Neuroinflammation as a Central Mechanism in Alzheimer’s Disease: Therapeutic Insights from Schiff Base Derivatives

Abstract

1. Introduction

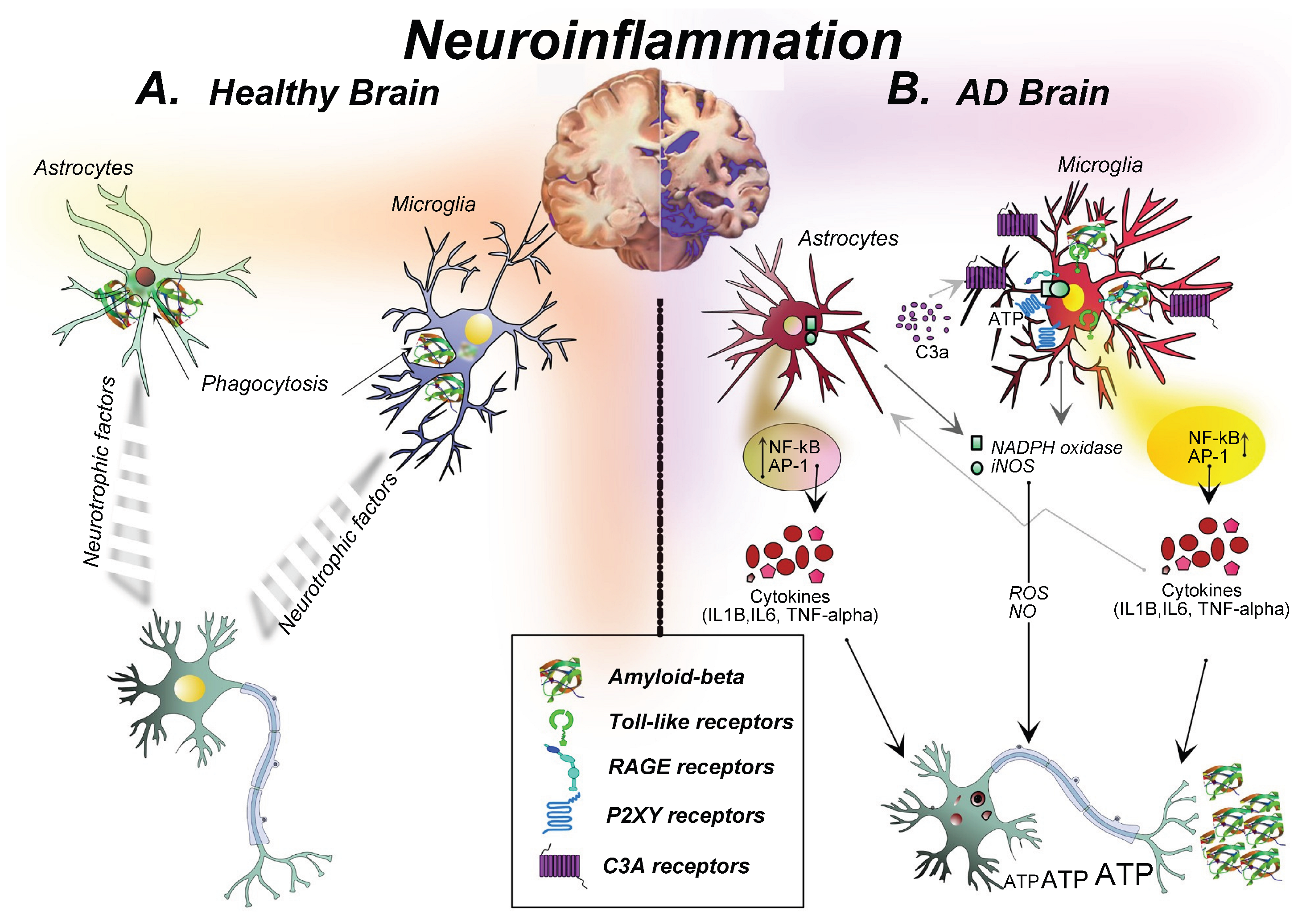

2. Neuroinflammation as a Central Pathological Mechanism in AD

3. Schiff Bases: Chemistry and Biological Properties

3.1. Structural Features and Synthesis

3.2. General Pharmacological Properties

3.3. Schiff Base–Metal Complexes

4. Therapeutic Potential of Schiff Bases Against Neuroinflammation in AD

4.1. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4.2. Antioxidant Activity and ROS Scavenging

