Curcumin—A Viable Agent for Better Bladder Cancer Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Bladder Cancer

3. Complementary and Alternative Medicine

4. Curcumin

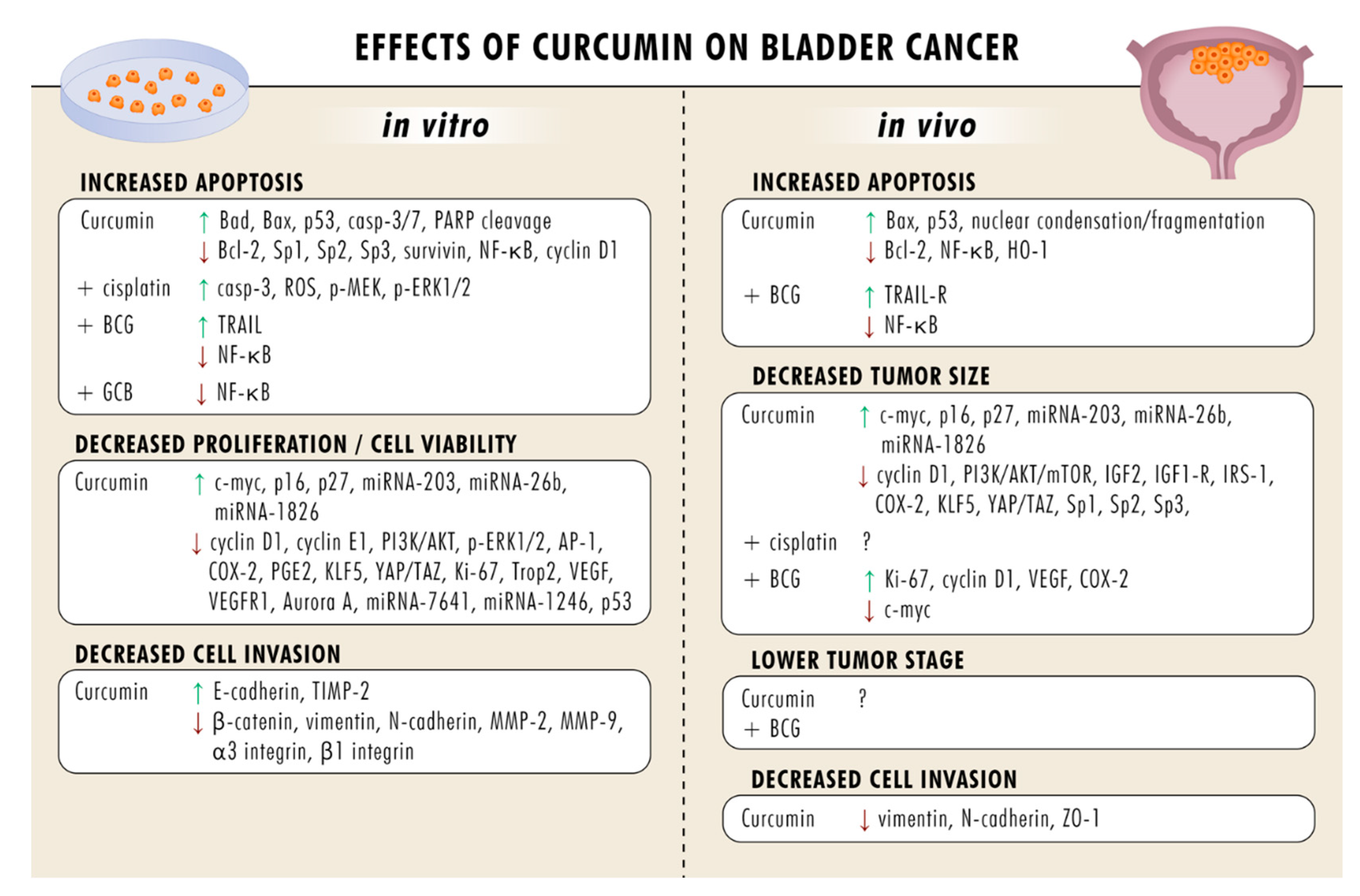

5. Curcumin Blocks Bladder Cancer Growth and Proliferation

6. Curcumin Induces Apoptosis

7. Curcumin Suppresses Metastatic Events

8. Curcumin-Triggered Immune Response

9. Curcumin Plus Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) Intravesical Therapy

10. Curcumin Plus Chemotherapy

11. Dose-Dependent Effects of Curcumin

12. Side Effects of Curcumin

13. Curcumin Delivery

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nadal, R.; Bellmunt, J. Management of metastatic bladder cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2019, 76, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babjuk, M.; Böhle, A.; Burger, M.; Capoun, O.; Cohen, D.; Compérat, E.M.; Hernández, V.; Kaasinen, E.; Palou, J.; Rouprêt, M.; et al. EAU Guidelines on Non-Muscle-invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: Update 2016. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, A.; D’Andrea, D.; Abufaraj, M.; Foerster, B.; Kimura, S.; Shariat, S.F. Genetic determinants for chemo- and radiotherapy resistance in bladder cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2017, 6, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.S.; Rodney, S.; Lamb, B.; Feneley, M.; Kelly, J. Management of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: A comprehensive analysis of guidelines from the United States, Europe and Asia. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 47, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, R.J.; van der Meijden, A.P.M.; Oosterlinck, W.; Witjes, J.A.; Bouffioux, C.; Denis, L.; Newling, D.W.W.; Kurth, K. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: A combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur. Urol. 2006, 49, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witjes, J.A.; Compérat, E.; Cowan, N.C.; de Santis, M.; Gakis, G.; Lebret, T.; Ribal, M.J.; van der Heijden, A.G.; Sherif, A. EAU guidelines on muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: Summary of the 2013 guidelines. Eur. Urol. 2014, 65, 778–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, J.; Roth, B.; Seiler, R. Forty years of cisplatin-based chemotherapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Are we understanding how, who and when? World J. Urol. 2018, 37, 1759–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Mao, J.J.; Vertosick, E.; Seluzicki, C.; Yang, Y. Evaluating Cancer Patients’ Expectations and Barriers Toward Traditional Chinese Medicine Utilization in China: A Patient-Support Group-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Definitions 2020, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s in a Name? Available online: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Buckner, C.A.; Lafrenie, R.M.; Dénommée, J.A.; Caswell, J.M.; Want, D.A. Complementary and alternative medicine use in patients before and after a cancer diagnosis. Curr. Oncol. 2018, 25, e275–e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahall, M. Prevalence, patterns, and perceived value of complementary and alternative medicine among HIV patients: A descriptive study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, A.; Kang, D.-H.; Kim, D.U. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use and Its Association with Emotional Status and Quality of Life in Patients with a Solid Tumor: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drozdoff, L.; Klein, E.; Kiechle, M.; Paepke, D. Use of biologically-based complementary medicine in breast and gynecological cancer patients during systemic therapy. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, K.; Kinder, D.; Stockert, A. Biologically-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) Use in Cancer Patients: The Good, the Bad, the Misunderstood. Front. Nutr. 2020, 6, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldiken, B.; Ozkan, G.; Catalkaya, G.; Ceylan, F.D.; Ekin Yalcinkaya, I.; Capanoglu, E. Phytochemicals of herbs and spices: Health versus toxicological effects. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 119, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Zucca, P.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Pezzani, R.; Rajabi, S.; Setzer, W.N.; Varoni, E.M.; Iriti, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Phytotherapeutics in cancer invasion and metastasis. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 1425–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedjou, C.G.; Mbemi, A.T.; Noubissi, F.; Tchounwou, S.S.; Tsabang, N.; Payton, M.; Miele, L.; Tchounwou, P.B. Prostate Cancer Disparity, Chemoprevention, and Treatment by Specific Medicinal Plants. Nutrients 2019, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benarba, B.; Pandiella, A. Colorectal cancer and medicinal plants: Principle findings from recent studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naujokat, C.; McKee, D.L. The “Big Five” Phytochemicals Targeting Cancer Stem Cells: Curcumin, EGCG, Sulforaphane, Resveratrol and Genistein. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Wachtel-Galor, S. Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.C.; Sung, B.; Kim, J.H.; Prasad, S.; Li, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Multitargeting by turmeric, the golden spice: From kitchen to clinic. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 57, 1510–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. Chemical Composition and Product Quality Control of Turmeric (Curcuma longa L.). Pharm. Crop. 2011, 5, 28–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, K.M.; Dahlin, J.L.; Bisson, J.; Graham, J.; Pauli, G.F.; Walters, M.A. The Essential Medicinal Chemistry of Curcumin. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1620–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarsini, K.I. The chemistry of curcumin: From extraction to therapeutic agent. Molecules 2014, 19, 20091–20112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; Panda, A.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Sa, G. Curcumin and tumor immune-editing: Resurrecting the immune system. Cell Div. 2015, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Lin, T.; Poiani, G.; Wassef, A.; Hudlikar, R.; Ondar, P.; Brunetti, L.; Kong, A.-N. Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and PKPD Modeling of Curcumin in Regulating Antioxidant and Epigenetic Gene Expression in Healthy Human Volunteers. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 1881–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soflaei, S.S.; Momtazi-Borojeni, A.A.; Majeed, M.; Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; Sahebkar, A. Curcumin: A Natural Pan-HDAC Inhibitor in Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, G.; Zhang, R.; Dong, L.; Chen, H.; Bo, J.; Xue, W.; Huang, Y. Curcumin inhibits cell proliferation and motility via suppression of TROP2 in bladder cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2018, 53, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Xiao, N.; Tian, J.; et al. Effects of curcumin on bladder cancer cells and development of urothelial tumors in a rat bladder carcinogenesis model. Cancer Lett. 2008, 264, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-S.; Ke, C.