69, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatt, L.; Webster, R.P. Vascular Biology of Preeclampsia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 7, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, C.W.; Sargent, I.L. Placental Stress and Preeclampsia: A Revised View. Placenta 2009, 30 (Suppl. A), S38–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, G.J.; Woods, A.W.; Jauniaux, E.; Kingdom, J.C. Rheological and Physiological Consequences of Conversion of the Maternal Spiral Arteries for Uteroplacental Blood Flow During Pregnancy. Placenta 2009, 30, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reister, F.; Kingdom, J.C.; Ruck, P.; Marzusch, K.; Heyl, W.; Pauer, U.; Kaufmann, P.; Rath, W. Altered Protease Expression by Periarterial Trophoblast Cells in Severe Early-Onset Preeclampsia with IUGR. J. Perinat. Med. 2006, 34, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchiorre, K.; Giorgione, V.; Thilaganathan, B. The Placenta and Preeclampsia: Villain or Victim? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S954–S962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispi, F.; Dominguez, C.; Llurba, E.; Martin-Gallan, P.; Cabero, L.; Gratacós, E. Placental Angiogenic Growth Factors and Uterine Artery Doppler Findings for Characterization of Different Subsets in Preeclampsia and in Isolated Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 195, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchiorre, K.; Sharma, R.; Khalil, A.; Thilaganathan, B. Maternal Cardiovascular Function in Normal Pregnancy: Evidence of Maladaptation to Chronic Volume Overload. Hypertension 2016, 67, 754–762. [Google Scholar]

