CDKs in Sarcoma: Mediators of Disease and Emerging Therapeutic Targets

Abstract

1. Introduction

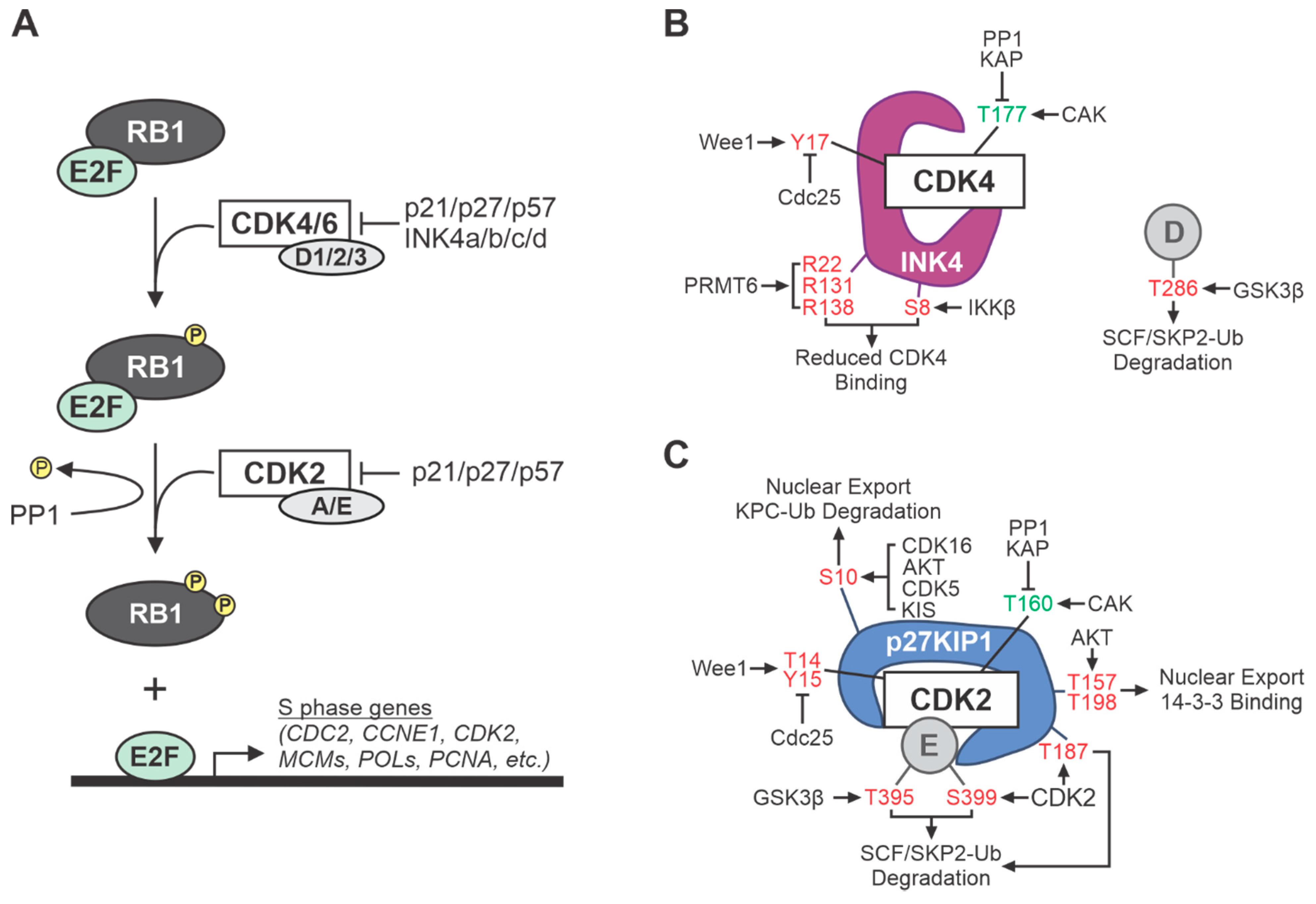

2. Cell Cycle CDKs

3. CDK Pathway Alterations in Prevalent Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcomas

4. CDK Pathway Alterations in Common Adult Sarcomas

4.1. Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma (UPS)

4.2. Myxofibrosarcoma (MFS)

4.3. Liposarcoma (LPS)

4.4. Leiomyosarcoma (LMS)

4.5. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors (MPNSTs)

4.6. Synovial Sarcoma (SS)

4.7. Chondrosarcoma (CS)

5. CDK Pathway Alterations in Common Childhood and Adolescent Sarcomas

5.1. Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS)

5.2. Osteosarcoma (OS)

5.3. Ewing Sarcoma (EwS)

6. Transcriptional and “Other” CDKs

7. CDK Pathway Alterations—Are They Drivers or Passengers in Sarcoma Development?

8. CDK-Targeted Anti-Cancer Therapy

9. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bleloch, J.S.; Ballim, R.D.; Kimani, S.; Parkes, J.; Panieri, E.; Willmer, T.; Prince, S. Managing sarcoma: Where have we come from and where are we going? Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2017, 9, 637–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, J.W.; Jones, K.B.; Barrott, J.J. Sarcoma-The standard-bearer in cancer discovery. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018, 126, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dancsok, A.R.; Asleh-Aburaya, K.; Nielsen, T.O. Advances in sarcoma diagnostics and treatment. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 7068–7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Kaldis, P. Cdks, cyclins and CKIs: Roles beyond cell cycle regulation. Development 2013, 140, 3079–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumbres, M. Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.K.; Hornicek, F.J.; Kan, Q.; Duan, Z. The emerging roles and therapeutic potential of cyclin-dependent kinase 11 (CDK11) in human cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 40846–40859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydbring, P.; Malumbres, M.; Sicinski, P. Non-canonical functions of cell cycle cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, D.J.; Endicott, J.A. Structural insights into the functional diversity of the CDK-cyclin family. Open Biol. 2018, 8, 180112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shupp, A.; Casimiro, M.C.; Pestell, R.G. Biological functions of CDK5 and potential CDK5 targeted clinical treatments. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 17373–17382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingham, M.; Schwartz, G.K. Cell-Cycle Therapeutics Come of Age. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 2949–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, J.Y.; Matsuoka, M.; Strom, D.K.; Sherr, C.J. Regulation of cyclin D-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4) by cdk4-activating kinase. Mol. Cell Biol. 1994, 14, 2713–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldis, P.; Russo, A.A.; Chou, H.S.; Pavletich, N.P.; Solomon, M.J. Human and yeast cdk-activating kinases (CAKs) display distinct substrate specificities. Mol. Biol. Cell 1998, 9, 2545–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockstaele, L.; Bisteau, X.; Paternot, S.; Roger, P.P. Differential regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and CDK6, evidence that CDK4 might not be activated by CDK7, and design of a CDK6 activating mutation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 29, 4188–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bockstaele, L.; Kooken, H.; Libert, F.; Paternot, S.; Dumont, J.E.; de Launoit, Y.; Roger, P.P.; Coulonval, K. Regulated activating Thr172 phosphorylation of cyclin-dependent kinase 4(CDK4): Its relationship with cyclins and CDK “inhibitors”. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 26, 5070–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhart, D.L.; Sage, J. Cellular mechanisms of tumour suppression by the retinoblastoma gene. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevins, J.R. The Rb/E2F pathway and cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbour, J.W.; Dean, D.C. The Rb/E2F pathway: Expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 2393–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochegger, H.; Takeda, S.; Hunt, T. Cyclin-dependent kinases and cell-cycle transitions: Does one fit all? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutros, R.; Lobjois, V.; Ducommun, B. CDC25 phosphatases in cancer cells: Key players? Good targets? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjansdottir, K.; Rudolph, J. Cdc25 phosphatases and cancer. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, A.; Dowdy, S.F.; Roberts, J.M. CDK inhibitors: Cell cycle regulators and beyond. Dev. Cell 2008, 14, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelle, D.E.; Nteeba, J.; Darbro, B.W. The INK4a/ARF Locus. In Encyclopedia of Cell Biology; Bradshaw, R., Stahl, P., Eds.; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 447–457. [Google Scholar]

