Antitumor Effect of Poplar Propolis on Human Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma A431 Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

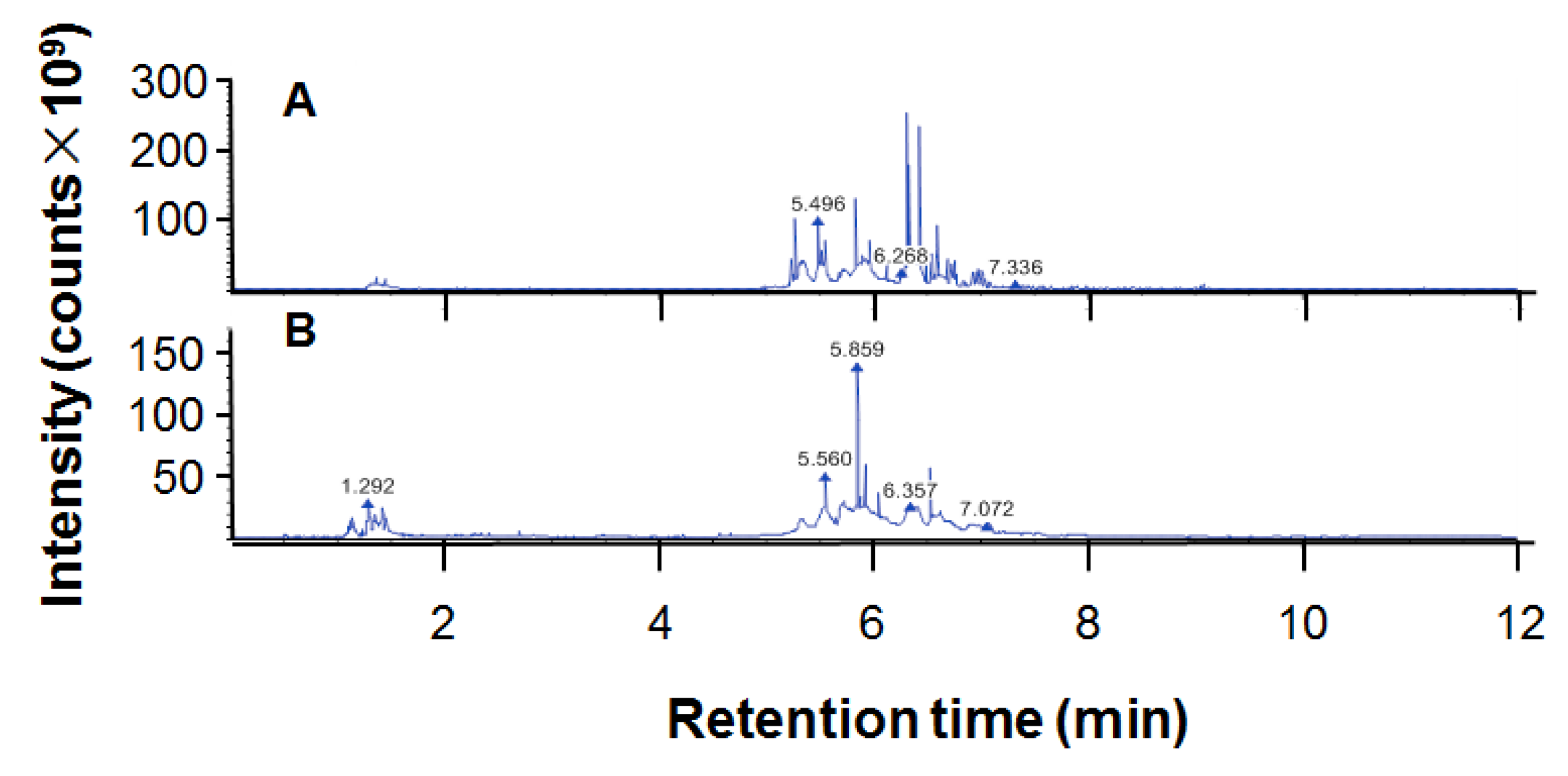

2.1. Components of Ethanol Extract of Propolis

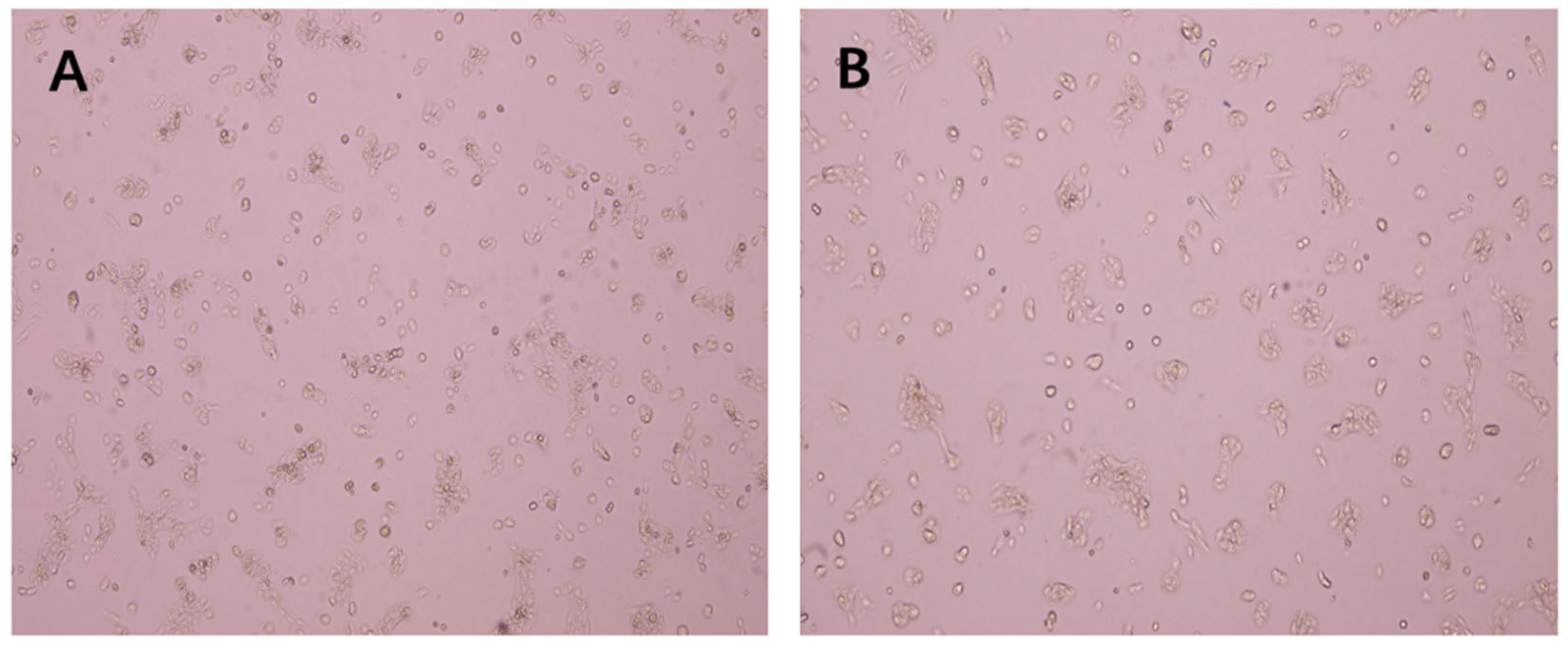

