Co-Occurrence of Hepatitis A Infection and Chronic Liver Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

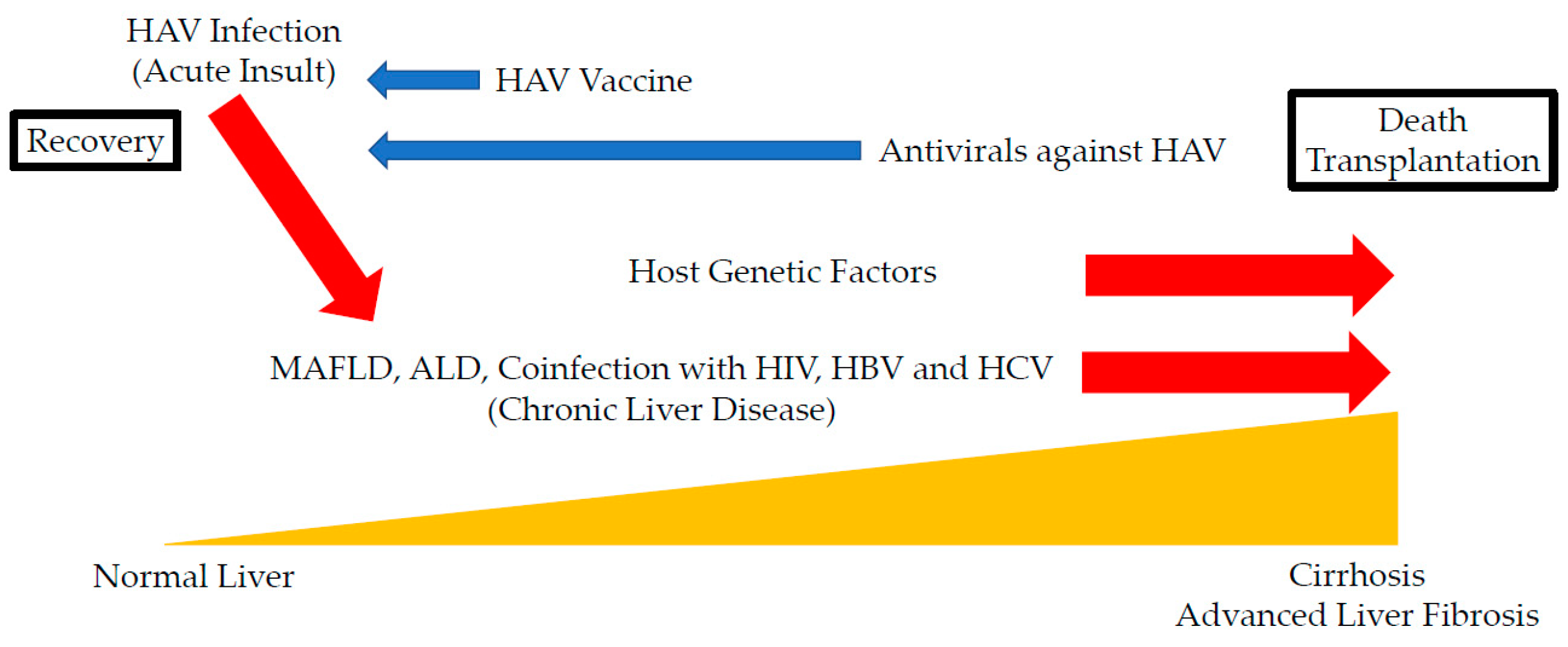

2. Acute-On-Chronic Liver Failure with HAV Infection as an Acute Insult

3. HAV Infection and Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD)

4. HAV Infection and Alcoholic Liver Diseases (ALD)

5. Coinfection of HAV with HIV

6. Coinfection of HAV with HBV

7. Coinfection of HAV with HCV

8. HAV and Other Chronic Liver Diseases

9. Host Genetic Factors in HAV Infection

10. Prevention of HAV Infection in Patients with Chronic Liver Diseases

10.1. HAV Vaccination

10.2. Japanese Rice-Koji Miso Extracts and Zinc Sulfates Could Inhibit HAV Replication with the Enhancement of GRP78 Expression

