Allogeneic Umbilical Cord Blood Serum Eyedrops for the Treatment of Severe Dry Eye Disease Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Treatments and Unmet Needs

1.2. Blood-Derived Therapies and the Role of UCBS

1.3. Purpose of the Study

2. Results

2.1. Patient Population and Baseline Characteristics

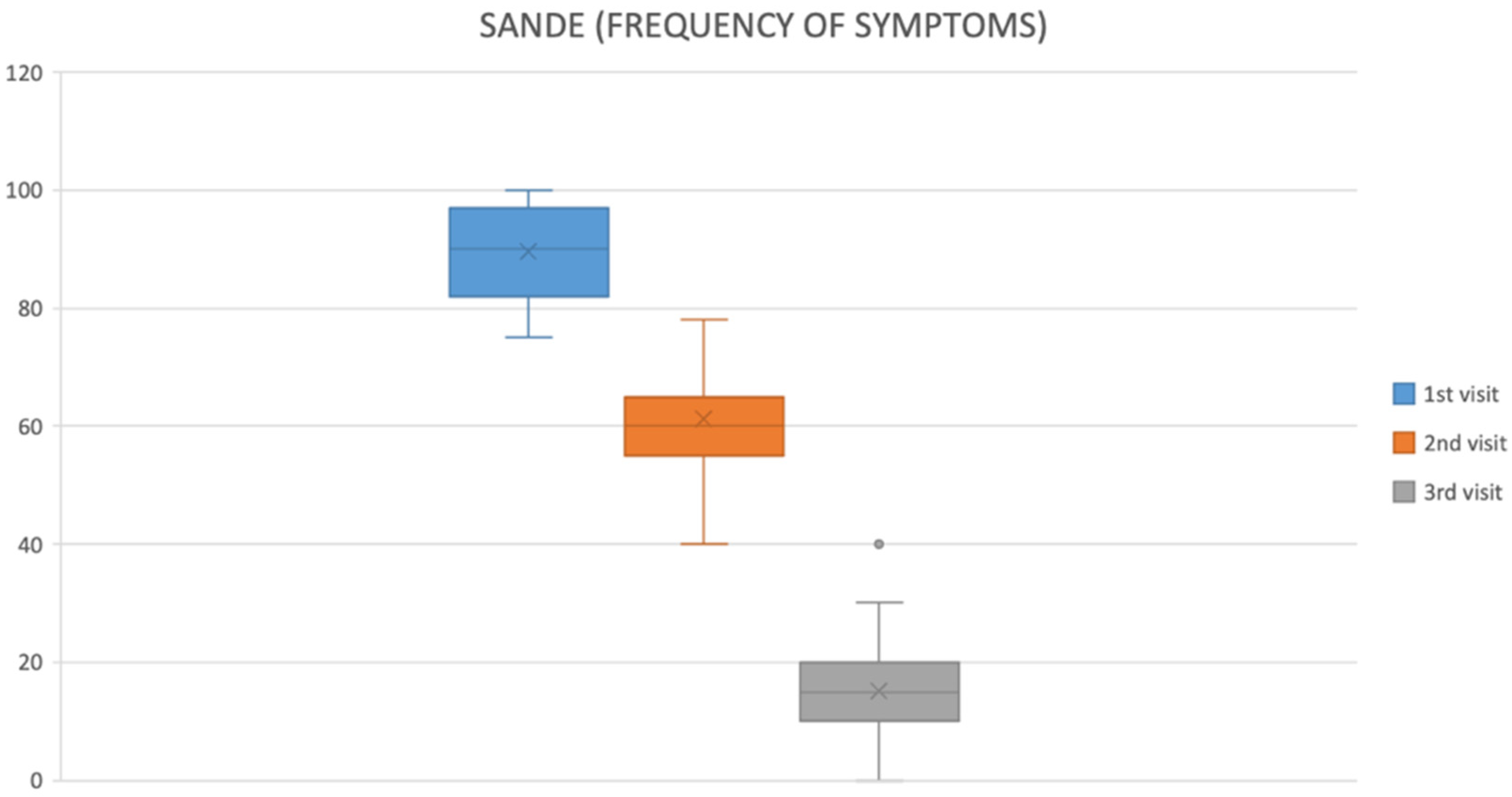

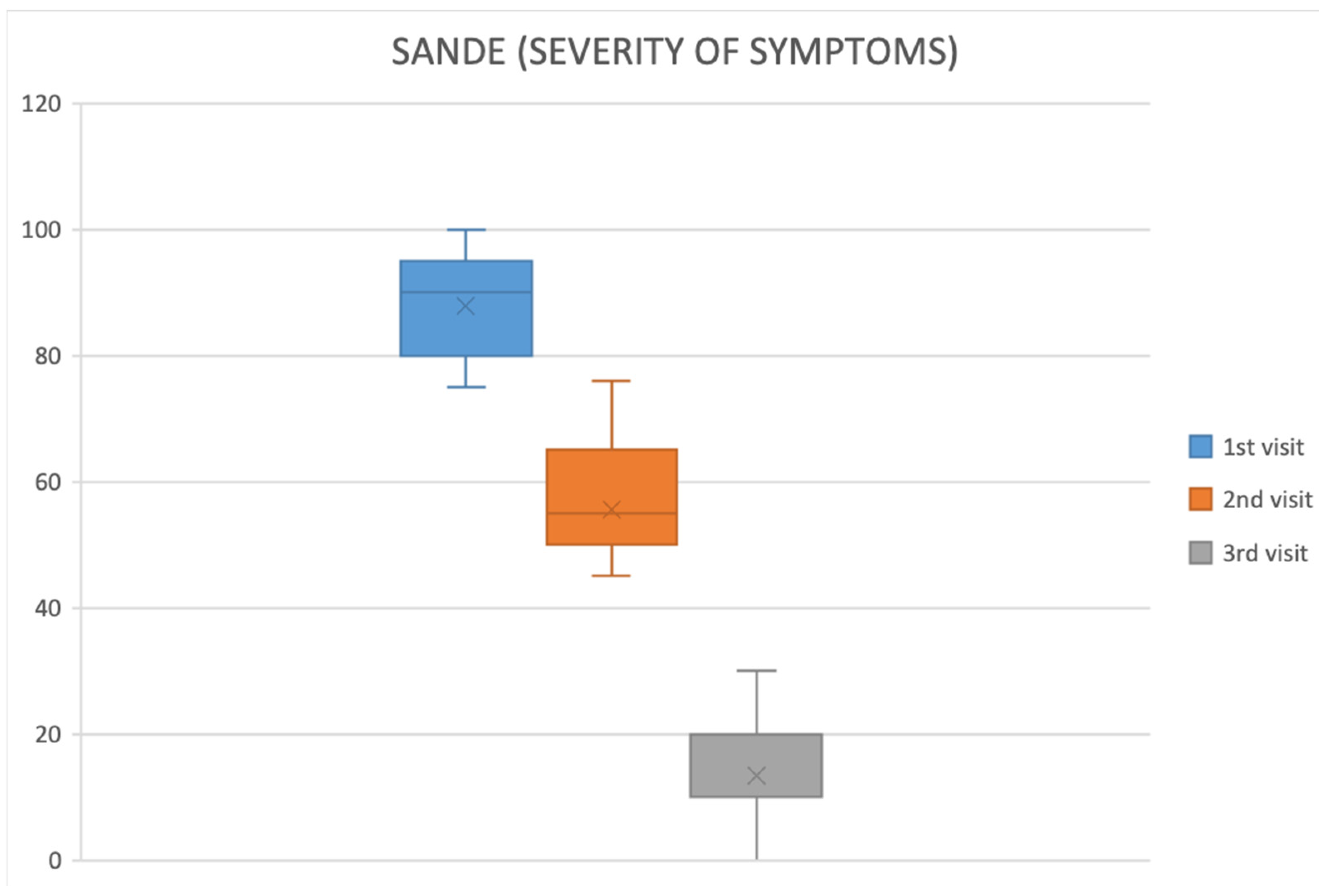

2.2. Symptom Improvement

- OSDI: 89.57 ± 7.79 at baseline → 61.22 ± 8.63 at first follow-up → 15.22 ± 11.33 at final visit (p < 0.05).

