Retinal Ischemia: Therapeutic Effects and Mechanisms of Paeoniflorin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Free Radical-Induced Cellular Damage (In Human RPE Cells)

2.2. Oxygen Glucose Deprivation (In RGCs)

2.3. Electroretinogram: The Effect of Pre-Ischemic Treatment Paeoniflorin on Ischemic–Reperfusion Injury

2.4. Fluorogold Labeling and Density of RGCs

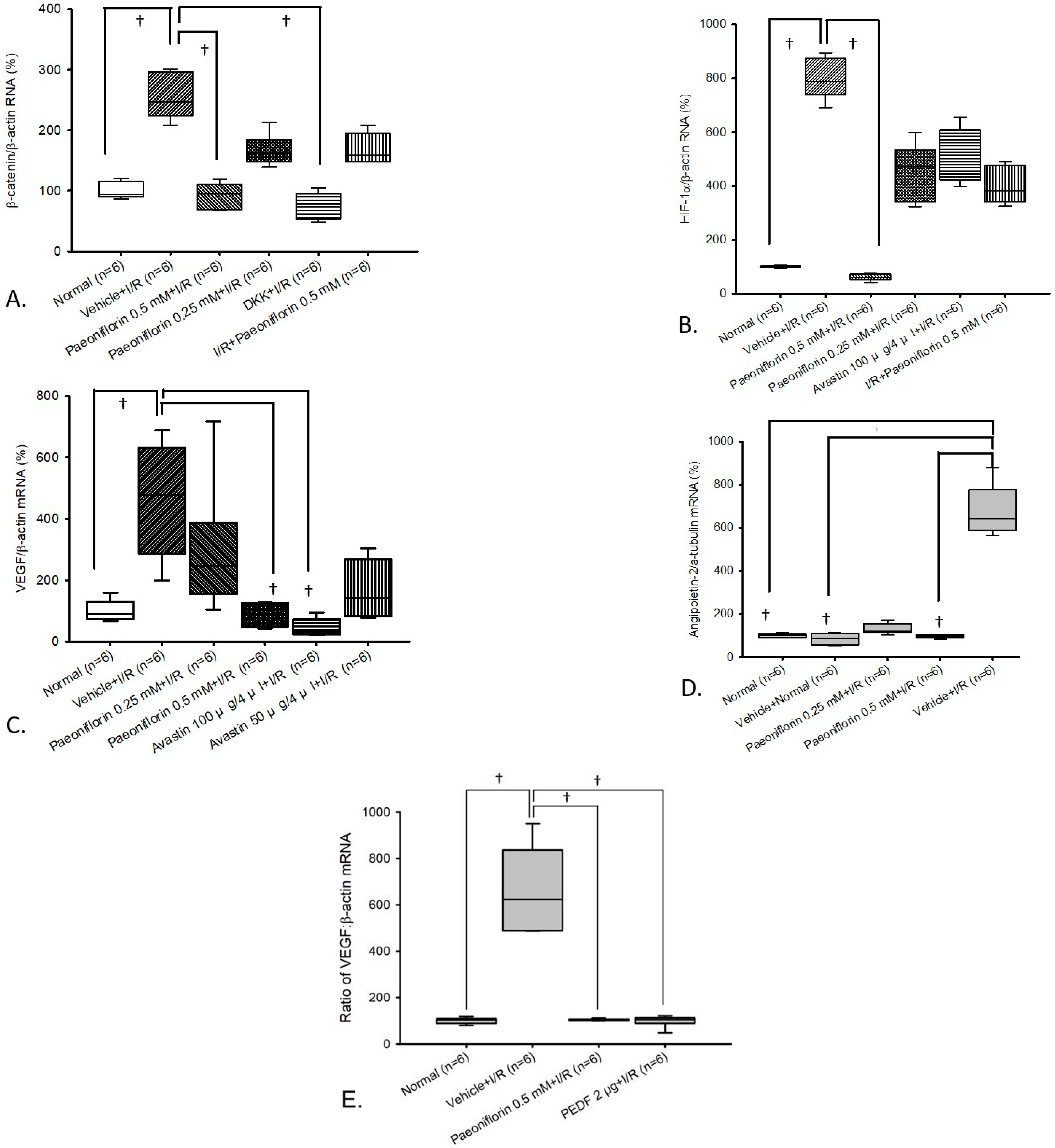

2.5. Measurement of β-Catenin, HIF-1α, VEGF, and Ang-2 in Primary Retinal Cells via Real Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

2.6. Comparison of PEDF (Anti-Angiogenic Agent) Versus Paeoniflorin on VEGF Expression Using mRNA Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. In Vitro Studies

