Valorization of Mushroom Residues for Functional Food Packaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

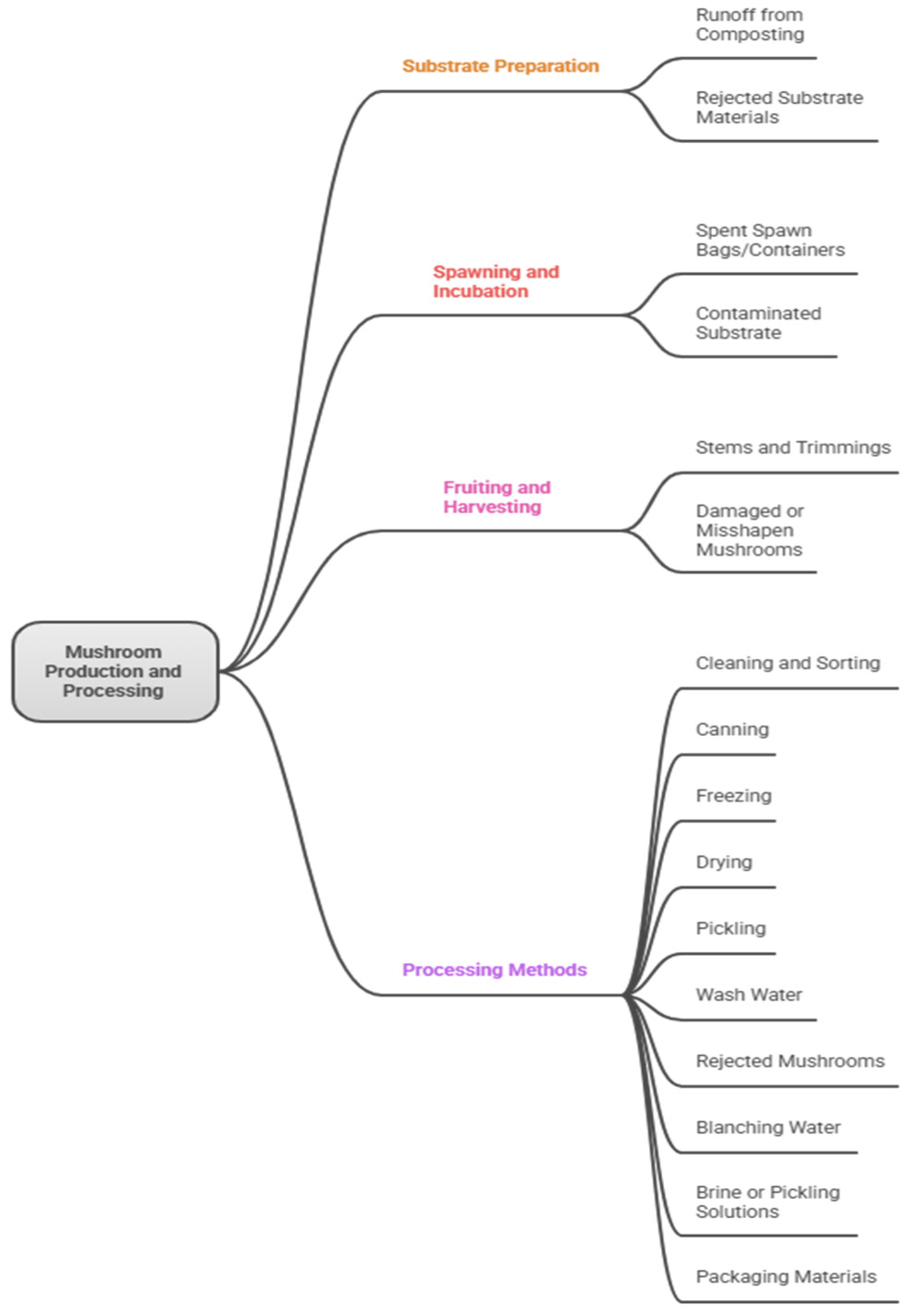

2. Mushroom Industry, and Characterization of Mushroom Residues

2.1. Residue Types

- Trimming residues—Discarded stipes (stems), caps, and misshapen or undersized mushrooms, often from quality control during harvesting and packaging, representing 5–10% of fresh yield.

- Extraction residues—Leftover solids from processing mushroom extracts for bioactive compounds (e.g., polysaccharides or beta-glucans), typically fiber-rich and low in soluble nutrients.

- Mycelium residues—Excess fungal biomass from spawn production or failed cultivation batches, containing high protein and enzyme content.