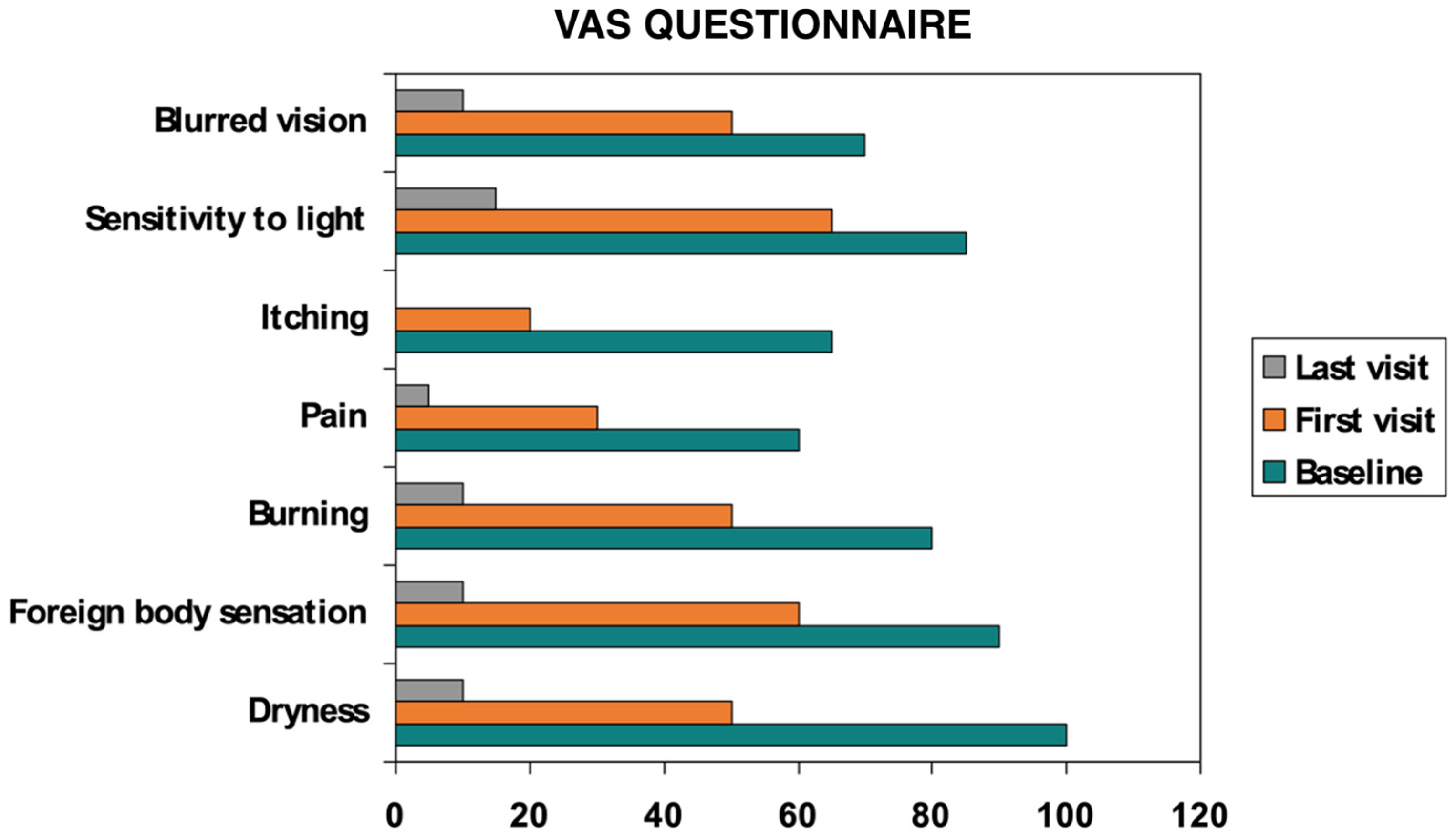

- VAS: discomfort scores fell significantly from baseline to final evaluation (p < 0.05) (Figure 3).

- Improvements emerged earliest and most prominently in autoimmune and GVHD cohorts.