2.2. The Antitumor Effect of Ethanol Extract of Propolis (EEP)

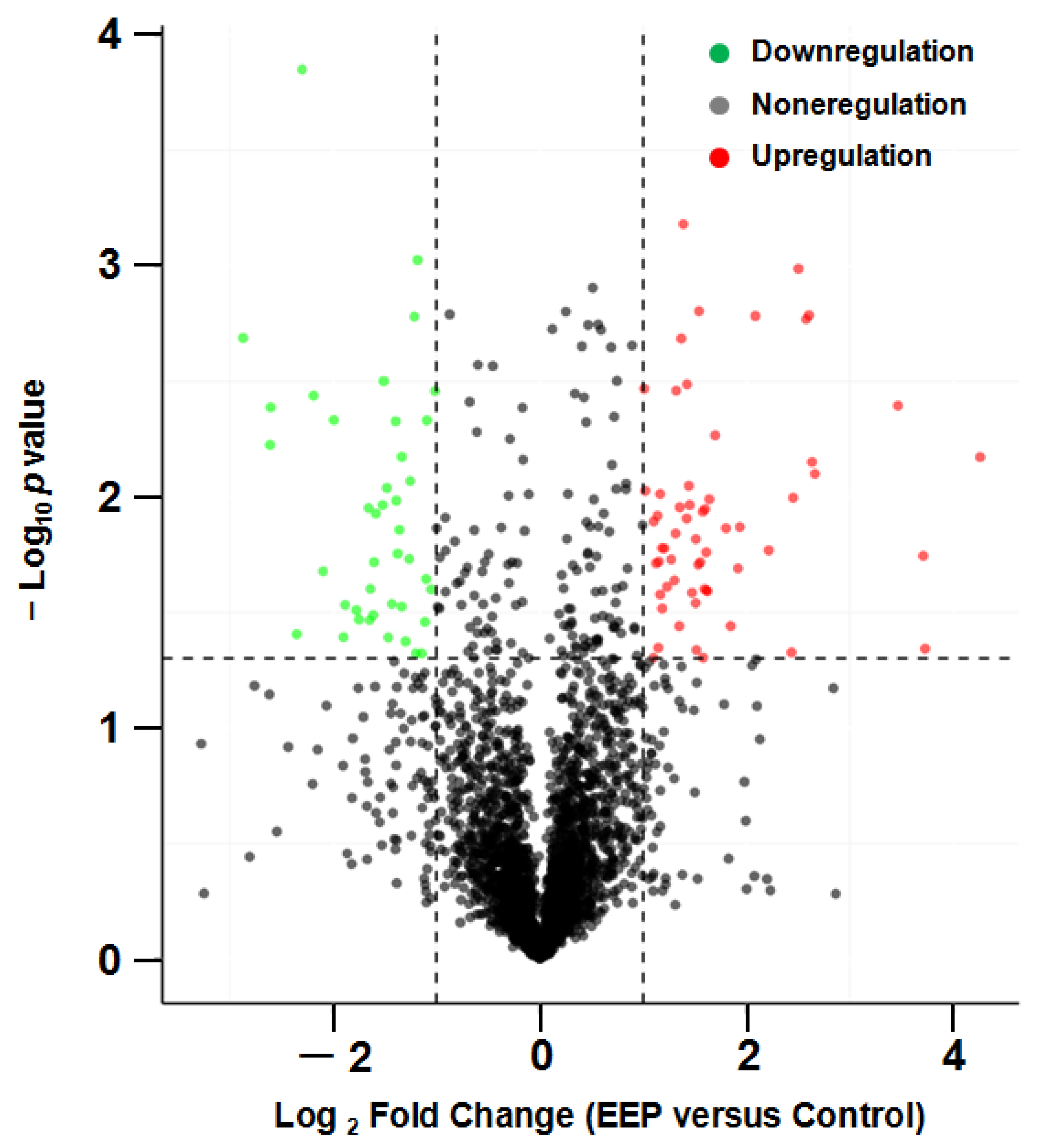

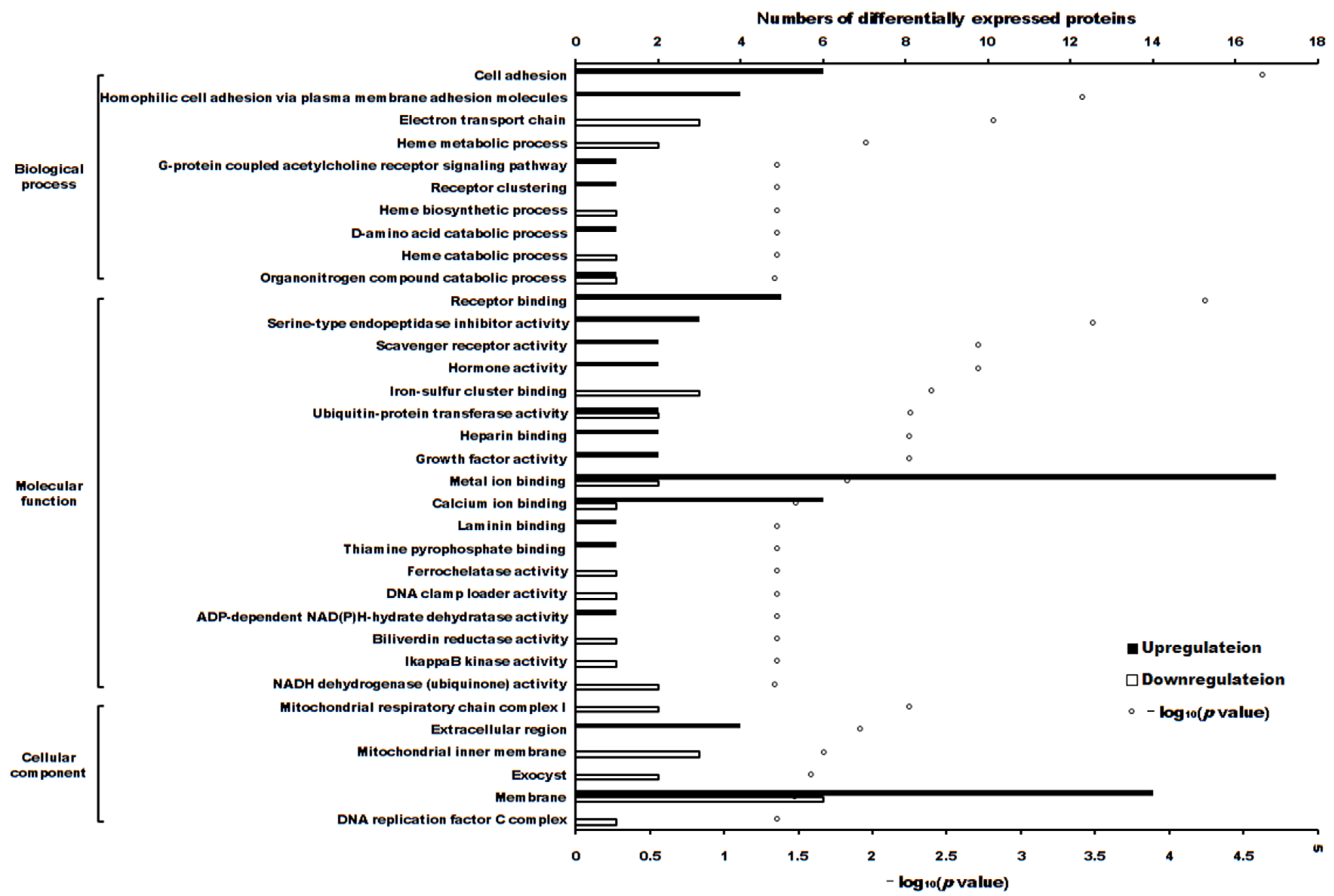

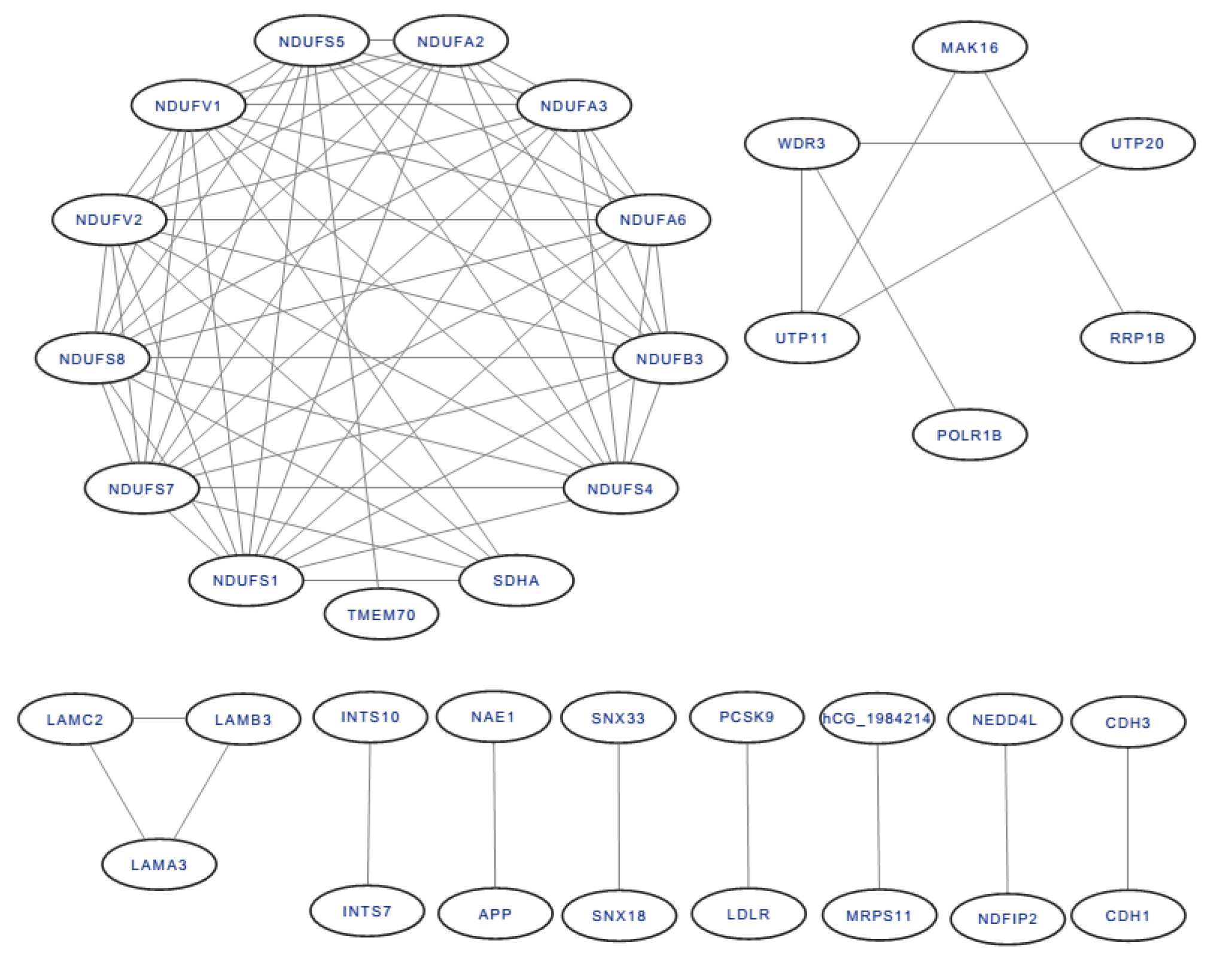

2.3. The Differentially Expressed Proteins

