Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), the most lethal form of interstitial pneumonia of unknown cause, is associated with a specific radiological and histopathological pattern (the so-called “usual interstitial pneumonia” pattern) and has a median survival estimated to be between 3 and 5 years after diagnosis. However, evidence shows that IPF has different clinical phenotypes, which are characterized by a variable disease course over time. At present, the natural history of IPF is unpredictable for individual patients, although some genetic factors and circulating biomarkers have been associated with different prognoses. Since in its early stages, IPF may be asymptomatic, leading to a delayed diagnosis. Two drugs, pirfenidone and nintedanib, have been shown to modify the disease course by slowing down the decline in lung function. It is also known that 5–10% of the IPF patients may be affected by episodes of acute and often fatal decline. The acute worsening of disease is sometimes attributed to identifiable conditions, such as pneumonia or heart failure; but many of these events occur without an identifiable cause. These idiopathic acute worsenings are termed acute exacerbations of IPF. To date, clinical biomarkers, diagnostic, prognostic, and theranostic, are not well characterized. However, they could become useful tools helping facilitate diagnoses, monitoring disease progression and treatment efficacy. The aim of this review is to cover molecular mechanisms underlying IPF and research into new clinical biomarkers, to be utilized in diagnosis and prognosis, even in patients treated with antifibrotic drugs.

1. Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive lung disease [1]. The epidemiology of this disease is not uniform due to data collection methods and classification terms variability among different studies. However, throughout Europe and North America, an incidence between 2.8 and 19 cases per 100,000 people per year has been reported [2,3,4]. IPF primary affects men, older than 50 years (median age at diagnosis is about 65 years) [5,6,7]. The disease course is variable, due to different clinical phenotypes [8,9]. However, the median survival time from diagnosis is 2–4 years [10]. Since in its early stages, IPF may be asymptomatic, leading to a delayed diagnosis. When present, the most frequent symptoms are progressive dyspnoea and cough. The IPF diagnosis is based on the identification of the usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern, both on histological samples or radiological images, and the exclusion of other known causes of pulmonary fibrosis. Frequently the diagnosis is complex, requiring a multidisciplinary evaluation as recommended by international guidelines [11,12]. At present, two drugs, nintedanib and pirfenidone, which slow the progression of the disease and improve prognosis, are approved for the treatment of IPF [12].

The management of IPF is currently based on clinical data, such as symptoms, lung function tests, and radio-histological patterns, due to a lack of reliable molecular markers. However, the identification of clinical biomarkers, diagnostic, prognostic, and theranostic would allow an evaluation based on underlying pathobiological mechanism of disease, leading to adequate phenotyping of patients in terms of diagnosis, prognosis, and response to therapy. This review aims to cover molecular mechanisms underlying IPF and research into new clinical biomarkers, to be utilized in diagnosis and prognosis, even in patients treated with antifibrotic drugs.

2. Definition of a Biomarker

Biomarkers are defined as “characteristics that are objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” [13]. At any time during the evaluation of patients affected by a disease, biomarkers can be considered useful tools. Predisposition biomarkers could identify people at risk for eventually develop a disease, diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers integrate the diagnostic process and theranostic biomarkers are a reliable measure of efficacy and safety during treatment. Moreover, biomarkers are frequently used as a surrogate endpoint in clinical trials helping predict clinical benefit based on epidemiologic, therapeutic, pathophysiologic, or other scientific evidence [13]. Currently, 2018 American Thoracic Society (ATS), European Respiratory Society (ERS), Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS), American Latin Thoracic Association (ALAT) strongly recommends not to measure any serum biomarker for the purpose of distinguishing IPF from other interstitial lung diseases (ILD) in patients with newly detected ILD of apparently unknown cause who are clinically suspected of having IPF. Moreover, no guidelines or official statement on prognostic and theranostic biomarkers are available.

A good-quality biomarker should be reproducible, very sensitive, specific, and accurate. It should be validated in large multicentric trials and heterogeneous populations. Moreover, to be used on a large scale, it should be easily available and accessible. Biomarkers detectable on peripheral blood, exhaled breath condensate or broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) offer an increased range of applications compared with a transbronchial or surgical lung biopsy. Finally, the cost-effectiveness ratio should be acceptable [14].

3. Molecular Biomarkers in IPF

The development of new molecular biomarkers for IPF is based on two different approaches. The hypothesis-driven method selects new candidate biomarkers a priori based on previous evidence about the disease. In contrast, the unbiased approach utilizes methods from systems biology to screen a large number of candidate biomarkers for their association with the disease. Although the former has the advantage of a strong rationale but lacks efficiency, the latter is more efficient but also burdened by the risk of false discovery [14].

Historically, IPF was considered a chronic inflammatory disorder, gradually leading to fibrosis. However, anti-inflammatory, and immunosuppressive therapy have shown to be ineffective and associated with increased mortality [15]. Up to date, IPF is described as characterized by the interaction of multiple genetic and environmental risk factors, with local micro-injuries to ageing alveolar epithelium. As a consequence, different process such as aberrant epithelial–fibroblast communication, the induction of myofibroblasts and the accumulation of extracellular matrix, lead to remodeling of lung interstitium [16]. Consequently, the most promising biomarkers in IPF are related to alveolar epithelial cell dysfunction, immune dysregulation, fibroproliferation, fibrogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling [14].

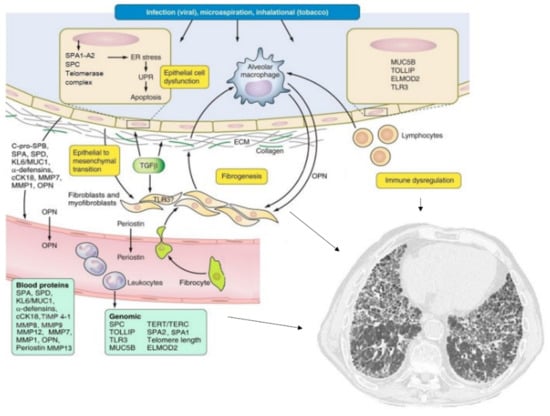

The main biomarkers analyzed in this review and their possible applications are resumed in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Molecular biomarkers in IPF.

