Molecular Cytogenetic Analysis in Freshwater Prawns of the Genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae)

Abstract

1. Introduction

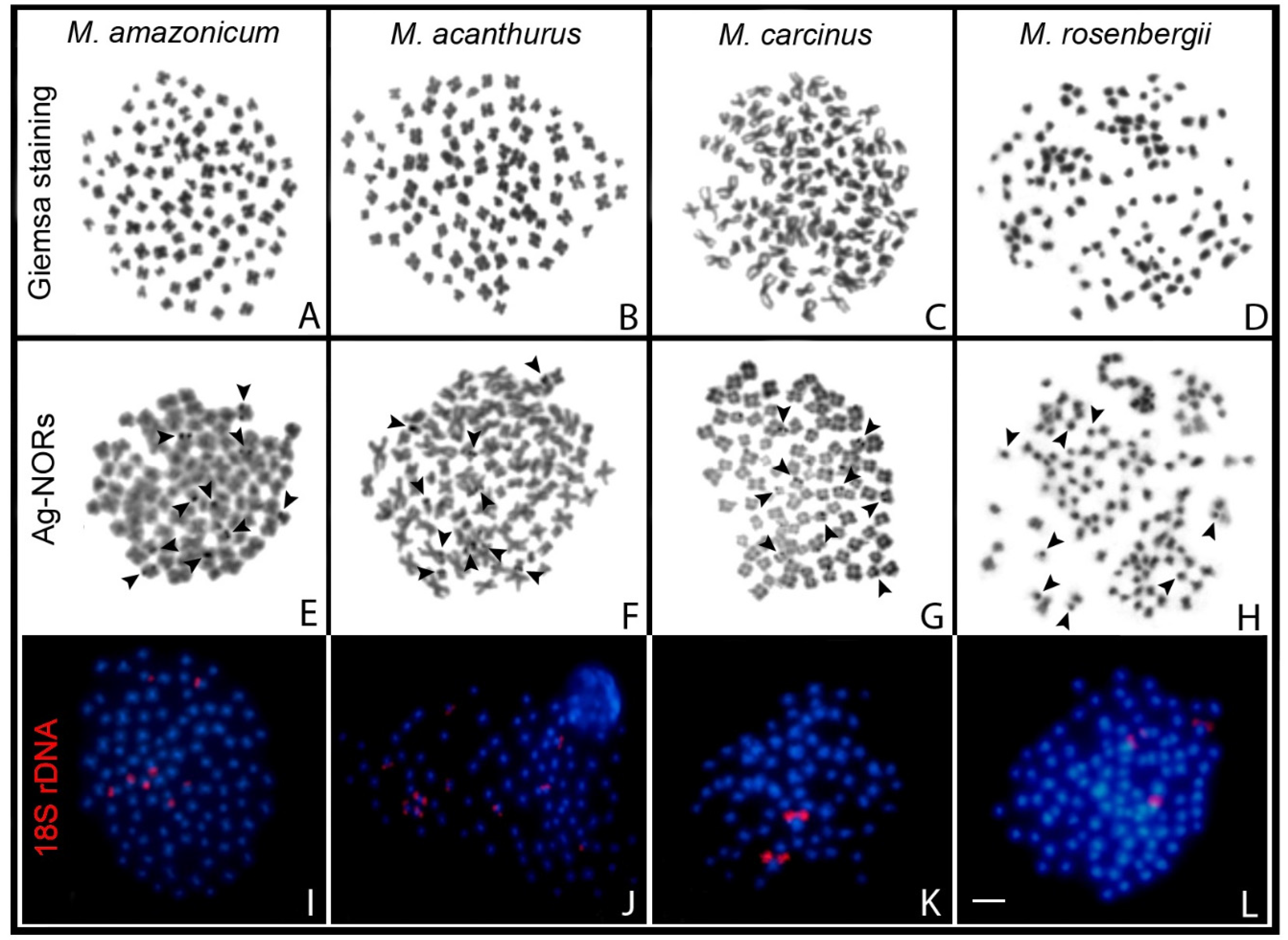

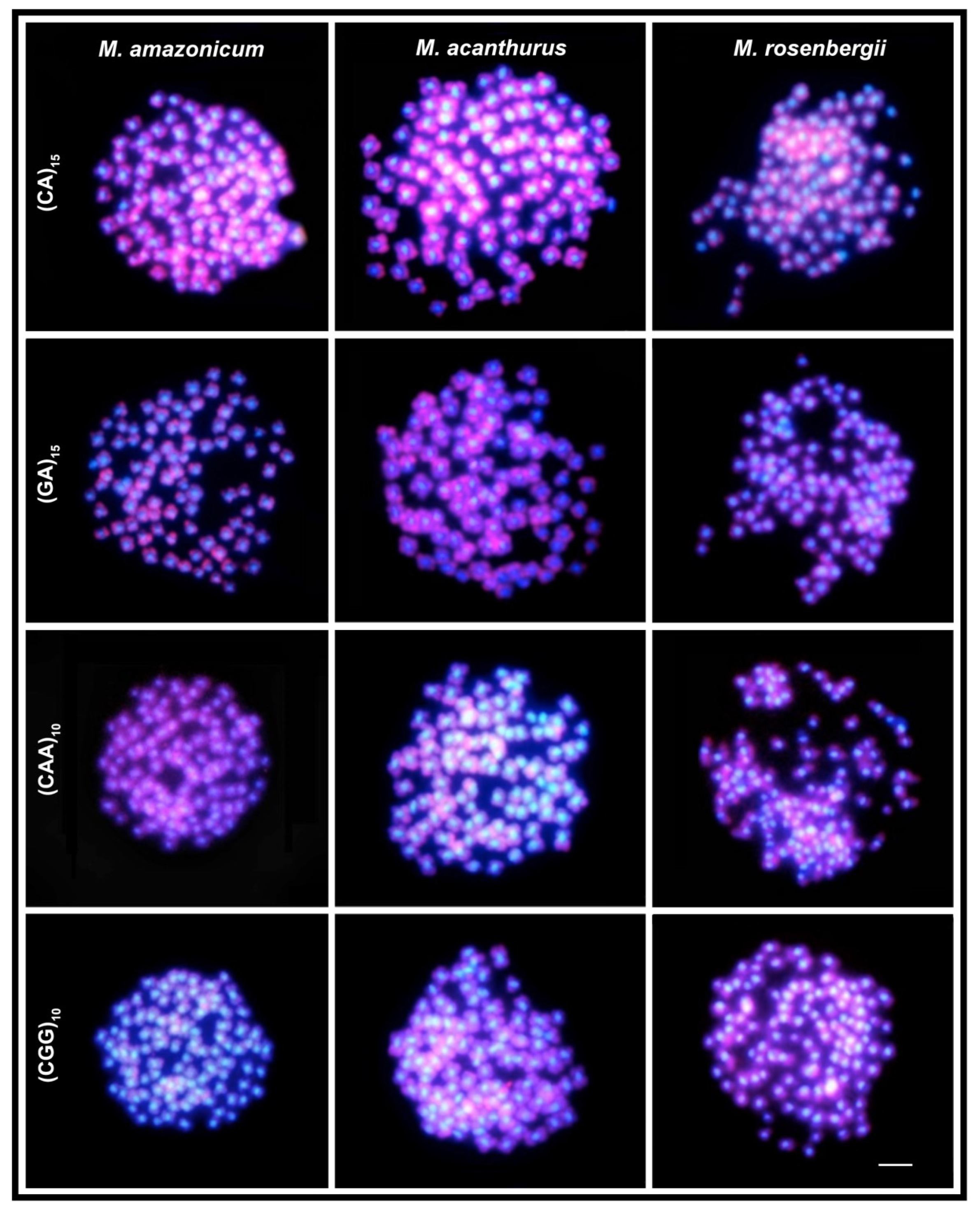

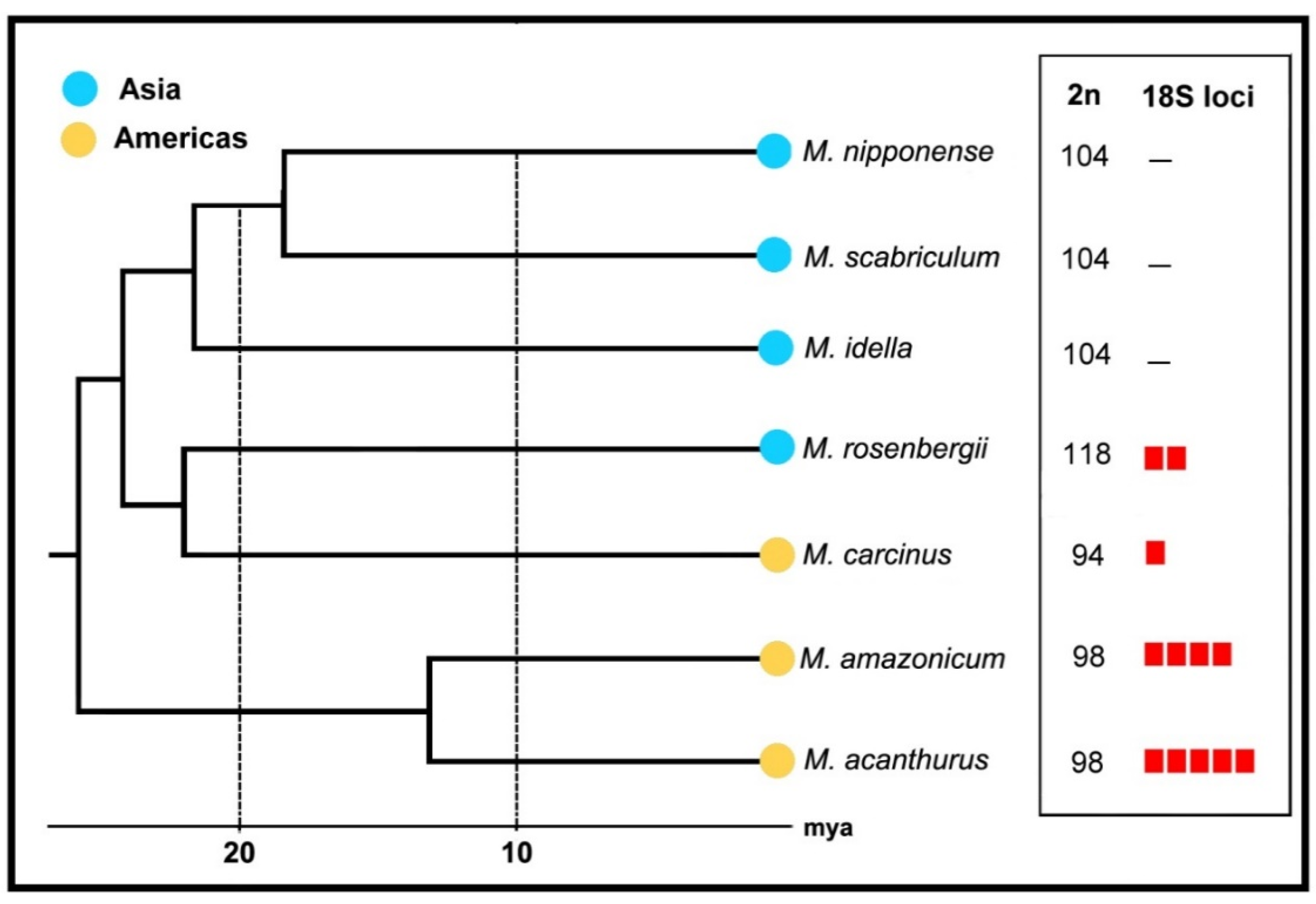

2. Results

3. Discussion

Final Remarks

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Species Analyzed

4.2. Chromosome Preparations

4.3. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hassan, H.; Leitão, A.; Al-Shaikh, I.; AL-Maslamani, I. Karyotype of Palaemon khori (Decapoda: Palaemonidae). Vie et Milieu-Life Environ. 2015, 65, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- De Graves, S.; Pentcheff, N.D.; Ahyong, S.T.; Chan, T.Y.; Crandall, K.A.; Dworschak Peter, C.; Felder Darryl, L.; Feldmann Rodney, M.; Fransen Charles, H.J.M.; Goulding Laura, Y.D.; et al. A classification of living and fossil genera of decapod crustaceans. Raffles Bull. Zool. 2009, 21, 1–109. [Google Scholar]

- WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register of Marine Species. 2019. Available online: http://www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 19 December 2019).

