A Yeast-Based Model for Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathies: A Simple System for Complex, Heterogeneous Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Genetic Background of Charcot–Marie–Tooth Disease

3. Therapeutic Approaches for Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disorder

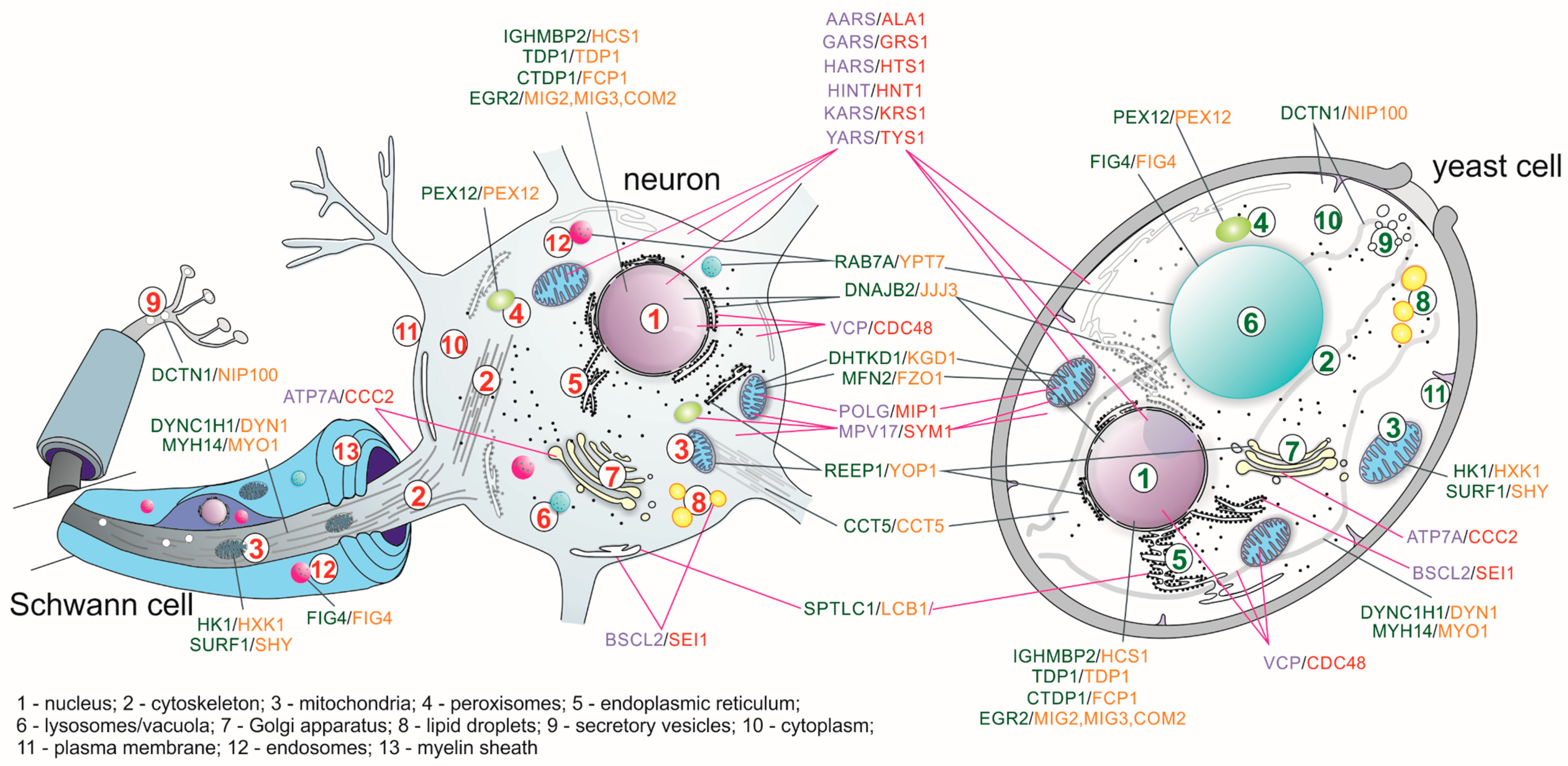

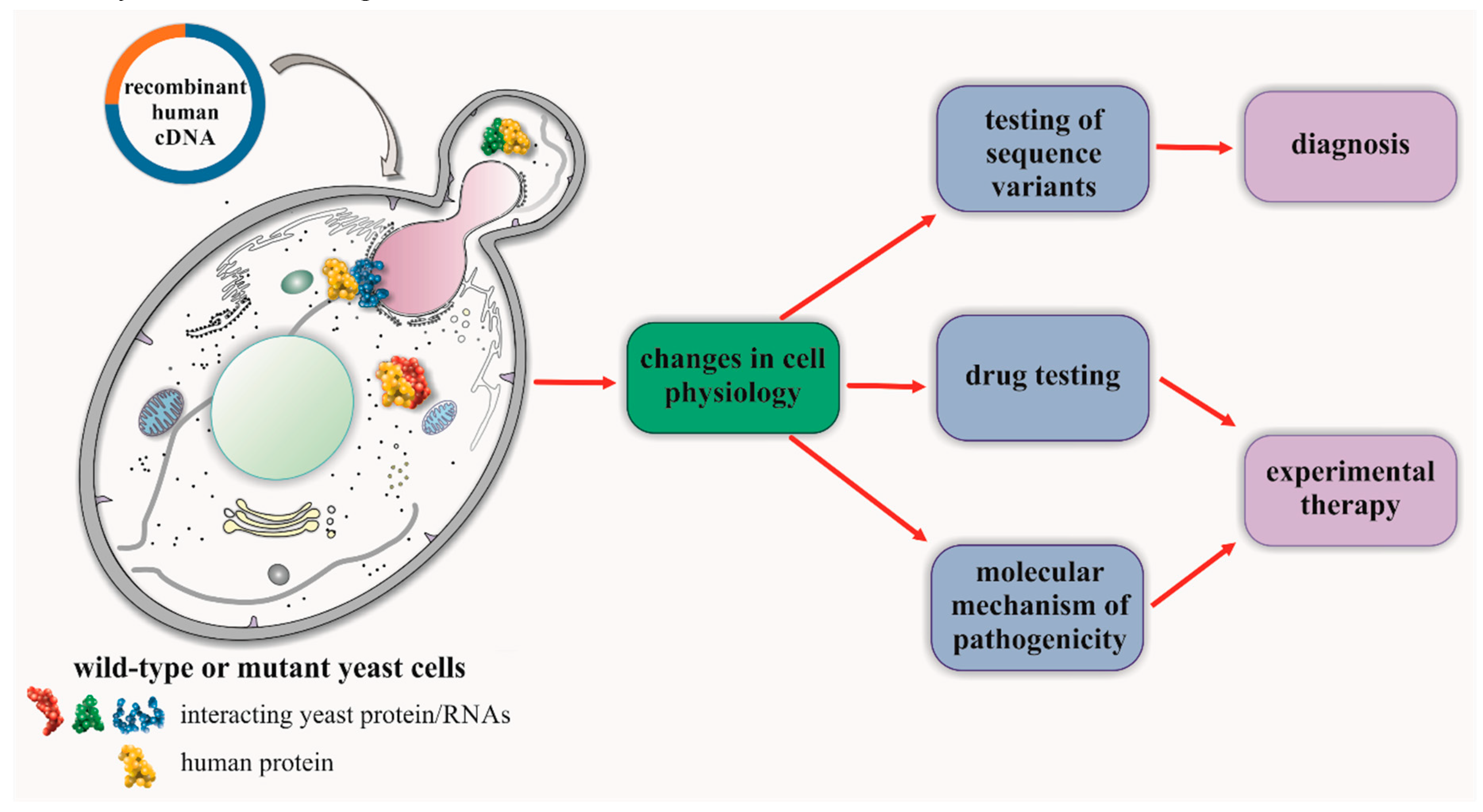

4. Studies of CMT in Yeast-Based Models for Human Genes with Yeast Orthologs

5. Studies of CMT for Human Genes Lacking Orthologs in the Yeast Model

6. Repositioning of Drugs in Hereditary Neuropathies

7. Outlook

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pipis, M.; Rossor, A.M.; Laura, M.; Reilly, M.M. Next-generation sequencing in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: Opportunities and challenges. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skre, H. Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth’s disease. Clin. Genet. 1974, 6, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto, L.C.L.S.; Oliveira, F.S.; Nunes, P.S.; Costa, I.M.P.D.F.; Garcez, C.A.; Goes, G.M.; Neves, E.L.A.; Quintans, J.S.; Araújo, A.A.D.S. Epidemiologic Study of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Systematic Review. Neuroepidemiology 2016, 46, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurá, M.; Pipis, M.; Rossor, A.M.; Reilly, M.M. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and related disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2019, 32, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussy, G.; Levy, G. Sept cas d’une maladie familiale particuliere: Troubles de la marche, pieds bots et aréflexie tendineuse généralisée, avec, accessoirement, légere maladresse des mains. Rev. Neurol. (Paris) 1926, 1, 427–450. [Google Scholar]

