A Highly Immunogenic and Cross-Reactive Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate Against Duck Hepatitis A Virus: Immunoinformatics Design and Preliminary Experimental Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Sequence Retrieval

2.2. B-Cell Epitope Prediction

2.3. Prediction of HTL Epitopes

2.4. Prediction of CTL Epitopes

2.5. Toxicity Prediction of the Selected Epitopes

2.6. Cross-Genotype Conservation of Candidate Epitopes

2.7. Designing Multi-Epitope Subunit Vaccine Candidate Construct

2.8. Prediction of Antigenicity and Allergenicity

2.9. Prediction of Physicochemical Properties

2.10. Tertiary Structure Prediction

2.11. High-Quality Tertiary Structure Model Validation

2.12. Molecular Docking

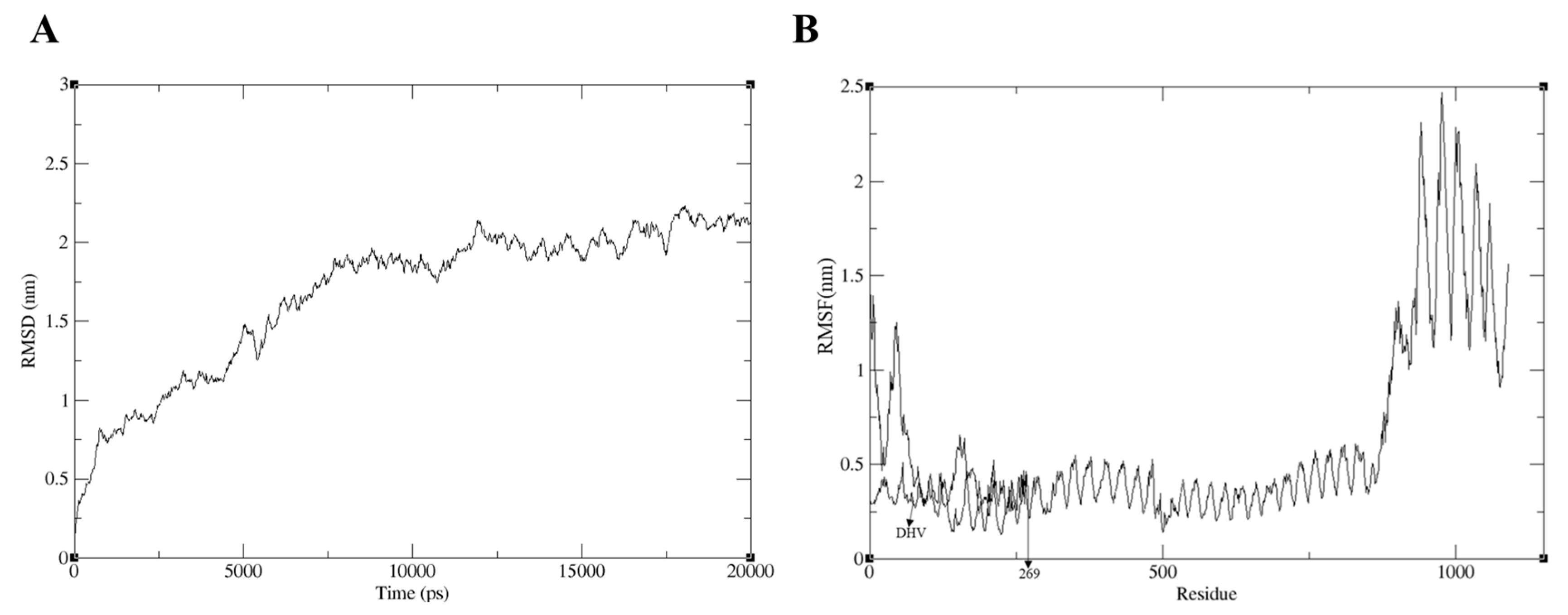

2.13. MD Simulation

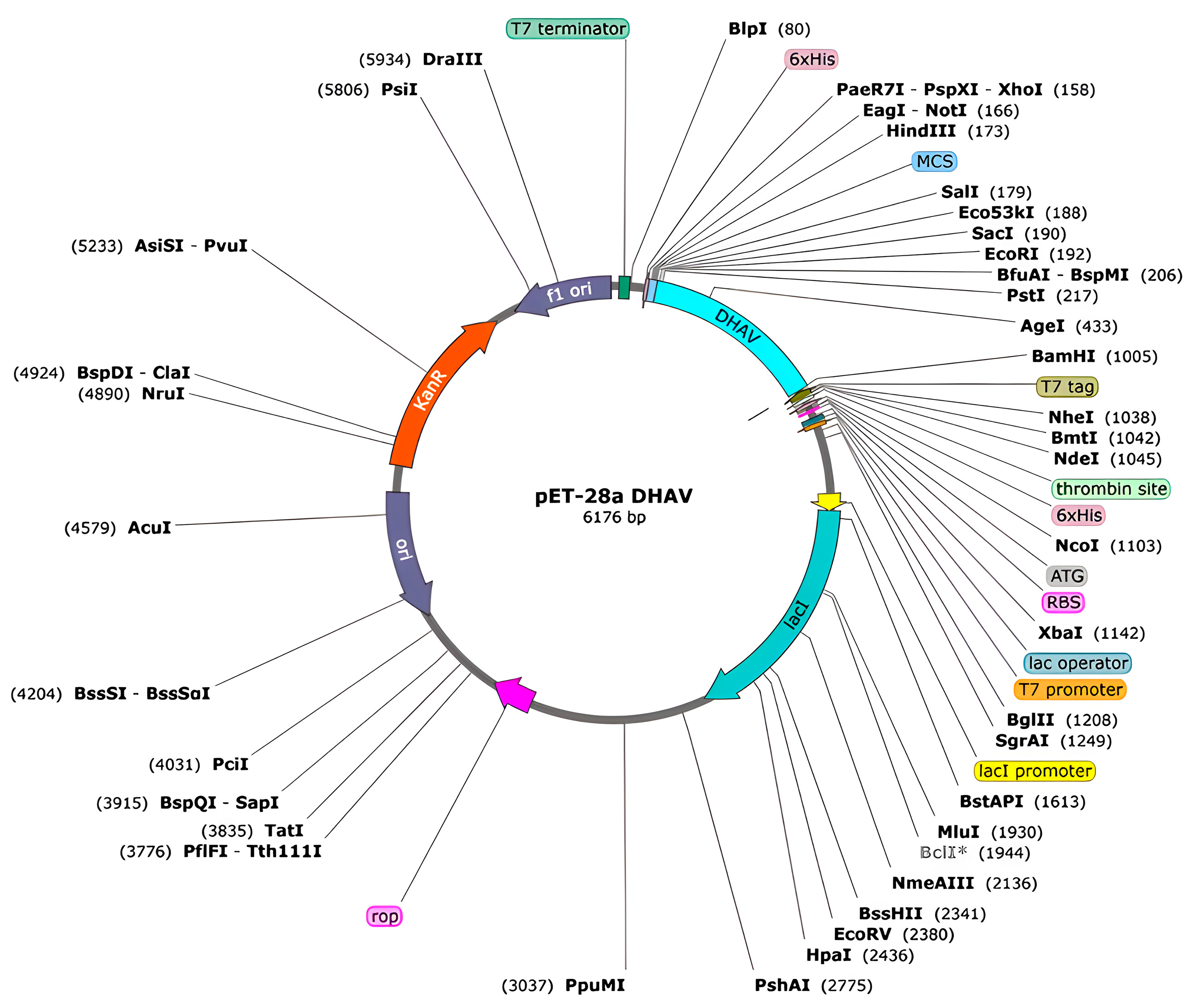

2.14. In Silico Cloning into a Microbial Expression Vector

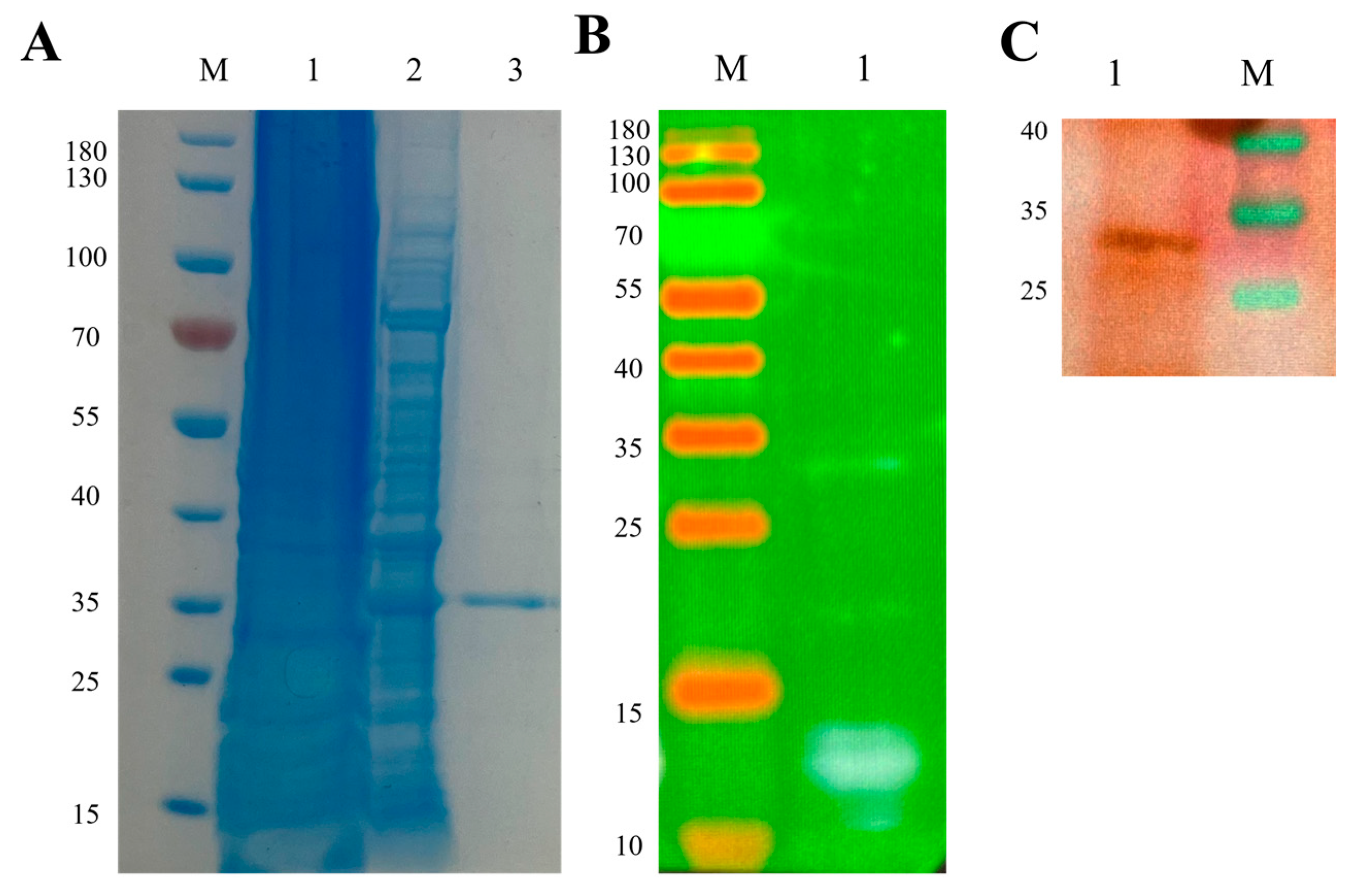

2.15. Expression and Verification of Subunit Vaccine Candidate

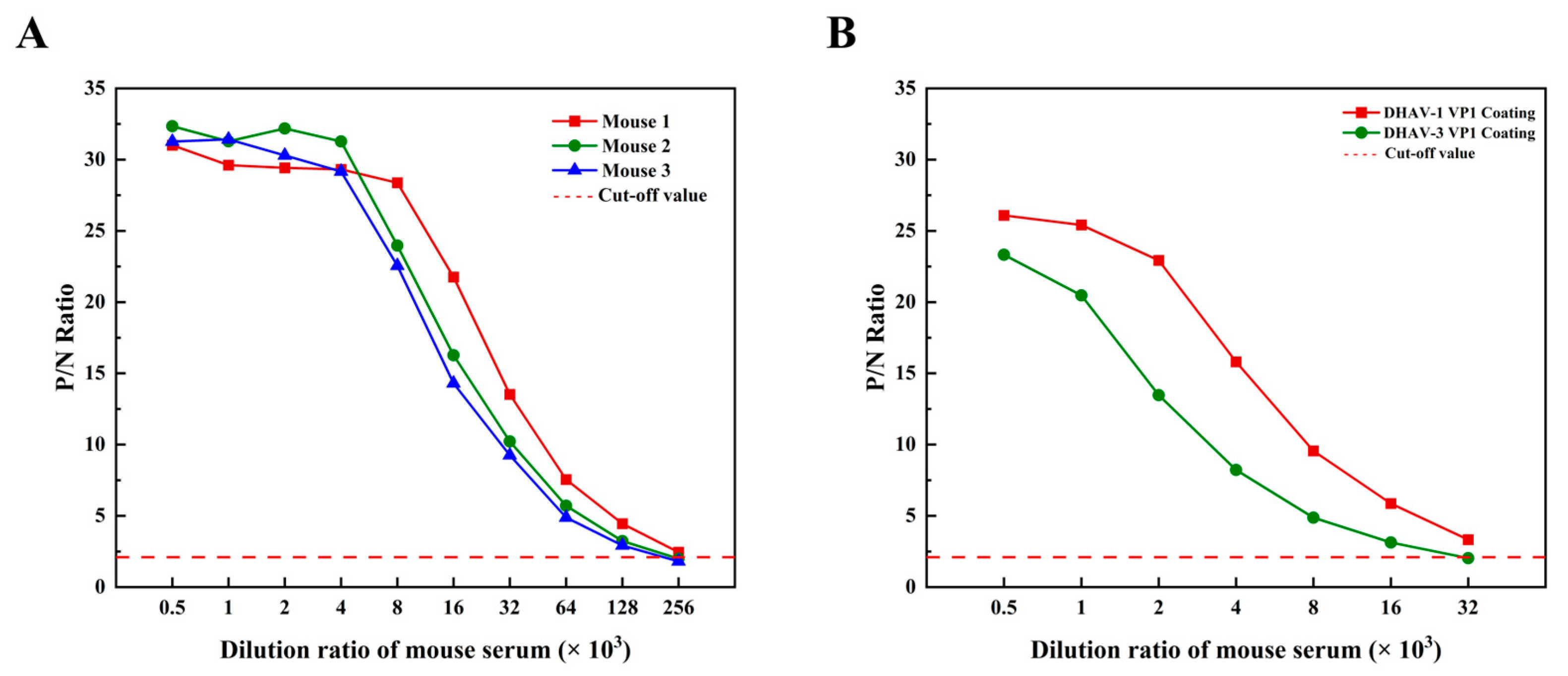

2.16. Induction of a High-Titer Antibody Response by the Vaccine Candidate

2.17. Serological Cross-Reactivity of the Vaccine Candidate Against DHAV Genotypes

3. Methodology

3.1. DHAV Protein Sequence Retrieval

3.2. Prediction of Linear B-Cell Epitopes

3.3. Prediction of Helper T-Cell Epitopes

3.4. Prediction of Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Epitopes

3.5. Prediction of Toxic Immunogenicity of Cellular Epitopes

3.6. Epitope Conservancy Analysis

3.7. Design of a Candidate Multi-Epitope Subunit Vaccine

3.8. Prediction of Antigenicity and Allergenicity of the Designed Subunit Vaccine Candidate

3.9. Prediction of Various Physicochemical Properties

3.10. Prediction of Tertiary Structure

3.11. Optimization and Verification of Tertiary Structure

3.12. Protein–Protein Docking

3.13. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

3.14. Codon Optimization and Computational Cloning Simulation

3.15. Prokaryotic Expression and Verification of Multi-Epitope Subunit Vaccine Candidate

3.16. Experimental Verification of Multi-Epitope Subunit Vaccine

3.16.1. Preclinical Proof-of-Concept for Vaccine Candidate Immunogenicity

3.16.2. Preclinical Proof-of-Concept for Vaccine Candidate Cross-Reactivity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Lin, S.; Li, P.; Lan, J.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S. Construction and characterization of an improved DNA-launched infectious clone of duck hepatitis A virus type 1. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.; Zhang, D. Molecular analysis of duck hepatitis virus type 1. Virol. J. 2007, 361, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Dai, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, D.; Ni, X.; Zeng, Y.; Pan, K. Surface Display of Duck Hepatitis A Virus Type 1 VP1 Protein on Bacillus subtilis Spores Elicits Specific Systemic and Mucosal Immune Responses on Mice. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Wei, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Xing, G.; Hou, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Whole-transcriptome sequencing revealed the role of noncoding RNAs in susceptibility and resistance of Pekin ducks to DHAV-3. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, S.; Liu, D.; Fan, W.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. Dynamic Transcriptome Reveals the Mechanism of Liver Injury Caused by DHAV-3 Infection in Pekin Duck. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 568565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Yin, X.; Bai, X.; Ge, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, M.; et al. Improved one-tube RT-PCR method for simultaneous detection and genotyping of duck hepatitis A virus subtypes 1 and 3. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0219750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfan, A.M.; Selim, A.A.; Moursi, M.K.; Nasef, S.A.; Abdelwhab, E.M. Epidemiology and molecular characterisation of duck hepatitis A virus from different duck breeds in Egypt. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 177, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yuan, W.; Yang, Y.; Yao, F.; Ming, K.; Liu, J. Inhibition mechanisms of baicalin and its phospholipid complex against DHAV-1 replication. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3816–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zeng, L.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yao, F.; Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J. Anti-DHAV-1 reproduction and immuno-regulatory effects of a flavonoid prescription on duck virus hepatitis. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1545–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xian, L.; Song, M.; Zeng, L.; Xiong, W.; Liu, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, D.; Hu, Y. Effects of Bush Sophora Root polysaccharide and its sulfate on immuno-enhancing of the therapeutic DVH. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 80, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Liu, B.; Sun, C.; Zhao, L.; Chen, H. Construction of the recombinant duck enteritis virus delivering capsid protein VP0 of the duck hepatitis A virus. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 249, 108837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Han, X.; Zhu, C.; Jiao, W.; Liu, R.; Feng, Z.