2.3. Objective Clinical Outcomes

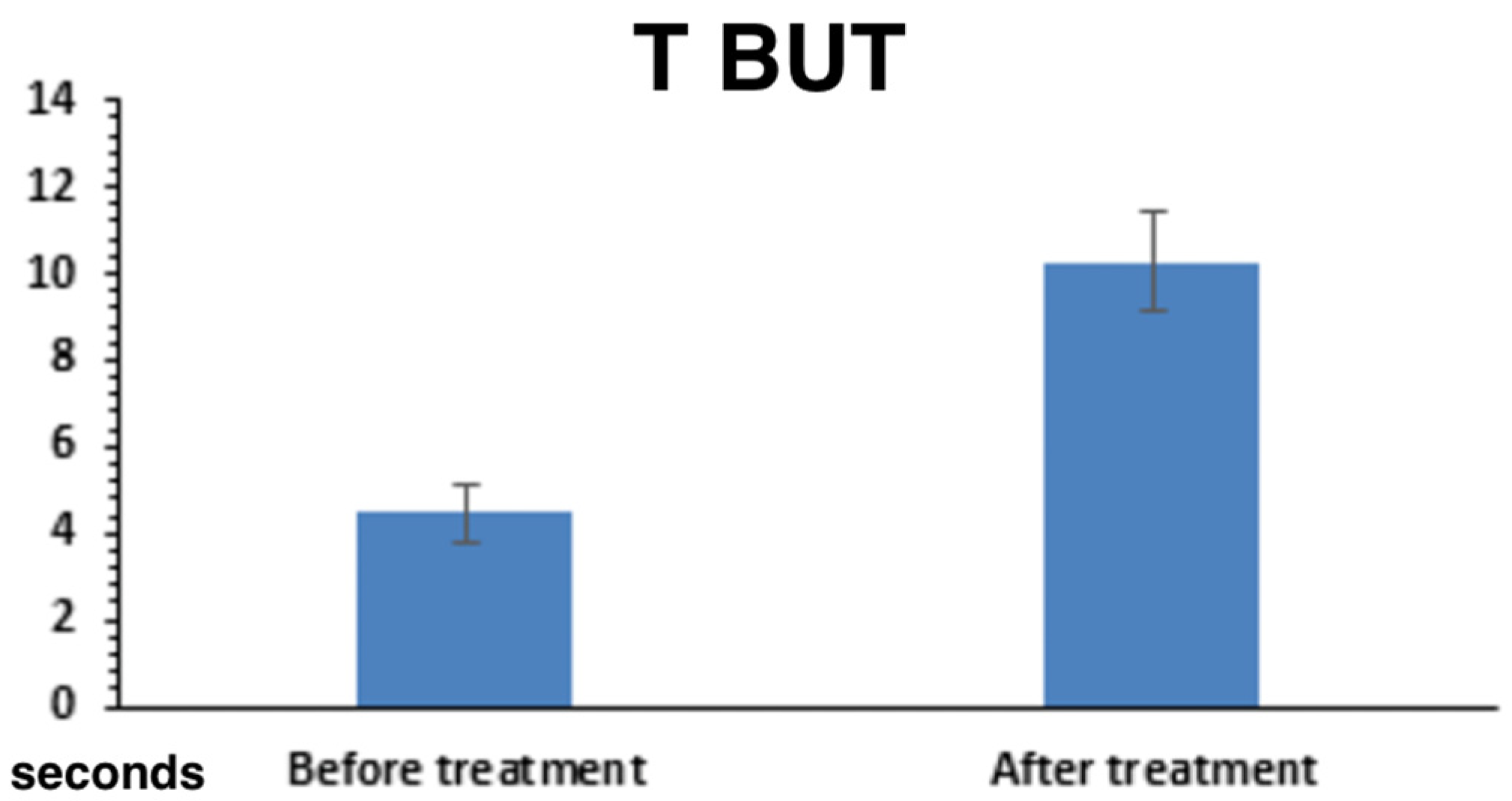

2.3.1. Tear Film Stability and Production

2.3.2. Corneal Epithelial Integrity (Oxford Grading)

2.3.3. Best-Corrected Visual Acuity (BCVA)

2.4. Outcomes in Group III: Neurotrophic Corneal Ulcers

2.5. Safety Profile

3. Discussion

3.1. Relationship to Prior Evidence

3.2. Clinical Impact by Etiology

- Rheumatologic disease (Group I). Patients with Sjögren’s/systemic sclerosis typically present with profound aqueous deficiency and persistent epithelial compromise [21,22]. In our series, 85.6% achieved complete epithelial healing within one week despite prior failures with cyclosporine or therapeutic lenses.

- Ocular GVHD (Group II). GVHD disrupts multiple components of the ocular surface system, including meibomian gland function, with marked tear film instability [22]. We observed substantial reductions in redness, pain, and staining, in line with earlier UCBS reports in GVHD.

- Stevens–Johnson syndrome (Group IV). Although under-represented, SJS cases tolerated UCBS well, with improved epithelial stability and no safety signals.

3.3. Safety Profile

3.4. Study Limitations

3.5. Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Oversight

4.2. Participants and Clinical Groups

- Group I (n = 26): filamentary keratitis and/or corneal ulcers associated with systemic rheumatologic disease (e.g., Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis)

- Group II (n = 15): ocular graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

- Group III (n = 10): neurotrophic corneal ulcers.

- Group IV (n = 4): Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS).

4.3. Preparation of Allogeneic Umbilical Cord Blood Serum (UCBS)

4.4. Treatment Regimen

4.5. Examinations and Outcome Measures

- Symptoms: Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI); SANDE frequency and severity; 10 cm visual analog scale (VAS, 0–100 mm; mean of seven symptom items).

- Ocular surface integrity: fluorescein staining graded by Oxford classification with slit-lamp photography; lissamine green when indicated.

- Tear film: non-invasive break-up time (NIBUT, keratography/CSO) and fluorescein TBUT.

- Visual function: best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA, ETDRS).

- Lacrimation: Schirmer I test (no anesthesia).