4.3. Metal Chelation and Inhibition of Aβ Aggregation

4.4. Anti-Cholinesterase Activity

4.5. Neuroprotective Activity

4.6. Anti-Amnesic Activity

5. Clinical Translation of Schiff Base Derivatives in AD: Lessons from Huperzine a Prodrug ZT-1

6. Future Perspectives

6.1. Targeting Multiple Pathways

6.2. Nanocarrier-Based Drug Delivery Systems

6.3. Artificial Intelligence and SAR-Guided Design

6.4. Personalized and Precision Medicine Approaches

6.5. Advancing Translational and Clinical Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AChE | acetylcholinesterase |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ADAS-cog | assessment cognitive subscale |

| ADMET | absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

| APP | amyloid precursor protein |

| Aβ | amyloid-beta |

| BBB | blood-brain barrier |

| BChE | butyrylcholinesterase |

| BRAINz | Better Recollection for Alzheimer’s patients with ImplaNts of ZT-1 |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CSF-1R | Colony-stimulating factor receptor Type 1 |

| DAM | disease-associated microglia |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FLT3 | Fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 |

| HAT | hydrogen atom transfer |

| HER1/EGFR/ERBB1 | epidermal growth factor receptor |

| HER2/ERBB2 | human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 |

| IL-10 | interleukin-10 |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| JAK/STAT | Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| KIT | stem cell factor receptor |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MTDLs | multi-target-directed ligands |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRs | NOD-like receptors |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NOD | nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain |

| NORT | new object recognition test |

| NPI-Q | Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire |

| PDGFR | platelet-derived growth factor receptors |

| PI3K/Akt | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt |

| PRR | pattern recognition receptors |

| RAGE | receptors for advanced glycoxidation end-products |

| RET | glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor receptor |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SARs | structure–activity relationships |

| SET | single electron transfer |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| TREM2 | triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 |

| VEGFR | vascular endothelial growth factor receptor |

References

- Gauthier, S.; Webster, C.; Servaes, S.; Morais, J.A.; Rosa-Neto, P. World Alzheimer Report 2022: Life After Diagnosis—Navigating Treatment, Care and Support; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, J.; Lee, G.; Ritter, A.; Sabbagh, M.; Zhong, K. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2019. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019, 5, 272–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ransohoff, R.M. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science 2016, 353, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, F.; Edison, P. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: Where do we go from here? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Jaryal, A.; Bhalla, A. Recent advances in biological and medicinal profile of Schiff bases and their metal complexes: An updated version (2018–2023). Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.-Y.; Zhao, Q.-H.; Liu, Y.; Gui, Y.-Z.; Liu, G.-Y.; Zhu, D.-Y.; Yu, C.; Hong, Z. Phase I study on pharmacokinetics and tolerance of ZT-1, a prodrug of huperzine A, for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leman, L.; Kitson, S.L.; Brown, R.T.; Cairns, J.; Watters, W.; McMordie, A.; Murrell, V.L.; Marfurt, J. Synthesis of isotopically labelled [14C]ZT-1 (Debio-9902), [d3]ZT-1 and (−)-[d3]huperzine A. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2011, 54, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbo, S.; Stevens, B. Microglia: The brain’s first responders. Cerebrum 2017, 2017, cer-14-17. [Google Scholar]