4.1.1. Cell Culture

4.1.2. Free Radical-Induced Cellular Damage

4.1.3. Oxygen–Glucose Deprivation

4.1.4. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium Bromide Assay

4.2. In Vivo Studies

4.2.1. Animals

4.2.2. Chemicals and Drug Administration

4.2.3. Anesthesia and Euthanasia

4.2.4. Ischemia Induction

4.2.5. Electroretinogram Recording

4.2.6. Retrograde Labeling of Retinal Ganglion Cell

4.2.7. HE Staining

4.2.8. TUNEL Assay

4.2.9. Assessment of the Retinal VEGF/β-Catenin/HIF-1α/Ang-2 mRNA Level by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mathew, B.; Chennakesavalu, M.; Sharma, M.; Torres, L.A.; Stelman, C.R.; Tran, S.; Patel, R.; Burg, N.; Salkovski, M.; Kadzielawa, K.; et al. Autophagy and Post-Ischemic Conditioning in Retinal Ischemia. Autophagy 2021, 17, 1479–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, W.W.; Chao, H.W.; Lee, H.F.; Chao, H.M. The Effect of S-Allyl L-Cysteine on Retinal Ischemia: The Contributions of Mcp-1 and Pkm2 in the Underlying Medicinal Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilton, E.J.; Guggenheim, E.J.; Baranyi, B.; Radovanovic, C.; Williams, R.L.; Bradlow, W.; Denniston, A.K.; Mollan, S.P. A Datasheet for the Insight University Hospitals Birmingham Retinal Vein Occlusion Data Set. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2023, 3, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.L.; Su, X.; Li, X.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Klein, R.; Cheng, C.Y.; Wong, T.Y. Global Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Disease Burden Projection for 2020 and 2040: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e106–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhm, E.W.; Buonfiglio, F.; Voigt, A.M.; Bachmann, P.; Safi, T.; Pfeiffer, N.; Gericke, A. Oxidative Stress in the Eye and Its Role in the Pathophysiology of Ocular Diseases. Redox Biol. 2023, 68, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Xiao, L.; Shi, Y.; Li, W.; Xin, X. Natural Products: Protective Effects against Ischemia-Induced Retinal Injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1149708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boia, R.; Ruzafa, N.; Aires, I.D.; Pereiro, X.; Ambrósio, A.F.; Vecino, E.; Santiago, A.R. Neuroprotective Strategies for Retinal Ganglion Cell Degeneration: Current Status and Challenges Ahead. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, W.; Knoops, K.; Boesten, I.; Berendschot, T.T.J.M.; van Zandvoort, M.A.M.J.; Benedikter, B.J.; Webers, C.A.B.; Reutelingsperger, C.P.M.; Gorgels, T.G.M.F. A Time Window for Rescuing Dying Retinal Ganglion Cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuhrmann, S.; Zou, C.; Levine, E.M. Retinal Pigment Epithelium Development, Plasticity, and Tissue Homeostasis. Exp. Eye Res. 2014, 123, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toops, K.A.; Tan, L.X.; Lakkaraju, A. A Detailed Three-Step Protocol for Live Imaging of Intracellular Traffic in Polarized Primary Porcine Rpe Monolayers. Exp. Eye Res. 2014, 124, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Koh, A.; Zhao, C.; Chen, Y. A Review of Intraocular Biomolecules in Retinal Vein Occlusion: Toward Potential Biomarkers for Companion Diagnostics. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 859951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, A.; Boxell, E.; Amoaku, W.M.; Bradley, C. Patient-Reported Reasons for Delay in Diagnosis of Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A National Survey. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2019, 4, e000276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boopathiraj, N.; Wagner, I.V.; Dorairaj, S.K.; Miller, D.D.; Stewart, M.W. Recent Updates on the Diagnosis and Management of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Mayo. Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 8, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallée, A. Curcumin and Wnt/Β-Catenin Signaling in Exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 49, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Qin, K.; Fan, J.; Zhao, G.; Zhao, P.; Zeng, W.; Chen, C.; Wang, A.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, J.; et al. The Evolving Roles of Wnt Signaling in Stem Cell Proliferation and Differentiation, the Development of Human Diseases, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Lee, S.J.; Li, Y. Selective Activation of the Wnt-Signaling Pathway as a Novel Therapy for the Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy and Other Retinal Vascular Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Ma, J.-X. Canonical Wnt Signaling in Diabetic Retinopathy. Vis. Res. 2017, 139, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, M.H.; Han, H.J. Arachidonic Acid Potentiates Hypoxia-Induced Vegf Expression in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells: Involvement of Notch, Wnt, and Hif-1alpha. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009, 297, C207–C216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhang, W.; Liao, Y.; Wang, W.; Deng, X.; Wang, C.; Shi, W. Autophagy: A Double-Edged Sword in Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2025, 30, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heier, J.S.; Singh, R.P.; Wykoff, C.C.; Csaky, K.G.; Lai, T.Y.M.; Loewenstein, A.; Schlottmann, P.G.; Paris, L.P.; Westenskow, P.D.; Quezada-Ruiz, C. The Angiopoietin/Tie Pathway in Retinal Vascular Diseases: A Review. Retina 2021, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuuminen, R.; Loukovaara, S. Increased Intravitreal Angiopoietin-2 Levels in Patients with Retinal Vein Occlusion. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013, 92, e164–e165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regula, J.T.; von Leithner, P.L.; Foxton, R.; Barathi, V.A.