Figure 1.

Pathogenesis and molecular biomarkers of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Various mechanisms (most of them indicated by the arrows) leads to pulmonary fibrosis (see text for details). Adapted from Ley B, et al. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2014, 307, L681–L691 [14].

4. Predisposition Biomarkers

Mechanism or biological pathways linked to disease predisposition are reflected by predisposition biomarkers. They should provide information through inexpensive and non-invasive sampling with high sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value. Using predisposition biomarker, a patient could be address to informative counselling, preventive measures, and early therapy [14].

Surfactant proteins are secreted in surfactant by type II alveolar epithelial cells (AEC). They are encoded by SFTPA, SFTPB, SFTPC, and SFTPD genes [17]. Among surfactant proteins variants of surfactant protein C (SP-C) [18,19,20,21], surfactant protein A2 (SP-A2) [22,23,24,25] and surfactant protein A1 (SP-A1) [26] have been associated to familiar pulmonary fibrosis, while they are rare in sporadic IPF [19]. As surfactant protein levels can be measured in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and in blood, they could have a role in identifying at risk individuals in families with pulmonary fibrosis.

A common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the putative promoter region of the mucin 5B (MUC5B) gene (rs35705950), which encoded a glycosylated macromolecular component of mucus, has been associated with familiar pulmonary fibrosis and sporadic pulmonary fibrosis [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. A recent meta-analysis confirmed that the minor T allele is significantly associated with an increased risk of IPF compared with the G allele in an allele dose-dependent manner [35]. However, MUC5B (rs35705950) has been found in 9% of people with interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA), a prevalence way higher than the rate reported for IPF [36]. Although MUC5B promoter polymorphism is a promising predisposition biomarker, it is neither necessary nor sufficient to cause the disease and understanding its role in IPF pathogenesis together with other genetic or environmental factors remain an unmet need.

The telomerase complex is involved in protection of chromosomes from loss of material, catalyzing the addition of repeated DNA sequences in the telomere region [37]. Several proteins contribute to the correct activity of the telomerase complex, including telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), dyskerin, telomere binding protein (TIN2), interaction with the telomerase repeat binding factor (TERF1), and the telomerase RNA component (TERC). Moreover, several other proteins contribute to the regulation of telomerase complex [37]. Several variants of the telomerase complex and its regulatory proteins have been associated to pulmonary fibrosis, especially familiar forms [38]. Although the telomerase complex can be evaluated on blood cells (granulocytes or monocytes), and common in IPF patients compared with age matched controls [39], it is globally rare in sporadic IPF and not specific since it has been associated with risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) too [40].

Although the relationship between IPF and immunity is controversial, several components of the immune system have been evaluated as predisposition biomarkers in IPF. Toll-like receptors (TLR), fundamental components of innate immunity, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of IPF. TLR-2 mRNA is overexpressed in IPF patients and has shown pro-fibrotic features in mice. TLR-3 has shown antifibrotic features both in human and mice through downregulation of transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1) and upregulation of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). The loss-of-function variants (L412F) of TLR-3 lead to enhanced fibrotic responses. Some evidence, mainly in animal models, has been shown also for TLR2/4, TLR9, and TLR4 [41,42,43,44]. Another candidate gene for IPF is ELMOD-2, expressed in alveolar macrophages and type II AECs. A genome wide scan in 6 families with familiar pulmonary fibrosis in Finland showed reduced levels of mRNA expression of ELMOD-2 in IPF patients compared with healthy controls [45].

Predisposition biomarkers help understanding the pathogenesis of IPF and predicting the predisposition and prognosis of the disease. However, to date, none of these biomarkers is completely specific and sensitive for the diagnosis of sporadic pulmonary fibrosis, nor validated in clinical use. In familiar cases of pulmonary fibrosis, a consult with a geneticist and a screening for the most common biomarkers should be proposed to patients.

5. Diagnostic Biomarkers

Diagnostic biomarkers should reflect the mechanism or biological pathways that distinct IPF from the other ILDs. They should be easy to evaluate and reproducible, such as blood, urine, BALF derived or imaging-based biomarkers. Ideally, they should improve diagnosis, reduce the risk of diagnostic tests, reduce the number of unclassifiable cases, helping discriminate IPF from other ILDs accurately [14]. Several blood proteins have shown some evidence in terms of diagnostic process, however, the use of none of them is recommended by guidelines for the diagnosis of IPF [11].

The detection of surfactant proteins in serum of patients with pulmonary diseases reflects an injury of the alveolar epithelial barrier. SP-A and D have been studied as diagnostic markers in IPF. Although BALF levels of surfactant proteins are reduced both in IPF and other ILDs compared with healthy controls [46,47], serum levels appear to be increased [47,48,49]. Wang et al. conduced a meta-analysis to evaluate the use of SP-A and SP-D for differential diagnosis of IPF. SP-A serum levels appear to be significantly higher in patients with IPF than in patients with non-IPF ILDs, pulmonary infection, and healthy controls, while no differences are found in SP-D serum levels in IPF versus non-IPF ILD patients, although higher than those in pulmonary infection and healthy controls [50]. Recently, SP-B precursor, C-pro-SP-B, has been studied as a new biomarker in serum of patients with different chronic lung diseases including ILDs. The highest serum levels of C-pro-SP-B were detected in the serum of IPF patients being able to differentiate IPF patients from patients with all other pulmonary diseases [51]. Moreover, SP-D levels were significantly elevated in acute exacerbation of IPF compared with stable IPF [52].

Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL6)/mucin 1 (MUC1) is a glycoprotein expressed on the extracellular surface of type II AECs and bronchiolar epithelial cells in the lung largely studied in ILDs due to its overexpression in affected lung and regenerating type II AECs [53,54]. KL-6 is increased in serum of several ILDs including IPF [47,49,53,55,56,57] In one study, KL-6 levels in BALF seems to be a specific diagnostic marker in IPF compared with other ILDs [58] while Bennet et al. proved that higher levels of BALF KL-6 are related to a more severe and extended disease [56]. However, since KL-6 reflects AECs damage, it is not specific enough to distinguish IPF from the other ILDs nor alone neither as a part of composite index. However, it could facilitate stratification of severity [55,56,57].