- Holthuis, L.B. FAO species catalogue, Vol. 1. Shrimps and prawns of the world, FAO Fisheries Synopsis No. 125. Food Agric. Organ. United Nations 1980, 1, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Jayachandran, K.V. Palaemonid Prawns: Biodiversity, Taxonomy, Biology and Management, 1st ed.; Science Publishers: Enfield, UK, 2001; p. 624. [Google Scholar]

- Short, J.W. A revision of Australian river prawns, Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae). Hydrobiologia 2004, 525, 1–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anger, K. Neotropical Macrobrachium (Caridea: Palaemonidae): On the biology, origin, and radiation of freshwater-invading shrimp. J. Crustacean. Biol. 2013, 33, 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holthuis, L.B. The Caridean Crustacea of tropical West Africa. Atl. Rep. 1951, 2, 7–187. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, G.A.S. Famílias Atyidae, Palaemonidae e Sergestidae. In Manual de Identificação dos Crustacea Decapoda de água doce do Brasil, 1st ed.; Melo, G.A.S., Ed.; Loyola: São Paulo, Brazil, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 289–415. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, R.S.; Vieira, R.R.R.; D’Incao, F. The marine and estuarine shrimps of the Palaemoninae (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea) from Brazil. Zootaxa 2010, 2606, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, N.; Mantelatto, F.L. Molecular analysis of the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium olfersii (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) supports the existence of a single species throughout its distribution. PloS ONE 2013, 8, e54698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Guerrero, M.U.; Becerril-Morales, F.; Vega-Villasante, F.; Espinosa-Chaurand, L.D. Los langostinos del género Macrobrachium con importancia económica y pesquera en América Latina: Conocimiento actual, rol ecológico y conservación. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2013, 41, 651–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong-Carrillo, O.; Vega-Villasante, F.; Arencibia-Jorge, R.; Akintola, S.L.; Michán-Aguirre, L.; Cupul-Magaña, F.G. Research on the river shrimps of the genus Macrobrachium (Bate, 1868) (Decapoda: Caridea: Palaemonidae) with known or potential economic importance: Strengths and weaknesses shown through scientometrics. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2015, 43, 684–690. [Google Scholar]

- Damrongphol, P.; Eangchuan, N.; Poolsanguan, B. Spawning cycle and oocyte maturation in laboratory-maintained giant freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium rosenbergii). Aquaculture 1991, 95, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, C.C.; Murofushi, M.; Aida, K.; Hanyu, I. Karyological studies on the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Aquaculture 1991, 97, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, J.; Shen, X.; Cai, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Yan, B.; Chu, K.H. The first mitochondrial genome of Macrobrachium rosenbergii from China: Phylogeny and gene rearrangement within Caridea. Mitochondrial Dna Part B 2019, 4, 134–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasookhush, P.; Hindmarch, C.; Sithigorngul, P.; Longyant, S.; Bendena, W.G.; Chaivisuthangkur, P. Transcriptomic analysis of Macrobrachium rosenbergii (giant fresh water prawn) post-larvae in response to M. rosenbergii nodavirus (MrNV) infection: De novo assembly and functional annotation. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutty, M.N.; Herman, F.; Menn, H.L. Culture of others species. In Freshwater Prawn Farming: The Farming of Macrobrachium rosenbergii, 1st ed.; New, M.B., Valenti, W.C., Eds.; Blackwell Science: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Database on Introductions of Aquatic Species (DIAS). Available online: http://www.fao.org/fishery/dias/en (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Barros, M.P.; Silva, L.M.A. Registro de introdução da espécie exótica Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man, 1879) (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae), em águas do estado do Pará, Brasil. Bol. Mus. Para Emílio. Goeldisér Zool. 1997, 13, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Cintra, I.H.A.; Silva, K.C.A.; Muniz, A.P.M. Ocorrência de Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man, 1879) em áreas estuarinas do Estado do Pará (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae). Bol. Técnico. Científico. Cepnor. 2003, 3, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Iketani, G.; Pimentel, L.; Silva-Oliveira, G.; Maciel, C.; Valenti, W.; Schneider, H.; Sampaio, I. The history of the introduction of the giant river prawn, Macrobrachium cf. rosenbergii (Decapoda, Palaemonidae), in Brazil: New insights from molecular data. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2011, 34, 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wowor, D.; Muthu, V.; Meier, R.; Balke, M.; Cai, Y.; Ng, P.K.L. Evolution of life history traits in Asian freshwater prawns of the genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae) based on multilocus molecular phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2009, 52, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Hayd, L.; Anger, K. A new species of Macrobrachium Spence Bate, 1868 (Decapoda, Palaemonidae), M. pantanalense, from the Pantanal, Brazil. Zootaxa 2013, 3700, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Vidthayanon, C. Macrobrachium spelaeus, a new species of stygobitic freshwater prawn from Thailand (Decapoda: Palaemonidae). Raffles B Zool. 2016, 64, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.-Z.; Chen, W.-J.; Guo, Z.-L. The genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea, Caridea, Palaemonidae) with the description of a new species from the Zaomu Mountain Forest Park, Guangdong Province, China. ZooKeys 2019, 866, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holthuis, L.B. Subfamily Palaemoninae. The Palaemonidae collected by the Siboga and Snellius expeditions with remarks on other species. 1. The Decapoda of the Siboga Expedition Part 10. Siboga Exped. 1950, 39, 1–268. [Google Scholar]

