Genomic Evolution and Transcriptional Changes in the Evolution of Prostate Cancer into Neuroendocrine and Ductal Carcinoma Types

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

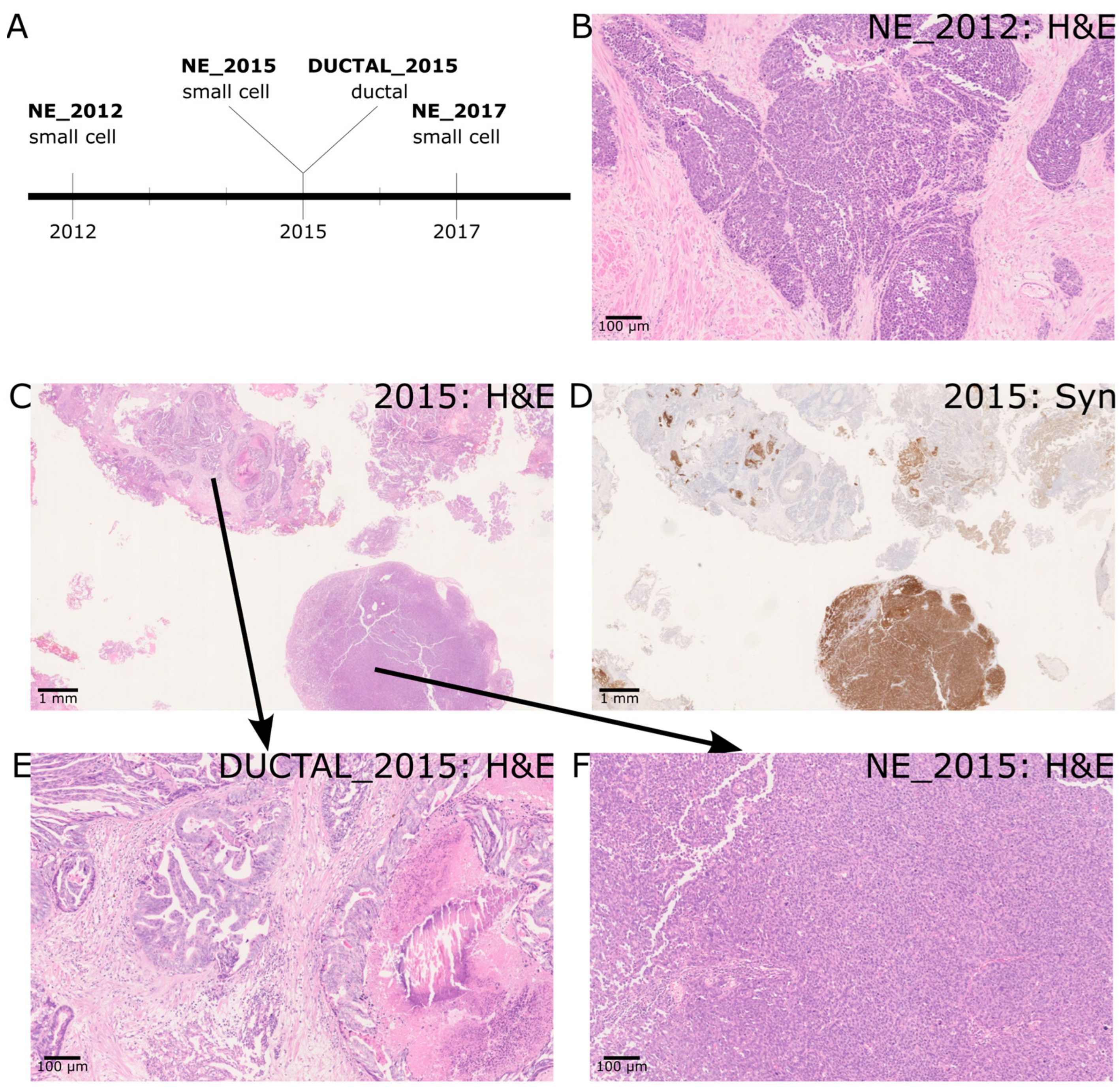

2.1. A Case of de Novo SCNEC with Recurrence and Co-Occurrence of Ductal Adenocarcinoma

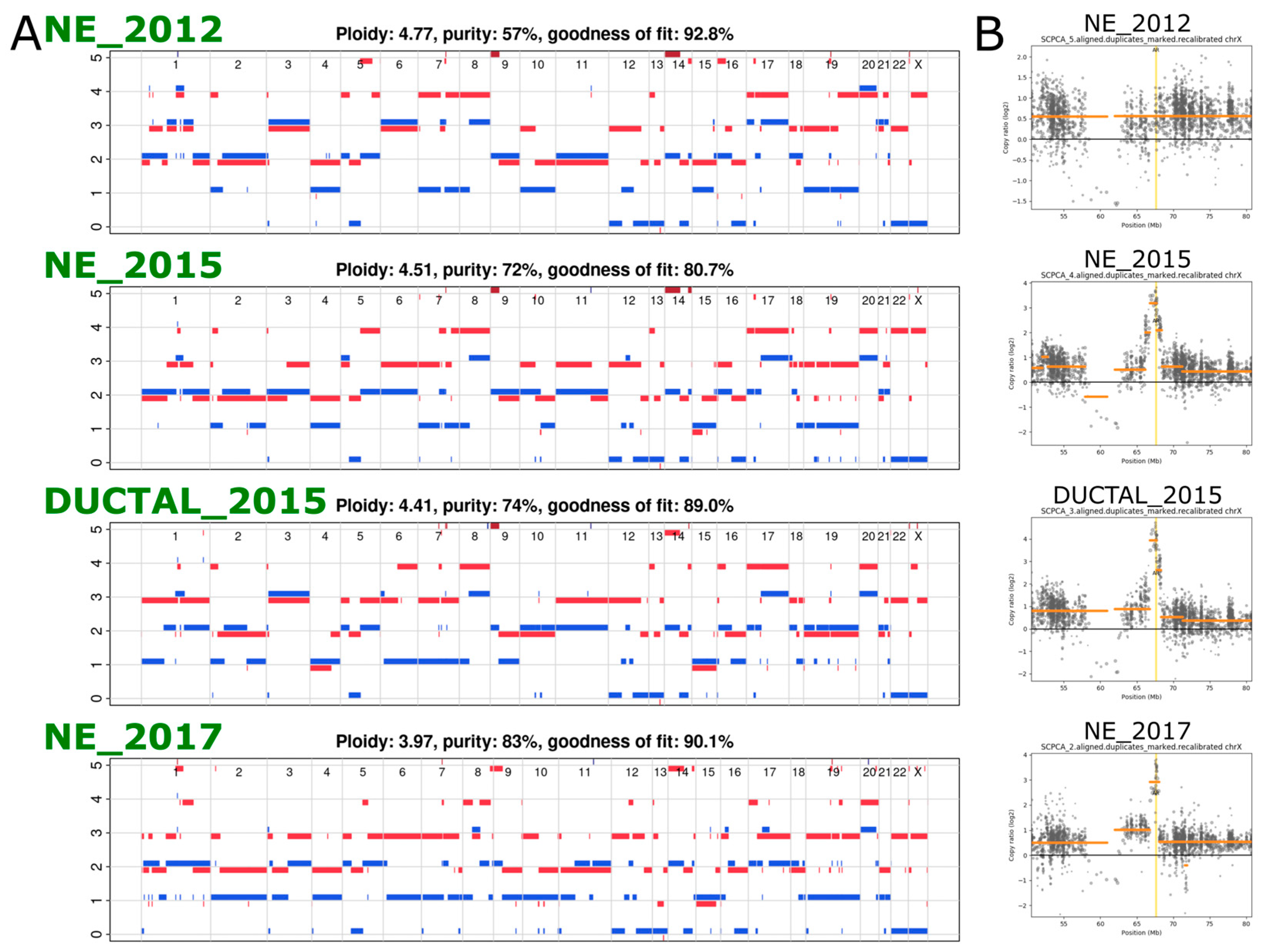

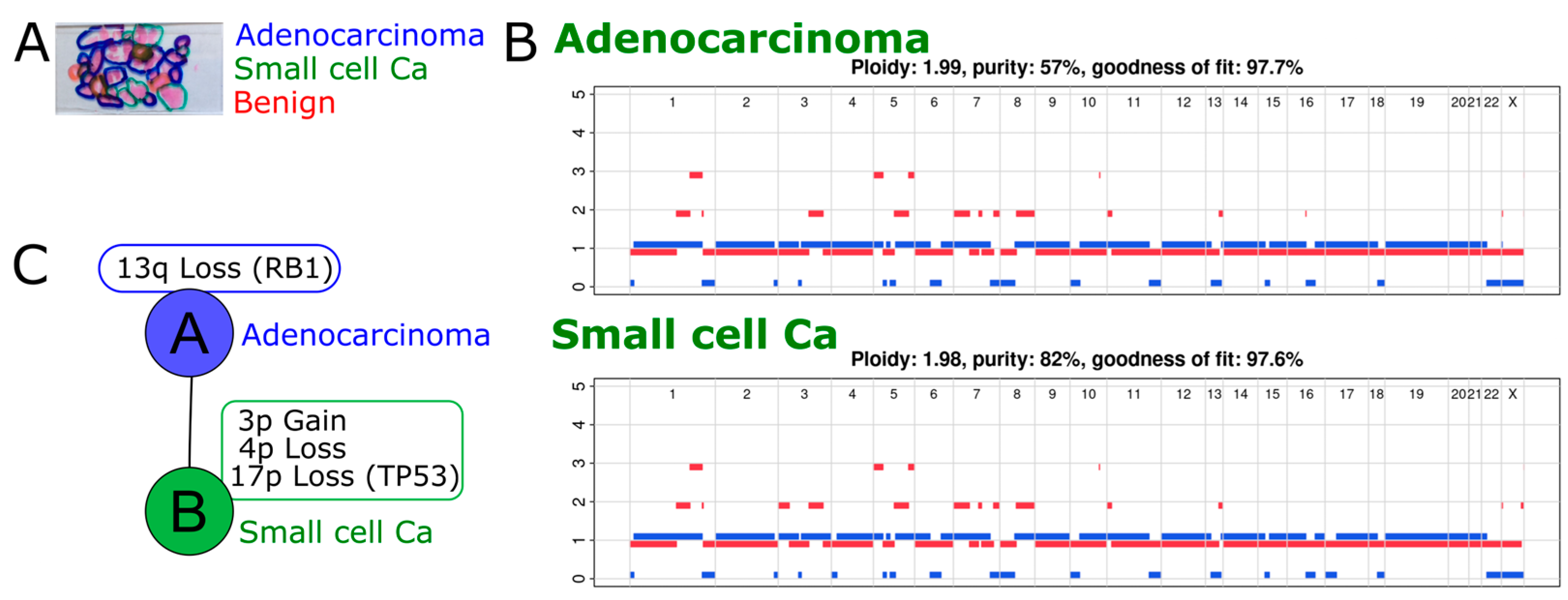