- Sherr, C.J. Ink4-Arf locus in cancer and aging. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2012, 1, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, M.; Hannon, G.J.; Beach, D. A new regulatory motif in cell-cycle control. causing specific inhibition of cyclin D/CDK4. Nature 1993, 366, 704–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quelle, D.E.; Zindy, F.; Ashmun, R.A.; Sherr, C.J. Alternative reading frames of the INK4a tumor suppressor gene encode two unrelated proteins capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cell 1995, 83, 993–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, A.J.; Oren, M. The first 30 years of p53: Growing ever more complex. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C.J.; Weber, J.D. The ARF/p53 pathway. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2000, 10, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpless, N.E. Ink4a/Arf links senescence and aging. Exp. Gerontol. 2004, 39, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherr, C.J. The INK4a/ARF network in tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherr, C.J.; Bertwistle, D.; Den Besten, W.; Kuo, M.L.; Sugimoto, M.; Tago, K.; Williams, R.T.; Zindy, F.; Roussel, M.F. p53-Dependent and -independent functions of the Arf tumor suppressor. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2005, 70, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, A.; Han, S.Y.; Song, J. Regulatory Network of ARF in Cancer Development. Mol. Cells 2018, 41, 381–389. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J.D.; Jeffers, J.R.; Rehg, J.E.; Randle, D.H.; Lozano, G.; Roussel, M.F.; Sherr, C.J.; Zambetti, G.P. p53-independent functions of the p19(ARF) tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 2358–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherr, C.J. Divorcing ARF and p53: An unsettled case. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forys, J.T.; Kuzmicki, C.E.; Saporita, A.J.; Winkeler, C.L.; Maggi, L.B., Jr.; Weber, J.D. ARF and p53 coordinate tumor suppression of an oncogenic IFN-beta-STAT1-ISG15 signaling axis. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 514–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivandi, M.; Khorrami, M.S.; Fiuji, H.; Shahidsales, S.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Jazayeri, M.H.; Hassanian, S.M.; Ferns, G.A.; Saghafi, N.; Avan, A. The 9p21 locus: A potential therapeutic target and prognostic marker in breast cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 5170–5179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.Q.; Przybyl, J.; Trabucco, S.E.; Frampton, G.; Hastie, T.; van de Rijn, M.; Ganjoo, K.N. A clinico-genomic analysis of soft tissue sarcoma patients reveals CDKN2A deletion as a biomarker for poor prognosis. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2019, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, S.D.; Pissaloux, D.; Crombe, A.; Coindre, J.M.; Le Loarer, F. Pleomorphic Sarcomas: The State of the Art. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2019, 12, 63–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillou, L.; Aurias, A. Soft tissue sarcomas with complex genomic profiles. Virchows Arch. 2010, 456, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibon, F.; Mairal, A.; Freneaux, P.; Terrier, P.; Coindre, J.M.; Sastre, X.; Aurias, A. The RB1 gene is the target of chromosome 13 deletions in malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 6339–6345. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, A.H.; Tsai, M.M.; Venzon, D.J.; Wright, C.F.; Lack, E.E.; O’Leary, T.J. MDM2 amplification, P53 mutation, and accumulation of the P53 gene product in malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 1996, 5, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perot, G.; Chibon, F.; Montero, A.; Lagarde, P.; de The, H.; Terrier, P.; Guillou, L.; Ranchere, D.; Coindre, J.M.; Aurias, A. Constant p53 pathway inactivation in a large series of soft tissue sarcomas with complex genetics. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 177, 2080–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchakjian, M.R.; Merritt, N.M.; Moose, D.L.; Dupuy, A.J.; Tanas, M.R.; Henry, M.D. A Trp53fl/flPtenfl/fl mouse model of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma mediated by adeno-Cre injection and in vivo bioluminescence imaging. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Puebla, M.L.; Robles, A.I.; Conti, C.J. Ras activity and cyclin D1 expression: An essential mechanism of mouse skin tumor development. Mol. Carcinog. 1999, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylayeva-Gupta, Y.; Grabocka, E.; Bar-Sagi, D. RAS oncogenes: Weaving a tumorigenic web. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Lisanti, M.P.; Liao, D.J. Reviewing once more the c-myc and Ras collaboration: Converging at the cyclin D1-CDK4 complex and challenging basic concepts of cancer biology. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wee, P.; Wang, Z. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Cell Proliferation Signaling Pathways. Cancers 2017, 9, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, C.; Romagosa, C.; Hernandez-Losa, J.; Simonetti, S.; Valverde, C.; Moline, T.; Somoza, R.; Perez, M.; Velez, R.; Verges, R.; et al. RAS/MAPK pathway hyperactivation determines poor prognosis in undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas. Cancer 2016, 122, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, R.D. Emerging targets in sarcoma: Rising to the challenge of RAS signaling in undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Cancer 2016, 122, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, R.D.; Mito, J.K.; Kirsch, D.G. Animal models of soft-tissue sarcoma. Dis. Model. Mech. 2010, 3, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.; Lin, A.W.; McCurrach, M.E.; Beach, D.; Lowe, S.W. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 1997, 88, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.W.; Barradas, M.; Stone, J.C.; van Aelst, L.; Serrano, M.; Lowe, S.W. Premature senescence involving p53 and p16 is activated in response to constitutive MEK/MAPK mitogenic signaling. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 3008–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmero, I.; Pantoja, C.; Serrano, M. p19ARF links the tumour suppressor p53 to Ras. Nature 1998, 395, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamijo, T.; Bodner, S.; van de Kamp, E.; Randle, D.H.; Sherr, C.J. Tumor spectrum in ARF-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 2217–2222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, D.G.; Dinulescu, D.M.; Miller, J.B.; Grimm, J.; Santiago, P.M.; Young, N.P.; Nielsen, G.P.; Quade, B.J.; Chaber, C.J.; Schultz, C.P.; et al. A spatially and temporally restricted mouse model of soft tissue sarcoma. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 992–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, R.D.; Mito, J.K.; Eward, W.C.; Chitalia, R.; Sachdeva, M.; Ma, Y.; Barretina, J.; Dodd, L.; Kirsch, D.G. NF1 deletion generates multiple subtypes of soft-tissue sarcoma that respond to MEK inhibition. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 1906–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, C.L.; Wang, W.L.; Lazar, A.J.; Torres, K.E. Myxofibrosarcoma. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive and Integrated Genomic Characterization of Adult Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Cell 2017, 171, 950–965.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimoto, M.; Yamada, Y.; Ishihara, S.; Kohashi, K.; Toda, Y.; Ito, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Furue, M.; Nakashima, Y.; Oda, Y. Comparative Study of Myxofibrosarcoma With Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma: Histopathologic and Clinicopathologic Review. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2020, 44, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, K.; Hosoda, F.; Arai, Y.; Nakamura, H.; Hama, N.; Totoki, Y.; Yoshida, A.; Nagai, M.; Kato, M.; Arakawa, E.; et al. Integrated genetic and epigenetic analysis of myxofibrosarcoma. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.W.; Li, C.F.; Kao, Y.C.; Wang, J.W.; Fang, F.M.; Wang, Y.H.; Wu, W.R.; Wu, L.C.; Hsing, C.H.; Li, S.H.; et al. Recurrent amplification at 7q21.2 Targets CDK6 gene in primary myxofibrosarcomas and identifies CDK6 overexpression as an independent adverse prognosticator. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 2716–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerson, M.; Harlow, E. Identification of G1 kinase activity for cdk6, a novel cyclin D partner. Mol. Cell Biol. 1994, 14, 2077–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumbres, M.; Barbacid, M. To cycle or not to cycle: A critical decision in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2001, 1, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barretina, J.; Taylor, B.S.; Banerji, S.; Ramos, A.H.; Lagos-Quintana, M.; Decarolis, P.L.; Shah, K.; Socci, N.D.; Weir, B.A.; Ho, A.; et al. Subtype-specific genomic alterations define new targets for soft-tissue sarcoma therapy. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratner, N.; Miller, S.J. A RASopathy gene commonly mutated in cancer: The neurofibromatosis type 1 tumour suppressor. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manji, G.A.; Schwartz, G.K. Managing Liposarcomas: Cutting Through the Fat. J. Oncol. Pract. 2016, 12, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crago, A.M.; Dickson, M.A. Liposarcoma: Multimodality Management and Future Targeted Therapies. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 25, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.S.E.; Colborne, S.; Hughes, C.S.; Morin, G.B.; Nielsen, T.O. The FUS-DDIT3 Interactome in Myxoid Liposarcoma. Neoplasia 2019, 21, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.V.; Crozat, A.; Tabaee, A.; Philipson, L.; Ron, D. CHOP (GADD153) and its oncogenic variant, TLS-CHOP, have opposing effects on the induction of G1/S arrest. Genes Dev. 1994, 8, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, A.; Willen, H.; Goransson, M.; Engstrom, K.; Meis-Kindblom, J.M.; Stenman, G.; Kindblom, L.G.; Aman, P. Abnormal expression of cell cycle regulators in FUS-CHOP carrying liposarcomas. Int. J. Oncol. 2004, 25, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Losada, J.; Sanchez-Martin, M.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.A.; Perez-Mancera, P.A.; Pintado, B.; Flores, T.; Battaner, E.; Sanchez-Garcia, I. Liposarcoma initiated by FUS/TLS-CHOP: The FUS/TLS domain plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of liposarcoma. Oncogene 2000, 19, 6015–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idbaih, A.; Coindre, J.M.; Derre, J.; Mariani, O.; Terrier, P.; Ranchere, D.; Mairal, A.; Aurias, A. Myxoid malignant fibrous histiocytoma and pleomorphic liposarcoma share very similar genomic imbalances. Lab. Invest. 2005, 85, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C.; George, S. Leiomyosarcoma. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 27, 957–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernando, E.; Charytonowicz, E.; Dudas, M.E.; Menendez, S.; Matushansky, I.; Mills, J.; Socci, N.D.; Behrendt, N.; Ma, L.; Maki, R.G.; et al. The AKT-mTOR pathway plays a critical role in the development of leiomyosarcomas. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agaram, N.P.; Zhang, L.; LeLoarer, F.; Silk, T.; Sung, Y.S.; Scott, S.N.; Kuk, D.; Qin, L.X.; Berger, M.F.; Antonescu, C.R.; et al. Targeted exome sequencing profiles genetic alterations in leiomyosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2016, 55, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dei Tos, A.P.; Maestro, R.; Doglioni, C.; Piccinin, S.; Libera, D.D.; Boiocchi, M.; Fletcher, C.D. Tumor suppressor genes and related molecules in leiomyosarcoma. Am. J. Pathol. 1996, 148, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Du, X.; Chen, K.; Ylipaa, A.; Lazar, A.J.; Trent, J.; Lev, D.; Pollock, R.; Hao, X.; Hunt, K.; et al. Genetic aberrations in soft tissue leiomyosarcoma. Cancer Lett. 2009, 275, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfhage, J.; Lombard, D.B. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors: From Epigenome to Bedside. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, M.M.; Antonescu, C.R.; Fletcher, C.D.M.; Kim, A.; Lazar, A.J.; Quezado, M.M.; Reilly, K.M.; Stemmer-Rachamimov, A.; Stewart, D.R.; Viskochil, D.; et al. Histopathologic evaluation of atypical neurofibromatous tumors and their transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in patients with neurofibromatosis 1-a consensus overview. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 67, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staedtke, V.; Bai, R.Y.; Blakeley, J.O. Cancer of the Peripheral Nerve in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Stewart, D.R.; Reilly, K.M.; Viskochil, D.; Miettinen, M.M.; Widemann, B.C. Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors State of the Science: Leveraging Clinical and Biological Insights into Effective Therapies. Sarcoma 2017, 2017, 7429697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, H.M.; Shilatifard, A. The JARID2-PRC2 duality. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohl, A.S.; Kahen, E.; Yoder, S.J.; Teer, J.K.; Reed, D.R. The genomic landscape of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Diverse drivers of Ras pathway activation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourea, H.P.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Dudas, M.; Leung, D.; Woodruff, J.M. Expression of p27(kip) and oTher. cell cycle regulators in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas: The emerging role of p27(kip) in malignant transformation of neurofibromas. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 155, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlmeyer, J.L.; Kaemmer, C.A.; Pulliam, C.; Maharjan, C.K.; Moreno Samayoa, A.; Major, H.J.; Cornick, K.E.; Knepper-Adrian, V.; Khanna, R.; Sieren, J.C.; et al. RABL6A is an essential driver of MPNSTs that negatively regulates the RB1 pathway and sensitizes tumor cells to CDK4/6 inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, J.; Muniz, V.P.; Falls, K.C.; Reed, S.M.; Taghiyev, A.F.; Quelle, F.W.; Gourronc, F.A.; Klingelhutz, A.J.; Major, H.J.; Askeland, R.W.; et al. RABL6A promotes G1-S phase progression and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor cell proliferation in an Rb1-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 6661–6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Ji, F.; Sun, J.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yue, H. RBEL1 is required for osteosarcoma cell proliferation via inhibiting retinoblastoma 1. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, K.; An, J.; Montalbano, J.; Shi, J.; Corcoran, C.; He, Q.; Sun, H.; Sheikh, M.S.; Huang, Y. Negative regulation of p53 by Ras superfamily protein RBEL1A. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126 Pt 11, 2436–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichowski, K.; Shih, T.S.; Schmitt, E.; Santiago, S.; Reilly, K.; McLaughlin, M.E.; Bronson, R.T.; Jacks, T. Mouse models of tumor development in neurofibromatosis type 1. Science 1999, 286, 2172–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keng, V.W.; Rahrmann, E.P.; Watson, A.L.; Tschida, B.R.; Moertel, C.L.; Jessen, W.J.; Rizvi, T.A.; Collins, M.H.; Ratner, N.; Largaespada, D.A. PTEN and NF1 inactivation in Schwann cells produces a severe phenotype in the peripheral nervous system that promotes the development and malignant progression of peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3405–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregorian, C.; Nakashima, J.; Dry, S.M.; Nghiemphu, P.L.; Smith, K.B.; Ao, Y.; Dang, J.; Lawson, G.; Mellinghoff, I.K.; Mischel, P.S.; et al. PTEN dosage is essential for neurofibroma development and malignant transformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19479–19484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, K.S.; Klesse, L.J.; Velasco-Miguel, S.; Meyers, K.; Rushing, E.J.; Parada, L.F. Mouse tumor model for neurofibromatosis type 1. Science 1999, 286, 2176–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, V.W.; Watson, A.L.; Rahrmann, E.P.; Li, H.; Tschida, B.R.; Moriarity, B.S.; Choi, K.; Rizvi, T.A.; Collins, M.H.; Wallace, M.R.; et al. Conditional Inactivation of Pten with EGFR Overexpression in Schwann Cells Models Sporadic MPNST. Sarcoma 2012, 2012, 620834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Chen, M.; Whitley, M.J.; Kuo, H.C.; Xu, E.S.; Walens, A.; Mowery, Y.M.; Van Mater, D.; Eward, W.C.; Cardona, D.M.; et al. Generation and comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 and Cre-mediated genetically engineered mouse models of sarcoma. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, S.D.; He, Y.; Smith, A.; Jiang, L.; Lu, Q.; Mund, J.; Li, X.; Bessler, W.; Qian, S.; Dyer, W.; et al. Cdkn2a (Arf) loss drives NF1-associated atypical neurofibroma and malignant transformation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 2752–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, M.J.; Pulice, J.L.; Nakayama, R.T.; Mashtalir, N.; Ingram, D.R.; Jaffe, J.D.; Shern, J.F.; Khan, J.; Hornick, J.L.; Lazar, A.J.; et al. SSX-mediated chromatin engagement and targeting of BAF complexes activates oncogenic transcription in synovial sarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki, S.; Fukuta, M.; Sekiguchi, K.; Jin, Y.; Nagata, S.; Hayakawa, K.; Hineno, S.; Okamoto, T.; Watanabe, M.; Woltjen, K.; et al. SS18-SSX, the Oncogenic Fusion Protein in Synovial Sarcoma, Is a Cellular Context-Dependent Epigenetic Modifier. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Beaino, M.; Araujo, D.M.; Lazar, A.J.; Lin, P.P. Synovial Sarcoma: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment Identification of New Biologic Targets to Improve Multimodal Therapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 24, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, T.O.; Poulin, N.M.; Ladanyi, M. Synovial Sarcoma: Recent Discoveries as a Roadmap to New Avenues for Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, M.; Hancock, J.D.; Coffin, C.M.; Lessnick, S.L.; Capecchi, M.R. A conditional mouse model of synovial sarcoma: Insights into a myogenic origin. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Seebacher, N.A.; Garbutt, C.; Ma, H.Z.; Gao, P.; Xiao, T.; Hornicek, F.J.; Duan, Z.F. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 as a potential therapeutic strategy for treatment of synovial sarcoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speetjens, F.M.; de Jong, Y.; Gelderblom, H.; Bovee, J.V.M.G. Molecular oncogenesis of chondrosarcoma: Impact for targeted treatment. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2016, 28, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, G.; Wilky, B.A.; Paz-Mejia, A.; Rosenberg, A.; Trent, J.C. The biology and management of cartilaginous tumors: A role for targeting isocitrate dehydrogenase. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2015, e648–e655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, R.; Fuchs, J.; Rodeberg, D. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2016, 25, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.J.; Pressey, J.G.; Barr, F.G. Molecular pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2002, 1, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bretones, G.; Delgado, M.D.; Leon, J. Myc and cell cycle control. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1849, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, C.V.; O’Donnell, K.A.; Zeller, K.I.; Nguyen, T.; Osthus, R.C.; Li, F. The c-Myc target gene network. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2006, 16, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossatz, U.; Dietrich, N.; Zender, L.; Buer, J.; Manns, M.P.; Malek, N.P. Skp2-dependent degradation of p27kip1 is essential for cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 2004, 18, 2602–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Xie, W.; Kuhn, D.J.; Voorhees, P.M.; Lopez-Girona, A.; Mendy, D.; Corral, L.G.; Krenitsky, V.P.; Xu, W.; Moutouh-de Parseval, L.; et al. Targeting the p27 E3 ligase SCF(Skp2) results in p27- and Skp2-mediated cell-cycle arrest and activation of autophagy. Blood 2008, 111, 4690–4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretones, G.; Acosta, J.C.; Caraballo, J.M.; Ferrandiz, N.; Gomez-Casares, M.T.; Albajar, M.; Blanco, R.; Ruiz, P.; Hung, W.C.; Albero, M.P.; et al. SKP2 oncogene is a direct MYC target gene and MYC down-regulates p27(KIP1) through SKP2 in human leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 9815–9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydbring, P.; Castell, A.; Larsson, L.G. MYC Modulation around the CDK2/p27/SKP2 Axis. Genes 2017, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, C. PAX3-FKHR transformation increases 26 S proteasome-dependent degradation of p27Kip1, a potential role for elevated Skp2 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shern, J.F.; Yohe, M.E.; Khan, J. Pediatric Rhabdomyosarcoma. Crit. Rev. Oncogenet. 2015, 20, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milewski, D.; Pradhan, A.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y.; Le, T.; Turpin, B.; Kalinichenko, V.V.; Kalin, T.V. FoxF1 and FoxF2 transcription factors synergistically promote rhabdomyosarcoma carcinogenesis by repressing transcription of p21(Cip1) CDK inhibitor. Oncogene 2017, 36, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishijo, K.; Chen, Q.R.; Zhang, L.; McCleish, A.T.; Rodriguez, A.; Cho, M.J.; Prajapati, S.I.; Gelfond, J.A.; Chisholm, G.B.; Michalek, J.E.; et al. Credentialing a preclinical mouse model of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 2902–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.; Brown, H.L. Understanding osteosarcomas. JAAPA 2018, 31, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansara, M.; Teng, M.W.; Smyth, M.J.; Thomas, D.M. Translational biology of osteosarcoma. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansieau, S.; Bastid, J.; Doreau, A.; Morel, A.P.; Bouchet, B.P.; Thomas, C.; Fauvet, F.; Puisieux, I.; Doglioni, C.; Piccinin, S.; et al. Induction of EMT by twist proteins as a collateral effect of tumor-promoting inactivation of premature senescence. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shen, J.K.; Yu, Z.; Hornicek, F.J.; Kan, Q.; Duan, Z. Expression and therapeutic implications of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) in osteosarcoma. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864 5 Pt A, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feugeas, O.; Guriec, N.; Babin-Boilletot, A.; Marcellin, L.; Simon, P.; Babin, S.; Thyss, A.; Hofman, P.; Terrier, P.; Kalifa, C.; et al. Loss of heterozygosity of the RB gene is a poor prognostic factor in patients with osteosarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996, 14, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.D.; Luu, H.H. Osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat. Res. 2014, 162, 65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, S.D.; Calo, E.; Landman, A.S.; Danielian, P.S.; Miller, E.S.; West, J.C.; Fonhoue, B.D.; Caron, A.; Bronson, R.; Bouxsein, M.L.; et al. Metastatic osteosarcoma induced by inactivation of Rb and p53 in the osteoblast lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11851–11856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieren, J.C.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Wang, X.J.; Davis, B.T.; Newell, J.D., Jr.; Hammond, E.; Rohret, J.A.; Rohret, F.A.; Struzynski, J.T.; Goeken, J.A.; et al. Development and translational imaging of a TP53 porcine tumorigenesis model. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 4052–4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.Y.; Gardner, J.M.; Lucas, D.R.; McHugh, J.B.; Patel, R.M. Ewing sarcoma. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2014, 31, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunewald, T.G.P.; Cidre-Aranaz, F.; Surdez, D.; Tomazou, E.M.; de Alava, E.; Kovar, H.; Sorensen, P.H.; Delattre, O.; Dirksen, U. Ewing sarcoma. Nat. Rev. Dis Primers 2018, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar, N.; Hawkins, D.S.; Dirksen, U.; Lewis, I.J.; Ferrari, S.; Le Deley, M.C.; Kovar, H.; Grimer, R.; Whelan, J.; Claude, L.; et al. Ewing Sarcoma: Current Management and Future Approaches Through Collaboration. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3036–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Xu, R.; Prieto, V.G.; Lee, P. Molecular classification of soft tissue sarcomas and its clinical applications. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2010, 3, 416–428. [Google Scholar]