- Meibomian glands: meibography (gland dropout; lid margin changes including Marx line.

- Corneal sensitivity: esthesiometry when applicable.

- Clinician-rated signs: corneal inflammation, conjunctivalization, corneal neovascularization, pain.

- Ulcer subgroup (Group III): ulcer area and percent reduction versus baseline recorded at each visit.

4.6. Statistical Analysis

4.7. Composition of Umbilical Cord Blood Serum Eyedrops

- -

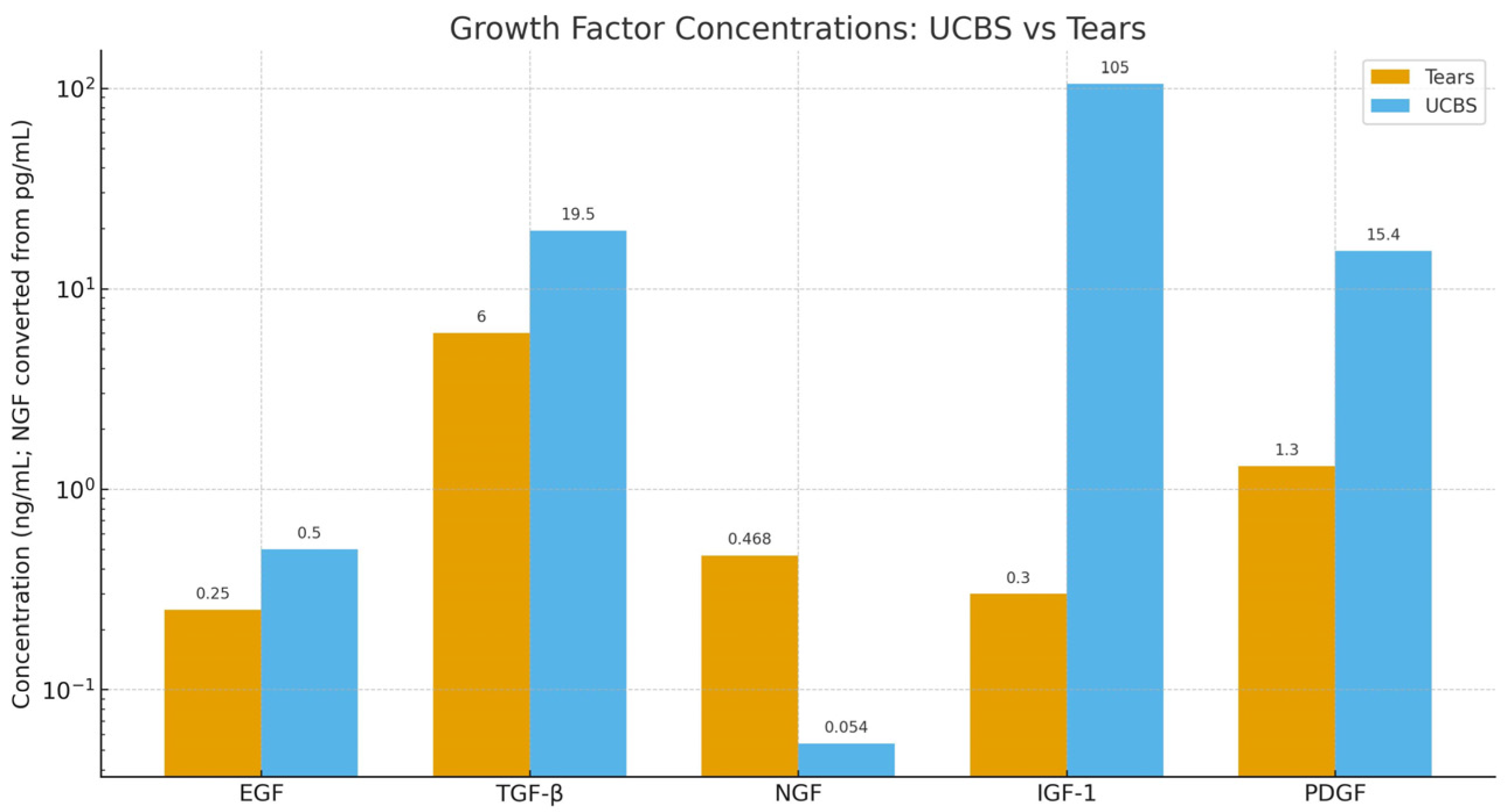

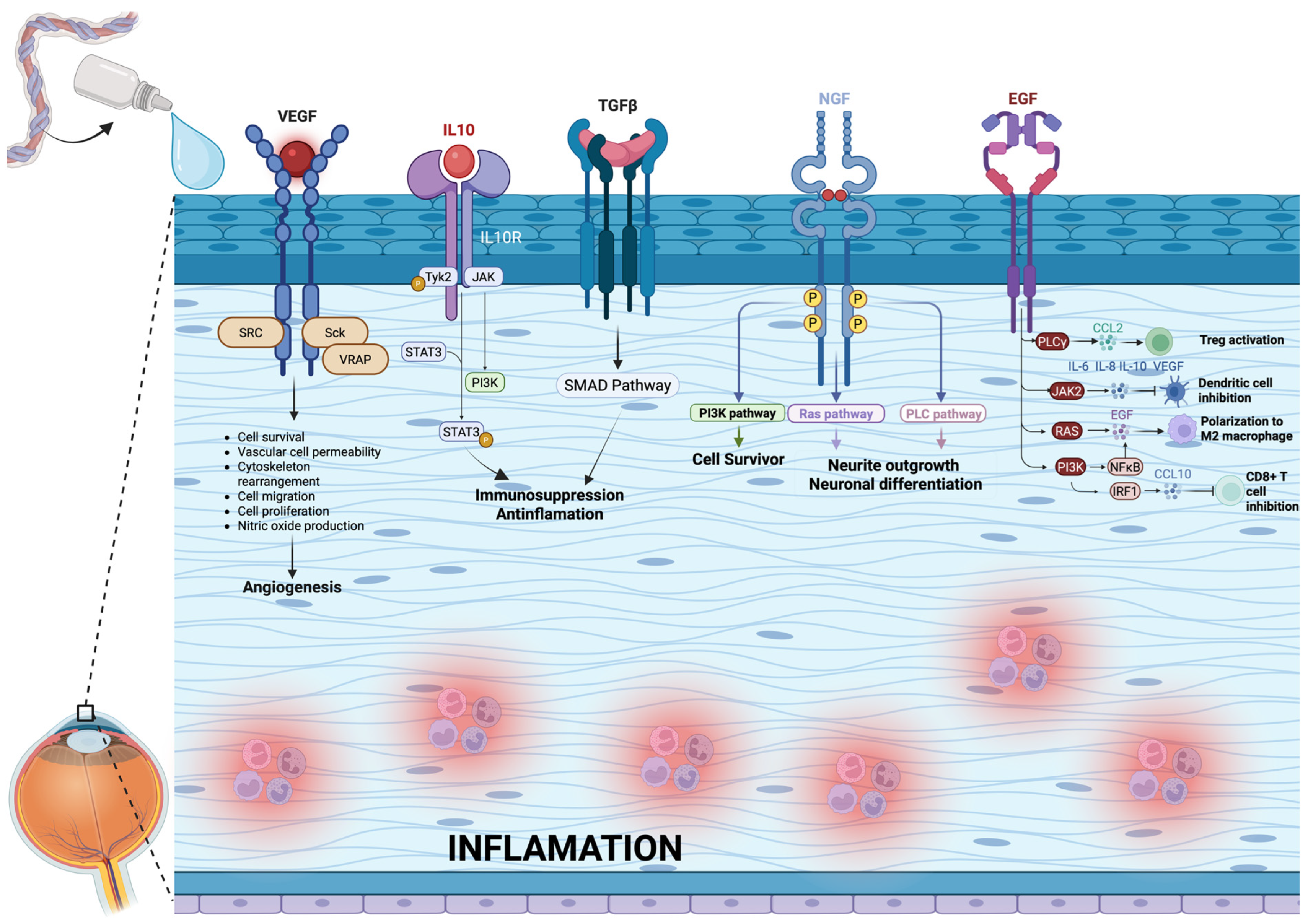

- Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF): It is a mitogen, promotes cell growth and differentiation, and helps corneal heal wounds. It is present in a concentration of 0.2–0.3 ng/mL in tears and 0.5 ng/mL in UCBS.

- -

- Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β)—It is a pleiotropic effect molecule and plays a key role in cellular processes such as cell growth, cell differentiation, and apoptosis. It is present in a concentration of 2–10 ng/mL in tears and 6–33 ng/mL in UCBS.

- -

- Nerve Growth Factor (NGF)—Critical for the survival, maintenance and repair of corneal nerves. Surprisingly, its concentration is significantly lower in UCBS (54 pg/mL) than in tears (468 pg/mL)

- -

- Insulin-like Growth Factor-1(IGF-1)—Involved in promoting keratinocytes growth and enhance their synthesis of collagens and other components of extracellular matrix. It is present in a concentration of 0.3 ng/mL in tears and 105 ng/mL in UCBS.