- Lupski, J.R.; Oca-Luna, R.M.; Slaugenhaupt, S.; Pentao, L.; Guzzetta, V.; Trask, B.J.; Saucedo-Cardenas, O.; Barker, D.F.; Killian, J.M.; Garcia, C.A.; et al. DNA duplication associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Cell 1991, 66, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, V.; Nelis, E.; Van Hul, W.; Nieuwenhuijsen, B.; Chen, K.; Wang, S.; Ben Othman, K.; Cullen, B.; Leach, R.; Hanemann, C.O.; et al. The peripheral myelin protein gene PMP–22 is contained within the Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 1A duplication. Nat. Genet. 1992, 1, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, V.; Bundy, B.; Reilly, M.M.; Pareyson, D.; Bacon, C.; Burns, J.; Day, J.; Feely, S.; Finkel, R.S.; Grider, T.; et al. CMT subtypes and disease burden in patients enrolled in the Inherited Neuropathies Consortium natural history study: A cross-sectional analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2014, 86, 873–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrupi, A.N.; Brewer, M.H.; Nicholson, G.A.; Kennerson, M.L. Structural variations causing inherited peripheral neuropathies: A paradigm for understanding genomic organization, chromatin interactions, and gene dysregulation. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2018, 6, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacArthur, D.G.; Manolio, T.A.; Dimmock, D.; Rehm, H.L.; Shendure, J.; Abecasis, G.R.; Adams, D.R.; Altman, R.B.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Ashley, E.A.; et al. Guidelines for investigating causality of sequence variants in human disease. Nature 2014, 508, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.M.; Moran, J.; Fromer, M.; Ruderfer, D.M.; Solovieff, N.; Roussos, P.; O’Dushlaine, C.; Chambert, K.; Bergen, S.E.; Kahler, A.; et al. A polygenic burden of rare disruptive mutations in schizophrenia. Nature 2014, 506, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathe, E.; Olivier, M.; Kato, S.; Ishioka, C.; Hainaut, P.; Tavtigian, S.V. Computational approaches for predicting the biological effect of p53 missense mutations: A comparison of three sequence analysis based methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 1317–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.A.; Duraisamy, S.; Miller, P.J.; Newell, J.A.; McBride, C.; Bond, J.P.; Raevaara, T.; Ollila, S.; Nyström, M.; Grimm, A.J.; et al. Interpreting missense variants: Comparing computational methods in human disease genes CDKN2A, MLH1, MSH2, MECP2, and tyrosinase (TYR). Hum. Mutat. 2007, 28, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cline, M.S.; Karchin, R. Using bioinformatics to predict the functional impact of SNVs. Bioinformatics 2010, 27, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thusberg, J.; Olatubosun, A.; Vihinen, M. Performance of mutation pathogenicity prediction methods on missense variants. Hum. Mutat. 2011, 32, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellana, S.; Mazza, T. Congruency in the prediction of pathogenic missense mutations: State-of-the-art web-based tools. Briefings Bioinform. 2013, 14, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froussios, K.; Iliopoulos, C.; Schlitt, T.; Simpson, M.A. Predicting the functional consequences of non-synonymous DNA sequence variants—Evaluation of bioinformatics tools and development of a consensus strategy. Genomics 2013, 102, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saporta, A.S.; Sottile, S.L.; Miller, L.J.; Feely, S.M.; Siskind, C.E.; Shy, M.E. Charcot-marie-tooth disease subtypes and genetic testing strategies. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizzardo, M.; Simone, C.; Rizzo, F.; Salani, S.; Dametti, S.; Rinchetti, P.; Del Bo, R.; Foust, K.; Kaspar, B.K.; Bresolin, N.; et al. Gene therapy rescues disease phenotype in a spinal muscular atrophy with respiratory distress type 1 (SMARD1) mouse model. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shababi, M.; Feng, Z.; Villalon, E.; Sibigtroth, C.M.; Osman, E.; Miller, M.R.; Williams-Simon, P.A.; Lombardi, A.; Sass, T.H.; Atkinson, A.K.; et al. Rescue of a Mouse Model of Spinal Muscular Atrophy With Respiratory Distress Type 1 by AAV9-IGHMBP2 Is Dose Dependent. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiza, N.; Georgiou, E.; Kagiava, A.; Médard, J.-J.; Richter, J.; Tryfonos, C.; Sargiannidou, I.; Heslegrave, A.J.; Rossor, A.M.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Gene replacement therapy in a model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth 4C neuropathy. Brain 2019, 142, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerath, N.U.; Shy, M.E. Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies: Understanding molecular pathogenesis could lead to future treatment strategies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1852, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passage, E.; Norreel, J.C.; Noack-Fraissignes, P.; Sanguedolce, V.; Pizant, J.; Thirion, X.; Robaglia-Schlupp, A.; Pellissier, J.F.; Fontes, M. Ascorbic acid treatment corrects the phenotype of a mouse model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu Hörste, G.M.; Prukop, T.; Liebetanz, D.; Möbius, W.; Nave, K.-A.; Sereda, M.W. Antiprogesterone therapy uncouples axonal loss from demyelination in a transgenic rat model of CMT1A neuropathy. Ann. Neurol. 2007, 61, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareyson, D.; Reilly, M.M.; Schenone, A.; Fabrizi, G.M.; Cavallaro, T.; Santoro, L.; Vita, G.; Quattrone, A.; Padua, L.; Gemignani, F.; et al. Ascorbic acid in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A (CMT-TRIAAL and CMT-TRAUK): A double-blind randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiepura, A.J.; Kochański, A. Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 1A drug therapies: Role of adenylyl cyclase activity and G-protein coupled receptors in disease pathomechanism. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. 2018, 78, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PXT3003 Improves Clinical Outcomes and Stabilizes Disease Progression in CMT1A Patients, Extension Study Shows. Available online: https://charcot-marie-toothnews.com/2020/01/17/pxt3003-continues-to-improve-clinical-outcomes-and-stabilize-disease-progression-in-cmt1a-patients/2020 (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Addex Announces Positive Data with ADX71441 in a Pre-Clinical Transgenic Model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth 1A Disease. 2020. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/fr/news-release/2013/01/07/1591975/0/en/Addex-Announces-Positive-Data-with-ADX71441-in-a-Pre-Clinical-Transgenic-Model-of-Charcot-Marie-Tooth-1A-Disease.html (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Kalinichev, M.; Girard, F.; Haddouk, H.; Rouillier, M.; Riguet, E.; Royer-Urios, I.; Mutel, V.; Lütjens, R.; Poli, S. The drug candidate, ADX71441, is a novel, potent and selective positive allosteric modulator of the GABAB receptor with a potential for treatment of anxiety, pain and spasticity. Neuropharmacology 2017, 114, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Damle, S.; Ikeda-Lee, K.; Kuntz, S.; Li, J.; Mohan, A.; Kim, A.; Hung, G.; Scheideler, M.A.; Scherer, S.S.; et al. PMP22 antisense oligonucleotides reverse Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A features in rodent models. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 128, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, S.S.; Wrabetz, L. Molecular mechanisms of inherited demyelinating neuropathies. Glia 2008, 56, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, S.S.; Xu, Y.-T.; Messing, A.; Willecke, K.; Fischbeck, K.H.; Jeng, L.J.B. Transgenic Expression of Human Connexin32 in Myelinating Schwann Cells Prevents Demyelination in Connexin32-Null Mice. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 1550–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagiava, A.; Sargiannidou, I.; Theophilidis, G.; Karaiskos, C.; Richter, J.; Bashiardes, S.; Schiza, N.; Nearchou, M.; Christodoulou, C.; Scherer, S.S.; et al. Intrathecal gene therapy rescues a model of demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2421–E2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, M.; Inoue, K.; Wiszniewski, W.; Ohyama, T.; Snipes, G.J.; Lupski, J.R. Curcumin Treatment Abrogates Endoplasmic Reticulum Retention and Aggregation-Induced Apoptosis Associated with Neuropathy-Causing Myelin Protein Zero-Truncating Mutants. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 77, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzkó, A.; Bai, Y.; Saporta, M.A.; Katona, I.; Wu, X.; Vizzuso, M.; Feltri, M.L.; Wang, S.; Dillon, L.; Kamholz, J.; et al. Curcumin derivatives promote Schwann cell differentiation and improve neuropathy in R98C CMT1B mice. Brain 2012, 135, 3551–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Patzkó, A.; Shy, M.E. Unfolded protein response, treatment and CMT1B. Rare Dis. 2013, 1, e24049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Das, I.; Krzyzosiak, A.; Schneider, K.; Wrabetz, L.; D’Antonio, M.; Barry, N.; Sigurdardottir, A.G.; Bertolotti, A. Preventing proteostasis diseases by selective inhibition of a phosphatase regulatory subunit. Science 2015, 348, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, A.G.; Franco, A.; Krezel, A.M.; Rumsey, J.M.; Alberti, J.M.; Knight, W.C.; Biris, N.; Zacharioudakis, E.; Janetka, J.W.; Baloh, R.H.; et al. MFN2 agonists reverse mitochondrial defects in preclinical models of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A. Science 2018, 360, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morena, J.; Gupta, A.; Hoyle, J.C. Charcot-Marie-Tooth: From Molecules to Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnhammer, E.; Östlund, G. InParanoid 8: Orthology analysis between 273 proteomes, mostly eukaryotic. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 43, D234–D239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypek, M.S.; Nash, R.S.; Wong, E.D.; MacPherson, K.A.; Hellerstedt, S.T.; Engel, S.R.; Karra, K.; Weng, S.; Sheppard, T.K.; Binkley, G.; et al. Saccharomyces genome database informs human biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D736–D742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, J.M.; Young, J.H.; Kachroo, A.H.; Salemi, M. Efforts to make and apply humanized yeast. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2015, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Yang, F.; Tan, G.; Costanzo, M.; Oughtred, R.; Hirschman, J.; Theesfeld, C.L.; Bansal, P.; Sahni, N.; Yi, S.; et al. An extended set of yeast-based functional assays accurately identifies human disease mutations. Genome Res. 2016, 26, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunham, M.J.; Fowler, D.M. Contemporary, yeast-based approaches to understanding human genetic variation. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2013, 23, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weterman, M.A.J.; Kuo, M.; Kenter, S.B.; Gordillo, S.; Karjosukarso, D.W.; Takase, R.; Bronk, M.; Oprescu, S.; Van Ruissen, F.; Witteveen, R.J.W.; et al. Hypermorphic and hypomorphic AARS alleles in patients with CMT2N expand clinical and molecular heterogeneities. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 4036–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ripmaster, T.L.; Shiba, K.; Schimmel, P. Wide cross-species aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase replacement in vivo: Yeast cytoplasmic alanine enzyme replaced by human polymyositis serum antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 4932–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.S.; Gitlin, J.D. Functional Expression of the Menkes Disease Protein Reveals Common Biochemical Mechanisms Among the Copper-transporting P-type ATPases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 3765–3770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-W.; Miao, Y.-H.; Chang, Y.-S. Control of lipid droplet size in budding yeast requires the collaboration between Fld1 and Ldb16. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 1214–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glerum, D.M.; Tzagoloff, A. Isolation of a human cDNA for heme A:farnesyltransferase by functional complementation of a yeast cox10 mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 8452–8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valnot, I.; Von Kleist-Retzow, J.-C.; Barrientos, A.; Gorbatyuk, M.S.; Taanman, J.-W.; Mehaye, B.; Rustin, P.; Tzagoloff, A.; Munnich, A.; Rötig, A. A mutation in the human heme A:farnesyltransferase gene (COX10 ) causes cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavadini, P.; Gellera, C.; Patel, P.; Isaya, G. Human frataxin maintains mitochondrial iron homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 2523–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.-I.; Chen, Y.-W.; Wu, Y.-H.; Chang, C.-Y.; Wang, T.-L.; Wang, C.-C. Functional Substitution of a Eukaryotic Glycyl-tRNA Synthetase with an Evolutionarily Unrelated Bacterial Cognate Enzyme. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vester, A.; Velez-Ruiz, G.; McLaughlin, H.M.; Program, N.C.S.; Lupski, J.R.; Talbot, K.; Vance, J.M.; Züchner, S.; Roda, R.H.; Fischbeck, K.H.; et al. A loss-of-function variant in the human histidyl-tRNA synthetase (HARS) gene is neurotoxic in vivo. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 34, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimon, M.; Baets, J.; Almeida-Souza, L.; De Vriendt, E.; Nikodinović, J.; Parman, Y.; Battaloǧlu, E.; Matur, Z.; Guergueltcheva, V.; Tournev, I.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in HINT1 cause axonal neuropathy with neuromyotonia. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1080–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachroo, A.H.; Laurent, J.M.; Yellman, C.M.; Meyer, A.; Wilke, C.O.; Salemi, M. Systematic humanization of yeast genes reveals conserved functions and genetic modularity. Science 2015, 348, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamza, A.; Tammpere, E.; Kofoed, M.; Keong, C.; Chiang, J.; Giaever, G.; Nislow, C.; Hieter, P. Complementation of Yeast Genes with Human Genes as an Experimental Platform for Functional Testing of Human Genetic Variants. Genetics 2015, 201, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, A.; Morano, K. SYM1 Is the Stress-Induced Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ortholog of the Mammalian Kidney Disease Gene Mpv17 and Is Required for Ethanol Metabolism and Tolerance during Heat Shock. Eukaryot. Cell 2004, 3, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolli, C.; Goffrini, P.; Lazzaretti, M.; Zanna, C.; Vitale, R.; Lodi, T.; Baruffini, E. Validation of a MGM1/OPA1 chimeric gene for functional analysis in yeast of mutations associated with dominant optic atrophy. Mitochondrion 2015, 25, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Kachroo, A.H.; Yellman, C.M.; Salemi, M.; Johnson, K.A. Yeast Cells Expressing the Human Mitochondrial DNA Polymerase Reveal Correlations between Polymerase Fidelity and Human Disease Progression. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 5970–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Kanekura, K.; Levine, T.P.; Kohno, K.; Olkkonen, V.M.; Aiso, S.; Matsuoka, M. ALS-linked P56S-VAPB, an aggregated loss-of-function mutant of VAPB, predisposes motor neurons to ER stress-related death by inducing aggregation of co-expressed wild-type VAPB. J. Neurochem. 2009, 108, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takata, T.; Kimura, Y.; Ohnuma, Y.; Kawawaki, J.; Kakiyama, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Kakizuka, A. Rescue of growth defects of yeast cdc48 mutants by pathogenic IBMPFD-VCPs. J. Struct. Biol. 2012, 179, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wakasugi, K.; Quinn, C.L.; Tao, N.; Schimmel, P. Genetic code in evolution: Switching species-specific aminoacylation with a peptide transplant. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermann, K.; Gess, B.; Hausler, M.; Weiß, J.; Hahn, A.; Kurth, I. Hereditary Neuropathies. Dtsch. Aerzteblatt Online 2018, 115, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GeneCards. Available online: http://www.genecards.org/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Penkett, C.J.; Morris, J.A.; Wood, V.; Bahler, J. YOGY: A web-based, integrated database to retrieve protein orthologs and associated Gene Ontology terms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W330–W334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniprot Data Base. Available online: http://www.uniprot.org/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man OMIM. Available online: https://omim.org/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Wallen, R.C.; Antonellis, A. To charge or not to charge: Mechanistic insights into neuropathy-associated tRNA synthetase mutations. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2013, 23, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonellis, A.; Ellsworth, R.E.; Sambuughin, N.; Puls, I.; Abel, A.; Lee-Lin, S.-Q.; Jordanova, A.; Kremensky, I.; Christodoulou, K.; Middleton, L.T.; et al. Glycyl tRNA Synthetase Mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 2D and Distal Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type V. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003, 72, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordanova, A.; Irobi, J.; Thomas, F.P.; Van Dijck, P.; Meerschaert, K.; Dewil, M.; Dierick, I.; Jacobs, A.; De Vriendt, E.; Guergueltcheva, V.; et al. Disrupted function and axonal distribution of mutant tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase in dominant intermediate Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latour, P.; Thauvin-Robinet, C.; Baudelet-Méry, C.; Soichot, P.; Cusin, V.; Faivre, L.; Locatelli, M.-C.; Mayençon, M.; Sarcey, A.; Broussolle, E.; et al. A Major Determinant for Binding and Aminoacylation of tRNAAla in Cytoplasmic Alanyl-tRNA Synthetase Is Mutated in Dominant Axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 86, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.; McLaughlin, H.; Houlden, H.; Guo, M.; Yo-Tsen, L.; Hadjivassilious, M.; Speziani, F.; Yang, X.-L.; Antonellis, A.; Reilly, M.M.; et al. Exome sequencing identifies a significant variant in methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MARS) in a family with late-onset CMT2. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2013, 84, 1247–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-C.; Soong, B.-W.; Mademan, I.; Huang, Y.-H.; Liu, C.-R.; Hsiao, C.-T.; Wu, H.-T.; Liu, T.-T.; Liu, Y.-T.; Tseng, Y.-T.; et al. A recurrent WARS mutation is a novel cause of autosomal dominant distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Brain 2017, 140, 1252–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrower, T.; Stewart, J.D.; Hudson, G.; Houlden, H.; Warner, G.; O’Donovan, D.G.; Findlay, L.J.; Taylor, R.W.; De Silva, R.; Chinnery, P.F. POLG1 Mutations Manifesting as Autosomal Recessive Axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2008, 65, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruffini, E.; Lodi, T.; Dallabona, C.; Puglisi, A.; Zeviani, M.; Ferrero, I. Genetic and chemical rescue of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae phenotype induced by mitochondrial DNA polymerase mutations associated with progressive external ophthalmoplegia in humans. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 2846–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruffini, E.; Ferrero, I.; Foury, F. Mitochondrial DNA defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae caused by functional interactions between DNA polymerase gamma mutations associated with disease in human. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1772, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Baruffini, E.; Horvath, R.; Dallabona, C.; Czermin, B.; Lamantea, E.; Bindoff, L.A.; Invernizzi, F.; Ferrero, I.; Zeviani, M.; Lodi, T. Predicting the contribution of novel POLG mutations to human disease through analysis in yeast model. Mitochondrion 2011, 11, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruffini, E.; Ferrari, J.; Dallabona, C.; Donnini, C.; Lodi, T. Polymorphisms in DNA polymerase γ affect the mtDNA stability and the NRTI-induced mitochondrial toxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mitochondrion 2014, 20, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodi, T.; Dallabona, C.; Nolli, C.; Goffrini, P.; Donnini, C.; Baruffini, E. DNA polymerase γ and disease: What we have learned from yeast. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, G.R.; Santos, J.H.; Strand, M.K.; Van Houten, B.; Copeland, W.C. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae with mutations in DNA polymerase γ associated with progressive external ophthalmoplegia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 15, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliszewska, M.; Kruszewski, J.; Kierdaszuk, B.; Kostera-Pruszczyk, A.; Nojszewska, M.; Łusakowska, A.; Vizueta, J.; Sabat, D.; Lutyk, D.; Lower, M.; et al. Yeast model analysis of novel polymerase gamma variants found in patients with autosomal recessive mitochondrial disease. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 134, 951–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuppia, G.; Rizzo, F.; Riboldi, G.; Del Bo, R.; Nizzardo, M.; Simone, C.; Comi, G.P.; Bresolin, N.; Corti, S. MFN2-related neuropathies: Clinical features, molecular pathogenesis and therapeutic perspectives. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 356, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filadi, R.; Pendin, D.; Pizzo, P. Mitofusin 2: From functions to disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiott, E.A.; Cohen, M.M.; Saint-Georges-Chaumet, Y.; Weissman, A.M.; Shaw, J.M. A Mutation Associated with CMT2A Neuropathy Causes Defects in Fzo1 GTP Hydrolysis, Ubiquitylation, and Protein Turnover. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 5026–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallese, F.; Barazzuol, L.; Maso, L.; Brini, M.; Calí, T. ER-Mitochondria Calcium Transfer, Organelle Contacts and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1131, 719–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mario, A.; Quintana-Cabrera, R.; Martinvalet, D.; Giacomello, M. (Neuro) degenerated Mitochondria-ER contacts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 483, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erpapazoglou, Z.; Mouton-Liger, F.; Corti, O. From dysfunctional endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling to neurodegeneration. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 109, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krols, M.; Van Isterdael, G.; Asselbergh, B.; Kremer, A.; Lippens, S.; Timmerman, V.; Janssens, S. Mitochondria-associated membranes as hubs for neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rzepnikowska, W.; Flis, K.; Muñoz-Braceras, S.; Menezes, R.; Escalante, R.; Zoladek, T. Yeast and other lower eukaryotic organisms for studies of Vps13 proteins in health and disease. Traffic 2017, 18, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Suaga, P.; Paillusson, S.; Stoica, R.; Noble, W.; Hanger, D.P.; Miller, C.C.J. The ER-Mitochondria Tethering Complex VAPB-PTPIP51 Regulates Autophagy. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymański, J.; Janikiewicz, J.; Michalska, B.; Patalas-Krawczyk, P.; Perrone, M.; Ziółkowski, W.; Duszynski, J.; Pinton, P.; Dobrzyń, A.; Wieckowski, M.R. Interaction of Mitochondria with the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Plasma Membrane in Calcium Homeostasis, Lipid Trafficking and Mitochondrial Structure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, T.; Kim, Y.J.; Alvarez-Prats, A.; Pemberton, J. Lipid Dynamics at Contact Sites between the Endoplasmic Reticulum and Other Organelles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 35, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sánchez, P.; Satrústegui, J.; Palau, F.; Del Arco, A. Calcium Deregulation and Mitochondrial Bioenergetics in GDAP1-Related CMT Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rencus-Lazar, S.; DeRowe, Y.; Adsi, H.; Gazit, E.; Laor, D. Yeast Models for the Study of Amyloid-Associated Disorders and Development of Future Therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffioen, G.; Duhamel, H.; Van Damme, N.; Pellens, K.; Zabrocki, P.; Pannecouque, C.; Van Leuven, F.; Winderickx, J.; Wera, S. A yeast-based model of α-synucleinopathy identifies compounds with therapeutic potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1762, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardiff, D.F.; Jui, N.T.; Khurana, V.; Tambe, M.A.; Thompson, M.L.; Chung, C.Y.; Kamadurai, H.; Kim, H.T.; Lancaster, A.K.; Caldwell, K.A.; et al. Yeast Reveal a “Druggable” Rsp5/Nedd4 Network that Ameliorates -Synuclein Toxicity in Neurons. Science 2013, 342, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dajas, F.; Rivera, F.; Blasina, F.; Arredondo, F.; Echeverry, C.; Lafon, L.; Morquio, A.; Heizen, H. Cell culture protection and in vivo neuroprotective capacity of flavonoids. Neurotox. Res. 2003, 5, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, C.Y.; Khurana, V.; Auluck, P.K.; Tardiff, D.F.; Mazzulli, J.R.; Soldner, F.; Baru, V.; Lou, Y.; Freyzon, Y.; Cho, S.; et al. Identification and Rescue of -Synuclein Toxicity in Parkinson Patient-Derived Neurons. Science 2013, 342, 983–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estela, A.; Pla-Martín, D.; Sánchez-Piris, M.; Sesaki, H.; Palau, F. Charcot-Marie-Tooth-related Gene GDAP1 Complements Cell Cycle Delay at G2/M Phase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae fis1 Gene-defective Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 36777–36786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rzepnikowska, W.; Kaminska, J.; Kabzińska, D.; Kochański, A. Pathogenic Effect of GDAP1 Gene Mutations in a Yeast Model. Genes 2020, 11, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, I.; Dina, G.; Tronchere, H.; Kaufman, E.; Chicanne, G.; Cerri, F.; Wrabetz, L.; Payrastre, B.; Quattrini, A.; Weisman, L.S.; et al. Genetic Interaction between MTMR2 and FIG4 Phospholipid Phosphatases Involved in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Neuropathies. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Antonio, M.; Musner, N.; Scapin, C.; Ungaro, D.; Del Carro, U.; Ron, D.; Feltri, M.L.; Wrabetz, L. Resetting translational homeostasis restores myelination in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1B mice. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 821–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, H.P.; Novoa, I.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Wek, R.; Schapira, M.; Ron, D. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, N.C.; Ekins, S.; Williams, A.J.; Tropsha, A. A bibliometric review of drug repurposing. Drug Discov. Today 2018, 23, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rak, M.; Tetaud, E.; Godard, F.; Sagot, I.; Salin, B.; Duvezin-Caubet, S.; Slonimski, P.P.; Rytka, J.; Di Rago, J.-P. Yeast Cells Lacking the Mitochondrial Gene Encoding the ATP Synthase Subunit 6 Exhibit a Selective Loss of Complex IV and Unusual Mitochondrial Morphology. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 10853–10864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rak, M.; Tetaud, E.; Duvezin-Caubet, S.; Ezkurdia, N.; Bietenhader, M.; Rytka, J.; Di Rago, J.-P. A Yeast Model of the Neurogenic Ataxia Retinitis Pigmentosa (NARP) T8993G Mutation in the Mitochondrial ATP Synthase-6 Gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 34039–34047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwimmer, C.; Rak, M.; Lefebvre-Legendre, L.; Duvezin-Caubet, S.; Plane, G.; Di Rago, J.-P. Yeast models of human mitochondrial diseases: From molecular mechanisms to drug screening. Biotechnol. J. 2006, 1, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.V.; Vilaça, R.; Costa, V.; Menezes, R.; Santos, C. Exploring the power of yeast to model aging and age-related neurodegenerative disorders. Biogerontology 2016, 18, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soma, S.; Latimer, A.J.; Chun, H.; Vicary, A.C.; Timbalia, S.A.; Boulet, A.; Rahn, J.J.; Chan, S.S.L.; Leary, S.; Kim, B.-E.; et al. Elesclomol restores mitochondrial function in genetic models of copper deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8161–8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGary, K.L.; Park, T.J.; Woods, J.O.; Cha, H.J.; Wallingford, J.B.; Salemi, M. Systematic discovery of nonobvious human disease models through orthologous phenotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6544–6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, B. Genotype to phenotype: Lessons from model organisms for human genetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 14, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genes Complementing Yeast S. cerevisiae Orthologs Mutation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Gene | Yeast Gene | Function of the Protein | Comments | Source |