-S.; Cheng, H.-C.; Huang, C.-Y.F.; Su, C.-L. Curcumin-induced mitotic spindle defect and cell cycle arrest in human bladder cancer cells occurs partly through inhibition of aurora A. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011, 80, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, G.Y.; Kim, G.D.; Choi, B.T.; Park, Y.-M.; Choi, Y.H. Induction of G2/M arrest and inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 activity by curcumin in human bladder cancer T24 cells. Oncol. Rep. 2006, 15, 1225–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadalapaka, G.; Jutooru, I.; Chintharlapalli, S.; Papineni, S.; Smith, R.; Li, X.; Safe, S. Curcumin decreases specificity protein expression in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 5345–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, F.; Binder, K.; Rutz, J.; Maxeiner, S.; Bernd, A.; Kippenberger, S.; Zöller, N.; Chun, F.K.-H.; Juengel, E.; Blaheta, R.A. The Antitumor Effect of Curcumin in Urothelial Cancer Cells Is Enhanced by Light Exposure In Vitro. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 6374940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature 2014, 507, 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.T.; Hui, G.; Mathis, C.; Chamie, K.; Pantuck, A.J.; Drakaki, A. The Current Status and Future Role of the Phosphoinositide 3 Kinase/AKT Signaling Pathway in Urothelial Cancer: An Old Pathway in the New Immunotherapy Era. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 2017, 16, e269–e276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, B.R.; Vakar-Lopez, F.; Brown, L.; Montgomery, B.; Seiler, R.; Black, P.C.; Boormans, J.L.; Dall Era, M.; Davincioni, E.; Douglas, J.; et al. Mechanistic target of rapamycin (MTOR) protein expression in the tumor and its microenvironment correlates with more aggressive pathology at cystectomy. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2018, 36, 342.e7–342.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Zeng, Q.H.; Cao, P.G.; Xie, D.; Yang, F.; He, L.Y.; Dai, Y.B.; Li, J.J.; Liu, X.M.; Zeng, H.L.; et al. SPAG5 promotes proliferation and suppresses apoptosis in bladder urothelial carcinoma by upregulating Wnt3 via activating the AKT/mTOR pathway and predicts poorer survival. Oncogene 2018, 37, 3937–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Zhao, Y.; Liang, T.; Ye, X.; Li, Z.; Yan, D.; Fu, Q.; Li, Y. Curcumin inhibits urothelial tumor development by suppressing IGF2 and IGF2-mediated PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Drug Target. 2017, 25, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z. Curcumin Induces Apoptosis in EJ Bladder Cancer Cells via Modulating C-Myc and PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. World J. Oncol. 2011, 2, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Deng, Q.-F.; Liang, Z.-F.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Zhao, L.; Geng, H.; Xie, D.-D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, D.-X.; Zhong, C.-Y. Curcumin reverses benzidine-induced cell proliferation by suppressing ERK1/2 pathway in human bladder cancer T24 cells. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2016, 68, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, K.R.M.; Chade, D.C.; Sanudo, A.; Sakiyama, B.Y.P.; Batocchio, G.; Srougi, M. Effects of curcumin in an orthotopic murine bladder tumor model. Int. Braz. J. 2009, 35, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gao, Y.; Ding, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, H.; Zhou, J. Targeting Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) for cancer therapy. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Shi, Q.; Xu, S.; Du, C.; Liang, L.; Wu, K.; Wang, K.; Wang, X.; Chang, L.S.; He, D.; et al. Curcumin promotes KLF5 proteasome degradation through downregulating YAP/TAZ in bladder cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 15173–15187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Yi, Y.; Grubbs, C.J.; Lubet, R.A.; You, M. Gene expression profiling of chemically induced rat bladder tumors. Neoplasia 2007, 9, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pichu, S.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Shishkov, A.; Zhang, B.; McCue, P.; Ponnappa, B.C. Knockdown of Ki-67 by dicer-substrate small interfering RNA sensitizes bladder cancer cells to curcumin-induced tumor inhibition. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.; Arora, S.; Majid, S.; Shahryari, V.; Chen, Y.; Deng, G.; Yamamura, S.; Ueno, K.; Dahiya, R. Curcumin modulates microRNA-203-mediated regulation of the Src-Akt axis in bladder cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 1698–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Tan, S.-L.; Lu, Q.; Xu, R.; Cao, J.; Wu, S.-Q.; Wang, Y.-H.; Zhao, X.-K.; Zhong, Z.-H. Curcumin Suppresses microRNA-7641-Mediated Regulation of p16 Expression in Bladder Cancer. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018, 46, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Li, H.; Wu, S.; Qu, J.; Yuan, H.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, Q. MicroRNA-1246 regulates the radio-sensitizing effect of curcumin in bladder cancer cells via activating P53. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2019, 51, 1771–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Ma, X.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Gu, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Fan, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. MicroRNAs with prognostic significance in bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunagaran, D.; Rashmi, R.; Kumar, T.R.S. Induction of apoptosis by curcumin and its implications for cancer therapy. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2005, 5, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Shi, T.; Li, H. Antitumor effects of curcumin in human bladder cancer in vitro. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 1157–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, P.K.; Goel, A.; Mittal, R.D. Survivin: A molecular biomarker in cancer. Indian J. Med. Res. 2015, 141, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Z.-J.; Deng, N.; Zou, Z.-H.; Chen, G.-X. The effect of curcumin on bladder tumor in rat model. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 884–889. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Kong, X.; Li, Y.; Qian, W.; Ma, J.; Wang, D.; Yu, D.; Zhong, C. Curcumin inhibits bladder cancer stem cells by suppressing Sonic Hedgehog pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 493, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.-S.; Zheng, L.