Ozone-Oxidation of Glucose to Formic Acid over Polyoxmetalates

Abstract

1. Introduction

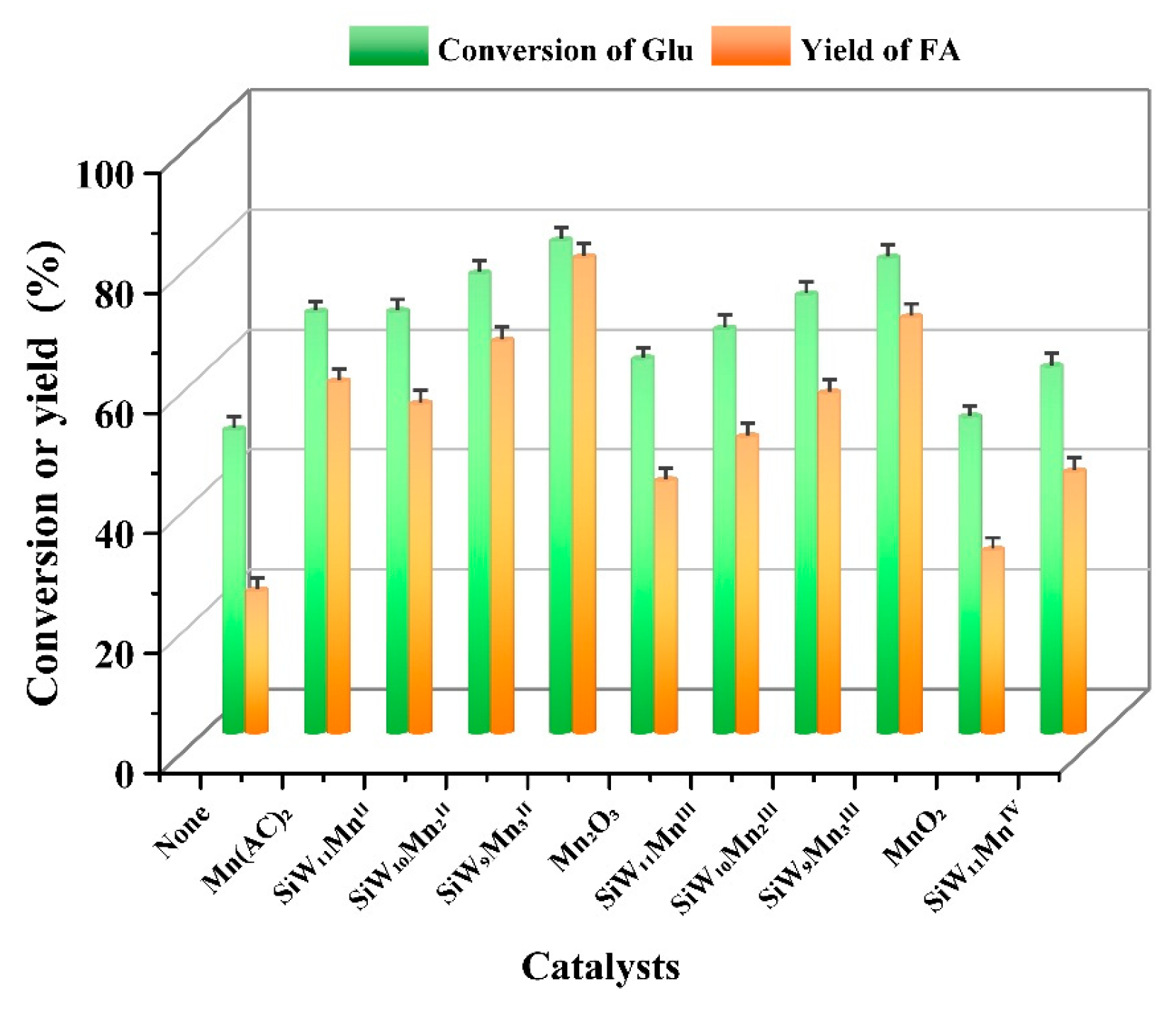

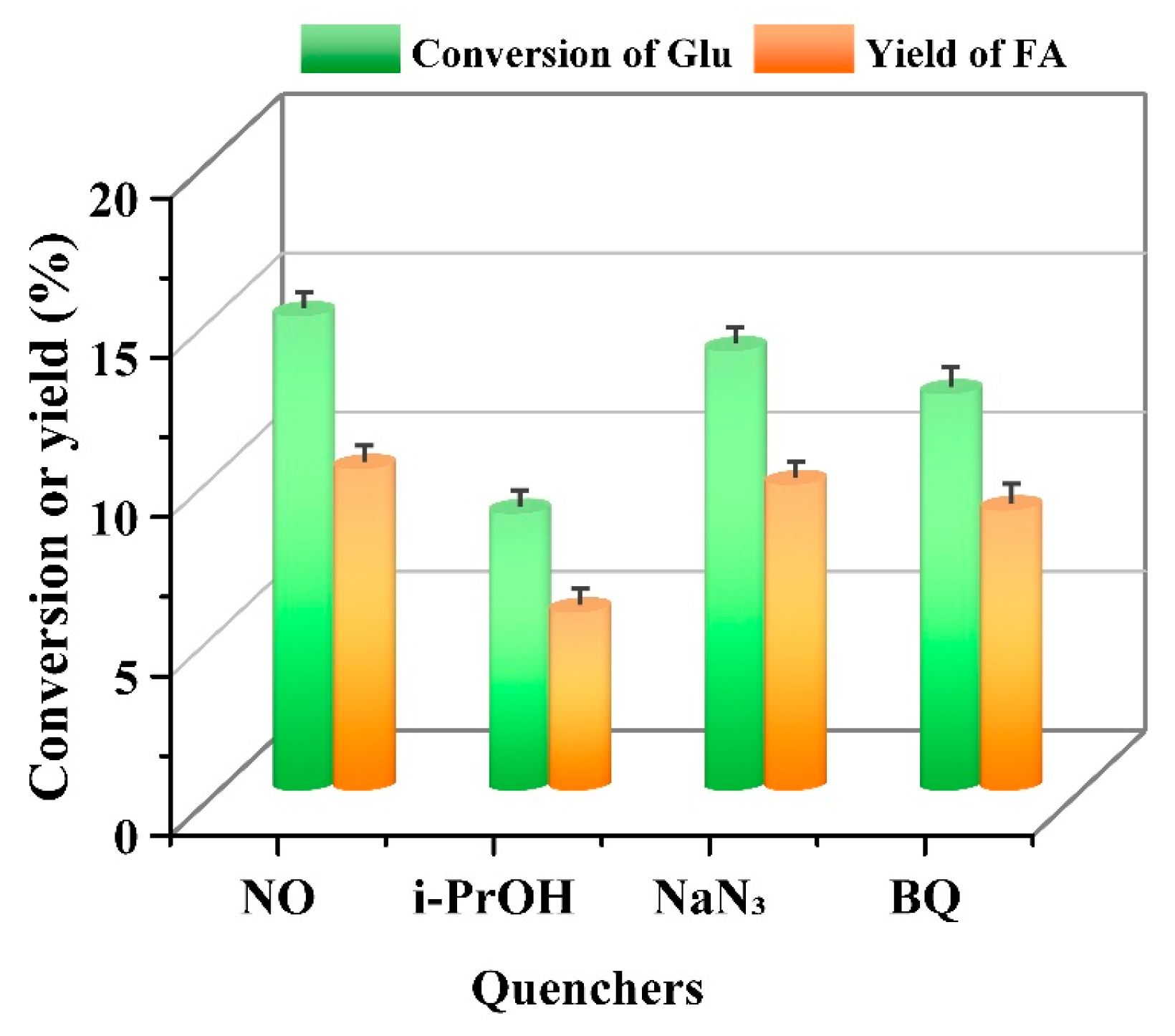

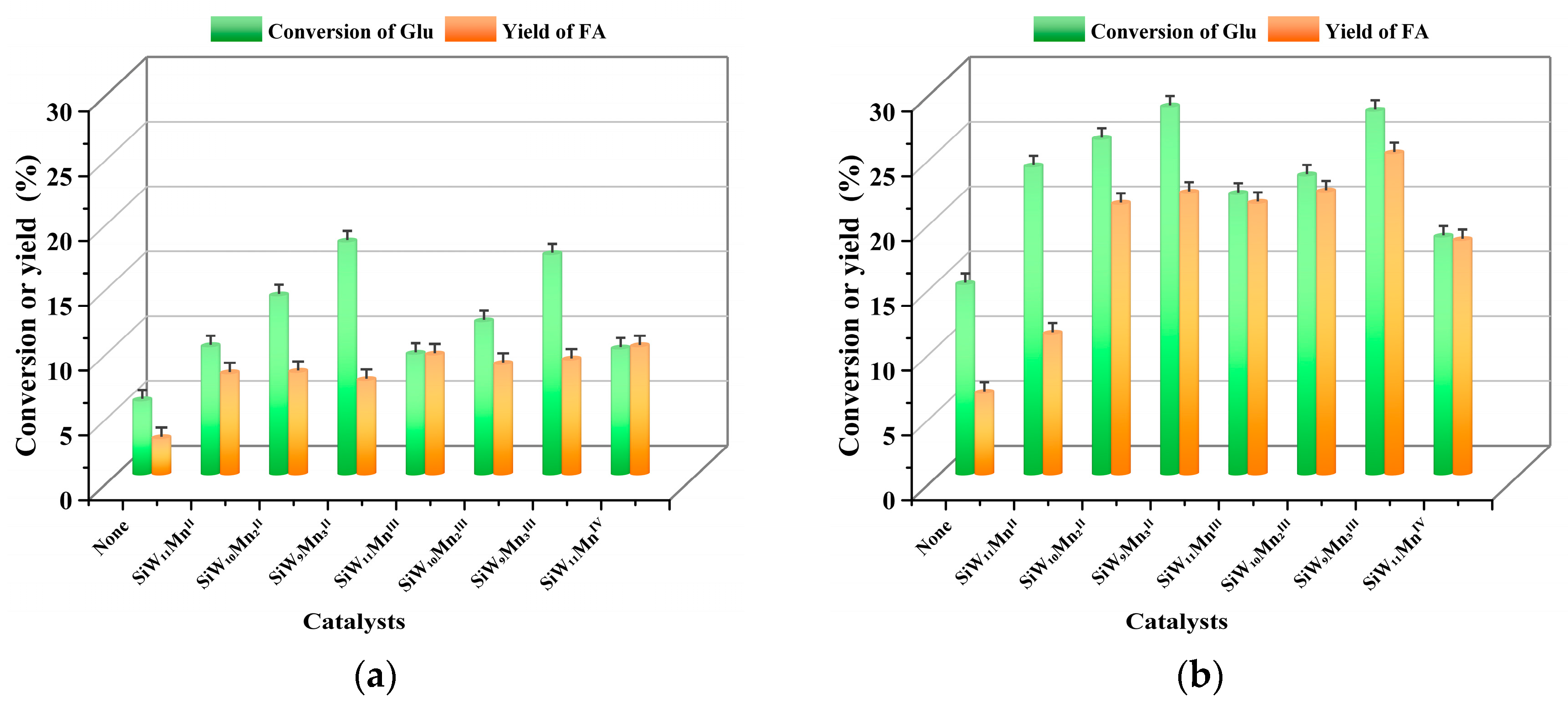

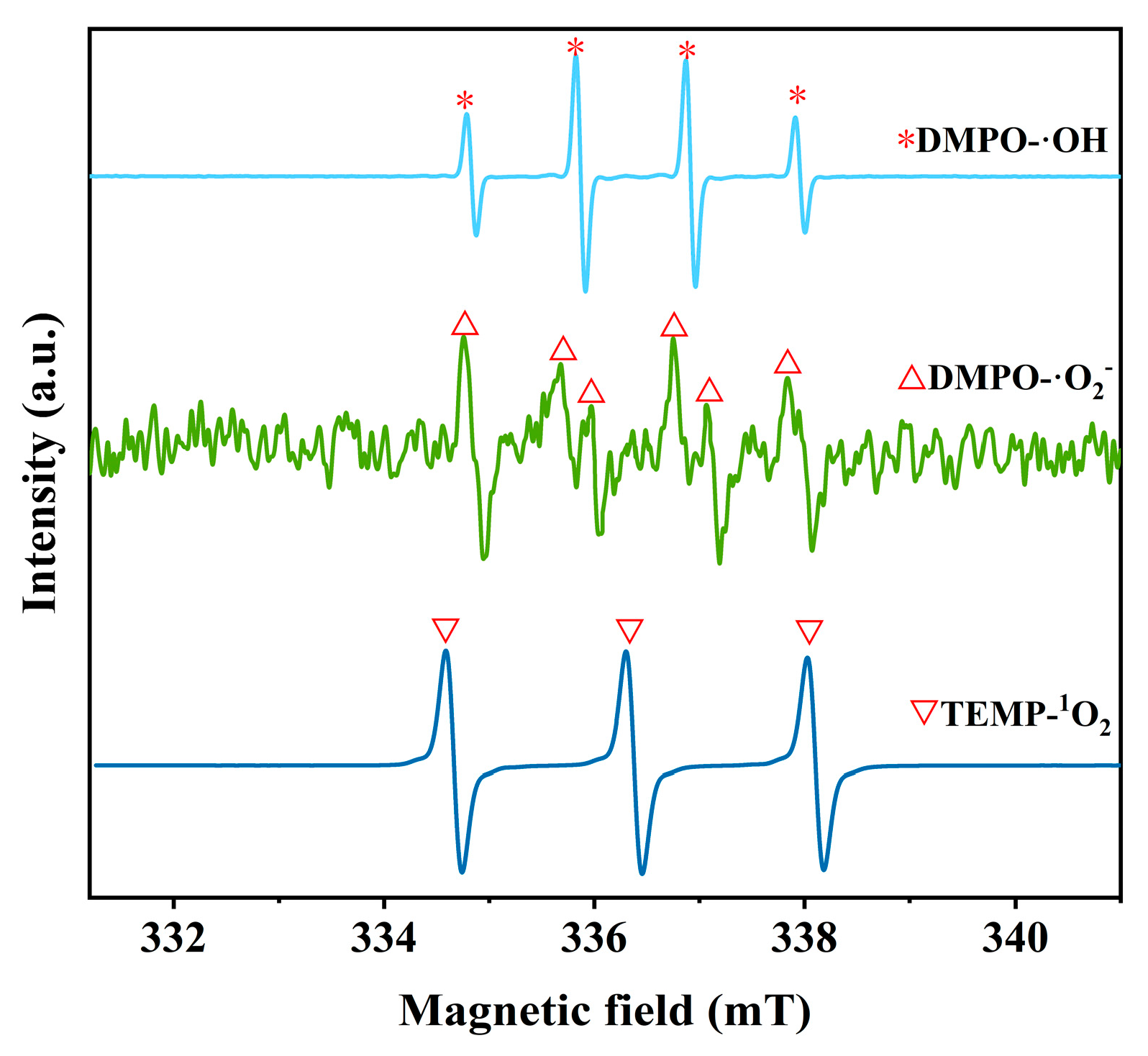

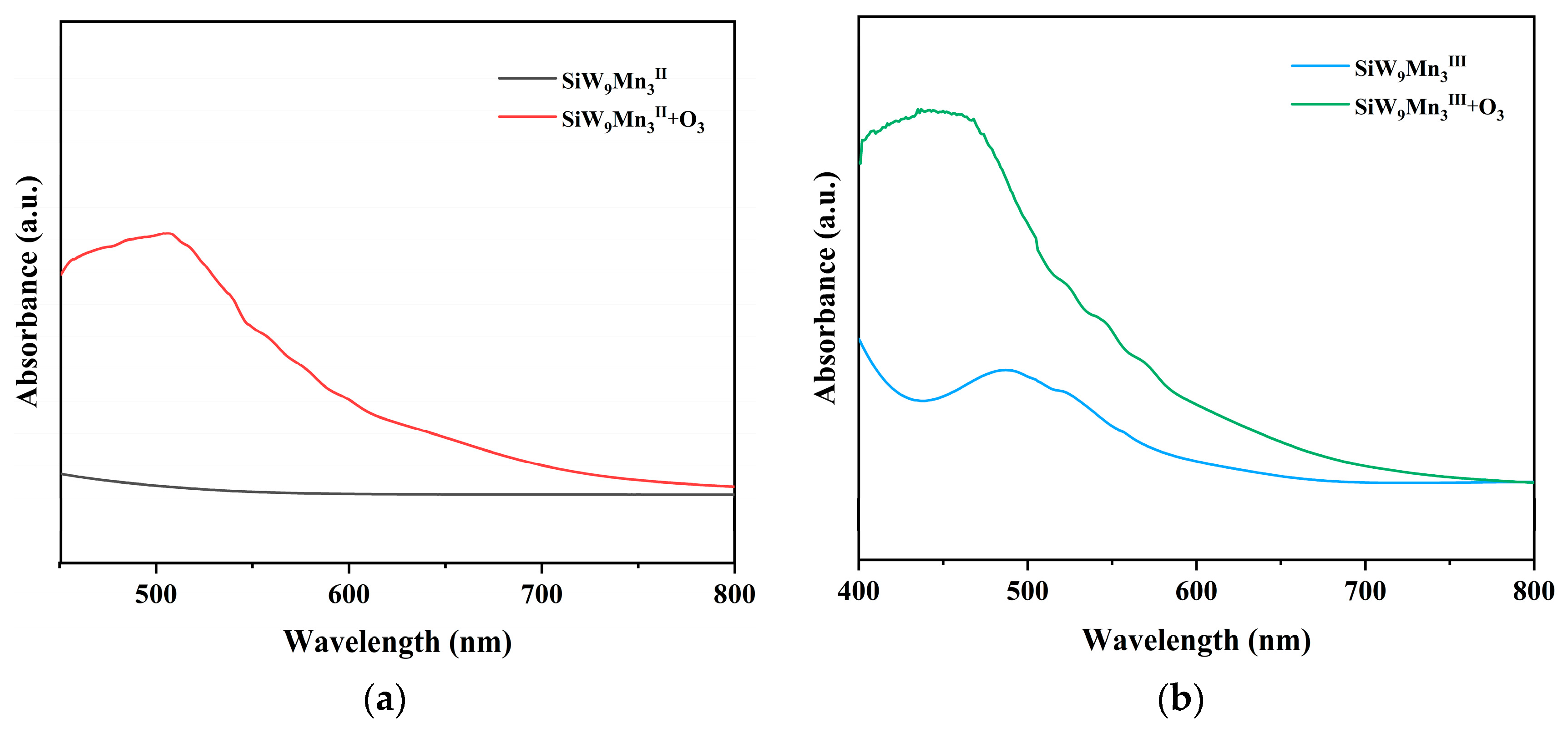

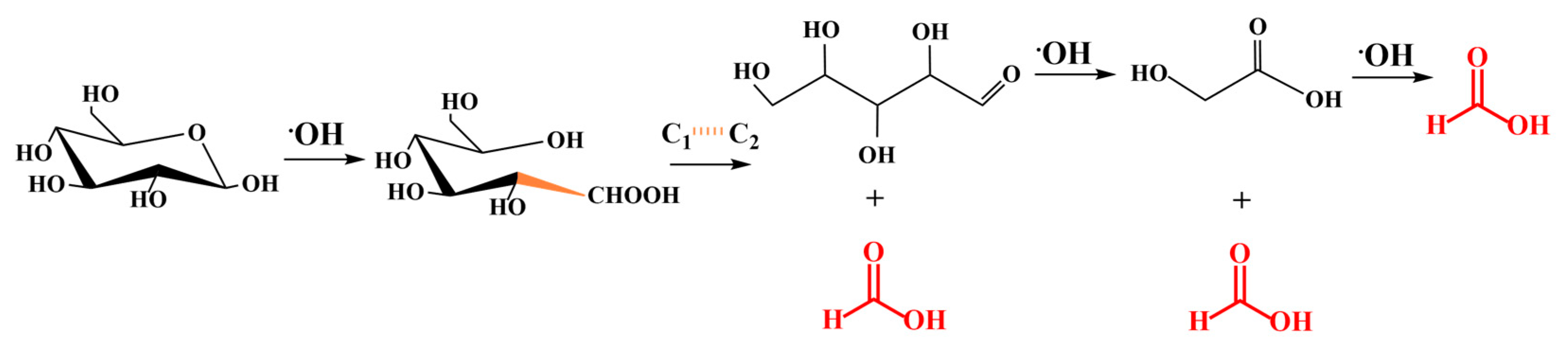

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemicals and Measurements

3.2. Oxidation of Glucose

3.2.1. Oxidation of Glucose with O3

3.2.2. Quenching Experiments

3.2.3. Oxidation of Cellulose with O3

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khalid, H.; Umar, A.; Saeed, M.H.; Nazir, M.S.; Akhtar, T.; Ikhlaq, A.; Ali, Z.; Hassan, S.U. Advances in fuel oil desulfurization: A comprehensive review of polyoxometalate catalysts. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 141, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X. Hydrolysis of cellulose by polyoxometalate pickering interfacial catalysts bearing a flexible surface and hard core. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Bu, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Jadoon, M.; Wang, X. Facile preparation of polyoxometalate nanoparticles via a solid-state chemical reaction for aerobic oxidative desulfurization catalysis. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 12179–12187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, C. Polyoxometalate/Cellulose Nanofibrils Aerogels for Highly Efficient Oxidative Desulfurization. Molecules 2022, 27, 2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, A.; Huber, G.W.; Zhang, T. Catalytic transformation of lignin for the production of chemicals and fuels. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11559–11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppinger, J.; Huang, K.W. Formic acid as a hydrogen energy carrier. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sordakis, K.; Tang, C.; Vogt, L.K.; Junge, H.; Dyson, P.J.; Beller, M.; Laurenczy, G. Homogeneous catalysis for sustainable hydrogen storage in formic acid and alcohols. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 372–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeder, J.D.; Rippon, J.A. Histological differentiation of wool fibres in formic acid. J. Text. Inst. 1982, 73, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wölfel, R.; Taccardi, N.; Bösmann, A.; Wasserscheid, P. Selective catalytic conversion of biobased carbohydrates to formic acid using molecular oxygen. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2759–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, J.; Brunner, B.; Jess, A.; Wasserscheid, P.; Albert, J. Biomass oxidation to formic acid in aqueous media using polyoxometalate catalysts-boosting FA selectivity by in-situ extraction. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 2985–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.K.; Zhang, T.; Das, S. Oxidative transformation of biomass into formic acid. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 2021, 1331–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ding, D.J.; Deng, L.; Guo, Q.X.; Fu, Y. Catalytic air oxidation of biomass-derived carbohydrates to formic acid. ChemSuSChem 2012, 5, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Hou, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Ren, S.; Wu, W. Novel insights into CO2 inhibition with additives in catalytic aerobic oxidation of biomass-derived carbohydrates to formic acid. Renew. Energy 2023, 211, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Hou, Y.; Li, H.; Wei, J.; Ren, S.; Wu, W. Novel chemical looping oxidation of biomass-derived carbohydrates to super-high-yield formic acid using heteropolyacids as oxygen carrier. Renew. Energy 2023, 207, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Deng, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, E.; Wan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Transformation of cellulose and its derived carbohydrates into formic and lactic acids catalyzed by vanadyl cations. ChemSuSChem 2014, 7, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Niu, M.; Hou, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Ren, S.; Marsh, K.N. Catalytic conversion of biomass-derived carbohydrates to formic acid using molecular oxygen. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 2614–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muiuane, V.P.; Ferreira, M.; Bignet, P.; Bettencourt, A.P.; Parpot, P. Production of formic acid from biomass-based compounds using a filter press type electrolyzer. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yu, B.; Hao, L.; Liu, Z. Selective oxidation of glycerol to formic acid catalyzed by Ru(OH)4/r-GO in the presence of FeCl3. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2014, 154–155, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Smith, R.L.; Xu, S.; Li, D.; Yang, J.; Zhang, K.; Shen, F. Manganese oxide as an alternative to vanadium-based catalysts for effective conversion of glucose to formic acid in water. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Yang, J.; Chong, G.H.; Shen, F. Mo-modified MnOx for the efficient oxidation of high-concentration glucose to formic acid in water. Fuel Process. Technol. 2023, 242, 107662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, H.; Nishimura, S.; Ebitani, K. Synthesis of high-value organic acids from sugars promoted by hydrothermally loaded Cu oxide species on magnesia. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2015, 162, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Shi, X.; Zhong, H.; Jin, F. Highly efficient conversion of carbohydrates into formic acid with a heterogeneous MgO catalyst at near-ambient temperatures. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 15423–15436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, H.A.; Kılıç, E.; Erden, L.; Gök, Y. Highly selective oxidation of glucose to formic acid over synthesized hydrotalcite-like catalysts under base free mild conditions. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2022, 48, 4079–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, M.; Liu, X.; Han, Y. Catalytic oxidative conversion of cellulosic biomass to formic acid and acetic acid with exceptionally high yields. Catal. Today 2014, 233, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, J.; Lüders, D.; Bösmann, A.; Guldi, D.M.; Wasserscheid, P. Spectroscopic and electrochemical characterization of heteropoly acids for their optimized application in selective biomass oxidation to formic acid. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yu, B.; Xu, H.; Liu, Z. Heteropolyanion-based ionic liquids catalysed conversion of cellulose into formic acid without any additives. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 4931–4935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Kang, J.; Yan, P.; Shen, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhu, X.; Tan, Q.; Shen, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, S. Surface oxygen vacancies prompted the formation of hydrated hydroxyl groups on ZnOx in enhancing interfacial catalytic ozonation. Appl. Catal. B. Environ. 2024, 341, 123325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Ziółek, M.; Nawrocki, J. Catalytic ozonation and methods of enhancing molecular ozone reactions in water treatment. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2003, 46, 639–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, H. Catalytic ozonation for water and wastewater treatment: Recent advances and perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. Byproduct formation in heterogeneous catalytic ozonation processes. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2023, 2, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téazéa, A.; Hervéa, G.; Finke, R.G.; Lyon, D.K. α-, β-, and γ-Dodecatungstosilicic Acids: Isomers and Related Lacunary Compounds. In Inorganic Syntheses; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990; pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kepert, D.L.; Kyle, J.H. Stepwise base decomposition of 12-tungstosilicate(4−). J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1978, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canny, J.; Teze, A.; Thouvenot, R.; Herve, G. Disubstituted tungstosilicates. 1. Synthesis, stability, and structure of the lacunary precursor polyanion of a tungstosilicate.gamma.-SiW10O368−. Inorg. Chem. 1986, 25, 2114–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ortéga, F.; Sethuraman, P.; Katsoulis, D.E.; Costello, C.E.; Pope, M.T. Trimetallo derivatives of lacunary 9-tungstosilicate heteropolyanions. Part 1. Synthesis and charaterization. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton. Trans. 1992, 1901–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; O’Connor, C.J.; Jameson, G.B.; Pope, M.T. High-Valent Manganese in Polyoxotungstates. 3. Dimanganese Complexes of γ-Keggin Anions. Inorg. Chem. 1996, 35, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamelas, J.A.F.; Gaspar, A.R.; Evtuguin, D.V.; Pascoal Neto, C. Transition metal substituted polyoxotungstates for the oxygen delignification of kraft pulp. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2005, 295, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourné, C.M.; Tourné, G.F.; Malik, S.A.; Weakley, T.J.R. Triheteropolyanions containing copper(II), manganese(II), or manganese(III). J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1970, 32, 3875–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Pei, J.; Yu, X.; Bi, L. Study on Catalytic Water Oxidation Properties of Polynuclear Manganese Containing Polyoxometalates. Catalysts 2022, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xiao, S.; Qian, Y.; Huang, C.H.; Chen, J.; Li, N.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X. Revisiting the synergistic oxidation of peracetic acid and permanganate(Ⅶ) towards micropollutants: The enhanced electron transfer mechanism of reactive manganese species. Water Res. 2024, 262, 