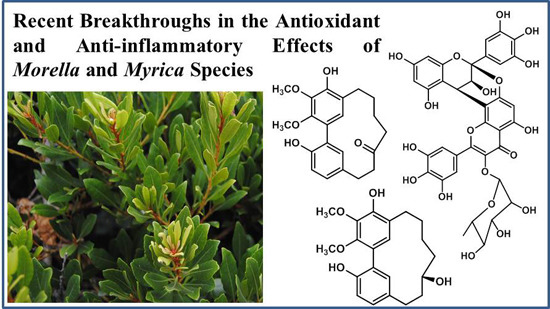

Recent Breakthroughs in the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Morella and Myrica Species

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Myrica and Morella Genera

| Species Name a | Distribution | Traditional Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Morella | ||

| Morella adenophora (Hance) J. Herb. | China and Taiwan | Roots and bark to treat bleeding, diarrhea and stomach pain [33]. |

| Morella nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb. | China | Fruits are beneficial for dyspepsia [34]. Roots are used to treat bleeding, diarrhea, stomach pain, burns, and skin diseases [35]. Bark is used to treat enteritis [36]. |

| Morella serrata (Lam.) Killick | South Africa and Southern African countries extending into tropical Africa | Used to treat asthma, coughing and shortness of breath [37]. The decoction of the root is used to treat painful menstruation, cold, coughs and headaches and to enhance male sexual performance [38]. It is also used in the management of sugar related disorder and as laxative to treat constipation. The stem bark is used to treat headache [39]. |

| Morella arborea (Hutch.) Cheek | Cameroon | Bark decoction used to treat fevers and inflammation [40]. |

| Morella cerifera (L.) Small | North America | Herb decoction or tincture used as astringent, diaphoretic, as a circulatory stimulant, to treat irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis, digestive system disorders, diarrhea, dysentery, leukorrhea, mucous colitis, colds, stomatitis, sore throat, measles and scarlet fever, convulsions, nasal catarrh and jaundice [41]. |

| Morella salicifolia (Hochst. ex A.Rich.) Verdc. & Polhill | Southeast Africa, Ethiopia and Saudi Arabia | Roots infusion is used to treat gastro-intestinal disorder [42] while roots and bark used in the treatment of headache [43], pain, inflammation and respiratory diseases [44]. |

| Myrica | ||

| Myrica rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc. | China, Japan, Taiwan and Korea | The various organs are used to treat gastrointestinal diseases, headaches, burns and skin diseases. Leaves are used to treat inflammatory diseases [45]. |

| Myrica esculenta Buch.- Ham. ex D. Don | India, South China, Malaysia, Japan, Vietnam and Nepal | Ayuverdic medicine use decoction of bark to treat asthma, bronchitis, fever, lung infection, dysentery, toothache and wounds [46–48]; leaf, root, bark and fruits juice for worms, jaundice and dysentery [48]; Vietnamese folk medicine uses bark to treat catarrhal fever, cough, sore throat and skin disease [49]. |

| Myrica gale L. | Europe, Siberia, Canada and Northern USA | Used in the treatment of ulcers, intestinal worms, cardiac disorders and aching muscles [50]. |

| Myrica nagi Thunb. | China, Malaya Islands, Pakistan and Nepal | Bark finds its application in reducing inflammations [51] to treat cardiac diseases, bronchitis, gonorrhea, diuresis, dysentery, epilepsy, gargle, heamoptysis, hypothermia, catarrh, headache, menorrhagia, putrid sores, typhoid, face palsy and paralysis and wounds [51,52]. Fruit wax or oil is used for treating ulcers [53], bleeding piles, body ache, toothache and for regulating the menstrual cycle [52]. |

3. Isolated Compounds from Morella/Myrica Species

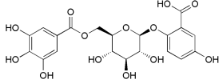

| Compound Name (Number) | Chemical Structure | Current Species Name a, Part of Plant |

|---|---|---|

| Diarylheptanoids | ||

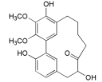

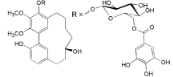

| Myricanone (1) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; Mo. arborea (Hutch.) Cheek, twigs [54]; Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb, roots [34]; Mo. cerifera (L.) Small, bark [59], twigs [60]; My. gale L. (syn. My. gale var. tormentosa L.), branches [61]; My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., bark [62] |

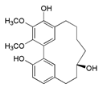

| 5-Deoxymyricanone (2) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58] |

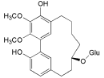

| Myricananin C (3) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb., roots [63] |

| 12-Hydroxymyricanone (4) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb, roots [63]; My. gale L. (syn. My. gale var tormentosa L.), branches [61] |

