The Citrus Laccase Gene CsLAC18 Contributes to Cold Tolerance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Changes in Laccase Activity and Lignin Content in Response to Cold Stress in C. sinensis

2.2. Expression Analysis of CsLACs in Response to Cold Treatment

2.3. Cloning, Sequence Analysis, and Subcellular Localization of CsLAC18

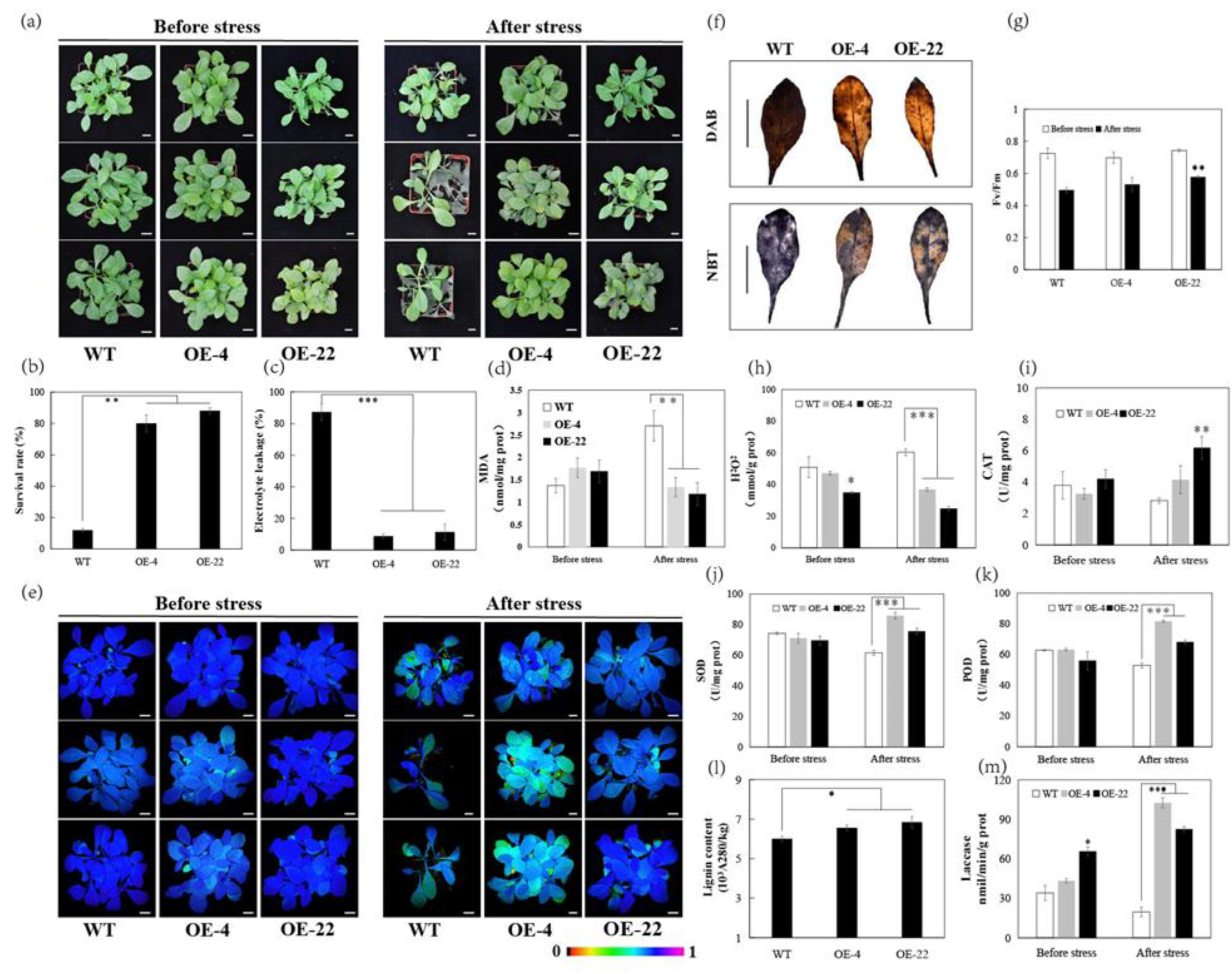

2.4. Overexpression of CsLAC18 Confers Enhanced Cold Tolerance

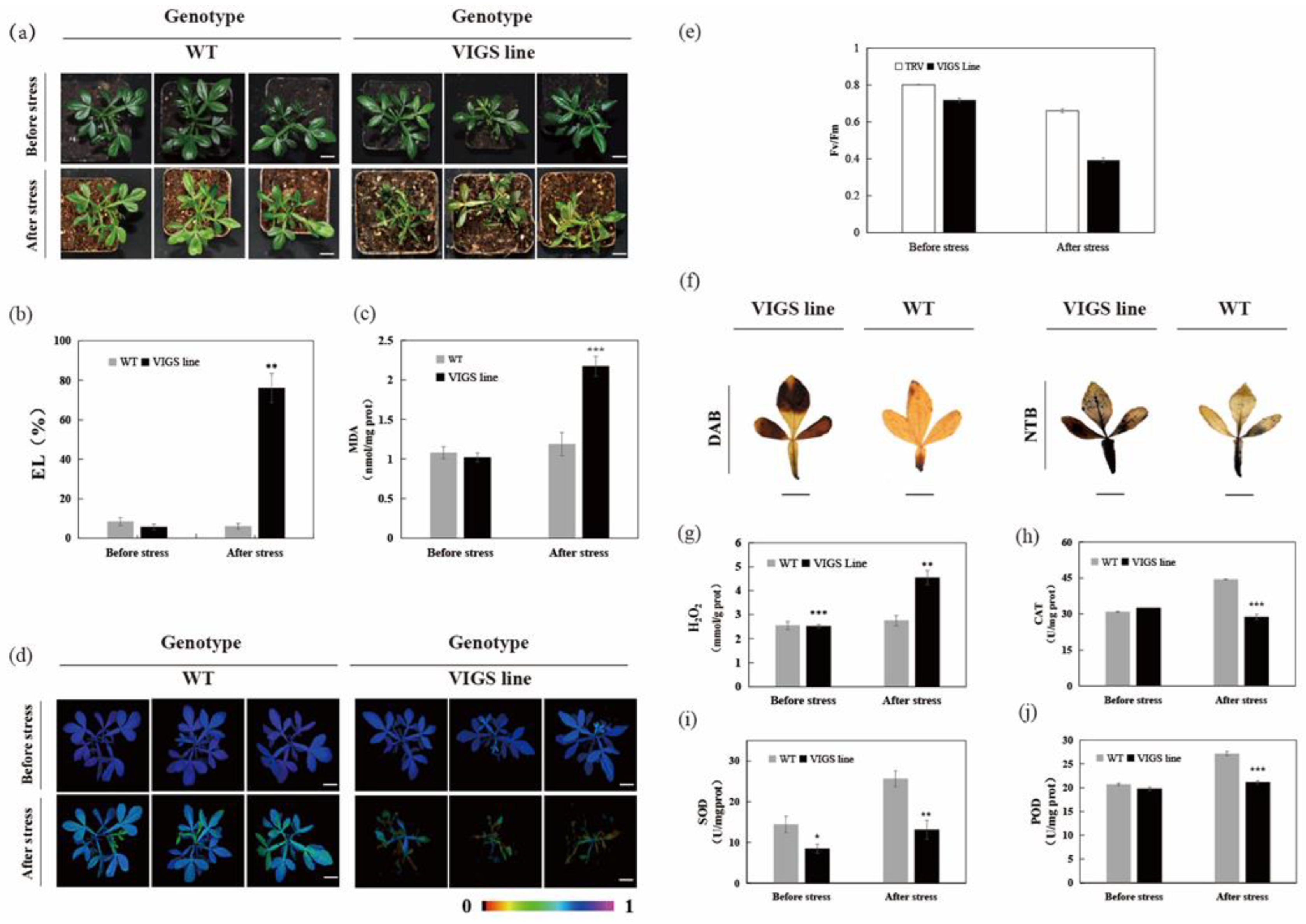

2.5. Silencing of CsLAC18 in Poncirus Trifoliata increases Cold Sensitivity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Cold Treatment