- -

- Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF): it promotes epithelial and stromal cell proliferation on the ocular surface, migration, and wound healing by stimulating fibroblast activity and extracellular matrix remodeling. It is present in a concentration of 1.3 ng/mL in tears and 15.4 ng/mL in UCBS [12].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Craig, J.P.; Nichols, K.K.; Akpek, E.K.; Caffery, B.; Dua, H.S.; Joo, C.-K.; Liu, Z.; Nelson, J.D.; Nichols, J.J.; Tsubota, K.; et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bron, A.J.; de Paiva, C.S.; Chauhan, S.K.; Bonini, S.; Gabison, E.E.; Jain, S.; Knop, E.; Markoulli, M.; Ogawa, Y.; Perez, V.; et al. TFOS DEWS II pathophysiology report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 438–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Downie, L.E.; Korb, D.; Benitez-Del-Castillo, J.M.; Dana, R.; Deng, S.X.; Dong, P.N.; Geerling, G.; Hida, R.Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 575–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, F.; Alves, M.; Bunya, V.Y.; Jalbert, I.; Lekhanont, K.; Malet, F.; Na, K.-S.; Schaumberg, D.; Uchino, M.; Vehof, J.; et al. TFOS DEWS II epidemiology report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 334–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liang, K.; Jiang, Z.; Tao, L. Sex hormone therapy’s effect on dry eye syndrome in postmenopausal women: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2018, 97, e12572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemanová, M. Dry Eye Disease. A Review. Czech Slovak Ophthalmol. 2021, 77, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagci, A.; Gurdal, C. The role and treatment of inflammation in dry eye disease. Int. Ophthalmol. 2014, 34, 1291–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, V.; Kolli, S.S.; Strowd, L.C. Review of Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Dermatol. Clin. 2019, 37, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartwig, D.; Herminghaus, P.; Wedel, T.; Liu, L.; Schlenke, P.; Dibbelt, L.; Geerling, G. Epitheliotrophic capacity of plasma vs serum in vitro. Transfus. Med. 2005, 15, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannaccare, G.; Versura, P.; Buzzi, M.; Primavera, L.; Pellegrini, M.; Campos, E.C. Blood-derived eye drops for cornea/ocular surface diseases. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2017, 56, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondy, P.; Brama, T.; Fisher, J.; Gemelli, C.N.; Chee, K.; Keegan, A.; Waller, D. Sustained benefits of autologous serum eye drops on self-reported ocular symptoms and vision-related quality of life in Australian patients with dry eye and corneal epithelial defects. Transfus Apher Sci. 2015, 53, 404–411, Epub 2015 Nov 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Versura, P.; Buzzi, M.; Giannaccare, G.; Terzi, A.; Fresina, M.; Velati, C.; Campos, E.C. Maternal peripheral vs cord blood for eye drops. Blood Transfus. 2016, 14, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanov, Y.A.; Vtorushina, V.V.; Dugina, T.N.; Romanov, A.Y.; Petrova, N.V. Cord blood serum/plasma: Cytokine profile. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 168, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.C.; Im, S.K.; Park, Y.G.; Jung, Y.D.; Yang, S.Y.; Choi, J. Umbilical cord serum eyedrops for dry eye. Cornea 2006, 25, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.C.; Jeong, I.Y.; Im, S.K.; Park, Y.G.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, J. UCBS in GVHD dry eye. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007, 39, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.C.; Heo, H.; Im, S.K.; You, I.C.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, Y.G. Autologous vs umbilical cord serum eye drops. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 144, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo-De-Mora, M.R.; Domínguez-Ruiz, C.; Barrero-Sojo, F.; Rodríguez-Moreno, G.; Rodríguez, C.A.; Verdugo, L.P.; Lamas, M.d.C.H.; Hernández-Guijarro, L.; Castillo, J.V.; Casares, I.F.; et al. Autologous vs allogeneic vs. UC sera in severe DED: DB-RCT. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, e396–e408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, E.; Versura, P.; Buzzi, M.; Fontana, L.; Giannaccare, G.; Pellegrini, M.; Lanconelli, N.; Brancaleoni, A.; Moscardelli, F.; Sebastiani, S.; et al. Allogeneic sources for severe dry eye: Multicentre randomized crossover. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 104, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versura, P.; Profazio, V.; Buzzi, M.; Stancari, A.; Arpinati, M.; Malavolta, N.; Campos, E.C. Quality-controlled cord blood serum in severe epithelial damage (dry eye). Cornea 2013, 32, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasetti, F.; Usai, D.; Sotgia, S.; Carru, C.; Zanetti, S.; Pinna, A. Protocol for microbiologically safe autologous serum eye-drops. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2015, 9, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wolffsohn, J.S.; Arita, R.; Chalmers, R.; Djalilian, A.; Dogru, M.; Dumbleton, K.; Gupta, P.K.; Karpecki, P.; Lazreg, S.; Pult, H.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 539–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannaccare, G.; Pellegrini, M.; Bernabei, F.; Scorcia, V.; Campos, E. Ocular surface alterations in ocular GVHD. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2019, 257, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semeraro, F.; Forbice, E.; Romano, V.; Angi, M.; Romano, M.; Filippelli, M.; Di Iorio, R.; Costagliola, C. Neurotrophic keratitis. Ophthalmologica 2014, 231, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.; Fukuoka, S.; Karagianni, N.; Guaiquil, V.H.; Rosenblatt, M.I. VEGF promotes recovery of injured corneal nerves. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 2756–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel Farag, R.; Dawood, M.; Elesawi, M. UC blood platelet lysate for resistant corneal ulcer. Med. Hypothesis Discov. Innov. Ophthalmol. J. 2023, 11, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, M.H.; Hasby, H.A.; Khater, M.M.; Ghoneim, A.M. Evaluation of the effect of umbilical cord blood serum therapy in resistant infected corneal ulcers. Delta J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 24, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Muruzabal, F.; Tayebba, A.; Riestra, A.; Perez, V.L.; Merayo-Lloves, J.; Orive, G. Autologous serum and plasma rich in growth factors in ophthalmology: Preclinical and clinical studies. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015, 93, e605–e614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | No. of Patients (Eyes) | Primary Clinical Condition | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| I—Rheumatologic diseases | 26 | Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic sclerosis, other connective tissue diseases | Severe aqueous tear deficiency with persistent epithelial defects, pain, and photophobia. All had previously failed treatment with cyclosporine and therapeutic contact lenses. |