10.3. Candidates of Antivirals against HAV in Chronic Liver Diseases

10.4. HAV Infection Is Associated with the Activation of the Host Immune System and Severe Systemic Inflammation

10.5. Recent Outbreak of HAV Infection in MSM

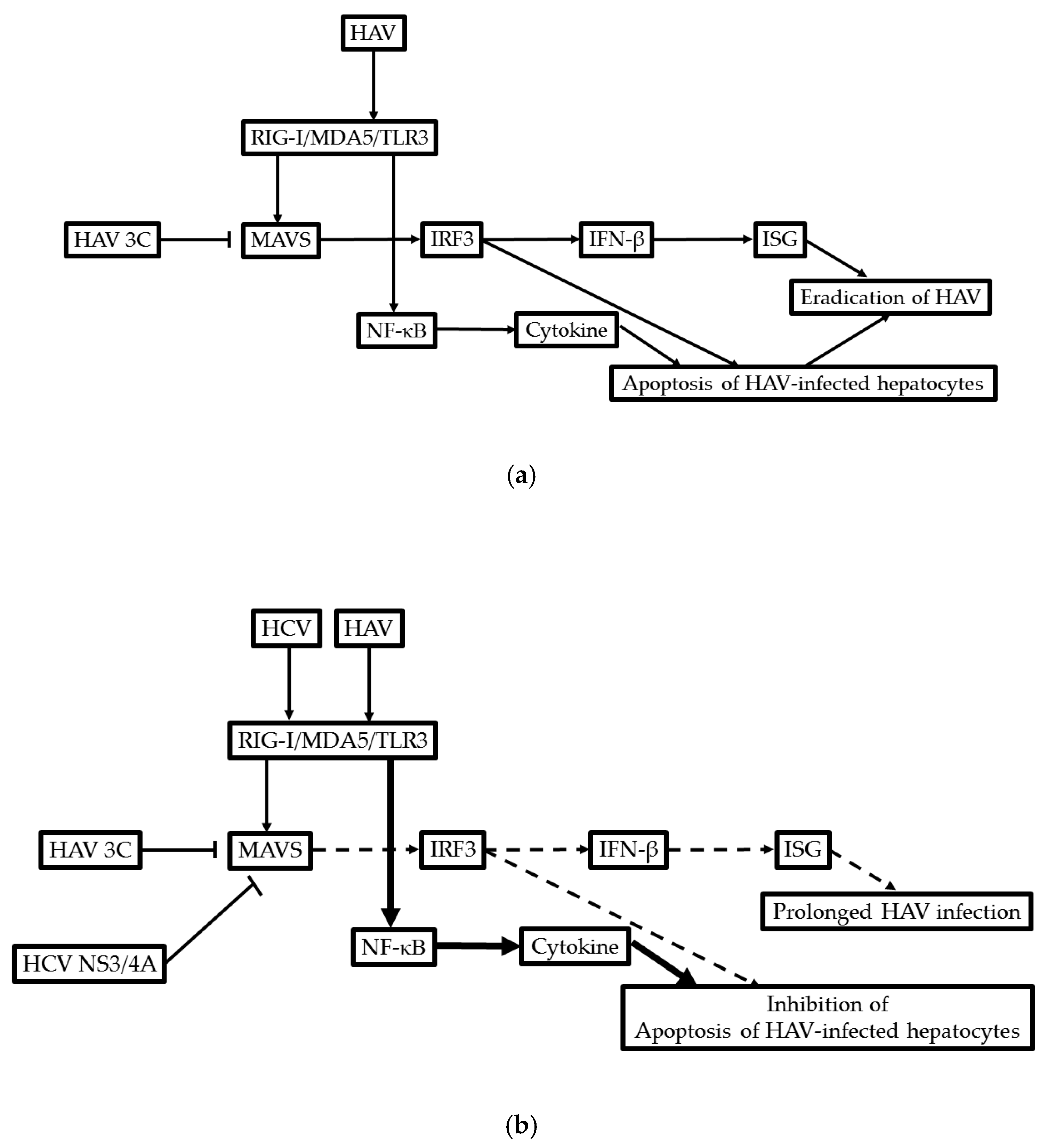

11. Possible Molecular Mechanism of the Development of ACLF in Patients with HAV Infection

12. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HAV | Hepatitis A virus |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| MAFLD | Metabolic associated fatty liver disease |

| ACLF | Acute-on-chronic liver failure |

| NASH | Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| LOHF | Late-onset hepatic failure |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin |

