Microbiome-Based Metabolic Therapeutic Approaches in Alcoholic Liver Disease

Abstract

:1. Introduction

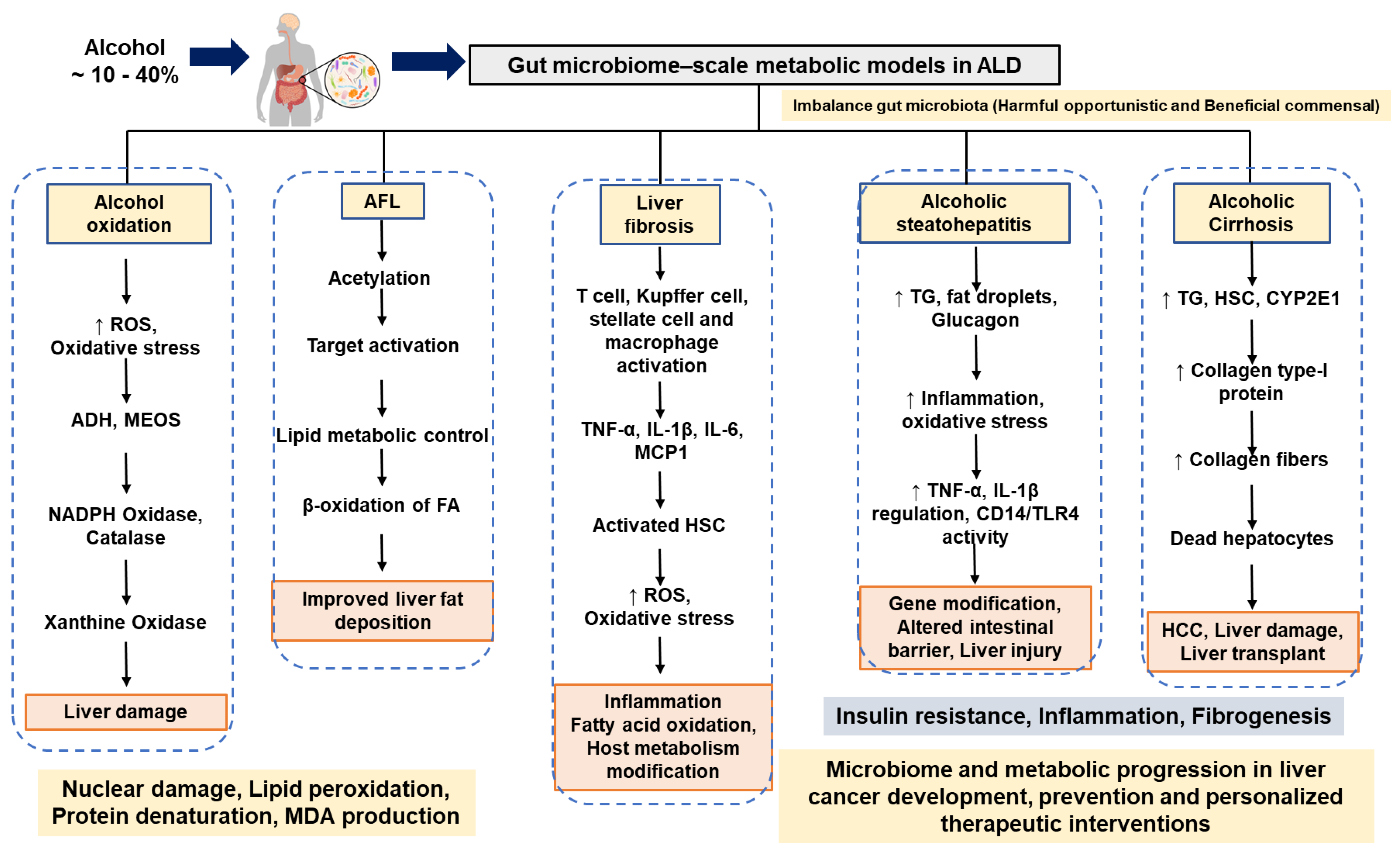

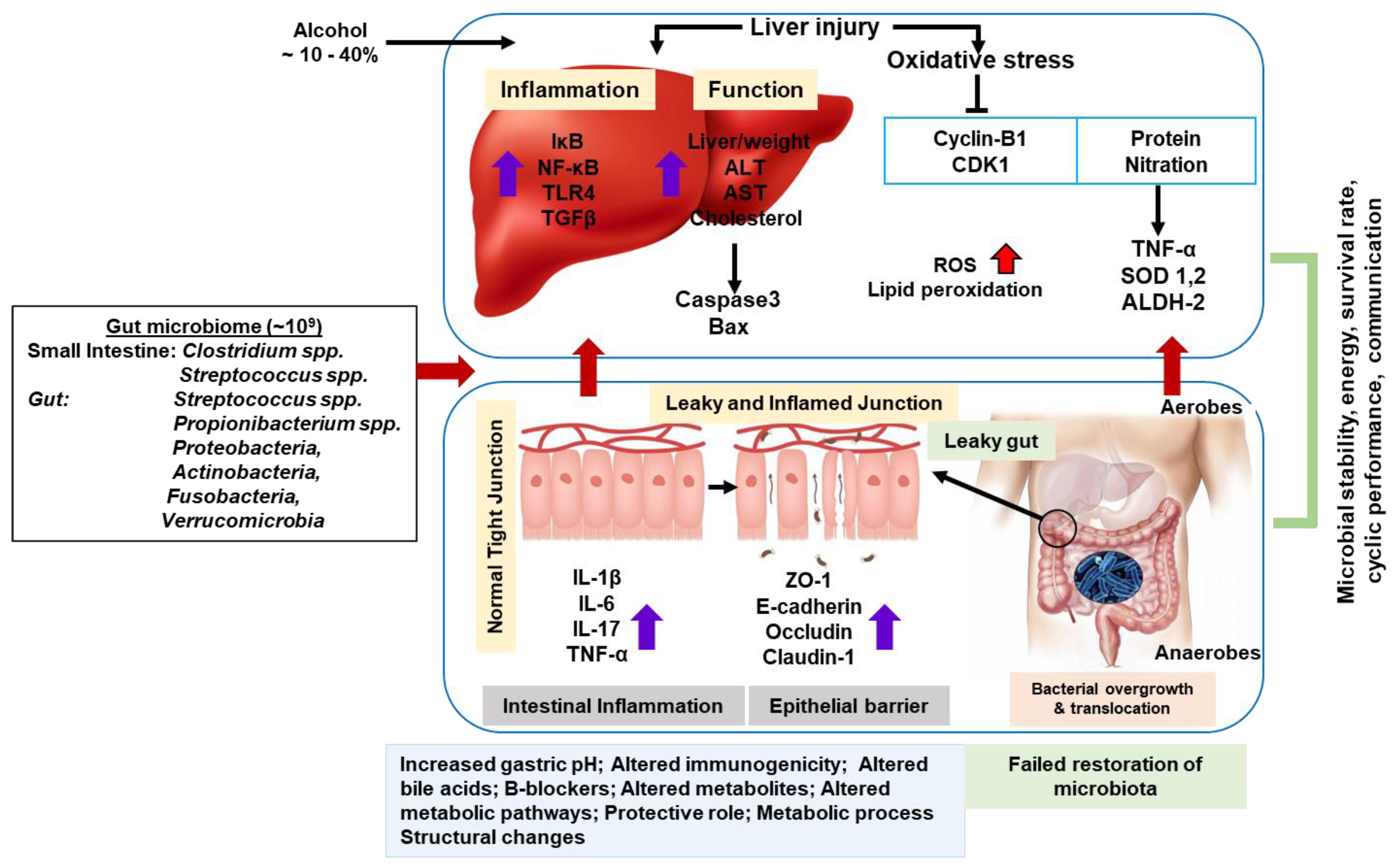

2. Oxidative Stress Formation in ALD

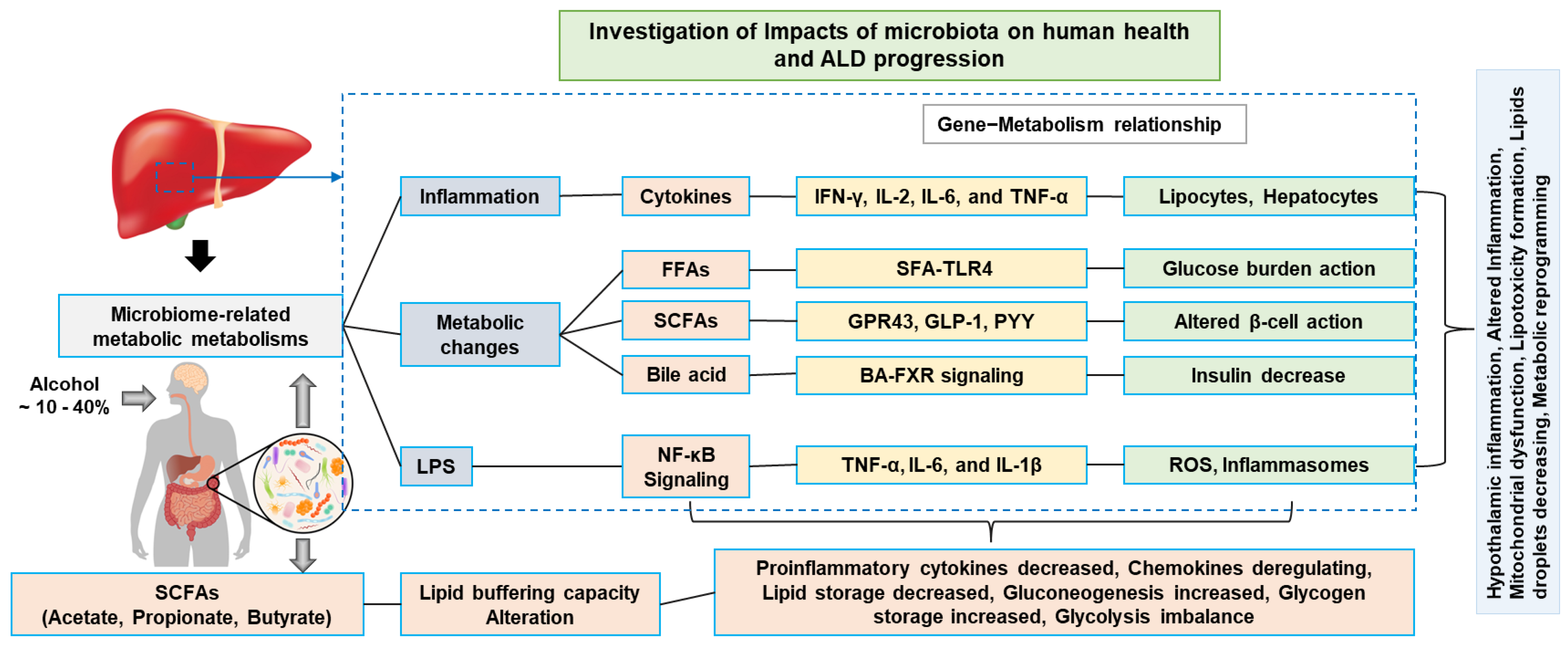

3. Alcohol-Induced Metabolic Inflammation and Cellular Alterations

4. Alcoholic Liver Diseases

4.1. Alcoholic Fatty Liver and Molecular Networking

4.2. Alcoholic Liver Fibrosis in Humans with Alcoholism

4.3. Alcoholic Steatohepatitis in Humans with Alcoholism

4.4. Alcoholic Cirrhosis in Humans with Alcoholism

4.5. Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Humans with Alcoholism

5. Probiotics and Antioxidant Activity in ALD

6. Microbiome-Wide Dynamic Microbial Proof-of-Concept Clinical Validation

7. Summary and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Are we really vastly outnumbered? Revisiting the ratio of bacterial to host cells in humans. Cell 2016, 164, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tierney, B.T.; Yang, Z.; Luber, J.M.; Beaudin, M.; Wibowo, M.C.; Baek, C.; Mehlenbacher, E.; Patel, C.J.; Kostic, A.D. The landscape of genetic content in the gut and oral human microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 283–295.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Lukiw, W. Alzheimer’s disease and the microbiome. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schnabl, B.; Brenner, D.A. Interactions between the intestinal microbiome and liver diseases. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1513–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganesan, R.; Jeong, J.-J.; Kim, D.J.; Suk, K.T. Recent trends of microbiota-based microbial metabolites metabolism in liver disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, G. Gut-liver axis in alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Veith, A.; Moorthy, B. Role of cytochrome p450s in the generation and metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, G.; Gupta, H.; Gebru, Y.A.; Youn, G.S.; Choi, Y.R.; Kim, H.S.; Yoon, S.J.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, T.