Enzymatic Tenderization of Garden Snail Meat (Cornu aspersum aspersum) Using Plant Cysteine Proteases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Texture Analysis Results

2.2. Sensory Evaluation of Enzymatically Tenderized Garden Snail Meat

2.2.1. Papain Treatments

2.2.2. Bromelain Treatments

2.2.3. Ginger Extract Treatments

2.2.4. Overall Interpretation

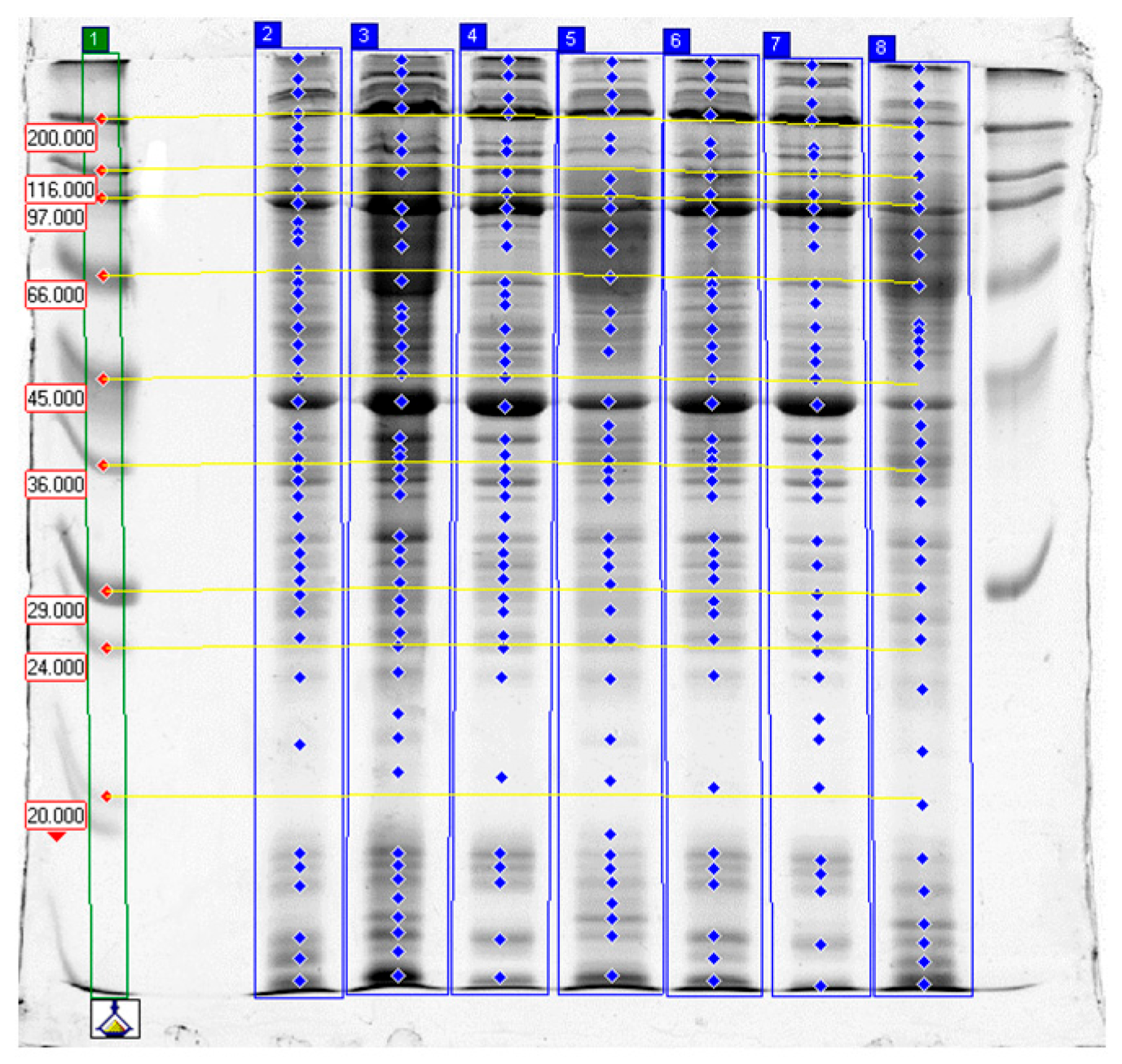

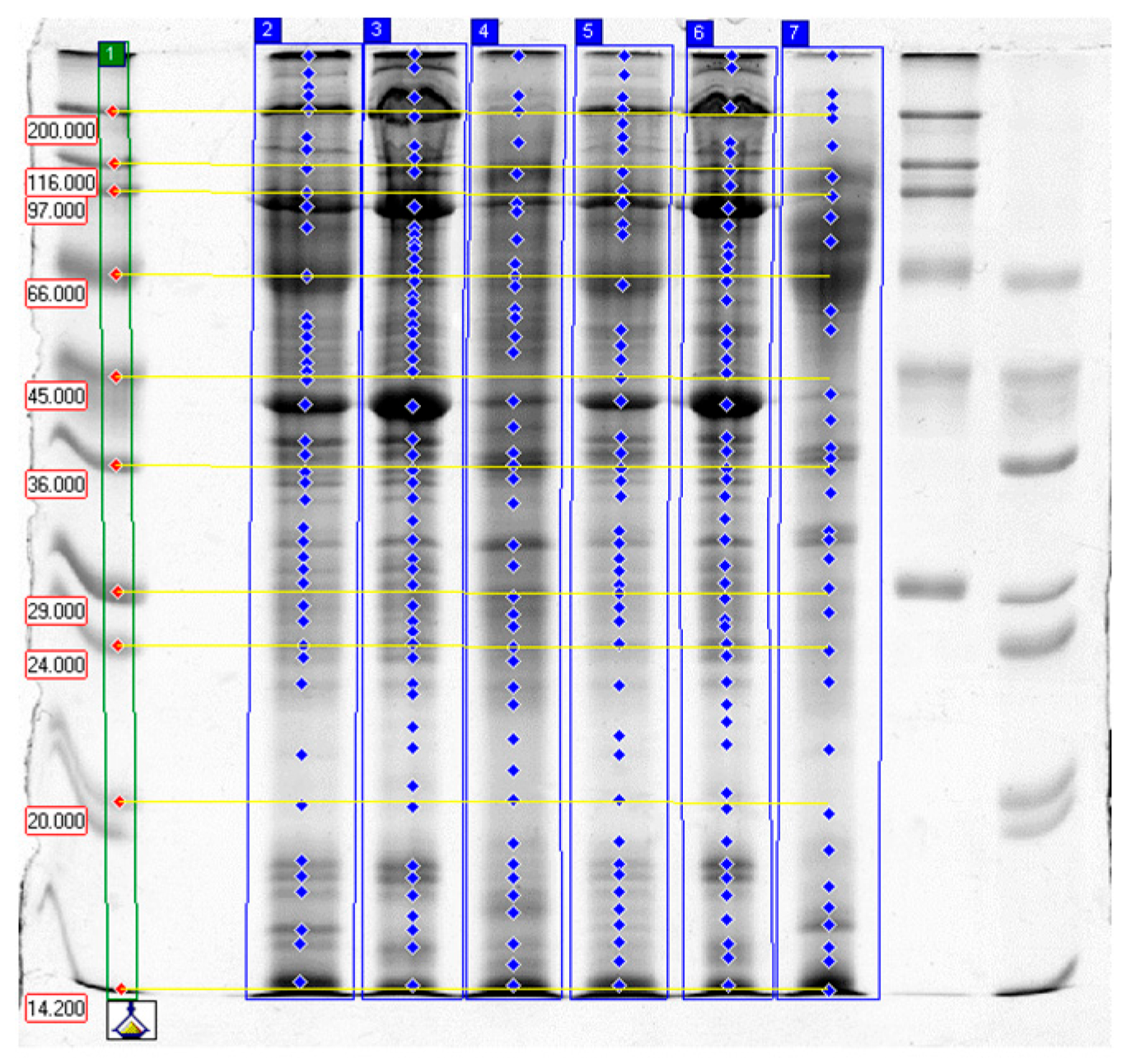

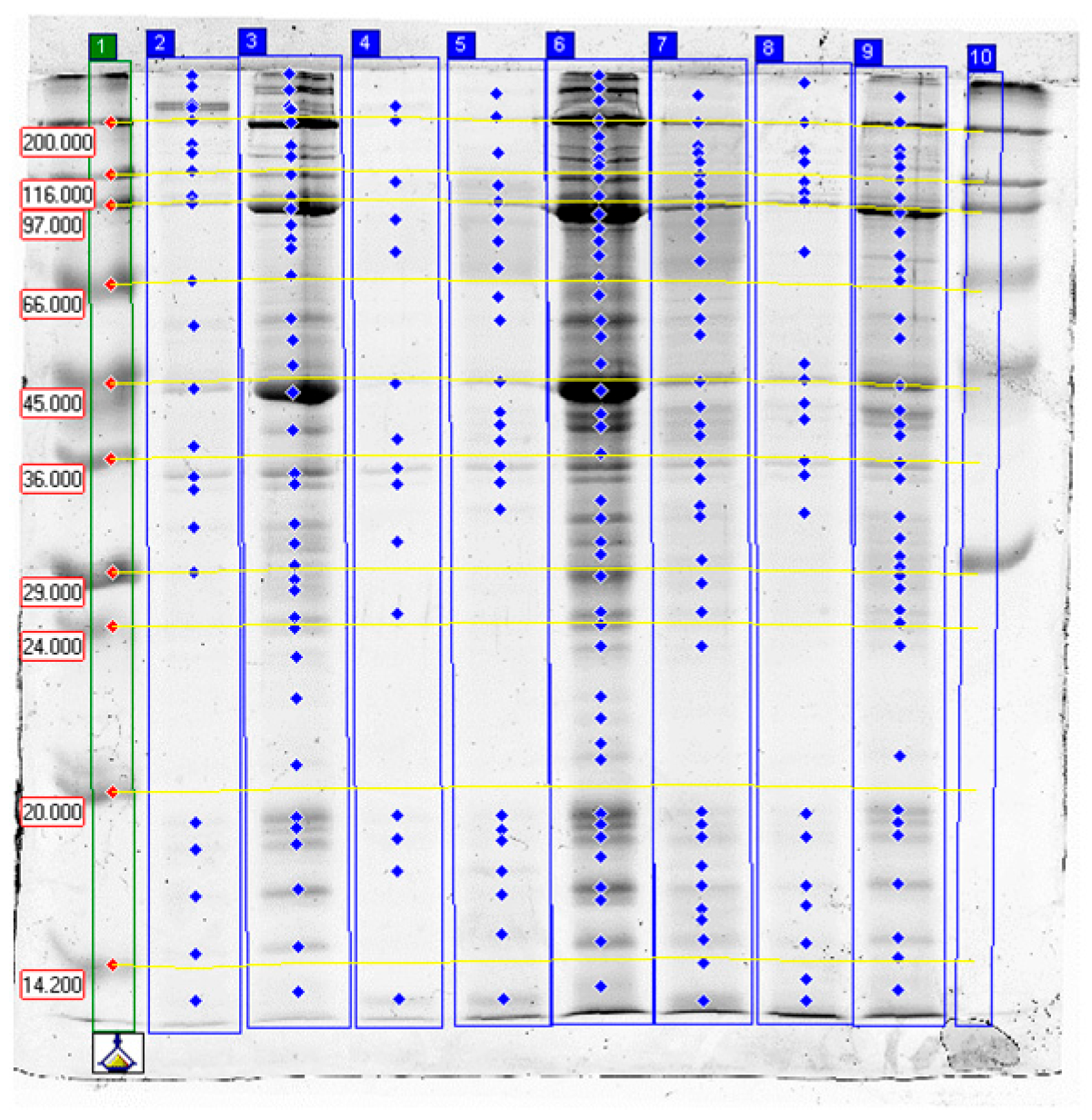

2.3. SDS-PAGE Electrophoresis Results

2.3.1. Effects of Papain

2.3.2. Effects of Bromelain

2.3.3. Effects of Ginger Extract

2.3.4. Effect of Tissue Type

2.3.5. Summary and Practical Implications

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Raw Material

3.2. Enzyme Preparations

3.3. Sample Treatment

3.4. Control Treatments

3.5. Texture Analysis

3.6. Sensory Evaluation

3.7. SDS-PAGE Electrophoresis

3.8. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yildirim, F.K.; Ulusoy, B.H.; Erdogmus, S.Z.; Hecer, C. A Survey Study on Parasite Presence of Edible Wild Terrestrial Snails (Helix pomatia L.) in Northern Cyprus. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 6, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garkov, M.; Nikovska, K. Health and Sustainability: The Nutritional Value of Snail Meat. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 16, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rygało-Galewska, A.; Zglińska, K.; Niemiec, T. Edible Snail Production in Europe. Animals 2022, 12, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligaszewski, M.; Surówka, K.; Szymczyk, B.; Pol, P.; Anthony, B. Effect of Boiling on Chemical Composition of Small Brown Snail (Cornu aspersum aspersum) Meat. Ann. Anim. Sci. 2024, 24, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağıltay, F.; Erkan, N.; Tosun, D.; Selçuk, A. Amino Acid, Fatty Acid, Vitamin and Mineral Contents of the Edible Garden Snail (Helix aspersa). J. Fish. 2011, 5, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogas, A.; Laliotis, G.; Ladoukakis, E.; Trachana, V. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Profile of Snails (Cornu aspersum aspersum) Fed Diets with Different Protein Sources under Intensive Rearing Conditions. J. Anim. Feed Sci. 2021, 30, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo Tovar, N.; Tamayo Galván, V.E.; Pérez Ruiz, R.V.; García Garibay, M.; Aguilar Toalá, J.E.; Rosas Espejel, M.; Arce Vazquez, M.B. Evaluation of Protein Sources in Snail (Helix aspersa Múller) Diets on the Antioxidant Bioactivity of Peptides in Meat and Slime. Agro Product. 2024, 12, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligaszewski, M.; Pol, P. Preliminary Study on the Production Quality of Edible Snail Cornu aspersum aspersum (Synonym Helix aspersa aspersa) Receiving a Feed Mix Supplemented with Betaine Hydrochloride (Trimethylglycine). Wiad. Zootech. 2018, 56, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Pomary, D.; Korkor, B.S.; Asimeng, B.O.; Katu, S.K.; Paemka, L.; Apalangya, V.A.; Mensah, B.; Foster, E.J.; Tiburu, E.K. Collagen Derived from a Giant African Snail (Achatina achatina) for Biomedical Applications. J. Polym. Sci. Eng. 2024, 7, 4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarai, Z.; Balti, R.; Mejdoub, H.; Gargouri, Y.; Sayari, A. Process for Extracting Gelatin from Marine Snail (Hexaplex trunculus): Chemical Composition and Functional Properties. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kougiagka, E.; Apostologamvrou, C.; Hatziioannou, M.; Giannouli, P. Quality Characteristics and Microstructure of Boiled Snail Fillet Meat. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e17079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Azmi, S.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, N.; Sazili, A.; Lee, S.-J.; Ismail-Fitry, M. Application of Plant Proteases in Meat Tenderization: Recent Trends and Future Prospects. Foods 2023, 12, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekhit, A.A.; Hopkins, D.L.; Geesink, G.; Bekhit, A.A.; Franks, P. Exogenous Proteases for Meat Tenderization. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1012–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril, B.; Bou, R.; García-Pérez, J.V.; Benedito, J. Role of Enzymatic Reactions in Meat Processing and Use of Emerging Technologies for Process Intensification. Foods 2023, 12, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, C.O.; Kocatepe, D.; Çorapcı, B.; Köstekli, B.; Turan, H. A Comprehensive Investigation of Tenderization Methods: Evaluating the Efficacy of Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Methods in Improving the Texture of Squid Mantle—A Detailed Comparative Study. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 3999–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Wu, B.; Fu, B.; Jiang, P.; Liu, Y.; Qi, L.; Du, M.; Dong, X. Enzyme Treatment-Induced Tenderization of Puffer Fish Meat and Its Relation to Physicochemical Changes of Myofibril Protein. LWT 2022, 155, 112891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P. Marine Enzymes and Food Industry: Insight on Existing and Potential Interactions. Front. Mar. Sci. 2014, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woinue, Y.; Ayele, A.; Hailu, M.; Chaurasiya, R.S. Comparison of Different Meat Tenderization Methods: A Review. Food Res. 2019, 4, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusankha, G.D.M.P.; Thilakarathna, R.C.N. Meat Tenderization Mechanism and the Impact of Plant Exogenous Proteases: A Review. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Bekhit, A.E.-D.A.; Carne, A.; Hopkins, D.L. Characterisation of Commercial Papain, Bromelain, Actinidin and Zingibain Protease Preparations and Their Activities toward Meat Proteins. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Iyengar, D.; Mukhopadhyay, K. Emergence of Snail Mucus as a Multifunctional Biogenic Material for Biomedical Applications. Acta Biomater. 2025, 200, 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, R.; Miller, R.; Ha, M.; Wheeler, T.L.; Dunshea, F.; Li, X.; Vaskoska, R.S.; Purslow, P. Meat Tenderness: Underlying Mechanisms, Instrumental Measurement, and Sensory Assessment. Meat Muscle Biol. 2021, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakun, J.; Sencio, M. The Estimation Scale of the Meat Tendinous-Tenderness Indicator Using Warner-Bratzler Test. In Proceedings of the 6th International CIGR Technical Symposium-Towards a Sustainable Food Chain: Food Process, Bioprocessing and Food Quality Management, Nantes, France, 18–20 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Diakun, J.; Dolik, K.; Sencio, M.; Tomkiewicz, D. Ocena Tekstury Mięsa z Wykorzystaniem Środowiska Matlab. Politech. Koszal. 2012, 58, 480–483. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura, T. The Role of Intramuscular Connective Tissue in Meat Texture. Anim. Sci. J. 2010, 81, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyukyavuz, A. Effect of Bromelain on Duck Breast Meat Tenderization. Ph.D. Thesis, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C.K.; Rice, E.E. Degradation of various meat fractions by tenderizing enzymes. J. Food Sci. 1970, 35, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökoglu, N.; Yerlikaya, P.; Ucak, I.; Yatmaz, H.A. Effect of Bromelain and Papain Enzymes Addition on Physicochemical and Textural Properties of Squid (Loligo vulgaris). J. Food Meas. Charact. 2017, 11, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkins, C.R.; Sullivan, G. Adding Enzymes to Improve Beef Tenderness. In Beef Facts Product Enhancement; National Cattleman’s Beef Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Maqsood, S.; Manheem, K.; Gani, A.; Abushelaibi, A. Degradation of Myofibrillar, Sarcoplasmic and Connective Tissue Proteins by Plant Proteolytic Enzymes and Their Impact on Camel Meat Tenderness. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3427–3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Lai, S.; Yang, H. Effects of Bromelain Tenderisation on Myofibrillar Proteins, Texture and Flavour of Fish Balls Prepared from Golden Pomfret. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 1918–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.A.; Sarangi, P.K.; Singh, N.J. Tenderisation of Meat by Bromelain Enzyme Extracted from Pineapple Wastes. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 3256–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketnawa, S.; Rawdkuen, S. Application of Bromelain Extract for Muscle Foods Tenderization. Food Nutr. Sci. 2011, 02, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendo, J.A.; Beltrán, J.A.; Roncalés, P. Tenderization of Squid (Loligo vulgaris and Illex coindetii) with Bromelain and a Bovine Spleen Lysosomal-Enriched Extract. Food Res. Int. 1997, 30, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaozhen, T.; Huang, X.; Wang, M.; Ma, M.; Li, K. Comparison of Effects of Zingibain and Ginger Juice on Tenderization Od Pork. J. Shandong Agric. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2003, 34, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Abdeldaiem, M.H.; Hoda, G.M.A. Tenderization of Camel Meat by Using Fresh Ginger (Zingiber officinale) Extract. Food Sci. Qual. Manag. 2013, 21, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Istrati, D. The Influence of Enzymatic Tenderization with Papain on Functional Properties of Adult Beef. J. Agroaliment. Process. Technol. 2008, 14, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- Saengsuk, N.; Laohakunjit, N.; Sanporkha, P.; Kaisangsri, N.; Selamassakul, O.; Ratanakhanokchai, K.; Uthairatanakij, A. Physicochemical Characteristics and Textural Parameters of Restructured Pork Steaks Hydrolysed with Bromelain. Food Chem. 2021, 361, 130079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveena, B.M.; Mendiratta, S.K. Tenderisation of Spent Hen Meat Using Ginger Extract. Br. Poult. Sci. 2001, 42, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracchi, P.I.G. Differentiation between Helix and Achatina Snail Meat by Gel Electrophoresis. J. Food Sci. 1988, 53, 652–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayment, I.; Holden, H.M. Myosin Subfragment-1: Structure and Function of a Molecular Motor. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1993, 3, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Grutta, S.; Calvani, M.; Bergamini, M.; Pucci, N.; Asero, R. Allergia Alla Tropomiosina: Dalla Diagnosi Molecolare Alla Pratica Clinica. Riv. Immunol. E Allergol. Pediatr. 2011, 2, 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, C.; Szent-Györgyi, A.G.; Kendrick-Jones, J. Paramyosin and the Filaments of Molluscan “Catch” Muscles. J. Mol. Biol. 1971, 56, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, X.; Pan, Y.; Shu, M.; Geng, J.; Wu, G.; Zhong, C. Paramyosin from Field Snail (Bellamya quadrata): Structural Characteristics and Its Contribution to Enhanced the Gel Properties of Myofibrillar Protein. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, W.O.; Ozaki, M.M.; Dos Santos, M.; De Castro, R.J.S.; Sato, H.H.; Câmara, A.K.F.I.; Rodríguez, A.P.; Campagnol, P.C.B.; Pollonio, M.A.R. Evaluating Different Levels of Papain as Texture Modifying Agent in Bovine Meat Loaf Containing Transglutaminase. Meat Sci. 2023, 198, 109112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Huang, F. Exploring How Papaya Juice Improves Meat Tenderness and Digestive Characteristics in Wenchang Chickens. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarkan, M.; Maquoi, E.; Delbrassine, F.; Herman, R.; M’Rabet, N.; Calvo Esposito, R.; Charlier, P.; Kerff, F. Structures of the Free and Inhibitors-Bound Forms of Bromelain and Ananain from Ananas Comosus Stem and in Vitro Study of Their Cytotoxicity. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Hamilton, S.E.; Guddat, L.W.; Overall, C.M. Plant Collagenase: Unique Collagenolytic Activity of Cysteine Proteases from Ginger. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Gen. Subj. 2007, 1770, 1627–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.S. Effect of Proteolytic Enzymes and Ginger Extract on Tenderization of M. pectoralis profundus from Holstein Steer. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, W.; Li, X.; Qi, D.; Chen, H.; Liu, H.; Yu, S.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y. Evaluating the Properties of Ginger Protease-Degraded Collagen Hydrolysate and Identifying the Cleavage Site of Ginger Protease by Using an Integrated Strategy and LC-MS Technology. Molecules 2022, 27, 5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, Z.B.; Thomson, P.C.; Campbell, M.A.; Latif, S.; Legako, J.F.; McGill, D.M.; Wynn, P.C.; Friend, M.A.; Warner, R.D. Sensory and Physical Characteristics of M. biceps femoris from Older Cows Using Ginger Powder (Zingibain) and Sous Vide Cooking. Foods 2021, 10, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-J.; Taub, I.A. Specific Degradation of Myosin in Meat by Bromelain. Food Chem. 1991, 40, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, T.L.; Shackelford, S.D.; Koohmaraie, M. Sampling, Cooking, and Coring Effects on Warner-Bratzler Shear Force Values in Beef. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8586:2012; Sensory Analysis—General Guidelines for the Selection, Training and Monitoring of Selected Assessors and Expert Sensory Assessors. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Percie Du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples Without 1 h Hydrothermal Treatment | Samples with 1 h Hydrothermal Treatment (HT) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 [N] | S2 [N] | S1 [N] | S2 [N] | ||

