VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) and Fibrotic Lung Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. VEGF Biology

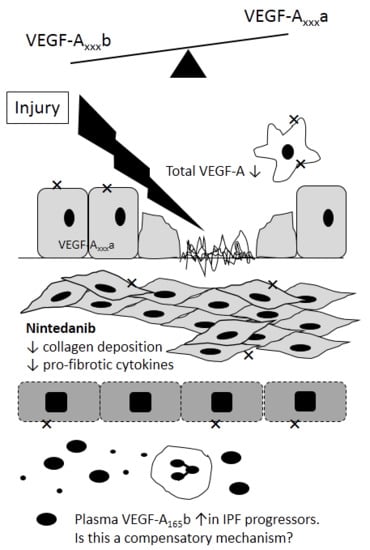

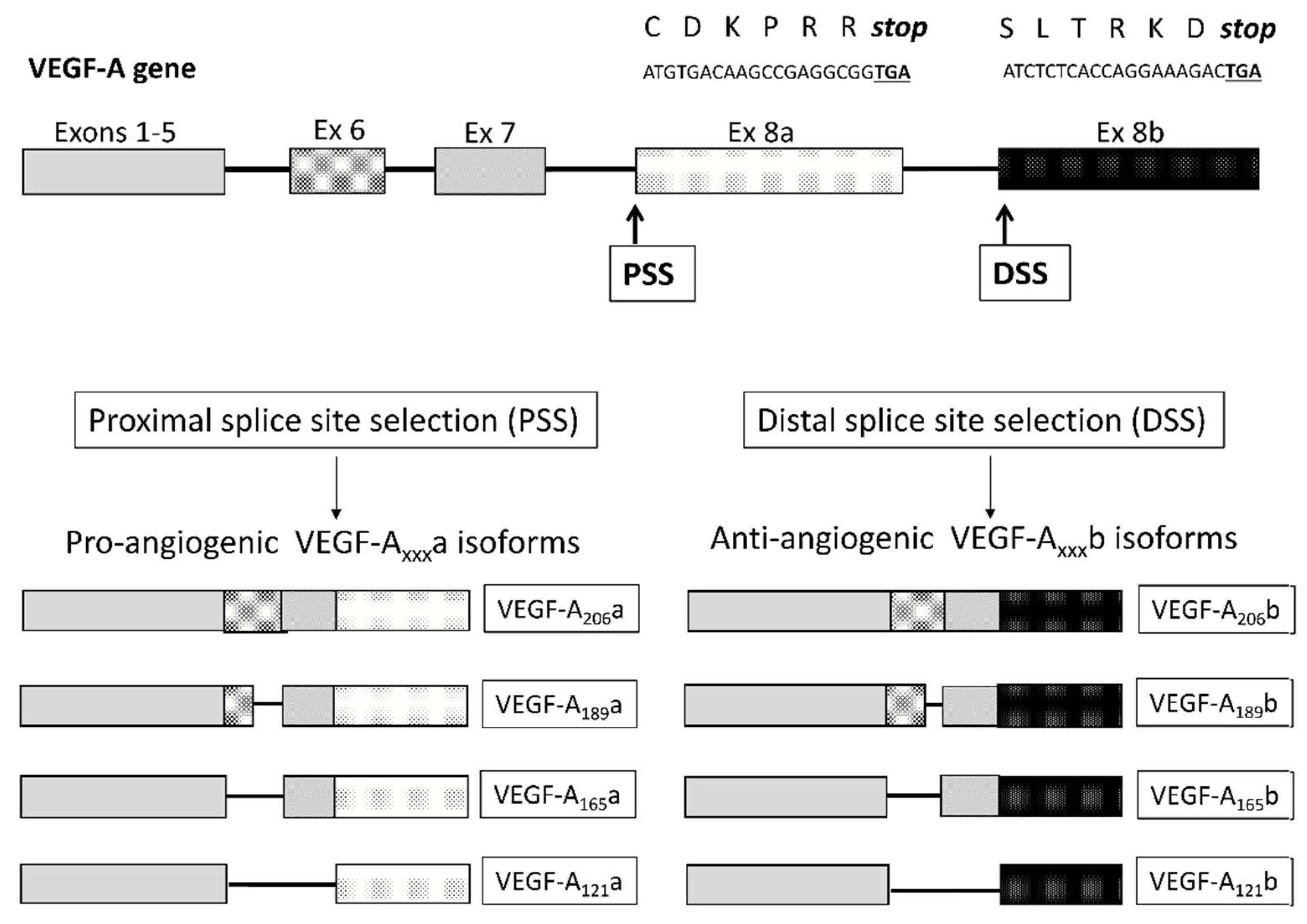

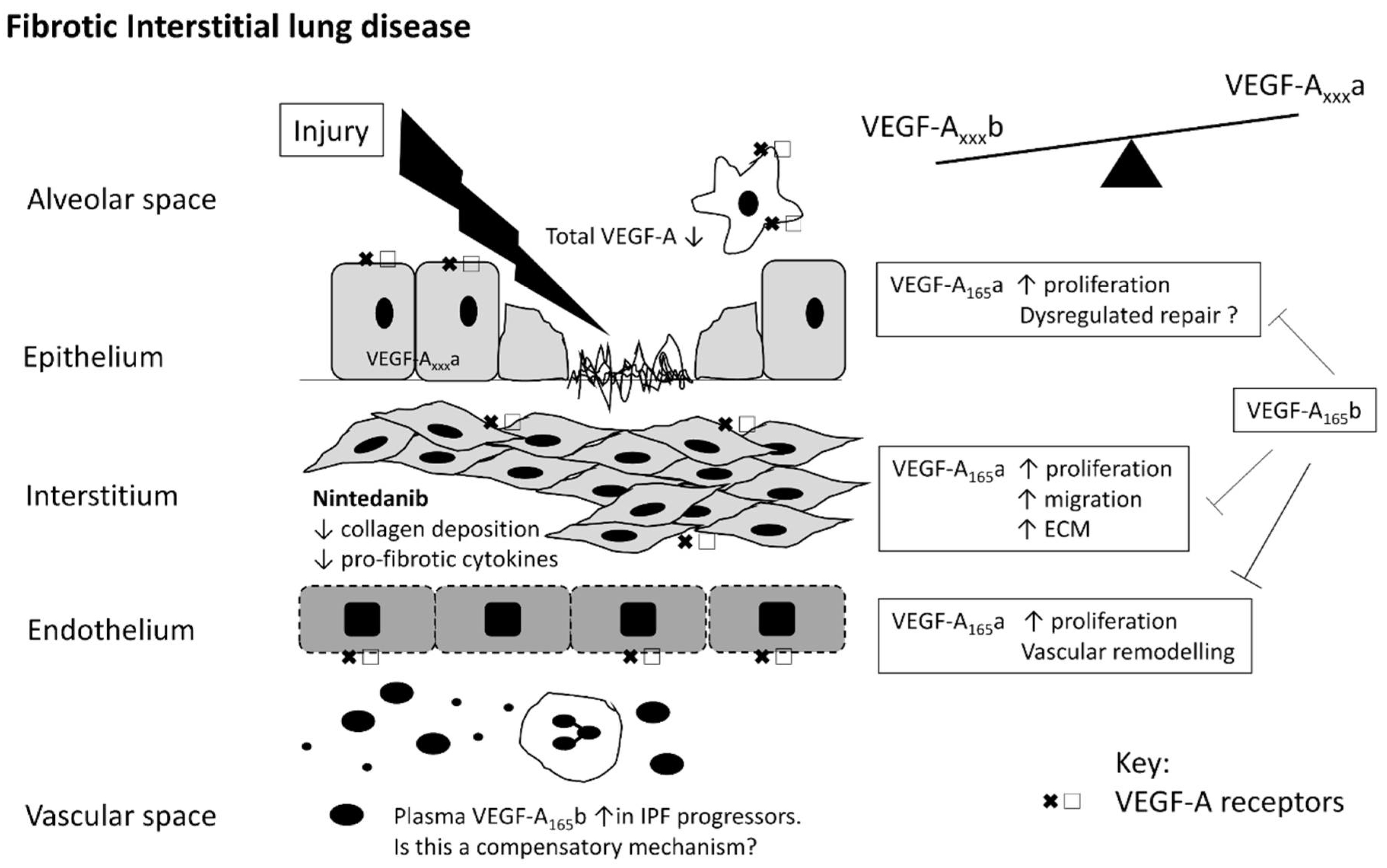

2.1. VEGF Isoforms

2.2. VEGF Receptors

2.3. VEGF and the Lung

3. VEGF in ARDS

4. VEGF in IPF

5. VEGF in Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis (HP)

6. VEGF-A in Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases

6.1. SSc

6.2. Other Forms of CTD-ILD

6.3. Inflammatory Arthritis

7. Summary

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 165, 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- Richeldi, L.; du Bois, R.M.; Raghu, G.; Azuma, A.; Brown, K.; Costabel, U.; Cottin, V.; Flaherty, K.R.; Hansell, D.M.; Yoshikazu, I.; et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2071–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, N.; Gerger, H.P.; Lecouter, J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.W.; Cachianes, G.; Kuang, W.J.; Goeddel, D.V.; Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science 1989, 246, 1306–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacchigna, S.; Lambrechts, D.; Carmeliet, P. Neurovascular signaling defects in neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, S.J.; Bates, D.O. VEGF-A splicing: The key to anti-angiogenic therapeutics? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.O. Vascular endothelial growth factors and vascular permeability. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 87, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.O.; Cui, T.G.; Doughty, J.M.; Winkler, M.; Sugiono, M.; Shields, J.D.; Peat, D.; Gillatt, D.; Harper, S.J. VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 4123–4131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Woolard, J.; Wang, W.Y.; Bevan, H.S.; Qiu, Y.; Morbidelli, L.; Pritchard-Jones, R.O.; Cui, T.G.; Sugiono, M.; Waine, E.; Perrin, R.; et al. VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: Mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 7822–7835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebe Suarez, S.; Pieren, M.; Cariolato, L.; Arn, S.; Hoffmann, U.; Bogucki, A.; Manlius, C.; Wood, J.; Ballmer-Hofer, K. A VEGF-A splice variant defective for heparan sulfate and neuropilin-1 binding shows attenuated signaling through VEGFR-2. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.O.; Qiu, Y.; Cater, J.G.; Hamdollah-Zadeh, M.; Barratt, S.; Gammons, M.V.; Millar, A.B.; Salmon, A.H.J.; Oltean, S.; Haeper, S.J. Detection of VEGF-A(xxx)b isoforms in human tissues. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olofsson, B.; Korpelainen, E.; Pepper, M.S.; Mandriota, S.J.; Aase, K.; Kumar, V.; Gunji, Y.; Jeltsch, M.M.; Shibuya, M.; Alitalo, K.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGF-B) binds to VEGF receptor-1 and regulates plasminogen activator activity in endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 11709–11714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joukov, V.; Pajusola, K.; Kaipainen, A.; Chilov, D.; Lahtinen, I.; Kukk, E.; Saksela, O.; Kalkkinen, N.; Alitalo, K. A novel vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-C, is a ligand for the Flt4 (VEGFR-3) and KDR (VEGFR-2) receptor tyrosine kinases. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olofsson, B.; Pajusola, K.; Kaipainen, A.; Von Eular, G.; Joukov, V.; Saksela, O.; Orpana, A.; Pettersson, R.F.; Alitalo, K.; Eriksson, U. Vascular endothelial growth factor B, a novel growth factor for endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 2576–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanstall, J.C.; Gambino, A.; Jeffrey, T.K.; Cahill, M.M.; Bellomo, D.; Hayward, N.K.; Kay, G.F. Vascular endothelial growth factor-B-deficient mice show impaired development of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002, 55, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirzenius, M.; Tammela, T.; Uutela, M.; He, Y.; Odorisio, T.; Zambruno, G.; Nagy, J.A.; Dvorak, H.F.; Yla-Herttuala, S.; Shibuya, M.; et al. Distinct vascular endothelial growth factor signals for lymphatic vessel enlargement and sprouting. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaristo, A.; Veikkola, T.; Enholm, B.; Hytonen, M.; Arola, J.; Pajusola, K.; Turunen, P.; Jeltsch, M.; Karkkainen, M.J.; Kerjaschki, D.; et al. Adenoviral VEGF-C overexpression induces blood vessel enlargement, tortuosity, and leakiness but no sprouting angiogenesis in the skin or mucous membranes. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, S.; Oku, A.; Sawano, A.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yazaki, Y.; Shibuya, M. A novel type of vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF-E (NZ-7 VEGF), preferentially utilizes KDR/Flk-1 receptor and carries a potent mitotic activity without heparin-binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 31273–31282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPalma, T.; Tucci, M.; Russo, G.; Maglione, D.; Lago, C.T.; Romano, A.; Saccone, S.; Della Valle, G.; De Gregorio, L.; Dragani, T.A.; et al. The placenta growth factor gene of the mouse. Mamm. Genome 1996, 7, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y. Positive and negative modulation of angiogenesis by VEGFR1 ligands. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, A.; Cao, R.; Pawliuk, R.; Berg, S.M.; Tsang, M.; Zhou, D.; Fleet, C.; Tritsaris, K.; Dissing, S.; Leboulch, P.; et al. Placenta growth factor-1 antagonizes VEGF-induced angiogenesis and tumor growth by the formation of functionally inactive PlGF-1/VEGF heterodimers. Cancer Cell 2002, 1, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P.; Moons, L.; Luttun, A.; Vincenti, V.; Compernolle, V.; De Mol, M.; Wu, Y.; Bono, F.; Devy, L.; Beck, H.; et al. Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat. Med. 2001, 7, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, T.; Claesson-Welsh, L. VEGF receptor signal transduction. Sci. STKE 2001, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalaby, F.; Rossant, J.; Yamaguchi, T.P.; Gertsenstein, M.; Wu, X.F.; Breitman, M.L.; Schuh, A.C. Failure of blood-island formation and vasculogenesis in Flk-1-deficient mice. Nature 1995, 376, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehrenbach, H.; Kasper, M.; Haase, M.; Schuh, D.; Muller, M. Differential immunolocalization of VEGF in rat and human adult lung, and in experimental rat lung fibrosis: Light, fluorescence, and electron microscopy. Anat. Rec. 1999, 254, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, C.; Escobedo, J.A.; Ueno, H.; Houck, K.; Ferrara, N.; Williams, L.T. The fms-like tyrosine kinase, a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Science 1992, 255, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawano, A.; Iwai, S.; Sakurai, Y.; Ito, M.; Shitara, K.; Nakahata, T.; Shibuya, M. Flt-1, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1, is a novel cell surface marker for the lineage of monocyte-macrophages in humans. Blood 2001, 97, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maniscalco, W.M.; Watkins, R.H.; D’Angio, C.T.; Ryan, R.M. Hyperoxic injury decreases alveolar epithelial cell expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in neonatal rabbit lung. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1997, 16, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medford, A.R.; Douglas, S.K.; Godinho, S.I.; Uppington, K.M.; Armstrong, L.; Gillespie, K.M.; Van Zyl, B.; Tetley, T.D.; Ibrahim, N.B.; Millar, A.B. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) isoform expression and activity in human and murine lung injury. Respir. Res. 2009, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltenberger, J.; Claesson-Welsh, L.; Siegbahn, A.; Shibuya, M.; Heldin, C.H. Different signal transduction properties of KDR and Flt1, two receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 26988–26995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kendall, R.L.; Thomas, K.A. Inhibition of vascular endothelial cell growth factor activity by an endogenously encoded soluble receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 10705–10709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanno, S.; Oda, N.; Abe, M.; Terai, Y.; Ito, M.; Shitara, K.; Tabayashi, K.; Shibuya, M.; Sato, Y. Roles of two VEGF receptors, Flt-1 and KDR, in the signal transduction of VEGF effects in human vascular endothelial cells. Oncogene 2000, 19, 2138–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Tang, Z.; Hou, X.; Lennartsson, J.; Li, Y.; Koch, A.W.; Scotney, P.; Lee, C.; Arjunan, P.; Dong, L.; et al. VEGF-B is dispensable for blood vessel growth but critical for their survival, and VEGF-B targeting inhibits pathological angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 6152–6157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neufeld, G.; Cohen, T.; Gengrinovitch, S.; Poltorak, Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999, 13, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunewald, F.S.; Prota, A.E.; Giese, A.; Ballmer-Hofer, K. Structure-function analysis of VEGF receptor activation and the role of coreceptors in angiogenic signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1804, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, A.; Murray, J.; Saito, Y.; Kanthou, C.; Benzakour, O.; Shibuya, M.; Wijelath, E.S. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2001, 188, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, A.; Zielinski, R.; He, C.; Crow, M.T.; Biswal, S.; Tuder, R.M.; Becker, P.M. Pulmonary epithelial neuropilin-1 deletion enhances development of cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 180, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, L.; Gauldie, J.; Voelkel, N.F.; Kolb, M. Pulmonary hypertension and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A tale of angiogenesis, apoptosis, and growth factors. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2011, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accrregui, M.J.; Penisten, S.T.; Goss, K.L.; Ramirez, K.; Snyder, J.M. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression in human fetal lung in vitro. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1999, 20, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.S.; Rohan, R.; Sunday, M.E.; Demello, N.G.; D’Amore, P.A. Differential expression of VEGF isoforms in mouse during development and in the adult. Dev. Dyn. 2001, 220, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galambos, C.; Ng, Y.S.; Ali, A.; Noguchi, A.; Lovejoy, S.; D’Amore, P.A.; Demello, D.E. Defective pulmonary development in the absence of heparin-binding vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2002, 27, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mura, M.; Binnie, M.; Han, B.; Li, C.; Andrade, C.F.; Shiozaki, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ferrara, N.; Hwang, D.; Waddell, T.K.; et al. Functions of type II pneumocyte-derived vascular endothelial growth factor in alveolar structure, acute inflammation, and vascular permeability. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 176, 1725–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janer, J.; Lassus, P.; Haglund, C.; Paavonen, K.; Alitalo, K.; Andersson, S. Pulmonary vascular endothelial growth factor-C in development and lung injury in preterm infants. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 174, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paepe, M.E.; Greco, D.; Mao, Q. Angiogenesis-related gene expression profiling in ventilated preterm human lungs. Exp. Lung Res. 2010, 36, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, J.M.; Thompson, F.Y.; Brooks, S.K.; Shannon, J.M.; McCormick-Shannon, K.; Cameron, J.E.; Mallory, B.P.; Akeson, A.L. Mesenchymal expression of vascular endothelial growth factors D and A defines vascular patterning in developing lung. Dev. Dyn. 2002, 224, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janer, J.; Andersson, S.; Haglund, C.; Karikoski, R.; Lassus, P. Placental growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 in human lung development. Pediatrics 2008, 122, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurlbeck, W.M. Postnatal human lung growth. Thorax 1982, 37, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakkula, M.; Le Cras, T.D.; Gebb, S.; Hirth, K.P.; Tuder, R.M.; Voelkel, N.F.; Abman, S.H. Inhibition of angiogenesis decreases alveolarization in the developing rat lung. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2000, 279, L600–L607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath-Morrow, S.A.; Cho, C.; Zhen, L.; Hicklin, D.J.; Tuder, R.M. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 blockade disrupts postnatal lung development. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2005, 32, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berse, B.; Brown, L.F.; Van de Water, L.; Dvorak, H.F.; Senger, D.R. Vascular permeability factor (vascular endothelial growth factor) gene is expressed differentially in normal tissues, macrophages, and tumors. Mol. Biol. Cell 1992, 3, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaner, R.J.; Crystal, R.G. Compartmentalization of vascular endothelial growth factor to the epithelial surface of the human lung. Mol. Med. 2001, 7, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barratt, S.L.; Blythe, T.; Jarrett, C.; Ourradi, K.; Shelley-Fraser, G.; Day, M.J.; Qiu, Y.; Harper, S.; Maher, T.M.; Oltean, S.; et al. Differential Expression of VEGF-Axxx Isoforms Is Critical for Development of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.S.; Shen, F.; Young, W.L.; Yang, G.Y. Comparison of doxycycline and minocycline in the inhibition of VEGF-induced smooth muscle cell migration. Neurochem. Int. 2007, 50, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.K.; Llewellyn, O.P.; Bates, D.O.; Nicholson, L.B.; Dick, A.D. IL-10 regulation of macrophage VEGF production is dependent on macrophage polarisation and hypoxia. Immunobiology 2010, 215, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medford, A.R.; Ibrahim, N.B.; Millar, A.B. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and coreceptor expression in human acute respiratory distress syndrome. J. Crit. Care 2009, 24, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujio, Y.; Walsh, K. Akt mediates cytoprotection of endothelial cells by vascular endothelial growth factor in an anchorage-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 16349–16354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soker, S.; Fidder, H.; Neufeld, G.; Klagbrun, M. Characterization of novel vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors on tumor cells that bind VEGF165 via its exon 7-encoded domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 5761–5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medford, A.R.; Millar, A.B. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): Paradox or paradigm? Thorax 2006, 61, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.R.; England, K.M.; Goss, K.L.; Snyder, J.M.; Acarregui, M.J. VEGF induces airway epithelial cell proliferation in human fetal lung in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2001, 281, L1001–L1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varet, J.; Douglas, S.K.; Gilmartin, L.; Medford, A.R.; Bates, D.O.; Harper, S.J.; Millar, A.B. VEGF in the lung: A role for novel isoforms. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2016, 298, L768–L774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compernolle, V.; Brusselmans, K.; Acker, T.; Hoet, P.; Tjwa, M.; Beck, H.; PLaisance, S.; Dor, Y.; Keshet, E.; Lupu, F.; et al. Loss of HIF-2α and inhibition of VEGF impair fetal lung maturation, whereas treatment with VEGF prevents fatal respiratory distress in premature mice. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mura, M.; Han, B.; Andrade, C.F.; Seth, R.; Hwang, D.; Waddell, T.K.; Keshavjee, S.; Liu, M. The early responses of VEGF and its receptors during acute lung injury: Implication of VEGF in alveolar epithelial cell survival. Crit. Care 2006, 10, R130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.R.; Perkins, G.D.; Fujisawa, T.; Pettigrew, K.A.; Gao, F.; Ahmed, A.; Thickett, D.R. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes physical wound repair and is anti-apoptotic in primary distal lung epithelial and A549 cells. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 2164–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, H.; Kruger, S.; Hammerschmidt, S.; Wirtz, H. High concentrations of vascular endothelial growth factor reduce stretch-induced apoptosis of alveolar type II cells. Respirology 2010, 15, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, H.P.; Dixit, V.; Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces expression of the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and A1 in vascular endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 13313–13316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, H.P.; McMurtrey, A.; Kowalski, J.; Yan, M.; Keyt, B.A.; Dixit, V.; Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates endothelial cell survival through the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway. Requirement for Flk-1/KDR activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 30336–30343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, A.; Hood, J.D.; Frausto, R.; Stupack, D.G.; Cheresh, D.A. Role of Raf in vascular protection from distinct apoptotic stimuli. Science 2003, 301, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasahara, Y.; Tuder, R.M.; Taraseviciene-Stewart, L.; Le Cras, T.D.; Abman, S.; Hirth, P.K.; Waltenberger, J.; Voelkel, N.F. Inhibition of VEGF receptors causes lung cell apoptosis and emphysema. J. Clin. Investig. 2000, 106, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.; Rossiter, H.B.; Wagner, P.D.; Breen, E.C. Lung-targeted VEGF inactivation leads to an emphysema phenotype in mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2004, 97, 1559–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuder, R.M.; Kasahara, Y.; Voelkel, N.F. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors causes emphysema in rats. Chest 2000, 117, 281S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cras, T.D.; Spitzmiller, R.E.; Albertine, K.H.; Greenberg, J.M.; Whitsett, J.A.; Akeson, A.L. VEGF causes pulmonary hemorrhage, hemosiderosis, and air space enlargement in neonatal mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004, 287, L134–L142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, V.; Chho-Wing, R.; Chapoval, S.P.; Lee, C.G.; Tang, C.; Kim, Y.K.; Ma, B.; Baluk, P.; Lin, M.I.; McDonald, D.M.; et al. Essential role of nitric oxide in VEGF-induced, asthma-like angiogenic, inflammatory, mucus, and physiologic responses in the lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11021–11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, P.N.; Su, Y.N.; Li, H.; Huang, P.H.; Chien, C.T.; Lai, Y.L.; Lee, C.N.; Chen, C.A.; Cheng, W.F.; Wei, S.C.; et al. Overexpression of placenta growth factor contributes to the pathogenesis of pulmonary emphysema. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 169, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranieri, V.M.; Rubenfeld, G.D.; Thompson, B.T.; Ferguson, N.D.; Caldwell, E.; Fan, E.; Camporota, L.; Slutsky, A.S. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. ARDS Definition Task Force. JAMA 2012, 307, 2526–2533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ware, L.B.; Matthay, M.A. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1334–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barratt, S.; Medford, A.R.; Millar, A.B. Vascular endothelial growth factor in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respiration 2014, 87, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medford, A.R.; Godinho, S.I.; Keen, L.J.; Bidwell, J.L.; Millar, A.B. Relationship between vascular endothelial growth factor + 936 genotype and plasma/epithelial lining fluid vascular endothelial growth factor protein levels in patients with and at risk for ARDS. Chest 2009, 136, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medford, A.R.; Keen, L.J.; Bidwell, J.L.; Millar, A.B. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphism and acute respiratory distress syndrome. Thorax 2005, 60, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Cao, S.; Li, J.; Chang, J. Association between vascular endothelial growth factor + 936 genotype and acute respiratory distress syndrome in a Chinese population. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2011, 15, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Lu, H.; Zheng, X.; Huang, X. Effects of vascular endothelial growth factor in recovery phase of acute lung injury in mice. Lung 2015, 193, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thickett, D.R.; Armstrong, L.; Millar, A.B. A role for vascular endothelial growth factor in acute and resolving lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitre, B.; Boussat, S.; Jean, D.; Gouge, M.; Brochard, L.; Housset, B.; Adnot, S.; Delclaux, C. Vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis in the acute phase of experimental and clinical lung injury. Eur. Respir. J. 2001, 18, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azamfirei, L.; Gurzu, S.; Solomon, R.; Copotoiu, R.; Copotoiu, S.; Jung, I.; Tilinca, M.; Branzaniuc, K.; Corneci, D.; Szederjesi, J.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor: A possible mediator of endothelial activation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Minerva Anestesiol. 2010, 76, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maniscalco, W.M.; Watkins, R.H.; Finkelstein, J.N.; Campbell, M.H. Vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA increases in alveolar epithelial cells during recovery from oxygen injury. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1995, 13, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.H.; Waxman, A.B.; Lee, C.G.; Link, H.; Ra-bach, M.E.; Ma, B.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zhong, M.; Nakayama, K.; et al. Bcl-2-related protein A1 is an endogenous and cytokine-stimulated mediator of cytoprotection in hyperoxic acute lung injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaner, R.J.; Ladetto, J.V.; Singh, R.; Fukuda, N.; Matthay, M.A.; Crystal, R.G. Lung overexpression of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene induces pulmonary edema. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2000, 22, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Boyer, J.L.; Crystal, R.G. Genetic delivery of bevacizumab to suppress vascular endothelial growth factor-induced high-permeability pulmonary oedema. Hum. Gene Ther. 2009, 20, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, A.L.; Swigris, J.J.; Lezotte, D.C.; Norris, J.M.; Wilson, C.G.; Brown, K.K. Mortality from pulmonary fibrosis increased in the United States from 1992 to 2003. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 176, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navaratnam, V.; Fleming, K.M.; West, J.; Smith, C.J.; Jenkins, R.G.; Fogarty, A.; Hubbard, R.B. The rising incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the U.K. Thorax 2011, 66, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collard, H.R.; King, T.E., Jr.; Bartelson, B.B.; Vourlekis, J.S.; Schwarz, M.I.; Brown, K.K. Changes in clinical and physiologic variables predict survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 168, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghu, G.; Weycker, D.; Edelsberg, J.; Bradford, W.Z.; Oster, G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 174, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, P.W.; Albera, C.; Bradford, W.Z.; Costabel, U.; Glassberg, M.K.; Kardatzke, D.; King, T.K., Jr.; Lancaster, L.; Sahn, S.A.; Szwarcberg, J.; et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): Two randomised trials. Lancet 2016, 377, 1760–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenstein, A.L.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Myers, J.L. Diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia and distinction from other fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Hum. Pathol. 2008, 39, 1275–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosgrove, G.P.; Brown, K.K.; Schiemann, W.P.; Serls, A.E.; Parr, J.E.; Geraci, M.W.; Schwarz, M.I.; Cool, C.D.; Worten, G.S. Pigment epithelium-derived factor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A role in aberrant angiogenesis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 170, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebina, M.; Shimizukawa, M.; Shibata, N.; Kimura, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Endo, M.; Sasano, H.; Kondo, T.; Nukiwa, T. Heterogeneous increase in CD34-positive alveolar capillaries in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 169, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner-Warwick, M. Precapillary Systemic-Pulmonary Anastomoses. Thorax 1963, 18, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.L.; Katzenstein, A.L. Epithelial necrosis and alveolar collapse in the pathogenesis of usual interstitial pneumonia. Chest 1988, 94, 1309–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyama, S.; Sato, E.; Tsukadaira, A.; Haniuda, M.; Numanami, H.; Kurai, M.; Nagai, S.; Izumi, T. Vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA and protein expression in airway epithelial cell lines in vitro. Eur. Respir. J. 2002, 20, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, M.; Miyazaki, E.; Ito, T.; Hiroshige, S.; Nureki, S.I.; Ueno, T.; Takenaka, R.; Fukami, T.; Kumamoto, T. Significance of Serum Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Level in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Lung 2010, 188, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.C.; Cardoni, A.; Xiang, Z.Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor in bronchoalveolar lavage from normal subjects and patients with diffuse parenchymal lung disease. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2000, 135, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, L.A.; Habiel, D.M.; Hohmann, M.; Camelo, A.; Shang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Coelho, A.L.; Peng, X.; Gulati, M.; Crestani, B.; et al. Antifibrotic role of vascular endothelial growth factor in pulmonary fibrosis. JCI Insight 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simler, N.R.; Brenchley, P.E.; Horrocks, A.W.; Greaves, S.M.; Hasleton, P.S.; Egan, J.J. Angiogenic cytokines in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Thorax 2004, 59, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagan, K.A.; McMurtry, I.F.; Rodman, D.M. Role of endothelin-1 in lung disease. Respir. Res. 2001, 2, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzoni, E.A. Neovascularisation in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: too much or too little? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 169, 1179–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzouvelekis, A.; Anevlavis, S.; Bouros, D. Angiogenesis in interstitial lung diseases: A pathogenetic hallmark or a bystander? Respir. Res. 2006, 7, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Chen, T.T.; Barber, C.L.; Jordan, M.C.; Murdock, J.; Desai, S.; Ferrara, N.; Nagy, A.; Roos, K.P.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L. Autocrine VEGF signaling is required for vascular homeostasis. Cell 2007, 130, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockmann, C.; Kerdiles, Y.; Nomaksteinsky, M.; Weidemann, A.; Takeda, N.; Doedens, A.; Torres-Collado, A.X.; Iruela-Arispe, L.; Nizet, V.; Johnson, R.S. Loss of myeloid cell-derived vascular endothelial growth factor accelerates fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4329–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, N.; Kuwano, K.; Yamada, M.; Hagimoto, N.; Hiasa, K.; Egashira, K.; Nakashima, N.; Maeyama, T.; Yoshimi, M.; Nakanishi, Y. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor gene therapy attenuates lung injury and fibrosis in mice. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, N.I.; Roth, G.J.; Hilberg, F.; Muller-Quernheim, J.; Prasse, A.; Zissel, G.; Schnapp, A.; Park, J.E. Inhibition of PDGF, VEGF and FGF signalling attenuates fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 29, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, L.; Farkas, D.; Ask, K.; Moller, A.; Gauldie, J.; Margetts, P.; Inman, M.; Kolb, M. VEGF ameliorates pulmonary hypertension through inhibition of endothelial apoptosis in experimental lung fibrosis in rats. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1298–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selman, M.; Pardo, A.; King, T.E., Jr. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: Insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P.; Rossi, G.; Cavazza, A.; Bonifazi, M.; Paladini, I.; Bonella, F.; Sverzellati, N.; Costabel, U. Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis: A Comprehensive Review. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 25, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Selman, M.; Pardo, A.; Barrera, L.; Estrada, A.; Watson, S.R.; Wilson, K.; Aziz, N.; Kaminski, N.; Zlotnik, A. Gene expression profiles distinguish idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis from hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 173, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, A.H.; Matsuoka, M.; Ghoda, L.Y.; Homer, R.J.; Enelow, R.I. Chronic inflammation and lung fibrosis: Pleotropic syndromes but limited distinct phenotypes. Mucosal Immunol. 2012, 5, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, S.; Verleden, S.E.; Vanaudenaerde, B.M.; Wynants, M.; Dooms, C.; Yserbyt, J.; Somers, J.; Verbeken, E.K.; Verleden, G.M.; Wuyts, W.A. Multiplex protein profiling of bronchoalveolar lavage in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2013, 8, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jinta, T.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kishi, M.; Akashi, T.; Takemura, T.; Inase, N.; Yoshizawa, Y. The pathogenesis of chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis in common with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Expression of apoptotic markers. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010, 134, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, C.; Ruiz, V.; Gaxiola, M.; Carrillo, G.; Selman, M. Angiogenesis in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 111, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, M.; Mouri, T.; Niisato, M.; Nitanai, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Ogasawara, M.; Endo, R.; Konishi, K.; Sugai, T.; Sawai, T.; et al. Lymphangiogenic factors are associated with the severity of hypersensitivity pneumonitis. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2015, 2, e000085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alitalo, K. The lymphatic vasculature in disease. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutsche, M.; Rosen, G.D.; Swigris, J.J. Connective Tissue Disease-associated Interstitial Lung Disease: A review. Curr. Respir. Care Rep. 2012, 1, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrick, A.L. Pathogenesis of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatology 2005, 44, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hal, T.W.; van Bon, L.; Radstake, T.R. A system out of breath: How hypoxia possibly contributes to the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Int. J. Rheumatol. 2011, 824972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, V.D.; Medsger, T.A. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007, 66, 940–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freemont, A.J.; Hoyland, J.; Fielding, P.; Hodson, N.; Jayson, M.I. Studies of the microvascular endothelium in uninvolved skin of patients with systemic sclerosis: Direct evidence for a generalized microangiopathy. Br. J. Dermatol. 1992, 126, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, R.J.; Freemont, A.J.; Jones, C.J.; Hoyland, J.; Fielding, P. Sequential dermal microvascular and perivascular changes in the development of scleroderma. J. Pathol. 1992, 166, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roumm, A.D.; Whiteside, T.L.; Medsger, T.A., Jr.; Rodnan, G.P. Lymphocytes in the skin of patients with progressive systemic sclerosis. Quantification, subtyping, and clinical correlations. Arthritis Rheum. 1984, 27, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenig, M.; Joyal, F.; Fritzler, M.J.; Roussin, A.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Boire, G.; Goulet, J.R.; Rich, E.; Grodzicky, T.; Raymond, Y.; et al. Autoantibodies and microvascular damage are independent predictive factors for the progression of Raynaud’s phenomenon to systemic sclerosis: A twenty-year prospective study of 586 patients, with validation of proposed criteria for early systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58, 3902–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulli, A.; Ruaro, B.; Alessandri, E.; Pizzorni, C.; Cimmino, M.A.; Zampogna, G.; Gallo, M.; Cutolo, M. Correlations between nailfold microangiopathy severity, finger dermal thickness and fingertip blood perfusion in systemic sclerosis patients. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distler, O.; Distler, J.H.; Scheid, A.; Acker, T.; Hirth, A.; Rethage, J.; Michel, B.A.; Gay, R.E.; Müller-Ladner, U.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; et al. Uncontrolled expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors leads to insufficient skin angiogenesis in patients with systemic sclerosis. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marti, H.H.; Risau, W. Systemic hypoxia changes the organ-specific distribution of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 15809–15814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distler, O.; Del Rosso, A.; Giacomelli, R.; Cipriani, P.; Conforti, M.L.; Guiducci, S.; Gay, R.E.; Michel, B.A.; Brühlmann, P.; Müller-Ladner, U.; et al. Angiogenic and angiostatic factors in systemic sclerosis: Increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor are a feature of the earliest disease stages and are associated with the absence of fingertip ulcers. Arthritis Res. 2002, 4, R11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avouac, J.; Wipff, J.; Goldman, O.; Ruiz, B.; Couraud, P.O.; Chiocchia, G.; Kahan, A.; Boileau, C.; Uzan, G.; Allanore, Y. Angiogenesis in Systemic Sclerosis Impaired Expression of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 1 in Endothelial Progenitor-Derived Cells Under Hypoxic Conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58, 3550–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manetti, M.; Guiducci, S.; Romano, E.; Bellando-Randone, S.; Lepri, G.; Bruni, C.; Conforti, M.L.; Ibba-Manneschi, L.; Matucci-Cerinic, M. Increased plasma levels of the VEGF165b splice variant are associated with the severity of nailfold capillary loss in systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 1425–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santis, M.; Bosello, S.L.; Capoluongo, E.; Inzitari, R.; Peluso, G.; Lulli, P.; Zizzo, G.; Bocci, M.; Tolusso, B.; Zuppi, C.; et