-D.; Lu, P.; Jiang, F.-c.; Chen, F.-M.; Zeng, F.-Q.; Wang, L.; Dong, J.-H. Apoptosis-inducing effects of curcumin derivatives in human bladder cancer cells. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2006, 17, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhwani, P.; Hampton, J.A.; Baig, M.M.; Keck, R.; Selman, S.H. Curcumin prevents intravesical tumor implantation of the MBT-2 tumor cell line in C3H mice. J. Urol. 2001, 166, 1498–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, J.; Fleger, J.; Rutz, J.; Maxeiner, S.; Bernd, A.; Kippenberger, S.; Zöller, N.; Chun, F.K.-H.; Relja, B.; Juengel, E.; et al. Curcumin combined with exposure to visible light blocks bladder cancer cell adhesion and migration by an integrin dependent mechanism. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 10564–10574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Majeed, M.; Sahebkar, A. Curcumin: A potent agent to reverse epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell. Oncol. 2019, 42, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Jia, Z.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, C.; Yao, Y. Curcumin inhibits bladder cancer progression via regulation of β-catenin expression. Tumor Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317702548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Xie, W.; Wu, R.; Geng, H.; Zhao, L.; Xie, C.; Li, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, W.; Zhu, J.; et al. Inhibition of tobacco smoke-induced bladder MAPK activation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mice by curcumin. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 4503–4513. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Lu, L.; Mao, J.; Li, X.; Qian, H.; Xu, W. Curcumin reversed chronic tobacco smoke exposure induced urocystic EMT and acquisition of cancer stem cells properties via Wnt/β-catenin. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F.-Q.; Chen, M.-J.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, R.-S.; Qiu, W.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhao, H.-W.; Yu, R.-J.; Wu, X.-F.; et al. Curcumin Suppresses Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition of Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells through the Inhibition of Akt/mTOR Pathway. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 40, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuttan, G.; Kumar, K.B.H.; Guruvayoorappan, C.; Kuttan, R. Antitumor, anti-invasion, and antimetastatic effects of curcumin. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2007, 595, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.-R.; Huang, C.-C.; Li, Y.-Z.; Chang, Y.-S.; Yang, C.-Y.; Wu, J.-D.; Liu, Y.-W. Curcumin-induced heme oxygenase-1 expression plays a negative role for its anti-cancer effect in bladder cancers. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3530–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostroumov, D.; Fekete-Drimusz, N.; Saborowski, M.; Kühnel, F.; Woller, N. CD4 and CD8 T lymphocyte interplay in controlling tumor growth. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 75, 689–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, S.; Kim, K.-H. Differential Expression and Clinicopathological Significance of HER2, Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase and PD-L1 in Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, K.; Eckstein, M.; Fiorentino, M.; Montironi, R. PD1/PD-L1 axis in uro-oncology. Curr. Drug Targets 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Liu, L.; Luo, E.; Hu, J. Curcumin enhances anti-tumor immune response in tongue squamous cell carcinoma. Arch. Oral Biol. 2018, 92, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yu, L.; Zhao, L.-Z. Curcumin up regulates T helper 1 cells in patients with colon cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 1866–1875. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Jia, Y.; Yao, Z.; Huang, J.; Hao, M.; Yao, S.; Lian, N.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; et al. Hepatic stellate cell interferes with NK cell regulation of fibrogenesis via curcumin induced senescence of hepatic stellate cell. Cell. Signal. 2017, 33, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Cho, H. Improved Anti-Cancer Effect of Curcumin on Breast Cancer Cells by Increasing the Activity of Natural Killer Cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.-F.; Chuang, H.-Y.; Hsu, C.-H.; Liu, R.-S.; Gambhir, S.S.; Hwang, J.-J. Immunomodulation of curcumin on adoptive therapy with T cell functional imaging in mice. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 5, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Da, J.; Xu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z. Bisdemethoxycurcumin in combination with α-PD-L1 antibody boosts immune response against bladder cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2017, 10, 2675–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanpoor, Z.; Mostafaie, A.; Nikokar, I.; Hassan, Z.M. Curcumin-human serum albumin nanoparticles decorated with PDL1 binding peptide for targeting PDL1-expressing breast cancer cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayakawa, T.; Sugiyama, J.; Yaguchi, T.; Imaizumi, A.; Kawakami, Y. Enhanced anti-tumor effects of the PD-1/PD-L1 blockade by combining a highly absorptive form of NF-kB/STAT3 inhibitor curcumin. J. Immunother. Cancer 2014, 2, P210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tuyaerts, S.; van Nuffel, A.M.T.; Naert, E.; van Dam, P.A.; Vuylsteke, P.; de Caluwé, A.; Aspeslagh, S.; Dirix, P.; Lippens, L.; de Jaeghere, E.; et al. PRIMMO study protocol: A phase II study combining PD-1 blockade, radiation and immunomodulation to tackle cervical and uterine cancer. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambier, S.; Sylvester, R.J.; Collette, L.; Gontero, P.; Brausi, M.A.; van Andel, G.; Kirkels, W.J.; Silva, F.C.D.; Oosterlinck, W.; Prescott, S.; et al. EORTC Nomograms and Risk Groups for Predicting Recurrence, Progression, and Disease-specific and Overall Survival in Non-Muscle-invasive Stage Ta-T1 Urothelial Bladder Cancer Patients Treated with 1-3 Years of Maintenance Bacillus Calmette-Guérin. Eur. Urol. 2016, 69, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falke, J.; Parkkinen, J.; Vaahtera, L.; Hulsbergen-van de Kaa, C.A.; Oosterwijk, E.; Witjes, J.A. Curcumin as Treatment for Bladder Cancer: A Preclinical Study of Cyclodextrin-Curcumin Complex and BCG as Intravesical Treatment in an Orthotopic Bladder Cancer Rat Model. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, A.M.; Tharakan, S.T.; Sung, B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin potentiates the antitumor effects of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin against bladder cancer through the downregulation of NF-kappaB and upregulation of TRAIL receptors. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 8958–8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, J.K.; Michalowski, A.M.; Gamache, B.J.; DuBois, W.; Patel, J.; Zhang, K.; Gary, J.; Zhang, S.; Gaikwad, S.; Connors, D.; et al. Cooperative Targets of Combined mTOR/HDAC Inhibition Promote MYC Degradation. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 2008–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmallah, M.I.Y.; Micheau, O. Epigenetic Regulation of TRAIL Signaling: Implication for Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2019, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, B.B.; Vijayalekshmi, R.V.; Sung, B. Targeting inflammatory pathways for prevention and therapy of cancer: Short-term friend, long-term foe. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmaiah, K.C.; Jacob, L.A.; Aparna, S.; Lokanatha, D.; Saldanha, S.C. Epigenetic therapy of cancer with histone deacetylase inhibitors. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2014, 10, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roca, M.S.; Di Gennaro, E.; Budillon, A. Implication for Cancer Stem Cells in Solid Cancer Chemo-Resistance: Promising Therapeutic Strategies Based on the Use of HDAC Inhibitors. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, C.-J.; Yang, C.-W.; Wu, C.-L.; Ho, J.-Y.; Yu, C.-P.; Wu, S.-T.; Yu, D.-S. The modulation study of multiple drug resistance in bladder cancer by curcumin and resveratrol. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 6869–6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, A.M.; Sethi, G.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin potentiates the apoptotic effects of chemotherapeutic agents and cytokines through down-regulation of nuclear factor-kappaB and nuclear factor-kappaB-regulated gene products in IFN-alpha-sensitive and IFN-alpha-resistant human bladder cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, M.; Otsuka, Y.; Otsuka, K.; Sato, M.; Nishimura, T.; Mori, Y.; Kawaguchi, M.; Hatano, E.; Kodama, Y.; Matsumoto, S.; et al. A phase I study investigating the safety and pharmacokinetics of highly bioavailable curcumin (Theracurmin) in cancer patients. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2013, 71, 1521–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.H.; Lim, J.E.; Jeon, H.G.; Seo, S.I.; Lee, H.M.; Choi, H.Y.; Jeon, S.S.; Jeong, B.C. Curcumin potentiates antitumor activity of cisplatin in bladder cancer cell lines via ROS-mediated activation of ERK1/2. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 63870–63886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagurauskaite, G.; Mahale, J.; Brown, K.; Thomas, A.L.; Howells, L.M. New Paradigms to Assess Consequences of Long-Term, Low-Dose Curcumin Exposure in Lung Cancer Cells. Molecules 2020, 25, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E. Curcumin Combination Chemotherapy: The Implication and Efficacy in Cancer. Molecules 2019, 24, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wang, J.; Guo, Q.; Tu, P. Simultaneous determination of doxorubicin and curcumin in rat plasma by LC-MS/MS and its application to pharmacokinetic study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015, 111, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrette-Guzmán, M. Combinations of the antioxidants sulforaphane or curcumin and the conventional antineoplastics cisplatin or doxorubicin as prospects for anticancer chemotherapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 859, 172513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueki, M.; Ueno, M.; Morishita, J.; Maekawa, N. Curcumin ameliorates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by inhibiting renal inflammation in mice. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2013, 115, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Barua, C.C.; Sulakhiya, K.; Sharma, R.K. Curcumin Ameliorates Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity and Potentiates Its Anticancer Activity in SD Rats: Potential Role of Curcumin in Breast Cancer Chemotherapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waseem, M.; Kaushik, P.; Parvez, S. Mitochondria-mediated mitigatory role of curcumin in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2013, 31, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Domínguez, B.; Aparicio-Trejo, O.E.; García-Arroyo, F.E.; León-Contreras, J.C.; Tapia, E.; Molina-Jijón, E.; Hernández-Pando, R.; Sánchez-Lozada, L.G.; Barrera-Oviedo, D.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Curcumin prevents cisplatin-induced renal alterations in mitochondrial bioenergetics and dynamic. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 107, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbaby, S.; Ewais, M.; Essawy, S.; Farag, N. Cardioprotective effects of curcumin and nebivolol against doxorubicin-induced cardiac toxicity in rats. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzer, F.; Kandemir, F.M.; Ozkaraca, M.; Kucukler, S.; Caglayan, C. Curcumin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by abrogation of inflammation, apoptosis, oxidative DNA damage, and protein oxidation in rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2018, 32, e22030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shu, W.; Chen, W.; Wu, Q.; Liu, H.; Cui, G. Curcumin, both histone deacetylase and p300/CBP-specific inhibitor, represses the activity of nuclear factor kappa B and Notch 1 in Raji cells. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 101, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Liang, L.; Liu, Q.; Duan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, L. Autophagy is a major mechanism for the dual effects of curcumin on renal cell carcinoma cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 826, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunwar, A.; Sandur, S.K.; Krishna, M.; Priyadarsini, K.I. Curcumin mediates time and concentration dependent regulation of redox homeostasis leading to cytotoxicity in macrophage cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 611, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.-C.; Lin, C.-J.; Liu, W.-J.; Jiang, R.-R.; Jiang, Z.-F. Dual effects of curcumin on neuronal oxidative stress in the presence of Cu(II). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 1578–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Tie, L.; Pan, Y.; Li, X. Opposite angiogenic outcome of curcumin against ischemia and Lewis lung cancer models: In silico, in vitro and in vivo studies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 1742–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.-Y.; Chen, J.-X. Effects of Curcumin on Vessel Formation Insight into the Pro- and Antiangiogenesis of Curcumin. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 1390795–1390799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsharmoghadam, N.; Haghighatian, Z.; Mazdak, H.; Mirkheshti, N.; Mehrabi Koushki, R.; Alavi, S.A. Concentration- Dependent Effects of Curcumin on 5-Fluorouracil Efficacy in Bladder Cancer Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2017, 18, 3225–3230. [Google Scholar]