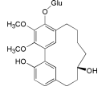

| Porson b (5) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb, roots [34]; My. gale L. (syn. My. gale var tormentosa L.), branches [61] |

| Myricananin D (6) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., [58]; Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb, roots [63] |

| Alnusonol (7) |  | Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb, roots [63] |

| Actinidione (8) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb, roots [63] |

| Galeon (9) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; My. gale L. (syn. My. gale var tormentosa L.), branches [64] |

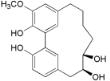

| Myricanol (10) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; Mo. arborea (Hutch.) Cheek, root and stem barks [40], twigs [54]; Mo. cerifera (L.) Small, bark [59], root-bark [65]; My. esculenta Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don, leaves [66]; Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb, roots [34]; My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., bark [62] |

| Myricanol 11-O-β-d-xylopyranoside (11) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; Mo. arborea (Hutch.) Cheek, root and stem barks [40] |

| Myricanol 11-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (12) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb, roots [35]; My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., bark [62] |

| Myricanol 5-O-β-d-glucopyranoside (13) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., bark [62] |

| Myricanol 5-O-β-d-(6′-O-galloyl)-glucopyranoside (14) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., bark [62] |

| Myricananin A (15) |  | Mo. nana (A. Chev.) J. Herb, roots [63] |

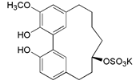

| Juglanin B-11( R)-O-sulphate (16) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., leaves [67] |

| Flavonoids | ||

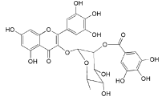

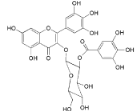

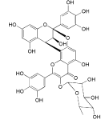

| Myricetin 3-O-(2-O-galloyl)-α-l-rhamnopyranoside (17) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., leaves [68] |

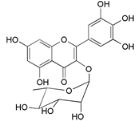

| Myricetin 3-O-(2-O-galloyl)-β-d-galactopyranoside (18) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., leaves [68] |

| Quercetin 3-O-(2-O-galloyl)-β-d-galactopyranoside (19) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., leaves [68] |

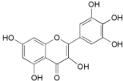

| Myricetin (20) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., leaves [68], bark [62]; Mo. cerifera (L.) Small, root-bark [65]; My. esculenta Buch.- Ham. ex D.Don, leaves [66] |

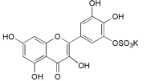

| Myricetin-3′-O-sulfate (21) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., leaves [67] |

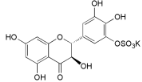

| Ampelopsin 3′-O-sulfate (22) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., leaves [67] |

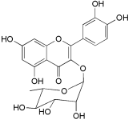

| Myricitrin (23) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., leaves [68], bark [62]; Mo. cerifera (L.) Small, root-bark [65]; My. esculenta Buch.- Ham. ex D.Don, leaves [66] |

| Quercitrin (24) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58] |

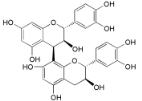

| Adenodimerin A (25) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58] |

| Myricitrin (23) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., leaves [68], bark [62]; Mo. cerifera (L.) Small, root-bark [65]; My. esculenta Buch.- Ham. ex D.Don, leaves [66] |

| Procyanidin B2 (26) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., fruit pulp [69] |

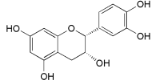

| (−)-Epicathechin (27) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., fruit pulp [69]; My. gale L., aerial parts [70] |

| Cyanidin 3-O-glucopyranoside (28) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold & Zucc., fruits [45] |

| Miscellaneous Compounds | ||

| Myricalactone (29) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; My. gale L. (syn. My. gale var tormentosa L.), stem [64] |

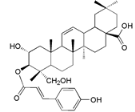

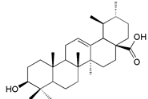

| 3β-Trans-p-coumaroyloxy-2α,23-dihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (30) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58] |

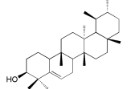

| Rhoiptelenol (31) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold&Zucc., bark [71] |

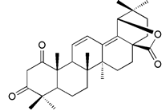

| Ursolic acid (32) |  | My. rubra (Lour.) Siebold&Zucc., bark [71] |

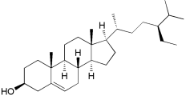

| β-Sitosterol (33) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58]; My. esculenta Buch.- Ham. ex D.Don, leaves [72] |

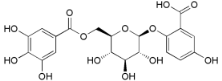

| 6′-O-galloyl orbicularin (34) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58] |