- Knott, M.M.; Dallmayer, M.; Grunewald, T.G. Next steps in preventing Ewing sarcoma progression. Fut. Oncol. 2016, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzetti, G.A.; Laud-Duval, K.; van der Ent, W.; Brisac, A.; Irondelle, M.; Aubert, S.; Dirksen, U.; Bouvier, C.; de Pinieux, G.; Snaar-Jagalska, E.; et al. Cell-to-cell heterogeneity of EWSR1-FLI1 activity determines proliferation/migration choices in Ewing sarcoma cells. Oncogene 2017, 36, 3505–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauphinot, L.; De Oliveira, C.; Melot, T.; Sevenet, N.; Thomas, V.; Weissman, B.E.; Delattre, O. Analysis of the expression of cell cycle regulators in Ewing cell lines: EWS-FLI-1 modulates p57KIP2and c-Myc expression. Oncogene 2001, 20, 3258–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Toomey, E.C.; Schiffman, J.D.; Lessnick, S.L. Recent advances in the molecular pathogenesis of Ewing’s sarcoma. Oncogene 2010, 29, 4504–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torchia, E.C.; Boyd, K.; Rehg, J.E.; Qu, C.; Baker, S.J. EWS/FLI-1 induces rapid onset of myeloid/erythroid leukemia in mice. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 7918–7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.P.; Pandey, M.K.; Jin, F.; Xiong, S.; Deavers, M.; Parant, J.M.; Lozano, G. EWS-FLI1 induces developmental abnormalities and accelerates sarcoma formation in a transgenic mouse model. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 8968–8975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Teckie, S.; Wiesner, T.; Ran, L.; Prieto Granada, C.N.; Lin, M.; Zhu, S.; Cao, Z.; Liang, Y.; Sboner, A.; et al. PRC2 is recurrently inactivated through EED or SUZ12 loss in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 1227–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Ylipaa, A.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, K.; Nykter, M.; Trent, J.; Ratner, N.; Lev, D.C.; Zhang, W. Genomic and molecular characterization of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor identifies the IGF1R pathway as a primary target for treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 7563–7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agesen, T.H.; Florenes, V.A.; Molenaar, W.M.; Lind, G.E.; Berner, J.M.; Plaat, B.E.; Komdeur, R.; Myklebost, O.; van den Berg, E.; Lothe, R.A. Expression patterns of cell cycle components in sporadic and neurofibromatosis type 1-related malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2005, 64, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrone, F.; Tabano, S.; Colombo, F.; Dagrada, G.; Birindelli, S.; Gronchi, A.; Colecchia, M.; Pierotti, M.A.; Pilotti, S. p15INK4b, p14ARF, and p16INK4a inactivation in sporadic and neurofibromatosis type 1-related malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2003, 9, 4132–4138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, G.P.; Stemmer-Rachamimov, A.O.; Ino, Y.; Moller, M.B.; Rosenberg, A.E.; Louis, D.N. Malignant transformation of neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis 1 is associated with CDKN2A/p16 inactivation. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 155, 1879–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beert, E.; Brems, H.; Daniels, B.; De Wever, I.; Van Calenbergh, F.; Schoenaers, J.; Debiec-Rychter, M.; Gevaert, O.; De Raedt, T.; Van Den Bruel, A.; et al. Atypical neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis type 1 are premalignant tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2011, 50, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shern, J.F.; Chen, L.; Chmielecki, J.; Wei, J.S.; Patidar, R.; Rosenberg, M.; Ambrogio, L.; Auclair, D.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.K.; et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of rhabdomyosarcoma reveals a landscape of alterations affecting a common genetic axis in fusion-positive and fusion-negative tumors. Cancer Discov. 2014, 4, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, L.C.; Morales, F.; Boffo, S.; Giordano, A. CDK9: A key player in cancer and oTher. diseases. J. Cell BioChem. 2018, 119, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Seebacher, N.A.; Xiao, T.; Hornicek, F.J.; Duan, Z. Targeting regulation of cyclin dependent kinase 9 as a novel therapeutic strategy in synovial sarcoma. J. Orthop. Res. 2019, 37, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Seebacher, N.A.; Hornicek, F.J.; Duan, Z. Cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) is a novel prognostic marker and therapeutic target in osteosarcoma. EBioMedicine 2019, 39, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos Paparidis, N.F.; Canduri, F. The Emerging Picture of CDK11: Genetic, Functional and Medicinal Aspects. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Choy, E.; Harmon, D.; Liu, X.; Nielsen, P.; Mankin, H.; Gray, N.S.; Hornicek, F.J. Systematic kinome shRNA screening identifies CDK11 (PITSLRE) kinase expression is critical for osteosarcoma cell growth and proliferation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 4580–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Sassi, S.; Shen, J.K.; Yang, X.; Gao, Y.; Osaka, E.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Yang, C.; Mankin, H.J.; et al. Targeting CDK11 in osteosarcoma cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. J. Orthop. Res. 2015, 33, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, B.; Choy, E.; Cote, G.; Harmon, D.; Ye, S.; Kan, Q.; Mankin, H.; Hornicek, F.; Duan, Z. Cyclin-dependent kinase 11 (CDK11) is crucial in the growth of liposarcoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2014, 342, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malumbres, M.; Barbacid, M. Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: A changing paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G.; Niehrs, C. Emerging links between CDK cell cycle regulators and Wnt signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2010, 20, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, W.; Jin, Q.; Huang, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, X. High expression of PFTK1 in cancer cells predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ji, Q.; Xu, X.; Li, L.; Goodman, S.B.; Bi, W.; Xu, M.; Xu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Maloney, W.J.; Ye, Q.; et al. miR-216a inhibits osteosarcoma cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis by targeting CDK14. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.P. Cdk7: A kinase at the core of transcription and in the crosshairs of cancer drug discovery. Transcription 2019, 10, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Liu, F.; Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. CDK7 inhibition is a novel therapeutic strategy against GBM both in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 5747–5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Jin, H.J.; Gao, D.M.; Wang, L.Q.; Evers, B.; Xue, Z.; Jin, G.Z.; Lieftink, C.; Beijersbergen, R.L.; Qin, W.X.; et al. A CRISPR screen identifies CDK7 as a therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Kwiatkowski, N.; Abraham, B.J.; Lee, T.I.; Xie, S.; Yuzugullu, H.; Von, T.; Li, H.; Lin, Z.; et al. CDK7-dependent transcriptional addiction in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell 2015, 163, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.Y.; Liu, Q.Y.; Cao, J.; Chen, J.W.; Liu, Z.S. Selective CDK7 inhibition with BS-181 suppresses cell proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2016, 10, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzl, I.; Witalisz-Siepracka, A.; Sexl, V. CDK8-Novel Therapeutic Opportunities. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chila, R.; Guffanti, F.; Damia, G. Role and therapeutic potential of CDK12 in human cancers. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 50, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lui, G.Y.L.; Grandori, C.; Kemp, C.J. CDK12: An emerging therapeutic target for cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2018, 71, 957–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.E.; Kim, D.G.; Lee, K.J.; Son, J.G.; Song, M.Y.; Park, Y.M.; Kim, J.J.; Cho, S.W.; Chi, S.G.; Cheong, H.S.; et al. Frequent amplification of CENPF, GMNN and CDK13 genes in hepatocellular carcinomas. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, F.; Joerg, V.; Hupe, M.C.; Roth, D.; Krupar, R.; Lubczyk, V.; Kuefer, R.; Sailer, V.; Duensing, S.; Kirfel, J.; et al. Increased mediator complex subunit CDK19 expression associates with aggressive prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 146, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fant, C.B.; Taatjes, D.J. Regulatory functions of the Mediator kinases CDK8 and CDK19. Transcription 2019, 10, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levacque, Z.; Rosales, J.L.; Lee, K.Y. Level of cdk5 expression predicts the survival of relapsed multiple myeloma patients. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 4093–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, K.; Bibb, J.A. The Emerging Role of Cdk5 in Cancer. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, K.; Lahiri, D.K. Cdk5 activity in the brain—Multiple paths of regulation. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127 Pt 11, 2391–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, K.; Castro-Rivera, E.; Tan, C.F.; Plattner, F.; Schwach, G.; Siegl, V.; Meyer, D.; Guo, A.L.; Gundara, J.; Mettlach, G.; et al. The Role of Cdk5 in Neuroendocrine Thyroid Cancer. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guen, V.J.; Gamble, C.; Flajolet, M.; Unger, S.; Thollet, A.; Ferandin, Y.; Superti-Furga, A.; Cohen, P.A.; Meijer, L.; Colas, P. CDK10/cyclin M is a protein kinase that controls ETS2 degradation and is deficient in STAR syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19525–19530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guen, V.J.; Gamble, C.; Lees, J.A.; Colas, P. The awakening of the CDK10/Cyclin M protein kinase. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 50174–50186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorns, E.; Turner, N.C.; Elliott, R.; Syed, N.; Garrone, O.; Gasco, M.; Tutt, A.N.; Crook, T.; Lord, C.J.; Ashworth, A. Identification of CDK10 as an important determinant of resistance to endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Cancer Cell 2008, 13, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.Y.; Xu, X.X.; Yu, J.H.; Jiang, G.X.; Yu, Y.; Tai, S.; Wang, Z.D.; Cui, Y.F. Clinical and biological significance of Cdk10 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gene 2012, 498, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Min, S.; Shen, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. CDK16 overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer and regulates cancer cell growth and apoptosis via a p27-dependent mechanism. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagi, T.; Hata, H.; Mizuno, E.; Kitamura, S.; Imafuku, K.; Nakazato, S.; Wang, L.; Nishihara, H.; Tanaka, S.; Shimizu, H. PCTAIRE1/CDK16/PCTK1 is overexpressed in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and regulates p27 stability and cell cycle. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 86, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagi, T.; Matsuzawa, S. PCTAIRE1/PCTK1/CDK16: A new oncotarget? Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 463–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, M.T.; Zhou, J.; Tang, W.; Zeng, X.; Oliver, A.W.; Ward, S.E.; Cheng, A.S. CCRK is a novel signalling hub exploitable in cancer immunotherapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 186, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Yu, Z.; Tian, Y.; Lee, Y.Y.; Li, M.S.; Go, M.Y.; Cheung, Y.S.; Lai, P.B.; Chan, A.M.; To, K.F.; et al. A CCRK-EZH2 epigenetic circuitry drives hepatocarcinogenesis and associates with tumor recurrence and poor survival of patients. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.S.; Cheung, Y.T.; An, X.M.; Chen, Y.C.; Li, M.; Li, G.H.; Cheung, W.; Sze, J.; Lai, L.; Peng, Y.; et al. Cell cycle-related kinase: A novel candidate oncogene in human glioblastoma. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- An, X.; Ng, S.S.; Xie, D.; Zeng, Y.X.; Sze, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.C.; Chow, B.K.; Lu, G.; Poon, W.S.; et al. Functional characterisation of cell cycle-related kinase (CCRK) in colorectal cancer carcinogenesis. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 1752–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.Q.; Xie, D.; Yang, G.F.; Liao, Y.J.; Mai, S.J.; Deng, H.X.; Sze, J.; Guan, X.Y.; Zeng, Y.X.; Lin, M.C.; et al. Cell cycle-related kinase supports ovarian carcinoma cell proliferation via regulation of cyclin D1 and is a predictor of outcome in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 2631–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Wan, H.; Tan, G. Cell cycle-related kinase in carcinogenesis. Oncol. Lett. 2012, 4, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezel, A.F.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Stanger, B.Z.; Bardeesy, N.; Depinho, R.A. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 1218–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, D.P.; Hong, T.S.; Bardeesy, N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2140–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscetti, M.; Morris, J.P.; Mezzadra, R.; Russell, J.; Leibold, J.; Romesser, P.B.; Simon, J.; Kulick, A.; Ho, Y.J.; Fennell, M.; et al. Senescence-Induced Vascular Remodeling Creates Therapeutic Vulnerabilities in Pancreas Cancer. Cell 2020, 181, 424–441.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asghar, U.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; Turner, N.C.; Knudsen, E.S. The history and future of targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyressatre, M.; Prevel, C.; Pellerano, M.; Morris, M.C. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in human cancers: From small molecules to Peptide inhibitors. Cancers 2015, 7, 179–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Martinez, C.; Gelbert, L.M.; Lallena, M.J.; de Dios, A. Cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 3420–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Martin, M.; Rugo, H.S.; Jones, S.; Im, S.A.; Gelmon, K.; Harbeck, N.; Lipatov, O.N.; Walshe, J.M.; Moulder, S.; et al. Palbociclib and Letrozole in Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1925–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laderian, B.; Fojo, T. CDK4/6 Inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in breast cancer: Palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib. Semin. Oncol. 2017, 44, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwapisz, D. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors in hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer: Preliminary results and ongoing studies. Breast Cancer 2018, 25, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Palbociclib: First global approval. Drugs 2015, 75, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Abreu, M.T.; Palafox, M.; Asghar, U.; Rivas, M.A.; Cutts, R.J.; Garcia-Murillas, I.; Pearson, A.; Guzman, M.; Rodriguez, O.; Grueso, J.; et al. Early Adaptation and Acquired Resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibition in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2301–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; DeCristo, M.J.; McAllister, S.S.; Zhao, J.J. CDK4/6 Inhibition in Cancer: Beyond Cell Cycle Arrest. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.E.; Corsino, P.E.; Narayan, S.; Law, B.K. Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitors as Anticancer Therapeutics. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015, 88, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, B.; Finn, R.S.; Turner, N.C. Treating cancer with selective CDK4/6 inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edelman, M.J.; Redman, M.W.; Albain, K.S.; McGary, E.C.; Rafique, N.M.; Petro, D.; Waqar, S.N.; Minichiello, K.; Miao, J.; Papadimitrakopoulou, V.A.; et al. SWOG S1400C (NCT02154490)-A Phase II Study of Palbociclib for Previously Treated Cell Cycle Gene Alteration-Positive Patients with Stage IV Squamous Cell Lung Cancer (Lung-MAP Substudy). J. Thorac. Oncol. 2019, 14, 1853–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schettini, F.; De Santo, I.; Rea, C.G.; De Placido, P.; Formisano, L.; Giuliano, M.; Arpino, G.; De Laurentiis, M.; Puglisi, F.; De Placido, S.; et al. CDK 4/6 Inhibitors as Single Agent in Advanced Solid Tumors. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.J.; Wedam, S.; Amiri-Kordestani, L.; Bloomquist, E.; Tang, S.; Sridhara, R.; Chen, W.; Palmby, T.R.; Fourie Zirkelbach, J.; Fu, W.; et al. FDA Approval of Palbociclib in Combination with Fulvestrant for the Treatment of Hormone Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4968–4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherr, C.J.; Beach, D.; Shapiro, G.I. Targeting CDK4 and CDK6: From Discovery to Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; An, H.J.