- Bayet-Robert, M.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Leheurteur, M.; Gachon, F.; Planchat, E.; Abrial, C.; Mouret-Reynier, M.-A.; Durando, X.; Barthomeuf, C.; Chollet, P. Phase I dose escalation trial of docetaxel plus curcumin in patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 9, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epelbaum, R.; Schaffer, M.; Vizel, B.; Badmaev, V.; Bar-Sela, G. Curcumin and gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahammedi, H.; Planchat, E.; Pouget, M.; Durando, X.; Curé, H.; Guy, L.; Van-Praagh, I.; Savareux, L.; Atger, M.; Bayet-Robert, M.; et al. The New Combination Docetaxel, Prednisone and Curcumin in Patients with Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A Pilot Phase II Study. Oncology 2016, 90, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli, D.; Fabricio, A.S.C.; Giovanis, P.; D’Ippolito, S.; Fiduccia, P.; Soldà, C.; Buda, A.; Sperti, C.; Bardini, R.; Da Dalt, G.; et al. Phytosome complex of curcumin as complementary therapy of advanced pancreatic cancer improves safety and efficacy of gemcitabine: Results of a prospective phase II trial. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 132, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storka, A.; Vcelar, B.; Klickovic, U.; Gouya, G.; Weisshaar, S.; Aschauer, S.; Bolger, G.; Helson, L.; Wolzt, M. Safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of liposomal curcumin in healthy humans. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 53, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greil, R.; Greil-Ressler, S.; Weiss, L.; Schönlieb, C.; Magnes, T.; Radl, B.; Bolger, G.T.; Vcelar, B.; Sordillo, P.P. A phase 1 dose-escalation study on the safety, tolerability and activity of liposomal curcumin (Lipocurc™) in patients with locally advanced or metastatic cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 82, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ireson, C.; Orr, S.; Jones, D.J.; Verschoyle, R.; Lim, C.K.; Luo, J.L.; Howells, L.; Plummer, S.; Jukes, R.; Williams, M.; et al. Characterization of metabolites of the chemopreventive agent curcumin in human and rat hepatocytes and in the rat in vivo, and evaluation of their ability to inhibit phorbol ester-induced prostaglandin E2 production. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Sung, B.; Bhanu Prasad, B.A.; Schuber, P.T.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Bornmann, W.G. Curcumin glucuronides: Assessing the proliferative activity against human cell lines. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2013, 22, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, D.; Srinivasan, K. Tissue distribution & elimination of capsaicin, piperine & curcumin following oral intake in rats. Indian J. Med. Res. 2010, 131, 682–691. [Google Scholar]