al. A vascular endothelial growth factor deficiency characterises scleroderma lung disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 1461–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santis, M.; Ceribelli, A.; Cavaciocchi, F.; Crotti, C.; Massarotti, M.; Belloli, L.; Marasini, B.; Isailovic, N.; Generali, E.; Selmi, C. Nailfold videocapillaroscopy and serum VEGF levels in scleroderma are associated with internal organ involvement. Auto-Immun. Highlights 2016, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Huang, J.; Maier, C.; Zhang, Y.; Soare, A.; Dees, C.; Beyer, C.; Harre, U.; Chen, C.W.; Distler, O.; Schett, G.; et al. Nintedanib inhibits macrophage activation and ameliorates vascular and fibrotic manifestations in the Fra2 mouse model of systemic sclerosis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1941–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundtman, C.; Tham, E.; Ulfgren, A.K.; Lundberg, I.E. Vascular endothelial growth factor is highly expressed in muscle tissue of patients with polymyositis and patients with dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 58, 3224–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpi, N.; Pecorelli, A.; Lorenzoni, P.; Di Lazzaro, F.; Belmonte, G.; Agliano, M.; Cantarini, L.; Giannini, F.; Grasso, G.; Valacchi, G. Antiangiogenic VEGF isoform in inflammatory myopathies. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 219313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, K.; Kubo, M.; Kadono, T.; Yazawa, N.; Ihn, H.; Tamaki, K. Serum concentrations of vascular endothelial growth factor in collagen diseases. Br. J. Dermatol. 1998, 139, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaseanu, C.; Tudor, S.; Tamsulea, I.; Marta, D.; Manea, G.; Moldoveanu, E. Vascular endothelial growth factor, lipoporotein-associated phospholipase A2, sP-selectin and antiphospholipid antibodies, biological markers with prognostic value in pulmonary hypertension associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic lupus erithematosus. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2007, 12, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Distler, J.H.; Strapatsas, T.; Huscher, D.; Dees, C.; Akhmetshina, A.; Kiener, H.P.; Tarner, I.H.; Maurer, B.; Walder, M.; Michel, B.; et al. Dysbalance of angiogenic and angiostatic mediators in patients with mixed connective tissue disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwakawa, J.; Matsuyama, W.; Kubota, S.; Mitsuyama, H.; Suetsugu, T.; Watanabe, M.; Higashimoto, I.; Osame, M.; Arimura, K. Increased serum vascular endothelial growth factor levels in microscopic poly angiitis with pulmonary involvement. Respir. Med. 2006, 100, 1724–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hashimoto, N.; Iwasaki, T.; Kitano, M.; Ogata, A.; Hamano, T. Levels of vascular endothelial growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor in sera of patients with rheumatic diseases. Mod. Rheumatol. 2003, 13, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuryliszyn-Moskal, A.; Klimiuk, P.A.; Sierakowski, S.; Ciolkiewicz, M. A study on vascular endothelial growth factor and endothelin-1 in patients with extra-articular involvement of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2006, 25, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, D.A.; McKirnan, M.D.; Canestrelli, I.; Gao, M.H.; Dalton, N.; Lai, N.C.; Roth, D.M.; Hammond, H.K. Intracoronary delivery of an adenovirus encoding fibroblast growth factor-4 in myocardial ischemia: Effect of serum antibodies and previous exposure to adenovirus. Hum. Gene Ther. 2006, 17, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, N.; Rück, A.; Källner, G.; Y-Hassan, S.; Blomberg, P.; Islam, K.B.; van der Linden, J.; Lindblom, D.; Nygren, A.T.; Lind, B.; et al. Effects of intramyocardial injection of phVEGF-A165 as sole therapy in patients with refractory coronary artery disease—12-Month follow-up: Angiogenic gene therapy. J. Intern. Med. 2001, 250, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barratt, S.L.; Flower, V.A.; Pauling, J.D.; Millar, A.B. VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) and Fibrotic Lung Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19051269

Barratt SL, Flower VA, Pauling JD, Millar AB. VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) and Fibrotic Lung Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(5):1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19051269

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarratt, Shaney L., Victoria A. Flower, John D. Pauling, and Ann B. Millar. 2018. "VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) and Fibrotic Lung Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, no. 5: 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19051269

APA StyleBarratt, S. L., Flower, V. A., Pauling, J. D., & Millar, A. B. (2018). VEGF (Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor) and Fibrotic Lung Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 19(5), 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19051269