- Holthuis, L.B. The subfamily Palaemoninae. A general revision of the Palaemonidae (Crustacea Decapoda Natantia) of the Americas. 2. Allan Hancock Found. Publ. Occas. Pap. 1952, 12, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.Y.; Cai, Y.X.; Tzeng, C.S. Molecular systematics of the freshwater prawn genus Macrobrachium Bate, 1868 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae) inferred from mtDNA sequences, with emphasis on East Asian species. Zool. Stud. 2007, 46, 272–289. [Google Scholar]

- Pileggi, L.G.; Mantelatto, F.L. Taxonomic revision of doubtful Brazilian freshwater shrimp species of genus Macrobrachium (Decapoda, Palaemonidae). Iheringia. Sér. Zool. 2013, 102, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Tizón, A.M.; Rojo, V.; Menini, E.; Torrecilla, Z.; Martínez-Lage, A. Karyological analysis of the shrimp Palaemon serratus (Decapoda: Palaemonidae). J. Crustacean. Biol. 2013, 33, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phimphan, S.; Tanomtong, A.; Seangphan, N.; Sangpakdee, W. Chromosome studies on freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium lanchesteri (Decapoda, Palaemonidae) from Thailand. Nucleus 2019, 62, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Naitoh, N.; Yamazaki, F. Chromosome studies on the mitten crabs Eriocheir japonica and E. sinensis. Fish. Sci. 2004, 70, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, N.; Sharma, R.; Asthana, S.; Vyas, P.; Rather, M.A.; Reddy, A.K.; Krishna, G. Development of karyotype and localization of cytogenetic markers in Dimua River prawn, Macrobrachium villosimanus (Tiwari, 1949). J. Biol. Sci. 2013, 13, 507–513. [Google Scholar]

- Vishnoi, D.N. Studies on the chromosomes of some Indian Crustacea. Cytologia 1972, 37, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qiu, G.; Du, N.; Lai, W. Chromosomal and karyological studies on the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium nipponense (Crustacea, Decapoda). Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 1994, 25, 493–498. [Google Scholar]

- Lakra, W.S.; Kumar, P. Studies on the chromosomes of two freshwater prawns, Macrobrachium idella and M. scabriculum (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae). Cytobios 1995, 84, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, O.P.; Dhall, U. Chromosome studies in three species of freshwater decapods (Crustacea). Cytologia 1971, 36, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gaofeng, Q. Studies on chromosomes of Macrobrachium superbum Heller (Crustacea, Decapoda). J. Fish. Sci. China 1997, 1997, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhou, Q.; Lan, W. Chromosome karyotype in freshwater prawn Exopalaemon modestus. Fish. Sci. 2008, 9, 013. [Google Scholar]