-J.; Suk, K.T. Recent advances of microbiome-associated metabolomics profiling in liver disease: Principles, mechanisms, and applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, V.; Putluri, N.; Sreekumar, A.; Mindikoglu, A.L. Current applications of metabolomics in cirrhosis. Metabolites 2018, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ley, R.E.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Klein, S.; Gordon, J.I. Microbial ecology: Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 2006, 444, 1022–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.; Bik, E.M.; DiGiulio, D.B.; Relman, D.A.; Brown, P.O. Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choi, Y.R.; Kim, H.S.; Yoon, S.J.; Lee, N.Y.; Gupta, H.; Raja, G.; Gebru, Y.A.; Youn, G.S.; Kim, D.J.; Ham, Y.L.; et al. Nutritional status and diet style affect cognitive function in alcoholic liver disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuma, D.J.; Casey, C.A. Dangerous byproducts of alcohol breakdown—Focus on adducts. Alcohol Res. Health J. Natl. Inst. Alcohol Abus. Alcohol. 2003, 27, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sarsour, E.H.; Kumar, M.G.; Chaudhuri, L.; Kalen, A.L.; Goswami, P.C. Redox control of the cell cycle in health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009, 11, 2985–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldar, S.; Khaniani, M.S.; Derakhshan, S.M.; Baradaran, B. Molecular mechanisms of apoptosis and roles in cancer development and treatment. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2015, 16, 2129–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hagymási, K.; Blázovics, A.; Lengyel, G.; Kocsis, I.; Fehér, J. Oxidative damage in alcoholic liver disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2001, 13, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Rey, M.; Woodhoo, A.; Martinez-Chantar, M.-L.; Mato, J.M.; Lu, S.C. Alcohol, DNA methylation, and cancer. Alcohol. Res. 2013, 35, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, G.; Jang, Y.-K.; Suh, J.-S.; Prabhakaran, V.-S.; Kim, T.-J. Advanced understanding of genetic risk and metabolite signatures in construction workers via cytogenetics and metabolomics analysis. Process Biochem. 2019, 86, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylin, S.B.; Herman, J.G.; Graff, J.R.; Vertino, P.M.; Issa, J.P. Alterations in DNA methylation: A fundamental aspect of neoplasia. Adv. Cancer Res. 1998, 72, 141–196. [Google Scholar]