Circulating caspase-cleaved cytokeratin-18 (cCK-18) is the cleaved fragment of cytokeratin-18 (CK-18), a cytoskeletal protein found in AECs. Since cCK-18 is produced during apoptosis in response to stress, it has been evaluated as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in one study: cCK18 was significantly elevated in the serum of IPF patients compared with normal controls and patients with other ILDs although it was not associated with prognosis [59].

TLRs have been studied widely for their implication in IPF pathogenesis and predisposition. However, some evidence has highlighted a possible role in diagnosis. Higher levels of TLR in BALF of IPF patients, particularly TRL-7 has been noted. In the same study, TLR also showed different profiles of expression in fibrotic and granulomatous disorders [60].

Metalloproteases (MMP) are another class of proteins widely studied for their role in in the aberrant fibrotic process, but the mechanisms are not completely understood and characterized as it seems they are implied both in deleterious and beneficial effects on the fibrotic process [61] They are a family of zinc-dependent matrixins that participate in extracellular matrix degradation but also in processing and cleaving of different bioactive mediators [62]. In particular, MMP-1 is upregulated in IPF patients compared with controls, and higher levels of MMP-1 has been shown in BALF and in plasma of IPF patients [63,64]. MMP-7 is also upregulated in IPF, with higher serum and BALF levels in patients compared with healthy controls [14,65]. Recently, Bauer et al. analyzed samples from the Bosentan Use in Interstitial Lung Disease (BUILD)-3 trial dosing MMP-7 among other biomarkers. MP-7 protein levels were elevated in IPF patients compared with healthy controls, and MMP-7 levels also increased over time [66]. Although MMP-7 alone is not sufficiently specific to distinguish IPF from other ILDs, if evaluated with other markers of fibrosis it could help differentiate IPF from other ILDs with good accuracy [64,67].

Osteopontin (OPN) is a phosphorylated glycoprotein that work as a mediator of inflammation and wound healing [68]. OPN is overexpressed in IPF lung [68,69] and seems its profibrotic role seems to be related to its ability to enhance fibroblasts migration by cooperating with chemoattractant interleukin 6 (IL-6) [69]. Moreover, OPN also induces upregulation of MMP-7 [70]. Although OPN is increased in serum and BALF of IPF patients [71,72], it is not specific in differentiating IPF from other ILDs [72]. However, as part of a composite index it helps improving diagnostic confidence [67].

6. Prognostic Biomarkers

Prognostic biomarkers should contribute to quantitative assessment of mechanism or biological pathways relevant to disease progression. They should be repeatable over time without significant risk for patients, such as blood and urine-based biomarkers. Moreover, they should have a low intra-patient, inter-test variability with calibration and discrimination values clearly established. They could be integrated in multiparametric models in order to improve prognostic counselling [14]. Potentially useful prognostic biomarkers have been identified both in genomic variants and blood proteins. With regard for genomic variants mutation in the telomerase complex and MUC5B have been studied as possible prognostic biomarkers. Telomere length has been associated to a worse survival [73] and transplant free survival [74] in IPF patients. Although MUC5B promoter variant (rs35705950) has been associated to an increased risk of developing pulmonary fibrosis, its role in predicting survival is contradictory [75,76,77,78]. Serum levels of SP-A and SP-D have been associated with reduced survival in IPF [46,48,79,80,81]. The variant in the TOLLIP gene, encoding for an adapter protein, is associated with a worse survival and more rapid disease progression possibly helping stratification at baseline of IPF patients [78].

Several studies highlighted a relationship between elevated values of KL-6 and mortality or progression in IPF [57,82,83,84,85] although these data have not been confirmed in other studies [86,87]. On the other hand, serial measurements of serum KL-6 concentrations resulted a risk factor for progressive disease and worse prognosis [57,88]. With regard for AE of IPF, serum values of KL-6 resulted higher compared with stable patients and higher values are predictor of onset of AE [52,89,90]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that increased values of KL-6 in IPF is a predictor of AE risk, while it seems not to be related with mortality [87].

With regard for immune mediators, the SNP in theTLR3 (L412F) has been associated to increased mortality and accelerated progression in independent cohort [91,92]. Alpha-defensins, small antimicrobial proteins secreted by neutrophils and epithelial cells, has been proposed as a biomarker of AE of IPF. In fact, although alpha-defensins are upregulated in IPF lung, higher levels are detectable in patients with AE of IPF. Moreover, alpha-defensin serum levels were increased in AE IPF compared with stable IPF suggesting their use as biomarkers for AEs [63].

MMPs, in particular MMP-7, have been studied not only as diagnostic biomarkers but they can be useful tools in predicting prognosis and transplant free survival in IPF patients [14,66]. MMP-7 has also been evaluated in several studies in association with other markers of IPF for its diagnostic and prognostic qualities with positive results [67,86,93]. MMP-7 is not the only MMPs that has shown promising results as a diagnostic biomarker. Recently, Todd et al. evaluated the circulating serum levels of MMPs (MMPs 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 12, and 13) and tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMP) (TIMPs 1, 2, and 4) in a cohort of 300 IPF patients from the IPF-PRO Registry, highlighting that MMPs and TIMPs analyzed were all present at higher levels in patients with IPF compared with controls except for TIMP2. MMP8, MMP9, and TIMP1 were the best diagnostic markers for distinguishing patients with IPF from controls. Moreover, MMP7, MMP12, MMP13, and TIMP4 were able to stratify patients for disease severity [94].

The evidence on the prognostic value of OPN is scarce [72,95]. However, interestingly, a recent study showed that OPN serum levels where significantly higher in patients with AE of IPF compared with stable IPF or healthy controls. Moreover, higher levels of OPN were associated to increased mortality in AEs [96]. Periostin, another ECM protein involved in tissue development and wound healing, has been shown part of the pathogenetic process in IPF. Periostin has prognostic values, in fact total periostin can predict both short-term declines of pulmonary function and overall survival in IPF patients. However, total periostin is not specific for IPF. On the contrary, the monomeric periostin form is more specific and can be used not only to predict pulmonary function decline but also to distinguish IPF patients from healthy controls [97].