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wan, C.; Lai, Z.; et al. Development of the first officially licensed live attenuated duck hepatitis A virus type 3 vaccine strain HB80 in China and its protective efficacy against DHAV-3 infection in ducks. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, H.T.; Le, X.T.; Do, R.T.; Hoang, C.T.; Nguyen, K.T.; Le, T.H. Molecular genotyping of duck hepatitis A viruses (DHAV) in Vietnam. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2016, 10, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, B.A.; Saraf, D.; Sharma, T.; Sinha, R.; Singh, S.; Sood, S.; Gupta, P.; Gupta, A.; Mishra, K.; Kumari, P.; et al. Identification of vaccine targets & design of vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus using computational and deep learning-based approaches. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13380. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulhameed Odhar, H.; Hashim, A.F.; Humadi, S.S.; Ahjel, S.W. Design and construction of multi epitope- peptide vaccine candidate for rabies virus. Bioinformation 2023, 19, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Zhou, Z.; Huayu, M.; Wang, L.; Feng, L.; Xiao, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xin, M.; Tang, F.; Li, R. A multi-epitope vaccine GILE against Echinococcus Multilocularis infection in mice. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1091004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yao, F.; Lv, J.; Ding, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H.; et al. Identification of B-cell epitopes on structural proteins VP1 and VP2 of Senecavirus A and development of a multi-epitope recombinant protein vaccine. Virology 2023, 582, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, R.; Lin, W.; Li, C.; Zhang, T.; Meng, F.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y. Evidence of VP1 of duck hepatitis A type 1 virus as a target of neutralizing antibodies and involving receptor-binding activity. Virus Res. 2017, 227, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelaziz, M.O.; Raftery, M.J.; Weihs, J.; Bielawski, O.; Edel, R.; Köppke, J.; Vladimirova, D.; Adler, J.M.; Firsching, T.; Voß, A.; et al. Early protective effect of a (“pan”) coronavirus vaccine (PanCoVac) in Roborovski dwarf hamsters after single-low dose intranasal administration. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1166765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, T.N.; Cheng, L.T. Development of a Subunit Vaccine against Duck Hepatitis A Virus Serotype 3. Vaccines 2022, 10, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.P.; Liu, L.; Gu, L.L.; Wu, S.; Guo, C.M.; Feng, Q.; Xia, W.L.; Yuan, C.; Zhu, S.Y. Expression of duck hepatitis A virus type 1 VP3 protein mediated by avian adeno-associated virus and its immunogenicity in ducklings. Acta Virol. 2019, 63, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham Peele, K.; Srihansa, T.; Krupanidhi, S.; Ayyagari, V.S.; Venkateswarulu, T.C. Design of multi-epitope vaccine candidate against SARS-CoV-2: A in-silico study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 3793–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.L.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, R.H.; Yang, L.; Li, J.X.; Xie, Z.J.; Zhu, Y.L.; Jiang, S.J.; Si, X.K. Improved duplex RT-PCR assay for differential diagnosis of mixed infection of duck hepatitis A virus type 1 and type 3 in ducklings. J. Virol. Methods 2013, 192, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehér, E.; Jakab, S.; Bali, K.; Kaszab, E.; Nagy, B.; Ihász, K.; Bálint, A.; Palya, V.; Bányai, K. Genomic Epidemiology and Evolution of Duck Hepatitis A Virus. Viruses 2021, 13, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Sheng, Z.Z.; Huang, B.; Qi, L.H.; Li, Y.F.; Yu, K.X.; Liu, C.X.; Qin, Z.M.; Wang, D.; Song, M.X.; et al. Molecular Evolution and Genetic Analysis of the Major Capsid Protein VP1 of Duck Hepatitis A Viruses: Implications for Antigenic Stability. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, R.; Sundaram, R.S.; Rao, P.L.; Nathan, D.J.S.; Muthukrishnan, M.; Manoharan, S.; Srinivasan, J.; Balakrishnan, G.; Soundararajan, C.; Subbiah, M. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses of the first complete genome sequence of Duck hepatitis A virus genotype 2 from India. Gene 2025, 941, 149236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Baldwin, J.; Brar, D.; Salunke, D.B.; Petrovsky, N. Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists as a driving force behind next-generation vaccine adjuvants and cancer therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2022, 70, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Wang, M.; Ou, X.; Sun, D.; Cheng, A.; Zhu, D.; Chen, S.; Jia, R.; Liu, M.; Sun, K.; et al. Virologic and Immunologic Characteristics in Mature Ducks with Acute Duck Hepatitis A Virus 1 Infection. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiman, S.; Alhamhoom, Y.; Ali, F.; Rahman, N.; Rastrelli, L.; Khan, A.; Farooq, Q.U.A.; Ahmed, A.; Khan, A.; Li, C. Multi-epitope chimeric vaccine design against emerging Monkeypox virus via reverse vaccinology techniques- a bioinformatics and immunoinformatics approach. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 985450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Demneh, F.M.; Rehman, B.; Almanaa, T.N.; Akhtar, N.; Pazoki-Toroudi, H.; Shojaeian, A.; Ghatrehsamani, M.; Sanami, S. In silico design of a novel multi-epitope vaccine against HCV infection through immunoinformatics approaches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitaloka, D.A.E.; Izzati, A.; Amirah, S.R.; Syakuran, L.A. Multi Epitope-Based Vaccine Design for Protection Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and SARS-CoV-2 Coinfection. Adv. Appl. Bioinform. Chem. AABC 2022, 15, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolina, J.S.; Van Braeckel-Budimir, N.; Thomas, G.D.; Salek-Ardakani, S. CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion in Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 715234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.X.; Lim, J.; Poh, C.L. Identification and selection of immunodominant B and T cell epitopes for dengue multi-epitope-based vaccine. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2021, 210, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Kumar, A. Designing an efficient multi-epitope vaccine against Campylobacter jejuni using immunoinformatics and reverse vaccinology approach. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 147, 104398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Li, M.; Niu, C.; Yu, M.; Xie, X.; Haimiti, G.; Guo, W.; Shi, J.; He, Y.; Ding, J.; et al. Design of multi-epitope vaccine candidate against Brucella type IV secretion system (T4SS). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Shahab, M.; Sarkar, M.M.H.; Hayat, C.; Banu, T.A.; Goswami, B.; Jahan, I.; Osman, E.; Uzzaman, M.S.; Habib, M.A.; et al. Immunoinformatics approach to epitope-based vaccine design against the SARS-CoV-2 in Bangladeshi patients. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rcheulishvili, N.; Mao, J.; Papukashvili, D.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Xie, F.; Pan, X.; Ji, Y.; He, Y.; et al. Designing multi-epitope mRNA construct as a universal influenza vaccine candidate for future epidemic/pandemic preparedness. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 226, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharani, A.; Ezhilarasi, D.R.; Priyadarsini, G.; Abhinand, P.A. Multi-epitope vaccine candidate design for dengue virus. Bioinformation 2023, 19, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, G.; Sethi, S.; Krishna, R. Multi-epitope based vaccine design against Staphylococcus epidermidis: A subtractive proteomics and immunoinformatics approach. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 165, 105484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devantier, K.; Toft-Bertelsen, T.L.; Prestel, A.; Kjær, V.M.S.; Sahin, C.; Giulini, M.; Louka, S.; Spiess, K.; Manandhar, A.; Qvortrup, K.; et al. The SH protein of mumps virus is a druggable pentameric viroporin. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eads3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Ahammad, F.; Nain, Z.; Alam, R.; Imon, R.R.; Hasan, M.; Rahman, M.S. Designing a multi-epitope vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: An immunoinformatics approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudvand, S.; Esmaeili Gouvarchin Ghaleh, H.; Jalilian, F.A.; Farzanehpour, M.; Dorostkar, R. Design of a multi-epitope-based vaccine consisted of immunodominant epitopes of structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 using immunoinformatics approach. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2023, 70, 1189–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Murakami, A.M.; Yonekura, M.; Miyoshi, I.; Itagaki, S.; Niwa, Y. A simple, dual direct expression plasmid system in prokaryotic and mammalian cells. PNAS Nexus 2023, 2, pgad139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand, D.D.; Latham, K.A.; Rosloniec, E.F. Collagen-induced arthritis. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 1269–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Liu, A.; He, P. Innovative Approaches to Combat Duck Viral Hepatitis: Dual-Specific Anti-DHAV-1 and DHAV-3 Yolk Antibodies. Vaccines 2025, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, K.M. Immunoinformatics approach for multi-epitope vaccine design against structural proteins and ORF1a polyprotein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2021, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jyotisha; Singh, S.; Qureshi, I.A. Multi-epitope vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 applying immunoinformatics and molecular dynamics simulation approaches. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 2917–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamedi, H.; Ari, M.M.; Shahlaei, M.; Moradi, S.; Farhadikia, P.; Alvandi, A.; Abiri, R. Designing multi-epitope vaccine against important colorectal cancer (CRC) associated pathogens based on immunoinformatics approach. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostaminia, S.; Aghaei, S.S.; Farahmand, B.; Nazari, R.; Ghaemi, A. Computational Design and Analysis of a Multi-epitope Against Influenza A virus. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2021, 27, 2625–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.S.; Sharma, R.; Kumari, A.; Vyas, N.; Prajapati, V.; Grover, A. Engineering a multi epitope vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 by exploiting its non structural and structural proteins. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 9096–9113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalita, P.; Lyngdoh, D.L.; Padhi, A.K.; Shukla, H.; Tripathi, T. Development of multi-epitope driven subunit vaccine against Fasciola gigantica using immunoinformatics approach. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, L.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, C.; Kuang, H.; Xu, X. A sensitive colorimetric immunosensor for clozapine, norclozapine, and clozapine-N-oxide simultaneous detection based on monoclonal antibodies preparation with homogeneous cross-reactivity. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 385, 127106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, L.; Liu, L.; Kuang, H.; Xu, C.; Xu, X. Rapid determination of amygdalin in almonds and almond-based products using lateral flow immunoassay based on gold nanoparticles. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q.X.; Liu, B.Z.; Deng, H.J.; Wu, G.C.; Deng, K.; Chen, Y.K.; Liao, P.; Qiu, J.F.; Lin, Y.; Cai, X.F.; et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Small, C.M.; Ajithdoss, D.K.; Rodrigues Hoffmann, A.; Mwangi, W.; Esteve-Gassent, M.D. Immunization with a Borrelia burgdorferi BB0172-derived peptide protects mice against lyme disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civera, A.; Galan-Malo, P.; Segura-Gil, I.; Mata, L.; Tobajas, A.P.; Sánchez, L.; Pérez, M.D. Development of sandwich ELISA and lateral flow immunoassay to detect almond in processed food. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai-Kastoori, L.; Schutz-Geschwender, A.R.; Harford, J.A. A systematic approach to quantitative Western blot analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 593, 113608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zeng, H.; Lyu, L.; He, X.; Zhang, X.; Lyu, W.; Chen, W.; Xiao, Y. Age-specific reference intervals for plasma amino acids and their associations with nutrient intake in the Chinese pediatric population. iMeta 2025, 4, e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Yang, L.Q.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, X.Y.; Gao, M.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, J.J.; He, P.L. Blocked conversion of Lactobacillus johnsonii derived acetate to butyrate mediates copper-induced epithelial barrier damage in a pig model. Microbiome 2023, 11, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein Name | Uniprot/NCBI Sequence lD | Antigenicity Score |