- Torrecilla, Z.; Martínez-Lage, A.; Perina, A.; González-Ortegón, E.; González-Tizón, A.M. Comparative cytogenetic analysis of marine Palaemon species reveals a X1X1X2X2/X1X2Y sex chromosome system in Palaemon elegans. Front. Zool. 2017, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakra, W.S.; Kumar, P.; Das, M.; Goswami, U.M. Improved techniques of chromosome preparation from shrimp and prawns. Asian Fish. Sci. 1997, 10, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Trentini, M.; Corni, M.G.; Froglia, C. The chromosomes of Liocarcinus vernalis (Risso, 1816) and Liocarcinus depurator (L.; 1758) (Decapoda, Brachyura, Portunidae). Biol. Zent. Bl. 1989, 108, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Niiyama, H. A comparative study of the chromosomes in decapods, isopods and amphipods, with some remarks on cytotaxonomy and sex determination in the Crustacea. Fac. Fish. Sci. Hokkaido Univ. 1959, 7, 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lécher, P.; Defaye, D.; Noel, P. Chromosomes and nuclear DNA of Crustacea. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 1995, 27, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, L.J. Population genetics of penaeid shrimp from the Gulf of Mexico. J. Hered. 1979, 70, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, J.A.H. Population genetic structure in penaeid prawns. Aquac. Res. 2000, 31, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Ramos, R. Chromosome studies on the marine shrimps Penaeus vannamei and P. californiensis (Decapoda). J. Crustacean. Biol. 1997, 17, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Xiang, J. Studies on the chromosome of marine shrimps with special reference to different techniques. In Proceedings of the Abstracts of Plant, Animal and Microbe Genomes X Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 January 2002; p. 642. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.-C.; Shih, C.-H.; Chu, T.-J.; Lee, Y.-C.; Tzeng, T.-D. Phylogeography and genetic structure of the oriental river prawn Macrobrachium nipponense (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae) in East Asia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingyun, Y.; Xinping, Z.; Jianhui, L.; Jiajia, F.; Chen, C. Analysis of genetic structure of wild and cultured giant freshwater prawn (Macrobrachium rosenbergii) using newly developed microsatellite. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 323. [Google Scholar]

- Motta-Neto, C.C.; Cioffi, M.B.; Costa, G.W.W.F.; Amorim, K.D.J.; Bertollo, L.A.C.; Artoni, R.F.; Molina, W.F. Overview on karyotype stasis in Atlantic grunts (Eupercaria, Haemulidae) and the evolutionary extensions for other marine fish groups. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Silva, A.L.; Carvalho, F.L.; Mantelatto, F.L. Distribution and genetic differentiation of Macrobrachium jelskii (Miers, 1877) (Natantia: Palaemonidae) in Brazil reveal evidence of non-natural introduction and cryptic allopatric speciation. J. Crustacean. Biol. 2016, 36, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.-T.; Tsai, C.; Tzeng, W.-N. Freshwater prawns (Macrobrachium Bate, 1868) of Taiwan with special references to their biogeographical origins and dispersion routes. J. Crustacean. Biol. 2009, 29, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, D.; Harikrishnan, M. Evolutionary history of genus Macrobrachium inferred from mitochondrial markers: A molecular clock approach. Mitochondrial Dna Part A 2018, 30, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochorová, J.; Garcia, S.; Gálvez, F.; Symonová, R.; Kovařík, A. Evolutionary trends in animal ribosomal DNA loci: Introduction to a new online database. Chromosoma 2018, 127, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summer, A.T. Banding with nucleases. In Chromosome banding, 1st ed.; Summer, A.T., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 1, pp. 253–271. [Google Scholar]