- Karthi, S.; Vasantha-Srinivasan, P.; Ganesan, R.; Ramasamy, V.; Senthil-Nathan, S.; Khater, H.F.; Radhakrishnan, N.; Amala, K.; Kim, T.-J.; El-Sheikh, M.A.; et al. Target activity of isaria tenuipes (hypocreales: Clavicipitaceae) fungal strains against dengue vector Aedes aegypti (linn.) and its non-target activity against aquatic predators. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.M.; Lu, S.C.; Van Den Berg, D.; Govindarajan, S.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Mato, J.M.; Yu, M.C. Genetic polymorphisms in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and thymidylate synthase genes and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2007, 46, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabris, C.; Toniutto, P.; Falleti, E.; Fontanini, E.; Cussigh, A.; Bitetto, D.; Fornasiere, E.; Fumolo, E.; Avellini, C.; Minisini, R.; et al. Mthfr c677t polymorphism and risk of hcc in patients with liver cirrhosis: Role of male gender and alcohol consumption. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009, 33, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzani, M.; Rosselli, M.; Zuckermann, M. Liver cirrhosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011, 25, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.-C.; Zhang, Q.-B.; Qiao, L. Pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2014, 20, 7312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruha, R.; Dvorak, K.; Petrtyl, J. Alcoholic liver disease. World J. Hepatol. 2012, 4, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, J.; Han, J.; Lee, C.; Yoon, M.; Jung, Y. Pathophysiological aspects of alcohol metabolism in the liver. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffert, C.S.; Duryee, M.J.; Hunter, C.D.; Hamilton, B.C., 3rd; DeVeney, A.L.; Huerter, M.M.; Klassen, L.W.; Thiele, G.M. Alcohol metabolites and lipopolysaccharide: Roles in the development and/or progression of alcoholic liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2009, 15, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Setshedi, M.; Wands, J.R.; de la Monte, S.M. Acetaldehyde adducts in alcoholic liver disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2010, 3, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, B.; Bataller, R. Alcoholic liver disease: Pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1572–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, A.W.; Fouts, D.E.; Brandl, J.; Stärkel, P.; Torralba, M.; Schott, E.; Tsukamoto, H.; Nelson, K.E.; Brenner, D.A.; Schnabl, B. Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2011, 53, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, R.M.; Luo, L.; Ardita, C.S.; Richardson, A.N.; Kwon, Y.M.; Mercante, J.W.; Alam, A.; Gates, C.L.; Wu, H.; Swanson, P.A.; et al. Symbiotic lactobacilli stimulate gut epithelial proliferation via nox-mediated generation of reactive oxygen species. EMBO J. 2013, 32, 3017–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schroder, K.; Tschopp, J. The inflammasomes. Cell 2010, 140, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cayrol, C.; Girard, J.-P. The il-1-like cytokine il-33 is inactivated after maturation by caspase-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 9021–9026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinon, F.; Mayor, A.; Tschopp, J. The inflammasomes: Guardians of the body. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 27, 229–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valles, S.L.; Blanco, A.M.; Azorin, I.; Guasch, R.; Pascual, M.; Gomez-Lechon, M.J.; Renau-Piqueras, J.; Guerri, C. Chronic ethanol consumption enhances interleukin-1-mediated signal transduction in rat liver and in cultured hepatocytes. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2003, 27, 1979–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Ajmo, J.M.; Rogers, C.Q.; Liang, X.; Le, L.; Murr, M.M.; Peng, Y.; You, M. Role of sirt1 in regulation of lps- or two ethanol metabolites-induced tnf-alpha production in cultured macrophage cell lines. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009, 296, G1047–G1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, J.; Room, R.; Monteiro, M.; Gmel, G.; Graham, K.; Rehn, N.; Sempos, C.T.; Jernigan, D. Alcohol as a risk factor for global burden of disease. Eur. Addict. Res. 2003, 9, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, R.; Sinclair, J.M. Alcohol use disorder and the liver. Addiction 2021, 116, 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, M.G.; Fullman, N.; Hawley, C.; Arian, N.; Zimsen, S.R.; Tymeson, H.D.; Venkateswaran, V.; Tapp, A.D.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Salama, J.S. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X.; Yin, P.; Zhu, J.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in china and its provinces, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 2019, 394, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flemming, J.A.; Djerboua, M.; Groome, P.A.; Booth, C.M.; Terrault, N.A. Nafld and alcohol-related liver disease will be responsible for almost all new diagnoses of cirrhosis in canada by 2040. Hepatology 2021, 74, 3330–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asrani, S.K.; Mellinger, J.; Arab, J.P.; Shah, V.H. Reducing the global burden of alcohol-associated liver disease: A blueprint for action. Hepatology 2021, 73, 2039–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, S.-M.; Park, E.; Jung, J.-J.; Ganesan, R.; Gupta, H.; Gebru, Y.A.; Sharma, S.; Kim, D.-J.; Suk, K.-T. The gut microbiota-derived immune response in chronic liver disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Arora, A. Clinical presentation of alcoholic liver disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Spectrum and diagnosis. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, C.S. Hepatic and metabolic effects of ethanol: Pathogenesis and prevention. Ann. Med. 1994, 26, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Li, L.; Hu, H.Q.; Meng, X.M.; Huang, C.; Zhang, L.; Qin, J.; Li, J. Micrornas in alcoholic liver disease: Recent advances and future applications. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 234, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stickel, F.; Hampe, J. Genetic determinants of alcoholic liver disease. Gut 2012, 61, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoruts, A.; Stahnke, L.; McClain, C.J.; Logan, G.; Allen, J.I. Circulating tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 concentrations in chronic alcoholic patients. Hepatology 1991, 13, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, K.V.; Gores, G.J.; Shah, V.H. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of alcoholic liver disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2001, 76, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szabo, G.; Petrasek, J.; Bala, S. Innate immunity and alcoholic liver disease. Dig. Dis. 2012, 30 (Suppl. S1), 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrasek, J.; Mandrekar, P.; Szabo, G. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2010, 2010, 710381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louvet, A.; Mathurin, P. Alcoholic liver disease: Mechanisms of injury and targeted treatment. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missiroli, S.; Patergnani, S.; Caroccia, N.; Pedriali, G.; Perrone, M.; Previati, M.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Giorgi, C. Mitochondria-associated membranes (mams) and inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, S.; McPhaul, C.; Li, J.Z.; Garuti, R.; Kinch, L.; Grishin, N.V.; Cohen, J.C.; Hobbs, H.H. A sequence variation (i148m) in pnpla3 associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease disrupts triglyceride hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 6706–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartmann, P.; Chen, P.; Wang, H.J.; Wang, L.; McCole, D.F.; Brandl, K.; Stärkel, P.; Belzer, C.; Hellerbrand, C.; Tsukamoto, H.; et al. Deficiency of intestinal mucin-2 ameliorates experimental alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2013, 58, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Heuman, D.M.; Hylemon, P.B.; Sanyal, A.J.; White, M.B.; Monteith, P.; Noble, N.A.; Unser, A.B.; Daita, K.; Fisher, A.R.; et al. Altered profile of human gut microbiome is associated with cirrhosis and its complications. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Lu, H.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Lei, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Li, L. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2011, 54, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, N.; Tan, H.Y.; Chueng, F.; Zhang, Z.J.; Yuen, M.F.; Feng, Y. Modulation of gut microbiota mediates berberine-induced expansion of immuno-suppressive cells to against alcoholic liver disease. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020, 10, e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Hochrath, K.; Horvath, A.; Chen, P.; Seebauer, C.T.; Llorente, C.; Wang, L.; Alnouti, Y.; Fouts, D.E.; Stärkel, P. Modulation of the intestinal bile acid/farnesoid X receptor/fibroblast growth factor 15 axis improves alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology 2018, 67, 2150–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, A.; Lowe, P.; Kodys, K.; Catalano, D.; Gyongyosi, B.; Cho, Y.; Iracheta-Vellve, A.; Adejumo, A.; Saha, B.; Calenda, C. Pharmacological inhibition of ccr2/5 signaling prevents and reverses alcohol-induced liver damage, steatosis, and inflammation in mice. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, Y.; Moore, L.E.; Bradford, B.U.; Gao, W.; Thurman, R.G. Antibiotics prevent liver injury in rats following long-term exposure to ethanol. Gastroenterology 1995, 108, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, K.; Tsukamoto, H.; Mkrtchyan, H.; Duan, L.; Dynnyk, A.; Liu, H.M.; Asahina, K.; Govindarajan, S.; Ray, R.; Ou, J.H.; et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates synergism between alcohol and hcv in hepatic oncogenesis involving stem cell marker nanog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1548–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Zheng, L.; Liu, S.; Guo, X.; Qu, Y.; Gao, M.; Cui, X.; Yang, Y. A novel acidic polysaccharide from the residue of panax notoginseng and its hepatoprotective effect on alcoholic liver damage in mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 149, 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, V.; Pritchard, M.T.; McMullen, M.R.; Wang, Q.; Nagy, L.E. Chronic ethanol feeding increases activation of nadph oxidase by lipopolysaccharide in rat kupffer cells: Role of increased reactive oxygen in lps-stimulated erk1/2 activation and tnf-alpha production. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 79, 1348–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, X.; Wei, X.; Yin, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, C.; Zhao, H.; McClain, C.J.; Feng, W.; Zhang, X. Hepatic and fecal metabolomic analysis of the effects of lactobacillus rhamnosus gg on alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, S.; Cheng, C.; Peng, Z.; Xu, L. Differential metabolic pathways and metabolites in a c57bl/6j mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e924602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-D.; Huang, Z.-W.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Huang, J.-F.; Zhang, Z.-P.; Lin, X.-J. Untargeted metabolomic profiling of liver in a chronic intermittent hypoxia mouse model. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 701035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Wen, Z.; Meng, K.; Yang, P. Metabolomic signatures for liver tissue and cecum contents in high-fat diet-induced obese mice based on uhplc-q-tof/ms. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 18, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Meng, H.-Y.; Liu, S.-M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.-X.; Lu, F.; Wang, H.-Y. Identification of key metabolic changes during liver fibrosis progression in rats using a urine and serum metabolomics approach. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, M.; Du, X.; Xu, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, W. Metabolic profiling of liver and faeces in mice infected with echinococcosis. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.; Hardesty, J.; Song, Y.; Sun, R.; Deng, Z.; Xu, R.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; McClain, C.; Warner, D.; et al. Fat-1 transgenic mice with augmented n3-polyunsaturated fatty acids are protected from liver injury caused by acute-on-chronic ethanol administration. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 711590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataller, R.; Brenner, D.A. Liver fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubero, F.J.; Urtasun, R.; Nieto, N. Alcohol and liver fibrosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 2009, 29, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.; Jeong, J.-J.; Won, S.-M.; Sharma, S.P.; Gebru, Y.A.; Ganesan, R.; Gupta, H.; Suk, K.T.; Kim, D.J. Gut microbiota-related cellular and molecular mechanisms in the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cells 2021, 10, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, M.; Bataller, R. Cytokines and renin-angiotensin system signaling in hepatic fibrosis. Clin. Liver Dis. 2008, 12, 825–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firrincieli, D.; Boissan, M.; Chignard, N. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the liver. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 2010, 34, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, J.S.; Hylemon, P.B.; Ridlon, J.M.; Heuman, D.M.; Daita, K.; White, M.B.; Monteith, P.; Noble, N.A.; Sikaroodi, M.; Gillevet, P.M. Colonic mucosal microbiome differs from stool microbiome in cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy and is linked to cognition and inflammation. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 303, G675–G685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirpich, I.A.; Solovieva, N.V.; Leikhter, S.N.; Shidakova, N.A.; Lebedeva, O.V.; Sidorov, P.I.; Bazhukova, T.A.; Soloviev, A.G.; Barve, S.S.; McClain, C.J.; et al. Probiotics restore bowel flora and improve liver enzymes in human alcohol-induced liver injury: A pilot study. Alcohol 2008, 42, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carithers, R.L., Jr.; Herlong, H.F.; Diehl, A.M.; Shaw, E.W.; Combes, B.; Fallon, H.J.; Maddrey, W.C. Methylprednisolone therapy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. A randomized multicenter trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1989, 110, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldt, B.J.; Lainé, F.; Guillygomarc’h, A.; Lauvin, L.; Boudjema, K.; Messner, M.; Brissot, P.; Deugnier, Y.; Moirand, R. Indication of liver transplantation in severe alcoholic liver cirrhosis: Quantitative evaluation and optimal timing. J. Hepatol. 2002, 36, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrao, G.; Aricò, S. Independent and combined action of hepatitis c virus infection and alcohol consumption on the risk of symptomatic liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 1998, 27, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, S.J.; Bird, S.M.; Goldberg, D.J. Influence of alcohol on the progression of hepatitis c virus infection: A meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2005, 3, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punzalan, C.S.; Bukong, T.N.; Szabo, G. Alcoholic hepatitis and hcv interactions in the modulation of liver disease. J. Viral Hepat. 2015, 22, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sokol, H.; Pigneur, B.; Watterlot, L.; Lakhdari, O.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Gratadoux, J.-J.; Blugeon, S.; Bridonneau, C.; Furet, J.-P.; Corthier, G.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of crohn disease patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16731–16736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gleeson, D.; Evans, S.; Bradley, M.; Jones, J.; Peck, R.J.; Dube, A.; Rigby, E.; Dalton, A. Hfe genotypes in decompensated alcoholic liver disease: Phenotypic expression and comparison with heavy drinking and with normal controls. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strieter, R.M.; Remick, D.G.; Ward, P.A.; Spengler, R.N.; Lynch, J.P., 3rd; Larrick, J.; Kunkel, S.L. Cellular and molecular regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by pentoxifylline. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988, 155, 1230–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morgan, T.R.; McClain, C.J. Pentoxifylline and alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 1787–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akriviadis, E.; Botla, R.; Briggs, W.; Han, S.; Reynolds, T.; Shakil, O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 1637–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreno, C.; Langlet, P.; Hittelet, A.; Lasser, L.; Degré, D.; Evrard, S.; Colle, I.; Lemmers, A.; Devière, J.; Le Moine, O. Enteral nutrition with or without n-acetylcysteine in the treatment of severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: A randomized multicenter controlled trial. J. Hepatol. 2010, 53, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; Prince, M.; Bassendine, M.; Hudson, M.; James, O.; Jones, D.; Record, C.; Day, C.P. A randomized trial of antioxidant therapy alone or with corticosteroids in acute alcoholic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2007, 47, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.; Curtis, H.; Portmann, B.; Donaldson, N.; Bomford, A.; O’Grady, J. Antioxidants versus corticosteroids in the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis—A randomised clinical trial. J. Hepatol. 2006, 44, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen-Khac, E.; Thevenot, T.; Piquet, M.A.; Benferhat, S.; Goria, O.; Chatelain, D.; Tramier, B.; Dewaele, F.; Ghrib, S.; Rudler, M.; et al. Glucocorticoids plus n-acetylcysteine in severe alcoholic hepatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rambaldi, A.; Gluud, C. Anabolic-androgenic steroids for alcoholic liver disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 2006, Cd003045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, Y.; Kalant, H.; Orrego, H.; Khanna, J.M.; Videla, L.; Phillips, J.M. Experimental alcohol-induced hepatic necrosis: Suppression by propylthiouracil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iturriaga, H.; Ugarte, G.; Israel, Y. Hepatic vein oxygenation, liver blood flow, and the rate of ethanol metabolism in recently abstinent alcoholic patients. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 1980, 10, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettle, A.J.; Gedye, C.A.; Winterbourn, C.C. Mechanism of inactivation of myeloperoxidase by 4-aminobenzoic acid hydrazide. Biochem. J. 1997, 321 Pt 2, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaldi, A.; Gluud, C. Propylthiouracil for alcoholic liver disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, Cd002800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fede, G.; Germani, G.; Gluud, C.; Gurusamy, K.S.; Burroughs, A.K. Propylthiouracil for alcoholic liver disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, C.L.; Moritz, T.E.; Roselle, G.A.; Morgan, T.R.; Nemchausky, B.A.; Tamburro, C.H.; Schiff, E.R.; McClain, C.J.; Marsano, L.S.; Allen, J.I.; et al. A study of oral nutritional support with oxandrolone in malnourished patients with alcoholic hepatitis: Results of a department of veterans affairs cooperative study. Hepatology 1993, 17, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.F.; Carithers, R.L., Jr. Aasld practice guidelines: Evaluation of the patient for liver transplantation. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1407–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, K.G.; Zimmerman, H.J.; Ray, M.B. Alcoholic liver disease: Pathologic, pathogenetic and clinical aspects. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1991, 15, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chedid, A.; Mendenhall, C.L.; Gartside, P.; French, S.W.; Chen, T.; Rabin, L. Prognostic factors in alcoholic liver disease. Va cooperative study group. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1991, 86, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niemelä, O.; Juvonen, T.; Parkkila, S. Immunohistochemical demonstration of acetaldehyde-modified epitopes in human liver after alcohol consumption. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 87, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Theruvathu, J.A.; Jaruga, P.; Nath, R.G.