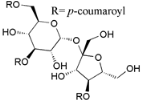

| Myricadenin A (35) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58] |

| Myricadenin B (36) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58] |

| 6′-O-galloyl orbicularin (34) |  | Mo. adenophora (Hance) J. Herb., roots [58] |

4. Biological Activities

4.1. Antioxidant Activity

| Compound | Antioxidant Activity (Positive Control Used) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | DPPH: EC50 = 202.7 ± 15.8 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 19.6 ± 0.7 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 2 | DPPH: EC50 ≥ 250 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 102.7 ± 12.4 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 3 | DPPH: EC50 = 16.3 ± 2.8 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 12.0 ± 0.6 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 5 | DPPH: EC50 > 250 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 73.7 ± 0.1 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 6 | DPPH: EC50 = 87.8 ± 0.0 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] EC50 = 14.9 µM (α-Tocopherol EC50 = 27.1 µM) [62] ABTS: EC50 = 85.9 ± 2.7 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 8 | DPPH: EC50 = 195.4 ± 2.2 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 89.1 ± 0.6 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 9 | DPPH: EC50 = 51.1 ± 2.9 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 26.8 ± 1.6 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 10 | DPPH: EC50 = 198.9 ± 9.1 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 22.3 ± 0.6 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 11 | DPPH: EC50 = 81.6 ± 3.7 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 25.3 ± 2.6 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 12 | DPPH: EC50 > 250 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] EC50 = 12.9 µM (α-Tocopherol EC50 = 27.1 µM) [62] ABTS: EC50 = 19.6 ± 0.2 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 13 | DPPH: EC50 > 100 µM (α-Tocopherol EC50 = 27.1 µM) [62] | |

| 14 | DPPH: EC50 = 6.8 µM (α-Tocopherol EC50 = 27.1 µM) [62] | |

| 17 | NBT: EC50 = 0.48 ± 0.02 µM (Allopurinol EC50 = 1.23 ± 0.22 µM) [68] | |

| 18 | NBT: EC50 = 0.67 ± 0.03 µM (Allopurinol EC50 = 1.23 ± 0.22 µM) [68] | |

| 19 | NBT: EC50 = 1.57 ± 0.30 µM (Allopurinol EC50 = 1.23 ± 0.22 µM) [68] | |

| 20 | DPPH: EC50 = 15.9 ± 0.0 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] EC50 = 2.0 µM (α-Tocopherol EC50 = 27.1 µM) [62] ABTS: EC50 = 15.6 ± 1.4 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] NBT: EC50 = 7.40 ± 0.24 µM (Allopurinol EC50 = 1.23 ± 0.22 µM) [68] | |

| 23 | DPPH: EC50 = 2.2 µM (α-Tocopherol EC50 = 27.1 µM) [62] NBT: EC50 = 5.17 ± 0.23 µM (Allopurinol EC50 = 1.23 ± 0.22 µM) [68] Significantly inhibits acrylamide mediated ROS generation and cytotoxicity in Caco-2 cells (p < 0.05) at concentrations ranging from 5.4–21.6 µM (2.5–10 µg/mL) [81]. Significantly attenuated intracellular ROS production at 0.1–10 µM and inhibits lipid peroxidation in brain mitochondria (EC50 = 3.19 ± 0.34 µM) [82] | |

| 25 | DPPH: EC50 = 7.9 ± 0.3 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 7.5 ± 0.4 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 26 | DPPH: EC50 = 3.6 µM (BHA EC50 = 14.2 µM) a [69] | |

| 27 | DPPH: EC50 = 9.8 µM (BHA EC50 = 14.2 µM) a [69] | |

| 28 | DPPH activity is directly correlated with its concentration [45] | |

| 29 | DPPH: EC50 > 250 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 41.9 ± 0.6 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 30 | DPPH: EC50 > 250 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 22.25 ± 0.4 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 > 200 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 34 | DPPH: EC50 > 250 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 29.3 ± 0.4 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 35 | DPPH: EC50 > 250 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58]; EC50 = 20.5 µM (α-Tocopherol EC50 = 27.1 µM) [62] ABTS: EC50 = 175.4 ± 3.9 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] | |

| 36 | DPPH: EC50 > 250 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] ABTS: EC50 = 45.8 ± 1.7 µM (Ascorbic acid EC50 = 23.3 ± 0.2 µM) [58] |