| AARS | ALA1 | Alanyl-tRNA synthetase | Wild-type AARS improved some yeast growth at 30 °C but more robustly at 37 °C [45] | [46] |

| ATP7A | CCC2 | Copper-transporting P-type ATPase | [47] | |

| BSCL2 | SEI1 | Seipin: necessary for correct lipid storage and lipid droplets maintenance | Complements the defects in lipid droplets in sei1Δ strain | [48] |

| COX10 | COX10 | Heme A:farnesyltransferase; functions in the maturation of the heme A, a prosthetic group of COX complex | [49,50] | |

| FXN | YFH1 | Frataxin: a component of a multiprotein complex that assembles iron–sulfur (Fe–S) clusters in the mitochondrial matrix | [51] | |

| GARS | GRS1 | Glycyl-tRNA synthetase | [52] | |

| HARS | HTS1 | Histidyl-tRNA synthetase | [53] | |

| HINT1 | HNT1 | Hydrolyzes purine nucleotide phosphoramidates with a single phosphate group | [54] | |

| HMBS | HEM3 | Hydroxymethylbilane synthase: the third enzyme of the heme biosynthetic pathway | [55,56] | |

| MPV17 | SYM1 | An inner-membrane mitochondrial protein; may form a channel in the inner mitochondrial membrane, supplying the matrix with desoxynucleotide phosphates and/or nucleotide precursors | [57] | |

| OPA1 | MGM1 | Dynamin-related GTPase that is essential for normal mitochondrial morphology by regulating the mitochondrial fusion | OPA1 cannot substitute the MGM1 gene; however, chimeric protein composed of the N-terminal region of Mgm1 fused with the catalytic region of OPA1 is able to complement the mgm1 null mutant | [58] |

| POLG | MIP1 | Mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma | The yeast mitochondrial localization signal was retained | [59] |

| VAPB | SCS22 SCS2 | A type IV membrane protein found in plasma and intracellular vesicle membranes | Expression of VAPB partially compensated for the inositol auxotrophy scs2Δscs22Δ yeast strain | [60] |

| VCP | CDC48 | A member of the AAA ATPase family of proteins; plays a role in protein degradation, intracellular membrane fusion, DNA repair and replication, regulation of the cell cycle, and activation of the NF-kappa B pathway | Wild type VCP partially suppressed the temperature sensitivity growth of cdc48-3 but not the cold sensitivity growth of cdc48-1 and null mutation | [61] |

| YARS | TYS1 | Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase | [62] | |

| Genes Possessing Orthologs in Yeast S. cerevisiae | ||||

| Human Gene | Yeast Gene | Protein Function | ||

| ABCA1 | YOL075C | A member of the superfamily of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters | ||

| AIMP1 | ARC1 | A multifunctional polypeptide with both cytokine and tRNA-binding activities | ||

| ATP1A1 | ENA5 ENA1 ENA2 | Catalytic component of the active enzyme, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of ATP coupled with the exchange of sodium and potassium ions across the plasma membrane | ||

| C12ORF65 | RSO55 | A mitochondrial matrix protein that appears to contribute to peptide chain termination in the mitochondrial translation machinery | ||

| CCT5 | CCT5 | A molecular chaperone that is a member of the chaperonin containing TCP1 complex (CCT), also known as the TCP1 ring complex (TRiC) | ||

| CHCHD10 | MIX17 | A mitochondrial protein that is enriched at cristae junctions in the intermembrane space; it may play a role in cristae morphology maintenance or oxidative phosphorylation | ||

| CLP1 | CLP1 | A member of the Clp1 family; it is a multifunctional kinase which is a component of the tRNA splicing endonuclease complex and a component of the pre-mRNA cleavage complex II | ||

| CLTCL1 | CHC1 | The clathrin heavy chain protein | ||

| COX6A1 | COX13 | Cytochrome C oxidase subunit | ||

| CTDP1 | FCP1 | A protein which interacts with the carboxy-terminus of the RAP74 subunit of transcription initiation factor TFIIF, and functions as a phosphatase that dephosphorylates the C-terminus of POLR2A (a subunit of RNA polymerase II), making it available for initiation of gene expression | ||

| DCTN1 | NIP100 | The largest subunit of dynactin | ||

| DHTKD1 | KGD1 | A component of a mitochondrial 2-oxoglutarate-dehydrogenase-complex-like protein involved in the degradation pathways of several amino acids | ||

| DNAJB2 | JJJ3 | Almost exclusively expressed in the brain, mainly in the neuronal layers; encodes a protein that shows sequence similarity to bacterial DnaJ protein and the yeast ortholog | ||

| DYNC1H1 | DYN1 | Dynein cytoplasmic heavy chain; dyneins are a group of microtubule-activated ATPases that function as molecular motors | ||

| EGR2 | MIG2; MIG3; COM2 | A transcription factor | ||

| EXOSC3 | RRP40 | Non-catalytic component of the human exosome | ||

| EXOSC8 | RRP43 | A 3’-5’ exoribonuclease that specifically interacts with mRNAs containing AU-rich elements | ||

| FIG4 | FIG4 | Phosphoinositide 5-phosphatase | ||

| GMPPA | PSA1 | GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase | ||

| HK1 | HXK1 HXK2 GLK1 EMI2 | Hexokinase 1 | ||

| IGHMBP2 | HCS1 | Helicase superfamily member that binds a specific DNA sequence from the immunoglobulin mu chain switch region | ||

| ELP1 (IKBKAP) | IKI3 | Scaffold protein and a regulator for three different kinases involved in proinflammatory signaling | ||

| MARS | MES1 | Methionyl-tRNA synthetase | ||

| MCM3AP | SAC3 | Involved in the export of mRNAs to the cytoplasm through the nuclear pores, promoting somatic hypermutations | ||

| MFN2 | FZO1 | Mitofusin: participates in mitochondrial fusion | ||

| MT-ATP6 | ATP6 | Mitochondrial membrane ATP synthase | ||

| MYH14 | MYO1 | Member of the myosin superfamily | ||

| PDHA1 | PDA1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase subunit | ||

| PDK3 | PKP1 | One of the three pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases that inhibits the PDH complex by phosphorylation of the E1 alpha subunit | ||

| PEX12 | PEX12 | Belongs to the peroxin-12 family, proteins that are essential for the assembly of functional peroxisomes | ||

| PNKP | HNT3 | Involved in DNA repair | ||

| PRPS1 | PRS4 PRS2 PRS3 | Enzyme that catalyzes the phosphoribosylation of ribose 5-phosphate to 5-phosphoribosyl-1-pyrophosphate, which is necessary for purine metabolism and nucleotide biosynthesis | ||

| RAB7A | YPT7 | RAB family members, regulate vesicle traffic in the late endosomes and also from late endosomes to lysosomes | ||

| REEP1 | YOP1 | Mitochondrial protein that functions to enhance the cell surface expression of odorant receptors | ||

| SCO2 | SCO1 | One of the COX assembly factors | ||

| SEPT9 (SEPTIN9) | CDC10 CDC3 | Member of the septin family involved in cytokinesis and cell cycle control | ||

| SETX | SEN1 | Contains a DNA/RNA helicase domain at its C-terminal end which suggests that it may be involved in both DNA and RNA processing | ||

| SIGMAR1 | ERG2 | Receptor protein that interacts with a variety of psychotomimetic drugs, including cocaine and amphetamines | ||