2.2. Quantitative Estimates (Global and Regional Volumes)

2.3. Physicochemical and Microbiological Characteristics Relevant to Valorization

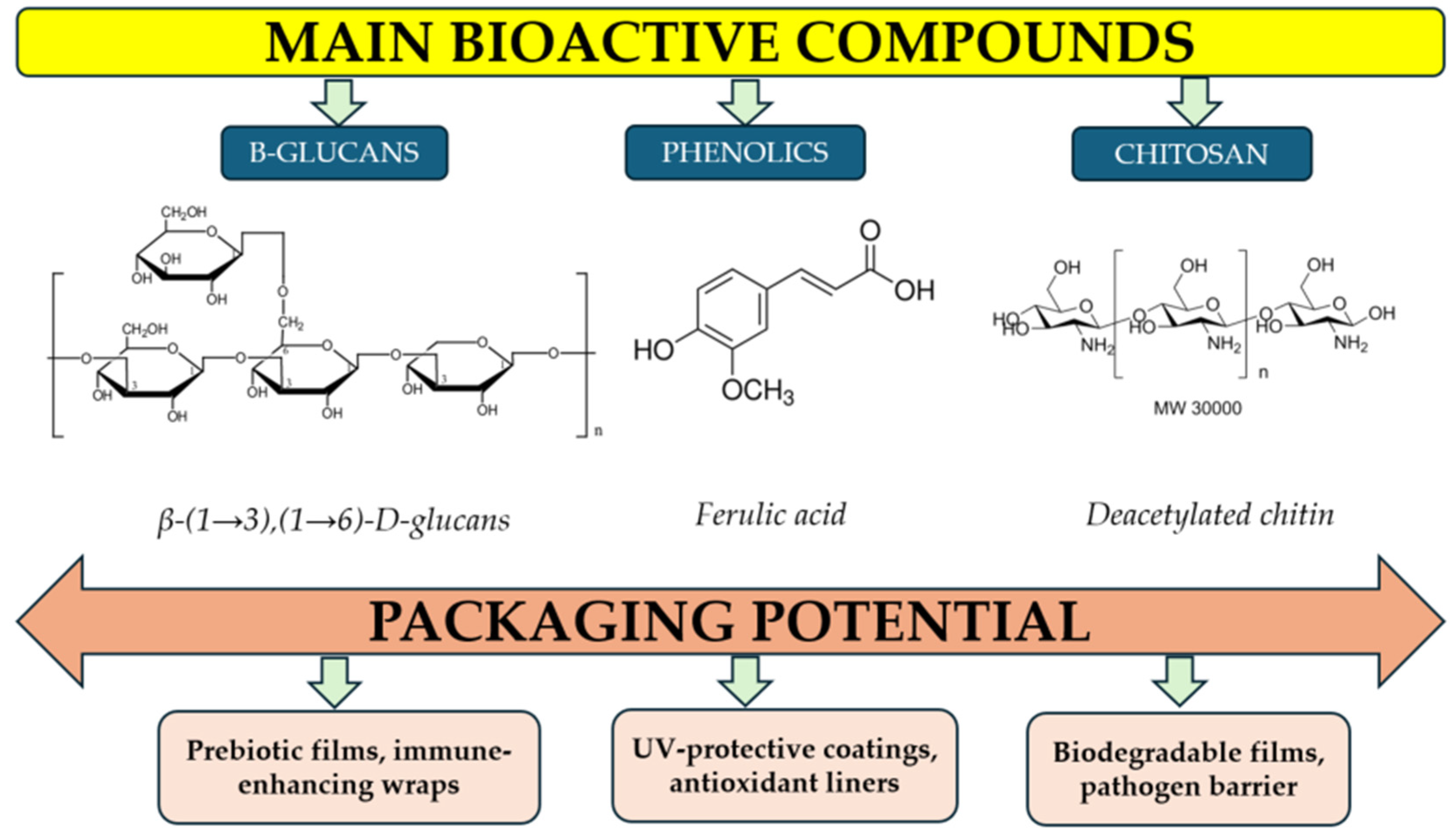

3. Molecular and Functional Constituents of Mushroom Residues

3.1. Major Bioactive Compounds (β-Glucans, Phenolics, Proteins, Chitin)

3.1.1. Polysaccharides

3.1.2. Phenolic Compounds

3.1.3. Proteins and Peptides

3.2. Minor Components and Synergistic Effects

3.3. Implications for Packaging Functionality

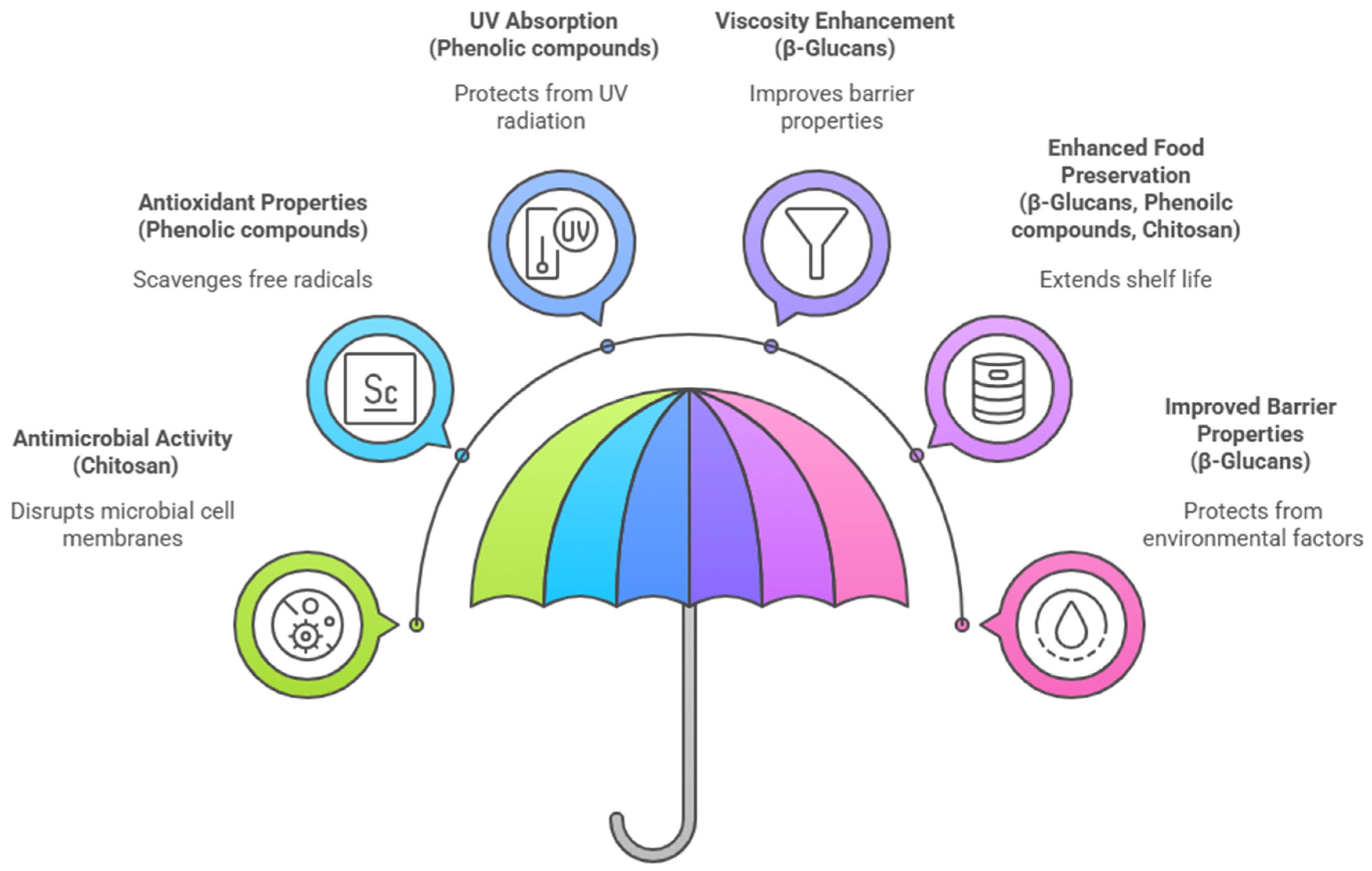

4. Functional Properties of Extracts and Derivatives

4.1. Overview of Functional Roles in Food Packaging

4.2. Antioxidant Properties

4.3. Antimicrobial, Antifungal, and Antiviral Effects

4.4. Barrier and UV-Protective Properties

4.5. Multifunctional and Synergistic Effects

4.6. Structure–Function Insights

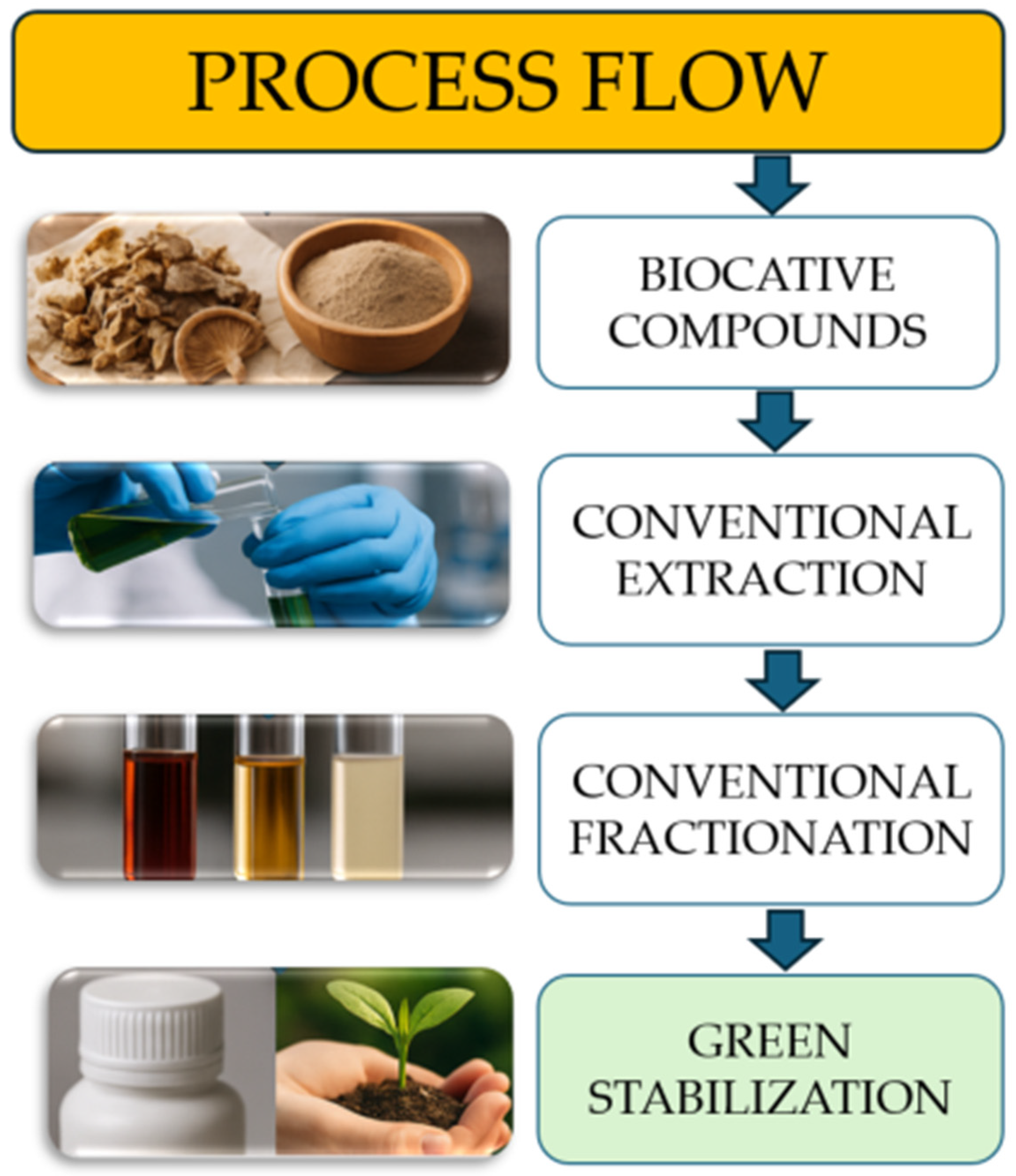