| GRP78 | Glucose-regulated protein 78 |

| ALD | Alcoholic liver disease |

| CMA | Chaperon-mediated autophagy |

References

- Radha Krishna, Y.; Saraswat, V.A.; Das, K.; Himanshu, G.; Yachha, S.K.; Aggarwal, R.; Choudhuri, G. Clinical features and predictors of outcome in acute hepatitis A and hepatitis E virus hepatitis on cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2009, 29, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarin, S.K.; Choudhury, A.; Sharma, M.K.; Maiwall, R.; Al Mahtab, M.; Rahman, S.; Saigal, S.; Saraf, N.; Soin, A.S.; Devarbhavi, H.; et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL): An update. Hepatol. Int. 2019, 13, 353–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Yokosuka, O.; Hiraide, A.; Kojima, H.; Honda, A.; Fukai, K.; Imazeki, F.; Nagao, K.; Saisho, H. Prevalence of obesity in patients with acute hepatitis; is severe obesity a risk factor for fulminant hepatitis in Japan? Hepatogastroenterology 2005, 52, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakao, M.; Nakayama, N.; Uchida, Y.; Tomiya, T.; Ido, A.; Sakaida, I.; Yokosuka, O.; Takikawa, Y.; Inoue, K.; Genda, T.; et al. Nationwide survey for acute liver failure and late-onset hepatic failure in Japan. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 752–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeffe, E.B. Is hepatitis A more severe in patients with chronic hepatitis B and other chronic liver diseases? Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1995, 90, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sainokami, S.; Abe, K.; Ishikawa, K.; Suzuki, K. Influence of load of hepatitis A virus on disease severity and its relationship with clinical manifestations in patients with hepatitis A. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 20, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K.; Nakayama, N.; Kato, N.; Yokosuka, O.; Tsubouchi, H.; Takikawa, H.; Mochida, S.; Intractable Hepato-Biliary Diseases Study Group of Japan. Infectious complications and timing for liver transplantation in autoimmune acute liver failure in Japan: A subanalysis based on nationwide surveys between 2010 and 2015. J. Gastroenterol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, A.; Kanda, T.; Akiike, T.; Komoda, H.; Ito, K.; Abe, A.; Aruga, A.; Kaneda, S.; Saito, M.; Kiyohara, T.; et al. Hepatitis A outbreak associated with a revolving sushi bar in Chiba, Japan: Application of molecular epidemiology. Hepatol. Res. 2012, 42, 828–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vento, S.; Garofano, T.; Renzini, C.; Cainelli, F.; Casali, F.; Ghironzi, G.; Ferraro, T.; Concia, E. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis A virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mele, A.; Tosti, M.E.; Stroffolini, T. Hepatitis associated with hepatitis A superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Nakamoto, S.; Wu, S.; Nakamura, M.; Jiang, X.; Haga, Y.; Sasaki, R.; Yokosuka, O. Direct-acting Antivirals and Host-targeting Agents against the Hepatitis A Virus. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2015, 3, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagadisan, B.; Srivastava, A.; Yachha, S.K.; Poddar, U. Acute on chronic liver disease in children from the developing world: Recognition and prognosis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 54, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singal, A.K.; Kamath, P.S. Acute on chronic liver failure in non-alcoholic fatty liver and alcohol associated liver disease. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 4, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarin, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Almeida, J.A.; Chawla, Y.K.; Fan, S.T.; Garg, H.; de Silva, H.J.; Hamid, S.S.; Jalan, R.; Komolmit, P.; et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL). Hepatol. Int. 2009, 3, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, J.; Thapa, B.R.; Rawal, P.; Ratho, R.K.; Singh, K. Predictors of outcome in acute-on-chronic liver failure in children. Hepatol. Int. 2011, 5, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Saraswat, V.A. Hepatitis E and Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2013, 3, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Rana, B.S.; Mitra, S.; Duseja, A.; Das, A.; Dhiman, R.K.; Chawla, Y. A Case of Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure (ACLF) Due to An Uncommon Acute and Chronic Event. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2018, 8, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axley, P.; Ahmed, Z.; Arora, S.; Haas, A.; Kuo, Y.F.; Kamath, P.S.; Singal, A.K. NASH Is the Most Rapidly Growing Etiology for Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure-Related Hospitalization and Disease Burden in the United States: A Population-Based Study. Liver Transpl. 2019, 25, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, A.; Miller, M.; Gieseler, R.K.; Gerken, G.; Scolaro, M.J.; Canbay, A. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in HIV-positive patients predisposes for acute-on-chronic liver failure: Two cases. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 18, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Yokosuka, O.; Suzuki, Y. Prolonged hepatitis caused by cytomegalovirus and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in 16-year-old obese boy. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2005, 164, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefilliatre, P.; Villeneuve, J.P. Fulminant hepatitis A in patients with chronic liver disease. Can. J. Public Health 2000, 91, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, E.; Genovese, D.; Tosti, M.E.; Mariano, A.; Cuccuini, M.; Proietti, L.; Giuli, C.D.; Lavagna, A.; Crapa, G.E.; Morace, G.; et al. An outbreak of hepatitis A virus infection with a high case-fatality rate among injecting drug users. J. Hepatol. 2005, 43, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J. International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakao, M.; Nakayama, N.; Uchida, Y.; Tomiya, T.; Oketani, M.; Ido, A.; Tsubouchi, H.; Takikawa, H.; Mochida, S. Deteriorated outcome of recent patients with acute liver failure and late-onset hepatic failure caused by infection with hepatitis A virus: A subanalysis of patients seen between 1998 and 2015 and enrolled in nationwide surveys in Japan. Hepatol. Res. 2019, 49, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.K.; Panda, S.K.; Shalimar Acharya, S.K. Patients with Diabetes Mellitus are Prone to Develop Severe Hepatitis and Liver Failure due to Hepatitis Virus Infection. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2013, 3, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Win, N.N.; Kanda, T.; Nakamura, M.; Nakamoto, S.; Okamoto, H.; Yokosuka, O.; Shirasawa, H. Free fatty acids or high-concentration glucose enhances hepatitis A virus replication in association with a reduction in glucose-regulated protein 78 expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 483, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Kanda, T.; Nakamoto, S.; Haga, Y.; Sasaki, R.; Nakamura, M.; Wu, S.; Mikata, R.; Yokosuka, O. Knockdown of glucose-regulated protein 78 enhances poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage in human pancreatic cancer cells exposed to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 32, 2343–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Kanda, T.; Haga, Y.; Sasaki, R.; Nakamura, M.; Wu, S.; Nakamoto, S.; Shirasawa, H.; Okamoto, H.; Yokosuka, O. Glucose-regulated protein 78 is an antiviral against hepatitis A virus replication. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 3305–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, J.G. Fulminant hepatitis in patients with chronic liver disease. J. Viral Hepat. 2000, 7, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, A.; Uchida, T.; Rakela, J. Acute viral hepatitis superimposed on alcoholic liver cirrhosis: Clinical and histopathologic features. Liver 1985, 5, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duseja, A.; Chawla, Y.K.; Dhiman, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Choudhary, N.; Taneja, S. Non-hepatic insults are common acute precipitants in patients with acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF). Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 3188–3192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyosawa, K.; Oofusa, H.; Saitoh, H.; Sodeyama, T.; Tanaka, E.; Furuta, S.; Itoh, S.; Ogata, H.; Kobuchi, H.; Kameko, M.; et al. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis A, B, and D viruses and human T-lymphocyte tropic viruses in Japanese drug abusers. J. Med. Virol. 1989, 29, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Nakano, I.; Katano, Y.; Nagano, K.; Yokozaki, S.; Hayakawa, T.; Toyoda, H.; Takamatsu, J. Infection of hepatitis A virus in Japanese haemophiliacs. J. Infect. 2001, 42, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koibuchi, T.; Koga, M.; Kikuchi, T.; Horikomi, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Lim, L.A.; Adachi, E.; Tsutsumi, T.; Yotsuyanagi, H. Prevalence of Hepatitis a Immunity and Decision-tree Analysis Among Men Who Have Sex With Men and Are Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus in Tokyo. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Kanda, T.; Wu, S.; Imazeki, F.; Yokosuka, O. Hepatitis A, B, C and E virus markers in Chinese residing in Tokyo, Japan. Hepatol. Res. 2012, 42, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, C.; Ko, K.; Nagashima, S.; Harakawa, T.; Fujii, T.; Ohisa, M.; Katayama, K.; Takahashi, K.; Okamoto, H.; Tanaka, J. Very low prevalence of anti-HAV in Japan: High potential for future outbreak. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, M.; Lim, L.A.; Ogishi, M.; Satoh, H.; Kikuchi, T.; Adachi, E.; Sugiyama, R.; Kiyohara, T.; Suzuki, R.; Muramatsu, M.; et al. Comparison of the Clinical Features of Hepatitis A in People Living with HIV between Pandemics in 1999-2000 and 2017-2018 in the Metropolitan Area of Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 73, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akao, T.; Onji, M.; Kawasaki, K.; Uehara, T.; Kuwabara, Y.; Nishimoto, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Miyaike, J.; Oomoto, M.; Miyake, T. Surveillance of Hepatitis Viruses in Several Small Islands of Japan by Ship: A Public Health Approach for Elimination of Hepatitis Viruses by 2030. Euroasian J. Hepatogastroenterol. 2019, 9, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, E.; Giambi, C.; Ialacci, R.; Coppola, R.C.; Zanetti, A.R. Risk groups for hepatitis A virus infection. Vaccine 2003, 21, 2224–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puoti, M.; Moioli, M.C.; Travi, G.; Rossotti, R. The burden of liver disease in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Semin. Liver Dis. 2012, 32, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, M.; Goh, L.; Lamba, H. Increasing hepatitis A IgG prevalence rate in men who have sex with men attending a sexual health clinic in London: Implications for immunization policy. Int. J. STD AIDS 2007, 18, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadlier, C.; O’Rourke, A.; Carr, A.; Bergin, C. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis A, hepatitis B and varicella virus in people living with HIV in Ireland. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 888–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohall, A.; Zucker, J.; Krieger, R.; Scott, C.; Guido, C.; Hakala, S.; Carnevale, C. Missed Opportunities for Hepatitis A Vaccination Among MSM Initiating PrEP. J. Community Health 2020, 45, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa-Mattioli, M.; Allavena, C.; Poirier, A.S.; Billaudel, S.; Raffi, F.; Ferré, V. Prolonged hepatitis A infection in an HIV-1 seropositive patient. J. Med. Virol. 2002, 68, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, Y.; Kimizuka, Y.; Sasaki, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Hamakawa, Y.; Tagami, Y.; Miyata, J.; Hayashi, N.; Fujikura, Y.; Kawana, A. Hepatitis A virus-associated fulminant hepatitis with human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 26, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Sasaki, R.; Masuzaki, R.; Matsumoto, N.; Ogawa, M.; Moriyama, M. Cell Culture Systems and Drug Targets for Hepatitis A Virus Infection. Viruses 2020, 12, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebeejaun, K.; Degala, S.; Balogun, K.; Simms, I.; Woodhall, S.C.; Heinsbroek, E.; Crook, P.D.; Kar-Purkayastha, I.; Treacy, J.; Wedgwood, K.; et al. Outbreak of hepatitis A associated with men who have sex with men (MSM), England, July 2016 to January 2017. Euro. Surveill. 2017, 22, 30454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidl, G.S.; Sonder, G.J.; Bovée, L.P.; Friesema, I.H.; van Rijckevorsel, G.G.; Ruijs, W.L.; van Schie, F.; Siedenburg, E.C.; Yang, J.Y.; Vennema, H. Hepatitis A outbreak among men who have sex with men (MSM) predominantly linked with the EuroPride, the Netherlands, July 2016 to February 2017. Euro. Surveill. 2017, 22, 30468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comelli, A.; Izzo, I.; Casari, S.; Spinetti, A.; Bergamasco, A.; Castelli, F. Hepatitis A outbreak in men who have sex with men (MSM) in Brescia (Northern Italy), July 2016–July 2017. Infez. Med. 2018, 26, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C.Y.; Wu, H.H.; Zou, H.; Lo, Y.C. Epidemiological characteristics and associated factors of acute hepatitis A outbreak among HIV-coinfected men who have sex with men in Taiwan, June 2015–December 2016. J. Viral. Hepat. 2018, 25, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, A.; Meybeck, A.; Alidjinou, K.; Huleux, T.; Viget, N.; Baclet, V.; Valette, M.; Alcaraz, I.; Sauser, E.; Bocket, L.; et al. Clinical and virological features of acute hepatitis A during an ongoing outbreak among men who have sex with men in the North of France. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2019, 95, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Morimoto, N.; Miura, K.; Takaoka, Y.; Nomoto, H.; Tsukui, M.; Isoda, N.; Ohnishi, H.; Nagashima, S.; Takahashi, M.; et al. Full-genome characterization of the RIVM-HAV16-090-like hepatitis A virus strains recovered from Japanese men who have sex with men, with sporadic acute hepatitis A. Hepatol. Res. 2019, 49, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, A.; Rossotti, R.; Moioli, M.C.; Merli, M.; Valsecchi, P.; Zuccaro, V.; Vecchia, M.; Grecchi, C.; Patruno, S.F.A.; Sacchi, P.; et al. The impact of HIV infection and men who have sex with men status on hepatitis A infection: The experience of two tertiary centres in Northern Italy during the 2017 outbreak and in the 2009–2016 period. J. Viral Hepat. 2019, 26, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, M.A.; Hofmeister, M.G.; Kupronis, B.A.; Lin, Y.; Xia, G.L.; Yin, S.; Teshale, E. Increase in Hepatitis A Virus Infections—United States, 2013–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019, 68, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raczyńska, A.; Wickramasuriya, N.N.; Kalinowska-Nowak, A.; Garlicki, A.; Bociąga-Jasik, M. Acute Hepatitis A Outbreak Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in Krakow, Poland; February 2017-February 2018. Am. J. Mens. Health 2019, 13, 1557988319895141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.H.; Tsai, M.S.; Chiang, Y.H.; Shih, C.Y.; Liu, C.Y.; Chuang, Y.C.; Yang, C.J. Effectiveness of hepatitis A vaccination among people living with HIV in Taiwan: Is one dose enough? J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassopoulos, N.; Papaevangelou, G.; Roumeliotou-Karayannis, A.; Kalafatas, P.; Engle, R.; Gerin, J.; Purcell, R.H. Double infections with hepatitis A and B viruses. Liver 1985, 5, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooksley, W.G. What did we learn from the Shanghai hepatitis A epidemic? J. Viral Hepat. 2000, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagnelli, E.; Coppola, N.; Pisaturo, M.; Pisapia, R.; Onofrio, M.; Sagnelli, C.; Catuogno, A.; Scolastico, C.; Piccinino, F.; Filippini, P. Clinical and virological improvement of hepatitis B virus-related or hepatitis C virus-related chronic hepatitis with concomitant hepatitis A virus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 1536–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ke, W.; Xie, J.; Zhao, Z.; Xie, D.; Gao, Z. Comparison of effects of hepatitis E or A viral superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol. Int. 2010, 4, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fu, J.; Gao, D.; Huang, W.; Li, Z.; Jia, B. Clinical analysis of patients suffering from chronic hepatitis B superinfected with other hepadnaviruses. J. Med. Virol. 2016, 88, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisei, C.; Addo, M.M.; Schulze Zur Wiesch, J. Seroconversion of HBsAG coincides with hepatitis A super-infection: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2020, 8, 1651–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pramoolsinsap, C.; Poovorawan, Y.; Hirsch, P.; Busagorn, N.; Attamasirikul, K. Acute, hepatitis-A super-infection in HBV carriers, or chronic liver disease related to HBV or HCV. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1999, 93, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, J.J.Y. Epidemiology of hepatitis A in Asia and experience with the HAV vaccine in Hong Kong. J. Viral Hepat. 2000, 7 (Suppl. 1), 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, S.W.; Sung, J.J. Inactivated hepatitis A vaccine in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 13, 1445–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locarnini, S. A virological perspective on the need for vaccination. J. Viral Hepat. 2000, 7, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, R.; Kodama, Y.; Takamura, N.; Gomi, H. Hepatitis A in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient: Impending risk during the Tokyo Olympic Games in 2020. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, N.; Rao, S.; Kumar, A.; Patil, S.; Rani, S. Hepatitis A vaccination in chronic liver disease: Is it really required in a tropical country like India? Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 25, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.C.; Nagpal, A.K.; Seth, A.K.; Dhot, P.S. Should one vaccinate patients with chronic liver disease for hepatitis A virus in India? J. Assoc. Physicians India 2004, 52, 785–787. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nunen, A.B.; Pontesilli, O.; Uytdehaag, F.; Osterhaus, A.D.; de Man, R.A. Suppression of hepatitis B virus replication mediated by hepatitis A-induced cytokine production. Liver 2001, 21, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berthillon, P.; Crance, J.M.; Leveque, F.; Jouan, A.; Petit, M.A.; Deloince, R.; Trepo, C. Inhibition of the expression of hepatitis A and B viruses (HAV and HBV) proteins by interferon in a human hepatocarcinoma cell line (PLC/PRF/5). J. Hepatol. 1996, 25, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, T.; Tamura, A.; Shibata, T.; Kuroda, K.; Kanda, T.; Sugiyama, M.; Mizokami, M.; Moriyama, M. Analysis of HBV Genomes Integrated into the Genomes of Human Hepatoma PLC/PRF/5 Cells by HBV Sequence Capture-Based Next-Generation Sequencing. Genes 2020, 11, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Win, N.N.; Kanda, T.; Ogawa, M.; Nakamoto, S.; Haga, Y.; Sasaki, R.; Nakamura, M.; Wu, S.; Matsumoto, N.; Matsuoka, S.; et al. Superinfection of hepatitis A virus in hepatocytes infected with hepatitis B virus. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 1366–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Yokosuka, O.; Imazeki, F.; Saisho, H. Acute hepatitis C virus infection, 1986-2001: A rare cause of fulminant hepatitis in Chiba, Japan. Hepatogastroenterology 2004, 51, 556–558. [Google Scholar]