|---|---|---|

| Avihepatovirus A (VP1) | ACD68196.1 | 0.4105 |

| Avihepatovirus A (VP1) | ACD68195.1 | 0.4183 |

| Avihepatovirus A (VP3) | ACC78155.1 | 0.4731 |

| Avihepatovirus A (VP3) | ACD68191.1 | 0.4768 |

| Avihepatovirus A (VP0) | ACD68185.1 | 0.4746 |

| Avihepatovirus A (VP0) | ACC78146.1 | 0.5113 |

| S. No. | Epitope | Antigenicity Score | Toxin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EPVCFLN | 1.4923 | Non-Toxin |

| 2 | VPLVRTVQHASTVQELD | 0.7518 | Non-Toxin |

| 3 | SRLVHLVTGQ | 0.8328 | Non-Toxin |

| 4 | CLRWLATPV | 0.6351 | Non-Toxin |

| 5 | AICVIVLGK | 0.6243 | Non-Toxin |

| 6 | IADGEQS | 0.9743 | Non-Toxin |

| 7 | YGNLQMAT | 0.6972 | Non-Toxin |

| S. No. | Epitope | Antigenicity Score | Toxin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IILTIVNNGTTPAMV | 0.4587 | Non-Toxin |

| 2 | SLSVFMGLKKPALFF | 0.4362 | Non-Toxin |

| 3 | GYFRFCLRLKTLAFE | 1.3617 | Non-Toxin |

| 4 | PYGYLMWHVVNRLTV | 0.4496 | Non-Toxin |

| 5 | IMVLRRWQILASFQW | 0.8046 | Non-Toxin |

| S. No. | Epitope | Antigenicity Score | Toxin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VERRSLMNL | 0.6863 | Non-Toxin |

| 2 | TEIDLVVPY | 0.7126 | Non-Toxin |

| 3 | AMVAHSYSM | 0.4858 | Non-Toxin |

| 4 | YQMSWYPIA | 1.5676 | Non-Toxin |

| 5 | SEYAVTAMG | 0.6279 | Non-Toxin |

| 6 | KDFQFTAPL | 1.3095 | Non-Toxin |

| Experimental Animals | Days | Frequency of Immunization | Immunization Dose (μg/Animal) | Adjuvant | Immunization Sites |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c Mouse | 0 | Initially | 50 | FCA | Subcutaneous area of the nape and back of the neck |

| 21 | Secondly | 50 | FIA | ||

| 35 | Thirdly | 50 | FIA | ||

| 49 | Fourthly | 50 | FIA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, A.; He, J.; Cao, Y.; He, P. A Highly Immunogenic and Cross-Reactive Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate Against Duck Hepatitis A Virus: Immunoinformatics Design and Preliminary Experimental Validation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210958

Yang Y, Chen X, Liu A, He J, Cao Y, He P. A Highly Immunogenic and Cross-Reactive Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate Against Duck Hepatitis A Virus: Immunoinformatics Design and Preliminary Experimental Validation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):10958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210958

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yuanhe, Xiaodong Chen, Anguo Liu, Jinxin He, Yunhe Cao, and Pingli He. 2025. "A Highly Immunogenic and Cross-Reactive Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate Against Duck Hepatitis A Virus: Immunoinformatics Design and Preliminary Experimental Validation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 10958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210958

APA StyleYang, Y., Chen, X., Liu, A., He, J., Cao, Y., & He, P. (2025). A Highly Immunogenic and Cross-Reactive Multi-Epitope Vaccine Candidate Against Duck Hepatitis A Virus: Immunoinformatics Design and Preliminary Experimental Validation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 10958. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210958