| SLC25A19 | TPC1 | Mitochondrial transporter mediating uptake of thiamine pyrophosphate into mitochondria | ||

| SPTLC1 | LCB1 | The long chain base subunit 1 of serine palmitoyltransferase | ||

| SPTLC2 | LCB2 | Subunit of serine palmitoyltransferase | ||

| SURF1 | SHY1 | Localized to the inner mitochondrial membrane, involved in the biogenesis of the cytochrome c oxidase complex | ||

| TDP1 | TDP1 | Is involved in repairing stalled topoisomerase I-DNA complexes by catalyzing the hydrolysis of the phosphodiester bond between the tyrosine residue of topoisomerase I and the 3-prime phosphate of DNA | ||

| UBA1 | UBA1 | Catalyzes the first step in ubiquitin conjugation to mark cellular proteins for degradation | ||

| WARS | WRS1 | Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase | ||

| Process | Gene | Protein Function |

|---|---|---|

| Adhesion | FBLN5 | Fibulin 5: extracellular matrix protein essential for elastic fiber formation; promotes adhesion of endothelial cells; may play a role in vascular development and remodeling |

| Apoptosis | AIFM1 | Flavoprotein essential for nuclear disassembly in apoptotic cells, and found in the mitochondrial intermembrane space in healthy cells |

| Autophagy | RETREG1 (FAM134B) | Endoplasmic reticulum-anchored autophagy receptor that mediates ER delivery into lysosomes through sequestration into autophagosomes |

| TECPR2 | Implicated in autophagy | |

| Cytoskeleton organization | DST | Dystonin: cytoskeletal linker protein |

| FGD4 | Activates CDC42 by GDP/GTP exchange; binds to actin filaments; is involved in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton and cell shape | |

| GSN | Gelsolin: calcium-regulated protein functions in both assembly and disassembly of actin filaments | |

| INF2 | A member of the formin family: severs actin filaments and regulates their polymerization and depolymerization | |

| MICAL1 | Monooxygenase that oxidizes methionine residues on actin, thereby promoting depolymerization of actin filaments | |

| NEFH | Neurofilament heavy polypeptide | |

| NEFL | Neurofilament light polypeptide | |

| TUBB3 | A class III member of the beta tubulin protein family | |

| Endoplasmic reticulum organization | ATL1 | Alastin 1: GTPase functions in endoplasmic reticulum tubular network biogenesis |

| ATL2 | Atlastin 2: GTPase functions in formation of endoplasmic reticulum | |

| ATL3 | Alastin 3: dynamin-like GTPase required for the proper formation of the endoplasmic reticulum tubules | |

| ARL6IP1 | Transmembrane protein: plays a role in the formation and stabilization of endoplasmic reticulum tubules; negatively regulates apoptosis; regulates glutamate transport | |

| Mitochondria functioning | TWNK (C10ORF2) | DNA helicase: involved in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) metabolism |

| GDAP1 | Regulates mitochondrial morphology and transport; participates in calcium homeostasis; regulates redox state of cell | |

| NDUFAF5 | Mitochondrial protein required for complex I assembly | |

| SLC25A46 | Functions in promoting mitochondrial fission, and prevents the formation of hyperfilamentous mitochondria | |

| Myelination | ARHGEF10 | A Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) |

| CNTNAP1 | Required for radial and longitudinal organization of myelinated axons | |

| DRP2 | Dystrophin-related protein 2: required for normal myelination and for normal organization of the cytoplasm and the formation of Cajal bands in myelinating Schwann cells | |

| FAM126A | Hyccin: Component of a complex regulating phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate; may play a part in the beta-catenin/Lef signaling pathway | |

| MPZ | Specifically expressed in Schwann cells of the peripheral nervous system; a type I transmembrane glycoprotein that is a major structural protein of the peripheral myelin sheath | |

| PLP1 | A transmembrane protein that is the predominant component of myelin | |

| PMP2 | Localizes to myelin sheaths of the peripheral nervous system; is thought to provide stability to the sheath | |

| PMP22 | An integral membrane protein that is a major component of myelin in the peripheral nervous system | |

| PRX | A protein involved in peripheral nerve myelin upkeep | |

| SH3TC2 | Expressed in Schwann cells: interacts with the small guanosine triphosphatase Rab11, which is known to regulate the recycling of internalized membranes and receptors back to the cell surface | |

| Lipid metabolism | ABHD12 | Catalyzes the hydrolysis of 2-arachidonoyl glycerol (2-AG), the main endocannabinoid lipid transmitter that acts on cannabinoid receptors |

| ASAH1 | Acid ceramidase: a lysosomal protein that hydrolyzes sphingolipid ceramides | |

| CYP27A1 | Sterol 26-hydroxylase: cytochrome P450 monooxygenase that catalyzes hydroxylation of cholesterol and its derivatives | |

| DGAT2 | Diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 2: one of two enzymes which catalyzes the final reaction in the synthesis of triglycerides | |

| GALC | Galactocerebrosidase: a lysosomal protein which hydrolyzes the galactose ester bonds of galactosylceramide, galactosylsphingosine, lactosylceramide, and monogalactosyldiglyceride | |

| GLA | Alpha-galactosidase A: hydrolyses the terminal alpha-D-galactosyl moieties from glycolipids and glycoproteins | |

| HADHA | The alpha subunit of the mitochondrial trifunctional protein, which catalyzes the last three steps of mitochondrial beta-oxidation of long chain fatty acids | |

| HADHB | The beta subunit of the mitochondrial trifunctional protein, which catalyzes the last three steps of mitochondrial beta-oxidation of long chain fatty acids | |

| HEXA | Beta-hexosaminidase subunit alpha: involved in degradation of GM2 gangliosides, and other molecules containing terminal N-acetyl hexosamines | |

| MTMR2 | Member of the myotubularin family of phosphoinositide lipid phosphatases: possesses phosphatase activity towards phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate and phosphatidylinositol-3,5-bisphosphate | |

| PLA2G6 | A2 phospholipase | |

| Protein processing | BAG3 | Co-chaperone for HSP70 and HSC70 chaperone proteins: acts as a nucleotide-exchange factor (NEF) promoting the release of substrate |

| DCAF8 | Interacts with the Cul4-Ddb1 E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase complex; may function as a substrate receptor | |

| DNAJC3 | Acts as a co-chaperone of BiP, a major endoplasmic reticulum-localized member of the HSP70 family of molecular chaperones that promote normal protein folding | |

| FBXO38 | Substrate recognition component of a SCF (SKP1-CUL1-F-box protein) E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase complex | |

| GAN | Gigaxonin: plays a role in neurofilament architecture and is involved in mediating the ubiquitination and degradation of some proteins | |

| HSPB1 | A member of the small heat shock protein (HSP20) family: plays a role in stress resistance and actin organization | |

| HSPB3 | A member of the small heat shock protein (HSP20) family: inhibitor of actin polymerization | |

| HSPB8 | Belongs to the superfamily of small heat-shock proteins (HSP20): displays temperature-dependent chaperone activity | |

| KLHL13 | Functions as an adaptor protein of a BCR (BTB-CUL3-RBX1) E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase complex required for mitotic progression and cytokinesis | |

| LRSAM1 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase: involved in various functions | |