- Gyselaers, W. Preeclampsia Is a Syndrome with a Cascade of Pathophysiologic Events. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guller, S. Role of the Syncytium in Placenta-Mediated Complications of Preeclampsia. Thromb. Res. 2009, 124, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kim, Y.K.; Lee, D.S.; Jeong, D.H.; Sung, M.S.; Song, J.Y.; Kim, K.T.; Shin, J.E. The Relationship of the Level of Circulating Antiangiogenic Factors to the Clinical Manifestations of Preeclampsia. Prenat. Diagn. 2009, 29, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grill, S.; Rusterholz, C.; Zanetti-Dallenbach, R.; Tercanli, S.; Holzgreve, W.; Hahn, S.; Lapaire, O. Potential Markers of Preeclampsia—A Review. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2009, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudejans, C.B.; van Dijk, M.; Oosterkamp, M.; Lachmeijer, A.M.; Blankenstein, M.A. Genetics of Preeclampsia: Paradigm Shifts. Hum. Genet. 2007, 120, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppertz, B. Placental Origins of Preeclampsia: Challenging the Current Hypothesis. Hypertension 2008, 51, 970–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Umar, S.; Amjedi, M.; Iorga, A.; Sharma, S.; Nadadur, R.D.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Eghbali, M. New Frontiers in Heart Hypertrophy during Pregnancy. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012, 2, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chung, E.; Leinwand, L.A. Pregnancy as a Cardiac Stress Model. Cardiovasc. Res. 2014, 101, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, E.; Yeung, F.; Leinwand, L.A. Calcineurin Activity Is Required for Cardiac Remodeling in Pregnancy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013, 100, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalà, M. Influence of Estrogens on Uterine Vascular Adaptation in Normal and Preeclamptic Pregnancies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliqueo, M.; Echiburu, B.; Crisosto, N. Sex Steroids Modulate Uterine-Placental Vasculature: Implications for Obstetrics and Neonatal Outcomes. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyselaers, W. Hemodynamic Pathways of Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S988–S1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonck, S.; Lanssens, D.; Staelens, A.S.; Tomsin, K.; Oben, J.; Mesens, T.; Gyselaers, W. Obesity in Pregnancy Causes a Volume Overload in Third Trimester. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 49, e13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, M.J.E.; van der Sande, F.M.; van den Berghe, F.; Leunissen, K.M.L.; Kooman, J.P. Fluid Overload and Inflammation Axis. Blood Purif. 2018, 45, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benschop, L.; Schalekamp-Timmermans, S.; Broere-Brown, Z.A.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W.; Dubois, A.M.; van Lennep, J.E.R.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Steegers, E.A.P. Placental Growth Factor as an Indicator of Maternal Cardiovascular Risk after Pregnancy. Circulation 2019, 139, 1698–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aasa, K.L.; Zavan, B.; Luna, R.L.; Wong, P.G.; Ventura, N.M.; Tse, M.Y.; Carmeliet, P.; Adams, M.A.; Pang, S.C.; Croy, B.A. Placental Growth Factor Influences Maternal Cardiovascular Adaptation to Pregnancy in Mice. Biol. Reprod. 2015, 92, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgione, V.; Di Fabrizio, C.; Giallongo, E.; Perelli, F.; Fiolna, M.; Khalil, A.; Thilaganathan, B. Angiogenic Markers and Maternal Echocardiographic Indices in Women with Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 63, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gana, N.; Sarno, M.; Vieira, N.; Wright, A.; Charakida, M.; Nicolaides, K.H. Ophthalmic Artery Doppler at 11–13 Weeks’ Gestation in Prediction of Preeclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 59, 731–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbone, E.; Sapantzoglou, I.; Nunez-Cerrato, M.E.; Wright, A.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Charakida, M. Relationship between Ophthalmic Artery Doppler and Maternal Cardiovascular Function. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 733–738, Erratum in Gynecology 2022, 59, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Rana, S.; Karumanchi, S.A. Preeclampsia: The Role of Angiogenic Factors in Its Pathogenesis. Physiology 2009, 24, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, G.; Khankin, E.V.; Karumanchi, S.A. Angiogenic Factors and Preeclampsia. Thromb. Res. 2009, 123 (Suppl. 2), S93–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirashima, C.; Ohkuchi, A.; Matsubara, S.; Suzuki, H.; Takahashi, K.; Arai, F.; Watanabe, T.; Sato, Y.; Minakami, H. Alteration of Serum Soluble Endoglin Levels after the Onset of Preeclampsia Is More Pronounced in Women with Early-Onset. Hypertens. Res. 2008, 31, 1541–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkuchi, A.; Hirashima, C.; Matsubara, S.; Suzuki, H.; Takahashi, K.; Arai, F.; Watanabe, T.; Sato, Y.; Minakami, H. Alterations in Placental Growth Factor Levels before and after the Onset of Preeclampsia Are More Pronounced in Women with Early-Onset Severe Preeclampsia. Hypertens. Res. 2007, 30, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikström, A.K.; Larsson, A.; Eriksson, U.J.; Nash, P.; Norden-Lindeberg, S.; Olovsson, M. Early Postpartum Changes in Circulating Pro- and Anti-Angiogenic Factors in Early-Onset and Late-Onset Preeclampsia. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2008, 87, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvidou, M.; Akolekar, R.; Zaragoza, E.; Poon, L.C.; Nicolaides, K.H. First Trimester Urinary Placental Growth Factor and Development of Preeclampsia. BJOG 2009, 116, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.C.; Crossley, J.A.; Aitken, D.A.; Jenkins, N.; Lyall, F.; Cameron, A.D.; Connor, J.M.; Dobbie, R. Circulating Angiogenic Factors in Early Pregnancy and the Risk of Preeclampsia, Intrauterine Growth Restriction, Spontaneous Preterm Birth, and Stillbirth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 109, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuyama, H.; Suwaki, N.; Nakatsukasa, H.; Masumoto, A.; Tateishi, Y.; Hiramatrsu, Y. Circulating Angiogenic Factors in Preeclampsia, Gestational Proteinuria, and Preeclampsia Superimposed on Chronic Glomerulonephritis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lykke, J.A.; Langhoff-Roos, J.; Sibai, B.M.; Funai, E.F.; Triche, E.W.; Paidas, M.J. Hypertensive Pregnancy Disorders and Subsequent Cardiovascular Morbidity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the Mother. Hypertension 2009, 53, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, R.J.; Qian, C.; Maynard, S.E.; Yu, K.F.; Epstein, F.H.; Karumanchi, S.A. Serum sFlt1 Concentration during Preeclampsia and Midtrimester Blood Pressure in Healthy Nulliparous Women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 194, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumann, M.U.; Bersinger, N.A.; Mohaupt, M.G.; Raio, L.; Gerber, S.; Surbek, D.V. First Trimester Serum Levels of Soluble Endoglin and Soluble Fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase-1 as First-Trimester Markers for Late-Onset Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 199, 266.e1–266.e6. [Google Scholar]

- De Vivo, A.; Baviera, G.; Giordano, D.; Todarello, G.; Corrado, F.; D’Anna, R. Endoglin, PlGF and sFlt-1 as Markers for Predicting Preeclampsia. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2008, 87, 837–842. [Google Scholar]

