Diverse Impact of E-Cigarette Aerosols on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Lung Alveolar Epithelial Cells (A549)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Panel 1: Cell Morphology, Growth, Cytotoxicity, and DNA Damage

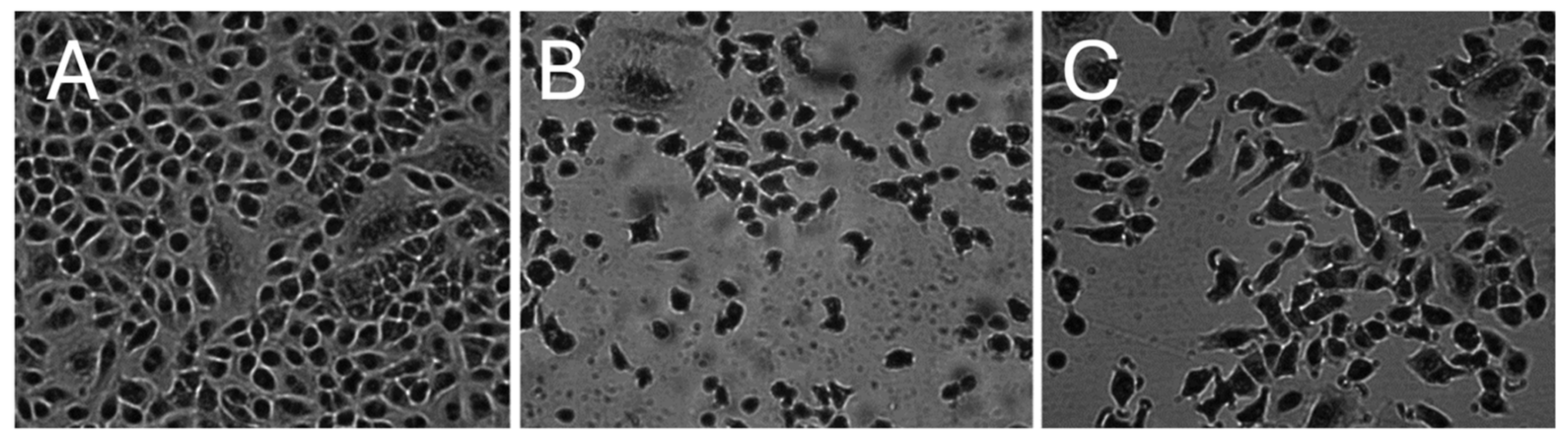