7. Therapeutic Biomarkers

Therapeutic biomarkers should provide quantitative assessment or indicate the presence or absence of mechanisms or biological pathways targeted by therapy. Since these biomarkers work as surrogate endpoints, they should be measurable over time with low risks for patients, low intra-patient, inter-test variability, and should improve clinical decision making of therapeutic intervention. Finally, when a therapeutic biomarker is evaluated threshold for change should be established reflecting meaningful therapeutic response [14].

Since many biomarkers have been studied before the introduction of antifibrotic therapy, evidence on their usefulness in monitoring response to therapy is more limited.

Surfactant proteins serum levels have shown potential efficacy as outcomes in IPF therapy. SP-A levels in IPF patients treated with pirfenidone or nintedanib from baseline to 3 and 6 months were found to predict progression [98], while SP-D levels in IPF patients treated with IPF predict disease progression and prognosis [99,100].

Promising data have been shown in several studies on KL-6 and its use in the monitoring of antifibrotic therapy. Response to pirfenidone therapy correlates with changes in serum KL-6 over time in one study [101] Bergantini et al. evaluated serial measurements of serum KL-6 in IPF patients treated with nintedanib, and demonstrated an indirect correlation with forced vital capacity (FVC) percentages and KL-6 values. Moreover, after 1 year of treatment, patients on therapy showed stable FVC percentages and KL-6 levels compared with baseline values [102]. Nakamura et al. did not find any difference in KL-6 serum values in severe IPF patients treated with nintedanib compared with non-severe patients [103].

MMP-7 has recently been studied in with other biomarkers of transplant free survival in a study on 325 patients, 68 of them treated with antifibrotic therapy, to evaluate the role of such biomarkers in patients on antifibrotic therapy. The study revealed that these biomarkers predict differential transplant free survival in patients on antifibrotic therapy but at higher thresholds than in non-treated patients. Moreover, plasma biomarker level generally increases over time in non-treated patients but remain unchanged in patients on antifibrotics [104].

8. Conclusions

The need of reliable biomarkers is becoming more and more fundamental. The validation of useful and accurate diagnostic markers could reduce uncertainty and the use of invasive procedure. Prognostic and therapeutic markers could help stratify patients based on severity and disease behavior in order to personalize management. Moreover, reliable markers able to predict AEs could implement prevention measures and modify the prognosis of such events, which, to date, is poor. Several molecules have shown potential value as biomarkers in IPF. However, many of them have been evaluated mainly in Asiatic cohorts of patients, where their use is more common. Their accuracy should be confirmed also in Caucasian cohorts in order to routinely apply them in the management of IPF. The use of biomarker index composed by multiple biomarkers already studied separately, with the aim of improve diagnostic accuracy in distinguish IPF from other ILDs or healthy controls is promising, but, for now, has shown controversial results.

Finally, none of these biomarkers have been validated in large clinical trials, which still remain an unmet need. However, as a remark of the importance of biomarkers in IPF, many clinical trials evaluating as primary or secondary outcomes known and new biomarkers, have been conducted (Table 2 and Table 3) or are still ongoing (Table 3 and Table 4).

Table 2.

Clinical trials on predisposition, diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in IPF.

Table 3.

Therapeutic biomarkers in IPF.

Table 4.

Ongoing clinical studies on biomarkers in IPF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., A.M. and F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S., P.F., S.B. and M.D.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.C., A.M. and F.L.; supervision, F.L. and A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge that this research was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR)—Department of Excellence project PREMIA (PREcision MedIcine Approach: bringing biomarker research to clinic).

Conflicts of Interest

P.F., F.L. and A.P. report personal fees from Roche and Boehringer-Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. All the other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

| IPF | idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| UIP | usual interstitial pneumonia |

| ATS | American Thoracic Society |

| ERS | European Respiratory Society |

| JRS | Japanese Respiratory Society |

| ALAT | American Latin Thoracic Association |

| ILD | interstitial lung disease |

| BAL | broncho-alveolar lavage |

| AECs | alveolar epithelial cells |

| SP-C | surfactant protein C |

| SP-A2 | surfactant protein A2 |

| SP-A1 | surfactant protein A1 |

| BALF | bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| SNP | single nucleotide polymorphism |

| MUC5B | mucin 5 B |

| ILA | interstitial lung abnormalities |

| TERT | telomerase reverse transcriptase |

| TIN2 | telomere binding protein 2 |

| TERF1 | telomerase repeat binding factor 1 |

| TERC | telomerase RNA component |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors |

| TGFB1 | transforming growth factor beta 1 |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| KL-6 | Krebs von den Lungen-6 |