4.2. Determination of Laccase Activity and Lignin Content

4.3. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

4.4. Cloning and Sequence Analysis of CsLAC18

4.5. Subcellular Localization Analysis of CsLAC18

4.6. Vector Construction and Plant Transformation

4.7. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing

4.8. Cold Tolerance Assays, Physiological Measurements and Histochemical Staining

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Primo-Capella, A.; Martínez-Cuenca, M.-R.; Forner-Giner, M.Á. Cold stress in Citrus: A molecular, physiological and biochemical perspective. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Liang, M.; Wang, N.; Xu, Q.; Deng, X.X.; Chai, L.J. Reproduction in woody perennial Citrus: An update on nucellar embryony and self-incompatibility. Plant Reprod. 2018, 31, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janusz, G.; Pawlik, A.; Swiderska-Burek, U.; Polak, J.; Sulej, J.; Jarosz-Wilkolazka, A.; Paszczynski, A. Laccase properties, physiological functions, and evolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H. LXIII.-Chemistry of lacquer (Urushi). Part I. Communication from the Chemical Society of Tokio. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1883, 43, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, F.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Xu, L.Q.; Guo, D.Y.; Luo, Z.R.; Zhang, Q.L. DkmiR397 regulates proanthocyanidin biosynthesis via negative modulating DkLAC2 in Chinese PCNA persimmon. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, Q.F.; Zhang, J.P.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, Y.F.; Feng, Y.Z.; Chen, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.C. Laccase-13 regulates seed setting rate by affecting hydrogen peroxide dynamics and mitochondrial integrity in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Feng, J.J.; Jia, W.T.; Chang, S.; Li, S.Z.; Li, Y.X. Lignin engineering through laccase modification: A promising field for energy plant improvement. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2015, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.C.; Liu, Y.Q.; Dong, X.; Liu, J.J.; Zhao, D.G. Identification of a novel laccase gene EuLAC1 and its potential resistance against Botrytis cinerea. Transgenic Res. 2022, 31, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Zhuang, Y.; Huang, X.Z.; Zhao, D.G.; Zhao, Y.C. Overexpression of cotton laccase gene LAC1 enhances resistance to Botrytis cinereal in tomato plants. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2020, 24, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.Z.; Wang, X.F.; Chen, B.; Zhao, J.; Cui, J.; Li, Z.K.; Yang, J.; Wu, L.Q.; Wu, J.H.; et al. The cotton laccase gene GhLAC15 enhances Verticillium wilt resistance via an increase in defence-induced lignification and lignin components in the cell walls of plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019, 20, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Min, L.; Yang, X.Y.; Jin, S.X.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.Y.; Ma, Y.Z.; Qi, X.W.; Li, D.Q.; Liu, H.B.; et al. Laccase GhLac1 modulates broad-spectrum biotic stress tolerance via manipulating phenylpropanoid pathway and jasmonic acid synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 1808–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.H.; Zhang, L.Y.; Lin, X.J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, W.L.; Zhao, D.; Ferrarezi, R.S.; Fan, G.C.; Chen, L.S. CsiLAC4 modulates boron flow in Arabidopsis and Citrus via high-boron-dependent lignification of cell walls. New Phytol. 2022, 233, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Luo, L.; Wang, X.X.; Shen, Z.G.; Zheng, L.Q. Comprehensive analysis of rice laccase gene (OsLAC) family and ectopic expression of OsLAC10 enhances tolerance to copper stress in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.Y.; Lee, C.; Hwang, S.G.; Park, Y.C.; Lim, H.L.; Jang, C.S. Overexpression of the OsChI1 gene, encoding a putative laccase precursor, increases tolerance to drought and salinity stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. Gene 2014, 552, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Xu, Z.S.; Wang, F.; Xiong, A.S. Isolation, purification and characterization of two laccases from carrot (Daucus carota L.) and their response to abiotic and metal ions stresses. Prot. J. 2015, 34, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.X.; Zhang, L.Q.; Tan, M.Y.; Wang, X.H.; Wang, G.L.; Qi, M.R.; Liu, B.X.; Gao, J.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.Q. Genome-wide identification and characterization of laccase family members in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). Peerj 2022, 10, e12922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Zhou, Y.P.; Wang, B.; Ding, L.; Wang, Y.; Luo, L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Kong, W.W. Genome-wide identification and characterization of laccase gene family in Citrus Sinensis. Gene 2019, 689, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.Y.; Yang, T.Y.; Zhang, Y.W.; Miao, X.C.; Jin, C.; Xu, X.Y. Genome-wide analyses and expression patterns under abiotic stress of LAC gene family in pear (Pyrus bretschneideri). Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 15, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarino, I. Structural features and regulation of lignin deposited upon biotic and abiotic stresses. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019, 56, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.D.; Prasad, T.K.; Stewart, C.R. Changes in isozyme profiles of catalase, peroxidase, and glutathione reductase during acclimation to chilling in mesocotyls of maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1995, 109, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.L.; Li, Q.Y.; Liu, G.L.; Xu, N.; Yang, Y.J.; Zeng, W.L.; Chen, A.G.; Wang, S.S. Integrated analysis of transcriptomic and metabolomic data reveals critical metabolic pathways involved in polyphenol biosynthesis in Nicotiana tabacum under chilling stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2019, 46, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.J.; Wu, W.; Cao, Z.H.; Wen, J.; Shu, Q.L.; Fu, S.L. Morphological, physiological and biochemical responses of Camellia oleifera to low-temperature stress. Pak. J. Bot. 2016, 48, 899–905. [Google Scholar]