- Panahi, Y.; Hosseini, M.S.; Khalili, N.; Naimi, E.; Majeed, M.; Sahebkar, A. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of curcuminoid-piperine combination in subjects with metabolic syndrome: A randomized controlled trial and an updated meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolat, Z.B.; Islek, Z.; Demir, B.N.; Yilmaz, E.N.; Sahin, F.; Ucisik, M.H. Curcumin- and Piperine-Loaded Emulsomes as Combinational Treatment Approach Enhance the Anticancer Activity of Curcumin on HCT116 Colorectal Cancer Model. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Liu, Y.-K.; Tsai, N.-M.; Hsieh, J.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Lin, C.-M.; Liao, K.-W. A Lipo-PEG-PEI complex for encapsulating curcumin that enhances its antitumor effects on curcumin-sensitive and curcumin-resistance cells. Nanomedicine 2012, 8, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Lou, H.; Zhao, L.; Fan, P. Validated LC/MS/MS assay for curcumin and tetrahydrocurcumin in rat plasma and application to pharmacokinetic study of phospholipid complex of curcumin. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006, 40, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Shayeganpour, A.; Brocks, D.R.; Lavasanifar, A.; Samuel, J. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of curcumin in rat plasma: Application to pharmacokinetics of polymeric micellar formulation of curcumin. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2007, 21, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, R.; Sen, R.; Paul, B.; Kazi, J.; Ganguly, S.; Debnath, M.C. Gemcitabine Co-Encapsulated with Curcumin in Folate Decorated PLGA Nanoparticles; a Novel Approach to Treat Breast Adenocarcinoma. Pharm. Res. 2020, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbese, Z.; Khwaza, V.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Curcumin and Its Derivatives as Potential Therapeutic Agents in Prostate, Colon and Breast Cancers. Molecules 2019, 24, 4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Zhao, P.; Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Hu, P.; Li, L.; Cheng, Y.; Yao, H. Reversal of P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Multidrug Resistance by Novel Curcumin Analogues in Paclitaxel-resistant Human Breast Cancer Cells. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, B.; Liu, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zuo, Y.; Huang, L.; Wen, G.; Shang, N.; Chen, Y.; Yue, X.; et al. MC37, a new mono-carbonyl curcumin analog, induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 796, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.-Y.; Zhai, Q.; Chen, J.-Z.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Yang, J. 2,2’-Fluorine mono-carbonyl curcumin induce reactive oxygen species-Mediated apoptosis in Human lung cancer NCI-H460 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 786, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, D.-B.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Zeng, Y.-L.; Yan, Q.-Z.; Shi, Z.; Tuo, Q.-H.; Lin, L.-M.; Xia, B.-H.; Wu, P.; Liao, D.-F. Curcumin: From a controversial “panacea” to effective antineoplastic products. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e18467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Model | Cell Lines/Drugs | Outcome | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COMBINATION THERAPY | ||||