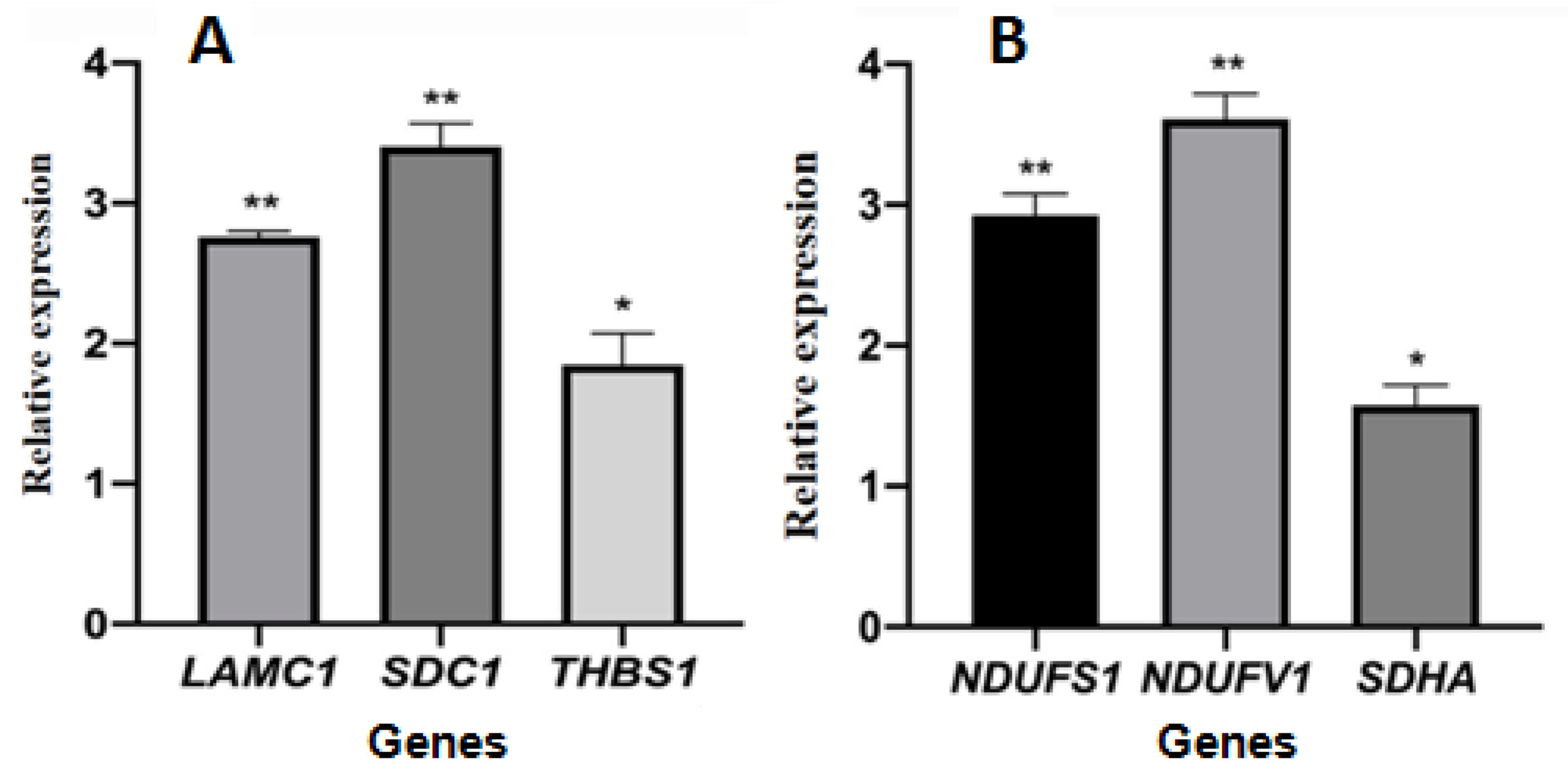

2.4. Relative Gene Expression

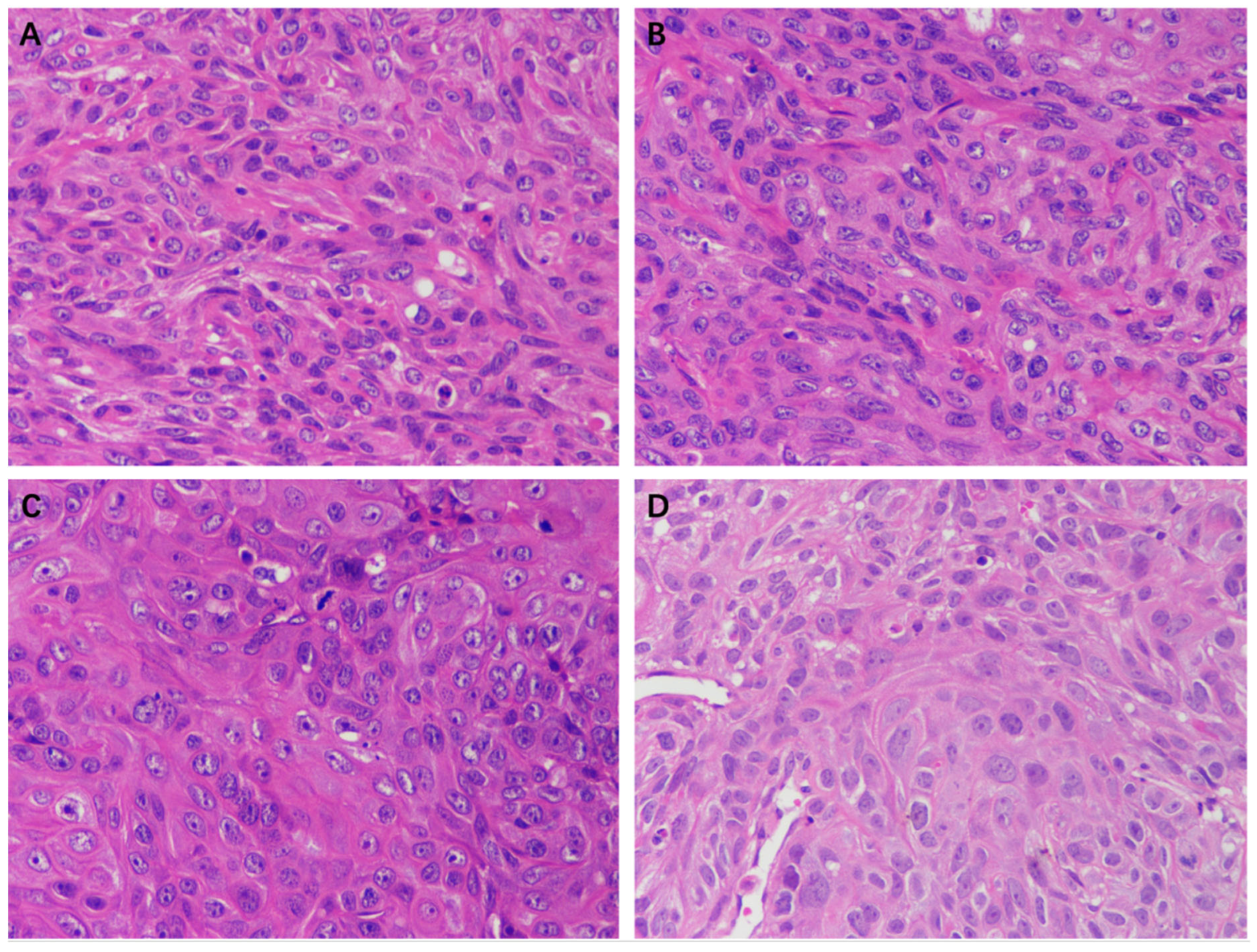

2.5. The Effect of EEP on A431 Cell Xenograft Tumors in Nude Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Propolis Samples and Its Chemical Components Determination