| blind test * | for ginger extract | 28.2 ± 1.6 a | 25.2 ± 1.9 a | 21.4 ± 0.7 a | 20.9 ± 1.0 a |

| for papain and bromelain | 30.3 ± 3.3 a | 24.3 ± 2.3 a | 22.7 ± 4.3 a | 21.8 ± 3.6 a | |

| papain 0.05% | 24.8 ± 1.3 b | 20.1 ± 2.2 a | 18.3 ± 0.8 ab | 17.4 ± 0.3 b | |

| papain 0.1% | 22.9 ± 1.2 b | 17.2 ± 0.5 b | 18.0 ± 0.9 ab | 15.1 ± 1.1 c | |

| bromelain 0.05% | 18.2 ± 3.3 bc | 15.0 ± 4.7 bc | 17.6 ± 3.2 b | 15.4 ± 3.8 bc | |

| bromelain 0.1% | 14.2 ± 3.3 c | 12.7 ± 2.7 bc | 14.1 ± 3.7 b | 14.1 ± 3.6 bc | |

| ginger extract 10% | 26.0 ± 1.6 ab | 20.0 ± 2.1 ab | 19.0 ± 1.9 ab | 18.9 ± 1.7 b | |

| Appearance | Colour | Aroma | Taste | Texture | Final Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight factor | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.30 | ||

| Blind test | average rating | 4.3 ± 0.6 a | 3.8 ± 0.6 a | 4.3 ± 0.5 a | 3.7 ± 0.6 b | 3.7 ± 0.6 ab | |

| score | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 3.9 ± 0.3 ab | |

| Papain 0.05% | average rating | 4.1 ± 0.6 a | 3.9 ± 0.6 a | 4.6 ± 0.5 a | 4.0 ± 0.8 ab | 4.3 ± 0.6 ab | |

| score | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 4.2 ± 0.4 a | |

| Papain 0.1% | average rating | 2.2 ± 0.4 b | 3.5 ± 0.6 a | 4.0 ± 0.7 a | 4.1 ± 0.7 ab | 3.1 ± 0.6 b | |

| score | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 3.3 ± 0.4 b | |

| Bromelain 0.05% | average rating | 3.9 ± 0.5 a | 3.6 ± 0.6 a | 4.3 ± 0.5 a | 4.5 ± 0.6 ab | 4.3 ± 0.5 ab | |

| score | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 4.1 ± 0.3 a | |

| Bromelain 0.1% | disqualifying visual assessment | ||||||

| Ginger extract 10% | average rating | 4.2 ± 0.4 a | 4.5 ± 0.5 a | 4.8 ± 0.4 a | 4.8 ± 0.4 a | 4.9 ± 0.4 a | |

| score | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 4.6 ± 0.2 a | |

| Ginger extract 25% | disqualifying visual assessment | ||||||

| Enzyme | Concentration | Texture Improvement | Appearance Impact | Aroma/Flavor Change | Final Score | Risk of Over-Tenderization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (Blind test) | — | — | — | — | 3.9 | None |

| Papain | 0.05% | High—texture ↑ (1.3) | Moderate decline | Neutral | 4.2 | Moderate |

| Papain | 0.1% | Moderate (1.0) | Noticeable decline | Neutral | 3.3 | High—over-tenderized |

| Bromelain | 0.05% | High—texture ↑ (1.3) | Moderate decline | Slight aroma ↑ | 4.1 | Mild |

| Bromelain | 0.1% | — | Disqualified (visual degradation) | — | — | Very high |

| Ginger extract | 10% | Highest—texture ↑ (1.4) | Minimal impact | None/pleasant | 4.6 | Not observed |

| Ginger extract | 25% | — | Disqualified (visual degradation) | — | — | Very high |

| Papain | Bromelain | Ginger Extract | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Fraction (kDa) | “0” | BUFFER | 0.05% | 0.10% | 0.05% | 0.10% | 10% | 25% |

| Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | |

| >200 | 18.64 | 18.16 | 16.06 | 14.17 | 3.33 | 7.09 | 4.46 | 13.3 |

| 121–200 | 2.98 | 3.97 | 3.97 | 7.04 | 7.43 | 5.09 | 1.17 | 3.59 |

| 90–120 | 11.56 | 16.13 | 12.92 | 15.52 | 1.96 | 1.65 | 22.67 | 20.34 |

| 68–89 | 2.2 | 3.08 | 6.99 | 9.66 | 9.06 | 4.2 | 30.04 | 2.02 |

| 50–67 | 5.74 | 6.86 | 10.83 | 18.5 | 4.84 | 25.35 | 1.66 | 0 |

| 30–49 | 21.31 | 24.77 | 15.6 | 16.32 | 19.16 | 12.57 | 16.55 | 30.29 |

| 19–29 | 6.43 | 6.88 | 8 | 6 | 12.94 | 7.24 | 2.92 | 4.08 |

| <19 | 31.14 | 20.17 | 25.66 | 12.77 | 41.28 | 36.81 | 20.55 | 26.36 |

| Papain | Bromelain | Ginger Extract | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Fraction (kDa) | “0” | BUFFER | 0.05% | 0.10% | 0.05% | 0.10% | 10% | 25% |

| Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | Band % | |

| >200 | 23.07 | 19.56 | 24.53 | 22.12 | 8.55 | 8.54 | 19.74 | 8.89 |

| 121–200 | 4.22 | 3.25 | 5.04 | 5.26 | 4.53 | 1.9 | 5.91 | 2.9 |

| 90–120 | 16.03 | 16.36 | 14.45 | 16.84 | 15.58 | 10.1 | 17.11 | 21.56 |

| 68–89 | 1.39 | 2.33 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 2.02 | 2.7 | 3.01 | 2.96 |

| 50–67 | 6.85 | 7.19 | 4.4 | 4.08 | 12.18 | 19.04 | 5.23 | 2.37 |

| 30–49 | 25.39 | 29.54 | 21.06 | 20.3 | 20.05 | 24.61 | 24.3 | 32.03 |

| 19–29 | 6.26 | 5.93 | 7.14 | 8.53 | 8.42 | 10.77 | 12.01 | 15.47 |

| <19 | 16.8 | 15.86 | 18.63 | 18.36 | 28.7 | 22.36 | 12.71 | 13.82 |

| Enzyme | Blind Test | 1st Concentration Variant [%] | 2nd Concentration Variant [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Papain | Citrate buffer solution (pH 6.0) | 0.05 | 0.1 |

| Bromelain | 0.05 | 0.1 | |

| Ginger extract | water | 10 | 25 |

| A Qualitative Feature | Weight Factor | Score Point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Appearance | 0.20 | Smooth, shiny surface, very well-preserved shape | Smooth surface, well-preserved shape | Matt surface, shape enabling recognition | Matte surface, poorly preserved shape | Completely not preserved shape, individual elements of the carcass visibly separated from each other |

| Colour | 0.15 | White or creamy | Creamy or yellow-cream | Beige | Grey or brown | Dark grey or dark brown |

| Aroma | 0.15 | Mild and characteristic | Very mild, poorly perceptible | Neutral | Indifferent, expressionless, with a perceptible mushroom/earthy smell | Intense fungal/earthy smell |

| Taste | 0.20 | Delicate, mild, specific taste | Mild, delicate, less palpable | Neutral, expressionless | Neutral, expressionless with a perceptible mushroom/earthy flavour | Intense fungal/earthy aftertaste |

| Texture | 0.30 | Soft and compact, flexible, allowing easy biting | Compact, slightly rubbery | Not very elastic, rubbery, hard, but it allows to bite | Rubbery, hard, difficult to chew | Very hard and rubbery, very difficult to chew/overly softened |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tesarowicz, I.; Ligaszewski, M.; Pol, P.; Surówka, K.; Szczepanik, M.; Widor, K.; Budz, K. Enzymatic Tenderization of Garden Snail Meat (Cornu aspersum aspersum) Using Plant Cysteine Proteases. Molecules 2026, 31, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030466

Tesarowicz I, Ligaszewski M, Pol P, Surówka K, Szczepanik M, Widor K, Budz K. Enzymatic Tenderization of Garden Snail Meat (Cornu aspersum aspersum) Using Plant Cysteine Proteases. Molecules. 2026; 31(3):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030466

Chicago/Turabian StyleTesarowicz, Iwona, Maciej Ligaszewski, Przemysław Pol, Krzysztof Surówka, Małgorzata Szczepanik, Katarzyna Widor, and Karolina Budz. 2026. "Enzymatic Tenderization of Garden Snail Meat (Cornu aspersum aspersum) Using Plant Cysteine Proteases" Molecules 31, no. 3: 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030466

APA StyleTesarowicz, I., Ligaszewski, M., Pol, P., Surówka, K., Szczepanik, M., Widor, K., & Budz, K. (2026). Enzymatic Tenderization of Garden Snail Meat (Cornu aspersum aspersum) Using Plant Cysteine Proteases. Molecules, 31(3), 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030466