4.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

| Compound | Anti-Inflammatory Activity (Positive Control Used) a | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | IC50 (iNOS) = 1.0 ± 0.1 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 39.5 ± 2.7 µM Aminoguanidine IC50 = 22.2 ± 3.6 µM) | [58] |

| 3 | IC50 (iNOS) = 13.0 ± 0.9 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 39.5 ± 2.7 µM Aminoguanidine IC50 = 22.2 ± 3.6 µM) | [58] |

| IC50 (NO) = 63.51 µM ( N-monomethyl-l-arginine IC50 = 64.24 µM) * | [63] | |

| 4 | IC50 (NO) = 30.19 µM ( N-monomethyl-l-arginine IC50 = 64.24 µM) | [63] |

| 5 | IC50 (iNOS) = 46.9 ± 3.1 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 39.5 ± 2.7 µM Aminoguanidine IC50 = 22.2 ± 3.6 µM) | [58] |

| 6 | IC50 (NO) = 23 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 28 µM) | [71] |

| 7 | IC50 (NO) = 46.18 µM ( N-monomethyl-l-arginine IC50 = 64.24 µM) | [63] |

| 10 | IC50 (iNOS) = 7.5 ± 2.7 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 39.5 ± 2.7 µM Aminoguanidine IC50 = 22.2 ± 3.6 µM) | [58] |

| 15 | IC50 (NO) = 45.32 µM ( N-monomethyl-l-arginine IC50 = 64.24 µM) | [63] |

| 16 | IC50 (TNF-α) = 20.1 ± 2.14 µM (PDTC IC50 = 16.8 ± 2.13 µM; Quercetin IC50 = 13.6 ± 0.81 µM); IC50 (IL-1β) = 22.9 ± 0.75 µM (PDTC IC50 = 18.0 ± 1.74 µM; Quercetin IC50 = 16.9 ± 0.34 µM) IC50 (IL-6) = 22.7 ± 1.61 µM (PDTC IC50 = 16.8 ± 2.40 µM Quercetin IC50 = 16.8 ± 0.13 µM) | [67] |

| 17 | IC50 (TNF-α) = 12.90 ± 0.84 µM (PDTC IC50 = 25.32 ± 0.51 µM) IC50 (IL-1β) = 18.06 ± 3.16 µM (PDTC IC50 = 23.61 ± 2.17 µM) IC50 (IL-6) = 7.69 ± 2.14 µM (PDTC IC50 = 21.41 ± 1.69 µM) | [68] |

| 18 | IC50 (TNF-α) = 8.65 ± 1.62 µM (PDTC IC50 = 25.32 ± 0.51 µM) IC50 (IL-1β) = 18.97 ± 2.15 µM (PDTC IC50 = 23.61 ± 2.17 µM) IC50 (IL-6) = 13.14 ± 0.44 µM (PDTC IC50 = 21.41 ± 1.69 µM) | [68] |

| 19 | IC50 (TNF-α) = 1.55 ± 1.15 µM (PDTC IC50 = 25.32 ± 0.51 µM) IC50 (IL-1β) = 17.84 ± 1.56 µM (PDTC IC50 = 23.61 ± 2.17 µM) IC50 (IL-6) = 8.63 ± 2.14 µM (PDTC IC50 = 21.41 ± 1.69 µM) | [68] |

| 20 | IC50 (TNF-α) = 65.21 ± 3.11 µM (PDTC IC50 = 25.32 ± 0.51 µM) | [68] |

| IC50 (IL-1β) = 22.81 ± 2.51 µM (PDTC IC50 = 23.61 ± 2.17 µM) IC50 (IL-6) = 23.65 ± 6.14 µM (PDTC IC50 = 21.41 ± 1.69 µM) IC50 (NO) = 99 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 28 µM) | [71] | |

| 21 | IC50 (TNF-α) = 19.9 ± 2.45 µM (PDTC IC50 = 16.8 ± 2.13 µM Quercetin IC50 = 13.6 ± 0.81 µM) IC50 (IL-1β) = 20.2 ± 1.42 µM (PDTC IC50 = 18.0 ± 1.74 µM; Quercetin IC50 = 16.9 ± 0.34 µM) IC50 (IL-6) = 22.2 ± 1.14 µM (PDTC IC50 = 16.8 ± 2.40 µM Quercetin IC50 = 16.8 ± 0.13 µM) | [67] |

| 22 | IC50 (TNF-α) = 20.1 ± 2.14 µM (PDTC IC50 = 16.8 ± 2.13 µM Quercetin IC50 = 13.6 ± 0.81 µM) IC50 (IL-1β) = 22.9 ± 0.75 µM (PDTC IC50 = 18.0 ± 1.74 µM Quercetin IC50 = 16.9 ± 0.34 µM) IC50 (IL-6) = 22.7 ± 1.61 µM (PDTC IC50 = 16.8 ± 2.40 µM Quercetin IC50 = 16.8 ± 0.13 µM) | [67] |