- Heneka, M.T.; Kummer, M.P.; Latz, E. Innate immune activation in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.V.; Hanson, J.E.; Sheng, M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. Astrocytic and microglial cells as modulators of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflamm. 2022, 19, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, L.E.; Fernandez, J.A.; Maccioni, A.A.; Jimenez, J.M.; Maccioni, R.B. Neuroinflammation in pathogenesis and molecular diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Med. Res. 2008, 39, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Barres, B.A. Reactive astrocytes: Production, function, and therapeutic potential. Immunity 2017, 46, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, G.; Khannazer, N.; Mirshafiey, A. Potential role of chemokines in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2014, 29, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twarowski, B.; Herbet, M. Inflammatory processes in Alzheimer’s disease—Pathomechanism, diagnosis and treatment: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, C.M.; Da Silva, D.L.; Modolo, L.V.; Alves, R.B.; De Resende, M.A.; Martins, C.V.B.; De Fátima, Á. Schiff bases: A short review of their antimicrobial activities. J. Adv. Res. 2011, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, A.; Mahmud, T.; Khalid, M.; Khan, H.; Sadia, A.; Samra, M.M.; Basra, M.A.R. Biological evaluation of synthesized Schiff base–metal complexes derived from sulfisomidine. J. Pharm. Innov. 2022, 17, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, Z.H.; Arif, M.; Akhtar, M.A.; Supuran, C.T. Metal-based antibacterial and antifungal agents: Co(II), Cu(II), Ni(II) and Zn(II) complexes with amino acid–derived compounds. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2006, 2006, 83131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnham, K.J.; Masters, C.L.; Bush, A.I. Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Iqbal, T.; Khan, M.B.; Hussain, R.; Khan, Y.; Darwish, H.W. Novel pyrrole-based triazole moiety as therapeutic hybrid: Anti-Alzheimer potential with molecular mechanism. BMC Chem. 2024, 18, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwade, K.N.; Sakhare, K.B.; Sakhare, M.A.; Thakur, S.V. Neuroprotective, anticancer and antimicrobial activities of azo-Schiff base ligand and its metal complexes. Eurasian J. Chem. 2025, 30, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulguemh, I.-E.; Beghidja, A.; Khattabi, L.; Long, J.; Beghidja, C. Copper(II) complexes based on a thiophene carbohydrazide Schiff base ligand. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2020, 507, 119519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savcı, A.; Turan, N.; Buldurun, K.; Eşref Alkış, M.; Alan, Y. Schiff base containing fluorouracil and its M(II) complexes: Cytotoxic and antioxidant activities. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022, 143, 109780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irisli, S.; Cakir, A.; Gunnaz, S. Schiff base complexes targeting amyloid-β aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 154, 107999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasar, U.; Demir, Y.; Gonul, I.; Ozaslan, M.S.; Celik, G.G.; Turkes, C.; Beydemir, S. Schiff base sulfonate derivatives as carbonic anhydrase and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202402893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almehizia, A.A.; Naglah, A.M.; Aljafen, S.S.; Hassan, A.S.; Aboulthana, W.M. Biological activities of Schiff base–synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnaz, S.; Yildiz, E.; Tuncel Oral, A.; Yurt, F.; Erdem, A.; Irisli, S. Schiff base–platinum and ruthenium complexes with anti-Alzheimer properties. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2025, 264, 112790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irisli, S.; Günnaz, S.; Özcan, O.; Ari, A.; Maral, M.; Erdem, A.; Özel, D.; Yurt, F. Platinum(II) Schiff base complexes inhibiting amyloid β1–42 aggregation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2024, 38, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, Q.; Karim, N.; Shoaib, M.; Zahoor, M.; Rahman, M.U.; Bilal, H.; Ullah, R.; Alotaibi, A. Vanillin derivatives as antiamnesic agents. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozil, M.; Balaydin, H.T.; Dogan, B.; Senturk, M.; Durdagi, S. Aryl Schiff base derivatives as inhibitors of hCA I, hCA II, AChE, and BuChE. Arch. Pharm. 2024, 357, e2300266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakor, P.M.; Patel, J.D.; Patel, R.J.; Chaki, S.H.; Khimani, A.J.; Vaidya, Y.H.; Chauhan, A.P.; Dholakia, A.B.; Patel, V.C.; Patel, A.J.; et al. New Schiff bases: Synthesis, characterization, biomedical applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 35431–35448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naglah, A.; Almehizia, A.; Al-Wasidi, A.; Alharbi, A.; Alqarni, M.; Hassan, A.; Aboulthana, W. Pyrazole-based Schiff bases as multi-target anti-Alzheimer agents. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, H.M.; Almehizia, A.A.; Al-Omar, M.A.; Obaidullah, A.J.; Zen, A.A.; Hassan, A.S.; Aboulthana, W.M. Schiff bases bearing pyrazole scaffold as antioxidant, anti-diabetic, anti-Alzheimer agents. Molecules 2023, 28, 7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.; Rahim, F.; Zaman, K.; Anouar, E.; Uddin, N.; Nawaz, F.; Sajid, M.; Khan, K.; Shah, A.; Wadood, A.; et al. Benzo-d-oxazole bis Schiff bases as anti-Alzheimer agents. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 41, 1649–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.; Khan, S.; Ullah, H.; Ali, F.; Khan, Y.; Sardar, A.; Iqbal, R.; Ataya, F.S.; El-Sabbagh, N.M.; Batiha, G.E. Benzimidazole-based Schiff base hybrids for multi-target Alzheimer drug development. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senocak, A.; Tas, N.A.; Taslimi, P.; Tuzun, B.; Aydin, A.; Karadag, A. Amino acid Schiff base Zn(II) complexes as therapeutic approaches in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e22969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, F.; Rehman, N.; Khan, A.; Iqbal, S.; Paracha, R.; Uddin, J.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Lodhi, M. Hydrazone Schiff bases for Alzheimer’s therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 946134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevskaya, A.; Anikina, L.; Purgatorio, R.; Catto, M.; Nicolotti, O.; de Candia, M.; Pisani, L.; Borisova, T.; Miftyakhova, A.; Varlamov, A.; et al. Homobivalent lamellarin-like Schiff bases. Molecules 2021, 26, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-Y.; Huang, J.-S.; Gu, X.-L.; Tan, W.-W.; Cui, H.; Yang, B.-C.; Yang, T. Fluorine-containing Schiff-base derivatives of huperzine A. J. Mol. Struct. 2026, 1349, 143906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, S.H. Gastroprotective effects of Schiff base CdCl2 compound. Cureus 2024, 16, e75963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedifard, M.; Faraj, F.; Paydar, J.; Looi, C.Y.; Hajrezaei, M.; Hasanpourghadi, M.; Kamalidehghan, B.; Abdul Majid, N.; Ali, H.; Abdulla, M. Quinazolinone Schiff bases inducing apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, M.S.; Rayhan, N.M.A.; Emon, M.S.H.; Islam, M.T.; Rathry, K.; Hasan, M.M.; Islam Mansur, M.M.; Srijon, B.C.; Islam, M.S.; Ray, A.; et al. Antioxidant activity of Schiff base ligands: Review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 33094–33123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anouar, H.; Raweh, S.; Bayach, I.; Taha, M.; Baharudin, M.S.; Di Meo, F.; Hasan, M.H.; Adam, A.; Ismail, N.H.; Weber, J.F.; et al. Antioxidant properties of phenolic Schiff bases. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2013, 27, 951–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.Z.; Liu, Z.Q. Free-radical-scavenging mechanism of hydroxyl-substituent Schiff bases. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2007, 25, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.A.; Ismail, M.M.; Morsy, J.M.; Hassanin, H.M.; Abdelrazek, M.M. Chitosan Schiff bases with anticancer and antioxidant activities. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 4035–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sidhu, J.; Lui, F.; Tsao, J.W. Alzheimer Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Du, F.; Yu, C.; Xu, X.; Zheng, J.; Xu, F.; Zhu, D. Determination of ZT-1 and huperzine A in rat blood. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 18, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debiopharm Group. Clinical Update—Debio 9902 (ZT-1) for Alzheimer’s Disease. Press Release, 11 June 2007. Available online: https://www.debiopharm.com/drug-development/press-releases/clinical-update-debio-9902-zt-1-for-alzheimers-disease/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Opdam, F.L.; Guchelaar, H.J.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schellens, J.H. Lapatinib for breast cancer. Oncologist 2012, 17, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, T.A.; Gore, M.E. Sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2016, 8, 348–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, F.; Fricker, G. Liposomal conjugates for CNS drug delivery. Pharmaceutics 2015, 7, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, D.; Nikolova, D.; Vassileva, E.; Kostova, B. Chitosan nanoparticles for nasal galantamine delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Zhang, X.; Ge, K.; Yin, Y.; Machuki, J.O.; Yang, Y.; Shi, H.; Geng, D.; Gao, F. Carbon nitride-based nanocaptor for Alzheimer’s phototherapy. Biomaterials 2021, 267, 120483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.D.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.Y.; Zhao, P. Serum copper, zinc, and iron in Alzheimer’s disease: Meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound Type | Reported Mechanism(s) | Level of Evidence | Key Findings/Outcomes | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrimidine-based Schiff base complexes | Inhibition of amyloid-beta (Aβ) aggregation | Cell-based model | Reduced amyloid fibril formation in vitro | [25] |