2.1.1. Morphology of A549 Cells

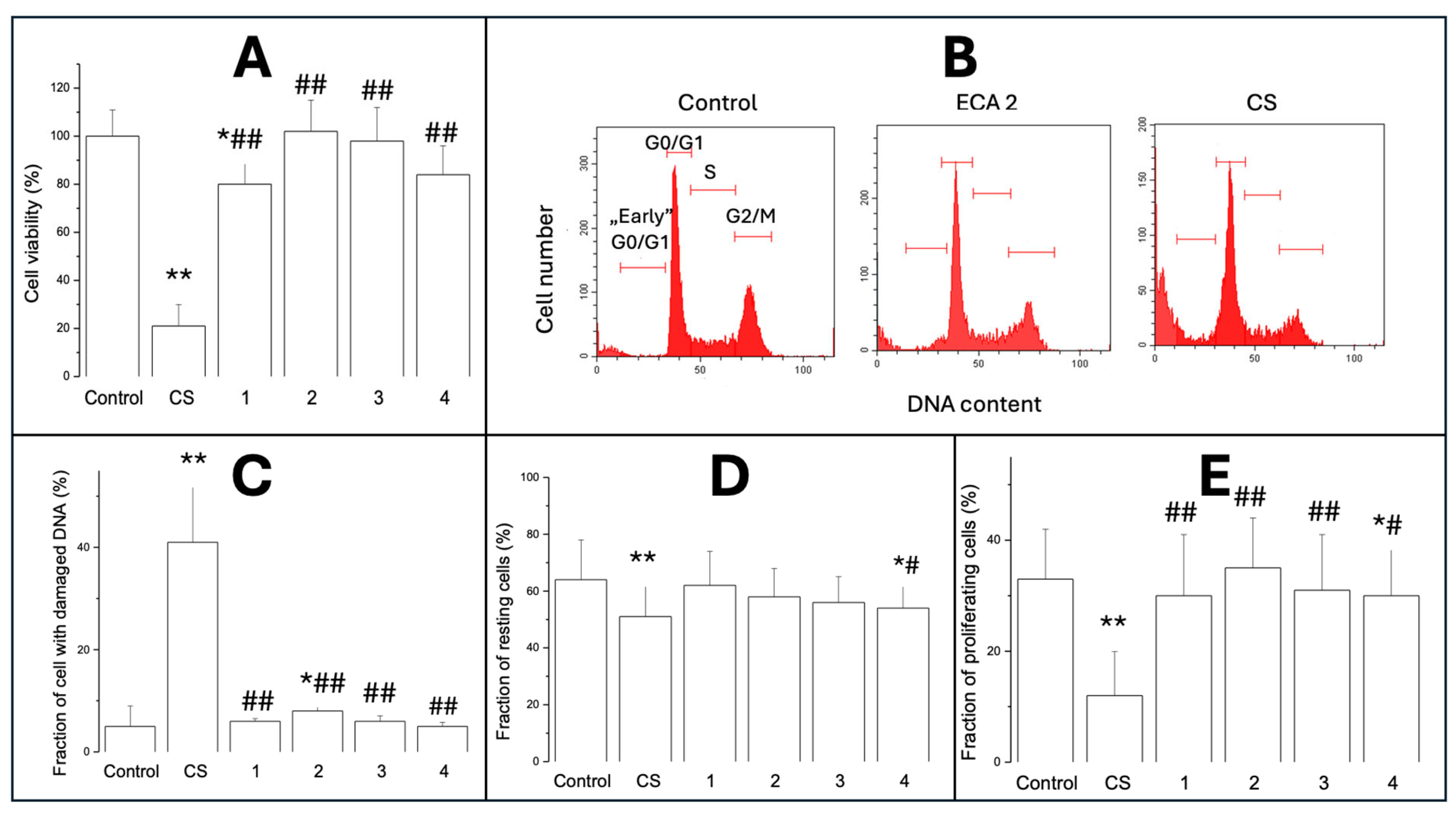

2.1.2. Cell Viability (MTT Test)

2.1.3. Cytotoxicity/Analysis of Cell Cycle

2.1.4. Cell Proliferation

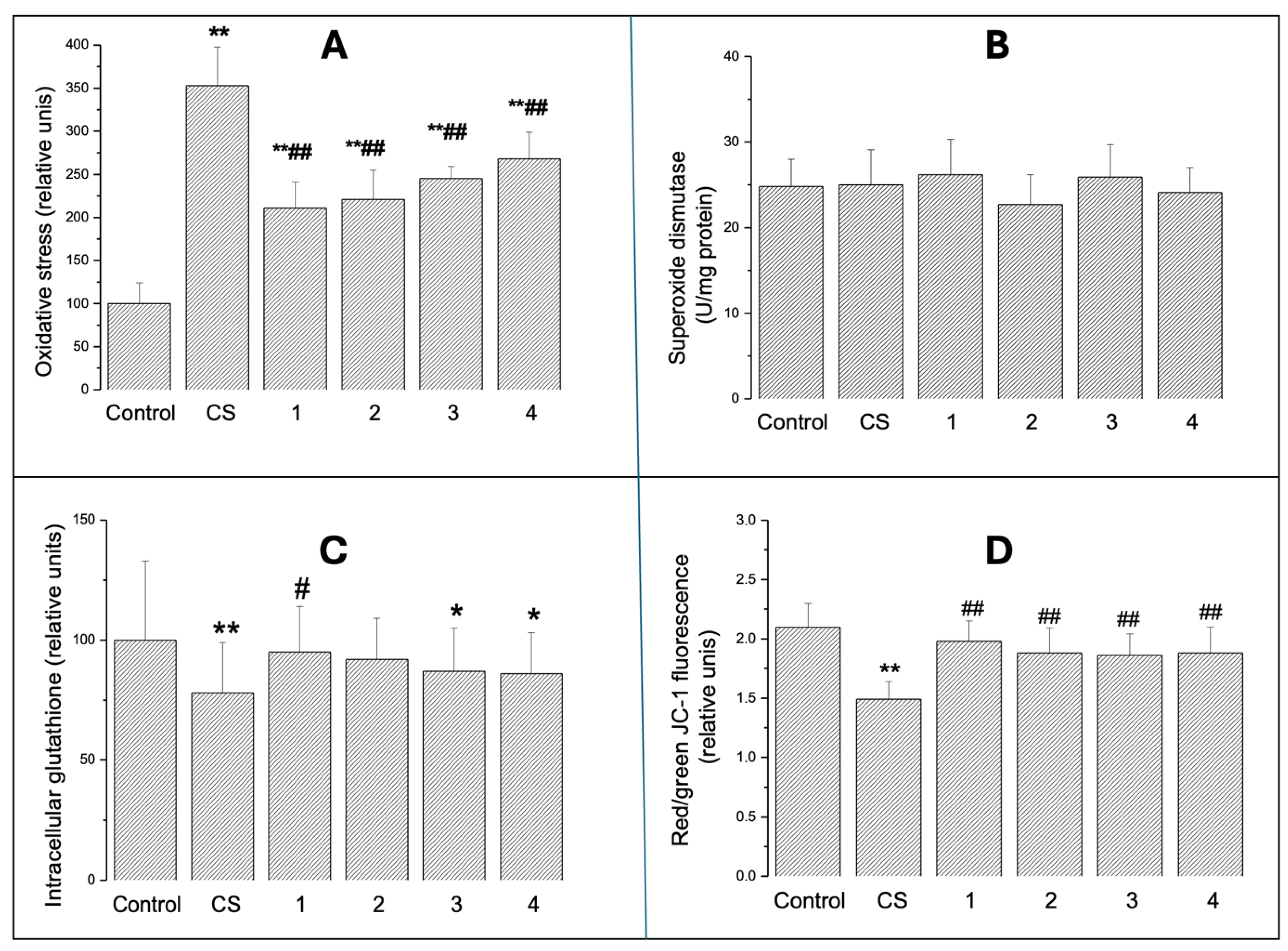

2.2. Panel 2: Oxidative Stress

2.2.1. Intracellular Oxidative Stress