2.2. Exome Sequencing Reveals Copy Number Changes in the Recurrent SCNEC

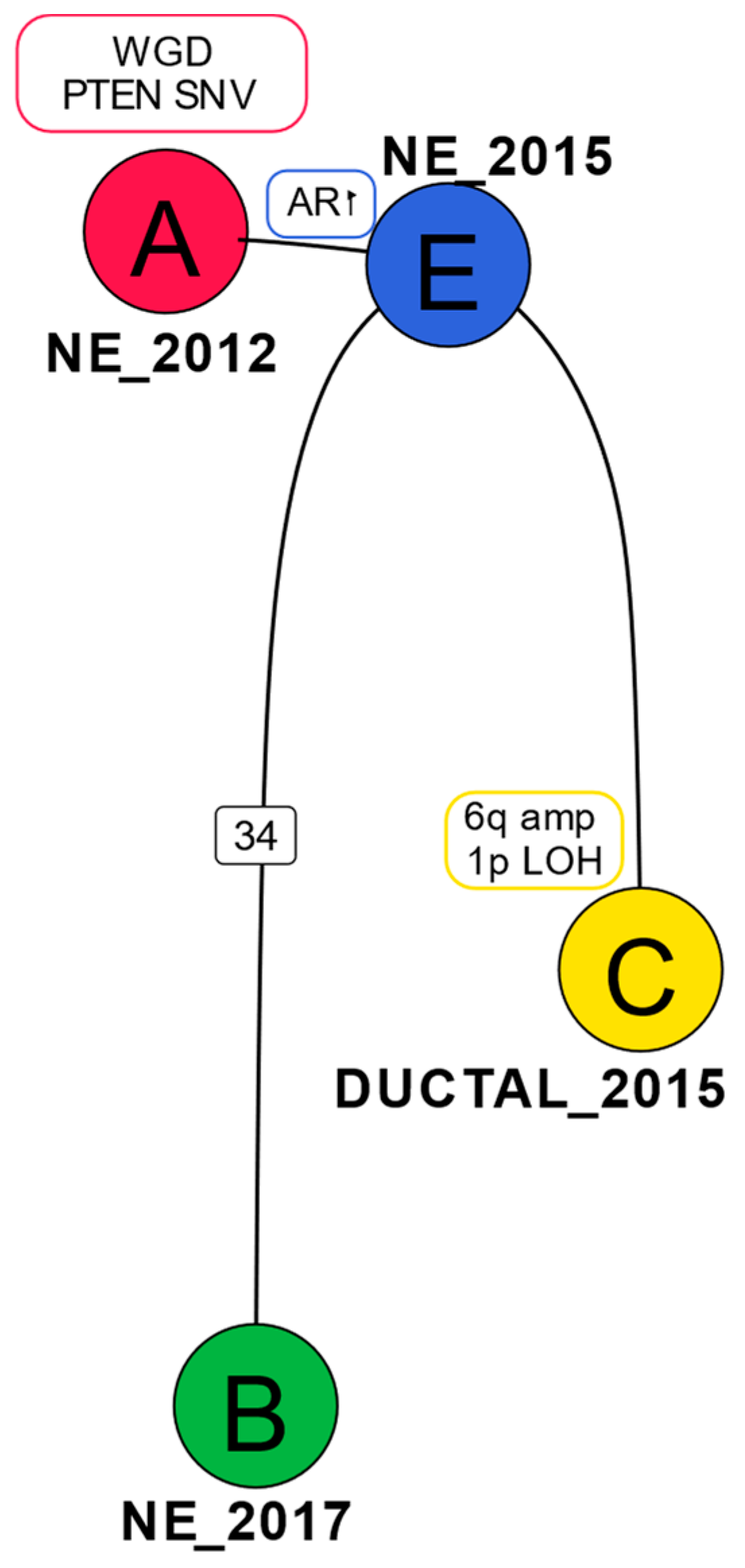

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis Shows Evolution of the Cancer over Time