| 23 | IC50 (iNOS) = 30.9 ± 2.1 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 39.5 ± 2.7 µM Aminoguanidine IC50 = 22.2 ± 3.6 µM) | [58] |

| IC50 (TNF-α) = 25.20 ± 0.54 µM (PDTC IC50 = 25.32 ± 0.51 µM) IC50 (IL-1β) = 25.04 ± 0.48 µM (PDTC IC50 = 23.61 ± 2.17 µM) IC50 (IL-6) = 13.41 ± 1.81 µM (PDTC IC50 = 21.41 ± 1.69 µM) | [68] | |

| IC50 (NO) > 100 µM | [71] | |

| 24 | IC50 (iNOS) = 45.4 ± 0.89 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 39.5 ± 2.7 µM Aminoguanidine IC50 = 22.2 ± 3.6 µM) | [58] |

| 28 | IC50 (NO) = 30.19 µM ( N-monomethyl-l-arginine IC50 = 64.24 µM) | [63] |

| 31 | IC50 (NO) = 24 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 28 µM | [71] |

| 32 | IC50 (NO) between 3–10 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 28 µM) | [71] |

| 33 | IC50 (iNOS) = 39.5 ± 2.7 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 39.5 ± 2.7 µM Aminoguanidine IC50 = 22.2 ± 3.6 µM) | [58] |

| 35 | IC50 (iNOS) = 18.1 ± 1.5 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 39.5 ± 2.7 µM Aminoguanidine IC50 = 22.2 ± 3.6 µM) | [58] |

| IC50 (NO) = 23 µM ( Nῳ-nitro-l-arginine IC50 = 28 µM) | [71] |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive oxygen species: Metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phaniendra, A.; Jestadi, D.B.; Periyasamy, L. Free radicals: Properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Ind. J. Clin. Biochem. 2015, 30, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newsholme, P.; Rebelato, E.; Abdulkader, F.; Krause, M.; Carpinelli, A.; Curi, R. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species generation, antioxidant defenses, and β-cell function: A critical role for amino acids. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 214, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reczek, C.R.; Chandel, N.S. ROS-dependent signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 33, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Wang, K.; Deng, L.; Chen, Y.; Nice, E.C.; Huang, C. Redox regulation of inflammation: Old elements, a new story. Med. Res. Rev. 2015, 35, 306–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahal, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.; Yadav, B.; Tiwari, R.; Chakraborty, S.; Dhama, K. Oxidative stress, prooxidants, and antioxidants: The interplay. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 761264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bani, D.; Bencini, A. Developing ROS scavenging agents for pharmacological purposes: Recent advances in design of manganese-based complexes with anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive activity. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 4431–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-R.; Won, S.J.; Fabian, C.; Kang, M.-G.; Szardenings, M.; Shin, M.-G. Mitochondrial DNA aberrations and pathophysiological implications in hematopoietic diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases, and cancers. Ann. Lab. Med. 2015, 35, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salisbury, D.; Bronas, U. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: Impact on endothelial dysfunction. Nurs. Res. 2015, 64, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, K.; Dhar, I. Oxidative stress as a mechanism of added sugar-induced cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Angiol. 2014, 23, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hroudová, J.; Singh, N.; Fišar, Z. Mitochondrial dysfunctions in neurodegenerative diseases: Relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 175062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala-Peña, S. Role of oxidative DNA damage in mitochondrial dysfunction and Huntington’s disease pathogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 62, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunakaran, U.; Park, K.-G. A systematic review of oxidative stress and safety of antioxidants in diabetes: Focus on islets and their defense. Diabetes Metab. J. 2013, 37, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia-Melo, C.; Hewitt, G.; Passos, J.F. Telomeres, oxidative stress and inflammatory factors: Partners in cellular senescence? Longev. Healthspan 2014, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumalic, S.I.; Pinter, B. Review of clinical trials on effects of oral antioxidants on basic semen and other parameters in idiopathic oligoasthenoteratozoospermia. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 426951. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, S.K. Can antioxidants protect against disuse muscle atrophy? Sports Med. 2014, 44, S155–S165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginter, E.; Simko, V.; Panakova, V. Antioxidants in health and disease. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2014, 115, 603–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanchev, V.D.; Kasaikina, O.T. Bio-antioxidants—A chemical base of their antioxidant activity and beneficial effect on human health. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 4784–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Alarcóna, C.; Denicola, A. Evaluating the antioxidant capacity of natural products: A review on chemical and cellular-based assays. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 763, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scartezzini, P.; Speroni, E. Review on some plants of Indian traditional medicine with antioxidant activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 71, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches-Silva, A.; Costa, D.; Albuquerque, T.G.; Buonocore, G.G.; Ramos, F.; Castilho, M.C.; Machado, A.V.; Costa, H.S. Trends in the use of natural antioxidants in active food packaging: A review. Food Addit. Contam. 2014, 31, 374–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. Relationship between antioxidants and acrylamide formation: A review. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-Q. Antioxidants may not always be beneficial to health. Nutrition 2014, 30, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Khan, S.; Avula, B.; Lata, H.; Yang, M.H.; ElSohly, M.A.; Khan, I.A. Assessment of total phenolic and flavonoid content, antioxidant properties, and yield of aeroponically and conventionally grown leafy vegetables and fruit crops: A comparative study. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguet, V.; Gouy, M.; Normand, P.; Zimpfer, J.F.; Fernandez, M.P. Molecular phylogeny of Myricaceae: A reexamination of host-symbiont specificity. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2005, 34, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanthan, M.; Misra, A.K. Molecular approach to the classification of medicinally important actinorhizal genus Myrica. Indian J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, A.D. The morphology and relationships of the Myricaceae. In Evolution, Systematics, and Fossil History of the Hamamelidae; Crane, P.R., Blackmore, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1989; Volume 2, pp. 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Staples, G.W.; Imada, C.T.; Herbst, D.R. New Hawaiian plant records for 2000. Bish. Mus. Occas. Pap. 2002, 68, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, J. New combinations and a new species in Morella (Myricaceae). Novon 2005, 15, 293–295. [Google Scholar]