4.2. Antitumor Bioassay

4.3. Differentially Expressed Proteins in A431 Cells Treated with Propolis

4.4. Detection of Relative Gene Expression

4.5. Xenograft Tumor Nude Mice

4.6. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tufaro, A.P.; Chuang, J.C.M.; Prasad, N.; Chuang, A.; Chuang, T.C.; Fischer, A.C. Molecular markers in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 12, 231475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleavenger, J.; Johnson, S.M. Non melanoma skin cancer review. J. Ark. Med. Soc. 2014, 110, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lomas, A.; Leonardi-Bee, J.; Bath-Hextall, F. A systematic review of worldwide incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 166, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halim, A.S.; Ramasenderan, N. High-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC): Challenges and emerging therapies. Asian J. Surg. 2023, 46, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altabbal, S.; Athamnah, K.; Rahma, A.; Wali, A.F.; Eid, A.H.; Iratni, R.; Al Dhaheri, Y. Propolis: A detailed insight of its anticancer molecular mechanisms. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobiş, O. Plants: Sources of diversity in propolis properties. Plants 2022, 11, 2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forma, E.; Bryś, M. Anticancer activity of propolis and its compounds. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasupuleti, V.R.; Sammugam, L.; Ramesh, N.; Gan, S.H. Honey, propolis, and royal jelly: A comprehensive review of their biological actions and health benefits. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 1259510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tian, Y.; Yang, A.; Zhang, C.; Miao, X.; Yang, W. Antitumor effects of poplar propolis on DLBCL SU-DHL-2 cells. Foods 2023, 12, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.K.; Wang, B.J.; Tseng, J.C.; Huang, S.H.; Lin, C.Y.; Kuo, Y.Y.; Hour, T.C.; Chuu, C.P. Combination treatment of docetaxel with caffeic acid phenethyl ester suppresses the survival and the proliferation of docetaxel-resistant prostate cancer cells via induction of apoptosis and metabolism interference. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, C.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, X.; Huang, J.; Xi, J.; Gong, L.; Huang, B.; Zhang, X. Total flavone extract from Ampelopsis megalophylla induces apoptosis in the MCF-7 cell line. Int. J. Oncol. 2021, 58, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezgowiec, J.; Wieczynska, A.; Wieckiewicz, W.; Kulbacka, J.; Saczko, J.; Pachura, N.; Wieckiewicz, M.; Gancarz, R.; Wilk, K.A. Polish propolis—Chemical composition and biological effects in tongue cancer cells and macrophages. Molecules 2020, 25, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frión-Herrera, Y.; Díaz-García, A.; Ruiz-Fuentes, J.; Rodríguez-Sánchez, H.; Sforcin, J.M. The cytotoxic effects of propolis on breast cancer cells involve PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways, mitochondrial membrane potential, and reactive oxygen species generation. Inflammopharmacology 2018, 27, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misir, S.; Aliyazicioglu, Y.; Demir, S.; Turan, I.; Hepokur, C. Effect of Turkish Propolis on miRNA Expression, Cell Cycle, and Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer (MCF-7) Cells. Nutr. Cancer 2019, 72, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nör, F.; Nör, C.; Bento, L.W.; Zhang, Z.; Bretz, W.A.; Nör, J.E. Propolis reduces the stemness of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Oral Biol. 2021, 125, 105087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Frozza, C.O.; Garcia, C.S.C.; Gambato, G.; de Souza, M.D.O.; Salvador, M.; Moura, S.; Padilha, F.F.; Seixas, F.K.; Collares, T.; Borsuk, S.; et al. Chemical characterization, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of Brazilian red propolis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 52, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgharpour, F.; Moghadamnia, A.A.; Zabihi, E.; Namvar, A.E.; Gholinia, H.; Motallebnejad, M.; Nouri, H.R. Iranian propolis efficiently inhibits growth of oral streptococci and cancer cell lines. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žižić, J.B.; Vuković, N.L.; Jadranin, M.B.; Andelković, B.D.; Tešević, V.V.; Kacaniova, M.M.; Sukdolak, S.B.; Marković, S.D. Chemical composition, cytotoxic and antioxidative activities of ethanolic extracts of propolis on HCT-116 cell line. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3001–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khacha-Ananda, S.; Tragoolpua, K.; Chantawannakul, P.; Tragoolpua, Y. Propolis extracts from the northern region of Thailand suppress cancer cell growth through induction of apoptosis pathways. Investig. New Drugs 2016, 34, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, S.; Saieva, L.; Cristaldi, M.; Monteleone, F.; Fontana, S.; Alessandro, R. Label-free quantitative proteomic profiling of colon cancer cells identifies acetyl-CoA carboxylase alpha as antitumor target of Citrus limon-derived nanovesicles. J. Proteom. 2018, 173, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Mai, Z.; Liu, C.; Xu, L.; Xia, C. Label-free-based quantitative proteomic analysis of the inhibition of cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cell proliferation by cucurbitacin B. Phytomedicine 2023, 111, 154669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liao, H.X.; Bando, K.; Nawa, Y.; Fujita, S.; Fujita, K. Label-free monitoring of drug-induced cytotoxicity and its molecular fingerprint by live-cell Raman and autofluorescence imaging. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 10019–10026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasui, W.; Oue, N.; Ito, R.; Kuraoka, K.; Nakayama, H. Search for new biomarkers of gastric cancer through serial analysis of gene expression and its clinical implications. Cancer Sci. 2004, 95, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.; Chen, F. Identification of significant pathways in gastric cancer based on protein-protein interaction networks and cluster analysis. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2012, 35, 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sodek, K.L.; Evangelou, A.I.; Ignatchenko, A.; Agochiya, M.; Brown, T.J.; Ringuette, M.J.; Jurisica, I.; Kislinger, T. Identification of pathways associated with invasive behavior by ovarian cancer cells using multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT). Mol. BioSyst. 2008, 4, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Yang, J.; Zhao, G.; Shen, Z.; Yang, K.; Tian, L.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y. Dysregulation of ferroptosis may involve in the development of non-small-cell lung cancer in Xuanwei area. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 2872–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhondrup, R.; Zhang, X.; Feng, X.; Lobsang, D.; Hua, Q.; Liu, J.; Cuo, Y.; Zhuoma, S.; Duojie, G.; Caidan, S.D.; et al. Proteomic analysis reveals molecular differences in the development of gastric cancer. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 8266544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.J.; Xue, J.M.; Li, J.; Wan, L.H.; Zhu, Y.X. Identification of key genes and pathways of diagnosis and prognosis in cervical cancer by bioinformatics analysis. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2020, 8, e1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Yi, Y.; Liu, F.; Wu, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W. Identification of key pathways and genes in the progression of cervical cancer using bioinformatics analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Hong, H.; Lu, J.; Zhao, X.; Hu, W.; Zhang, S.; Zong, Y.; Mao, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; et al. Prediction of target genes and pathways associated with cetuximab insensitivity in colorectal cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, F.; Shi, Y.; Yang, D.; Xu, M.; Lai, Y.; Liu, Y. Identification of key candidate genes involved in melanoma metastasis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Li, B.; Jia, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, Y.; He, Z. Identification of core genes and pathways in melanoma metastasis via bioinformatics analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Yang, X.; Zhang, P.; Yuan, J.; Dong, Y.; Hosseini, D.K.; Zhou, T.; Sun, H.; He, Z.; Tu, Y.; et al. DNA methylation biomarkers for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivakumaran, N.; Samarakoon, S.R.; Adhikari, A.; Ediriweera, M.K.; Tennekoon, K.H.; Malavige, N.; Thabrew, I.; Shrestha, R.L.S. Cytotoxic and apoptotic effects of govaniadine isolated from corydalis govaniana wall. roots on human breast cancer (MCF-7) Cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3171348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, K.; Kong, S.; Zhao, W. In silico analyses for potential key genes associated with gastric cancer. PeerJ 2018, 6, e6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaheta, R.; Daher, F.; Michaelis, M.; Hasenberg, C.W.; Weich, E.M.; Jonas, D.; Kotchetkov, R.; Doerr, H.W.; Cinatl, J., Jr. Chemoresistance induces enhanced adhesion and transendothelial penetration of neuroblastoma cells by down-regulating NCAM surface expression. BMC Cancer 2006, 6, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baqai, U.; Purwin, T.J.; Bechtel, N.; Chua, V.; Han, A.; Hartsough, E.J.; Kuznetsoff, J.N.; Harbour, J.W.; Aplin, A.E. Multi-omics profiling shows BAP1 loss is associated with upregulated cell adhesion molecules in uveal melanoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2022, 20, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mala, U.; Baral, T.K.; Somasundaram, K. Integrative analysis of cell adhesion molecules in glioblastoma identified prostaglandin F2 receptor inhibitor (PTGFRN) as an essential gene. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tao, Y.; Hua, Q.; Cai, J.; Ye, X.; Li, H. SNORA71A promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 8284576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhou, H.; An, Y.; Shen, K.; Yu, L. Biological effects of corosolic acid as an anti-inflammatory, anti-metabolic syndrome and anti-neoplasic natural compound. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, X.; He, X.; Jia, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, B.; Zhao, J.; Lu, J.; Chen, L.; Dong, Z.; et al. Proteomics reveal the inhibitory mechanism of levodopa against esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 568459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, E.H.; Sung, J.K.; Lee, S.I.; Hong, J.H. Mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase subunit 3 (mtnd3) polymorphisms are associated with gastric cancer susceptibility. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solaini, G.; Sgarbi, G.; Baracca, A. Oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2011, 1807, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, V.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Stoll, G.; Kroemer, G. Oxidative phosphorylation as a potential therapeutic target for cancer therapy. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 146, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.W.; Yuca, E.; Scott, S.S.; Zhao, M.; Arango, N.P.; Pico, C.X.C.; Saridogan, T.; Shariati, M.; Class, C.A.; Bristow, C.A.; et al. Oxidative phosphorylation is a metabolic vulnerability in chemotherapy-resistant triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 5572–5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.L.; Li, F.; Yeo, J.Z.; Yong, K.J.; Bassal, M.A.; Ng, G.H.; Lee, M.Y.; Leong, C.Y.; Tan, H.K.; Wu, C.; et al. New high-throughput screening identifies compounds that reduce viability specifically in liver cancer cells that express high levels of SALL4 by inhibiting oxidative phosphorylation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019, 157, 1615–1629.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zuo, M.; Zeng, L.; Cui, K.; Liu, B.; Yan, C.; Chen, L.; Dong, J.; Shangguan, F.; Hu, W.; et al. OMA1 reprograms metabolism under hypoxia to promote colorectal cancer development. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e50827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Xu, Y.; Kyani, A.; Roy, J.; Dai, L.; Sun, D.; Neamati, N. Multiparameter optimization of oxidative phosphorylation inhibitors for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 3404–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L.B.; Luengo, A.; Danai, L.V.; Bush, L.N.; Diehl, F.F.; Hosios, A.M.; Lau, A.N.; Elmiligy, S.; Malstrom, S.; Lewis, C.A.; et al. Aspartate is an endogenous metabolic limitation for tumour growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 782–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Romero, L.; Alvarez-Suarez, D.E.; Hernández-Lemus, E.; Ponce-Castañeda, M.V.; Tovar, H. The regulatory landscape of retinoblastoma: A pathway analysis perspective. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 220031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Fan, W.; Fang, S. PBK as a potential biomarker associated with prognosis of glioblastoma. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 70, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, R.; Li, N.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Yuan, F.; Sun, Q.; Liu, B.; Chen, Q. Identification of core biomarkers associated with outcome in glioma: Evidence from bioinformatics analysis. Dis. Markers 2018, 2018, 3215958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y.; Ren, H.; Shen, Y.; Bi, F.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Alter between gut bacteria and blood metabolites and the anti-tumor effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in breast cancer. BMC Microbiol. 2020, 20, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Wang, Y.; Lu, M.; Zhan, X.; Zhou, T.; Li, B.; Zhan, X. Quantitative analysis of proteome in non-functional pituitary adenomas: Clinical relevance and potential benefits for the patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Tong, M.; Yu, R. Application of personalized differential expression analysis in human cancer proteome. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Beyer, A.; Aebersold, R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell 2016, 165, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Q.; Shi, Z.; Chambers, M.C.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Shaddox, K.F.; Kim, S.; et al. Proteogenomic characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2014, 513, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradner, J.E.; Hnisz, D.; Young, R.A. Transcriptional addiction in cancer. Cell 2017, 168, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Gutierrez, L.; Bordonaro, M.; Russo, D.; Anzelmi, F.; Hooven, J.T.; Cerra, C.; Lazarova, D.L. Effects of propolis and gamma-cyclodextrin on intestinal neoplasia in normal weight and obese mice. Cancer Med. 2016, 5, 2448–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desamero, M.J.; Kakuta, S.; Tang, Y.; Chambers, J.K.; Uchida, K.; Estacio, M.A.; Cervancia, C.; Kominami, Y.; Ushio, H.; Nakayama, J.; et al. Tumor-suppressing potential of stingless bee propolis in in vitro and in vivo models of differentiated-type gastric adenocarcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wang, D.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, D. The immunological enhancement activity of propolis flavonoids liposome in vitro and in vivo. J. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 483513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 24283-2018; Propolis. National Standards of People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Cao, Y.; Ding, W.; Liu, C. Unraveling the metabolite signature of endophytic Bacillus velezensis strain showing defense response towards Fusarium oxysporum. Agronomy 2021, 11, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oršolić, N. A review of propolis antitumor action in vivo and in vitro. JAAS 2010, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Name | Formula | Molecular Weight | Retention Time (min) | m/z | Relative Quantitative Value | Polarity Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,5,8-Trihydroxy-9-oxo-9H-xanthen-3-yl β-D-glucopyranoside | C19H18O11 | 422.08375 | 1.31 | 421.07648 | 39,349,735.26 | negative |

| 2 | D-ribose 5-phosphate | C5H11O8P | 230.01908 | 1.311 | 229.0118 | 43,826,332.25 | negative |

| 3 | D-Mannose 6-phosphate | C6H13O9P | 260.02992 | 1.318 | 259.02264 | 349,455,529.4 | negative |

| 4 | Galacturonic acid | C6H10O7 | 194.0423 | 1.329 | 193.03502 | 8,590,476,535 | negative |

| 5 | N-Acetyl-α-D-glucosamine 1-phosphate | C8H16NO9P | 301.05628 | 1.334 | 300.04898 | 31,064,500.87 | negative |