| in vitro | T24-gemcitabine resistant GCB + Curcumin | reversal of drug resistance | ABCC2; Cleaved PARP ↑ DCK; TK1;TK2; Migration ↓ | [87] |

| in vitro | IFN-α–sensitive (RT4V6) and IFN-α–resistant (KU-7) GCB + Curcumin | increased apoptosis, IFN-α-independent | NF-κB ↓ | [88] |

| in vitro | 253J-Bv and T24 Cisplatin + Curcumin | increased apoptosis | Caspase-3; ROS ↑ p-MEK; p-ERK1/2 ↑ | [90] |

| in vivo | nude mice, 253J-Bv xenografts Cisplatin + Curcumin | decreased tumor size | - | [90] |

| in vitro | 253J-Bv BCG + Curcumin | increased apoptosis | TRAIL ↑; TRAIL receptor activity ↑; NF-κB ↓ | [81] |

| in vivo | MTB-2-transplanted C3H mice BCG + Curcumin | increased apoptosis, decreased tumor size | Ki-67; CD31; NF-κB ↓; Cyclin D1; VEGF; COX-2 ↓ c-myc; Bcl-2 ↓ TRAIL receptor ↑ | [81] |

| in vivo | F344 rats, AY27 xenografts BCG + Cyclodextrin–Curcumin | lower tumor stage | - | [80] |

| MONOTHERAPY | ||||

| in vitro | 253JB-V and KU7 | increased apoptosis, cell growth inhibition | Sp1; Sp3; Sp4; Survivin ↓ VEGF; VEGFR1; p21; p27↓ Cleaved PARP ↑ | [34] |

| in vivo | nude mice, KU7 xenografts | decreased tumor growth | Sp1; Sp3; Sp4 ↓ | [34] |