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, S.A.; Kim, S.; Lim, S.M.; Kim, G.M.; Sohn, J.; Moon, Y.W. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors in breast cancer: A review. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscetti, M.; Leibold, J.; Bott, M.J.; Fennell, M.; Kulick, A.; Salgado, N.R.; Chen, C.C.; Ho, Y.J.; Sanchez-Rivera, F.J.; Fencht, J.; et al. NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity contributes to tumor control. by a cytostatic drug combination. Science 2018, 362, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, H.M.; Shotton, C.F.; Kokkinos, M.I.; Thomas, H. The effects of the CDK inhibitor seliciclib alone or in combination with cisplatin in human uterine sarcoma cell lines. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohberger, B.; Leithner, A.; Stuendl, N.; Kaltenegger, H.; Kullich, W.; Steinecker-Frohnwieser, B. Diacerein retards cell growth of chondrosarcoma cells at the G2/M cell cycle checkpoInt. via cyclin B1/CDK1 and CDK2 downregulation. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Wang, S.; Zeng, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, T. Therapeutic effect of palbociclib in chondrosarcoma: Implication of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 as a potential target. Cell Commun. Signal. 2019, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luke, J.J.; D’Adamo, D.R.; Dickson, M.A.; Keohan, M.L.; Carvajal, R.D.; Maki, R.G.; de Stanchina, E.; Musi, E.; Singer, S.; Schwartz, G.K. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol. potentiates doxorubicin efficacy in advanced sarcomas: Preclinical investigations and results of a phase I dose-escalation clinical trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 2638–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.M.; Alexander, A.; Liu, Y.; Vijayaraghavan, S.; Low, K.H.; Yang, D.; Bui, T.; Somaiah, N.; Ravi, V.; Keyomarsi, K.; et al. CDK4/6 Inhibitors Sensitize Rb-positive Sarcoma Cells to Wee1 Kinase Inhibition through Reversible Cell-Cycle Arrest. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1751–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniguez, A.B.; Stolte, B.; Wang, E.J.; Conway, A.S.; Alexe, G.; Dharia, N.V.; Kwiatkowski, N.; Zhang, T.; Abraham, B.J.; Mora, J.; et al. EWS/FLI Confers Tumor Cell Synthetic Lethality to CDK12 Inhibition in Ewing Sarcoma. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 202–216.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laroche-Clary, A.; Chaire, V.; Algeo, M.P.; Derieppe, M.A.; Loarer, F.L.; Italiano, A. Combined targeting of MDM2 and CDK4 is synergistic in dedifferentiated liposarcomas. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.K.; Taylor, S.; Gupte, A.; Sharp, P.P.; Walia, M.; Walsh, N.C.; Zannettino, A.C.; Chalk, A.M.; Burns, C.J.; Walkley, C.R. BET inhibitors induce apoptosis through a MYC independent mechanism and synergise with CDK inhibitors to kill osteosarcoma cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, T.; Sugisawa, N.; Miyake, K.; Oshiro, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Hayashi, K.; Kimura, H.; Miwa, S.; Igarashi, K.; Chawla, S.P.; et al. Sorafenib and Palbociclib Combination Regresses a Cisplatinum-resistant Osteosarcoma in a PDOX Mouse Model. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 4079–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenther, L.M.; Dharia, N.V.; Ross, L.; Conway, A.; Robichaud, A.L.; Catlett, J.L., 2nd; Wechsler, C.S.; Frank, E.S.; Goodale, A.; Church, A.J.; et al. A Combination CDK4/6 and IGF1R Inhibitor Strategy for Ewing Sarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 1343–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarts, M.; Sharpe, R.; Garcia-Murillas, I.; Gevensleben, H.; Hurd, M.S.; Shumway, S.D.; Toniatti, C.; Ashworth, A.; Turner, N.C. Forced mitotic entry of S-phase cells as a therapeutic strategy induced by inhibition of WEE1. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreahling, J.M.; Foroutan, P.; Reed, D.; Martinez, G.; Razabdouski, T.; Bui, M.M.; Raghavan, M.; Letson, D.; Gillies, R.J.; Altiok, S. Wee1 inhibition by MK-1775 leads to tumor inhibition and enhances efficacy of gemcitabine in human sarcomas. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenhafer, S.L.; Goss, K.L.; Terry, W.W.; Gordon, D.J. Inhibition of the ATR-CHK1 Pathway in Ewing Sarcoma Cells Causes DNA Damage and Apoptosis via the CDK2-Mediated Degradation of RRM2. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, J.; Cidre-Aranaz, F.; Aynaud, M.M.; Orth, M.F.; Knott, M.M.L.; Mirabeau, O.; Mazor, G.; Varon, M.; Holting, T.L.B.; Grossetete, S.; et al. Cooperation of cancer drivers with regulatory germline variants shapes clinical outcomes. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickson, M.A.; Schwartz, G.K.; Keohan, M.L.; D’Angelo, S.P.; Gounder, M.M.; Chi, P.; Antonescu, C.R.; Landa, J.; Qin, L.X.; Crago, A.M.; et al. Progression-Free Survival Among Patients With Well-Differentiated or Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma Treated With CDK4 Inhibitor Palbociclib: A Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, K.; Cost, C.; Davis, I.; Glade-Bender, J.; Grohar, P.; Houghton, P.; Isakoff, M.; Stewart, E.; Laack, N.; Yustein, J.; et al. Emerging novel agents for patients with advanced Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) New Agents for Ewing Sarcoma Task Force. F1000Res 2019, 8, F1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassl, A.; Sicinski, P. Chemotherapy and CDK4/6 Inhibition in Cancer Treatment: Timing Is Everything. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honoki, K.; Yoshitani, K.; Tsujiuchi, T.; Mori, T.; Tsutsumi, M.; Morishita, T.; Takakura, Y.; Mii, Y. Growth inhibition and induction of apoptosis by flavopiridol. in rat lung adenocarcinoma, osteosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma cell lines. Oncol. Rep. 2004, 11, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Li, X.; Okada, T.; Nakamura, T.; Takasaki, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Oda, Y.; Tsuneyoshi, M.; Iwamoto, Y. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, flavopiridol, induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth in drug-resistant osteosarcoma and Ewing’s family tumor cells. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.; Munoz-Galvan, S.; Jimenez-Garcia, M.P.; Marin, J.J.; Carnero, A. Efficacy of CDK4 inhibition against sarcomas depends on their levels of CDK4 and p16ink4 mRNA. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 40557–40574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolte, B.; Iniguez, A.B.; Dharia, N.V.; Robichaud, A.L.; Conway, A.S.; Morgan, A.M.; Alexe, G.; Schauer, N.J.; Liu, X.; Bird, G.H.; et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 screen identifies druggable dependencies in TP53 wild-type Ewing sarcoma. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 2137–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Sicinska, E.; Czaplinski, J.T.; Remillard, S.P.; Moss, S.; Wang, Y.; Brain, C.; Loo, A.; Snyder, E.L.; Demetri, G.D.; et al. Antiproliferative effects of CDK4/6 inhibition in CDK4-amplified human liposarcoma in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2014, 13, 2184–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanich, M.E.; Sun, W.; Hewitt, S.M.; Abdullaev, Z.; Pack, S.D.; Barr, F.G. CDK4 Amplification Reduces Sensitivity to CDK4/6 Inhibition in Fusion-Positive Rhabdomyosarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4947–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, W.; Ma, L.; Chu, B.; Wang, X.; Bui, M.M.; Gemmer, J.; Altiok, S.; Pledger, W.J. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor SCH 727965 (dinacliclib) induces the apoptosis of osteosarcoma cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latres, E.; Malumbres, M.; Sotillo, R.; Martin, J.; Ortega, S.; Martin-Caballero, J.; Flores, J.M.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Barbacid, M. Limited overlapping roles of P15(INK4b) and P18(INK4c) cell cycle inhibitors in proliferation and tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 3496–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotillo, R.; Dubus, P.; Martin, J.; de la Cueva, E.; Ortega, S.; Malumbres, M.; Barbacid, M. Wide spectrum of tumors in knock-in mice carrying a Cdk4 protein insensitive to INK4 inhibitors. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 6637–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Protein | Alteration | Sarcoma Subtype |