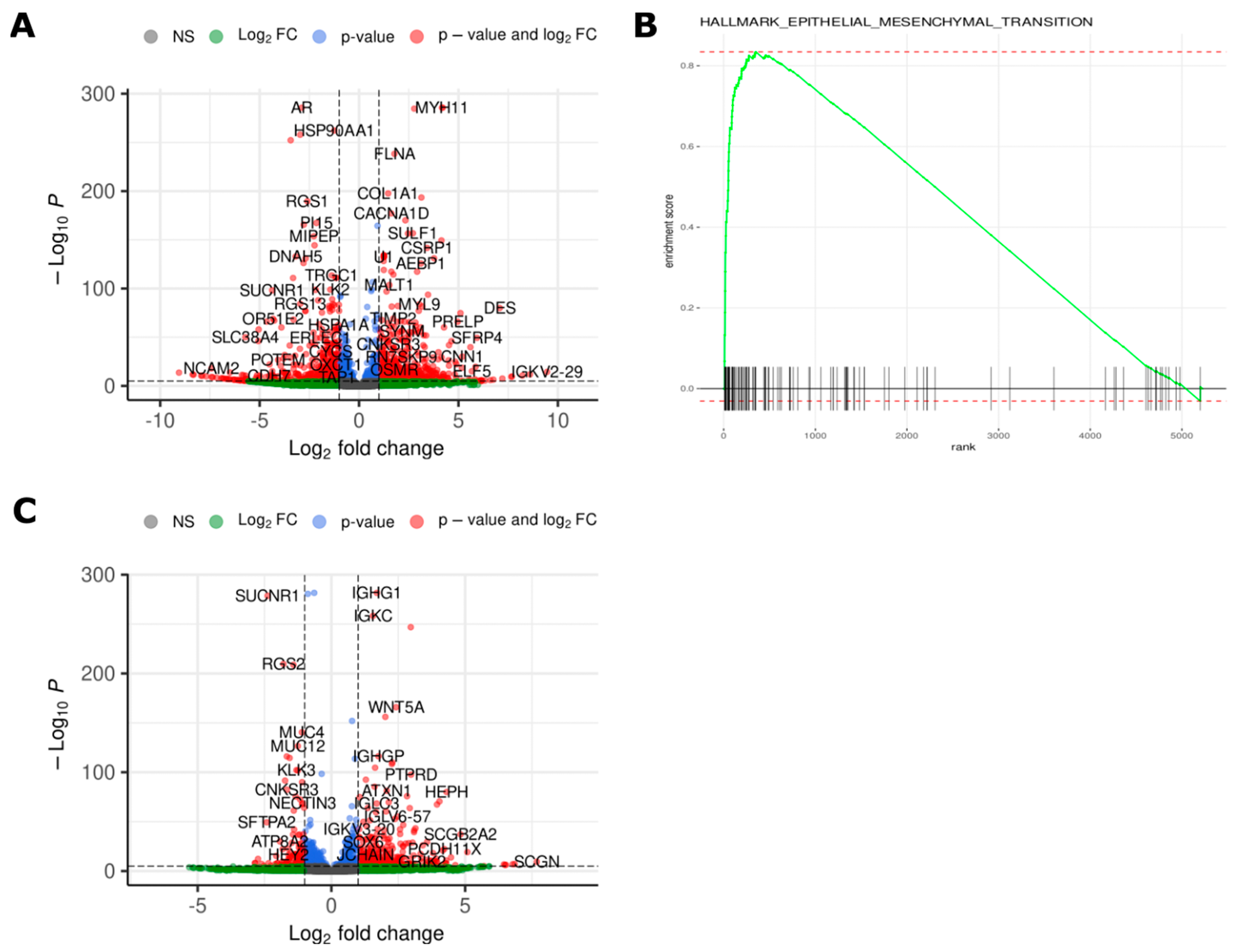

2.4. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Differences in Gene Expression between Different Time Points and Morphologies

