A Whey Fraction Rich in Immunoglobulin G Combined with Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 Exhibits Synergistic Effects against Campylobacter jejuni

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

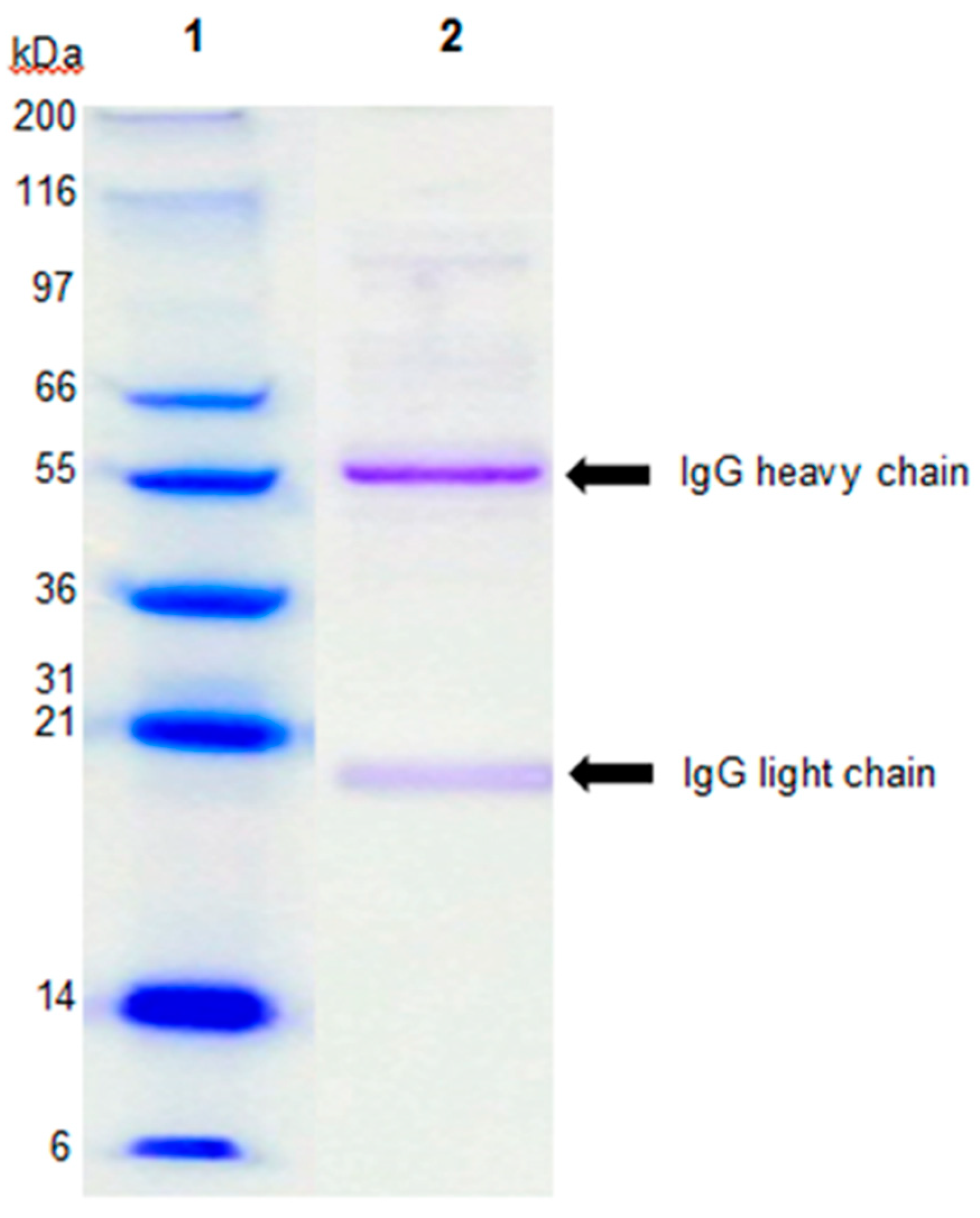

2.1. Characterization of Immunoglobulin G-enriched Powder (IGEP)

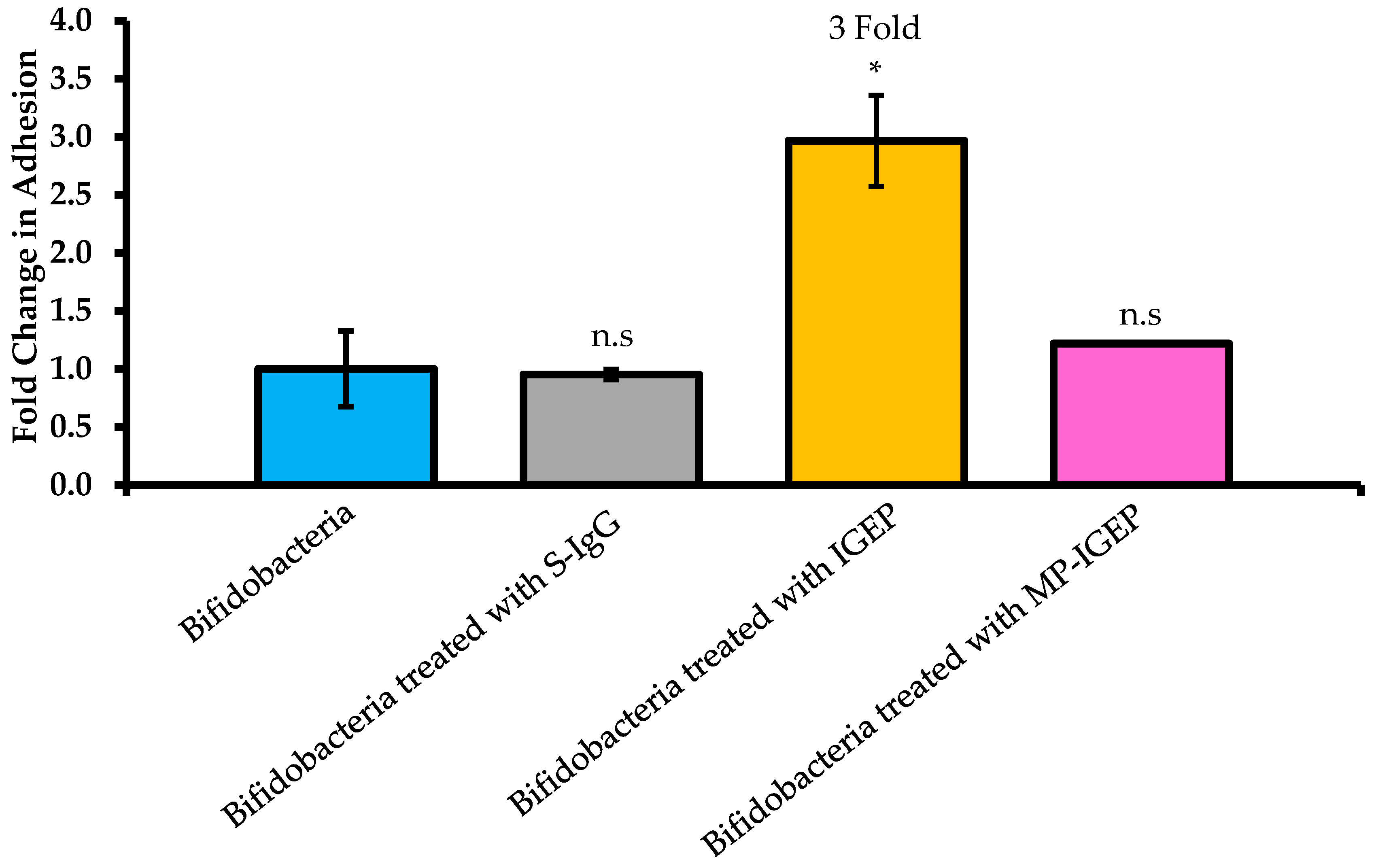

2.2. Effect of IGEP on B. infantis Adhesion

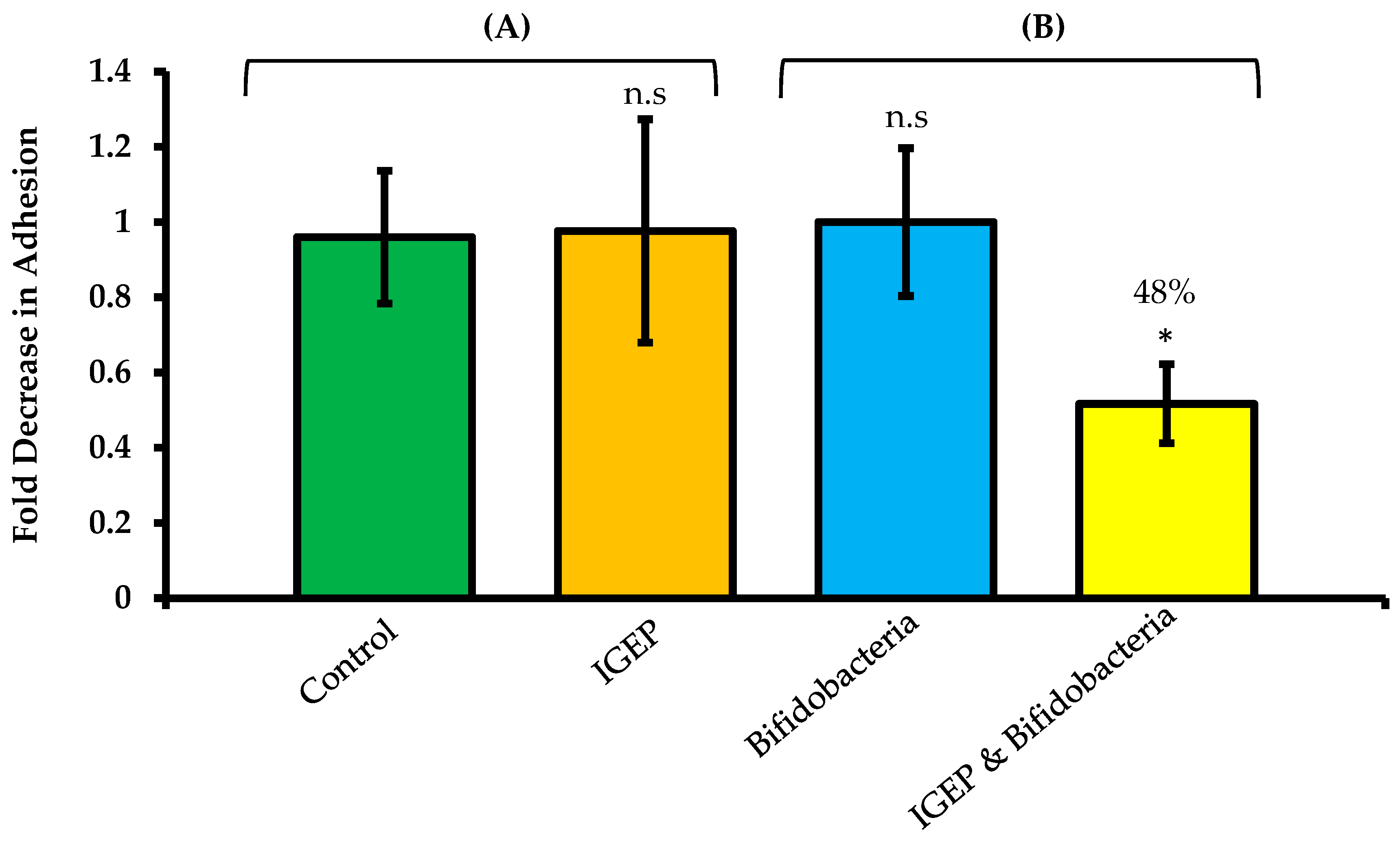

2.3. Combined Effect of IGEP and B. infantis on C. jejuni Adhesion

2.4. B. infantis Growth in IGEP

2.5. B. infantis Metabolite Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Bacterial Strains

4.2. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) Analysis

4.3. Periodate Treatment of Powder

4.4. Bacterial Culture

4.5. Exposure of B. infantis to IGEP for Adhesion Assays

4.6. Mammalian Cell Culture Conditions

4.7. Adhesion Assays with B. infantis

4.8. Anti-Infective Assays and Exclusion Assay

4.9. Effect of IGEP on the Growth of B. infantis

4.10. B. infantis Metabolite Analysis

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fenelon, M.A.; Hickey, R.M.; Buggy, A.; McCarthy, N.; Murphy, E.G. Whey Proteins in Infant Formula. In Whey Proteins: From Milk to Medicine; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 439–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; An, H.J.; Garrido, D.; German, J.B.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Mills, D.A. Proteomic Analysis of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis Reveals the Metabolic Insight on Consumption of Prebiotics and Host Glycans. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoCascio, R.G.; Ninonuevo, M.R.; Freeman, S.L.; Sela, D.A.; Grimm, R.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Mills, D.A.; German, J.B. Glycoprofiling of Bifidobacterial Consumption of Human Milk Oligosaccharides Demonstrates Strain Specific, Preferential Consumption of Small Chain Glycans Secreted in Early Human Lactation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8914–8919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoCascio, R.G.; Desai, P.; Sela, D.A.; Weimer, B.; Mills, D.A. Broad Conservation of Milk Utilization Genes in Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis as Revealed by Comparative Genomic Hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 7373–7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcobal, A.; Barboza, M.; Froehlich, J.W.; Block, D.E.; German, J.B.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Mills, D.A. Consumption of Human Milk Oligosaccharides by Gut-Related Microbes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 5334–5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westermann, C.; Gleinser, M.; Corr, S.C.; Riedel, C.U. A Critical Evaluation of Bifidobacterial Adhesion to the Host Tissue. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balmer, S.E.; Scott, P.H.; Wharton, B.A. Diet and Faecal Flora in the Newborn: Casein and Whey Proteins. Arch. Dis. Child. 