- Moore Simas, T.A.; Crawford, S.L.; Solitro, M.J.; Frost, S.C.; Meyer, B.A.; Maynard, S.E. Angiogenic Factors for the Prediction of Preeclampsia in High-Risk Women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 197, 244.e1–244.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadar, S.K.; Karalis, I.; Al Yemeni, E.; Blann, A.D.; Lip, G.Y. Plasma Markers of Angiogenesis in Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 94, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsch, F.; Romero, R.; Kusanovic, J.P.; Mazaki-Tovi, S.; Pineles, B.L.; Erez, O.; Espinoza, J.; Kim, C.J.; Hassan, S.S. Preeclampsia and Small-for-Gestational Age Are Associated with Decreased Concentrations of a Factor Involved in Angiogenesis: Soluble Tie-2. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008, 21, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, R.; Rath, G.; Jain, A.; Salhan, S. Soluble and Membranous Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-1 in Pregnancies Complicated by Preeclampsia. Ann. Anat. 2008, 190, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiworapongsa, T.; Romero, R.; Espinoza, J.; Bujold, E.; Mee Kim, Y.; Goncalves, L.F.; Gomez, R.; Edwin, S.; Mazor, M. Evidence Supporting a Role for Blockade of the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor System in the Pathophysiology of Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 190, 1541–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.; Hefler, L.; Tempfer, C.; Zeisler, H.; Lebrecht, A.; Husslein, P.; Singer, C.F. Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Serum Levels in Pregnancy and Preeclampsia. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2002, 81, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaiworapongsa, T.; Romero, R.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, G.J.; Kim, M.R.; Espinoza, J.; Bujold, E.; Goncalves, L.F.; Edwin, S.; Mazor, M. Plasma Soluble Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-1 Concentration Is Elevated Prior to the Clinical Diagnosis of Preeclampsia. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2005, 17, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathen, K.A.; Ylikorkala, O.; Andersson, S.; Alfthan, H.; Stenman, U.H.; Vuorela, P. Maternal Serum Endostatin at Gestational Weeks 16–20 Is Elevated in Subsequent Preeclampsia but Not in Intrauterine Growth Retardation. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2009, 88, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, R.A.; Abdel-Raouf, M. Serum Endostatin and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Levels in Patients with Preeclampsia. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2006, 12, 178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Hirtenlehner, K.; Pollheimer, J.; Lichtenberger, C.; Knöfler, M.; Desoye, G. Elevated Serum Concentrations of the Angiogenesis Inhibitor Endostatin in Preeclamptic Women. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2003, 10, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikström, A.K.; Larsson, A.; Åkerud, H.; Olovsson, M. Increased Circulating Levels of the Antiangiogenic Factor Endostatin in Early-Onset but Not Late-Onset Preeclampsia. Reprod. Sci. 2009, 16, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anteby, E.Y.; Greenfield, C.; Natanson-Yaron, S.; Goldman-Wohl, D.; Hamani, Y.; Prus, D.; Cohen, Y.; Yagel, S. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, Epidermal Growth Factor and Fibroblast Growth Factor-4 and -10 Stimulate Trophoblast Plasminogen Activator System and Metalloproteinase-9. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2004, 10, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, R.E.; Romero, R.; Kim, Y.M.; Chaiworapongsa, T.; Kilburn, B.; Das, S.K.; Dey, S.K.; Johnson, A.; Qureshi, F.; Jacques, S.; et al. Preeclampsia and Expression of Heparin-Binding EGF-Like Growth Factor. Lancet 2002, 360, 1215–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peracoli, M.T.; Menegon, F.T.; Borges, V.T.; de Araújo Costa, R.A.; Thomaz, A.F.; Rodrigues, D.B.; de Campos, M.B.; Rudge, M.V.; Witkin, S.S. Platelet Aggregation and TGF-β1 Plasma Levels in Pregnant Women with Preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2008, 79, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moll, S.J.; Jones, C.J.; Crocker, I.P.; Baker, P.N.; Heazell, A.E.; Cartwright, J.E.; Whitley, G.S. Epidermal Growth Factor Rescues Trophoblast Apoptosis Induced by Reactive Oxygen Species. Apoptosis 2007, 12, 1611–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imudia, A.N.; Kilburn, B.A.; Petkova, A.; Edwin, S.S.; Romero, R.; Armant, D.R. Expression of Heparin-Binding EGF-Like Growth Factor in Term Chorionic Villous Explants and Its Role in Trophoblast Survival. Placenta 2008, 29, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hennessy, A.; Orange, S.; Willis, N.; Painter, D.; Child, A.; Horvath, J.S. Transforming Growth Factor-β1 Does Not Relate to Hypertension in Preeclampsia. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2002, 29, 968–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purwosunu, Y.; Sekizawa, A.; Yoshimura, S.; Nakamura, M.; Shimizu, H.; Okai, T. Expression of Angiogenesis-Related Genes in the Cellular Component of the Blood of Preeclamptic Women. Reprod. Sci. 2009, 16, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanczuk, G.A.; McCoy, M.J.; Hutchinson, I.V.; Wardle, P.G.; Li, T.C. The Genetic Predisposition to Produce High Levels of TGF-β1 Impacts on the Severity of Eclampsia/Preeclampsia. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007, 86, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopcow, H.D.; Karumanchi, S.A. Angiogenic Factors and Natural Killer (NK) Cells in the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2007, 76, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lindheimer, M.D.; Umans, J.G. Explaining and Predicting Preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 1056–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.C.; Sun, Y.; Yang, H.X.; Gao, Y. Profile of Serum Endoglin in Pregnant Women with Severe Preeclampsia and Eclampsia. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2009, 44, 91–93. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Stepan, H.; Jank, A. Circulatory Soluble Endoglin and Its Predictive Value for Preeclampsia in Second-Trimester Pregnancies with Abnormal Uterine Perfusion. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 198, 175.e1–175.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; Jauniaux, E.; Harrington, K. Antihypertensive Therapy and Central Hemodynamics in Women with Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 113, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonen, R.; Shahar, R.; Grimpel, Y.I.; Chefetz, I.; Sammar, M.; Meiri, H.; Lyall, F.; Huppertz, B.; Singer, H.; Vlodavsky, I.; et al. Placental Protein 13 as an Early Marker for Preeclampsia: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. BJOG 2008, 115, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, D.; Tannetta, D.S.; Magee, L.A.; Fuchisawa, A.; Redman, C.W.; Sargent, I.L.; von Dadelszen, P. Excess Syncytiotrophoblast Microparticle Shedding Is a Feature of Early-Onset Preeclampsia, but Not Normotensive Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Placenta 2006, 27, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiessl, B. Inflammatory Response in Preeclampsia. Mol. Asp. Med. 2007, 28, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargent, I.L.; Borzychowski, A.M.; Redman, C.W. NK Cells and Preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2007, 76, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cackovic, M.; Buhimschi, C.S.; Zhao, G.; Dulay, A.T.; Abdel-Razeq, S.S.; Rosenberg, V.A.; Pettker, C.M.; Sfakianaki, A.K.; Buhimschi, I.A. Fractional Excretion of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α in Women with Severe Preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 112, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, H.; Matuoka, K.; Inooku, H.; Hirayama, T.; Nagata, I.; Sekiya, S. TNF-α from Monocytes of Patients with Preeclampsia Induced Apoptosis in Human Trophoblast Cell Line. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2007, 33, 408–416. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, T.H.; Charnock-Jones, D.S.; Skepper, J.N.; Burton, G.J. Secretion of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α from Human Placental Tissues Induced by Hypoxia–Reoxygenation Causes Endothelial Cell Activation In Vitro: A Potential Mediator of the Inflammatory Response in Preeclampsia. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 164, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppi, P.; DeLoia, J.A. Monocytes of Preeclamptic Women Spontaneously Synthesize Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines. Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odegård, R.A.; Vatten, L.J.; Nilsen, S.T.; Salvesen, K.A.; Austgulen, R. Umbilical Cord Plasma Interleukin-6 and Fetal Growth Restriction in Preeclampsia: A Prospective Study in Norway. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 98, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iademarco, M.F.; McQuillan, J.J.; Rosen, G.D.; Dean, D.C. Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1: Contrasting Transcriptional Control Mechanisms in Muscle and Endothelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 9228–9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, T.; Azab, H.; Dietrich, M.; Augustin, H.G. Fetal Plasma Levels of Circulating Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecules in Normal and Preeclamptic Pregnancies. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1998, 78, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donker, R.B.; Molema, G.; Faas, M.M.; van Pampus, M.G.; Timmer, A.; van der Schors, R.C.; Heineman, M.J.; van der Heide, D.; Buurma, A.; Scherjon, S.A. Absence of In Vitro Generalized Pro-Inflammatory Endothelial Activation in Severe, Early-Onset Preeclampsia. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2005, 12, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, R. The Relationship between the Level of Expression of Intracellular Adhesion Molecule-1 in Placenta and Onset of Preeclampsia. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2001, 27, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poston, L.; Raijmakers, M.T. Trophoblast Oxidative Stress, Antioxidants and Pregnancy Outcome—A Review. Placenta 2004, 25 (Suppl. A), S72–S78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Jauniaux, E. Placental Oxidative Stress: From Miscarriage to Preeclampsia. J. Soc. Gynecol. Investig. 2004, 11, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubel, C.A. Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Preeclampsia. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1999, 222, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijmakers, M.T.; Peters, W.H.; Steegers, E.A.; Poston, L. NAD(P)H Oxidase Associated Superoxide Production in Human Placenta from Normotensive and Pre-Eclamptic Women. Placenta 2004, 25 (Suppl. A), S85–S89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Agarwal, A.; Sharma, R.K. The Role of Placental Oxidative Stress and Lipid Peroxidation in Preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2005, 60, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admati, I.; Skarbianskis, N.; Hochgerner, H.; Schwartz, R.; Shapira, T.; Maza, E.; Amit, I. Two Distinct Molecular Faces of Preeclampsia Revealed by Single-Cell Transcriptomic Survey. Cell Med. 2023, 4, 687–709.e7. [Google Scholar]