| in vitro | 5637 and WH | decreased cell viability, proliferation blockade | KLF5; YAP; TAZ; AXL ↓ ITGB2; CDK6; CYR61 ↓ | [45] |

| in vivo | Nude mice, 5637 xenografts | decreased tumor size | YAP/TAZ; KLF5;PCNA ↓ Cyclin D1 ↓ | [45] |

| in vitro | AY-27 (rat) and T-24, | increased apoptosis, cell cycle arrest | 7-AAD; p27; Caspase-3 ↑ Cyclin D1; pRb-P; cyclin E ↓ p21; p53; NF-κB ↓ | [47] |

| in vitro | T24 | inhibited cell growth, G2/M arrest | Cyclin A; COX-2, PGE2 ↓ p21 ↑ | [33] |

| in vitro | T24 and 5637 | decreased cell growth, increased apoptosis, inhibition of migration | Caspase-3/7; TIMP-2 ↑ MMP-2; MMP-9 ↓ | [53] |

| in vitro | T24 and 5637 | proliferation blockade, increased apoptosis inhibition of migration and invasion | β-Catenin ↓ Vimentin ↓ N-cadherin ↓ E-cadherin ↑ | [61] |

| in vitro | T24, UMUC2 and EJ | decreased cell viability, increased apoptosis, G2/M cell cycle arrest | Bcl-2; Survivin ↓ Bax; p53 ↑ | [31] |

| in vivo | Wistar rats, N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced bladder cancer | increased apoptosis | Nuclear condensation and fragmentation ↑ | [31] |

| in vitro | EJ | decreased cell viability, increased apoptosis | Intracellular esterase activity ↑ Caspase-3 ↑ DNA fragmentation ↑ | [57] |

| in vitro | T24 | decreased cell growth, G2/M cell cycle arrest | Aurora A ↓ | [31] |

| in vitro | T24 | decreased benzidine-triggered cell proliferation and G1 to S phase transition | p-ERK1/2 ↓ PCNA ↓ Cyclin D1 ↓ p21 ↑ | [42] |

| in vitro | UMUC3 and EJ | proliferation blockade, increased apoptosis | PCNA; cyclin D1; Bcl-2 ↓ Bax; Cleaved Caspase 3 ↑ Caspase 8; Caspase 9 ↑ | [56] |

| in vitro | 5637 and BFTC 905 | decreased cell viability, inhibition of invasion | MMP-2; MMP-9 ↓ ROS; HO-1 ↑ | [66] |

| in vivo | C57BL/6 mice, MB49 xenograft | HO-1 ↑ | [66] | |

| in vitro | T24 and RT4 | proliferation blockade, increased apoptosis, inhibition of mobility, G2/M cell cycle arrest | Trop2 ↓ Cyclin E1 ↓ p27 ↑ | [30] |

| in vitro | T24 and SV-HUC-1 | inhibition of invasion, increased apoptosis | miR-7641 ↓ p16 ↑ | [49] |

| in vitro | T24 Combination with irradiation | decreased cell viability and colony formation | miR-1246 ↓ | [50] |

| in vitro | T24 | proliferation blockade, increased apoptosis | miR-203 ↑ Akt2; Src ↓ | [48] |

| in vitro | RT112, TCCSUP and UMUC3 Combination with visible light | alteration in adhesion, inhibition of chemotaxis | RT112: pFAK; α5; β1 ↓ TCCSUP: α3; α5; β1 ↓ UMUC3: pFAK; α5; β1 ↓ | [59] |

| in vivo | BALB/c mice exposed to tobacco smoke for 12 weeks | ameliorated EMT alterations | p-ERK1/2; p-JNK ↓ p-p38 MAPK; E-cadherin ↓ N-cadherin; ZO-1; Vimentin ↓ | [62] |

| in vivo | C57BL/6 mice, MB49 xenograft | reduced tumor size | COX-2; Cyclin D1 ↓ | [43] |

| in vivo | Wistar rats, N-methyl-N-nitrosourea-induced bladder cancer | decreased cell growth, inhibition of invasion | Bcl-2; Survivin ↓ Bax ↑ | [55] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rutz, J.; Janicova, A.; Woidacki, K.; Chun, F.K.-H.; Blaheta, R.A.; Relja, B. Curcumin—A Viable Agent for Better Bladder Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113761

Rutz J, Janicova A, Woidacki K, Chun FK-H, Blaheta RA, Relja B. Curcumin—A Viable Agent for Better Bladder Cancer Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(11):3761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113761

Chicago/Turabian StyleRutz, Jochen, Andrea Janicova, Katja Woidacki, Felix K.-H. Chun, Roman A. Blaheta, and Borna Relja. 2020. "Curcumin—A Viable Agent for Better Bladder Cancer Treatment" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 11: 3761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113761

APA StyleRutz, J., Janicova, A., Woidacki, K., Chun, F. K.-H., Blaheta, R. A., & Relja, B. (2020). Curcumin—A Viable Agent for Better Bladder Cancer Treatment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(11), 3761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21113761