- Villamil, F.G.; Hu, K.Q.; Yu, C.H.; Lee, C.H.; Rojter, S.E.; Podesta, L.G.; Makowka, L.; Geller, S.A.; Vierling, J.M. Detection of hepatitis C virus with RNA polymerase chain reaction in fulminant hepatic failure. Hepatology 1995, 22, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Vento, S. Fulminant hepatitis associated with hepatitis A virus superinfection in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J. Viral Hepat. 2000, 7, 7–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, K.; Tegtmeyer, B.; Cornberg, M.; Hadem, J.; Potthoff, A.; Böker, K.H.; Tillmann, H.L.; Manns, M.P.; Wedemeyer, H. Hepatitis A virus infection suppresses hepatitis C virus replication and may lead to clearance of HCV. J. Hepatol. 2006, 45, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacopardo, B.; Nunnari, G.; Nigro, L. Clearance of HCV RNA following acute hepatitis A superinfection. Dig. Liver Dis. 2009, 41, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser-Nobis, K.; Harak, C.; Schult, P.; Kusov, Y.; Lohmann, V. Novel perspectives for hepatitis A virus therapy revealed by comparative analysis of hepatitis C virus and hepatitis A virus RNA replication. Hepatology 2015, 62, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagnelli, E.; Sagnelli, C.; Pisaturo, M.; Coppola, N. Hepatic flares in chronic hepatitis C: Spontaneous exacerbation vs hepatotropic viruses superinfection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 6707–6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koff, R.S. Risks associated with hepatitis A and hepatitis B in patients with hepatitis C. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2001, 33, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devalle, S.; de Paula, V.S.; de Oliveira, J.M.; Niel, C.; Gaspar, A.M. Hepatitis A virus infection in hepatitis C Brazilian patients. J. Infect. 2003, 47, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, M.; Khaykis, I.; Park, J.; Bini, E.J. Susceptibility to hepatitis A in patients with chronic liver disease due to hepatitis C virus infection: Missed opportunities for vaccination. Hepatology 2005, 42, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, D.B.; Friedman, M.; Borum, M.L. Does the race or gender of hepatitis C infected patients influence physicians’ assessment of hepatitis A and hepatitis B serologic status? South Med. J. 2007, 100, 683–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villar, L.M.; de Melo, M.M.; Calado, I.A.; de Almeida, A.J.; Lampe, E.; Gaspar, A.M. Should Brazilian patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection be vaccinated against hepatitis A virus? J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 24, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buxton, J.A.; Kim, J.H. Hepatitis A and hepatitis B vaccination responses in persons with chronic hepatitis C infections: A review of the evidence and current recommendations. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 19, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, J.R.; Hachem, C.Y.; Kanwal, F.; Mei, M.; El-Serag, H.B. Meeting vaccination quality measures for hepatitis A and B virus in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Hepatology 2011, 53, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, I.A.; Parker, R.; Armstrong, M.J.; Houlihan, D.D.; Mutimer, D.J. Hepatitis A virus vaccination in persons with hepatitis C virus infection: Consequences of quality measure implementation. Hepatology 2012, 56, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, S.K.; Kedarisetty, C.K.; Abbas, Z.; Amarapurkar, D.; Bihari, C.; Chan, A.C.; Chawla, Y.K.; Dokmeci, A.K.; Garg, H.; Ghazinyan, H.; et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) 2014. Hepatol. Int. 2014, 8, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, V.; Moreau, R.; Jalan, R.; Ginès, P. EASL-CLIF Consortium CANONIC Study. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: A new syndrome that will re-classify cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S131–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, J.G.; Reddy, K.R.; Garcia-Tsao, G.; Biggins, S.W.; Wong, F.; Fallon, M.B.; Subramanian, R.M.; Kamath, P.S.; Thuluvath, P.; Vargas, H.E.; et al. NACSELD acute-on-chronic liver failure (NACSELD-ACLF) score predicts 30-day survival in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2018, 67, 2367–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yesupriya, A.; Hu, D.J.; Chang, M.H.; Dowling, N.F.; Ned, R.M.; Udhayakumar, V.; Lindegren, M.L.; Khudyakov, Y. Variants in ABCB1, TGFB1, and XRCC1 genes and susceptibility to viral hepatitis A infection in Mexican Americans. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1008–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, P.; Deka, M.; Medhi, S.; Dutta, S.; Kashyap, K.; Kumari, N. Association of Toll-like receptor 4 with hepatitis A virus infection in Assam. Acta. Virol. 2018, 62, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubicz, R.; Yolken, R.; Drigalenko, E.; Carless, M.A.; Dyer, T.D.; Kent, J., Jr.; Curran, J.E.; Johnson, M.P.; Cole, S.A.; Fowler, S.P.; et al. Genome-wide genetic investigation of serological measures of common infections. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 23, 1544–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundekar, S.; Thorat, N.; Gurav, Y.; Lole, K. Viral excretion and antibody titers in children infected with hepatitis A virus from an orphanage in western India. J. Clin. Virol. 2015, 73, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brouwer, A.F.; Zelner, J.L.; Eisenberg, M.C.; Kimmins, L.; Ladisky, M.; Collins, J.; Eisenberg, J.N.S. The Impact of Vaccination Efforts on the Spatiotemporal Patterns of the Hepatitis A Outbreak in Michigan, 2016-2018. Epidemiology 2020, 31, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Win, N.N.; Kanda, T.; Nakamoto, S.; Moriyama, M.; Jiang, X.; Suganami, A.; Tamura, Y.; Okamoto, H.; Shirasawa, H. Inhibitory effect of Japanese rice-koji miso extracts on hepatitis A virus replication in association with the elevation of glucose-regulated protein 78 expression. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Kanda, T.; Suganami, A.; Nakamoto, S.; Win, N.N.; Tamura, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Matsuoka, S.; Yokosuka, O.; Kato, N.; et al. Antiviral activity of zinc sulfate against hepatitis A virus replication. Future Virol. 2019, 14, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Liu, P.; Yang, P.; Gao, Q.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, L.; Lin, J.; Su, D.; Rao, Z.; et al. Structural basis for neutralization of hepatitis A virus informs a rational design of highly potent inhibitors. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Kiyohara, T.; Kanda, T.; Imazeki, F.; Fujiwara, K.; Gauss-Müller, V.; Ishii, K.; Wakita, T.; Yokosuka, O. Inhibitory effects on HAV IRES-mediated translation and replication by a combination of amantadine and interferon-alpha. Virol. J. 2010, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Wu, S.; Kiyohara, T.; Nakamoto, S.; Jiang, X.; Miyamura, T.; Imazeki, F.; Ishii, K.; Wakita, T.; Yokosuka, O. Interleukin-29 suppresses hepatitis A and C viral internal ribosomal entry site-mediated translation. Viral Immunol. 