- Gtari, M.; Dawson, J.O. An overview of actinorhizal plants in Africa. Funct. Plant Biol. 2011, 38, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Traditional Medicine Strategy: 2014–2023. Available online: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/traditional/trm_strategy14_23/en/ (accessed on 10 March 2015).

- Li, T.S.C. Taiwanese Native Medicinal Plants: Phytopharmacology and Therapeutic Values; CRC Press: Florida, FL, USA, 2006; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.-F.; Lu, Q.; Guo, L.; Mei, R.-Q.; Liang, H.-X.; Luo, D.-Q.; Cheng, Y.-X. Myricananone and myricananadiol: Two new cyclic diarylheptanoids from the roots of Myrica nana. Helv. Chim. Acta 2007, 90, 1691–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-F.; Zhang, C.-L.; Lu, Q.; Yu, Y.-F.; Zhong, H.-M.; Long, C.-L.; Cheng, Y.-X. Three new diarylheptanoids from Myrica nana. Helv. Chim. Acta 2009, 92, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Xiao, C.; Pei, S. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants at periodic markets of Honghe Prefecture in Yunnan Province, SW China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 117, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, E.; Lotter, M.; McCleland, W. Trees and shrubs of Mpumalamga and Kruger National Park; Jacana Publishers: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2002; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Moffet, R. Sesotho Plant and Animal Names, and Plants Used by the Basotho; Sun Press: Bloemfontein, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ashafa, A.O.T. Medicinal potential of Morella serata (Lam.) Killick (Myricaceae) root extracts: Biological and pharmacological activities. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tene, M.; Wabo, K.H.; Kamnaing, P.; Tsopmo, A.; Tane, P.; Ayafora, J.F.; Sterner, O. Diarylheptanoids from Myrica arborea. Phytochemistry 2000, 54, 975–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, D.; Hoffmann, F.N. Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine; Inner Traditions/Bear & Company: Vermont, VT, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kefalew, A.; Asfaw, Z.; Kelbessa, E. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in Ada’a District, East Shewa Zone of Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teklay, A.; Abera, B.; Giday, M. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Kilte Awulaelo District, Tigray Region of Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlage, C.; Mabula, C.; Mahunnah, R.L.A.; Heinrich, M. Medicinal plants of the Washambaa (Tanzania): Documentation and ethnopharmacological evaluation. Plant Biol. 2000, 2, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Huang, H.; Xu, C.; Li, X.; Chen, K. Biological activities of extracts from Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.): A review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2013, 68, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirtikar, K.R.; Basu, B.D. Indian Medicinal Plants, 2nd ed.; International Book Distributors: New Delhi, India, 1999; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni’s, K.M. Indian Materia Medica, 3rd ed.; Popular Prakashan Pvt Ltd.: Mumbai, India, 2002; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Laloo, R.C.; Kharlukhi, S.; Jeeva, S.; Mishra, B.P. Status of medicinal plants in the disturbed and the undisturbed sacred forest of Meghalaya, Northeast India: Population structure and regeneration efficacy of some important species. Curr. Sci. 2006, 90, 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Bich, D.H.; Chung, D.Q.; Chuong, B.X.; Dong, N.T.; Dam, D.T.; Hien, P.V.; Lo, V.N.; Mai, P.D.; Man, P.K.; Nhu, D.T.; et al. The Medicinal Plants and Animals in Vietnam; Hanoi Science and Technology Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2004; Volume 1, pp. 612–613. [Google Scholar]

