Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis in a Patient with Sjögren’s Syndrome

Abstract

1. Introduction

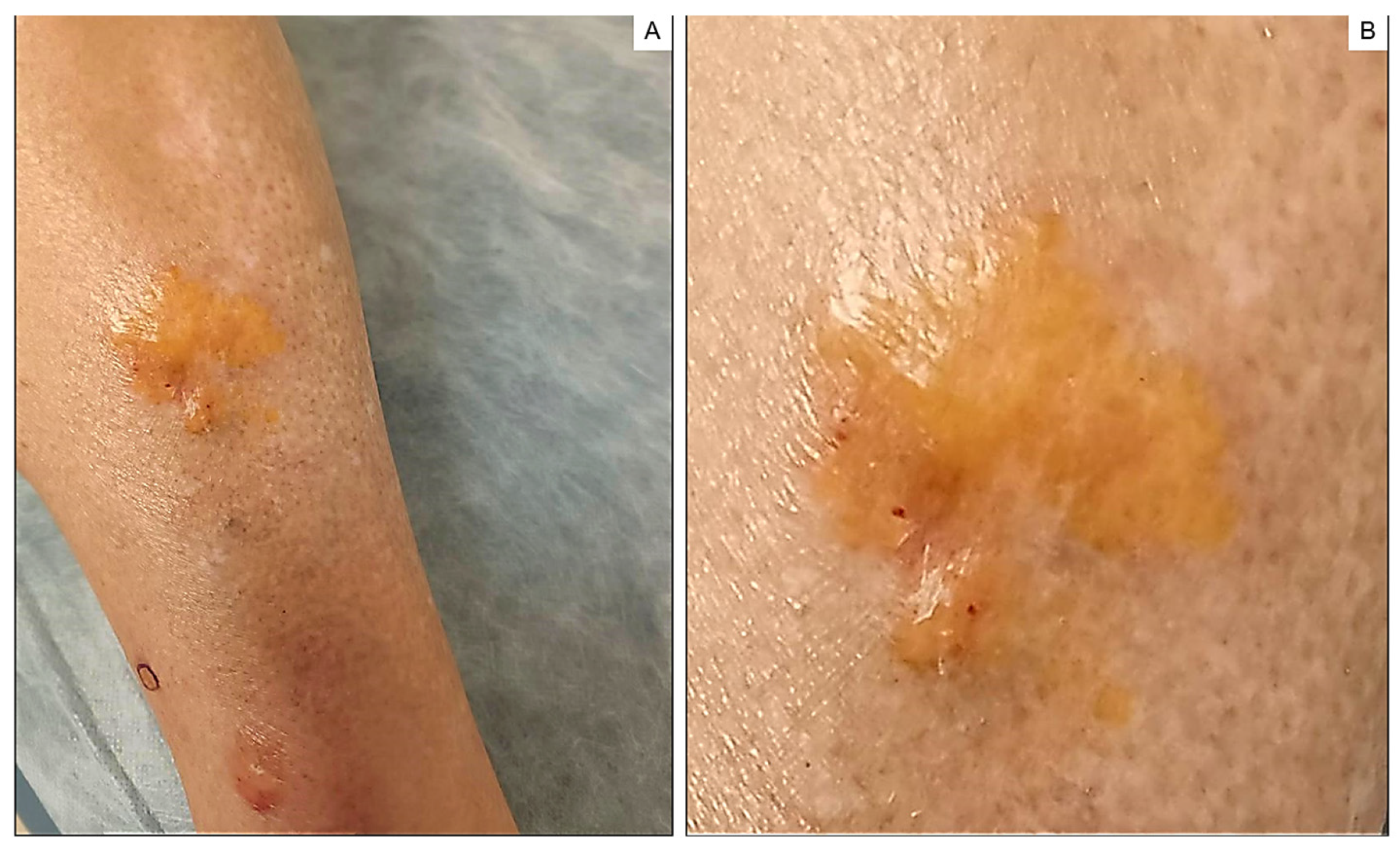

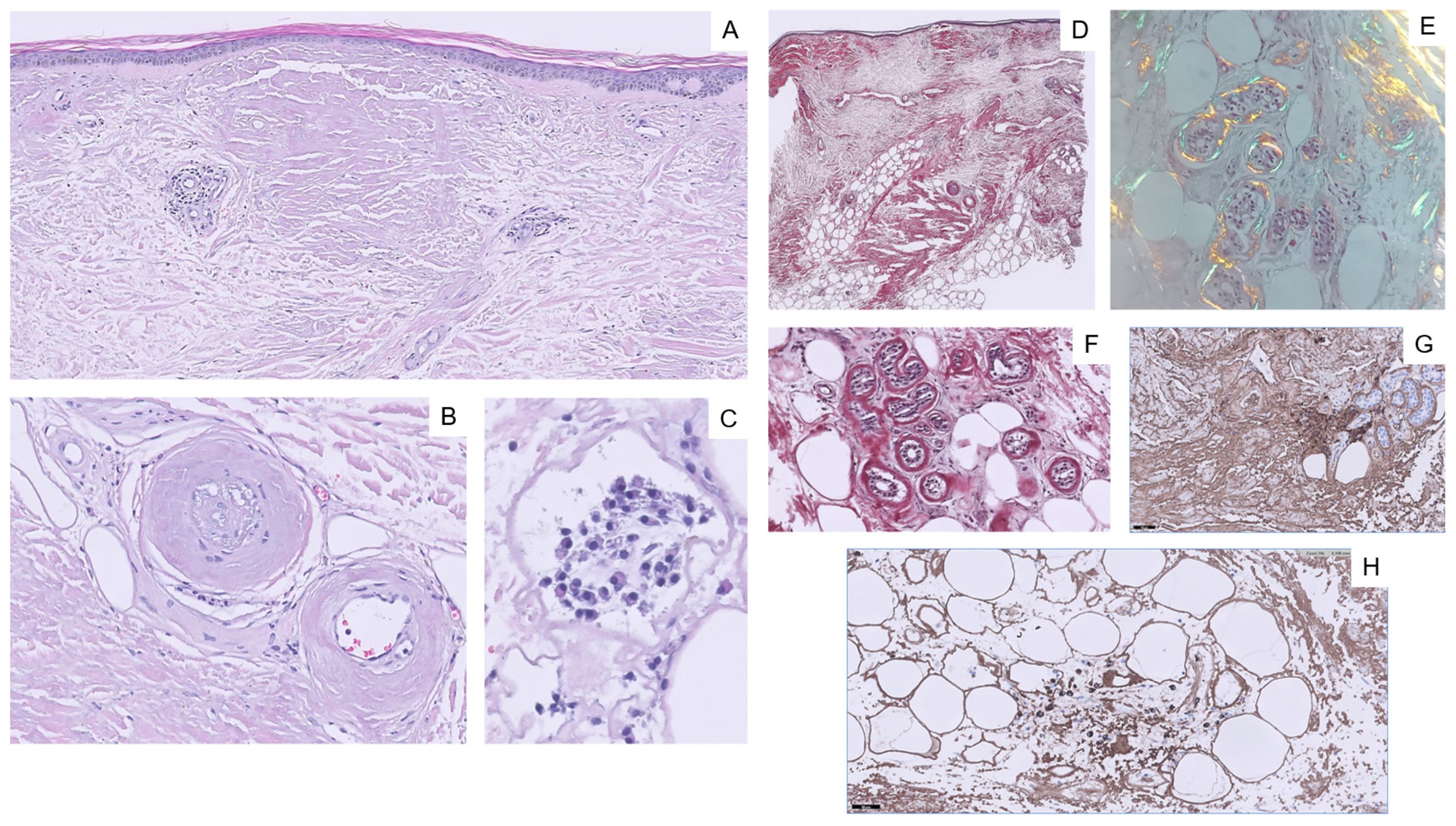

2. Case Report

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davies, K.; Collins, A.; Charlton, F.G.; Ng, W.F. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis and primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 49, 159–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Nevado, A.; Muñoz-Castillo, R.; López-Jiménez, P.; Bosch-García, R.; Herrera-Ceballos, E. Amiloidosis cutánea nodular primaria en paciente con síndrome de Sjögren. Piel 2015, 31, 333–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhao, Z. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis presenting as lymphatic malformation: A case report. Open. Life Sci. 2021, 16, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, P. Primary Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis Presenting as Milia: An Unusual Clinical Manifestation. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 1639–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaChance, A.; Phelps, A.; Finch, J.; Lu, J.; Elaba, Z.; Rezuke, W.; Murphy, M.J. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis: A bullous variant. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 39, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, M.E.; Collins, M.K.; Raptis, A.; Jedrych, J.; Patton, T. Multifocal primary cutaneous nodular amyloidosis. Dermatol. Online J. 2017, 23, 13030/qt9511r6bg. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinato, F.; Rosina, P.; Sina, S.; Girolomoni, G. Primary nodular localized cutaneous amyloidosis of the scalp associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch. Rheumatol. 2021, 37, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraguchi, H.; Ohashi, K.; Yamada, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Maeda, S.; Komatsuzaki, A. Primary localized nodular tongue amyloidosis associated with Sjögren’s syndrome. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 1997, 59, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.W.; Hung, C.T.; Gao, H.W.; Chiang, C.P.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, W.M. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis on areola. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2022, 88, 653–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.L.; Fernandes, E.L.; Lapins, J.; Silva, L.C.; Benini, T.; Lazoni, M.A.; Steiner, D. Primary Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis on a Toe: Clinical Presentation, Histopathology, and Dermoscopy Findings. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2019, 9, 235–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naj, K.; Nellhaus, E.; Griswold, D.; Jamil, M.O. First Case of Nodular Localized Primary Cutaneous Amyloidosis Treated With Bortezomib and Dexamethasone. J. Investig. Med. High. Impact Case Rep. 2021, 9, 23247096211058488. [Google Scholar]