2012, 25, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Yokosuka, O.; Imazeki, F.; Fujiwara, K.; Nagao, K.; Saisho, H. Amantadine inhibits hepatitis A virus internal ribosomal entry site-mediated translation in human hepatoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 331, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Imazeki, F.; Nakamoto, S.; Okitsu, K.; Fujiwara, K.; Yokosuka, O. Internal ribosomal entry-site activities of clinical isolate-derived hepatitis A virus and inhibitory effects of amantadine. Hepatol. Res. 2010, 40, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Sasaki, R.; Nakamoto, S.; Haga, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Shirasawa, H.; Okamoto, H.; Yokosuka, O. The sirtuin inhibitor sirtinol inhibits hepatitis A virus (HAV) replication by inhibiting HAV internal ribosomal entry site activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 466, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Kanda, T.; Nakamoto, S.; Saito, K.; Nakamura, M.; Wu, S.; Haga, Y.; Sasaki, R.; Sakamoto, N.; Shirasawa, H.; et al. The JAK2 inhibitor AZD1480 inhibits hepatitis A virus replication in Huh7 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 458, 908–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, G.; Totsuka, A.; Thompson, P.; Akatsuka, T.; Moritsugu, Y.; Feinstone, S.M. Identification of a surface glycoprotein on African green monkey kidney cells as a receptor for hepatitis A virus. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 4282–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Serrano, E.E.; González-López, O.; Das, A.; Lemon, S.M. Cellular entry and uncoating of naked and quasi-enveloped human hepatoviruses. Elife 2019, 8, e43983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Barrientos, R.; Shiota, T.; Madigan, V.; Misumi, I.; McKnight, K.L.; Sun, L.; Li, Z.; Meganck, R.M.; Li, Y.; et al. Gangliosides are essential endosomal receptors for quasi-enveloped and naked hepatitis A virus. Nat. Microbiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, Y.; Kanda, T.; Yasui, S.; Takahashi, K.; Haga, Y.; Sasaki, R.; Nakamura, M.; Wu, S.; Nakamoto, S.; Arai, M.; et al. Hepatitis A virus genotype IA-infected patient with marked elevation of aspartate aminotransferase levels. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 10, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, R.; Ono, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Wada, Y.; Nishizawa, K.; Fujii, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Kuroiwa, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ishii, K.; et al. A Cluster of Hepatitis A Infections Presumed to be Related to Asari Clams and Investigation of the Spread of Viral Contamination from Asari Clams. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 72, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogiso, T.; Sagawa, T.; Oda, M.; Yoshiko, S.; Kodama, K.; Taniai, M.; Tokushige, K. Characteristics of acute hepatitis A virus infection before and after 2001: A hospital-based study in Tokyo, Japan. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 1836–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, Y.; Okada, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Kakisaka, K.; Miyamoto, Y.; Miyasaka, A.; Takikawa, Y.; Nishizawa, T.; Okamoto, H. Fatal acute hepatic failure in a family infected with the hepatitis A virus subgenotype IB: A case report. Medicine 2017, 96, e7847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajpai, M.; Kakkar, B.; Patale, D. Role of high-volume plasma exchange in a case of a G6PD deficient patient presenting with HAV related acute liver failure and concomitant acute renal failure. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2019, 58, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.D.; Cho, E.J.; Ahn, C.; Park, S.K.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, H.C.; Kim, D.Y.; Choi, M.S.; Wang, H.J.; Kim, I.H.; et al. A Model to Predict 1-Month Risk of Transplant or Death in Hepatitis A-Related Acute Liver Failure. Hepatology 2019, 70, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, P.S.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, J.; Park, S.H.; Yoon, S.K.; Chung, W.J.; Shin, E.C. CXCL10 is produced in hepatitis A virus-infected cells in an IRF3-dependent but IFN-independent manner. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Ochoa, J.L.; Corral-Jara, K.F.; Charles-Niño, C.L.; Panduro, A.; Fierro, N.A. Conjugated Bilirubin Upregulates TIM-3 Expression on CD4(+)CD25(+) T Cells: Anti-Inflammatory Implications for Hepatitis A Virus Infection. Viral Immunol. 2018, 31, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Jung, M.K.; Lee, J.; Choi, S.J.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, H.W.; Lee, J.J.; Kim, H.J.; Ahn, S.H.; Lee, D.H.; et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor-producing T-regulatory Cells Are Associated With Severe Liver Injury in Patients With Acute Hepatitis A. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1047–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaya, S.; Michailidis, E.; Korol, C.B.; Kabbani, M.; Cobat, A.; Bastard, P.; Lee, Y.S.; Hernandez, N.; Drutman, S.; de Jong, Y.P.; et al. Inherited IL-18BP deficiency in human fulminant viral hepatitis. J. Exp. Med. 2019, 216, 1777–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouanguy, E. Human genetic basis of fulminant viral hepatitis. Hum. Genet. 2020, 139, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Chang, D.Y.; Lee, H.W.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.H.; Sung, P.S.; Kim, K.H.; Hong, S.H.; Kang, W.; Lee, J.; et al. Innate-like Cytotoxic Function of Bystander-Activated CD8(+) T Cells Is Associated with Liver Injury in Acute Hepatitis A. Immunity 2018, 48, 161–173.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Lemon, S.M. Innate Immunity to Enteric Hepatitis Viruses. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2019, 9, a033464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikata, R.; Yokosuka, O.; Imazeki, F.; Fukai, K.; Kanda, T.; Saisho, H. Prolonged acute hepatitis A mimicking autoimmune hepatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 3791–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Ghaffar, T.Y.; Sira, M.M.; Sira, A.M.; Salem, T.A.; El-Sharawy, A.A.; El Naghi, S. Serological markers of autoimmunity in children with hepatitis A: Relation to acute and fulminant presentation. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 27, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albillos, A.; Lario, M.; Álvarez-Mon, M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: Distinctive features and clinical relevance. J. Hepatol. 2014, 61, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, D.; Zhang, D.; Yang, T.; Mu, J.; Zhao, P.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Cheng, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; et al. Effect of COVID-19 on patients with compensated chronic liver diseases. Hepatol. Int. 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, M.; Imazeki, F.; Yonemitsu, Y.; Kanda, T.; Fujiwara, K.; Fukai, K.; Watanabe, A.; Sato, T.; Oda, S.; Yokosuka, O. Opportunistic infection in the patients with acute liver failure: A report of three cases with one fatality. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2009, 2, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, M.; Kanda, T.; Yasui, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Imazeki, F.; Watanabe, A.; Sato, T.; Oda, S.; Yokosuka, O. Opportunistic infection in patients with acute liver failure. Hepatol. Int. 2014, 8, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Haga, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Mikata, R.; Arai, M.; Kanda, T.; Oda, S.; Yokosuka, O. Infectious complications, steroid use and timing for emergency liver transplantation in acute liver failure: Analysis in a Japanese center. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Sci. 2016, 23, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doycheva, I.; Thuluvath, P.J. Acute-on-chronic liver failure in liver transplant candidates with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebicka, J.; Sundaram, V.; Moreau, R.; Jalan, R.; Arroyo, V. Liver Transplantation for Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure: Science or Fiction? Liver Transpl. 2020, 26, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, V.; Mahmud, N.; Perricone, G.; Katarey, D.; Wong, R.J.; Karvellas, C.J.; Fortune, B.E.; Rahimi, R.S.; Maddur, H.; Jou, J.H.; et al. Long-term outcomes of patients undergoing liver transplantation for acute-on-chronic liver failure. Liver Transpl. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, A.; Regunath, H.; Rojas-Moreno, C.; Salzer, W.; Christensen, G. Imported Infections in Rural Mid-West United States—A Report from a Tertiary Care Center. Mo. Med. 2020, 117, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- SarialİoĞlu, F.; Belen, F.B.; Hayran, K.M. Hepatitis A susceptibility parallels high COVID-19 mortality. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.J.; Lin, K.Y.; Sun, H.Y.; Sheng, W.H.; Hsieh, S.M.; Huang, Y.C.; Cheng, A.; Liu, W.C.; Hung, C.C.; Chang, S.C. Incidence of acute hepatitis A among HIV-positive patients during an outbreak among MSM in Taiwan: Impact of HAV vaccination. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.C.; Chiang, P.H.; Liao, Y.H.; Huang, L.C.; Hsieh, Y.J.; Chiu, C.M.; Lo, Y.C.; Yang, C.H.; Yang, J.Y. Outbreak of hepatitis A virus infection in Taiwan, June 2015 to September 2017. Euro. Surveill. 2019, 24, 1800133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Outcalt, D. CDC provides advice on recent hepatitis A outbreaks. J. Fam. Pract. 2018, 67, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Latash, J.; Dorsinville, M.; Del Rosso, P.; Antwi, M.; Reddy, V.; Waechter, H.; Lawler, J.; Boss, H.; Kurpiel, P.; Backenson, P.B.; et al. Notes from the Field: Increase in Reported Hepatitis A Infections Among Men Who Have Sex with Men - New York City, January-August 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 999–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fraile, M.; Barreiro Alonso, E.; de la Vega, J.; Rodríguez, M.; García-López, R.; Rodríguez, M. Acute hepatitis due to hepatitis A virus during the 2017 epidemic expansion in Asturias. Spain. Med. Clin. 2019, 152, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, V.M.; Lago, B.V.; Sousa, P.S.F.; Mello, F.C.A.; Souza, C.B.; Pinto, L.C.M.; Ginuino, C.F.; Fernandes, C.A.S.; Aguiar, S.F.; Villar, L.M.; et al. Hepatitis A Strain Linked to the European Outbreaks During Gay Events between 2016 and 2017, Identified in a Brazilian Homosexual Couple in 2017. Viruses 2019, 11, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minosse, C.; Messina, F.; Garbuglia, A.R.; Meschi, S.; Scognamiglio, P.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Ippolito, G.; Lanini, S. Origin of HAV strains responsible for 2016-2017 outbreak among MSM: Viral phylodynamics in Lazio region. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanford, R.E.; Feng, Z.; Chavez, D.; Guerra, B.; Brasky, K.M.; Zhou, Y.; Yamane, D.; Perelson, A.S.; Walker, C.M.; Lemon, S.M. Acute hepatitis A virus infection is associated with a limited type I interferon response and persistence of intrahepatic viral RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11223–11228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, N.; Yoshida, H.; Ono-Nita, S.K.; Kato, J.; Goto, T.; Otsuka, M.; Lan, K.; Matsushima, K.; Shiratori, Y.; Omata, M. Activation of intracellular signaling by hepatitis B and C viruses: C-viral core is the most potent signal inducer. Hepatology 2000, 32, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Yokosuka, O.; Kato, N.; Imazeki, F.; Fujiwara, K.; Kawai, S.; Saisho, H.; Omata, M. Hepatitis A virus VP3 may activate serum response element associated transcription. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 38, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Yokosuka, O.; Imazeki, F.; Saisho, H. Hepatitis A protein VP1-2A reduced cell viability in Huh-7 cells with hepatitis C virus subgenomic RNA replication. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 21, 625–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brack, K.; Berk, I.; Magulski, T.; Lederer, J.; Dotzauer, A.; Vallbracht, A. Hepatitis A virus inhibits cellular antiviral defense mechanisms induced by double-stranded RNA. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 11920–11930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai-Yuki, A.; Hensley, L.; McGivern, D.R.; González-López, O.; Das, A.; Feng, H.; Sun, L.; Wilson, J.E.; Hu, F.; Feng, Z.; et al. MAVS-dependent host species range and pathogenicity of human hepatitis A virus. Science 2016, 353, 1541–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Qu, L.; Chen, Z.; Yi, M.; Li, K.; Lemon, S.M. Disruption of innate immunity due to mitochondrial targeting of a picornaviral protease precursor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7253–7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, T.; Gauss-Müller, V.; Cordes, S.; Tamura, R.; Okitsu, K.; Shuang, W.; Nakamoto, S.; Fujiwara, K.; Imazeki, F.; Yokosuka, O. Hepatitis A virus (HAV) proteinase 3C inhibits HAV IRES-dependent translation and cleaves the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein. J. Viral Hepat. 2010, 17, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Steele, R.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Hepatitis C virus infection induces the beta interferon signaling pathway in immortalized human hepatocytes. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 12375–12381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, S.F.; Chisari, F.V. Stealth and cunning: Hepatitis B and hepatitis C viruses. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 9369–9380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.; Aydin, Y.; Moroz, K. Chaperone-Mediated Autophagy in the Liver: Good or Bad? Cells 2019, 8, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.; Li, W.Z.; Zhang, S.; Hu, B.; Li, Y.X.; Li, H.D.; Tang, H.H.; Li, Q.W.; Guan, Y.Y.; Liu, L.X.; et al. SNX10 mediates alcohol-induced liver injury and steatosis by regulating the activation of chaperone-mediated autophagy. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelini, G.; Castagneto Gissey, L.; Del Corpo, G.; Giordano, C.; Cerbelli, B.; Severino, A.; Manco, M.; Basso, N.; Birkenfeld, A.L.; Bornstein, S.R.; et al. New insight into the mechanisms of ectopic fat deposition improvement after bariatric surgery. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, S.; Tachikawa, N.; Nakajima, A.; Daikoku, M.; Yano, M.; Kikuchi, Y.; Yasuoka, A.; Kimura, S.; Oka, S. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection on acute hepatitis A virus infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Chen, G.J.; Lee, Y.L.; Huang, Y.C.; Cheng, A.; Sun, H.Y.; Chang, S.Y.; Liu, C.E.; Hung, C.C. Hepatitis A virus infection and hepatitis A vaccination in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients: A review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 3589–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors (Year) [References] | N | Acute Insults | Underlying CLD | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrawal S, et al. (2018) [17] | 1 | HAV | NASH | Recovered |