1989, 64, 1678–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelzle, H.; Wirth, S.; Skopnik, H.; Radke, M.; Knol, J.; Böckler, H.M.; Brönstrup, A.; Wells, J.; Fusch, C. Randomized Double-Blind Study of the Nutritional Efficacy and Bifidogenicity of a New Infant Formula Containing Partially Hydrolyzed Protein, a High β-Palmitic Acid Level, and Nondigestible Oligosaccharides. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2003, 36, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascoët, J.M.; Hubert, C.; Rochat, F.; Legagneur, H.; Gaga, S.; Emady-Azar, S.; Steenhout, P.G. Effect of Formula Composition on the Development of Infant Gut Microbiota. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2011, 52, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sosa, S.; Martín, M.-J.; Hueso, P. The Sialylated Fraction of Milk Oligosaccharides Is Partially Responsible for Binding to Enterotoxigenic and Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Human Strains. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 3067–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.M.; Goode, P.L.; Mobasseri, A.; Zopf, D. Inhibition of Helicobacter Pylori Binding to Gastrointestinal Epithelial Cells by Sialic Acid-Containing Oligosaccharides. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrosovich, M.N.; Gambaryan, A.S.; Tuzikov, A.B.; Byramova, N.E.; Mochalova, L.V.; Golbraikh, A.A.; Shenderovich, M.D.; Finne, J.; Bovin, N.V. Probing of the Receptor-Binding Sites of the H1 and H3 Influenza A and Influenza B Virus Hemagglutinins by Synthetic and Natural Sialosides. Virology 1993, 196, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrin, S.T.; Lane, J.A.; Marotta, M.; Bode, L.; Carrington, S.D.; Irwin, J.A.; Hickey, R.M. Bovine Colostrum-Driven Modulation of Intestinal Epithelial Cells for Increased Commensal Colonisation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 2745–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrin, S.T.; Owens, R.A.; Le Berre, M.; Gerlach, J.Q.; Joshi, L.; Bode, L.; Irwin, J.A.; Hickey, R.M. Interrogation of Milk-Driven Changes to the Proteome of Intestinal Epithelial Cells by Integrated Proteomics and Glycomics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Klaassens, E.S.; Malinen, E.; de Vos, W.M.; Vaughan, E.E. Differential Transcriptional Response of Bifidobacterium longum to Human Milk, Formula Milk, and Galactooligosaccharide. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 4686–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chichlowski, M.; De Lartigue, G.; German, J.B.; Raybould, H.E.; Mills, D.A. Bifidobacteria Isolated From Infants and Cultured on Human Milk Oligosaccharides Affect Intestinal Epithelial Function. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 55, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavanaugh, D.W.; O’Callaghan, J.; Buttó, L.F.; Slattery, H.; Lane, J.; Clyne, M.; Kane, M.; Joshi, L.; Hickey, R.M. Exposure of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis to Milk Oligosaccharides Increases Adhesion to Epithelial Cells and Induces a Substantial Transcriptional Response. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, E.; Slattery, H.; Thompson, A.; Kilcoyne, M.; Joshi, L.; Hickey, R.; Quinn, E.M.; Slattery, H.; Thompson, A.P.; Kilcoyne, M.; et al. Mining Milk for Factors Which Increase the Adherence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis to Intestinal Cells. Foods 2018, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, E.M.; Slattery, H.; Walsh, D.; Joshi, L.; Hickey, R.M. Bifidobacterium longum Subsp. Infantis ATCC 15697 and Goat Milk Oligosaccharides Show Synergism In Vitro as Anti-Infectives against Campylobacter jejuni. Foods 2020, 9, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A Rapid and Sensitive Method for the Quantitation of Microgram Quantities of Protein Utilizing the Principle of Protein-Dye Binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemka, A.; Whelan, S.; Gough, R.; Clyne, M.; Gallagher, M.E.; Carrington, S.D.; Bourke, B. Purified Chicken Intestinal Mucin Attenuates Campylobacter jejuni Pathogenicity in Vitro. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 59, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.A.; Mariño, K.; Naughton, J.; Kavanaugh, D.; Clyne, M.; Carrington, S.D.; Hickey, R.M. Anti-Infective Bovine Colostrum Oligosaccharides: Campylobacter jejuni as a Case Study. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 157, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, S.; Macfarlane, G.T. Regulation of Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palframan, R.J.; Gibson, G.R.; Rastall, R.A. Carbohydrate Preferences of Bifidobacterium Species 71 Carbohydrate Preferences of Bifidobacterium Species Isolated from the Human Gut. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2003, 4, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Alvarado, R.; Phinney, B.; Lönnerdal, B. Proteomic Characterization of Human Milk Whey Proteins during a Twelve-Month Lactation Period. J. Proteome Res. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, A.; Barton, L.D.; Sanders, J.T.; Zhang, Q. Exploration of Bovine Milk Proteome in Colostral and Mature Whey Using an Ion-Exchange Approach. J. Proteome Res. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Hurou-Luron, I.; Blat, S.; Boudry, G. Breast- v. Formula-Feeding: Impacts on the Digestive Tract and Immediate and Long-Term Health Effects. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010, 23, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golinelli, L.; Mere Del Aguila, E.; Paschoalin, V.; Silva, J.; Conte Junior, C. Functional aspect of colostrum and whey proteins in human milk. J. Hum. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 2, 1035. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, K. Therapeutic Applications of Whey Protein. Altern. Med. Rev. 2004, 9, 136–156. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, N.L.; Spoerri, I.; Schopfer, J.F.; Nembrini, C.; Merky, P.; Massacand, J.; Urban, J.F.; Lamarre, A.; Burki, K.; Odermatt, B.; et al. Mechanisms of Neonatal Mucosal Antibody Protection. J. Immunol. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellens, D.J.; de Leeuw, P.W.; Straver, P.J. The Detection of Rotavirus Specific Antibody in Colostrum and Milk by ELISA. Ann. Rech. Vet. 1978, 9, 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Recio, I.; Moreno, F.J.; López-Fandiño, R. Glycosylated Dairy Components: Their Roles in Nature and Ways to Make Use of Their Biofunctionality in Dairy Products. In Dairy-Derived Ingredients: Food and Nutraceutical Uses; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston/Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 170–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Quintela, A.; Alende, R.; Gude, F.; Campos, J.; Rey, J.; Meijide, L.M.; Fernandez-Merino, C.; Vidal, C. Serum Levels of Immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, IgM) in a General Adult Population and Their Relationship with Alcohol Consumption, Smoking and Common Metabolic Abnormalities. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudelj, I.; Lauc, G.; Pezer, M. Immunoglobulin G Glycosylation in Aging and Diseases. Cell. Immunol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, G.; Ottenhoff, T.H.M.; Joosten, S.A. Antibody glycosylation in inflammation, disease and vaccination. Semin. Immunol. 2018, 39, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeling, M.; Brückner, C.; Nimmerjahn, F. Differential antibody glycosylation in autoimmunity: Sweet biomarker or modulator of disease activity? Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2017, 13, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, C.A.; Spiegelberg, H.L.; Grey, H.M. The Carbohydrate Content of Fragments and Polypeptide Chains of Human γG-Myeloma Proteins of Different Heavy-Chain Subclasses. Biochemistry 1968, 7, 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Gong, C.; Ding, Y.; Ding, G.; Xu, X.; Deng, C.; Ze, X.; Malard, P.; Ben, X. Probiotics Maintain Intestinal Secretory Immunoglobulin A Levels in Healthy Formula-Fed Infants: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Benef. Microbes 2019, 10, 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, G.P.; Ladinsky, M.S.; Yu, K.B.; Sanders, J.G.; Yoo, B.B.; Chou, W.C.; Conner, M.E.; Earl, A.M.; Knight, R.; Bjorkman, P.J.; et al. Gut Microbiota Utilize Immunoglobulin a for Mucosal Colonization. Science 2018, 360, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbins, H.L.; Proctor, G.B.; Yakubov, G.E.; Wilson, S.; Carpenter, G.H. SIgA Binding to Mucosal Surfaces Is Mediated by Mucin-Mucin Interactions. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.T.; Hodgkinson, A.J.; Prosser, C.G.; Davis, S.R. Immune Components of Colostrum and Milk—A Historical Perspective. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 2007, 12, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, N.; Hickey, R.M.; Lokesh, J. Bovine Glycomacropeptide Promotes the Growth of Bifidobacterium longum Subsp. infantis and Modulates Its Gene Expression. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 101, 6730–6741. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, K.; Tamura, N.; Kobayashi-Hattori, K.; Yoshida, T.; Hara-Kudo, Y.; Ikedo, M.; Sugita-Konishi, Y.; Hattori, M. Prevention of Intestinal Infection by Glycomacropeptide. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69, 2294–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feeney, S.; Gerlach, J.Q.; Slattery, H.; Kilcoyne, M.; Hickey, R.M.; Joshi, L. Lectin Microarray Profiling and Monosaccharide Analysis of Bovine Milk Immunoglobulin G Oligosaccharides during the First 10 Days of Lactation. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1564–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, D.; Nwosu, C.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Aldredge, D.; German, J.B.; Lebrilla, C.B.; Mills, D.A. Endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidases from infant gut-associated bifidobacteria release complex N-glycans from human milk glycoproteins. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2012, 11, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J.N.; Wormald, M.R.; Sim, R.B.; Rudd, P.M.; Dwek, R.A. The Impact of Glycosylation on the Biological Function and Structure of Human Immunoglobulins. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 25, 21–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, T.S.; Briggs, J.B.; Borge, S.M.; Jones, A.J. Species-Specific Variation in Glycosylation of IgG: Evidence for the Species-Specific Sialylation and Branch-Specific Galactosylation and Importance for Engineering Recombinant Glycoprotein Therapeutics. Glycobiology 2000, 10, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, D.; Almeida, R.A.; Dunlap, J.R.; Oliver, S.P. Bovine Lactoferrin Serves as a Molecular Bridge for Internalization of Streptococcus Uberis into Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 137, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrin, S.T.; McCarthy, G.; Kennedy, D.; Marotta, M.; Irwin, J.A.; Hickey, R.M. Immunoglobulin G from Bovine Milk Primes Intestinal Epithelial Cells for Increased Colonization of Bifidobacteria. AMAB Express. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Oda, H.; Wakabayashi, H.; Yamauchi, K.; Abe, F. Lactoferrin and Bifidobacteria. BioMetals 2014, 27, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, C.; Conte, M.P.; Seganti, L.; Polidoro, M.; Alfsen, A.; Valenti, P. Influence of Lactoferrin on the Entry Process of Escherichia coli HB101 (PRI203) in HeLa Cells. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1993, 182, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Biase, A.M.; Tinari, A.; Pietrantoni, A.; Antonini, G.; Valenti, P.; Conte, M.P.; Superti, F. Effect of bovine lactoferricin on enteropathogenic Yersinia adhesion and invasion in HEp-2 cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-W.; Liu, Z.-S.; Kuo, T.-C.; Hsieh, M.-C.; Li, Z.-W. Prebiotic Effects of Bovine Lactoferrin on Specific Probiotic Bacteria. BioMetals 2017, 30, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.A.; Lane, J.A.; Kilcoyne, M.; Joshi, L.; Hickey, R.M. Defatted Bovine Milk Fat Globule Membrane Inhibits Association of Enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 with Human HT-29 Cells. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 59, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douëllou, T.; Montel, M.C.; Thevenot Sergentet, D. Invited Review: Anti-Adhesive Properties of Bovine Oligosaccharides and Bovine Milk Fat Globule Membrane-Associated Glycoconjugates against Bacterial Food Enteropathogens. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 3348–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, S.; Ryan, J.; Kilcoyne, M.; Joshi, L.; Hickey, R. Glycomacropeptide Reduces Intestinal Epithelial Cell Barrier Dysfunction and Adhesion of Entero-Hemorrhagic and Entero-Pathogenic Escherichia coli in Vitro. Foods 2017, 6, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idota, T.; Kawakami, H.; Nakajima, I. Growth-Promoting Effects of N-Acetylneuraminic Acid-Containing Substances on Bifidobacteria. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1994, 58, 1720–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yu, B.; Karim, M.; Hu, H.; Sun, Y.; McGreevy, P.; Petocz, P.; Held, S.; Brand-Miller, J. Dietary Sialic Acid Supplementation Improves Learning and Memory in Piglets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woof, J.M. Immunoglobulins and Their Receptors, and Subversion of Their Protective Roles by Bacterial Pathogens. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, R.; Marnila, P. Milk Immunoglobulins for Health Promotion. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, 1262–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Nagai, S.; Yabe, T.; Nagaoka, S.; Minamoto, N.; Takahashi, T.; Matsuda, T.; Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T.; Ebina, T.; et al. The Bovine Lactophorin C-Terminal Fragment and PAS6/7 Were Both Potent in the Inhibition of Human Rotavirus Replication in Cultured Epithelial Cells and the Prevention of Experimental Gastroenteritis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 1386–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palacios, G.M.; Calva, J.J.; Pickering, L.K.; Lopez-Vidal, Y.; Volkow, P.; Pezzarossi, H.; West, M.S. Protection of breast-fed infants against Campylobacter diarrhea by antibodies in human milk. J. Pediatr. 1990, 116, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Cyr, M.J.; Guyard-Nicodème, M.; Messaoudi, S.; Chemaly, M.; Cappelier, J.-M.; Dousset, X.; Haddad, N. Recent Advances in Screening of Anti-Campylobacter Activity in Probiotics for Use in Poultry. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, A.; Bücker, R.; Boehm, M.; Zarzecka, U.; Tegtmeyer, N.; Sticht, H.; Schulzke, J.D.; Backert, S. Campylobacter jejuni Enters Gut Epithelial Cells and Impairs Intestinal Barrier Function through Cleavage of Occludin by Serine Protease HtrA. Gut Pathog. 2019, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gueimonde, M.; Margolles, A.; Clara, G.; Salminen, S. Competitive Exclusion of Enteropathogens from Human Intestinal Mucus by Bifidobacterium Strains with Acquired Resistance to Bile—A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 113, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xu, J.; Shuai, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, W. The S-Layer Proteins of Lactobacillus Crispatus Strain ZJ001 Is Responsible for Competitive Exclusion against Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella typhimurium. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 115, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dec, M.; Nowaczek, A.; Urban-Chmiel, R.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D.; Wernicki, A. Probiotic Potential of Lactobacillus Isolates of Chicken Origin with Anti-Campylobacter Activity. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2018, 80, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baffoni, L.; Gaggìa, F.; Di Gioia, D.; Santini, C.; Mogna, L.; Biavati, B. A Bifidobacterium-Based Synbiotic Product to Reduce the Transmission of C. jejuni along the Poultry Food Chain. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 157, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffoni, L.; Gaggìa, F.; Garofolo, G.; Di Serafino, G.; Buglione, E.; Di Giannatale, E.; Di Gioia, D. Evidence of Campylobacter jejuni Reduction in Broilers with Early Synbiotic Administration. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 251, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arsi, K.; Donoghue, A.M.; Woo-Ming, A.; Blore, P.J.; Donoghue, D.J. The Efficacy of Selected Probiotic and Prebiotic Combinations in Reducing Campylobacter Colonization in Broiler Chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2015, 24, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Health Organization; Campylobacter. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/campylobacter (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Janssen, R.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Cawthraw, S.A.; van Pelt, W.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Owen, R.J. Host-Pathogen Interactions in Campylobacter Infections: The Host Perspective. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 21, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, D.; Dallas, D.C.; Mills, D.A. Consumption of Human Milk Glycoconjugates by Infant-Associated Bifidobacteria: Mechanisms and Implications. Microbiol. 2013, 159, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Man, J.C.; Rogosa, M.; Sharpe, M.E. A Medium For The Cultivation of Lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1960, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M.M.; Forde, B.M.; Neville, B.; Ross, P.R.; O’Toole, P.W. Carbohydrate Catabolic Flexibility in the Mammalian Intestinal Commensal Lactobacillus ruminis Revealed by Fermentation Studies Aligned to Genome Annotations. Microb. Cell Fact. 2011, 10 (Suppl. 1), S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Same, R.G.; Tamma, P.D. Campylobacter Infections in Children. Pediatr. Rev. 2018, 39, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, D.; Pasmans, F.; Messens, W.; Martel, A.; Van Immerseel, F.; Rasschaert, G.; Heyndrickx, M.; Van Deun, K.; Haesebrouck, F. Poultry as a Host for the Zoonotic Pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2012, 12, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, A.M.; Harris, N.V.; Digiacomo, R.F. The Role of Exposure to Animals in the Etiology of Campylobacter jejuni/coli Enteritis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1993, 137, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Concentration (mM) | Control | IGEP |