- Khaledian, Y.; Maali-Amiri, R.; Talei, A. Phenylpropanoid and antioxidant changes in chickpea plants during cold stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 62, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.B.; Bottcher, A.; Vicentini, R.; Sampaio Mayer, J.L.; Kiyota, E.; Landell, M.A.G.; Creste, S.; Mazzafera, P. Lignin biosynthesis in sugarcane is affected by low temperature. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 120, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagoskina, N.V.; Olenichenko, N.A.; Klimov, S.V.; Astakhova, N.V.; Zhivukhina, E.A.; Trunova, T.I. The effects of cold acclimation of winter wheat plants on changes in CO2 exchange and phenolic compound formation. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 52, 320–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J.F.; Evers, D.; Thiellement, H.; Jouve, L. Compared responses of poplar cuttings and in vitro raised shoots to short-term chilling treatments. Plant Cell Rep. 2000, 19, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabane, M.; Afif, D.; Hawkins, S. Lignins and Abiotic Stresses. In Lignins-Biosynthesis, Biodegradation and Bioengineering: Advances in Botanical Research; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 219–262. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, X.K.; Wang, T.Y.; Lin, N.; Di, F.F.; Li, Y.Y.; Jian, H.J.; Wang, H.; Lu, K.; Li, J.N.; Xu, X.F.; et al. Genome-wide identification of the LAC gene family and its expression analysis under stress in Brassica napus. Molecules 2019, 24, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Z.; Wu, Z.Y.; Wang, H.L.; Fu, C.X.; Zhao, H.B.; He, F. Genome-wide identification of switchgrass laccases involved in lignin biosynthesis and heavy-metal responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.C.; Xing, Y.X.; Liu, F.J.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X.L. The laccase gene family mediate multi-perspective trade-offs during tea plant (Camellia sinensis) development and defense processes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.X.; Zhou, Y.L.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, N.; Hu, S.J.; Li, L.; Li, T. Identification of wheat LACCASEs in response to Fusarium graminearum as potential deoxynivalenol trappers. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 832800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qui, K.L.; Zhou, H.; Pan, H.F.; Sheng, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, Q.M.; Chen, H.L.; Cai, Y.P.; Zhang, J.Y.; He, J.L. Genome-wide identification and functional analysis of the peach (P. persica) laccase gene family reveal members potentially involved in endocarp lignification. Trees 2022, 36, 1477–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthet, S.; Demont-Caulet, N.; Pollet, B.; Bidzinski, P.; Cezard, L.; Le Bris, P.; Borrega, N.; Herve, J.; Blondet, E.; Balzergue, S.; et al. Disruption of LACCASE4 and 17 results in tissue-specific alterations to lignification of Arabidopsis thaliana stems. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bouchabke-Coussa, O.; Lebris, P.; Antelme, S.; Soulhat, C.; Gineau, E.; Dalmais, M.; Bendahmane, A.; Morin, H.; Mouille, G.; et al. LACCASE5 is required for lignification of the Brachypodium distachyon Culm. Plant Physiol. 