122105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barats-Damatov, D.; Shimon, L.J.W.; Weiner, L.; Schreiber, R.E.; Jiménez-Lozano, P.; Poblet, J.M.; de Graaf, C.; Neumann, R. Dicobalt-μ-oxo polyoxometalate compound, [(α2-P2W17O61Co)2O]14−: A potent species for water oxidation, C-H bond activation, and oxygen transfer. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 1779–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snir, O.; Wang, Y.; Tuckerman, M.E.; Geletii, Y.V.; Weinstock, I.A. Concerted proton-electron transfer to dioxygen in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11678–11691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, D.T.; Gibian, M.J. The chemistry of superoxide ion. Tetrahedron 1979, 35, 1471–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jadoon, M.; Yi, X.; Duan, X.; Wang, X. Developing Dawson-type polyoxometalates used as highly efficient catalysts for lignocellulose transformation. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 9213–9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yi, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Palkovits, R.; Beine, A.K.; Liu, C.; Wang, X. Selective production of glycolic acid from cellulose promoted by acidic/redox polyoxometalates via oxidative hydrolysis. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 4575–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamelas, J.A.; Santos, I.C.M.S.; Freire, C.; de Castro, B.; Cavaleiro, A.M.V. EPR and electronic spectroscopic studies of Keggin type undecatungstophosphocuprate(II) and undecatungstoborocuprate(II). Polyhedron 1999, 18, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, M.A.; Khandan, S.; Sabahi, N. Oxidative Desulfurization of Gas Oil Catalyzed by (TBA)4PW11Fe@PbO as an Efficient and Recoverable Heterogeneous Phase-Transfer Nanocatalyst. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 5472–5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, Q.; Li, X. Removal of gaseous hydrogen sulfide by a FeOCl/H2O2 wet oxidation system. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 8163–8173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbage, B.; Li, Y.; Si, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Salah, A.; Zhang, K. Fabrication of folate functionalized polyoxometalate nanoparticle to simultaneously detect H2O2 and sarcosine in colorimetry. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 304, 127429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yu, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Liu, T.; Xiu, M.; Xue, B.; He, L. Ozone-Oxidation of Glucose to Formic Acid over Polyoxmetalates. Molecules 2026, 31, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030467

Yu X, Wang Q, Li H, Liu T, Xiu M, Xue B, He L. Ozone-Oxidation of Glucose to Formic Acid over Polyoxmetalates. Molecules. 2026; 31(3):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030467

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Xia, Qiwen Wang, Haiyan Li, Tong Liu, Mengxue Xiu, Baiji Xue, and Linghe He. 2026. "Ozone-Oxidation of Glucose to Formic Acid over Polyoxmetalates" Molecules 31, no. 3: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030467

APA StyleYu, X., Wang, Q., Li, H., Liu, T., Xiu, M., Xue, B., & He, L. (2026). Ozone-Oxidation of Glucose to Formic Acid over Polyoxmetalates. Molecules, 31(3), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030467