| MUC | 1 mucin 1 |

| cCK-18 | circulating caspase-cleaved cytokeratin-18 |

| CK-18 | cytokeratin-18 |

| MMPs | metalloproteases |

| BUILD | Bosentan Use in Interstitial Lung Disease |

| OPN | osteopontin |

| IL-6 | interleukin 6 |

| TIMPs | tissue inhibitors of MMPs |

| FVC | forced vital capacity |

References

- Luppi, F.; Spagnolo, P.; Cerri, S.; Richeldi, L. The big clinical trials in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2012, 18, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.P.; Fogarty, A.W.; Hubbard, R.B.; McKeever, T. Global incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 46, 795–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchemann, B.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; De Naurois, C.J.; Sanyal, S.; Brillet, P.-Y.; Brauner, M.; Kambouchner, M.; Huynh, S.; Naccache, J.M.; Borie, R.; et al. Prevalence and incidence of interstitial lung diseases in a multi-ethnic county of Greater Paris. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richeldi, L.; Rubin, A.S.; Avdeev, S.; Udwadia, Z.F.; Xu, Z.J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in BRIC countries: The cases of Brazil, Russia, India, and China. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Collard, H.R.; Egan, J.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Behr, J.; Brown, K.K.; Colby, T.V.; Cordier, J.-F.; Flaherty, K.R.; Lasky, J.A.; et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 788–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Thoracic Society. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Diagnosis and treatment. International consensus statement. American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 161, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Weycker, D.; Edelsberg, J.; Bradford, W.Z.; Oster, G. Incidence and Prevalence of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 174, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buendía-Roldán, I.; Mejía, M.; Navarro, C.; Selman, M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Clinical behavior and aging associated comorbidities. Respir. Med. 2017, 129, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fell, C.D. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Phenotypes and Comorbidities. Clin. Chest Med. 2012, 33, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, B.; Collard, H.R.; King, T.E. Clinical Course and Prediction of Survival in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Morell, F.; et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, e44–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Rochwerg, B.; Zhang, Y.; Cuello-Garcia, C.; Azuma, A.; Behr, J.; Brozek, J.L.; Collard, H.R.; Cunningham, W.; Homma, S.; et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Update of the 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, e3–e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biomarkers Definitions Working Group. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints: Preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001, 69, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, B.; Brown, K.K.; Collard, H.R. Molecular biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2014, 307, L681–L691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luppi, F.; Cerri, S.; Beghè, B.; Fabbri, L.; Richeldi, L. Corticosteroid and immunomodulatory agents in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Med. 2004, 98, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richeldi, L.; Collard, H.R.; Jones, M.G. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2017, 13, 1941–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitsett, J.A.; Wert, S.E.; Weaver, T.E. Alveolar Surfactant Homeostasis and the Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 2010, 61, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Moorsel, C.H.M.; van Oosterhout, M.F.M.; Barlo, N.P.; de Jong, P.A.; van der Vis, J.J.; Ruven, H.J.T.; van Es, H.W.; van den Bosch, J.M.M.; Grutters, J. Surfactant protein C mutations are the basis of a significant portion of adult familial pulmonary fibrosis in a dutch cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 1419–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, W.E.; Grant, S.W.; Ambrosini, V.; Womble, K.E.; Dawson, E.P.; Lane, K.B.; Markin, C.; Renzoni, E.; Lympany, P.; Thomas, A.Q.; et al. Genetic mutations in surfactant protein C are a rare cause of sporadic cases of IPF. Thorax 2004, 59, 977–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogee, L.M.; Dunbar, A.E.; Wert, S.E.; Askin, F.; Hamvas, A.; Whitsett, J.A. A Mutation in the Surfactant Protein C Gene Associated with Familial Interstitial Lung Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thouvenin, G.; Taam, R.A.; Flamein, F.; Guillot, L.; Le Bourgeois, M.; Reix, P.; Fayon, M.; Counil, F.; Depontbriand, U.; Feldmann, D.; et al. Characteristics of disorders associated with genetic mutations of surfactant protein C. Arch. Dis. Child. 2010, 95, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Moorsel, C.H.M.; Ten Klooster, L.; van Oosterhout, M.F.M.; de Jong, P.A.; Adams, H.; Wouter van Es, H.; Ruven, H.J.T.; van der Vis, J.J.; Grutters, J. SFTPA2 Mutations in Familial and Sporadic Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1249–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Kuan, P.J.; Xing, C.; Cronkhite, J.T.; Torres, F.; Rosenblatt, R.L.; DiMaio, J.M.; Kinch, L.N.; Grishin, N.V.; Garcia, C.K. Genetic Defects in Surfactant Protein A2 Are Associated with Pulmonary Fibrosis and Lung Cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 84, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitra, M.; Wang, Y.; Gerard, R.D.; Mendelson, C.R.; Garcia, C.K. Surfactant Protein A2 Mutations Associated with Pulmonary Fibrosis Lead to Protein Instability and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 22103–22113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Qin, J.; Guo, T.; Chen, P.; Ouyang, R.; Peng, H.; Luo, H. Identification and functional characterization of a novel surfactant protein A2 mutation (p.N207Y) in a Chinese family with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2020, 8, e1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, N.; Giraud, V.; Picard, C.; Nunes, H.; Dastot-Le Moal, F.; Copin, B.; Galeron, L.; de Ligniville, A.; Kuziner, N.; Reynaud-Gaubert, M. Germline SFTPA1 mutation in familial idiopathic interstitial pneumonia and lung cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 1457–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibold, M.A.; Wise, A.L.; Speer, M.C.; Steele, M.P.; Brown, K.K.; Loyd, J.E.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Zhang, W.; Gudmundsson, G.; Groshong, S.D.; et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borie, R.; Crestani, B.; Dieude, P.; Nunes, H.; Allanore, Y.; Kannengiesser, C.; Airo, P.