Lidocaine Attenuates miRNA Dysregulation and Kinase Signaling Activation in a Porcine Model of Lung Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

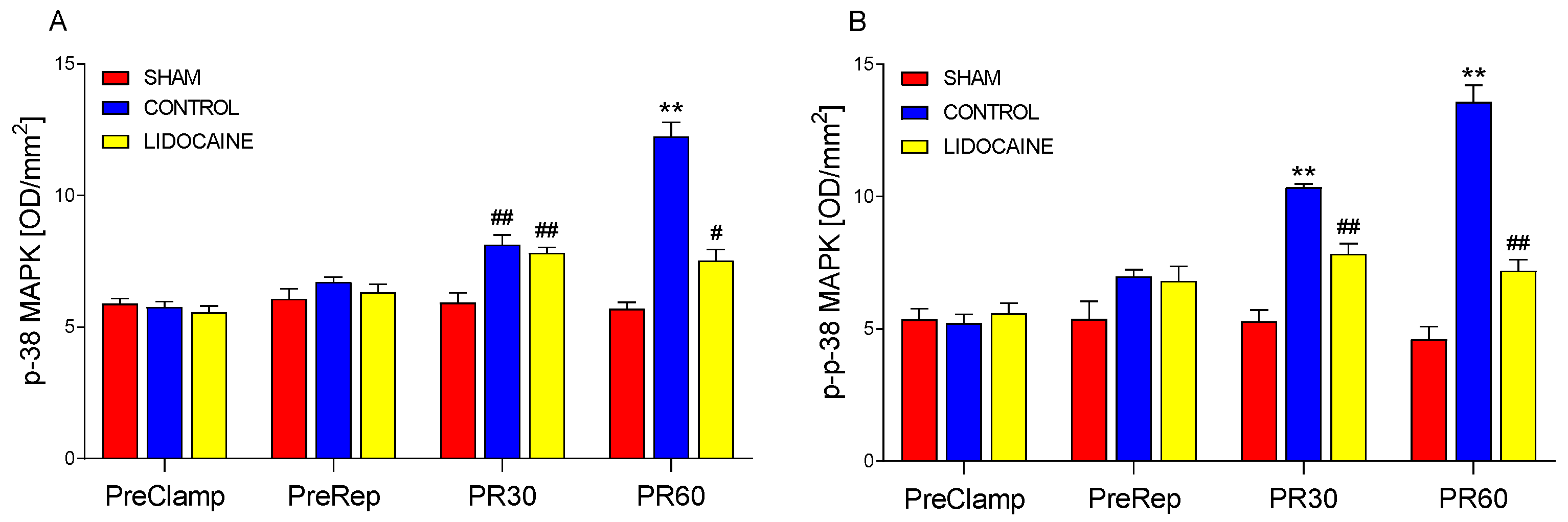

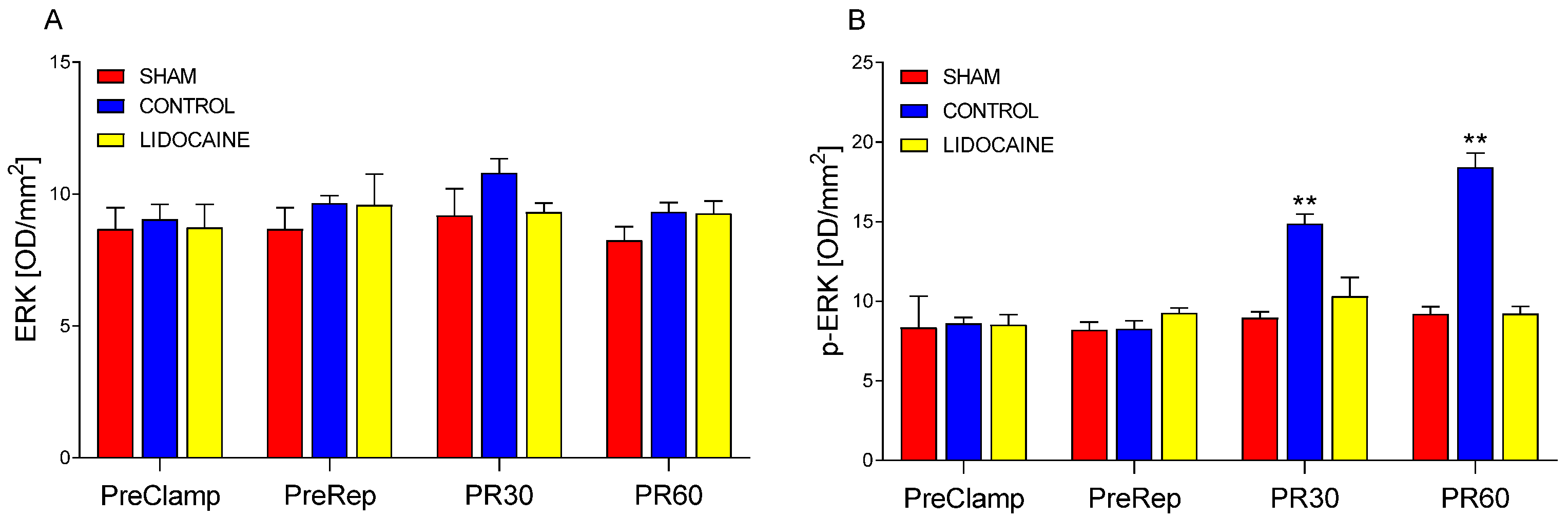

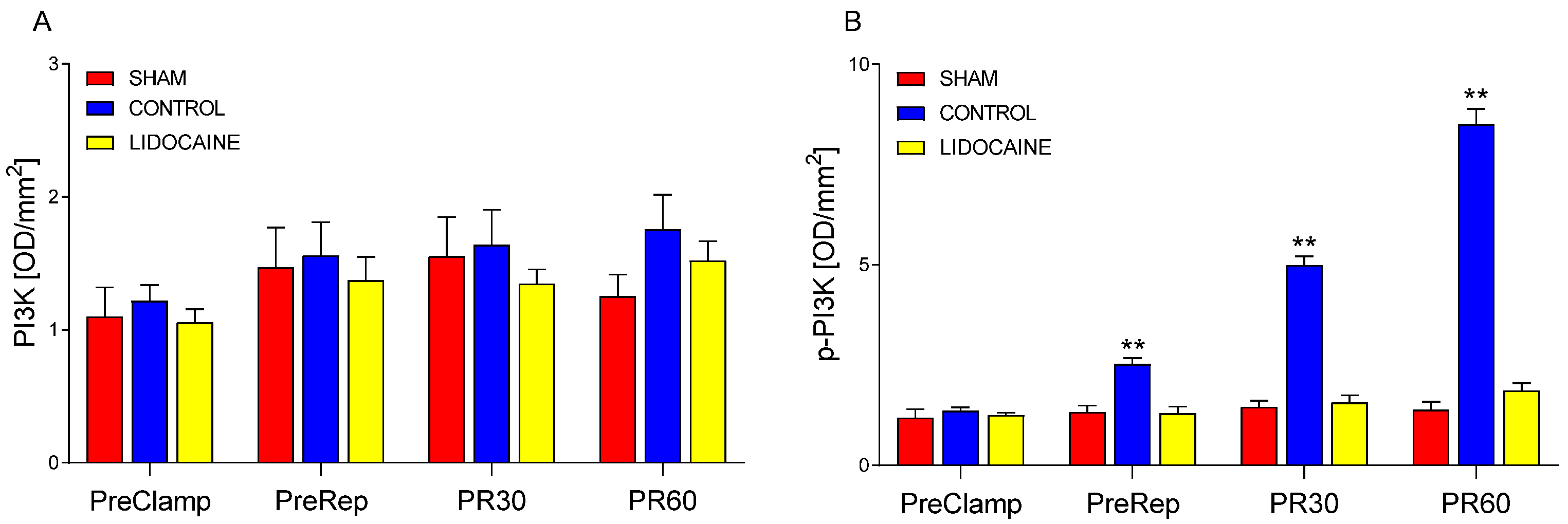

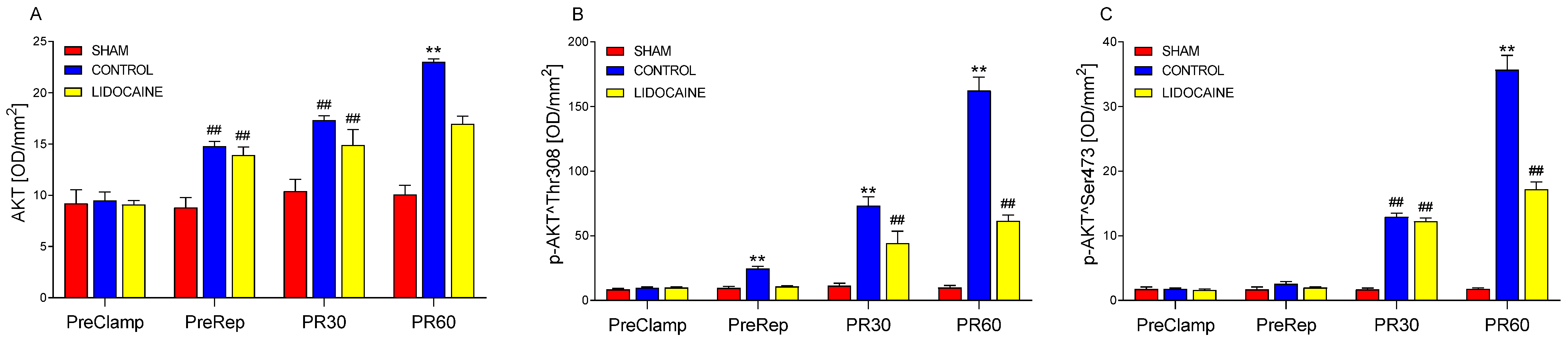

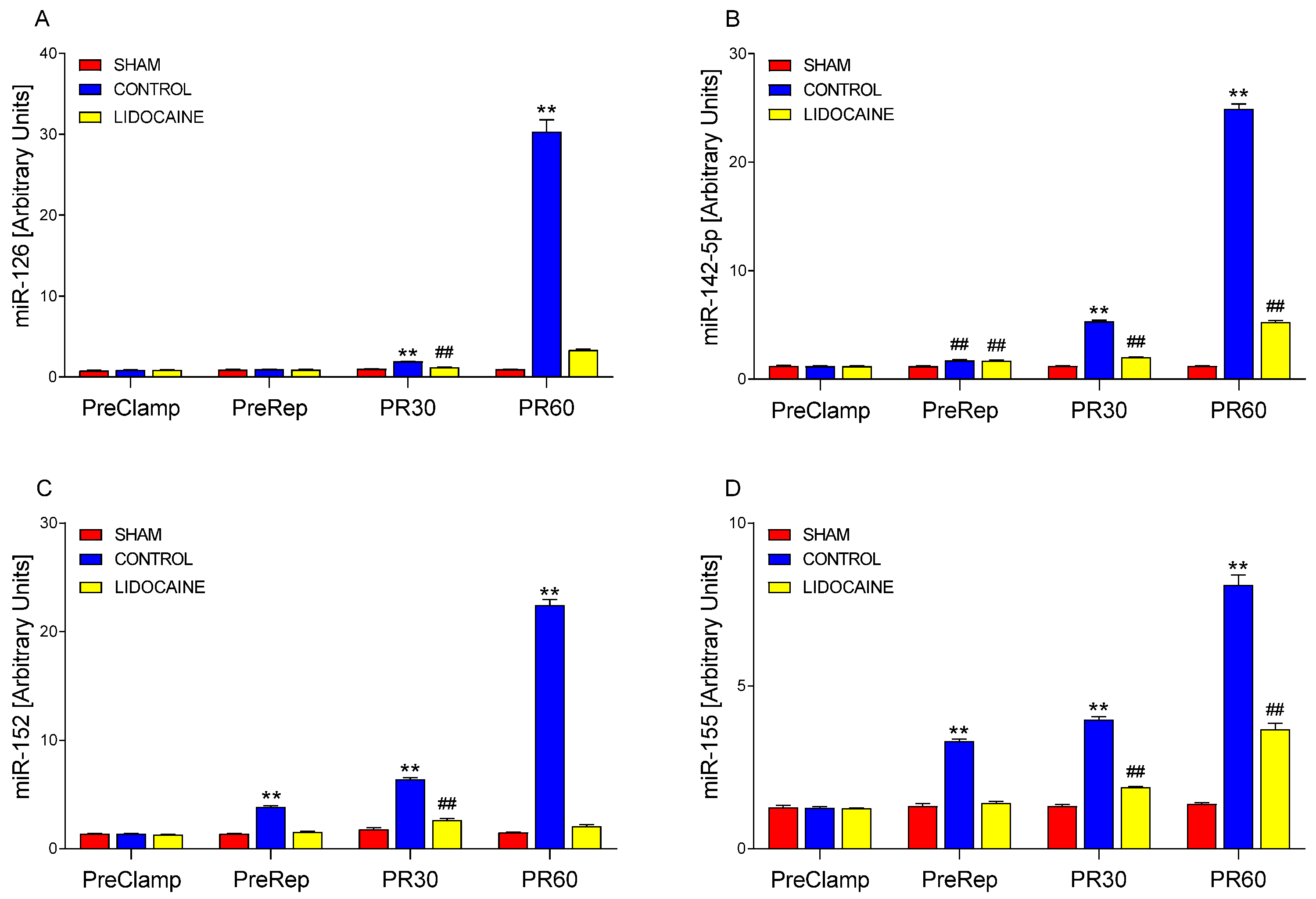

2. Results

3. Discussion

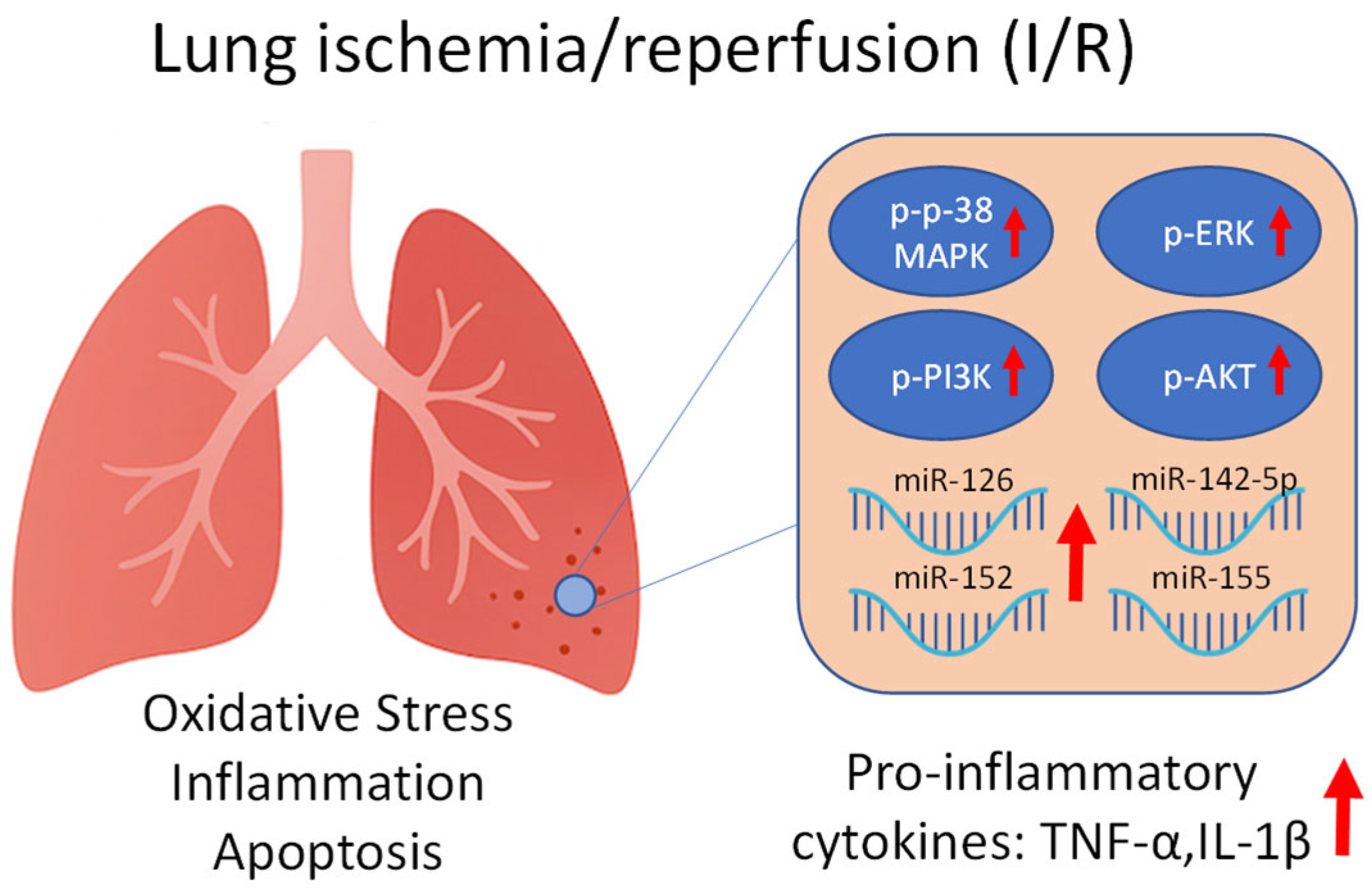

3.1. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying I/R Injury

3.2. Modulatory Effects of Lidocaine on MAPK and miRNA Responses

3.3. Integrated Mechanisms and Supporting Evidence from Previous Studies

3.4. Clinical Implications and Future Perspectives

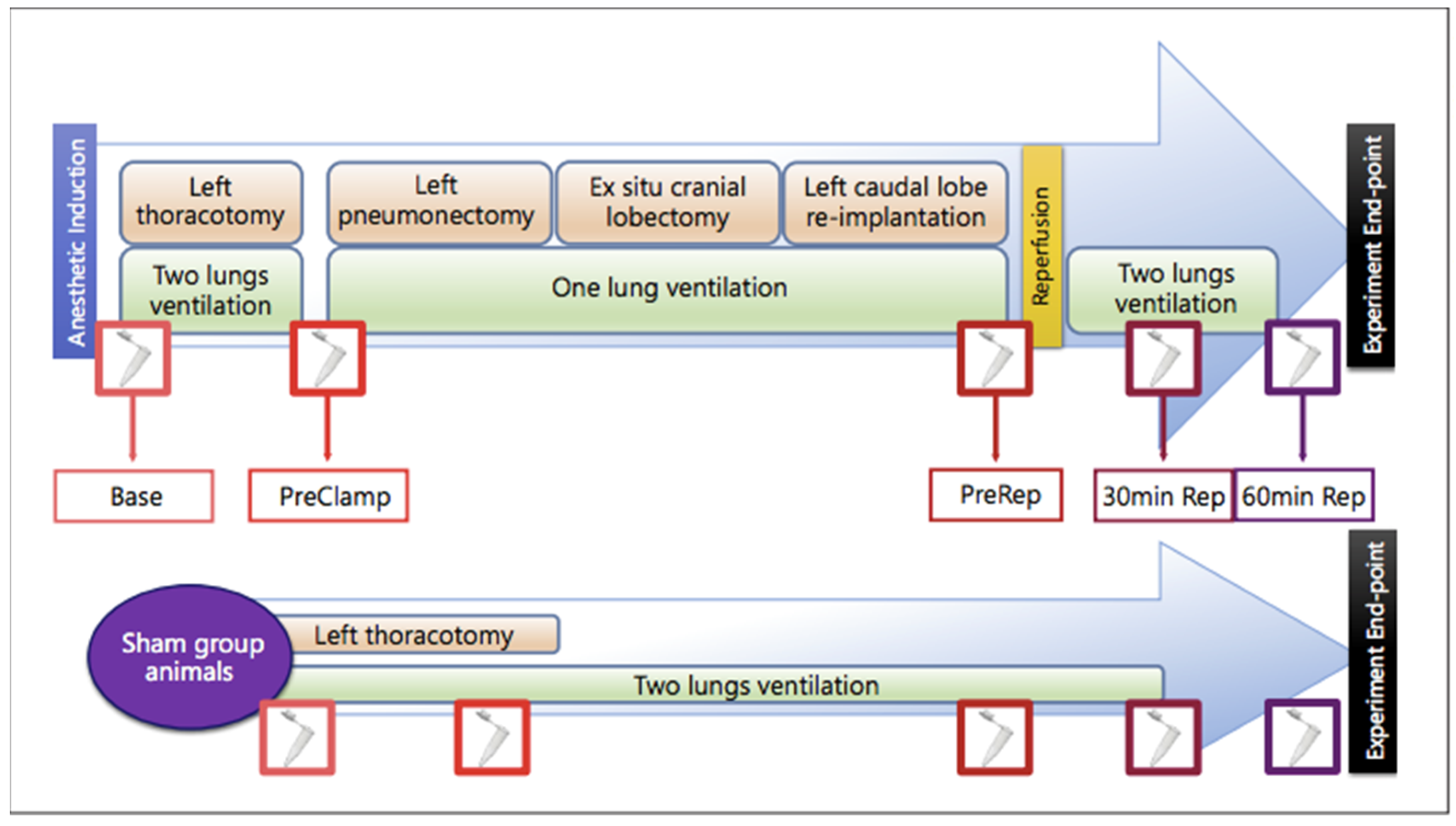

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Model and Study Groups

4.2. Surgical Procedure

4.3. Hemodynamic and Arterial Blood Gas Analysis

4.4. Western Blotting Analysis

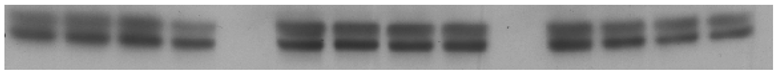

4.5. miRNA Extraction and Expression Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- de Perrot, M.; Liu, M.; Waddell, T.K.; Keshavjee, S. Ischemia-reperfusion-induced lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 167, 490–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Dolan, M.E. Emerging role of microRNAs in drug response. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2010, 12, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Zhang, W. Integrating microRNAs into a system biology approach to acute lung injury. Transl. Res. 2011, 157, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moazed, D. Small RNAs in transcriptional gene silencing and genome defence. Nature 2009, 457, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R.S. MicroRNA function: Multiple mechanisms for a tiny RNA? RNA 2005, 11, 1753–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Guo, C.; Tang, H.; Zhang, M. miR-30a-5p attenuates hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis by regulating PTEN expression and activating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, J.; Rao, D.S. MicroRNAs in inflammation and immune responses. Leukemia 2012, 26, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J.; Yan, S.; Zhou, L.; Xie, H.; Chen, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; et al. miR-152 may silence translation of CaMK II and induce spontaneous immune tolerance in mouse liver transplantation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, J.; Tomomi, T.; Nieves, E.; Mathewson, N.; Tamaki, H.; Evers, R.; Reddy, P. PU.1-dependent transcriptional regulation of miR-142 contributes to its hematopoietic cell-specific expression and modulation of IL-6. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 4005–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Aurora, A.B.; Johnson, B.A.; Qi, X.; McAnally, J.; Hill, J.A.; Richardson, J.A.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev. Cell 2008, 15, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lee, J.D.; Bibbs, L.; Ulevitch, R.J. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science 1994, 265, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Du, T.; Li, B.; Rong, Y.; Verkhratsky, A.; Peng, L. Crosstalk between MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signal pathways during brain ischemia/reperfusion. ASN Neuro 2015, 7, e00189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollmann, M.W.; Gross, A.; Jelacin, N.; Durieux, M.E. Local anesthetic effects on priming and activation of human neutrophils. Anesthesiology 2001, 95, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, G.C.; Megalla, S.A.; Habib, A.S. Impact of intravenous lidocaine infusion on postoperative analgesia and recovery from surgery: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Drugs 2010, 70, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Sano, Y.; Todorova, K.; Carlson, B.A.; Arpa, L.; Celada, A.; Lawrence, T.; Otsu, K.; Brissette, J.L.; Arthur, J.S.C.; et al. The kinase p38 alpha serves cell type-specific inflammatory functions in skin injury and coordinates pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression. Nat. Immunol. 2008, 9, 1019–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.K. MAP kinase pathways. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a011254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas, V.R.; Dumur, C.I.; Scian, M.J.; Gehrau, R.C.; Maluf, D.G. MicroRNAs as biomarkers in solid organ transplantation. Am. J. Transplant. 2013, 13, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Cui, W.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Xue, X.; Cai, J.; Zhao, W.; Gao, W. Erythropoietin alleviates acute lung injury induced by ischemia-reperfusion through blocking p38 MAPK signaling. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2021, 40 (Suppl. S12), S593–S602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Ma, J.; Meng, X.-W.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Song, S.-Y.; Chen, Q.-C.; Liu, H.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Peng, K.; et al. Heat Shock Protein 70 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 3908641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ju, F.; Du, L.; Liu, T.; Zuo, Y.; Abbott, G.W.; Hu, Z. Empagliflozin protects against pulmonary ischemia/reperfusion injury via an ERK1/2-dependent mechanism. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2022, 380, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Dexmedetomidine alleviates lung ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats by activating PI3K/Akt pathway. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Fan, H.; Shi, Y.; Xu, S.T.; Yuan, Y.F.; Zheng, R.H.; Wang, Q. Prevention of lung ischemia-reperfusion injury by short hairpin RNA-mediated caspase-3 gene silencing. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 139, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lango, R.; Mroziński, P. Clinical importance of anaesthetic preconditioning. Anestezjol. Intensywna Ter. 2010, 42, 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Garutti, I.; Rancan, L.; Simón, C.; Cusati, G.; Sanchez-Pedrosa, G.; Moraga, F.; Olmedilla, L.; Lopez-Gil, M.T.; Vara, E. Intravenous lidocaine decreases tumor necrosis factor alpha expression both locally and systemically in pigs undergoing lung resection surgery. Anesth. Analg. 