- Moffett, A.; Hiby, S.E. How Does the Maternal Immune System Contribute to the Development of Preeclampsia. Placenta 2007, 28 (Suppl. A), S51–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibai, B.; Dekker, G.; Kupferminc, M. Preeclampsia. Lancet 2005, 365, 785–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazouni, C.; Capo, C.; Ledu, R.; Porcu, G.; Guerrier, D.; Blanc, B. Preeclampsia: Impaired Inflammatory Response Mediated by Toll-like Receptors. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2008, 78, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molvarec, A.; Jermendy, Á.; Kovács, M.; Prohászka, Z.; Rosta, K.; Demendi, C.; Nagy, B.; Rigó, J., Jr. Toll-like Receptor 4 Gene Polymorphisms and Preeclampsia: Lack of Association in a Caucasian Population. Hypertens. Res. 2008, 31, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rijn, B.B.; Franx, A.; Steegers, E.A.; de Groot, C.J.; Bertina, R.M.; Pasterkamp, G.; Voorbij, H.A.; Bruinse, H.W. Maternal TLR4 and NOD2 Gene Variants, Pro-Inflammatory Phenotype and Susceptibility to Early-Onset Preeclampsia and HELLP Syndrome. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, F.; Drevon, C.A. Activation of Nuclear Factor-κB by High Molecular Weight and Globular Adiponectin. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 5478–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.M. Activation of NF-κB and Expression of COX-2 in Association with Neutrophil Infiltration in Systemic Vascular Tissue of Women with Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 196, 48.e1–48.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aban, M.; Cinel, L.; Arslan, M.; Dilek, U.; Kaplanoglu, M.; Arpaci, R.; Tamer, L. Expression of Nuclear Factor κB and Placental Apoptosis in Pregnancies Complicated with Intrauterine Growth Restriction and Preeclampsia: An Immunohistochemical Study. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2004, 204, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovere-Querini, P.; Antonacci, S.; Dell’Antonio, G.; Angeli, A.; Almirante, G.; Cin, E.D.; Caruso, A.; Garlanda, C.; Mantovani, A. Plasma and Tissue Expression of the Long Pentraxin 3 during Normal Pregnancy and Preeclampsia. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 108, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akolekar, R.; Casagrandi, D.; Livanos, P.; Tenenbaum-Gavish, K.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Nicolaides, K.H. Maternal Plasma Pentraxin 3 at 11 to 13 Weeks of Gestation in Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Prenat. Diagn. 2009, 29, 934–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, I.; Cozzi, V.; Papageorghiou, A.T.; Radaelli, T.; Ferrazzi, E.; Motta, S.; Marconi, A.M.; Giovannini, N.; Acaia, B.; Pardi, G. First Trimester PTX3 Levels in Women Who Subsequently Develop Preeclampsia and Fetal Growth Restriction. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2009, 88, 846–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjaerven, R.; Wilcox, A.J.; Lie, R.T. The Interval between Pregnancies and the Risk of Preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, S.; Sakai, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Nakashima, A.; Shiozaki, A. Inadequate Tolerance Induction May Induce Preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2007, 76, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robillard, P.Y.; Hulsey, T.C.; Périanin, J.; Janky, E.; Miri, E.H.; Papiernik, E. Association of Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension with Duration of Sexual Cohabitation before Conception. Lancet 1994, 344, 973–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubbergen, P.; Lachmeijer, A.M.; Althuisius, S.M.; Vlak, M.E.; van Geijn, H.P.; Dekker, G.A. Change in Paternity: A Risk Factor for Preeclampsia in Multiparous Women? J. Reprod. Immunol. 1999, 45, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, P.Y.; Dekker, G.A.; Hulsey, T.C. Revisiting the Epidemiological Standard of Preeclampsia: Primigravidity or Primipaternity? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1999, 84, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robillard, P.Y.; Dekker, G.; Chaouat, G.; Scioscia, M.; Iacobelli, S.; Hulsey, T.C. Historical Evolution of Ideas on Eclampsia/Preeclampsia: A Proposed Optimistic View of Preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2017, 123, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, P.Y.; Dekker, G.; Chaouat, G.; Scioscia, M.; Boukerrou, M. Primipaternities and Human Birthweights. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 147, 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman-Wohl, D.; Gamliel, M.; Mandelboim, O.; Yagel, S. Learning from Experience: Cellular and Molecular Bases for Improved Outcome in Subsequent Pregnancies. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, P.Y.; Dekker, G.; Chaouat, G.; Elliot, M.G.; Scioscia, M. High Incidence of Early Onset Preeclampsia Is Probably the Rule and Not the Exception Worldwide. 20th Anniversary of the Reunion Workshop. A Summary. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2019, 133, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robillard, P.Y.; Dekker, G.A.; Hulsey, T.C. Evolutionary Adaptations to Preeclampsia/Eclampsia in Humans: Low Fecundability Rate, Loss of Oestrus, Prohibitions of Incest and Systematic Polyandry. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2002, 47, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veit, J. Über Albuminurie in der Schwangerschaft. Ein Beitrag zur Physiologie der Schwangerschaft. Berl. Klin. Wochenschr. 1902, 3, 513–516. [Google Scholar]