- Small, E. North American Cornucopia: Top 100 Indigenous Food Plants; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 669. [Google Scholar]

- Panthari, P.; Kharkwal, H.; Kharkwal, H.; Joshi, D.D. Myrica nagi: A review on active constituents, biological and therapeutic effects. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 4, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Rana, A.C. Pharmacognostic and pharmacological profile of traditional medicinal plant: Myrica nagi. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2012, 3, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Vimala, G.; Shoba, F.G. A review on antiulcer activity of few Indian medicinal plants. Int. J. Microbiol. 2014, 2014, 519590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tene, M.; Tane, P.; Connolly, J.D. Triterpenoids and diarylheptanoids from Myrica arborea. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2009, 36, 872–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Paetz, C.; Schneider, B. C-Methylated flavanones and dihydrochalcones from Myrica gale seeds. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2011, 39, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; She, G. Naturally occurring diarylheptanoids. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1687–1708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lv, H.; She, G. Naturally occurring diarylheptanoids—A supplementary version. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2012, 6, 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, Y.-C.; Ko, H.-H.; Wang, H.-C.; Peng, C.-F.; Chang, H.-S.; Hsieh, P.-C.; Chen, I.-S. Biological evaluation of secondary metabolites from the roots of Myrica adenophora. Phytochemistry 2014, 103, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, B.S.; Pelletier, S.W.; Newton, M.G.; Lee, D.; McGaughey, G.B.; Puar, M.S. Extensive 1D, 2D NMR spectra of some [7.0]metacyclophanes and X-ray analysis of (2)-myricanol. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, M.; Sakurai, N.; Yumoto, N.; Nagumo, S.; Seo, S. Oleanane acid from Myrica cerifera. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 1427–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, M.; Dohi, J.; Morihara, M.; Sakurai, N. Diarylheptanoids from Myrica gale var tomentosa and revised structure of porson. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1995, 43, 1674–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, H.; Fujita, Y.; Banno, N.; Watanabe, K.; Kimura, Y.; Manosroi, A.; Manosroi, J.; Akihisa, T. Three new cyclic diarylheptanoids and other phenolic compounds from the bark of Myrica rubra and their melanogenesis inhibitory and radical scavenging activities. J. Oleo. Sci. 2010, 59, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Dong, S.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Zhong, H.; Duc, G.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Y. Cyclic diarylheptanoids from Myrica nana inhibiting nitric oxide release. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 8510–8515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morihara, M.; Sakurai, N.; Inoue, T.; Kawai, K.-I.; Nagai, M. Two novel diarylheptanoid glucosides from Myrica gale var. tormentosa and absolute structure of plane-chiral galeon. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1997, 45, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.R.; Lebar, M.D.; Jinwal, U.K.; Abisambra, J.F.; Koren, J., III; Blair, L.; O’Leary, J.C.; Davey, Z.; Trotter, J.; Johnson, A.G.; et al. The diarylheptanoid (+)-aR,11S-myricanol and two flavones from bayberry (Myrica cerifera) destabilize the microtubule-associated protein Tau. J. Nat. Prod. 2011, 74, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhiem, N.X.; van Kiem, P.; van Minh, C.; Tai, B.H.; Cuong, N.X.; Thu, V.K.; Anh, H.L.T.; Jo, S.-H.; Jang, H.-D.; Kwon, Y.-I.; et al. A new monoterpenoid glycoside from Myrica esculenta and the inhibition of angiotensin I-converting enzyme. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 58, 1408–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Oh, M.H.; Park, K.J.; Heo, J.H.; Lee, M.W. Anti-inflammatory activity of sulfate-containing phenolic compounds isolated from the leaves of Myrica rubra. Fitoterapia 2014, 92, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, M.H.; Oh, M.H.; Kim, S.R.; Park, K.J.; Lee, M.W. Flavonoid constituents in the leaves of Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc. with anti-inflammatory activity. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2013, 36, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-L.; Kong, L.-C.; Yin, C.-P.; Jiang, D.-H.; Jiang, J.-Q.; He, J.; Xiao, W.-X. Extraction optimization by response surface methodology, purification and principal antioxidant metabolites of red pigments extracted from bayberry (Myrica rubra) pomace. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 51, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.C.; Waterman, P.G. Condensed tannins from Myrica gale. Fitoterapia 2000, 71, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Morikawa, T.; Toguchida, I.; Ando, S.; Matsuda, H.; Yoshikawa, M. Inhibitors of nitric oxide production from the bark of Myrica rubra: Structures of new biphenyl type diarylheptanoid glycosides and taraxerane type triterpene. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2002, 10, 4005–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamola, A.; Semwal, D.K.; Semwal, S.; Rawat, U. Flavonoid glycosides from Myrica esculenta leaves. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 535–536. [Google Scholar]