| MME | Neprilysin: membrane metalloendopeptidase | |

| RNF170 | RING domain-containing protein that resides in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane; functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase and mediates ubiquitination and processing of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors via the ER-associated protein degradation pathway | |

| SACS | Sacsin: co-chaperone which acts as a regulator of the Hsp70 chaperone | |

| SBF1 | Myotubularin-related protein: acts as an adapter for the phosphatase MTMR2; promotes the exchange of GDP to GTP | |

| TRIM2 | Functions as an E3-ubiquitin ligase: plays a neuroprotective function | |

| VRK1 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase | |

| WNK1 | Serine/threonine kinase which plays an important role in the regulation of electrolyte homeostasis, cell signaling, survival, and proliferation | |

| Signaling | ADCY6 | Belongs to the adenylate cyclase family of enzymes responsible for the synthesis of cAMP |

| AHNAK2 | Nucleoprotein: may play a role in calcium signaling | |

| DHH | Signaling molecules that play an important role in regulating morphogenesis | |

| GJB1 | Gap junction beta-1 protein: a member of the gap junction protein family | |

| GJB3 | Gap junction beta-3 protein: a member of the gap junction protein family | |

| GNB4 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G-protein) subunit beta 4; G proteins are involved as a modulator or transducer transmembrane signaling | |

| NDRG1 | Belongs to the alpha/beta hydrolase superfamily: a cytoplasmic protein involved in stress responses, hormone responses, cell growth, and differentiation; is necessary for p53-mediated caspase activation and apoptosis | |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor: nerve growth stimulating activity | |

| NTRK1 | High affinity nerve growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase: involved in the development and the maturation of the central and peripheral nervous systems | |

| STING1 (TMEM173) | Regulator of the innate immune response to viral and bacterial infections | |

| Gene expression and RNA processing | ANG | Angiogenin: a mediator of new blood vessel formation |

| ASCC1 | Subunit of the activating signal co-integrator 1 (ASC-1) complex: plays a role in DNA damage repair | |

| DNMT1 | DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1: methylates CpG residues | |

| FUS | Multifunctional protein involved in processes such as transcription regulation, RNA splicing, RNA transport, DNA repair and damage response; in neuronal cells, plays crucial roles in dendritic spine formation and stability, RNA transport, mRNA stability and synaptic homeostasis | |

| HNRNPA1 | Involved in mRNA metabolism and transport | |

| HOXD10 | Transcription factor which is part of a developmental regulatory system | |

| IFRD1 | Protein related to interferon-gamma: this protein may function as a transcriptional co-activator/repressor that controls the growth and differentiation of specific cell types during embryonic development and tissue regeneration | |

| LAS1L | Involved in the biogenesis of the 60S ribosomal subunit | |

| LITAF | Plays a role in endosomal protein trafficking and in targeting proteins for lysosomal degradation | |

| MED25 | Component of the transcriptional co-activator complex termed the Mediator complex, involved in the regulated transcription of nearly all RNA polymerase II-dependent genes | |

| MORC2 | Essential for epigenetic silencing by the HUSH (human silencing hub) complex | |

| PRDM12 | A transcriptional regulator of sensory neuronal specification that plays a critical role in pain perception | |

| RBM7 | RNA-binding subunit of the trimeric nuclear exosome targeting (NEXT) complex, a complex that functions as an RNA exosome cofactor that directs a subset of non-coding short-lived RNAs for exosomal degradation | |

| SOX10 | Transcription factor involved in developing and mature glia | |

| TARDBP | RNA-binding protein that is involved in various steps of RNA biogenesis and processing | |

| TRIP4 | Transcription co-activator, which associates with transcriptional coactivators, nuclear receptors and basal transcription factors | |

| ZNF106 | RNA-binding protein, required for normal expression and/or alternative splicing of a number of genes in the spinal cord and skeletal muscle | |

| Transport | ALS2 | Guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the small GTPase RAB5 |

| BICD2 | A member of the Bicoid family: implicated in dynein-mediated motility along microtubules | |

| DNM2 | Dynamin 2: microtubule-associated motor protein | |

| FLVCR1 | Heme transporter that exports cytoplasmic heme | |

| KIF1A | Member of the kinesin family and functions as an anterograde motor protein | |

| KIF1B | A motor protein that transports mitochondria and synaptic vesicles | |

| KIF5A | A member of the kinesin family of proteins: microtubule-dependent motor | |

| OPTN | Optineurin: plays a role in the maintenance of the Golgi complex, in membrane trafficking and exocytosis | |

| NIPA1 | Magnesium transporter | |

| PLEKHG5 | Functions as a guanine exchange factor (GEF) for RAB26 | |

| SH3BP4 | Is involved in cargo-specific control of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, specifically controlling the internalization of a specific protein receptor | |

| SLC5A7 | Sodium ion- and chloride ion-dependent high-affinity transporter that mediates choline uptake | |

| SCN10A | Tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated sodium channel | |

| SCN11A | Voltage-gated sodium channel | |

| SCN9A | Voltage-dependent sodium channel | |

| SLC12A6 | Potassium-chloride cotransporter | |

| SLC5A2 | Sodium-dependent glucose transport protein | |

| SLC5A3 | Myo-inositol transporter | |

| SPG11 | Spatacsin: involved in the endolysosomal system and autophagy | |

| SYT2 | Synaptic vesicle membrane protein: calcium sensor in vesicular trafficking and exocytosis | |

| TFG | Plays a role in the function of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and its associated microtubules | |

| TRPA1 | Receptor-activated non-selective cation channel involved in pain detection and possibly also in cold perception, oxygen concentration perception, cough, itch, and inner ear function | |

| TRPV4 | Non-selective calcium permeant cation channel involved in osmotic sensitivity and mechanosensitivity | |

| TTR | Transthyretin: one of the three prealbumins; is a carrier protein, which transports thyroid hormones in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid; is involved in the transport of retinol in the plasma | |

| Other | LMNA | The lamin family member: component of the nuclear lamina |

| PHYH | Phytanoyl-CoA hydroxylase | |

| NAGLU | Alpha-N-acetylglucosaminidase: degrades heparan sulfate | |

| TNNT2 | The tropomyosin-binding subunit of the troponin complex | |

| TYMP | An angiogenic factor which promotes angiogenesis and stimulates the in vitro growth of a variety of endothelial cells |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rzepnikowska, W.; Kaminska, J.; Kabzińska, D.; Binięda, K.; Kochański, A. A Yeast-Based Model for Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathies: A Simple System for Complex, Heterogeneous Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21124277

Rzepnikowska W, Kaminska J, Kabzińska D, Binięda K, Kochański A. A Yeast-Based Model for Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathies: A Simple System for Complex, Heterogeneous Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(12):4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21124277

Chicago/Turabian StyleRzepnikowska, Weronika, Joanna Kaminska, Dagmara Kabzińska, Katarzyna Binięda, and Andrzej Kochański. 2020. "A Yeast-Based Model for Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathies: A Simple System for Complex, Heterogeneous Diseases" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 12: 4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21124277

APA StyleRzepnikowska, W., Kaminska, J., Kabzińska, D., Binięda, K., & Kochański, A. (2020). A Yeast-Based Model for Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathies: A Simple System for Complex, Heterogeneous Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(12), 4277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21124277