2.5. Exome Analysis in a Second Patient Shows Evolution of t-NEPC

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Immunohistochemistry

4.2. Sample Processing

4.3. Exome Sequencing

4.4. Pre-Processing

4.5. SNV Calling

4.6. Copy Number Calling

4.7. Phylogenetic Tree Construction

4.8. RNA Sequencing

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prostate Cancer Incidence Statistics. Cancer Research UK. 2015. Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/prostate-cancer/incidence (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Urinary and Male Genital Tumours. In WHO Classification of Tumours, 5th ed.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulfatah, E.; Fine, S.W.; Lotan, T.L.; Mehra, R. De novo neuroendocrine features in prostate cancer. Hum. Pathol. 2022, 127, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaffuto, E.; Pompe, R.; Zanaty, M.; Bondarenko, H.D.; Leyh-Bannurah, S.-R.; Moschini, M.; Dell’Oglio, P.; Gandaglia, G.; Fossati, N.; Stabile, A.; et al. Contemporary Incidence and Cancer Control Outcomes of Primary Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer: A SEER Database Analysis. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2017, 15, e793–e800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachostergios, P.J.; Puca, L.; Beltran, H. Emerging Variants of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, X.; Xu, R.; Zhang, C.; Meng, H.; Zhao, J.; Shi, C. Advances in neuroendocrine prostate cancer research: From model construction to molecular network analyses. Lab. Investig. 2022, 102, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, A.; Herrmann, A.; Cherryholmes, G.; Kowolik, C.; Buettner, R.; Pal, S.; Yu, H.; Müller-Newen, G.; Jove, R. Loss of androgen receptor expression promotes a stem-like cell phenotype in prostate cancer through STAT3 signaling. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltran, H.; Prandi, D.; Mosquera, J.M.; Benelli, M.; Puca, L.; Cyrta, J.; Marotz, C.; Giannopoulou, E.; Chakravarthi, B.V.S.K.; Varambally, S.; et al. Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, M.; Caradec, J.; Lubik, A.A.; Li, N.; Hollier, B.G.; Takhar, M.; Altimirano-Dimas, M.; Chen, M.; Roshan-Moniri, M.; Butler, M.; et al. Therapy-induced developmental reprogramming of prostate cancer cells and acquired therapy resistance. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 18949–18967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, R.; Wang, Z.; Montironi, R.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, M.; Santoni, M.; Huang, K.; Massari, F.; Lu, X.; Cimadamore, A.; et al. Epigenetic modulations and lineage plasticity in advanced prostate cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinha, N.; Omer, A.; Philippou, Y.; Harriss, E.; Davies, L.; Chow, K.; Chetta, P.M.; Erickson, A.; Rajakumar, T.; Mills, I.G.; et al. Ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate: A systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence, presentation, prognosis, and management. BJUI Compass 2021, 2, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipel, A.H.; Wiklund, F.; Wiklund, N.P.; Egevad, L. Histopathological features of ductal adenocarcinoma of the prostate in 1051 radical prostatectomy specimens. Virchows Arch. 2013, 462, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Lu, Y.; Vogel, M.; Zhang, R.; Wu, J.; Gao, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhu, Q.; Ye, L.; et al. Comparison of Survival Outcomes and Risk Factors between Ductal Carcinoma of the Prostate and Acinar Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate: A Population-based Propensity Score–matching Study. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2022, 46, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, S.; Lim, E.L.; Horswell, S.; Haase, K.; Huebner, A.; Dietzen, M.; Mourikis, T.P.; Watkins, T.B.; Rowan, A.; Dewhurst, S.M.; et al. Interplay between whole-genome doubling and the accumulation of deleterious alterations in cancer evolution. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T.R.W.; Chappell, L.; Sanghvi, R.; Deighton, L.; Ansari-Pour, N.; Dentro, S.C.; Young, M.D.; Coorens, T.H.H.; Jung, H.; Butler, T.; et al. Clonal diversification and histogenesis of malignant germ cell tumours. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, P.; Baber, J.; Lolkema, M.P.; Steeghs, N.; de Bruijn, E.; Shale, C.; Duyvesteyn, K.; Haidari, S.; van Hoeck, A.; Onstenk, W.; et al. Pan-cancer whole-genome analyses of metastatic solid tumours. Nature 2019, 575, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Verrill, C.; Cerundolo, L.; Alham, N.K.; Kaya, Z.; O’Hanlon, M.; Hayes, A.; Lambert, A.; James, M.; Tullis, I.D.; et al. Intra-Prostatic Tumour Evolution, Steps in Metastatic Spread and Histogenomic Associations Revealed by Integration of Multi-region Whole Genome Sequencing with Histopathological Features. bioRxiv 2023. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.02.27.530113v2 (accessed on 20 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Hankey, W.; Fang, X.; Yuan, F. Second generation androgen receptor antagonists and challenges in prostate cancer treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Chiang, Z.D.; Morriss, J.W.; LaFave, L.M.; Murray, E.M.; Del Priore, I.; Meli, K.; Lareau, C.A.; Nadaf, N.M.; Li, J.; et al. Spatial genomics enables multi-modal study of clonal heterogeneity in tissues. Nature 2022, 601, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakht, M.K.; Yamada, Y.; Ku, S.-Y.; Venkadakrishnan, V.B.; Korsen, J.A.; Kalidindi, T.M.; Mizuno, K.; Ahn, S.H.; Seo, J.-H.; Garcia, M.M.; et al. Landscape of prostate-specific membrane antigen heterogeneity and regulation in AR-positive and AR-negative metastatic prostate cancer. Nat. Cancer 2023, 4, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.R.; Alham, N.K.; Upton, E.; McIntyre, S.; Bryant, R.J.; Cerundolo, L.; Bowes, E.; Jones, S.; Browne, M.; Mills, I.; et al. Detailed Molecular and Immune Marker Profiling of Archival Prostate Cancer Samples Reveals an Inverse Association between TMPRSS2:ERG Fusion Status and Immune Cell Infiltration. J. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 22, 652–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBMap. SourceForge. 2022. Available online: http://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/ (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Li, H. Aligning Sequence Reads, Clone Sequences and Assembly Contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.3997. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997 (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Van der Auwera, G.A.; Carneiro, M.O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J.; et al. From FastQ Data to High-Confidence Variant Calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit Best Practices Pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2013, 43, 11.10.1–11.10.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, E.M.; Haase, K.; Van Loo, P.; Markowetz, F. Allele-specific multi-sample copy number segmentation in ASCAT. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 1909–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkevich, G.; Sukhov, V.; Budin, N.; Shpak, B.; Artyomov, M.N.; Sergushichev, A. Fast Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. bioRxiv 2021. Available online: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/060012v3 (accessed on 9 May 2023). [CrossRef]