2.2.2. SOD Activity

2.2.3. Intracellular GSH

2.2.4. Mitochondrial Transmembrane Potential

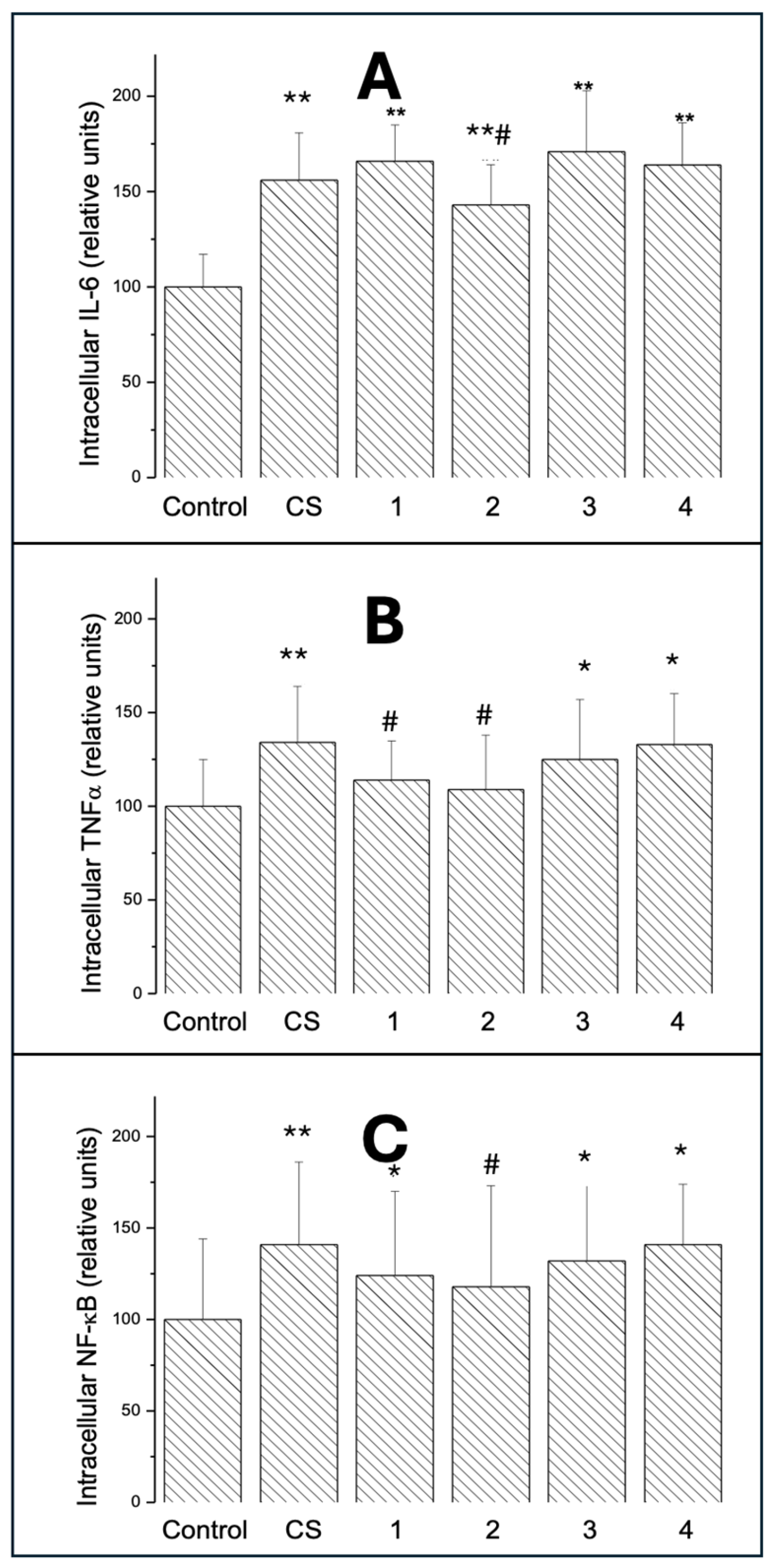

2.3. Panel 3: Inflammation

2.3.1. Intracellular IL-6

2.3.2. Intracellular TNF-α

2.3.3. Intracellular NF-κB

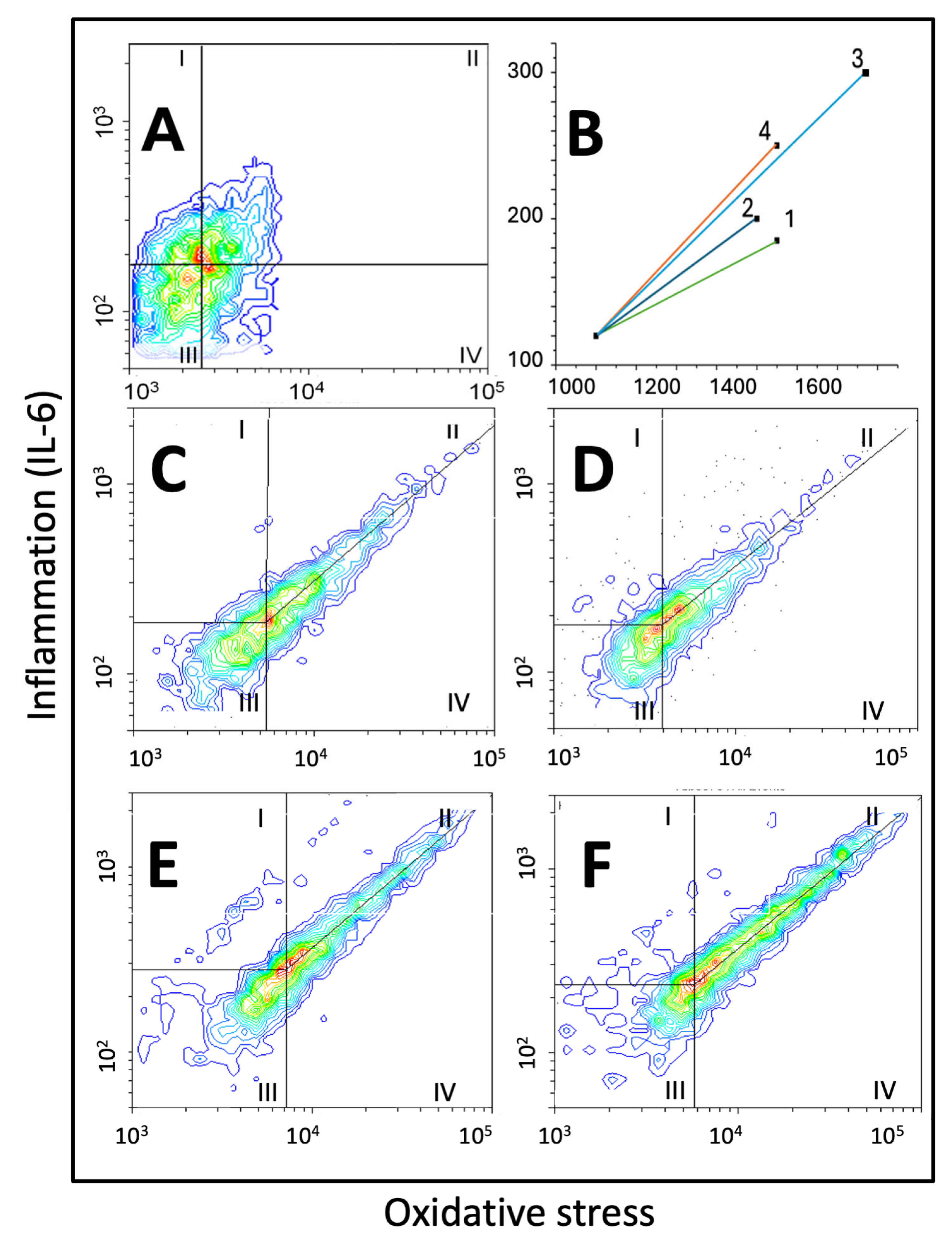

2.4. Panel 4: Double Fluorescence Scatterplots

2.4.1. Scatter Area

2.4.2. Vector Size

2.4.3. Slopes of the Central Tendency Line

2.4.4. Cell Distribution

3. Discussion

Study Limitations and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. Preparation of ECAs and CS-Conditioned Media