- Coluccia, E.; Deiana, A.M.; Cannas, R.; Salvadori, S. Study of the nucleolar organizer regions in Palinurus elephas (Crustacea: Decapoda). Hydrobiologia 2006, 557, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, S.; Coluccia, E.; Deidda, F.; Cau, A.; Cannas, R.; Deiana, A.M. Comparative cytogenetics in four species of Palinuridae: B chromosomes, ribosomal genes and telomeric sequences. Genetica 2012, 140, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mais, C.; Wright, J.E.; Prieto, J.L.; Raggett, S.L.; McStay, B. UBF-binding site arrays form pseudo-NORs and sequester the RNA polymerase I transcription machinery. Genes. Dev. 2004, 1, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto, J.L.; McStay, B. Pseudo-NORs: A novel model for studying nucleoli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1783, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlinarec, J.; Mczic, M.; Pavlica, M.; Srut, M.; Klobucar, G.; Maguire, I. Comparative karyotype investigations in the European crayfish Astacus astacus and A. leptodactylus (Decapoda, Astacidae). Crustaceana 2011, 84, 1497–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, E.H. Structure and function of telomeres. Nature 1991, 350, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyne, J.; Ratliff, L.R.; Moyzis, R.K. Conservation ofthe human telomere sequence (TTAGGG) among vertebrates. PNAS 1989, 86, 7049–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelliccia, F.; Volpi, E.V.; Lanza, V.; Gaddini, L.; Baldini, A.; Rocchi, A. Telomeric sequences of Asellus aquaticus (Crust. Isop.). Heredity 1994, 72, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, S.; Deidda, F.; Cau, A.; Sabatini, A.; Cannas, R.; Deiana, A.M.; Lobina, C. Karyotype, ribosomal genes, and telomeric sequences in the crayfish Procambarus clarkii (Decapoda: Cambaridae). J. Crustacean. Biol. 2014, 34, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Jamieson, A.J.; Piertney, S.B. Genome size variation in deep-sea amphipods. Roy. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 170862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J.; Liu, C.; Li, F.; Xiang, J. Genome sequences of marine shrimp Exopalaemon carinicauda Holthuis Provide insights into genome size evolution of Caridea. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Huan, P.; Li, F.; Xiang, J.; Huang, C. BAC end sequencing of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei: A glimpse into the genome of Penaeid shrimp. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limn. 2012, 30, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Liang, P. Transposable elements are a significant contributor to tandem repeats in the human genome. Int. J. Genom. 2012, 2012, 947089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemberger, M.O.; Nascimento, V.D.; Coan, R.L.; Ramos, É.L.; Nogaroto, V.; Ziemniczak, K.; Valente, G.T.; Moreira-Filho, O.; Martins, C.; Vicari, M.R. DNA transposon invasion and microsatellite accumulation guide W chromosome differentiation in a Neotropical fish genome. Chromosoma 2019, 128, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, R.; Albach, D.; Ansell, S.; Arntzen, J.W.; Baird, S.J.E.; Bierne, N.; Boughman, J.; Brelsford, A.; Buerkle, C.A.; Buggs, R.; et al. Hybridization and speciation. J. Evol. Biol. 2013, 26, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, J.; Besansky, N.; Hahn, M. How reticulated are species? BioEssays 2016, 38, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokita, S. Larval development of interspecific hybrid between Macrobrachium asperulum from Taiwan and Macrobrachium shokitai from the Ryukyus. Bull. Jap. Soc. Sci. Fish. 1978, 44, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankolli, K.; Shenoy, S.; Jalihal, D.; Almelkar, G. Crossbreeding of the giant freshwater prawns Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man) and M. malcolmsonii (H. Milne Edwards). In Giant Prawn Farming, 1st ed.; New, M.B., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1982; Volume 1, pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Soundarapandian, P.; Kannupandi, T. Larval production by crossbreeding and artificial insemination of freshwater prawns. Indian J. Fish. 2000, 47, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Gong, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xu, P.; Wu, C. Artificial interspecific hybridization between Macrobrachium species. Aquaculture 2004, 232, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, C.; Moreno, C.; Villarroel, E.; Orta, T.; Lodeiros, C.; De Donato, M. Hybridization between the freshwater prawns Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man) and M. carcinus (L). Aquaculture 2003, 217, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misamore, M.; Browdy, C.L. Evaluating hybridization potential between Penaeus setiferus and P. vannamei through natural mating, artificial insemination and in vitro fertilization. Aquaculture 1997, 150, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.L. Natural Hybridization and Evolution, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1997; p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, M.A.; Burke, J.M. Genetic divergence and hybrid speciation. Evolution 2007, 61, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobkin, S.A.; Azzinaro, W.P.; Montfrans Van, J. Culture of Macrobrachium acanthurus and M. carcinus with notes on the selective breeding and hybridization of these shrimps. Proc. Annu. Meeting. World Maric. Soc. 1974, 5, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandifer, P.A.; Smith, T.I.J. A method for artificial insemination of Macrobrachium prawns and its potential use in inheritance and hybridization studies. Proc. World Maric. Soc. 1979, 10, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savaya-Alkalay, A.; Ndao, P.D.; Jouanard, N.; Diane, N.; Aflalo, E.D.; Barki, A.; Sagi, A. Exploitation of reproductive barriers between Macrobrachium species for responsible aquaculture and biocontrol of schistosomiasis in West Africa. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2018, 10, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingerman, A.D.; Bloom, S.E. Rapid chromosome preparation from solid tissue of fishes. J. Fish. Res. Board. Can. 1977, 34, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levan, A.; Fredga, K.; Sandberg, A. Nomenclature for centromeric position on chromosomes. Hereditas 1964, 52, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, W.M.; Black, D.A. Controlled silver-staining of nucleolus organizer regions with a protective colloidal developer a 1-step method. Experientia 1980, 36, 1014–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, 1st ed.; Innis, M., Gelfand, D., Sninsky, J., White, T., Eds.; Academic Press Inc.: Orlando, FL, USA, 1989; Volume 1, pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkel, D.; Straume, T.; Gray, J.W. Cytogenetic analysis using quantitative, high-sensitivity, fluorescence hybridization. PNAS 1986, 83, 2934–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubat, Z.; Hobza, R.; Vyskot, B.; Kejnovsky, E. Microsatellite accumulation on the Y chromosome in Silene latifolia. Genome 2008, 51, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | 2n | Karyotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macrobrachium villosimanus | 124 | 22m+22sm+ 80t/st | [34] |