| 6 | D-Saccharic acid | C6H10O8 | 210.0372 | 1.347 | 209.02992 | 512,353,580.7 | negative |

| 7 | Gluconic acid | C6H12O7 | 196.05746 | 1.358 | 195.05019 | 6,478,000,924 | negative |

| 8 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine | C17H27N3O17P2 | 607.08204 | 1.367 | 606.07477 | 75,450,606.66 | negative |

| 9 | D-(−)-Fructose | C6H12O6 | 180.06258 | 1.375 | 179.05521 | 2,010,181,033 | negative |

| 10 | N-Acetylneuraminic acid | C11H19NO9 | 309.10545 | 1.383 | 308.09818 | 67,763,775.54 | negative |

| 11 | L-(+)-Tartaric acid | C4H6O6 | 150.01571 | 1.405 | 149.00844 | 762,277,603.7 | negative |

| 12 | Glucuronic acid-3,6-lactone | C6H8O6 | 176.03153 | 1.419 | 175.02422 | 433,003,996.6 | negative |

| 13 | Sucrose | C12H22O11 | 342.11616 | 1.437 | 341.10873 | 16,004,974,387 | negative |

| 14 | D-Raffinose | C18H32O16 | 504.16905 | 1.439 | 503.16208 | 1,558,022,103 | negative |

| 15 | δ-Gluconic acid δ-lactone | C6H10O6 | 178.04704 | 1.563 | 177.03976 | 165,652,129.9 | negative |

| 16 | Uric acid | C5H4N4O3 | 168.02751 | 1.886 | 167.02023 | 4,413,870,356 | negative |

| 17 | D-α-Hydroxyglutaric acid | C5H8O5 | 148.03653 | 2.092 | 147.02925 | 149,585,529.5 | negative |

| 18 | Xanthine | C5H4N4O2 | 152.03277 | 2.181 | 151.02548 | 337,332,340.5 | negative |

| 19 | Uridine | C9H12N2O6 | 244.0697 | 2.415 | 243.06268 | 1,652,833,848 | negative |

| 20 | N-Acetyl-DL-glutamic acid | C7H11NO5 | 189.06346 | 2.463 | 188.05618 | 53,573,049.69 | negative |

| 21 | Ascorbic acid | C6H8O6 | 176.03149 | 2.814 | 175.02422 | 205,503,907.6 | negative |

| 22 | 2,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O4 | 154.02601 | 3.36 | 153.01874 | 92,941,295.62 | negative |

| 23 | N-(4-chlorophenyl)-N′-cyclohexylthiourea | C13H17ClN2S | 268.08092 | 3.659 | 267.07364 | 271,608,391.5 | negative |

| 24 | 2-Amino-3-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)propanoic acid | C10H13NO4 | 211.08417 | 4.223 | 210.07693 | 40,438,679.16 | negative |

| 25 | Xanthosine | C10H12N4O6 | 284.07619 | 4.747 | 283.06891 | 25,698,102.52 | negative |

| 26 | Methylsuccinic acid | C5H8O4 | 132.04211 | 4.789 | 131.03484 | 147,365,715.6 | negative |

| 27 | Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | 170.0212 | 4.884 | 169.01393 | 542,974,125 | negative |

| 28 | Thymidine | C10H14N2O5 | 242.09074 | 4.895 | 241.08331 | 88,919,605.24 | negative |

| 29 | 3,4,5-trihydroxycyclohex-1-ene-1-carboxylic acid | C7H10O5 | 174.0523 | 4.907 | 173.04523 | 49,978,794.34 | negative |

| 30 | 1-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-2-(3,5-dimethoxyphenyl)propan-1-one | C17H18O5 | 302.11583 | 4.93 | 301.10855 | 43,916,324.75 | negative |

| 31 | 5-Sulfosalicylic acid | C7H6O6S | 217.98848 | 4.937 | 216.9812 | 33,337,560.45 | negative |

| 32 | 3′,4′-Dihydroxyphenylacetone | C9H10O3 | 166.0626 | 4.938 | 165.05533 | 255,487,284.2 | negative |

| 33 | Porphobilinogen | C10H14N2O4 | 226.09543 | 4.963 | 225.08815 | 20,599,303.66 | negative |

| 34 | D-(−)-Quinic acid | C7H12O6 | 192.06308 | 5.067 | 191.0558 | 687,769,173.6 | negative |

| 35 | 2,3-Dihydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O4 | 154.02606 | 5.072 | 153.01874 | 1,430,101,121 | negative |

| 36 | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaric acid | C6H10O5 | 162.05219 | 5.136 | 161.04492 | 1,232,391,129 | negative |

| 37 | Vanillyl alcohol | C8H10O3 | 154.0624 | 5.155 | 153.05511 | 206,029,853 | negative |

| 38 | L-Tyrosine methyl ester | C10H13NO3 | 195.08926 | 5.159 | 194.08197 | 216,011,260.4 | negative |

| 39 | Phenylglyoxylic acid | C8H6O3 | 150.03111 | 5.166 | 149.02383 | 154,372,170.5 | negative |

| 40 | Esculin | C15H16O9 | 340.08006 | 5.172 | 339.07278 | 51,031,924.39 | negative |

| 41 | 2-Isopropylmalic acid | C7H12O5 | 176.06807 | 5.441 | 175.06079 | 310,134,000.4 | negative |

| 42 | 4-((5-(4-Nitrophenyl)oxazol-2-yl)amino)benzonitrile | C16H10N4O3 | 306.07402 | 5.445 | 305.06674 | 343,517,763.8 | negative |

| 43 | Miquelianin | C21H18O13 | 478.07498 | 5.464 | 477.06772 | 28,072,478.49 | negative |

| 44 | Quercetin-3β-D-glucoside | C21H20O12 | 464.09608 | 5.483 | 463.08881 | 197,183,482.7 | negative |

| 45 | 3-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 164.04692 | 5.521 | 163.03963 | 53,776,573,353 | negative |

| 46 | Hematoxylin | C16H14O6 | 302.07832 | 5.539 | 301.07104 | 3,032,439,830 | negative |

| 47 | Gentisic acid | C7H6O4 | 154.02598 | 5.542 | 153.01869 | 1,126,817,012 | negative |

| 48 | Agnuside | C22H26O11 | 466.14775 | 5.545 | 465.14047 | 78,804,038.52 | negative |

| 49 | Myricetin | C15H10O8 | 318.03764 | 5.554 | 317.03036 | 252,777,241.4 | negative |

| 50 | Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 180.04162 | 5.562 | 179.03435 | 16,033,774,255 | negative |

| 51 | 3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid | C9H10O3 | 166.06227 | 5.583 | 165.05499 | 511,602,130.2 | negative |

| 52 | Suberic acid | C8H14O4 | 174.08878 | 5.617 | 173.0815 | 805,556,199.4 | negative |

| 53 | trans-Cinnamic acid | C9H8O2 | 148.05183 | 5.623 | 147.04456 | 299,470,310.6 | negative |

| 54 | 11-Dehydro thromboxane B2 | C20H32O6 | 368.22037 | 5.64 | 367.21292 | 3,259,236,011 | negative |

| 55 | Citrinin | C13H14O5 | 250.08414 | 5.709 | 249.07686 | 234,803,880.5 | negative |

| 56 | Isorhapontigenin | C15H14O4 | 258.08848 | 5.722 | 257.08121 | 81,038,331.56 | negative |

| 57 | DL-4-Hydroxyphenyllactic acid | C9H10O4 | 182.05747 | 5.728 | 181.05019 | 365,233,039.2 | negative |

| 58 | 3,8,9-trihydroxy-10-propyl-3,4,5,8,9,10-hexahydro-2H-oxecin-2-one | C12H20O5 | 244.1311 | 5.745 | 243.12383 | 213,168,051.7 | negative |

| 59 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-2-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)chroman-4-one | C16H14O6 | 302.07762 | 5.767 | 301.07034 | 1,212,404,197 | negative |

| 60 | Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 302.04262 | 5.774 | 301.03534 | 26,894,567,188 | negative |

| 61 | Luteolin | C15H10O6 | 286.04916 | 5.82 | 285.0419 | 1,272,812,181 | negative |

| 62 | Naringenin | C15H12O5 | 272.06883 | 5.948 | 271.06155 | 2.187 × 1011 | negative |

| 63 | β-Estradiol-17β-glucuronide | C24H32O8 | 448.21037 | 5.95 | 447.20309 | 389,513,176.1 | negative |

| 64 | Aflatoxin G2 | C17H14O7 | 330.07296 | 5.965 | 329.06567 | 877,430,305.3 | negative |

| 65 | Monobutyl phthalate | C12H14O4 | 222.08911 | 6.124 | 221.08183 | 4,535,327,931 | negative |

| 66 | Mycophenolic acid | C17H20O6 | 320.12593 | 6.188 | 319.11865 | 56,348,359.96 | negative |

| 67 | Salvinorin B | C21H26O7 | 390.16923 | 6.221 | 389.16232 | 35,236,148.01 | negative |

| 68 | Dodecanedioic acid | C12H22O4 | 230.1519 | 6.424 | 229.14462 | 25,219,452.38 | negative |

| 69 | Aldosterone | C21H28O5 | 360.19396 | 6.538 | 359.18668 | 155,818,216.9 | negative |

| 70 | Corchorifatty acid F | C18H32O5 | 328.22511 | 6.568 | 327.21783 | 1,609,573,692 | negative |

| 71 | N2-(4-iodophenyl)-1,3,5-triazine-2,4-diamine | C9H8IN5 | 312.98237 | 6.589 | 311.9751 | 50,086,503.07 | negative |

| 72 | 2,3-Dinor-8-epi-prostaglandin F2α | C18H30O5 | 326.20988 | 6.609 | 325.20261 | 74,071,657.03 | negative |

| 73 | Trolox | C14H18O4 | 250.12082 | 6.639 | 499.23444 | 12,254,171,786 | negative |

| 74 | Genistein | C15H10O5 | 270.05308 | 6.658 | 269.04581 | 53,946,618,740 | negative |

| 75 | (±)9(10)-DiHOME | C18H34O4 | 314.24586 | 6.658 | 313.23859 | 1,801,802,573 | negative |

| 76 | [1,1′-biphenyl]-2,2′-dicarboxylic acid | C14H10O4 | 242.05804 | 6.699 | 241.05077 | 363,776,879.9 | negative |