2015, 168, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarino, I.; Araujo, P.; Sampaio Mayer, J.L.; Vicentini, R.; Berthet, S.; Demedts, B.; Vanholme, B.; Boerjan, W.; Mazzafera, P. Expression of SofLAC, a new laccase in sugarcane, restores lignin content but not S:G ratio of Arabidopsis lac17 mutant. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1769–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Zhang, X.L.; Luo, H.H.; Zhou, J.J.; Gong, Y.H.; Li, W.J.; Shi, Z.W.; He, Q.; Wu, Q.; Li, L.; et al. An intracellular laccase Is responsible for epicatechin-mediated anthocyanin degradation in litchi fruit pericarp. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 2391–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Xu, C.J.; Yin, X.R.; Shan, L.L.; Ferguson, I.; Chen, K.S. Ethylene signal transduction elements involved in chilling injury in non-climacteric loquat fruit. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Dai, W.S.; Du, J.; Ming, R.H.; Dahro, B.; Liu, J.H. ERF109 of trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata (L.) Raf.) contributes to cold tolerance by directly regulating expression of Prx1 involved in antioxidative process. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1316–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.Z.; Chen, C.W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.H.; Moriguchi, T. Ectopic expression of MdSPDS1 in sweet orange (Citrus sinensis Osbeck) reduces canker susceptibility: Involvement of H2O2 production and transcriptional alteration. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, Y.W.; Luo, L.; Lu, C.Y.; Kong, W.W.; Cheng, L.B.; Xu, X.Y.; Liu, J.H. Genome wide identification of respiratory burst oxidase homolog (Rboh) genes in Citrus sinensis and functional analysis of CsRbohD in cold tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Fu, X.Z.; Peng, T.; Huang, X.S.; Fan, Q.J.; Liu, J.H. Spermine pretreatment confers dehydration tolerance of citrus in vitro plants via modulation of antioxidative capacity and stomatal response. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.H. A basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, PtrbHLH, of Poncirus trifoliata confers cold tolerance and modulates peroxidase-mediated scavenging of hydrogen peroxide. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1178–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, M.; Kong, W.; Liu, J. The Citrus Laccase Gene CsLAC18 Contributes to Cold Tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314509

Xu X, Zhang Y, Liang M, Kong W, Liu J. The Citrus Laccase Gene CsLAC18 Contributes to Cold Tolerance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(23):14509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314509

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Xiaoyong, Yueliang Zhang, Mengge Liang, Weiwen Kong, and Jihong Liu. 2022. "The Citrus Laccase Gene CsLAC18 Contributes to Cold Tolerance" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 23: 14509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314509

APA StyleXu, X., Zhang, Y., Liang, M., Kong, W., & Liu, J. (2022). The Citrus Laccase Gene CsLAC18 Contributes to Cold Tolerance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(23), 14509. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232314509