4.4. Cell Exposure

4.5. Microscopy and Cell Morphology

4.6. Cell Viability Test

4.7. Flow Cytometry—Cell Cycle Analysis

4.8. Assessment of Oxidative Stress

4.9. Glutathione Level

4.10. Superoxide Dismutase Activity

4.11. Mitochondrial Transmembrane Potential

4.12. Intracellular IL-6, TNF-α, and NF-κB

4.13. Binary Fluorescence Scatterplots of IL-6 vs. Oxidative Stress

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Cullen, K.A.; Gentzke, A.S.; Sawdey, M.D.; Chang, J.T.; Anic, G.M.; Wang, T.W.; Creamer, M.R.; Jamal, A.; Ambrose, B.K.; King, B.A. E-Cigarette Use Among Youth in the United States, 2019. JAMA 2019, 322, 2095–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindson, N.; Butler, A.R.; McRobbie, H.; Bullen, C.; Hajek, P.; Begh, R.; Theodoulou, A.; Notley, C.; Rigotti, N.A.; Turner, T.; et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 1, CD010216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goniewicz, M.L.; Gawron, M.; Smith, D.M.; Peng, M.; Jacob P3rd Benowitz, N.L. Exposure to Nicotine and Selected Toxicants in Cigarette Smokers Who Switched to Electronic Cigarettes: A Longitudinal Within-Subjects Observational Study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2017, 19, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Villarreal, A.; Bozhilov, K.; Lin, S.; Talbot, P. Metal and silicate particles including nanoparticles are present in electronic cigarette cartomizer fluid and aerosol. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sleiman, M.; Logue, J.M.; Montesinos, V.N.; Russell, M.L.; Litter, M.I.; Gundel, L.A.; Destaillats, H. Emissions from Electronic Cigarettes: Key Parameters Affecting the Release of Harmful Chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 9644–9651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talih, S.; Balhas, Z.; Eissenberg, T.; Salman, R.; Karaoghlanian, N.; El Hellani, A.; Baalbaki, R.; Saliba, N.; Shihadeh, A. Effects of user puff topography, device voltage, and liquid nicotine concentration on electronic cigarette nicotine yield: Measurements and model predictions. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2015, 17, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieber, M.; Smith, B.; Szakal, A.; Nelson-Rees, W.; Todaro, G. A continuous tumor-cell line from a human lung carcinoma with properties of type II alveolar epithelial cells. Int. J. Cancer 1976, 17, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, C.; Chahine, J.B.; Haykal, T.; Al Hageh, C.; Rizk, S.; Khnayzer, R.S. E-cigarette aerosol induced cytotoxicity, DNA damages and late apoptosis in dynamically exposed A549 cells. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakoo, M.; Langelier, C.; Calfee, C.S.; Gotts, J.E.; Matthay, M.A. Impact of e-cigarette aerosol on primary human alveolar epithelial type 2 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2022, 1, 152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Jabba, S.V.; Diaz, A.N.; Erythropel, H.C.; Zimmerman, J.B.; Jordt, S.E. Chemical Adducts of Reactive Flavor Aldehydes Formed Rein E-Cigarette Liquids Are Cytotoxic and Inhibit Mitochondrial Function in Respiratory Epithelial Cells. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2020, 22 (Suppl. S1), S25–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, C.; Pourchez, J.; Leclerc, L.; Forest, V. In vitro toxicological evaluation of aerosols generated by a 4th generation vaping device using nicotine salts in an air-liquid interface system. Respir Res. 2024, 25, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, V.; Rahimy, M.; Korrapati, A.; Xuan, Y.; Zou, A.E.; Krishnan, A.R.; Tsui, T.; Aguilera, J.A.; Advani, S.; Crotty Alexander, L.E.; et al. Electronic cigarettes induce DNA strand breaks and cell death independently of nicotine in cell lines. Oral Oncol. 2016, 52, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effah, F.; Elzein, A.; Taiwo, B.; Baines, D.; Bailey, A.; Marczylo, T. In Vitro high-throughput toxicological assessment of E-cigarette flavors on human bronchial epithelial cells and the potential involvement of TRPA1 in cinnamon flavor-induced toxicity. Toxicology 2023, 496, 153617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganapathy, V.; Manyanga, J.; Brame, L.; McGuire, D.; Sadhasivam, B.; Floyd, E.; Rubenstein, D.A.; Ramachandran, I.; Wagener, T.; Queimado, L. Electronic cigarette aerosols suppress cellular antioxidant defenses and induce significant oxidative DNA damage. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeschen, C.; Jang, J.J.; Weis, M.; Pathak, A.; Kaji, S.; Hu, R.S.; Tsao, P.S.; Johnson, F.L.; Cooke, J.P. Nicotine stimulates angiogenesis and promotes tumor growth and atherosclerosis. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay-Greene, F.; Donnellan, S.; Vass, S. Analysing the acute toxicity of e-cigarette liquids and their vapour on human lung epithelial (A549) cells in vitro. Toxicol. Rep. 2025, 15, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behar, R.Z.; Davis, B.; Wang, Y.; Bahl, V.; Lin, S.; Talbot, P. Identification of toxicants in cinnamon-flavored electronic cigarette refill fluids. Toxicol. In Vitro 2014, 28, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omaiye, E.E.; Luo, W.; McWhirter, K.J.; Pankow, J.F.; Talbot, P. Disposable Puff Bar Electronic Cigarettes: Chemical Composition and Toxicity of E-liquids and a Synthetic Coolant. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1344–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, M.; Distefano, A.; Emma, R.; Zuccarello, P.; Copat, C.; Ferrante, M.; Carota, G.; Pulvirenti, R.; Polosa, R.; Missale, G.A.; et al. In vitro cytoxicity profile of e-cigarette liquid samples on primary human bronchial epithelial cells. Drug Test. Anal. 2023, 15, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.S.; Wu, X.R.; Lee, H.W.; Xia, Y.; Deng, F.M.; Moreira, A.L.; Chen, L.C.; Huang, W.C.; Lepor, H. Electronic-cigarette smoke induces lung adenocarcinoma and bladder urothelial hyperplasia in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 21727–21731, Correction in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 22884. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1918000116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, L.; Foley, G. E-cigarettes and respiratory health: The latest evidence. J. Physiol. 2020, 598, 5027–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, K.A.; Oster, C.G.; Mayer, M.M.; Avery, M.L.; Audus, K.L. Characterization of the A549 cell line as a type II pulmonary epithelial cell model for drug metabolism. Exp. Cell Res. 1998, 243, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, V.; Jaganathan, R.; Chinnaiyan, M.; Chengizkhan, G.; Sadhasivam, B.; Manyanga, J.; Ramachandran, I.; Queimado, L. E-Cigarette effects on oral health: A molecular perspective. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 196, 115216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.R.; Jang, J.; Park, S.M.; Ryu, S.M.; Cho, S.J.; Yang, S.R. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Respiratory Response: Insights into Cellular Processes and Biomarkers. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthumalage, T.; Lamb, T.; Friedman, M.R.; Rahman, I. E-cigarette flavored pods induce inflammation, epithelial barrier dysfunction, and DNA damage in lung epithelial cells and monocytes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wen, C. The risk profile of electronic nicotine delivery systems, compared to traditional cigarettes, on oral disease: A review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1146949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petruzzelli, S.; De Flora, S.; Bagnasco, M.; Hietanen, E.; Camus, A.M.; Saracci, R.; Izzotti, A.; Bartsch, H.; Giuntini, C. Carcinogen metabolism studies in human bronchial and lung parenchymal tissues. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1989, 140, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, G.D.; Wingfors, H.; Uski, O.; Hedman, L.; Ekstrand-Hammarström, B.; Bosson, J.; Lundbäck, M. The toxic potential of a fourth-generation E-cigarette on human lung cell lines and tissue explants. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, R.; Smith, G.; Rothwell, E.; Martin, S.; Medhane, R.; Casentieri, D.; Daunt, A.; Freiberg, G.; Hollings, M. A multi-organ, lung-derived inflammatory response following in vitro airway exposure to cigarette smoke and next-generation nicotine delivery products. Toxicol. Lett. 2023, 387, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Potlapalli, R.; Quan, H.; Chen, L.; Xie, Y.; Pouriyeh, S.; Sakib, N.; Liu, L.; Xie, Y. Exploring DNA Damage and Repair Mechanisms: A Review with Computational Insights. BioTech 2024, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milara, J.; Cortijo, J. Tobacco, inflammation, and respiratory tract cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2012, 18, 3901–3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoal, C.; Granjo, P.; Mexia, P.; Gallego, D.; Adubeiro Lourenço, R.; Sharma, S.; Pérez, B.; Castro-Caldas, M.; Grosso, A.R.; Dos Reis Ferreira, V.; et al. Unraveling the biological potential of skin fibroblast: Responses to TNF-α, highlighting intracellular signaling pathways and secretome. Immunol. Lett. 2025, 276, 107057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.A.; Jones, S.A. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat. Immunol. 2015, 16, 448–457, Correction in Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 1271. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni1117-1271b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idriss, H.T.; Naismith, J.H. TNF alpha and the TNF receptor superfamily: Structure-function relationship(s). Microsc. Res. Tech. 2000, 50, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, S.; Vargas, J.; Hoffmann, A. Signaling via the NFκB system. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2016, 8, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovac, S.; Domijan, A.M.; Walker, M.C.; Abramov, A.Y. Seizure activity results in calcium- and mitochondria-independent ROS production via NADPH and xanthine oxidase activation. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan Dunn, J.; Alvarez, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Soldati, T. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondria: A nexus of cellular homeostasis. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivandzade, F.; Bhalerao, A.; Cucullo, L. Analysis of the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Using the Cationic JC-1 Dye as a Sensitive Fluorescent Probe. Bio Protoc. 2019, 9, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čapek, J.; Roušar, T. Detection of Oxidative Stress Induced by Nanomaterials in Cells-The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species and Glutathione. Molecules 2021, 26, 4710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, M.C.; Tanyeli, A.; Ekinci Akdemir, F.N.; Eraslan, E.; Özbek Şebin, S.; Güzel Erdoğan, D.; Nacar, T. An Overview of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury: Review on Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Response. Eurasian J. Med. 2022, 54 (Suppl. S1), 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sul, O.J.; Choi, H.W.; Park, S.H.; Kim, M.J.; Ra, S.W. Effects of heated tobacco products and conventional cigarettes on oxidative stress and inflammation in alveolar macrophages. Toxicol. In Vitro 2026, 110, 106151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzoog, B.A. Cytokines and Regulating Epithelial Cell Division. Curr. Drug Targets 2024, 25, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voirin, A.C.; Perek, N.; Roche, F. Inflammatory stress induced by a combination of cytokines (IL-6, IL-17, TNF-α) leads to a loss of integrity on bEnd.3 endothelial cells in vitro BBB model. Brain Res. 2020, 1730, 146647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Nie, X.K.; Chen, Z.C.; Zhou, S.J.; Lin, X.H.; Zhang, L.; Zhong, D.; Xiao, B.Y.; Jiang, S.Q.; Huang, W.Y.; et al. Mechanism Study on Inhibition of EPHA2 Expression Impaired Skin Barrier Function by Gefitinib. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 34, e70145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, A.R.; Kucera, C.; Srivastava, S.; Paily, R.; Stephens, D.; Lorkiewicz, P.; Wilkey, D.W.; Merchant, M.; Bhatnagar, A.; Carll, A.P. Acute and Persistent Cardiovascular Effects of Menthol E-Cigarettes in Mice. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 14, e037420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenka, S.; Simon, S.R. Effects of E-Cigarette Refill Liquid Flavorings with and without Nicotine on Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, A.; Ghosh, A. Carbonyl Profiles of Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (ENDS) Aerosols Reflect Both the Chemical Composition and the Numbers of E-Liquid Ingredients-Focus on the In Vitro Toxicity of Strawberry and Vanilla Flavors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoka, P.; Lachowicz, J.; Cwiklińska, M.; Lukaszewicz, A.; Rybak, A.; Baranowska, U.; Holownia, A. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Oxidative Stress and Autophagy in Human Alveolar Epithelial Cell Line (A549 Cells). Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1176, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindeløv, L.L.; Christensen, I.J.; Nissen, N.I. A detergent-trypsin method for the preparation of nuclei for flow cytometric DNA analysis. Cytometry 1983, 3, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Joseph, J.A. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scatter Area, Vector Size, Slope of the Central Tendency Line, and Distribution of A549 Cells on Scatterplots of Oxidative Stress vs. IL-6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Relative Units) | ECA 1 | ECA 2 | ECA 3 | ECA 4 |