2014, 119, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, B.D.; Toker, A. AKT/PKB signaling: Navigating the network. Cell 2017, 169, 381–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksamitiene, E.; Kiyatkin, A.; Kholodenko, B.N. Cross-talk between mitogenic Ras/MAPK and survival PI3K/Akt pathways: A fine balance. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 1311–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rancan, L.; Simón, C.; Marchal-Duval, E.; Casanova, J.; Paredes, S.D.; Calvo, A.; García, C.; Rincón, D.; Turrero, A.; Garutti, I.; et al. Lidocaine administration controls microRNAs alterations observed after lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. Anesth. Analg. 2016, 123, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Zhao, Q.; He, C.; Huang, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, F.; Chen, J.; Liao, J.-Y.; Cui, X.; Zeng, Y.; et al. miR-142-5p and miR-130a-3p are regulated by IL-4 and IL-13 and control profibrogenic macrophage program. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, R.M.; Chaudhuri, A.A.; Rao, D.S.; Baltimore, D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 7113–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-M.; Peter, M.E. microRNAs and death receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008, 19, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, E.R.; Amini, M.; Najafi, S.; Mansoori, B.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Mohammadi, A.; Lotfinejad, P.; Bagheri, M.; Shirjang, S.; Lotfi, Z.; et al. Interplay between MAPK/ERK signaling pathway and microRNAs: A crucial mechanism regulating cancer cell metabolism and tumor progression. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish, J.E.; Santoro, M.M.; Morton, S.U.; Yu, S.; Yeh, R.-F.; Wythe, J.D.; Ivey, K.N.; Bruneau, B.G.; Stainier, D.Y.R.; Srivastava, D. miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Dev. Cell 2008, 15, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.A.; Yamakuchi, M.; Ferlito, M.; Mendell, J.T.; Lowenstein, C.J. MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1516–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, J.; Garutti, I.; Simon, C.; Giraldez, A.; Martin, B.; Gonzalez, G.; Azcarate, L.; Garcia, C.; Vara, E. The effects of anesthetic preconditioning with sevoflurane in an experimental lung autotransplant model in pigs. Anesth. Analg. 2011, 113, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romera, A.; Cebollero, M.; Romero-Gómez, B.; Carricondo, F.; Zapatero, S.; García-Aldao, U.; Martín-Albo, L.; Ortega, J.; Vara, E.; Garutti, I.; et al. Effect of Intravenous Lidocaine on Inflammatory and Apoptotic Response of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Pigs Undergoing Lung Resection Surgery. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6630232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mets, B.; Allin, R.; van Dyke, J.; Hickman, R. Lidocaine decay and hepatic extraction in the pig. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 1993, 16, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satas, S.; Johannessen, S.I.; Hoem, N.O.; Haaland, K.; Sørensen, D.R.; Thoresen, M. Lidocaine pharmacokinetics and toxicity in newborn pigs. Anesth. Analg. 1997, 85, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, E.; Nimmo, S.; Paterson, H.; Homer, N.; Foo, I. Intravenous lidocaine infusion as a component of multimodal analgesia for colorectal surgery-measurement of plasma levels. Perioper. Med. 2019, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancan, L.; Paredes, S.D.; Huerta, L.; Casanova, J.; Guzmán, J.; Garutti, I.; González-Aragoneses, F.; Simón, C.; Vara, E. Chemokine involvement in lung injury secondary to ischaemia/reperfusion. Lung 2017, 195, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancan, L.; Huerta, L.; Cusati, G.; Erquicia, I.; Isea, J.; Paredes, S.D.; García, C.; Garutti, I.; Simón, C.; Vara, E. Sevoflurane prevents liver inflammatory response induced by lung ischemia-reperfusion. Transplantation 2014, 98, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, K.; Chen, L.; Jiang, A.-A.; Wang, J.; Lv, X.; Li, X. Identification of suitable endogenous control microRNA genes in normal pig tissues. Anim. Sci. J. 2011, 82, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sham | Control | Lidocaine | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre Clamp | Pre Rep | PR30 | PR60 | Pre Clamp | Pre Rep | PR30 | PR60 | Pre Clamp | Pre Rep | PR30 | PR60 | ||