| 77 | Glycocholic acid | C26H43NO6 | 465.3098 | 6.753 | 464.30252 | 31,784,139.83 | negative |

| 78 | Glycitein | C16H12O5 | 284.06795 | 6.758 | 283.06067 | 12,479,803,653 | negative |

| 79 | Gibberellin A4 | C19H24O5 | 332.16264 | 6.803 | 331.15536 | 935,893,979.2 | negative |

| 80 | 4-(octyloxy)benzoic acid | C15H22O3 | 250.15718 | 6.852 | 249.1499 | 9,593,885.513 | negative |

| 81 | (±)-Abscisic acid | C15H20O4 | 264.13643 | 6.963 | 263.12915 | 2,145,442,724 | negative |

| 82 | Tetradecanedioic acid | C14H26O4 | 258.18339 | 7.01 | 257.17612 | 24,368,922.87 | negative |

| 83 | 2-Hydroxymyristic acid | C14H28O3 | 244.2034 | 7.098 | 243.19612 | 262,979,901.2 | negative |

| 84 | 13(S)-HOTrE | C18H30O3 | 294.21966 | 7.48 | 293.21237 | 113,609,783 | negative |

| 85 | Pentobarbital-d5 | C11H13[2]H5N2O3 | 231.16231 | 7.484 | 230.15503 | 4,925,637.941 | negative |

| 86 | 15-keto Prostaglandin E1 | C20H32O5 | 352.22508 | 7.857 | 351.21777 | 6,575,446.425 | negative |

| 87 | 16-Hydroxyhexadecanoic acid | C16H32O3 | 272.23472 | 7.871 | 271.22745 | 609,305,517.6 | negative |

| 88 | Protoporphyrin IX | C34H34N4O4 | 562.25709 | 8.059 | 561.24982 | 7,107,790.257 | negative |

| 89 | 18-β-Glycyrrhetinic acid | C30H46O4 | 470.3397 | 8.84 | 469.33243 | 11,661,934.32 | negative |

| 90 | Arachidic Acid | C20H40O2 | 312.30324 | 9.988 | 311.29596 | 11,584,703.86 | negative |

| 91 | Docosanoic Acid | C22H44O2 | 340.33436 | 10.655 | 339.32709 | 5,918,139.419 | negative |

| 92 | 11(Z),14(Z)-Eicosadienoic Acid | C20H36O2 | 308.2715 | 10.673 | 307.26422 | 8,254,456.223 | negative |

| 93 | Ursolic acid | C30H48O3 | 456.36055 | 10.725 | 455.35327 | 7,204,655.792 | negative |

| 94 | Lignoceric Acid | C24H48O2 | 368.36568 | 10.905 | 367.3584 | 20,009,501.76 | negative |

| 95 | 13Z,16Z-Docosadienoic Acid | C22H40O2 | 336.30278 | 11.625 | 335.2955 | 41,592,258.77 | negative |

| 96 | Stearic acid | C18H36O2 | 284.27189 | 11.678 | 283.26462 | 21,499,099.39 | negative |

| 97 | N-[2-chloro-6-(trifluoromethoxy)phenyl]-2,2-dimethylpropanamide | C12H13ClF3NO2 | 295.05873 | 1.268 | 296.06601 | 165,911,372.3 | positive |

| 98 | Choline | C5H13NO | 103.09958 | 1.274 | 104.10686 | 3,351,190,589 | positive |

| 99 | Glucose 1-phosphate | C6H13O9P | 260.02959 | 1.332 | 261.03687 | 467,937,507.5 | positive |

| 100 | Muramic acid | C9H17NO7 | 251.10009 | 1.337 | 252.10736 | 1,505,589,223 | positive |

| 101 | Betaine | C5H11NO2 | 117.07897 | 1.342 | 118.08624 | 3,172,931,864 | positive |

| 102 | 4-Acetamidobutanoic acid | C6H11NO3 | 145.0737 | 1.379 | 146.08098 | 225,826,130.1 | positive |

| 103 | Acetylcholine | C7H15NO2 | 145.11022 | 1.437 | 146.11749 | 3,685,256,761 | positive |

| 104 | 1-Aminocyclohexanecarboxylic acid | C7H13NO2 | 143.09483 | 1.438 | 144.10211 | 337,928,527.3 | positive |

| 105 | Pipecolic acid | C6H11NO2 | 129.07901 | 1.495 | 130.08629 | 196,772,335.8 | positive |

| 106 | N-Acetylhistamine | C7H11N3O | 153.09026 | 1.76 | 154.09753 | 103,842,799.2 | positive |

| 107 | 4-Guanidinobutyric acid | C5H11N3O2 | 145.08527 | 1.843 | 146.09254 | 321,810,960.4 | positive |

| 108 | Nicotinic acid | C6H5NO2 | 123.03225 | 1.945 | 124.03953 | 839,395,599.9 | positive |

| 109 | Nicotinamide | C6H6N2O | 122.0483 | 2.071 | 123.05557 | 569,720,151.5 | positive |

| 110 | 6-Hydroxynicotinic acid | C6H5NO3 | 139.02706 | 2.112 | 140.03433 | 1,036,882,714 | positive |

| 111 | Pyrrole-2-carboxylic acid | C5H5NO2 | 111.03238 | 2.12 | 112.03966 | 479,797,100.7 | positive |

| 112 | L-Pyroglutamic acid | C5H7NO3 | 129.0428 | 2.175 | 130.05005 | 620,786,771.7 | positive |

| 113 | 3-isopropoxy-4-morpholinocyclobut-3-ene-1,2-dione | C11H15NO4 | 225.1004 | 2.395 | 226.10768 | 67,026,578.08 | positive |

| 114 | Uracil | C4H4N2O2 | 112.02752 | 2.441 | 113.0348 | 870,107,158.9 | positive |

| 115 | Adenine | C5H5N5 | 135.05466 | 3.527 | 136.06194 | 330,830,026.4 | positive |

| 116 | Adenosine | C10H13N5O4 | 267.09682 | 3.529 | 268.1041 | 1,427,095,688 | positive |

| 117 | Inosine | C10H12N4O5 | 268.08094 | 3.964 | 269.08823 | 257,548,392.1 | positive |

| 118 | Hypoxanthine | C5H4N4O | 136.03859 | 3.965 | 137.04587 | 887,426,643.9 | positive |

| 119 | Diethyl phosphate | C4H11O4P | 154.03959 | 3.974 | 155.04686 | 399,273,696.2 | positive |

| 120 | DL-Stachydrine | C7H13NO2 | 143.09484 | 4.175 | 144.10211 | 1,831,709,107 | positive |

| 121 | D(−)-Amygdalin | C20H27NO11 | 457.1595 | 4.838 | 458.16678 | 209,671,201.6 | positive |

| 122 | N-[3-(2-methyl-4-pyrimidinyl)phenyl]-1,3-benzothiazole-2-carboxamide | C19H14N4OS | 346.08824 | 4.856 | 347.09552 | 24,561,559.93 | positive |

| 123 | 1-methyl-2-oxo-1,2-dihydroquinolin-4-yl N,N-dimethylcarbamate | C13H14N2O3 | 246.10079 | 4.876 | 247.10806 | 37,336,553.33 | positive |

| 124 | N-[1-(4-methoxy-2-oxo-2H-pyran-6-yl)-2-methylbutyl]acetamide | C13H19NO4 | 253.1315 | 4.899 | 254.13878 | 63,994,227.66 | positive |

| 125 | 2-(tert-butyl)-6,7-dimethoxy-4H-3,1-benzoxazin-4-one | C14H17NO4 | 263.11608 | 4.901 | 264.12335 | 185,237,827.6 | positive |

| 126 | L-Dopa | C9H11NO4 | 197.06899 | 4.906 | 198.07626 | 140,151,015.2 | positive |

| 127 | 2-(2-acetyl-3,5-dihydroxyphenyl)acetic acid | C10H10O5 | 210.053 | 4.926 | 211.06032 | 98,428,683 | positive |

| 128 | 1-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)ethan-1-one oxime | C10H13NO3 | 195.08971 | 4.933 | 196.09698 | 614,007,207 | positive |

| 129 | 4-Hydroxybenzaldehyde | C7H6O2 | 122.03695 | 4.95 | 123.0442 | 432,952,790.1 | positive |

| 130 | Retrorsine | C18H25NO6 | 351.16835 | 4.971 | 352.17566 | 454,873,409.5 | positive |

| 131 | N-(5-methylisoxazol-3-yl)-N’-[4-(trifluoromethyl)-3-pyridyl]urea | C11H9F3N4O2 | 286.06688 | 4.99 | 287.07416 | 26,800,545.08 | positive |

| 132 | 2-[(carboxymethyl)(methyl)amino]-5-methoxybenzoic acid | C11H13NO5 | 239.07959 | 5.014 | 240.08687 | 364,769,903.8 | positive |

| 133 | 5-[(2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino]-2-(2-methoxyethoxy)benzoic acid | C17H17NO5 | 315.11092 | 5.047 | 316.11819 | 71,187,584.76 | positive |

| 134 | 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)acetamide | C8H9NO3 | 167.05841 | 5.09 | 168.06569 | 160,810,937.1 | positive |

| 135 | 3-Methoxybenzaldehyde | C8H8O2 | 136.05248 | 5.141 | 137.05975 | 1,453,566,975 | positive |

| 136 | cis,cis-Muconic acid | C6H6O4 | 142.02675 | 5.227 | 143.03403 | 370,439,328.5 | positive |

| 137 | Xanthurenic acid | C10H7NO4 | 205.03758 | 5.245 | 206.04486 | 142,669,582.9 | positive |

| 138 | 3-Methylcrotonylglycine | C7H11NO3 | 157.074 | 5.255 | 158.08128 | 1,115,733,525 | positive |

| 139 | 3-hydroxy-3,4-bis[(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]oxolan-2-one | C20H22O7 | 374.13646 | 5.256 | 375.14374 | 53,726,456.67 | positive |

| 140 | 5,6-dimethyl-4-oxo-4H-pyran-2-carboxylic acid | C8H8O4 | 168.0423 | 5.292 | 169.04958 | 265,935,155.1 | positive |

| 141 | 8-Hydroxyquinoline | C9H7NO | 145.05283 | 5.294 | 146.0601 | 260,410,244.6 | positive |