5. Extraction, Fractionation, and Modification Techniques

5.1. Green Extraction Methods

5.2. Process Optimization and Scalability

6. Integration into Biopolymers and Packaging Films/Coatings

6.1. Incorporation Strategies (Blending, Coating, Grafting)

6.2. Effects on Packaging Properties

6.3. Bioactivity Retention and Safety Aspects

7. Case Studies and Emerging Applications

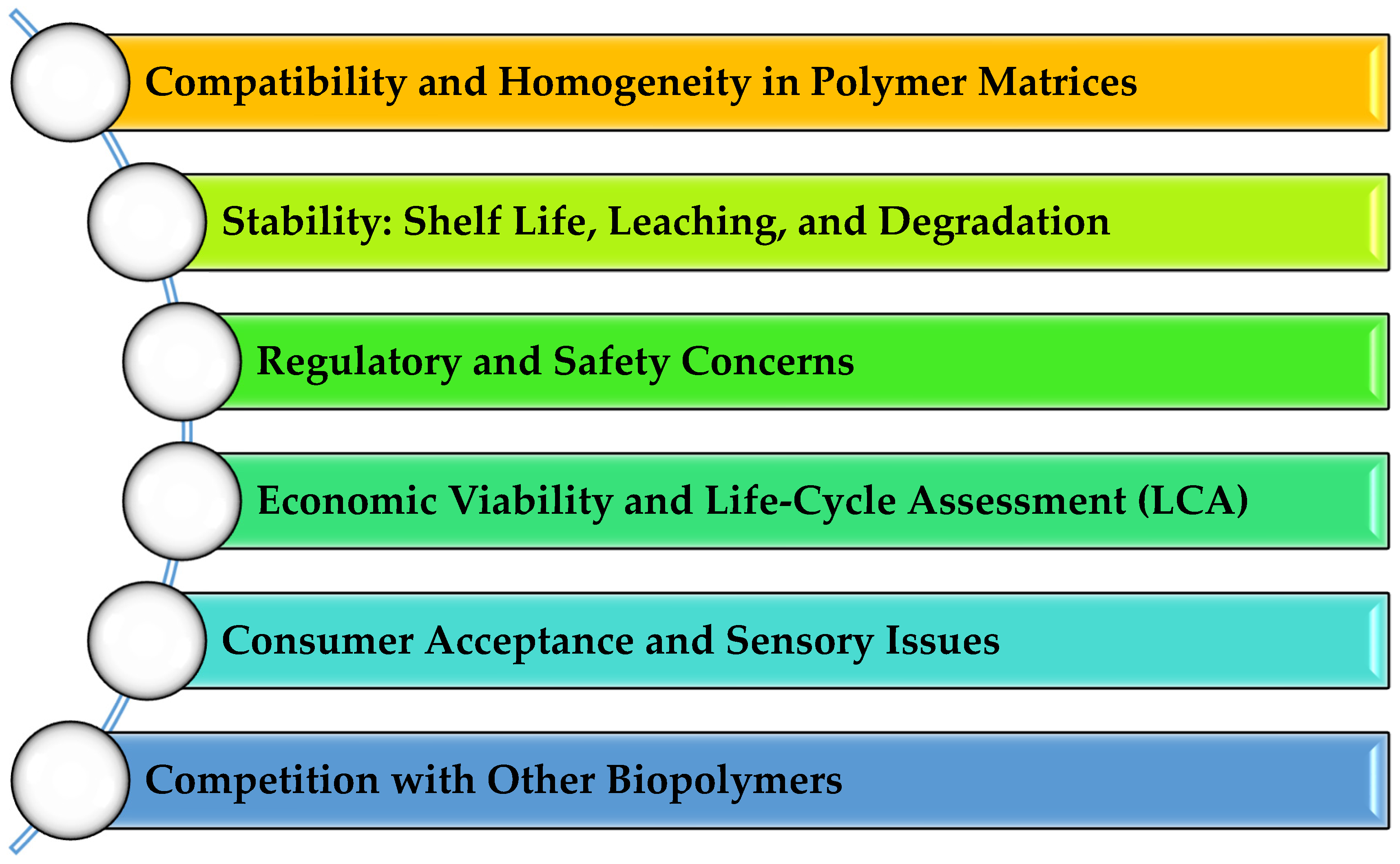

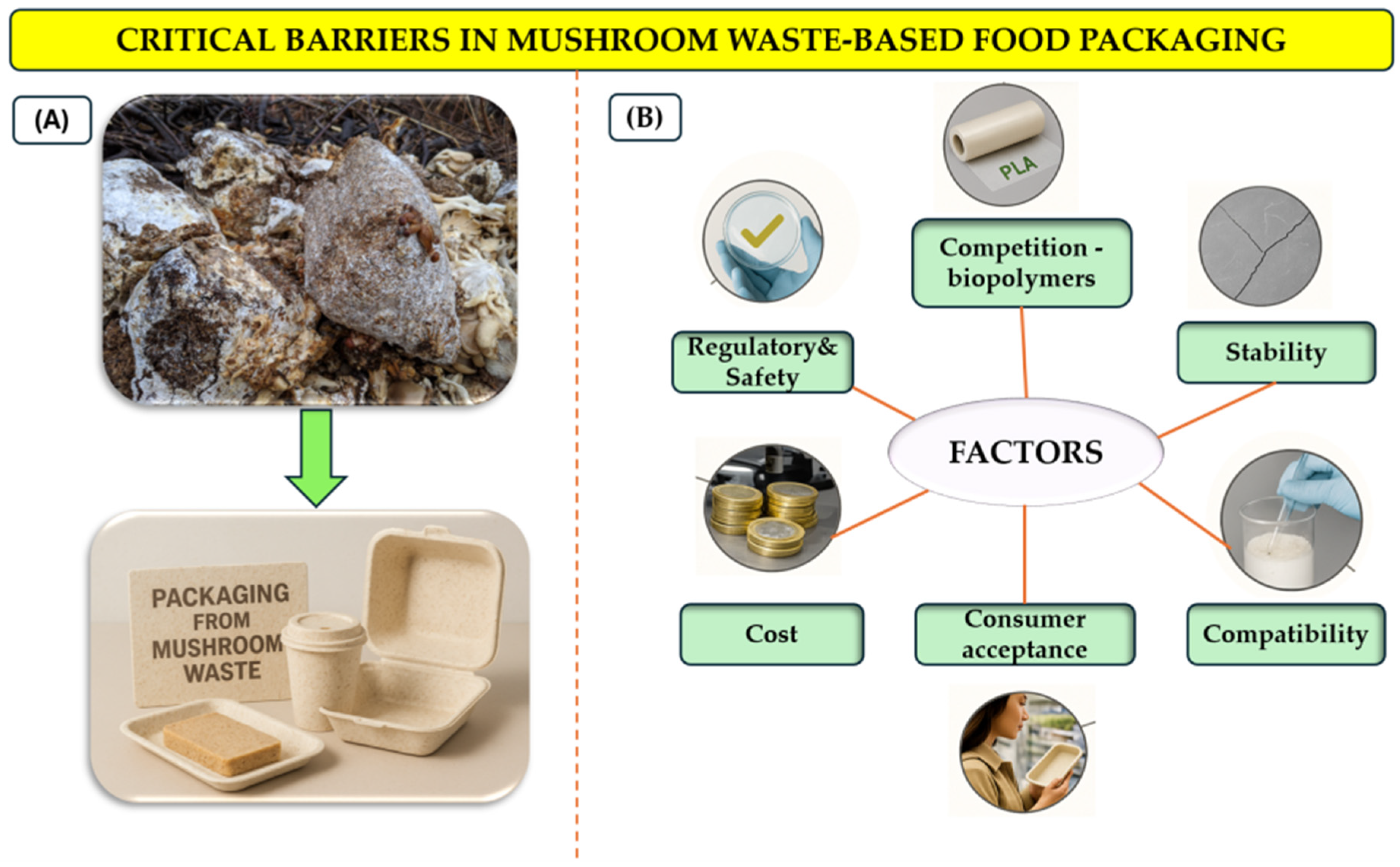

8. Challenges, Trade-Offs, and Knowledge Gaps

8.1. Technical and Stability Challenges

8.2. Regulatory and Safety Barriers

8.3. Economic Feasibility and Consumer Acceptance

- (i).

- technological innovation to enhance functionality and cost-effectiveness;

- (ii).

- infrastructure development to enable scalable, efficient processing; and

- (iii).

- regulatory support to foster market readiness and consumer acceptance [184].