| Scatter area | 101.1 ± 13.7 | 100.0 ± 9.1 | 110.2 ± 16.4 | 115.4 ± 10.2 *^ |

| Vector size | 1.0 ± 0.21 | 1.0 ± 0.19 | 1.83 ± 0.22 **^^ | 1.29 ± 0.17 *^^## |

| Slope of the central tendency line | 0.90 ± 0.10 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 0.97 ± 0.12 | 0.90 ± 0.15 |

| Zone I cells | 2.9 ± 0.31 | 3.7 ± 0.35 * | 3.5 ± 0.40 | 4.0 ± 0.51 ** |

| Zone II cells | 8.9 ± 0.43 | 10.3 ± 0.97 ** | 12.6 ± 0.77 **^^ | 17.7 ± 0.61 **^^## |

| Zone III cell | 11.2 ± 1.04 | 12.5 ± 0.98 | 12.3 ± 0.87 | 15.4 ± 1.45 **^^## |

| Zone IV cells | 77.0 ± 9.4 | 73.5 ± 10.2 | 71.6 ± 9.1 | 62.9 ± 9.7 * |

| II/IV ratio | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.03 *^ | 0.28 ± 0.06 **^^# |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roslan, M.; Milewska, K.; Szoka, P.; Warpechowski, K.; Milkowska, U.; Holownia, A. Diverse Impact of E-Cigarette Aerosols on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Lung Alveolar Epithelial Cells (A549). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10967. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210967

Roslan M, Milewska K, Szoka P, Warpechowski K, Milkowska U, Holownia A. Diverse Impact of E-Cigarette Aerosols on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Lung Alveolar Epithelial Cells (A549). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):10967. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210967

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoslan, Maciej, Katarzyna Milewska, Piotr Szoka, Kacper Warpechowski, Urszula Milkowska, and Adam Holownia. 2025. "Diverse Impact of E-Cigarette Aerosols on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Lung Alveolar Epithelial Cells (A549)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 10967. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210967

APA StyleRoslan, M., Milewska, K., Szoka, P., Warpechowski, K., Milkowska, U., & Holownia, A. (2025). Diverse Impact of E-Cigarette Aerosols on Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Lung Alveolar Epithelial Cells (A549). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 10967. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210967