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Brooks, P.J. Polyamines stimulate the formation of mutagenic 1,n2-propanodeoxyguanosine adducts from acetaldehyde. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 3513–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seitz, H.K.; Stickel, F. Risk factors and mechanisms of hepatocarcinogenesis with special emphasis on alcohol and oxidative stress. Biol. Chem. 2006, 387, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Millonig, G.; Nair, J.; Patsenker, E.; Stickel, F.; Mueller, S.; Bartsch, H.; Seitz, H.K. Ethanol-induced cytochrome p4502e1 causes carcinogenic etheno-DNA lesions in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 2009, 50, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, E. Alcohol, oxidative stress and free radical damage. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2006, 65, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lieber, C.S. Cytochrome p-4502e1: Its physiological and pathological role. Physiol. Rev. 1997, 77, 517–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, I.; Lucas, D.; Clot, P.; Ménez, C.; Albano, E. Cytochrome p4502e1 inducibility and hydroxyethyl radical formation among alcoholics. J. Hepatol. 1998, 28, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, D.; Gorrell, M.D.; Cordoba, S.; McCaughan, G.W.; Haber, P.S. Intrahepatic gene expression in human alcoholic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2006, 45, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaschek, R.; McCuskey, R.S.; Rudi, V.; Becker, K.P.; Stickel, F.; Urbaschek, B.; Seitz, H.K. Endotoxin, endotoxin-neutralizing-capacity, scd14, sicam-1, and cytokines in patients with various degrees of alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2001, 25, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebru, Y.A.; Choi, M.R.; Raja, G.; Gupta, H.; Sharma, S.P.; Choi, Y.R.; Kim, H.S.; Yoon, S.J.; Kim, D.J.; Suk, K.T. Pathophysiological roles of mucosal-associated invariant t cells in the context of gut microbiota-liver axis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurman, R.G., II. Alcoholic liver injury involves activation of kupffer cells by endotoxin. Am. J. Physiol. 1998, 275, G605–G611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardag-Gorce, F.; Li, J.; French, B.A.; French, S.W. The effect of ethanol-induced cyp2e1 on proteasome activity: The role of 4-hydroxynonenal. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2005, 78, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, H.K.; Gudmundsdottir, V.; Nielsen, H.B.; Hyotylainen, T.; Nielsen, T.; Jensen, B.A.; Forslund, K.; Hildebrand, F.; Prifti, E.; Falony, G.; et al. Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature 2016, 535, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanji, A.A.; Khettry, U.; Sadrzadeh, S.M. Lactobacillus feeding reduces endotoxemia and severity of experimental alcoholic liver (disease). Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1994, 205, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, C.B.; Farhadi, A.; Jakate, S.M.; Tang, Y.; Shaikh, M.; Keshavarzian, A. Lactobacillus gg treatment ameliorates alcohol-induced intestinal oxidative stress, gut leakiness, and liver injury in a rat model of alcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol 2009, 43, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.S.; Eun, J.W.; Cho, H.J.; Song, D.S.; Kim, C.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, Y.K.; Yang, J.; Choi, J.; et al. Microbiome as a potential diagnostic and predictive biomarker in severe alcoholic hepatitis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 53, 540–551. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Vatsalya, V.; Gobejishvili, L.; Lamont, R.J.; McClain, C.J.; Feng, W. Porphyromonas gingivalis as a possible risk factor in the development/severity of acute alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatol. Commun. 2019, 3, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, D.; Zhai, Q.; Shi, X. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress and cell responses. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 21, S26–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, Y.-M.; Kong, L.-B.; Ren, W.-G.; Wang, R.-Q.; Du, J.-H.; Li, W.-C.; Zhao, S.-X.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Wu, W.-J.; Di, H.-L. Activation of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha ameliorates ethanol mediated liver fibrosis in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2013, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nieto, N.; Friedman, S.L.; Cederbaum, A.I. Cytochrome p450 2e1-derived reactive oxygen species mediate paracrine stimulation of collagen i protein synthesis by hepatic stellate cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 9853–9864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rasineni, K.; Donohue, T.M., Jr.; Thomes, P.G.; Yang, L.; Tuma, D.J.; McNiven, M.A.; Casey, C.A. Ethanol-induced steatosis involves impairment of lipophagy, associated with reduced dynamin2 activity. Hepatol. Commun. 2017, 1, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tuma, D.J. Role of malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts in liver injury. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 32, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuma, D.J.; Thiele, G.M.; Xu, D.; Klassen, L.W.; Sorrell, M.F. Acetaldehyde and malondialdehyde react together to generate distinct protein adducts in the liver during long-term ethanol administration. Hepatology 1996, 23, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nlemelä, O.; Parkkila, S.; Ylä-herttuala, S.; Villanueva, J.; Ruebner, B.; Halsted, C.H. Sequential acetaldehyde production, lipid peroxidation, and fibrogenesis in micropig model of alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology 1995, 22, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamimura, S.; Gaal, K.; Britton, R.S.; Bacon, B.R.; Triadafilopoulos, G.; Tsukamoto, H. Increased 4-hydroxynonenal levels in experimental alcoholic liver disease: Association of lipid peroxidation with liver fibrogenesis. Hepatology 1992, 16, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, C.; Silvestri, C.; Voller, F.; Cipriani, F. Epidemiology of liver cirrhosis. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2015, 5, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehm, J.; Taylor, B.; Mohapatra, S.; Irving, H.; Baliunas, D.; Patra, J.; Roerecke, M. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010, 29, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatsuhashi, H.; Sano, H.; Hirano, T.; Shibasaki, Y. Real-world hospital mortality of liver cirrhosis inpatients in japan: A large-scale cohort study using a medical claims database: Prognosis of liver cirrhosis. Hepatol. Res. 2021, 51, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Shasthry, S.M.; Choudhury, A.K.; Maiwall, R.; Kumar, G.; Bharadwaj, A.; Arora, V.; Vijayaraghavan, R.; Jindal, A.; Sharma, M.K. Alcohol associated liver cirrhotics have higher mortality after index hospitalization: Long-term data of 5,138 patients. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2021, 27, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regier, D.A.; Kuhl, E.A.; Kupfer, D.J. The dsm-5: Classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry Off. J. World Psychiatr. Assoc. (WPA) 2013, 12, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tuomisto, S.; Pessi, T.; Collin, P.; Vuento, R.; Aittoniemi, J.; Karhunen, P.J. Changes in gut bacterial populations and their translocation into liver and ascites in alcoholic liver cirrhotics. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- El-Serag, H.B. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocan, T.; Simão, A.L.; Castro, R.E.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Słomka, A.; Wang, B.; Strassburg, C.; Wöhler, A.; Willms, A.G.; Kornek, M. Liquid biopsies in hepatocellular carcinoma: Are we winning? J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, H.K.; Stickel, F. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-mediated carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, H.; Youn, G.S.; Shin, M.J.; Suk, K.T. Role of gut microbiota in hepatocarcinogenesis. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duque Correa, M.A.; Rojas López, M. Activación alternativa del macrófago: La diversidad en las respuestas de una célula de la inmunidad innata ante la complejidad de los eventos de su ambiente. Inmunología 2007, 26, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Serag, H.B.; Rudolph, K.L. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 2557–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschke, R. Alcoholic liver disease: Current mechanistic aspects with focus on their clinical relevance. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saffroy, R.; Pham, P.; Chiappini, F.; Gross-Goupil, M.; Castera, L.; Azoulay, D.; Barrier, A.; Samuel, D.; Debuire, B.; Lemoine, A. The mthfr 677c > t polymorphism is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Carcinogenesis 2004, 25, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leclercq, S.; Cani, P.D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Stärkel, P.; Jamar, F.; Mikolajczak, M.; Delzenne, N.M.; de Timary, P. Role of intestinal permeability and inflammation in the biological and behavioral control of alcohol-dependent subjects. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabherr, F.; Grander, C.; Adolph, T.E.; Wieser, V.; Mayr, L.; Enrich, B.; Macheiner, S.; Sangineto, M.; Reiter, A.; Viveiros, A.; et al. Ethanol-mediated suppression of il-37 licenses alcoholic liver disease. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2018, 38, 1095–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-J.; Pan, Q.-Z.; Pan, K.; Weng, D.-S.; Wang, Q.-J.; Li, J.-J.; Lv, L.; Wang, D.-D.; Zheng, H.-X.; Jiang, S.-S.; et al. Interleukin-37 mediates the antitumor activity in hepatocellular carcinoma: Role for cd57+ nk cells. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nezami Ranjbar, M.R.; Luo, Y.; Di Poto, C.; Varghese, R.S.; Ferrarini, A.; Zhang, C.; Sarhan, N.I.; Soliman, H.; Tadesse, M.G.; Ziada, D.H.; et al. Gc-ms based plasma metabolomics for identification of candidate biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma in egyptian cohort. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127299. [Google Scholar]