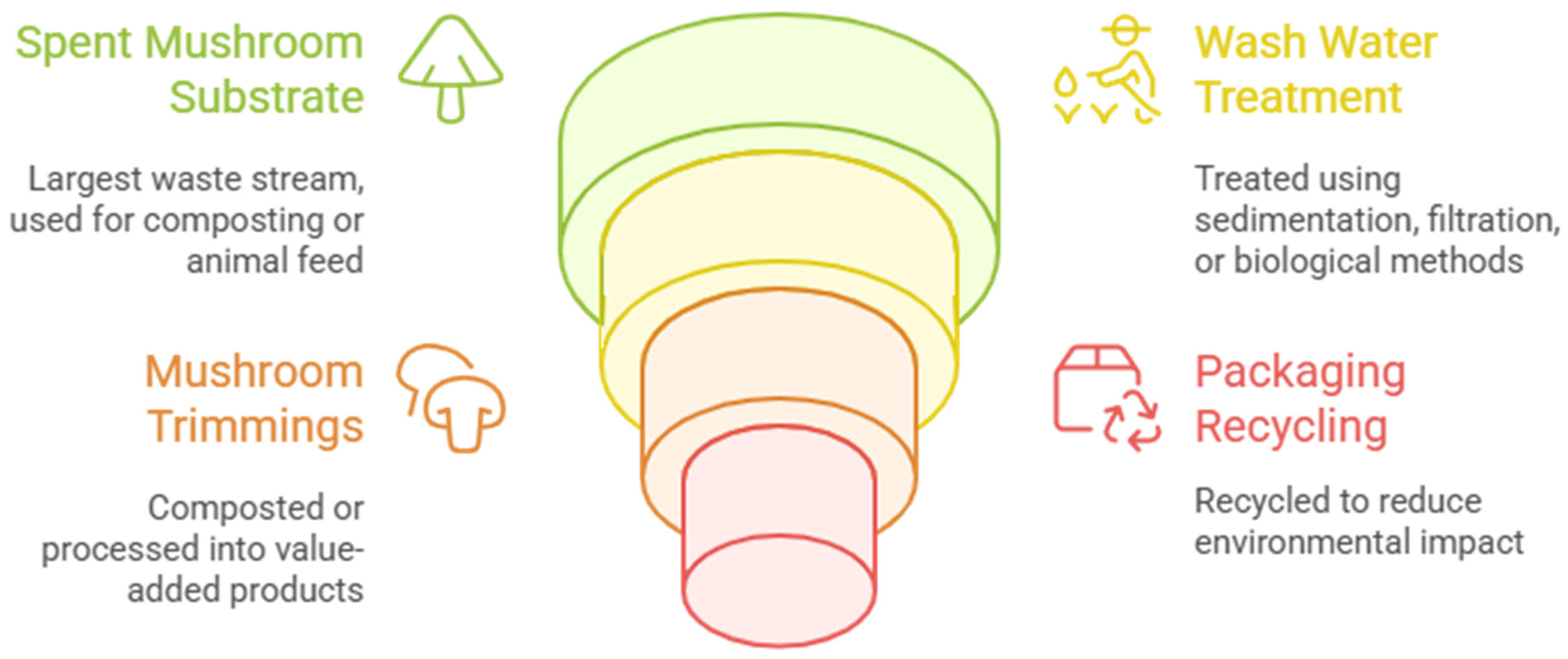

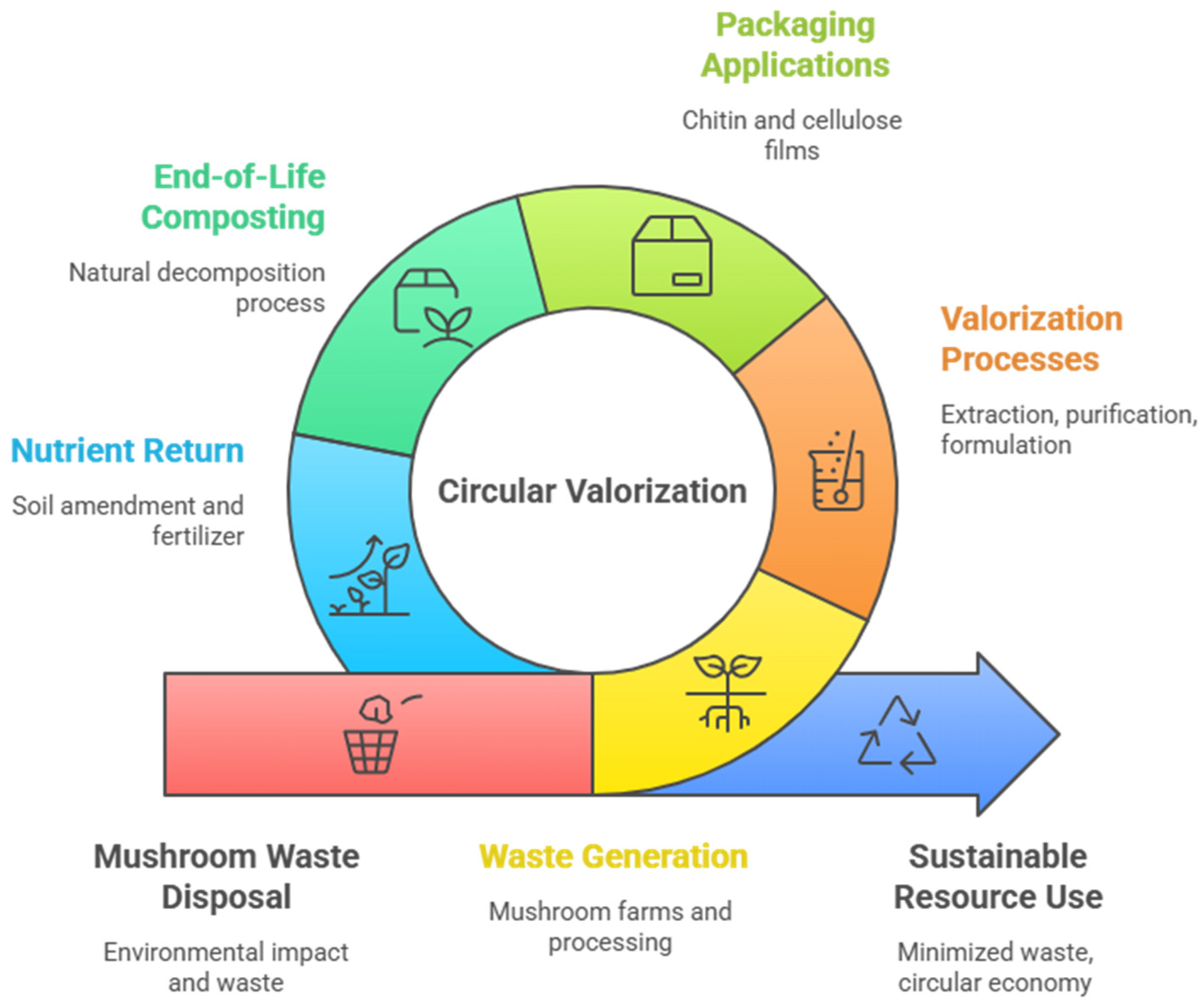

9. Sustainability, Circular Economy, and Valorization Pathways

9.1. Positioning Mushroom Residue in the Circular Bioeconomy

9.2. Cascading Valorization Strategies

9.3. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Environmental Footprint

9.4. Industrial Symbiosis and Cross-Sector Integration

9.5. Economic and Social Dimensions

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferreira-Filipe, D.A.; Paço, A.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T.; Patrício Silva, A.L. Are Biobased Plastics Green Alternatives?—A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselló-Soto, E.; Parniakov, O.; Deng, Q.; Patras, A.; Koubaa, M.; Grimi, N.; Boussetta, N.; Tiwari, B.K.; Vorobiev, E.; Lebovka, N.; et al. Application of Non-Conventional Extraction Methods: Toward a Sustainable and Green Production of Valuable Compounds from Mushrooms. Food Eng. Rev. 2016, 8, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syberg, K.; Khan, F.R.; Selck, H.; Palmqvist, A.; Banta, G.T.; Daley, J.; Sano, L.; Duhaime, M.B. Microplastics: Addressing Ecological Risk through Lessons Learned. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2015, 34, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilucia, F.; Lacivita, V.; Conte, A.; Del Nobile, M.A. Sustainable Use of Fruit and Vegetable By-Products to Enhance Food Packaging Performance. Foods 2020, 9, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socas-Rodríguez, B.; Álvarez-Rivera, G.; Valdés, A.; Ibáñez, E.; Cifuentes, A. Food By-Products and Food Wastes: Are They Safe Enough for Their Valorization? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 114, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.; McCabe, B.; Jensen, P.D.; Speight, R.; Harrison, M.; Van Den Berg, L.; O’Hara, I. Wastes to Profit: A Circular Economy Approach to Value-Addition in Livestock Industries. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2021, 61, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, M.; Attard, E.; Lyng, K.; Raclavska, H.; Singh, B.; Tesfamariam, E.; Vandenbulcke, F. (Eds.) Biodegradable Waste Management in the Circular Economy: Challenges and Opportunities, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-119-67984-4. [Google Scholar]

- Selvam, T.; Rahman, N.M.M.A.; Olivito, F.; Ilham, Z.; Ahmad, R.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I. Agricultural Waste-Derived Biopolymers for Sustainable Food Packaging: Challenges and Future Prospects. Polymers 2025, 17, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumla, J.; Suwannarach, N.; Sujarit, K.; Penkhrue, W.; Kakumyan, P.; Jatuwong, K.; Vadthanarat, S.; Lumyong, S. Cultivation of Mushrooms and Their Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Production Through the Utilization of Agro-Industrial Waste. Molecules 2020, 25, 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, F.; Almeida, M.; Paié-Ribeiro, J.; Barros, A.N.; Rodrigues, M. Unlocking the Potential of Spent Mushroom Substrate (SMS) for Enhanced Agricultural Sustainability: From Environmental Benefits to Poultry Nutrition. Life 2023, 13, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, L.; Rosenstock Völtz, L.; Gehrmann, T.; Antonopoulou, I.; Cristescu, C.; Xiong, S.; Dixit, P.; Martín, C.; Sundman, O.; Oksman, K. The Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate as Biologically Pretreated Wood and Its Fibrillation. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törős, G.; El-Ramady, H.; Béni, Á.; Peles, F.; Gulyás, G.; Czeglédi, L.; Rai, M.; Prokisch, J. Pleurotus ostreatus Mushroom: A Promising Feed Supplement in Poultry Farming. Agriculture 2024, 14, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbeye, M.J.; Salem, A.Z.M.; Reddy, P.R.K.; Elghandour, M.M.M.; Oyebamiji, K.J. Residue Recycling for the Eco-Friendly Input Use Efficiency in Agriculture and Livestock Feeding. In Resources Use Efficiency in Agriculture; Kumar, S., Meena, R.S., Jhariya, M.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–45. ISBN 978-981-15-6952-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tör\Hos, G.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J.; Velasco, F.; Llanaj, X.; Nguyen, D.H.; Peles, F. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota with Prebiotics and Antimicrobial Agents from Pleurotus Ostreatus Mushroom. Foods 2023, 12, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerletti, C.; Esposito, S.; Iacoviello, L. Edible Mushrooms and Beta-Glucans: Impact on Human Health. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, J.; Hlushko, H.; Abbott, A.; Aliakseyeu, A.; Hlushko, R.; Sukhishvili, S.A. Integrating Antioxidant Functionality into Polymer Materials: Fundamentals, Strategies, and Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 41372–41395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Yadav, R.; Erfani, H.; Jabin, S.; Jadoun, S. Revisiting the Modern Approach to Manage Agricultural Solid Waste: An Innovative Solution. Env. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 16337–16361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, I.M.; Mat Taher, Z.; Rahmat, Z.; Chua, L.S. A Review of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Plant Bioactive Compounds: Phenolics, Flavonoids, Thymols, Saponins and Proteins. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Salazar, H.; Camacho-Díaz, B.H.; Ocampo, M.L.A.; Jiménez-Aparicio, A.R. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Functional Compounds from Plants: A Review. BioResources 2023, 18, 6614–6638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royse, D.J.; Baars, J.; Tan, Q. Current Overview of Mushroom Production in the World. In Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms; Diego, C.Z., Pardo-Giménez, A., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 5–13. ISBN 978-1-119-14941-5. [Google Scholar]