- Schwendiman, M.N.; Beachkofsky, T.M.; Wisco, O.J.; Owens, N.M.; Hodson, D.S. Primary cutaneous nodular amyloidosis: Case report and review of the literature. Cutis 2009, 84, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Atzori, L.; Ferreli, C.; Matucci-Cerinic, C.; Pilloni, L.; Rongioletti, F. Primary Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis and Limited Cutaneous Systemic Sclerosis: Additional Cases with Dermatoscopic and Histopathological Correlation of Amyloid Deposition. Dermatopathology 2021, 8, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonagara, B.; Mehta, H.; Gajjar, P. Dermoscopy of localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis resembling granulomatous disorders. Indian. J. Dermatopathol. Diagn. Dermatol. 2019, 6, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.J.; Li, Y.; Lim, K.H.; Oh, C.C. Dermatoscope of primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis on hallux nail bed. JAAD Case Rep. 2022, 27, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planas-Ciudad, S.; Roé Crespo, E.; Mir-Bonafé, J.F.; Muñoz-Garza, F.Z.; Puig Sanz, L. Dystrophic Calcification in a Patient with Primary Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis: An Uncommon Ultrasound Finding. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2018, 98, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woollons, A.; Black, M.M. Nodular localized primary cutaneous amyloidosis: A long-term follow-up study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001, 145, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidner, T.; Illing, T.; Elsner, P. Primary Localized Cutaneous Amyloidosis: A Systematic Treatment Review. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2017, 18, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesiak, A.; Rakowski, A.; Brzezinska, A.; Rogowski-Tylman, M.; Kolano, P.; Sysa-Jedrzejowska, A.; Narbutt, J. Effective treatment of nodular amyloidosis with carbon dioxide laser. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2012, 16, 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzavi, I.; Lui, H. Excess tissue friability during CO2 laser vaporization of nodular amyloidosis. Dermatol. Surg. 1999, 25, 726–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truhan, A.P.; Garden, J.M.; Roenigk, H.H., Jr. Nodular primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis: Immunohistochemical evaluation and treatment with the carbon dioxide laser. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1986, 14, 1058–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakani, R.S.; Goldstein, A.E.; Meisher, I.; Hoffman, C. Nodular amyloidosis: Case report and literature review. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2001, 5, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, S.A.; Beachkofsky, T.; Schreml, S.; Gaspari, A.; Hivnor, C.M. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis of the feet: A case report and review of the literature. Cutis 2014, 93, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yong, A.S.; Murphy, J.G.; Shah, N. Nodular localized cutaneous amyloidosis in an immunosuppressed patient. Int. J. Dermatol. 2015, 54, 708–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, P.L.; Walker, W.A.; Glancy, R.J.; Cooney, J.P.; Gebauer, K. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis successfully treated with cyclophosphamide. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2013, 54, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.; Choi, J. Nodular cutaneous amyloidosis effectively treated with intralesional methotrexate. JAAD Case Rep. 2016, 2, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Emmi, G.; Greco, M.; Borro, M.; Sardanelli, F.; Murdaca, G.; Indiveri, F.; Puppo, F. Sjögren’s syndrome: A systemic autoimmune disease. Clin. Exp. Med. 2022, 22, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Generali, E.; Costanzo, A.; Mainetti, C.; Selmi, C. Cutaneous and Mucosal Manifestations of Sjögren’s Syndrome. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 53, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, J.M.; Schonland, S.O.; Palladini, G.; Merlini, G.; Hegenbart, U.; Ciocca, O.; Perfetti, V.; Leijsma, M.K.; Bootsma, H.; Hazenberg, B.P. Sjögren’s syndrome and localized nodular cutaneous amyloidosis: Coincidence or a distinct clinical entity? Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58, 1992–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagari, Y.; Mihara, M.; Hagari, S. Nodular localized cutaneous amyloidosis: Detection of monoclonality of infiltrating plasma cells by polymerase chain reaction. Br. J. Dermatol. 1996, 135, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünewald, K.; Sepp, N.; Weyrer, K.; Lhotta, K.; Feichtinger, H.; Konwalinka, G.; SM, B.; Hintner, H. Gene rearrangement studies in the diagnosis of primary systemic and nodular primary localized cutaneous amyloidosis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1991, 97, 693–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Oyama, N.; Hasegawa, M. Localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis in a patient with primary Sjögren syndrome: A revisit of autoimmunity-modifying clinicopathology through an updated literature review. J. Cutan. Immunol. Allergy 2020, 3, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, A.O.; Calamia, K.T.; Walsh, J.S. Nodular amyloidosis: Review and long-term follow-up of 16 cases. Arch Derm. 2003, 139, 1157–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, E.M.; Kendrick, C.G. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis and CREST syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. Cutis 2008, 82, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shiman, M.; Ricotti, C.; Miteva, M.; Kerdel, F.; Romanelli, P. Primary localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis associated with CREST (calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal motility disorders, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia) syndrome. Int. J. Dermatol. 2010, 49, 229–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettsche, L.S.; Moye, M.S.; Tschetter, A.J.; Stone, M.S.; Wanat, K.A. Three cases of localized cutaneous nodular amyloidosis in patients with limited systemic sclerosis and a brief literature review. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2017, 3, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llamas-Molina, J.M.; Velasco-Amador, J.P.; De La Torre-Gomar, F.J.; Carrero-Castaño, A.; Ruiz-Villaverde, R. Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis in a Patient with Sjögren’s Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9409. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119409

Llamas-Molina JM, Velasco-Amador JP, De La Torre-Gomar FJ, Carrero-Castaño A, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis in a Patient with Sjögren’s Syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(11):9409. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119409

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlamas-Molina, José María, Juan Pablo Velasco-Amador, Francisco Javier De La Torre-Gomar, Alejandro Carrero-Castaño, and Ricardo Ruiz-Villaverde. 2023. "Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis in a Patient with Sjögren’s Syndrome" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 11: 9409. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119409

APA StyleLlamas-Molina, J. M., Velasco-Amador, J. P., De La Torre-Gomar, F. J., Carrero-Castaño, A., & Ruiz-Villaverde, R. (2023). Localized Cutaneous Nodular Amyloidosis in a Patient with Sjögren’s Syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(11), 9409. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119409