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Wallaert, B.; Israel-Biet, D.; et al. The MUC5B Variant Is Associated with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis but Not with Systemic Sclerosis Interstitial Lung Disease in the European Caucasian Population. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Noth, I.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Kaminski, N. A variant in the promoter of MUC5B and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1576–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, C.J.; Sato, H.; Fonseca, C.; Banya, W.A.S.; Molyneaux, P.L.; Adamali, H.; Russell, A.-M.; Denton, C.P.; Abraham, D.J.; Hansell, D.M.; et al. Mucin 5B promoter polymorphism is associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but not with development of lung fibrosis in systemic sclerosis or sarcoidosis. Thorax 2013, 68, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noth, I.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, S.-F.; Flores, C.; Barber, M.; Huang, Y.; Broderick, S.M.; Wade, M.S.; Hysi, P.; Scuirba, J.; et al. Genetic variants associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis susceptibility and mortality: A genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2013, 1, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Li, C.; Zhang, M.; Jones-Hall, Y.L.; Myers, J.L.; Noth, I.; Liu, W. Association between MUC5B and TERT polymorphisms and different interstitial lung disease phenotypes. Transl. Res. 2014, 163, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horimasu, Y.; Ohshimo, S.; Bonella, F.; Tanaka, S.; Ishikawa, N.; Hattori, N.; Kohno, N.; Guzman, J.; Costabel, U. MUC5B promoter polymorphism in Japanese patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirol. Carlton. Vic. 2015, 20, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peljto, A.L.; Selman, M.; Kim, D.S.; Murphy, E.; Tucker, L.; Pardo, A.; Lee, J.S.; Ji, W.; Schwarz, M.I.; Yang, I.V.; et al. The MUC5B Promoter Polymorphism Is Associated With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in a Mexican Cohort but Is Rare Among Asian Ancestries. Chest 2015, 147, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Tang, S.; Min, H.; Yi, L.; Xu, B.; Song, Y. Association Between the MUC5B Promoter Polymorphism rs35705950 and Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Meta-analysis and Trial Sequential Analysis in Caucasian and Asian Populations. Medicine 2015, 94, e1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunninghake, G.M.; Hatabu, H.; Okajima, Y.; Gao, W.; Dupuis, J.; Latourelle, J.C.; Nishino, M.; Araki, T.; Zazueta, O.E.; Kurugol, S.; et al. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and interstitial lung abnormalities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 2192–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, R.T.; Young, N.S. Telomere diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 2353–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borie, R.; Kannengiesser, C.; Dupin, C.; Debray, M.-P.; Cazes, A.; Crestani, B. Impact of genetic factors on fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Incidence and clinical presentation in adults. Presse Méd. 2020, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, J.K.; Chen, J.J.-L.; Lancaster, L.; Danoff, S.; Su, S.-C.; Cogan, J.D.; Vulto, I.; Xie, M.; Qi, X.; Tuder, R.M.; et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13051–13056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rode, L.; Bojesen, S.E.; Weischer, M.; Vestbo, J.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Short telomere length, lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 46 396 individuals. Thorax 2012, 68, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karampitsakos, T.; Woolard, T.; Bouros, D.; Tzouvelekis, A. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 808, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, K.M.; Hernady, E.B.; Reed, C.K.; Johnston, C.J.; Groves, A.M.; Finkelstein, J.N. Apoptosis Resistance in Fibroblasts Precedes Progressive Scarring in Pulmonary Fibrosis and Is Partially Mediated by Toll-Like Receptor 4 Activation. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 170, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebener, S.; Barnowski, S.; Wotzkow, C.; Marti, T.M.; Lopez-Rodriguez, E.; Crestani, B.; Blank, F.; Schmid, R.A.; Geiser, T.; Funke, M. Toll-like receptor 4 activation attenuates profibrotic response in control lung fibroblasts but not in fibroblasts from patients with IPF. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2017, 312, L42–L55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, T.; Liu, N.; Chen, H.; Geng, Y.; Kurkciyan, A.; Mena, J.M.; Stripp, B.R.; Jiang, D.; et al. Hyaluronan and TLR4 promote surfactant-protein-C-positive alveolar progenitor cell renewal and prevent severe pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, U.; Pulkkinen, V.; Dixon, M.; Peyrard-Janvid, M.; Rehn, M.; Lahermo, P.; Ollikainen, V.; Salmenkivi, K.; Kinnula, V.; Kere, J.; et al. ELMOD2 Is a Candidate Gene for Familial Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 79, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlo, N.P.; Van Moorsel, C.H.M.; Ruven, H.J.T.; Zanen, P.; Bosch, J.M.M.V.D.; Grutters, J.C. Surfactant protein-D predicts survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffus. Lung Dis. 2009, 26, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, H.; Mukae, H.; Kadota, J.; Kaida, H.; Nagata, T.; Abe, K.; Matsukura, S.; Kohno, S. High serum concentrations of surfactant protein A in usual interstitial pneumonia compared with non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 2003, 58, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, K.; King, T.; Kuroki, Y.; Bucher-Bartelson, B.; Hunninghake, G.; Newman, L.; Nagae, H.; Mason, R. Serum surfactant proteins-A and -D as biomarkers in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2002, 19, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, H.; Yokoyama, A.; Kondo, K.; Hamada, H.; Abe, M.; Nishimura, K.; Hiwada, K.; Kohno, N. Comparative Study of KL-6, Surfactant Protein-A, Surfactant Protein-D, and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 as Serum Markers for Interstitial Lung Diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ju, Q.; Cao, J.; Tang, W.; Zhang, J. Impact of serum SP-A and SP-D levels on comparison and prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, e7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, N.; Rossler, A.; Hornemann, K.; Muley, T.; Grünig, E.; Schmidt, W.; Herth, F.J.F.; Kreuter, M. C-proSP-B: A Possible Biomarker for Pulmonary Diseases? Respir. Int. Rev. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 96, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, H.R.; Calfee, C.S.; Wolters, P.J.; Song, J.W.; Hong, S.-B.; Brady, S.; Ishizaka, A.; Jones, K.D.; King, T.E.; Matthay, M.A.; et al. Plasma biomarker profiles in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2010, 299, L3–L7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, N.; Hattori, N.; Yokoyama, A.; Kohno, N. Utility of KL-6/MUC1 in the clinical management of interstitial lung diseases. Respir. Investig. 