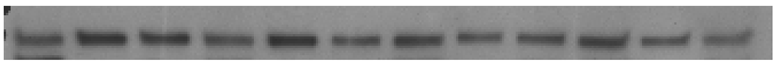

| p-38 MAPK | 43 kDa |  | |||||||||||

| p-p-38 MAPK | 43 kDa |  | |||||||||||

| ERK | 42.4 kDa |  | |||||||||||

| p-ERK | 42.4 kDa |  | |||||||||||

| PI3K | 85 kDa |  | |||||||||||

| p-PI3K | 85 kDa |  | |||||||||||

| AKT | 60 kDa |  | |||||||||||

| p-AKT Thr | 60 kDa |  | |||||||||||

| p-AKT Ser | 60 kDa |  | |||||||||||

| GAPDH | 37 kDa |  | |||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alonso, A.; Paredes, S.D.; Turrero, A.; Rancan, L.; Garutti, I.; Simón, C.; Vara, E. Lidocaine Attenuates miRNA Dysregulation and Kinase Signaling Activation in a Porcine Model of Lung Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110385

Alonso A, Paredes SD, Turrero A, Rancan L, Garutti I, Simón C, Vara E. Lidocaine Attenuates miRNA Dysregulation and Kinase Signaling Activation in a Porcine Model of Lung Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110385

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlonso, Alberto, Sergio D. Paredes, Agustín Turrero, Lisa Rancan, Ignacio Garutti, Carlos Simón, and Elena Vara. 2025. "Lidocaine Attenuates miRNA Dysregulation and Kinase Signaling Activation in a Porcine Model of Lung Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110385

APA StyleAlonso, A., Paredes, S. D., Turrero, A., Rancan, L., Garutti, I., Simón, C., & Vara, E. (2025). Lidocaine Attenuates miRNA Dysregulation and Kinase Signaling Activation in a Porcine Model of Lung Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110385