- Vinci, G.; Prencipe, S.A.; Pucinischi, L.; Perrotta, F.; Ruggeri, M. Sustainability Assessment of Waste and Wastewater Recovery for Edible Mushroom Production through an Integrated Nexus. A Case Study in Lazio. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, C.; Zervakis, G.I.; Xiong, S.; Koutrotsios, G.; Strætkvern, K.O. Spent Substrate from Mushroom Cultivation: Exploitation Potential toward Various Applications and Value-Added Products. Bioengineered 2023, 14, 2252138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilakis, G.; Rigos, E.-M.; Giannakis, N.; Diamantopoulou, P.; Papanikolaou, S. Spent Mushroom Substrate Hydrolysis and Utilization as Potential Alternative Feedstock for Anaerobic Co-Digestion. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, Y.K.; Ma, T.-W.; Chang, J.-S.; Yang, F.-C. Recent Advances and Future Directions on the Valorization of Spent Mushroom Substrate (SMS): A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakar, S.; Sutaoney, P.; Singh, P.; Shah, K.; Chauhan, N.S. Systems Biology for Mushroom Cultivation Promoting Quality Life. Circ. Agric. Syst. 2025, 5, e010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijla, S.; Sharma, V.P. Status of Mushroom Production: Global and National Scenario. Mushroom Res. 2023, 32, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannaa, M.; Mansour, A.; Park, I.; Lee, D.-W.; Seo, Y.-S. Insect-Based Agri-Food Waste Valorization: Agricultural Applications and Roles of Insect Gut Microbiota. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2024, 17, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, M.; Fang, Z. Valorization of Mushroom By-products: A Review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 5593–5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Sharma, M.; Ji, D.; Xu, M.; Agyei, D. Structural Features, Modification, and Functionalities of Beta-Glucan. Fibers 2019, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulaka, A.; Christodoulou, P.; Vlassopoulou, M.; Koutrotsios, G.; Bekiaris, G.; Zervakis, G.I.; Mitsou, E.K.; Saxami, G.; Kyriacou, A.; Zervou, M.; et al. Genoprotective Properties and Metabolites of β-Glucan-Rich Edible Mushrooms Following Their In Vitro Fermentation by Human Faecal Microbiota. Molecules 2020, 25, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, G.Q.; Abdulhadi, S.Y. Molecular Characterization of Wild Pleurotus ostreatus (MW457626) and Evaluation of β-Glucans Polysaccharide Activities. Karbala Int. J. Mod. Sci. 2022, 8, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xue, C.; Mao, X. Chitosan: Structural Modification, Biological Activity and Application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 4532–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Prashanth, K.V.H.; Negi, P.S. Low Molecular Weight Chitosan from Pleurotus ostreatus Waste and Its Prebiotic Potential. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, M.; Lazic, V.; Kozarski, M. Mushroom Chitosan: A Promising Biopolymer in the Food Industry and Agriculture. Hrana I Ishr. 2023, 64, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayar-Sümer, E.N.; Verheust, Y.; Özçelik, B.; Raes, K. Impact of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermentation Based on Biotransformation of Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Mushrooms. Foods 2024, 13, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbiai, E.H.; Maouni, A.; Pinto Da Silva, L.; Saidi, R.; Legssyer, M.; Lamrani, Z.; Esteves Da Silva, J.C.G. Antioxidant Properties, Bioactive Compounds Contents, and Chemical Characterization of Two Wild Edible Mushroom Species from Morocco: Paralepista flaccida (Sowerby) Vizzini and Lepista nuda (Bull.) Cooke. Molecules 2023, 28, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, N.; Clemente, A.; Pedone, P.V.; Ragucci, S.; Di Maro, A. An Updated Review of Bioactive Peptides from Mushrooms in a Well-Defined Molecular Weight Range. Toxins 2022, 14, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, L.D.H.A. Comparative Study between Mini Open and All Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Full Thickness Tear Repair in Iraqi Patients. Tex. J. Med Sci. 2023, 23, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essig, A.; Hofmann, D.; Münch, D.; Gayathri, S.; Künzler, M.; Kallio, P.T.; Sahl, H.-G.; Wider, G.; Schneider, T.; Aebi, M. Copsin, a Novel Peptide-Based Fungal Antibiotic Interfering with the Peptidoglycan Synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 34953–34964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez De La Lastra, J.M.; González-Acosta, S.; Otazo-Pérez, A.; Asensio-Calavia, P.; Rodríguez-Borges, V.M. Antimicrobial Peptides for Food Protection: Leveraging Edible Mushrooms and Nano-Innovation. Dietetics 2025, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleackley, M.R.; Dawson, C.S.; Payne, J.A.E.; Harvey, P.J.; Rosengren, K.J.; Quimbar, P.; Garcia-Ceron, D.; Lowe, R.; Bulone, V.; van der Weerden, N.L.; et al. The Interaction with Fungal Cell Wall Polysaccharides Determines the Salt Tolerance of Antifungal Plant Defensins. Cell Surf. 2019, 5, 100026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, J.; Farkaš, V.; Sanz, A.B.; Cabib, E. ‘Strengthening the Fungal Cell Wall through Chitin-Glucan Cross-Links: Effects on Morphogenesis and Cell Integrity’: Fungal Chitin-Glucan Transglycosylases. Cell. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1239–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, A.Y.; Fayez, S.; Xiao, H.; Xu, B. New Insights into Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Effects of Edible Mushrooms. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 111982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobori, M.; Yoshida, M.; Ohnishi-Kameyama, M.; Shinmoto, H. Ergosterol Peroxide from an Edible Mushroom Suppresses Inflammatory Responses in RAW264.7 Macrophages and Growth of HT29 Colon Adenocarcinoma Cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 150, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liufang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Qu, H.; Yang, H. Recent Advances in the Application of Natural Products for Postharvest Edible Mushroom Quality Preservation. Foods 2024, 13, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanula, M.; Pogorzelska-Nowicka, E.; Pogorzelski, G.; Szpicer, A.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Wierzbicka, A.; Półtorak, A. Active Packaging of Button Mushrooms with Zeolite and Açai Extract as an Innovative Method of Extending Its Shelf Life. Agriculture 2021, 11, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, B.A.; Pathania, S.; Wilson, J.; Duffy, B.; Frias, J.M.C. Extraction, Quantification, Characterization, and Application in Food Packaging of Chitin and Chitosan from Mushrooms: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 237, 124195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Yadav, S.K.; Saneja, A. Development of a Multifunctional and Sustainable Pterostilbene Nanoemulsion Incorporated Chitosan-Alginate Food Packaging Film for Shiitake Mushroom Preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 293, 139241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, A.; Berglund, L.; Rosenstock Völtz, L.; Swamy, R.; Antonopoulou, I.; Xiong, S.; Mouzon, J.; Bismarck, A.; Oksman, K. Fungal Innovation: Harnessing Mushrooms for Production of Sustainable Functional Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2412753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Bin Nabi, H.; Mia, S.; Ahmad, I.; Zzaman, W. Valorization of Plant-Based Agro-Waste into Sustainable Food Packaging Materials: Current Approaches and Functional Applications. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Jiménez, A.; Peltzer, M.; Garrigós, M.C. Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity Studies of Polypropylene Films with Carvacrol and Thymol for Active Packaging. J. Food Eng. 2012, 109, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P.C.K. The Nutritional and Health Benefits of Mushrooms. Nutr. Bull. 2010, 35, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasser, S.P. Medicinal Mushrooms as a Source of Antitumor and Immunomodulating Polysaccharides. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 60, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M. Chitin and Chitosan: Properties and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, F.S.; Martins, A.; Vasconcelos, M.H.; Morales, P.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Functional Foods Based on Extracts or Compounds Derived from Mushrooms. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 66, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.-Y.; Sin, L.T.; Tee, T.-T.; Bee, S.-T.; Rahmat, A.R.; Rahman, W.A.W.A.; Tan, A.-C.; Vikhraman, M. Antimicrobial Agents for Food Packaging Applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 33, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Dhiman, R.; Rokana, N.; Panwar, H. Nanotechnology: An Untapped Resource for Food Packaging. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Valdés, A.; Beltrán, A.; Garrigós, M. Gelatin-Based Films and Coatings for Food Packaging Applications. Coatings 2016, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, L.; Cruz, T.; Baptista, P.; Estevinho, L.M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Wild and Commercial Mushrooms as Source of Nutrients and Nutraceuticals. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 2742–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cui, S.W.; Cheung, P.C.K.; Wang, Q. Antitumor Polysaccharides from Mushrooms: A Review on Their Isolation Process, Structural Characteristics and Antitumor Activity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 18, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Mahmood, F.; Khalil, S.A.; Zamir, R.; Fazal, H.; Abbasi, B.H. Antioxidant Activity via DPPH, Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Antimicrobial Potential in Edible Mushrooms. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2014, 30, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradali, M.-F.; Mostafavi, H.; Ghods, S.; Hedjaroude, G.-A. Immunomodulating and Anticancer Agents in the Realm of Macromycetes Fungi (Macrofungi). Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007, 7, 701–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Castiblanco, T.; Mejía-Giraldo, J.C.; Puertas-Mejía, M.Á. Lentinula Edodes, a Novel Source of Polysaccharides with Antioxidant Power. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraglia, T.; Latronico, T.; Fanigliulo, A.; Crescenzi, A.; Liuzzi, G.M.; Rossano, R. Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides from the Edible Mushroom Pleurotus eryngii. Molecules 2023, 28, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Seviour, R. Medicinal Importance of Fungal β-(1→3), (1→6)-Glucans. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, R.S. Evaluation of the Biological Activities of β-Glucan Isolated from Lentinula Edodes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 75, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, M.; Vetvicka, V. β -Glucans, History, and the Present: Immunomodulatory Aspects and Mechanisms of Action. J. Immunotoxicol. 2008, 5, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.; Barros, L.; Abreu, R. Antioxidants in Wild Mushrooms. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1543–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Tiwari, S. Facile Approach to Synthesize Chitosan-Based Composite—Characterization and Cadmium(II) Ion Adsorption Studies. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 134, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, I.; Lozano, M.; Moro, C.; D’Arrigo, M.; Rostagno, M.A.; Martínez, J.A.; García-Lafuente, A.; Guillamón, E.; Villares, A. Antioxidant Properties of Phenolic Compounds Occurring in Edible Mushrooms. Food Chem. 2011, 128, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.J.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R.; Froufe, H.J.C.; Abreu, R.M.V.; Martins, A.; Pintado, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Phenolic Compounds Identified in Wild Mushrooms, SAR Analysis and Docking Studies. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 115, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tang, W.; Dai, X.; Gao, H.; Chen, G.; Ye, J.; Chan, E.; Koh, H.L.; Li, X.; Zhou, S. Effects of Water-Soluble Ganoderma lucidum Polysaccharides on the Immune Functions of Patients with Advanced Lung Cancer. J. Med. Food 2005, 8, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Chen, X.G.; Xing, K.; Park, H.J. Antimicrobial Properties of Chitosan and Mode of Action: A State of the Art Review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khubiev, O.M.; Egorov, A.R.; Lobanov, N.N.; Fortalnova, E.A.; Kirichuk, A.A.; Tskhovrebov, A.G.; Kritchenkov, A.S. Novel Highly Efficient Antibacterial Chitosan-Based Films. BioTech 2023, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabea, E.I.; Badawy, M.E.-T.; Stevens, C.V.; Smagghe, G.; Steurbaut, W. Chitosan as Antimicrobial Agent: Applications and Mode of Action. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajrami, D.; Fischer, S.; Barth, H.; Hossain, S.I.; Cioffi, N.; Mizaikoff, B. Antimicrobial Efficiency of Chitosan and Its Methylated Derivative against Lentilactobacillus parabuchneri Biofilms. Molecules 2022, 27, 8647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, R.; Ibrahim, S.A. Natural Products as Antimicrobial Agents. Food Control 2014, 46, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S. Phenolic Compounds in Active Packaging and Edible Films/Coatings: Natural Bioactive Molecules and Novel Packaging Ingredients. Molecules 2022, 27, 7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilleri, E.; Blundell, R.; Karpiński, T.M.; Panda, J.; Nath, P.C.; Mohanta, Y.K.; Aruci, E.; Atrooz, O.M. The Therapeutic Potential of Shiitake Mushrooms (Lentinula edodes). Next Res. 2025, 2, 100632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazzaro, F.; Orlando, P.; Fratianni, F.; Coppola, R. Microencapsulation in Food Science and Biotechnology. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Qiu, H.; Ismail, B.B.; He, Q.; Yang, Z.; Zou, Z.; Xiao, G.; Xu, Y.; Ye, X.; Liu, D.; et al. Ultrasonically Functionalized Chitosan-Gallic Acid Films Inactivate Staphylococcus aureus through Envelope-Disruption under UVA Light Exposure. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 255, 128217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Tao, N.; Li, L.; Zhu, W.; Xu, C.; Deng, S.; Wang, Y. Mechanism of Antimicrobials Immobilized on Packaging Film Inhabiting Foodborne Pathogens. LWT 2022, 169, 114037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.A.; Gerschenson, L.N.; Flores, S.K. Development of Edible Films and Coatings with Antimicrobial Activity. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011, 4, 849–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M.A.; Ferrer, A.; Tyagi, P.; Yin, Y.; Salas, C.; Pal, L.; Rojas, O.J. Nanocellulose in Thin Films, Coatings, and Plies for Packaging Applications: A Review. BioResources 2017, 12, 2143–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.C.; Leite, J.C.; Brandão, G.C.; Ferreira, S.L.C.; Dos Santos, W.N.L. A Method Based on Digital Image Colorimetry for Determination of Total Phenolic Content in Fruits. Food Anal. Methods 2023, 16, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennaro, M.; Büyüktaş, D.; Carullo, D.; Pinto, A.; Dallavalle, S.; Farris, S. UV-Shielding Biopolymer Coatings Loaded with Bioactive Compounds for Food Packaging Applications. Coatings 2025, 15, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.K.; Tripathi, S.; Mehrotra, G.K.; Dutta, J. Perspectives for Chitosan Based Antimicrobial Films in Food Applications. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalluzzi, M.; Lamonaca, A.; Rotondo, N.; Miniero, D.; Muraglia, M.; Gabriele, P.; Corbo, F.; De Palma, A.; Budriesi, R.; De Angelis, E.; et al. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Lentil Wastes: Antioxidant Activity Evaluation and Metabolomic Characterization. Molecules 2022, 27, 7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, J.-W.; Hong, S.-I.; Park, H.-M.; Ng, P.K.W. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan-Based Nanocomposite Films with Antimicrobial Activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5814–5822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.G.; Martins, V.G. Multifunctional Alginate Films Blended with Polyphenol-Rich Extract from Unconventional Edible Sources: Bioactive Properties, UV-Light Protection, and Food Freshness Monitoring. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coma, V. Bioactive Packaging Technologies for Extended Shelf Life of Meat-Based Products. Meat Sci. 2008, 78, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T.T.; Nguyen, L.A.T.; Dau, D.T.; Nguyen, Q.S.; Le, T.N.; Nguyen, T.Q.N. Improving Properties of Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol Films Using Cashew Nut Testa Extract: Potential Applications in Food Packaging. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 241236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppakul, P.; Miltz, J.; Sonneveld, K.; Bigger, S.W. Active Packaging Technologies with an Emphasis on Antimicrobial Packaging and Its Applications. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbettaïeb, N.; Debeaufort, F.; Karbowiak, T. Bioactive Edible Films for Food Applications: Mechanisms of Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 3431–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-de-Dicastillo, C.; Gómez-Estaca, J.; Catalá, R.; Gavara, R.; Hernández-Muñoz, P. Active Antioxidant Packaging Films: Development and Effect on Lipid Stability of Brined Sardines. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 1376–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, C.; Kurek, M.; Hayouka, Z.; Röcker, B.; Yildirim, S.; Antunes, M.D.C.; Nilsen-Nygaard, J.; Pettersen, M.K.; Freire, C.S.R. A Concise Guide to Active Agents for Active Food Packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 80, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, C.E.; Marcos, B. Active and Intelligent Packaging Systems for a Modern Society. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoni, C.G.; Espitia, P.J.P.; Avena-Bustillos, R.J.; McHugh, T.H. Trends in Antimicrobial Food Packaging Systems: Emitting Sachets and Absorbent Pads. Food Res. Int. 2016, 83, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastarrachea, L.; Dhawan, S.; Sablani, S.S. Engineering Properties of Polymeric-Based Antimicrobial Films for Food Packaging: A Review. Food Eng. Rev. 2011, 3, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, R.; Atarés, L.; Chiralt, A. Biodegradable Active Materials Containing Phenolic Acids for Food Packaging Applications. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2022, 21, 3910–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, P.R.; López-Caballero, M.E.; Gómez-Guillén, M.C.; Mauri, A.N.; Montero, M.P. Sunflower Protein Films Incorporated with Clove Essential Oil Have Potential Application for the Preservation of Fish Patties. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 33, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, S.; Villalobos-Carvajal, R.; Reyes-Parra, J.E. Physical, Mechanical and Antibacterial Properties of Alginate Film: Effect of the Crosslinking Degree and Oregano Essential Oil Concentration. J. Food Eng. 2012, 110, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouki, M.; Yazdi, F.T.; Mortazavi, S.A.; Koocheki, A. Quince Seed Mucilage Films Incorporated with Oregano Essential Oil: Physical, Thermal, Barrier, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 36, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González, L.; Vargas, M.; González-Martínez, C.; Chiralt, A.; Cháfer, M. Use of Essential Oils in Bioactive Edible Coatings: A Review. Food Eng. Rev. 2011, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atarés, L.; Chiralt, A. Essential Oils as Additives in Biodegradable Films and Coatings for Active Food Packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 48, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, C.; Ramos, C.; Teixeira, G.; Batista, I.; Mendes, R.; Nunes, L.; Marques, A. Characterization of Biodegradable Films Prepared with Hake Proteins and Thyme Oil. J. Food Eng. 2011, 105, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, D.S.; Chinnan, M.S. Biopolymer-Based Antimicrobial Packaging: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 44, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagri, A.; Ustunol, Z.; Ryser, E.T. Antimicrobial Edible Films and Coatings. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.A.; Cusumano, G.; Venanzoni, R.; Angelini, P. The Glucans Mushrooms: Molecules of Significant Biological and Medicinal Value. Polysaccharides 2024, 5, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Teng, X.; Li, G.; Rhim, J.-W. Preparation, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Activity of Gelatin/ZnO Nanocomposite Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 45, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leceta, I.; Guerrero, P.; Ibarburu, I.; Dueñas, M.T.; De La Caba, K. Characterization and Antimicrobial Analysis of Chitosan-Based Films. J. Food Eng. 2013, 116, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.H.; Razavi, S.H.; Mousavi, M.A. Antimicrobial, Physical and Mechanical Properties of Chitosan-Based Films Incorporated with Thyme, Clove and Cinnamon Essential Oils. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2009, 33, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Viuda-Martos, M.; Sendra, E.; Perez-Alvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. In Vitro Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties of Chitosan Edible Films Incorporated with Thymus moroderi or Thymus piperella Essential Oils. Food Control 2013, 30, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Bhardwaj, K.; Kuča, K.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Verma, R.; Machado, M.; Kumar, D.; Cruz-Martins, N. Edible Mushrooms’ Enrichment in Food and Feed: A Mini Review. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2022, 57, 1386–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranoto, Y.; Salokhe, V.M.; Rakshit, S.K. Physical and Antibacterial Properties of Alginate-Based Edible Film Incorporated with Garlic Oil. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, M.P.; Gómez-Estaca, J.; Gavara, R.; Hernandez-Munoz, P. Biochemical Properties of Bioplastics Made from Wheat Gliadins Cross-Linked with Cinnamaldehyde. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 13212–13220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Decker, E.A.; Goddard, J.M. Controlling Lipid Oxidation of Food by Active Packaging Technologies. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour-Gilandeh, Y.; Kaveh, M.; Fatemi, H.; Aziz, M. Combined Hot Air, Microwave, and Infrared Drying of Hawthorn Fruit: Effects of Ultrasonic Pretreatment on Drying Time, Energy, Qualitative, and Bioactive Compounds’ Properties. Foods 2021, 10, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Malakar, S.; Rao, M.V.; Kumar, N.; Sahu, J.K. Recent Advancement in Ultrasound-Assisted Novel Technologies for the Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Herbal Plants: A Review. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 1763–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyyedi-Mansour, S.; Donn, P.; Carpena, M.; Chamorro, F.; Barciela, P.; Perez-Vazquez, A.; Jorge, A.O.S.; Prieto, M.A. Utilization of Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction for Bioactive Compounds from Floral Sources. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2024, 40, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Pang, S.; Zhong, M.; Sun, Y.; Qayum, A.; Liu, Y.; Rashid, A.; Xu, B.; Liang, Q.; Ma, H.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Ultrasonic Assisted Extraction (UAE) for Bioactive Components: Principles, Advantages, Equipment, and Combined Technologies. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 101, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagade, S.B.; Patil, M. Recent Advances in Microwave Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Complex Herbal Samples: A Review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2021, 51, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laina, K.T.; Drosou, C.; Stergiopoulos, C.; Eleni, P.M.; Krokida, M. Optimization of Combined Ultrasound and Microwave-Assisted Extraction for Enhanced Bioactive Compounds Recovery from Four Medicinal Plants: Oregano, Rosemary, Hypericum, and Chamomile. Molecules 2024, 29, 5773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira-Casais, A.; Otero, P.; Garcia-Perez, P.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Pereira, A.G.; Carpena, M.; Soria-Lopez, A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Benefits and Drawbacks of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for the Recovery of Bioactive Compounds from Marine Algae. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaño-González, M.J.; Barea-Sepúlveda, M.; Espada-Bellido, E.; Ferreiro-González, M.; López-Castillo, J.G.; Palma, M.; Barbero, G.F.; Carrera, C. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Total Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity in Mushrooms. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazzotta, S.; Manzocco, L. Effect of Ultrasounds and High Pressure Homogenization on the Extraction of Antioxidant Polyphenols from Lettuce Waste. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 50, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melikoglu, M. Microwave-Assisted Extraction: Recent Advances in Optimization, Synergistic Approaches, and Applications for Green Chemistry. Sustain. Chem. Clim. Action 2025, 7, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.C.J.; Nillian, E. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Sarawak Liberica Sp. Coffee Pulp: Statistical Optimization and Comparison with Conventional Methods. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5364–5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afonso, T.B.; Marçal, S.; Vale, P.; Sousa, A.S.; Nunes, J.; Pintado, M. Exploring the Bioactive Potential of Mushroom Aqueous Extracts: Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Prebiotic Properties. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parí, S.M.; Saldaña, E.; Rios-Mera, J.D.; Quispe Angulo, M.F.; Huaman-Castilla, N.L. Emerging Technologies for Extracting Antioxidant Compounds from Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms: An Efficient and Sustainable Approach. Compounds 2025, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M. Towards Green Extraction of Bioactive Natural Compounds. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 2039–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, J.; Bhardwaj, N. Development of Bio-Based Polymeric Blends—A Comprehensive Review. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2025, 36, 102–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuntia, A.; Prasanna, N.S.; Mitra, J. Technologies for Biopolymer-Based Films and Coatings. In Biopolymer-Based Food Packaging; Kumar, S., Mukherjee, A., Dutta, J., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 66–109. ISBN 978-1-119-70225-2. [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, C.J.; Genzer, J. Applications of Surface-Grafted Macromolecules Derived from Post-Polymerization Modification Reactions. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 871–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Sit, N. A Comprehensive Review on Types and Properties of Biopolymers as Sustainable Bio-based Alternatives for Packaging. Food Biomacromol. 2024, 1, 58–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigante, V.; Panariello, L.; Coltelli, M.-B.; Danti, S.; Obisesan, K.A.; Hadrich, A.; Staebler, A.; Chierici, S.; Canesi, I.; Lazzeri, A.; et al. Liquid and Solid Functional Bio-Based Coatings. Polymers 2021, 13, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trodtfeld, F.; Tölke, T.; Wiegand, C. Developing a Prolamin-Based Gel for Food Packaging: In-Vitro Assessment of Cytocompatibility. Gels 2023, 9, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer, A.; Kopacic, S.; Bauer, W. Extensive Characterization of Alginate, Chitosan and Microfibrillated Cellulose Cast Films to Assess Their Suitability as Barrier Coating for Paper and Board. Polymers 2023, 15, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giotopoulou, I.; Fotiadou, R.; Stamatis, H.; Barkoula, N.-M. Development of Low-Density Polyethylene Films Coated with Phenolic Substances for Prolonged Bioactivity. Polymers 2023, 15, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah; Cai, J.; Hafeez, M.A.; Wang, Q.; Farooq, S.; Huang, Q.; Tian, W.; Xiao, J. Biopolymer-Based Functional Films for Packaging Applications: A Review. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1000116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gururani, P.; Bhatnagar, P.; Dogra, P.; Chandra Joshi, H.; Chauhan, P.K.; Vlaskin, M.S.; Chandra Joshi, N.; Kurbatova, A.; Irina, A.; Kumar, V. Bio-Based Food Packaging Materials: A Sustainable and Holistic Approach for Cleaner Environment—A Review. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 7, 100384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, D.; Keukens, B.M.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Food Packaging Technology Considerations for Designers: Attending to Food, Consumer, Manufacturer, and Environmental Issues. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2024, 23, e70058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Zubair, M.; Roopesh, M.S.; Ullah, A. An Overview of Advanced Antimicrobial Food Packaging: Emphasizing Antimicrobial Agents and Polymer-Based Films. Polymers 2024, 16, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hausner, G.; Rout, P.R.; Yuan, Q. Investigation of Fungal Mycelium-Bound Bio-Foams from Agricultural Wastes as Sustainable and Eco-Conscious Packaging Innovations. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 501, 145206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, E.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Films for Sustainable Food Packaging Based on Mushroom Waste Biomass. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 171, 111836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewan, F.; Islam, N. Pullulan-Based Films: Unveiling Its Multifaceted Versatility for Sustainability. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2024, 2024, 2633384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amobonye, A.; Lalung, J.; Awasthi, M.K.; Pillai, S. Fungal Mycelium as Leather Alternative: A Sustainable Biogenic Material for the Fashion Industry. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 38, e00724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Hao, Z.; Du, Y.; Jia, M.; Xie, S. Mechanical and Barrier Properties of Chitosan-Based Composite Film as Food Packaging: A Review. BioResources 2024, 19, 4001–4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetković, K.; Karabegović, I.; Dordevic, S.; Dordevic, D.; Danilović, B. Valorization of Food Industry Waste for Biodegradable Biopolymer-Based Packaging Films. Processes 2025, 13, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezghi Rami, M.; Forouzandehdel, S.; Aalizadeh, F. Enhancing Biodegradable Smart Food Packaging: Fungal-Synthesized Nanoparticles for Stabilizing Biopolymers. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahangiri, F.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Sustainable Biodegradable Coatings for Food Packaging: Challenges and Opportunities. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 4934–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitting, S.; Derme, T.; Lee, J.; Van Mele, T.; Dillenburger, B.; Block, P. Challenges and Opportunities in Scaling up Architectural Applications of Mycelium-Based Materials with Digital Fabrication. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, V.; Basenko, E.Y.; Benz, J.P.; Braus, G.H.; Caddick, M.X.; Csukai, M.; De Vries, R.P.; Endy, D.; Frisvad, J.C.; Gunde-Cimerman, N.; et al. Growing a Circular Economy with Fungal Biotechnology: A White Paper. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2020, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthes, A.C.; Smiderle, F.R.; Iacomini, M. Mushroom Heteropolysaccharides: A Review on Their Sources, Structure and Biological Effects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, A.V.; Sun, W.; Abitbol, T. “You Are What You Eat”: How Fungal Adaptation Can Be Leveraged toward Myco-Material Properties. Glob. Chall. 2024, 8, 2300140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsis, K.; Grasso, S.; Menon, A.; Brunton, N.P.; Lyng, J.G.; Jacquier, J.-C.; Bhuyan, D.J. Recovery of Ergosterol and Vitamin D2 from Mushroom Waste—Potential Valorization by Food and Pharmaceutical Industries. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londoño, C.R.; Gil, A.G.; Moreno, A.; Alvarado, P.N. Valorization of Spent Mushroom Compost Through a Cascading Use Approach. Energies 2024, 17, 5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.C.; Trevisan, M.G.; Garcia, J.S. β-Galactosidase Encapsulated in Carrageenan, Pectin and Carrageenan/Pectin: Comparative Study, Stability and Controlled Release. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2020, 92, e20180609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrete-Bolagay, D.; Guerrero, V.H. Opportunities and Challenges in the Application of Bioplastics: Perspectives from Formulation, Processing, and Performance. Polymers 2024, 16, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, R.; Babu, R.J.; Palakurthi, S. Nanomedicine Scale-up Technologies: Feasibilities and Challenges. AAPS PharmSciTech 2014, 15, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avila, L.B.; Schnorr, C.; Silva, L.F.O.; Morais, M.M.; Moraes, C.C.; Da Rosa, G.S.; Dotto, G.L.; Lima, É.C.; Naushad, M. Trends in Bioactive Multilayer Films: Perspectives in the Use of Polysaccharides, Proteins, and Carbohydrates with Natural Additives for Application in Food Packaging. Foods 2023, 12, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielichowski, K.; Njuguna, J.; Majka, T.M. Thermal Degradation of Polymer (Nano)Composites. In Thermal Degradation of Polymeric Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 251–286. ISBN 978-0-12-823023-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kuperkar, K.; Atanase, L.; Bahadur, A.; Crivei, I.; Bahadur, P. Degradable Polymeric Bio(Nano)Materials and Their Biomedical Applications: A Comprehensive Overview and Recent Updates. Polymers 2024, 16, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băbuțan, M.; Botiz, I. Morphological Characteristics of Biopolymer Thin Films Swollen-Rich in Solvent Vapors. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Tam, C.C.; Chan, K.L.; Mahoney, N.; Cheng, L.W.; Friedman, M.; Land, K.M. Antimicrobial Efficacy of Edible Mushroom Extracts: Assessment of Fungal Resistance. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, A.; Radoor, S.; Siengchin, S.; Shin, G.H.; Kim, J.T. Recent Progress of Bioplastics in Their Properties, Standards, Certifications and Regulations: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 163156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamuddin, S.; Baloch, A.J.; Chen, C.; Arif, M.; Mubarak, N.M. Bio-Based Plastics, Biodegradable Plastics, and Compostable Plastics: Biodegradation Mechanism, Biodegradability Standards and Environmental Stratagem. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 195, 105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, R.; Alrashed, M.M.; Vetcher, A.A.; Kim, S.-C. Next-Generation Food Packaging: Progress and Challenges of Biopolymer-Based Materials. Polymers 2025, 17, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, A.M.N.; Avila, L.B.; Contessa, C.R.; Valério Filho, A.; de Rosa, G.S.; Moraes, C.C. Biodegradation Study of Food Packaging Materials: Assessment of the Impact of the Use of Different Biopolymers and Soil Characteristics. Polymers 2024, 16, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Barbir, J.; Venkatesan, M.; Lange Salvia, A.; Dobri, A.; Bošković, N.; Eustachio, J.H.P.P.; Ingram, I.; Dinis, M.A.P. Policy Gaps and Opportunities in Bio-Based Plastics: Implications for Sustainable Food Packaging. Foods 2025, 14, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevigné-Itoiz, E.; Mwabonje, O.; Panoutsou, C.; Woods, J. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): Informing the Development of a Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2021, 379, 20200352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, D.; Wösten, H.A.B. Mushroom Cultivation in the Circular Economy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7795–7803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Reinders, M.J.; Dagevos, H.; Partanen, A.; Meeusen, M. Consumer Perception of Bio-Based Products—An Exploratory Study in 5 European Countries. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2016, 77, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lignou, S.; Oloyede, O.O. Consumer Acceptability and Sensory Profile of Sustainable Paper-Based Packaging. Foods 2021, 10, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. A Critical Review of Consumer Perception and Environmental Impacts of Bioplastics in Sustainable Food Packaging. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtil, E. Molecular Strategies to Overcome Sensory Challenges in Alternative Protein Foods. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2025, 18, 6964–6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottet, C.; Ramirez-Tapias, Y.A.; Delgado, J.F.; De La Osa, O.; Salvay, A.G.; Peltzer, M.A. Biobased Materials from Microbial Biomass and Its Derivatives. Materials 2020, 13, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, T.C.; Nai, C.; Meyer, V. How a Fungus Shapes Biotechnology: 100 Years of Aspergillus niger Research. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2018, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderroost, M.; Ragaert, P.; Devlieghere, F.; De Meulenaer, B. Intelligent Food Packaging: The next Generation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 39, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoropoulos, A.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; McAloone, T.C. The Emergent Role of Digital Technologies in the Circular Economy: A Review. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Adrodegari, F.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Exploring How Usage-Focused Business Models Enable Circular Economy through Digital Technologies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthin, A.; Traverso, M.; Crawford, R.H. Circular Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment: An Integrated Framework. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, C.; Civit, B.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Druckman, A.; Pires, A.C.; Weidema, B.; Mieras, E.; Wang, F.; Fava, J.; Canals, L.M.I.; et al. Using Life Cycle Assessment to Achieve a Circular Economy. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in Transition? Drivers and Barriers in the Eco-Innovation Road to the Circular Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzén, S.; Sandström, G.Ö. Barriers to the Circular Economy—Integration of Perspectives and Domains. Procedia CIRP 2017, 64, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How Do Scholars Approach the Circular Economy? A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the Circular Economy: An Analysis of 114 Definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, C.-W.; Sabaratnam, V. Potential Uses of Spent Mushroom Substrate and Its Associated Lignocellulosic Enzymes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 96, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravlikovsky, A.; Pinheiro, M.N.C.; Dinca, L.; Crisan, V.; Symochko, L. Valorization of Spent Mushroom Substrate: Establishing the Foundation for Waste-Free Production. Recycling 2024, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahel, W.R. The Circular Economy. Nature 2016, 531, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneef, M.; Ceseracciu, L.; Canale, C.; Bayer, I.S.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Athanassiou, A. Advanced Materials from Fungal Mycelium: Fabrication and Tuning of Physical Properties. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houette, T.; Maurer, C.; Niewiarowski, R.; Gruber, P. Growth and Mechanical Characterization of Mycelium-Based Composites towards Future Bioremediation and Food Production in the Material Manufacturing Cycle. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appels, F.V.W.; Camere, S.; Montalti, M.; Karana, E.; Jansen, K.M.B.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Krijgsheld, P.; Wösten, H.A.B. Fabrication Factors Influencing Mechanical, Moisture- and Water-Related Properties of Mycelium-Based Composites. Mater. Des. 2019, 161, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, F. The Biorefinery Concept: Using Biomass Instead of Oil for Producing Energy and Chemicals. Energy Convers. Manag. 2010, 51, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro-Molina, B.; Lopez-Arenas, T. Design and Technical-Economic-Environmental Evaluation of a Biorefinery Using Non-Marketable Edible Mushroom Waste. Processes 2024, 12, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FitzPatrick, M.; Champagne, P.; Cunningham, M.F.; Whitney, R.A. A Biorefinery Processing Perspective: Treatment of Lignocellulosic Materials for the Production of Value-Added Products. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8915–8922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, N.K.; Vengadesan, V.; Pallam, R.B.; Sadras, S.R.; Sahadevan, R.; Sarma, V.V. A Pilot-Scale Sustainable Biorefinery, Integrating Mushroom Cultivation and in-Situ Pretreatment-Cum-Saccharification for Ethanol Production. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 53, 954–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemuri, V.S. A Commercial-Scale, Circular-Economical Bio-Refinery Model for Sustainable Yields of Mushrooms, Cellulase-Complex, Bio-Priming Agents, Bio-Ethanol, and Bio-Fertilizer. Kavaka 2023, 59, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, D.K.; Dubey, R.C.; Aeron, A.; Kumar, B.; Kumar, S.; Tewari, S.; Arora, N.K. Integrated Approach for Disease Management and Growth Enhancement of Sesamum Indicum L. Utilizing Azotobacter Chroococcum TRA2 and Chemical Fertilizer. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 28, 3015–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Yadav, A.N.; Kumar, V.; Vyas, P.; Dhaliwal, H.S. Food Waste: A Potential Bioresource for Extraction of Nutraceuticals and Bioactive Compounds. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2017, 4, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottle, T.A.; Bilec, M.M.; Landis, A.E. Sustainability Assessments of Bio-Based Polymers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 1898–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, T.Y.; Nguyen, K.L.P.; Nguyen, T.H.T.; Le, D.T.; Nguyen, M.T.; Nguyen, Q.L.; Nguyen, H.-Q.; Bui, T.-K.L. Integrated Life Cycle Assessment with the ReSOLVE Framework for Environmental Impacts Mitigation in Mushroom Growing: The Case in Lam Dong Province, Vietnam. Environ. Dev. 2024, 51, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnveden, G.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Ekvall, T.; Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Hellweg, S.; Koehler, A.; Pennington, D.; Suh, S. Recent Developments in Life Cycle Assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.R. “Uncovering” Industrial Symbiosis. J. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 11, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, W.; Chew, K.; Le, C.; Chee, C.; Ooi, M.; Show, P. Aerobic Compression Composting Technology on Raw Mushroom Waste for Bioenergy Pellets Production. Processes 2022, 10, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Harris, S. Prospecting the Sustainability Implications of an Emerging Industrial Symbiosis Network. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 138, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.; Godina, R.; Azevedo, S.G.; Matias, J.C.O. A Comprehensive Review of Industrial Symbiosis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and Its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to a Balanced Interplay of Environmental and Economic Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular Economy—From Review of Theories and Practices to Development of Implementation Tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morseletto, P. Targets for a Circular Economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomsma, F.; Brennan, G. The Emergence of Circular Economy: A New Framing Around Prolonging Resource Productivity. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilkes-Hoffman, L.; Ashworth, P.; Laycock, B.; Pratt, S.; Lant, P. Public Attitudes towards Bioplastics—Knowledge, Perception and End-of-Life Management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Typical Values (SMS Basis) | Relevance to Valorization |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture content | 60–70% (wet basis) | High water-holding capacity is ideal for composting or soil amendment; it requires drying for bioenergy use. |