- McQuarrie, I. Isoagglutination in the Newborn Infants and Their Mother: A Possible Relationship between Interagglutination and the Toxemias of Pregnancy. Johns Hopkins Hosp. Bull. 1923, 34, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Medawar, P.B. Some Immunological and Endocrinological Problems Raised by the Evolution of Viviparity in Vertebrates. In Evolution; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1953; Volume 7, pp. 320–338. [Google Scholar]

- Pouta, A.; Hartikainen, A.L.; Sovio, U.; Gissler, M.; Laitinen, J.; Steinhausen, H.C.; Jarvelin, M.R. Manifestations of Metabolic Syndrome after Hypertensive Pregnancy. Hypertension 2004, 43, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grieger, J.A.; Bianco-Miotto, T.; Grzeskowiak, L.E.; Leemaqz, S.Y.; Poston, L.; McCowan, L.M.; Kenny, L.C.; Myers, J.; Walker, J.J.; Dekker, G.A.; et al. Metabolic Syndrome in Pregnancy and Risk for Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Prospective Cohort of Nulliparous Women. PLoS Med. 2018, 15, e1002710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redman, C.W.; Sacks, G.P.; Sargent, I.L. Preeclampsia: An Excessive Maternal Inflammatory Response to Pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 180 Pt 1, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioscia, M.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Goldman-Wohl, D.; Robillard, P.Y. Endothelial Dysfunction and Metabolic Syndrome in Preeclampsia: An Alternative Viewpoint. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2015, 108, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, M.A.; Scioscia, M.; Gumaa, K.A.; Rodeck, C.H.; Rademacher, T.W. P-Type Inositol Phosphoglycans in Serum and Amniotic Fluid in Active Preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2006, 69, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, G.J.; Scioscia, M.; Rademacher, T.W. Endometrial Secretions: Creating a Stimulatory Microenvironment within the Human Early Placenta and Implications for the Aetiopathogenesis of Preeclampsia. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011, 89, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioscia, M.; Noventa, M.; Cavallin, F.; de Carolis, S.; Tiralongo, G.M.; Scutiero, G.; Tersigni, C.; Giannubilo, S.R.; Garofalo, S.; Giannella, L.; et al. Exploring Strengths and Limits of Urinary D-Chiro Inositol Phosphoglycans (IPG-P) as a Screening Test for Preeclampsia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2019, 134–135, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioscia, M.; Dekker, G.A.; Chaouat, G.; Garofalo, S.; Giannubilo, S.R.; Tiralongo, G.M.; Noventa, M.; Scutiero, G.; Giannella, L.; Tersigni, C.; et al. A Top Priority in Preeclampsia Research: Development of a Reliable and Inexpensive Urinary Screening Test. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e1312–e1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisler, H.; Llurba, E.; Chantraine, F.; Vatish, M.; Staff, A.C.; Sennström, M.; Olovsson, M.; Brennecke, S.P.; Stepan, H.; Allegranza, D.; et al. Predictive Value of the sFlt-1:PlGF Ratio in Women with Suspected Preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, X.; Biswas, A.; Huang, X.; Lee, K.J.; Li, T.K.; Goh, E.S.; Lin, S.L.; Tan, K.H.; Tan, E.L.; Biswas, J.; et al. Short-Term Prediction of Adverse Outcomes Using the sFlt-1 (Soluble fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase 1)/PlGF (Placental Growth Factor) Ratio in Asian Women with Suspected Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2019, 74, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagel, S.; Cohen, S.M.; Admati, I.; Amit, I.; Gamliel, M.; Goldman-Wohl, D. Expert Review: Preeclampsia Type I and Type II. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 101203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, G.A.; Robillard, P.Y. Preeclampsia—An Immune Disease? An Epidemiologic Narrative. Explor. Immunol. 2021, 1, 325–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamliel, M.; Goldman-Wohl, D.; Isaacson, B.; Gur, C.; Stein, N.; Yamin, R.; Berger, M.; Grunewald, M.; Keshet, E.; Rais, Y.; et al. Trained Memory of Human Uterine NK Cells Enhances Their Function in Subsequent Pregnancies. Immunity 2018, 48, 951–962.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, D.L.; Wright, D.; Poon, L.C.; O’Gorman, N.; Syngelaki, A.; de Paco Matallana, C.; Akolekar, R.; Cicero, S.; Janga, D.; Singh, M.; et al. Aspirin versus Placebo in Pregnancies at High Risk for Preterm Preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, K.H.; Sarno, M.; Wright, A. Ophthalmic Artery Doppler in the Prediction of Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S1098–S1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicocca, M.J.; Mendez-Figueroa, H.; Chauhan, S.P.; Sibai, B.M. Maternal Obesity and the Risk of Early-Onset and Late-Onset Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 136, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, P.Y.; Dekker, G.; Scioscia, M.; Bonsante, F.; Iacobelli, S.; Boukerrou, M.; Boumahni, B.; Hulsey, T.; Scioscia, M. Increased BMI Has a Linear Association with Late Onset Preeclampsia: A Population-Based Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, P.Y.; Dekker, G.; Boukerrou, M.; Boumahni, B.; Hulsey, T.; Scioscia, M. Gestational Weight Gain and Rate of Late-Onset Preeclampsia: A Retrospective Analysis on 57,000 Singleton Pregnancies in Reunion Island. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e036549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, P.Y. Risk Factors for Early and Late Onset Preeclampsia in Women without Pathological History: Confirmation of the Paramount Effect of Excessive Maternal Pre-Pregnancy Corpulence on Risk for Late Onset Preeclampsia. Integr. Gyn. Obstet. J. 2020, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Yagel, S.; Verlohren, S. Role of Placenta in Development of Preeclampsia: Revisited. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 56, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagel, S. The Developmental Role of Natural Killer Cells at the Fetal–Maternal Interface. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 201, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, J.F., 3rd; Capeless, E. Cardiovascular Function before, during, and after the First and Subsequent Pregnancies. Am. J. Cardiol. 1997, 80, 1469–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.Z.; Guy, G.P.; Bisquera, A.; Poon, L.C.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Kametas, N.A. The Effect of Parity on Longitudinal Maternal Hemodynamics. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 249.e1–249.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Romero, R.; Yeo, L.; Diaz-Primera, R.; Marin-Concha, J.; Para, R.; Lopez, A.M.; Panaitescu, B.; Pacora, P.; Erez, O.; et al. The Etiology of Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, S844–S866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiby, S.E.; Walker, J.J.; O’Shaughnessy, K.M.; Redman, C.W.; Carrington, M.; Trowsdale, J.; Moffett, A. Combinations of Maternal KIR and Fetal HLA-C Genes Influence the Risk of Preeclampsia and Reproductive Success. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 200, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andraweera, P.; Roberts, C.T.; Leemaqz, S.; McCowan, L.; Myers, J.; Kenny, L.C.; Walker, J.; Poston, L.; Dekker, G. SCOPE Consortium. The Duration of Sexual Relationship and Its Effects on Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018, 128, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.; de Nieuwburgh, M.P.; Hubinont, C.; Palmer, F.; Zamudio, S.; Coffin, C.; Parker, S.; Stamm, E.; Moore, L.G. Quantitative Estimation of Human Uterine Artery Blood Flow and Pelvic Blood Flow Redistribution in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 80, 1000–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumar, A.; Cerdeira, A.S.; Rana, S.; Zsengeller, Z.; Edmunds, L.; Jeyabalan, A.; Hubel, C.A.; Stillman, I.E.; Parikh, S.M.; Karumanchi, S.A. Transcriptionally Active Syncytial Aggregates in the Maternal Circulation May Contribute to Circulating Soluble fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase 1 in Preeclampsia. Hypertension 2012, 59, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, H.; Hamano, Y.; Charytan, D.; Cosgrove, D.; Kieran, M.; Sudhakar, A.; Kalluri, R. Neutralization of Circulating Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) by Anti-VEGF Antibodies and Soluble VEGF Receptor 1 (sFlt-1) Induces Proteinuria. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 12605–12608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salomon, C.; Guanzon, D.; Scholz-Romero, K.; Longo, S.; Correa, P.; Illanes, S.E.; Rice, G.E. Placental Exosomes as Early Biomarker of Preeclampsia: Potential Role of Exosomal MicroRNAs across Gestation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 3182–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skow, R.J.; King, E.C.; Steinback, C.D.; Davenport, M.H. The Influence of Prenatal Exercise and Preeclampsia on Maternal Vascular Function. Clin. Sci. 2017, 131, 2223–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Peers de Nieuwburgh, M.; Hubinont, C.; Debiève, F.; Colson, A. Gene Therapy in Preeclampsia: The Dawn of a New Era. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2024, 43, 2358761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Guideline/Source | Definition of Preeclampsia | Proteinuria/Other Criteria | Additional Features/End-Organ Dysfunction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional (WHO/Classic) | New-onset hypertension after 20 weeks (≥140/90 mm Hg) | Proteinuria ≥ 300 mg/24 h or ≥2 + dipstick | – |