- Safaei, A.; Arefi Oskouie, A.; Mohebbi, S.R.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Mahboubi, M.; Peyvandi, M.; Okhovatian, F.; Zamanian-Azodi, M. Metabolomic analysis of human cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis diseases. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2016, 9, 158–173. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.X.; Schwabe, R.F. The gut microbiome and liver cancer: Mechanisms and clinical translation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapito, D.H.; Mencin, A.; Gwak, G.Y.; Pradere, J.P.; Jang, M.K.; Mederacke, I.; Caviglia, J.M.; Khiabanian, H.; Adeyemi, A.; Bataller, R.; et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and tlr4. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Toyoda, H.; Komurasaki, T.; Uchida, D.; Takayama, Y.; Isobe, T.; Okuyama, T.; Hanada, K. Epiregulin. A novel epidermal growth factor with mitogenic activity for rat primary hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 7495–7500. [Google Scholar]

- Uesugi, T.; Froh, M.; Arteel, G.E.; Bradford, B.U.; Thurman, R.G. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the mechanism of early alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology 2001, 34, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Wang, X.; Sun, C.; Zheng, X.; Wei, H.; Tian, Z.; Sun, R. Chronic alcohol consumption promotes diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis via immune disturbances. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, M.; Uemura, M.; Nakatani, Y.; Tsujita, S.; Hoppo, K.; Tamagawa, T.; Kitano, H.; Kikukawa, M.; Ann, T.; Ishii, Y.; et al. Plasma endotoxin and serum cytokine levels in patients with alcoholic hepatitis: Relation to severity of liver disturbance. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2000, 24, 48s–54s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Xie, M.; Hou, Y.; Ma, W.; Jin, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, C.; Zhao, K.; Chen, N.; Xu, L. A novel epigenetic mechanism unravels hsa-mir-148a-3p-mediated cyp2b6 downregulation in alcoholic hepatitis disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 188, 114582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artru, F.; Saleh, M.B.; Maggiotto, F.; Lassailly, G.; Ningarhari, M.; Demaret, J.; Ntandja-Wandji, L.-C.; de Barros, J.-P.P.; Labreuche, J.; Drumez, E. Il-33/st2 pathway regulates neutrophil migration and predicts outcome in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bauer, T.M.; Schwacha, H.; Steinbrückner, B.; Brinkmann, F.E.; Ditzen, A.K.; Aponte, J.J.; Pelz, K.; Berger, D.; Kist, M.; Blum, H.E. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in human cirrhosis is associated with systemic endotoxemia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 97, 2364–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, D.B.; Barve, S.; Joshi-Barve, S.; McClain, C. Increased monocyte nuclear factor-kappab activation and tumor necrosis factor production in alcoholic hepatitis. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2000, 135, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Liao, Y.; Yin, P.; Zeng, Z.; Li, J.; Lu, X.; Zheng, L.; Xu, G. Metabolic profiling study of early and late recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma based on liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2014, 966, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Nahon, P.; Li, Z.; Yin, P.; Li, Y.; Amathieu, R.; Ganne-Carrié, N.; Ziol, M.; Sellier, N.; Seror, O.; et al. Determination of candidate metabolite biomarkers associated with recurrence of hcv-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 6245–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baniasadi, H.; Gowda, G.A.; Gu, H.; Zeng, A.; Zhuang, S.; Skill, N.; Maluccio, M.; Raftery, D. Targeted metabolic profiling of hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis c using lc-ms/ms. Electrophoresis 2013, 34, 2910–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusial, R.D.; Cioffi, C.E.; Caltharp, S.A.; Krasinskas, A.M.; Alazraki, A.; Knight-Scott, J.; Cleeton, R.; Castillo-Leon, E.; Jones, D.P.; Pierpont, B.; et al. Development of a plasma screening panel for pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease using metabolomics. Hepatol. Commun. 2019, 3, 1311–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meoni, G.; Lorini, S.; Monti, M.; Madia, F.; Corti, G.; Luchinat, C.; Zignego, A.L.; Tenori, L.; Gragnani, L. The metabolic fingerprints of hcv and hbv infections studied by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponziani, F.R.; Bhoori, S.; Castelli, C.; Putignani, L.; Rivoltini, L.; Del Chierico, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; Morelli, D.; Paroni Sterbini, F.; Petito, V.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with gut microbiota profile and inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2019, 69, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Wang, G.; Pang, Z.; Ran, N.; Gu, Y.; Guan, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zuo, X.; Pan, H.; Zheng, J.; et al. Liver cirrhosis contributes to the disorder of gut microbiota in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 4232–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grander, C.; Adolph, T.E.; Wieser, V.; Lowe, P.; Wrzosek, L.; Gyongyosi, B.; Ward, D.V.; Grabherr, F.; Gerner, R.R.; Pfister, A.; et al. Recovery of ethanol-induced akkermansia muciniphila depletion ameliorates alcoholic liver disease. Gut 2018, 67, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corb Aron, R.A.; Abid, A.; Vesa, C.M.; Nechifor, A.C.; Behl, T.; Ghitea, T.C.; Munteanu, M.A.; Fratila, O.; Andronie-Cioara, F.L.; Toma, M.M.; et al. Recognizing the benefits of pre-/probiotics in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus considering the influence of akkermansia muciniphila as a key gut bacterium. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull-Otterson, L.; Feng, W.; Kirpich, I.; Wang, Y.; Qin, X.; Liu, Y.; Gobejishvili, L.; Joshi-Barve, S.; Ayvaz, T.; Petrosino, J.; et al. Metagenomic analyses of alcohol induced pathogenic alterations in the intestinal microbiome and the effect of lactobacillus rhamnosus gg treatment. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-J.; Park, H.J.; Cha, M.G.; Park, E.; Won, S.-M.; Ganesan, R.; Gupta, H.; Gebru, Y.A.; Sharma, S.P.; Lee, S.B.; et al. The lactobacillus as a probiotic: Focusing on liver diseases. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenger, K.J.P.; Clermont-Dejean, N.; Allard, J.P. The role of the gut microbiome in chronic liver disease: The clinical evidence revised. JHEP Rep. 2019, 1, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishida, S.; Hamada, K.; Nishino, N.; Fukushima, D.; Koyanagi, R.; Horikawa, Y.; Shiwa, Y.; Saitoh, S. Efficacy of long-term rifaximin treatment for hepatic encephalopathy in the japanese. World J. Hepatol. 2019, 11, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.H.; Lee, Y.B.; Lee, J.H.; Nam, J.Y.; Chang, Y.; Cho, H.; Yoo, J.J.; Cho, Y.Y.; Cho, E.J.; Yu, S.J.; et al. Rifaximin treatment is associated with reduced risk of cirrhotic complications and prolonged overall survival in patients experiencing hepatic encephalopathy. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 46, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elfert, A.; Abo Ali, L.; Soliman, S.; Ibrahim, S.; Abd-Elsalam, S. Randomized-controlled trial of rifaximin versus norfloxacin for secondary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 1450–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalambokis, G.N.; Mouzaki, A.; Rodi, M.; Pappas, K.; Fotopoulos, A.; Xourgia, X.; Tsianos, E.V. Rifaximin improves systemic hemodynamics and renal function in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis and ascites. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2012, 10, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlachogiannakos, J.; Viazis, N.; Vasianopoulou, P.; Vafiadis, I.; Karamanolis, D.G.; Ladas, S.D. Long-term administration of rifaximin improves the prognosis of patients with decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 28, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariff, M.I.F.; Tognarelli, J.M.; Lewis, M.R.; Want, E.J.; Mohamed, F.E.Z.; Ladep, N.G.; Crossey, M.M.E.; Khan, S.A.; Jalan, R.; Holmes, E.; et al. Plasma lipid profiling in a rat model of hepatocellular carcinoma: Potential modulation through quinolone administration. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2015, 5, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ginés, P.; Rimola, A.; Planas, R.; Vargas, V.; Marco, F.; Almela, M.; Forné, M.; Miranda, M.L.; Llach, J.; Salmerón, J.M.; et al. Norfloxacin prevents spontaneous bacterial peritonitis recurrence in cirrhosis: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hepatology 1990, 12, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Navasa, M.; Gómez, J.; Colmenero, J.; Vila, J.; Arroyo, V.; Rodés, J. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: Epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology 2002, 35, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sung, C.Y.; Lee, N.; Ni, Y.; Pihlajamäki, J.; Panagiotou, G.; El-Nezami, H. Probiotics modulated gut microbiota suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma growth in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1306–E1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Delaune, V.; Orci, L.A.; Lacotte, S.; Peloso, A.; Schrenzel, J.; Lazarevic, V.; Toso, C. Fecal microbiota transplantation: A promising strategy in preventing the progression of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and improving the anti-cancer immune response. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2018, 18, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakhari, S. Overview: How is alcohol metabolized by the body? Alcohol Res. Health J. Natl. Inst. Alcohol Abus. Alcohol. 2006, 29, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