| RB1 | Retinoblastoma | Deletion, Mutation | UPS [36,38,39], MFS [36,59], PLPS [37,66], LMS [36,37,74], CS [101], OS [116,118], EwS [130], MPNST [82] |

| CDKN2A | p16INK4a and ARF | Deletion, Mutation | UPS [36,40], MFS [36,59], LMS [75], MPNST [36,77,78,79,80,82,133,134,135,136,137,138], CS [101], ARMS [139], OS [116,118], EwS [130] |

| CDKN2B | p15INK4b | Deletion | MFS [36,59], MPNST [36,134,136] |

| CCND1-3 | Cyclin D1-3 | Amplification | MFS [59], LMS [75], CS [101], OS [116,118] |

| CDK4 | CDK4 | Amplification | UPS [40], WD/DDLPS [36,66], SS [100], CS [101], ARMS [111,112], OS [116,118] |

| CDK6 | CDK6 | Amplification | MFS [59,60] |

| MDM2 | Mdm2 | Amplification | UPS [40], MFS [59], WD/DDLPS [36,37,66], CS [101], ARMS [112,139], OS [116,118] |

| TP53 | p53 | Deletion, Mutation | UPS [36,41], MFS [36,59], PLPS [66], CS [101], ARMS [139], OS [116,118], EwS [130], MPNST [36,82], LMS [36,37,76] |

| KRAS | Ras | Amplification Mutation | UPS [47], ARMS [112] |

| NF1 | Neurofibromin | Mutation | UPS [36], MFS [36,63], MPNST [36,77,78,79,80,82], ARMS [112,139] |

| ATRX | ATRX chromatin remodeler | Mutation | UPS [36], MFS [36], LPS [36] |

| TLS | Translocated in liposarcoma | translocation, (12;16) | M/RCLPS [66] |

| CHOP | C/EBP homologous protein | ||

| MYC | Myc | Amplification | LMS [76], ARMS [111], OS [116,118], MPNST [134] |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | Deletion | LMS [74], OS [116,118], MPNST [80,92] |

| SUZ12 | Suppressor of zeste 12 protein homolog | Mutation | MPNST [78,79,80,82,133] |

| EED | Embryonic ectoderm development | Mutation | MPNST [78,79,80,82,133] |

| SSX | Synovial sarcoma, X | translocation, (X;18) | SS [95] |

| SS18 | Synovial sarcoma translocation, chr18 | ||

| IDH | Isocitrate dehydrogenase | Mutation | CS [102] |

| CDKN1C | p57KIP2 | Deletion | ERMS [104] |

| PAX1 | Paired box 1 | translocation, (2;13) | ARMS [112] |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead box O1 | ||

| BRAF | B-Raf | Mutation | ARMS [112] |

| PIK3CA | p110α | Mutation | ARMS [112] |

| TWIST1 | Twist family bHLH transcription factor 1 | Amplification | OS [116,118] |

| CCNE1 | Cyclin E1 | Amplification | OS [116,118], MPNST [83] |

| EWSR1 | Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 | translocation, (11;22) | EwS [127] |

| FLI1 | Friend leukemia integration 1 |

| Transcriptional CDKs | |||

| CDK | Function | Cancer | Ref |

| CDK7 | Subunit of TFIIH CDK-activating kinase | Hepatocellular carcinoma, breast, and gastric, glioblastoma | [5,151,152,153,154,155] |

| CDK8 | Mediator complex Cyclin H inhibitory phosphorylation Direct interaction with NOTCH, TGF-β, Wnt, and STAT glycolysis | Colorectal, breast, pancreatic, melanoma | [156] |

| CDK9 | Catalytic subunit of P-TEFb | Hematologic, breast, liver, lung, pancreatic, OS, SS | [140,141,142] |

| CDK12 | Ser2 phosphorylation of CTD of RNA pol II RNA splicing Transcriptional termination 3’ end formation DNA damage response and repair | Breast, uterine, bladder | [157,158] |

| CDK13 | Ser2 and Ser5 phosphorylation of CTD of RNA pol II | Hepatocellular carcinoma, colon, breast, gastric, melanoma | [159] |

| CDK19 | Mediator complex | Prostate | [160,161] |

| “Other” CDKs | |||

| CDK | Function | Cancer | Ref |

| CDK5 | Neurite outgrowth and synaptogenesis Reduces insulin secretion RB1 phosphorylation DNA damage repair Cytoskeleton remodeling | Breast, lung, ovarian, prostate, neuroendocrine, multiple myeloma | [7,8,9,162,163,164,165] |

| CDK10 | G2/M transition Promotes ETS2 degradation | Breast, prostate, gastro-intestinal, melanoma, hepatocellular carcinoma | [166,167,168,169] |

| CDK11 | Apoptosis Mitosis Transcription/RNA splicing | Breast, multiple myeloma, colon, cervical, OS, LPS | [6,143,144,145,146] |

| CDK14 | RB1 phosphorylation Wnt activation | Colorectal, OS | [149,150] |

| CDK16 | Neuron outgrowth Spermatogenesis p27 phosphorylation | Non-small cell lung, breast, pancreatic | [170,171,172] |