| Sulfonate Schiff base | Carbonic anhydrases inhibition; acetylcholinesterase/butyrylcholinesterase (AChE/BuChE) inhibition | In vitro enzyme assays; molecular docking | Dual enzymatic inhibition with nanomolar I half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values | [26] |

| Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II), Cu(II), Zn(II), VO(II) azo–Schiff base | Neuroprotective activity | Cell-based model | Improved neuronal viability | [22] |

| Schiff base-synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles | Antioxidant; free radical scavenging; AChE inhibition; anti-inflammatory | In vitro enzyme assays | Schiff base-synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles demonstrated superior in vitro biological activities when compared to the ligand | [27] |

| Pt and Ru Schiff base complexes | Inhibition of Aβ aggregation; neuroprotective | Cell-based model | Reduced β-sheet formation and protected neuronal cells | [28,29] |

| Vanillin-based Schiff bases | Antioxidant; AChE inhibition; antiamnesic in rodents | In vitro enzyme assays; in vivo animal behavioral studies | Improved memory performance in the scopolamine-induced amnesia model | [30] |

| Pyrrole-derived triazole Schiff base | AChE/BuChE inhibition | In vitro enzyme assays; molecular docking | Potent cholinesterase inhibition compared to the standard drug, Donepezil, and Allanzanthone | [21] |

| Aryl Schiff base | Carbonic anhydrases inhibition; AChE/BuChE inhibition | In vitro enzyme assays; molecular docking | Multi-target inhibition with selectivity toward hCA II | [31] |

| Schiff bases | Aβ inhibition in transgenic CL4176 Caenorhabditis elegans | In vivo animal studies | Delayed paralysis onset induced by Aβ expression in a transgenic nematode model | [32] |

| Pyrazole-based Schiff bases | Antioxidant; free radical scavenging; AChE inhibition; anti-inflammatory | In vitro enzyme assays | Suppressed neuroinflammation and oxidative markers in vitro | [33,34] |

| Benzo[d]oxazole bis–Schiff base | AChE/BuChE inhibition | In vitro enzyme assays; molecular docking | Strong dual cholinesterase inhibition with favorable selectivity toward BuChE | [35] |

| Benzimidazole-based Schiff base | AChE/BuChE inhibition | In vitro enzyme assays; molecular docking | Three compounds outperform the standard drug, Donepezil | [36] |

| Amino acid Schiff base Zn(II) complexes | AChE/BuChE inhibition | In vitro enzyme assays; molecular docking | High selectivity for BuChE over AChE | [37] |

| 2-Mercaptobenzimidazole hydrazone Schiff base derivatives | AChE/BuChE inhibition; Ca2+ antagonistic activity | In vitro enzyme assays; molecular docking | Suppressed AChE and modulated intracellular calcium signaling | [38] |

| Lamellarin-like Schiff bases | Inhibition of Aβ aggregation; AChE/BuChE inhibition; MAO inhibition | In vitro enzyme assays | Multi-target profile including both anti-Alzheimer and antidepressant | [39] |

| Fluorine-containing Schiff-base derivatives of huperzine A | Aβ inhibition in transgenic CL4176 Caenorhabditis elegans | In vivo animal studies; molecular docking | Higher % of non-paralyzed transgenic nematode model; Higher superoxide dismutase (SOD) production and expression of Skn-1 and daf-16 | [40] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abdullah, S.K.; See-Too, W.S.; Mohd Mohidin, T.B.; Mohan, G. Neuroinflammation as a Central Mechanism in Alzheimer’s Disease: Therapeutic Insights from Schiff Base Derivatives. Molecules 2026, 31, 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030465

Abdullah SK, See-Too WS, Mohd Mohidin TB, Mohan G. Neuroinflammation as a Central Mechanism in Alzheimer’s Disease: Therapeutic Insights from Schiff Base Derivatives. Molecules. 2026; 31(3):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030465

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Siti Khadijah, Wah Seng See-Too, Taznim Begam Mohd Mohidin, and Gokula Mohan. 2026. "Neuroinflammation as a Central Mechanism in Alzheimer’s Disease: Therapeutic Insights from Schiff Base Derivatives" Molecules 31, no. 3: 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030465

APA StyleAbdullah, S. K., See-Too, W. S., Mohd Mohidin, T. B., & Mohan, G. (2026). Neuroinflammation as a Central Mechanism in Alzheimer’s Disease: Therapeutic Insights from Schiff Base Derivatives. Molecules, 31(3), 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030465