| Animals | Exposures | Main Results | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | C57BL/6J male (6–8 weeks old) | chronic 5% ethanol diet for 11, 22, and 33 days | (↑) AST, ALT, amount of G-MDSC. | [58] |

| C57BL/6 mice | alcohol diet for 8 weeks | (↑) proportions of CA, total MCA, DCA in ileum unconjugated and total bile acid concentrations in the plasma hepatic Cyp7a1 protein expression, hepatic IL-1B, TNF protein. (↓) proportions of TCA and TDCA in ileum. | [59] | |

| C57BL/6J female (7–8 weeks old) | 5% ethanol for 6 weeks in Lieber–DeCarli liquid diet | (↑) liver mRNA expression level of TNF-α, IL-6, Cc2, Ccr5 liver protein level of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, CD14 serum protein level. | [60] | |

| Rats | Male Wistar rats | Non-stop ethanol supply for 3 weeks. Gut sterilization with polymyxin B and neomycin | (↓) Plasma endotoxin levels (80–90 pg/mL → <25 pg/mL), average hepatic pathological score in ethanol-fed and antibiotic-treated rats. Antibiotics prevented elevated aspartate aminotransferase levels and hepatic surface hypoxia. | [61] |

| Mice | Alcohol-fed NS5ATg mice | Lieber–DeCarli diet containing 3.5% ethanol or isocaloric dextrin for long-term alcohol feeding, repetitive LPS injection | (↑) Ethanol-induced endotoxemia, liver injury, and tumorigenesis after Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 induction through hepatocyte-specific transgenic expression of the HCV non-structural protein NS5A. | [62] |

| Mice | 60 male Kunming mice (18–22 g) (6–8 weeks old) | alcohol gavage for 2–13 days | (↑) AST, ALT, TG, Hepatic MDA, ADH, mRNA, and protein expression of Cyp2e1, CAT. (↓)Major endogenous antioxidant enzymes (SOD and GSH-Px) mRNA expression of Nrf2, NQO-1, ADH. | [63] |

| Rats | Male Wistar rats (170–180 g) | chronic ethanol feeding | (↑) ROS production by LPS in Kupffer cells isolated from ethanol-fed mice. ROS production in Kupffer cells by LPS stimulation were increased NADPH oxidase dependently. ERK1/2 contributed to the increase in TNF-α production in Kupffer cells by LPS stimulation. | [64] |