| M rosenbergii | 118 | 52m+54sm+12st/t | [14] |

| M. rosenbergii | 118 | 90m/sm+28st/t | [15] |

| M. rosenbergii | 118 | 118 m/sm/st | Present study |

| M. lamarrei | 118 | 8m+110t | [35] |

| M. lanchesteri | 116 | 54m+46sm+10a+6t | [32] |

| M. nipponense | 104 | 74m+22t+8st | [36] |

| M. idella | 104 | 50m+24t+30a | [37] |

| M. scabriculum | 104 | 22m+10t+22a+XY | [37] |

| M. siwalikensis | 100 | 100m | [38] |

| M. superbum | 100 | 60m+12sm+28t/st | [39] |

| M. amazonicum | 98 | 98m/sm/st | Present study |

| M. acanthurus | 98 | 98m/sm/st | Present study |

| M. carcinus | 94 | 94m/sm/st | Present study |

| Palaemon khori | 96 | 52m+14sm+24st+6t | [1] |

| P. modestus | 90 | 56m+8sm+12st+14t | [40] |

| P. elegans | 90/89 | 84/85m/sm+6/4a (X1X2Y) | [41] |

| P. serratus | 56 | 4m+12sm+40t | [31] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina, W.F.; Costa, G.W.W.F.; Cunha, I.M.C.; Bertollo, L.A.C.; Ezaz, T.; Liehr, T.; Cioffi, M.B. Molecular Cytogenetic Analysis in Freshwater Prawns of the Genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072599

Molina WF, Costa GWWF, Cunha IMC, Bertollo LAC, Ezaz T, Liehr T, Cioffi MB. Molecular Cytogenetic Analysis in Freshwater Prawns of the Genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(7):2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072599

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina, Wagner F., Gideão W. W. F. Costa, Inailson M. C. Cunha, Luiz A. C. Bertollo, Tariq Ezaz, Thomas Liehr, and Marcelo B. Cioffi. 2020. "Molecular Cytogenetic Analysis in Freshwater Prawns of the Genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 7: 2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072599

APA StyleMolina, W. F., Costa, G. W. W. F., Cunha, I. M. C., Bertollo, L. A. C., Ezaz, T., Liehr, T., & Cioffi, M. B. (2020). Molecular Cytogenetic Analysis in Freshwater Prawns of the Genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea: Decapoda: Palaemonidae). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(7), 2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21072599