| Histology | Clinical Details Provided with Histology Section | IHC Profile/Morphology | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | |||

| Section 1 (2012) | Prostate chippings. Recently started hormone therapy for node-positive cancer, thought to be prostate. | PSA+ TTF-1+ Synaptophysin– CD56– ChromograninA– Strong morphological impression of SCNEC | Small cell carcinoma of prostatic origin. |

| Section 2 (2015) | Prostate chippings. Prostate cancer on hormones and chemotherapy. Post radiotherapy. | In NE areas: PSA not performed TTF-1+ Synatophysin+ CD56+ ChromograninA+ | Prostatic adenocarcinoma of acinar and ductal type with areas of small cell (neuroendocrine differentiation) |

| Section 3 (2017) | History of prostate cancer with neuroendocrine component—due to start chemotherapy. Visible haematuria, new bladder mass on flexible cystoscopy. TURBT—mass connected to the prostate—likely extension of prostate cancer rather than new bladder tumor. On Zoladex. | PSA + (patchy) TTF-1- Synaptophysin—(occasional cells + only) CD56– ChromograninA– Strong morphological impression of SCNEC. | Bladder and prostate chippings—high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma with small cell carcinoma/small cell neuroendocrine differentiation |

| Case 2 | |||

| 1999 | Known advanced prostate cancer (diagnosed 1998 on prostate biopsy as Gleason Score 8 (4 + 4) adenocarcinoma. | Strong morphological impression of SCNEC | Prostate adenocarcinoma with many small cell areas |

| Protein | Antibody Type | Supplier and Usage Details |

|---|---|---|

| Chromogranin A | mouse monoclonal antibody clone DAK-A3 | DAKO M0869 (working dilution 1/100) |

| Synaptophysin | mouse monoclonal antibody | Novocastra NCL-L-SYNAP-299 (working dilution 1/100) |

| CD56 | mouse monoclonal antibody | Novocastra NCL-L-CD56-504 (working dilution 1/100) |

| Androgen Receptor | mouse monoclonal antibody | Leica AR-318-L-CE (working dilution 1/25) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rao, S.R.; Protheroe, A.; Cerundolo, L.; Maldonado-Perez, D.; Browning, L.; Lamb, A.D.; Bryant, R.J.; Mills, I.G.; Woodcock, D.J.; Hamdy, F.C.; et al. Genomic Evolution and Transcriptional Changes in the Evolution of Prostate Cancer into Neuroendocrine and Ductal Carcinoma Types. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612722

Rao SR, Protheroe A, Cerundolo L, Maldonado-Perez D, Browning L, Lamb AD, Bryant RJ, Mills IG, Woodcock DJ, Hamdy FC, et al. Genomic Evolution and Transcriptional Changes in the Evolution of Prostate Cancer into Neuroendocrine and Ductal Carcinoma Types. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(16):12722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612722

Chicago/Turabian StyleRao, Srinivasa R., Andrew Protheroe, Lucia Cerundolo, David Maldonado-Perez, Lisa Browning, Alastair D. Lamb, Richard J. Bryant, Ian G. Mills, Dan J. Woodcock, Freddie C. Hamdy, and et al. 2023. "Genomic Evolution and Transcriptional Changes in the Evolution of Prostate Cancer into Neuroendocrine and Ductal Carcinoma Types" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 16: 12722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612722

APA StyleRao, S. R., Protheroe, A., Cerundolo, L., Maldonado-Perez, D., Browning, L., Lamb, A. D., Bryant, R. J., Mills, I. G., Woodcock, D. J., Hamdy, F. C., Tomlinson, I. P. M., & Verrill, C. (2023). Genomic Evolution and Transcriptional Changes in the Evolution of Prostate Cancer into Neuroendocrine and Ductal Carcinoma Types. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(16), 12722. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241612722