|---|---|---|

| Acetate | 2.42 | 2.70 |

| Lactate | 0.62 | 0.77 |

| Formate | 0.32 | 0.26 |

| Ethanol | ND | 1.15 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quinn, E.M.; Kilcoyne, M.; Walsh, D.; Joshi, L.; Hickey, R.M. A Whey Fraction Rich in Immunoglobulin G Combined with Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 Exhibits Synergistic Effects against Campylobacter jejuni. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134632

Quinn EM, Kilcoyne M, Walsh D, Joshi L, Hickey RM. A Whey Fraction Rich in Immunoglobulin G Combined with Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 Exhibits Synergistic Effects against Campylobacter jejuni. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(13):4632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134632

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuinn, Erinn M., Michelle Kilcoyne, Dan Walsh, Lokesh Joshi, and Rita M. Hickey. 2020. "A Whey Fraction Rich in Immunoglobulin G Combined with Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 Exhibits Synergistic Effects against Campylobacter jejuni" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 13: 4632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134632

APA StyleQuinn, E. M., Kilcoyne, M., Walsh, D., Joshi, L., & Hickey, R. M. (2020). A Whey Fraction Rich in Immunoglobulin G Combined with Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 Exhibits Synergistic Effects against Campylobacter jejuni. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(13), 4632. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134632