| Mice | C57BL/6 male | EtOH-containing diets (35% of total calories, AF) ad libitum for 4 weeks | (↑) Saturated fatty acid levels. PLS-DA performed for liver and fecal samples. Mouse liver damage can be improved. (↑) intestinal; (↓) hepatic fatty acids; (↑) amino acid concentration. | [65] |

| Mice | C57BL/6 male (5–6 weeks old) | EtOH-containing Lieber– DeCarli liquid diet or an isocaloric control diet | (↑) ALT and AST. PCA, OPLS-DA, volcano maps, and correlation coefficient analyzed. | [66] |

| Mice | C57BL/6 male (8 weeks old) | Intermittent hypoxia exposure | PCA, OPLS-DA, and volcano maps, heatmaps analyzed. (↑) N1-(5-Phospho-D-ribosyl)-AMP, stearidonic acid, adenine, arachidonic acid (peroxide-free), ergothioneine, betaine, cyclohexylamine, GSH, GSH disulfide. | [67] |

| Mice | Kunming mice (7 weeks old) | 10% lard, 20% sucrose, 2.5% cholesterol, and 0.5% sodium cholate | (↑) Taurochenodeoxycholic acid, taurine, chenodeoxycholic acid, (4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z,19Z)-4,7,10,13,16, 19-docosahexaenoic acid, oleic acid, alpha-linolenic acid. Enrichment analysis. | [68] |

| Rats | Male Sprague Dawley rats (1 year old, 180–200g) | CCl4 (1mL/kg 40% CCl4, diluted in olive oil); twice a week for eight weeks | H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining, PLS-DA, heatmap, ROC curve analysis. (↑) L-tryptophan, L-valine, cholesterol, glycocholate, methylmalonic acid. | [69] |

| Mice | BALB/c mice (8 weeks old) | E. granulosus infection | 25mg of hepatic and fecal samples were analyzed. PCA, OPLS-DA, and volcano maps, heatmaps analyzed. (↑) 2-ethyl-2-hydroxybutyric acid, 2-hydroxyvaleric acid, cytidine 2’,3’-cyclic phosphate, sodium citrate, carboxytolbutamide, methylselenopyruvate. (↓) Pyronaridine, Bis(4-nitrophenyl) phosphate, Inosinic acid, 5-Phosphoribosyl-4-carboxy-5- aminoimidazole, tolclofos-methy, maduropeptin chromophore. | [70] |

| Mice | Fat-1 transgenic mice (10–12 weeks old) | EtOH diet | (↑) neutrophil accumulation, Pai-1 expression in wild-type mice. (↓) neutrophil accumulation, pai-1 expression, KC M1 abundance in fat-1 mice. Flow cytometry analysis of hepatic immune cells. | [71] |

| Animals | Exposures | Main results | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 14 alcoholic patients | chronic alcohol intake | (↑) Plasma endotoxin levels and serum IL-6 and IL-8 levels of patients compared to healthy subjects. Serum LBP was positively correlated with white blood cell and neutrophil counts as an indicator of an inflammatory response. | [152] |

| recombinant HepG2 ADH1/CYP2E1 cells | 100 mM ethanol for 6, 24, 48, 72, 96, and 110 h | (↓) CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2E1, and CYP3A4 expression. (↓) AGO1 knockdown, HNF4A RNA levels. | [153] | |

| severe AH (n = 161), and HC (n = 28) | chronic alcohol intake | (↑) level of sST2 was increased in SAH, higher levels of 3-HM in patients compared with controls, expression at baseline of GRK2 in circulating PMNs. (↓) expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 on the surface of circulating PMNs. | [154] | |

| Human | 51 alcoholic patients | consumed excessive alcohol, tobacco smoking | (↑) CYP2E1 activity, oxidative stress. (↑) chlorzoxazone oxidation. | [109] |

| 10 liver samples of AC | chronic alcohol intake | (↑) increased CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL8, CCL5 mRNA expression in AC liver, increased MØ infiltration. | [60] | |

| healthy control (n = 33), alcoholic liver cirrhosis (n = 23) | chronic alcohol intake | (↑) tumor volume and tumor maximum diameter expression of BCL-xl, CCL2, IL-4, IL-10, TIMP1, col1a1, and PCNA the frequency and number of macrophages in the liver hepatic CD206 expression. M2-associated protumor genes in the liver. | [151] | |

| Human | 53 cirrhosis cohort patients | alcohol intake, 1 yr follow-up, underwent liver transplantation | Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth was seen in 59% of patients with cirrhosis and was significantly related to systemic endotoxemia. | [155] |

| AH patients (n = 6); HC persons (n = 6) | Ethanol consumption of at least 80 g/day | (↑) NF-kB activity in the monocytes of six patients with AH as compared with normal subjects. (↑) NF-kB activity, TNF-α RNA expression, and TNF-α release by endotoxin in AH patients. | [156] | |

| Human | HCC, Late intrahepatic recurrence (n = 18); Early intrahepatic recurrence (n = 22) | HCC patients | (↓) Plasma specimens, tryptophan, cholesterol glucuronide, LysoPC (20:5), LysoPC (22:6). ROC curves based on methionine, GCDCA, and cholesterol sulfate was selected. AUC equal to 0.95. | [157] |

| Human | 46 patients | HCV-related HCC patients | PCA and PLS-DA score-plot has found. ROC curve analyzed for N-acetyl-lysine, L-glutamine, L-aspartate, and L-proline. Heatmap presenting the hierarchical clustering analysis. | [158] |

| Human | 248 serum samples | AHB, CHB, CHC with many types of liver disease | Heatmap analysis, γ-glutamyl peptides mechanism, GSH oxidation and reduction. (↓) GSH level. | [159] |

| Human | 52 serum samples | HCV, HCC patients | Serum sample analysis, 73 metabolites detected, Sensitivity of 97%, specificity of 95%, and an AUROC of 0.98 found. Sixteen metabolites were significantly altered. | [159] |

| Human | 559 patients | NAFLD patients | AUROC of 0.92, sensitivity of 73%, and specificity of 94%. | [160] |

| Human | 117 patients | HCV (n = 67), HBV (n = 50 patients) | OPLS-DA analysis, metabolites and their pathway analysis, Fold-change analysis. | [161] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hyun, J.Y.; Kim, S.K.; Yoon, S.J.; Lee, S.B.; Jeong, J.-J.; Gupta, H.; Sharma, S.P.; Oh, K.K.; Won, S.-M.; Kwon, G.H.; et al. Microbiome-Based Metabolic Therapeutic Approaches in Alcoholic Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158749

Hyun JY, Kim SK, Yoon SJ, Lee SB, Jeong J-J, Gupta H, Sharma SP, Oh KK, Won S-M, Kwon GH, et al. Microbiome-Based Metabolic Therapeutic Approaches in Alcoholic Liver Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(15):8749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158749

Chicago/Turabian StyleHyun, Ji Ye, Seul Ki Kim, Sang Jun Yoon, Su Been Lee, Jin-Ju Jeong, Haripriya Gupta, Satya Priya Sharma, Ki Kwong Oh, Sung-Min Won, Goo Hyun Kwon, and et al. 2022. "Microbiome-Based Metabolic Therapeutic Approaches in Alcoholic Liver Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 15: 8749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158749

APA StyleHyun, J. Y., Kim, S. K., Yoon, S. J., Lee, S. B., Jeong, J.-J., Gupta, H., Sharma, S. P., Oh, K. K., Won, S.-M., Kwon, G. H., Cha, M. G., Kim, D. J., Ganesan, R., & Suk, K. T. (2022). Microbiome-Based Metabolic Therapeutic Approaches in Alcoholic Liver Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(15), 8749. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158749