| Organic matter | 40–60% dry weight (DW) | Supports biodegradation and biogas production (e.g., yields 200–300 mL/g volatile solids) |

| pH | 6.5–8.0 | Neutral to slightly alkaline conditions facilitate nutrient availability in soil amendments and microbial fermentations |

| Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) | N: ~1–2%; P: 0.3–1.0%; K: 0.5–2.0% (DW) | Nutrient-rich for fertilizer use; can improve crop performance |

| Lignocellulose (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) | Lignin fraction often > 15% | Lignin and cellulose fractions can be used for bioenergy, biochar, or material production. |

| Microbial load | 106–108 CFU/g | Contains diverse decomposers (bacteria, fungi) useful in composting, bio-augmentation, and enzyme recovery |

| Compound Class | Primary Function | Quantitative Performance | Key Mechanisms | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Antimicrobial, Barrier | 90–99% microbial reduction; 40–60% barrier improvement | Membrane disruption, Film formation | [73,74,75,76] |

| β-glucans | Antioxidant, Film-forming | IC50: 0.52–3.59 mg·mL−1; 75–88% radical scavenging | Radical scavenging, Metal chelation | [63,64,66] |

| Phenolic compounds | Antioxidant, UV protection | MIC: 7.5–15 mg·mL−1; 90% UV reduction | Electron donation, UV absorption | [78,79,86] |

| Polysaccharide fractions | Multifunctional | 82–94% antioxidant activity; Enhanced tensile properties | Multiple radical scavenging mechanisms | [94] |

| Aspect | Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) |

|---|---|---|

| Driving Principle | Acoustic cavitation (formation and collapse of microbubbles) | Dielectric heating (direct microwave energy absorption by solvents and samples) |

| Mechanism of Action | Cell disruption via fragmentation, pore formation, and sonoporation | Rapid heating of intracellular moisture, disrupting compound–matrix bonds |

| Effect on Plant Cell Walls | Damages the polysaccharide network; enhances the release of intracellular compounds. | Heat enhances the solubility and diffusion of compounds. |

| Efficiency | High mass transfer and solvent penetration; fast release | Quick and uniform heating; high extraction efficiency |

| Temperature Control | Generally moderate; no need for high temperatures | Can exceed the solvent boiling point in closed vessels without decomposition |

| Applications | Fruit, vegetable, and mushroom residues for bioactive compound recovery | Broad use for thermally stable bioactives; efficient for high-value extracts |

| Solvent Interaction | Mechanical effects enhance solvent penetration | Solvents absorb microwave energy for direct heating |

| Advantages | Eco-friendly, energy-efficient, effective at room temp, enhances yield | High-speed, energy-efficient, enhanced extraction at controlled high temps |

| References | [120,121] | [122,123] |

| Method | Description | Advantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blending | Physical mixing of a bio-based additive with the polymer matrix. The additive is mixed into the melt or solvent-blended before the film is formed. | Uniform distribution of the additive retains the base polymer structure. | [132] |

| Coating | Application of a biopolymer layer onto the surface of an existing film. Spraying or spreading a layer on the film surface. | Modifies only the surface layer; does not affect the film core. | [133] |

| Grafting | Chemical modification of polymer chains to enable bonding with the film surface. Covalent bonding through chain-end or side-chain functionalization. | Stable and durable attachment; improves interfacial properties. | [134] |

| In situ polymerization | Polymerization of bio-based molecules directly within the packaging matrix. Monomers are dispersed in the medium and polymerize in place during matrix formation. | Ensures homogeneous integration; strong interaction between the biopolymer and the matrix. | [135] |

| Application Area | Case Study/Example | Key Features | Impact/Potential | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mycelium composites | Ecovative Design packaging for electronics | Molded foam-like structures from mycelium + agri-residue | Biodegradable replacement for EPS foams | [144] |

| Mushroom leather analogs | MycoWorks, Bolt Threads | Flexible, leather-like fungal mats | Premium, sustainable alternative to leather/plastics | [147] |

| Active packaging | Oyster mushroom-based films | Antioxidant + antimicrobial activity | Shelf-life extension for fruits & vegetables | [145] |

| Edible coatings | Shiitake pullulan films | Transparent, oxygen-barrier edible films | Reduced food residue, no secondary packaging needed | [146] |

| Hybrid biopolymer systems | Chitosan-starch blends | Stronger tensile and barrier properties | Expanded functional range of biofilms | [148] |

| Challenge Category | Specific Issues | Potential Solutions | Economic Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Processing efficiency, Product standardization | Advanced extraction technologies, Quality control systems | 15–25% cost reduction |

| Economic | Scale-up costs, Market development | Regional processing hubs, Policy incentives | $2.85 M NPV over 10 years |

| Environmental | Energy consumption, Water usage | Renewable energy integration, Process optimization | 28% GHG reduction |

| Social | Consumer acceptance, Skill development | Education programs, Training initiatives | 68% consumer willingness to pay premium |

| Regulatory | Standards development, Certification | Harmonized regulations, Industry standards | Reduced compliance costs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Törős, G.; El-Ramady, H.; Abdalla, N.; Elsakhawy, T.; Prokisch, J. Valorization of Mushroom Residues for Functional Food Packaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210870

Törős G, El-Ramady H, Abdalla N, Elsakhawy T, Prokisch J. Valorization of Mushroom Residues for Functional Food Packaging. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):10870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210870

Chicago/Turabian StyleTörős, Gréta, Hassan El-Ramady, Neama Abdalla, Tamer Elsakhawy, and József Prokisch. 2025. "Valorization of Mushroom Residues for Functional Food Packaging" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 10870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210870

APA StyleTörős, G., El-Ramady, H., Abdalla, N., Elsakhawy, T., & Prokisch, J. (2025). Valorization of Mushroom Residues for Functional Food Packaging. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 10870. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210870