2012, 50, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtsuki, Y.; Fujita, J.; Hachisuka, Y.; Uomoto, M.; Okada, Y.; Yoshinouchi, T.; Lee, G.-H.; Furihata, M.; Kohno, N. Immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic studies of the localization of KL-6 and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) in presumably normal pulmonary tissue and in interstitial pneumonia. Med. Mol. Morphol. 2007, 40, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, M.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, L.; Sun, B.; Wang, H. Evaluation of the Diagnostic Efficacies of Serological Markers Kl-6, SP-A, SP-D, CCL2, and CXCL13 in Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonia A67. Struct. Funct. Relat. 2020, 98, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, D.; Salvini, M.; Fui, A.; Cillis, G.; Cameli, P.; Mazzei, M.A.; Fossi, A.; Refini, R.M.; Rottoli, P. Calgranulin B and KL-6 in Bronchoalveolar Lavage of Patients with IPF and NSIP. Inflammation 2019, 42, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Luo, Q.; Han, Q.; Huang, J.; Ou, Y.; Chen, M.; Wen, Y.; Mosha, S.S.; Deng, K.; Chen, R. Sequential changes of serum KL-6 predict the progression of interstitial lung disease. J. Thorac. Dis. 2018, 10, 4705–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhao, Y.B.; Kong, L.F.; Li, Z.H.; Kang, J. The expression and clinical role of KL-6 in serum and BALF of patients with different diffuse interstitial lung diseases. Chin. J. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2016, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lee, J.S.; Kukreja, J.; Barry, S.S.; Jones, K.D.; Elicker, B.M.; Kim, D.S.; Papa, F.R.; Collard, H.R. Cleaved cytokeratin-18 is a mechanistically informative biomarker in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritopoulos, G.A.; Antoniou, K.M.; Karagiannis, K.; Samara, K.D.; Lasithiotaki, I.; Vassalou, E.; Lymbouridou, R.; Koutala, H.; Siafakas, N.M. Investigation of toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of fibrotic and granulomatous disorders: A bronchoalveolar lavage study. Fibrogenes. Tiss. Repair. 2010, 3, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalanobish, S.; Saha, S.; Dutta, S.; Sil, P.C. Matrix metalloproteinase: An upcoming therapeutic approach for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, A.; Selman, M. Role of matrix metaloproteases in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Fibrogenes. Tiss. Repair. 2012, 5, S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, K.; Gibson, K.F.; Lindell, K.O.; Richards, T.J.; Zhang, Y.; Dhir, R.; Bisceglia, M.; Gilbert, S.; Yousem, S.A.; Song, J.W.; et al. Gene Expression Profiles of Acute Exacerbations of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 180, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, A.; Beltrão, M.; Sokhatska, O.; Costa, D.; Melo, N.; Mota, P.; Marques, A.; Delgado, L. Serum metalloproteinases 1 and 7 in the diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and other interstitial pneumonias. Respir. Med. 2015, 109, 1063–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borensztajn, K.; Crestani, B.; Kolb, M. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: From Epithelial Injury to Biomarkers—Insights from the Bench Side. Respiration 2013, 86, 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Y.; White, E.S.; De Bernard, S.; Cornelisse, P.; Leconte, I.; Morganti, A.; Roux, S.; Nayler, O. MMP-7 is a predictive biomarker of disease progression in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. ERJ Open Res. 2017, 3, 74–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, E.S.; Xia, M.; Murray, S.; Dyal, R.; Flaherty, C.M.; Flaherty, K.R.; Moore, B.; Cheng, L.; Doyle, T.J.; Villalba, J.; et al. Plasma Surfactant Protein-D, Matrix Metalloproteinase-7, and Osteopontin Index Distinguishes Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis from Other Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 194, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denhardt, D.T.; Noda, M.; O’Regan, A.W.; Pavlin, D.; Berman, J.S. Osteopontin as a means to cope with environmental insults: Regulation of inflammation, tissue remodeling, and cell survival. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujisawa, Y.; Matsuda, K.; Uehara, T. Osteopontin enhances the migration of lung fibroblasts via upregulation of interleukin-6 through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway. Biol. Chem. 2020, 401, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, A.; Gibson, K.; Cisneros, J.; Richards, T.J.; Yang, Y.; Becerril, C.; Yousem, S.; Herrera, I.; Ruiz, V.; Selman, M.; et al. Up-Regulation and Profibrotic Role of Osteopontin in Human Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.W.; Morrison, L.D.; Todd, J.L.; Snyder, L.; Thompson, J.W.; Soderblom, E.J.; Plonk, K.; Weinhold, K.J.; Townsend, R.; Minnich, A.; et al. Quantitative Proteomics of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadota, J.; Mizunoe, S.; Mito, K.; Mukae, H.; Yoshioka, S.; Kawakami, K.; Koguchi, Y.; Fukushima, K.; Kon, S.; Kohno, S.; et al. High plasma concentrations of osteopontin in patients with interstitial pneumonia. Respir. Med. 2005, 99, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dai, J.; Cai, H.; Li, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Min, H.; Wen, Y.; Yang, J.; Gao, Q.; Shi, Y.; Yi, L. Association between telomere length and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2015, 20, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, B.D.; Lee, J.S.; Kozlitina, J.; Noth, I.; Devine, M.S.; Glazer, C.S.; Torres, F.; Kaza, V.; E Girod, C.; Jones, K.D.; et al. Effect of telomere length on survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An observational cohort study with independent validation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2014, 2, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peljto, A.L.; Zhang, Y.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Ma, S.-F.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Richards, T.J.; Silveira, L.J.; Lindell, K.O.; Steele, M.P.; Loyd, J.; et al. Association Between the MUC5B Promoter Polymorphism and Survival in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. JAMA 2013, 309, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Peng, H.; Cao, M.; Li, Y.; Xu, Q.; Xin, X.; Zhou, K.; Liang, G.; Cai, H.; et al. The relationship between MUC5B promoter, TERT polymorphisms and telomere lengths with radiographic extent and survival in a Chinese IPF cohort. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Hu, Y.; Shang, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y. Association between MUC5B polymorphism and susceptibility and severity of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 14953–14958. [Google Scholar]