| ACOG (2019) | New-onset hypertension after 20 weeks (≥140/90 mm Hg on 2 occasions, ≥4 h apart) | Proteinuria ≥ 300 mg/24 h or PCR ≥ 30 mg/mmol | In absence of proteinuria: renal insufficiency (SCr > 97 µmol/L), hepatic involvement (AST/ALT > 2 × ULN), thrombocytopenia (<100,000/µL), pulmonary edema, neurological symptoms |

| ISSHP-M (2021) | New-onset hypertension (≥140/90 mm Hg on ≥2 occasions) | Proteinuria ≥ 300 mg/24 h or PCR ≥ 30 mg/mmol | At least 1: renal insufficiency (SCr ≥ 90 µmol/L), hepatic involvement (AST/ALT > 40 IU/L), thrombocytopenia (<150,000/µL), neurological symptoms (visual disturbance, clonus, etc.) |

| ISSHP-MF (2021) | As above + evidence of uteroplacental dysfunction | – | Fetal growth restriction (EFW < 10th centile with abnormal Dopplers) or fetal death |

| ISSHP-MF-AI (2021) | As above + biochemical evidence of angiogenic imbalance | – | sFlt-1/PlGF ratio > 95th percentile or PlGF < 5th percentile |

| Parameter/Marker Ref | Typical Findings in EOPE | Typical Findings in LOPE | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uterine artery Doppler (PI, notching) [15,16,25] | PI > 95th percentile; bilateral early diastolic notches frequent | Usually normal or mildly elevated PI; notching uncommon | Reflects impaired spiral artery remodeling and uteroplacental hypoperfusion; predictive of EOPE |

| Umbilical artery Doppler (PI, EDF pattern) [15,18,25] | Elevated PI; possible absent/reversed end-diastolic flow (AEDF/REDF) in severe cases | Normal or mildly elevated PI; normal EDF | Indicates increased placental vascular resistance and fetal growth restriction |

| Middle cerebral artery (MCA) PI [15,25,39] | Decreased (<5th percentile) due to brain-sparing response | Often within normal range | Reflects fetal adaptation to hypoxia; part of cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) assessment |

| Cerebroplacental ratio (CPR = MCA-PI/UA-PI) [25,39,126] | <5th percentile (abnormal) | Typically normal | Sensitive marker of fetal compromise and adverse perinatal outcome |

| Placental morphology (B-mode) [13,14,15] | May show thickened or lobulated placenta, but nonspecific | Usually normal appearance | Morphologic changes alone are not diagnostic; Doppler assessment is essential |

| Ophthalmic artery Doppler (maternal) [38,39,40,132] | Possible increased resistance index, indicating impaired maternal vascular adaptation | Near-normal hemodynamic profile | Experimental marker for maternal endothelial function; not yet in clinical use |

| Integration with angiogenic biomarkers (sFlt-1/PlGF) [39,126] | Markedly increased ratio; abnormal values correlate with EOPE and adverse outcomes | Mild or moderate increase | Enhances short-term prediction and risk stratification, especially near term |

| Early Onset Preeclampsia (<34 Week) | Late Onset Preeclampsia (≥34 Week) | |

|---|---|---|

| Screening | Maternal factors, mean arterial pressure, uterine artery Doppler, and PlGF | -------- |

| Risk factors | Nulliparity Previous preeclampsia Diabetes IVF without corpus luteum IVF with donor eggs Antiphospholipid syndrome Molar pregnancy Fetal conditions | Nulliparity Previous preeclampsia Diabetes IVF without corpus luteum IVF with donor eggs Obesity Chronic hypertension Chronic kidney disease |

| Common clinical and laboratory characteristics | Fetal growth restriction sFlt-1/PlGF ↑↑↑ Cardiac output ↓ Peripheral vascular resistance ↑ | Macrosomia/twins and multiples sFlt-1/PlGF ↑ Cardiac output ↑ Peripheral vascular resistance ↓ |

| Pregnancy surveillance | Clinical parameters Laboratory studies (includingsFlt-1/PlGF) Doppler studies Estimated fetal weight Maternal cardiac studies | Clinical parameters Laboratory studies (includingsFlt-1/PlGF) Estimated fetal weight |

| Preventative strategies | Exercise duration » 140 min/week Aspirin Aspirin + LMWH (in presence of antiphospholipid antibody) Calcium administration Progesterone support in IVF pregnancy? | Exercise duration ≥ 140 min/week Glycemic control Weight control and reduction Prevention of multiple pregnancy |

| Defined strategies | Exercise NO donors, calcium channel blockers, fluid support aimed at vasodilation Timed delivery | Exercise Alpha/beta blockers Timed delivery |

| Future strategies | sFlt-1ligands siRNA-based therapy Plasmapheresis Antioxidants | ------------ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kariori, M.; Katsi, V.; Tsioufis, C. Late vs. Early Preeclampsia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211091

Kariori M, Katsi V, Tsioufis C. Late vs. Early Preeclampsia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211091

Chicago/Turabian StyleKariori, Maria, Vasiliki Katsi, and Costas Tsioufis. 2025. "Late vs. Early Preeclampsia" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211091

APA StyleKariori, M., Katsi, V., & Tsioufis, C. (2025). Late vs. Early Preeclampsia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11091. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211091