| Kahraman A, et al. (2006) [19] | 1 | HAV | NASH and HIV | Died |

| Lefillatre P, et al. (2000) [21] | 1 | HAV | ALD | Died |

| Spada E, et al. (2005) [22] | 2 | HAV | ALD and HCV | Died |

| Authors (Year) [References] | N | Acute Insults | Underlying CLD | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lefillatre P, et al. (2000) [21] | 1 | HAV | HBV, HCV, and HIV | Died |

| Spada E, et al. (2005) [22] | 1 | HAV | HCV and HIV | Died |

| Costa-Mattioli et al. (2002) [44] | 1 | HAV | HIV | Alive; HAV RNA detected in 256 days |

| Maki Y, et al. (2020) [45] | 1 | HAV | HIV | Died |

| Authors (Year) [References] | N | Acute Insults | Underlying CLD | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tassopoulos N, et al. (1985) [57] | 10 | HAV | HBV | Recovered |

| Vento S, et al. (1998) [9] | 10 | HAV | HBV | Recovered (marked cholestasis, 1) |

| Lefillatre P, et al. (2000) [21] | 1 | HAV | HBV | Died |

| Cooksley WGE, et al. (2000) [58] | 27,346 | HAV | HBV | Died, 15 (0.05%) |

| Sagnelli E, et al. (2006) [59] | 13 | HAV | HBV | Recovered (severe hepatitis, 1) |

| Zhang X, et al. (2010) [60] | 52 | HAV | HBV | Died, 1 (1.9%) [Hepatic failure, 6 (11.5%)] |

| Fu J, et al. (2016) [61] | 35 | HAV | HBV | Recovered |

| Beisei C, et al. (2020) [62] | 1 | HAV | HBV | Recovered (seroconversion of HBeAg to anti-HBe) |

| Lefillatre P, et al. (2000) [21] | 1 | HAV | HBV, HCV, and HIV | Died |

| Authors (Year) [References] | N | Acute Insults | Underlying CLD | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vento S, et al. (1998) [9] | 17 | HAV | HCV | Recovered, 10; fulminant hepatitis, 7 |

| Sagnelli E, et al. (2006) [59] | 8 | HAV | HCV | Recovered |

| Deterding K, et al. (2006) [77] | 17 | HAV | HCV | Fulminant hepatitis, 0 |

| Spada E, et al. (2005) [22] | 1 | HAV | HCV and ALD | Died |

| Spada E, et al. (2005) [22] | 1 | HAV | HCV and HIV | Died |

| Lefillatre P, et al. (2000) [21] | 1 | HAV | HBV plus HCV and HIV | Died |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanda, T.; Sasaki, R.; Masuzaki, R.; Takahashi, H.; Mizutani, T.; Matsumoto, N.; Nirei, K.; Moriyama, M. Co-Occurrence of Hepatitis A Infection and Chronic Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176384

Kanda T, Sasaki R, Masuzaki R, Takahashi H, Mizutani T, Matsumoto N, Nirei K, Moriyama M. Co-Occurrence of Hepatitis A Infection and Chronic Liver Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(17):6384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176384

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanda, Tatsuo, Reina Sasaki, Ryota Masuzaki, Hiroshi Takahashi, Taku Mizutani, Naoki Matsumoto, Kazushige Nirei, and Mitsuhiko Moriyama. 2020. "Co-Occurrence of Hepatitis A Infection and Chronic Liver Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 17: 6384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176384

APA StyleKanda, T., Sasaki, R., Masuzaki, R., Takahashi, H., Mizutani, T., Matsumoto, N., Nirei, K., & Moriyama, M. (2020). Co-Occurrence of Hepatitis A Infection and Chronic Liver Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(17), 6384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176384