| CDK20 | G1-S transition Apoptosis Epigenetic control (EZH2-β-catenin-AKT signaling) | Glioma, hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal, lung, ovarian, prostate | [173,174,175,176,177,178] |

| Pre-Clinical Studies | ||||

| Sarcoma | Target | Drug Name | Outcome | Refs |

| UPS OS | Pan-CDK | Flavopiridol | In vitro: growth inhibition, apoptosis | [217] |

| Drug-resistant OS and EwS | In vitro: apoptosis In vivo: tumor growth inhibition | [218] | ||

| LPS | In vivo and Phase I Trial: Enhanced effects of doxorubicin | [203] | ||

| LMS | CDK2, 7, 9 and alkylating agent | Roscovitine + Cisplatin | In vitro: Roscovitine - G1 arrest, minimal apoptosis, decreased CDK2 expression Combo: increased apoptosis | [200] |

| UPS, MPNST, LMS, MFS | CDK4/6 | Palbociclib | In vitro: growth inhibition, senescence In vivo: variable response, dictated by CDK4 levels | [219] |

| OS and STS including LMS | CDK4/6 and WEE1 kinases | Palbociclib + AZD1775 | In vitro: Palbociclib - reversible G1 arrest, but enhanced effects of S-G2 targeted agents | [204] |

| EwS | CDK12 and PARP | THZ531 + PARP inhibitors | THZ531: in vitro and in vivo cell cycle arrest, impaired DNA damage repair Combo: synergized to kill cells and tumors | [205] |

| EwS | CDK4/6 and IGF1R | Ribociclib or Palbociclib + AEW541 | IGF1R induced an acquired resistance to CDK4/6 inhibition Combo: synergistic cell cycle inhibition and non-apoptotic cell death in vitro and in vivo | [209] |

| EwS | USP7, MDM2/MDM4, and Wip1 | P5091, ATSP-7041, and/or GSK2830371 | In vitro: MDM2, MDM4, USP7 and/or PPM1D inhibitors (alone or in combination) - cytotoxic in p53-wild type EwS | [220] |

| LPS | CDK4/6 | Ribociclib | In vitro: G0-G1 arrest In vivo: LPS xenografts – halted tumor growth but acquired resistance | [221] |

| Fusion-positive RMS | CDK4/6 | Ribociclib | In vitro: G1 phase arrest, diminished in tumors overexpressing CDK4 In vivo: slowed tumor growth | [222] |

| SS | CDK9 | LDC000067 | In vitro: decreased cell number and viability, diminished 3D spheroid and colony formation as well as migration | [141] |

| OS | BRD4 + pan-CDK or CDK2 | JQ1 + Flavopiridol or Dinaciclib | JQ1: induced apoptosis in vitro, suppressed in vivo growth Combo: enhanced cell death in vitro | [207] |

| Recurrent OS | RTKs + CDK4/6 | Sorafenib + Palbociclib | Combo: greater PDX tumor inhibition than monotherapy and necrosis | [208] |

| CS | CDK4/6 | Palbociclib | In vitro: decreased cell proliferation, migration, and invasion | [202] |

| CS | IL-1β | Diacerein | In vitro: decreased cell viability and proliferation, caused G2/M arrest with down-regulation of cyclin B1-CDK1 complex and CDK2 expression | [201] |

| OS | CDK2 | Dinaciclib | In vitro: induced apoptosis at low nM concentrations | [223] |

| DDLPS | MDM2 + CDK4/6 | RG7388 + Palbociclib | Combo: greater antitumor effects than monotherapy - in vitro: decreased cell viability, increased apoptosis – in vivo: decreased tumor growth rate and increased PFS | [206] |

| MPNST | CDK4/6 + CDK2 | Palbociclib + Dinaciclib | Combo: low-dose combinations synergized in vitro and inhibited in vivo tumor growth | [84] |

| UPS, MPNST, OS | WEE1 + nucleoside analog | MK-1775 + Gemcitabine | MK-1775: forced entry into mitosis, enhanced effects of gemcitabine In vivo: reduced osteosarcoma growth | [211] |

| EwS | CHK1 + WEE1 | LY2603618 + AZD1775 | In vitro: Combo induced activation of CDK1/2 and apoptosis not observed by either monotherapy | [212] |

| EwS | CDK2 | CVT-313 and NU6140 (also inhibits AURKB) | In vitro: reduced growth In vivo: NU6140 – reduced xenograft growth Both responses dependent on MYBL2 expression | [213] |

| Clinical Trials | ||||

| Sarcoma | Target | Drug Name | Trial and Outcome | Refs |

| Advanced/Metastatic LPS | CDK4/6 | Palbociclib | NCT01209598: Phase 2, completed (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) | [214] |

| Advanced sarcomas with CDK4 overexpression | CDK4/6 | Palbociclib | NCT03242382: Phase 2, recruiting (multicenter trial Spain) | |

| Advanced bone (CS, OS, soft tissue sarcoma except LPS) with CDK pathway alteration | CDK4/6 | Abemaciclib | NCT04040205: Phase 2, recruiting (Medical College of Wisconsin) | |

| Ewing Sarcoma | CDK4/6 + IGF1R | Palbociclib + Ganitumab | NCT04129151: Phase 2, recruiting (Dana Farber Cancer Institute) | |

| RB1 Positive Advanced Solid Tumors (including RMS and EwS) | CDK4/6 | Palbociclib | NCT03526250: Phase 2, recruiting (National Cancer Institute) | |

| Recurrent/Refractory Solid Tumors (including EwS and RMS) in children | CDK4/6 + chemotherapy | Palbociclib + Temozolomide + Irinotecan | NCT03709680: Phase 1, recruiting (Pfizer) | |

| Advanced Solid Tumors | CDK4/6 + chemotherapy | Palbociclib + Cisplatin or Carboplatin | NCT02897375: Phase 1, recruiting (Emory University) | |

| Dedifferentiated LPS | CDK4/6 | Abemaciclib | NCT02846987: Phase 2, recruiting (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) | |

| Advanced/Metastatic Solid Tumors | Notch + CDK4/6 | LY3039478 + Abemaciclib | NCT02784795: Phase 1, active (Eli Lilly and Company) | |

| Metastatic or Advanced, Unresectable STS | CDK4/6 + chemotherapy | Ribociclib + Doxorubicin | NCT03009201: Phase 1, not yet recruiting (OHSU Knight Cancer Institute) | |

| Advanced DDLPS and LMS | CDK4/6 + mTOR | Ribociclib + Everolimus | NCT03114527: Phase 2, recruiting (Fox Chase Cancer Center) | |

| Advanced WD/DDLPS | CDK4/6 | Ribociclib | NCT03096912: Phase 2, recruiting (Assaf-Harofeh Medical Center) | |

| LPS | HDM2 + CDK4/6 | HDM201 + Ribociclib | NCT02343172: Phase 1b/2, active (Novartis Pharmaceuticals) | |

| Advanced Solid Tumors with CCNE1 Amplification | WEE1 | Adavosertib | NCT03253679: Phase 2, recruiting (National Cancer Institute) | |

| Solid Tumors with Genetic Alterations in D-type Cyclins or CDK4/6 Amplification | CDK4/6 | Abemaciclib | NCT03310879: Phase 2, recruiting (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) | |

| Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (Refractory to Imatinib and Sunitinib) | CDK4/6 | Palbociclib | NCT01907607: Phase 2, active (Institut Bergonié) | |

| Advanced WD/DDLPS | CDK4/6 | Ribociclib | NCT02571829: Phase 2, unknown status (Hadassah Medical Organization) | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kohlmeyer, J.L.; Gordon, D.J.; Tanas, M.R.; Monga, V.; Dodd, R.D.; Quelle, D.E. CDKs in Sarcoma: Mediators of Disease and Emerging Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21083018

Kohlmeyer JL, Gordon DJ, Tanas MR, Monga V, Dodd RD, Quelle DE. CDKs in Sarcoma: Mediators of Disease and Emerging Therapeutic Targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(8):3018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21083018

Chicago/Turabian StyleKohlmeyer, Jordan L, David J Gordon, Munir R Tanas, Varun Monga, Rebecca D Dodd, and Dawn E Quelle. 2020. "CDKs in Sarcoma: Mediators of Disease and Emerging Therapeutic Targets" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 8: 3018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21083018

APA StyleKohlmeyer, J. L., Gordon, D. J., Tanas, M. R., Monga, V., Dodd, R. D., & Quelle, D. E. (2020). CDKs in Sarcoma: Mediators of Disease and Emerging Therapeutic Targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(8), 3018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21083018