| 142 | Kynurenic acid | C10H7NO3 | 189.04259 | 5.32 | 190.04987 | 1,905,007,525 | positive |

| 143 | Safrole | C10H10O2 | 162.06841 | 5.32 | 163.07619 | 212,114,032.4 | positive |

| 144 | Bergapten | C12H8O4 | 216.04233 | 5.336 | 217.04961 | 134,452,483.5 | positive |

| 145 | Isoferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 194.05797 | 5.342 | 195.06525 | 2,726,827,967 | positive |

| 146 | 1-(4-butylphenyl)-3-(dimethylamino)propan-1-one hydrochloride | C15H23NO | 233.17806 | 5.354 | 234.18533 | 95,286,786.45 | positive |

| 147 | 2-Phenylglycine | C8H9NO2 | 151.06335 | 5.394 | 152.07062 | 248,042,836.8 | positive |

| 148 | N1-(2,3-dihydro-1,4-benzodioxin-6-yl)acetamide | C10H11NO3 | 193.07393 | 5.394 | 194.08121 | 470,764,198.3 | positive |

| 149 | Isohomovanillic acid | C9H10O4 | 182.05789 | 5.476 | 183.06517 | 632,371,956.6 | positive |

| 150 | Resveratrol | C14H12O3 | 228.0786 | 5.495 | 229.08588 | 127,433,383.6 | positive |

| 151 | Vanillin | C8H8O3 | 152.04734 | 5.5 | 153.05461 | 7,449,671,173 | positive |

| 152 | 2-(2-hydroxy-3-methylbutanamido)-4-methylpentanoic acid | C11H21NO4 | 231.14748 | 5.507 | 232.15465 | 16,473,889.02 | positive |

| 153 | 4-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 164.04727 | 5.509 | 165.05449 | 10,555,435,607 | positive |

| 154 | 7-hydroxy-3-phenyl-4H-chromen-4-one | C15H10O3 | 238.06268 | 5.518 | 239.06996 | 48,729,023.77 | positive |

| 155 | Apocynin | C9H10O3 | 166.06305 | 5.52 | 167.07033 | 570,626,404.7 | positive |

| 156 | 4-Phenylbutyric acid | C10H12O2 | 164.08381 | 5.539 | 165.09109 | 205,439,194.1 | positive |

| 157 | Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 194.05799 | 5.545 | 195.06525 | 75,400,334,073 | positive |

| 158 | 3-benzyl-4-hydroxy-5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-2,5-dihydrofuran-2-one | C17H14O4 | 282.08907 | 5.564 | 283.09634 | 91,049,837.1 | positive |

| 159 | Trifolin | C21H20O11 | 448.10082 | 5.574 | 449.10809 | 207,852,942.9 | positive |

| 160 | 2-[5-(2-hydroxypropyl)oxolan-2-yl]propanoic acid | C10H18O4 | 202.1205 | 5.618 | 203.12778 | 89,488,627.25 | positive |

| 161 | Isoeugenyl acetate | C12H14O3 | 206.09445 | 5.678 | 207.10175 | 107,711,395.8 | positive |

| 162 | (5E)-7-methylidene-10-oxo-4-(propan-2-yl)undec-5-enoic acid | C15H24O3 | 252.17266 | 5.712 | 253.17993 | 1,402,040,442 | positive |

| 163 | (2S)-2-(2-hydroxypropan-2-yl)-2H,3H,7H-furo[3,2-g]chromen-7-one | C14H14O4 | 246.0892 | 5.717 | 247.09648 | 1,605,550,194 | positive |

| 164 | 3,4-Dimethoxycinnamic acid | C11H12O4 | 208.0736 | 5.72 | 209.08086 | 63,552,367,246 | positive |

| 165 | Biochanin A | C16H12O5 | 284.06853 | 5.722 | 285.07581 | 5,527,495,198 | positive |

| 166 | 4-Methoxycinnamaldehyde | C10H10O2 | 162.06807 | 5.722 | 163.07535 | 1,922,721,932 | positive |

| 167 | Piceatannol | C14H12O4 | 244.07353 | 5.735 | 245.08081 | 268,412,733.9 | positive |

| 168 | Hesperetin | C16H14O6 | 302.07887 | 5.748 | 303.08615 | 232,819,296.3 | positive |

| 169 | 7-hydroxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one | C16H12O4 | 268.07356 | 5.759 | 269.08084 | 1,376,762,031 | positive |

| 170 | Galangin | C15H10O5 | 270.05278 | 5.766 | 271.06006 | 18,105,451,784 | positive |

| 171 | (2R)-2-[(2R,5S)-5-[(2S)-2-hydroxybutyl]oxolan-2-yl]propanoic acid | C11H20O4 | 216.13623 | 5.791 | 217.14351 | 217,544,557.8 | positive |

| 172 | (1E,4Z,6E)-5-hydroxy-1,7-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)hepta-1,4,6-trien-3-one | C19H16O4 | 308.10472 | 5.809 | 309.112 | 46,531,520.91 | positive |

| 173 | 3-hydroxy-4-methoxy-9H-xanthen-9-one | C14H10O4 | 242.05791 | 5.827 | 243.06519 | 295,235,024 | positive |

| 174 | Daidzin | C21H20O9 | 416.11073 | 5.835 | 417.11801 | 638,726,156.6 | positive |

| 175 | 4,7-dimethoxy-1H-phenalen-1-one | C15H12O3 | 240.07863 | 5.844 | 241.08591 | 3,312,421,173 | positive |

| 176 | Naringeninchalcone | C15H12O5 | 272.06831 | 5.952 | 273.07559 | 18,351,009,032 | positive |

| 177 | 12-Oxo phytodienoic acid | C18H28O3 | 292.20342 | 5.963 | 293.21069 | 2,505,657,284 | positive |

| 178 | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | 286.04823 | 5.967 | 287.05551 | 9,006,992,981 | positive |

| 179 | 2,4-Dimethylbenzaldehyde | C9H10O | 134.0734 | 5.985 | 117.07014 | 1,223,537,063 | positive |

| 180 | 4-Methoxycinnamic acid | C10H10O3 | 178.06309 | 6.002 | 179.0703 | 6,932,438,506 | positive |

| 181 | (+)-ar-Turmerone | C15H20O | 216.15139 | 6.016 | 217.15866 | 1,027,389,042 | positive |

| 182 | Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 270.05278 | 6.024 | 271.06006 | 14,095,816,138 | positive |

| 183 | 6-Pentyl-2H-pyran-2-one | C10H14O2 | 166.09939 | 6.049 | 167.10667 | 903,441,178.6 | positive |

| 184 | Methyl cinnamate | C10H10O2 | 162.06808 | 6.071 | 163.07535 | 455,777,480.5 | positive |

| 185 | 4-Phenyl-3-buten-2-one | C10H10O | 146.07324 | 6.076 | 147.08052 | 483,099,106.7 | positive |

| 186 | 5-(2,5-dihydroxyhexyl)oxolan-2-one | C10H18O4 | 202.12056 | 6.094 | 203.12785 | 98,842,367.03 | positive |

| 187 | Cardamomin | C16H14O4 | 270.08916 | 6.121 | 271.09644 | 17,850,179,874 | positive |

| 188 | Citral | C10H16O | 152.12017 | 6.184 | 153.12744 | 3,164,365,769 | positive |

| 189 | Formononetin | C16H12O4 | 268.07366 | 6.228 | 269.08093 | 5,354,174,356 | positive |

| 190 | Rhamnetin | C16H12O7 | 316.05788 | 6.28 | 317.06516 | 5,100,142,040 | positive |

| 191 | 3-Methoxyflavone | C16H12O3 | 252.07872 | 6.313 | 253.086 | 477,044,431 | positive |

| 192 | trans-Cinnamaldehyde | C9H8O | 132.05778 | 6.316 | 133.06496 | 3,462,748,945 | positive |

| 193 | 5-hydroxy-6,7-dimethoxy-2-phenyl-4H-chromen-4-one | C17H14O5 | 298.08406 | 6.338 | 299.09134 | 474,558,537.9 | positive |

| 194 | 4-Hydroxybenzophenone | C13H10O2 | 198.06813 | 6.349 | 199.07541 | 858,164,155.1 | positive |

| 195 | Sakuranetin | C16H14O5 | 286.08367 | 6.398 | 287.09094 | 10,055,131,651 | positive |

| 196 | Veratrole | C8H10O2 | 138.06813 | 6.414 | 139.07541 | 1,285,393,336 | positive |

| 197 | Pinocembrin | C15H12O4 | 256.07356 | 6.416 | 257.08084 | 19,143,801,362 | positive |

| 198 | Nootkatone | C15H22O | 218.16721 | 6.436 | 219.17448 | 7,475,410,243 | positive |

| 199 | 1-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-4-yl benzoate | C16H12O3 | 252.07872 | 6.481 | 253.086 | 86,170,158.6 | positive |

| 200 | 3,14-dihydro-15-keto-tetranor Prostaglandin E2 | C16H26O5 | 298.17794 | 6.505 | 299.18539 | 363,566,952.2 | positive |

| 201 | Carvone | C10H14O | 150.10456 | 6.555 | 151.11183 | 1,494,122,211 | positive |

| 202 | Chrysin | C15H10O4 | 254.05795 | 6.577 | 255.06523 | 53,403,620,396 | positive |

| 203 | Coenzyme Q2 | C19H26O4 | 318.18284 | 6.717 | 319.19012 | 250,369,688.1 | positive |

| 204 | WNK | C21H30N6O5 | 446.22838 | 6.72 | 447.23566 | 49,336,245.15 | positive |

| 205 | Wogonin | C16H12O5 | 284.06853 | 6.735 | 285.07581 | 16,003,176,213 | positive |

| 206 | 1,7,8-trihydroxy-3-methyl-1,2,3,4,7,12-hexahydrotetraphen-12-one | C19H18O4 | 310.12057 | 6.884 | 311.1279 | 66,568,647.86 | positive |

| 207 | 4-methoxy-6-(prop-2-en-1-yl)-2H-1,3-benzodioxole | C11H12O3 | 192.07906 | 6.95 | 193.08633 | 6,455,924.178 | positive |

| 208 | 9-Oxo-ODE | C18H30O3 | 294.21946 | 7 | 295.22672 | 8,284,510,598 | positive |