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Tun, S.B.B.; Wey, Y.S.; Iwata, D.; Dostalek, M.; Moelleken, J.; et al. Targeting Key Angiogenic Pathways with a Bispecific Crossmab Optimized for Neovascular Eye Diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 1265–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canonica, J.; Foxton, R.; Garrido, M.G.; Lin, C.-M.; Uhles, S.; Shanmugam, S.; Antonetti, D.A.; Abcouwer, S.F.; Westenskow, P.D. Delineating Effects of Angiopoietin-2 Inhibition on Vascular Permeability and Inflammation in Models of Retinal Neovascularization and Ischemia/Reperfusion. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1192464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benest, A.V.; Kruse, K.; Savant, S.; Thomas, M.; Laib, A.M.; Loos, E.K.; Fiedler, U.; Augustin, H.G. Angiopoietin-2 Is Critical for Cytokine-Induced Vascular Leakage. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.J.; Kim, H.-Z.; Hwang, S.-I.; Lee, J.E.; Oh, N.; Jung, K.; Kim, M.; Kim, K.E.; Kim, H.; Lim, N.-K.; et al. Double Antiangiogenic Protein, Daap, Targeting Vegf-a and Angiopoietins in Tumor Angiogenesis, Metastasis, and Vascular Leakage. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.T.; Aboobaker, S.; Maberley, D.; Sharma, S.; Yoganathan, P. Switching to Faricimab from the Current Anti-Vegf Therapy: Evidence-Based Expert Recommendations. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2025, 10, e001967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; Ma, Y.; Lu, M.; Liu, W.; Zhou, H. Paeoniflorin Alleviates Hypoxia/Reoxygenation Injury in Hk-2 Cells by Inhibiting Apoptosis and Repressing Oxidative Damage Via Keap1/Nrf2/Ho-1 Pathway. BMC Nephrol. 2023, 24, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yin, L.; Yang, W.; Wu, Z.; Niu, J. Antioxidant Effects of Paeoniflorin and Relevant Molecular Mechanisms as Related to a Variety of Diseases: A Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Guo, H.; Xia, X.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, S.; Lin, T.; He, W.; Jin, L.; Cheng, J.; Hao, L.; et al. Paeoniflorin Alleviated Stz-Induced Diabetic Retinopathy Via Regulation of the Pdi/Adam17/Mertk Pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 155, 114571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-F.; Wu, K.-J.; Wood, W.G. Paeonia Lactiflora Extract Attenuating Cerebral Ischemia and Arterial Intimal Hyperplasia Is Mediated by Paeoniflorin Via Modulation of Vsmc Migration and Ras/Mek/Erk Signaling Pathway. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 482428. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Qi, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Cai, L.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Su, B.; Nie, H. Paeoniflorin Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Via Inhibition of Dendritic Cell Function and Th17 Cell Differentiation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L. Preparation of Paeoniflorin from the Stems and Leaves of Paeonia Lactiflora Pall. ‘Zhongjiang’ through Green Efficient Microwave-Assisted Extraction and Subcritical Water Extraction. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 163, 113332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.-Y.; Dai, S.-M. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Effects of Paeonia Lactiflora Pall., a Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2011, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, C. Paeoniflorin Suppresses the Apoptosis and Inflammation of Human Coronary Artery Endothelial Cells Induced by Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein by Regulating the Wnt/Β-Catenin Pathway. Pharm. Biol. 2023, 61, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wei, W. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunoregulatory Effects of Paeoniflorin and Total Glucosides of Paeony. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 207, 107452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, Y.; Tan, R.; Wu, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Zeng, F. Paeoniflorin Affects Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression by Inhibiting Wnt/Β-Catenin Pathway through Downregulation of 5-Ht1d. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2021, 22, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Hu, B.; Li, J.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, H.; Guo, Y.; Mao, Y.; Cao, W. Paeoniflorin Inhibits Colorectal Cancer Cell Stemness through the Mir-3194-5p/Catenin Beta-Interacting Protein 1 Axis. Kaohsiung J. Med Sci. 2023, 39, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.-M.; Liu, X.-Q.; Liu, J.-H.; Pan, W.H.-T.; Zhang, X.-M.; Hu, L.; Chao, H.-M. Chi-Ju-Di-Huang-Wan Protects Rats against Retinal Ischemia by Downregulating Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 and Inhibiting P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase. Chin. Med. 2016, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Léveillard, T. Modulating Antioxidant Systems as a Therapeutic Approach to Retinal Degeneration. Redox Biol. 2022, 57, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Pan, W.H.; Liu, J.H.; Chen, M.M.; Liu, C.M.; Yeh, M.Y.; Tsai, S.K.; Young, M.S.; Zhang, X.M.; Chao, H.M. The Effects and Underlying Mechanisms of S-Allyl L-Cysteine Treatment of the Retina after Ischemia/Reperfusion. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 28, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, S.; Yoshida, A.; Ishibashi, T.; Elner, S.G.; Elner, V.M. Role of Mcp-1 and Mip-1alpha in Retinal Neovascularization During Postischemic Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Retinal Neovascularization. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2003, 73, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.W.H.; Chao, H.M. Catapol Might Protect against Retinal Ischaemia by Anti-Oxidation, Anti-Ischaemia, Wnt Pathway Inhibition and Vegf Downregulation. Acta Ophthalmol. 2024, 102, S279. [Google Scholar]