- Anthonsen, T.; Lorentzen, G.B.; Malterud, K.E. Porson, a new [7,0]-metacyclophane from Myrica gale L. Acta Chem. Scand. Ser. B 1975, 29, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházková, D.; Boušová, I.; Wilhelmová, N. Antioxidant and prooxidant properties of flavonoids. Fitoterapia 2011, 82, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafini, M.; Peluso, I.; Raguzzini, A. Flavonoids as anti-inflammatory agents. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Immunonutrition Workshop, Platja D’Aro, Girona, Spain, 21–24 October 2009; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; 69, pp. 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- Jatczak, K.; Grynkiewicz, G. Triterpene sapogenins with oleanene skeleton: Chemotypes and biological activities. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2014, 61, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vechia, D.; Gnoatto, L.; Simone, C.B.; Gosmann, G. Oleanane and ursane derivatives and their importance on the discovery of potential antitumour, antiinflammatory and antioxidant drugs. Quím. Nova. 2009, 32, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.N.; Bristi, N.J.; Rafiquzzaman, M. Review on in vivo and in vitro methods evaluation of antioxidant activity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2013, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubió, L.; Motilva, M.J.; Romero, M.-P. Recent advances in biologically active compounds in herbs and spices: A review of the most effective antioxidant and anti-inflammatory active principles. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.B.L.; Lim, Y.Y. Critical analysis of current methods for assessing the in vitro antioxidant and antibacterial activity of plant extracts. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Feng, L.; Shen, Y.; Su, H.; Li, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, X. Myricitrin inhibits acrylamide-mediated cytotoxicity in human Caco-2 cells by preventing oxidative stress. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Xuan, Z.-H.; Tiana, S.; He, G.-R.; Du, G.-H. Myricitrin attenuates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced mitochondrial damage and apoptosis in PC12 cells via inhibition of mitochondrial oxidation. J. Funct. Food 2013, 5, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padayatty, S.J.; Katz, A.; Wang, Y.; Eck, P.; Kwon, O.; Lee, J.-H.; Chen, S.; Corpe, C.; Dutta, A.; Dutta, S.K.; Levine, M. Vitamin C as an antioxidant: Evaluation of its role in disease prevention. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2003, 22, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spínola, V.; Llorent-Martínez, E.J.; Gouveia, S.; Castilho, P.C. Myrica faya: A new source of antioxidant phytochemicals. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 9722–9735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Qiao, L.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, Y.; Ye, X. Structural elucidation and antioxidant activities of proanthocyanidins from Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) leaves. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurieva, R.I.; Chung, Y. Understanding the development and function of T follicular helper cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2010, 7, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesha, S.H.; Dudics, S.; Acharya, B.; Moudgil, K.D. Cytokine-modulating strategies and newer cytokine targets for arthritis therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 887–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktan, F. iNOS-mediated nitric oxide production and its regulation. Life Sci. 2004, 75, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treuer, A.V.; Gonzalez, D.R. Nitric oxide synthases, S-nitrosylation and cardiovascular health: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 1555–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinski, P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, B.J.C.; Seca, A.M.L.; Barreto, M.D.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A. Recent Breakthroughs in the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Morella and Myrica Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 17160-17180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160817160

Silva BJC, Seca AML, Barreto MDC, Pinto DCGA. Recent Breakthroughs in the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Morella and Myrica Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015; 16(8):17160-17180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160817160

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Bruno J. C., Ana M. L. Seca, Maria Do Carmo Barreto, and Diana C. G. A. Pinto. 2015. "Recent Breakthroughs in the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Morella and Myrica Species" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16, no. 8: 17160-17180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160817160

APA StyleSilva, B. J. C., Seca, A. M. L., Barreto, M. D. C., & Pinto, D. C. G. A. (2015). Recent Breakthroughs in the Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Morella and Myrica Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 16(8), 17160-17180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160817160