| 209 | (2R)-5-hydroxy-7-methoxy-2-phenyl-3,4-dihydro-2H-1-benzopyran-4-one | C16H14O4 | 270.08928 | 7.074 | 271.09656 | 638,934,307.1 | positive |

| 210 | (−)-Caryophyllene oxide | C15H24O | 220.18288 | 7.191 | 221.19016 | 4,440,500,049 | positive |

| 211 | 9-Oxo-10(E),12(E)-octadecadienoic acid | C18H30O3 | 294.21948 | 7.935 | 295.22681 | 10,127,470,520 | positive |

| 212 | DL-Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine | C40H80NO8P | 733.56401 | 10.387 | 734.57129 | 171,680,834.5 | positive |

| 213 | Betulin | C30H50O2 | 442.38181 | 10.556 | 443.38919 | 131,107,308.5 | positive |

| 214 | Palmitoyl sphingomyelin | C39H79N2O6P | 702.56926 | 11.002 | 703.57654 | 741,892,482.6 | positive |

| Protein ID | Name | p | Regulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| O75911 | Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase 3 | 0.000141468 | down |

| Q9UPY5 | Cystine/glutamate transporter | 0.000659187 | up |

| Q6IBA0 | NADH dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 5, 15 kDa (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase) | 0.00094246 | down |

| A0A024RDX4 | ATP-dependent (S)-NAD(P)H-hydrate dehydratase | 0.001028075 | up |

| Q9Y4K0 | Lysyl oxidase homolog 2 | 0.001568804 | up |

| Q03405 | Urokinase plasminogen activator surface receptor | 0.001635932 | up |

| Q96JY6 | PDZ and LIM domain protein 2 | 0.001648702 | up |

| A0A024R084 | Stromal cell-derived factor 4, isoform CRA_c | 0.001660675 | down |

| A0A0A6YYF2 | HCG1811249, isoform CRA_e | 0.001700981 | up |

| B3KN79 | cDNA FLJ13894 fis, clone THYRO1001671, highly similar to 59 kDa 2-5-oligoadenylate synthetase-like protein | 0.002052659 | down |

| A6NCE7 | Microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3 beta 2 | 0.002064172 | up |

| Q9BXY0 | Protein MAK16 homolog | 0.003155254 | down |

| Q14139 | Ubiquitin conjugation factor E4 A | 0.003259227 | up |

| A8K878 | Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor | 0.003402074 | up |

| Q9NQC3 | Reticulon-4 | 0.003468251 | up |

| Q9Y316 | Protein MEMO1 | 0.003479756 | down |

| E7EPT4 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial | 0.003643833 | down |

| P18827 | Syndecan-1 | 0.004028676 | up |

| P49821 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial | 0.004095327 | down |

| A8K0B9 | rRNA adenine N(6)-methyltransferase | 0.004645847 | down |

| A0A3B3ISF9 | Endothelin-converting enzyme 1 | 0.004659358 | down |

| Q96PU5 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase NEDD4-like | 0.004703096 | down |

| Q9NX12 | cDNA FLJ20496 fis, clone KAT08729 | 0.005418258 | up |

| Q53HG1 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 12 (Fragment) | 0.005954737 | down |

| Q14684 | Ribosomal RNA processing protein 1 homolog B | 0.006713584 | down |

| Q04828 | Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C1 | 0.006731072 | up |

| Q9GZM7 | Tubulointerstitial nephritis antigen-like | 0.007059725 | up |

| P22223 | Cadherin-3 | 0.00794582 | up |

| O95167 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 3 | 0.008545123 | down |

| Q496C9 | D-aminoacyl-tRNA deacylase | 0.008949922 | up |

| A8K8P8 | Alpha-(1,6)-fucosyltransferase | 0.00914376 | down |

| B4DTK7 | cDNA FLJ61387, highly similar to Homo sapiens conserved nuclear protein NHN1 (NHN1), Mrna | 0.009420668 | up |

| A0A024R1I7 | Tuftelin-interacting protein 11 | 0.009715326 | up |

| Map Title | Adjusted p Value | Regulated | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECM-receptor interaction | 5.55 × 10−5 | up | Laminin subunit beta-3, HCG1811249,isoform CRA_e, Laminin subunit gamma-2, Fibronectin 1, isoform CRA_n, Thrombospondin 1, isoform CRA_a, Agrin, Syndecan-1 |

| Amoebiasis | 0.000108083 | up | Laminin subunit beta-3, HCG1811249, isoform CRA_e, Laminin subunit gamma-2, Fibronectin 1, isoform CRA_n, Ras-related protein Rab-5B, Serpin B6, Leukocyte elastase inhibitor |

| Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | 0.000267166 | up | Cadherin-3, Cadherin-1, Syndecan-1, Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1, Occludin, MHC class I antigen (Fragment), MHC class I antigen (Fragment) |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) | 1.44 × 10−11 | down | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial,Mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial, cDNA FLJ75930, highly similar to Homo sapiens NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 9, 39 kDa (NDUFA9), mRNA, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial, NDUFA7 protein (Fragment), NADH dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 5, 15 kDa (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase), NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 6, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 2, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 4, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 8, mitochondrial, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 12 (Fragment), NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 7, mitochondrial, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 3, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 3, Uncharacterized protein (Fragment), Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta |

| Retrograde endocannabinoid signaling | 1.44 × 10−11 | down | Mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial, cDNA FLJ75930, highly similar to Homo sapiens NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 9, 39 kDa (NDUFA9), mRNA, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial, NDUFA7 protein (Fragment), NADH dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 5, 15 kDa (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase), NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 6, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 2, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 4, mitochondrial, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 8, mitochondrial, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 12 (Fragment), NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 7, mitochondrial, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 3, NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 3, Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 7.51 × 10−10 | down | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial, Mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial,cDNA FLJ75930, highly similar to Homo sapiens NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 9, 39 kDa (NDUFA9), mRNA,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial,NDUFA7 protein (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 5, 15 kDa (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase),NEDD8-activating enzyme E1 regulatory subunit,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 6,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 2,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 4, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 8, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 12 (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 7, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 3,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 3,Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 1.02 × 10−9 | down | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial,Mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial,cDNA FLJ75930, highly similar to Homo sapiens NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 9, 39 kDa (NDUFA9), mRNA,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial,NDUFA7 protein (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 5, 15 kDa (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase),NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 6,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 2,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 4, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 8, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 12 (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 7, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 3,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 3,Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1.02 × 10−9 | down | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial,Mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial,cDNA FLJ75930, highly similar to Homo sapiens NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 9, 39 kDa (NDUFA9), mRNA,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial,NDUFA7 protein (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 5, 15 kDa (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase),NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 6,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 2,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 4, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 8, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 12 (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 7, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 3,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 3,Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) |

| Huntington’s disease | 3.50 × 10−8 | down | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial,Mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial,cDNA FLJ75930, highly similar to Homo sapiens NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 9, 39 kDa (NDUFA9), mRNA,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial,NDUFA7 protein (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 5, 15 kDa (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase),NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 6,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 2,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 4, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 8, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 12 (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 7, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 3,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 3,Uncharacterized protein (Fragment) |

| Metabolic pathways | 5.47 × 10−7 | down | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein subunit, mitochondrial,Mitochondrial NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase 75 kDa subunit,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 1, mitochondrial,cDNA FLJ75930, highly similar to Homo sapiens NADH dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) 1 alpha subcomplex, 9, 39 kDa (NDUFA9), mRNA,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] flavoprotein 2, mitochondrial,Drug-sensitive protein 1,Alpha-(1,6)-fucosyltransferase,Short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase 3,NDUFA7 protein (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase (Ubiquinone) Fe-S protein 5, 15 kDa (NADH-coenzyme Q reductase),NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 6,Ferrochelatase, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 2,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 4, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 8, mitochondrial,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 12 (Fragment),NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur protein 7, mitochondrial,2-oxoisovalerate dehydrogenase subunit alpha,N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 7,Amidophosphoribosyltransferase,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 alpha subcomplex subunit 3,NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 beta subcomplex subunit 3,Uncharacterized protein (Fragment),DNA-directed RNA polymerase I subunit RPA2,Biliverdin reductase A,Dol-P-Man:Man(5)GlcNAc(2)-PP-Dol alpha-1,3-mannosyltransferase,Phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthase (FGAR amidotransferase), isoform CRA_b, Dihydropyrimidinase, UDP-Gal:betaGlcNAc beta 1,4-galactosyltransferase, polypeptide 4 |

| Glycosaminoglycan biosynthesis—keratan sulfate | 0.025255288 | down | Alpha-(1,6)-fucosyltransferase, UDP-Gal:betaGlcNAc beta 1,4-galactosyltransferase, polypeptide 4 |

| Time (Days) | Control | Solvent Control | 50 mg/kg EEP | 100 mg/kg EEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 106.9 ± 21.64 | 108.06 ± 16.09 | 127.03 ± 31.07 | 153 ± 32.99 |

| 3 | 297.37 ± 43.17 | 223.74 ± 40.86 | 299.84 ± 68.85 | 267.42 ± 25.71 |

| 6 | 472.45 ± 64.62 | 368.35 ± 51.45 | 505.06 ± 112.64 | 424.31 ± 58.3 |

| 9 | 708.31 ± 74.26 | 696.13 ± 145.68 | 765.78 ± 169.3 | 530.67 ± 57.45 |

| 12 | 919.71 ± 56.47 | 1118.4 ± 239.05 | 1001.22 ± 202.33 | 771.04 ± 79.93 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Tian, Y.; Yang, A.; Tan, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, W. Antitumor Effect of Poplar Propolis on Human Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma A431 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242316753

Zhang C, Tian Y, Yang A, Tan W, Liu X, Yang W. Antitumor Effect of Poplar Propolis on Human Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma A431 Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(23):16753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242316753

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chuang, Yuanyuan Tian, Ao Yang, Weihua Tan, Xiaoqing Liu, and Wenchao Yang. 2023. "Antitumor Effect of Poplar Propolis on Human Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma A431 Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 23: 16753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242316753

APA StyleZhang, C., Tian, Y., Yang, A., Tan, W., Liu, X., & Yang, W. (2023). Antitumor Effect of Poplar Propolis on Human Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma A431 Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(23), 16753. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms242316753