- Noma, H.; Funatsu, H.; Mimura, T.; Harino, S.; Eguchi, S.; Hori, S. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion with Macular Edema. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2010, 248, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, Y.; Deering, T.; Oshima, S.; Nambu, H.; Reddy, P.S.; Kaleko, M.; Connelly, S.; Hackett, S.F.; Campochiaro, P.A. Angiopoietin-2 Enhances Retinal Vessel Sensitivity to Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. J. Cell. Physiol. 2004, 199, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadlapatla, R.K.; Vadlapudi, A.D.; Pal, D.; Mukherji, M.; Mitra, A.K. Ritonavir Inhibits Hif-1α-Mediated Vegf Expression in Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells in Vitro. Eye 2014, 28, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Ba-Charvet, K.T.; Rebsam, A. Neurogenesis and Specification of Retinal Ganglion Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abcouwer, S.F.; Lin, C.M.; Wolpert, E.B.; Shanmugam, S.; Schaefer, E.W.; Freeman, W.M.; Barber, A.J.; Antonetti, D.A. Effects of Ischemic Preconditioning and Bevacizumab on Apoptosis and Vascular Permeability Following Retinal Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 5920–5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Peng, Z.; Li, Y.; Sahn, J.J.; Hodges, T.R.; Chou, T.H.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Jiao, S.; Porciatti, V.; et al. Σ(2)R/Tmem97 in Retinal Ganglion Cell Degeneration. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 20753. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S. Neuroprotective Effects of Apigenin on Retinal Ganglion Cells in Ischemia/Reperfusion: Modulating Mitochondrial Dynamics in In Vivo and In Vitro Models. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, H.W.-H.; Chen, Y.-K.; Liu, J.-H.; Pan, H.-T.; Lin, H.-M.; Chao, H.-M. Emodin Protected against Retinal Ischemia Insulted Neurons through the Downregulation of Protein Overexpression of Β-Catenin and Vascular Endothelium Factor. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chao, W.W.-J.; Chao, H.W.-H.; Peng, P.-H.; Lee, Y.-T.; Chao, H.-M. Retinal Ischemia: Therapeutic Effects and Mechanisms of Paeoniflorin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10924. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210924

Chao WW-J, Chao HW-H, Peng P-H, Lee Y-T, Chao H-M. Retinal Ischemia: Therapeutic Effects and Mechanisms of Paeoniflorin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):10924. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210924

Chicago/Turabian StyleChao, Windsor Wen-Jin, Howard Wen-Haur Chao, Pai-Huei Peng, Yi-Tzu Lee, and Hsiao-Ming Chao. 2025. "Retinal Ischemia: Therapeutic Effects and Mechanisms of Paeoniflorin" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 10924. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210924

APA StyleChao, W. W.-J., Chao, H. W.-H., Peng, P.-H., Lee, Y.-T., & Chao, H.-M. (2025). Retinal Ischemia: Therapeutic Effects and Mechanisms of Paeoniflorin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 10924. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210924