- Bonella, F.; Campo, I.; Zorzetto, M.; Boerner, E.; Ohshimo, S.; Theegarten, D.; Taube, C.; Costabel, U. Potential clinical utility of MUC5B und TOLLIP single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the management of patients with IPF. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinder, B.W.; Brown, K.K.; McCormack, F.; Ix, J.H.; Kervitsky, A.; Schwarz, M.I.; King, T.E. Serum Surfactant Protein-A Is a Strong Predictor of Early Mortality in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2009, 135, 1557–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H.; Fujishima, T.; Koba, H.; Murakami, S.; Kurokawa, K.; Shibuya, Y.; Shiratori, M.; Kuroki, Y.; Abe, S. Serum Surfactant Proteins A and D as Prognostic Factors in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Their Relationship to Disease Extent. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 162, 1109–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, T.M.; Oballa, E.; Simpson, J.K.; Porte, J.; Habgood, A.; A Fahy, W.; Flynn, A.; Molyneaux, P.L.; Braybrooke, R.; Divyateja, H.; et al. An epithelial biomarker signature for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An analysis from the multicentre PROFILE cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 946–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, A.; Kondo, K.; Nakajima, M.; Matsushima, T.; Takahashi, T.; Nishimura, M.; Bando, M.; Sugiyama, Y.; Totani, Y.; Ishizaki, T.; et al. Prognostic value of circulating KL-6 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2006, 11, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, H.; Kushima, H.; Kinoshita, Y.; Fujita, M.; Watanabe, K. The serum KL-6 levels in untreated idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis can naturally decline in association with disease progression. Clin. Respir. J. 2018, 12, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, H.; Kurishima, K.; Ishikawa, H.; Ohtsuka, M. Increased levels of KL-6 and subsequent mortality in patients with interstitial lung diseases. J. Intern. Med. 2006, 260, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, F.; Jiang, C.; Yang, Y.; Pu, H.; Li, W.; Zhong, Z. Clinical Research on Prognostic Evaluation of Subjects With IPF by Peripheral Blood Biomarkers, Quantitative Imaging Characteristics and Pulmonary Function Parameters. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2020, 56, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.W.; Do, K.H.; Jang, S.J.; Colby, T.V.; Han, S.; Kim, D.S. Blood biomarkers MMP-7 and SP-A: Predictors of outcome in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2013, 143, 1422–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloisio, E.; Braga, F.; Puricelli, C.; Panteghini, M. Prognostic role of Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) measurement in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, K.; Nagata, N.; Kumazoe, H.; Oda, K.; Ishimoto, H.; Yoshimi, M.; Takata, S.; Hamada, M.; Koreeda, Y.; Takakura, K.; et al. Prognostic value of serial serum KL-6 measurements in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Investig. 2017, 55, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohshimo, S.; Ishikawa, N.; Horimasu, Y.; Hattori, N.; Hirohashi, N.; Tanigawa, K.; Kohno, N.; Bonella, F.; Guzman, J.; Costabel, U. Baseline KL-6 predicts increased risk for acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Med. 2014, 108, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuzawa, Y.; Kawashima, T.; Kuwabara, R.; Hayakawa, S.; Irie, T.; Yoshida, T.; Rikitake, H.; Wakabayashi, T.; Okada, N.; Kawashima, K.; et al. Change in serum marker of oxidative stress in the progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, D.N.; Armstrong, M.E.; Trujillo, G.; Cooke, G.; Keane, M.P.; Fallon, P.G.; Simpson, A.J.; Millar, A.B.; McGrath, E.E.; Whyte, M.K.; et al. The Toll-like Receptor 3 L412F Polymorphism and Disease Progression in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 1442–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, D.N.; E Armstrong, M.; Kooblall, M.; Donnelly, S.C. Targeting defective Toll-like receptor-3 function and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Exp. Opin. Ther. Targets 2014, 19, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamai, K.; Iwamoto, H.; Ishikawa, N.; Horimasu, Y.; Masuda, T.; Miyamoto, S.; Nakashima, T.; Ohshimo, S.; Fujitaka, K.; Hamada, H.; et al. Comparative Study of Circulating MMP-7, CCL18, KL-6, SP-A, and SP-D as Disease Markers of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Dis. Mark. 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, J.L.; Vinisko, R.; Liu, Y.; Neely, M.L.; Overton, R.; Flaherty, K.R.; Noth, I.; Newby, L.K.; Lasky, J.A.; Olman, M.A.; et al. Circulating matrix metalloproteinases and tissue metalloproteinase inhibitors in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the multicenter IPF-PRO Registry cohort. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, K.; Bailey, N.W.; Yang, J.; Steel, M.P.; Groshong, S.; Kervitsky, L.; Brown, K.K.; Schwarz, M.I.; Schwartz, D.A. Molecular Phenotypes Distinguish Patients with Relatively Stable from Progressive Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF). PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, X.; Qiu, X.; Xie, M.; Tian, Y.; Min, C.; Huang, M.; HongYan, W.; Chen, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; et al. Prognostic Value of Serum Osteopontin in Acute Exacerbation of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. BioMed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, M.; Izuhara, K.; Ohta, S.; Ono, J.; Hoshino, T. Ability of Periostin as a New Biomarker of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Single Mol. Single Cell Seq. 2019, 1132, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Otsuka, M.; Chiba, H.; Ikeda, K.; Mori, Y.; Umeda, Y.; Nishikiori, H.; Kuronuma, K.; Takahashi, H. Surfactant protein A as a biomarker of outcomes of anti-fibrotic drug therapy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K.; Shiratori, M.; Nishikiori, H.; Yokoo, K.; Asai, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Saito, A.; Kuronuma, K.; Otsuka, M.; Chiba, H.; et al. Serum surfactant protein D predicts the outcome of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with pirfenidone. Respir. Med. 2017, 131, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K.; Chiba, H.; Nishikiori, H.; Azuma, A.; Kondoh, Y.; Ogura, T.; Taguchi, Y.; Ebina, M.; Sakaguchi, H.; Miyazawa, S.; et al. Serum surfactant protein D as a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A post-hoc analysis of the phase 3 trial in Japan. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonella, F.; Ohshimo, S.; Boerner, E.; Guzman, J.; Wessendorf, T.E.; Costabel, U. Serum Kl-6 Levels Correlate with Response to Pirfenidone in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 191, A4398. [Google Scholar]

- Bergantini, L.; Bargagli, E.; Cameli, P.; Cekorja, B.; Lanzarone, N.; Pianigiani, L.; Vietri, L.; Bennett, D.; Sestini, P.; Rottoli, P. Serial KL-6 analysis in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with nintedanib. Respir. Investig. 2019, 57, 290–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Okamoto, M.; Fujimoto, K.; Ebata, T.; Tominaga, M.; Nouno, T.; Zaizen, Y.; Kaieda, S.; Tsuda, T.; Kawayama, T.; et al. A retrospective study of the tolerability of nintedanib for severe idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the real world. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adegunsoye, A.; Alqalyoobi, S.; Linderholm, A.; Bowman, W.S.; Lee, C.T.; Pugashetti, J.V.; Sarma, N.; Ma, S.-F.; Haczku, A.; Sperling, A.; et al. Circulating Plasma Biomarkers of Survival in Antifibrotic-Treated Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2020, 158, 1526–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).