| II—Ocular GVHD | 15 | Ocular graft-versus-host disease following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | Marked tear film instability with MGD, hyperemia, severe pain, and high risk of corneal ulceration. |

| III—Neurotrophic corneal ulcers | 10 | Corneal ulcers due to loss of corneal innervation | Poor healing response due to reduced corneal sensitivity, with high risk of perforation and irreversible visual loss. |

| IV—Stevens–Johnson Syndrome | 4 | Chronic sequelae of SJS/TEN | Profound epithelial instability and chronic inflammation with minimal response to conventional therapies. |

| Outcome | Baseline (Mean ± SD) | Final Follow-Up (Mean ± SD) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSDI (0–100) ↑ worse | 89.57 ± 7.79 | 15.22 ± 11.33 | <0.001 |

| SANDE—Frequency (0–100) ↑ worse | 87.83 ± 9.27 | 13.48 ± 8.85 | <0.001 |

| SANDE—Severity (0–100) ↑ worse | 89.57 ± 7.79 | 15.22 ± 11.33 | <0.001 |

| VAS (0–100 mm) ↑ worse | 88.40 ± 8.90 | 18.70 ± 9.10 | <0.001 |

| TBUT (seconds) ↑ better | 2.54 ± 0.62 | 7.41 ± 0.57 | <0.001 |

| Schirmer I (mm/5 min) ↑ better | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 8.6 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zeppieri, M.; Gagliano, G.; Capobianco, M.; Gagliano, C.; Cappellani, F.; Tancredi, G.; Avitabile, A.; Cannizzaro, L.; D’Esposito, F. Allogeneic Umbilical Cord Blood Serum Eyedrops for the Treatment of Severe Dry Eye Disease Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110782

Zeppieri M, Gagliano G, Capobianco M, Gagliano C, Cappellani F, Tancredi G, Avitabile A, Cannizzaro L, D’Esposito F. Allogeneic Umbilical Cord Blood Serum Eyedrops for the Treatment of Severe Dry Eye Disease Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110782

Chicago/Turabian StyleZeppieri, Marco, Giuseppe Gagliano, Matteo Capobianco, Caterina Gagliano, Francesco Cappellani, Giuseppa Tancredi, Alessandro Avitabile, Ludovica Cannizzaro, and Fabiana D’Esposito. 2025. "Allogeneic Umbilical Cord Blood Serum Eyedrops for the Treatment of Severe Dry Eye Disease Patients" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110782

APA StyleZeppieri, M., Gagliano, G., Capobianco, M., Gagliano, C., Cappellani, F., Tancredi, G., Avitabile, A., Cannizzaro, L., & D’Esposito, F. (2025). Allogeneic Umbilical Cord Blood Serum Eyedrops for the Treatment of Severe Dry Eye Disease Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110782